Providing Consumer Credit to Low-Income Populations in Brazil—The Case of Complexo da Penha

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Approach—Financial Inclusion, Financialization and Consumer Credit

“Consumer credit can enhance household welfare by allowing for consumption smoothing over time, but there are many reasons why growth in consumer credit may, at times, be a concern. For example, research has shown that consumers are frequently ignorant about many of the features of the products they use; they do not always make good decisions; and credit providers often exploit the tendency for consumers to make mistakes”

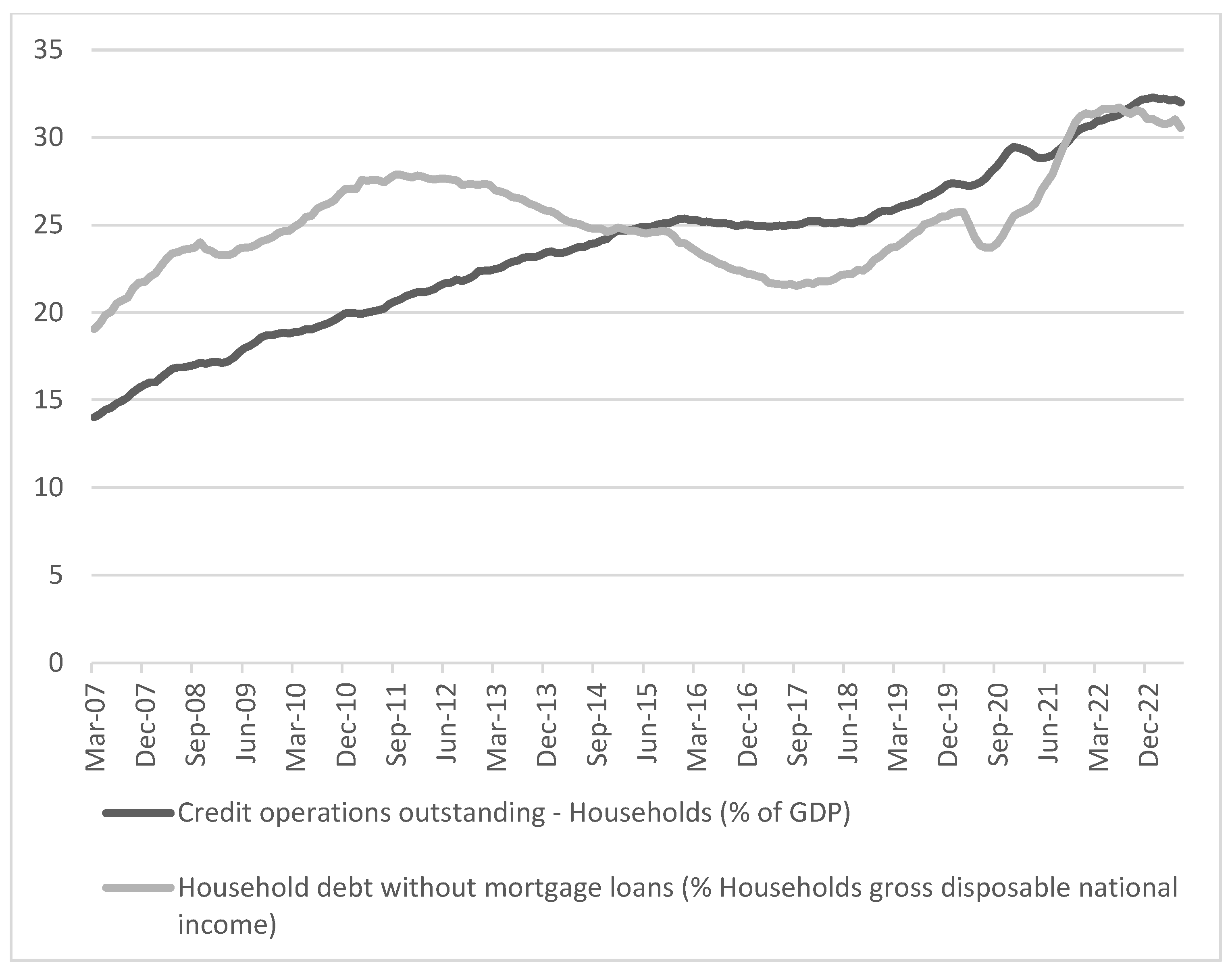

3. The Brazilian Context

4. Methodology

5. Case Study of Complexo da Penha

5.1. Why Participants Access Mainstream Credit Financing: Multipurpose Demand

“We miss it (having a credit card) in this sense, especially when we go to the supermarket. Even medicine, sometimes medicine is needed in the house and we, damn, at that moment we don’t have the money and we see that a card could be useful at that moment”.(Bernardo)

“Credit cards are good, because you don’t use cash. When the person, like, has a family it’s even better because you have to wait ‘till the end of the month to get your payment, and sometimes your family might be needing something. Something like that, then the person goes and uses the card. It makes things easier”.(Fabio)

“I think it’s necessary (to have a credit card) because when emergencies happen sometimes we don’t have quick access to the money. Like, health issues, sometimes you have an emergency, you need to buy medicine”.(Henrique)

“This month, my mother lent her card to another person to buy some clothes, to go to the doctor and the person didn’t pay … then we always end up having to bear the losses”.(Cris)

“Oh, it was my aunt. She wanted to buy something for her house and asked for the card, it wasn’t even mine, it was my mother’s, but I’m an authorized user—that’s how you say it, right? Then we were not able to use the card for a while, the card was blocked because of her. Then we decided never to lend it again, because you see, she was family and she did it to us, you know. But then thank God, after a great deal of effort, she paid, and then the problem was solved”.(Amanda)

