1. Introduction

In recent decades, Spanish society has experienced unprecedented social change (

González and Requena 2008), affecting numerous aspects of the social reality that are concentrated in various spheres, such as demographics, politics, the educational system and the family. Both the social structure and social institutions have intensely undergone a metamorphosis in a short period of time (

Becerril and Gerardo 2015). The family has not been exempt from these transformations and has centrally experienced changes in all senses, from its definition to its own functions and configurations.

If we focus our interest on the changes produced in the family environment, we quickly notice how new types of families are established and consolidated (

Becerril 2004) that entail an alteration of the parameters with which this institution was understood (

Valdivia 2008). The interest in studying the implications of these changes has been growing over time from a sociological perspective (

Sánchez and Bote 2009). From this point of view, within the transformations that have taken place in the family sphere in recent decades, two of them especially stand out: The change in the perception of marital termination and the legalization of same-sex marriage. On the one hand, marriage and divorce are intertwined in the planning of the trajectory of the love life of each of the members of the couple, whereas on the other, through the legalization of same-sex marriage, it is confirmed that heterosexuality is no longer the only condition for romantic and sexual expression (

Palacio 2009). These changes are precisely those that pique the interest of this investigation.

Marital termination and its evolution in Spain has been changing considerably. It has gone through various stages that range from a negative and stigmatizing vision to understanding it as a solution to an unsatisfactory, shared life project. The change in the perception of this reality has been reflected, in a certain way, in the changes that have occurred in the legal field (

Becerril 2008). In this sense, the introduction of Law 15/2005 of 8 July stands out, through which both the civil code and the law of civil procedure in matters of separation and divorce have been modified. The main change lies in the greater ease of access to divorce, both from a bureaucratic and temporary point of view.

The legalization of same-sex marriage in Spain occurred at a time of progressive recognition of this type of union in Europe (

Festy 2006,

2008). The process of approving homosexual unions in the European context began during the 1990s, taking shape differently in each country. The first to legalize this type of marriage were the Netherlands and Belgium, while Spain was the third in this process. In addition, it should be noted that in the Nordic countries, so-called registered partnerships were already introduced in the early 1990s (Norway 1993, Sweden 1995). In this sense, they were not called marriage but had the same rights and responsibilities. Indeed, the Spanish law is much older than that of other European countries, such as Sweden (2009), France (2013), England (2014), Italy (2016) or Finland (2017). In other countries, such as the United States, each state has adopted different approaches, some of them, such as Massachusetts and Connecticut, have led the way in recognizing this type of marriage or civil union, while the more conservative states have hesitated to promote this kind of equality, until June 26 2016: the Supreme Court of the United States decided that the prohibition of same-sex marriage violated the fourteenth amendment.

In Spain, these unions are equal to those formed by marriages of people of the opposite sex, while in other countries they are only included as de facto unions. In this sense, it can be affirmed that the law promoted in Spain stands as a global pioneer, being the first to recognize same-sex marriage through the civil code reform, and not through the approval of a new juridical figure (

Martín 2016). Prior to the legalization of same-sex marriage, many autonomous communities (AC from now on) were pioneers in recognizing, in different aspects of civil family law, people who were registered as couples in their registries. Specifically in the period from 1998 to 2005, twelve of the seventeen existing autonomous communities implemented the de facto partnership laws that included homosexual unions. These laws responded to two demands that had merged: Those of cohabiting couples seeking equality in rights and duties; and those of homosexual couples, seeking legal and social recognition (

Cortina and Cabré 2010).

Regarding the analysis and study of same-sex couples, there is currently a theoretical and empirical body of work in our country on the evolution and characteristics of marriages (

Capote and Nieto 2018;

Cortina 2016), but regarding the divorce of same-sex couples, and research at a national and community level, these analyses have been practically non-existent. However, in the international arena, we can find various studies focused on the dissolution of this type of couple (

Goldberg and Allen 2013;

Rothblum et al. 2018). This was more recently highlighted by the study carried out by

Kolk and Andersson (

2020) that analyzed the tendencies related to the creation of unions and divorces in same-sex marriages in Sweden between 1995 and 2012.

Thus, this research delves into the social reality of same-sex couple breakups in Spain, attempting to answer the following questions: When and why do divorces occur? What types of divorces occur? What is child custody like? To accomplish this, an overview and evolution of these marriages is provided; secondly, the state of the matter related to marriages and their dissolutions is shown; thirdly, the implemented research methods and techniques are exposed; fourthly, the main quantitative and qualitative results are shown and finally the main conclusions are drawn.

