Violent Drug Markets: Relation between Homicide, Drug Trafficking and Socioeconomic Disadvantages: A Test of Contingent Causation in Pereira, Colombia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Review of Research

2.1. Drug Trafficking and Systemic Violence

2.2. Contingent Causation Models

2.3. Socioeconomic Disadvantages as a Factor Conditioning the Drug Market–Homicide Relationship

2.4. The Application of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) in Studies of Violence and Crime

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

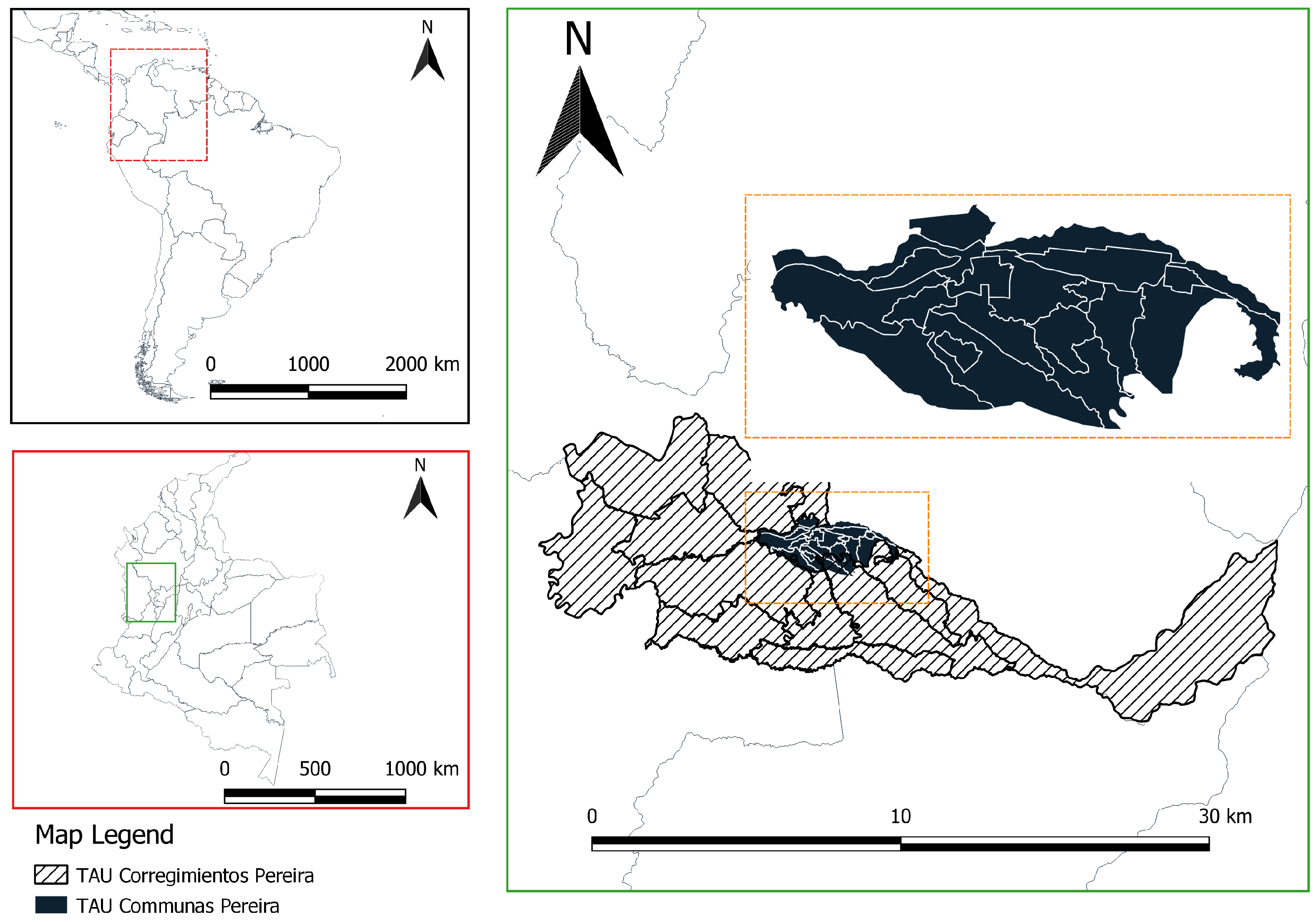

3.2. Sample

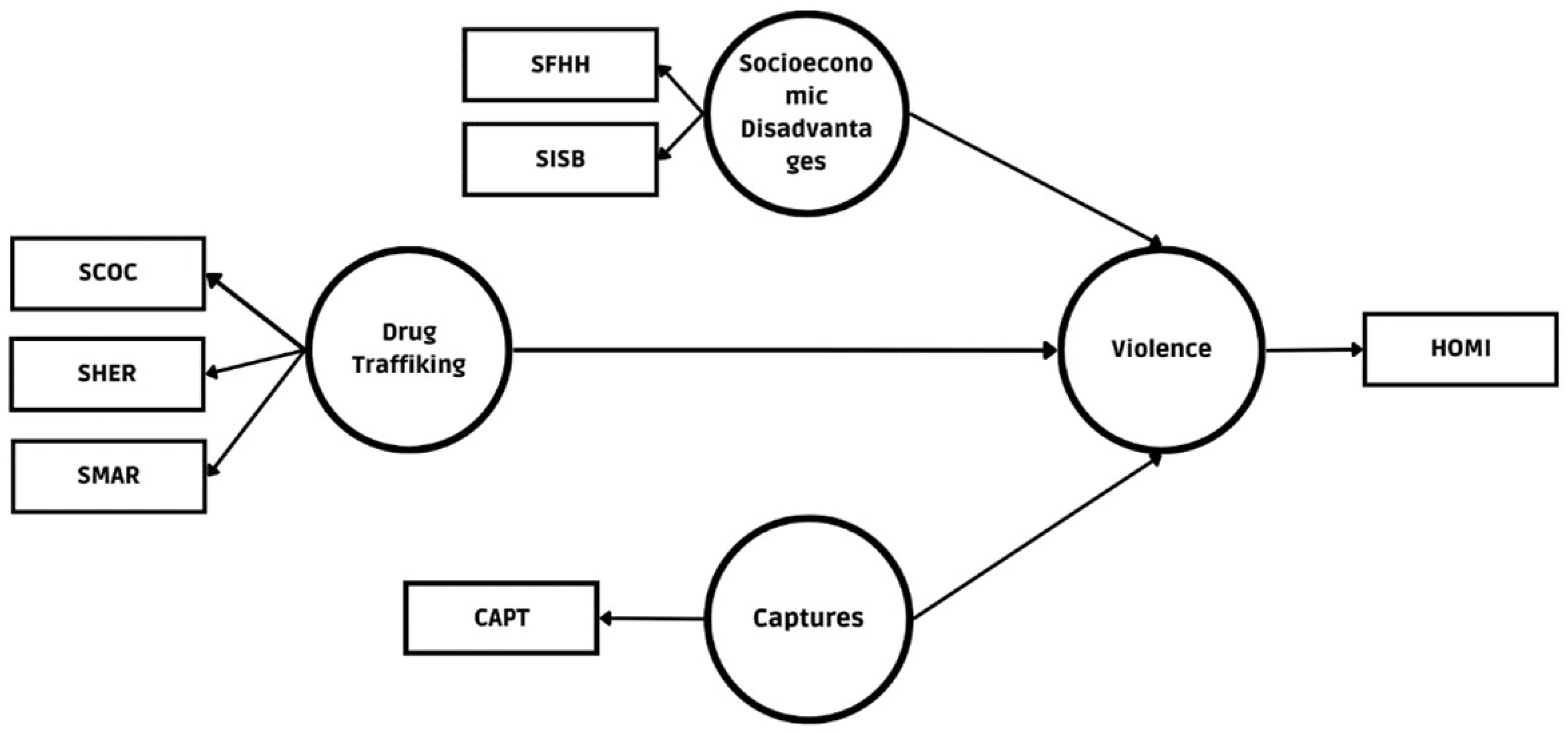

3.3. Variables

3.4. Statistical Methods

3.5. Model Assessment

- Internal consistency: Composite Reliability (CR);

- Convergent validity: Average Variance Extracted (AVE);

- Discriminant validity: Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT);

- Reliability Indicator: External loads and their significance.