“I lent (the credit card) to my friend for her to buy sneakers. And it’s happened already that, like, I arrive at a store and I get there with Cris. I managed to make a card and she didn’t. Then the goddam woman said ‘Oh, you can put her as an extra’. Then I was like ‘Oh yeah, a friend, you can!’. I was the owner, then my bill arrives along with hers—it didn’t go to her place. Let’s say, she got the card but it was in my name. Everything came to me”.(Carolina)

“What I owe is just on the credit card. Not much, just 18 thousand and something5 (laughs) (…) I equipped a house for a relative, man, put everything on my card! Anything you can imagine, I put it all! That card of mine from Casas Bahia didn’t have a limit, man. It had a limit, but it was 10 thousand reais, just the one of Casas Bahia (…)”(Leandro)

“My sister asked me to get a VCR for her at the time, and she didn’t pay. And it was an insurance company that I worked for and we couldn’t have a ‘bad’ name, couldn’t have credit restrictions. And the company, I don’t remember which one it was at the time, if it was Ponto Frio … it was a company like that. They started calling my work, then they spoke directly to my department manager, right. And then she scolded me, called me into the room and I didn’t know, it was a shock. My sister was pregnant and everything … then I went to her house to know what was happening and all … then she said ‘I haven’t paid for a couple of months’ and I was like ‘you could’ve warned me, I would’ve paid! They called my work and I don’t know what’s gonna happen’. I went there, I solved the problem, I paid it, and a month later I got fired. And we believe that it was because of that”.(Hugo)

5.2. Access to Mainstream Credit Financing: Various Products, Changing Cultural Frameworks

“(Interviewer) So nowadays do you have any kind of debt?— I do (…) mine was the ATM that released it. For that card I had it released a thousand and something, but when I checked it was almost 4 thousand that I had to pay. 48 instalments of 75 reais. It was to put things in the house. Because sometimes, where he (Ian) was working, he would be paid on the 5th working day but sometimes it was the 20th day and he had not received anything yet. Then I got desperate and went there and got it”.(Ingrid)

“he was like, he said that it was available and there were several values and I could click on them. I just clicked and the money went to my account. In the next month they started to charge (…)—and why did you choose Caixa?—because it was easy, it was. I should not have done it because I didn’t even really need the money. But you know how it is, there you go”.(Maria)