1.1. An Overview of the Evolution of Same-Sex Marriage in Spain

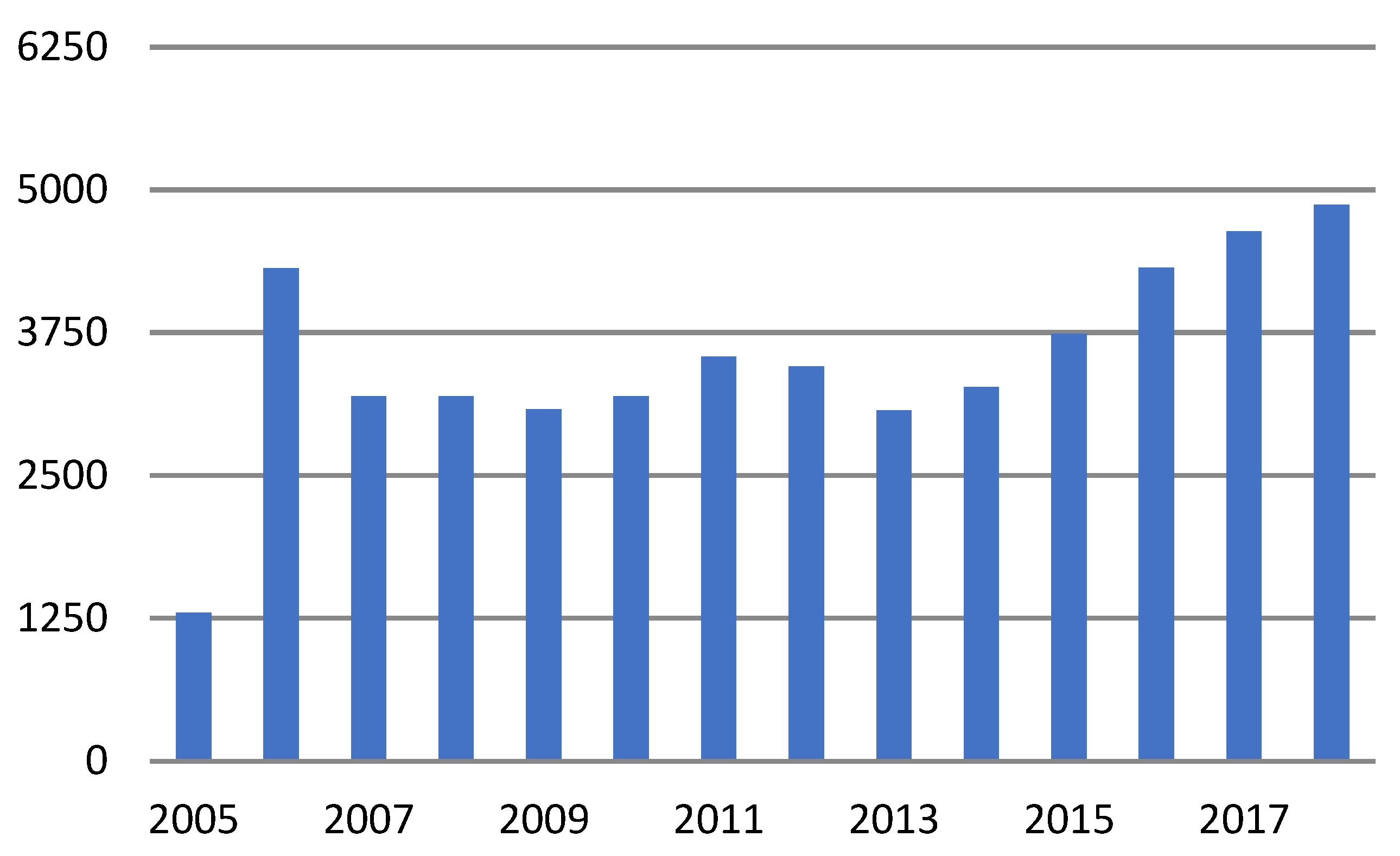

The first step to be able to approach the analysis of divorce and its characterization requires an outline of the evolution of same-sex marriage. The data indicates that the absolute number of this type of marriage has remained relatively stable (

Figure 1) since the highest number of marriages took place in 2006 (4313). Only from 2016, has this figure been surpassed (4320) and continues to grow until the latest data series available (4870 in 2018).

