1. Introduction

The cycle of social mobilizations that Ecuador experienced during June 2022 triggered popular discontent in response to the neoliberal policies deployed by the national government (

Ramírez Gallego 2020). These demonstrations arose in a context of tensions over issues such as inequality, access to public services, the latent privatization of strategic sectors, the intensification of extractivism, corruption, and government decisions regarding fuel prices. As a radiated echo of the social outburst of October 2019, the Indigenous Movement—articulated by several organizations that are part of its organizational structure and led by the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE)—developed a series of repertoires of contention possessing a ten-point agenda that brought together various political, social, economic, and ecological demands (

CONAIE 2022). During the eighteen days of mobilization, the configuration of public opinion was disputed in the media scenario. On the one hand, corporate mainstream media coverage generated a media bias to delegitimize the protest by associating it with attacks against democracy and defending the repressive actions deployed by the public forces. In contrast, the journalistic practice of the Indigenous Movement’s media, alternative, and community media aimed at legitimizing the agenda that motivated the mobilizations and made visible the systematic violations of rights orchestrated by the repressive policy of the State.

Within this framework, this article comparatively analyzes the journalistic coverage of the emblematic events of the mobilization deployed by two media, whose editorial line and organizational structure represent opposing interests. Thus, this research analyzes the disputes of meaning and power according to the agenda and media framing of the following media: (1) Ecuavisa, an open signal television channel with national frequency, which is a private media outlet operating in the country since 1967, linked to powerful economic groups, and (2) TV MICC, a community alternative media of the Indigenous Peasant Movement of Cotopaxi on the air since 2004 but with legitimate frequency since 2008, whose television signal has a limited reach to the provinces of Cotopaxi, Tungurahua, Chimborazo, and part of Pichincha (

Toro Bravo et al. 2019). From this comparative perspective, the article contributes to the understanding of how the media select and filter the processes of social mobilization according to the political stance and interests of the media. Hence, this research contributes to the understanding of how the public agenda is selectively framed by the media agenda, and it constitutes an effort to cross journalism studies and social movement studies.

This recent field of knowledge, which crosses social movement studies and communication, has gained importance from the contemporary processes of social mobilization. Some of these investigations have focused on the representation of protests in the mainstream media (

Villagómez-Rodríguez 2020); others have made comparative studies of traditional versus alternative media, as well as their digital social networks (

Medranda-Morales et al. 2023;

Palacios Guevara and Sánchez-Montoya 2022) and, others have analyzed the role of the Indigenous Movement’s media and, finally, other studies have contributed to the analysis of mobilizations from the on-line and off-line integration from contemporary theoretical frameworks such as technopolitics and transmedia mobilization (

Vanegas-Toala 2022).

Following this field of research, the general objective of this article is to analyze the journalistic coverage of the Ecuador national strike 2022, based on a comparison of the agenda of Ecuavisa and TV MICC media, to answer the research question: what are the disputes of meaning and power that are expressed in the journalistic work of the national strike 2022? From this, the specific objectives are derived: to identify the events of the national strike of June 2022 that received journalistic coverage that configured the informative agenda of Ecuavisa and TV MICC, and (2) o comparatively analyze the discursive construction in the media framing of the milestone events of the national strike of June 2022 that received journalistic coverage in the media that are objects of study.

1.1. Communication and Social Movements in Journalistic Coverage

Traditionally, social movement studies have been approached from political science and sociology. From these disciplines, this research has made it possible to understand the counter-hegemonic struggles deployed by civil society, mostly organized by historically marginalized and oppressed groups, through which they struggle against power with the intention of bringing about political, economic, social, and cultural changes (

Melucci 1999;

Touraine 2000). In this framework, the classical theory of social movements argues that their demands prosper depending on the ability to mobilize symbolic and material resources (

McCarthy and Zald 1977), to articulate repertoires of collective action, understood as strategic practices of political pressure, e.g. protests, strikes, mobilizations, in order to achieve their common goals (

Tarrow 1997;

Tilly and Wood 2010). Indeed, the actions of social movements take place within the framework of contentious politics, and one of the factors on which their incidence depends has to do with the structure of political opportunities in reference to the contextual conditions that may or may not allow them to act. From this premise, taking into account the complexity of highly mediatized contemporary societies, it is understandable that the communicational dimension has gained relevance in the structure of political opportunities (

Cammaerts 2012;

Costanza-Chock 2012,

2013).