4. Results

Model Assessment

5. Disscusion

5.1. Drug/Violence Nexus

5.2. Socioeconomic Disadvantages/Violence Nexus

5.3. About PLS-SEM Uses

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Squares—Structural Equation Modelling |

| CNP | Colombian National Police |

| TAU | Territorial Administrative Units |

| HOMI | Homicides |

| SMAR | Marijuana Seizures |

| SCOC | Cocaine Seizures |

| SHER | Cocaine Seizures |

| CAPT | Captured for drugs |

| SFHH | Single-Parent Female-Headed Households |

| SISB | SISBEN |

| DTO | Drug Trafficking Organization |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| HTMT | Heterotrait–Monotrait |

References

- Álvarez, Juan Miguel. 2015. Balas Por Encargo. Vida Y Muerte de Los Sicarios en Colombia. Bogotá: Rey Naranjo Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Alzate-Zuluaga, Mary Luz, and Williams Gilberto Jiménez-García. 2021. Rackets and the Markets of Violence: A Case Study of Altavista, Medellín, Colombia. Latin American Perspectives 48: 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, Enrique Desmond. 2019. Social responses to criminal governance in rio de janeiro, belo horizonte, kingston, and medellín. Latin American Research Review 54: 165–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arias, Enrique Desmond, and Daniel M. Goldstein. 2010. Violent Democracies in Latin America. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Azariadis, Costas, and John Stachurski. 2005. Poverty Traps. In Handbook of Economic Growth. Edited by Philippe Aghion and Steven Durlauf. North Holland: Elsevier, vol. 1A, pp. 295–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beittel, June S. 2018. Mexico: Organized Crime and Drug Trafficking Organizations. In Congressional Research Service; pp. 11–37. Available online: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/details?prodcode=R41576 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Benitez, Jose, Jörg Henseler, Ana Castillo, and Florian Schuberth. 2020. How to perform and report an impactful analysis using partial least squares: Guidelines for confirmatory and explanatory IS research. Information and Management 57: 103168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, Mark, and Andres Rengifo. 2009. Rethinking Community Organization and Robbery: Considering Illicit Market Dynamics. Justice Quarterly 26: 211–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, Marcelo, and Gabriel Kessler. 2008. Vulnerabilidad al delito y sentimiento de inseguridad en buenos aires: Determinantes y consecuencias. Desarrollo Economico 48: 209–34. [Google Scholar]

- Blumstein, Alfred. 1995. Youth Violence, Guns, and the Illicit-Drug Industry. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 86: 10–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggess, Lyndsay N., and Jon Maskaly. 2014. The spatial context of the disorder-crime relationship in a study of Reno neighborhoods. Social Science Research 43: 168–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, Samuel, Steven Durlauf, and Karla Hoff. 2006. Poverty Traps. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cassel, Claes, Peter Hackl, and Anders H. Westlund. 1999. Robustness of partial least-squares method for estimating latent variable quality structures. Journal of Applied Statistics 26: 435–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, Christopher, and John R. Hipp. 2020. Drugs, Crime, Space, and Time: A Spatiotemporal Examination of Drug Activity and Crime Rates. Justice Quarterly 37: 187–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, Yofre, Rodolfo Parra, and John Durán. 2012. Narcomenudeo. Entramado Social Por la Institucionalización de Una Actividad Economica Criminal, 1st ed. Bogotá: Imprenta Nacional de Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- Cupani, Marcos. 2012. Análisis de Ecuaciones Estructurales: Conceptos, etapas de desarrollo y un ejemplo de aplicación. Revista Tesis 1: 186–99. [Google Scholar]

- De León Beltrán, Isaac. 2014. Aprendizaje Criminal en Colombia. Un Análisis de Las Organizaciones Narcotráficantes. Bogotá: Ediciones de la U. [Google Scholar]

