1. Introduction

Accentuated population aging is a global demographic phenomenon of the 21st century that occurs prominently in the Western context. Portugal stands out among European countries in terms of the prevalence of the older population. In the last decade alone, the median age of Portuguese people increased by 4.7 years, while the European median increased by only 2.5 years (

Eurostat 2022). Furthermore, it is estimated that the aging rate will continue to increase between 2040 and 2050 (

Eurostat 2023). These demographic changes require greater attention to aspects that contribute to healthier, more integrated, and a better quality of life in aging. In this sense, several personal, relational, social and even cultural aspects are crucial for the well-being of the aging population with sexual identity being one of the personal phenomena that most influence the successful aging of older gay and bisexual people, relating to constructs such as experiences of loneliness, (dis)satisfaction with life and participation in the community (

Fredriksen-Goldsen 2011;

Mann et al. 2019;

Ribeiro-Gonçalves et al. 2023b).

Sexual identity refers to the way people self-perceive and self-identify according to aspects of their sexuality (

Bishop et al. 2020). The development of sexual identity is a dynamic and co-constructed process that continues throughout the life cycle, being one of the most important processes in the construction of identity in humans (

Hall et al. 2021;

Mitchell et al. 2021). In addition, previous research confirms that identification with minority sexual identities—e.g., people who identify as gay or bisexual—significantly increases the occurrence of several risk factors, such as social isolation, low health indicators, the less rich construction of support networks or the reduction in health-promoting behaviors (

Hill 2006;

Park et al. 2016;

Ribeiro-Gonçalves et al. 2023a). These experiences become even more relevant in older populations, who are potentially more vulnerable and stigmatized (

Fredriksen-Goldsen 2011).

Research in recent decades has identified a series of psychosocial milestones that guide the development of sexual identity, among which questioning one’s sexual orientation, first attraction to same-sex people, self-identification, first same-sex sexual behavior, first disclosure of sexual identity to others (friends, family), and first same-sex romantic relationship (

Bishop et al. 2020;

Hall et al. 2021;

Savin-Williams and Cohen 2015). However, it has also been verified that the way in which these and other milestones occur and are experienced vary intensely depending on the interference of historical, social, and cultural contextual factors at different moments of life cycle in which people are (

Frost et al. 2020;

Hall et al. 2021;

Mann et al. 2019). In addition to the intrapersonal and relational experiences, it is also important to evaluate the multisystemic and life-cycle interaction that contextual factors have in the construction of sexual identity, which has been studied less (

Fredriksen-Goldsen 2011;

Mann et al. 2019;

Ribeiro-Gonçalves et al. 2023a).

The study of the development of sexual identity has increased importance for older gay and bisexual people considering the historical–generational, psychosocial, and personal context in which they developed, particularly for older Portuguese gay and bisexual people (

Correia 2017;

Olivos and Clayton 2017). This generation came of age in the context of the Salazar dictatorship (1933–1974), where same-sex behavior was persecuted, and people were extorted and assaulted, and even imprisoned. Furthermore, “homosexual acts” were criminalized and legally persecuted until 1982, similar to other neighboring countries, such as Italy and Spain (

Afonso 2019;

Correia 2017). This period of time represented a traumatic period for many of these older people, with the

Polícia Internacional e de Defesa do Estado (PIDE

1) carrying out multiple aggressive operations to eradicate the sexual expression of homosexual individuals, an oppression that only started to decrease after the revolution of 25 April 1974, when the dictatorship was overthrown through a military coup (

Afonso 2019). Consequently, older gay and bisexual people faced sexual stigmatization throughout much of their life cycle, associated with socio-cultural conservatism and sexual repression. The life narratives of these older people were often marked by the forced concealment of their sexual orientation, by the stigma associated with HIV, and they were one of the few generations that experienced two major public health pandemics throughout their life cycle—the HIV/AIDS pandemic in the 1980s and 1990s and the COVID-19 pandemic in the 2020s (

Landmann and Rohmann 2022;

Pereira et al. 2017;

Ribeiro-Gonçalves et al. 2023a). All these factors may have constrained the way older gay and bisexual people developed their sexual identity throughout their life cycle, the way they now feel more or less (dis)connected from their sexual identity, as well as the possibility to link with social and community groups of sexual minorities (

Pereira et al. 2017;

Watts et al. 2022). Furthermore, in recent years, the psychosocial context has undergone significant changes. The rights of sexual minorities in Portugal have been progressively defended and valued (e.g., inclusion of sexual orientation as a non-discrimination factor in the republic’s constitution in 2004; same-sex marriage law in 2010; adoption by same-sex couples’ in 2016) (

Afonso 2019;

Correia 2017;

Pereira et al. 2017). These have also enhanced the resilience characteristics previously available in these older GB people (

Pereira et al. 2017;

Ribeiro-Gonçalves et al. 2023b).