For this reason, journalistic coverage of social movements and their protest repertoires has become a symbolic scenario of dispute over the legitimization or delegitimization of their actions. In the last thirty years, there has been a proliferation of studies focused on understanding the role of communication in social movements. The first moment focused on understanding the forms of mediatization through the representation of these movements in the mass media (

Rovira 2013). The second moment, especially with the development of the Internet, turned its attention to the processes of mediation from the appropriation of digital media technologies in the framework of their dynamics of collective action and identity and the structure of political opportunities (

Cammaerts et al. 2013;

Castells 2012;

Reguillo 2017;

Rovira 2017,

2019;

Toret 2015;

Treré 2019). As is evident, this theoretical and conceptual scaffolding has allowed the consolidation of this emerging field of knowledge that vindicates the agency of social movements as political-communicational subjects, which dispute their legitimacy before public opinion (

Saavedra Utman 2020).

One of the most popular approaches in communication and social movements studies has focused on the media agenda and framing. According to

Rovira (

2013,

2017), mainstream media coverage has confined social movements to invisibilization, misrepresentation, disqualification, and even criminalization of their repertoires of contention. Agenda-setting in its “first level” refers to the relative prominence of the issues that are mediatized. In a “second level”, it refers to the framing attributes of the mediatized issues as defined by

McCombs (

2005). A more recent contribution, “New directions in agenda-setting theory and research” (

McCombs et al. 2014), highlights the importance of understanding how the media influences public attention towards certain topics and how this influence has diversified and deepened in the contemporary era, in which different media platforms and technologies converge. Although there is a consensus that agenda theory and framing theory are complementary,

Weaver (

2007), in their article for the

Journal of Communication special issue, emphasize that both are autonomous. In a similar line,

Ardèvol-Abreu (

2015) points out that while the effects of the agenda are given by media repetition and accessibility and exposure, that is, the more the topic is repeated, it will have greater prominence; framing refers to the way in which the topic is described with the ability to generate an interpretive scheme anchored to culture and social discourse.

In this regard, the classic study “The Whole World Is Watching” (

Gitlin 2003) noted that the protests of the student movement and against the Vietnam War were intensely mediatized and that television coverage had a significant impact on public opinion and perception of the events, which influenced political decision making and the direction of the movement itself. The author explores how media coverage transformed activism and politics and analyzes how this interaction between media and protest shaped citizen participation and the public sphere in American society. Indeed, Gitlin suggests that media coverage often focuses on violence and chaos, which could distort the real picture of the protests and affect public opinion about the movement. In the field of setting-framing, he concluded that media coverage emphasized certain issues while skimping on others: the former framing resorted to trivialization, polarization, and marginalization by representing the protesters in a negative manner.

The recent cycle of protests in Ecuador, for example, has stimulated several investigations on the mediatization of the mobilizations. Indeed, several studies agree that mainstream media coverage of the indigenous movement in the protests was characterized by racist stereotypes and negative framing. These representations by setting-framing were dictated by the invisibilization and criminalization of the protesters (

Santi 2020;

Iza Salazar et al. 2020). To understand this social communication phenomenon, it is still necessary to explore more about the media coverage of protests, especially considering that the digital media ecosystem has allowed multiple social movements to self-manage their own communication systems through the appropriation of digital technology. Indeed, this topic still needs to be investigated, especially from a comparative perspective between an indigenous movement’s own media and mainstream corporate media, that allows contrasting the setting-framing of the same social mobilization event.

1.2. Social Movements and Communication Sovereignty

From the alternative communication paradigm—which includes what the Latin American School of Communication called popular, community, and citizen communication—social movements and organizations have played a fundamental role in the creation of their own communication systems through their own alternative or community media (

Barranquero 2019). In this way, it is understandable that they have contributed to the democratization of communication, considering the high media concentration of corporate groups associated with economic, political, and cultural power. In this context, the concept of communicational sovereignty becomes relevant. Communication sovereignty refers to the autonomous control that social groups have over the media they use to disseminate their messages, values, and struggles. It implies the capacity to define their own narratives, as opposed to the influence of large media conglomerates or political and economic interests. This concept promotes informational diversity, plurality of voices, and the democratization of communication, allowing communities to play an active role in the construction of their own representations and the promotion of social change.

The accelerated process of development of information and communication technologies (ICT) had a positive impact on the gestation of social movements’ own media and their communicational sovereignty. The foundational work of

Manuel Castells (

2012) contributed to the notion of mass self-communication, which refers to the capacity of social movements to appropriate digital technologies to create their own communication systems. This has allowed social movements to overcome the barriers of access to corporate media, empowering them as political and communicational subjects that disseminate their messages autonomously. Through digital platforms, social networks, and alternative online media, movements can communicate their ideals, organize, and mobilize followers in real-time, expanding their impact and consolidating their control over the narrative of their struggles. In this sense, ICTs have revolutionized the dynamics of communication in activism, giving social movements significant power in the public sphere. In a similar vein,

Magallanes-Blanco and Treré (

2020) note that the digital appropriation of social movements has made it possible to question highly concentrated media ecologies, create counter-hegemonic spaces, and build bridges between movements.