- Del Olmo, Rosa. 1999. América Latina y su Criminología. Ciudad de México: Siglo XXI Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez, Manuel. 2010. The Institutionalization of Drug Trafficking Organizations Comparing Colombia and Brazil. Master’s thesis, Calhoul Naval Pograduate School, Monterey, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Espejo-Duarte, María. 2021. Drug-Trafficking in Colombia: The New Civil War against Democracy and Peacebuilding. Co-herencia 18: 157–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etikan, Ilker, Sulaiman Abubakar Musa, and Rukayya Sunusi Alkassim. 2016. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics 5: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fiscalia General de la Nación. 2019. Documentos de Política Pública y Armas y Homicidios, Volume 1. Bogotá: República de Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- Franz, Tobias. 2016. Plan Colombia: Illegal drugs, economic development and counterinsurgency—A political economy analysis of Colombia’s failed war. Development Policy Review 34: 563–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresneda, Oscar, and Patricia Martínez. 2000. Identificación y Afiliación de Beneficiarios SISBEN. Bogotá: República de Colombia. Ministerio de Salud. [Google Scholar]

- García, Viviana. 2022. Drogas y gobernanza local en Pereira. In América Latina en la Guerra Contra Las Drogas. Una Mirada Multidimensional a Un Fenomeno Global. Bogotá: IEPRI-Universidad Nacional de Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- Garson, G.D. 2016. Partial Least Squares: Regression & Structural Equation Models, 3rd ed. Asheboro: G. David Garson and Statistical Associates Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Garthe, Rachel C., Deborah Gorman-Smith, Joshua Gregory, and Michael E. Schoeny. 2018. Neighborhood Concentrated Disadvantage and Dating Violence among Urban Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Neighborhood Social Processes. American Journal of Community Psychology 61: 310–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, Paul. 1985. The drugs/violence nexus: A tripartite conceptual framework. Journal of Drug Issues 39: 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, Paul, Henry Brownstein Patrick Ryan, and Patricia Bellucci. 1997. Crack and homicide in New York City: A case study in the epidemiology of violence. In Crack in America; Demon Drugs and Social Justice. Edited by Craig Reinarman, Harry G. Levine and Harry Levine. Los Ángeles: University of California Press, pp. 113–30. [Google Scholar]

