Abstract

If an individual who lives abroad feels satisfied, they are able to develop their ability to function in the new culture. The satisfaction with life abroad depends on cultural intelligence (CQ): people with higher CQ easily adapt to a new culture. Our article seeks to understand the relationship between CQ and satisfaction with life abroad using two new variables—culture shock and cultural identity. The direct and indirect relationships between all variables have been investigated using a sample of 194 predominantly international students studying at Czech universities and the PLS SEM statistical technique. The results have shown that CQ is a positive predictor of dependent variable satisfaction with life abroad. When two mediators—cultural identity and culture shock—were added, we found out that the CQ is a positive predictor of the former and a negative predictor of the latter. The analysis of multiple mediations has further confirmed the indirect influence of culture shock (but not cultural identity) on the direct relationship between cultural intelligence and satisfaction with life.

1. Introduction

The ability to function effectively in a culturally unknown environment is expressed (Ang et al. 2007) by cultural intelligence (CQ). The CQ construct consists of four facets: metacognitive, cognitive, motivational, and behavioral (Liao and Thomas 2020). Research (Sousa and Gonçalves 2017; Le et al. 2018) shows that cultural intelligence is a positive predictor of satisfaction with life of people not living in their country of their origin. However, satisfaction with life in a foreign country depends on many aspects, including cultural identity and culture shock (Maddux 2017). The aim of the article is to investigate the relationships between CQ, cultural identity, and culture shock and how all these factors influence life satisfaction during a stay in an unknown culture.

To our best knowledge, there is no study that simultaneously examines the relationships of all factors, respectively how CQ, cultural identity, and culture shock contribute to satisfaction with life. There are studies investigating how CQ contributes to satisfaction (see Section 3) or studies concentrating either on the relationship between CQ and cultural identity (e.g., Peng et al. 2015; Sharma and Hussain 2021) or on the relationship between CQ and culture shock (e.g., Chen et al. 2011; Presbitero 2016), but complex investigation is missing. As Schlaegel et al. (2021) points out, many studies examine the relationship between CQ and job satisfaction. However, if a person lives and works in a different environment, they are affected by many factors that contribute to their satisfaction with life. Their working environment can be friendly and kind but other conditions (e.g., environment when they live with people from a different culture) not. Such conditions can decrease the value of satisfaction with life. Nevertheless, higher CQ is also able to overcome these obstacles.

Our study generally brings a new point of view to life satisfaction abroad because it accentuates two levels affecting satisfaction: the temporal (dynamic) and the permanent (static). In the case of the first level, we have proceeded from the U-curve theory of intercultural communication (Black and Mendenhall 1991). The theory states that an individual is captivated by new and unknown things immediately after their arrival in a new culture and that almost everything seems uncritically interesting and exciting. However, a different situation occurs once this initial infatuation passes, and it is followed by a period of disillusion and frustration (in other words, a period of culture shock) when the individual is seriously confronted with everyday life in the new culture. According to the U-curve theory, the culture shock phase repeats itself periodically until the moment when the individual completely adapts to a new culture. However, until this moment, the fact that the individual is in a phase of enchantment or disillusionment with a new culture plays an important role in the momentarily experienced life satisfaction.

We further anticipate that individuals will feel more uncomfortable abroad if they are strongly connected with their own (original) culture (Peng et al. 2015). This cultural identity represents the permanent level as it is the product of long-term development. A certain degree of homesickness and reduced life satisfaction are regular phenomena in the initial phases of an international stay (English et al. 2017). Nevertheless, it can be justifiably anticipated that a strong cultural identity will have a long-term negative impact on satisfaction with life abroad. On the other hand, a person whose cultural identity is more open to foreigners will probably achieve better satisfaction with life if they live in a different cultural environment.

The article is organized as follows. The next section contains a short literature review defining all topics covered in the article (cultural intelligence, satisfaction with life, cultural identity, and culture shock). The Section 3 describes our hypothesis and is followed by the Materials and Methods section. The Section 5 brings our results, which are further discussed in the Section 6. The Conclusions section summarizes the main points.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Cultural Intelligence

Cultural intelligence (CQ) is often defined as the ability of individuals to function and effectively manage various cultural environments (Ang et al. 2007). It has been researched in association with various training methods and the placement of employees in international branches (Earley and Ang 2003). CQ influences cross-cultural decision-making, the efficiency of multicultural teams, cross-cultural leadership or intercultural communication (Thomas and Inkson 2003), predicts suitable conduct in new cultures (Earley and Mosakowski 2004), and assists in effective intercultural interactions such as adaptation, the development of interpersonal relations and the effective completion of work tasks (Liao and Thomas 2020).

Various authors have conceptualized the construct of CQ using different terminology, but frequently with significant overlap. We follow the terminology of Ang et al. (2007) and divide CQ into four facets: cognitive, metacognitive, motivational, and behavioral. Cognitive CQ expresses the knowledge of legal and economic systems, cultural values and religious faith, marriage politics, art and crafts, or the principles of non-verbal conduct that apply in other cultures. Metacognitive CQ pertains to the control of the processes which a person uses to acquire and understand certain knowledge. Motivational CQ represents the mental ability to focus (and maintain) energy towards the completion of a certain task (or achieving a certain objective). Behavioral CQ involves the individual’s ability to adapt a wide repertoire of verbal and non-verbal displays in interactions with people from various cultures. All these components can mutually influence one another (Gooden et al. 2017).

Studies usually conclude that CQ ensures international companies and organizations or other subjects—including individuals—a competitive advantage in international markets (Ang and Inkpen 2008; Groves and Feyerherm 2011; Yang 2017; Kaleramna et al. 2019; Ratasuk and Charoensukmongkol 2020). The competitive advantage is acquired specifically from managerial CQ, competitive CQ, and structural CQ. The performance and strategy of companies are positively correlated with managers’ CQ (Ang and Inkpen 2008). In addition, the CQ of leaders is also crucial for success in highly competitive global markets (Creque and Gooden 2011; Elenkov and Manev 2009; Groves and Feyerherm 2011; Livermore 2015). From the point of view of entrepreneurial assets, CQ belongs to the intangible resources and capabilities of a firm or an organization. It is difficult to observe and difficult (although not impossible) to quantify. It helps the firm to choose and implement correct strategies (Wawrosz and Jurásek 2021).

CQ is usually understood as (Ng and Earley 2006, p. 10) “a culture-free construct that applies across specific cultural circumstances,” although some authors (e.g., Charoensukmongkol 2021) argue that it comes from the Western tradition. Nevertheless, it seems that the positive impact of CQ on various aspects of life can be found in different countries. Just Charoensukmongkol (2021) for instance discovered that Chinese expatriates’ CQ positively predicts the degree of the Chinese expatriates’ benevolence as perceived by Thai employees. Mangla (2021) investigated how CQ affected the effectiveness of virtual teams during the COVID-19 pandemic (members of the teams were mainly—80%—from India) and concluded that CQ helps in fostering trust and understanding in this environment. Seriwatana and Charoensukmongkol (2020) found, based on data contained from 320 Thai crew members from 7 non-Thai airlines, that CQ was negatively related to team relationship conflict and was positively related to team trust. Other current articles also confirm the importance of CQ. An et al. (2022) mention that cultural competence of nursing students (sample of 235 nursing students) is significantly positively correlated with CQ. Davidaviciene and Al Majzoub (2022) discovered that CQ has a positive effect on the decision-making processes in virtual teams operating in the Middle East. Alifuddin and Widodo (2022) examined the relationship between cultural intelligence and interpersonal communication, psychological capital, and organizational citizenship behavior on a sample of 450 Indonesian junior high school teachers and found that CQ is significantly related to all these factors.

2.2. Satisfaction with Life

The subjective feeling of internal well-being is a multifaceted concept consisting of components that are both affective and cognitive by their nature. These components of life satisfaction include a distinctive construct that expresses a cognitive evaluation of the quality of life in general regardless of the place where the given individual is located. Satisfaction with life generally expresses an attitude and positive emotional state that reflects the affective response, a reaction, or a personal evaluation of a certain experience or event which the individual perceives as being fruitful and successful (Ramsey and Lorenz 2016; Sousa and Gonçalves 2017). The value of satisfaction with life is measured using five entries on a scale (Diener et al. 1985) that has been translated into many languages and has been used in several pieces of cross-cultural research. The scale has demonstrated good psychometric characteristics (Pavot and Diener 2008). High (positive) life satisfaction is associated not only with many personal benefits, such as reduced mortality, improved sleep, and less burnout, but also with organizational benefits, such as lower turnover and better job performance (Jones 2006; Best and Chinta 2021).

