Merkel Government’s Refugee Policy: Under Bounded Rationality

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Defining Refugees

2.2. Literature Review: Refugee Crises Relate to Internal and External Governance

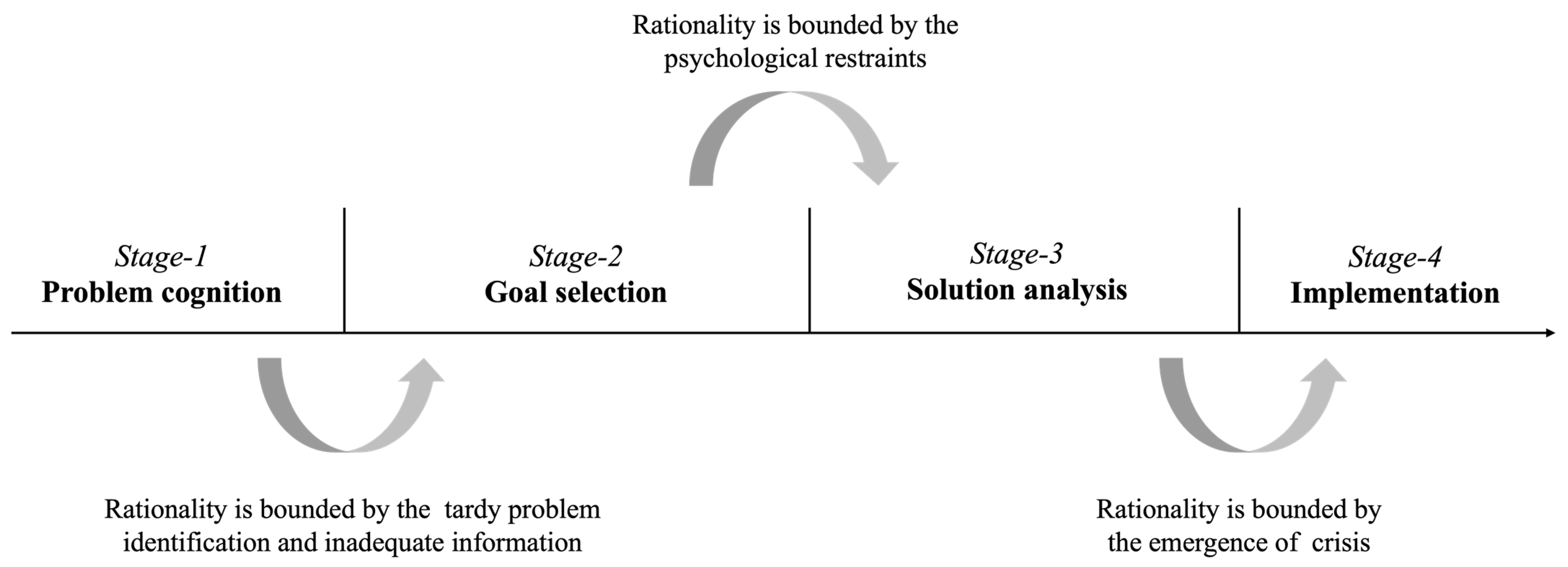

2.3. Policy Making: From Rational Actor to Bounded Rationality

2.4. An Analytical Framework Based on the Theory of Bounded Rationality

3. Results

3.1. The Evolution of Refugee Policies in Germany (2005–2015)

3.1.1. Phase 1: Strict Border Controls (2005–2015)

3.1.2. Phase 2: Welcome Culture (September–October 2015)

3.1.3. Phase 3: Welcome Culture under Restrained Policies (October 2015–2021)

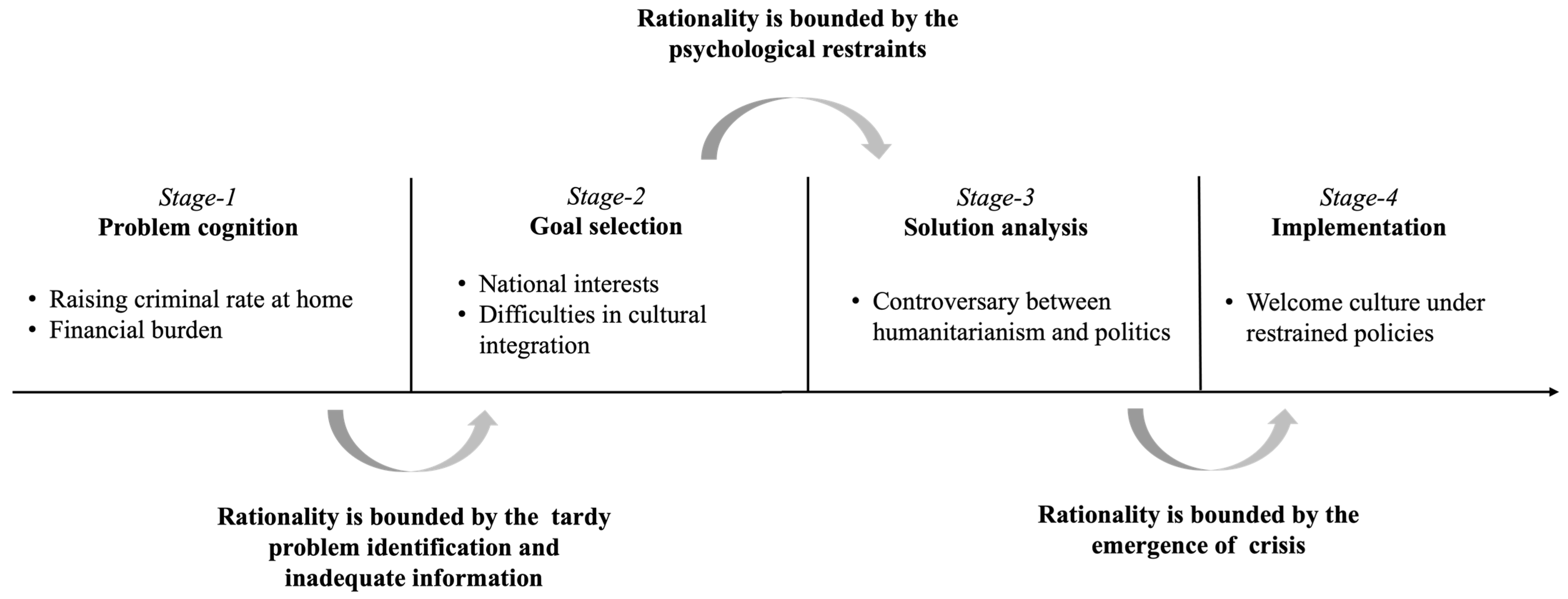

3.2. An Analysis Based on the Analytical Framework

3.2.1. The First Shift in the Refugee Policy of Germany

Key Events and Problem Identification

Goal Selections of Merkel Government

Psychological Restraints on Decision-Making

3.2.2. The Second Shift in the Refugee Policy of Germany

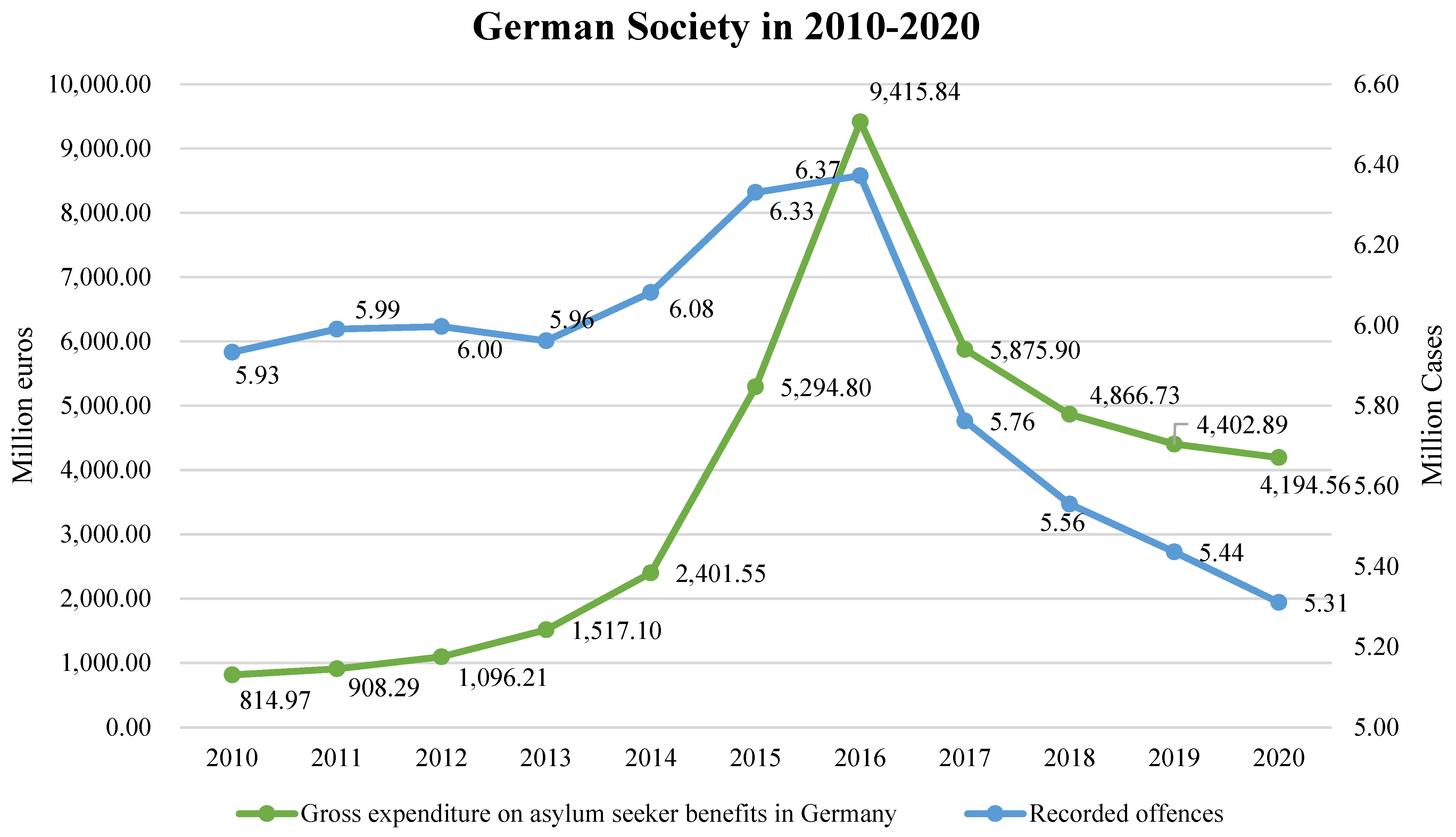

Key Events and Problem Identification

National Interests

Contradictory Humanitarianism and Realpolitik

4. Discussion

5. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Directions for Future Studies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Angela Merkel is the then Chancellor of Germany, who served from 2005 to 2021. She was the first woman chancellor and the second longest-serving chancellor in German history. Under her leadership, Germany has experienced a remarkable development. In response to internal and external challenges, Merkel maintains a political “middle way”, which will be discussed in the third part of the article. |

| 2 | Researchers have different views on the impact of the slogan. Some researchers argue that Merkel’s slogan has exacerbated the refugee problem, while others argue that it has had little impact, that there were already a large number of refugees applying for asylum beforehand, and that the signal it sends gives refugees some hope. The slogan was neither the origin of the refugee crisis nor did it deepen it (Pries 2019; Mushaben 2017; Spijkerboer 2016). |

References

- Ahsan, Ullah A. K. M., and Shahidul Haque. 2020. The Migration Myth in Policy and Practice: Dreams, Development and Despair. Singapore: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Almohammad, Dawoud, Omar Durrah, and Faisal Ahmed. 2021a. Deciphering the motives, barriers and integration of Syrian refugee entrepreneurs into Turkish Society: A SEM approach. Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance 23: 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almohammad, Dawoud, Omar Durrah, Taher Alkhalaf, and Mohamad Rashid. 2021b. Entrepreneurship in crisis: The determinants of Syrian refugees’ entrepreneurial intentions in Turkey. Sustainability 13: 8602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BAMF. 2016a. Das Bundesamt in Zahlen 2015. Available online: https://www.bamf.de/SharedDocs/Anlagen/DE/Statistik/BundesamtinZahlen/bundesamt-in-zahlen-2015.html (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- BAMF. 2016b. Aktuelle Zahlen Zu Asyl Juni 2016. Available online: https://www.bundesregierung.de/resource/blob/974430/426410/9d504e01110b7ff8be1e18da3fc77bff/2016-06-22-bamf-data.pdf?download=1 (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Barber, James David. 2009. The Presidential Character: Predicting Performance in the White House, 4th ed. New York: Pearson Education, Inc., CHINESE SIMPLIFIED language edition published by PEARSON EDUCATION ASIA LTD. and CHINA RENMIN UNIVERSITY PRESS. [Google Scholar]

- Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany. 2022. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_gg/ (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Bonin, Holger. 2005. Wage and employment effects of immigration to Germany: Evidence from a skill group approach. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashman, Greg. 1993. Governmental Decision Making. In What Causes War?: An Introduction to Theories of International Conflict. New York: Lexington Books, pp. 77–123. [Google Scholar]

- Dernbach, Andrea. 2015. Germany suspends Dublin Agreement for Syrian Refugees, EURACTIV. Available online: http://www.Euractiv.com/section/global-europe/news/germany-suspends-dublin-agreement-for-syrian-refugees (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Der Tagesspiegel. 2016. Flüchtlinge in Europa: Zahl der Asylbewerber Deutlich Zurückgegangen, Aktuelle News: Nachrichten aus Berlin und der Welt. Der Tagesspiegel. Available online: http://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/fluechtlinge-in-europa-zahl-der-asylbewerber-deutlich-zurueckgegangen/13744134.html (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Gerhards, Jürgen, Silke Hans, and Jürgen Schupp. 2016. German public opinion on admitting refugees. DIW Economic Bulletin 6: 243–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Geoff, and Gil Loescher. 1994. Beyond Charity: International Cooperation and the Global Refugee Crisis. Human Rights Quarterly 16: 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huntington, Samuel Phillips. 1996. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. New York: Simon & Schuster, Chinese translation copyright by Xinhua Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration. 2021. World Migration Report 2022. Geneva: International Organization for Migration. [Google Scholar]

- IOM. 2016. Migration, Asylum and Refugees in Germany: Understanding the Data, International Organization for Migration. Available online: https://www.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl486/files/country/docs/Germany/Germany-Data-Briefing-1Jan2016.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Jean, Sébastien, and Miguel Jiménez. 2011. The unemployment impact of immigration in OECD countries. European Journal of Political Economy 27: 241–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornelius, Stefan. 2013. Angela Merkel: Die Kanzlerin und ihre Welt, 2015th ed. Hambeurg: Hoffmann und Campe Verlag, Chinese language edition arranged through HERCULES Business & Culture Development GmbH, Germany. Simplified Chinese translation by China CITIC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Koser, Khalid. 2017. International Migration: A Very Short Introduction. Vancouver: Langara College. [Google Scholar]

- Laubenthal, Barbara. 2019. Refugees welcome? reforms of German asylum policies between 2013 and 2017 and Germany’s transformation into an immigration country. German Politics 28: 412–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrus, Michael. 1985. The Unwanted: European Refugees in the Twentieth Century. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mintz, Alex, and Karl DeRouen. 2014. The Rational Actor Model. In Understanding Foreign Policy Decision Making. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Mushaben, Joyce Marie. 2017. Wir Schaffen Das! Angela Merkel and the European refugee crisis. German Politics 26: 516–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OHCHR. 1951. Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. OHCHR. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-relating-status-refugees (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Pernice, Regina, and Judith Brook. 1996. Refugees’ and immigrants’ mental health: Association of demographic and post-immigration factors. The Journal of Social Psychology 136: 511–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Police Crime Statistics. n.d. BKA. Available online: https://www.bka.de/EN/CurrentInformation/Statistics/PoliceCrimeStatistics/policecrimestatistics_node.html (accessed on 26 December 2022).

- Pries, Ludger. 2019. We will manage it’–did chancellor Merkel’s dictum increase or even cause the refugee movement in 2015? International Migration 58: 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees. 1966. OHCHR. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/protocol-relating-status-refugees (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Safeguarding National Interests–Assuming International–Assuming International Responsibility–Shaping Security Together. 2011. German Ministry of Defence. Available online: https://www.bmvg.de/resource/blob/16136/0c1b6d8d0c0e6ba0aed5f0feb0af81d8/g-03-110527-vpr-engl-data.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Sato, Hajime. 1999. The Advocacy Coalition Framework and the Policy Process Analysis: The case of smoking control in Japan. Policy Studies Journal 27: 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, Herbert. 1985. Human nature in politics: The dialogue of psychology with political science. American Political Science Review 79: 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, Quancheng. 2015. Die Flüchtlingskrise in Europa: Zur Analyse ihrer Struktur, Entstehungsgründe und Auswirkungen. Deutschland-Studien 30: 41–53. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen, Theodore. 1963. In Decision-Making in the White House; the Olive Branch or the Arrows: Theodore C. Sorensen. New York: Columbia University Press, pp. 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Spijkerboer, Thomas. 2016. Fact check: Did ‘wir Schaffen Das’ Lead to Uncontrolled Mass Migration? Oxford Law Blogs. Available online: https://blogs.law.ox.ac.uk/research-subject-groups/centre-criminology/centreborder-criminologies/blog/2016/09/fact-check-did-#:~:text=It%20is%20widely%20assumed%20that%20the%20German%20%E2%80%98decision,but%20also%20by%20prominent%20academics%20like%20Ruud%20Koopmans (accessed on 22 November 2022).

