Emotions of Candidates on Twitter in the 2023 Seville City Council Election: A Second-Order Campaign?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations and Background

3. Research Design

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

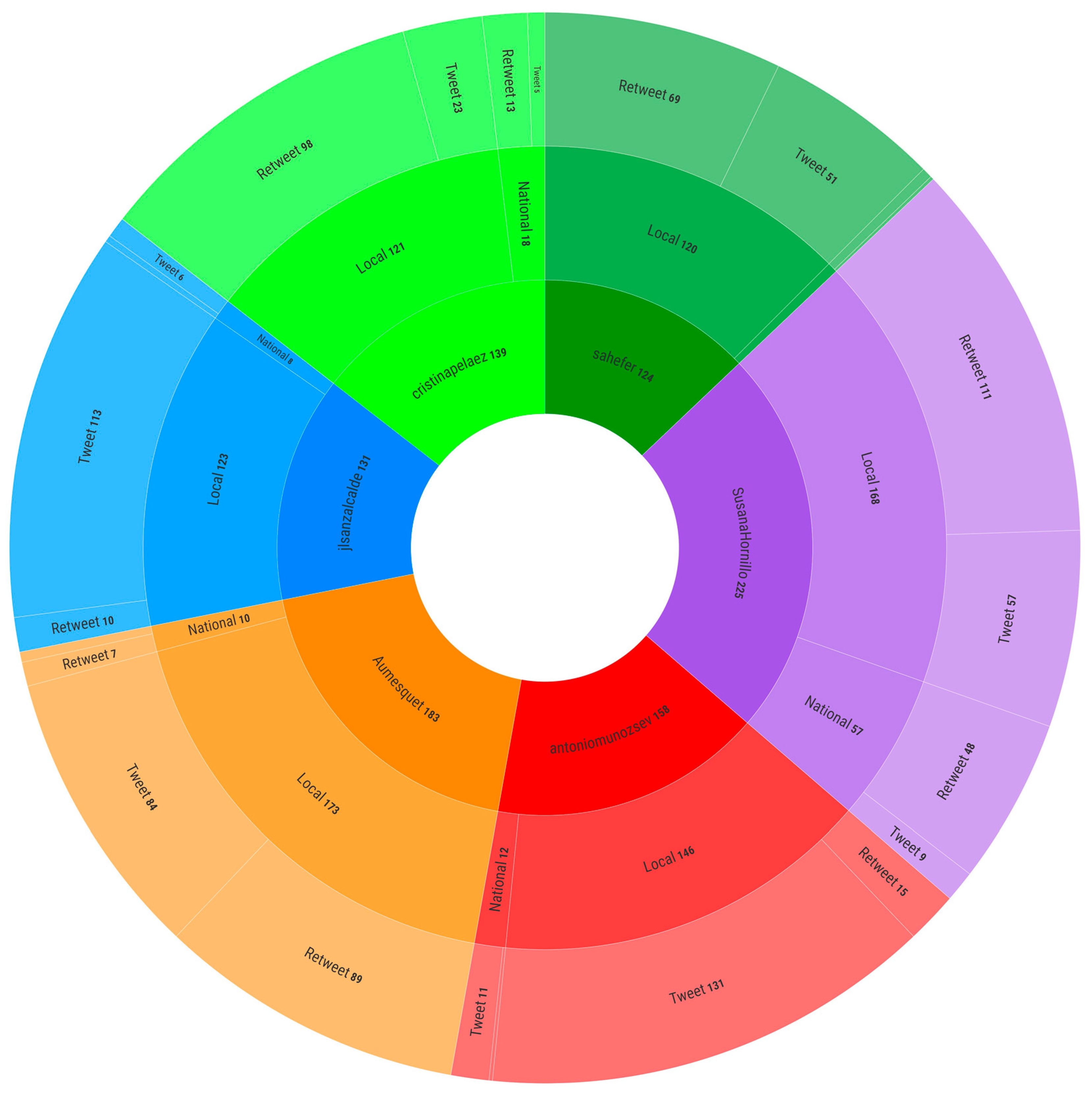

| 1 | Towards the end of July 2023, Twitter was rebranded as “X” and a capital letter ‘x’ substituted the iconic blue bird logo that had represented it since its origins. |

| 2 | Overall, the information contained in this social network, combined with analytic strategies associated with big data, is allowing new and interesting research questions to be proposed and explored in several academic fields (Kumar and Jaiswal 2020; Thakur 2022; Taecharungroj 2023; Zimmer and Proferes 2014). |

| 3 | In addition to the above-noted, several researches have analysed other social networks alongside Twitter (for instance, Dumitrica 2016; Lappas et al. 2016; Skogerbø and Krumsvik 2015; Trejos-Gil 2021). |

