The ‘Arab Clans’ Discourse: Narrating Racialization, Kinship, and Crime in the German Media

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Narrative Context, Racism, and the Media in Critical Discourse Studies

3. The Immigration Context of Arabs and ‘Arab Clans’ in Germany

4. Data and Method

5. Findings

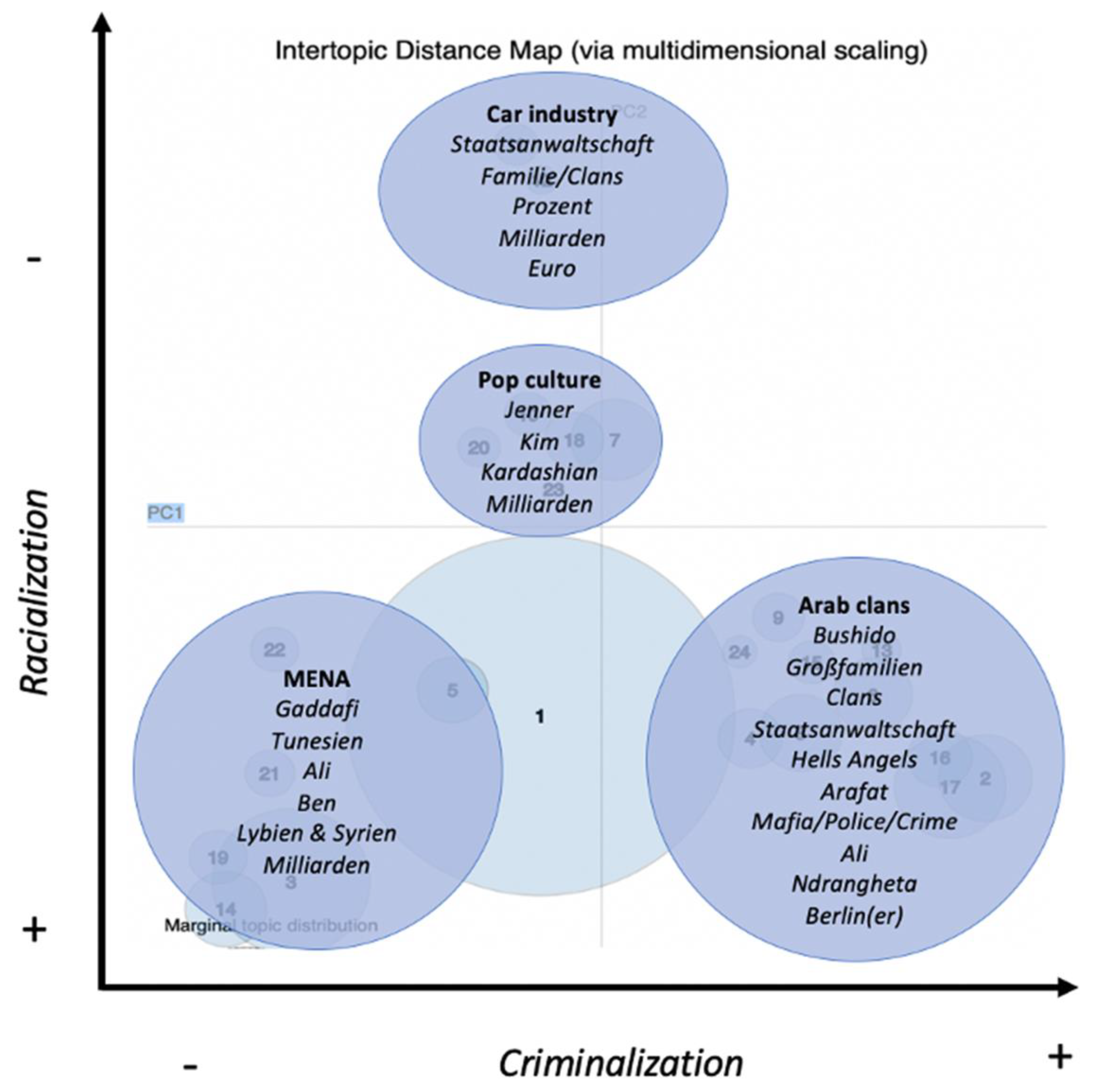

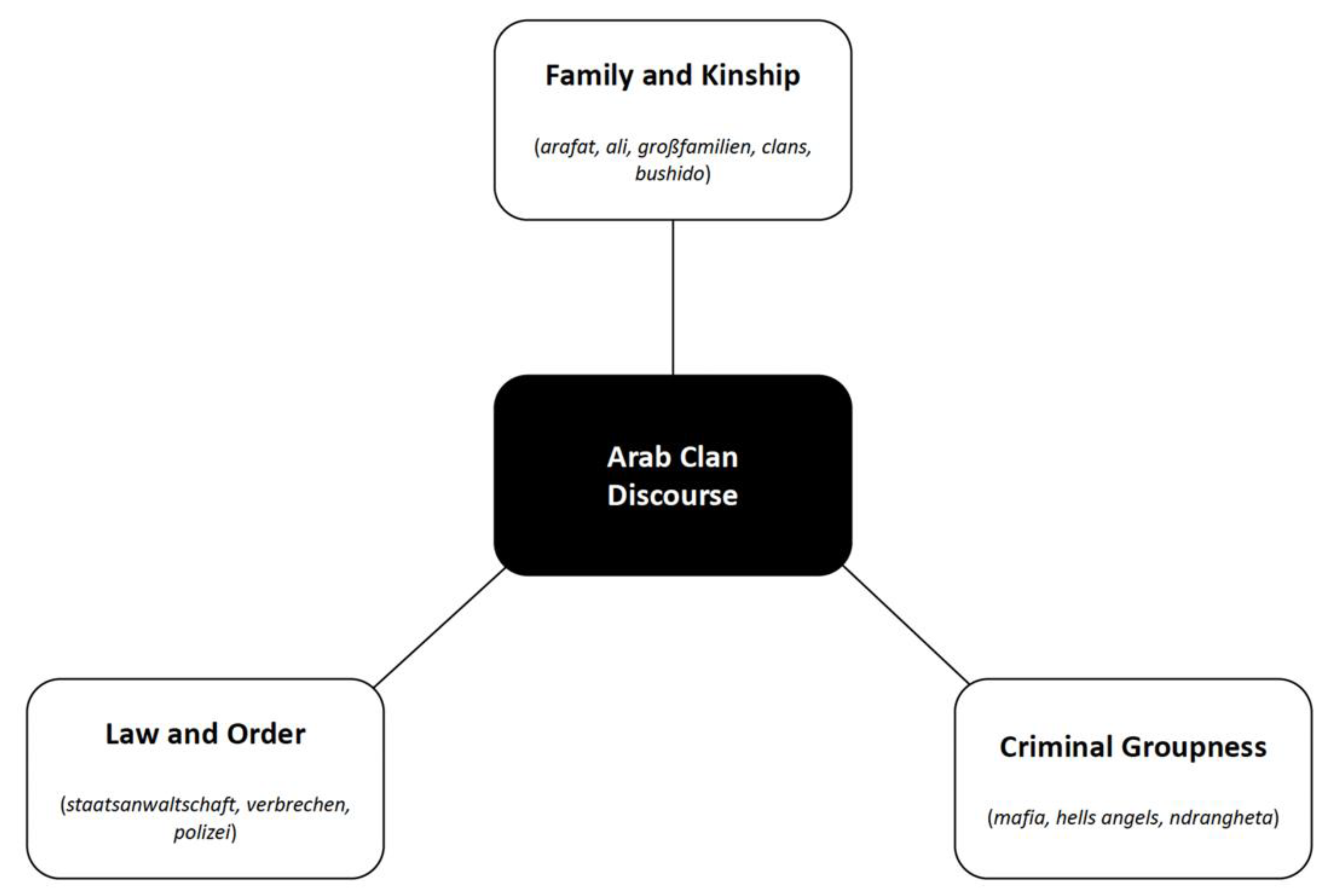

5.1. Level 1: Topic Modeling

5.2. Level 2: Discursive Strategies Analysis

5.2.1. Argumentation Strategy I: Arab Clan Immigration out of Control

After his deportation to Lebanon, a leading member of the Lebanese Miri clan returned to Bremen. This was confirmed by the State Ministry of the Interior on Wednesday. Entry and residence were refused. Apparently, entry took place illegally. Criminal investigations on this matter have been initiated.

Miri applied for asylum as a 13-year-old in 1986. His [present] application can therefore be treated as a follow-up application. Because follow-up applications are more complicated to decide upon, refused asylum seekers often use them to delay their deportation … In one instance he claims to be born in 1980, in another in 1982, in yet another in 1984, sometimes in Beirut (Lebanon), sometimes in Turkish Mardin.