The Life Course Theory (LCT) is one of the most appropriate approaches used to assess the complexity of sexual identity development (

Elder et al. 2003). This theoretical approach has been widely used with older populations and describes five principles that allow us to systemically evaluate the phenomenon of identity development: (1) human development and aging as a lifelong process, considering that the biopsychosocial and identity development of humans occurs beyond childhood and that situations that occur in adult life are shaped by previous experiences and the meanings associated with them (e.g., situations of sexual stigmatization during aging are shaped by previous experiences of stigmatization); (2) historical time and place, stating that human lives are deeply influenced by socio-historical and cultural contexts, the “where” and “when” people develop influence their entire developmental path (e.g., development during a period of dictatorship in a ultra-conservative context); (3) timing in lives refers to the chronological ordering of events in people’s life cycle and refers to personal and generational times (e.g., adolescence and early adult life of this generation marked by strong sexual repression—generation of sexual liberation); (4) linked lives argues that human lives are lived interdependently, and that relationships (e.g., family, friends, neighbors, colleagues) shape how individuals interpret life events; and (5) human agency indicates that individuals are not passive agents of a predetermined life course, on the contrary, they make active decisions that determine their developmental direction (e.g., deciding to conceal their sexual orientation and isolate themselves from other sexual minority individuals to protect themselves from discrimination). The LCT also indicates that, during the developmental trajectory, people undergo gradual, and sometimes expected, changes to new personal, social and community roles/functions (transitions), as well as they can experience abrupt changes, with a more immediate need for adjustment (turning points). Thus, the personal response to challenges imposed throughout the life cycle are strongly influenced by the five previous principles (

Elder et al. 2003;

Elder and Shanahan 2006).

Research in Portugal, and elsewhere, on the development of sexual identity in older gay and bisexual people has been understudied, although the few available research results suggest a worryingly weak sense of community identity, combined with a significant lack of social presence and visibility compared with younger gay and bisexual generations (

Pereira 2020). The study of the development of sexual identity provides important clues about how older gay and bisexual people experienced decisive moments throughout their life cycle and how they integrated these events into their life narrative, allowing access to information that will be valuable for thinking about interventions in the field of well-being and mental health of these people (

Barrett et al. 2014;

Pereira et al. 2017;

Ribeiro-Gonçalves et al. 2019). Thus, the main objective of this study was to qualitatively evaluate the dimensions, in their multifactorial components and throughout their life cycle, that contributed to the development of sexual identity in older Portuguese gay and bisexual people through the Life Course Theory (LCT) (

Elder 1998). Namely, the influence of various families—origin, procreation and choice (

Allen and Roberto 2016)—and various turning-points and transitions—coming out, experiences under dictatorship, experience of stigma associated with HIV–AIDS, aging process and experience of COVID-19—in this identity development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study used a qualitative methodological approach, allowing access to the concrete experience of the participants, and used a descriptive and cross-sectional design. A non-probability sampling technique was implemented, through purposive and convenience sampling, and participants’ narratives were collected through semi-structured interviews and lifelines. This article uses data from a broader national mixed methods project called Pro-PSISexES with the aim of assessing health and well-being in older people in Portugal.

2.2. Participants

Participants were older people who met the following inclusion criteria: (1) being at least 60 years old, (2) identifying as men, (3) identifying as gay or bisexual and (4) not being institutionalized. The inclusion criteria for this study were defined with the intention of recruiting a homogeneous sample group, thus facilitating the identification of patterns in participants’ narratives. The final sample consisted of 22 older people of whom 91% (n = 20) identified as gay men and 9% (n = 2) as bisexual men. These people were 69.32 years old on average (SD = 6.57; range = 60–83 years) and all identified openly as cisgender. Slightly more than two-thirds did not have children (68.2%), and more than three-quarters did not have grandchildren (77.3%). Almost half lived alone (54.5%), while the remainder lived with a partner. Less than a third of these older people were married (31.8%) or single (31.8%), while less than a quarter were divorced (22.7%) and the remainder were widowed or in a civil partnership. Furthermore, slightly more than half were in a committed relationship (54.4%). More than two thirds were retired (68.2%) and the remainder were still working, with half of the older people having completed education up to high school (50%) and the other half having an undergraduate degree, master’s degree, or doctorate.

2.3. Materials

Three materials were used during a single interview with each participant.

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Questionnaire

This questionnaire was developed specifically for this study and was applied in an interview format, focusing on information such as age, gender, sexual orientation, who they lived with, marital status, whether they had children and grandchildren, whether they were in a committed relationship, professional activity, and education level.

2.3.2. Semi-Structured Interview

The semi-structured interview script was developed to study the development of sexual identity throughout the life cycle in older Portuguese gay and bisexual people. With this construct as the main research objective, all participants were invited to reflect on it through three initial questions focused on close family relationships: family of origin, family of procreation and family of choice (e.g., “Being a gay/bisexual man, how did your family of origin/procreation/choice

2 influence the construction of your sexual identity throughout your life?

3”). Subsequent questions invoked specific transitions and turning points in participants’ life cycle, such as the coming out process, the experience of sexuality under dictatorship and afterwards, the experience of HIV stigma during the 1980s and 1990s, the experience of the aging process, and the COVID-19 pandemic period (2020–2022). All these moments were explored using the same format (e.g., “As a gay/bisexual man, how is this aging process going for you?”). Some participants identified other transitions/turning points throughout their life cycle in addition to those previously defined in the interview script (e.g., experiences of ageism), which were also explored during the interview. The vast majority of questions were open-ended but guided by the topics that people narrated.

2.3.3. Lifeline

The Lifeline instrument (

de Vries et al. 2017) was used during the interviews, allowing the graphic identification of information and notable transitions/turning points throughout the life cycle. This instrument has been widely used with older populations and results in the improvement of the data collected since it facilitates recalling and deepening of the experiences reported during the interview (

de Vries 2013;

Assink and Schroots 2010). Participants were invited to mark on their Lifeline the most important moments of their life cycle identified during the interview, and they had access to pens and pencils of various colors, as well as a previously designed lifeline, which began on the day of birth, going through the day of the interview and moving on to the future. Participants were instructed to draw and/or sketch freely on their lifeline.