| 4 | PSOE is a social democratic party whose deputies at the European Parliament belong to the S&D group. With respect to UP, located on the left of the latter, it consists of a coalition with deputies at the European Parliament that are included in the groups GUE/NGL and Greens/EFA. |

| 5 | PP mirrors the conservative and christian-democratic ideology that defines the group EPP, to which its representatives are affiliated at the European Parliament. Turning now to Vox, its far-right representatives owe allegiance to the group ECR on the European level. To conclude, in so far as it is defined as a liberal formation, Cs is integrated within Renew in the European framework. |

| 6 | In the whole, the entirety of Andalusia has entered the general regime that models party competition (Ocaña and Oñate 2000), despite the particularities displayed in its own competency structure (Ortega and Montabes-Pereira 2011). |

| 7 | The Spanish municipal electoral system is defined by its representative character and based upon the one designed for the lower chamber, with some slight changes. Under these circumstances, there is one unique constituency for the entire local territory, whose number of seats for each individual municipality is subjected to the size of their population—in the case of Seville, 31 representatives are elected. Candidacies are submitted as closed and blocked lists, and seats are then distributed to those formations with a valid vote rate higher than 5 per cent, as the D’Hondt formula dictates. Once the council collegiate body is formed, the mayor is elected by absolute majority; otherwise, the councillor at the top of the most-voted list is proclaimed mayor (Delgado-Sotillos 2010; Montabes-Pereira et al. 2023). As was the case of Juan Espadas in 2019 after he led the top of PSOE’s list, in so far as there was no alternative absolute majority. However, he resigned in January 2021 and was replaced by Antonio Muñoz, who was number three on the list and would later become the candidate of the same party for the May 2023 elections. |

| 8 | Elections to the Parliament of Andalusia were held in 2022, when PP achieved an absolute majority for the first time in the history of said autonomous community. The institutional access to autonomy of every autonomous community shapes their electoral calendar (Montabes-Pereira et al. 2023). |

| 9 | Nevertheless, available evidence supports that interdependence may manifest permanently between arenas due to Spain’s multi-layered political system (Ortega and Recuero-López 2020). |

| 10 | Estimations resulted from the 40dB poll for the PRISA group—issued 6 days prior to the elections—projected the aforementioned technical draw, portrayed the then mayor as the most recognisable candidate, claimed PSOE was the party with the greatest affinity rate from respondents, and assessed governmental management as positive or very positive by a 34 per cent against the negative or very negative 24 per cent (https://elpais.com/espana/elecciones-municipales/2023-05-22/el-psoe-aventajaria-por-la-minima-al-pp-en-sevilla.html, accessed on 25 July 2023). |

| 11 | Preceded by Granada (Andalusia), the most active city. |

| 12 | This type of accounts was fully valid from January 2021 to June 2023. https://blog.twitter.com/es_la/topics/product/2021/haciendo-posible-futura-investigacion-academica-twitter-api (accessed on 14 october 2023). |

| 13 | However, this is the result of different strategies. When it comes to Cristina Peláez, 80 per cent of this type of publication reflects the general diffusion of her party’s accounts on different levels, such as municipal. As for Susana Hornillos, 71 per cent consists of retweets of national leaders from her origin party (“Podemos”) as well as retweets of the national account, amongst others. Needless to say, she also retweets several of her anonymous partisans to a lower degree. |

| 14 | Tweets referring to real estate speculation or criticising centralism and capitalism. |

References

- Arce-García, Sergio, Fátima Vila Márquez, and Joan-Francesc Fondevila-Gascón. 2022. Analysis of the Twitter discourse in the 2019 electoral debates in Spain: A comparative algorithmic study. Communication & Society 35: 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrie, Christopher, and Justin Chun-ting Ho. 2021. academictwitteR: An R package to access the Twitter Academic Research Product Track v2 API endpoint. Journal of Open Source Software 6: 3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borja-Orozco, Henry. 2022. Political consumerism: Communication strategies based on ideological and performance voting. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología 54: 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, Ryan L., Ashwini Ashokkumar, Sarah Seraj, and James W. Pennebaker. 2022. The Development and Psychometric Properties of LIWC-22. Austin: University of Texas. [Google Scholar]

