Abstract

Political elite studies so far have often dealt with career paths before entering a particular political position, focusing mostly on individual states of a career. However, they have consistently neglected what comes after a political office and the temporal–sequential character of biographies. This paper addresses these two issues. Using sequence analysis techniques, it examines the post-cabinet careers of ministers from the German states in the period 1945–2014 using a newly created, original dataset containing 1400 trajectories and over 12,000 coded person years. The descriptive analysis shows partly significant differences in post-cabinet careers by gender, state, decade, and last ministerial portfolio, but less so by party membership. Three of the five clusters found represent comparatively homogeneous post-cabinet career structures. Whereas in the early years of the republic most politicians did not have a subsequent (long) professional career after leaving office, switching to the private business sector and, above all, remaining in politics at the state level, represent the two most prominent career paths. A springboard career in federal politics, on the other hand, is rare, but certainly possible. From a methodological point of view, this study shows the potential, but also the problems of sequence analysis for research on political elites and offers ideas on how to continue with this approach.

1. Introduction

Studies of political elites have long focused primarily on pathways into political office, trying to explain why certain politicians make it to prestigious positions, such as cabinet minister or member of parliament, while others do not (e.g., Dowding 2009; Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson 2009; Kerby 2009; Scarrow 1997). For those politicians who reach these positions, other studies research which factors determine their length in office (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones 1997; Fischer et al. 2012; Huber and Martinez-Gallardo 2008; Jäckle 2013). The period after a politician has left the cabinet or parliament has so far been less intensively examined (but see Claveria and Verge 2015). This lacuna is the starting point for the present analysis. At first glance, analyzing the careers of former high-level politicians might seem less interesting than their careers in office. However, knowing that these people were able to establish important relationships during their time in office and that they are likely to continue to have an interest in contributing their ideas to public discourse and helping to shape politics, the economy, or other social spheres even after they have left office, then it is essential to look at what these people have done after they have left political office. This article has a twofold goal: first, from a methodological point of view, it presents sequence analysis as a tool to systematically structure career spells and to compare them; second, with its focus on the career steps that follow an already high political position, it provides initial insights into the central questions of political elite research that have been little-studied so far. For both objectives, the state level in Germany is a very suitable object of study. This is because in Germany, as a federal country, the state level has important competences and can therefore be assumed to represent an independent career option for politicians. One interesting question, for example, is whether in Germany the state cabinet serves as a springboard for positions at the national or the international level. With 16 states and several decades of democratic rule, there are also enough data available to exemplify the potential of sequence analysis. The following paragraph presents the state of research on executive careers in Germany and develops three blocks of questions that will be answered in the remainder of the article with the help of sequence analysis procedures on the basis of a newly created dataset consisting of more than 1400 post-cabinet careers from the German states.

2. Research on Ministerial Careers in Germany and Three Blocks of Research Questions

For quite a long time, studies on political elites in Germany have been engaged primarily with parliamentarians (Best et al. 2011; Gruber 2008; Herzog 1975; Küpper and Wenzelburger 2013; Patzelt 1997). In recent years, the focus has shifted toward studying executive and judicial elites as well (Jäckle 2016). The works on executive elites mainly describe the situation of the federal cabinet, focusing particularly on hiring and firing mechanisms (Ali 2003; Fischer et al. 2006; Fischer and Kaiser 2009a), or they investigate under which circumstances the Bundestag can serve as a springboard for a career in the federal government (Fischer and Kaiser 2009b, 2010). Nevertheless, these studies not only exclusively focus on the federal level, but some also look at the state (Bundesländer) governments (Jäckle 2012, 2013; Vogel 2009). However, students of German political elites have traditionally regarded the subnational level only as a recruiting pool for positions at the federal level, and this thinking guided their analyses (Fischer and Kaiser 2011). While the relevance of the subnational level for positions at the federal level may indeed exist in some instances, Borchert and Stolz make a valid point when they argue that the state level—at least for members of the state legislatures—is a desirable goal in its own right in terms of job security, professionalized working environment, and even status. On the other hand, movement ‘up the ladder’ toward a higher level (national, EU) is often not particularly supported by the own party, is risky and, in light of a cost–benefit analysis, is not worthwhile for many state legislators (Borchert and Stolz 2011, p. 219). Interestingly, Rodriguez-Teruel (2011) shows for Spain, which in terms of federalism is relatively similar to Germany, that ministers in the federal government mostly make their way through local and regional government positions and not through the Spanish national parliament.

Firstly, the existing studies help us to understand who has good chances to enter a cabinet, i.e., what the requirements of becoming a minister are. Secondly, we now know much more about the factors explaining why some ministers stay in office for long time periods, while others must leave their office after just a few months. However, one part of the picture is still obscure: the post-cabinet career. What do ministers do after they have left the cabinet? In general, only little is known about the late careers of politicians in general. A study by Herrick and Nixon (1996) analyzes the follow-up positions of members of the US Congress. A similar approach is taken by Best et al. (2008) within their German survey of parliamentarians (“Abgeordnetenbefragung”).1 For executive elites, there is even less systematic knowledge available. We have to look back to the early 1990s to find at least some works that focus on the post-cabinet careers of ministers at the national level. Blondel (1991) compared the post-ministerial careers of politicians in fourteen Western European systems, while Nicholls (1991) examined the opportunities of cabinet members within the US system. Both came to the conclusion that in nearly all cases, a cabinet position constituted the peak of a political career. This finding does not come as a big surprise if we consider the extremely limited number of higher political positions a national cabinet member could possibly ascend to. Nicholls, for example, shows that only 6 out of the 237 cabinet members that he had examined became president after their time in cabinet (Nicholls 1991, pp. 160–61). On the other hand, he reveals that cabinet membership in the USA helps to promote a career in private business after the government position (Nicholls 1991, p. 169). More recently, there have also been works on the post-parliamentary career of parliamentarians in Great Britain, the Netherlands, and Germany (Byrne and Theakston 2016; Claessen et al. 2021; Würfel 2018). With respect to post-cabinet careers, Stolz and Fischer (2014) present the first systematic account of the post-cabinet careers of regional state ministers in Germany. Their descriptive analysis is based on the first appointment after leaving the cabinet. While this is clearly an interesting first step, it does not present the full picture, because any positions after the first post-cabinet position are neglected. Dörrenbächer (2016) focused on the question of which federal ministers in Germany go through the so called “revolving door” and have a second career in private business. She finds that a revolving door is not very common in Germany although the share of former ministers who entered the private sector after leaving cabinet has increased significantly since the 1980s. Another comparative analysis of the very first occupation that 430 former ministers from national cabinets held after leaving the cabinet, conducted in 23 countries, shows “that serving in executive office is not just a career tout court but it allows moving to other positions in politics, the international arena or the private sector” (Claveria and Verge 2015, p. 830).

Altogether, it seems to be an interesting question whether there are different possibilities for politicians to take their political career to an even higher level or to take well-paid positions in the private sector. To answer this, it is necessary to look at a political level from where upward mobility to better political positions is actually feasible. Therefore, I will concentrate on post-cabinet careers of members of the German state governments. Focusing on the time after ministers have left their positions in government helps to answer three blocks of questions that have not been systematically looked at until now:

- (1)

- Does it help to be a cabinet member of a state government to further a political career after the time in the state executive? In other words, is the state cabinet position just a staging post on the road to a more prestigious political position and thus a stepping stone that helps to achieve ambitious political plans, or is it a dead end for any career in German politics? Are there any frequently occurring trajectories? Furthermore, can we identify factors supporting or hindering such multilevel political careers?

- (2)

- What types of post-cabinet careers do we find? What other, nonpolitical positions do former ministers occupy in the private sector, in foundations, or in academia? Are these jobs well-paid positions for old party soldiers who can no longer be kept in the political business (e.g., because of their age or because of scandals), or is a well-paid job in lobbying even more desirable than a high-ranking job in politics?

- (3)

- Are there any significant differences within the post-ministerial career pattern? Does it change through the decades? Are there significant differences according to the party of the minister, the gender, or the state he or she has been working in?

In order to analyze these questions, I will apply the method of sequence analysis. This is a structure-identifying technique originating from the 1980s. It was introduced into the social sciences by Andrew Abbott (1983, 1984, 1995) and has already been fruitfully applied to political career studies, in most cases, with respect to the question which biographical steps precede a specific political position, e.g., within parliaments (Binderkrantz et al. 2020; Kerby and Snagovsky 2021; Manow 2012; Ohmura et al. 2018; Turner-Zwinkels and Mills 2020) or supreme courts (Jäckle 2016; Lindholm et al. 2022). These “pre-career” studies have helped to identify distinct pathways and thereby supplemented the aforementioned recruitment studies with a more holistic picture of the complete biography, culminating in a distinct political position. However, sequence analysis is also well suited to analyze “post-careers”, i.e., the careers after leaving a certain political position. This is how sequence analysis is used in this article.

3. Materials and Methods

The data I used consist of post-ministerial careers of ministers from all 16 German states that started their (last) ministerial appointment in the time span between the establishment of the first democratic cabinets2 and 31 December 2010. Sequence spells which are still ongoing as of 1 August 2014 were removed from the dataset. To glean a better insight into the complete career patterns, I not only examined the position directly following the ministerial job, but also coded all positions the former ministers occupied for the subsequent ten years. In total, this amounts to 1400 post-ministerial career trajectories (i.e., a matrix of 10 × 1400 data points = person years). The dataset is organized in state sequence (STS) format. Each sequence starts with the first year after the end of the ministerial spell. “The successive states (statuses) of an individual are given in consecutive columns” (Gabadinho et al. 2011, p. 28). In total, I coded 28 different post-cabinet occupations. Apart from the three major groups (p_* = positions within politics; e_* positions within economy/the private sector; and j_* positions within judicial system), positions within academia, administration, or diplomacy were coded as well as pension/retirement or death. The codebook can be found in the Appendix A (Table A1). Ministers who served more than one spell are coded multiple times. This is sensible as every ministerial spell provides for a distinct possibility to analyze the subsequent career path. The snapshot in Table 1 gives an impression of what the dataset looks like.

Table 1.

The sequence dataset of German regional state ministers’ post-cabinet careers.