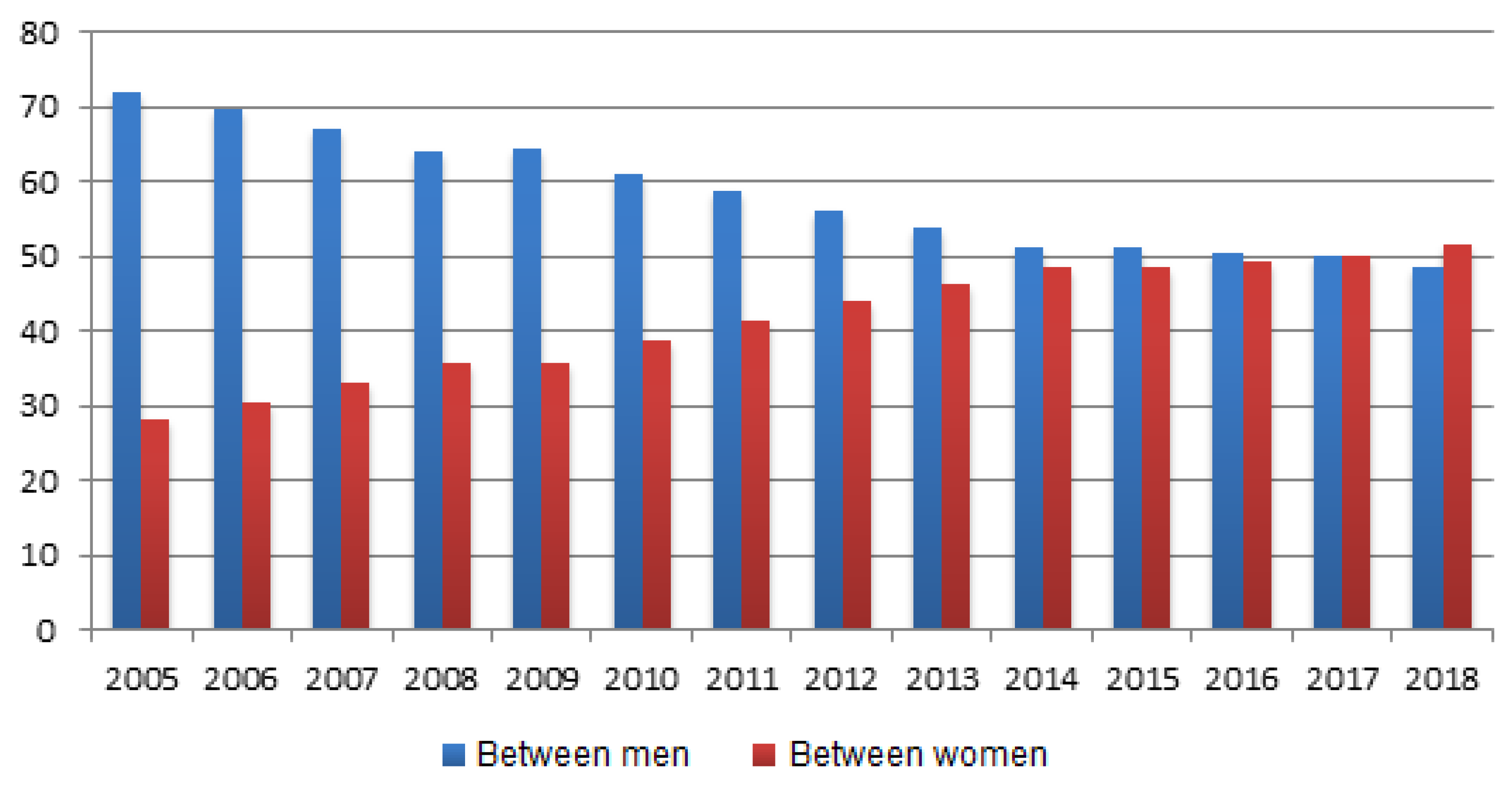

Moreover, the distribution of same-sex marriages according to their composition shows opposite trends between the group of men and women (see

Figure 2).

In marriages between two men, a high value is recorded at the beginning of legalization (2005), which practically triples the number of marriages between women. However, over the years, two different trends have been detected: The number of marriages between men has stagnated while those between women have increased. Thus, 2017 appears to be the time when the greatest similarity between both groups has occurred, with marriages between women (51.6%) outnumbering those between men (48.4%) in 2018.

It is noteworthy that the marriages between women, although not registered as a high percentage in the beginning, have been increasing progressively over the last few years, even surpassing those between men. This could be in relation to the analysis by

Kolk and Andersson (

2020) regarding the matter in Sweden, where they detected that the creation of unions between women rapidly increased during the studied period, while the tendencies related to the unions between men increased less so. Furthermore, this is something that has occurred in other countries around Europe.

In the case of Spain, this lower initial percentage of marriages between women could be explained by two factors: Firstly, by the increased economic and social vulnerability experienced by couples comprising women compared to those comprising men (

Gimeno 2006); and secondly, by the possible patriarchal and masculine character of the matrimonial institution (

Platero 2007).

This evolution coincides with the analyses of other investigations developed in European countries (

Banens 2010;

Kolk and Andersson 2020) that describe how during the first and second years of marriage, after the implementation of the law, there was a large number of marriage ceremonies that thereafter experienced a slight drop, followed by a slight rise and finally, a period of stabilization. Similarly to Spain’s situation (

Capote and Nieto 2018), it is explained that this is common due to the accumulation of same-sex couples who had a stable relationship but who had not been able to marry due to the lack of legalization.

1.2. Research on the Social Reality of Same-Sex Couples

First of all, regarding de facto unions,

Meil (

2001,

2003) devoted specific attention to homosexual people. Among their conclusions, they highlighted that these unions are more frequent between men and that the ages and nationalities of these couples are more heterogeneous than among heterosexual people.

Secondly, from a sociodemographic perspective, the high concentration of homosexual couples in urban areas stands out, with a lower average age than heterosexual couples and without significant differences in age and educational level (

Cortina and Cabré 2010;

Esteve et al. 2009). In addition, a predominance of the egalitarian model in relationships is observed (

Cortina 2016). This characterization is confirmed in more recent research (

Capote and Nieto 2018) that analyzes various aspects in depth, such as the evolution of homosexual marriages, their geographical distribution and the profiles of the members of this type of couple.