General satisfaction with life in a foreign culture depends on where a person comes from, i.e., it depends on any cultural similarities or differences between the home and host cultures. For example, students from Europe and North America were more satisfied during a study stay in Norway than students from Africa and Asia (Sam 2001). Good study results help students to feel satisfied (Rode et al. 2005; Samaha and Hawi 2016), and it is possible to reach a similar conclusion concerning employment. It has also been ascertained (Sam 2001) that factors such as the number of friends, satisfaction with one’s finances, the perception of any discrimination, and information acquired before the international stay influence the satisfaction of the students with their life abroad. It also depends on how the individual feels physically and mentally or on their physical activity: regardless of origin or gender, a lack of sufficient activity leads to a reduced physical–mental state whereby the individual does not feel overly satisfied during this period of life (Zullig et al. 2005).

Paradoxically, a person need not be perfectly linguistically gifted or have friends in a new country to feel satisfied there. People will also not feel any better (or more satisfied with life) if they manage to forgive and excuse various wrongdoings (Sastre et al. 2003). On the other hand, age and personality traits (such as self-confidence, self-control, and religiosity) do influence satisfaction with life (Hong 2017). Understandably, any perceived stress (for example from a foreign environment) can cause an individual to be unsatisfied (Samaha and Hawi 2016). It basically applies that individuals who are generally satisfied with their life not only possess the prerequisites to achieve their goals but are also strongly motivated to do so (Bailey and Snyder 2007; Alrashidi et al. 2022; Burgos-Videla et al. 2022).

2.3. Culture and Cultural Identity

In anthropology, culture is defined as “a comprehensive unit that contains knowledge, belief, art, morality, laws, customs and other ability and habits which an individual adopts as a member of a given society” (Delpechitre and Baker 2017). Culture is a historically transferred system of meanings represented by symbols and a set of inherited concepts expressed in symbolic form which people use to share, maintain, and develop their knowledge of their attitudes to life (Jyoti and Kour 2015). These definitions reflect four fundamental characteristics of culture: (a) it is socially transferred in the process of enculturation, (b) the participants in a certain culture share sufficient knowledge to be able to behave in a manner that is acceptable and comprehensible to one another, (c) regularity and patterns of behavior exist within the framework of a certain culture, and (d) specific groups have shared collective experiences (Delpechitre and Baker 2017).

Cultural identity expresses the degree to which individuals share the values and attributes of the culture they come from. It is a specific type of collective identity which links individuals belonging to the same social group on the psychological level while at the same time differentiating them from the members of other social groups (Peng et al. 2015). Slightly differently: cultural identity can be seen as a form of social identity—a person’s sense of who they are based on their group membership(s) (McLeod 2019). It can be investigated using social identity theory as an important source of pride and self-esteem coming from the fact that a person is a member of a specific culture and as a way how individuals tend to categorize themselves into a social group from their memberships and interactions within that social group (Vaughan and Hogg 2002; Korte 2007; Hu et al. 2021). From an affective point of view, cultural identity helps a person to understand who they are, what their dignity is based on, what they can be proud of, and similar factors (e.g., Arnett 2002; Shokef and Erez 2006; Lin et al. 2016; Lee et al. 2018).

Kmiotek (2017) understands cultural identity as the distance (similarity) between how an individual is in harmony with cultural values and perceives their importance in cultures. The specific characteristics of individual cultures (nations) help in understanding and also comparing in a quantified form the dimensions of culture (Hofstede et al. 2010). It has been ascertained that the cultural dimension plays a key role in how different countries are successful in adapting to innovations and new technologies (Coves Martínez et al. 2018). Various conceptualizations of cultural dimensions exist, but the concept proposed by G. Hofstede (e.g., Hofstede 1984) is the most influential approach to measuring cultural differences (Frías-Jamilena et al. 2018). It has also been adopted and replicated in research into managerial styles of conflict resolution (Caputo 2018). However, Holliday (2010) has criticized the claim that national culture explains and predicts the behavior of the individual, for example, in a foreign culture. His qualitative study on the relationship between a perceived cultural identity and a nation concluded that national culture is purely an external cultural reality that may, however, be (and often is) at odds with personal cultural preferences and perceptions.

2.4. Culture Shock

The term culture shock was first used by Oberg (1960) to describe the anxiety of a person who does not know how to act in a new culture. Culture shock is explained by the theory of cultural learning, the reaction to stress, and social identification (Zhou et al. 2008). It views this as “the initial process of adapting to an unknown environment” (Pedersen 1994, p. 1). According to Marx (2011), international managers experience culture shock at three levels. This involves the so-called culture shock triangle: (1) emotions (ranging from euphoria to depression and satisfaction), (2) social skills and identity (moving from national to transnational social skills and an international identity), and (3) thinking (moving away from stereotyping towards culturally effective thinking).

Culture shock is a completely natural part of the adaptation process. It manifests itself as tension based on the need to adapt, feelings of futility and rejection, frustration at non-acceptance by members of the new culture, confusion of roles, values and self-identity, anxiety, anger or displeasure at everyday things abroad, feelings of helplessness and the inability to cope with a new environment (Oberg 1960), inappropriate social conduct, feelings of isolation, and depression. The culture shock model is depicted (Marx 2011) in phases based on the changes in mood starting with the honeymoon phase (a highly positive mood) which ends with a culture shock (a rapid drop in the mood), through to recovery (once again interrupted by a new cultural shock) and on to the breakdown of culture shock and the commencement of adaptation (the mood improves rapidly).

Five stages of culture shock have been identified and described (Pedersen 1994) in a different inter: (1) the Honeymoon Stage, (2) the Disintegration Stage, (3) the Reintegration Stage, (4) the Autonomy Stage, and (5) the Interdependence Stage. There is also so-called reverse culture shock, which is associated with the process of readapting or adjusting to the home cultural environment after returning home from abroad (Presbitero 2016). Culture shock and the process of adaptation are associated with the change more than with the novelty of a certain situation and environment. Practically everyone arriving from one cultural environment into another is exposed to this phenomenon.

3. Hypotheses

3.1. CQ, Cultural Identity, Culture Shock, and Satisfaction with Life

CQ is associated with the degree to which foreigners are satisfied with their life abroad (or with a long-term stay abroad) (Ward et al. 2009; Hajdu and Hajdu 2016; Sousa and Gonçalves 2017; L. Wang et al. 2017). The abilities measured by CQ contribute to general (i.e., both personal and professional) satisfaction with life in a culturally different society (Jiang and Hu 2016; Le et al. 2018). Given that people with a higher CQ are better able to tune in to subtle differences and/or changes, to adapt quickly, to conduct themselves abroad in a manner that is adequate to the local standards, and to reduce internal tension and conflicts (misunderstandings) just as easily as they develop relationships with the local people (Inkson and Thomas 2011), it can be claimed that CQ contributes to greater life satisfaction among foreigners working and living in an intercultural environment if they succeed in establishing interpersonal relations with the employees in the host country (Cerdin et al. 2018). Research has found that CQ increases effectiveness in the communication and work satisfaction of managers working in multinational companies (Bücker et al. 2014). There is therefore a positive relationship between CQ and satisfaction at work (Diao and Park 2012) and we expect:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Cultural intelligence positively correlates with the satisfaction of an individual living abroad.

Satisfaction is a quantity that varies over time and reflects, amongst other things, mood swings. The process of fitting into a new culture (and therefore overcoming a certain degree of internal discomfort and a feeling of foreignness) can be explained using the U-curve of intercultural adaptation (Black and Mendenhall 1991). In the beginning (during the “honeymoon” period after arriving in the new culture), a person is fascinated by the new culture and finds the new “sights and sounds” exciting. This initial infatuation is followed by a period of disillusion and frustration. The person passes through a period of “disillusion” or “culture shock”, and the individual is seriously confronted with everyday life in the new culture. The third stage (“adaptation”) is characterized by the gradual getting used to the new culture so that the person adopts a suitable manner of behavior according to the cultural norms of the host country. The fourth phase (“the mastery period”) is distinguished by the fact that the individual is admittedly still developing their ability to function effectively in the new culture but does not make any dramatic or substantial advances in this regard and absorbs the differentness of the new culture in small doses.