In the case of Ecuador, being a pluricultural country with 15 indigenous nationalities, this is one of the popular sectors that has the most developed alternative and community media. The indigenous movement in Ecuador has forged a rich history of its own alternative and community media, as well as communication practices aimed at self-representation based on communication sovereignty. For decades, the indigenous movement has established community media, mainly in rural areas, through which they have developed important processes of cultural identity and organizational strengthening. With the advent of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT), these initiatives have become even more relevant and empowered, allowing indigenous communities to connect locally, nationally, regionally, and globally. In contexts of social mobilization, especially in October 2019 and June 2022, these digital practices have made it possible to break the corporate media fence, amplifying their ability to disseminate their own protest narrative, generating a positioning in favor of the claims and enhancing their ability to influence public opinion (

Lupien 2020), as a political opportunity.

Community and alternative media, many of them emerging from the indigenous movement in the contexts of social mobilization, have generated processes of communicational sovereignty and democratization of communication, playing a fundamental role in providing an authentic and local perspective of events, counteracting the dominant narrative of traditional corporate media. Digital appropriation, in turn, has allowed these voices to reach a much wider and diverse audience through social media and online platforms. This has challenged the conventional media narrative by presenting multiple facets of the protests, highlighting the voices and perspectives of indigenous communities in an unprecedented way. Taken together, these elements have enriched news coverage by offering a more complete and equitable view of the protests, thus fostering a more informed public debate and a deeper understanding of the challenges and demands of the indigenous movement.

2. Materials and Methods

This research is based on a mixed perspective that involves a quantitative and qualitative scope in dialogue. First, a study of agenda-setting was carried out to quantify the thematic recurrence of the events of the protest that received media coverage both in Ecuavisa and TV MICC. Secondly, a study of the treatment of these topics was carried out based on a framing analysis, for which Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) was used, which is a type of research that, through a careful analysis of discourse, seeks to determine “the way in which the abuse of power and social inequality are represented, reproduced, legitimized and resisted in text and speech in social and political contexts” (

Van-Dijk 2015, p. 204). Considering that framing presents schemes of interpretation from the CDA, an analysis was established based on the discursive forms of representation of government and protest, following the notion of values and anti-values in the polarized logic (us versus them) proposed by the discursive schemes. From this qualitative approach, it was possible to outline the main thematic axes and the main actors on which the journalistic discourse offered framing elements contributing to the construction of meanings from the journalistic practice.

The construction of the corpus compiled all the journalistic notes made by Ecuavisa’s star newscast and by TV MICC’s Facebook page from June 13 to 30. In total, 215 notes were obtained from Ecuavisa, and from TV MICC, a total of 436 notes (231 made directly by its journalists and a total of 205 reposts from different allied actors). In the first phase, for the analysis of the agenda-setting, a thematic analysis was made from the main news articles broadcasted by Ecuavisa and TV MICC to illustrate how the same event received different news coverage, including it in their news agenda or excluding it. In a second phase, on the main topics that received journalistic coverage in Ecuavisa and TV MICC, a framing analysis was carried out considering the CDA to illustrate the way in which they described the protest actions and the actors in favor and against them. Finally, in the third phase, a comparative analysis was conducted between the journalistic coverage of both media.

In the third phase, to carry out a comparative analysis of the journalistic agendas of Ecuavisa and TV MICC, a timeline was made in which the most important news published by each media outlet concerning the 18 days of the National Strike could be observed. To achieve this analysis, the timeline was divided into three stages of the protest: demonstration phase, escalation phase, and de-escalation and agreement phase. In addition, the most relevant news of each day was selected. The number of important news items shown in the timeline varies between two to four per day. The demonstration phase, which marks the beginning of the protests, covers a period of six days, where the news items published from 13 June to 18 June can be observed. The escalation phase, which is characterized as the most conflictive stage of a social protest, covers a period of six days from 19 June to 24 June 2022. The escalation and agreement phase is where the social conflict finds a solution through dialogue. In this phase, we can observe the dialogues between the Government and the Indigenous Movement. As in the previous phases, it is composed of six days and the period from 25 June to 30 June, which marks the end of the protests with the signing of agreements.

3. Results

Media coverage of the national strike of June 2022 disputed meanings that respond to the political, economic, social, and cultural interests of social sectors. Ecuavisa evidenced a position in rejection of the mobilizations, negatively characterizing the protests by reporting economic and social damages. Similarly, it delegitimized the mobilizations through its coverage of the peace marches and joined the campaign promoted by Quito’s elites seeking peace. Meanwhile, TV MICC sought to vindicate their struggle through extensive coverage of their mobilizations in which the strength and mobilization capacity of the Indigenous Movement was shown. At the same time, it denounced the repression of the public forces and the violations perpetrated by the Government against the rights of the demonstrators. Likewise, TV MICC was a source of contrast in the face of the dissemination of false information regarding the end of the protests.