- Grogger, Jeff, and Michael Willis. 2000. The emergence of crack cocaine and the rise in urban crime rates. The Review of Economics and Statistics 82: 519–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, Kaaryn. 2009. The criminalization of poverty. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 99: 643–716. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, Joseph, Thomas Hult, Chiristian Ringle, Marko Sarstedt, Nicholas Danks, and Soumya Ray. 2021. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R, 1st ed. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph, Tomas Hult, Marko Saestedt, Christian Ringle, G. Tomas Hult, Christian Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2017. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed. New York: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Herring, Chris, Dilara Yarbrough, and Lisa Marie Alatorre. 2020. Pervasive Penality: How the Criminalization of Poverty Perpetuates Homelessness. Social Problems 67: 131–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inciardi, James. 1981. The Drug-Crimes Connection. Beverly Hills: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Jacques, Scott, and Richard Wright. 2011. Informal control and illicit drug trade. Criminology 49: 729–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-García, Williams, and Mary Luz Alzate-Zuluaga. 2023. La violencia multicausal. Aportes teóricos y empíricos para su comprensión en América Latina. In Génesis, Desarrollo y Finalidad de La AccióN Violenta. Reflexiones Filosóficas y Hermenéuticas. Edited by K. Mueller Uhlenbrock, C. Nussbaumer and F. Rivero. Ciudad de México: Editorial UNAM, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-García, Williams Gilberto, and Rafael Rentería-Ramos. 2020. Contributions of complexity for the understanding of the dynamics of violence in cities. Case study: The cities of Bello and Palmira, Colombia (Years 2010–2016). Revista Criminalidad 62: 9–43. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-García, Williams Gilberto, Liliana Manzano-Chavez, and Alejandra Mohor-Bellalta. 2021. Medición de la vulnerabilidad social: Propuesta de un índice para el estudio de barrios vulnerables a la violencia en América Lxtina. Papers: Revista de Sociologia 106: 381–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-García, Williams Gilberto, Wilson Arenas, and Natalia Bohorquez-Bedoya. 2021. Génesis Nesis Del Mercado de Las Drogas en Pereira. Una Historia Del Contrabando Y Cultura de la Ilegalidad. Available online: https://repositorio.utp.edu.co/items/02cd98a7-f8af-40da-a596-2f006f5106b0 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Johnson, Lallen T., and Juwan Z. Bennett. 2017. Drug markets, violence, and the need to incorporate the role of race. Sociology Compass 11: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, Karl. 1993. Testing structural equation models. In Testing Structural Equation Models. Edited by K. Bollen and S. Long. Newbury Park: SAGE Publications Ltd., pp. 249–316. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, Jeffrey H. 2006. Factor Analysis in Counseling Psychology Research, Training, and Practice: Principles, Advances, and Applications. The Counseling Psychologist 34: 684–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, Michael. 2007. The architecture of drug trafficking: Network forms of organisation in the Colombian cocaine trade. Global Crime 8: 233–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, Rex. 2011. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelling, 3rd ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kostelnik, James, and David Skarbek. 2013. The governance institutions of a drug trafficking organization. Public Choice 156: 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kronick, Dorothy. 2020. Profits and Violence in Illegal Markets: Evidence from Venezuela. Journal of Conflict Resolution 64: 1499–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCoun, Robert, and Peter Reuter. 2001. Drug War Heresies: Learning from Other Vices, Times, and Places. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Manzano, Liliana, Alejandra Mohor, and Williams Gilberto Jiménez-García. 2020. Violent Victimization in Poor Neighborhoods of Bogotá, Lima, and Santiago: Empirical Test of the Social Disor ganization and the Collective Efficacy Theories From the Social Disorganization Theory to the Collective Efficacy. In The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of Latin America. Edited by X. Bada and L. Rivera-Sánchez. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 818–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoulides, George A., and Carol Saunders. 2006. Editor’s Comments: PLS: A Silver Bullet? MIS Quarterly 30: iii–ix. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, Minerva, and Eréndira Fierro. 2018. Application of the PLS-SEM technique in Knowledge Management: A practical technical approach. RIDE Revista Iberoamericana para la Investigación y el Desarrollo Educativo 8: 130–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McIlwaine, Cathy, and Caroline O. N. Moser. 2001. Violence and social capital in urban poor communities: Perspectives from Colombia and Guatemala. Journal of International Development 13: 965–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, Caroline, and Elizabeth Shrader. 1999. A Conceptual Framework for Violence Reduction. Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Operti, Elisa. 2018. Tough on criminal wealth? Exploring the link between organized crime’s asset confiscation and regional entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics 51: 321–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, William. 2017. Reclutamiento forzado de niños, niñas y adolescentes: De víctimas a victimarios. Encuentros 15: 147–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouimet, Marc, Aurélien Langlade, and Claire Chabot. 2018. The dynamic theory of homicide: Adverse social conditions and formal social control as factors explaining the variations of the homicide rate in 145 countries. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice 60: 241–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousey, Graham C., and Matthew R. Lee. 2002. Examining the conditional nature of the illicit drug market-homicide relationship: A partual test of the theory of contingent causation. Criminology 40: 73–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousey, Graham C., and Matthew R. Lee. 2007. Homicide trends and illicit drug markets: Exploring differences across time. Justice Quarterly 24: 48–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, Letizia. 2004. The illegal drugs market. Journal of Modern Italian Studies 9: 186–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachristos, Andrew V., David M. Hureau, and Anthony A Braga. 2013. The Corner and the Crew: The Influence of Geography and Social Networks on Gang Violence. American Sociological Review 78: 417–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parker, Karen F., and Amy Reckdenwald. 2008. Concentrated disadvantage, traditional male role models, and African-American juvenile violence. Criminology 46: 711–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pécaut, Daniel. 2001. La tragedia colombiana: Guerra, violencia, tráfico de droga. Revista Sociedad y Economía, 133–48. [Google Scholar]

