3. Results

3.1. Study One

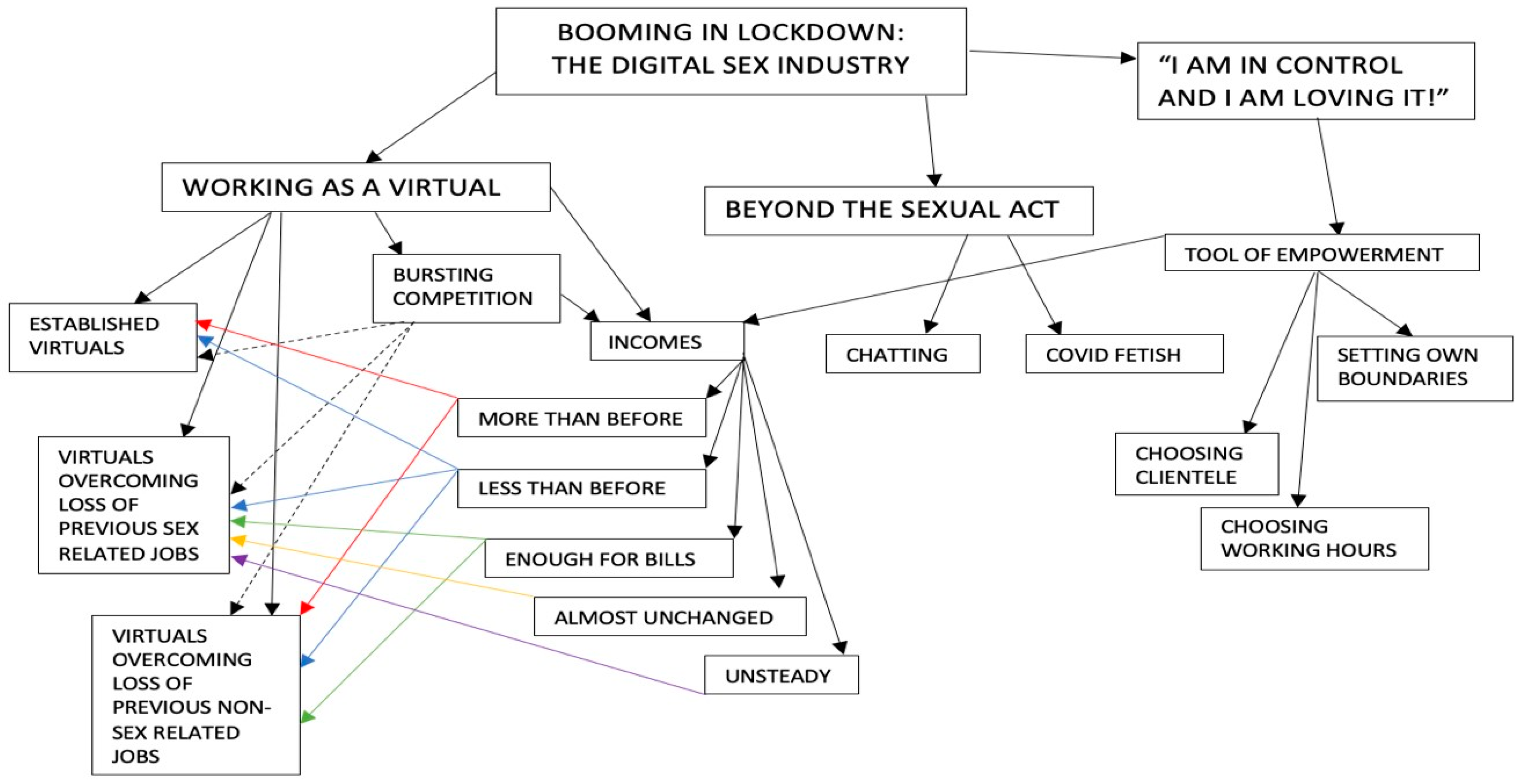

In the first study, a core category called ‘Booming in lockdown: The digital sex industry’ emerged along with three subcategories: ‘Working as a Virtual’, ‘Beyond the sexual act’, and ‘I am in control and I am loving it!’. The first subcategory ‘Working as a ‘Virtual’ comprised five properties which were: Established Virtuals; Virtuals overcoming the loss of previous non-sex related jobs’, and ‘Virtuals overcoming the loss of previously sex-related jobs’; ‘The bursting competition’ and ‘incomes’. From the property of ‘Incomes’ the following dimensions emerged: ‘more than before’; ‘less than before’; ‘enough for basic needs’; ‘almost unchanged’ and ‘unsteady’. The subcategory of ‘Beyond the Sexual Act’ included the properties Chatting and Covid Fetish (see

Figure 1). The subcategory of “I am in control and I am loving it!” included ‘A Tool of Empowerment’ as a property. This property comprised three the following dimensions: ‘Choosing Working Hours’, ‘Choosing Clientele’, and ‘Setting Own Boundaries’ (see

Figure 1). The term ‘Virtual’ is an in-vivo extracted from one of the Daily Star, 6 May 2020:

“We call them ‘the virtuals’ and some can make a lot of money”. The term indicates the range of sex workers working within the digital sex industry.

3.2. Booming in Lockdown: The Digital Sex Industry

The core category in Study One, ‘Booming in Lockdown: the digital sex industry’, encompassed the growth of the digital sex industry during lockdown and comprised both viewers and performers. The viewers were seeking entertainment and company to overcome the stressful circumstances, as reported by The New Statesman: ‘The COVID-19 crisis has accelerated the commercialisation of sexual intimacy, providing temporary relief not only from sexual frustration but also loneliness … the online porn industry has grown even larger’ (New Statesman, 4 November 2020). The increase in performers resulted from many newcomers who, following unemployment, joined established online sex workers or following the closure of in-person workspaces, as suggested by the following extract: ‘There has been a large spike in traffic to adult cam sites, along with a large influx of new models looking for ways to make money while remaining socially distant’ (Metro, 23 August 2020). The boom was experienced especially by performers working as cam models on webcam sites and also models creating content for OnlyFans, and can be seen in the following extract: ‘The business has been booming for webcam girls and OnlyFans models since the Covid outbreak sparked global lockdowns over a year ago …’ (The Sun, 6 May 2021).