Apart from the name, gender, party, and state the minister has served, the dataset includes the exact date when the ministerial spell ended (and thus when the post-ministerial career began), the last portfolio the minister was working in and—the most important information for further analysis—the positions the former minister held in the ten years following the end of the ministerial spell. Franz Heitgres, for example, was a member of the communist KPD (Communist Party of Germany) in the first Senate in Hamburg after WW II. Until 1950, he was the chairman of a committee representing former political prisoners. The first two years are thus coded as “foundation”. After this time, there is no further information available and thus I coded the following years as “no data”. Empty cells are only possible if the ten years of the post-ministerial career have not elapsed by the end of the data-coding period (as of August 2014). An example is Elisabeth Heister Neumann. Her spell as minister of education in Lower Saxony ended in April 2010. Therefore, only four years of post-ministerial career can be coded for her (2010–2014). The last six cells are thus empty.3

An obvious problem with this approach is the fact that a person can occupy multiple positions at the same time. For example, a former minister can still be active in her party (perhaps at the regional level), can be a member of a city council, work as a lawyer, preside over a foundation, and act as a chairman of a board of directors. All these occupations and possibly more could, in theory (and in practice often do), coincide with each other. My solution to this problem is, on the one hand, based on the basic idea of this article to better understand political careers and therefore to focus more on positions within the political sphere and, on the other hand, it is a pragmatic one that is prone to some bias. I coded only the most relevant position, regarding political positions in general as more relevant than all others, positions at the federal level as more relevant than positions at the state level, and executive positions as more relevant than legislative positions. For all other multiple positions, I attempted to figure out which occupation the former minister would spend the most time for—and only coded that one.4

I collected the data from a wide range of online resources5, trying, wherever possible, to crosscheck the codes with at least two or three different sources. Yet, there are still a number of years for which no information about the position of the former minister was accessible. These have been coded as “no data”. Such a code, nevertheless, also tells a story, as it illuminates that these former cabinet members are no longer in any relevant political and, in most cases, also in no other noteworthy position. They left the political, economic, and social arenas and became mere private persons.

I used sequence analysis techniques to describe the post-ministerial careers and to identify potential group structures within these trajectories. For an overview of the basic ideas behind the method of sequence analysis see MacIndoe and Abbott (2004); Blanchard et al. (2014); Mills (2011); Cornwell (2015); and Jäckle (2017). In contrast to survival/event history models, which focus on the explanation of certain transitions from one state to another and have been applied in political elite studies in general and ministerial career studies in particular since the 1990s (Bienen and van de Walle 1991, 1992; Huber and Martinez-Gallardo 2008; Jäckle 2011), sequence analysis examines biographies with respect to their different partitions while still keeping the holistic view of the complete sequence: sequence analysis simultaneously takes into account the states, their order, and their durations. This feature makes it a more appropriate method to examine complete biographies or, as in this paper, longer periods of post-ministerial careers than those techniques focusing solely on certain single states, such as the first position immediately after the ministerial spell ended or approaches that look at the whole experience of a person, cumulating all career stages without taking into account the ordering or the duration of them.6 In other words, the final behavior of actors within social systems can only be understood when the “chronological succession of these phases” (Gauthier et al. 2014, p. 3) is known. As far as the careers of political elites are concerned, methods that focus solely on certain events may miss a relevant part of the story, while “sequence analysis can play a fundamental role in bringing the much neglected trajectory concept, the actual ‘course’, back into the life course” (Aisenbrey and Fasang 2010, p. 450) of politicians. For an introduction to the basic concept of sequence analysis for the study of political careers, the data structure required for this purpose, the steps of the analysis, and the problems that arise in the context of political elite studies due to the differences from genetic analysis—for which sequence analysis procedures were actually originally developed—see Jäckle and Kerby (2018).

In this paper, I describe the sequences of careers at an aggregate level without digging deeper into the careers and without using the more sophisticated methodological possibilities that sequence analysis offers. For the latter approach, attempting to find distinct clusters of post-ministerial careers, a longer period under investigation (more than 10 years) would clearly be helpful. However, to provide at least a glimpse into the possibilities of using the sequence analysis approach to study political careers, the dataset for this paper, which includes only a time period of ten years, can serve as a good starting point. Complementing the inductive nature of this study, the graphical representations shown in the remainder of this article best serve our purpose to identify similarities and differences within the post-cabinet careers of German regional ministers. In general, there are two ways of presenting sequence data. Both of them will be used in the following analysis:

- (1)

- Regular sequence plots are ultimately a graphical translation of the STS format structure presented in Table 1. Each horizontal line represents one post-ministerial career, and the different colors represent the different positions. These plots are well suited if you are interested to see which career steps follow each other for every single case. However, regular sequence plots are often too fuzzy to gain insight in any general patterns. Figure A1 in the Appendix A depicting the complete dataset as a regular sequence plot can serve as an example.

- (2)

- In transversal frequency plots, each column (=year) gives the frequencies of the statuses. These plots help to understand the general patterns in the data and are thus the most appropriate way of presenting sequence data for our purposes here.

Both types of plots can also be applied either to the whole dataset or to specific subgroups of the data (e.g., party, decade, or last ministerial portfolio) in order to identify certain differences between the post-ministerial career trajectories in an exploratory way.

However, sequence analysis does not stop here. The description of the whole dataset, accompanied by group comparisons, is often only a preliminary step. The sequence data can then be used to identify certain patterns within the data, i.e., certain types of careers which, on the one hand, include similar individual career trajectories and which are, on the other hand, distinct from other types of careers. For this purpose, clustering algorithms can be applied to a distance matrix calculated from the sequence data. Different types of similarity measures exist that can be applied. The most common are variants of the optimal matching approach (OM). The basic idea behind OM is to transform a sequence X into another sequence Y using different types of transformation operations (insertions, substitutions, and deletions). For each of these operations, a certain cost is set. Setting the costs is the crucial aspect of the OM procedure.7 In the end, all OM algorithms can ultimately be traced back to the question of how costly substitutions are compared to indel operations (insertions and deletions) (Jäckle 2017, p. 344). The OM algorithm then finds the specific transformation procedure that has the lowest costs. The number of operations necessary for this lowest-cost transformation is defined as the distance between sequences X and Y (Lesnard 2014, p. 40; Robette and Bry 2012). One specific variant of this approach—the longest common subsequence (LCS)—which is also known as the Levenstein II distance, will be applied here (see Elzinga 2007). It is generally regarded as a good option in “biographic research as it measures the resemblance of career trajectories in a way that comes close to social scientists’ understanding of the term similarity of trajectories” (Jäckle and Kerby 2018, p. 125). For LCS, the replacement costs are set at least twice as high as the indel costs, which means that replacements are never used for sequence transformations, because the same result can also be achieved at lower costs via insertions and deletions. Consequently, sequences are seen as similar if they have long common subsequences (Lesnard 2014, p. 41). To illustrate the LCS concept, let me assume the following three example sequences (see Table 2):8

Table 2.

Example demonstrating the concept of the longest common subsequence (LCS).

To identify the LCS and its length, we compared the sequences with each other. The common subsequence ‘A U’ occurs both in X and Y. No other subsequence is common between these two sequences. The length of this common subsequence is two. Comparing X and Z, there is one subsequence of the length four: ‘U A P U’ appears in X as x1x2x4x5 and in Z as z1z2z3z4. The same holds true for Y and Z: The complete sequence of Y can be found in Z in the positions z2z4z5z7. Again, the LCS is four stages long. By using this information on the LCS, distance and similarity measures can be calculated (see Elzinga 2007, p. 15).

After calculating the distance matrix, different options exist for extracting groups of careers that follow similar patterns. One option presents latent class analyses based on the raw sequence data. This approach is nevertheless better-suited in the case of genome sequencing and has its issues if the timing of sequence changes is relevant, as is the case in biographies. A second option is multidimensional scaling, which, however, cannot clearly differentiate between certain groups and produces dimensions that often cannot be readily interpreted. The most common approach to find a group structure within the career trajectories is thus cluster analysis (Barban and Billari 2012). Hierarchical agglomerative methods are the most common, especially Ward’s algorithm, because the clusters it finds have a high degree of internal homogeneity and simultaneously differ maximally from the other clusters—a property that is advantageous for finding sequence groups.9 For a given number of clusters, hierarchical cluster algorithms provide the answer to the question of which sequence should be sorted into which cluster. They cannot provide a definitive answer to the question of how many clusters best represent the data (Jäckle 2017, pp. 350–51). For the latter, it is necessary to resort to procedures such as dendrograms, inverse scree test, and silhouette analysis (Rousseeuw 1987) or multidimensional scaling plots (Piccarreta and Lior 2010).

After presenting the sequence data in a descriptive way, the following analysis applied the LCS metric within the OM approach to calculate the distances between the post-ministerial careers, clusters these distances using a hierarchical agglomerative clustering approach based on the Ward algorithm, and tests the optimal number of clusters via inverse scree plot and silhouette analysis.

4. Results

In this section, the results of the analysis are presented. Before looking at the post-ministerial careers from a sequence analysis perspective, I will give a short overview of the dataset using descriptive statistics. In the sequence analysis, I then firstly give an overview of all post-cabinet careers, after which I will compare groups of post-ministerial careers to find patterns in order to answer the research questions.

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

In total, the dataset consists of 1400 post-cabinet career trajectories made up of 1283 individuals. A total of 1171 politicians appear only once in the data; i.e., they left the cabinet and did not become a minister at the state level within the following 10 years. A total of 107 politicians appear twice, and five politicians even appear three times. Although they are an exception to the rule, these “repeated returners” to state cabinets are particularly interesting. Two of them will be presented here briefly: Hans Ehard and Lore Peschel-Gutzeit.