U-curve theory generally declares that intercultural adaptation (and therefore also life wellbeing and satisfaction in the new culture) is associated with time (Black and Mendenhall 1991; Sambasivan et al. 2017). From this point of view, CQ is not stable, but it depends on what stage according to the U-curve theory an individual is in (K. T. Wang et al. 2015). Culture shock as one of the stages of adaptation for foreigners to a new environment represents a time trigger for negative thoughts aimed against the members of the receiving culture. Culture shock is thus negatively associated with cultural intelligence—e.g., Chen et al. (2011) found in a study based on 382 Philippine laborers working in Taiwan’s manufacturing industries that CQ was positively related to the performance of people under research and negatively related to culture shock. It can be stated from that point of view that an individual with higher CQ is better able to handle any culture shock (Presbitero 2018), and a shock thus does not reduce the individual’s energy to perform their work tasks and personal satisfaction with life. We generally state

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Culture shock mediates the relationship between cultural intelligence and satisfaction with life abroad.

If cultural identity is rooted more deeply and strongly within an individual, contact with another culture may constitute a certain threat (Peng et al. 2015). As consequence people may reject a new culture and emphasize the superiority of the culture they come from (Kosmitzki 1996). In this regard, a strong cultural identity functions as (consumer) ethnocentrism because many theories speculate that ethnocentrism is caused by various types of threats and uncertainties (Bizumic and Duckitt 2012). The defensive attitude of an individual against these threats consists of two basic strategies: the individual clings to their (cultural) roots; knows where they come from, who they are, and what they hold dear; or endeavors to strongly differentiate themselves against other cultures by stating that their culture is significantly superior to others. An individual cannot be fully satisfied with life if they perceive themselves as having to face certain threats and uncertainties.

Both cultural intelligence and cultural identity are seen as exogenous construct (e.g., Lisak and Erez 2015; Lee et al. 2018). Cultural identity can be considered as stable factor (Ang et al. 2007). However, cultural intelligence can overcome tendencies toward psychological rigidity (Peng et al. 2015) and, at least partially, change cultural identity and lead to a better understanding of people coming from a different culture. A person whose cultural identity is more open to foreign cultures due to cultural intelligence will probably have better satisfaction with life when cultural identity contributes to satisfaction. Based on what is mentioned above, we thus expect

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Cultural identity explains (mediates) the relationship between cultural intelligence and satisfaction with life abroad.

3.2. General Theoretical Framework

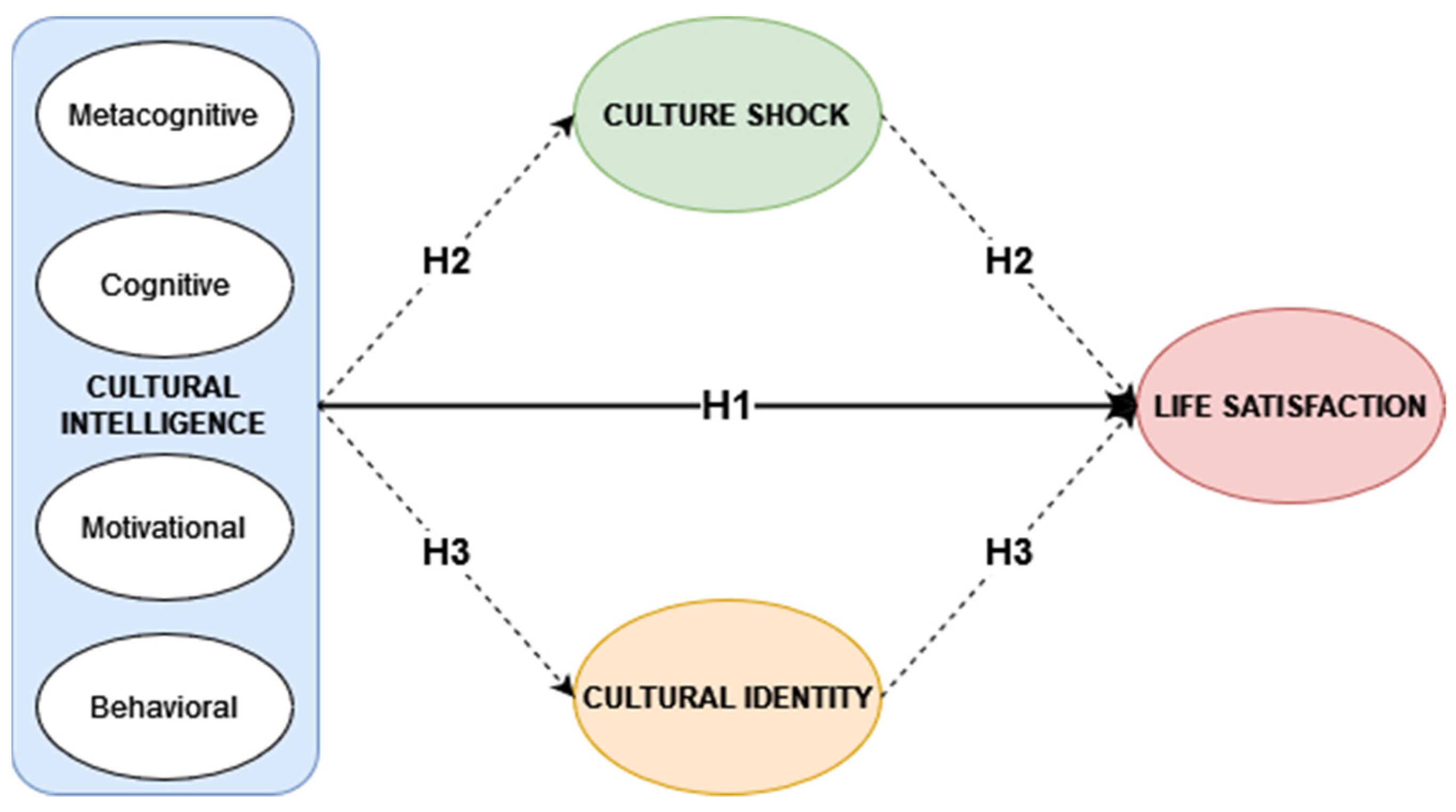

Generally: the exogenous construct (CQ) influences in our model (see Figure 1) the dependence variable—satisfaction with life through two mediating variables (cultural identity and culture shock). This situation requires running multiple mediation analyses. A direct effect is represented between the exogenous variable (CQ) and the endogenous construct (satisfaction with life). There are two specific indirect effects: CQ on satisfaction with life via the mediator of culture shock and the mediator of cultural identity. All mediators were analyzed simultaneously in one model to gain a more complete picture of the mechanisms through which the exogenous construct affects the endogenous construct.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework (Source: own construction).

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Collection, Sample and Measurement

The data on which our hypothesis is tested were obtained through an online questionnaire. The link to the questionnaire was sent out by university mail or distributed via chat on certain platforms (such as MS Teams for example) used for online teaching at some universities. The target group of respondents consisted of students studying in English programs at Czech universities. The research took place at several Czech universities (both private and public): the University of Finance and Administration, Metropolitan University Prague, the University of Economics (Prague), Charles University, the Czech Technical University in Prague, the Czech University of Life Sciences, and others. The survey was completed by 194 respondents: 107 (55.2%) female students and 87 (44.8%) male students. Most of the respondents, 127 (65.8%), were aged 20 to 24; 171 (93.1%) of the students were younger than 30. Out of all the students, 58 (29.9%) declared an education lower than a bachelor’s degree, while 75 declared a bachelor’s education (38.7%), 54 a master’s/MBA education (27.8%), and 7 a Ph.D. (3.6%). The survey was completed by students from the following countries: China, the Czech Republic (approximately 5% of respondents but all students coming from the Czech Republic had an experience with studying or living abroad), Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Germany, Spain, and others. After eliminating any incomplete (or otherwise incorrect) responses, a total of 180 responses were analyzed.

A self-evaluation cultural intelligence scale (CQS), which measures the effectiveness of a person in situations of cultural diversity using a seven-point Likert scale (Ang et al. 2007; Gozzoli and Gazzaroli 2018), was used to measure cultural intelligence. This involves a reflective second-order construct (Thomas et al. 2015) consisting of four factors (components, dimensions)—metacognitive, cognitive, motivational, and behavioral—which constitute first-order reflective constructs (Costers et al. 2019). Examples of the entries contained in the CQ scale include “I adjust my cultural knowledge as I interact with people from a culture that is unfamiliar to me” and “I enjoy living in cultures that are unfamiliar to me”. Cronbach’s alpha values above 0.7 are considered acceptable, but values above 0.8 are preferable (Pallant 2020). Cronbach’s alpha for all four CQ components and the overall CQ was satisfyingly high in this study: 0.848 (for MC CQ), 0.836 (for Cog CQ), 0.884 (for Mot CQ), 0.840 (for Beh CQ) and 0.903 (for total CQ).

