Abstract

Informed by Alfred Schütz’s phenomenology of social relations and its recent developments addressing online relationality, this essay reflects on the differences between online and offline death-related experiences in contemporary Romania. In Orthodox death cultures, religious, social, and familial bonds overlap. Orthodox Christianity is sceptical about body–mind separation and values unmediated liturgical communities. It is, thus, pertinent to ask what death online brings and denies in terms of experience to Romanian internet users. Some preliminary findings from our fieldwork are discussed. So far, on Romanian Facebook, three clusters of experience emerged widely: 1. A realm of belief where faith, unchallenged by digital practices, “decodes” deadly events across life-worlds; 2. Experiences of resistance and ambivalence of those who are stuck “in-between“, that is, those less competent in their traditions, yet sceptical about digital change; 3. Death experiences seem less synchronised across life-worlds for those who value electronic proximity: digital death and real death obey different rules. Historical specificity, we shall conclude, sets typified combinations of motives for what Romanians do in the proximity of death and how they do it. Digital technologies modulate the “hows” and, less notably, the “whats”.

1. Introduction

“And who’s dying this digital death?” someone asked our consortium leader at a conference in Tallinn. The question is elementary to the point of being ironic, yet complicated to the point of paradox. Of all the modest answers we could think of, the following one suits our purpose best: no human dies a “digital death”, but all humans (with internet access) experience the sociocultural implications of death in digital environments (Pitsillides et al. 2013; Savin-Baden and Mason-Robbie 2020). This answer becomes a premise for our discussion.

For reasons of shortage of space, this essay proposes a mainly theoretical reflection aiming to initiate further debate. However, we pay constant attention to our rich field notes. From 2022–2023, we interviewed 25 Romanian Facebook users about their online and offline death-related experiences. The point of departure for our investigation was Alfred Schütz’s phenomenology of social relations with recent developments addressing online relationality. Thorough ethical and methodological considerations associated with data collection are not described here. However, the readers of this essay should still be able to form an idea about our methodological proceedings from the following: We used traditional and virtual snowball sampling methods to reach individuals in their (grief and religious) groups on Facebook, as well as at wakes, burials, celebrations, and (in)formal family gatherings. We approached 20 individuals with Facebook accounts who either suffered a loss in the last two years or had prolonged contact with severely ill persons. In addition, we sought out five Orthodox priests and spiritual leaders who regularly express their views on Facebook. We had direct, prolonged contact with all our respondents in their everyday offline and online contexts, and we employed participant and non-participant (simple) observation to thoroughly document the interviews. It was through the Schützian multi-layered exploration of everyday interactions that we learned to pay attention not only to self-reported experiences and personal meanings but also to what our participants do in death-related contexts (personal space, physical locations, expressive bodily movements during interactions, etc.). The interviews were prearranged and semi-structured, lasting between one hour and one hour and a half, with at least one follow-up meeting and multiple follow-up messages. The conversations usually took place in confined, “privileged” places such as cemeteries, chapels, monasteries, and sometimes in the participants’ homes. We asked our respondents not to reveal intimate biographical details or other personal identifiers. Instead, we were interested in the subtleties and the richness of their motives to go on Facebook or to refrain from it during or after severe crises; in how they assess their personal and/or professional death-related experience in offline and online environments; in their manners of interaction with other community/group participants; and, finally, in their broad perspective on life and death in their interpersonal and community dimensions.

The findings we discuss in this essay are more than anecdotal evidence. In the preliminary process of data analysis, they emerged with a frequency high enough to make them worthy of general reflection. The reader can regard the data as merely illustrative or as inputs into how Schützian categories can illuminate complex multi-layered human relationships across multiple life-worlds.

The centrality of relation in human life is a consequence of the corporeal grounding of our existence (Ickes et al. 2004; Kim 2001; Schütz 1941; Sullivan 1953; van der Kolk 2014). No one was born with a sense of digital connectedness. Digital natives were themselves infants dependent on the physical care of other humans. Although immersed in digital technologies, our lives of flesh are led in concrete historical contexts (Schütz and Luckmann 1973, pp. 49–50). At the intersection of global trends with concrete people, entanglements arise: things change faster than individuals’ ability to make those changes meaningful. Of all existential concerns, sorrow calls most urgently for meaningful relational renovation (Klass 2013; McCarthy et al. 2023). In digitally advanced societies, the role of unmediated interpersonal interaction in times of sorrow is, understandingly, relativised. To what extent? In what ways? Socio-historical factors are at play here.

In Orthodox death cultures, religious and socio-familial bonds overlap. In Romania, communal and interpersonal relatedness is the most well-preserved element of a rather disintegrating death culture: extended family is responsible for how death is handled ceremonially, logistically, and emotionally (Andreesco and Bacou 2011). Orthodox Christianity values the dead body and in-person liturgical communion. It is, thus, pertinent to ask what “digital death” brings and denies in terms of experience for Romanian internet users.

This essay has three more sections: a basic description of Schütz’s social phenomenology followed by a short review of relevant scholarly developments addressing the digital life-world; a brief overview of the socio-theological specificity of Orthodox death culture; a fourth section that employs the previous three as support for reflection around the illustrative material; and a concluding section.

2. Schütz’s Social Phenomenology and Digital Life-Worlds

Alfred Schütz’s phenomenology of social relations, although a less obvious choice of theory, has the advantage of tackling complex multi-layered relational experiences across multiple realms. Here we describe the categories we will employ in the next sections.

The Austrian phenomenologist accounts for the intrinsically social character of the structures of the everyday world (Schütz [1932] 1967, 1970a, 1989; Schütz and Luckmann 1973). Why do we understand each other without directly accessing each other’s minds? Schütz’s answer is sociological: we understand each other because we share the same world. Our everyday world is not our private world (Schütz and Luckmann 1973, p. 4), but an intersubjective world undecomposable in distinct subjectivities (Vargas 2020). We exist in the sensibly perceived presence of others, with them, through them in a spatiotemporal unity called “co-presence” or a “we-relationship” (Schütz [1932] 1967, p. 163). Humans learn to ascribe “an inside to an outside” (Schütz 1989, p. 111): we come to recognise symptoms of others’ inner lives by understanding how body, voice, and facial expressions blend together (Turkle 2015, p. 611). Interacting is sharing a “vivid present” (Gurwitsch/Schütz 1970c, p. XXIV). It is precisely the experience of shared temporality that activates a keen sense of otherness: “The result is that I am incomparably better attuned to him than I am to myself” (Schütz [1932] 1967, p. 169).

We can grasp each other’s uniqueness only in a “we-relationship”: “As long as man is born of woman, (…) the we-relationship will be the foundation of all other categories of human existence. The possibility of reflection on the self, the discovery of the ego (…), the possibility of all communication (…) are founded on the primal experience of the we-relationship” (Schütz 1970c, p. 82).

Outside the “we-relationship” zone, social relationships always have a degree of anonymity. People we have met little or not at all are, in variable degrees, ideal types. We relate to our contemporaries (distant in space) and to our predecessors or successors (distant in time and space) through typifications. We typify their roles, motives, expectations, attitudes, and personalities (Schütz [1932] 1967, p. 184). We even typify ourselves attempting to fulfil others’ typified expectations of us. In a growingly abstract world, we inevitably rely more on typified knowledge and less on interpersonal trust (Giddens 1990, p. 83).

