5.1. Farm Interviews

Following our initial meetings with B.U.G. farmers, we conducted preliminary semi-structured interviews with farm owners, workers and landowners to explore their thoughts on how the farm could respond to the issue of food inequity in the Glendale neighborhood.

Table 1 provides participant details.

The B.U.G farmers provided the names of all landowners and farm workers and facilitated scheduling. Interviews were held in person at the locations where the farm operates and in landowners’ homes.

Table 2 presents our retroactive organization of the interactional strategies used in initial interviews as they align with our proposed adaptation of Way and colleagues’ typology of dialogic interview strategies (

Way et al. 2015, p. 729). Our framework is also informed by Nardon and colleagues’ conceptualization of therapeutic, emancipatory, and dialogic interview strategies (

Nardon et al. 2021). Since our goal, similar to

Collier (

2015, p. 209), is to “showcase particular kinds of reflexive moments”, we present selected, in-depth examples of participant responses to these interactional strategies.

Member reflections: Establishing familiarity.

For these initial interviews, familiarity was established in two ways: First, one member of the research team was already acquainted with many of the farms’ owners and workers, as she was living at one of the houses where B.U.G. Farms operated at the time of initial interviews. Second, the farmers personally introduced the researchers to any interviewee that we had not already met, which contributed to a sense of familiarity. We suggest that, in lieu of personal connections, researchers may establish this type of familiarity via ethnographic fieldwork. For example, the first and second author volunteered to work with B.U.G. farmers on several occasions throughout this research partnership.

Probing questions: Eliciting transformative memories and visions. In the example responses below, we demonstrate how probing strategies in this category prompted participants to reflect on their reasons for becoming involved with B.U.G. farms, which elicited transformative memories that drove their visions for how the farm could better contribute to the community. For example, participant responses demonstrated varying levels of self-awareness or concern about how urban agriculture, and participants themselves, might be generating negative impacts to the Westside community:

Farmer 1: “It [urban farming] drew me down there, and then once I was there and things were happening, I saw other people looking at buying houses in the neighborhood. So, in some ways B.U.G. farms has acted as a bit of a gentrifying force. Which is tough to justify as a good thing. But we also do our best to not change the neighborhood. We stay low profile, aside from walking up and down the street with carts and food.”

In this interview, the interviewer responded by affirming this concern about gentrification within the Glendale neighborhood, based on her shared experiences as a resident of one of the homes where B.U.G. Farms was operating. This familiarity enabled interviewees to have open conversations about gentrification, which they may not have been so inclined to do with a complete outsider. Because these interviews were semi structured, we also engaged in additional probing questions that prompted member reflections that were unique to each interviewee. For several participants, these strategies prompted reflection on broader structural food issues. For example, one farmer situated their concerns about the export of food from Glendale as related to systemic issues in the food system. During the interviews, participants reflected on the ways that they potentially could (or are not) doing more to address this issue:

Farmer 1: “I do wish that we weren’t simply serving a middle to upper class, from what I can tell largely white to privileged group of people. But I wish it were easier to get our vegetables to a more diverse group of people. The system works against people who already don’t have a lot of money to access good clean food. So, I think the way our economy, and our social society works is a detriment to that goal.”

Farmer 2: “As a whole, I don’t feel like we have much of a relationship [with the community]. I think that [in our neighborhood] we have a decent relationship and people around there see us and recognize and have some sort of idea of what we’re doing, but there’s not really a connection.”

Meanwhile, farmworkers and landowners demonstrated a similar awareness of the export issue within a greater concern about equity across SLC as a whole:

Landowner 1: “Glendale, as you know is a food desert, and [food] it’s being exported out of Glendale for the most part, aside from those of us who are having our land being used to help them grow the food. I think that’s kind of a tragedy you know. I don’t think that’s B.U.G. Farms fault that they have to sell food at the cost that they do to make a decent living, but it’s unaffordable for people in Glendale to just buy a share, I think... Most of that stuff ends up going to more affluent families.”

Farmworker 1: “We strive to be a part of the community as much as we can. I would imagine that some of the long-term residents of the neighborhood may see us as sort of a gentrification threat to the neighborhood. So, [farm owner 1] thinks about how to participate in the neighborhood without totally changing the neighborhood. So, I’d say trying to be involved but remaining aware. Looking for ways to minimize any negative impacts to the neighborhood.”

These quotes demonstrate farm owners, workers, and landowners shared concerns about the farm’s operations within Glendale as well as their recognition of the systemic barriers to food justice that underly the export of food to areas where residents do not face food insecurity at similar rates.