- Pécaut, Daniel. 2002. De la banalidad de la violencia al terror real el caso de Colombia. In Las Sociedades Del Miedo: El Legado de la Guerra Civil, la Violencia Y El Terror En América Latina. Edited by D. Kruijt and K. Kees. Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca, pp. 157–84. [Google Scholar]

- Piña, Francisco, and Juan Poom. 2019. Deterioro social y participación en el tráfico de drogas en el estado de Sonora. Frontera Norte 31: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portella, Daniel Deivson Alves, Edna Maria de Araújo, Nelson Fernandes de Oliveira, Joselisa Maria Chaves, Washington de Jesus Santa, Anna da Franca Rocha, and Dayse Dantas Oliveira. 2019. Intentional homicide, drug trafficking and social indicators. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 24: 631–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, Travis C., and Francis T. Cullen. 2005. Macro-Level Assessing Theories of Crime: A Meta-Analysis. Crime and Justice 32: 373–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- República de Colombia. DANE. 2022. Proyecciones de Población. Available online: https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/demografia-y-poblacion/proyecciones-de-poblacion (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Reuter, Peter, and Letizia Paoli. 2020. How similar are modern criminal syndicates to traditional mafias? Crime and Justice 49: 223–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, Jaír. 2008. La historia y el presente de las cifras delictivas y contravencionales en Colombia. Revista Criminalidad 50: 109–17. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Vignoli, Jorge. 2000. Vulnerabilidad Demográfica: Una Faceta de Las Desventajas Sociales. Serie Población y desarrollo Número 5; Santiago de Chile: Naciones Unidas, CEPAL. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, John, Jennifer Yahner, and Janine Zweig. 2020. How do drug courts work? Journal of Experimental Criminology 16: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, Mauricio. 2005. Tres Décadas de Homicidios, Secuestro y Tráfico de Drogas en Colombia. Available online: https://www.repository.fedesarrollo.org.co/handle/11445/924 (accessed on 10 September 2022).

- Ruíz, Carmen, Renato Vargas, Laura Castillo, and Daniel Cardona. 2020. El Lavado de Activos en Colombia. Consideraciones Desde La Dogmática y La Política Criminal, 2nd ed. Bogotá: Universidad Externado de Colombia. [Google Scholar]

- Ruíz, Miguel, Antonio Pardo, and Rafael San Martín. 2014. Modelos de ecuaciones estructurales. Papeles del Psicólogo 31: 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sampson, Robert. 2009. Racial stratification and the durable tangle of neighborhood inequality. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 621: 260–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrica, Fabrizio. 2008. Drugs prices and systemic violence: An empirical study. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 14: 391–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatz, Sara, and Sidney Tobias. 2021. State ineffectiveness in deterring organized crime style homicide in Mexico: A vicious cycle. Crime, Law and Social Change 76: 233–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speckart, George, and M. Douglas Anglin. 1986. Narcotics and crime: A causal modeling approach. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 2: 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, Natalia. 2012. Como Corderos Entre Lobos. Del Uso Y El Reclutamiento De Niños, Niñas y Adolescentes en El Marco Del Conflicto Armado Y La Criminalidad en Colombi. Bogotá: Springer Consultin Services. [Google Scholar]

- Thoumi, Francisco. 1999. La relación entre corrupción y narcotráfico: Un análisis general y algunas referencias a Colombia. Revista de Economía del Rosario 2: 11–33. [Google Scholar]

- Thoumi, Francisco E. 2005. The Colombian competitive advantage in illegal drugs: The role of policies and institutional changes. Journal of Drug Issues 35: 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoumi, Francisco E. 2006. Organized Crime in Colombia. The Actors Running the Illegal Drug Industry. In The Oxford Handbooks in Criminologý and Criminal Justice. Edited by M. Tonry and L. Paoli. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 177–95. [Google Scholar]