3.3. Working as a ‘Virtual’ and Established ‘Virtuals’

It was possible to identify from the data the first sub-category of ‘Working as Virtual’. Three groups of sex workers were working as ‘Virtuals’ during the lockdown. With the onset of the pandemic and the consequent restrictions, online sex workers could continue their job as before with many women seeing an increase in their clientele. Cam girls were able to work from home and perform sexual acts for their paying viewers using platforms such as AdultWork and LiveJasmine, as stated in one of the analysed news reports: ‘Cam girls and adult performers are enjoying a boom in business as quarantined customers make the most of their service’ (Daily Star, 15 March 2020).

Not all veterans were, however, able to keep working while staying home, as they were living with other family members. To provide an alternative workplace, one web company gave digital sex workers much needed equipment, as the Metro reported: “… over in Columbia, an adult webcam company has taken things a step further by supplying its cam girls with plastic pods to work inside. These feature everything needed for the women to do their job; a laptop, bed or couch, and, of course, a webcam, with each room and the equipment cleaned and sanitised after use”. (Metro, 23 August 2020). This way, they could keep receiving income and providing for their families while respecting the pandemic restrictions.

3.4. ‘Virtuals’ Overcoming Loss of Previous Sex-Related Jobs

Among the women joining the digital sex industry, there was the property of established “offline” sex workers who previously performed sex services in a face-to-face fashion. The range included strippers and escorts, working in nightclubs and brothels, who turned to online services due to the social distancing and forced confinement of lockdown. The Birmingham Mail reported: “The worker, who is camming instead of escorting as a way of paying her bills amid the coronavirus lockdown, said: ‘I’ve had people who are talking to me but it’s been late at night, like 1 am, and they want me to type to them, instead of talking to them because their wife is there” (Birmingham Mail, 5 April 2020). Older sex workers who were not experts in the technology tools of media marketing sought assistance to advertise their sexual services on digital platforms. Such women were taught by younger sex workers the required skills, as suggested by this extract: “They’re teaching others over WhatsApp how to get into it, how to find clients, how to set up an account to charge credit cards, how to sort a webcam. For the women over 45, it’s not easy but you can always learn” (Daily Star, 6 May 2020). Ergo, not everybody found the shift to digital easy.

3.5. ‘Virtuals’ Overcoming Loss of Previous Non-Sex Related Jobs

The second property was composed of those people who became unemployed with bills to be paid and more free time due to forced home confinement, and for whom work options were limited. This included those who were either furloughed or their posts made redundant or, in the worst-case scenario, dismissed. Losing their job led many people, of whom the majority were women, to turn into digital sex work with the advantage of working from home. Lockdown caused an increase in financial difficulties that was overcome by seeking alternative occupations, as suggested by one of the tabloids: “The corona lockdown is hitting women’s pockets hard, with 17 per cent of female employees working in shutdown sectors such as retail and hospitality. According to support groups, many women across Scotland faced with no income have turned to camming as a short-term source of income …” (The Daily Record, 8 May 2020).

Some women were not only seeking an income to pay the bills, but they also took advantage of losing their previous jobs to pursue an option that would change their lifestyle: “A woman known as Roxie (not her real name) was one such person who lost her job during this difficult time … Roxie was working in marketing, but soon realised that if she wanted to keep paying for her bills she would need to find a different way to make money while in quarantine. She wasn’t too worried about this as she didn’t really love her marketing role to begin with, … the 27-year-old had always been interested in pursuing a career in the sex industry …” (Mirror, 5 May 2020).

Unsurprisingly, almost all the collected data gave a gendered representation of the financial issues experienced by women and without considering the role of men turning into online sex work to overcome the loss of income in the pandemic. Only one data source in our analysis could be found to the contrary in the following scenario: “It was through necessity, I needed an income. It wasn’t because I wanted to just get naked or post pictures of myself” says Mark. He lost his job because of coronavirus in March and began posting semi-nude images on a subscriber-based social network. “I applied for every single job I could find–all of the supermarkets, anything that was on the JobCentrewebsite–I applied for them all.” (BBC, 15 July 2020). In this case, the man turned to online sex work, not as a voluntary choice triggered by the idea of changing lifestyle, but rather he was pushed by lack of income to pay for essential needs.

3.6. Busting Competition in a Saturated Market

With the upsurge of women from different backgrounds working as ‘virtuals’, the digital sex industry experienced an oversaturation of the market. Such overload led to the property we identified relating to increased competition of ‘virtuals’ on different adult camsites and on OnlyFans in particular. Those in the digital sex industry faced intense competition as reported in The Guardian: “Once the pandemic came around and strip clubs started shutting OnlyFans became so oversaturated because it was just every single sex worker, or just anyone in general, realizing there was money to be made” (The Guardian, 22 December 2020). The addition, therefore, of newcomers to an established virtuals’ market created a perception of an oversaturation of the digital sex market, as this excerpt shows: “There has been a large spike in traffic to adult cam sites, along with a large influx of new models looking for ways to make money while remaining socially distant” (Metro, 23 August 2020).

The growing competition, however, impacted the financial profits of all the virtuals and one news outlet reported: “… she said that relying on income from the site is precarious as more users join and fuel competition.” (Wales on Sunday, 10 December 2020). Based on the data, the oversaturation of the market could be considered one of the factors linked to the altered financial incomes but it may not have impacted all the adult digital platforms in the same way.

3.7. Continuum of Earned Income Levels

Despite the assumption that the pandemic may have augmented financial resources for ‘virtuals’, a variance could be detected in the analysed articles as to the income levels earned and this was not always represented as increasing. It seems that some digital sex workers (both experienced and inexperienced) struggled financially during this period. The property of earned income was dimensionalised in the following way: more than before, less than before, enough for basic needs, almost unchanged, and unsteady. This continuum is explained below.

3.8. More than Before

For the majority of women who turned to online sex work for the first time, the incomes earned were greater than their previous earnings. The majority of newcomers who claimed to be earning more than before seemed to be the ones who were reported to enjoy the job the most and had sought a change in their lifestyle having previously been working in non-sex-related occupations. In one report, for example, Emma, who swapped her office job for digital sex work during the pandemic, declared an increase in her salary, which had tripled compared to her previous monthly pay: “In the first weeks of camming full-time I earned the same amount I would have earned in three months in my office job–about £3k” (The Scottish Sun, 6 December 2020). By contrast, only a few established ‘virtuals’ reported an increase in their incomes during the lockdown. For example, the Daily Star reported the following about an OnlyFans content creator: “Joslyn Jane from Miami is another OnlyFans star who sells sexy solo videos and “partner performances”. She says she’s currently making about $1700 (£1385) a week, up from her previous average weekly earnings of $1050 (£855)” (Daily Star, 15 March 2020. Interestingly, the data did not show previous ‘offline’ sex workers turning to digital who reported an increase in their incomes. Hence, not all the ‘virtuals’ were as fortunate in terms of financial gain from digital sex services.