2.4. Procedures

Participant recruitment was carried out throughout the country, in two main ways: (1) intentional dissemination of the study through electronic means to people in all districts of Portugal through social networks and the team’s contact networks, including direct contact with LGBT organizations, and (2) invitations aimed at older gay and bisexual people who had participated in a previous broader study and made their contact details available. After the invitations, a first contact was made with each participant where the objectives and voluntary conditions of the study were presented, and the interview was scheduled. After the initial contact, two participants dropped out due to unforeseen life situations incompatible with participation. No participants dropped out during and after the interviews. The first author and participants met in quiet and safe places (e.g., university, participants’ home) where the interviews took place. Interviews were carried out by the main researcher (first author) or by one of two master-level students supervised and trained in interview techniques by the main researcher. Furthermore, the interviews were audio recorded after permission from the participants and lasted between 90 and 247 min, with an average duration of 130 min. After transcription, all interview audios were deleted. Five interviews were carried out online, via Zoom, due to the unavailability of in-person participation by the participants. Data collection took place between March 2022 and March 2023, and no payment or incentive was provided to participants.

Confidentiality safeguards were discussed with all participants and there was an opportunity to ask questions and clarify doubts before signing the consent letter. Furthermore, they were informed that any names and information that could identify them would be replaced by pseudonyms or omitted. At the end of the interview, each participant was given a debrief form to inform them of free psychological support resources, with partner entities, if necessary. A follow-up contact was also made, two days after the interview, to check on the well-being of the participant post-participation. All ethical conditions were considered, taking into account the 1964 Helsinki declaration. During the study, the team was particularly sensitive to the possible effects of cumulative stigma (sexual and age) and throughout the life cycle in these older people. This study was also approved by the Ethics Committee of ISPA—University Institute with approval code no. D/028/04/2020.

2.5. Data Analysis

The transcribed interviews were anonymized by replacing the names of participants and other people mentioned with pseudonyms, and other potentially identifying information (cities, places, etc.) were changed or omitted. The transcriptions were subsequently analyzed using the Codebook Thematic Analysis method (

Braun and Clarke 2022) using an inductive (or bottom up) approach and mostly semantic coding. The decision for an inductive approach was due to the almost non-existence of studies with this generation of gay and bisexual men, thus allowing greater flexibility in the initial stages of the analysis and a more exact (narrow and specific) definition of the research question in later stages of the analysis. More generally, thematic analysis was chosen as the data analysis approach as it is exceptionally useful in evaluating under-studied areas, such as gay and bisexual aging, allowing us to find patterns in participants’ narratives. Moreover, thematic analysis is a flexible approach that allows obtaining detailed, diverse, and complete data, essential for addressing participants’ identity aspects.

The analysis procedure had the following steps: the first author carried out an in-depth reading and review of all interviews—(1) familiarization with the data; then, a preliminary set of coding was carried out—(2) generating codes. The following phase included the primary identification of possibles themes, creation of preliminary thematic maps, and the identification of thematic patterns with the identification of six proto-themes, which were reviewed and discussed with the co-authors—(3) generating themes. The themes and the relationship between them were then analyzed based on previous coding, obtaining nine main themes—(4) reviewing themes. The penultimate step consisted of a detailed analysis of the nine themes previously identified, consequently identifying subthemes/subtopics, and culminating in the process of naming the themes—(5) defining and naming themes. Finally, the analytical narrative of the themes and the identification of illustrative excerpts were carried out—(6) final report. During these six steps, there were frequent meetings between team members (including the first and second to last authors and the two master students) to ensure consensus and consistency, reviewing themes/subthemes and the main discoveries that were occurring. The meetings were also essential to deepen the reflexivity of the analysis. This sequence of rigorously completed steps gave credibility to the process. Data analysis was carried out using the MAXQDA program (Version 22; VERBI Softwares, Berlim, Germany).

Our ontological approach was realistic with a contextualist epistemological perspective, analyzing the participants’ reported experience caused by complex social factors that are subjective and not directly analyzable (experience of the social political context of dictatorship, criminalization of homosexual behavior, social stigma associated with sexual orientation and HIV–AIDS) (

Fletcher 2016;

Pynn 2016). The guidance for the thematic analysis was experiential, focusing on the participants’ narrative and their processes of attributing meaning to their experiences. We used Life Course Theory (

Elder 1998) as a theoretical lens to evaluate sexual identity development in older gay and bisexual adults. In order to encompass a variety of perspectives and enrich the analysis, the team included researchers in aging, development throughout the life cycle and psychological adjustment to aging (first, third and second to last authors), who allowed a comprehensive reading of the life narrative and identity construction throughout the lives of older gay and bisexual people; a researcher in systemic approaches (second author), which allowed us a more in-depth multifactorial analysis of the contextual aspects in the construction of sexual identity; and a researcher in qualitative methodologies and identity development of sexual minorities (fourth author), who brought important contributions derived from theories of social justice and development of sexual minorities. The fourth and fifth author’s decades of experience working with gay and bisexual populations also facilitated access to participants in the fieldwork and helped to delve deeper into the phenomenon under study.