[This is] (a) horror scenario for Christoph de Vries (44) of the CDU, the expert from the Federal Ministry for the Interior: “We have to ask ourselves whether we want to continue to finance an asylum system where criminals ignore bans on entry and residence, enter the country illegally, and, on top of everything else, are able to apply for an asylum that protects them from deportation until decided”.: “We must limit significantly the possibility of duplicate applications for asylum”. Support was voiced by the opposition. The Secretary General for the FDP, Linda Teuteberg (38) to Bild: “The law has to be enforced, and the proceedings must be sped up.

5.2.2. Argumentation Strategy II: Arab Clans as Enclaves

Many citizens perceive a creeping takeover of neighborhoods by groups with migration background and the organized criminality of clans.

Asking around the streets of Neukölln, the Abou-Chakers appear as a mix between ordering power, raiding party, and family enterprise. They sometimes arrived in their BMWs to settle disputes, as though they were sheriffs. There is rumor of “protection money”. And that one can borrow money, under horrendous conditions. It’ll hurt if you can’t pay it back. State’s Attorney Kamstra says, “Some clan members have tried to pervert or buy off testimonies.

Generally speaking, an overview of the criminal history of some clans demonstrates that female family members prefer to steal, while male crimes touch on all areas of the criminal code, including drug and property offenses, verbal abuse, threats, robbery, blackmail, grievous bodily harm, sexual misconduct, pimping, all the way to murder. Children grow up largely unsupervised in these criminal structures. The state has no chance of reaching these families.

5.2.3. Argumentation Strategy III: Policing Arab Clans

Young man partly scalped: trial against 13 accused in Essen (DPA/LNW): The victim was partly scalped and critically wounded by stabbing. Eight months after the brutal crime, the trial against 13 members of a Syrian extended family has begun at the Essen District Court.

… but then the state did not intervene when they [‘Arab clans’] built their criminal structures. The raids are meant to send an additional signal to the Lebanese community. ‘I make trouble so as to compel youth and especially women to consider whether it would be smarter to take a different path,’ says Reul Sunday morning in Essen. In Germany, one can ‘be economically successful without committing crimes’. The operations are also meant to demonstrate strength outwardly, because many citizens have lost confidence and doubt the authority of the state. And because the police face aggressions.

Andreas Geisel (SPD), State Minister for the Interior of Berlin, where clan criminality is a major issue as well, welcomed that move. Consequently, the new directives will be followed in Berlin, and the “pressure on organized crime” will be kept up, Geisel announced on Thursday. “Where possible, deportations will be considered”.