- Capó-Giol, Jordi. 1996. Elecciones municipales, pero no locales. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 56: 143–64. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Rodríguez, Jesús, and Claudia Eugenia Toca-Torres. 2022. La opinión pública en Twitter Análisis durante la contienda electoral en la capital colombiana. Opinião Pública 28: 787–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, Michael A., Matthias R. Mehl, and James W. Pennebaker. 2004. Linguistic Markers of Psychological Change Surrounding September 11 2001. Psychological Science 15: 687–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corduneanu, Victoria Isabela. 2018. El papel de las emociones sociales y personales en la participación política. Revista Mexicana de Opinión Pública 26: 71–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criado, J. Ignacio, Guadalupe Martínez-Fuentes, and Aitor Silván. 2013. Twitter en campaña: Las elecciones municipales españolas de 2011. Revista de Investigaciones Políticas y Sociológicas 12: 93–113. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Richard, Christina Holtz Bacha, and Marion R. Just, eds. 2017. Twitter and Elections around the World: Campaigning in 140 Characters. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Sotillos, Irene. 2010. Elecciones municipales en España. dimensiones analíticas y aspectos distintivos de ocho procesos electorales (1979–2007). Política y Sociedad 47: 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Sotillos, Irene. 2023. Reconsiderando la teoría de las elecciones de segundo orden. ¿Cómo clasificar a las elecciones municipales españolas de 2019? Revista Española de Ciencia Política 62: 13–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Sotillos, Irene, and Javier Redondo-Rodelas. 2020. El sistema electoral municipal: Análisis de los efectos de dos sistemas diferentes. In Sistemas Electorales en España: Caracterización, Efectos, Rendimientos y Propuestas de Reforma. Edited by Carmen Ortega, Juan Montabes-Pereira and Pablo Oñate. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas, pp. 329–46. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrica, Delia. 2016. Imagining engagement: Youth, social media, and electoral processes. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 22: 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncombe, Constance. 2019. The Politics of Twitter: Emotions and the Power of Social Media. International Political Sociology 13: 409–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Cabana, Mercedes, José Rúas-Araújo, and María Teresa Alves-Pérez. 2014. Psicología, lenguaje y comunicación: Análisis con la herramienta LIWC de los discursos y tweets de los candidatos a las elecciones gallegas de 2012. Anuario de Psicología 44: 169–84. [Google Scholar]

- Frame, Alex, Arnaud Mercier, Gilles Brachotte, and Caja Thimm, eds. 2016. Tweets from the Campaign Trail Researching Candidates’ Use of Twitter During the European Parliamentary Elections. Lausanne: Peter Lang Academic Research. [Google Scholar]

- García-Carretero, Lucía, and Laura Pérez-Altable. 2017. Barcelona en Comú on Twitter. Analyzing the electoral communication of the confluence during the 2015 council election. El profesional de la información 26: 871–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Hípola, Giselle, and Sergio Pérez-Castaños. 2021. Las emociones como estrategia de comunicación en las elecciones europeas de 2019: VOX. Más Poder Local 43: 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gendźwiłł, Adam, and Kristof Steyvers. 2021. Guest editors’ introduction: Comparing local elections and voting in Europe: Lower rank, different kind… or missing link? Local Government Studies 47: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Calderón, Bernardo, Sergio Roses, and Francisco-Javier Paniagua-Rojano. 2017. La campaña en 140 caracteres. Empleo de Twitter por parte de los candidatos de los partidos mayoritarios ante las elecciones generales de 2016 en España. El profesional de la información 26: 816–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hagar, Douglas. 2015. #Vote4me: The impact of twitter on municipal campaign success. Paper presented at the 2015 International Conference on Social Media & Society, London, UK, July 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Heath, Anthony, Iain McLean, Bridget Taylor, and John Curtice. 1999. Between first and second order: A comparison of voting behaviour in european and local elections in Britain. European Journal of Political Research 35: 389–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himelboim, Itai, Kaye D. Sweetser, Spencer F. Tinkham, Kristen Cameron, Matthew Danelo, and Kate West. 2016. Valence-based homophily on Twitter: Network Analysis of Emotions and Political Talk in the 2012 Presidential Election. New Media & Society 18: 1382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İkiz, Ozlem Ozdesim, Mehmet Zahid Sobaci, Nilay Yavuz, and Naci Karkin. 2014. Political use of twitter: The case of metropolitan mayor candidates in 2014 local elections in Turkey. Paper presented at the 8th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance, Guimaraes, Portugal, October 27–30; pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara, René, Antoine Faure, Jarnishs Beltrán, and Gonzalo Castro. 2017. La notoriedad política en los candidatos que usan Twitter. Un ejercicio de clusterización durante las elecciones municipales en Chile (2016). Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 72: 803–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaráiz-Gulías, Erika, María Pereira-López, and José Manuel Rivera-Otero. 2020a. Análisis de emociones originadas por las publicaciones en Twitter de los candidatos a las elecciones generales de Bolivia y España en 2019. Journal of Iberian and Latin American Research 26: 371–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaráiz-Gulías, Erika, Paloma Castro Martínez, and Gabriel Colomé García. 2022. The Emotional Dimension of the Spanish Far Right and Its Effects on Satisfaction with Democracy. Social Sciences 11: 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaráiz-Gulías, Erika, Paulo Carlos López-López, and Miguel Anxo Bastos Boubeta. 2020b. Economía, política social y Twitter: Análisis de las emociones negativas en cuatro elecciones presidenciales latinoamericanas a través del LIWC. RISTI-Revista Ibérica de Sistemas e Tecnologias de In-formação E26: 270–82. [Google Scholar]