Emancipatory questions: Seeking advice. Emancipatory questions promote social change by prompting participants to question their assumptions and beliefs and challenge their previously articulated views (

Nardon et al. 2021). We implemented this tactic by requesting advice on how our research team might approach issues which the farm was already considering, which contributed to a sense of empathetic consideration:

Farmworker 1: “The idea of subsidized shares could be cool. The volunteering in exchange for veggies options is way more complicated than it seems because there’s often not enough work available on a regular schedule to be done outside of the people who already work there. We had all the help we needed. So, we’d have to figure out a way to make it so you’re not just ‘giving away’ vegetables. Which would be fine too. Maybe that’s how it works with subsidizing if that’s what you’re talking about. I think it would be exciting to figure out a way to have people actually participating in the farm as a way to get veggies. But just handing them out feels a lot more like charity than a genuine engagement.”

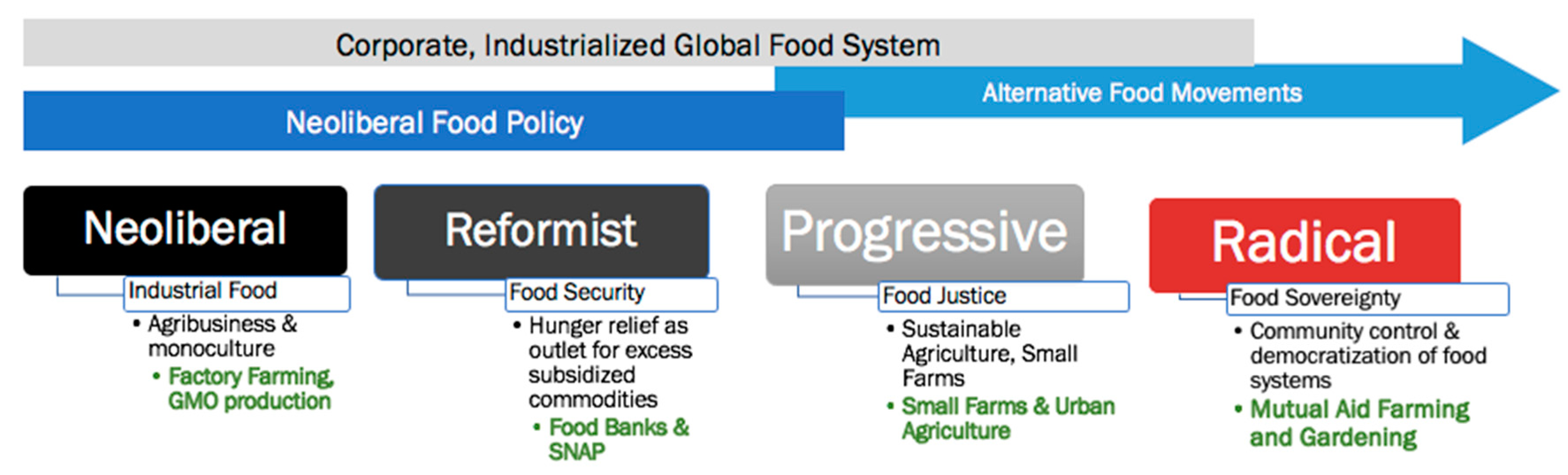

This quote demonstrates how emancipatory questions elicited conversation about moving from food security towards the deeper engagement required in food sovereignty paradigms. In preliminary phases of our research, this prompted the transformation of the research genealogy as we began to consider how our initial suggestion of subsidized shares reflected a food security paradigm. Throughout these initial conversations, interviewees also referenced the shortcomings of local food-access programs designed to address the gap between local food and food security:

Landowner 3: “Just that question that you asked me earlier, about like, I feel like they are conscious people trying to address issues with low-income people having access to organic locally produced food and I think that that’s an important question to ask and to tackle. I think that yeah, food movements are really important and like slow food movements and organic food and organic farming but if it’s only accessible by affluent society then there’s a problem.”

These emergent themes from our interviews with the farmers and landowners shaped our understanding of how structural issues interact with and underly the concerns of the farmers and farmworkers. This information influenced the genealogy of the project by shifting our course from centering on the farm itself to taking a broader view on the issues behind food inequity and the potential for urban agriculture to contribute to food sovereignty. Thus, reflexivity on the part of the farm owners, workers, and landowners informed our decision to undertake further inquiry with several organizations that were conducting food-access work in the community.