5.3. Level 3: Narrative Genre Analysis

5.3.1. Stage 1: The Selectively Remembered Past of Media Interventions into the Discourse about ‘Arab Clans’

5.3.2. Stage 2: Portrayals of Present-Day Catastrophe and ‘Moral Panic’ in Media Interventions into the Discourse about ‘Arab Clans’

5.3.3. Stage 3: The Promise of Ethnonational Rebirth following ‘Moral Panics’ in Media Interventions into the Discourse about ‘Arab Clans’

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The asterisk indicates the inclusion of an unlimited number of additional characters to the search word root of the search term. Hence, derivatives (e.g., ‘clans’) or composite terms (e.g., ‘clancriminality’) are included in the search. |

| 2 | The most salient terms of each topic in the ‘Arab clans’ cluster were used for this search. Topic 2: kriminalität (‘criminality’), berlin, clans, kriminelle (‘criminals’), organisierte (‘organised’); Topic 4: miri, abschiebung (‘deportation’), ibrahim, libanon (‘Lebanon’), asylantrag (‘application for asylum’); Topic 6: prozess (‘trial’), angeklagten (‘accused’), gericht (‘court’); Topic 9: bushido, arafat, rapper, yasser, geschäftspartner (‘business partner’); Topic 16: reul, nrw, clankriminalität (‘clan criminality’), cdu; Topic 17: polizei (‘police’), festgenommen (‘arrested’), verletzt (‘harmed’), beamten (‘officers’), streit (‘argument’). The entire topic model output and the interactive intertopic distance map are available in https://box.hu-berlin.de/d/5ecf6659eb934118ae4f/, accessed on 22 January 2023 (Password: clancrim2023). |

| 3 | Translation: Car industry: staatsanwaltschaft = state attorney, milliarden = billions, MENA: tunesien = Tunisia, Lybien = Libya, Syrien = Syria, regierung = government, präsident = president, Arab clans: großfamilien = extended families, polizei = police, verbrechen = crimes |

References

- Abbott, H. Porter. 2008. The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative. West Nyack: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, Jeffrey, and Philip Smith. 2001. The Strong Program in Cultural Theory: Elements of a Structural Hermeneutics. In Handbook of Sociological Theory. Edited by Jonathan Turner. Berlin: Springer Sciences + Business Media, pp. 135–50. [Google Scholar]

- Atshan, Sa’ed, and Katharina Galor. 2020. The Moral Triangle: Germans, Israelis, Palestinians. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Paul, Costas Gabrielatos, Majid KhosraviNik, Michał Krzyżanowski, Tony McEnery, and Ruth Wodak. 2008. A Useful Methodological Synergy? Combining Critical Discourse Analysis and Corpus Linguistics to Examine Discourses of Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the UK Press. Discourse & Society 19: 273–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bittner, Mark, Celal Cakar, Florian Kain, Peter Tiede, and Astrid Sievert. 2019. Fall Miri—Asylantrag Trotz Einreisesperre. BILD, November 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bleich, Erik, and A. Maurits van der Veen. 2021. Covering Muslims: American Newspapers in Comparative Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bleich, Erik, Hannah Stonebraker, Hasher Nisar, and Rana Abdelhamid. 2015. Media Portrayals of Minorities: Muslims in British Newspaper Headlines, 2001–2012. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41: 942–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleich, Erik, James P. Callison, Georgia Grace Edwards, Mia Fichman, Erin Hoynes, Razan Jabari, and A. Maurits van der Veen. 2018. The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly: A Corpus Linguistics Analysis of Us Newspaper Coverage of Latinx, 1996–2016. Journalism 22: 1522–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boettner, Johannes, and Helmuth Schweitzer. 2020. Der Name Als Stigma: Kollateralschäden Im “Krieg Gegen Die Clans”. Sozial Extra 44: 349–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breazu, Petre, and David Machin. 2019. Racism toward the Roma through the Affordances of Facebook: Bonding, Laughter and Spite. Discourse & Society 30: 376–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brücker, Herbert, Elisabeth Liebau, Agnese Romiti, and Ehsan Vallizadeh. 2014. Arbeitsmarktintegration von Migranten in Deutschland: Anerkannte Abschlüsse und Deutschkenntnisse Lohnen sich. Nuremberg: IAB-Kurzbericht. [Google Scholar]