- Jungherr, Andreas. 2016. Twitter use in election campaigns: A systematic literature review. Journal of Information Technology & Politics 13: 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropf, Martha. 2021. Using Campaign Communications to analyze civility in ranked choice voting elections. Politics and Governance 9: 280–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruikemeier, Sanne. 2014. How political candidates use Twitter and the impact on votes. Computers in Human Behavior 34: 131–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Akshi, and Arunima Jaiswal. 2020. Systematic literature review of sentiment analysis on Twitter using soft computing techniques. Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience 32: e5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kušen, Ema, and Mark Strembeck. 2018. Politics, sentiments, and misinformation: An analysis of the Twitter discussion on the 2016 Austrian Presidential Elections. Online Social Networks and Media 5: 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampoltshammer, Thomas J., Gabriele De Luca, and Lőrinc Thurnay. 2023. Digital News and Political Tweets in the Lower Austrian Municipal Elections: A Case Study on Digital Journalism and Political Communication. Social Sciences 12: 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappas, Georgios, Amalia Triantafillidou, Prodromos Yannas, Anastasia Kavada, Alexandros Kleftodimos, and Olga Vasileiadou. 2016. Social Media Battles: Their Impact during the 2014 Greek Municipal Elections. Journal of Universal Computer Science 22: 375–93. [Google Scholar]

- Lombana-Bermúdez, Andrés, Maryluz Vallejo Mejía, Liliana María Gómez Céspedes, and Juan Federico Pino Uribe. 2022. Cámaras de eco, desinformación y campañas de desprestigio en Colombia. Un estudio de Twitter y las elecciones locales de Medellín en 2019. Política y Gobierno 29: ePYG 1494. [Google Scholar]

- López-de-Ayala-López, María Cruz, Beatriz Catalina-García, and José-Gabriel Fernández-Fernández. 2016. Spanish mayors’ public communication on Twitter during local elections. Revista Latina de Comunicacion Social 71: 1280–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-López, Paulo Carlos, Pablo Oñate, and Álvaro Rocha. 2020. Social media mining, debate and feelings: Digital public opinion’s reaction in five presidential elections in Latin America. Cluster Computing 23: 1875–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, George E. 2002. The Sentimental Citizen: Emotion in Democratic Politics. University Park: Penn State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, George E., W. Russell Neuman, and Michael MacKuen. 2000. Affective Intelligence and Political Judgment. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marien, Sofie, Ruth Dassonneville, and Marc Hooghe. 2015. How Second Order Are Local Elections? Voting Motives and Party Preferences in Belgian Municipal Elections. Local Government Studies 41: 898–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, Michael. 1998. Testing the Second-Order Election Model after Four European Elections. Journal of Political Science 28: 591–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rolán, Xabier. 2016. Desigualdad en la participación en Twitter. Las elecciones municipales en España en 2015: El caso gallego. Opción 32: 169–86. [Google Scholar]

- Moe, Hallvard, and Anders Olof Larsson. 2013. Untangling a complex media system: A comparative study of Twitter-linking practices during three Scandinavian election campaigns. Information, Communication & Society 16: 775–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montabes-Pereira, Juan, Francisco Javier Alarcón González, and José Manuel Trujillo. 2023. Las elecciones municipales de 2023 en España: La consolidación de una dinámica de bloques. Más Poder Local 53: 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicasio-Varea, Blanca, and Marta Pérez-Galdón. 2021. Comunicación electoral 2.0: Presencia y actividad en Twitter de los candidatos a la alcaldía de Valencia en las elecciones del 26 de mayo de 2019. Política y Sociedad 58: e65475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, Pippa. 1997. Second-order elections revisited. European Journal of Political Research 31: 109–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, Pippa, John Curtice, David Sanders, Margaret Scammell, and Holli A. Semetko. 1999. On Message: Communicating the Campaign. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novelli, Edoardo, Bengt Johansson, and Dominic Wring, eds. 2022. The 2019 European Electoral Campaign: In the Time of Populism and Social Media. Palgrave Macmillan. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocaña, Francisco A., and Pablo Oñate. 2000. Las elecciones autonómicas de 1999 y las Españas electorales. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 90: 183–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, Carmen, and Fátima Recuero-López. 2020. Liderazgo político y elecciones municipales: ¿nacionalización, regionalización o localismo? Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 169: 123–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, Carmen, and Juan Montabes-Pereira. 2011. Identificación partidista y voto: Las elecciones autonómicas en Andalucía (2004-2008). Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 134: 27–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, Alfonso. 2023. Research Trends in Social Media Role in Political Campaigns: A Bibliometric Analysis. Review of Communication Research 11: 150–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, María, Nieves Lagares, and Paulo Carlos López-López. 2021. Partidos y líderes en las elecciones generales de 2016 y 2019: Una visión emocional. Revista de Estudios Políticos 193: 213–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Castaños, Sergio, Javier Antón Merino, and Sandra García Santamaría. 2023. Emociones, liderazgo y redes sociales. Propuesta para su medición en materiales de campaña electoral. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 184: 125–36. [Google Scholar]