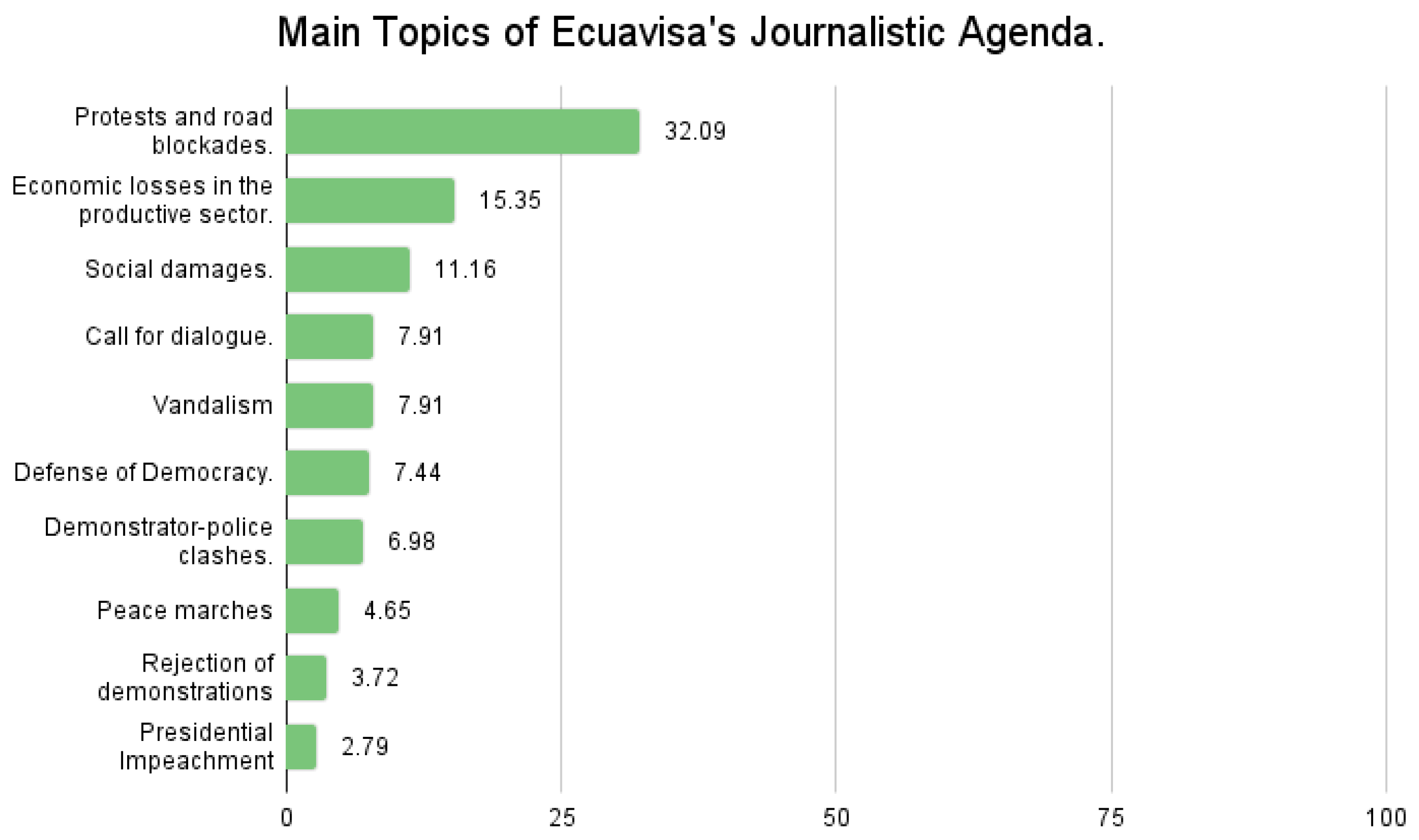

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 below systematize, in general terms, the main notes that made up the news agenda of both media.

The following is a detailed analysis of the comparative thematization of both media according to the different phases of the mobilization: base and demonstration, escalation and de-escalation, and agreement.

In the first phases of the base mobilization and demonstration, from 13 June to 18 June 2022, the disputes of legitimization of the protest are evident through the media coverage both in its thematization (agenda-setting) and in its framing. Ecuavisa’s journalistic agenda in the Televistazo program was focused on four thematic axes: (1) government willingness to dialogue; (2) protests and demonstrations described as acts of vandalism; (3) economic losses in the productive sector; and (4) rejection of the strike by several unions and sectors. On the other hand, TV MICC deployed a thematic coverage focused on four points: (1) detention of Leonidas Iza, president of CONAIE; (2) vindication of the strike agenda; (3) repression by the public forces and injuries; and (4) advance of the mobilization towards Quito. In this context, an agenda-setting framed by the ideological position of each of the media is notorious, which, effectively, echoes in the framing. This is shown in

Figure 3.