- Bundeskriminalamt. 2019. Organisierte Kriminalität, Bundeslagebild 2018. Wiesbaden: Bundeskriminalamt. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Jennifer E. 2015. Islamophobia, Muslimophobia or Racism? Parliamentary Discourses on Islam and Muslims in Debates on the Minaret Ban in Switzerland. Discourse & Society 26: 562–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Jason, Christopher Manning, and Jeffrey Heer. 2012. Termite: Visualization Techniques for Assessing Textual Topic Models. Paper presented at International Working Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces, Capri Island, Italy, May 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Stanley. 2011. Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and Rockers/Stanley Cohen, 1st publ. in Routledge Classics ed. Abingdon: Routledge. First published 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Dahinden, Janine. 2016. A Plea for the ‘De-Migranticization’ of Research on Migration and Integration. Ethnic and Racial Studies 39: 2207–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Teso-Craviotto, Marisol. 2009. Racism and Xenophobia in Immigrants’ Discourse: The Case of Ar-gentines in Spain. Discourse & Society 20: 571–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienstbühl, Dorothee. 2020. Clankriminalität: Phänomen-Ausmaß-Bekämpfung. Heidelberg: C. F. Müller Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Fairclough, Norman, Guiseppina Cortese, and Patrizia Ardizzone, eds. 2007. Discourse and Contemporary Social Change, 1st New ed. Bern: Peter Lang AG, Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Farris, Emily M., and Heather Silber Mohamed. 2018. Picturing Immigration: How the Media Criminalizes Immigrants. Politics, Groups, and Identities 6: 814–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltes, Thomas, and Felix Rauls. 2020. Clankriminalität “Und Die” “German Angst: Rechtspolitische Und Kriminologische Anmerkungen Zur Beschäftigung Mit Sogenannter” Clankriminalität. Sozial Extra 44: 372–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forchtner, Bernhard. 2021. Introducing ‘Narrative in Critical Discourse Studies’. Critical Discourse Studies 18: 304–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forchtner, Bernhard, and Özgür Özvatan. 2022. De/Legitimising Europe through the Performance of Crises: The Far-Right Alternative for Germany on ‘Climate Hysteria’ and ‘Corona Hysteria’. Journal of Language and Politics 21: 208–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroutan, Naika. 2019. Die Postmigrantische Gesellschaft: Ein Versprechen Der Pluralen Demokratie. Bielefeld: Transcript. [Google Scholar]

- Frigelj, Kristian. 2019. Bei uns gilt das Gesetz des Staates. Welt Online, January 14. [Google Scholar]

- Frye, Northrop. 1957. Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gavriely-Nuri, Dalia. 2017. Cultural Approach to Cda (Ccda): From Theory to Practice. London: Routledge, pp. 120–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ghadban, Ralph. 2016. Clan-Kriminalität: Besondere Ausprägung Der Organisierten Kriminalität. Deutsches Polizeiblatt 34: 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- Göke, Konrad, and Burkhard Uhlenbroich. 2019. Ibrahim Miri Nach Abschiebung wieder in Deutschland. BILD, November 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Stuart. 1978. Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State, and Law and Order, 2nd ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hamann, Ulrike, and Gökce Yurdakul. 2018. The Transformative Forces of Migration: Refugees and the Re-Configuration of Migration Societies. Social Inclusion 6: 110–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heisig, Kirsten. 2010. Angst ist ein schlechter Ratgeber. Der Spiegel, July 19, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Jaraba, Mahmoud. 2021. Arabische Großfamilien und die ‘Clankriminalität,’ Informations-Plattform für Journalistinnen und Journalisten zu den Themen Flucht, Migration und Diskriminierung. Available online: https://mediendienst-integration.de/artikel/arabische-grossfamilien-und-die-clankriminalitaet.html (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Karim, Karim H. 2000. Islamic Peril: Media and Global Violence. Montreal and New York: Black Rose Books. [Google Scholar]