- Quevedo, Raquel, Marta Portalés Oliva, and Salomé Berrocal Gonzalo. 2016. El uso de la imagen en Twitter durante la campaña electoral municipal de 2015 en España. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 71: 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Esparza, Nairán, James W. Pennebaker, Florencia Andrea García, and Raquel Suriá. 2007. La psicología del uso de las palabras: Un programa de computadora que analiza textos en español. Revista Mexicana de Psicología 24: 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Raynauld, Vincent, and Josh Greenberg. 2014. Tweet, Click, Vote: Twitter and the 2010 Ottawa Municipal Election. Journal of Information Technology & Politics 11: 412–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reif, Karlheinz, and Hermann Schmitt. 1980. Nine second-order national elections. A conceptual framework for de analysis of European elections results. European Journal of Political Research 8: 3–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riera, Pedro, Raúl Gómez Martínez, Juan Antonio Mayoral Díaz-Asensio, Pablo Barbera Aranguena, and Jose Ramón Montero Gibert. 2017. Elecciones municipales en España. La personalización del voto. Revista Internacional de Sociologia 75: e062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Otero, José Manuel, Nieves Lagares Diez, Erika Jaráiz Gulías, and Paulo Carlos López López. 2021a. Emociones y engagement en los mensajes digitales de los candidatos a las elecciones generales de 2019. Cultura, Lenguaje y Representación 26: 229–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera-Otero, José Manuel, Nieves Lagares Diez, María Pereira López, and Erika Jaráiz Gulías. 2021b. Relación entre diversos usos de las redes sociales Twitter y Facebook emociones, y voto en España. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social 79: 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodon, Toni. 2020. The Spanish electoral cycle of 2019: A tale of two countries. West European Politics 43: 1490–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rúas-Araújo, José, Iván Puentes-Rivera, and María Isabel Míguez-González. 2016. Capacidad predictiva de Twitter, impacto electoral y actividad en las elecciones al Parlamento de Galicia: Un análisis con la herramienta LIWC. Observatorio (OBS*) 10: 55–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Ankita, and Udayan Ghose. 2020. Sentimental Analysis of Twitter Data with respect to General Elections in India. Procedia Computer Science 173: 325–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skogerbø, Eli, and Arne H. Krumsvik. 2015. Newspapers, facebook and twitter: Intermedial agenda setting in local election campaigns. Journalism Practice 9: 350–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobaci, Mehmet Zahid, Kadir Yasin Eryiğit, and İbrahim Hatipoğlu. 2016. The net effect of social media on election results: The case of twitter in 2014 turkish local elections. In Social Media and Local Governments: Theory and Practice. Edited by En M. Zahid. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 265–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taecharungroj, Viriya. 2023. “What Can ChatGPT Do?” Analyzing Early Reactions to the Innovative AI Chatbot on Twitter. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 7: 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tausczik, Yla R., and James W. Pennebaker. 2010. The psychological meaning of words: LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 29: 24–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, Nirmalya. 2022. MonkeyPox2022Tweets: A Large-Scale Twitter Dataset on the 2022 Monkeypox Outbreak, Findings from Analysis of Tweets, and Open Research Questions. Infectious Disease Reports 14: 855–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Social Media Family. 2022. VIII Informe Sobre el Uso de Redes Sociales en España. Available online: https://t.ly/EcJB- (accessed on 25 July 2023).