“I’ve seen my mother talking like that, getting home all happy and ‘oh, I got a loan’. I asked her ‘how much is the loan?’ Then she said ‘R$150’ (…) She got it from C&A (retailer)”.(Carolina)

“My first bank account was at Itaú and I have a huge debt with Itaú. I opened it because people suggested. Formerly it was Unibanco, I was 16, then when I went there to open, as I was underage I did not get a checking account, I got a salary account. So when it turned to a checking account the [overdraft] limit showed up, which deceives people, right. I thought it was money that was mine … then they started deducting it from my salary, and I was getting no salary”.(Carolina)

“The lady, when I went there to get my payment, she said ‘oh darling, you have the right to get a consignado.’ But I thought I didn’t have to pay for that! (…) Because I didn’t know this consignado thing. When she said ‘consignado’ I said ‘oh, I think old people have the right to it’, I’m already 80 years old, right. Then I thought I had the right … I got it and now I have to pay R$212 per month”.(Geruza)

5.3. When Participants Access Mainstream Credit Financing: Transient FI and Ever-Present Informal Lending Practices

“When the person wants to fight in life, has a kid, is unemployed and needs that money to buy diapers, milk for the children, he has to go the extra mile, can’t be picky. He’s going to sell candy in the bus, he’ll do anything, but he’ll get his money”.(Danilo)

“I went to my mom for help. I’d get things from her. Or got small freelancing gigs, would do chores for neighbors. I used to carry sand, take out rubbish, things like that”.(Fabio)

“I’ve been there already. But then I … in the age of informality, I worked like, cooking and at the time I was also teaching. I even made more money like that than working in a registered way. But I think what we see a lot in the community itself, every week there is a little stall on the corner, there’s not even enough space anymore … it’s a hair salon, it’s a food stall, that’s the way it is. Unemployment is the monster of our time, but what I have seen is this, it is informal service. It’s the way out. (…) I was already like this, I stayed 4 years without work and in those 4 years I made food, snacks, cakes—because my grandmother worked with confectionery—and teaching”.(Hugo)

“(Interviewer)—Now with the two of you unemployed, what are you doing to manage this situation at home?(Janete)—I iron clothes, once a month, it’s 50 reais that the girl pays me. Then those 50 reais I’m going to spend on food. This daughter of mine helps me a lot, she shops for herself and then she does it for me too, you know. So in terms of food, she pays for it. The bad thing is, right now I ran out of gas, and I’m shaken … it’s bad the way it is. If I have to buy some clothes, a hair dye then I can’t do it. And life goes on like this …”

“And then ‘oh, that guy lends money’. I was thinking that he was a good guy, when I realized he was seriously involved (with drug trafficking), my brother! Hadn’t I paid, you’d see! I doubt I’d be alive! (…) At that time I couldn’t go to the bank because I already had debts from the past, then I couldn’t … if I went to the bank, the bank would’ve rejected it. I looked for several people and they didn’t have it (money to lend), and I had to go to the loan shark. I had no choice. The only option I had at that moment was the loan shark!”(Leonardo)

“My daughter took some money from loan sharks, she was counting on some money she was about to get in order to pay him. But she didn’t receive it and the shark said that he was gonna send a thug to my house. He was going to get everything we had and we have nothing! The only thing we have is a tv in the living room. They wouldn’t want the couch because it’s old. The chair is second-hand. Girl, I was desperate and I had to get that 2 grand I told you about, from this friend of mine, to pay the shark. And to this day I haven’t been able to pay my friend”.(Geruza)

“I was unemployed as well, as it was now, and I got R$50 at the time. (…) the person who lent me the money, she drank a lot. She had everything to be happy about, but she drank a lot. The husband replaced her for a younger girl, and she drank to the point she would lay on the couch and only wake up the next day. And I went there to pay her and she was in that state, and a man there took the money and then she went to my door to collect her money. And on that day I went there to pay her, I wasn’t even paying the full amount, I went there to pay the interest, because I got R$50 and had to pay R$15, it was 30%. I even thanked God that I didn’t take all the money that day. But I had a hard time with her, she kept sending me messages, saying that she was gonna send the boys [drug dealers] to my door to charge me. There was even an argument. I don’t get involved with sharks no more!”(Janete)

