Abstract

Social work and allied professions can struggle to accurately assess child neglect. Our research project is developing a new child neglect measurement tool for use by multi-agencies to address this issue. Phase two of this project employed a Delphi study to gather the views of a range of experts to help develop it. There were two important stages to inform the Delphi study: a systematic review of child neglect measures, and three online focus groups with a purposive sample of 16 participants with expertise in child neglect (academics, practitioners, and experts by experience). We then conducted a three-round modified online Delphi study with a purposive sample of 60 international panellists with expertise in child neglect. We followed the CREDES guidelines for the rigorous application of the Delphi technique. The panel generated salient items for the tool and scaled these for importance. The panel reached consensus for 18 items and 15 elements for the tool. The items included neglect type, chronicity, and severity. The elements included hyperlinks to research and the use of 10-point scales. The draft tool is short and may be useable by a range of practitioners in multi-agency settings. It is inclusive of social harms, such as poverty and social isolation. It will now be piloted.

1. Introduction

1.1. Child Neglect and Its Complex Nature

Child neglect is prevalent across all societies and its impacts and costs for children, families, communities, and societies suggest it merits a more rigorous and complete research evidence base (Daniel et al. 2010; Dubowitz 2007; Mulder et al. 2018). Neglect accounted for 52% of initial child protection plans in England during 2020–2021 (Department for Education 2021). Similarly high levels of neglect coming to the attention of statutory services can be found in countries such as the USA, Canada, and the Netherlands (Euser et al. 2010; Stoltenborgh et al. 2015). In the USA, 75% of initial referrals to child protective services are for neglect, as are the majority of recurrent maltreatment reports (Jonson-Reid et al. 2019; US Department of Health and Human Services 2021).

Child neglect is complex and has varying presentations from mild to severe, and episodic to chronic (English et al. 2005). It can feature a range of interlinked issues from personal through societal levels, including variable levels of care, problematic parent-child relationships, breakdowns in social relationships, neighbourhood deprivation, and a wide range of social harms (Chambers and Potter 2009; Dufour et al. 2008; Lacharité 2014; Shanahan et al. 2017). Of all forms of maltreatment, neglect can lead to some of the most damaging long-term impacts on development, wellbeing, and behaviour (Daniel 2015; Stevenson 2007). It is important to note that the impacts of neglect can be not just harmful but fatal (Sidebotham et al. 2016).

There is a significant range of definitions of child neglect from research, government, and practice (English et al. 2005). Definitions vary among countries and, indeed, among states and jurisdictions within countries (Horwath 2013). There is also a range of conceptual models and typologies of child neglect (Horwath 2007; Sullivan 2000). These issues create a complex picture for assessment.

1.2. Assessment Challenges

The assessment of neglect raises significant challenges for social work and allied professions, such as health and education. These assessments can be filled with ambiguity because neglect is both opaque and complex (Brandon et al. 2009; Doherty 2017; Stewart et al. 2015). Further, the involvement of children’s social work and allied professions is principally based on community and social constructions of neglectful care rather than empirical evidence on what harms children (Dubowitz et al. 2005; Munro 2020). This is largely the case across the world (Dubowitz and Merrick 2010; Horwath 2013).

There has been limited rigorous research into the assessment and measurement of neglect, with no gold standard for its measurement (Bailhache et al. 2013; Haworth et al. 2022; Horwath 2013; Morrongiello and Cox 2020). Rigorously developed and tested evidence-based measurement tools and frameworks are important for accurately measuring child maltreatment (Bailhache et al. 2013; Parker 2020), and can support balanced, systematic, and analytical assessments (Barlow et al. 2010; White and Walsh 2006). In the absence of clear standards and effective tools, practitioners can tend to rely on practice wisdom and subjective judgments (Hines et al. 2006; Stewart et al. 2015; Stokes and Taylor 2014), looking to reduce complex assessments and decisions to manageable decision-making strategies (Broadhurst et al. 2010; Cummins 2018; Platt and Turney 2014). The multi-agency context for identifying and addressing neglect can itself pose complications for an effective assessment of the issue (Thompson 2016). Health, early help, and education agencies are commonly involved in assessing and responding to child neglect (Sharley 2020).

Research has highlighted the varying and varied standards of decision-making within child protection and its impacts (Barlow et al. 2010; Dorsey et al. 2008). Poor, inadequate, or incomplete assessments play a substantive role in significant harm and/or fatality from neglect (Brandon et al. 2020). They can lead to delay, drift, and error in professional decision-making and actions (Helm 2010). In the UK, Ofsted’s (Office for Standards in Education 2014) thematic inspection of responses to neglect deemed assessments to be of heterogenous standards, with 50% of assessments considered inadequate. Within this context of assessment challenges, neglect was an issue in 68% of fatal cases and 83% of non-fatal harm cases in the 368 serious case reviews carried out into children who have died or been seriously harmed through abuse or neglect in the UK between 2014 and 2017 (Brandon et al. 2020). Of the total 1750 maltreatment deaths in the USA, 1277 (73%) were due to neglect (US Department of Health and Human Services 2022).

1.3. The Research Project

The overarching aims of this research project are to develop a valid, simple, and practitioner-accessible multi-agency child neglect measurement tool, titled the ‘family and wider social neglect measurement tool’, to support evidence-based and informed assessments that are also inclusive of key social harms, such as poverty and community deprivation. It consists of three phases:

- Phase one (completed) was a systematic review of national and international, clinical and academic, and single index and multi-dimensional measures of child neglect.

- Phase two, presented here, was an online Delphi study (conducted with a participating local authority in Wales).

- Phase three will pilot the new draft child neglect measurement tool with the participating local authorities, their partner agencies (including health and education), and linked third-sector organisations.

This is a collaborative project, with significant engagement with practitioners and experts by experience (parents with experience of professionals intervening for (suspected) child neglect). This should promote the research’s practice relevance and ensure that social work values are mobilised (Campbell et al. 2017; Uttley and Montgomery 2017).

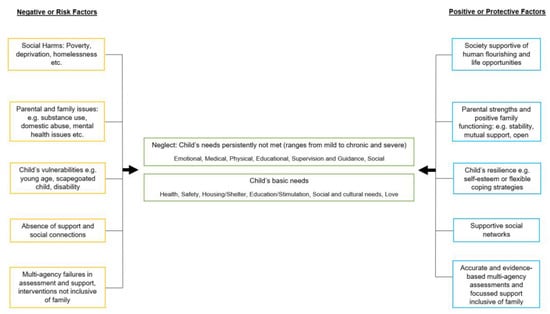

Our child neglect theory of change (see Figure 1 below) provides a framework to guide the project. It was developed from a review of the literature on neglect (including its key dimensions and drivers) and the literature on children’s needs, alongside consultation with our advisory group. It depicts the neglect typology used here and includes key risk and protective factors at personal, family, professional, community, and societal levels. It aims to simply capture the complex social mechanisms involved in neglect.