Hans Ehard (CSU) was minister of justice for four months in Bavaria in 1945 before he was downgraded to a state secretary in the cabinet of Wilhelm Hoegner. In late 1946, Hans Ehard became the first Bavarian prime minister elected by the Bavarian Landtag (the two cabinets before had been appointed by the American-occupying power). He was lucky, as the CSU party leader at that time, Josef Müller, faced a denazification trial during the time of the election. While Müller was found not guilty, Ehard had already been elected by the time the trial had ended. Ehard remained in power for eight years, the first and also the last time a non-CSU government took power. During 1954 and 1960, Ehard was the president of the Bavarian Landtag. In 1960, at the age of 73, he became prime minister again. In 1962, he changed to the ministry of justice, but remained in the cabinet until 1966, when he left politics. Ehard can be seen as a typical party politician who had a strong backing in parliament but who also had the will to stay in high-level politics up to an old age.

Lore Peschel-Gutzeit (SPD) started her career as a judge. In 1991, she entered the cabinet as an external expert, becoming the minister of justice in the city state of Hamburg. After the elections in 1993, when the SPD had to form a coalition government, Peschel-Gutzeit moved on to Berlin, where she again took office as minister of justice (following Jutta Limmbach, who had been appointed as a justice at the Federal Constitutional Court). In 1997, she went back to Hamburg as minister of justice. In 2001, the SPD–Green government lost the elections and Peschel-Gutzeit, who had never been a member of a parliament, left politics to become a lawyer. Lore Peschel-Gutzeit is a prime example of an expert minister who kept the same portfolio even in different cabinets in different states.

For 241 trajectories, the full 10 years of the post-cabinet career could not be observed due to the end of the observation period in 2014. These non-observed post-ministerial career trajectories, which started for politicians who left the office in 2005, account for a total of 1195 person years. This compares with a total of 12,805 coded person years in the dataset, where “no information available” had to be coded, as in these cases no information on the position a former minister held in a particular year was accessible.

Looking at the very first step after leaving the cabinet, I found that more than 41% of the post-cabinet trajectories start with a position at the state parliament. Only very few (about 1.2%) continue with a ministerial position at the state level (i.e., move to another state government). Upward movement to the federal level is possible, either to the Bundestag (4.3%) or to the federal government as chancellor (the only two examples are Kurt-Georg Kiesinger and Gerhard Schröder), as minister (1.7%), or as state secretary (0.9%). These numbers suggest that a direct move from a state cabinet to the federal cabinet is not uncommon, yet from the state cabinet point of view, it is also not the most obvious career option. This applies even more to the case of upward mobility toward the EU. Here, I found only 10 cases (0.7%) of state ministers who move directly to a position within the EU (Parliament, Commission, and Agencies) after leaving the cabinet. Taking all political positions together (including local and party positions), about 55% of the post-cabinet trajectories start their first year after leaving the state cabinet with a political position. This is not an overly high number. Comparing this value to the last-observed year (10 years after leaving the cabinet), I found that only 22.4% were still working in politics. By far the largest loss is found in the category of members of state parliaments (from the aforementioned 41% in the first year to only 8.5% who were still members of a state parliament 10 years after leaving the cabinet). Interestingly, the numbers for those cabinet members moving to the private business sector, either as a self-employed person or as manager/member of board of directors, etc., within a bigger company, do not drop significantly during the observation period of ten years after leaving government. They stay more or less constant at a total of approximately 12%.

These numbers already show that concentrating solely on the very first step after leaving the cabinet is probably an oversimplification, which leaves aside important information on the further trajectories. The following sequence analysis tackles this problem by focusing on the complete ten years after leaving the cabinet, presenting a more holistic picture of post-cabinet careers.

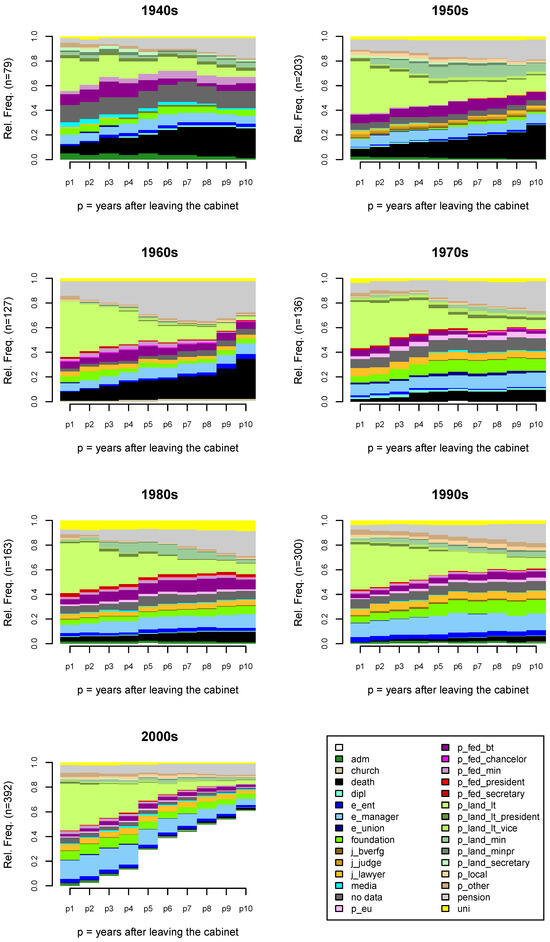

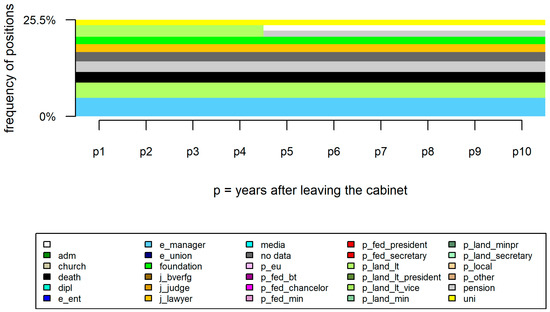

4.2. The Overall Sequence Picture

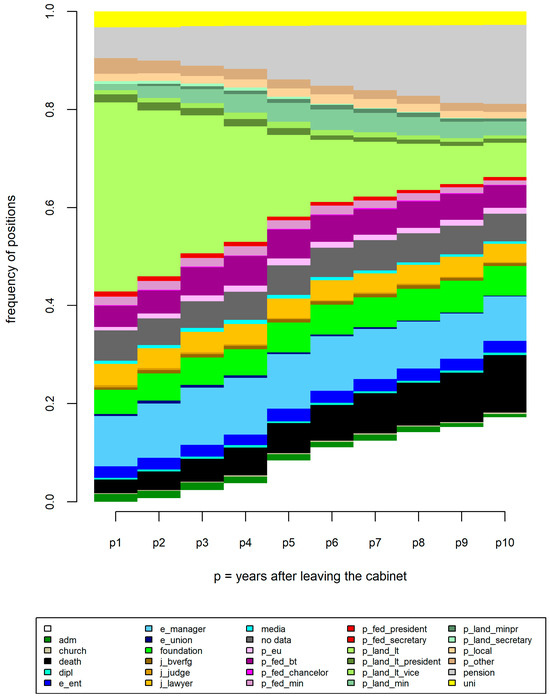

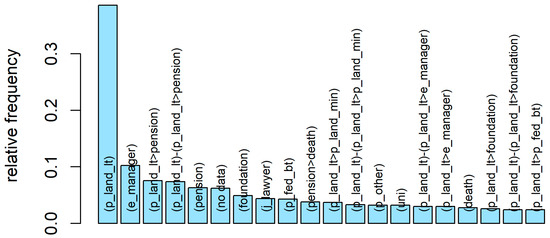

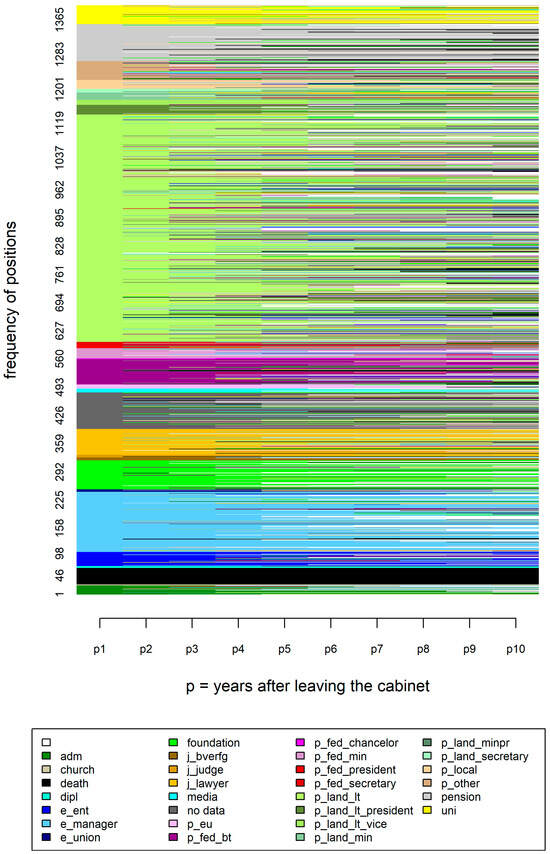

The transversal frequencies in Figure 1 already show which occupations are often found for former state ministers and which are very rare. In the first year after leaving the cabinet, more than 40 percent of all ministers continue their political work at the state level as a member of the state parliaments (the important posts of the president and vice-president of the state legislatures are depicted as separate colors). Member of a state parliament is also the only category that continuously shrinks over the ten years. This indicates that being a member of a state parliament is a good opportunity for many of the former ministers immediately after leaving their executive position. But most of them subsequently turn to other positions. It seems also quite unlikely that someone who has left the state parliament either for a higher position on the federal or EU level or for a nonpolitical position will return to state parliament in the years after. Most of the other positions exhibit more or less the same frequency during the whole ten years, except three categories that become more frequent through time: Pension/retirement, death, and the white cells indicating that the ten years of the observed post-ministerial career have not elapsed by 2014. The first two increasing frequencies are clearly produced by the aging of the sample, while the last one is due to the ending point of the observation period in 2014.

Figure 1.

Transversal frequency plot of all post-cabinet careers. Note: e_* positions within economy/private sector; j_* positions within judicial system; p_* = positions within politics; for all codes see Table A1 in the Appendix A.