There are several scales for measuring satisfaction with life (Emerson et al. 2017; Margolis et al. 2019). Our study used the English version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) (Diener et al. 1985), which consists of five entries related to momentary life situations. The opinions and attitudes of the respondents regarding their life abroad are measured on a seven-point Likert scale. These attitudes are cognitive in nature rather than affective. Several studies (Pavot and Diener 2009; Arnold and Reynolds 2009; Burroughs and Rindfleisch 2002; Sharma and Hussain 2019; Sprott et al. 2009; K. T. Wang et al. 2015) have confirmed the good internal consistency of the measurement. The measurements show a high positive correlation with the measurement of well-being and a strong negative correlation with the measurement of depression, neuroticism, and anxiety, which has also indirectly confirmed the validity of the measurements. An example of the entries on the scale is “The conditions of my life are excellent”. Cronbach’s alpha in our survey achieved a satisfying value (0.884).

Culture shock was measured using an adapted version of the survey created by Mumford (1998). The original survey was tested on young Brits who had had work experience abroad. This survey has two parts: (1) entries directly associated with culture shock (created based on the expert literature and the consensus as to the definition of culture shock) and (2) entries pertaining to personal stress arising from the arrival in a new cultural destination. This survey consists of a total of 12 entries, the respondents answered using a three-point Likert scale. The responses were coded as follows for the purposes of analytical processing: the first response 2 (for example, “Most of the time”), the second response 1 (“Occasionally”), and the third response 0 (“Not at all”). Our paper only used the first part of the original culture shock measurement, i.e., the entries directly associated with culture shock (a total of 7 entries). Examples of these entries are “Have you been missing your family and friends?” or “Do you ever wish to escape from your new environment altogether?” Cronbach’s alpha achieved quite an acceptable value for this measurement (0.757).

Cultural identity was evaluated using 6 entries that were used in the study (Peng et al. 2015) and adopted from a scale used to measure ethnic identity (Roberts et al. 1999). This scale emphasizes the importance of the culture of one’s own (home) country and the delimitation of oneself in this regard. An example of the measurement includes the entry “I often think about my cultural background”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.872.

4.2. Procedure

Firstly, missing data (only 14) were identified. Because less than 5% of the values per indicator were missing, the mean replacement technique was used (Hair et al. 2016). Suspicious response patterns were examined as well. Nine cases (answers) were removed because of almost no variance in the answers (the respondents were not interested in the research and answered monotonously). Although the problem of lack of normality in variable distributions that can distort the results of multivariate analysis is less severe with PLS-SEM, the data were examined carefully to detect it. Since no absolute skewness and kurtosis values of greater than 1 were found, lack of normality was not a problem for our data. No outliers were identified, either, before running PLS-SEM. In order to advance the cumulative science of CQ and to give a critical input to future meta-analyses, Appendix A provides the exhibit with more descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviations, correlations) on all CQ indicators (or CQ variable and its facets) generated by the SmartPLS 4 software.

Secondly, higher-order structures of CQ containing two layers of constructs were investigated in a hierarchical component model, as it is usually called in the context of PLS-SEM. In this way, the number of relationships in the structural model was reduced and the PLS path model became more parsimonious and easier to grasp (Hair et al. 2016). The hierarchical component model of CQ is composed of two layers: the higher-order component (HOC), which captures the more abstract entity (=CQ), and the lower-order components (LOCs), which capture the subdimensions of the higher-order entity (metacognitive, cognitive, motivational, behavioral). In accordance with the previous literature (Charoensukmongkol 2015; Gabel-Shemueli et al. 2019), the hierarchical component model of CQ is reflective–reflective. We used this approach as first-order constructs (metacognitive CQ, cognitive CQ, motivational CQ, behavioral CQ) can be highly correlated and because the structural model relationships may be biased as a result of collinearity issues. To represent the HOC’s measurement model, all the indicators from the LOCs were assigned to the HOC in the form of a repeated indicators approach. Since a common factor model is assumed, it is appropriate to use consistent partial least squares (PLSC). Although there are some objections to the using of PLS-SEM model (e.g., Rönkkö et al. 2016), PLSC returns in this case almost identical results as CB-SEM (used for confirmatory SEM). Both approaches have approximately the same accuracy of estimated parameters and statistical power, with PLSC having most of PLS-SEM’s advantageous features: it requires no distributional assumptions and can handle a complex model (Hair et al. 2016). The higher-order construct (CQ) was validated using PLSC. There was no need to remove any indicator since all of them (including repeated indicators) were higher than 0.5. Moreover, after running the bootstrapping procedure, the results revealed the significance (p < 0.01) of all indicators with the higher- and lower-order components (Hair et al. 2016).

Afterward, the measurement models of all constructs, i.e., culture shock, cultural identity, satisfaction with life) were assessed in terms of internal consistency reliability (composite reliability should be higher than 0.70; in exploratory research, 0.60 to 0.70 is considered acceptable; Cronbach’s alpha is considered the lower bound and composite reliability the upper bound of internal consistency reliability), indicator reliability (the indicator’s outer loadings should be higher than 0.70; the indicator’s outer loadings between 0.40 and 0.70 were removed when the deletion led to an increase in AVE above the suggested threshold value), convergent validity (the AVE should be higher than 0.50), and discriminant validity (the confidence interval of the HTMT statistic should not include the value of 1 for all combinations of constructs) (Hair et al. 2016). The Fornell–Larcker criterion was also used to assess the discriminant validity.

The following rule of thumb for structural model evaluation was assessed: each predictor construct’s VIF value must be higher than 5. The coefficient of determination (R2) was used to measure the model’s predictive power. This coefficient represents the effect of the exogenous latent variables (i.e., cultural intelligence, cultural identity, and culture shock) on the endogenous latent variable (satisfaction with life). In general, R2 values of 0.75, 0.50, or 0.25 for the endogenous construct (satisfaction with life) and mediators (cultural identity, culture shock), respectively, can be described as substantial, moderate, and weak, respectively. The bootstrapping technique was used to assess the significance of the path coefficients. The number of bootstrap samples was set to 5000 valid observations. Critical t-values for a two-tailed test were 1.96 (significance level = 5%), and 2.57 (significance level = 1%). Alternatively, p values lower than 0.05 (significance level = 5%), or 0.01 (significance level = 1%) were examined. The guidelines for assessing f2 are those values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35, which represent small, medium, and large effects (Cohen 2013) of the exogenous latent variable, respectively. Effect size values of less than 0.02 indicate that there is no effect. The predictive relevance of the model was examined using Stone-Geiser’s Q2 value (Hair et al. 2016). The Q2 value was obtained by using the blindfolding procedure for the omission distance (=8). Q2 values larger than 0 suggest that the model has predictive relevance for a certain endogenous construct; values of 0 and below indicate a lack of predictive relevance (Hair et al. 2016). Values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 indicate that an exogenous construct has a small, medium, or large predictive relevance, respectively, for a certain endogenous construct (Hair et al. 2016).

5. Results

All (apart from one item) outer loadings of the reflective constructs (cultural identity, culture shock, satisfaction with life) are well above the threshold value of 0.70, which suggests sufficient levels of indicator reliability. To evaluate the composite reliability of the construct measures, all composite reliability values exceed the threshold (0.70) and all three reflective constructs have high levels of internal consistency reliability. The Cronbach’s alphas for all constructs exceed the threshold value (0.70), i.e., 0.872 for cultural identity, 0.757 for culture shock, 0.884 for satisfaction with life). The AVE values of cultural identity (0.607), culture shock (0.505), and satisfaction with life (0.684) are well above the required minimum level of 0.50. As is shown in Table 1, the Fornell–Larcker criterion is met: the square root of the AVE of each construct is higher than the construct’s highest correlation with any other construct in the model (the square root of the reflective constructs’ AVE on the diagonal and the correlations between the constructs in the of-diagonal position). The values of the other (more reliable) criterion, Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT), are reported in Table 1 (the second value behind the slash). Using 0.85 as the relevant threshold (Hair et al. 2016), all HTMT values are clearly lower than the more conservative threshold value of 0.85.

Table 1.

Fornell–Larcker criterion/HTMT.