We conducted this study knowing that older gay and bisexual people in Portugal remain distant from the community and that they might feel apprehensive about exposing themselves and sharing intimate content with cisgender heterosexual researchers (first author). However, the first researcher of the study felt very welcomed by the participants and the narratives demonstrated a great depth and diversity of content shared. One of the main reasons for this interaction was that the researcher has already been working with the older LGBT community in Portugal for several years, which potentially allows greater security in participation by the older adults. As a team, we follow interactionist theoretical models, which present the individual’s relationship with the environment as essential for the construction of identity and the management of sexual stigma (Minority Stress Model; Conceptual Model of Sexual Stigma) (

Herek 2009;

Meyer 2003), and mainly systemic contextual psychological models, which present in a more specific way the different levels of macro and micro influences of the environment in the construction of individuals’ identity throughout the life narrative (Life Course Theory) (

Elder 1998). Furthermore, the team assumes as the main assumption of this study the existence of social inequalities, particularly in this older population, and that the study of these inequalities is contributing to facing social differences and injustices.

3. Results

The data were organized according to four major dimensions: the historical–cultural dimension; the psychosocial dimension; the relational dimension; and the intrapersonal dimension. These dimensions correspond to systemic levels of influence on the development of sexual identity, gradually corresponding from more distal levels of influence—macro—to more proximal levels—micro—and were developed in a narrative way with the help of Life Course Theory.

In the historical–cultural dimension, one theme was identified that is marked mainly by the historical time and place principle of the LCT and illustrates the Salazar dictatorship and cultural aspects as important phenomena for the development of the sexual identity of older gay and bisexual people: ‘This is… freedom?’, which addresses the experiences of repression and traditionalism before the 25 of April 1974 (end of the dictatorship regime), the changes after that and the promise of freedom. In the psychosocial dimension, the themes identified corresponded to the interaction between participants and their social context at various moments in the life cycle and in the development of their sexual identity, mainly the influence of various types of stigmas. To evaluate this dimension, the timing in lives principle of LCT was fundamental, and from this analysis four themes were identified: ‘Between scourges and pandemics’, which addressed feelings of fear, insecurity and the stigmatization derived from the HIV/AIDS pandemic and the feelings of loneliness resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic; ‘I’m old and… out of date?’, emphasizing the impact of ageism within and outside LGBT groups on their identity constitution; ‘The Cumulative stigma: The wound that never heals’, directed to narratives of early sexual stigmatization and subsequent reoccurrences; and lastly ‘Escaping to the city as a lifebuoy’, reflecting on the sexual repression of rural areas and the experience of escaping to larger cities.

In the relational dimension, the themes identified report participants’ experiences with close/family relationships and affective relationships that influenced the development of their sexual identity based, invariably, on the linked lives principle of LCT. In this dimension, two themes were identified: ‘Sexual orientation as the elephant in the room’, addressing experiences of purposeful omission of one’s sexual identity by their family and heterosexual partners, and the theme ‘The clandestine affection’, focusing on the clandestinity of homoaffective relationships and lived heterosexual relationships as a social facade. Finally, in the intrapersonal dimension, the themes identified predominantly individual and agency (or lack thereof) experiences of the participants that influenced their identity development, mainly aspects about feelings of (in)visibility. In this dimension, two themes were identified: ‘I became invisible, but also a survivor’, focusing on the dichotomy of hiding sexual identity simultaneously with an invisibility effect and a protective effect, and the theme ‘Identity is not to be exposed… It is to be lived behind closed doors’, where patterns of experiences of internalization of sexual stigma and contestation of the public “exposure” of sexual identity are presented. Next, within each dimension, the themes will be presented, and the identified patterns will be discussed. The thematic map resulting from this results section is presented below (

Figure 1).

3.1. Historical–Cultural Dimension

Participants spoke about historical and cultural aspects that contributed to the development of their sexual identity, before, during, and after the dictator regime, reflecting on one main theme: Is this… freedom? This theme reflected the experiences before and after the 25th of April.

Is This… Freedom?

Participants reflected on several traditionalist sociocultural demands prior to fall of the dictatorship, which contributed to the strong repression of sexual orientation and identity, whether within the family context: “These are times that have nothing to do with today, which shaped what we are. I got married very young because of my parents’ demands. I got married when I was 17”. (Gabriel, 65 years old) or in the broader social context, as Brás, 60 years old, says: “It was a very bad thing [homosexuality]. It was ‘faggot’ and that’s it. Even because of that, because of that label, it was very difficult for us to accept anything, it was an aggressive thing”, or André, 76 years old:

It [sexuality] was as repressed as possible! For everyone! There were street hook ups, there were urinal hook up, there were the morality police who went after homosexuals. The urinals were round, with black panels, but you could see people’s legs outside, and there were provocateurs, the morality police, who went there to provoke and then take the people inside [arrested].

In addition to this persecution, when these men were incarcerated, their experiences were disturbing:

All of this was scary. The terror I had, I wanted to be with those people that I wanted to belong to, but I was afraid. I… was arrested by PIDE [the morality police], I was in forced isolation, I had sleep torture, I had that kind of things, which at the time it left a big impression on me.

(Gabriel, 65 years old)

Most participants indicated that after the fall of the dictatorship, social conditions improved, including easier access to other sexual minorities and greater sexual freedom. The fall of the dictatorship was an important turning point, as the sense of social freedom began. However, they felt very disappointed as the clandestinity continued: “Some said ‘We are free’, but those ‘we are free’ were among those 3, or 4, or 5, because in the streets, for many years, self-repression continued and the repression from others. And it continues until today”. (André, 76 years old).