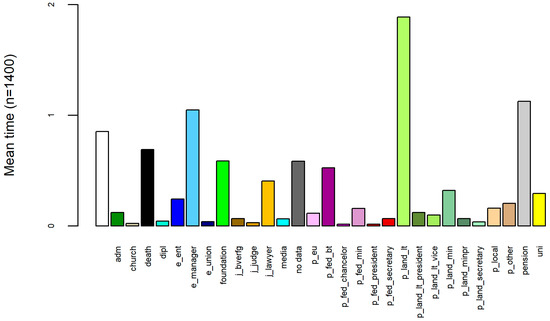

According to Figure 1 and Figure 2, which present the complete data by the mean durations within the states, the most relevant post-ministerial occupations are “manager” (salaried), “foundation”, “lawyer”, “no data”, “member of the Bundestag”, and “return to a state cabinet as a minister”. Although they are not the largest bars, the graph shows that advancement to a higher political position either at the state level as prime minister of a state; at the federal level as a member of the Bundestag, the Federal Government, or even the Federal President; or at the European level is a real possibility for at least some of the state ministers. Of course, a potential upward movement—particularly to the Federal Government—is restricted by the number of positions available at this level. To obtain a better picture of how relevant a previous career as a minister in a federal state is for the chance to enter the federal government, it makes sense to take a reverse perspective and ask how many of the federal ministers have previously been regional ministers (or even minister presidents) or have previously headed another federal ministry. Table 3 shows this for the Federal Chancellors and the four most important ministries (ministry of finance, ministry of foreign affairs, ministry of economics, and ministry of the interior). With seven out of nine chancellors having previously been a member of a state government (either as prime minister or as minister), the great relevance of the state level for the selection of the most powerful office in Germany is evident. Without experience in state cabinets, it is obviously almost impossible to become chancellor. The only two exceptions were Konrad Adenauer, the first chancellor, and Angela Merkel. Yet, at the same time, more than half of the chancellors also had experience as a federal minister. In the case of the four important federal ministries, it is evident that the ministers have often previously worked in the federal cabinet as ministers in other departments. This is particularly the case in the foreign ministry where 11 out of 16 ministers of foreign affairs had previously been other federal ministers. In contrast, persons who have been a member of government at the Länder level are less often found in federal cabinets. For example, only 19% of the federal interior ministers had previously held a position as a cabinet member at the Länder level.

Figure 2.

Mean duration in each category.

Table 3.

Former cabinet positions at regional level and/or federal level of members of the Federal Government (1949–2023).

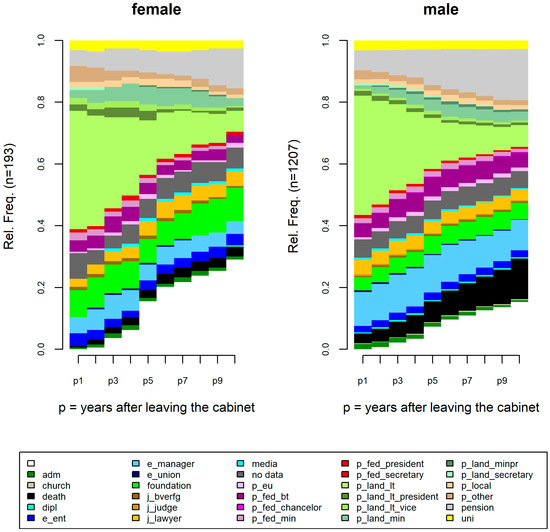

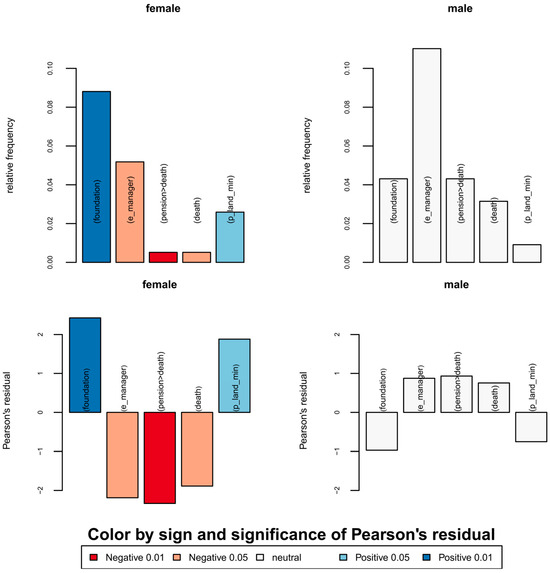

4.3. Gender Differences

Comparing the transversal frequencies for former female and male ministers shows only minor differences for most categories (see Figure 3). The only more significant deviations are that fewer women retire or die during the ten years after leaving the cabinet and that fewer reach the Bundestag or work as managers10, while they are often more active in foundations performing charitable work after their cabinet careers. The category “foundation” of course includes not only unpaid, charitable work, but also paid positions, e.g., in large party or corporate foundations. However, a more detailed analysis of former ministers whose first post-cabinet position is in a foundation (n = 76) shows that there is not much difference between men and women: In both groups, about 57% have positions in nonprofit/voluntary foundations coded as unpaid, while 43% have paid positions in large foundations after leaving the cabinet. So, while former female ministers are more likely to work in foundations compared to their male counterparts, there is no significant difference between men and women working in foundations in terms of the nature of the work for the foundation (voluntary or paid).

Figure 3.

Transversal frequency plots by gender.

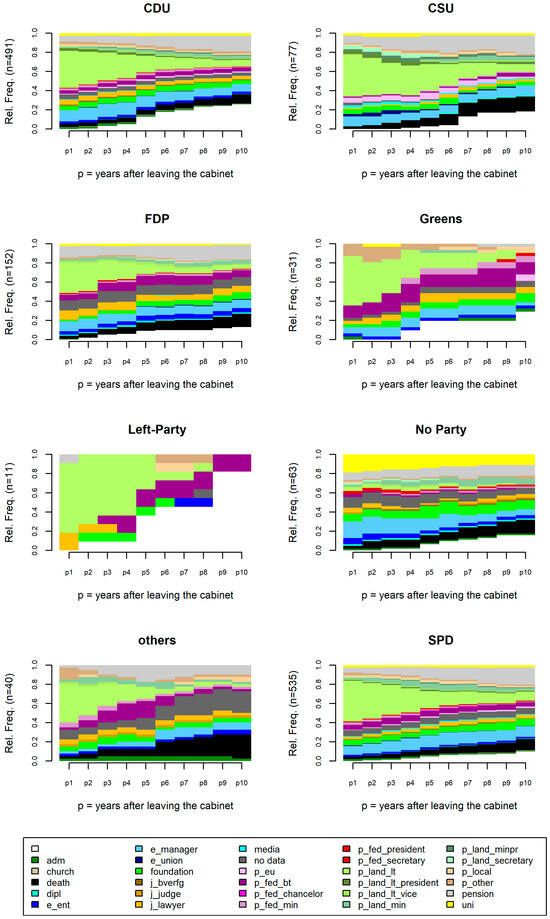

4.4. Party Effects?

One of the knee-jerk questions asked by political scientists is about the consequences of parties and party affiliation. In the context of this paper, we may ask whether ministers from different parties also pursue substantially different post-ministerial careers. For example, given the clearly distinct socialization of FDP and SPD ministers, we could assume that the former may exhibit a higher probability of working as entrepreneurs or self-employed consultants, while Social Democratic ministers may turn more often to local politics, where a bigger party like the SPD has better chances than the small FDP (e.g., when it comes to the election of a mayor). Figure 4 below gives an answer to this and other questions regarding differences among the major German parties within the post-cabinet careers of their ministers.

Figure 4.

Transversal frequency plots by party.

As presumed, former FDP ministers indeed exhibit the highest probability of becoming self-employed/entrepreneurs in the follow-up of their political career at a state government. And the second point is true as well: SPD and CDU members—the largest parties—turn more often to local politics in the ten years after leaving the cabinet. Furthermore, there are some other conclusions that can be drawn from the pictures. While an upward move to the federal level (either Bundestag or cabinet) makes up about 5–10 percent for most parties, the Bavarian CSU is an exception. The most common higher political level CSU ministers head for is not the federal, but the European level. This may be due to the fact that for many CSU politicians, working in Berlin together with, or in many cases against, the sister party CDU is not a very desirable option. Also, in Bavaria, working as a regional minister is sometimes regarded as even more prestigious than a ministerial job at the federal level.11 Another clear finding is that nonparty ministers have the highest probability of all ministers of working as professors at a university (or in a research institute) after their cabinet career. This does not come as a surprise if you think about the possible pool of expert ministers because in many cases, they originate from academia and return to these positions afterward. In general, nonpartisan expert ministers have a low probability of staying in politics after leaving the cabinet. Out of the 64 nonpartisan ministers in the dataset, only 8 took positions within the state or federal executive (e.g., as state secretaries) within the ten years after leaving their regional cabinet position. The final point I want to make here is not as much about differences among the parties as it is about similarities: There are no significant differences between the two big parties CDU and SPD, showing their highly professionalized party structures, which do not deviate much from each other and thus facilitate very similar post-cabinet career patterns.

4.5. Consequences of the Last Portfolio for the Post-Ministerial Career

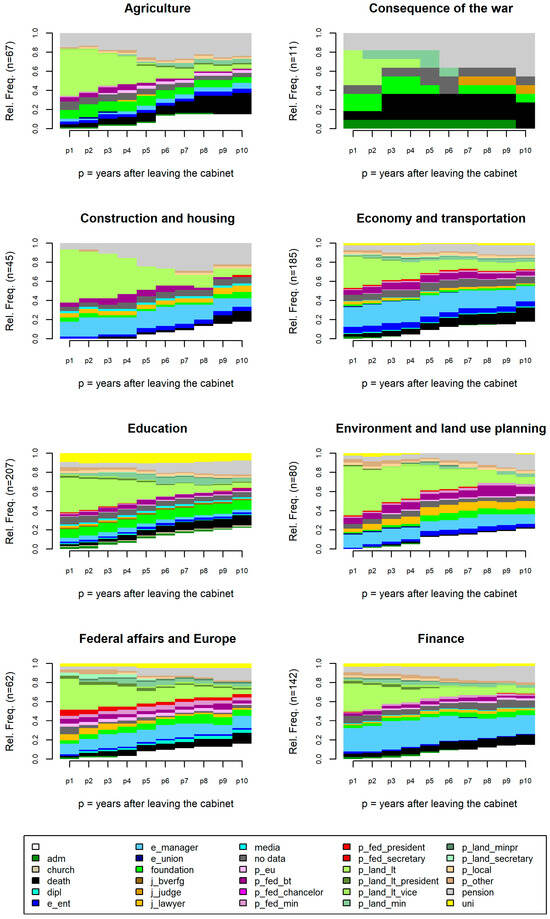

In this section, I cluster the post-ministerial careers according to the last portfolio the minister held before leaving the cabinet. Again, there are great variations (see Figure 5 and Figure 6):

Figure 5.