Regarding the agenda-setting and framing, Ecuavisa delegitimized the protests through two strategies. First, it denounced acts of vandalism on roads and public buildings in headlines such as “Indians protest with sticks and bladed weapons in Ibarra” (

Ecuavisa 2022a, 34m37s); economic losses in the oil, tourism, and floriculture sectors; military injured and detained by protesters. Secondly, it justifies the state of exception and the actions of the public forces in the containment of the protests through the emphasis that the Government is willing to dialogue; finally, it generated the idea that the Indigenous Movement does not have support. The latter is evident in the following headlines: “The Federación Nacional de Organizaciones Campesinas (FENOC) declared itself against the mobilization called by CONAIE (

Ecuavisa 2022b, 31m10s). In contrast, TV MICC legitimized the protests; hence, it emphasized the explanation of the ten points of the strike’s agenda. On the other hand, it rejected the criminalization of the protest after the arrest of Leonidas Iza with strong journalistic coverage of this event, which it described as “illegal and arbitrary” (

Conaie Ecuador reposted in TV MICC 2022f) through the spokesperson of CONAIE’s lawyer, Lenin Sarsoza. Addsitionally, he denounced the disproportionate use of public force in headlines such as “They shoot at the CONAIE vehicle. We alert this in the framework of the state of exception and the belligerent attitude of the Government against social protest.” (

Conaie Ecuador reposted in TV MICC 2022g) and “We denounce this attack at the Central University, they shoot a community member who was eating and people in a truck outside the University” (

Conaie Ecuador reposted in TV MICC 2022h).

In the escalation phase of the national strike, between 19 June and 24 June 2022, the thematic axes disputed the acceptance or rejection of the mobilization. Ecuavisa highlighted news related to the “defense of democracy” and the “defense of peace”. Through its agenda, it mainly presents news that try to demonstrate the support of the Armed Forces to the Government, framing the protest as a “coup” action, and complements through notes focused on making visible the so-called “marches for peace”, organized by the social and the socioeconomic elites, although they were considerably smaller in proportion to the popular demonstration. On the other hand, TV MICC generated coverage of denunciation in 25 articles on the multiple violations of rights by the security forces: raids by the security forces on the Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana (CCE) of FENOCIN, as well as harassment at the headquarters of CONAIE; death of demonstrators victims of repression, namely, Byron Guatatoca, who died injured by a tear gas bomb inserted in his skull that entered through his cavity “CONFENIAE denounces that a indigenous was murdered in Puyo. Reported killed by security forces during repression in Pastaza province ” (

TV MICC 2022a), and Henry Quezada, who was killed by the police force according to a CONAIE “Justice for Henry Quezada Espinoza. Brother from Quito, a graduate of Patrón Mejía, fatal victim of brutal repression and state violence” (

Conaie Ecuador reposted in TV MICC 2022i) and, finally, they denounce the use of firearms by the state defense apparatus. In a second order, TV MICC focused on demonstrating the support of citizens for the national strike. Therefore, they deployed coverage such as the reception of demonstrators in Quito in the universities, which opened their doors as humanitarian support centers, as well as the donations of food made by citizensFinally, it deployed coverage of several support marches organized by women’s collectives, which adopted the slogan “They can not ask us for peace if they keep killing us” in response to the dispute over the meaning of peace (

La Voz de la Confeniae reposted by TV MICC 2022a). Both agendas can be seen in

Figure 4.

During the de-escalation and agreement phase of the mobilization, between 25 June and 30 June 2022, Ecuavisa’s journalistic agenda continued delegitimizing the protests. Therefore, the most important topics on the agenda were social and economic damages and the report of injuries and deaths among the security forces. Ecuavisa also reported on the dialogues held with the indigenous sector. In the case of social impacts, it was evidenced in the news that reported on fuel shortages and lack of oxygen for hospitals. Meanwhile, in the economic sector, a loss of “900 million dollars” was reported (

Ecuavisa 2022c, 18m13s). Likewise, it was reported the death of one soldier and twelve wounded soldiers (

Ecuavisa 2022d, 06m04s) after a confrontation with Amazonian community members. On the other hand, TV MICC filled its agenda with information on the different mobilizations called to demand a response from the Government. It also denounced the censorship of the community media Apak TV “ApakTv, a Kichwa audiovisual production company and community media of the Otavalo people, Facebook page closed” (

Conaie Ecuador reposted in TV MICC 2022b), and the hack of social media accounts of the indigenous and former communication leader Apawki Castro; it also deployed a coverage on the strong police repression, for example: “Violent entry of the National Police into the San Miguel del Común community” (

Conaie Ecuador reposted in TV MICC 2022c). Another important activity of TV MICC was to refute false information circulating in social networks, especially regarding the speculation of the end of the strike. Finally, like Ecuavisa, it reported on the different dialogues with the Government, as well as the popular support for the demonstrations after their end. The journalistic agendas can be seen in

Figure 5.