Figure 1.

Child neglect theory of change.

The social harm approach has informed this project. It recognises that individuals are harmed through the non-fulfilment of their needs and the denial of social resources to exercise life choices within deeply unequal societies (Pemberton 2016). The relationships among poverty, a range of socioeconomic disadvantages, and neglect are well established, if complicated (Bywaters et al. 2016; Carter and Myers 2007; Shanahan et al. 2017). The adoption of a social harm framework can support the understanding and assessment of neglect to move from a reductive vision of harm caused solely by parents to one that recognises and appreciates the range of relational, social, and structural causal and contributing factors present in neglect cases (Lacharité 2014).

This paper reports the Delphi study phase of the project. This was employed to develop items and elements for the draft tool, building on the findings of the preceding systematic review within the overarching evidence-based project. It offered a systematic and efficient approach to gathering the views of a range of experts (Khodyakov et al. 2020).

2. Methods

The Delphi method is suited to explore areas where controversy, complexity, debate, or limited empirical evidence exist (Linstone and Turoff 2002; Smart and Grant 2021), as is the case for child neglect and its measurement (Daniel et al. 2010; Dubowitz et al. 2005; Morrongiello and Cox 2020). Delphi studies use a series of discussions or surveys to explore consensus on disputed topics (Linstone and Turoff 2011). We conducted an online modified Delphi study to gather the views of a range of experts to help develop the new measurement tool. The Delphi was modified through the inclusion of a discussion board (set up via Padlet) to encourage active discussion between rounds (Khodyakov et al. 2020). Such studies offer opportunities for the systematic but also convenient and efficient engagement of relatively large numbers of geographically distributed key stakeholders (Grant et al. 2021) but have the potential pitfall of lower levels of panellist engagement (Khodyakov et al. 2016). We wrote (a priori) and followed a protocol for the Delphi study.

To inform the Delphi study, we first undertook a systematic review of measures of child neglect and then conducted three online focus groups, as described below. As Khodyakov et al. (2016) suggested, ‘The Delphi method complements the results of systematic evidence reviews with consensus-focused engagement of experts and stakeholders in emerging areas where there is a lack of rigorous research or where consensus is needed on how to apply research findings…’ (p. 354).

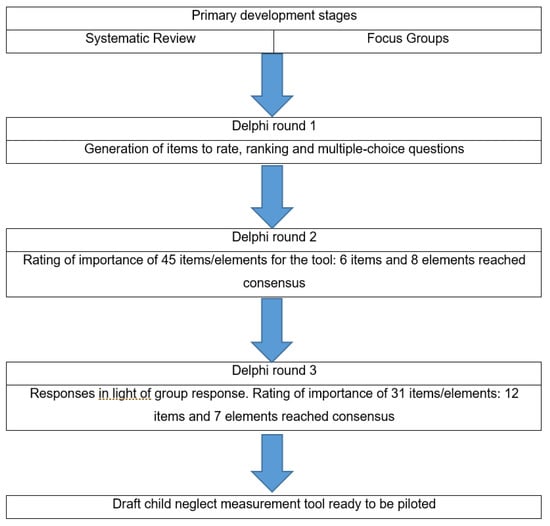

Ethics approval was sought and received through the University of Birmingham (ERN_21-0041). Ethical awareness was maintained at all stages, including the full consideration of the participants’ wellbeing before, during, and after their engagement (Butler 2002). A clear description of the purpose and processes of the research was provided to the participants as part of their engagement. Voluntary consent was provided by all participants. The data from all the stages were anonymised and stored securely. Figure 2 depicts the stages of this study.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of stages in the Delphi study.

2.1. Study Participants

Panellists can be considered the lynchpin of Delphi studies (Green et al. 1999; Fish and Busby 2005). They need to provide a depth and breadth of knowledge on the topic under investigation (Linstone and Turoff 2011; Hamlet et al. 2018). We set clear inclusion criteria for an international panel of experts in child neglect (primarily from the UK and the US), with diverse views on the subject through either personal or professional experience. The purposive sample was recruited from these eligible groups:

- Researchers in the field of child neglect;

- Researchers in the field of measurement in social work;

- Multi-agency practitioners who work with child neglect, including frontline workers, those based in learning and development teams, senior practitioners, and managers;

- Experts by experience—parents with experience with professionals intervening for (suspected) child neglect.

We recruited for the focus groups and Delphi panel through the participating local authority, our existing networks, and contacting the authors of key texts in the fields of measurement tools in social work and neglect. We employed snowball sampling for academics and experts by experience, where those recruited were asked to suggest others with relevant specialist knowledge (Montgomery et al. 2019). All experts by experience were spoken with individually to ensure fully informed consent. All focus group members were invited to take part in the surveys. We emailed each potential participant for the focus groups and Delphi rounds between October 2021 and March 2022.

2.2. Primary Development Stages

2.2.1. Systematic Review

We undertook a systematic review of national and international, clinical and academic, and single index and multi-dimensional measures of child neglect (Haworth et al. 2022). The review found a distinct lack of evidence-based, valid, or reliable child neglect measurement tools. Only four studies, all from North America, met the inclusion criteria and the gold standard of an assessment by a qualified children’s social worker or assessor working within children’s social work. Only one tool, the Child Neglect Index (Trocmé 1996), was considered feasible for practice, with the modifications of the Modified Maltreatment Classification System considered too complicated and cumbersome in both our review and the study of Dubowitz et al. (2005) examining the tool. Analysis revealed that although the included tools had strengths, they excluded some key features of neglect, including neglect chronicity and the range of factors that can contribute to neglect occurring, including social harms. Studies of ‘popular’ tools, such as the Graded Care Profile 2 and HOME, have lacked methodological rigour and have not been assessed against the gold standard of a contemporaneous assessment by a qualified children’s social worker or by an assessor working within children’s social work (Haworth et al. 2022). The review recommended that child neglect measurement tools need to be robustly tested in social work settings to satisfy the criteria of validity, reliability, and practice/clinical utility.

2.2.2. Online Focus Groups

Synchronous online focus groups can be as effective in gaining information from participants as face-to-face groups (Abrams and Gaiser 2017), but with the advantages of reducing logistical issues and the ease of recording and transcription (Cher Ping and Chee 2001). We facilitated three synchronous online focus groups with practitioners, academics, and experts by experience in February/March 2022 to build on the findings of the systematic review, generate first-round items, and better understand a range of views on what was needed in our new measurement tool. The participants were provided with a summary of the findings of the systematic review to read and reflect on prior to engaging with the focus group.