5.2. Local Food-Access Advocate Interviews

In order to learn more about what types of food-access and urban agriculture programs had been offered in the Westside, and to understand the varying degrees of success of different programs, we conducted a second round of semi-structured interviews with local food-access advocates. To identify participants, we first worked with our partners at B.U.G. Farms to identify a list of list of prominent organizations conducting food-related work in the Westside with whom the farmers had either previously partnered or were otherwise aware of due to their community connections. To recruit these participants, we contacted individuals either via cold-calls, emails, or outreach through mutual acquaintances. During each interview we also utilized snowball sampling (

Sedgwick 2013) by asking for suggestions on additional contacts, and an introduction if applicable.

Table 3 includes a description of interviewees in this phase.

Due to the small “food advocate” community and a need to maintain anonymity, we use the label “local food advocates” in all example excerpts in this section.

Table 4 presents our interactional strategies for critical reflexivity in semi-structured interviews with local food-access advocates.

Member reflections: Establishing familiarity. We began this round of interviews with a description of our partnership with B.U.G. Farms and our intent to explore how the farm could better attend to food equity in the Glendale neighborhood. We also described how we initially interpreted data to indicate that subsidized shares would be a good option, but later realized that this might not align with community members’ visions. This transparency gently introduced ideas of food sovereignty by outlining our progression from a food security paradigm to more food justice- and sovereignty-oriented perspectives. In retrospect, we considered that this strategy encouraged interviewees to share similar transformative experiences.

Probing questions: Transformative memories. Prompting strategies that encouraged participants to consider success and barriers in their work caused many interviewees to reflect on transformative memories wherein they questioned the efficacy of local food-advocacy programs. In the following excerpt, an interviewee reflects on an effort to establish a community garden that resulted in very little community participation:

Local Food-Access Advocate 2: “We tried [a community garden]. We couldn’t get anyone from here to there… everyone was so excited about it. [Saying] “I have all these foods I want to grow from my country and my land.” But yet we couldn’t get anyone to do it! So, it’s like even that, right, like there’s actual land access. And I know it’s not from lack of desire. I know they want it, but what are the other barriers…? Transportation was one thing for some people. Time. For sure. Right, it takes a lot of time and people are trying to survive. And who has the luxury of growing food? You know, it’s time consuming. And so, these were just some of the things that we were hearing. The passion was there, the interest was there…it was all there. But we couldn’t get the wheels going. So, I ended up taking over the garden. Which is awful…from a community organizer perspective we failed. I ended up doing the work. So, we stopped that.”

This excerpt provides insight into a therapeutic process as this interviewee considers potential reasons for a lack of community participation. Similarly, probing questions about how participants viewed themes or patterns in local food advocacy evoked therapeutic reflections about the disconnect between food-access programs and local food promotion, such as in the following excerpt:

Local Food-Access Advocate 1: “Most of our funding was based on this idea of making local produce available. And maybe trying to solve both of those problems [hunger and local food access] at the same time was a really big mistake… What we realized too, was that most of the consumption that was happening of the produce was coming from staff at those centers. They weren’t people who didn’t have access to produce [so], weren’t serving anyone, we were serving mostly people doing food access work…Who wanted to see better, and I think that is one of the problems right, is there is a group of people who feel like yes, we need better food access in this neighborhood, and I often wonder if those people who we feel like need better food access in that neighborhood actually feel like they need better food access.”

Here, the interviewee shares a transformative memory, revisiting misalignment with community needs and lessons learned from previous food-access initiatives. As in other interviews, they also recognize and question food-access advocates’ roles in how food security paradigms may function to reinscribe food insecurity.

Emancipatory questions. Emancipatory interview strategies enable a dialogue in which interviewers and interviewees inform and encourage each other to articulate and question assumptions and beliefs (

Nardon et al. 2021). One strategy to elicit these outcomes is to prompt interviewees to imagine new or different scenarios. We enacted this strategy by seeking advice on how researchers might proceed with future food-access inquiry. Given the opportunity to reimagine past approaches and provide advice, several interviewees drew on transformative memories that were elicited throughout the interview to inform their suggestion on how researchers or others might rewrite food advocacy work:

Local Food-Access Advocate 1: “I think you have to step the whole conversation back and remove a bunch of the assumptions that we are often entering these conversations with…. the longer I’ve done this, the more I’ve realized how complex of a problem it really is…one of the things we find out when we’re doing food access or food consumption or health equity type work, is that you can’t solve these problems because they’re not like health equity problems they’re equity problems. And like, how do you solve the problem that people shouldn’t have to work two jobs to be able to survive?...