3.2. Psychosocial Dimension

Participants’ reports on the psychosocial aspects that contributed to the development of their sexual identity were evaluated on the psychological impact of various types of stigmas on development throughout the life cycle. Four themes were identified and are discussed below: (1) between scourges and pandemics, focusing on the feelings and stigmatization experienced in the HIV–AIDS and COVID-19 pandemics; (2) I’m old and… out of date?, addressing the impact of ageism on the construction of sexual identity; (3) the cumulative stigma: The wound that never heals, which synthesizes reports of sexual stigmatization at various moments in the life cycle and its effect on sexual identity; and (4) escaping to the city as a lifebuoy, which describes the effects of repression in rural areas and the experiences of fleeing to urban centers.

3.2.1. Between Scourges and Pandemics

Older gay and bisexual people are part of one of the few generations that has faced several serious public health crises at times of important developmental demands, including pandemics that influenced the development of sexual identity in early adulthood and well-being in later life. The HIV/AIDS pandemic in the 1980s and 1990s, which began when sexual minorities in Portugal were beginning to feel freer in experiencing their sexuality, about a decade after the fall of the dictatorship and the consequent decriminalization of same-sex behavior, was one of the main turning-points inducing of fear, concealment, and stigma:

Regarding HIV, I was very scared. It was very complicated. We are talking about 1987… There was still little talk and everyone was afraid. And then it was the ‘sissy disease’, they were afraid to touch anything that belonged to someone who had AIDS. People were in hiding!

(Orlando, 70 years old).

This pandemic period also generated chaos in the secure relationships of these older people, the relational loss was imminent: “We were dropping like flies… I lost many, I lost almost all my great friends…” (André, 76 years old). This threat to close relationships was revived in the forced isolation generated by the COVID-19 pandemic, two decades after the last pandemic: “Life became a little strange, sad, in that aspect the social aspect disappeared, it was extinguished!” (Emídio, 60 years old). Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic significantly reduced the sense of agency for older people, creating frustration and isolation, especially when it comes to intimate relationships: “There was risk everywhere. Everything is limited and with little support from other people. I even put an end to occasional dates!” (António, 71 years old). The two pandemics had a very prominent impact on social isolation and feelings of loneliness, but the HIV/AIDS pandemic was completely covered in stigma and further oppressed the expression of sexuality among these older people.

3.2.2. I’m Old and… Out of Date?

Participants indicated different social feelings of ageism that intersectionally shaped their sexual identity: “It’s not the same when you’re young and beautiful. For example, it’s unthinkable for me to go hand in hand with him [partner] on the street!” (Pedro, 66 years old). Furthermore, as 70-year-old Orlando indicates, ageism is felt to be highly prevalent within the LGBT community, which contributes to the older gay and bisexual people not feeling involved with the community: “I already have been rejected! I am always very careful when approaching… But I have been rejected because I am old!” Furthermore, this phenomenon ends up influencing more stable connections with other gay and bisexual people or potential relationships: “I feel in this market of immediate relationships that everything is very disposable, I feel for younger people!” (Emídio, 60 years old).

3.2.3. The Cumulative Stigma: The Wound That Never Heals

The sexual stigma experienced throughout the life cycle in a cumulative way has been a ‘ghost’ that accompanied the development of the sexual identity of older gay and bisexual people, being indicated as one of the main factors that contributed to suffering and isolation in moments of developmental transition. Early experiences with peers stand out: “This period was overall very unhappy for me. I was a victim of bullying at school” (Daniel, 73 years old) or with teachers, as Manuel, 72 years old, says:

By the standards of the time, I was considered effeminate, and the schools had what were called social workers. The social worker who was on duty at the high school thought that… she called me. And she had a conversation with me, I must have responded badly, and she didn’t do anything else. She spoke to the dean. The dean called my mother and from that moment on… The dean’s argument—today it seems like we are talking about science fiction—what he told me was: ‘Your son even bend his legs like women! And wearing shorts can excite his colleagues!’ This was an extraordinary thing!

This type of stigmatization was experienced repeatedly, in different contexts, such as within the family: “My father called me a sissy. Many times! But it wasn’t my fault! That’s it, it was my nature”. (Pedro, 66 years old), or in the army:

I was one of the defendants in the famous judicial process of homosexuals in the armed forces… And, therefore, all of this was tragic, yes. I know Portuguese boys, who were married, were caught up in the process, and their lives were destroyed. Some women left them, some had children. There were people who were extremely harmed! And it wasn’t one, not two, not three. There were hundreds!