Our predecessors greatly influence how we presently live. We were born in their world. Our socialisation implies getting good at what they know: norms, categories, and definitions. We take their “stock of knowledge” for granted until we encounter a problem that needs a different approach. Stocks of knowledge are ever-updatable (Schütz and Luckmann 1973, pp. 99–241).

Human conduct is best understood from the actors’ perspective by looking at their attitudes and motivational contexts: “subjectively meaningful experiences of spontaneity, be they those of inner life or those gearing into the outer world” (Schütz 1945, p. 211). Attitudes are hardly motivated. They are sediments of past lived experiences “consisting of expectations, hypothetical relevances, plans for acts, skills, and other elements of habitual knowledge” (Schütz and Luckmann 1973, p. 217). By contrast, our motives have specificity: they biographically situate our actions and structure our plans (Weigert 1975). We express our motives in “in-order-to” and “because-of” sentences (Schütz and Luckmann 1973, p. 210). “In-order-to” motives are subjective, depicting an imagined course of action. By contrast, “because-of” motives are “difficult to thematise” (Schütz and Luckmann 1973, p. 219) and often unknown to actors, yet obvious to vigilant outsiders.

“The paramount reality” is full of opacities, surmountable obstacles, and insurmountable barriers (Schütz and Luckmann 1973; Luckmann 1970). Schützian intersubjectivity is intrinsically constraining, but the intersubjective reality is not our only reality (Schütz 1945). We get easily absorbed by worlds we can better manage: daydreaming, meditation, and romances of chivalry (Schütz 1976, pp. 135–58). A banker by day and a sociologist by night (Natanson 1970), Schütz was a man of many realms himself. These realms have finite, permeable “provinces of meaning” upon which one confers, if one feels motivated, the accent of reality (Schütz 1945, 1970b, 1976; Schütz and Luckmann 1973). They permeate the everyday world, enabling specific cognitive styles, plausibility structures, and criteria for understanding ourselves and others. In Quixote’s famous case, a hermetically closed realm of chivalry completely replaced commonsensical reality (Schütz 1976, p. 157).

Unsurprisingly, the phenomenological tradition has long informed the design of technologies (Ihde 1990, 2010; Kaptelinin 2018; Kim 2001; Mann 2001; Peters 2015; Turkle 2012; Wertheim 1999). In the late 1990s, computer scientist Steve Mann wrote about the “existential computer” (Mann 1997). Soon after, Johaan Kim wrote about being-in-the world-wide-web as an authentic mode of Dasein (“Digi-Sein”) (Kim 2001).

Today we exist in the world in our concreteness, and then we exist in the world-wide-web in our multiplicity, as precariously embodied cyber-selves (Bassett 2015; Kim 2001; Pace Giannotta 2019; Stenger 1991; Stokes 2021; Turkle 1995, 2012; Wertheim 1999). Continuous connectivity has led to problematic changes in our modes of being in the world (Cerulo 1997; Epstein 2012; Hansen 2015; Savin-Baden 2019). The Swedish media researcher Amanda Lagerkvist scrutinised these overly affective, deeply vulnerable “existential terrains of connectivity” (Lagerkvist 2015, 2017a, 2017b, 2019). For Lagerkvist, “an embodied sense of human self” (Lagerkvist 2017a, p. 190) is indisputable. Although our “media bodies” are essentially ambiguous, bodies can still be reclaimed beyond the online/offline distinction (Lagerkvist 2017a, pp. 189–90).

A fleshy body with its “naive” functions cannot be reclaimed across life-worlds, we venture to suggest. Technology has reclaimed our bodies instead. Bodies become instruments of exchange “with the technical milieu” (Epstein 2012, p. 205). Online bodily experiences rely on the “mind’s touch” (Meyer et al. 2011; Mühlhoff 2015; Schuetze 2021; Slaby 2014), not on basic physical functions. Only a “naive” body can perhaps engage in a Schützian vivid present with another body.

Sherry Turkle, the MIT expert in human–machine interaction writes:

“Look at me when you speak to me. We teach children the outward manifestations of full attention (…) [to] get them to a more profound feeling state. This is the feeling state of attachment and empathic connection”.(Turkle 2015, p. 74)

Fully processing others’ psychological states is a demanding, slow journey. In digital interactions, “the rapidity and parallel processing of attention-requiring information” (Immordino-Yang et al. 2009, p. 8024; Damasio 1999) hinders longer-processed emotions such as compassion and admiration. More metaphorically than conceptually, only a failing, wounded body can fully develop a sense of life.

Co-presence in physical space, as we knew it (Cooley 1956; Goffman 1963; Mead [1934] 1962), needed redefining to include disembodied interactions in “electronic proximity” (Dertouzos 1998). Sociologist Shanyang Zhao (2003, 2004, 2006, 2007, 2015) argued for a new Schützian life-world realm: a “there and now” zone called “tele-co-presence” (Zhao 2015, p. 114) where mutual intelligibility is largely based on affinities (Zhao 2015, p. 117). For sharing a “vivid present”, users resort to multimedia interfaces; for carrying meanings, texting “serves as a better vehicle than oral language” (Zhao 2006, p. 462). “Tele-co-presence”, Zhao concludes, leads to disclosure and intimacy. But Turkle sees it differently: digital communication lowers interpersonal risks (one can always edit problematic messages) (Turkle 2015, p. 77). Where Zhao sees “intimate strangers” sharing a “subjective meaning context (…) through communicative action (…) by way of mutual biographical disclosures” (Zhao 2015, p. 117; 2004), Turkle sees the opposite: fear of intimacy. The digital world, she argues, is infused with someone’s intimate presence, leading individuals away from intimacy itself (Turkle 2015, p. 25).

Precisely like Schützian intersubjectivity, intimacy refers to structural, mostly pre-communicative ways of relating to others (Bregman 1973). Schütz and Luckmann (1973, p. 219) hints at the foundational role of intersubjectivity in building closeness, empathy, and interpersonal trust when showing that one’s motives are more intelligible to attentive others than to oneself.

As we will see from Section 3 onwards, Christian Orthodox rituals require intense multi-sensorial engagement with others, dead or alive. Schütz’s categories can help us keep track of the “gains” and “losses” implied by the relativisation of co-presence when death is experienced across realms.

3. Romanian Orthodox Christianity

Human concrete existence emerges, thrives, and declines in a woven fabric of historical contingencies. Worldviews are more than cultural heritage; they go deep into the foundation of one’s “scheme of things” (Norris and Inglehart 2011; Solomon et al. 2015; Toplean 2021). Attitudes towards existence do not change speedily and uniformly (Davie 2010, pp. 229–30).

“This change is exhausting!” an Orthodox priest commented on his own live sermon on Facebook. The change, however, imposed itself: nearly 90% of Romanians are internet users and 60% have a Facebook account (Data Portal 2023). A total of 85.3% of Romanians were self-declared Orthodox Christians in 2021, that is, three million less than what the 2011 census data showed (Recensământ 2021; Cornea 2023). According to Pew Research Center (2018), Romanians are the most religious Europeans, with 54% describing themselves as “very religious” and 64% declaring their “absolute faith” in God. A total of 70% of the young participants in a Reveal Market Research survey (Reveal Market Research 2021) pray and 63% light candles for the souls of the dead. Nevertheless, the number of atheists has tripled in the last 10 years (reaching 60,000); the number of those without a declared religious affiliation also rose from 20,000 to 70,000 (Recensământ 2021; Cornea 2023).