- Tang, Meng. 2015. Historische Entwicklung und Status quo der Asylpolitik Deutschlands. Deutschland-Studien 30: 45–57. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Yuanyuan. 2018. The Evolution of the Refugee Policy by Merkel Government and Its Revelation for China. Master’s dissertation, Anhui University of Technology, Ma’anshan, China. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Yuanyuan, and Qingbo Xia. 2018. The Evolution and Challenge of Merkel’s Government Refugee Policy. Journal of Harbin University 39: 34–39. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, A. K. M. Ahsan, Siti Mazidah Mohamad, Noor Hasharina Hassan, Diotima Chattoraj, and Asian Education and Development Studies. 2019. Global skills deficiency: Perspectives of skill mobility in Southeast Asian countries. Asian Education and Development Studies 8: 416–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2021. UNHCR—Germany. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/germany.html (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Vocal Europe. 2020. Germany in the Refugee Crisis–Background, Reactions and Challenges, Vocal Europe. Available online: https://www.vocaleurope.eu/germany-in-the-refugee-crisis-background-reactions-and-challenges/ (accessed on 9 March 2023).

- Welt. 2015. Registrierung: Über eine million flüchtlinge in Deutschland—Welt, DIE WELT. WELT. Available online: https://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article149759624/Mehr-als-eine-Million-Fluechtlinge-in-Deutschland.html (accessed on 20 November 2022).

- Wittkopf, Eugene, Christopher Jones, and Charles Kegley Jr. 2008. The Process of Decision Making: Roles, Rationality, and the Impact of Bureaucratic Organizations. In American Foreign Policy: Pattern and Process, 7th ed. Belmont: Thomson/Wadsworth, pp. 455–88. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Steve. 2018. das deutschlandbild: National image, reputation and interests in post-war Germany. Contemporary European History 27: 651–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Jiepu. 2016. Multi-Dilemma Faced by Merkel’s Refugee Policy. Contemporary World, 34–37. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Na, and Mengqi Wan. 2019. A Study on the EU’s Refugee Policy from the Perspective of Multi-Level Political System Theory—With Two Waves of Refugee Influxes as Examples. Chinese Journal of European Studies, 126–46. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Kang. 2021. The Study on the Refugee Problem in Germany from 2010 to 2019. Master’s thesis, Shandong University, Jinan, China. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zacher, Hannes. 2019. Career Development of Refugees. In International Handbook of Career Guidance. Edited by James A. Athanasou and Harsha N. Perera. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 359–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Liyuan. 2017. The Study of the Attitude of the Merkel Administration to the European Refugee Crisis. Master’s thesis, Hebei Normal University, Shijiazhuang, China. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Chunrong, and Lingling Zhou. 2015. Germany’s Response to the European Refuge Crisis: Its Causes and Influences. Journal of Tongji University Social Science Section 26: 30–39. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Chunrong, and Xiaoshan Ni. 2016. The Integration of Refugees in Germany in the Context of Refugee Crisis: Challenges and Countermeasures. Social Sciences Abroad 6: 75–83. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

| Phase | Strict Border Controls | Welcome Culture | Welcome Culture under Restrained Policies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Period | 2005–2015 | September 2015-October 2015 | October 2015–2021 |

| Key events | The Arab Spring in the Middle East. | Mass drownings at Mediterranean Sea. The death of Aylan. | Terrorist attack in Paris in 2015. The New Year’s Eve incident in Cologne in 2015. |

| Refugee situation | The number of refugee claims exceeded 40,000 in 2010 and increased to 202,800 in 2014. | Number of officially registered refugees reaches 1 million in last three months of 2015. | German Federal Office for Migration and Refugees receives around 400,000 asylum applications in first half of 2016. |