3.9. Less Than Before

Some sources reported that digital sex workers, both established and novel, experienced a decrease compared to their pre-pandemic income. Women already working as ‘virtuals’ claimed that, compared to the period preceding the lockdown, they had a less clients as a consequence of the forced confinement and co-existence with other members of the family: “Virtual sex was expected to boom, but webcam girls and sex chat hostesses say their work has also dried up. One sex chat hostess said: ‘Most of my regulars are married blokes with nowhere to sneak off at the moment. There is no way they will be calling while they are stuck in the house with wives’” (The Sun, 14 April 2020). A similar outcome was reported by sex workers who previously worked as offline performers and lost their job due to the restrictions requiring social distancing regulations, as one stated in The Independent: Legal brothels have been shuttered for nearly a year, leaving sex workers to offer less lucrative alternatives like online dates… (The Independent, 20 February 2021). In another example, a nightclub sex worker, Camila, reported in one of the tabloids that her calls would provide financial gain but the income were barely comparable to her previous earnings in ‘offline’ sex work: “The calls bring in something, obviously it’s not the same and the money is not even what it would have been on a bad day before but it’s something” (Daily Star, 6 May 2020).

3.10. Enough for the Bills

Several of the extracts contained reports that newcomers would earn enough to pay for the bills, regardless of their previous occupation. Potentially, such an outcome could be related to the fact that turning online and create content for a wage was not accompanied by enjoyment but rather by the need to ‘survive’. In one broadsheet article interviewing an offline sex worker who used to perform in one of the Nevada brothels, they were reported to say: ‘At this point, I am able to survive. I am able to pay my bills. I’m able to put food on the table, but I have had to dip into my savings’ (The Independent, 20 February 2021). Similarly, another broadsheet article, this time related to a ‘virtual’ who lost a non-sex-related job, clearly stated that incomings of digital sex workers are not always leading to the expected financial lifechanging: ‘Now she works about six hours a day taking lingerie photos and marketing herself on social media. In the past month she has earned £170–about £6 a day. “It’s harder than I imagined it would be,” she said. “It’s not as easy as people on the internet make it seem”. The money she makes is what she needs to live’ (The Times, 26 July 2020).

Only a few of the news outlets reported the incomes of the established ‘virtuals’ to be similar to before the pandemic, as one article stated: “Cam girls are struggling to keep up with the increased client load of lockdown, but even before the increased traffic, they were pulling in big bucks” (Daily Star, 22 April 2020). Others also reported the precarity of the work as related in The Guardian: ‘It was about a year before I really started seeing any type of income and even then it’s not like a steady incomes or anything’ she says. “I can have some days where (I) only make maybe $10, and then (I) can have weeks where (I’ve) actually cashed in about $500.” (The Guardian, 22 December 2020).

The above findings suggested a divergence in the way ‘virtuals’ perceive their incomes and that their perception relates to their income and type of work prior to the pandemic. Those not in sex-related occupations reported an increase but those doing in-person sex work previously saw a drop in income as the online market became more saturated during lockdown. The findings suggest that turning to online sex work was a time-consuming occupation and it did not meet the financial expectations assumed at the outset if someone was used to an in-person sex-related income.

3.11. Beyond the Sexual Act

Chat, Companionship, the ‘Girlfriend Experience’, and the Illusion of Intimacy

The clients’ requests were reported as extending beyond the performance of sexual acts and this constituted a further sub-category of the data. Because of imposed restrictions such as compulsory social distancing, forced quarantine, and isolation to contain the spread of the virus, people started to seek company and alternative entertainment to overcome adverse feelings, as reported by the following extract: ‘The COVID-19 crisis has accelerated the commercialisation of sexual intimacy, providing temporary relief not only from sexual frustration, but also loneliness’ (New Statesman, 4 November 2020). Many clients sought to chat or have a conversation with the ‘virtuals’ and many interactions with clients were based on conversations unrelated to sexual performance but rather centered on human companionship. A majority of sources reported that ‘chatting’ was a service offered to regular clientele as described in the New Statesman: ‘OnlyFans offer what should best be understood as the “girlfriend experience” of porn. Successful creators sell not just explicit content, but also the impression of authentic personality. Creators are expected to message users privately, and perhaps remember their birthdays, or their children’s names, thus offering the illusion of intimacy’ (New Statesman, 4 November 2020). Beyond this classic example of emotional labour, some ‘virtuals’ went beyond engaging in conversation during the digital paid time and were reported to be checking on their regulars’ mental and physical health, as stated in: “… during lockdown I have been texting some of them regularly to see how they are doing and if they have someone who is able to get groceries for them. They are too far away from me to help, but it’s important for me to know that they are OK, and it gives them someone to talk to for a bit …” (Metro, 22 May 2020). This was echoed in The Telegraph, which reported: “Successful creators sell not just explicit content, but also the impression of authentic personality” (The Telegraph, 29 August 2020)

3.12. Covid Fetish

Some clients sought more unusual trends to entertain themselves and from the data emerged previously unknown kinks. In some of the reports, it was stated that clients were requesting a virtual service directly related to the pandemic that was identified as a Covid fetish, as described in this excerpt: “… she has regular punters who ask her to sneeze and cough on camera for up to 20 minutes at a time or even ask her to wear a face mask throughout their steamy calls.” (The Sun, 6 May 2021). So, it can be seen that there was a continuum of requests from chatting to Covid fetishes that went beyond any sexual acts.

3.13. ‘I Am in Control and I Am Loving It!’

While financial need was the main reason to turn to such a challenging industry, other reasons emerged such as the pursuit of a different way of life that afforded a higher income and more control. And in the category that emerged from the data in the final sub-category in Study One, i.e., the virtual sex workers’ perception of being in control of their job and loving that control. It appeared that the virtuals who were achieving great financial gain were the ones who enjoyed the lifestyle provided by virtual sex work and took their time to create high-level content for their clients.