“Let’s just say that he (Carolina’s father) walked with many people calling them friends. Then when he needed it he had to look for this loan shark … my sister had to leave her job to pay for what my father owed”.(Carolina)

“It happens in many cases, at least from what we hear from people, you know. They threaten, they want to take everything, they even threaten to kill … depending on the moneylender. And many of them, they are mostly policemen too, right. And usually those who make threats like this are the police, to intimidate more the person. Then they come with that violence, to say that they’ll kill”.(Ian)

“Oh, I’m remembering, people who got very indebted, but he is an addict too, poor guy. He got so lost that he had to sell his house, his own house. That is sad … a backward move”.(Bia)

“There, people put a certain amount of money every month, let’s suppose 20 people. Every month people put in R$100, every month. But the money doesn’t stay in the caixinha. Caixinha is a figure of speech. This money goes to the bank. And these people have to make that money circulate, lending it to acquaintances or relatives at low interest rates. Low, but higher than the bank, so let’s assume 20%. Then you lend R$100 and the person pays R$120. And at the end of the year this money is shared, as if it was a 13th salary”.(Fernando)

“Caixinha is good! The day someone gets to do it … its good! Any type of caixinha—the yields are very handy! You get good interest. My mom was always involved in it, she used to work at the Oswaldo Cruz Institute and they have it there. All the staff borrowed money, then by the end of the year the caixinha tripled, I think! Very juicy stuff. You could make a Christmas table, buy clothes, buy whatever you needed. If you hear of one (caixinha), darling, let me know!”(Janete)

“—(Paula) It’s a way of having extra money at the end of the year.—(Patricia) It’s a form of saving, right—you do it throughout the year, you pay a certain amount that is called ‘quota’, you pay it during 11, 12 months and then you receive it back with interest, it comes with interest. It’s the interest that came from loans and activities that happened throughout the year”.

“Some people buy like, for example, they buy an iron, then they make a draw (…) then the person who is responsible [for the caixinha] promotes some activities—hers is like this, all members have to find people to lend to. For example, let’s say, I’m a member, so I have to find people to lend to, to generate interest”(Paula)

“We have one (caixinha) here in the community. And not just here, there are many others like this”.(Danilo)

“(Ian)—there is a lot of that (caixinhas in poor communities).(Ingrid)—I don’t have access, but many people do”.

“The caixinha is more (used) because there is no bureaucracy. Because in the bank they’ll want a lot of documents, proof of income and everything. In the caixinha usually the value is low as well”.(Leonardo)

“Because it’s faster, you don’t have to go to the bank, you don’t need anything. And it’s a little money that you can afford to pay anytime”.(Fernando)

“Sometimes the caixinha also runs out of money, you know. From all the lending! Only when it gets to December, you can’t borrow no more. November and December. Because this money that is out there in the street has to return all the way to the caixinha in December, so we share this money”.(Fernando)

“That’s like a loan shark (…) My boss took the caixinha out of there, because it was a very serious problem. He said that this couldn’t exist within a company, so it’s not legal”.(Bia)

“The caixinha is the same as the loan shark. The difference is that if you are an investor of the caixinha you borrow money, pay interest and at the end of the year you receive interest as well”.(Leonardo)