| Governmental attitudes | Strict border controls and restriction. | From hesitation to welcome culture. | Re-tightening the refugee policy. |

| Reason for Seeking Asylum | Disapproval | Ambivalence | Approval | Mean Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subsidiary Protection (EU-Law) | 10 | 8 | 81 | 8.9 |

| Political Persecution because of … (Geneva Convention) | 20 | 16 | 63 | 7.4 |

| Human rights activities | 14 | 12 | 74 | 8.3 |

| Labor union activities | 31 | 20 | 49 | 6.5 |

| Religion (Christian) | 14 | 14 | 72 | 8.2 |

| Religion (Muslims) | 31 | 18 | 51 | 6.7 |

| Ethnic Minority | 21 | 15 | 64 | 7.6 |

| Homosexuality | 27 | 16 | 57 | 7.1 |

| Overall assessment of all reasons for seeking asylum | 19 | 13 | 69 | 7.4 |

| Year | Recorded Cases | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Suspects Total | Non-German Suspects | ||

| Number | Percentage | ||

| 2010 | 2,152,803 | 471,812 | 21.9 |

| 2011 | 2,112,843 | 484,529 | 22.9 |

| 2012 | 2,094,118 | 502,390 | 24.0 |

| 2013 | 2,094,160 | 538,449 | 25.7 |

| 2014 | 2,149,504 | 617,392 | 28.7 |

| 2015 | 2,369,036 | 911,864 | 38.5 |

| 2016 | 2,360,806 | 953,744 | 40.4 |

| 2017 | 2,112,715 | 736,265 | 34.8 |

| 2018 | 2,051,266 | 708,380 | 34.5 |

| 2019 | 2,019,211 | 699,261 | 34.6 |

| 2020 | 1,969,617 | 663,199 | 33.7 |

| Year | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suspected immigrants—total | 136,588 | 151,009 | 165,769 | 167,268 | 174,438 | 114,238 |

| Suspected immigrants by nationalities | ||||||

| Syria | 27,561 | 30,759 | 33,488 | 33,387 | 30,699 | 10,348 |

| Afghanistan | 14,750 | 16,815 | 19,040 | 18,632 | 8266 | 5927 |

| Iraq | 9835 | 11,119 | 11,956 | 12,921 | 5039 | 3625 |

| Iran | 5353 | 6130 | 5940 | 5915 | - | - |

| Nigeria | 5329 | 6237 | - | - | - | - |

| Turkey | 4319 | 4404 | - | - | - | - |

| Somalia | 3961 | 4471 | 4944 | 4844 | 4595 | 3371 |

| Algeria | 3641 | - | 4927 | 6108 | 9882 | 8430 |

| Eritrea | 3521 | 4325 | 4689 | 4989 | - | - |

| Morocco | 3320 | 3837 | 5094 | 6580 | 7684 | 5547 |

| Serbia | - | 3621 | 4197 | 5158 | 12,202 | 8710 |

| Albania | - | - | 4051 | 5692 | 17,466 | 9769 |

| Kosovo | - | - | - | - | 8332 | 6852 |

| Georgia | - | - | - | - | 7251 | 4575 |

| Consequences Are … | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rather Negative | Ambivalent | Rather Positive | |

| Social consequences of refugee migration | |||

| Is good or bad for the economy | 39 | 23 | 39 |

| Cultural life is undermined or enriched by refugees | 44 | 21 | 35 |

| Germany becomes a worse or better place to live because of the refugees | 47 | 30 | 23 |

| The core values of our society are undermined or enriched by refugees | 51 | 30 | 18 |

| The influx of refugees bears more risks or opportunities in the short term | 74 | 11 | 15 |

| The influx of refugees bears more risks or opportunities in the long term | 48 | 15 | 37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niu, Z.; Song, W.; Lu, Y.; Bao, X. Merkel Government’s Refugee Policy: Under Bounded Rationality. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12030187

Niu Z, Song W, Lu Y, Bao X. Merkel Government’s Refugee Policy: Under Bounded Rationality. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(3):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12030187

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiu, Zhongqi, Wenlong Song, Yantong Lu, and Xingyu Bao. 2023. "Merkel Government’s Refugee Policy: Under Bounded Rationality" Social Sciences 12, no. 3: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12030187

APA StyleNiu, Z., Song, W., Lu, Y., & Bao, X. (2023). Merkel Government’s Refugee Policy: Under Bounded Rationality. Social Sciences, 12(3), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12030187