One focus group constituted experts by experience and two professionals and academics. We view practitioners as our primary ‘users’, as they will be using the measurement tool. The approach adopted was attentive to the potential for participants to feel pressure to conform to dominant views and socially acceptable identities and avoided potentially mixing people with opposing interests (Green 2009). We produced separate information and consent forms for experts by experience and practitioners/academics, with attention given to the accessibility of the language.

2.3. Online Modified Delphi Study

We conducted a modified online Delphi, involving three anonymous sequential surveys administered through Qualtrics between April and July 2022. All surveys were piloted with two experts by experience, two practitioners, and two academics prior to being administered to encourage the development of robust, clear, and comprehensible questions (Barrington et al. 2021). Each round remained open for 2 weeks.

We followed the CREDES guidelines (Jünger et al. 2017) for the systematic and rigorous application of the Delphi method. Given that the quality of the results and recommendations ‘…largely depends on the rigour of the application’ (Jünger et al. 2017, p. 703), we applied the Delphi technique systematically and rigorously and demonstrated transparency and clarity in the methodological decisions. Defining participant consensus prior to the commencement of the study was essential (Grant et al. 2018; Jünger et al. 2017). We predetermined that the Delphi would stop after three rounds. Key Delphi study experts describe this predetermined approach as good practice because it reduces many forms of bias (Chaffin and Talley 1980; Linstone and Turoff 2011).

Panellists without prior experience of the Delphi process can experience difficulty understanding the processes involved and engaging meaningfully (Biggane et al. 2019). We proactively maintained contact with panellists and provided clear self-explanatory instructions (including a short video on the essential elements of Delphi studies and how to participate online) for less experienced panellists (Beretta 1996; Khodyakov et al. 2020). To facilitate participation, we ensured each survey did not take longer than 30 min to complete (Donohoe et al. 2012).

The Delphi Rounds

Round one of the Delphi study was an open survey. Panellists were asked to consider and generate salient items for the tool. They were also asked ranking and multiple-choice questions to start to narrow down some of the very broad ideas from the focus groups on what should be in the tool. The panel rated 45 items (distinct parts for the tool that constitute what the tool assesses and focusses on, for example, a scale for neglect severity and the neglect definition used) and elements (features of the tool’s design and look that support its aims, for example, hyperlinks for research and the use of 10-point scales) for the tool in round two on 9-point Likert scales. The following criteria were applied:

- Scores of 1–3 indicated that an item was of limited importance for the tool;

- Scores of 4–6 indicated that an item was important but not essential for the tool;

- Scores of 7–9 indicated that an item was critically important for the tool.

Panellists were also asked to comment on the reasoning for their ratings in free-text boxes located beneath scales. The survey for round three modified that of round two through the inclusion of group statistical responses, asking panellists to re-evaluate their responses in light of this information. The panel rated 31 items/elements in round three. We provided panellists with controlled feedback in the form of summaries of responses (de Meyrick 2003). A range of studies using mixed panels of experts have found that consensus is most likely to be achieved by providing summary feedback to all panellists (as opposed to feedback for each different stakeholder group) and providing the rationale behind the responses (Brookes et al. 2016; Fish et al. 2018; Meijering and Tobi 2016). We applied this approach. The panellists were provided with simple colour-coded feedback (based on the Ram analysis technique)—green indicated it was rated as essential, yellow indicated it was important but not essential, and red indicated it was of limited importance (Grant et al. 2021; Montgomery et al. 2019). They were also provided with the basic average rating for each item by the whole panel. The steps taken led to consensus on the items to include in the neglect measurement tool. The facilitation of an online discussion board between the Delphi rounds encouraged active discussions among the panellists (Khodyakov et al. 2020).

2.4. Analysis

2.4.1. Qualitative Analysis

We analysed the data from the focus groups using manual thematic analysis, as the data set was relatively small (Braun and Clarke 2019). The manual method implemented allowed for a deep understanding of the material and reflection on some of the nuances in both the meaning and language used by the range of participants (Sykora et al. 2020). In order to improve internal validity, we undertook two primary steps. First, two members of the research team independently coded and analysed the same focus group transcript to compare the findings and interpretations (Bird et al. 2013). Second, we checked with two participants from each focus group that the themes generated seemed reasonable to their experience (Elliott et al. 1999).

The qualitative data gathered through the Delphi rounds were in the form of short-form free-text data answers. We analysed these data using qualitative content analysis. This approach emphasises the construction of meaning from the data, so the categories were not pre-decided; rather, they emerged from the data (Goodings et al. 2013; Snee 2013). As the data set was relatively small, manual coding was undertaken, supported by the Qualtrics platform to count the categories that emerged from the data (Chew and Eysenbach 2010). Those most frequently present were then taken forward as the key concepts for the panellists to consider in the next round.

2.4.2. Quantitative Analysis

We analysed the rating and ranking data to determine the existence of consensus among the participants (Grant et al. 2021; Khodyakov et al. 2020). Lynn (1986) suggested that for a tool to achieve content validity, a minimum of 80% of experts should agree on each item. This threshold has been applied in studies by Eubank et al. (2016) and Paek et al. (2018), for example. The following consensus definition was applied in this study:

Consensus will be achieved when 80% or greater of participants rate an item as of critical importance, so 7, 8, or 9 on the 9-point Likert scale.

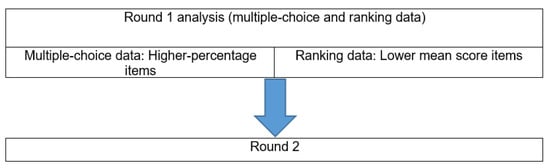

We analysed the multiple-choice data from round one through simple multiple-response analysis on the Qualtrics platform. We analysed both percentages for each option and interquartile ranges to assess consensus (Beiderbeck et al. 2021). The options with higher percentages progressed to round two, with the cut-off point set where the percentage decreased significantly from one option to the next, signifying the option as a significantly less popular choice. We analysed the ranking data from round one by calculating the mean scores, with the cut-off point set where the mean increased significantly. The lower the mean score, the higher the panel ranked that item. Figure 3 depicts this analysis stage.

Figure 3.

Round one analysis of multiple-choice and ranking data.

We applied the consensus definition to data gathered in rounds two and three to determine which items to include in the tool. Items were included in the tool when 80% of the panellists or more rated them as critically important and where at least two out of the three different expert groups accorded this rating. We, therefore, carried out an analysis of variance among the three expert groups. As the data were non-parametric, we applied the Kruskal–Wallis one-way analysis of variance to see whether the median responses for each item differed significantly by expert group (Hohmann et al. 2018).