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Federal Law number 10.820/2003. |

| 2 | The Central Bank Resolution number 3110, dated of 31 July 2003, set the rules for branchless banking in the country; Central Bank Resolution number 3211, dated 30 June 2004, regulated the so-called simplified current accounts; Central Bank Resolution n. 3.518/2007 determined that financial institutions had to offer a package of free services called “essential services” to clients. |

| 3 | In that study, defined as clients earning up to twice the amount of the minimum wage. |

| 4 | We use the term “subsistence consumption” to refer to a minimum level of consumption required to sustain life, which is usually determined by the poverty line. |

| 5 | At the time of the interview, 18 thousand Brazilian reais were equivalent to approximately 5.4 thousand US Dollars. |

| 6 | It is worth remembering that charging exploitative interest is considered a crime against the popular economy in Brazi (law n. 1521/51, Article 4). |

References

- Abramo, Pedro. 2003. A teoria econômica da favela: Quatro notas sobre a localização residencial dos pobres e o mercado imobiliário informal. In A Cidade da informalidade: O desafio das cidades latino-americanas. Edited by Pedro Abramo. Rio de Janeiro: Sette Letras. [Google Scholar]

- Amos, Amanda, Susan Wiltshire, Yvonne Bostock, Sally Haw, and Ann McNeill. 2004. You can’t go without a fag … you need it for your hash—A qualitative exploration of smoking, cannabis and young people. Addiction 99: 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ATISG. 2010. Innovative Financial Inclusion: Principles and Report on Innovative Financial Inclusion from the Access Through Innovation Sub-Group of the G20 Financial Inclusion 21 Experts Group. G20 Financial Inclusion Experts Group. Available online: https://www.gpfi.org/sites/gpfi/files/documents/Principles%20and%20Report%20on%20Innovative%20Financial%20Inclusion_0.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Atkinson, Adele, and Flore-Anne Messy. 2013. Promoting Financial Inclusion through Financial Education: OECD/INFE Evidence, Policies and Practice. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- Barbotin, Maria. 2014. “Pia! Só quer ser o que não é, e mora na favela”—práticas de consume e construção de identidades entre indivíduos de classes populares. Ph.D. thesis, Federal University of Paraíba, João Pessoa, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, Carla, and Everardo Rocha. 2007. Lógica de consumo em um grupo das camadas populares: Uma visão antropológica de significados culturais. Paper presented at XXXI Anpad, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, September 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Brusky, Bonnie, and João Fortuna. 2002. Entendendo a demanda para as microfinanças no Brasil: Um estudo qualitativo em duas cidades; Rio de Janeiro: BNDES.

- Castilhos, Rodrigo. 2007. Subindo o morro: Consumo, posição social e distinção entre famílias de classes populares. Master’s dissertation, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, Daiane, Karla Mendes, and Luiza Xavier. 2014. Crédito: Caixa eletrônico esconde armadilha. O Globo. October 16. Available online: https://oglobo.globo.com/economia/defesa-do-consumidor/credito-caixa-eletronico-esconde-armadilha-14249377 (accessed on 11 December 2023).

- Demirgüç-Kunt, Asli, Leora Klapper, and Dorothe Singer. 2017. Financial Inclusion and Inclusive Growth: A Review of Recent Empirical Evidence. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 8040. Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, Asli, Leora Klapper, Dorothe Singer, and Sanyia Ansar. 2022. The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Evens, Hilary, and Jenny Houssart. 2007. Paired interviews in mathematics education. Proceedings of the British Society for Research into Learning Mathematics 27: 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Fligstein, Neil, and Adam Goldstein. 2012. The Emergence of a Finance Culture in American Households 1989–2007. Socio-Economic Review 13: 575–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentil, Denise, and Miguel Bruno. 2021. Endividamento das famílias e expropriação salarial no Brasil: O motor da acumulação financeira na pandemia e além. Brasília: Fonacate. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, Felipe. 2015. Where are the consumers? ‘Real households’ and the financialization of consumption. Cultural Studies 29: 781–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, Brooke. 2010. Pop Finance: Investment Clubs and the New Investor Populism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Highet, Gill. 2003. Cannabis and smoking research: Interviewing young people in self-selected friendship pairs. Health Education Research 18: 108–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karacimen, Elif. 2015. Consumer credit as an aspect of everyday life of workers in developing countries: Evidence from Turkey. Review of Radical Political Economics 48: 252–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lameiras, Maria, and Marcos Hecksher. 2023. Indicadores mensais do mercado de trabalho—março de 2023; Brasília: IPEA.