3.14. Virtual Work as a Tool of Empowerment

Many women were reported as perceiving their digital sex work to be a ‘tool of empowerment”. This meant not only being economically independent, but the increasing self-confidence ‘virtuals’ gained by setting their own boundaries, scheduling their work hours, and choosing their clientele. The following excerpt describes how one woman benefitted from the new work lifestyle: “And for Jah Bella it’s been life changing. ‘I have a history of anxiety and depression and I have a lot more freedom to live life,’ she says. ‘I control my work hours. I don’t need to feel guilty for staying home … if a man abuses me or harasses me [online] I can just block them instead of having to deal with them every day.’” (The Guardian, 22 December 2020). Additionally, some women were reported as relishing being able to set their own boundaries, and being able to control and choose the genre of performance, as in: “I only go topless, and I’m in control of what I do, so I don’t have to do anything I don’t want …” (The Scottish Sun, 6 December 2020). Others who started working as digital sex workers when in urgent need of an income reported that they would likely continue the work: “I wouldn’t have made it if it wasn’t for the pandemic, but now I don’t know when I’ll stop.” (The Times, 26 July 2020).

The notion of empowerment was characterised by the ability to set their own boundaries, be in control of one’s working hours, choice of client, and the type of content uploaded onto the site. It was a complex balance, as reported by the following excerpt: “Women have told us clients are becoming more demanding and financial pressure is making women feel they can’t set boundaries they would want to” (Daily Record, 8 May 2020). The feeling of empowerment was thus disrupted if the main reason for joining was the necessity of incomes, and if they felt pressured to shift boundaries.

3.15. Study Two

The core category which emerged from the data in Study Two was that of ‘Increased engagement’ which was was observed in three areas: the sites involved in provision of online sex services; new digital sex workers joining the industry; and those who were involved in provision of online sex services prior to the pandemic. These sub-categories were called ‘sites’, ‘newcomers’ and ‘established online sex workers’, respectively. The sub-category ‘sites’ consisted of one property: ‘the booming business’, whereas the sub-categories ‘newcomers’ and ‘established online sex workers’ each comprised three properties. For ‘newcomers’, these properties comprised ‘reasons for joining online sex industry’, ‘perspectives of online sex work’ as well as ‘transition from direct/indirect sex work to online sex work’. For the sub-category ‘established online sex workers’, the properties included ‘increased workload’, ‘increased competition’ as well as ‘increased desire for intimacy and companionship’’. The relationship between these concepts is illustrated in

Figure 2 below:

3.16. The Booming Business

An influx of both new subscribers and content creators on the various online sexual content sites was evident in the majority of the newspaper articles. This increase was noted in statements such as “The coronavirus pandemic has driven a huge increase in traffic to webcam sex sites” (Daily Star, 8 May 2020). Some articles provided specific evidence to quantify the change which occurred during the pandemic, for example, in: ‘At CamSoda, the number of new viewers to the site has doubled this year when compared with early 2019, according to the company.’ (Independent, 19 April 2020). Other news outlets noted specific increases in sales: “The website has seen a 15% spike in video sales since the outbreak of coronavirus and a ‘steady rise’ in the use of its streaming service.” (Daily Star, 20 March 2020). In September 2020, New Statesman reported: “Like many other sites, the growth of OnlyFans was sent into overdrive by lockdown. As its popularity surged—traffic to the site more than doubled between March and August—it received prominent media coverage from BuzzFeed to the BBC. By May, OnlyFans had racked up more than 24 million registered users.” (New Statesman, 18 September 2020).

In December 2020, BBC announced the most recent statistics with regards to OnlyFans’ explosion in popularity during the pandemic: “The site claims users have risen from 7.5 million in November 2019 to 85 million–with 750,000 so-called content creators.” (BBC, 9 December 2020). A continuous growth in the number of subscribers as well as content creators was reported by OnlyFans throughout the pandemic. In April 2020, an article in The Independent stated: “OnlyFans (...) reports a 75 per cent increase in overall new sign-ups –3.7 million new sign-ups this past month, with 60,000 of them being new creators.” (Independent, 19 April 2020). This increase in number of webcam models joining camming sites was reported for other sites including CamSoda, ManyVids as well as Chaturbate as seen in this excerpt from The Independent: “Daryn Parker, the vice-president of CamSoda, says there has been a 37 per cent increase in new model sign-ups this March, compared with last March. For the same period, Bella French, co-founder and CEO of ManyVids, another camming site, says that there was a 69 per cent increase in new model sign-ups.” (Independent, 19 April 2020). This reportage was corroborated by the BBC in: “US-based livestreaming site Chaturbate has reported a 75% rise in the number of sex workers signing up since the outbreak began–an increase faster than the rate at which audience traffic is rising.” (BBC, 7 April 2020).

3.17. Newcomers

The next sub-category was that of newcomers, which was divided into three properties, the first of which was ‘reasons for joining online sex work’.

3.18. Reasons for Joining Online Sex Work

The majority of articles cited the main reason for entering online sex work as the need for an alternative income, often following loss of work due to the lockdown. For some women, particularly those who were mothers, the decision appears to be fuelled by desperation, caused by inability to pay bills and provide for their families, as in: ‘Gracey found herself unable to work when the UK was plunged into lockdown in March last year. She found herself with no cash and the bills were mounting up so she turned to OnlyFans after a friend suggested it to her. “I was panicking,” she said. “I had all these bills to pay and no income. It was stressful’ (The Mirror, 30 March 2021).

Although the pursuit of income seemed to be a primary motivation for the majority of those who became involved in online sex work in the midst of the pandemic, others had secondary motivations. For Rose, a student, turning to digital sex work was motivated by both the loss of her job in hospitality and her health concerns related to the virus:

“Rose, which is not her real name, turned to online sex work after she effectively lost her job in a restaurant as a result of lockdown. She says she is also classed as high-risk in relation to COVID-19, so working through a subscription website was “safer” and “financially easier”.” (Sky News, 10 September 2020). In another media outlet, Pea, also a student, found digital sex work offered source of entertainment, convenience, as well as freedom in addition to an income. She was reported to say:

“I started at the beginning of lockdown because I was bored and skint. (...) it fits in nicely with uni work. It’s just a part-time job with a difference. I can just do little photoshoots whenever I want.” (Mirror, 11 April 2021). Such decisions were echoed in the regional press reportage, with decisions about online sex work motivated by financial gain, as well as companionship and improving self-esteem:

“[Lockdown has mean] it has been very hard finding jobs or even coping with hardly no support. I turned to [advertising to sell sex] because I got the cash to help me and the attention that people wanted me as I was very lonely.” (Sunderland Echo, 4 December 2020).