Thirdly, from the field of law, there are several issues that have been of interest to researchers. It highlights the importance of social movements for the recognition of civil rights, such as the legalization of same-sex marriage in Spain (

Calvo 2010b). Furthermore, the legal evolution of the Spanish marriage system is addressed from 1978 to the appearance of homosexual marriage (

Fernández 2006) and the comparison of the legal realities of homosexual couples in Europe (

Martín 2016). Lastly, the study of the institution of marriage after the legalization of same-sex marriage stands out (

Gimeno and Barrientos 2009), and the legalization of same-sex marriage has even been analyzed in the Spanish press from the perspective of framing (

Ramos and Díaz 2019).

Finally, regarding the marital rupture of same-sex couples, a traditional follow-up deficit is detected from a sociological perspective, although some recent research stands out. First of all, a study that focused on the degree of consensus or dissent existing in divorces of marriages composed of people of the same sex (

Becerril and Jiménez 2016) concludes the existence of an upward trend in the termination of this type of marriage and a greater existence of consensus in divorces than in heterosexual marriages. Secondly, an analysis of the influence on the divorce process is carried out, regarding variables, such as ownership and number of children, the nationality of the spouses, the gross domestic product, among other factors (

Jiménez-Cabello et al. 2021), all concluding that there are decisive variables that trigger the marital breakdown.

At the international level, the investigative coverage of this type of couple has been much broader, unlike what is observed in Spain, and receiving greater attention and scientific monitoring. The analyses carried out by

Blumstein and Schwartz (

1983) and

Kurdek (

1991,

1992,

1998) highlight how couples made up of people of the same sex have a higher rate of breakups than heterosexual couples.

Andersson et al. (

2006) verified how the duration of bonds between people of the same sex was shorter than in heterosexual couples. Specifically, female couples are twice as likely to break up as male couples. A fundamental aspect of the termination of these marriages is, above all, that a low level of conflict is detected in the dissolutions (

Goldberg and Allen 2013). As a consequence of this, it is stated that in the event of a breakup with sons and daughters present, the most widely granted type of custody is the shared custody (

Gartrell et al. 2011).

Focusing the attention on child custody, studies show, for example, that attitudes about paternity amongst men are less positive than those about maternity amongst women (

Biblarz and Savci 2010), therefore it appears relevant to give a special mention to the reality that having and raising a child could be especially problematic for couples comprising two men. Furthermore, except in the case of adoption, and regardless of how same-sex families are formed, only one of the members of the couple is the biological parent, which could bring the couple to negotiate the kinship with the child (

Berkowitz and Marsiglio 2007). In fact, one of the first representational studies about the association between children and divorce in same-sex couples found a positive relationship between having children together and divorce in couples comprising men, whereas in couples comprising women, there was a lesser probability of divorce (

Wiik et al. 2014).

More recently, a study in Vermont found that same-sex male couples stay together longer than lesbian couples, with the latter being twice as likely to break up as male couples (

Rothblum et al. 2018). This research also paid attention to items, such as the duration of the relationship and educational or economic level.

2. Methods, Data Collection and Analysis Techniques

Triangulation is the methodological strategy used in this research process, with the aim of carrying out an analytical multi-focus approach that offers a deeper and richer “verstehen” of the analyzed social reality (

Tashakkori and Teddlie 2003;

Pole 2009).

Triangulation will also be used as a quality control instrument in this study to achieve a greater guarantee in the conclusions we reach. The logic of triangulation is related to the enrichment (internal validity) that an investigation receives when different research techniques are applied to the initial data collection and its subsequent interpretation, and different methodological perspectives are adopted, or different data are offered. This increases the reliability (external validity) of the conclusions, due to the empirical comparison with similar data from the application of different methods and techniques (

Ruíz-Olabuénaga 2004).

The methodology we use adds the precision of the objective data of the quantitative methodology (statistical use of the nullities, separations and divorces database) to the understanding of the subjective meaning of the in-depth qualitative interviews, while at the same time controlling the quality of the research by the convergence of two perspectives in the same target: same-sex divorce.

2.1. Quantitative Methodology

Secondary data analysis has been used, specifically the statistics on annulments, separations and divorces (ENSD; 2012–2018). The choice of this database is justified in that it is the only one that provides the necessary data for this analysis, including dissolutions of same-sex marriages and some of their characteristics. The period analyzed is the maximum possible, since it considers the data from the beginning of the historical series in 2012 to 2018.

This data, compiled by the National Institute of Statistics (INE) by virtue of an agreement with the General Council of the Judiciary (CGPJ), are compiled from information on sentences provided by different competent judicial bodies in this matter, and the collected information referring to the annulments, separations and divorces that occur annually in Spain.

Regarding the variables used in the analysis (see

Table 1), it should be noted that some of them have been recoded or generated from others that already exist. Thus, the variables “sex of the first spouse” and “sex of the second spouse” have been used to build a new one called “type of marriage”, allowing us to differentiate between two attributes: “between people of different sex” and “between people of the same sex”. Subsequently, and based on this last variable, a new variable “same-sex marriage” has been constructed with two categories: “between men” and “between women”.