- KhosraviNik, Majid. 2010. The Representation of Refugees, Asylum Seekers and Immigrants in British News-papers: A Critical Discourse Analysis. Journal of Language and Politics 9: 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korteweg, Anna, and Gökce Yurdakul. 2014. The Headscarf Debates: Conflicts of National Belonging. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, Michèle, Graziella Moraes Silva, Jessica S. Welburn, Joshua Guetzkow, Nissim Mizrachi, Hanna Herzog, and Elisa Reis. 2016. Getting Respect: Responding to Stigma and Discrimination in the United States, Brazil, and Israel. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Morey, Peter. 2011. Framing Muslims: Stereotyping and Representation after 9/11. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press. [Google Scholar]

- Musharbash, Yassin. 2013. Bushido. Brüder im Geiste. Die Zeit, June 20, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Laura K. 2020. Computational Grounded Theory: A Methodological Framework. Sociological Methods & Research 49: 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özvatan, Özgür. 2019. The Great Secession. Ethno-National Rebirth and the Politics of Turkish-German Belonging. Social Inclusion 8: 285–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Partington, Alan. 2003. The Linguistics of Political Argument: The Spin-Doctor and the Wolf-Pack at the White House. Routledge Advances in Corpus Linguistics. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Poole, Elizabeth, and John E. Richardson. 2006. Muslims and the News Media. London: Tauris. [Google Scholar]

- Reisigl, Martin. 2017. The Discourse-Historical Approach. In The Routledge Handbook of Critical Discourse Studies. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Reisigl, Martin, and Ruth Wodak. 2001. Discourse and Discrimination: Rhetorics of Racism and Anti-Semitism, 1st publ. ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Reisigl, Martin, and Ruth Wodak. 2009. The Discourse-Historical Approach (Dha). In Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. Edited by Ruth Wodak and Michael Meyer. London and Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Ltd., pp. 87–121. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, John E. 2004. (Mis)Representing Islam: The Racism and Rhetoric of British Broadsheet Newspapers. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde, Patrick, Dorothee Dienstbühl, and Sonja Labryga. 2019. Hysterie oder reale Bedrohung? Eine Kriminologische Einordnung des Phänomens Clankriminalität in Deutschland. Kriminalistik 73: 275–81. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, Amir. 2007. Media, Racism and Islamophobia: The Representation of Islam and Muslims in the Media. Sociology Compass 1: 443–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, Edward W. 1979. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- Sigal, Leon. 1986. Who? Sources Make the News. In Reading the News. Edited by Robert Manoff and Michael Schudson. New York: Pantheon Books, pp. 9–37. [Google Scholar]

- Somers, Margaret. 1994. The Narrative Constitution of Identity: A Relational and Network Approach. Theory and Society 23: 605–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty, ed. 2008. Can the Subaltern Speak?: Postkolonialität Und Subalterne Artikulation. Wien: Turia + Kant. [Google Scholar]

- Statistisches Bundesamt. 2021. Bevölkerung Und Erwerbstätigkeit. Ausländische Bevölkerung, Ergebnisse Des Ausländerzentralregisters 2020. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrück, Peer. 2015. Wider die Radikalisierung unserer Gesellschaft! Die Zeit, December 7, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, Peter. 2000. Racism in the News: A Critical Discourse Analysis of News Reporting in Two Australian Newspapers. Discourse & Society 11: 7–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, Teun A. 1991. Racism and the Press. Critical Studies in Racism and Migration. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, Theo. 2007. Legitimation in Discourse and Communication. Discourse & Communication 1: 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welt Online. 2019a. Führendes Mitglied des Miri-Clans wieder in Bremen. Welt Online, October 30. [Google Scholar]

- Welt Online. 2019b. Junger Mann teilskalpiert: Prozess gegen 13 Angeklagte. Welt Online, January 22. [Google Scholar]