Transversal frequency plots by last portfolio (part 1).

Figure 6.

Transversal frequency plots by last portfolio (part 2).

- (1)

- For a position within the private sector (either self-employed or as an employee), the best starting points are the ministries of economy and transportation, finance, or construction and housing.

- (2)

- The best chances to become a member of the federal government lie with prime ministers, ministers for federal affairs, and the heads of the state chancelleries. Because all of these positions already work together closely with the federal government, this might explain their superior chances to switch to the federal level. Other ministries, such as the ministries of agriculture, education, or justice, provide fewer opportunities to make it to the federal level.

- (3)

- Not surprising is the fact that ministers of the interior and justice often continue their careers as lawyers or judges.

4.6. Changes through Time

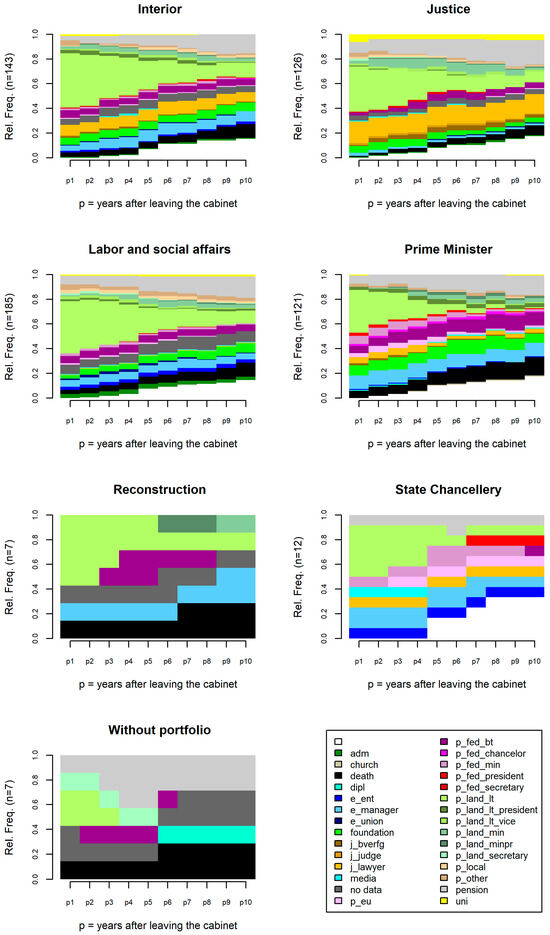

The final categorization that will be analyzed here in detail is by decade (see Figure 7). I used the date when the minister left her office and started her post-cabinet career to group the transversal frequency plots. Indeed, there are systematic differences within the plots.

Figure 7.

Transversal frequency plots by decade of the last day in cabinet office.

- (1)

- Until the 1960s, up to 20 percent of all ministers died during the observed ten years after they left the cabinet. This percentage is much lower in the following decades. On the one hand, this is due to a trend toward younger cabinets and, on the other hand, due to the increasing life expectancy in Germany.12

- (2)

- Especially in the 1960s, “pension” is a large position. This indicates that in that decade, the position of a state minister represented the apex of a political career for many politicians. They reached this high level mostly at the end of their professional career and then went on to their pension and/or died. It is astounding that in the 1960s, only about 40 percent of the ministers were either not dead or in retirement ten years after leaving the cabinet. In the 1990s, this number rose to about 85 percent.

- (3)

- Work in foundations has expanded since the 1970s.

- (4)

- Positions in the private sector and as lawyers have also become more frequent, especially since the 1990s.

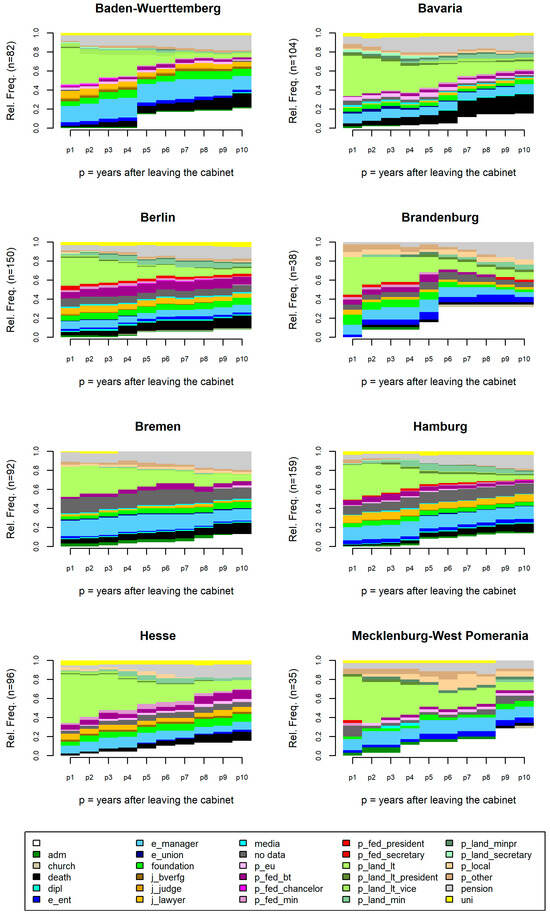

4.7. Differences between the States?

Another potentially interesting variable to categorize the sequence plots is the state. Due to space restrictions, the post-ministerial careers for the 16 German states are not presented here. They can be found in Appendix A (Figure A2 and Figure A3). Nevertheless, a number of different insights can be gained from these pictures. Although these are first and foremost merely empirical observations which have to be checked on their causal underpinning, the significant variations among some of the states are nevertheless striking. Six particularly noteworthy findings will be presented here:

- (1)

- In Baden-Wuerttemberg, many more former ministers work as managers and in the private sector than in the other states.

- (2)

- The chances to use the position in the state cabinet as a stepping stone for a position at the federal level are much lower for ministers in the eastern German states (except for Saxony).

- (3)

- The best chances to make it to the Bundestag lie with ministers from Berlin, North-Rhine-Westphalia, and Rhineland-Palatinate.

- (4)

- Local politics is a likely option particularly for eastern German state ministers.

- (5)

- The number of former cabinet members working in the judicial system, mainly as lawyers, but also as judges (including the Federal Constitutional Court), varies considerably among the states. While in Bavaria, Bremen, and Mecklenburg West-Pomerania virtually no former cabinet member changes into the judicial system, in Thuringia, Saxony, or Hamburg, former ministers on average stay more than half a year of the ten observed years within the judicial system.

- (6)

- The possibilities for former ministers to once again become ministers at a state level are also very unevenly distributed: In Bremen, Mecklenburg West-Pomerania, Saxony, and Schleswig-Holstein, a return to a position within a state executive is very rare, whereas this career pattern makes up a significant proportion in Berlin, Hamburg, and Lower-Saxony.

Overall, this analysis on the state level shows that particularly between eastern and western Germany there remain major differences in the career patterns of former ministers, especially when it comes to the possibility of a further political career at the national level.

4.8. From State to Event Sequences: What Are the Most Frequent Transition Sequences?

Another interesting question deals with the most common career patterns are after leaving the cabinet. To answer this, we can take a look at the ten most frequent sequences (see Figure 8). Only about one fourth of all sequences constitute the ten most frequent ones. The most frequent sequence of all is ten years of work as a manager, followed closely by ten years of uninterrupted work as a member of the state parliament. However, looking at the complete sequences is not that informative. Imagine someone who was a member of the state parliament for five years before dying. This would be counted as a different sequence than someone who was a member of the state parliament for four years and then died, although from a biographical perspective these two post-cabinet careers seem to be very similar.

Figure 8.

Percentages of the ten most frequent sequences.

To gain a better understanding of the sequences of transitions, it makes sense to change the dataset structure from the STS format toward an event sequence format. The duration of the single stages is no longer important in that format. It only holds the ordered sequences of the transitions from one state to another (this is what we call an event sequence). Knowing all the complete event sequences, we can also figure out the most frequent event subsequences (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The 20 most frequent event subsequences.

Interpreting this figure is straightforward: The most frequent event subsequence is the change into the state parliament, followed by a transition to a manager position. About 8 percent of all event sequences include a change from the state parliament to pension. It is interesting that most of the frequent multistage subsequences (those that do not consist of a transition toward a single stage only) start at the state parliament. This is hardly surprising when we consider the wedge-shaped form of the state parliament members in most of the previous transversal frequency figures, which indicate a movement from the state parliament to other positions. Therefore, the most frequent subsequences that consist of more than a single state all start at a position as a member of a state parliament. In other words, when former state ministers sit as members of the state parliament, this often represents a transitional phase for them.

Event subsequences are also very helpful to determine differences between groups. As an example, Figure 10 shows the five most discriminating event subsequences between men and women. The significance values are based on a chi-square test, testing against the null hypothesis of independence with gender. The result confirms our previous findings: female ministers work significantly more often for foundations after leaving the cabinet, while they are less often managers and also pass away less often (within the ten-year timeframe). These results have to be treated with some caution because the large number of multiple-paired comparisons lead to an accumulation of the alpha error, leading to significant results where there is in reality no real difference.13

Figure 10.

The five most discriminating event subsequences between men and women.