There was no need to eliminate constructs (or merge predictors into a single construct) to treat collinearity problems since all VIF values are lower than 5. Collinearity is not an issue. The coefficient of determination is found to be medium for cultural intelligence ( = 0.321). The effect size of CQ on culture shock and cultural identity is medium (0.200, resp. 0.271). The effect size of CQ on life satisfaction is rather small (0.104), the effect size of culture shock on the exogenous variable of life satisfaction is small (0.069), and there is no effect size of cultural identity on life satisfaction. Since all endogenous variables, i.e., cultural identity, culture shock, and satisfaction with life, are larger than 0 (0.123, 0.074, 0.200), they have predictive relevance. The relative impact of predictive relevance was compared by means of the measure of the effect size. The variables of cultural identity and culture shock have small predictive variance ( = 0.058, respectively 0.41), and the construct of cultural identity has no predictive relevance ( = 0.003).

Table 2 presents the results of the bootstrapping procedure. H1 predicted a positive relation between cultural intelligence (CQ) and satisfaction with life (SL). The results support a positive relationship, which is also statistically significant (β = 0.354, p < 0.01). Thus, H1 is supported. H2 predicted that the direct relationship between cultural intelligence and satisfaction with life is mediated by the variable of culture shock. The result supports the assumption (β = 0.103, p < 0.05). Thus, H2 is supported. H3 predicted that the direct relationship between cultural intelligence and satisfaction with life is mediated by the variable of cultural identity. The results do not support the assumption (β = 0.061, p > 0.05). Thus, H3 is not supported. Moreover, the data show that the direct relationship between cultural intelligence and satisfaction with life explains the matter of fact better than the indirect relationship after including the two mediators (culture shock and cultural identity). Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviations, correlations) of CQ indicators is mentioned in Appendix A.

Table 2.

Test of hypotheses.

6. Discussion

Research has already been done into how overall (aggregate) CQ contributes to people’s satisfaction with life abroad. It has been discovered that metacognitive CQ is positively associated with the work satisfaction of employees of non-Japanese origin working in Japan, but paradoxically cognitive CQ has a negative effect in this regard (Huff 2013). For all that, however, CQ generally positively influences the work satisfaction of employees who are foreigners (Bücker et al. 2014). Individuals feel more satisfied at work, if they establish out-of-work social relationships with the locals thanks to their cultural skills (Stoermer et al. 2018). People with a high CQ (in particular a developed cognitive component to their CQ) understand well the details and differences between cultures (Le et al. 2018), draw on this understanding and are more satisfied abroad.

The results of our study have confirmed the importance of all the components of CQ in relation to the life satisfaction of individuals living in culturally unknown environments, and they are fully in line with another study (L. Wang et al. 2017). The reasons for living abroad may differ. However, individuals must feel attracted to new experiences and desire to explore new countries and cultures. Naturally, other factors (such as the state of health, support from family and friends, and so on) will also play a role here, but it can be claimed that these individuals will be more satisfied in a (culturally) foreign environment in general and not just from the point of view of work. Individuals with a high CQ look forward to new environments, do not see a new cultural environment as a threat but as a welcome opportunity for self-development, are able to adapt easily and to establish interpersonal relationships with the locals (Cerdin et al. 2018), can function in the new culture effectively (without any stress or tension), and are generally more satisfied. This conclusion is not surprising if we realize that a high CQ may be based on prior international experiences, such as the number of countries that the individual has visited or lived in (Thomas et al. 2015), the time spent abroad (Tarique and Takeuchi 2008), and the intensity of the effects of intercultural influences (contacts and situations) on the individual (Crowne 2013) or personality traits and skills such as language skills (Shannon and Begley 2008) or the number of languages an individual speaks (Adair et al. 2016), extraversion and openness to new experiences (Presbitero 2018) or the completion of training in intercultural skills such as tertiary management across cultures courses (Ramsey and Lorenz 2016) or student exchange programs abroad (Varela and Gatlin-Watts 2014). All these CQ antecedents (independently, combined or aggregate) create the prerequisites for individuals to be well prepared for living abroad, to view it as a welcome opportunity where they will be able to apply their experience, and skills and to feel satisfied there because the relocation to a foreign environment suits their natural temperament. Further research should investigate how specific facets of CQ or combinations of some facets with adding cultural identity and cultural shock affect satisfaction with life. Studies of Rockstuhl and van Dyne (2018) or Schlaegel et al. (2021) can serve as the guideline for such investigation.

Our study has shown that culture shock is one of the variables that explain the relationship between cultural intelligence and the satisfaction of individuals with life abroad (β = 0.103, p <0.05). Both indirect effects are statistically significant: cultural intelligence negatively correlates with culture shock (β = −0.415, p <0.01), while culture shock negatively influences foreigners’ satisfaction with life abroad (β = −0.248, p <0.01). Given that culture shock is not a permanent quantity and that it fades, its influence on life satisfaction is not overly substantial. Other factors and facts have greater weight when deciding on the life satisfaction (or the lack thereof) of foreigners in a new cultural environment. Cultural intelligence also develops over time, but for all that, when compared with cultural shock, it functions as a type of predisposition that determines how successful individuals will be in new situations of an intercultural nature. Cultural intelligence suppresses and to a certain extent regulates any negative experiences with the foreign environment such as the period of experienced cultural shock and accelerates the adaptation process (Alahdadi and Ghanizadeh 2017) which understandably contributes to greater wellbeing and satisfaction (Yoon et al. 2012). We summarize: our data confirmed H2—that the relationships between CQ and satisfaction with life is mediated by culture shock when CQ reduces shock and lower level of shocks contributes to better satisfaction. It can be stated from the point of view of the abovementioned U-curve theory (Black and Mendenhall 1991) that higher CQ reduce period of disillusion. However, we our research did not specifically concentrate on that period or its length. Further research should investigate the duration the stages of adaptation to a new culture based on CQ.

Our results are fully consistent with the findings of another study (Chen et al. 2011) which confirmed that developed overall cultural intelligence including all its components moderates the negative effects of any culture shock that foreigners eventually experience when in contact with a foreign (unknown) culture. In our case, culture shock partially explains the relationship between cultural intelligence and life satisfaction which is once again in line with the conclusions of the study Chen et al. (2011), in which its authors stated that culture shock indirectly influences the relationship between cultural intelligence and the work efficiency of foreigners living in a new cultural environment. A person who is exposed to the effects of a new culture cannot avoid culture shock (often also repeatedly). However, according to the U-curve theory of intercultural adaptation, these psychosocial states should not last any longer than about 12 months in the majority of cases (Sambasivan et al. 2017). The situation then substantially stabilizes, and the emotional experience of the new cultural environment is not so tempestuous. The culture shock is overcome, and the process of adaptation and adjustment to the new cultural givens commences. The cultural intelligence variable helps in this regard: the higher the CQ, the lower the impact of the culture shock on the adaptation (Presbitero 2016), while the higher the motivational CQ, the weaker any concerns and fears of failure (Marx 2011) and cultural discomfort (Peng et al. 2015). The individual starts to enjoy the new environment and feels satisfied with the local living conditions.

Based on Peng et al. (2015), it was possible to assume that individuals with a strong cultural identity (a close connection with their own culture) would lack the psychological means to immerse themselves in getting to know (learning about) a new culture (or cultures) and that their ability to effectively function in a foreign culture would be affected by this. Since a high CQ raises enthusiasm and interest in getting to know new cultures, being culturally enrooted (or strongly identified) with one’s own culture (or the culture of one’s origin) does not diminish fascination with other cultures in the case of people with high CQ. On the contrary, one must know where they come from to become aware of the values/beauties of other cultures. Our results confirm this fact, and we found a positive relationship between cultural intelligence and cultural identity (β = 0.467, p < 0.01), which comes with several unexpected implications. Firstly, it is necessary to develop one’s intercultural ability on the firm foundation of an acquaintance with your own culture. Individuals that know their roots, know where they come from and the values they espouse and accept the historical (i.e., cultural) legacy of their ancestors positively and are proud of their culture and what it has given the world will probably understand the similar feelings of individuals who come from a different cultural environment.

CQ grows with curiosity (Presbitero 2018), with the enjoyment of discovery, and with thinking about one’s own cultural experiences. Endurance in the discovery of the new cultural dimensions of a country is associated with metacognitive and motivational CQ (L. Wang et al. 2017). The definition, contemplation, and comparison of foreign cultures (which constitute the essence of some components of CQ) often take place against the background of one’s own culture. A cultural identity created over the long term (in essence from childhood as part of the process of a family upbringing and education) represents a certain personality characteristic or trait which can be worked and reckoned with. Cultural identity may be thus another antecedent for cultural intelligence and should be included in the CQ nomological network (Ang and Van Dyne 2015; Jurásek and Wawrosz 2021a). Our data did not confirm H3—that cultural identity mediates the relationship between cultural intelligence and satisfaction with life abroad. As we mention in Section 3.1, cultural intelligence and cultural identity are often seen as exogenous construct. Their relationships should be further researched including longitudinal or cross-lagged panel methods.