1While the bulk of narratives in the articles revolved around loss of job or inability to work due to the effects of lockdown, there were women newcomers to the work who had made a conscious decision to quit their jobs in the midst of the pandemic and digital sex services became their main source of income. This choice appears to be primarily motivated by lack of previous job satisfaction, with financial motivation being secondary. For Rachel, an ex-data analyst, it was the pursuit of a ‘better work-life balance’ (BBC, 9 December 2020). For Cora, an ex-nurse who was previously involved in online sex work in her free time, it was an opportunity to follow her ‘dream job’ (The Scottish Sun, 11 February 2021) as a full-time webcam model.

3.19. Perspectives of Online Sex Work

Newcomers’ perspectives on online sex work are presented positively as well as negatively. Aspects of online sex work highlighted by the newcomers in the articles included the perks, which for many included significant financial gain, often achieved in a short period of time. The actual income generated through provision of online sex services differed between the women, ranging from ‘£400 a month’ (Mirror, 11 April 2021) to ‘more than £2,800 in four weeks since launching (the) page’ (BBC, 9 December 2020). Additionally, newcomers to online sex work often made much more money in their new job than in their old one. According to Cora, an ex-nurse: “In front of the camera I could earn three to five times more.” (The Scottish Sun, 11th February 2021). An extreme example is Gracey, who made “more than twice her annual £18,000 hairdresser income in one month.” (Mirror, 30 March 2021).

In addition to reports of financial gain, the advantages of the provision of digital sex services for some women included increased confidence. In many reports, women had no regret and even expressed being liberated by their new job, claiming a sense of empowerment and freedom. This was particularly striking in the account on Sky News: ‘The woman, in her 20s, says she “loves” her new source of income and refers to it as “one of the best things” she has ever done. “I used to be anorexic and now I am the most body confident I have ever been in my life. (...) (It’s) very, very liberating. I’m in control of my own content and of my own body and I can do whatever I want with it because you can set your own levels’ (Sky News, 10 September 2020).

While for some women online sex work was perceived as safe (or mostly safe), for others it presented risks, particularly of being recognised by someone personally known to them as well as exposure to criticism. Some women therefore decided to keep their new job a secret from their family members, perhaps in an effort to avoid disapproval as expressed in this report: ‘“I think the main risk to me was in going public, you’re opening it to people you may know in real life and not everyone is going to agree,” she said. “You have to be strong enough to know that you more than likely will come across criticism, it’s not as easy to brush off for everyone, nor is it easy to defend yourself.”’ (BBC, 9 December 2020). Criticism from relatives and acquaintances was not the only fear as online sex workers may be targeted by individuals for whom their mere existence is problematic. This was seen in the reportage in The Mirror: ‘Some people, and it’s a lot of men, have said horrible things online. Some people have even subscribed to my page, and paid to do so, just to tell me they don’t like what I’m doing’ (Mirror, 30 March 2021). Similarly, one newcomer reported that it was a lack of support which prompted her to engage in online sex services in the first place: “It did make me feel dirty, that I had to turn to this as it shouldn’t be that way. People should have more support, I was reaching for help but no one was helping me” (Sunderland Echo, 4 December 2020). This exemplifies the notion that online sex work was the only financial safety net for some at the beginning of lockdown.

3.20. Transition from Direct/Indirect Sex Work to Online Sex Work

A rise in involvement in online sex work was also noted in reports of those who were already in sex-related services prior to the pandemic. The shared rationale for pivoting their work online was predominantly financially motivated, as sex workers were left unable to engage in direct in-person services following lockdown. For some, this switch was their first foray into digital sex work as this extract in The Independent shows: ‘While working as a stripper in Oregon, Kelpie Heart had long thought about taking her work online. Then the coronavirus pandemic led to bar closures, and she found herself out of work. So, for the last month, Heart has begun streaming performances from home, doing one live show a week’ (The Independent, 19 April 2020). Others were already involved in online sex services in addition to their direct sex work; however, the majority of their income was generated though provision of direct sex services: ‘“The virus is a disaster for client-facing businesses–and sex work is no different,” says Goddess Cleo, a dominatrix from London. “Most of my income is generated from one-on-one sessions and events. I [normally] only make a bit of money through online avenues.” But like many others, Cleo has switched focus to digital since the lockdown came into effect’ (BBC, 7 April 2020).

A worker’s previous involvement in the sex industry appeared to facilitate the transition between direct contact sex work and the provision of online services. For many, however, the transition was much more complicated. Online sex work can require more patience from the sex worker and be more time consuming than one-on-one meetings. Furthermore, it may call for a somewhat different set of skills; marketing services is a necessity to achieve success online, as this extract showed: ‘“It’s not about flashing ya nipple and earning big bucks”, wrote UK sex worker Gracey on Twitter. It takes ages to gain an online following and even longer for [them] to buy your content. (...) The marketing requires so much effort, it is unreal,’ (BBC, 7 April 2020).

Online sex work is often more public than sex work requiring direct contact with customer. As a result, the anonymity of many sex workers can become compromised, as the following extract shows: “Those making money from sex work in person before the pandemic went on OnlyFans and realised you have to produce so much content to make money, and it’s really hard to do that without including your face and voice in videos.” (The Scottish Sun, 11 April 2020).

3.21. Established Online Sex Workers

The final sub-category in Study Two pertained to the experiences of established online sex workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. There were three properties of this sub-category the first of which was ‘increased workload’.

3.22. Increased Workload

The rise in demand for online sex services, particularly at the beginning of lockdown was highlighted in numerous articles. The increase in clientele was observed by many established online sex workers and often led to increase in income: Ava Moore said that the lockdown had been positive for her business, as more people watched live shows and interacted on social media. (...) Her business has grown by 30% since the lockdown (...) March has been Ava’s best month since 2017 (Daily Star, 21 April 2020). Increased income was not always a direct outcome of the increased demand, however, and some digital sex workers reported a much higher workload than before pandemic, but without the concomitant financial gain, as one report shows: “I’m meeting a whole bunch of people more frequently than I normally would, but there’s not much more money” Kane says’ (The Independent, 19 April 2020).