(Manuel, 72 years old)

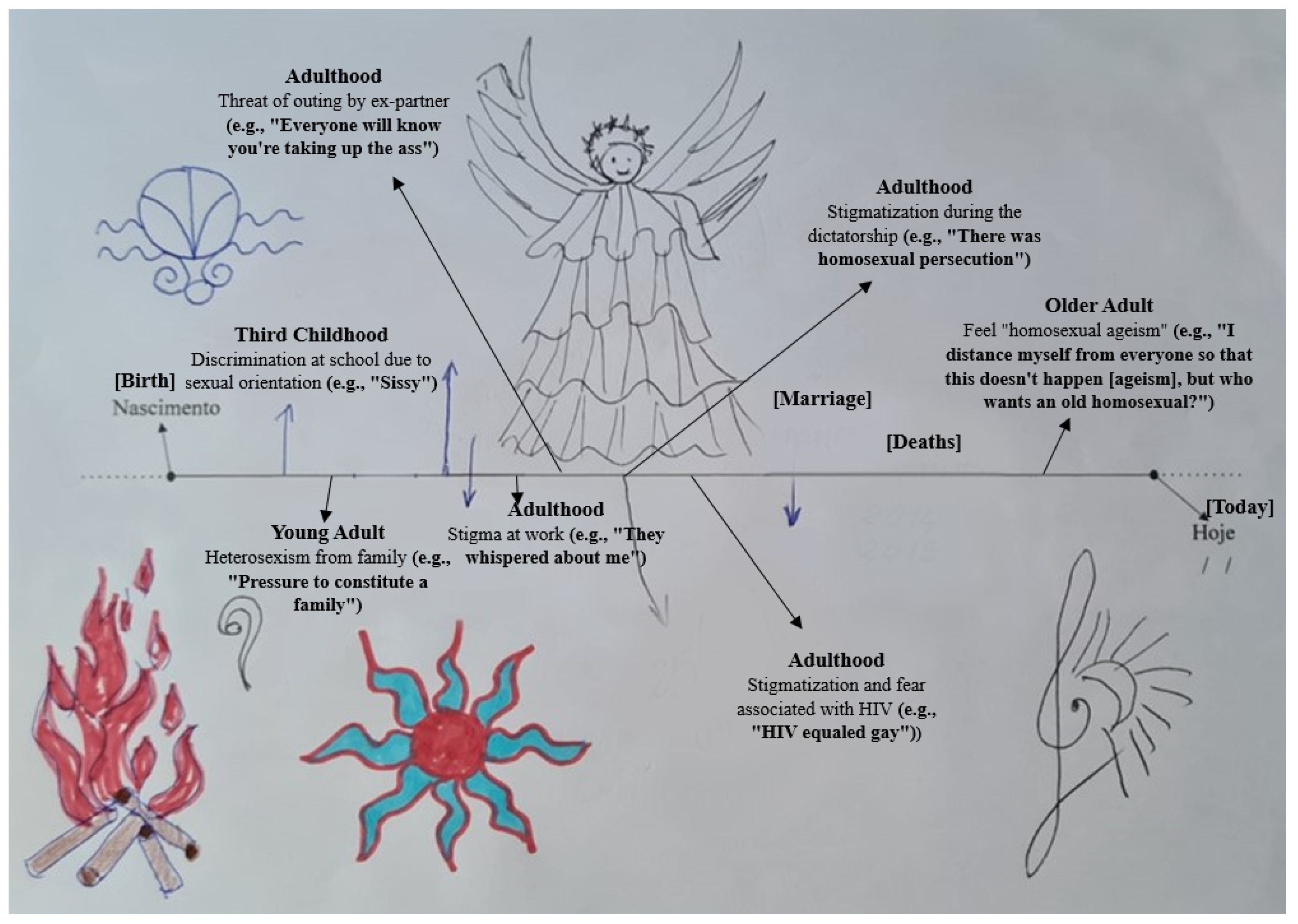

Even in the community, stigmatization continues to occur, as 60-year-old Fábio points out: “And neighbors say, ‘Man, the guy is a faggot… Let’s go and rob his car…’ That’s it. Do you understand? If I’m going to work, I have to hide the car far away because I’m scared!” Arlindo’s lifeline (83 years old) exemplifies this phenomenon of cumulative stigmatization throughout the life cycle (see

Figure 2).

3.2.4. Escaping to the City as a Lifebuoy

Living in a rural environment was important source of oppression for most older people who grew up in this context, influencing the possibility of finding others with whom they identify, belong, and experience freedom: “I felt clear differences. The approach to certain topics was completely different, the people. So there was a sense of wonder about being in Lisbon. That’s why I wanted to come to the big city. At least I felt free!” (John, 67 years old). However, despite the ‘fantasy’ of freedom offered by the transition to an urban environment, people continued to feel oppressed as the urban environment was not necessarily synonymous with acceptance, as Jorge, 61, says:

I lived in Lisbon, and there was a vast kind of sexual opportunities, although I was also a late bloomer there. But homosexuals were not accepted, they weren’t talked about, we went through a lot of prejudice. Therefore, homosexual life in Lisbon was an underground life, it continued to be an obviously hidden life.

3.3. Relational Dimension

The participants also narrated some relational aspects that were essential in the development of their sexual identity, mainly regarding their close/family relationships and affective relationships. Two main themes were identified: Sexual Orientation as the Elephant in the Room, which addresses the experiences of omission of sexual identity by family and heterosexual partners, and The Clandestine Affection, focusing on clandestine homoaffective relationships and heteronormative relationships as a social facade.

3.3.1. Sexual Orientation as the Elephant in the Room

Older gay and bisexual people reported various experiences of suffering, frustration, and indignation due to significant others purposely avoided talking about aspects associated with their sexual orientation, and thus feeling that and important part of their identity was being ignored: “It’s just one of the things that I struggle the most with this whole process… That’s it… People know [of his sexual orientation], but it’s taboo for them. And I wish they would talk! Move forward. It’s as if it wasn’t important to them”. (Orlando, 70 years old). This phenomenon is identified as one of the main deafening silences that hinder the full assumption of sexual identity, and come from various family members, including parents, siblings, and children, as exemplified by Tiago, 61 years old: “They knew perfectly well all along, I have no doubt! My father pretended not to understand, and my mother… but there was no conversation!”.