This permits, when crossing with any other variable, the obtention of different information depending on the type of marriage. Another one of the fundamental variables is the “judgment ruling”, which makes it possible to obtain the existence of consensus or conflict in the divorce process. It has been recoded to only offer cases where divorces occur, because separations in this type of couple are scarce, distinguishing between consensual and non-consensual. Finally, with respect to the item “duration of marriage” it has been recoded with the aim of grouping time periods together. This allows for the extraction of more condensed and interpretable information.

Regarding data processing, a descriptive analysis has been chosen, since it helps to show and understand the changes produced in society (

Sánchez et al. 2010). The choice of this technique is based mainly on two reasons: On the one hand, the objective of the research is not aimed at establishing relationships or performing any analysis referring to the dependence or interdependence of variables; and on the other hand, the lack of primary data related to the population on which the analysis is focused, therein creating the first attempt to study the dissolution of same-sex marriages in Spain.

2.2. Qualitative Methodology

Regarding the qualitative methodology, the interview technique has been used in a semi-structured manner. The participants have been selected based on two inclusion criteria: first, having been married and currently divorced; second, the autonomous communities (AC) of origin, selecting where there are more marriages and divorces between people of the same sex (community of Madrid, Catalonia, Andalusia and the community of Valencia).

The sample carried out has been intentional and for this reason, various associations and academic bodies have been contacted. The final sample is made up of 24 participants with whom it is intended to achieve discursive saturation (see

Table 2). The average age of the participants is 38.6 years (minimum age 32 years and maximum age 49 years) and of the twelve terminated couples interviewed, five have children.

The interviews were carried out individually and online, thus avoiding the appearance of any type of information bias. The participants gave their informed consent and authorized their recording. To ensure their confidentiality, the original names were not shown in the transcripts, replacing them with numbers. The interviews lasted approximately sixty minutes and were transcribed and subsequently coded. The qualitative analysis software was Atlas.ti.

The analysis technique used in the interviews was a discourse analysis. This technique was selected because what is obtained is not necessarily a reflection of what happened at the production level, yet what remains are traces, clues, threads, and symptoms that the analyst must know how to describe and interpret (

Santander 2011).

To carry out this technique, it is necessary, according to

Manzano (

2005), to identify the components that surround the discourse, delve into its dense content, and finally, generate a complete model of the discourse, which allows the study of the discursive representations in circulation, focusing attention on the established categories (

Sayago 2014).

In our research, the categories selected for the analysis were: main causes for divorce, duration of the relationship, having or not having children, assigned custody modality and agreement or disagreement in the divorce process. These categories are justified by the added ability to maintain coherence throughout the investigation, and thus permitting us to deepen the knowledge of what was obtained through the previous quantitative analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

First, the results obtained after applying the quantitative technique described above are presented. This will allow an overview of the evolution of same-sex divorce in Spain. Subsequently, the results produced through the elaboration and analysis of the interviews developed are shown, thus being able to deepen the understanding of the social reality studied.

3.1. Quantitative Results

As can be seen (

Figure 3), the dissolution of marriages in this population group have been on the rise, which is reasonable considering the number of marriages that have been celebrated each year.

In general, same-sex divorces in Spain have doubled, going from 408 in 2012 to 1141 in 2018. More specifically, it is highlighted that throughout the series of historical data, divorces between two men and those between two women tend to equalize, and in the last available year (2018), placing themselves at 595 and 546, respectively. This fact is especially relevant in relation to the study by

Kolk and Andersson (

2020) that demonstrates that the risk of divorce in marriages between women are much greater than those in any other kind of marriage.

In relation to this type of breakup, it is interesting to note some of the characteristics related to the duration, type of divorce (

Table 3), existence of children and the custody of children (

Table 4).

Both in the case of marriage between two men and between two women, divorce normally occurs after the first two years of union. The series of data indicates that the dissolution of the couple is less and less frequent each year after the first five years. Specifically in the case of marriage between two men, this percentage has fallen by 3.7% from 2012 to 2018. In the case of marriages comprising women, the dynamic is similar, with the drop in divorce being even more accentuated (8.51%). We emphasize that out of the same sex marriages who divorced in each year, the percentage of female couples who divorced within 2 years is about twice as large as the percentage among males.

A general consensus within the couple about the need for divorce can be seen in most cases that end through consensual divorce processes. This degree of consensus has fluctuated continuously during the analyzed period, reaching 84.23% in 2018 for men and 82.23% for unions between women. As a general rule, the divorce processes of same-sex marriages present a higher percentage of consensus than in heterosexual couples, as supported by the research carried out in Spain by

Becerril and Jiménez (

2016). This low level of conflict in the dissolution of this type of marriage is something that not only occurs in the Spanish context, but has also been pointed out in previous international research carried out in other countries, such as the United States (

Goldberg and Allen 2013).

Moreover, with regard to one of the central issues in divorce proceedings, dissolved marriages formed by people of the same sex with the presence of children represented 40.6% in 2018. This figure, regarding men, has remained more or less stable over time, with values fluctuating between 9.1% and 12.6%. For dissolutions of couples comprising women, this percentage is higher throughout the analyzed period, reaching the highest figure in the series, 29.7%, in 2018. The differences between the figures for men and women may be due, in part, to the greater difficulty of the former in accessing paternity. In fact, as the study by

Rozental and Malmquist (

2015) emphasizes, it seems evident that the opportunities to become parents are much greater for women than they are for men in same-sex marriages due to the possibilities granted by the biological process of maternity and the use of assisted reproduction methods.