It seems like people are like oh we should host cooking classes, or we should tell people that eating fruits and vegetables is healthy. But I don’t know that those folks don’t know that eating fruits and vegetables is healthy… I have a hard time also thinking that most of those [nonwhite] cultures don’t know how to cook. It just seems like a little bit of a ridiculous assumption. Nobody comes to my neighborhood and teaches cooking classes. And I’m guessing that there’s less people that know how to cook in my neighborhood than in those neighborhoods.”

This excerpt represents a particularly honest conversation around the failures that drove an underutilized food-access program in Glendale and points to a larger pattern in food security initiatives that are not based in systemic change. Contextually, this interview also revealed some persistent language patterns that manifested throughout this project. Most notable is the respondents’ separation between “us” and “them” that is reflected within the conversation. Even though the interviewee was very insightful about some of the missteps within the work they had been involved in, the language itself illustrates problematic power dynamics. In several interviews, there seemed to be an ingrained recognition of difference that perhaps did not apply to the researchers, or people who were assumed to not live in the Westside.

Following the interview, when we turned off the recorder, the interviewee engaged in further dialogue about transformative memories by discussing the role of stigma and shame in food-access programs. This had manifested in feedback their organization had received regarding how many Glendale residents had been reluctant to utilize their programs, because they were unclear whether the food offered was free, low-cost, or full price. In sharing this memory, the interviewee realized that they had not adequately accounted for the impact of the stigma around “free food”, which was likely why many people had not turned up to utilize programs. Along with insights derived in this phase of interviews, this directed a shift in the genealogy of our project once again, illuminating a need to align the project more deeply with community members’ visions for food equity.

5.3. Interviews as Intervention

Insights gleaned from the first and second round of interviews with food advocates and fieldwork uncovered a need to divest from assumptions about community needs and/or deficit-oriented research approaches that can lead to simplistic solutions (

Patel 2015). The first semi-structured phase of interviews uncovered some common barriers faced by local food advocates, many of which were rooted in food security paradigms. This preliminary data enabled us to craft follow-up interviews that might better introduce ideas about food justice and sovereignty in situ. Thus, in the spirit of transformation sparked by our community field work, we designed a second interview for food advocates to further explore interactional strategies for food sovereignty. Interviewees were recruited again through snowball sampling (

Sedgwick 2013), which enabled researchers to contact nearly the total population of small farmers that were growing within Salt Lake City boundaries at the time, and the majority of food-access advocates and organizations that those farms worked with or suggested we interview (see

Table 5). We tried to reinterview participants of several of the same organizations that were included in our initial interviews. However, due to significant organizational turnover in the two-year period between initial and follow-up interviews, we reinterviewed only five of the original thirteen individuals from our initial interviews (some of which were in new roles with different organizations). Notably, this change in leadership also occurred at B.U.G. Farms, as a new owner, who continued a working partnership with our research team, took over the operation in late 2019.

While we designed the final round of interviews with intervention in mind, we again retroactively drew on the

Way et al. (

2015) typology of dialogic interview strategies (p. 729) to organize our prompts and propose a framework of interactional strategies for food sovereignty. In this third and final phase, we prompted participants to share transformative memories by asking about how the first round of interviews impacted their thinking. We also expanded the scope in this second round of interviews, as we were simultaneously studying the impacts of COVID-19 on the local food system.

Table 6 presents the interactional strategies we used in this phase to prompt transformation through the exploration of how the COVID-19 pandemic sparked change in interviewees’ visions for increased food equity through urban agriculture in the future.

Member reflections. Opening with a personal question about how participants initially became engaged in food-related work prompted a reflection of interviewees’ core commitments and encouraged connection between the interviewees and their personal lives. For example, this interviewee connected their personal experiences with food to their current work:

Interviewer: “What are the motivations that you have for the work you do... the reasons that are more personal, not necessarily professional?”

Local Food Advocate 3: “Several little tidbits in my life. One is as a child, there were seasons that my family was food insecure. How we handled that, a lot of that was we were able to create a garden. We always had a fresh vegetable garden…Also I have close friends and family members who had physical illnesses that couldn’t be resolved without access to fresh food… So, I have a real passion… that everyone should have access to… highly dense and nutritious food. So, I just, I’ve seen it firsthand. I’ve lived it.”