3.3.2. The Clandestine Affection

The clandestinity of living one’s sexuality was present in almost all of the narratives of older gay and bisexual people, being one of the most important and decisive factors for the development of sexual identity, particularly in the process of acceptance/concealment of sexual orientation and of same-sex relationships:

We lived on the same block, and instead of taking the opposite route to avoid passing by it [partner’s house]… I passed by on purpose! And at night I would walk the dogs and see the lights on… in other words, I also encouraged that obsession a little bit, it wasn’t necessary!

(Arlindo, 83 years old).

Many of these participants became involved in relationships with a person of a different sex as a way of enjoying social advantages, namely that the “facade” heterosexual relationship provided some heteronormativity perceived by society, as Vítor, 74, says:

I needed to have a big rock [heterosexual relationship], where I could go unnoticed in society. Then it’s hard for me to say this, because I have children that I love, who were born from this situation. And the people who lived with me, I also really like, but deep down that’s it, it was a refuge. Here, trying for ‘normality’. Between quotes.

Although these heterosexual relationships provided a shield against potential social stigmatization, they often generated suffering and internal conflict, especially when older adults had simultaneous same-sex relationships: “Afterwards it’s like this, everything is very closed. We can’t talk, we can’t unburden, and we always live in this anguish! Always afraid of being discovered”. (Gabriel, 65 years old).

3.4. Intrapersonal Dimension

Intrapersonal aspects that contributed to the development of the participants’ sexual identity were evaluated and discussed, especially current identity reflections on feelings of invisibility, their consequences, and the internalization of this invisibility. In this dimension, two themes were identified: I Became Invisible, but Also a Survivor, which describes reports about the concealment of sexual identity, about its protective and invisibility potential, and Identity is Not to be Exposed… It is to be Lived Behind Closed Doors, about not identifying with the current trend of public “exposure” of sexual identity and the occurrence internalized sexual stigma.

3.4.1. I Became Invisible, but Also a Survivor

Participants highlighted that for much of their life they actively hid their sexual orientation. This concealment contributed to generating feelings of invisibility, with a more diffuse sexual identity and experience of intimacy, as well as the distancing of people with the same sexual orientation, as 65-year-old Augusto indicates:

And I in fact, perhaps unconsciously, always established a shield, because I didn’t allow people to get too close to me! We live in a facade, people today have to understand that! We all live in a theater. I don’t like being vulnerable!

However, the concealment of sexual identity also served as a protective factor at various moments in life, the concealment served as an avoidant and adaptive pattern in the face of the adverse social conditions of the moment: “Look, I was born, my generation was born, in dictatorship, with censorship, with everything that implied. What we learned was… to hide!” (Júlio, 75 years old). Pedro’s lifeline (66 years old) exemplifies this phenomenon of hiding his sexual orientation and avoidance, sometimes as a survival strategy (see

Figure 3).

3.4.2. Identity Is Not to Be Exposed… It Is to Be Lived behind Closed Doors

Older gay and bisexual people clearly stated that they did not identify with the current standard in which sexual identity is “exposed” or openly discussed, indicating that the way they learned to manage their sexual identity does not correspond, nor is it consistent, with this current agency, as 73-year-old Jaime says:

I don’t identify with this Carnival! I think there is no need for outward signs of difference that then turn against us! Because then society comes to demand from us! I went there once [Pride] and I thought it was a Carnival! Why this exhibition? It does not dignify human beings!

Other participants echoed this sentiment, such as 67-year-old Humberto: “I have a concept about homosexuality that is a little… you must have already realized that I hate queers, it is what it is. I hate clownery. I hate carnivals. Anyway, I mean… Disclosing things, I don’t. In this aspect, I am more reserved”. This phenomenon of non-identification with the public discussion of sexual identity seems to derive from a process of stigma internalization, in which the concealment of sexual identity was often more adaptive throughout the life cycle than living it openly. However, this tendency to hide their sexual identity is a consequence of years of internalizing sexual stigma, which marked the sexual identity of these older people and their relationship with sexual minority groups: “I didn’t choose, because if I could choose, I would still choose not to be homosexual. Just because of what we suffered. And because homosexuals in general are stupid, they are ignorant”. (José, 72 years old).

4. Discussion

The main objective of this study was to examine the development of sexual identity throughout the life cycle of older Portuguese gay and bisexual people. In general, we observed a pattern of intermittent occurrence of contextual and psychosocial turning points throughout the development of these older gay and bisexual men’s sexual identity, which coincided with important developmental transitions throughout their life cycle. Among these, sexual oppression and dictatorial persecution that occurred during their adolescence/youth, the stigmatization due brought about by the HIV/AIDS pandemic during their early adulthood, the costly social changes oscillating between sexual stigmatization/repression of freedom during their adulthood, and lastly, the experiences of ageism that is prominent today. As Elder states (

Elder et al. 2003), more important than the occurrence of socio-contextual changes perse is the developmental moment at which these changes occur in a person’s life cycle. Thus, moments of transition and developmental adjustment in older gay and bisexual people have been constrained by the socio-cultural context with recurrent events of victimization and microaggressions that potentially hinder the sense of belonging with other sexual minorities and the connection and integration of their own sexual identity; This unfavorable context contributed to the occurrence of internalized sexual stigma, which was also observed in this study (

Duc et al. 2020;

Frost and Meyer 2009;

Huang et al. 2023).