3. Results

3.1. Focus Groups

We invited 16 experts to participate in the focus groups, and all agreed to participate. As the groups had an analytical function, smaller numbers of participants were desirable (Acocella and Cataldi 2020). Seven of the participants were experts by experience, seven were practitioners (from social work, health, education, and family support fields), and two were academics. The majority were white (14), with one participant of mixed ethnicity, and one Asian. Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the focus group participants.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the focus group participants.

The focus groups ran for up to 60 min to ensure that a range of topics was covered but that participants did not become fatigued. Clarity on the topics to be discussed and proposed timings for each topic supported them to run smoothly (Bloor et al. 2001). The groups provided us with important perspectives on measuring neglect and a more focussed survey for round one (Kvale and Brinkmann 2015; Keeney et al. 2001). They supported the understanding of the language and the concepts the three different expert groups used on child neglect. This was important to ensure that we used language in the study that was understandable and relevant for all (Barrington et al. 2021).

3.2. Delphi Study

We recruited 75 Delphi panellists, with a view to accepting a response rate of 50, as attrition is a feature of Delphi studies. Sixty (80%) agreed to participate. The number recruited was slightly higher than longstanding views on the desired numbers of panellists for Delphis and more recent reports on desired numbers for online Delphis (Khodyakov et al. 2020; Linstone and Turoff 2002). This decision was taken to ensure the inclusion of sufficient numbers from each expert group and to ensure the participating local authority had sufficient multi-agency representation. The majority of the panellists identified as white (83%) and were in professional roles (70%). Academics comprised 17% of the panel; experts by experience, 13%. The completion rates were very high: 90% for the academics, 88% for the professionals, and 87.5% for the experts by experience. Table 2 shows the characteristics of the Delphi panel and their completion rates.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Delphi panel and completion rates.

Table 3 shows the items (distinct parts of the tool that constitute what the tool assesses and focusses on, for example, a scale for neglect severity and the neglect definition used) and elements (features of the tool’s design and look that support its aims, for example, hyperlinks for research and the use of 10-point scales) that reached consensus to be included in the draft tool. Eighteen items reached the consensus threshold in total. Of these, 6 reached consensus in round two, and 12 in round three. Fifteen elements reached the consensus threshold in total. Of these, eight reached consensus in round two, and seven in round three. Five items did not reach consensus, and six elements did not reach consensus. The Kruskal–Wallis tests revealed that for all but one of the items and elements selected for the tool, the medians were considered equal across the expert groups. The data for each item and element selected for the tool are included in Table 3, while the data for each item and element not selected for the tool are included in Table 4.

Table 3.

Items and elements selected for the tool.

Table 4.

Items and elements not selected for the tool.

There were two items where reaching consensus was more complicated. The panel agreed that the tool should use a family-friendly definition of neglect (a definition that does not pathologise families), but the two options offered in round two did not reach consensus. We, therefore, held a focus group with this study’s advisory group, leading to both options being amended for round three. In round three, neither option reached consensus; 71.4% of the panel rated option one as of critical importance, and 54.9% rated option two as of critical importance. We decided to include option one in the tool, as this option scored significantly higher. This defines neglect as ‘when a child/young person’s needs are not met, to a level that results in avoidable harm to their health, development or wellbeing. Neglect may be caused by family difficulties or through families not having enough resources or support to meet their children’s needs’.

Two options for capturing children’s and young people’s views reached the 80% threshold for inclusion. Option one (an open text box with prompts) was included, as it had a higher rating (83%) than option two (an open text box with prompts and options for drawing by the child/young person) (82.3%). However, given how close these ratings were, an option was included in the tool to attach a drawing.

The panel agreed that questions in the tool using a scale as the answer type should be positively scaled, with scales running from 0 to 10. Furthermore, these should be augmented by qualitative data. So, for example, the tool asks for a numerical rating running from low to high in severity, and then asks for examples of the severity of the neglect. The panel agreed on the importance of including a range of hyperlinks to guidance and research. The aim was to include one short piece of research/guidance for ease in practice and one longer open-access academic journal article to encourage research literacy. However, given the limited research base for child neglect, this was not possible for all options. The hyperlinks will be reviewed annually to ensure the knowledge being accessed is up to date.

The free-text responses of the panellists in the Delphi rounds revealed a number of themes important for the tool and its development. One way the group suggested the tool could support informed practitioner decision-making was by adding free-text boxes linked to scales, with these boxes used to provide evidence to support the rating given. They also suggested that including a section on parents’ aspirations for their children could support motivation for change, and further, that the review section of the tool should be set at 3–6 months and used to review the actions taken and the support services offered and their impacts for better or worse.

The draft family and wider social neglect measurement tool was developed from the items and elements that reached consensus in the Delphi study. An outline of its contents can be found in Table 5 on page 19.

Table 5.

Contents of the ‘family and wider social neglect measurement tool’.

4. Discussion

This study represents the first effort in the field of social work to identify and reach expert consensus through a Delphi study on the development of a new child neglect measurement tool. The draft ‘family and wider social neglect measurement tool’ was developed through a rigorous and systematic but also collaborative research project. The overarching evidence-based methodology has been inclusive of the knowledge developed through practice and lived experience, in line with more recent trends in evidence-based research (Oliver et al. 2019; Wieringa and Greenhalgh 2015). This has been important for a research project focussed on impacting real-world practice and producing knowledge in ethical and fair ways (Barber et al. 2011). The Delphi study reported in this paper has acted as an important stage in this process, building on the findings of the systematic review to develop items and elements for the draft tool. It offered a systematic approach to gathering the views of a range of experts, free from group pressures and associated socio-cognitive biases (Grant et al. 2018; Khodyakov et al. 2020). Delphi studies can act as important components of evidence-based approaches in under-researched areas, such as child neglect (Lee et al. 2011).

There are a number of features of the Delphi study that have promoted the draft tool’s internal, content, and construct validities and sensitivity and specificity. The application of the CREDES guidelines supported a comprehensive and rigorous Delphi study. The Delphi panel constituted a relatively large number of experts in child neglect. There were very high response rates and high rates of agreement among the panel members and the three different expert groups as to what items and elements should be included in the tool. We set an 80% consensus threshold for the inclusion of items and elements.

Proctor and Dubowitz (2014) stated ‘At a minimum, an assessment should determine whether or not neglect has occurred, the nature and severity of the neglect, whether the child will be safe, what factors are contributing to the neglect, what protective factors are present, and what interventions have been tried, with what results’ (p. 44). Our draft tool covers these fundamental areas required to be comprehensive for assessing child neglect, and may offer face, content, and construct validity. Its reliability, validity, sensitivity, and specificity will need to be tested in the forthcoming pilot phase of the project.