- Thoumi, Francisco E. 2012. Illegal drugs, anti-drug policy failure, and the need for institutional reforms in Colombia. Substance Use and Misuse 47: 972–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonry, Michael, and James Wilson. 1990. Drugs and Crime. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, Grant, and Michele Staton. 2022. Discriminant Function Analyses: Classifying Drugs/Violence Victimization Typologies Among Incarcerated Rural Women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 37: 889–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinasco-Martínez, Diana. 2019. Pacificando el barrio: Orden social, microtráfico y tercerización de la violencia en un barrio del distrito de Aguablanca (Cali, Colombia). Revista Cultura y Droga 24: 157–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wo, James C. 2018. Understanding the density of nonprofit organizations across Los Angeles neighborhoods: Does concentrated disadvantage and violent crime matter? Social Science Research 71: 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaffaroni, E. Raúl. 2015. Violencia letal en América Latina. Cuadernos de derecho penal 13: 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaffaroni, Raul. 2008. Globalización y Crimen Organizado. Available online: https://www.docsity.com/es/globalizacion-y-crimen-organizado-e-raul-zaffaroni-el-po/3392480/ (accessed on 2 September 2022).

- Zhang, Yan, George Day, and Liqun Cao. 2012. A Partial Test of Agnew’s General Theory of Crime and Delinquency. Crime and Delinquency 58: 856–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimring, Franklin, and Gordon Hawkins. 1997. Crime Is Not the Problem: Lethal Violence in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Zuluaga, Victor. 2013. Historia Extensa. Pereira. Pereira: Universidad Tecnológica de Pereira. [Google Scholar]

| Latent Variable | Observed Variable | Calculation |

|---|---|---|

| Violence | Homicide (HOMI). Rate of homicides | HOMI = |

| Drug Traffiking | Marijuana Seizures (SMAR). Rate of drug seized in grams | SMAR = |

| Drug Traffiking | Cocaine Seizures (SCOC). Rate of drug seized in grams | SCOC = |

| Drug Traffiking | Heroine Seizures (SHER). Rate of drug seized in grams | SHER = |

| Captures | Captured for drugs (CAPT). Rate of arrests for all drugs | CAPT = |

| Socioeconomic Disadvantages | Single-female-headed-households (SFHH). Single-parent household rate | SFHH = |

| Socioeconomic Disadvantages | SISBEN. Rate of low-income households receiving government subsidies | SISB = |

| Variable | M | Error SD | SD | Min | Q1 | Median | Q3 | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOMI | 38.94 | 2.36 | 41.56 | 0.00 | 14.51 | 28.73 | 49.22 | 356.19 |

| SMAR | 2,298,491 | 776,485 | 13,671,424 | 0.00 | 11,493 | 41,318 | 145,413 | 133,092,610 |

| SCOC | 10,725 | 2082 | 36,666 | 0 | 63 | 533 | 3547 | 360,661 |

| SHER | 1059 | 392 | 6905 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 199 | 94433 |

| CAPT | 230.2 | 14.3 | 252.3 | 0.0 | 86.2 | 142.3 | 264.5 | 1543.7 |

| SFHH | 19,340 | 759 | 13,361 | 821 | 11,247 | 17,899 | 24,233 | 85,727 |

| SISB | 28,972 | 1049 | 18,475 | 369 | 19,341 | 27,467 | 32,871 | 95,740 |

| SRMR | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saturated model | 0.09 | 0.04 1 | 0.06 1 | 0.03 1 | 0.03 1 | 0.06 1 | 0.05 1 | 0.01 1 | 0.03 1 | 0.06 1 |

| Estimated model | 0.11 | 0.06 1 | 0.06 1 | 0.07 1 | 0.05 1 | 0.18 | 0.07 1 | 0.02 1 | 0.04 1 | 0,08 1 |

| Item 5 | Indicador | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Trafficking | CR | 0.729 | 0.983 | 0.953 | 0.995 | 0.978 | 0.972 | 0.923 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.936 |

| Drug Trafficking | AVE | 0.575 | 0.966 | 0.872 | 0.990 | 0.936 | 0.765 | 0.800 | 0.999 | 0.998 | 0.829 |