Associated with contextual changes, we also found that a large part of the life trajectory of these older gay and bisexual people, especially during their youth and adulthood, was guided by close relationships dominated by implicit and purposeful failure to acknowledge their sexual orientation (e.g., family of origin), and clandestine intimate relationships. All together, these contextual, psychosocial, and relational factors seem to have contributed to the belief internalization that in order to be safe and survive in an oppressive environment, it would often be essential to disconnect, ignore and/or hide important parts of themselves, namely their sexual identity. This phenomenon appears to reflect what Watts and collaborators (

Watts et al. 2022) describe as a sense of (dis)connectedness, as the state/degree to which people feel (dis)connected to themselves, to others and/or to a broader collective based on their personal characteristics, which is fundamental to the sense of identity integration. Therefore, we propose this phenomenon as

Internalized Sexual Minority Disconnectedness considering that it refers to the degree of disconnection/concealment of one’s sexual identity as a form of protection or avoidance, and it refers to a process of internalization that ends up becoming integrated into one’s identity.

This internalization may no longer be adaptive in the experience and co-construction of sexual identity in older gay and bisexual people, and may be affecting the connection of this people to the LGBT community. Specifically, this is because the psychosocial context has changed drastically, with significant gains in recent decades on the rights of sexual minorities (

Pachankis and Bränström 2019;

Pereira et al. 2017). In fact, the social context was potentially one of the main sources that promoted this phenomenon of internalization. It was only at the beginning of the 1990s that there began to be a clearer openness to diversity and social acceptance of the various sexual orientations in Portugal. The opening of the first organization to reclaim the rights of sexual minorities (ILGA) and to offer a community space for the LGBT+ population only occurred in 1995, when these older people were between 40 and 50 years old. It was only in 2010 that same-sex marriage was legalized in Portugal and only in 2016 was same-sex adoption permitted, when these older people were already at or very close to a senior age (

Ribeiro-Gonçalves et al. 2023a;

Pereira et al. 2017). Thus, in this older generation, it is not common for there to be a feeling of belonging or support to sexual minority groups (

Santos et al. 2023). This fact reinforces what the literature has been suggesting in recent decades, that older gay and bisexual people show great resilience and stigma management capacity, potentially using improved coping strategies based on the previous challenges that they overcame during their life cycle (

Fredriksen-Goldsen 2011). Furthermore, several qualitative articles, such as the study by Boggs and collaborators (

Boggs et al. 2016), which included 73 sexual minority older adults, highlighted resilience in the face of discrimination throughout the life cycle as one of the main qualities for facing the challenges of aging.

We also observed a sense of agency by these older gay and bisexual men, dominated by the intentional concealment of their sexual orientation for most of their lives, often associated with the difficulties of balancing their desires with the demands and moral rules of the environment. Potentially, this pattern of managing their sexual orientation in secrecy means that current patterns of greater public presentation and discussion of sexual identity (e.g., pride) are not in line with the way that older gay and bisexual people perceive and live their sexual identity (

Cascais 2009). These older gay and bisexual men lived a large part of their life in the antithesis of exposing their sexual orientation and with these values they constituted their sexual identity, which can make it difficult to follow and integrate the drastic psychosocial and legislative changes of the last two decades, to which the younger generations are fully accustomed (

Ribeiro-Gonçalves et al. 2019;

Santos et al. 2023). Furthermore, previous studies highlighted that the concealment of sexual identity can function as an effective mechanism in the face of a stigmatizing and aggressive environment (

Pachankis 2007). Effectively, hiding one’s sexual identity allows direct protection from situations of violence and aggression, although studies also indicate that hiding one’s sexual orientation often implies implicit suffering, internalization of sexual stigma and an increased mental and physical health problems (

Fredriksen-Goldsen et al. 2012;

Walch et al. 2016). As a recent systematic review of qualitative studies that included almost half a hundred of participants (

Bratt et al. 2023) indicates, older gay and bisexual people strongly desired to be recognized for their unique life stories and characteristics, just like all other people, but sometimes it becomes imperative to hide these same characteristics so as not to increase the sense of personal vulnerability and protect their hard-won quality of life.

Lastly, we found that the development of the sexual identity of Portuguese gay and older bisexual men is strongly influenced by a multifactorial component, emerging from the socio-historical, psychosocial, relational, and intrapersonal spheres (see

Figure 4). This reality highlights the need for multidimensional interventions to decrease Internalized Sexual Minority Disconnectedness, including interventions that target internalized sexual stigma and sexual identity across the lifespan of older gay and bisexual adults (

Chaudoir et al. 2017;

Freestone et al. 2022). As previous studies indicate (

Cooney et al. 2013;

Olivos and Clayton 2017;

Ng et al. 2005;

Watts et al. 2022), the sense of belonging, the connection to social/cultural groups, and the implementation of life goals as a gay or bisexual man are one of the most important factors for their well-being and quality of life during aging.

Despite its strengths, this study also presented some limitations that are important to acknowledge, namely, the use of a non-probabilistic sample, which limits the generalization of the data. The recruitment of relatively younger older people (close to 65 years old), which excludes the development of the sexual identity of older people with a longer life trajectory. Furthermore, the interviews were slightly extensive, which could increase the possibility of responses influenced by some fatigue—especially in the final part of the interview.