In addition, the fact that there are more children in divorced marriages formed by women may be related to the increase in breakups, as some international research points out (

Gartrell et al. 2006;

Turteltaub 2002). In this sense, and although the authors did not explore in depth the explanations of the women for their breakup, they outlined certain aspects that led to a greater probability of divorce. Among these aspects, incompatibility and different parenting styles stand out as reasons for dissolving their unions (

Gartrell et al. 2006). Under this same thesis,

Turteltaub (

2002) found that women mentioned disagreements about paternity as the cause of the dissolution of their marriages. They also noted that poor communication is often compounded by the challenges of parenting.

Finally, it should be noted that in the event of divorce with the presence of children, the shared custody modality has been, for some years, the most predominant. Prior to 2016, the dominant model was exclusive custody of one of the spouses, but since that year, the shared custody modality obtained popularity, reaching 51.8% in 2018. It should be noted that this percentage is far removed from the reality of what happens after heterosexual divorce, where the mother has exclusive custody as the most repeated modality (61.5% in 2018), and the shared custody modality representing 33.8%.

3.2. Qualitative Results

Following the description of the evolution of same-sex marriage divorce and some of its most relevant aspects, the results are further specified by generating four main categories: causes of marital dissolution, duration of the relationship, possession or not of children and the assignment of child custody.

3.2.1. On the Motivations That Caused the Marital Dissolution

As the literature related to marital termination has shown, there are many factors that influence it. Among these, the following problems stand out: issues with peaceful coexistence, the end of romantic love in the relationship, the scarcity of problem-solving strategies and infidelity (

Triana et al. 2006). However, there are no detailed analyses of the obvious causes in the case of same-sex divorce.

In this sense, it is evident in the discourse of the interviewees that the problems related to coexistence, the end of romantic love in the relationship and infidelity are present. The participants of this investigation highlight these factors, practically in their entirety. For example, K21 and K22 point out that:

“I don’t know if we got married young, if we should have lived together longer before getting married, I don’t know (…) after a short time we realized that we didn’t love each other like before. It wasn’t the same.”

(K21, Male)

“I loved Leo very much. I still love him a lot, but as a friend. What we had was very intense but not for a lifetime. Love faded away and no one made an effort. I don’t regret getting married but breaking up was the best thing we could do because I want to be a father and I couldn’t see myself with him”

(K22, Male)

However, among those divorced couples with children, there is one element that stands out as a key to understanding the reason for the end of the marriage: The decision to have children and their child rearing educational/developmental style. In this sense, D7 exposes how she herself places the beginning of the end of their relationship at the moment they decided to have children:

“(…) we were very excited but at the same time we had very frequent fights, all day. We couldn’t agree on who would be the one to have the baby, you know what I mean. Our excitement was reinforced and we reminded ourselves that we were together for many different reasons (…). But this already planted a seed that would not go away. After having our son we started to have more problems. We did not agree on how to raise him. The simple fact of baptizing him or not was an untenable situation. The best thing was to leave the relationship for our own good and that of our son.”

(D7, Female)

This vision does not vary much in other interviews with sons and daughters—on the contrary, it is a shared experience. Thus H15, who shares custody of her daughter with her ex-partner, points out the following:

“The moment we had our daughter the tensions began. I don’t know why, we had always been the same, the same decisions, we thought the same (…) Everything changed, anything related to our daughter was entailed a fight.”

(H15, Female)

The discourse of the interviewees confirmed that the most common causes of rupture detected in the literature, such as the lack of a peaceful coexistence, or the scarcity of problem-solving strategies, exist in this type of marriage. However, the most noteworthy discourse obtained focused on those divorced couples with children in which problems related to incompatibility and different parenting styles are presented as reasons for dissolving their unions, something detected in previous research at the international level (

Gartrell et al. 2006;

Turteltaub 2002).

3.2.2. How Long Did the Marriage Last? Causes of Divorce

Throughout the discourses of the various interviewees, the relationship between the duration of marriage, age and maturity stands out in the same way. Once again, differences can be observed between the marriages made up of people of the same sex who have children and those who do not. J19 points this out in the following example:

“I got married young, when I was 30 years old. Well, young compared to the people around me. I think in those times it wasn’t something people gave much thought to, I wasn’t mature enough. She wasn’t either, she’s a year older than me. We could have just decided to live together instead. At that time we were excited about it. Now I don’t see it that way (…) Perhaps that’s why we separated so soon, we haven’t even been married for 3 years.”

(J19, Female)

In the dissolved marriages between women, the duration of the relationship has been one of the group’s most frequently repeated matters. The aspect of age is mentioned, articulating its relationship with personal maturity. Thus, reference is made to the age of the spouses in the sense of acquired/developed maturity to make certain decisions. There is some agreement that age provides certain experiences to face situations in a different way. This is clearly exposed in the case of interviewees C5 and C6, aged 32 and 33, respectively.