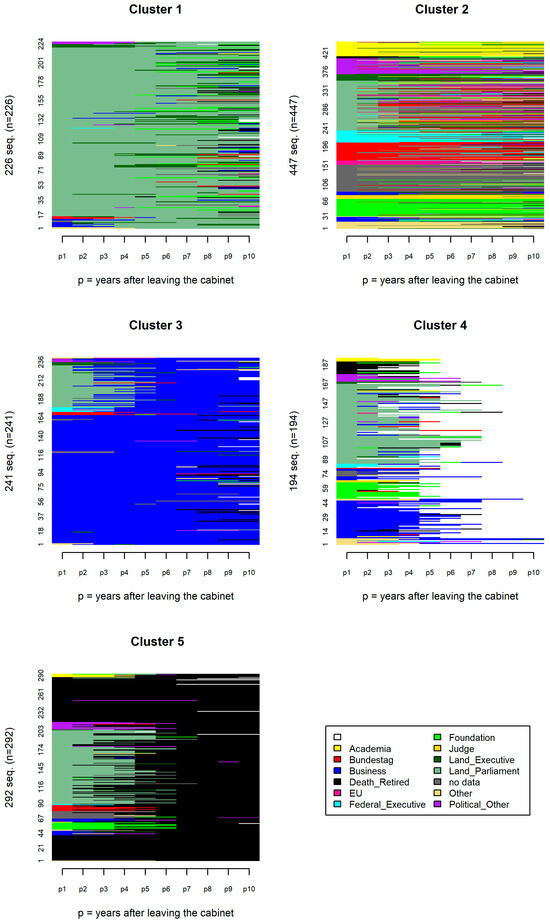

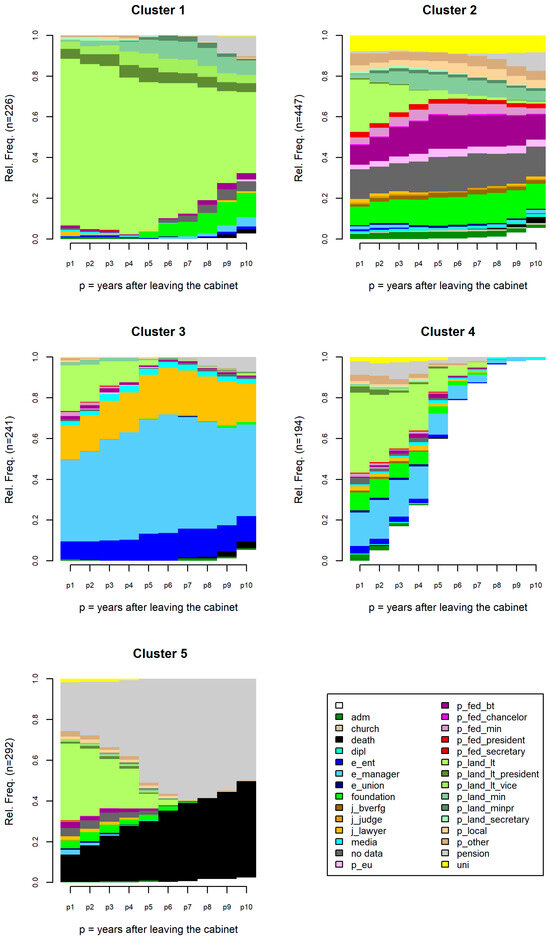

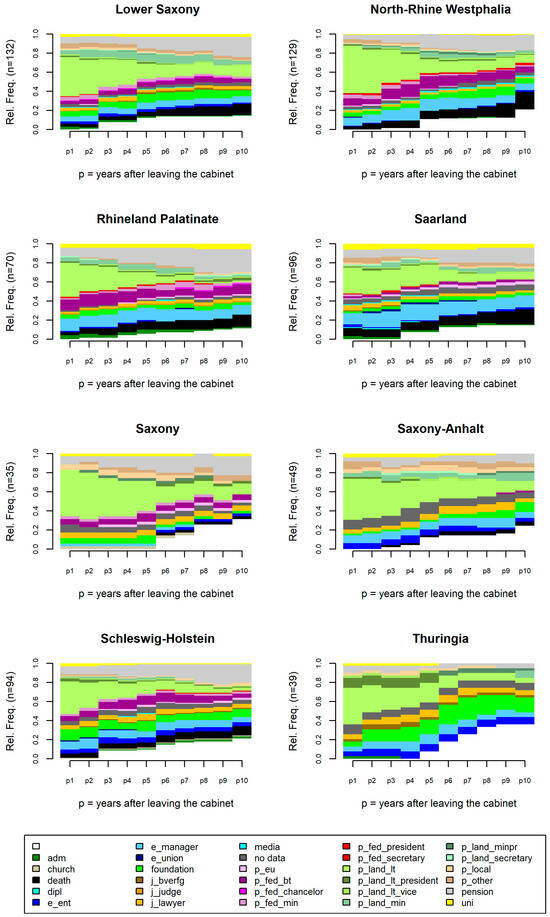

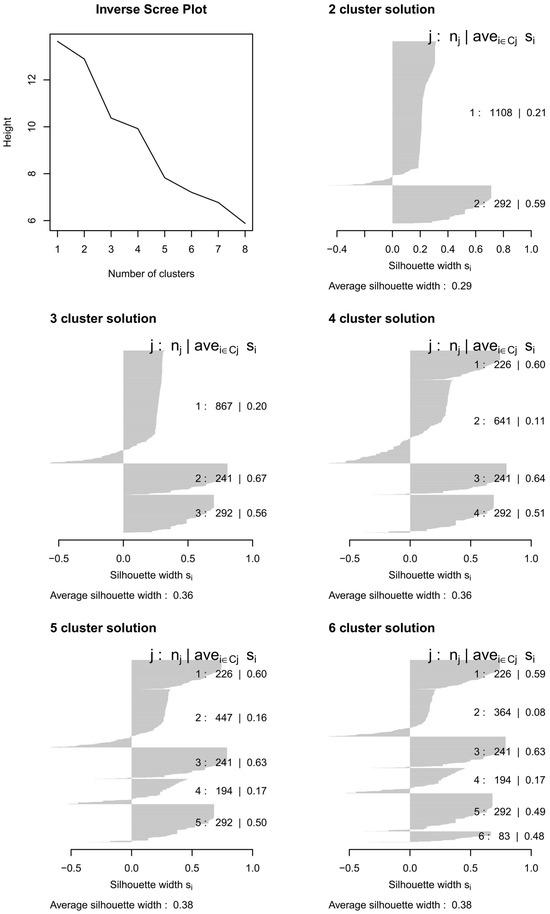

4.9. Five Clusters of Post-Ministerial Careers

Before applying OM and clustering procedures, it is necessary to reduce the full alphabet (28 states) to a more manageable number of states, otherwise the clustering cannot produce any meaningful results. I constructed this reduced alphabet based on the idea that this reduction should allow both a distinction between the distinct levels of the political system and between legislative and executive positions. The reduced alphabet consists of 12 codes for distinct positions and 2 codes for missing data (missing information and end of the observation period). See Table A1 for an overview of how the original codes were pooled to the reduced alphabet.

The inverse scree plot suggests that either a three- or a five-cluster solution is best. With respect to overall average silhouette width, the five-cluster solution is preferable (see Figure A4).14 It results in two clusters (clusters 1 and 3) that can largely be seen as homogenous with average silhouette widths of si ≥ 0.6, one cluster with medium homogeneity (cluster 5, si = 0.5), and two rather heterogenous clusters (clusters 2 and 4, si < 0.2). While the latter two clusters clearly present no single pattern of post-ministerial biographies, the other three clusters can be interpreted in such a way.

Figure 11 presents this five-cluster solution as sequence frequency plots using the reduced alphabet (because this simplifies interpretation here), and Figure 12 shows the transversal frequency plots applying the original 28-state alphabet. Although being far from perfect from a clustering point of view, we see that there are three big groups of post-cabinet careers that are quite homogenous: First, former ministers who move to the state parliament and stay there for at least one more legislative term before they often return to a state cabinet (cluster 1). Second, cluster 3 includes mainly those who either directly or, after a few years in state parliament, move onto the private business sector or work as lawyers. In most cases, these former politicians also stay in private business for a long time (often even for the complete observed 10 years). And thirdly, cluster 5 consists of politicians who retired or died during the 10 years after they left office. Cluster 4, on the other hand, includes those politicians for whom the dataset does not cover the ten years completely because they left office after 2004. Even if the trajectories are thus truncated, the cluster shows that little further change can be seen, especially among those who move into business or foundations. Cluster 2 is not only the biggest cluster (n = 447) but also the least clear one. Nevertheless, it also tells a story: particularly those ministers that start a job within academia or at a foundation after their cabinet position stay in these jobs in many cases for a long period of time. This is partly also true for those switching to a position within the federal executive. Overall, the analysis shows that switching to a higher political position (federal or EU level) is rather an exceptional case for former state ministers. But those who take this step are successful in the sense that in many cases, they remain at the higher political level for the entire ten years of the observation period.

Figure 11.

Regular sequence plots for five-cluster solution (reduced alphabet).

Figure 12.

Transversal frequencies for five-cluster solution (full alphabet).

5. Conclusions and Limitations

While analyses of precabinet as well as preparliamentary positions are common to identify certain (necessary) conditions for becoming a member of parliament/cabinet minister at least since the works of Dogan (1979) and Blondel and Thiébault (1991)—sometimes also employing a sequence analysis perspective (Kerby and Snagovsky 2021; Ohmura et al. 2018; Turner-Zwinkels and Mills 2020)—post-careers have not been analyzed in a similarly systematic manner until now. This is also due to the fact that existing datasets mostly focus on those who govern during the time they are in power, but not afterwards (e.g., Nyrup and Bramwell 2020). While there are some studies on post-parliamentary careers (Claessen et al. 2021; Würfel 2018), post-cabinet careers remain rather under-researched as Claveria and Verge already argued in 2015. Since their seminal international comparison on the career options of former national ministers, not much has changed (but see Dörrenbächer 2016), particularly for the analysis of cabinet members at the subnational level. However, from a political science perspective, this lower level is often of particular interest, because—especially in federal systems such as Germany or Spain—on the one hand, this level has important political competences, so that a purely subnational political career could offer interesting career prospects for many politicians, but on the other hand, these subnational positions could also serve as a springboard for a further career at the national or international level (e.g., EU).