As the availability of online sex workers increased during lockdown for some it was an opportunity to invest more time and effort into the development of their business, as one report shows: Allie Awesome, a cam model, works around 60 h a week, she says. Her work day begins right after waking up, when she looks through her social media notifications and checks in on her customers. (...) And as social distancing leaves her stuck inside, she has found herself working more than ever. Though she tends to work directly with individual customers through Discord, a chat app favoured by video game players, she’s now using other platforms more, including Chaturbate, OnlyFans and Skype. (Independent, 19 April 2020). While most online sex workers took advantage of the increased demand for their services, others were mindful of the need to balance this new increased demand with her own work life balance as this extract demonstrates: ‘Kat Aluna said that she had more than 300 fans watch her live show this week. She said: “That’s pretty big. But I don’t necessarily want to ride this wave–I’m putting myself first, because I don’t want to turn into a sex robot and stop listening to my body”’ (The Daily Star, 21 April 2020).

3.23. Increased Competition and Marketing Trends

Established online workers reported an increase in the number of newcomers joining the industry and expressed concerns at the competition this created, for example: “Online dominatrix Eva de Vil says: “There’s lots of new girls joining the scene right now–or offline sex workers moving online to help with finances.” (...) UK sex worker Lizzy says camming has become even more competitive since the pandemic began (BBC, 7 April 2020). The heightened competition due to increased numbers of digital workers meant that many established online workers had to work more hours or cut prices, and one report explained: ‘Cariad said the increase in the number of people using the platform had led to more competition, meaning ‘you definitely have to do more’ (BBC, 9 December 2020). In many cases, ‘doing more’ meant lowering prices with a hope of attracting more custom, one worker was reported thus: ‘“I’ve seen quite a lot of girls running discounts,” Eva says. “We’re sensitive to [customers’] drop in income”’ (BBC, 7 April 2020).

Online sex workers reportedly noticed a change in customers’ spending habits, specifically an apprehension to pay for services, as this extract states: “Chloe Sanchez has found that customers now expect her content to be free, because sites like Pornhub have made access free since the lockdown began.” (Daily Star, 21 April 2020). In another report, clients were not paying as much: “In Kane’s experience, new viewers aren’t tipping as much as they typically would.” (The Independent, 19 April 2020). Lastly, one digital sex worker noticed that her customers were seeking sexual release more strongly than before the pandemic and she also observed a change in the demographic of customers accessing her services. “The model has also met a lot of men living alone. She explained in a Daily Star interview: “I’m not finding guys are more kinky, however they are certainly a lot more sexually frustrated. “I can tell they are gagging for it a lot more now. I’m also coming across a lot more married men in lockdown.” (Daily Star, 19 July 2020).

For others, however, increased competition meant increased marketing and more maintenance of their social media presence as well as the creation of special content, all of which led to increased workload, as the sex worker Ava said in this extract: “Since the lockdown, I’ve been spending much more time on social media. I can show how available I am at the moment and tease my audience with special offers—a new morning live show and a Snapchat special for the lockdown. The Snapchat show lasts five minutes, costs [Euro]15 £13 and allows married men to wander off and pleasure themselves quickly.” (Daily Star, 21 April 2020). This shows the reported marketing response by established workers who recognised quickly how to respond to the changing market for their services.

3.24. Customers’ Increased Desire for Intimacy and Companionship

Established online sex workers were reported as noticing a change in customers’ requests and desires during the pandemic. This change often pertained to the type of relationship the customer sought with the worker. Several digital sex workers particularly noticed increased desire for intimacy and companionship, as in this report: ‘I have never had so many cam-to-cam requests. Since this has all started, everyone wants cam-to-cam. It’s as if there is that extra connection of face to face, which is something that we are getting less of in our day to day life under quarantine. For me, every single person has said, can we cam to cam, whereas before it was only 20–25%, but now everyone wants to do that’ (Metro, 2 April 2020). This was supported in another report: ‘She said that private requests have also gone up by 30%. Chloe added: “The other day, two guys asked me to stay fully clothed–they just wanted to talk.’ (Daily Star, 21 April 2020), and another was reported thus: ‘I’ve found that I’ve had an influx of silent phone chat requests more than anything.’ (Metro, 2 April 2020).

Online sex workers also commented how their interactions with clients reflected those in the rest of the community stating that COVID-19 had become the main focus of their conversations. One digital sex worker spoke about her experiences with new customers as well as key workers: “‘There are lots of new people I’m talking to which is great, so it’s nice to have new conversations with people,’ Red_Delicious adds. They’re all working from home and the topic is always coronavirus, isolation and how everyone is in it together. It’s interesting because it’s almost become a focal point. (...) I’ve been speaking to a lot of frontline key workers (...) a lot of them have said how nice it is to talk to someone and how I brighten up their day” (Metro, 2 April 2020). Another digital worker described her experiences with regular customers, expressing how going through difficult times together increased a sense of camaraderie between the workers and their clientele: “‘I think the loveliest part has been regular chatters coming in frequently to ask about my wellbeing and to make sure I’m ok (...) ‘The coronavirus has been the main topic of conversation for a few weeks now and has made us all feel like we’re a community again going through the same trials and tribulations sharing opinions and coping mechanisms. It’s great knowing we are all helping each other through this time.’” (Metro, 2 April 2020). This reflects a change in client needs to more personal, rather than sexual, intimacy with a need for silent companionship at the extreme end of the continuum.

4. Discussion

The findings from both studies show the reported impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the digital sex industry. A trend of significant growth in users in webcamming in general and on OnlyFans in particular was reported across all media sources. The pattern of increased engagement in online sex work at the start of the pandemic was such that it was described as ‘booming’. For the sex workers reported in the news articles, their experience of this boom depended on their previous occupation. For those moving into sex work for the first time, it represented an increase in earnings, for those already in sex work but moving online for the first time it represented a loss. Those already in online sex work noticed increased competition and had to pivot their marketing and services accordingly. This pivot took a variety of forms but included, for example, more social media marketing, or earlier and shorter videos as content creators took account of clients’ working from home situation. The findings across the two studies showed the experience of newcomers as they transitioned to online sex work as well as the perceptions of experienced online workers who charted the change in client requests. These requests spanned silent companionship, to chatting, and more extreme requests and fetishes like the Covid fetish.

In Study One, it was possible to identify two groups of newcomers joining the digital sex industry and the established community of ‘virtuals’. Those were either sex workers performing direct sex services, such as escorts, or new users who lost their jobs or wished to replace their previous employment with digital sex work. The market saturation led to an increase in online competition among ‘virtuals’, which seem to be related to the changes in income earned during the pandemic. While the perceived revenue was not always as high as expected, perceptions varied depending on the type of jobs the ‘virtuals’ were performing prior to the shift into digital sex work. This finding is in line with

Jones’ (

2020) results, suggesting that incomes are unequal among ‘virtuals’ but that in many circumstances, new users previously working in non-sex-related jobs were more likely to perceive their current incomes as better than their previous occupations.