The non-separation of death culture, Orthodox Christianity, and state institutions remains a feature of contemporary Romania; their intersections are constantly reinterpreted theoretically and recoloured politically (Bănică and Mihăilescu 2017; Roudometof 2010; Stan and Turcescu 2007; Toplean 2015, 2018, 2021). Intricacies are not discussed here, but the tension between two contrasting historical processes is acknowledged: a generation-long forced de-traditionalisation under communism and an encouraged nostalgic return to traditions overlapping with rapid globalisation and under-accomplished democratic measures under post-communism. Such dissonant tensions are less noticeable in statistics, but noticeable in “informal rules” (Brown 2009, p. 580; Patapievici 2015, pp. 207–18) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Wayside crucifixion protecting Romanian drivers (source: the author).

Five traits of Orthodox Christianity have shaped Romanian death culture: 1. A vocation for unmediated community life. The “Living Tradition” (Clémént 2019; Evdokimov 2000; Popovici 2003; Lossky 2017; Meyendorff 2011; Stăniloaie 1969, 1971; Yannars 2011) evokes a Schützian “vivid present”: predecessors, contemporaries, and successors constitute “the we”, sharing a felt presence, a dynamic yet unchanging line of belief (Hervieu-Léger 2000, p. 160); 2. Centrality of the body is emphasised in hesychasm, a crucial psychosomatic practice ensuring the same spiritual path for body and soul (Clémént 1995; Lossky 2022; Ware 1988). Death sacraments also revolve around the body (Figure 2). The Holy Unction for the ill leads to either recovery or to speeding up body/soul separation (Larchet 2001, 2002, 2010; Sfântul Maslu 2022). “Koliva” (a popular cake for funerals and memorials) symbolises the material body longing for the sweetness of redemption; 3. Magic healing practices, although condemned by official teachings, remain crucial in Romanian spirituality (Aghioritul 2003; Candrea [1944] 1999; Cojocaru 1949; Olteanu 1999; Pavelescu 1998); 4. The Romanian Orthodox Church (ROC) opposes suicide and all forms of euthanasia. Following Christ, believers should overcome their fear of physical suffering (Larchet 2010; Lazurca 2022); 5. The ROC’s institutional inertia and complex political past has caused an overall ambivalent attitude towards socio-political change (Makrides 2012; Preda 2011; Rotar 2013, 2021; Stan and Turcescu 2007; Toplean 2018, 2020, 2023; Verdery 1996, 1999). In recent years, the Romanian Patriarchate’s Basilica Press Centre has strengthened, through its many branches, its online presence, making room for pro-modernisation voices often met with hostile resistance by the mass of the faithful. The ROC’s ambivalence has grown to be structural.

Figure 2.

Family farewell: the deceased’s hand/forehead is kissed before the coffin is closed (source: the author).

The Orthodox theologian Adrian Lemeni (2022) discusses the conditions of Orthodox belief in the digital age. He recommends digital moderation with four arguments: 1. Being online reduces “trezvia”, the capacity to be spiritually awake, that is, fully present to others (Lemeni 2022, p. 9); 2. Orthodox Christianity is about directly experiencing life (Lemeni 2022, p. 462); 3. Cyberspace suspends the realm of concreteness and encourages dualistic thinking (Lemeni 2022, p. 524; Couliano 1992; Stenger 1991; Wertheim 1999). Technology promises a gnostic (disembodied, artificially amplified) mind, yet Christ cannot save immortal minds: transcendence is accessible solely to the human soul. 4. Media is always the message (McLuhan 1964): machines have a “spirit” of their own and once it enters us, it becomes us (Lemeni 2022, p. 462). In Schützian terms, one finite realm tends to encapsulate the entire human experience.

4. Fieldwork Notes

4.1. Miraculous Polenta1

“I cried a lot today (…) I received a message from two faithful ladies (…) to mention in my prayers a three-year-old girl, Eveline. The girl (…) would not wake up. Her mother kept trying (…). Nothing. The child was in a coma. Devastated, the mother rushed her to the hospital. (…) The doctors were very reserved. They intubated her immediately. I say to one of the ladies: ‘Please (…) pray the Paraklesis to the Mother of God and the Akathist of St. John the Russian.’ The despaired woman writes to me: ‘We can’t do anything, Father! Our prayers have no more value than a polenta.’ I insisted that she pray anyway. Today, I have mentioned Eveline at the Holy Altar, on the day of Saint Theodora of Sihla. Later in the evening, this lady writes to me: the little girl woke up from the coma and asked for polenta! I started to shake (…) God is wonderful and so are His Saints!”.

This text was written by an Orthodox priest on his Facebook page. It was liked more than seven thousand times and shared over 1.5 thousand times with renewed success. In over 600 comments, Facebook users praised God and asked for prayer guidance for dying family members. Comments and shares show no traces of cynicism. Their spiritual relevance is self-evident to everybody. Apparently, a religious stock of death knowledge is revealed intact online. Moreover, sense-making is used to reinforce users’ motivation for religious behaviour outside the online world (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Fragment of a handwritten testimony of a healing miracle uploaded on Facebook (source: Facebook page “Sfântul Nectarie și Sfântul Ioan Rusul” [Saint Nektarios and Saint John The Russian]).

“Miraculous Polenta” is highly relevant and highly typified: the users’ motives and expectations are structured and comprehended in accordance with the traditional Orthodox stock of knowledge. It is an assemblage, on a smaller scale, of the realm of belief. In this sense, the digital life-world is no less permeable to the “other condition” than the standard life-world (Berger 1970, p. 224). Relationally, emotionally, and physically engaging verbal and non-verbal actions articulate together this realm of belief which is typified, not stereotyped: an organised, recognisable, plausible shared way of organising the interpersonal chain of belief across life-worlds.

Science and technology have hardly led to a rise of rationalism in Orthodox countries (Roussou 2022). Recently, a growing interest in saints that heal incurable diseases has been attested (Stahl 2013, 2018, 2022; Stahl and Venbrux 2011). With the internet, available “evidence” for belief in miraculous healings has increased exponentially. The Facebook page of the two most important saints that cure cancer and heart diseases, Saint John the Russian (mentioned in “Miraculous Polenta”) and Saint Nektarios of Aegina, has 51,000 followers.

The faith of our 11 religious interviewees is unchallenged by digitality, preliminary findings show. The meanings implied by the realm of belief do not collide with their everyday digital communication practices. Believers still live, pray, die, and hope for resurrection in the body in multi-sensorial liturgical communities. Their adored saints are not digitally “optimised” saints: their relics need to be worshipped, touched, and kissed (Bănică 2014). Many members of religious online groups visit monasteries they follow online and read their prayers on WhatsApp in the subway. However, during discussions, no recasting of traditional meanings was brought up. In the realm of belief, the only “because-of” motive that really works is faith. Faith provides discernment criteria across life-worlds. A 54-year-old woman embarks on in-person pilgrimages twice a year, but as a keeper of faith understands the “deeper” rules of the game:

“Many people have been healed by miraculous icons they’ve never even seen. Someone describes the icon for them, they kneel (…) become cured (…) I’ve seen God’s power twice during COVID”.