For Germany, the subject of this article, one study focusing on post-cabinet careers of German regional ministers comes from Stolz and Fischer (2014). They showed, for example, that a position within a state cabinet “is the career apex for most ministers”, as movement up the political ladder is rarely seen. Yet, if such an upward step is taken, former state ministers have a clear “preference for the national over the European level and the executive over the legislative mandate” (Stolz and Fischer 2014, p. 157). In such a way, a cabinet position within a German state can indeed serve as a springboard for a high-level political career (Stolz 2003). However, with their focus purely on the very first position after leaving the cabinet—which is a very common approach (e.g., Blondel 1991; Dörrenbächer 2016)—Stolz and Fischer nevertheless miss a relevant part of the picture, i.e., the complete biographic sequence of positions.

This study is a first attempt to map these stages of political careers after leaving the cabinet in a more comprehensive way. By concentrating on a time span of ten years after the ministers have left the cabinet, it gives a picture of the diverse post-cabinet career paths that is rich in detail. Through the use of descriptive sequence analysis and clustering techniques, the full information on the different career stages and their respective durations could be exploited in the analysis. The original dataset compiled for this study covers the entire sample of ministers from all 16 (before 1990: 11) German states from 1945 to 2014. This gives a total of 1400 cases. Coding for each year the most relevant position a politician has occupied after leaving the state cabinet gives a total of 12,805 person years for which data is available. Although this study presents a first and exploratory approach to the question of how careers of former state ministers evolve after leaving the cabinet—pointing out how suitable the method of sequence analysis is for the investigation of such questions—some striking findings could be made:

First, for most of the politicians, being a member of a state government is the highest political position they ever hold and thus a dead end in their political careers. This result can also be interpreted as an indication that the national and the subnational levels are largely separated when it comes to political careers. Empirical evidence shows that only a small minority uses the state cabinet positions as stepping stones for a further career at the federal or even European level. Yet, as a reversed perspective looking at the earlier career steps of Federal Chancellors and important federal ministries (foreign, interior, finance, and economy) shows, a position in a state cabinet is a good starting point for a significant proportion of these federal cabinet members. This is particularly true for chancellors. Of the nine German chancellors, only two did not hold any position in a state cabinet before. However, in Germany it is obviously not the case that national ministers are recruited exclusively through state cabinets; rather, for most national ministries, the federal level (parliament, state secretary posts, and transfers from other departments) is the most important recruitment channel into the federal cabinet.15 This result is in line with earlier studies, which did not apply a sequence analysis perspective (Borchert and Stolz 2011; Stolz 2003). For German politicians, the regional career is thus often a more attractive option compared to the much more complex national political sphere. With respect to the strong competences the German political system gives to the state level, a statement like the one from former Bavarian Prime Minister Franz Josef Strauß, “I have always emphasized that the office of Bavarian Prime Minister is the most beautiful office in the world”, shows more than just local rootedness for electoral campaigning. It also shows a certain truth that can be observed in the empirical data on post-ministerial careers as well. In that regard, the situation in at least some major German states (e.g., North Rhine-Westphalia, Bavaria, or Baden-Wuertemberg) resembles other strongly regionalized states, such as Spain or the UK, where regional ministerial positions in Catalonia and Scotland have sometimes become an even more prestigious political career option than national politics (Stolz 2011).

Secondly, I identified four major alternative career trajectories apart from a move to a higher political level: state politics, private sector/economy, judicial system, and charitable foundations. By far the largest number of state ministers stay in state politics. They remain, at least for some time, in the state parliament, and some even return to the state cabinet. Again, this indicates that the state level provides a distinct political career in its own right, which is a desirable option for the vast majority of former state ministers.

Thirdly, the analyses showed some major variations regarding the post-ministerial careers according to sex (male politicians more often switch to higher political levels or into private business, while former female state ministers work more often in foundations after leaving office); state (in the East German states, former state ministers seldomly make it to the federal level, compared to much higher rates in the West German states); last portfolio (prime ministers, ministers for federal affairs, and heads of the state chancelleries have the best chances to make it to the federal executive, while ministries of economy and transportation, finance, or construction and housing are good starting blocks for a position in the private sector); and decade (the percentage of former ministers who left politics after leaving the cabinet office for a position in private business or as a lawyer steadily rose during the decades). Although some differences exist with respect to party affiliation (e.g., former FDP ministers more often take up a position in private business or as a lawyer after leaving the cabinet), these differences are small compared to the aforementioned variables, particularly when comparing the two major parties, the Christian Democratic CDU and Social Democratic SPD. For all these differences that the descriptive exploration of the empirical sequence data has revealed, further analyses that should focus on the causal mechanisms explaining these variations are needed.

The extent to which these findings for the German subnational level are specific to Germany due to its strong federalism or can also be found in other countries should be investigated in further studies. The sequence analysis approach, which has been specifically detailed in this article also for this reason, can certainly be fruitfully applied to data from other countries.

Nonetheless, this study has several limitations. First, the decision to concentrate on the timespan of 10 years after leaving the cabinet might not be long enough to capture the complete follow-up career of a former state minister. Yet, compared to the nonsequence analysis approach of only focusing on the very first transition, this paper already resembles a major development toward a more complete picture of the post-cabinet careers. A second limitation associated with the definition of the alphabet is the question of how to deal with phases where politicians have two or more relevant jobs or political positions. Neither the standard approach applied in this analysis of coding only one of the positions (Brzinsky-Fay and Kohler 2010, p. 361) nor the alternative of combining parallel positions into a new state (Aassve et al. 2007; Pollock 2007) is fully adequate when applied to the study of elite careers. One option to tackle this problem might be a Multichannel Sequence Analysis as proposed by Gauthier et al. (2010).

Third, the OM procedure, applying the LCS metric with identical transformation costs for all transitions, is clearly a crude and probably oversimplified approach to capturing what “sequence similarity” means in terms of post-ministerial careers. This problem was evident in cluster 4, which contained right-censored cases throughout, i.e., post-ministerial careers for which the full 10 years could not be observed due to the end of the observation period in 2014. To the extent that these right-censored cases were completely excluded from the analysis, one could reduce a fuzzy cluster by doing so, but this would not improve the quality of the other cluster solutions. Moreover, the empirical information contained in this cluster would be completely lost. A better option at this point would be to set the transition costs for the change to “no data available due to end of observation period” higher, so that these incomplete sequences are not sorted into an additional cluster, but are grouped into the other clusters according to the existing states that make more sense in terms of content. This is, however, a general problem of sequence analysis, because the question of how to integrate the temporal component of social sequences—something that is not rooted in the classic biological sequence analysis method—has not been solved yet (Halpin 2010; Lesnard 2014).

Finally, a fourth point should be mentioned that some might deem to be a limitation. Sequence analysis as applied in this study is primarily an exploratory approach. However, in my view, data exploration and structuring techniques, such as sequence analysis, particularly if the data at hand are as complex, complicated, and numerous as in this example, are a necessary requirement for further analytical approaches. As Halpin rightfully noticed, sequence analysis “gives a holistic perspective that can help put the spell-focused hazard rate model, or the period-by-period transition-focused model, into context“ (Halpin 2010, p. 367). In that regard, this study has at least shown the potential of a sequence analysis approach for better understanding the post-ministerial careers of regional ministers, not only for Germany, but also for other federal countries. Accordingly, it would be welcomed if, analogous to the data collection for this article, datasets with post-cabinet careers were created in other countries and evaluated using sequence analysis. Yet, in order to compare the results between countries, probably the most difficult problem will be the development of a uniform alphabet that enables a meaningful comparative interpretation of the states for all countries. The complete as well as the reduced alphabet used in this study may serve as a starting point for such an international comparative sequence analysis of post-cabinet careers.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Replication data and R-code replicating all figures in this article are available at Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/0RCBQK (accessed on 25 September 2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Codebook.

Table A1.

Codebook.

| Reduced Alphabet Code | Original Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Land_Parliament | p_land_lt | Member of a state parliament |

| p_land_lt_president | President of a state parliament | |

| p_land_lt_vice | Vice-president of a state parliament | |

| Bundestag | p_fed_bt | Member of the Bundestag |

| EU | p_eu | EU (Parliament, Commission, Agencies) |

| Land_Executive | p_land_minprä | Prime minister of a state |

| p_land_min | Minister of a state | |

| p_land_secretary | State secretary of a state | |

| Federal_Executive | p_fed_chancellor | Federal Chancellor |

| p_fed_min | Federal minister | |

| p_fed_president | Federal President | |

| p_fed_secretary | State secretary federal level | |

| Political_Other | p_local | Local politics (e.g., mayor, city councilor) |

| p_other | Other political engagement (mostly party business, advising politicians) | |

| Judge | j_bverfg | Judge at the Federal Constitutional Court |

| j_judge | Judge | |

| Economy/private sector | e_ent | Self-employed (e.g., founder of a company, farmer, corporate consultant) |

| e_manager | Manager, Member of a board of directors, Member of an advisory committee | |

| j_lawyer | Lawyer | |

| media | Media | |

| Other | adm | Administration |

| church | Priest, church administration | |

| dipl | Diplomacy (Federal Foreign Office, ambassador) | |

| e_union | Member of employee’s or employer’s associations | |

| Foundation | foundation | Registered association, charitable foundation, voluntary work |

| Academia | uni | University (full) professor, researcher at research institute |

| Death_Retired | death | Death |

| pension | Pension, retired |

Figure A1.

Regular sequence plot of all post-ministerial careers.

Figure A2.

Transversal frequency plots by state (part 1).

Figure A3.

Transversal frequency plots by state (part 2).

Figure A4.

Inverse scree plot and silhouettes.