- Towner, Terri, and Caroline Lego-Munoz. 2016. Boomers versus millennials: Online media influence on media performance and candidate evaluations. Social Sciences 5: 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejos-Gil, Carlos Andrés. 2021. La campaña electoral a las alcaldías en Colombia: El papel de las redes sociales. América Latina Hoy 89: 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, José Manuel, and Giselle García-Hípola. 2020. Entre lo nacional y lo comunitario, de nuevo: Situando los resultados de las elecciones al Parlamento Europeo de 2019. In Elecciones Europeas 2019: Campaña Electoral, Voto y Liderazgo. Edited by Sergio Pérez-Castaños. Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch, pp. 37–69. [Google Scholar]

- van der Eijk, Cees, Mark Franklin, and Michael Marsh. 1996. What Voters Teach Us about Europe-Wide Elections: What Europe-Wide Elections Teach Us about Voters. Electoral Studies 15: 149–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zee, Sophie, Ronald Poppe, Alice Havrileck, and Aurélien Baillon. 2021. A Personal Model of Trumpery: Linguistic Deception Detection in a Real-World High-Stakes Setting. Psychological Science 33: 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, Michael, and Nicholas John Proferes. 2014. A topology of Twitter research: Disciplines, methods, and ethics. Aslib Journal of Information Management 66: 250–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

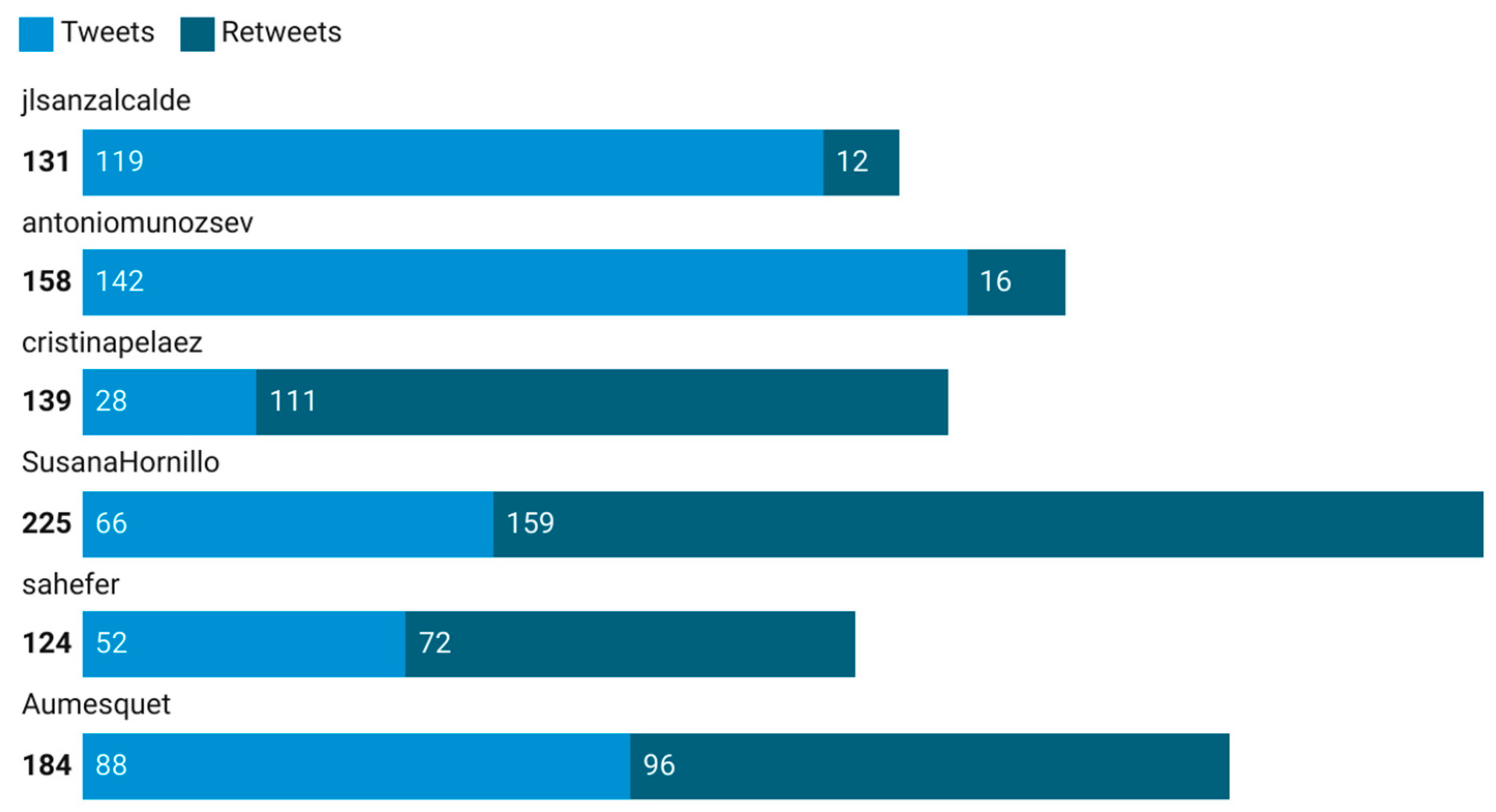

| Candidate | Party | User | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| José Luis Sanz | PP | jlsanzalcalde | 131 |