Digital pictures of miraculous icons can be healing. They are considered “helpful” for those unable to leave the bed (Figure 4). Such icons are shared across dozens of various religious pages and groups (some with over 800,000 members). Religious groups are used for daily spiritual support, including for the ill and the grieving.

Figure 4.

Healing icon (Source: Facebook group “Puterea Rugăciunii”).

What sets the ground for mutual understanding is the reciprocal acknowledgement of living in wounded bodies and the hope to be saved in renewed bodies as members of a community of faith. They permanently reconnect to “the we”, across time, space, and life-worlds. This, we suggest, does not reflect the historical particularity of Orthodox belief, but the nature of religion itself. The digital world is thus systematised according to their categories of belief: transcending everydayness and reaching “the other condition” is believers’ predominant motive.

4.2. “In-Between”

Outside the enclave of belief, typical relational solutions for “the problem” of death seem “problematic”. The patterns of reciprocal expectations are broken. A feeling of estrangement from others and from the paramount reality itself is what we have noticed in seven months of background fieldwork through half-deserted villages and mono-industrial towns. Traditional modes of experiencing others make less sense to more people. The pandemic years and the neighbouring war have aggravated their lack of confidence in the common stocks of death knowledge. For a deeply collectivistic culture, an abruptly diminished focus on “we-relationship” communities has changed individuals’ existential situations in imponderable ways (Woodthorpe 2017).

The everyday world is the world “to which our trust relates” (Möllering 2001, p. 412; Anne Brown 2020; Parr and Davidson 2008), and it is not uncommon for Romanian Facebook users to hardly or never mention a loss online. Many informants find it “unsafe”, “pointless”, and “distasteful”. A 64-year-old respondent found it “efficient”; his “because-of” motive leaves open the question of (un)trustful online relationships in vulnerable moments.

“I didn’t have the strength to call everyone, so I posted on Facebook (…) I don’t see this (…) in any way. (…) I actually did very little. (…) I don’t feel like discussing publicly what concerns me (…) I don’t remember what I specifically thought. (…) I didn’t say much. I wrote that she passed and added [her favourite] music”.

The suffering must be eye-witnessed suggests an Orthodox priest and podcaster:

“Pain is a heavy burden. (…) you have to be there in person (…) for the members of the parish”.

While the spatial proximity with the sorrowful and the dying is challenging, the “safe” distance of tele-co-presence feels untruthful. A young interviewee reflects:

“I was quite lonely after mom’s death, with a newborn (…) I looked for help at mom’s church. (…) The priest was disgusting, so judgmental and cold. (…) I was on this group for manicurists looking for work, chatting (…), and never said a word about (…) my mom. There’s no point, you can’t trust them, so many crazy ones, so much pretence”.

Most informants have unfavourable expectations from others. The limited disclosure of pain and ambivalent emotional attachment to Facebook “friends” may point at the complex dynamic of trust in post-communist countries. Institutionalised distrust (Toplean 2021) blends with common knowledge, typifying others as “spies”, “ill-intended”, or “nosy” (see also Toplean 2015). This contrasts with an expansive, extrovert traditional death culture where, in a past not too distant, mimesis (affect contagion, non-linguistic alliances) regulated calamities (Gibbs 2010, p. 191; Scheff 1990, 1997). This may indicate a deeper, structural “Durkheimian” loss: a loss of a religious sense of being with others. With trust comes “a socio-psychological quasi-religious faith”, Simmel showed (Simmel 2004, p. 179). Our sense of intersubjectivity, too, may be linked to this faith.

At the Orthodox funerals we observed for documenting the interviews, participants look around for cues knowing they are expected to have skills and motivation for ritual engagement. Some have neutral expressions, staring at the ground; others look embarrassed, fumbling with phones and avoiding eye contact. The biggest online platform for funeral services (condoleante.ro; Accessed on 12 October 2023) provides useful Orthodox guides to funerals. Our informants did not check it. A 33-year-old man explains: “Romania is full of funerary homes and notary offices; no need to look online for death info!” Indeed, almost every flower shop sells funeral arrangements, and every bakery sells “Koliva”. Romanian death culture has an intact, tangible shell (Figure 5).

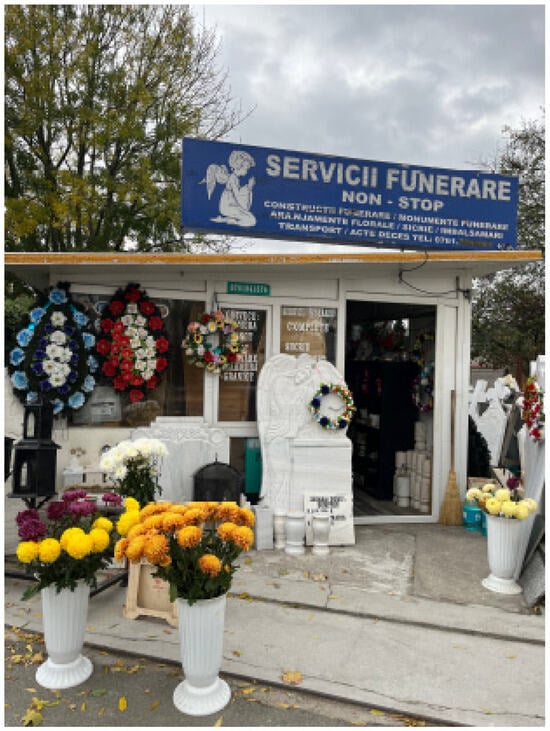

Figure 5.

Typical urban non-stop funerary service (source: the author).

Preliminary findings show that Orthodox religious belonging remains important outside the realm of belief. The authority of the past is challenged but recognised. People know they are losing fluency in their traditions. Problematising happens, but solutions clash. A reflective, practical return to “homey” death has reemerged. The world within one’s reach has a commitment quality to it that is actively valued. A 48-year-old interviewee said:

“(…) my sister was with him (…) said, “Dad, if you can hear me, don’t worry, we’re all fine. You go in peace…” (…) He took a deep breath and died. Every time I remember this I have a good feeling. (…) What a huge good! (…) family telling you it’s fine (…) Can you ask for more?”

A 33-year-old while attending the Orthodox wake of a cousin said:

“I feel powerless. (…) It paralyses me. I don’t even know what to say, all that crying, they look disfigured, I feel like (…) facing a crime scene (…) something evil”.

Impurity and evil threaten the order of the everyday world: a basic “hard truth” from where all religion springs. Facing death without tradition, as Walter (1995) put it, involves rediscovering hard truths on one’s own. The respondent continues:

“Should I decide (…) [about] my digital traces? Why should I care? I only care about those who knew me in person. They’ll drink for me and light a candle (…) You put your intense moments online, you dilute them, you become nothing, persons become information (…)”

How much value one places on one’s digital legacy is a highly subjective judgment (Sofka et al. 2017, p. 191). In Schütz’s categories, digital immortality is a “natural concern” only when the digital realm is not an abolishable reality, but a proper life-world.