4. Discussion

The media framing of Ecuavisa was focused on negatively characterizing the demonstrations of the Indigenous Movement. For this purpose, it used derogatory adjectives such as “violent”, “vandals”, “terrorists”, “irrational”, “unproductive”, and “antidemocratic”, for example, “Fiscalía initiates investigation for the crime of terrorism” (

Ecuavisa 2022e, 20m00s) and “Patricio Viera was assaulted with sticks and punches by protesters ” (

Ecuavisa 2022f, 04m55s). Above all, in the context in which the National Assembly debated on the recall of the President of the Republic, there were many frames that blamed the UNES bench—a party led by former President Rafael Correa—for an attempted coup d’état linked to the mobilizations. These characterizations came, to a great extent, from the journalistic sources favored by the media: ministers from different State portfolios, specialists in economic and legal matters, businessmen, and military and police commanders. In addition, they took a position in favor of the “peace marches”, which they characterized with adjectives such as “rational”, “peaceful”, and “productive” which contributed to the construction of a sense that citizenship and democracy are built through dialogue, for example, in headlines such as “Workers and businessmen march for peace” (

Ecuavisa 2022g, 37m00s), “Citizens demand peace” (

Ecuavisa 2022h, 35m20s). Hence, the main sources in this line were the representatives of the productive sector and even the Catholic Church, in which they highlighted the position of Pope Francis: “Pope asks to abandon extreme positions” (

Ecuavisa 2022i, 1m30s). These examples demonstrate the ideological position that Ecuavisa maintained during the protests.

Ecuavisa’s news coverage generated a frame that contributed to the criminalization of the protests, as can be seen in

Figure 6. A total of 20% of the journalistic notes contribute to this negative sense that counteracts the right to protest; for this reason, Ecuavisa broadcasted different news in which it seeks to justify the actions of the public forces. A framing was established to demonstrate that the Government was supported by the Armed Forces. For example, “Armed Forces support the democratic regime” (

Ecuavisa 2022j, 09m15s). Likewise, after the confrontations between the security forces and the demonstrators, Ecuavisa showed the security forces as victims of the violence in the protests. At the same time, the Government authorized the progressive use of force, as announced by President Guillermo Lasso: “The National Police and the Armed Forces will act with the necessary means to defend; within the legal framework, through the progressive use of force, public order and democracy” (

Ecuavisa 2022k, 07m28s). In this way, Ecuavisa showed the Government as an entity strengthened by the support of the Armed Forces.

On the other hand, the journalistic framing of TV MICC characterized the demonstrations as legitimate expressions of the popular will. Hence, they linked the mobilization to the meaning of the “right to protest”, enshrined in the Constitution of the Republic (2008). In this line, as a strategy of legitimization, their journalistic framing was centered on showing the strength of the mobilizations that they characterized as “massive” to make visible the convening power of the Indigenous Movement to its bases, as well as other social movements that joined the strike. To legitimize the demonstrations, TV MICC recurrently used the phrases “historic struggle”, “great concentration”, “we continue in struggle”, and “long live the social struggle”. For example, the publication “Large march in Quito (…) For dignity and results ” (

TV MICC 2022b) can be evidenced by the framing to make visible the mobilization capacity of the Indigenous Movement and the popular support accompanied with hashtags such as #DignidadComunitariaPopular and #TodosSomosPueblo.

As a strategy to make the mobilization visible, TV MICC focused on denouncing the repression and disputing the media space to contrast the prevailing media agenda deployed by the corporate media. Its journalistic framing rejected the government’s actions against the mobilization through expressions such as “repressive government”, “warmongering policy”, “excessive use of force”, and “extreme repression”, which were condensed in the hashtag #ParenLaMasacre. For example, during the arrest of Leonidas Iza, several publications were deployed in which they held the government responsible for Iza’s integrity. Therefore, they compared the actions of the Government of Guillermo Lasso to those of a dictatorship: “As in the worst dictatorships Guillermo Lasso orders to militarize the Unit of Flagrancy Attorney General’s Office of Ecuador in Quito” (

Conaie Ecuador reposted in TV MICC 2022d). At the same time, they linked the government’s position to an “extreme right” position characterized by “authoritarianism” and, above all, they denounced the absence of the President of the Republic, Guillermo Laso, at the dialogue tables, positing the idea of an “absent government”, for example, in the following note: “The government breaks the dialogue confirming its authoritarianism, lack of will and incapacity. We hold Guillermo Lasso responsible for the consequences of his warmongering policy. We demand respect for our maximum leader” (

Conaie Ecuador reposted in TV MICC 2022e) the president’s inability to face a dialogue with the Indigenous Movement can be evidenced.