| Socioeconomic Disadvantages | CR | 0.949 | 0.950 | 0.956 | 0.959 | 0.969 | 0.972 | 0.979 | 0.982 | 0.982 | 0.989 |

| Socioeconomic Disadvantages | AVE | 0.903 | 0.905 | 0.915 | 0.920 | 0.940 | 0.945 | 0.958 | 0.965 | 0.965 | 0.978 |

| Loadings | SCOC | 4 | 0.988 3 | 0.844 2 | 4 | 0.986 2 | 0.657 1 | 0.797 3 | 0.999 2 | 0.999 2 | 0.900 2 |

| Loadings | SHER | 0.819 3 | 4 | 0.975 3 | 0.995 2 | 0.966 1 | 0.962 2 | 0.949 2 | 1.000 3 | 4 | 0.869 1 |

| Loadings | SMAR | 0.687 3 | 0.978 3 | 0.976 3 | 0.995 1 | 0.950 3 | 0.969 2 | 0.931 1 | 0.999 2 | 0.999 3 | 0.961 2 |

| Loadings | SFHH | 0.959 3 | 0.935 3 | 0.941 3 | 0.935 3 | 0.970 3 | 0.967 3 | 0.9800 3 | 0.979 3 | 0.975 3 | 0.987 3 |

| Loadings | SISB | 0.942 3 | 0.986 3 | 0.972 3 | 0.983 3 | 0.969 3 | 0.977 3 | 0.978 3 | 0.985 3 | 0.989 3 | 0.991 3 |

| Item 5 | Indicador | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socieconomic Disadvantage → Violence | Path | 0.573 2 | 0.327 1 | 0.523 3 | 0.223 | 0.724 3 | 0.611 3 | 0.728 2 | 0.577 3 | 0.203 | 0.374 |

| Socioeconomic Disadvantage → Violence | f2 | 0.543 | 0.131 | 0.433 | 0.052 | 1.312 | 0.428 | 1.286 | 0.506 | 0.051 | 0.155 |

| Drug Trafficking → Violence | Path | 0.737 3 | 0.344 2 | 0.684 2 | 0.435 | 0.556 3 | 0.527 4 | 0.644 2 | 0.812 3 | 0.812 3 | 0.796 2 |

| Drug Trafficking → Violence | f2 | 1.206 | 0.134 | 0.881 | 0.234 | 0.448 | 0.384 | 0.710 | 1.930 | 1.949 | 1.725 |

| Capture → Violence | Path | 0.270 | 0.268 4 | 0.326 2 | 0.076 | 0.305 2 | 0.080 | 0.214 | 0.073 | 0.380 2 | 0.058 |

| Capture → Violence | f2 | 0.121 | 0.089 | 0.169 | 0.169 | 0.233 | 0.007 | 0.111 | 0.008 | 0.177 | 0.004 |

| Capture | R2 4 | 0.543 | 0.118 | 0.468 | 0.189 | 0.309 | 0.277 | 0.415 | 0.659 | 0.659 | 0.633 |

| Violence | R2 4 | 0.397 | 0.200 | 0.370 | 0.059 | 0.602 | 0.438 | 0.588 | 0.346 | 0.216 | 0.154 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiménez-García, W.G.; Arenas-Valencia, W.; Bohorquez-Bedoya, N. Violent Drug Markets: Relation between Homicide, Drug Trafficking and Socioeconomic Disadvantages: A Test of Contingent Causation in Pereira, Colombia. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12020054

Jiménez-García WG, Arenas-Valencia W, Bohorquez-Bedoya N. Violent Drug Markets: Relation between Homicide, Drug Trafficking and Socioeconomic Disadvantages: A Test of Contingent Causation in Pereira, Colombia. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(2):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12020054

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiménez-García, Williams Gilberto, Wilson Arenas-Valencia, and Natalia Bohorquez-Bedoya. 2023. "Violent Drug Markets: Relation between Homicide, Drug Trafficking and Socioeconomic Disadvantages: A Test of Contingent Causation in Pereira, Colombia" Social Sciences 12, no. 2: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12020054