The included items and elements should support the tool’s aims of:

- Accurately assessing child neglect;

- Supporting balanced and evidence-informed assessments inclusive of strengths as well as concerns;

- Supporting assessments inclusive of factors that make family life and family wellbeing harder, such as social isolation and poor housing.

The draft tool has nine short-labelled sections and clear, concise guidance for assessors. It contains hyperlinks to research and guidance on key areas, such as neglect severity, the adopted neglect typology, and causes of and complicating factors for neglect. Table 5 on page 19 shows the main contents of the tool.

There are a number of features that distinguish the family and wider social neglect measurement tool from other child neglect assessment tools we examined in the systematic review and commonly used tools such as the Graded Care Profile (1 and 2). Although these tools have strengths and important features to learn from, they all present missing elements. Firstly, our tool is free for all, not behind a paywall. It focusses on the presence or absence of actual child neglect, and its severity, chronicity, and type. This differs from tools such as the Graded Care Profile (1 and 2) or the HOME tool, which essentially assess the quality of care provided. There is a range of differences between our tool and those considered to have been rigorously tested in the systematic review. It adopts the comprehensive neglect typology used for this study, assesses neglect chronicity, has a specific support section to indicate the type of support the family requires, and incorporates a review section to measure change. It can complement more general children and families in multi-agency assessments.

The adoption of a social harm framework in the project and Delphi study offers a new approach to understanding child neglect within the contexts of wider society, government policies, and organisational practices. It provides a robust lens for analysing the complex drivers for neglect and family (dys)function from family to societal levels. There have, therefore, been fundamentally different conceptual and value bases guiding the tool’s development. In the Delphi study, the panellists were asked to consider the relevance of social harms to the tool and how these could be included in the tool. Other tools, such as the GCP (1 and 2) and Trocmé’s (1996) Child Neglect Index, for example, primarily focus on the family level, whereas the family and wider social neglect measurement tool, supported by the social harm framework, looks to key risk and protective factors for neglect from the family to societal levels, while having an ethos of being family-focussed and not just child-focussed.

However, this study has limitations. The results offer the collective views of a particular group of experts on measuring child neglect (Hasson and Keeney 2011). The Delphi panellists were mainly from the UK, and a majority were White British practitioners. Experiential and practitioner knowledge has been criticised for simply reflecting their own experiences and outlooks, while lacking a wider understanding of the systems and societies in which they work or participate (Castro et al. 2018; Solbjør and Steinsbekk 2011). This was evident in some of the free-text answers and suggestions for the key drivers of neglect. While Delphi studies are viewed as democratic processes, those in the minority groups (experts by experience and academics) may have been influenced to change their views based on the views of those in the majority group (practitioners) (Powell 2003). There remains limited guidance on the desired balance between qualitative and quantitative data in Delphi studies. The approach used in this study may have differed from another group of researchers approaching the same study, leading to potentially different results and, therefore, a different tool (Keeney et al. 2001). The draft tool remains to be tested, but this is currently underway in a pilot study as the final stage of this project.

4.1. Implications for Practice

The family and wider social neglect tool aims to support evidence-based and research-informed child neglect assessments and decision-making in practice. This is important given that child welfare academics have, over many years, advocated for more research and evidence-based approaches to assessing child neglect (Brandon et al. 2013; Dubowitz et al. 1993; Dubowitz 2007; Macdonald 2001; Stevenson 1998; Tanner and Turney 2003; Taylor and Daniel 2015). The social harm framework adopted and enacted in the Delphi study reminds practitioners that neglect cases are often characterised by difficulties ranging from the familial to the societal level and families facing a range of social harms, notably, socioeconomic disadvantage (Bywaters et al. 2022; Lacharité 2014). The tool’s focus on strengths and concerns, alongside this range of drivers for neglect, should encourage family-centred practice and a focus on needs and unmet needs, as opposed to a singular focus on risk. The inclusion of parental hopes and aspirations for their children reflects the literature that suggests their importance for motivation to change (Boddy et al. 2016; Koprowska 2014). The tool’s focus on community-based support may act as one step towards reconnecting professional systems with communities and the support they can offer.

Research on the impacts of COVID-19 on practice has revealed new time pressures on social workers and allied professionals and less opportunity for them to visit families to assess family life and environments (Baginsky and Manthorpe 2020; Cook and Zschomler 2020; Ferguson et al. 2022). Our succinct tool should support practitioners to produce concise neglect-focussed assessments within this new practice landscape.

4.2. Implications for Research

This study has demonstrated the potential benefits of employing the Delphi technique for the development of tools and measures in social work research. The study design, with distinct developmental stages followed by Delphi rounds, can function as one example for the development of rigorous Delphi approaches in social work research. The approach adopted has shown how Delphi studies and evidence-based approaches can be inclusive, collaborative, and ethical while generating robust and valid knowledge.

The inclusion of parents with experience with children and family social work (an often-marginalised group in research and practice) in a Delphi study and project focussed on a statutory multi-agency arena demonstrates some possibilities for evidence-based research that aims to be inclusive of the knowledge gained through lived experience. The approach adopted chimes with codes of ethics for social work research, such as those presented by Butler (2002) and JUCSWEC (2008). The focus on neglect as a social form of harm with a range of drivers is important for research that aims to study neglect within its wider social and societal contexts.

4.3. Next Steps in the Study

The next phase of this project is to pilot the draft child neglect measurement tool with multi-agency practitioners in the participating local authority. This phase will test the tool’s validity, reliability, sensitivity, specificity, and useability in practice. It will employ a test-retest method and gain the views of practitioners and families on the tool.