A new concept that emerged from the study concerned the type of services performed by the ‘virtuals’, which did not involve sexual acts. Indeed, it was found that many of the ‘virtuals’ would be asked simply to chat with their clients and offer an authentic persona. The findings support

Nayar’s (

2017) research suggesting that webcamming is not merely related to sexual encounters, since clients are often seeking companionship, hence someone to talk to. Furthermore, in line with

Nayar’s (

2017) findings, providing authenticity is important for webcam models in order to meet clients’ expectations. This finding supports

Hall’s (

1995) formative findings of women on fantasy phone lines acting to gain patriarchal privileges of economic power.

The reports show that online sex workers perceived the job as empowering due to the ability to set their own working hours and choose their clientele, but also the ability to apply personal boundaries in relation to the type of service to be performed. Such empowerment was often linked to growing self-confidence and these findings are in line with

Henry (

2018), who reported that many ‘virtuals’ claimed that being a digital sex worker helped to develop and improve mental health issues and low self-esteem.

The concept of empowerment, however, was not shared by all ‘virtuals’, especially those who turned to digital sex work as temporary urgent alternative work to overcome financial hardship. Such women were often not able to set their own boundaries, for example, because of the economic distress that emerged amid the coronavirus pandemic. This supports previous findings, e.g.,

McCracken and Brooks-Gordon (

2021) who illustrate the complexity of empowerment. Although many women feel empowered and safer doing online work than when delivering in-person services, due to the ability to turn off the computer or blocking the countries or viewers (

Henry 2018), pursuing such a career may still be challenging. Those challenges may emerge, for example, when lacking the technological ability necessary to have a successful career.

Velthuis and Van Doorn (

2020) suggested that the job requires performers to have specific tech skills and present to the client an authentic persona that provides a high-quality interaction.

In Study Two, the findings of increased engagement develop the theoretical model further to show added nuance behind the increase in the number of models joining webcamming sites as well as increase in number of new viewers. Additionally, the expansion of OnlyFans in terms of subscribers and content creators was highlighted by the press throughout the pandemic. These findings correspond with those of

Lykousas et al. (

2020) but while their study focused on only one website, the current study provided novel findings of the increase in users observed across multiple platforms. Furthermore, the study explored reasons for entering online sex work in the midst of the pandemic and revealed that financial motivation was the most salient among new online sex workers. This was unsurprising as pre-pandemic research on motivations for entering the online sex market provides similar findings (

Jones 2020). The ability to get work immediately, cited by many newcomers, is simply more marked in the pandemic experience. The analysis of the articles also revealed that many newcomers also had secondary motivations such as health concerns, boredom, convenience, loneliness and desire to increase one’s own self-esteem. Such incentives appear novel and may be perhaps specific to the experience of the pandemic and social distancing, as the literature mostly highlighted motivations in the form of autonomy as well as experiencing pleasure and exploring one’s own sexuality (

Jones 2020). The findings also suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic presented an opportunity to change career paths for some new online sex workers who were unsatisfied with their previous jobs. This echoes the experience of other occupational groups during the pandemic and perhaps their new employment will provide them with higher satisfaction, as pre-pandemic research suggests that individuals involved in provision of online sex services generally experience high levels of job satisfaction (

Jones 2020).

Our analysis revealed that not only did many newcomers experience advantages such as significant financial gain, increased confidence, liberation and sense of empowerment but they also faced risks in the form of being outed as well as criticism and/or harassment. Such findings largely replicate those of pre-pandemic research on online sex work (

Jones 2015,

2020;

Sanders et al. 2018), in which both risks and benefits of online work were examined. Because the anonymity of those in sex work can be put into jeopardy by entering online avenues

Brouwers and Herrmann (

2020) suggested that this may be a factor which previously prevented many sex workers from involvement in the provision of online sex services. The current study did not find evidence that newcomers had been victims of online aggression such as doxing or capping (

Jones 2015,

2020). These issues were not mentioned in the interviews or the articles and may well be an artifact of the journalist, rather than researcher, interviews.

The pandemic-driven transition from direct and indirect forms of sex work to the provision of online sex services was a new finding from the study. The analysis revealed that many sex workers turned to digitally mediated sex work in order to make up for the loss of income they experienced due to the effects of the pandemic, and these findings correspond with commentaries by

Brouwers and Herrmann (

2020) and

Döring (

2020). The transition from sex work requiring direct contact with customers to provision of online sex services was a complex one. The analysis revealed that indirect digital sex work could be more time consuming than other forms of sex work and marketing skills are essential to become successful and profitable. Similarly, evidence from the pre-pandemic literature suggests that building a brand and following in digital spaces is laborious, and it may take over a year to become prosperous (

Jones 2020).

The analysis of the press coverage revealed that established online sex workers experienced an increase in demand for their services during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is a novel finding and adds to research into the effects of the outbreak of the virus which evidenced increases in other online areas, such as sales of sex toys and consumption of pornography (

Arafat and Kar 2021;

Zattoni et al. 2020). Furthermore, it has been found that many of the established digital sex workers increased their workload during lockdown in order to accommodate an increase in demand, with an exception of one worker who worried that increasing her workload could lead to negative physical and psychological consequences and set her work boundaries accordingly. The analysis of the press articles suggested that the majority of the established online sex workers invested more time into interaction with their customers as well as overall development of their business. Although for some of the online sex workers this led to increase in income, others found themselves working more but not earning any more than before the pandemic. This finding echoes pre-pandemic research in which high precarity of incomes in some forms of online sex work has been highlighted as an outcome of an inconsistent number of customers and working hours (

Sanders et al. 2018,

2020). However, precarity of incomes may have worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic, as salaries of many consumers of online sex work were likely affected by the outbreak of the virus, which may have resulted in them becoming more frugal. This too is a novel finding and adds to the literature on the market economics of sex work (e.g.,

Brooks-Gordon et al. 2015;

Cunningham and Kendall 2011) to increase our understanding of the economic nuances behind the phenomena observed.