The text confirmed the importance of relationships between CQ and satisfaction with life. Satisfaction with life is primarily seen as the dependent variable, and we investigated how it is affected by CQ and how culture shock and culture identity explain or meditate the impact of CQ. However, the opposite approach is also possible. For instance, Jurásek and Wawrosz (2021b) examined how satisfaction with life mediated directly and with the help of intercultural competencies the relationship between the individual components of CQ (i.e., (a) metacognitive, (b) cognitive, (c) motivational, and (d) behavioral) on the one side and intercultural adjustment on the other side, i.e., in their research satisfaction with life was not a dependent but mediated variable. Although their hypotheses were only partially confirmed, i.e., satisfaction with life according to their findings only partially mediated the relationship among investigated variables, the importance of satisfaction with life for overall human performance is clear, and which factors affect satisfaction must be further researched. CQ, especially in multicultural environment, definitively belongs among them. Satisfaction with life in a foreign country can of course be affected by many other factors (for instance, political stability or level of corruption or redistribution in the country—for details, see, e.g., Otáhal et al. 2013; Wawrosz and Valenčík 2014; Wawrosz 2019) that should be incorporated in research about relationships between CQ and satisfaction with life.

7. Conclusions

Our data confirmed that there is a direct positive relationship between cultural intelligence and satisfaction with life and that this relationship is mediated by culture shock. We do not confirm that the relationship is mediated by culture identity. Generally, our data show that the direct relationship between cultural intelligence and satisfaction with life can better explain the dependence of this variable in comparison to indirect relationships, including the mediators of culture shock and culture identity. This study has some limitations that should be acknowledged, particularly related to cross-sectional data and self-reported measures. First, the data come from a cross-sectional design. Thus, we cannot argue for any causal claims. Second, because the survey was conducted on foreign students studying in Czech universities, the findings may not be generalizable to other populations. Nevertheless, the survey includes data from a representative sample of several universities, indicating relevance beyond specific university contexts. Although the sample size is sufficient (Hair et al. 2016) and ensures the robustness of the findings, a larger sample size might have provided slightly different results. Still, future studies may collect data in other settings to test the effects of cultural intelligence on satisfaction with life abroad for specific groups, such as migrant workers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J.; methodology, M.J.; formal analysis, M.J.; investigation, M.J.; resources, M.J.; data curation, M.J.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J. and P.W.; writing—review and editing, P.W.; supervision, P.W.; project administration, P.W.; funding acquisition, M.J. and P.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The result was created in solving student project No. 7427/2020/06 “Intercultural communication: the research on the concept of cultural intelligence (CQ)” using objective-oriented support for specific university research of the University of Finance and Administration.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that the study is based on (the answers from the questionnaire) can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all people who helped them to obtain questionnaire respondents.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Cultural intelligence indicators descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviations, correlations).

Table A1.

Cultural intelligence indicators descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviations, correlations).

| Mean | STDEV | MC1 | MC2 | MC3 | MC4 | COG1 | COG2 | COG3 | COG4 | COG5 | COG6 | MOT1 | MOT2 | MOT3 | MOT4 | MOT5 | BEH1 | BEH2 | BEH3 | BEH4 | BEH5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC1 | 5.593 | 1.333 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||||||

| MC2 | 5.381 | 1.338 | 0.529 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||||

| MC3 | 5.415 | 1.287 | 0.715 | 0.593 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||||

| MC4 | 5.429 | 1.314 | 0.616 | 0.500 | 0.597 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||||

| COG1 | 4.339 | 1.433 | 0.297 | 0.222 | 0.283 | 0.263 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||||

| COG2 | 4.603 | 1.651 | 0.191 | 0.234 | 0.282 | 0.254 | 0.497 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||||

| COG3 | 4.782 | 1.448 | 0.262 | 0.237 | 0.270 | 0.185 | 0.543 | 0.546 | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| COG4 | 4.101 | 1.599 | 0.230 | 0.205 | 0.255 | 0.209 | 0.518 | 0.512 | 0.699 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| COG5 | 4.407 | 1.469 | 0.234 | 0.249 | 0.262 | 0.225 | 0.384 | 0.462 | 0.630 | 0.559 | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| COG6 | 4.367 | 1.443 | 0.196 | 0.347 | 0.241 | 0.282 | 0.489 | 0.516 | 0.540 | 0.589 | 0.507 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| MOT1 | 5.782 | 1.491 | 0.284 | 0.344 | 0.350 | 0.330 | 0.126 | 0.249 | 0.227 | 0.187 | 0.285 | 0.293 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| MOT2 | 5.249 | 1.661 | 0.251 | 0.279 | 0.337 | 0.300 | 0.258 | 0.308 | 0.239 | 0.282 | 0.178 | 0.367 | 0.638 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| MOT3 | 5.249 | 1.622 | 0.319 | 0.322 | 0.384 | 0.330 | 0.230 | 0.274 | 0.344 | 0.307 | 0.220 | 0.335 | 0.585 | 0.784 | 1.000 | |||||||

| MOT4 | 4.915 | 1.608 | 0.216 | 0.310 | 0.344 | 0.293 | 0.182 | 0.207 | 0.197 | 0.166 | 0.216 | 0.283 | 0.551 | 0.604 | 0.602 | 1.000 | ||||||

| MOT5 | 5.392 | 1.323 | 0.348 | 0.334 | 0.462 | 0.378 | 0.128 | 0.304 | 0.299 | 0.271 | 0.255 | 0.351 | 0.561 | 0.570 | 0.655 | 0.568 | 1.000 | |||||

| BEH1 | 4.794 | 1.558 | 0.301 | 0.383 | 0.289 | 0.265 | 0.211 | 0.322 | 0.300 | 0.236 | 0.206 | 0.373 | 0.262 | 0.310 | 0.368 | 0.445 | 0.380 | 1.000 | ||||

| BEH2 | 4.672 | 1.469 | 0.335 | 0.360 | 0.281 | 0.413 | 0.261 | 0.285 | 0.276 | 0.289 | 0.158 | 0.375 | 0.261 | 0.270 | 0.321 | 0.304 | 0.333 | 0.592 | 1.000 | |||

| BEH3 | 5.063 | 1.453 | 0.333 | 0.469 | 0.362 | 0.396 | 0.165 | 0.363 | 0.175 | 0.200 | 0.132 | 0.289 | 0.273 | 0.285 | 0.328 | 0.328 | 0.397 | 0.611 | 0.488 | 1.000 | ||

| BEH4 | 4.831 | 1.430 | 0.272 | 0.388 | 0.325 | 0.326 | 0.157 | 0.274 | 0.218 | 0.204 | 0.111 | 0.273 | 0.355 | 0.263 | 0.333 | 0.343 | 0.452 | 0.478 | 0.528 | 0.558 | 1.000 | |

| BEH5 | 4.603 | 1.518 | 0.247 | 0.400 | 0.303 | 0.329 | 0.181 | 0.159 | 0.072 | 0.187 | 0.004 | 0.220 | 0.211 | 0.243 | 0.311 | 0.342 | 0.291 | 0.377 | 0.485 | 0.491 | 0.557 | 1.000 |

Notes: MC1-MC4 (metacognitive CQ), COG1-COG6 (cognitive CQ), MOT1-MOT5 (motivational CQ), BEH1-BEH5 (behavioral CQ).