5. Conclusions

This Delphi study employed a mixed panel of experts to develop a new multi-agency child neglect measurement tool. The tool is succinct, may be useable by a range of practitioners in multi-agency settings, and is inclusive of how social harms can contribute to neglect. It aims to support informed assessments and decision-making in cases of child neglect.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H., P.M. and J.S.; methodology, S.H., P.M. and J.S.; formal analysis, S.H.; investigation, S.H.; data curation, S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.H.; writing—review and editing, S.H., P.M. and J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Neath Port Talbot. Agreement number: 1941869.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Application for Ethical Review ERN_21-0041: Thank you for your application for ethical review for the above project, which was reviewed by the Humanities and Social Sciences Ethical Review Committee of the University of Birmingham. On behalf of the Committee, I confirm that this study now has full ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Simon Haworth. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participating local authority Neath Port Talbot. We would also like to thank the experts by experience, practitioners, and academics who kindly contributed to the focus groups and constituted the Delphi panel.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abrams, Katie M., and Ted J. Gaiser. 2017. Online Focus Groups. In The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods. London: Sage, pp. 435–50. [Google Scholar]

- Acocella, Ivana, and Silvia Cataldi. 2020. Using Focus Groups: Theory, Methodology, Practice. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Baginsky, Mary, and Jill Manthorpe. 2020. Managing through COVID-19: The Experiences of Children’s Social Care in 15 English Local Authorities. London: NIHR. [Google Scholar]

- Bailhache, Marion, Valériane Leroy, Pascal Pillet, and Louis-Rachid Salmi. 2013. Is early detection of abused children possible? A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of the identification of abused children. BMC Pediatrics 13: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, Rosemary, Peter Beresford, Jonathan Boote, Cindy Cooper, and Alison Faulkner. 2011. Evaluating the impact of service user involvement on research: A prospective case study. International Journal of Consumer Studies 35: 609–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, Jane, Joanne D. Fisher, and David Jones. 2010. Systematic Review of Models of Analysing Significant Harm. London: Department for Education. [Google Scholar]

- Barrington, Heather, Bridget Young, and Paula R. Williamson. 2021. Patient participation in Delphi surveys to develop core outcome sets: Systematic review. BMJ Open 11: e051066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beiderbeck, Daniel, Nicolas Frevel, Heiko A. von der Gracht, Sascha L. Schmidt, and Vera M. Schweitzer. 2021. Preparing, conducting, and analyzing Delphi surveys: Cross-disciplinary practices, new directions, and advancements. Methods X 8: 101401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beretta, Ruth. 1996. A critical review of the Delphi technique. Nurse Researcher 34: 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggane, Alice M., Paula R. Williamson, Philippe Ravaud, and Bridget Young. 2019. Participating in core outcome set development via Delphi surveys: Qualitative interviews provide pointers to inform guidance. BMJ Open 9: e032338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, Philippa, Victoria Campbell-Hall, and Ritsuko Kakuma. 2013. Cross-national qualitative research: The development and application of an analytic framework in the Mental Health and Poverty Project. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 16: 337–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloor, Michael, Jane Frankland, Michelle Thomas, and Kate Stewart. 2001. Focus Groups in Social Research. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Boddy, Jennifer, Patrick O’Leary, Ming-Sum Tsui, Chui-man Pak, and Duu-chiang Wang. 2016. Inspiring hope through social work practice. International Social Work 61: 587–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, Marian, Sue Bailey, Pippa Belderson, and Birgit Larsson. 2013. Neglect and Serious Case Reviews. London: NSPCC. [Google Scholar]

- Brandon, Marian, Sue Bailey, Pippa Belderson, and Jane Dodsworth. 2020. Complexity and Challenge: A Triennial Analysis of SCRs 2014–2017. London: Department for Education. [Google Scholar]

- Brandon, Marian, Sue Bailey, Pippa Belderson, Catherine Warren, Ruth Gardner, and Jane Dodsworth. 2009. Understanding Serious Case Reviews and their Impact: A Biennial Analysis of Serious Case Reviews 2005–2007. London: Department for Children, Schools and Families. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11: 589–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadhurst, Karen, David Wastell, Sue White, Christopher Hall, Sue Peckover, Kellie Thompson, Andrew Pithouse, and Dolores Davey. 2010. Performing “initial assessment”: Identifying the latent conditions for error at the front-door of local authority children’s services. British Journal of Social Work 40: 352–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookes, Sara T., Rhiannon C. Macefield, Paula R. Williamson, Angus G. McNair, Shelley Potter, Natalie S. Blencowe, Sean Strong, and Jane M. Blazeby. 2016. Three nested randomized controlled trials of peer-only or multiple stakeholder group feedback within Delphi surveys during core outcome and information set development. Trials 17: 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Ian. 2002. A code of ethics for social work and social care research. British Journal of Social Work 32: 239–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bywaters, Paul, Guy Skinner, Aimee Cooper, Eilis Kennedy, and Afra Malik. 2022. The Relationship between Poverty and Child Abuse and Neglect: New Evidence. London: Nuffield Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Bywaters, Paul, Lisa Bunting, Gavin Davidson, Jennifer Hanratty, Will Mason, Claire McCartan, and Nicole Steils. 2016. The Relationship between Poverty, Child Abuse and Neglect: An Evidence Review. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Anne, Brian J. Taylor, and Anne McGlade. 2017. Research Design in Social Work: Qualitative and Quantitative Methods. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, Vernon, and Miranda R. Myers. 2007. Exploring the risks of substantiated physical neglect related to poverty and parental characteristics: A national sample. Children and Youth Services Review 29: 110–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, Eva Marie, Tine Van Regenmortel, Walter Sermeus, and Kris Vanhaecht. 2018. Patients’ experiential knowledge and expertise in health care: A hybrid concept analysis. Social Theory and Health 17: 307–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffin, Wilkie W., and Wayne K. Talley. 1980. Individual stability in Delphi studies. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 16: 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, Ruth M., and Cathryn C. Potter. 2009. Family needs in child neglect cases: A cluster analysis. Families in Society 90: 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, Cynthia, and Gunther Eysenbach. 2010. Pandemics in the Age of Twitter: Content Analysis of Tweets during the 2009 H1N1 Outbreak. PLoS ONE 5: e14118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, Laura L., and Danny Zschomler. 2020. Virtual home visits during the COVID-19 pandemic: Social workers’ perspectives. Practice Social Work in Action 32: 401–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, Ian. 2018. Poverty, Inequality and Social Work: The Impact of Neo-Liberalism and Austerity Politics on Welfare Provision. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, Brigid. 2015. Why Have We Made Neglect So Complicated? Taking a Fresh Look at Noticing and Helping the Neglected Child. Child Abuse Review 24: 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, Brigid, Julie Taylor, and Jane Scott. 2010. Recognition of neglect and early response: Overview of a systematic review of the literature. Child & Family Social Work 15: 248–57. [Google Scholar]