| Antonio Muñoz | PSOE | antoniomunozsev | 158 |

| Cristina Peláez | Vox | cristinapelaez | 139 |

| Susana Hornillo | Con Andalucía (UP) | SusanaHornillo | 225 |

| Sandra Heredia | Adelante Andalucía | Sahefer | 124 |

| Miguel Ángel Aumesquet | Cs | Aumesquet | 183 |

| User | Approach | N a | % a | Class | N c | % c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jlsanzalcalde | Local | 123 | 93.9 | Retweet | 10 | 7.6 |

| Tweet | 113 | 86.3 | ||||

| National | 8 | 6.1 | Retweet | 2 | 1.5 | |

| Tweet | 6 | 4.6 | ||||

| antoniomunozsev | Local | 146 | 92.4 | Retweet | 15 | 9.5 |

| Tweet | 131 | 82.9 | ||||

| National | 12 | 7.6 | Retweet | 1 | 0.6 | |

| Tweet | 11 | 7 | ||||

| cristinapelaez | Local | 121 | 87.1 | Retweet | 98 | 70.5 |

| Tweet | 23 | 16.5 | ||||

| National | 18 | 12.9 | Retweet | 13 | 9.4 | |

| Tweet | 5 | 3.6 | ||||

| SusanaHornillo | Local | 168 | 74.7 | Retweet | 111 | 49.3 |

| Tweet | 57 | 25.3 | ||||

| National | 57 | 25.3 | Retweet | 48 | 21.3 | |

| Tweet | 9 | 4 | ||||

| Sahefer | Local | 120 | 96.8 | Retweet | 69 | 55.6 |

| Tweet | 51 | 41.1 | ||||

| National | 4 | 3.2 | Retweet | 3 | 2.4 | |

| Tweet | 1 | 0.8 | ||||

| Aumesquet | Local | 173 | 94.5 | Retweet | 89 | 48.6 |

| Tweet | 84 | 45.9 | ||||

| National | 10 | 5.5 | Retweet | 7 | 3.8 | |

| Tweet | 3 | 1.6 |

| Candidate | N | WC | PE | NE | Anx | Ang | Sad | Inhib |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jlsanzalcalde | 131 | 5747 | 3.11 | 1.17 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.44 | 0.42 |

| antoniomunozsev | 158 | 10,064 | 3.41 | 0.38 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.04 | 0.21 |

| cristinapelaez | 139 | 4392 | 2.53 | 1.37 | 0.30 | 0.61 | 0.18 | 0.41 |

| SusanaHornillo | 225 | 7425 | 3.22 | 0.98 | 0.18 | 0.46 | 0.16 | 0.47 |

| sahefer | 124 | 3938 | 3.17 | 0.94 | 0.15 | 0.48 | 0.10 | 0.48 |

| Aumesquet | 183 | 6576 | 2.93 | 0.85 | 0.14 | 0.55 | 0.11 | 0.62 |

| User | Approach | N | WC | PE | NE | Anx | Ang | Sad | Inhib |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jlsanzalcalde | Local | 123 | 5522 | 3.06 | 1.16 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.45 | 0.42 |

| National | 8 | 225 | 4.44 | 1.33 | 0.44 | 0.89 | 0.00 | 0.44 | |

| antoniomunozsev | Local | 146 | 9214 | 3.35 | 0.37 | 0.11 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.18 |

| National | 12 | 850 | 4.00 | 0.47 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.00 | 0.47 | |

| cristinapelaez | Local | 121 | 3721 | 2.61 | 1.32 | 0.32 | 0.51 | 0.19 | 0.46 |

| National | 18 | 671 | 2.09 | 1.64 | 0.15 | 1.19 | 0.15 | 0.15 | |

| SusanaHornillo | Local | 168 | 5437 | 3.29 | 0.88 | 0.17 | 0.40 | 0.13 | 0.51 |

| National | 57 | 1988 | 3.02 | 1.26 | 0.20 | 0.60 | 0.25 | 0.35 | |

| sahefer | Local | 120 | 3822 | 3.24 | 0.97 | 0.16 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.50 |

| National | 4 | 116 | 0.86 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Aumesquet | Local | 173 | 6165 | 2.97 | 0.86 | 0.15 | 0.57 | 0.10 | 0.62 |

| National | 10 | 411 | 2.43 | 0.73 | 0.00 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.73 |

| User | Approach | N | WC | PE | NE | Anx | Ang | Sad | Inhib |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jlsanzalcalde | Local | 113 | 5275 | 3.05 | 1.21 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.47 | 0.44 |