- Langley, Paul. 2008. Financialization and the consumer credit boom. Competition & Change 12: 133–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lavinas, Lena, Eliane Araújo, and Miguel Bruno. 2017. Brasil: Vanguarda da financeirização entre os emergentes. UFRJ Discussion Paper, 32. Rio de Janeiro: UFRJ. [Google Scholar]

- Lipovetsky, Gilles. 2007. A felicidade paradoxal: Um ensaio sobre a sociedade do hiperconsumo. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. [Google Scholar]

- Mader, Philip. 2013. Explaining and quantifiying the extractive success of financial systems: Microfinance and the financialisation of poverty. Ekonomska istraživanja—Economic Research Special Issue 26: 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mader, Philip. 2018. Contesting financial inclusion. Development and Change 49: 461–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattos, Marina. 2007. O consumidor de baixa renda e suas relações com as marcas no processo de decisão de compras de refrigerantes e sabão em pó. Master’s dissertation, PUC-Rio, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Mattoso, Cecília, and Angela Rocha. 2005. Significados associados às estratégias para solução de problemas financeiros dos consumidores pobres. Paper presented at XXIX Enanpad, Brasília, Brazil, September 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Finance. 2023a. Bancos e Governo Federal lançam Programa Desenrola Brasil para Dívidas Bancárias. Available online: https://www.gov.br/economia/pt-br/orgaos/orgaos-colegiados/conselho-de-recursos-do-sistema-financeiro-nacional/acesso-a-informacao/noticias/2023/bancos-e-governo-federal-lancam-programa-desenrola-brasil-para-dividas-bancarias (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Ministry of Finance. 2023b. Ministro Fernando Haddad se reúne nesta terça com Enviada Especial da ONU para Inclusão Financeira. Available online: https://www.gov.br/fazenda/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/2023/junho/ministro-fernando-haddad-se-reune-nesta-terca-6-6-com-enviada-especial-da-onu-para-inclusao-financeira (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Muller, Lúcia. 2014. Negotiating debts and gifts: Financialization policies and the economic experiences of low-income social groups in Brazil. Virtual Brazilian Anthropology 11: 191–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, Soares, Horígenes Fontes, Lessi Pinheiro, and Marcelo Inácio Ferreira Ferraz. 2021. Brasil da financeirização: Do consumo familiar à cooptação da assistência social. Sociologias 23: 356–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogami, Vitor, and Mario Pacagnan. 2011. Consumo da base da pirâmide: Uma análise bibliométrica do estado da arte na produção acadêmica no Brasil. Paper presented at XXXV Anpad, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, September 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, Michael. 2002. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Paz, Mayara. 2023. Senado Aprova Projeto que Regulamenta Desenrola e Limita juros Rotativos do Cartão de Crédito. CNN. Available online: https://www.cnnbrasil.com.br/economia/senado-aprova-projeto-que-regulamenta-desenrola-e-limita-juros-rotativos-do-cartao-de-credito-texto-vai-a-sancao/ (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Pellandini-Simányi, Léna. 2020. The financialization of everyday life. In The Routledge Handbook of Critical Finance Studies. Edited by Borch Christian and Robert Wosnitzer. London: Routledge, pp. 278–99. [Google Scholar]

- Rocha, Angela, and Jorge Silva. 2008. Inclusão social e marketing na base da pirâmide: Uma agenda de pesquisa. RAE-Eletrônica 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santanna, Danielle. 2020. The History of Consumer Credit in Brazil: From the Developmentalist Era to Lula. International Journal of Political Economy 49: 203–21. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/08911916.2020.1824736 (accessed on 21 September 2023). [CrossRef]

- Sarti, Cynthia. 2011. A família como espelho: Um estudo sobre a moral dos pobres, 7th ed. São Paulo: Cortez. [Google Scholar]