References

- Adair, Wendi L., Nancy R. Buchan, Xiao-Ping Chen, and Dong Liu. 2016. A Model of Communication Context and Measure of Context Dependence. Academy of Management Discoveries 2: 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahdadi, Shadi, and Afsaneh Ghanizadeh. 2017. The dynamic interplay among EFL learners’ ambiguity tolerance, adaptability, cultural intelligence, learning approach, and language achievement. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research 5: 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Alifuddin, Moh, and Widodo Widodo. 2022. How Is Cultural Intelligence Related to Human Behavior? Journal of Intelligence 10: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrashidi, Nojoud, Maha Sanat Alreshidi, Wireen Leila Dator, Richard Maestrado, Sandro Villareal, Joyce Buta, Petelyne Pangket, Romeo Mostoles, Jr., Analita Gonzales, Enrique Mina, and et al. 2022. The Mediating Role of Spiritual Intelligence on Well-Being and Life Satisfaction among Nurses in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Path Analysis. Behavioral Sciences 12: 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, Hyeran, Juhyun Jin, and Taehyun Kim. 2022. Factors Affecting Cultural Competence in a Sample of Nursing Students during the Prolonged COVID-19 Pandemic in Republic of Korea: A Cross-Sectional Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 15181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, Soon, and Andrew C. Inkpen. 2008. Cultural Intelligence and Offshore Outsourcing Success: A Framework of Firm-Level Intercultural Capability. Decision Sciences 39: 337–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, Soon, and Linn Van Dyne. 2015. Conceptualization of cultural intelligence: Definition, distinctiveness, and nomological network. In Handbook of Cultural Intelligence: Theory, Measurement, and Applications. London: Routledge, pp. 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, Soon, Linn Van Dyne, Christine Koh, K. Yee Ng, Klaus J. Templer, Cheryl Tay, and N. Anand Chandrasekar. 2007. Cultural Intelligence: Its Measurement and Effects on Cultural Judgment and Decision Making, Cultural Adaptation and Task Performance. Management and Organization Review 3: 335–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen. 2002. The psychology of globalization. American Psychologist 57: 774–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, Mark J., and Kristy E. Reynolds. 2009. Affect and Retail Shopping Behavior: Understanding the Role of Mood Regulation and Regulatory Focus. Journal of Retailing 85: 308–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, Thomas C., and C. R. Snyder. 2007. Satisfaction with Life and Hope: A Look at Age and Marital Status. The Psychological Record 57: 233–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, Shawn, and Ravi Chinta. 2021. Work–life balance and life satisfaction among the self-employed. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 28: 995–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizumic, Boris, and John Duckitt. 2012. What Is and Is Not Ethnocentrism? A Conceptual Analysis and Political Implications. Political Psychology 33: 887–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J. Stewart, and Mark Mendenhall. 1991. The U-Curve Adjustment Hypothesis Revisited: A Review and Theoretical Framework. Journal of International Business Studies 22: 225–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bücker, Joost J. L. E., Olivier Furrer, Erik Poutsma, and Dirk Buyens. 2014. The impact of cultural intelligence on communication effectiveness, job satisfaction and anxiety for Chinese host country managers working for foreign multinationals. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 25: 2068–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Videla, Carmen, Ricardo Jorquera-Gutiérrez, Eloy López-Meneses, and Cesar Bernal. 2022. Life Satisfaction and Academic Engagement in Chileans Undergraduate Students of the University of Atacama. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 16877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burroughs, James E., and Aric Rindfleisch. 2002. Materialism and Well-Being: A Conflicting Values Perspective. Journal of Consumer Research 29: 348–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, Andrea. 2018. Religious motivation, nepotism and conflict management in Jordan. International Journal of Conflict Management 29: 146–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdin, Jean-Luc, Kushal Sharma, and Yuan Liao. 2018. The role of perceived career prospects and international orientation in determining job satisfaction of MNE employees: A moderated mediation model. Thunderbird International Business Review 60: 873–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensukmongkol, Peerayuth. 2015. Cultural intelligence of entrepreneurs and international network ties the case of small and medium manufacturing firms in Thailand. Management Research Review 38: 421–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensukmongkol, Peerayuth. 2021. How Chinese expatriates’ cultural intelligence promotes supervisor-subordinate Guanxi with Thai Employees: The mediating effect of expatriates’ benevolence. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 21: 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Angela Shin-Yih, Lin Yi-Chun, and Airin Sawangpattanakul. 2011. The relationship between cultural intelligence and performance with the mediating effect of culture shock: A case from Philippine laborers in Taiwan. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 35: 246–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Jacob. 2013. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Costers, Annelies, Yves Van Vaerenbergh, and Anja Van Den Broeck. 2019. How to boost frontline employee service recovery performance: The role of cultural intelligence. Service Business 13: 581–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creque, Carole Ann, and Doreen J. Gooden. 2011. Cultural Intelligence And Global Business Competencies: A Framework For Organizational Effectiveness In The Global Marketplace. International Journal of Management & Information Systems (IJMIS) 15: 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowne, Kerri Anne. 2013. Cultural exposure, emotional intelligence, and cultural intelligence: An exploratory study. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 13: 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidaviciene, Vida, and Khaled Al Majzoub. 2022. The Effect of Cultural Intelligence, Conflict, and Transformational Leadership on Decision-Making Processes in Virtual Teams. Social Sciences 11: 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpechitre, Duleep, and David S. Baker. 2017. Cross-Cultural Selling: Examining the Importance of Cultural Intelligence in Sales Education. Journal of Marketing Education 39: 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, Abdoukhadre, and Dong Soo Park. 2012. Culturally intelligent for satisfied workers in a multinational organization: Role of intercultural communication motivation. African Journal of Business Management 6: 7296–309. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, Ed, Robert A. Emmons, Randy J. Larsen, and Sharon Griffin. 1985. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 49: 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, P. Christopher, and Elaine Mosakowski. 2004. Cultural intelligence. Harvard Business Review 82: 139–41. [Google Scholar]

- Earley, P. Christopher, and Soon Ang. 2003. Cultural Intelligence: Individual Interactions across Cultures. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elenkov, Detelin S., and Ivan M. Manev. 2009. Senior expatriate leadership’s effects on innovation and the role of cultural intelligence. Journal of World Business 44: 357–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, Scott D., Martin Guhn, and Anne M. Gadermann. 2017. Measurement invariance of the Satisfaction with Life Scale: Reviewing three decades of research. Quality of Life Research 26: 2251–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- English, Tammy, Jordan Davis, Melissa Wei, and James J. Gross. 2017. Homesickness and adjustment across the first year of college: A longitudinal study. Emotion 17: 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frías-Jamilena, Dolores M., Carmen M. Sabiote-Ortiz, Josefa D. Martín-Santana, and Asunción Beerli-Palacio. 2018. Antecedents and consequences of cultural intelligence in tourism. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 8: 350–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabel-Shemueli, Rachel, Mina Westman, Shoshi Chen, and Danae Bahamonde. 2019. Does cultural intelligence increase work engagement? The role of idiocentrism-allocentrism and organizational culture in MNCs. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management 26: 46–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooden, Doreen J., Carole Ann Creque, and Claudette Chin-Loy. 2017. The Impact Of Metacognitive, Cognitive And Motivational Cultural Intelligence On Behavioral Cultural Intelligence. International Business & Economics Research Journal (IBER) 16: 223–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozzoli, Caterina, and Diletta Gazzaroli. 2018. The Cultural Intelligence Scale (CQS): A Contribution to the Italian Validation. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, Kevin S., and Ann E. Feyerherm. 2011. Leader Cultural Intelligence in Context: Testing the Moderating Effects of Team Cultural Diversity on Leader and Team Performance. Group & Organization Management 36: 535–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jr., G. Tomas M. Hult, Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. 2016. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hajdu, Gábor, and Tamás Hajdu. 2016. The Impact of Culture on Well-Being: Evidence from a Natural Experiment. Journal of Happiness Studies 17: 1089–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, Geert. 1984. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, Geert, Gert Jan Hofstede, and Michael Minkov. 2010. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 3rd ed. Berkshire: McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Holliday, Adrian. 2010. Complexity in cultural identity. Language and Intercultural Communication 10: 165–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Jong-Youl. 2017. A Research for Intelligence as Intercultural Competence. Advanced Science Letters 23: 9899–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Shangui, Lingyu Hu, and Guoyin Wang. 2021. Moderating role of addiction to social media usage in managing cultural intelligence and cultural identity change. Information Technology & People 34: 704–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, Kyle C. 2013. Language, cultural intelligence and expatriate success: MRN. Management Research Review 36: 596–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkson, Kerr, and David Thomas. 2011. Cultural Intelligence: Living and Working Globally. Available online: https://books.google.co.jp/books?hl=en&lr=&id=tC9k0B0-GTIC&oi=fnd&pg=PR2&dq=Cultural+Intelligence:+Living+and+Working+Globally&ots=K4VRQ5lWPU&sig=ayUVuf86J3ixA3u4GKc5PIEuuD0#v=onepage&q=Cultural%20Intelligence%3A%20Living%20and%20Working%20Globally&f=false (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Jiang, Zhou, and Xiaowen Hu. 2016. Knowledge Sharing and Life Satisfaction: The Roles of Colleague Relationships and Gender. Social Indicators Research 126: 379–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Michelle D. 2006. Which is a better predictor of job performance: Job satisfaction or life satisfaction? Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management 8: 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurásek, Miroslav, and Petr Wawrosz. 2021a. Trends in Cultural Intelligence Research in the Context of Intercultural Management. E+m Ekonomie a Management 24: 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurásek, Miroslav, and Petr Wawrosz. 2021b. Cultural inteligence and adjustemnt in the cultural diverse contexts: The role of satisfaction with life and intercultural competence. Economics & Sociology 14: 204–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti, Jeevan, and Sumeet Kour. 2015. Assessing the cultural intelligence and task performance equation: Mediating role of cultural adjustment. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal 22: 236–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleramna, Neha, Teena Saharan, and Upendra Singh. 2019. Cultural Intelligence Stimulating Professional Adjustment. Journal of Economics and Economic Education Research 20: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kmiotek, Łukasz. 2017. Language Proficiency and Cultural Identity as Two Facets of the Acculturation Process. Psychology of Language and Communication 21: 192–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korte, Russell F. 2007. A review of social identity theory with implications for training and development. Journal of European Industrial Training 31: 166–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmitzki, Corinne. 1996. The Reaffirmation of Cultural Identity in Cross-Cultural Encounters. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 22: 238–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Huong, Zhou Jiang, and Ingrid Nielsen. 2018. Cognitive Cultural Intelligence and Life Satisfaction of Migrant Workers: The Roles of Career Engagement and Social Injustice. Social Indicators Research 139: 237–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Yih-Teen, Aline D. Masuda, Xin Fu, and B. Sebastian Reiche. 2018. Navigating between Home, Host, and Global: Consequences of Multicultural Team Members’ Identity Configurations. Academy of Management Discoveries 4: 180–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Yuan, and David C. Thomas. 2020. Cultural Intelligence in the World of Work. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Jing, Jianming Cai, Yan Han, He Zhu, and Zhe Cheng. 2016. Culture Sustainability: Culture Quotient (CQ) and Its Quantitative Empirical Application to Chinese Cities. Sustainability 8: 1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisak, Alon, and Miriam Erez. 2015. Leadership emergence in multicultural teams: The power of global characteristics. Journal of World Business 50: 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livermore, David. 2015. Leading with Cultural Intelligence: The Real Secret to Success. New York: Amacom. [Google Scholar]