- de Meyrick, Julian. 2003. The Delphi method and health research. Health Education 103: 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Education. 2021. Characteristics of Children in Need, Reporting Year 2021; London: Department for Education. Available online: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/characteristics-of-children-in-need/2021 (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Doherty, Paula. 2017. Child protection threshold talk and ambivalent case formulations in ‘borderline’ care proceedings cases. Qualitative Social Work 16: 698–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohoe, Holly, Michael Stellefson, and Bethany Tennant. 2012. Advantages and limitations of the e-Delphi technique: Implications for health education researchers. American Journal of Health Education 43: 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsey, Shannon, Sarah A. Mustillo, Elizabeth M. Z. Farmer, and Eric Elbogen. 2008. Caseworker assessments of risk for recurrent maltreatment: Association with case-specific risk factors and re-reports. Child Abuse & Neglect 32: 377–91. [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz, Howard. 2007. Understanding and addressing the “neglect of neglect”: Digging into the molehill. Child Abuse & Neglect 31: 603–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz, Howard, and Joav Merrick. 2010. International Aspects of Child Abuse and Neglect. New York: Nova Science. [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz, Howard, Maureen Black, Raymond H. Starr, Jr., and Susan Zuravin. 1993. A conceptual definition of child neglect. Criminal Justice and Behavior 20: 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubowitz, Howard, Steven C. Pitts, Alan J. Litrownik, Christine E. Cox, Desmond Runyan, and Maureen M. Black. 2005. Defining child neglect based on child protective services data. Child Abuse & Neglect 29: 493–511. [Google Scholar]

- Dufour, Sarah, Chantal Lavergne, Marie-Claude Larrivée, and Nico Trocmé. 2008. Who are these parents involved in child neglect? A differential analysis by parent gender and family structure. Children and Youth Services Review 30: 141–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, Robert, Constance T. Fischer, and David L. Rennie. 1999. Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 38: 215–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, Diana J., Richard Thompson, J. Christopher Graham, and Ernestine C. Briggs. 2005. Toward a definition of neglect in young children. Child Maltreatment 10: 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eubank, Breda H., Nicholas G. Mohtadi, Mark R. Lafave, J. Preston Wiley, Aaron J. Bois, Richard S. Boorman, and David M. Sheps. 2016. Using the modified Delphi method to establish clinical consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with rotator cuff pathology. BMC Medical Research Methodology 16: 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euser, Eveline M., Marinus H. van IJzendoorn, Peter Prinzie, and Marian J. Bakermans-Kranenburg. 2010. Prevalence of child maltreatment in the Netherlands. Child Maltreatment 15: 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, Harry, Laura Kelly, and Sarah Pink. 2022. Social work and child protection for a post-pandemic world: The re-making of practice during COVID-19 and its renewal beyond it. Journal of Social Work Practice 36: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, L. Stone, and Dean M. Busby. 2005. The Delphi method. In Research Methods in Family Therapy, 2nd ed. Edited by Douglas Sprenkle and Fred Piercy. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 238–53. [Google Scholar]

- Fish, Rebecca, Caroline Sanders, Richard Adams, Julie Brewer, Sara T. Brookes, Jill DeNardo, Rohit Kochhar, Mark P. Saunders, David Sebag-Montefiore, Paula R. Williamson, and et al. 2018. A core outcome set for clinical trials of chemoradiotherapy interventions for anal cancer (CORMAC): A patient and health-care professional consensus. The Lancet Gastroentorology & Hepatology 3: 865–73. [Google Scholar]

- Goodings, Lewis, Steven D. Brown, and Martin Parker. 2013. Organising images of futures-past: Remembering the Apollo moon landings. International Journal of Management Concepts and Philosophy 7: 263–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Sean, Courtney Armstrong, and Dmitry Khodyakov. 2021. Online modified-Delphi: A potential method for continuous patient engagement across stages of clinical practice guideline development. Journal of General Internal Medicine 36: 1746–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, Sean, Marika Booth, and Dmitry Khodyakov. 2018. Lack of preregistered analysis plans allows unacceptable data mining for and selective reporting of consensus in Delphi studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 99: 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, Barbara, Melanie Jones, David Hughes, and Anne Williams. 1999. Applying the Delphi technique in a study of GPs’ information requirements. Health and Social Care in the Community 7: 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Bill. 2009. Understanding and Researching Professional Practice. Rotterdam: Sense. [Google Scholar]

- Hamlet, Claire, Nichola Rumsey, Heidi Williamson, Karen Johnson, and Charles Nduka. 2018. Consensus research priorities for facial palsy: A Delphi survey of patients, carers, clinicians and researchers. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery 71: 1777–84. [Google Scholar]

- Hasson, Felicity, and Sinead Keeney. 2011. Enhancing rigour in the Delphi technique research. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 78: 1695–704. [Google Scholar]

- Haworth, Simon, Jason Schaub, Elaine Kidney, and Paul Montgomery. 2022. A systematic review of measures of child neglect. Research on Social Work Practice. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helm, Duncan. 2010. Making Sense of Child and Family Assessment: How to Interpret Children’s Needs. London: Jessica Kingsley. [Google Scholar]

- Hines, Denise A., Glenda Kaufman Kantor, and Melissa K. Holt. 2006. Similarities in siblings’ experiences of neglectful parenting behaviors. [Social-Services-Abstracts-Included (SSA Batch-1)]. Child Abuse & Neglect 30: 619–37. [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann, Erik, Mark Cote, and Jefferson Brand. 2018. Research pearls: Expert consensus based evidence using the Delphi method. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic and Related Surgery 34: 3278–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwath, Jan. 2007. Neglect Identification and Assessment. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Horwath, Jan. 2013. Child Neglect: Planning and Intervention. London: Red Globe Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jonson-Reid, Melissa, Chien-Jen Chiang, Patricia Kohl, Brett Drake, Derek Brown, Shenyang Guo, Hyunil Kim, and Timothy McBride. 2019. Repeat reports among cases reported for child neglect: A scoping review. [Social-Services-Abstracts-Maybe (SSA Batch-2)]. Child Abuse & Neglect 92: 43. [Google Scholar]

- JUCSWEC (Joint University Council Social Work Education Committee). 2008. JUCSWEC’s Code of Ethics for Social Work and Social Care Research. Available online: http://www.juc.ac.uk/swec-res-code.aspx (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Jünger, Saskia, Sheila A. Payne, Jenny Brine, Lukas Radbruch, and Sarah G. Brearley. 2017. Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: Recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliative Medicine 31: 684–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeney, Sinead, Felicity Hasson, and Hugh P. McKenna. 2001. A critical review of the Delphi technique as a research methodology for nursing. International Journal of Nursing Studies 38: 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodyakov, Dmitry, Sean Grant, Brian Denger, Kathi Kinnett, Ann Martin, Holly Peay, and Ian Coulter. 2020. Practical considerations in using online modified-Delphi approaches to engage patients and other stakeholders in clinical practice guideline development. The Patient—Patient-Centered Outcomes Research 13: 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodyakov, Dmitry, Sean Grant, Claire Barber, Deborah Marshall, John Esdaile, and Diane Lacaille. 2016. Acceptability of an online modified Delphi panel approach for developing health services performance measures: Results from 3 panels on arthritis research. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 23: 354–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koprowska, Juliet. 2014. Communication and Interpersonal Skills in Social Work. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, Steinar, and Svend Brinkmann. 2015. InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. Loas Angeles: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lacharité, Carl. 2014. Transforming a Wild World: Helping Children and Families to Address Neglect in the Province of Quebec, Canada. Child Abuse Review 23: 286–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Anne C. C., Simon Cousens, Stephen N. Wall, Susan Niermeyer, Gary L. Darmstadt, Waldemar A. Carlo, William J. Keenan, Zulfiqar A. Bhutta, Christopher Gill, and Joy E. Lawn. 2011. Neonatal resuscitation and immediate newborn assessment and stimulation for the prevention of neonatal deaths: A systematic review, meta-analysis and Delphi estimation of mortality effect. BMC Public Health 11: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linstone, Harold A., and Murray Turoff. 2002. The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications. Newark: NIJT. [Google Scholar]