To conclude, a declining religious cognitive style does not mean rejecting the social benefits of belonging to the majority religion (Toplean 2015; Putnam 2000). Many show dissatisfaction with available stocks of death knowledge, poorly perform traditional rituals, and mention personal blockages rather than personal solutions. They are ambivalent about the past, distrust the present, and deny the (digital) future. Their experience with “digital death” is limited, contextual, and often evaluated as irrelevant. The online space is too inclusive and transparent, the offline one is too exclusive and opaque.

4.3. “I Lose Her Every Day”

A 19-year-old never experienced “the newness” of cyberspace, saying:

“I post about mom (…) so I feel I live through her death (…) I post about her every day, and I lose her every day”.

For this daughter, to be is to be online and to be online is to feel: one vulnerable existential condition, one wide-open existential space with no perceivable tension between realms (Lupton 2015, p. 168; Stokes 2021, p. 38). Interested in the psychological subtleties of connectedness, Turkle (2015, pp. 76–77) suggests differently: the online is more existentially gratifying than the offline for people who would rather text than talk. When connected, one is “forever elsewhere” (Turkle 2015, p. 10). In tele-co-presence, people feel heard. Being with spatially distant people is more vivifying than “just being” with those within one’s reach. Being more tele-co-present than co-present also means fewer in-person conversations. Direct interactions are frustrating. For example, a grieving mother feels uncomfortable in ways that are easily avoided online:

“My colleagues (…) asked [6 months after losing him]: “Still not OK? This boy won’t let you live! See a priest!” (…) I was so angry (…) bothered by their stupid remarks! (…) At least here [online group] everyone’s been through something (…)”.

She preceded her comment with this:

“I need to post him (…) I post (…) un-disturbing things (…) playing soccer (…) Suffering doesn’t scare me (…) forgetting (…) is my biggest fear. (…) I’ve seen selfies of crying mothers (…) how deranged is that!”

Within online groups, one tends to craft the most acceptable version of one’s vulnerability: an intricate interplay of authenticity and “pretence”, of spontaneous devotion and “staged” melancholy. Above all, Turkle (2015) thinks, it is the feeling of being in control. The world of co-presence does not grant such privileges.

The largest seven Romanian Facebook grief groups have between 300,000 and 100,000 members. They are exceeded in size and engagement by religious groups. Their content, however, is interchangeable: predominantly religious, often impersonal (Orthodox icons, romantic landscapes, funeral memes). Personalised posts are more successful, but less frequent (Figure 6 and Figure 7). Recurrent neutral religious messages with phatic function (Stage and Hougaard 2018) provide more adequate contexts for affective interlocking among prudent mourners (Brennan 2004; Savin-Baden 2022; Stiller and Dunbar 2007). The frequent “in-order-to” motive for redundant posting is a deeply felt need “to reach out”, often mentioned in tension with a perceived elusiveness of connectedness.

Figure 6.

Typical recurrent memorial picture (source: Facebook grief group “Doliul: Chinul nostru cel de toate zilele”).

Figure 7.

Rare personal picture (source: Facebook grief group “Mame îndoliate” [Grieving Mothers]).

Three mature respondents post repetitively about loss, reflecting on their living to feel it. Living the loss all over again is living in the nearly vivid presence of the dead. Stepping out of the mourner’s psychic realm, the dead lingers out in the digital open, multiplying incessantly (Hartman 2012; Refslund-Christensen and Gotved 2015), connecting with whoever acknowledges her spreading presence. The focus is not on “the object” (Kasket’s (2019, 2020) “digital ghost”), but on “the subject”: the mourner’s unappeasable will to live to feel the loss. In Hartman’s words:

“In Reality 2.0, mourned objects become enigmas, rather than ghosts. I can never possess you, but if I can search for you indefinitely, you will always live in me as you live beyond me. Perhaps you will help me to never find you?”.(Hartman 2011, p. 460)

‘Digital death’ can be simultaneously acknowledged and prevented; eternally unfulfilled, hence, eternally conquerable. Losing ‘in loop’ comes with our digital humanness, and it may change our sense of loss for good: a loss that just won’t stay lost”.

5. Conclusions

This is not a thorough account of death across the Romanian internet. Instead, we focused on three distinct directions that emerged widely on Romanian Facebook and repeatedly in our informants’ spontaneous reflections. We used Schützian categories to interpret the three clusters of experience: 1. Within the realm of belief, users live by the logic of miracle; digital communication cannot change the system of relevance that offered the users the code for interpreting deadly events: “trampling death by death” applies across life-worlds; 2. In-between cultural worlds and realms, there is resistance, distrust, fragility, and ambivalence. Participants are less anchored in their traditions and simultaneously sceptical about digital change: “frameless death” also applies across lifeworlds; 3. Everyday digital reality (controllable) is more rewarding than standard reality (uncontrollable); synchronising death experiences across life-worlds is less stringent. “Multi-death”: digital and standard death obey different rules. They coexist in their own realm with a varying degree of conflict and intermittent points of contact (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Playground and cemetery merging together in Dăbuleni, Romania: a metaphor of “frameless death”. (source: Facebook Bogdan Berneanu).

Preliminary findings suggest that, in the proximity of death, co-presence is largely experienced as distressful yet trustful and stable, emphasising reciprocal responsibility, while the realm of tele-co-presence is malleable, exploratory, and devotional, emphasising affective interlocking. As an experience, “digital death” is more than the sum of its fragments: a self-emerging connective experience, connecting ever-multiplying death roles, scripts, functions, and avatars; a joint limitless flow of (self-)reflected socially productive experiences where subjective choice plays a crucial role.

As for the historico-cultural contingencies, institutional Orthodoxy retains authority over formal ceremonies, but existential orientations and motivational contexts are a labyrinth of conflicting realms with unstable provinces of meanings. Historical specificity sets predilections and typified combinations of motives for what Romanians do in the proximity of death and how they do it. Digital technologies notably modulate the “hows” and, less notably, the “whats”.

Funding

This research was funded by EU-CHANSE and UEFISCDI (code COFUND-CHANCE-DiDe CONTRACT No. 320/2022 Subprogram 3.2—Horizon 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to all of those with whom she has had the pleasure to discuss the ideas exposed in this essay, as well as to the participants who kindly agreed to be interviewed in spite of their emotional fragility. Johanna Sumiala and Dorthe Refslund Christensen have generously answered our numerous technical and non-technical questions with unfailing patience. I am also very grateful to the two anonymous reviewers who took the time to read and formulate highly insightful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this essay; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Note

| 1 | Porridge made of cornmeal and salty water, cheaper than bread, “eternally popular” in Romania. |

References

- Aghioritul, Sfântul Nicodim. 2003. Despre vrăjitorie [On Witchcraft]. Translated by Ion Diaconescu. Bucharest: Sofia. [Google Scholar]

- Andreesco, Joanna, and Mihaela Bacou. 2011. Mourir à l’ombre des Carpathes [Dying in the Shadow of the Carpathian Mountains]. Paris: Payot. [Google Scholar]

- Bănică, Mirel. 2014. Nevoia de Miracol. Fenomenul Pelerinajelor în România Contemporană [The Need for Miracles. The Pilgrimage Phenomenon in Contemporary Romania]. Iași: Polirom. [Google Scholar]