“Yes, our relationship lasted a year and a half. I don’t remember exactly, but I’d tell you a year and 4 or 5 months (…). If I think about it, it’s normal that we broke up, I wasn’t even 30 years old when I got married. We sinned impulsively, it was all very hasty.”

(C5, Male)

“At 20 years old you are not as responsible as at 30, nor at 30 as at 32. Obviously, because of how it turned out, maybe we took the relationship too fast, we were only together for one year. Neither of us were mature nor responsible, but we loved each other very much.”

(C6, Male)

It seems as if a more advanced age translates to a greater degree of maturity, and thus this could lead to better decision-making. This may coincide with the duration of the relationship of those marriages that have been dissolved and have children. The case of L23 highlights this factor:

“We were together for almost 20 years, dating, and married (…). We decided to adopt a daughter when I was 41 and he was 38 years old. Everything was thought out. We knew that the process would be hard and would have emotional costs. We have been married for 12 years (…) It is true that the adoption process was hard but we got through it. The separation was caused by other reasons but I can say that our marriage was going well in general. ”

(L23, Male)

3.2.3. Having Children in the Divorce Process: An Increasingly Present Reality

Having children in marriages or couples made up of people of the same sex is a social reality on the rise, as can be corroborated with the data from the ENSD (2012–2018). Likewise, the terminations of this type of marriage are not particularly characterized by the fact that they occur with children, although this situation is becoming more and more frequent. So far, more than half of these marriages are childless at the time of divorce. Various aspects can be extracted from the interviewee’s comments that lead to this situation (economic, labor or age, among others). Although, there is one that especially stands out: The difficulties that these types of couples have to become parents.

“In many moments we thought about being mothers, building our family. But there was a problem. You have to resort to some techniques. This costs money and you have to have it to be able to do it. It’s not that easy (…) Adoption is another way, yes, but do you know how complex it is? Do you know how long it takes?” (…)

(E9, Female)

“It always crosses my mind, the idea of being parents. But honestly, I think it was not an idea that was around a lot. Perhaps only in my case, and that contributed to us breaking up. But it is very complicated, adoption, surrogacy isn’t allowed…and then, what about the idea of having two dads? That topic is still not accepted in this country. It’s not completely normalized and I don’t want my child to suffer because of it, I couldn’t bear that.”

(F12, Male)

“We have a daughter, do you know how expensive the artificial insemination process is? The costs were a barrier for us. (…) Of course we would have liked to give her a little brother but it was impossible.”

(H15, Female)

The people interviewed highlighted different difficulties in having children, such as the temporary, economic and also the emotional cost, and one decisive aspect stands out: The perception that a child may not understand, or may suffer socially for having two fathers or two mothers, an issue that for the interviewees does not seem to be entirely clear, as I18 points out:

“We decided to be parents. We wanted it more than anything. It caused many problems, many emotional problems as well. It took a toll on our relationship. But we wanted it (…) The problem was not just having a boy or a girl, it was seeing how people reacted, two fathers in Granada, practically a small town, with a child. Socially it is accepted but you notice things, looks, gossip… I’m sorry but that’s how it is.”

(I18, Male)

Moreover, another factor is the number of children. In this type of marriage, there is usually a low number (1 in 2017, INE) while in heterosexual marriages this figure is slightly higher (1.3 in 2017, INE). From the interviewee’s discourses, it can be deduced that this data is, in part, related to the difficulties of access to maternity/paternity.

3.2.4. With You, with Me or with Both? Allocation of Custody after Divorce

In relation to divorce and child custody, a decisive question arises: The type of custody that is assigned when the couple has children together. This aspect is essential.

Suso et al. (

2012) refer to the fact that when couples have children, the situation becomes more complex and the solution to the custody of minors constitutes a process with multiple edges and problems. For this reason, this variable can have an important influence on whether or not the divorce process will be consensual or not for both parties.

While in heterosexual divorces, the most frequent modality is where the mother has exclusive custody, but in divorces of married couples composed of people of the same sex, in more than half of the occasions, the shared custody modality is granted. According to those interviewed, this modality is more beneficial for the children, so they prefer to try to establish it regardless of the relationship they have with their former partner. They also make clear the fact that the sons and daughters are the responsibility of both parties.

“We decided to have children. We opted for the artificial insemination method. We have a son. We didn’t want to have more. We fought about how we should raise our son (…) having one was enough, wow. When we divorced, the most important thing was what would happen to our child, who he would be with. (…) It’s responsibility we both share. Although our breakup went very badly, it was a divorce and a horrible situation, we decided to establish a shared custody.”

(D7, female)

“In our case, we did take it into account. What would happen to our daughter if we divorced? The girl is adopted, she belongs to both of us. At the time we would have liked to have another child but the adoption processes are insufferable, it created a lot of tension in our day to day life. (…). When we separated, each one wanted to keep her all to himself, but we understood, and they made us see that both of us having custody could be beneficial for her. So we did. (…) we do not regret it, our little girl is fine and happy.