The following excerpt represents a similar member reflection:

Interviewer: “What are the motivations that you have for the work you do... the reasons that are more personal, not necessarily professional?”

Local Food-Access Advocate 4: “Personally, I think that food just has like a major role in my family because growing up like, we didn’t really have a lot of access to food because we just like immigrated here and my parents like didn’t really have steady source of income so they always tried to make do with whatever we could find. So, I understand a lot of the time people are also having these struggles of like balancing between finances like work, kids, family and things like that. So that’s part of the reason why I’m so passionate about food.”

These excerpts reflect a general pattern through which interviewees, when prompted, reflected on the reasons that they became activated in food advocacy, which set a personal or vulnerable tone for the conversation. These prompts helped to establish a sense of familiarity between the interviewee and interviewer(s), as people reflected on transformative life experiences as an entryway into their conversations about food access. This primed interviewees to engage in critical reflexivity before taking up more challenging questions.

Probing questions: Changed self. Probing questions can promote therapeutic dialogue and prompt participants to recraft narratives, better understand their situations, and result in a sense of changed self (

Nardon et al. 2021). Dialogic markers of therapeutic and change-based processes can include participant “talk repair” and disfluencies that occur in conversation (

Way et al. 2015). This type of narrative recrafting occurred when we asked interviewees how they could contribute to increased food equity or to realizing their own visions for an ideal food system in SLC. For example, one farmer who felt that increased education was the pathway towards a more equitable food system considered what it might look like for her farm to support this vision further:

Interviewer: “What do you think that your farm or you personally could do to support that vision?”

Farmer 5: “I think we’re doing everything we can right now to support that vision. But I think—What I think the farm does. I think what we, I can do personally is be a dog with a bone on this and just really keep pushing it. That we need to get legislation, we need to get policy in place and educate people… we need to get that information out to the general public. Because a lot of people think “farming? I don’t have any interest in it… But they have interest in eating. And so, they don’t understand the connection.”

In this excerpt, a farmer exhibits talk repair and disfluencies while forming new or changed thoughts via the interview process. This type of dynamic reflection was also elicited in our exploration of how gender roles interact with participants’ work. It is worth noting that this question was added in response to a participant request, which we found prompted critical reflexivity for many participants in situ, as they had not previously been prompted to consider gender roles in their work. For example, one participant engaged in reflexivity about how gender roles impact emergency food distribution at resource centers:

Local Food-Access Advocate 5: “I’m nonbinary and donating [garden produce] for the Women’s Resource Center… just makes me keep on thinking about how these systems of gender [have] kind of been devised to keep the white man in power and then there’s like everybody else. And there’s so much diversity of gender experience…I’m glad you’re asking this question in this research too because it’s like, this is the story that gets erased… why are we growing this food to be accessed, like who gets to access it? What kind of hoops do you have to jump through... how do you have to like, victimize yourself as a woman or something? I don’t know …and that actually makes me think about the policies that are getting talked about and like identifying trans and outing trans people in shelters and stuff like that where it’s just like, the gendering is so violent feeling sometimes. Yeah, and [at my workplace] there’s been a lot of discussion about supporting trans people and trans homeless people... as a part of that [coworker] and I have been able to talk to people about our goals with the garden [at our workplace] being part of that conversation... we’ve been kind of doing this all along but not intentionally. So, we have to actually make it even more like a support system and not just a passive like only conditionally supporting people just because we’re there but like actively, you know, stepping behind that.”

In this case, the participant considers how gender roles impact their work, and through critically reflexive dialogue, arrives at a commitment to encourage their workplace to bolster support for food access amongst gender diverse populations. Probing questions can also be used to provoke transformative memories. For example, when asked how being previously interviewed and or otherwise involved with this project impacted participants, people reflected on this in various ways:

Interviewer: “What do you remember from our first interview?”

Farmer 1: “I remember feeling like you guys were asking questions that we had thought about before, and feeling like excited that like something, someone was looking into that other than like me spiraling about it in my brain all the time and having, you know, general white guilt about it or a general like feelings about like that. I should be doing more. And other people were thinking about it in the community… I mean, I remember even thinking about it at [my off-farm job] and [thinking] why, why am I growing all of this. How can we help other people access it? And it sort of…stayed in my mind.”

Interviewer: “How has your involvement with this project impacted your work?”