- Bănică, Mirel, and Vintilă Mihăilescu. 2017. Secularizarea, un decalaj religios al societății noastre? [Secularization—A religious gap in our society?]. In De ce este România altfel? [Why Is Romania Different?]. Edited by Vintilă Mihăliescu. Iași: Polirom, pp. 126–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett, Debra. 2015. Who Wants to Live Forever? Living, Dying and Grieving in Our Digital Society. Social Sciences 4: 1127–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Peter L. 1970. The Problem of Multiple Realities: Alfred Schutz and Robert Musil. In Phenomenology and Social Reality: Essays in Memory of Alfred Schutz. Edited by Maurice Natanson. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, pp. 213–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bregman, Lucy. 1973. Growing Older Together: Temporality, Mutuality, and Performance in the Thought of Alfred Schutz and Erik Erikson. The Journal of Religion 53: 195–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, Teresa. 2004. Transmission of Affect. Ithaca: Cornell UP. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Anne. 2020. The Body in the Emergence of Trust. Ethnopolitics 19: 209–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Archie. 2009. The Rise and Fall of Communism. New York: Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Candrea, Aurel. 1999. Folclorul medical comparat. Privire generală. Medicina magică [Comparative Medical Folklore. A General Look. Magical Medicine]. Iași: Polirom. First published 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Cerulo, Karen A. 1997. Reframing sociological concepts for a brave new (virtual?) world. Sociological Inquiry 67: 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clémént, Olivier. 1995. Corps de mort et de loire. Petite introduction à une théopoétique du corps [The Body of Death, the Body of Grace. Short Introduction to a Theopoetics of the Body]. Paris: Desclée de Brouwer. [Google Scholar]

- Clémént, Olivier. 2019. Transfiguring Time: Understanding Time in the Light of the Orthodox Tradition. Translated by Jeremy N. Ingpen. New York: New City Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cojocaru, Haralambie. 1949. Legislaţia canonică a Bisericii Ortodoxe faţă de superstiţie şi magie, vrăjitorie şi obscurantism [Canonical Legislation of the Orthodox Church concerning Superstition, Magic, Sorcery, and Obscurantism]. Studii Teologice [Theological Studies], Series II no 5-6 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, Charles H. 1956. The Two Major Works of Charles H. Cooley. Glencoe: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cornea, Ovidiu. 2023. Recensământ 2022. De ce este religia marea necunoscută, cu 15% dintre români nedeclarați [2022 Census. Why is religion the great unknown, with 15% of Romanians undeclared Christians]. Europa liberă [Free Europe]. January 8. Available online: https://romania.europalibera.org/a/religie-recensamant2022-romani-/32210549.html (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Couliano, Ioan Petru. 1992. The Tree of Gnosis. Gnostic Mythology from Early Christianity to Modern Nihilism. Translated by Hillary. S. Wiesner. New York: Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio, Antonio. 1999. The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Data Portal. 2023. Digital 2022: Romania. Available online: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-romania (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Davie, Grace. 2010. Thinking Broadly and Thinking Deeply: Two Examples of the Study of Religion in the Modern World. In Secularisation in the Christian World. Edited by Callum B. Brown and Michael Snape. Aldershot: Ashgate, pp. 219–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dertouzos, Michael. 1998. What Will Be: How the New World of Information Will Change Our Lives. San Francisco: Harper Edge. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, Mikhail. 2012. The Transformative Humanities. A Manifesto. London: Bloomsbury Academics. [Google Scholar]

- Evdokimov, Paul. 2000. Les Chretiens Orthodoxes [The Orthodox Christians]. Paris: Flammarion. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, Anna. 2010. After affect: Sympathy, synchrony, and mimetic communication. In The Affect Theory Reader. Edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth. Durham: Duke UP, pp. 186–205. [Google Scholar]

- Giddens, Anthony. 1990. The Consequences of Modernity. Stanford: Stanford UP. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman, Erving. 1963. Behavior in Public Places. New York: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Mark B. N. 2015. Feed-Forward: On the Future of Twenty-First-Century Media. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, Stephan. 2011. Reality 2.0: When loss is lost. Psychoanalytic Dialogues: The International Journal of Relational Perspectives 21: 468–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, Stephan. 2012. Cybermourning: Grief in flux, from object loss to collective immortality. Psychoanalytic Inquiry 32: 454–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervieu-Léger, Danielle. 2000. Religion as a Chain of Memory. Translated by Simon Lee. New Jersey: Rutgers UP. [Google Scholar]

- Ickes, William, Joanna Hutchison, and Debra Mashek. 2004. Closeness as Intersubjectivity: Social Absorption and Social Individuation. In Handbook of Closeness and Intimacy. Edited by Debra Mashek and Arthur Aron. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, pp. 357–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ihde, Don. 1990. Technology and the Lifeworld: From Garden to Earth. Bloomington: Indiana UP. [Google Scholar]

- Ihde, Don. 2010. Heidegger’s Technologies: Postphenomenological Perspectives. New York: Fordham UP. [Google Scholar]

- Immordino-Yang, Mary Helen, Andrea McColl, Hanna Damasio, and Antonio Damasio. 2009. Neural correlates of admiration and compassion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106: 8021–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptelinin, Victor. 2018. Technology and the Givens of Existence: Toward an Existential Inquiry Framework in HCI Research. Paper presented at 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, April 21–26; Paper 270. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kasket, Elaine. 2019. All the Ghosts in the Machine: Illusions of Immortality in the Digital Age. London: Robinson. [Google Scholar]

- Kasket, Elaine. 2020. Social Media and Digital Afterlife. In Digital Afterlife Death Matters in a Digital Age. Edited by Maggie Savin-Baden and Victoria Mason-Robie. Boca Raton: CRC Press, pp. 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Joohan. 2001. Phenomenology of digital-being. Human Studies 24: 87–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klass, Dennis. 2013. Sorrow and Solace: Neglected Areas in Bereavement Research. Death Studies 37: 597–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagerkvist, Amanda. 2015. The netlore of the infinite: Death (and beyond) in the digital memory ecology. New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia 21: 185–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagerkvist, Amanda. 2017a. Embodiments of Memory: Toward an Existential Approach to the Culture of Connectivity. In Memory Unbound: Tracing the Dynamics of Memory Studies. Edited by Lucy Bond, Stef Craps and Pieter Vermeulen. New York: Berghahn, pp. 173–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lagerkvist, Amanda. 2017b. Existential Media: Toward a Theorisation of Digital Throwness. New Media & Society 19: 96–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lagerkvist, Amanda, ed. 2019. Digital Existence: Ontology, Ethics and Transcendence in Digital Culture. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Larchet, Jean-Claude. 2001. Théologie de la maladie [The Theology of Illness]. Paris: Éditions du CERF. [Google Scholar]

- Larchet, Jean-Claude. 2002. Le Chrétien devant la maladie, la souffrance et la mort [The Christian confronting Illness, Suffering, and Death]. Paris: Éditions du CERF. [Google Scholar]

- Larchet, Jean-Claude. 2010. Une fin de vie paisible, sans douleur, sans honte… [A Peaceful Ending with no Pain or Shame]. Paris: Éditions du CERF. [Google Scholar]

- Lazurca, Marius. 2022. In Corpore. De la trupul păgân la corpul creștin în Antichitatea târzie [In Corpore. From the Pagan Body to Christian Corporeality]. Bucharest: Litera. [Google Scholar]