- Linstone, Harold A., and Murray Turoff. 2011. Delphi: A brief look backward and forward. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 78: 1712–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, Mary. 1986. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurse Researcher 35: 382–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, Geraldine M. 2001. Effective Interventions for Child Abuse and Neglect. Chichester: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Meijering, Jurian V., and Hilde Tobi. 2016. The effect of controlled opinion feedback on Delphi features: Mixed messages from a real-world Delphi experiment. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 103: 166–73. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, Paul, Ani Movsisyan, Sean P. Grant, Geraldine Macdonald, and Eva Annette Rehfuess. 2019. Considerations of complexity in rating certainty of evidence in systematic reviews: A primer on using the GRADE approach in global health. BMJ Global Health 4: e000848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrongiello, Barbara A., and Amanda Cox. 2020. Issues in defining and measuring supervisory neglect and conceptualizing prevention. Child Indicators Research 13: 369–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, Tim M., Kimberly C. Kuiper, Claudia E. van der Put, Geert-Jan J. M. Stams, and Mark Assink. 2018. Risk factors for child neglect: A meta-analytic review. Child Abuse & Neglect 77: 198–210. [Google Scholar]

- Munro, Eileen. 2020. Effective Child Protection, 3rd ed. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Office for Standards in Education. 2014. In the Child’s Time: Professional Responses to Neglect; London: Ofsted.

- Oliver, Kathryn, Anita Kothari, and Nicholas Mays. 2019. The dark side of coproduction: Do the costs outweigh the benefits for health research? Health Research Policy and Systems 17: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, So Hyun, Jin Hee Jung, Young Ho Kwak, Jeong Min Ryu, Hyun Noh, Yeon Young Kyong, and Young Joon Kang. 2018. Development of screening tool for child abuse in the korean emergency department using modified Delphi study. Medicine 97: e13724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Jonathan. 2020. Social Work Practice: Assessment, Planning, Intervention and Review, 6th ed. London: Learning Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton, Simon A. 2016. Harmful Societies: Understanding Social Harm. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, Lim Cher, and Tan Seng Chee. 2001. Online discussion boards for focus group interviews: An exploratory study. The Journal of Educational Enquiry 2: 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, Dendy, and Danielle Turney. 2014. Making threshold decisions in child protection: A conceptual analysis. British Journal of Social Work 44: 1472–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, Catherine. 2003. Early indicators of child abuse and neglect: A multi-professional Delphi study. Child Abuse Review 12: 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, Laura J., and Howard Dubowitz. 2014. Child neglect: Challenges and controversies. In Handbook of Child Maltreatment. Edited by Jill Korbin and Richard Krugman. New York: Springer, pp. 27–62. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, Meghan E., Desmond K. Runyan, Sandra L. Martin, and Jonathan B. Kotch. 2017. The within poverty differences in the occurence of physical neglect. Child and Youth Services Review 75: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharley, Victoria. 2020. Identifying and responding to child neglect within schools: Differing perspectives and the implications for inter-agency practice. Child Indicators Research 13: 551–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidebotham, Peter, Marian Brandon, Sue Bailey, Pippa Belderson, Jane Dodsworth, Jo Garstang, Elizabeth Harrison, Ameeta Retzer, and Penny Sorensen. 2016. Pathways to Harm, Pathways to Protection: A Triennial Analysis of Serious Case Reviews 2011 to 2014. London: The Stationery Office. [Google Scholar]

- Smart, Rosanna, and Sean Grant. 2021. Effectiveness and implementability of state-level naloxone access policies: Expert consensus from an online modified-Delphi process. International Journal of Drug Policy 98: 103383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snee, Helene. 2013. Framing the other: Cosmopolitanism and the representation of difference in overseas gap year narratives. British Journal of Sociology 64: 142–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solbjør, Marit, and Aslak Steinsbekk. 2011. User involvement in hospital wards: Professionals negotiating user knowledge. A qualitative study. Patient Education and Counselling 85: 144–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, Olive. 1998. Neglected Children: Issues and Dilemmas. Oxford: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, Olive. 2007. Neglected Children and their Families, 2nd ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Chris, Levent Kirisci, Abigail L. Long, and Peter R. Giancola. 2015. Development and psychometric evaluation of the child neglect questionnaire. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 30: 3343–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, Jackie, and Julie Taylor. 2014. Examining the influence of child neglect on child protection decision-making. Child Care in Practice 20: 383–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltenborgh, Marije, Marian J. Bakermans-Kranenburg, Lenneke R. A. Alink, and Marinus H. van IJzendoorn. 2015. The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: Review of a series of meta-analyses. Child Abuse Review 24: 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Susan. 2000. Child Neglect: Current Definitions and Models—A Review of Child Neglect Research, 1993–1998. Ottowa: Health Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Sykora, Martin, Suzanne Elayan, and Thomas W. Jackson. 2020. A qualitative analysis of sarcasm, irony and related #hashtags on Twitter. Big Data & Society 7: 2053951720972735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, Karen, and Danielle Turney. 2003. What do we know about child neglect? A critical review of the literature and its application to social work practice. Child & Family Social Work 8: 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Kellie. 2016. Strengthening Child Protection: Sharing Information in Multi-Agency Settings. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trocmé, Nico. 1996. Development and preliminary evaluation of the Ontario Child Neglect Index. Child Maltreatment 1: 145–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. 2021. Child Maltreatment 2019; Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. 2022. Child Maltreatment 2020; Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services.

- Uttley, Lesley, and Paul Montgomery. 2017. The influence of the team in conducting a systematic review. Systematic Reviews 6: 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, Angela, and Peter Walsh. 2006. Risk Assessment in Child Welfare. Sydney: NSW Department of Community Services. [Google Scholar]

- Wieringa, Sietse, and Trisha Greenhalgh. 2015. 10 years of mindlines: A systematic review and commentary. Implementation Science 10: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).