- Schymura, Luiz. 2022. Alto Endividamento das Famílias, com Destaque para mais Pobres, é Desafio para Próximo Governo. November 10 Blog do IBRE. Available online: https://blogdoibre.fgv.br/posts/alto-endividamento-das-familias-com-destaque-para-mais-pobres-e-desafio-para-proximo-governo (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Serasa. 2023. Mapa da Inadimplência e Negociação de Dívidas no Brasil. Available online: https://www.serasa.com.br/limpa-nome-online/blog/mapa-da-inadimplencia-e-renogociacao-de-dividas-no-brasil/ (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Soederberg, Susanne. 2014. Debtfare States and the Poverty Industry: Money, Discipline and the Surplus Population. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. 2014. Financial Inclusion—Global Financial Development Report. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/446a24f6-0fd2-5d76-a94a-ce1fbfc6648d/content (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- The World Bank. 2021. DataBank—Global Financial Inclusion. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/global-financial-inclusion (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Zhuang, Juzhong, Herath Gunatilake, Yoko Niimi, Muhammad Ehsan Khan, Yi Jiang, Rana Hasan, Niny Khor, Anneli Lagman Martin, Pamela Bracey, and Biao Huang. 2009. Financial Sector Development, Economic Growth, and Poverty Reduction: A Literature Review. Asian Development Bank Economics Working Paper Series, 173; Manila: Asian Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

| Participant | Gender | Age | Occupation | Education | Marital Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amanda | F | 32 | Cleaner | Secondary, incomplete | Single |

| Bia | F | 36 | Housewife | Secondary, complete | Married |

| Bernardo | M | 37 | Security guard | Secondary, complete | Married |

| Cris | F | 20 | Telemarketing operator | Secondary, complete | Single |

| Carolina | F | 24 | Student | Secondary, complete | Single |

| Danilo | M | 34 | Unemployed | Primary, incomplete | Single |

| Esther | F | 67 | Retiree | Primary, complete | Married |

| Fabio | M | 50 | Freelancer | Primary, complete | Married |

| Geruza | F | 80 | Retiree | Primary, incomplete | Widow |

| Gisele | F | 56 | Nursing assistant | Secondary, complete | Divorced |

| Henrique | M | 52 | Retiree | Undergraduate, complete | Single |

| Hugo | M | 49 | Freelancer | Secondary, complete | Single |

| Ingrid | F | 35 | Sales | Secondary, complete | Married |

| Ian | M | 34 | Unemployed | Primary, complete | Married |

| João | M | 35 | Student | Secondary, complete | Single |

| Janete | F | 61 | Unemployed | Primary, incomplete | Single |

| Leandro | M | 55 | Freelancer | Primary, complete | Single |

| Leonardo | M | 41 | Micro entrepreneur | Secondary, complete | Married |

| Maria | F | 41 | Freelancer | Secondary, complete | Divorced |

| Mariana | F | 30 | Housewife | Primary, incomplete | Single |

| Nestor | M | 63 | Community leader | Undergraduate, complete | Married |

| Pedro | M | 35 | Child protection counsellor | Undergraduate, incomplete | Single |

| Patrícia | F | 40 | Nursing assistant | Undergraduate, complete | Single |

| Paula | F | 55 | Retiree | Secondary, complete | Divorced |

| Paloma | F | 43 | Business assistant | Undergraduate, complete | Married |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santanna, D. Providing Consumer Credit to Low-Income Populations in Brazil—The Case of Complexo da Penha. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12120691

Santanna D. Providing Consumer Credit to Low-Income Populations in Brazil—The Case of Complexo da Penha. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(12):691. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12120691

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantanna, Danielle. 2023. "Providing Consumer Credit to Low-Income Populations in Brazil—The Case of Complexo da Penha" Social Sciences 12, no. 12: 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12120691

APA StyleSantanna, D. (2023). Providing Consumer Credit to Low-Income Populations in Brazil—The Case of Complexo da Penha. Social Sciences, 12(12), 691. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12120691