- Lemeni, Adrian. 2022. Tehnicizarea inumană a vieții [The Inhuman Technicalisation of Life]. Bucharest: Basilica. [Google Scholar]

- Lossky, Vladimir. 2017. Orthodox Dogmatic Theology: Creation, God’s Image in Man, & the Redeeming Work of the Trinity. Translated by Anthony P. Gythiel. New York: SVS Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lossky, Vladimir. 2022. The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church. Translated by Dion McLaren. Johnsonville: Crux Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luckmann, Thomas. 1970. On the Boundaries of the Social World. In Phenomenology and Social Reality. Essays in Memory of Alfred Schütz. Edited by Maurice Natanson. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, pp. 73–101. [Google Scholar]

- Lupton, Deborah. 2015. Digital Sociology. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Makrides, Vasilios N. 2012. Orthodox Christianity, Modernity and Postmodernity: Overview, Analysis and Assessment. Religion, State and Society 40: 248–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, Steve. 1997. Eudaemonic Eye: “Personal Imaging” and Wearable Computing as Result of Deconstructing HCI: Towards Greater Creativity and Self-Determination. Paper presented at the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Atlanta, Georgia, March 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, Steve. 2001. Cyborg. Digital Destiny and Human Possibility in the Age of the Wearable Computer. Toronto: Doubleday Canada. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, Jane Ribbens, Katie Woodthorpe, and Kathryn Almack. 2023. The Aftermath of Death in the Continuing Lives of the Living: Extending ‘Bereavement’ Paradigms through Family and Relational Perspectives. Sociology 57: 1356–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLuhan, Marshall. 1964. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. New York: McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, George Herbert. 1962. Mind, Self and Society: From the Standpoint of a Social Behaviorist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. First published 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Meyendorff, John. 2011. Living Tradition. New York: SVS Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Kaspar, Jonas T. Kaplan, Ryan Essex, Hanna Damasio, and Antonio Damasio. 2011. Seeing touch is correlated with content-specific activity in primary somatosensory cortex. Cerebral Cortex 21: 2113–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möllering, Guido. 2001. The Nature of Trust: From Georg Simmel to a Theory of Expectation. Interpretation and Suspension. Sociology 35: 403–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlhoff, Rainer. 2015. Affective resonance and social interaction. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 14: 1001–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natanson, Maurice, ed. 1970. Phenomenology and Social Reality. Essays in Memory of Alfred Schütz. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2011. Sacred and Secular. Religion and Politics Worldwide, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. [Google Scholar]

- Olteanu, Antoaneta. 1999. Școala de solomonie: Divinație şi vrăjitorie în context comparat [School of Sorcery: Divination and Witchcraft in Comparative Context]. Bucharest: Paideia. [Google Scholar]

- Pace Giannotta, Andrea. 2019. Digital world, lifeworld, and the phenomenology of corporeality. Azimuth: Philosophical Coordinates in Modern and Contemporary Age 14: 109–20. [Google Scholar]

- Parr, Hester, and Joyce Davidson. 2008. “Virtual Trust”: Online Emotional Intimacies in Mental Health Support. In Researching Trust and Health. Edited by Julie Brownlie, Alexandra Greene and Alexandra Howson. London: Routledge, pp. 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Patapievici, Horia-Roman. 2015. Partea nevăzută decide totul [The Unseen Part Decides Everything]. Bucharest: Humanitas. [Google Scholar]

- Pavelescu, Gheorghe. 1998. Magia la români [Magic and Romanians]. Bucharest: Minerva. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, John Durham. 2015. The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2018. Eastern and Western Europeans Differ on Importance of Religion, Views of Minorities, and Key Social Issues. October 29. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2018/10/29/eastern-and-western-europeans-differ-on-importance-of-religion-views-of-minorities-and-key-social-issues/ (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Pitsillides, Stacey, Mike Waller, and Duncan Fairfax. 2013. Digital Death: What Role Does Digital Information Play in the Way We Are (Re)membered? In Digital Identity and Social Media. Edited by Steven Warburton and Stylianos Hatzipanagos. Hershey: Information Science Reference, pp. 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Popovici, Iustin. 2003. Credința Ortodoxă și Viața în Hristos [Orthodox Faith and Life through Christ]. Galați: Buna Vestire. [Google Scholar]

- Preda, Radu. 2011. Ortodoxia și democrația postcomunistă. Cazul românesc [Orthodoxy and Post Communist Democracy. The Romanian Case]. In Religia în democrație. O dilemă a modernității [Religion in Democracy: A Dilemma of Modernity]. Edited by Camil Ungureanu. Iași: Polirom, pp. 326–56. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, Robert. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Recensământ. 2021. Recensământ—Rezultate definitive: Caracteristici demografice [Census—Definitive Results: Demographic CHARACTERISTICS]. Available online: https://www.recensamantromania.ro/rezultate-rpl-2021/rezultate-definitive-caracteristici-demografice/ (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Refslund-Christensen, Dorthe, and Stine Gotved. 2015. Online memorial culture: An introduction. New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia 21: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reveal Market Research. 2021. Studiu Reveal Marketing Research: Iubirea față de Dumnezeu, mai mult decât frica, îi determină pe românii creștin-ortodocsi să respecte obiceiurile creștinești [Reveal Marketing Research Study: Love of God Rather than Fear Linking to Respect for Orthodox Traditions]. Available online: https://reveal.ro/reveal-trends/studiu-reveal-marketing-research-iubirea-fata-de-dumnezeu-mai-mult-decat-frica-ii-determina-pe-romanii-crestin-ortodocsi-sa-respecte-obiceiurile-crestinesti/ (accessed on 29 August 2023).

- Rotar, Marius. 2013. History of Modern Cremation in Romania. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rotar, Marius. 2021. On civil funerals in contemporary Romania. Mortality 26: 131–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudometof, Victor. 2010. The Evolution of Greek Orthodoxy in the Context of the World Historical Globalisation. In Orthodox Christianity in 21st Century Greece. The Role of Religion in Culture, Ethnicity and Politics. Edited by Victor Roudometof and Vasilios N. Makrides. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Roussou, Eugenia. 2022. Orthodox Christianity, New Age Spirituality and Vernacular Religion. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Baden, Maggie. 2019. Postdigital Afterlife? Postdigital Science and Education 1: 303–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin-Baden, Maggie. 2022. Digital Afterlife and the Spiritual Realm. Boca Raton: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Baden, Maggie, and Victoria Mason-Robbie. 2020. Digital Afterlife. Death Matters in a Digital Age. Bona Raton: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scheff, Thomas J. 1990. Microsociology: Discourse, Emotion and Social Structure. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Scheff, Thomas J. 1997. Emotions, the Social Bond, and Human Reality: Part/Whole Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. [Google Scholar]

- Schuetze, Paul. 2021. From Affective Arrangements to Affective Milieus. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 611827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schütz, Alfred. 1941. Scheler’s Theory of Intersubjectivity and the General Thesis of the Alter Ego. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 2: 323–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, Alfred. 1945. On Multiple Realities. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 5: 533–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz, Alfred. 1967. The Phenomenology of the Social World. Translated by George Walsh, and Frederick Lehnert. Chicago: Northwestern UP. First published 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Schütz, Alfred. 1970a. On Phenomenology and Social Relations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schütz, Alfred. 1970b. Reflections on the Problem of Relevance. New Haven: Yale UP. [Google Scholar]