Within this media coverage, TV MICC also played an important role as a communication channel between the grassroots and the indigenous leadership since, through press conferences or statements, indigenous leaders made known the decisions taken concerning the mobilizations and the progress achieved as a result of the dialogues with the Government, in other words, TV MICC as a communication channel helped to make transparent and accountable day by day with all the participants of the protests. Regarding the sources of information, TV MICC has a great variety of actors the most important source lies in Leonidas Iza, president of CONAIE; Andrés Ayala, leader of the Indigenous Movement of Cotopaxi; Nayra Chalan, then vice president of ECUARUNARI; Zenaida Yasacama, vice president of CONAIE; among other representatives of different social sectors such as transportation unions, university students, women’s groups and the Human Rights Mission of Argentina. Another important factor for TV MICC was the network established between the different community media and official networks of the different organizations belonging to the Indigenous Movement. In this line, TV MICC replicated the coverage of other community and alternative media, such as Apak TV, Así No Más, La voz de la CONFENAIE, ACAPANA, Radio Inti Pacha, Ayllupak Kawsay TV, and Kapari Comunicación. Thus, 53% of the information disseminated by TV MICC corresponds to coverage deployed by its team, while 21% of the information shared through its Facebook page echoes the information of the official Facebook page of CONAIE. The remaining 26% are distributed on official pages of different organizations such as COMICH Comunicación, FECOS Salcedo, Confederación del Pueblo Kayambi, FECAB BRUNARI, MICC, and Pueblo Kichwa Karanki.

Figure 7 shows a summary of the framing of TV MICC during the coverage of the national strike in 2022.

One of the discursive axes that stands out in TV MICC was the rejection of racist hatred, since during the course of the demonstrations, various acts of racism could be observed by the sector opposing the Indigenous Movement. For example, on 16 June, TV MICC, through a video, described the following “Denouncement of violation of rights of an indigenous colleague, Ana Ushco, who suffered a physical and verbal aggression in a food store in the city of Latacunga” (

TV MICC 2022c). Another racist event occurred in Quito, in the parish of Tumbaco. This fact was shared by TV MICC from the official account of Radio Pichincha: “Residents of Tumbaco report gunshots at the height of Ruta Viva, in one of the closures for the #ParoNacional. The video shows two cars shooting at civilians and trying to run them over” (

Radio Pichincha reposted by TV MICC 2022). Addressing with this situation, the Indigenous Movement issued a message in which it rejected racist discrimination and claimed its citizenship with equal rights, alluding to the folklore ways in which the construction of an intercultural society is misunderstood. In this framework, TV MICC replied to Urpichakunaq Rimaynin’s statements with a strong message in this direction: “They like our dances, our weavings, but they do not like that we talk to them as equals” (

Cedin Indígena reposted by TV MICC 2022) On the other hand, TV MICC denounced another act of racism perpetrated against the indigenous leader Alex Toapanta in which it stated the following: “We reject the racist and hateful attack perpetrated against our comrade Alex Toapanta” (

TV MICC 2022d). These examples highlight the problems faced by the indigenous people in the context of the June 2022 mobilizations.

Regarding the media disputes over the legitimization of the mobilizations between TV MICC and Ecuavisa, they focused on two important aspects. The first covers the denunciations of repression by the public forces as opposed to the justification of the actions of the State’s defense apparatus. That is to say, TV MICC’s dispute focused on denouncing all the outrages caused by the public force through the publication of such acts; for example, the publication “Tweet to support for the National Strike in Ecuador. 8 days of social protest, but Lasso’s government prefers repression rather than a response” (

Conaie Ecuador reposted in TV MICC 2022a), generated on 20 June, sought to generate support for the mobilizations in the face of the Government’s inoperability. On the other hand, Ecuavisa justified the actions of the public forces through the news that narrated vandalism, as well as the confrontations between demonstrators and the military and police. For example, the prime-time news program Televistazo reported 63 policemen and 19 military personnel injured; 22 patrol cars damaged and 23 officers detained (

Ecuavisa 2022l, 12m30s).