Accordingly, the study explored the competition within the online sex industry during the COVID-19 pandemic as presented in the analysed articles. Although high competition in some areas of the online sex market has been highlighted in the pre-pandemic research (

Jones 2020;

Van Doorn and Velthuis 2018), the current study provides novel findings, suggesting that this industry was subjected to greater rivalry during the pandemic, which can be ascribed to the arrival of newcomers and increased availability of many digital sex workers. Moreover, the analysis of the press articles allowed us to identify some of the strategies adopted by the established online sex workers in order to attract customers. These included lowering prices, increasing their workload by maintaining a regular social media presence, creating additional content, and different, shorter content in recognition of client time constraints. These strategies may not be exhaustive and should be investigated further, as pre-pandemic research argued that in order to stand out from the crowd, digital sex workers may engage provision of more extreme and sexually explicit content (

Van Doorn and Velthuis 2018;

Sanders et al. 2018;

Jones 2020). Our research shows a more subtle modification to working practices.

Lastly, the analysis of the press articles enabled the exploration of the changes in customers’ attitudes during the pandemic. The findings suggest that customers of established online sex workers experienced increased desire for intimacy and companionship, evidenced though increased requests for private interactions as well as interactions involving camera-to-camera and silent companionship in calls. Furthermore, many digital sex workers discussed the effects of the pandemic with their clientele, which increase bonding and created a sense of camaraderie. Although the importance of emotional labour in some forms of online sex work has been already highlighted in pre-pandemic research (

Hall 1995;

Sanders et al. 2020;

Jones 2020), the findings of the current study suggest that the role of emotional labour in provision of digital sex services may be even greater during uncertain times and in extreme conditions, such as in the midst of a global pandemic. Additionally, changes in customers’ spending habits, increased frugality of consumers of online sex services could be potentially explained by the global economic crisis caused by the pandemic. Moreover, one online sex worker noticed greater desire for sexual gratification amongst her customers, who increasingly included married men as well as men who live alone. Likewise, evidence from the literature suggests that lonely men were more likely to use sex as a coping strategy during the early stages of COVID-19 pandemic (

Gillespie et al. 2021;

Cocci et al. 2020) which could potentially explain the increased need for sexual release.

Besides companionship and chatting, it also emerged that viewers were requesting unusual performances, such as the Covid fetish in which sex workers were required to sneeze or cough on the camera. It has been argued that performing unusual services could have positive effects on the lives of performers and their clients, as it pushes sociocultural boundaries and allows moments of freedom from the ‘regulatory forces in society’ controlling individuals’ sexual behaviour (

Jones 2020). Therefore, the emergence of a Covid fetish may be perceived as a need to escape from some of the restrictions imposed amid the COVID-19, such as wearing a mask to avoid people from spreading germs through coughs and sneezes. This is a totally novel concept and a new finding that adds to the literature on sex work and on fetishes in particular.

4.1. Strengths

Newsmedia offers a valuable source for analysis with digital and hard copy editions as well as reach across social media, narratives and counter-narratives are forged in news media. They offer an immediacy that many ‘hindsight’ research interviews cannot. Researchers of sex work understandably make attributions about what is written in the press about sex work so it is important to analyse the press coverage itself, not least to prevent fundamental misattributions about what is said or written about in the news media—this is a critical strength of this study. The research did not seek to explore whether the coverage was positive or negative per se, but rather, by utitilising the immediacy of content made in real time, it sought to harness the content itself to show in a systematic way what that reportage contained. In doing so, this research provided many novel findings, outlining numerous ways in which online sex work was affected by a global pandemic.

A further strength was the use of two researchers, to use the potency of pluralistic, mixed methodologies (

Frost et al. 2010) in the analysis of a parallel (but not identical) set of reports. The emergent Grounded Theory model provides real insight into the deployment of emotional labour, and the roles it plays, to add to the extant literature on emotional labour (e.g.,

Hall 1995;

Parvez 2006;

Flubacher 2019) to expand our understanding of emotional labour in such contexts.

The current study is aware that the use of newspaper reports may limit the parameters of the information regarding topics related to digital sex work and, for example, the lived experiences of ‘virtuals’ may differ from those when engaging in an in-depth interview with a researcher experienced in sex work research, and it makes no claim for that. The study will provide a valuable comparator to in-depth interviews with sex workers so that their representation by researchers and journalists can be compared. The study does, however, reflect the growing awareness of the burgeoning industry in the mainstream press and the mediatisation of sex work.

4.2. Limitations

The findings of this study are also subjected to certain limitations. Firstly, as the study focused only on press articles released in the UK, and while the news media used data from online sex markets in a variety of other countries it is possible that the current findings are specific to the news media operating within the UK and in the English language. Future research could therefore investigate whether mediatisation of the digital sex industry is the same in other countries and other languages. It is important also to note the relative lack of representation of men and transgender sex workers involved in online sex services observed in the analysed press articles. Although women tend to predominate digital sex industry, an analysis of the experiences of men and transgender online sex workers could add depth to the current findings.

This study found only one report of a male worker, yet evidence of those involved in male sex work (

McLean 2012;

Morris 2021;

Brooks-Gordon and Ebbitt 2021) is strong and found to be more ‘incidental’ in its inception. As suggested by

Henry and Farvid (

2017), it is important to consider the experiences of minority groups within the sex industry and future research could include experiences of male digital sex performers during the pandemic. Future investigations could therefore balance out the inherent cis/het bias in past findings.

Moreover, as the analysis in the current study was based on reportage obtained from newspaper coverage, the reliability of information can be compromised by varied journalistic standards and perspectives. Additionally, even though steps were taken to provide an overview of the effects of COVID-19 on many forms of online sex work, the analyzed articles centered around webcamming and sexual content creation, largely leaving out other forms of digital sex work such as phone sex chat or instant messaging—although these are not all mutually exclusive.

4.3. Future Research

While the findings of this study suggest that online sex work became more mainstream during the COVID-19 pandemic, it will be interesting to explore how this, like other patterns of home working, evolve in the future. The platform

OnlyFans has been scarcely studied and yet it experienced a large spike in traffic during these times so it would be valuable to investigate whether the platform retained the high number of subscriptions or if performing on adult platforms decreased after pandemic restrictions were lifted. Such research would add to knowledge on the landscape and economics of sex work (e.g.,

Brooks-Gordon et al. 2015).

The sheer volume of media reports shows a degree of integration of the sex industry in mainstream culture and further analysis may also contribute to understanding how sex work could progress towards destigmatisation and increased public awareness. Additionally, given that the reported data have suggested clients’ demands involving services going beyond the sexual act into basic companionship and also into illness fetishes, future research should investigate whether such demands assumed a different meaning for users (both performers and viewers) during these times, or whether the need for such intimacy and interaction was merely a response to the privations of the pandemic lockdown.