Notes

| 1 | They ask: “what was your profession immediately after you left the parliament?” (Best et al. 2008, p. 15). See Edinger and Schwarz for a more detailed analysis of the same dataset (Edinger and Schwarz 2009). |

| 2 | For western Germany and Berlin, this means after 1945, for eastern Germany the observation period starts with the first state cabinets after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1990. |

| 3 | The decision to also include incomplete sequences, i.e., data on post-ministerial careers for which less than 10 years are known, is due to the idea of showing that the method of sequence analysis can also deal with such right-truncated data. The alternative of including only those sequences in the analysis for which a complete 10 years (which of course, is also an arbitrary period) could be observed would mean a significant reduction in the dataset to be analyzed and thus an unnecessary loss of information. |

| 4 | While from a political science point of view the coding decision to primarily focus on political positions makes sense, other research questions that are more concerned with the social or economic level of a post-ministerial career could make use of different coding criteria. For example, the question whether a position is unpaid or paid, and if it is paid how much income is generated by it, might be relevant. Yet, also from a data availability point of view, it is often very hard to know whether a position is paid, unpaid, or officially unpaid, but includes high expenses allowances, which are ultimately equivalent to a salary. |

| 5 | I used curricula vitae from official websites of state and federal ministries, state parliaments, Bundestag and the EU parliament, personal homepages of the politicians, party websites, Munzinger Archive, and Wikipedia. Furthermore, especially for the more problematic cases in terms of data availability, I searched online newspapers for articles about the post-ministerial career. Particularly articles with the headlines “whatever happened to…?” or “where are they now?” can be fruitful sources of information for this kind of study. |

| 6 | For such an approach, see Borchert and Stolz (2011). |

| 7 | Either the same costs can be assumed for all transformations or different costs can be assumed, depending on the transition. This can be theoretically justified (e.g., assuming that a transition from a state minister to the federal chancellor’s office is a larger one than a transition as a member of parliament to the Bundestag. Alternatively, costs can be determined using empirical transition data. The more frequently a particular transition occurs in the dataset, the lower the costs would then be set. Different options to tackle the problem of how to set the costs for transitions, especially for social science sequences with their strong sensitivity to time, have been proposed (Elzinga 2003, 2005; Halpin 2010, 2014; Martin and Wiggins 2011). |

| 8 | This example is adapted from Elzinga (2007, p. 14). |

| 9 | Turner-Zwinkels and Mills (2020) propose a fuzzy clustering algorithm for their sequence analysis of preparliamentary careers in the Netherlands. |

| 10 | The category “manager” also includes salaried members of boards of directors and salaried members of advisory boards. |

| 11 | An example is former federal minister of agriculture and consumer protection, Ilse Aigner, who left the federal level at her own request to become the Bavarian minister of economy. Particularly in Bavaria, it does not seem to be completely self-evident which political level is held in the highest esteem. In this regard, the German federal system in some way resembles patterns known from Belgium (Dodeigne 2014). |

| 12 | Particularly in the years after the Second World War, a number of relatively old politicians became ministers who had already been politicians in the Weimar Republic and held no connections to the Nazis. The most famous example is probably Konrad Adenauer, the first Federal Chancellor, who had been mayor of Cologne from 1917 to 1933. |

| 13 | Performing the test with the Bonferroni-correction indeed no longer reports any significant differences. Yet, this correction is extremely conservative, which makes it very likely that also, in reality, significant differences are no longer detected. Thus, I believe the chi-square test to be the better option here. |

| 14 | Silhouette analysis is a method developed by Rousseeuw (1987) to compare different clustering solutions by distinguishing clear-cut clusters from weak ones using the so-called silhouette measure that can be calculated for every single case. If this measure is positive (as close to 1 as possible), the clustering algorithm puts the case into the best-fitting cluster. If the silhouette measure is instead negative, the case then lies on average closer to a neighboring cluster than to the objects within its own cluster. |

| 15 | In this respect, the situation in Germany differs, for example, from that in Spain, which is also federally organized, where the vast majority of national ministers are recruited in local and regional executives (see Rodriguez-Teruel 2011). |

References

- Aassve, Arnstein, Francesco C. Billari, and Raffaella Piccarreta. 2007. Strings of Adulthood: A Sequence Analysis of Young British Women’s Work-Family Trajectories. European Journal of Population 23: 369–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, Andrew. 1983. Sequences of Social Events: Concepts and Methods for the Analysis of Order in Social Processes. Historical Methods 16: 129–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, Andrew. 1984. Event Sequence and Event Duration: Colligation and Measurement. Historical Methods 17: 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, Andrew. 1995. Sequence Analysis: New Methods for Old Ideas. Annual Review of Sociology 21: 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisenbrey, Silke, and Anette E. Fasang. 2010. New Life for Old Ideas: The ‘Second Wave’ of Sequence Analysis Bringing the ‘Course’ Back into the Life Course. Sociological Methods and Research 38: 420–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Anwar Syed. 2003. Karrierewege Und Rekrutierungsmuster Bei Regierungsmitgliedern Auf Bundesebene 1949–2002. Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg. Available online: http://sundoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/diss-online/03/04H114/index.htm (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Barban, Nicola, and Francesco C. Billari. 2012. Classifying Life Course Trajectories: A Comparison of Latent Class and Sequence Analysis. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C 61: 756–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, Heinrich, Michael Edinger, and Lars Vogel. 2008. Deutsche Abgeordnetenbefragung. Ergebnisse Der Befragung Ehemaliger Abgeordneter. Jena: Friedrich Schiller Universität Jerna. [Google Scholar]

- Best, Heinrich, Stefan Jahr, and Lars Vogel. 2011. Karrieremuster Und Karrierekalküle Deutscher Parlamentarier. In Politik Als Beruf. Edited by Michael Edinger and Werner J. Patzelt. Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag, pp. 168–212. [Google Scholar]

- Bienen, Henry, and Nicolas van de Walle. 1991. Of Time and Power. Leadership Duration in the Modern World. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bienen, Henry, and Nicolas van de Walle. 1992. A Proportional Hazard Model of Leadership Duration. Journal of Politics 54: 685–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binderkrantz, Anne Skorkjær, Marie Kaldahl Nielsen, Helene Helboe Pedersen, and Mathias Wessel Tromborg. 2020. Pre-Parliamentary Party Career and Political Representation. West European Politics 43: 1315–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, Philippe, Felix Bühlmann, and Jacques-Antoine Gauthier, eds. 2014. Advances in Sequence Analysis: Theory, Method, Applications. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Blondel, Jean. 1991. The Post-Ministerial Careers. In The Profession of Government Ministers in Western Europe. Edited by Jean Blondel and Jean-Louis Thiebault. Houndmills, Basingstoke and Hampshire: Macmillan, pp. 153–73. [Google Scholar]

- Blondel, Jean, and Jean-Louis Thiébault. 1991. The Profession of Government Minister in Western Europe. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Borchert, Jens, and Klaus Stolz. 2011. German Political Careers: The State Level as an Arena in Its Own Right? Regional & Federal Studies 21: 205–22. [Google Scholar]

- Box-Steffensmeier, Janet M., and Bradford S. Jones. 1997. Time Is of the Essence. Event History Models in Political Science. American Journal of Political Science 41: 1414–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzinsky-Fay, Christian, and Ulrich Kohler. 2010. New Developments in Sequence Analysis. Sociological Methods & Research 38: 359–64. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, Christopher, and Kevin Theakston. 2016. Leaving the House: The Experience of Former Members of Parliament Who Left the House of Commons in 2010. Parliamentary Affairs 69: 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessen, Clint, Stefanie Bailer, and Tomas Turner-Zwinkels. 2021. The Winners of Legislative Mandate: An Analysis of Post-parliamentary Career Positions in Germany and the Netherlands. European Journal of Political Research 60: 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claveria, Sílvia, and Tània Verge. 2015. Post-Ministerial Occupation in Advanced Industrial Democracies: Ambition, Individual Resources and Institutional Opportunity Structures. European Journal of Political Research 54: 819–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, Benjamin. 2015. Social Sequence Analysis: Methods and Applications. Structural Analysis in the Social Sciences. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dodeigne, Jérémy. 2014. (Re-)Assessing Career Patterns in Multi-Level Systems: Insights from Wallonia in Belgium. Regional & Federal Studies 24: 151–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, Mattei. 1979. How to Become a Cabinet Minister in France: Career Pathways, 1870–1978. Comparative Politics 12: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowding, Keith M. 2009. The Selection of Ministers in Europe: Hiring and Firing. Routledge Advances in European Politics. London: Routledge, vol. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Dörrenbächer, Nora. 2016. Patterns of Post-Cabinet Careers: When One Door Closes Another Door Opens? Acta Politica 51: 472–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edinger, Michael, and Bertram Schwarz. 2009. Leben Nach Dem Mandat—Eine Studie Zu Ehemaligen Abgeordneten (Heft 35 Sonderforschungsbereich 580). Jena: Friedrich Schiller Universität Jerna. [Google Scholar]

- Elzinga, Cees H. 2003. Sequence Similarity: A Non-Aligning Technique. Sociological Methods and Research 32: 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Elzinga, Cees H. 2005. Combinatorial Representations of Token Sequences. Journal of Classification 22: 87–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Elzinga, Cees H. 2007. Sequence Analysis: Metric Representations of Categorical Time Series. Amsterdam: Department of Social Science Research Methods, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Lemmon, Maria, and Michelle M. Taylor-Robinson. 2009. Getting to the Top: Career Paths of Women in Latin American Cabinets. Political Research Quarterly 62: 685–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, Jörn, and André Kaiser. 2009a. Hiring and Firing Ministers under Informal Constraints: Germany. In The Selection of Ministers in Europe. Hiring and Firing. Edited by Keith Dowding and Patrick Dumont. London: Routhledge, pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Jörn, and André Kaiser. 2009b. Linkages between Parliamantary and Ministerial Careers in Germany, 1949–2008. The Budestag as Recruitment Pool. German Politics 18: 140–54. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Jörn, and André Kaiser. 2010. Der Bundestag: Sprungbrett Oder Auffangbecken? Ministerkarrieren Zwischen Parlament Und Exekutive. Zeitschrift Für Parlamentsfragen 41: 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Jörn, and André Kaiser. 2011. Wie Gewonnen, so Zerronnen? Selektions- Und Deselektionsmechanismen in Den Karrieren Deutscher Bundesminister. In Politik Als Beruf (Politische Vierteljahresschrift Sonderheft 44). Edited by Michael Edinger and Werner Patzelt. Wiesbaden: VS-Verlag, pp. 192–212. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Jörn, André Kaiser, and Ingo Rohlfing. 2006. The Push and Pull of Ministerial Resignations in Germany, 1969–2005. West European Politics 29: 709–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]