- Maddux, James E. 2017. Subjective Well-Being and Life Satisfaction. London: Routledge, pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangla, Namita. 2021. Working in a pandemic and post-pandemic period—Cultural intelligence is the key. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 21: 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, Seth, Eric Schwitzgebel, Daniel J. Ozer, and Sonja Lyubomirsky. 2019. A New Measure of Life Satisfaction: The Riverside Life Satisfaction Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 101: 621–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, Angel Luis Coves, Carmen Maria Sabiote Ortiz, and Juan Miguel Rey-Pino. 2018. The influence of cultural intelligence on intention of internet use. Spanish Journal of Marketing-Esic 22: 231–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, Elisabeth. 2011. Breaking through Culture Shock: What You Need to Succeed in International Business. London: Nicholas Brealey Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, Saul. 2019. Social Identity Theory. Available online: https://www.simplypsychology.org/social-identity-theory.html (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Mumford, David B. 1998. The measurement of culture shock. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 33: 149–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Kok-Yee, and P. Christopher Earley. 2006. Culture + intelligence: Old constructs, new frontiers. Group & Organization Management 31: 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Oberg, Kalervo. 1960. Cultural Shock: Adjustment to New Cultural Environments. Practical Anthropology 7: 177–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otáhal, Tomáš, Milan Palát, and Petr Wawrosz. 2013. What is the Contribution of the Theory of Redistribution Systems to the Theory of Corruption? Národohospodářský obzor (Review of Economic Perspectives) 13: 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, Jullie. 2020. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using IBM SPSS. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pavot, William, and Ed Diener. 2008. The Satisfaction With Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology 3: 137–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavot, William, and Ed Diener. 2009. Review of the Satisfaction With Life Scale. In Assessing Well-Being. Edited by Edward Diener. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 101–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, Paul. 1994. The Five Stages of Culture Shock: Critical Incidents Around the World: Critical Incidents Around the World. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Ann C., Linn Van Dyne, and Kyoungjo Oh. 2015. The Influence of Motivational Cultural Intelligence on Cultural Effectiveness Based on Study Abroad: The Moderating Role of Participant’s Cultural Identity. Journal of Management Education 39: 572–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presbitero, Alfred. 2016. Culture shock and reverse culture shock: The moderating role of cultural intelligence in international students’ adaptation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 53: 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presbitero, Alfred. 2018. Extraversion, Openness to Experience, and Global Career Intention: The Mediating Role of Cultural Intelligence. Journal of Employment Counseling 55: 104–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, Jase R., and Melanie P. Lorenz. 2016. Exploring the Impact of Cross-Cultural Management Education on Cultural Intelligence, Student Satisfaction, and Commitment. Academy of Management Learning & Education 15: 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratasuk, Akaraphun, and Peerayuth Charoensukmongkol. 2020. Does cultural intelligence promote cross-cultural teams’ knowledge sharing and innovation in the restaurant business? Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration 12: 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, Robert E., Jean S. Phinney, Louise C. Masse, Y. Richard Chen, Catherine R. Roberts, and Andrea Romero. 1999. The Structure of Ethnic Identity of Young Adolescents from Diverse Ethnocultural Groups. The Journal of Early Adolescence 19: 301–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockstuhl, Thomas, and Linn van Dyne. 2018. A bi-factor theory of the four-factor model of cultural intelligence: Meta-analysis and theoretical extensions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 148: 124–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode, Joseph C., Marne L. Arthaud-Day, Christine H. Mooney, Janet P. Near, Timothy T. Baldwin, William H. Bommer, and Robert S. Rubin. 2005. Life Satisfaction and Student Performance. Academy of Management Learning & Education 4: 421–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rönkkö, Mikko, Cameron N. McIntosh, John Antonakis, and Jeffrey Edwards. 2016. Partial least squares path modeling: Time for some serious second thoughts. Journal of Operations Management 47–48: 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, David Lackland. 2001. Satisfaction with life among international students: An exploratory study. Social Indicators Research 53: 315–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaha, Maya, and Nazir S. Hawi. 2016. Relationships among smartphone addiction, stress, academic performance, and satisfaction with life. Computers in Human Behavior 57: 321–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambasivan, Murali, Morvarid Sadoughi, and Pouyan Esmaeilzadeh. 2017. Investigating the factors influencing cultural adjustment and expatriate performance. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 66: 1002–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sastre, María Teresa, Geneviève Vinsonneau, Félix Neto, Michelle Girard, and Etienne Mullet. 2003. Forgivingness and Satisfaction with Life. Journal of Happiness Studies 4: 323–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaegel, Christopher, Nicole Franziska Richter, and Vasyl Taras. 2021. Cultural intelligence and work-related outcomes: A meta-analytic examination of joint effects and incremental predictive validity. Journal of World Business 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seriwatana, Phenphimol, and Peerayuth Charoensukmongkol. 2020. Cultural intelligence and relationship quality in the cabin crew team: The perception of members belonging to cultural minority groups. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism 20: 147–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, Lu M., and Thomas M. Begley. 2008. Antecedents of the Four-Factor Model of Cultural Intelligence. In Handbook of Cultural Intelligence: Theory, Measurement, and Applications. London: Routledge, pp. 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Namrata, and Dilwar Hussain. 2019. Role of Cultural Intelligence in Acculturation: Explorations on a Physiognomic Minority Diaspora in India. Journal of Intercultural Communication Research 48: 274–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Namrata, and Dilwar Hussain. 2021. Dynamics of social identity and cultural intelligence in acculturative adaptation of an ethnic minority group in India. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy 21: 453–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokef, Efrat, and Miriam Erez. 2006. Global work culture and global identity, as a platform for a shared understanding in multicultural teams. In National Culture and Groups: Research on Managing Groups and Teams. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, vol. 9, pp. 325–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, Cátia, and Gabriela Gonçalves. 2017. Expatriates and non-expatriates: Effects of cultural intelligence and multicultural personality on passion for work and satisfaction with life. Psychological Thought 10: 90–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprott, David, Sor Czellar, and Eric Spangenberg. 2009. The Importance of a General Measure of Brand Engagement on Market Behavior: Development and Validation of a Scale. Journal of Marketing Research 46: 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]