Local Food-Access Advocate 6: “[It has] helped me kind of shape the thought process of growing a certain type of food and hearing how some people like to eat different things… Like we started growing tons and tons of hot peppers although none of us can tolerate them. We realize that other people really like peppers, so we have to grow them. So, that, again, cemented the idea of how we have to grow a wide variety of things, and we have to keep an open mind of what can be grown.

Interviewer: “How has your involvement with this project impacted your work?”

Farmer 3: “All of the conversations we have had get your mind thinking about things. I think you guys are right on track with the questions about this…asking our customers more questions [like] in the survey and then we had customers email us and talk to us about those questions and that was interesting to see that spurred thoughts and conversations in them. It also, sort of, shifted ways we were thinking of being involved with customers…I wouldn’t have heard from those people or other people had you guys not asked those questions…[there were] so many unexpected answers to the questions asked, and it was helpful for us and helped put us in a different direction.”

These excerpts point to the rippling effect that critically reflexive research can offer, providing a particularly poignant look at how interactional strategies in the research process can result in changes throughout the community.

Emancipatory questions: Visions for an ideal food system. Here, we implement frameworks of desire (

Tuck 2009) by prompting interviewees to envision an ideal food system future that they would like to see and to consider how they might personally contribute to it. This type of “magic wand” question enables participants to imagine what they might do if they had a magic wand that could change anything, a technique which “allows participants to ignore real or imagined constraints and think outside immediate considerations” (

Way et al. 2015, p. 728) and envision scenarios which they currently do not believe to be possible:

Local Food Advocate 8: “Distribution of food, I think, is a problem because it’s based on the whole capitalist model where everybody who has anything to do with getting food from the plants that they grow into the bellies of the organisms that consume the food is expecting to get a percentage to make money from every step along the chain. And so, I think an ideal food system…couldn’t exist in the purely cutthroat capitalist society we live in now.”

Another participant envisions an entirely different world as well:

Local Food Advocate 5: “I’m thinking about all the seeds from the seed library bursting throughout the valley. I want to see those burst everywhere, not just on the east side or in wealthier neighborhoods but everywhere…my dream is for everyone to have enough… for there to be true equity. [And] I dream of defunding the police and funding everything else. There’s not a lot of precedence for actually giving money to public health resources and so we might as well try. Doesn’t seem like it would hurt. I just trust that there’s a lot of people that could really be entrusted with resources to grow food and grow community and make art [and] foster life and all the things that help us stay inspired to live with each other in compassionate ways.”

We also utilize emancipatory questioning by asking participants to “imagine an opposite” and describe how they feel that other groups of people could contribute to more equitable food systems. As the excerpts below demonstrate, this strategy can prompt participants to reconnect their suggestions for a hypothetical other with potential individual actions for themselves. For example, when asked how small farmers could contribute to participants’ visions for a more equitable food system, one interviewee considered a series of food systems disconnects, and via talk repair, questions how they might use food as connective remedy.

Interviewer: What about farmers, local farmers? What can they do?

Local Food Advocate 7: “I think overall, a lot of these issues are far too politicized, that the one thing that we should all be able to agree on is that people have access to food, regardless of what your political or affiliation or your political leanings are… Because I think people feel alienated…. And I mean, I think I myself am part of the problem with that. And I don’t know how we change that dynamic… maybe that’s the thing that we all share, is actually we all have powerful experiences that are connected to food…is there a way for food, the thing that can help us bridge these political and policy gaps? And how do we do that? And, you know, expecting a farmer who is growing apples in the middle of a rural community to, um, have a race equity or a food equity conversation... What do we need to do to bring them to that, you know, instead of expecting people to come to us all the time? I mean, I’m just thinking out loud. I’ve never said these words before in my life, so just forgive me if I’m way off…But how do we go to people instead of expecting them to come to us? Without compromising the values that we hold and the reasons why we’re doing this work and the reasons why we’re having this conversation; how do we entice them to join us in this conversation? And I don’t know the answer to that. And it’s a good question.”

In this excerpt, therapeutic dialogue occurs, as the interviewee responds to probing questions by verbally organizing and subsequently reframing their beliefs. These types of outcomes demonstrate how interactional strategies for critical reflexivity can enable us to envision new worlds with ways of knowing that we do not yet possess and prompt consideration of the first steps we might take to get there. Therein is the work of radical food sovereignty, which calls for dreaming and fighting for new futures while participating in direct action to alleviate the suffering of the present (

Agyeman and McEntee 2014;

Heynen 2009;

Holt-Giménez and Wang 2011;

Martínez-Torres and Rosset 2010;

Whyte 2017).