(L23, Male)

Through these last discourses, it is observed how divorced people with children have parental co-responsibility in mind and understand that the shared custody modality is beneficial for their sons and daughters. This may be related, among other aspects, to more egalitarian gender roles or to the greater degree of agreement existing in the divorce processes of these couples.

3.2.5. Type of Procedure: Consensus or Disagreement

The way in which the divorce occurs, consensual or not, depends on multiple variables (reason for the breakup, what the relationship has been like, problem-solving ability, negotiating capacity, etc.). Likewise, other essential aspects depend on the result of the sentence and the process of rupture (consensual or contested): Assignment of child custody and the distribution of assets. The interviewees attach importance to whether or not the ruling of the sentence is consensual, due to the future consequences that this may have. The existence of a “bad or good relationship” between spouses and the “history of the relationship” are factors to take into account in any breakup, not only to understand what the causes of the divorce were, but also to understand the aspects derived from this.

For example, B3 and B4 show a clear example of how the development of their marriage allowed them, in a conflictive and painful situation, to reach an agreement:

“In the beginning it was difficult. We didn’t have any major problems in our marriage. The infidelity caused everything, that was the essential reason for our breakup. Everything was fine before, at least for me. Despite the resentment and hatred, I am not going to lie to you, but I hated her, I preferred to reach a divorce agreement for emotional reasons, time and for our finances.”

(B4, Female)

“She knows I loved her. Our relationship was healthy and beautiful, but I was wrong. I made a mistake. I think it could have been fixed but there was no way. She didn’t want to talk but we had to come to an agreement. We had had a beautiful relationship, it was not necessary or acceptable to end badly in court.”

(B3, Female)

In the stories of the people interviewed, it can be seen how the existence of a good relationship can lead to a process in which negotiation is possible. This happens in the same way when divorced couples have children and custody proceedings have to be settled, as expressed by I17 and A2:

“The two of us got divorced from each other, not from our son. What can we do? It didn’t turn out badly, and the child was not to blame. We were clear that both of us would have custody. Our son is adopted and legally, he is both of our child. That was the best possible agreement we could have made.”

(I17, Male)

“The custody of my daughter is mine solely, (…) our relationship was bad, there was no way to come to an agreement, we would have several fights all in the same day and he never took care of his daughter. Obviously there was no room for negotiations and in the end, I’m not the one suffering. It’s my daughter who is.”

(A2, Male)

The custody modality decided upon related to the consensual or non-consensual nature of the divorce may be affected by the degree of conflict in the relationship. According to the conclusions obtained by

Wilcox et al. (

1998), shared custody is more likely when there is a low level of conflict between the members of the couple. However, if the existence of conflict in their previous life together and the subsequent divorce process is not very high, the possibility of reaching agreements increases. If there are high levels of conflict, the shared modality is less likely.

4. Conclusions

Next, we will answer the research questions initially raised. In relation to when and why divorce occurs, we know that marriage dissolutions between same-sex couples have been on the rise in recent years, reaching 1141 divorces in 2018, and in fact, there have been about 24 dissolutions for every 100 marriages. The dissolution of these marriages occurs mostly after the first two years, and fewer and fewer marriages end after five years, although breakups between women are twice as frequent as those between men. This last point is related to the studies previously carried out by

Kolk and Andersson (

2020) that found higher probabilities of divorce in couples comprising women than in couples comprising men.

Through analyzing the interviewee’s discourses, we have identified various factors that influence the dissolution of the marriage, such as the lack of a peaceful coexistence, the end of romantic love in the relationship and infidelity. One of the reasons given frequently is linked to the age of the spouses, there seems to be a relationship between younger age and inadequate management of relationship problems that lead to the couple breaking up. In 2018, four out of ten marriages that dissolved involved children. In fact, the members of the married couples highlight the difficulties they had in being able to be fathers/mothers and raising children, thus converting these factors into key elements in the understanding of their breakups.

In relation to the second question raised about the non-consensual nature of divorce, the ENSD data indicates that in the vast majority of cases, the divorce process is consensual. In fact, it is almost eighteen percent higher than that of heterosexual couples. These couples are very aware that the result of the sentence and the breakup process is closely related to aspects, such as the distribution of assets and custody of the children. This leads to the third research question initially posed: “What is child custody like?” Marriages made up of people of the same sex have a high level of parental co-responsibility and understand that joint custody is beneficial for their sons and daughters, which is why this custodial modality is granted in half of the cases, which may be related to more egalitarian gender roles and the existence of a greater degree of agreement in the divorce processes.

This investigation has attempted to address, for the first time in Spain, an analysis of breakups in same-sex couples, through various methodologies, with the aim of not only describing the social reality, but also coming to understand the realities that are hidden beneath these figures. The limitations of this investigation revolve around the intentional sample used in the interviews. Despite being carried out rigorously, we would need more qualitative research in this field of knowledge to, through the consensus of the scientific community, corroborate the results obtained through different approaches. In any case, the methodological strategy of this investigation has managed to empirically match the data obtained by two other investigations with different methodological applications, and through observing how they coincide, a richer, more complete and guaranteed set of conclusions has thus been acquired.