- Welt Online. 2019c. Kampf gegen Clan-Kriminalität bleibt im Fokus der Ermittler. Welt Online, July 11. [Google Scholar]

- White, Hayden V. 1973. Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth Century Europe, 8th print. ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak, Ruth. 2015. The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak, Ruth, and Bernd Matouschek. 1993. ‘We Are Dealing with People Whose Origins One Can Clearly Tell Just by Looking’: Critical Discourse Analysis and the Study of Neo-Racism in Contemporary Austria. Discourse & Society 4: 225–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurdakul, Gökce. 2009. From Guest Workers into Muslims. The Transformation of Turkish Immigrant Associations in Germany. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Yurdakul, Gökce, and Anna Korteweg. 2021. Boundary Regimes and the Gendered Racialized Production of Muslim Masculinities: Cases from Canada and Germany. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 19: 39–54. [Google Scholar]

| Media Source | Political Leaning | Number of Articles | Database |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bild | Right (tabloid) | 1534 | NexisUni |

| Die Zeit | Center-left | 1620 | NexisUni |

| Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ) | Center-left | 7849 | Factiva |

| Die Tageszeitung (taz) | Left | 2063 | NexisUni |

| Die Welt | Center-right | 7402 | NexisUni |

| Stern | Center-left | 445 | NexisUni |

| Der Spiegel | Center-left | 2480 | NexisUni |

| Focus | Center-right | 500 | NexisUni |

| Total | 23,893 |

| Strategy | Objective | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Nomination | Naming of protagonists: actors, objects, phenomena, events, and processes | Crime/criminal, (Ibrahim) Miri, Bushido, (Arafat) Abou-Chaker, extended family (“Großfamilie”), Lebanese and Arab |

| Predication | Features of naming: realized by evaluative, stereotypical attributions of positive/negative traits or by references to them | Out of 167 predications, not a single feature of naming decoupled from organized crime, criminality, violence, sexual violence, (clan) brutality, fraud, robbery |

| Argumentation | Justification of features: arguments employed (supposed) to persuade the addressee(s) of the validity, truthfulness, and accuracy of the claim | Migration (n = 34): Arab clans undermine the German immigration and asylum system |

| Law and order (n = 49): Arab clans undermine German law and order | ||

| Organized crime (n = 25): Arab clans are defined as large families in which “group” crime is organized | ||

| Gendered clan socialization (n = 13): Arab clans socialize their members into archaic gender roles (i.e., archaic masculinity) | ||

| Clan brutality (n = 26): Arab clans form “groups” in which brutality against Others is legitimatized | ||

| Parallel social order (n = 22): Arab clans create a parallel social order beyond German law and order | ||

| Perspectivation | Strategies of distancing and/or involvement of the speaker’s position | The voices of authors, scientists, experts, and intellectuals are mostly absent (n = 2) The protagonists/subjects of the ‘Arab clan’ discourse are silent/silenced (n = 4) The primary discursive agents in media reports are state (security) and political authorities (n = 49) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Özvatan, Ö.; Neuhauser, B.; Yurdakul, G. The ‘Arab Clans’ Discourse: Narrating Racialization, Kinship, and Crime in the German Media. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12020104

Özvatan Ö, Neuhauser B, Yurdakul G. The ‘Arab Clans’ Discourse: Narrating Racialization, Kinship, and Crime in the German Media. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(2):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12020104

Chicago/Turabian StyleÖzvatan, Özgür, Bastian Neuhauser, and Gökçe Yurdakul. 2023. "The ‘Arab Clans’ Discourse: Narrating Racialization, Kinship, and Crime in the German Media" Social Sciences 12, no. 2: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12020104

APA StyleÖzvatan, Ö., Neuhauser, B., & Yurdakul, G. (2023). The ‘Arab Clans’ Discourse: Narrating Racialization, Kinship, and Crime in the German Media. Social Sciences, 12(2), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12020104