- Schütz, Alfred. 1970c. The Problem of Transcendental Intersubjectivity in Husserl. In Collected Papers III: Studies in Phenomenological Philosophy. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, pp. 51–84. [Google Scholar]

- Schütz, Alfred. 1976. Don Quixote and the Problem of Reality. In Collected Papers II: Studies in Social Theory. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, pp. 135–59. [Google Scholar]

- Schütz, Alfred. 1989. The Structures of the Life World. Translated by Richard M. Zaner, and David J. Parent. Evanston: Northwestern UP, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Schütz, Alfred, and Thomas Luckmann. 1973. The Structures of the Life World. Translated by Richard M. Zaner, and H. Tristram Engelhardt Jr.. Evanston: Northwestern UP, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sfântul Maslu [The Service of Holy Unction]. 2022. The Romanian Orthodox Episcopate of America. Grass Lake: Department of Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Simmel, Georg. 2004. The Philosophy of Money. 3rd enlarged edition. Edited by David Frisby. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Slaby, Jan. 2014. Emotions and the Extended Mind. In Collective Emotions. Edited by Mikko Salmela and Christian von Scheve. Oxford: Oxford UP, pp. 32–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sofka, Carla J., Allison Gibson, and Danielle R. Silberman. 2017. Digital Immortality or Digital Death? Contemplating digital end-of-life planning. In Postmortal Society. Towards a Sociology of Immortality. Edited by Michael Hviid Jacobsen. London: Routledge, pp. 173–96. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, Sheldon, Jeff Greenberg, and Thomas Pyszczynski. 2015. The Worm at the Core. On the Role of Death in Life. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Stage, Carsten, and Tina Thode Hougaard. 2018. The Language of Illness and Death on Social Media. Bingley: Emerald Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, Irina. 2013. Getting in touch with the saints in contemporary Romania. Balkanskaya Kartina Mira Sub Specie Pyati Chelovecheskih Shuvstv. Balkanskie Chteniya 12: 99–109. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, Irina. 2018. Communist Impact on Religion in Romania. Ethnologia Balkanica: Journal for Southeast European Anthropology 21: 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, Irina. 2022. Cultul Sfântului Nectarie în România. Apariţie, evoluţie şi caracteristici [The Cult of Saint Nektarios in Romania. Introduction, Evolution and Characteristics]. In România Socială. Feţe ale schimbării. Procese, probleme, situaţii sociale [Social Romania: Aspects of Change: Processes, Problems, Social Situations]. Edited by Ilie Bădescu and Cristi Pantelimon. Bucharest: Editura Academiei Române, pp. 328–62. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, Irina, and Eric Venbrux. 2011. Ritual Multiplication: On Lived Religion in Bucharest. In Jaarboek Voor Liturgieonderzoek. Groningen: Instituut Voor Christelijk Cultureel Erfgoed, pp. 139–67. [Google Scholar]

- Stan, Lavinia, and Lucian Turcescu. 2007. Religion and Politics in Post-Communist Romania. New York: Oxford UP. [Google Scholar]

- Stăniloaie, Dumitru. 1969. Some Characteristics of Orthodoxy. Sobornost 9: 627–29. [Google Scholar]

- Stăniloaie, Dumitru. 1971. În problema intercomuniunii [Concerning the Intercommunion]. Ortodoxia [Orthodoxy] 2: 561–84. [Google Scholar]

- Stenger, Nicole. 1991. Mind is a Leaking Rainbow. In Cyberspace: First Steps. Edited by Michael Benedikt. Cambridge: The MIT Press, pp. 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Stiller, James, and Robin I. M. Dunbar. 2007. Perspective-taking and memory capacity predict social network size. Social Networks 19: 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, Paul. 2021. Digital Souls. A Philosophy of Online Death. London: Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, Harry Stack. 1953. The Interpersonal Theory of Psychiatry. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Toplean, Adela. 2015. To resist or to embrace social death? Photographs of couples on Romanian gravestones. Contemporary Social Science 10: 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toplean, Adela. 2018. The Impact of Secularization and Spiritualization on Death Meanings and Practices among Contemporary Romanians. New Europe College Yearbook. Bucharest. Available online: https://nec.ro/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/ADELA_TOPLEAN-1.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Toplean, Adela. 2020. Sistemul morții [The System of Death]. In Treizeci. Anii de după [Thirty. The Years After]. Edited by Cristian Pătrășconiu. Timișoara: Editura Universității de Vest, pp. 337–41. [Google Scholar]

- Toplean, Adela. 2021. Understanding Moral Solidarity. Journal of Urban Anthropology 1(IX): 145–68. [Google Scholar]

- Toplean, Adela. 2023. Global Digital Death and Glocal Dying: Theoretical Challenges and Possible Research Directions. Glocalism: Journal of Culture, Politics and Innovation 1: 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Turkle, Sherry. 1995. Life on the Screen. Identity in the Age of the Internet. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Turkle, Sherry. 2012. Alone Together. Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Turkle, Sherry. 2015. Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age. New York: Penguin Press. [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk, Bessel. 2014. The Body Keeps the Score. Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, Gloria Maria. 2020. Alfred Schutz’s Life-World and Intersubjectivity. Open Journal of Social Sciences 8: 417–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdery, Katherine. 1996. What Was Socialism, and What Comes Next? Princeton: Princeton UP. [Google Scholar]

- Verdery, Katherine. 1999. The Political Lives of the Dead Bodies. Reburial and Postsocialist Change. New York: Columbia UP. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, Tony. 1995. Facing Death without Tradition. In Contemporary Issues in the Sociology of Death, Dying and Disposal. Edited by Glennys Howarth and Peter Jupp. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 193–204. [Google Scholar]

- Ware, Kallistos. 1988. St Maximos of Kapsokalyvia and Fourteenth-Century Athonite Hesychasm. In Kathegetria. Essays Presented to Joan Hussey for her 80th Birthday. Edited by Julian Chrysostomides. Camberley: Porphyrogenitus, pp. 409–30. [Google Scholar]

- Weigert, Andrew J. 1975. Alfred Schütz on a Theory of Motivation. The Pacific Sociological Review 18: 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertheim, Margaret. 1999. The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace. A History of Space from Dante to the Internet. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Woodthorpe, Kate. 2017. Family and funerals: Taking a relational perspective. Death Studies 41: 592–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yannars, Christos. 2011. The Meaning of Reality: Essays on Existence and Communion, Eros and History. Los Angeles: Sebastian Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Shanyang. 2003. Toward a taxonomy of copresence. Presence Teleoperators and Virtual Environments 12: 445–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Shanyang. 2004. Consociated contemporaries as an emergent realm of the lifeworld: Extending Schutz’s phenomenological analysis to cyberspace. Human Studies 27: 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Shanyang. 2006. The internet and the transformation of the reality of everyday life: Toward a new analytic stance of sociology. Sociological Inquiry 76: 458–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Shanyang. 2007. Internet and the lifeworld: Updating Schutz’s theory of mutual knowledge. Information Technology & People 20: 140–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Shanyang. 2015. Constitution of Mutual Knowledge in Telecopresence: Updating Schultz’s Phenomenological Theory of the Lifeworld. Journal of Creative Communications 10: 105–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).