| National | 6 | 155 | 4.52 | 1.94 | 0.65 | 1.29 | 0 | 0.65 | |

| antoniomunozsev | Local | 131 | 8593 | 3.31 | 0.4 | 0.12 | 0.2 | 0.05 | 0.19 |

| National | 11 | 806 | 4.09 | 0.37 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.5 | |

| cristinapelaez | Local | 23 | 696 | 4.02 | 2.16 | 0.57 | 1.01 | 0.43 | 0.43 |

| National | 5 | 227 | 3.08 | 3.08 | 0.44 | 2.64 | 0.44 | 0.00 | |

| SusanaHornillo | Local | 57 | 2155 | 3.85 | 0.74 | 0.28 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.6 |

| National | 9 | 443 | 2.93 | 0.9 | 0 | 0.68 | 0.45 | 0.45 | |

| sahefer | Local | 51 | 1671 | 4.07 | 0.78 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 0.12 | 0.3 |

| National | 1 | 31 | 3.23 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Aumesquet | Local | 84 | 3725 | 3.14 | 0.70 | 0.08 | 0.4 | 0.11 | 0.75 |

| National | 3 | 129 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.78 |

| User | Approach | Retweets | WC | PE | NE | Anx | Ang | Sad | Inhib |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jlsanzalcalde | Local | 10 | 247 | 3.24 | 0.00 | 0.4 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| National | 2 | 70 | 4.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| antoniomunozsev | Local | 15 | 621 | 4.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.16 |

| National | 1 | 44 | 2.27 | 2.27 | 0.00 | 2.27 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| cristinapelaez | Local | 98 | 3025 | 2.28 | 1.12 | 0.26 | 0.4 | 0.13 | 0.46 |

| National | 13 | 444 | 1.58 | 0.90 | 0.00 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 0.23 | |

| SusanaHornillo | Local | 111 | 3282 | 2.93 | 0.98 | 0.09 | 0.4 | 0.21 | 0.46 |

| National | 48 | 1545 | 3.04 | 1.36 | 0.26 | 0.58 | 0.19 | 0.32 | |

| sahefer | Local | 69 | 2151 | 2.60 | 1.12 | 0.19 | 0.7 | 0.09 | 0.65 |

| National | 3 | 85 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Aumesquet | Local | 89 | 2440 | 2.70 | 1.11 | 0.25 | 0.82 | 0.08 | 0.41 |

| National | 7 | 282 | 3.19 | 0.71 | 0.00 | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.71 |

| User | Approach | N | Retweets | Likes | Quotes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| jlsanzalcalde | Local | 113 | 5802 | 51.3 | 12,343 | 109.2 | 210 | 1.9 |

| National | 6 | 440 | 73.3 | 981 | 163.5 | 31 | 5.2 | |

| antoniomunozsev | Local | 131 | 7042 | 53.8 | 13,167 | 100.5 | 319 | 2.4 |

| National | 11 | 878 | 79.8 | 1513 | 137.5 | 52 | 4.7 | |

| cristinapelaez | Local | 23 | 591 | 25.7 | 1383 | 60.1 | 12 | 0.5 |

| National | 5 | 138 | 27.6 | 243 | 48.6 | 4 | 0.8 | |

| SusanaHornillo | Local | 57 | 3771 | 66.2 | 6098 | 107.0 | 138 | 2.4 |

| National | 9 | 437 | 48.6 | 824 | 91.6 | 14 | 1.6 | |

| sahefer | Local | 51 | 798 | 15.6 | 2348 | 46.0 | 53 | 1.0 |

| National | 1 | 60 | 60.0 | 131 | 131.0 | 5 | 5.0 | |

| Aumesquet | Local | 84 | 1561 | 18.6 | 2454 | 29.2 | 28 | 0.3 |

| National | 3 | 50 | 16.7 | 76 | 25.3 | 2 | 0.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-García, D.; Trujillo, J.M. Emotions of Candidates on Twitter in the 2023 Seville City Council Election: A Second-Order Campaign? Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12110590

García-García D, Trujillo JM. Emotions of Candidates on Twitter in the 2023 Seville City Council Election: A Second-Order Campaign? Social Sciences. 2023; 12(11):590. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12110590

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-García, David, and José Manuel Trujillo. 2023. "Emotions of Candidates on Twitter in the 2023 Seville City Council Election: A Second-Order Campaign?" Social Sciences 12, no. 11: 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12110590

APA StyleGarcía-García, D., & Trujillo, J. M. (2023). Emotions of Candidates on Twitter in the 2023 Seville City Council Election: A Second-Order Campaign? Social Sciences, 12(11), 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12110590