The second aspect is related to the construction of a discourse of defense of democracy by Ecuavisa. For example, a news report included the declarations of President Laso: “The real intention of Mr. Iza is to overthrow the government. This makes it clear that he never wanted to resolve an agenda for the benefit of the indigenous peoples and nationalities (...) groups of hooligans have infiltrated the country seeking to destabilize democracy by sowing terror” (

Ecuavisa 2022m, 06m00s). In this way, the government created the imaginary that the mobilization was an attempt at a coup d’état and justified the actions of the public forces. In contrast, TV MICC sought to make visible the demands of the Indigenous Movement, especially focused on the ten points of the mobilization agenda. However, the Indigenous Movement foresaw the exit of the president as an indirect consequence of the mobilizations, as evidenced in the statements of Nayra Chalán, who said: “If the government falls, it will be of its own weight” (

TV MICC 2022e).

Finally, during the final days of the mobilizations, false information related to the demonstrations was disseminated; in response, TV MICC was constantly clarifying rumors about the end of the strike. For example, the publication “False information is circulating and the campaign to discredit the legitimate social struggle is intensifying. We ask to be informed through official channels.” (

TV MICC 2022f) disproved the information generated in various traditional media and, at the same time, constituted one of the most important disputes to break the media bias established by the large corporate media. In this context, community and alternative media, as well as the official accounts of indigenous organizations, used the hashtag #ElParoNoPara to consolidate a message that disproves false information. All these exemplifications have evidenced the disputes of meaning during the June 2022 strike between the Indigenous Movement and the Government. At the media level, TV MICC represented the Indigenous Movement, a communicative platform that allowed counteracting the representation imposed by the corporate media. At the same time, this process of demonstrations showed the importance and consolidation of community media in the process of self-representation that began in the protests of October 2019.

5. Conclusions

Through the comparative analysis of the media coverage of the national strike between a corporate media Ecuavisa and an indigenous community media TV MICC, the dispute of meanings and power by the journalistic framing during the eighteen days of protests in June 2022 in Ecuador was evidenced. Ecuavisa’s journalistic agenda-setting and framing focused on delegitimizing the social mobilization by giving prominence to issues related to economic losses in the productive-business sector and describing the strikes as acts of vandalism, justifying the actions of the security forces in defense of democracy. On the contrary, the journalistic agenda-setting and framing of TV MICCl legitimized the ten points of the protest agenda of the strike and focused its coverage on the denunciation of repression, the statements of indigenous leaders, and the dialogues carried out with the Government. Likewise, Ecuavisa framed its journalistic coverage to delegitimize all the phases of the mobilization (base, demonstration, escalation, de-escalation, and agreement) and gave prominence to information related to economic losses in the productive sector. In contrast, TV MICC focused on ratifying the broad popular support of the demonstrations through the different reports broadcasted on its Facebook page.

Ecuavisa’s journalistic framing of the June protests lies in the right-wing ideological stance that characterizes this media, being a common factor between Ecuavisa and the Government of Guillermo Lasso, which is also linked to the country’s banking sector. In addition, the close relationship between the Government and the business and productive sectors of the country gave Ecuavisa a guideline to focus its coverage on reporting the economic losses of these sectors due to the demonstrations. This form of delegitimization was one of the most used by Ecuavisa’s journalistic agenda. TV MICC contributed to the democratization of communication through its journalistic coverage by providing ample space to make visible and vindicate the demands made by the Indigenous Movement. Historically, the corporate media have denied a space for the freedom of expression of the indigenous people, where they are also represented stereotypically, relegating them to subjects that should provide food to the city. This can be reflected in the continuous informative notes that Ecuavisa published about the food shortages in supermarkets, but at no time did it report on the problems and difficulties that indigenous people have to go through to produce different foods since, unlike Ecuavisa, TV MICC gave space for the expression of several protesters who demanded fair prices for products used in the field as an act of communicational sovereignty.

In the June 2022 protests, community media consolidated the process of self-representation in an exercise of communicational sovereignty that began in the October 2019 strike. Where the performance of alternative media and community media gave a possibility for the indigenous sector to demand their claims from their worldview and, at the same time, break with the media bias established by the corporate media, who have historically criminalized and delegitimized social demonstrations. For this reason, in the dialogues between the Government and the different indigenous organizations, the community media were the main channel for broadcasting and informing without the biases of the corporate media. In addition, during this cycle of protests, community media such as TV MICC were supported to dispute a media war with the mainstream media, especially when the corporate media disseminated false information about the demonstrations to distort and weaken the demonstrations. These protests of June 2022 consolidate community and alternative media as social actors that act in the progressive line of vindication of rights, unlike corporate media linked to economic, political, social, and cultural power. Hence, this research contributes to an emerging field of knowledge that understands communication as the neuralgic axis of the articulation of the communicational sovereignty of social movements. This article evidences the importance of generating comparative studies of the agenda, which allows us to demonstrate the political economy of communication crossed by political and economic interests in the way in which protests are covered. Since Latin America has recently experienced a new cycle of protests, studies of journalistic coverage of mobilizations allow a deep understanding of the way in which the dominant media and alternative and community media frame protests in order to legitimize or delegitimize them.