The Fear of War Scale (FOWARS): Development and Initial Validation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Objective of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

Development of the Fear of War Scale (FOWARS)

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

3.2. Reliability/Internal Consistency

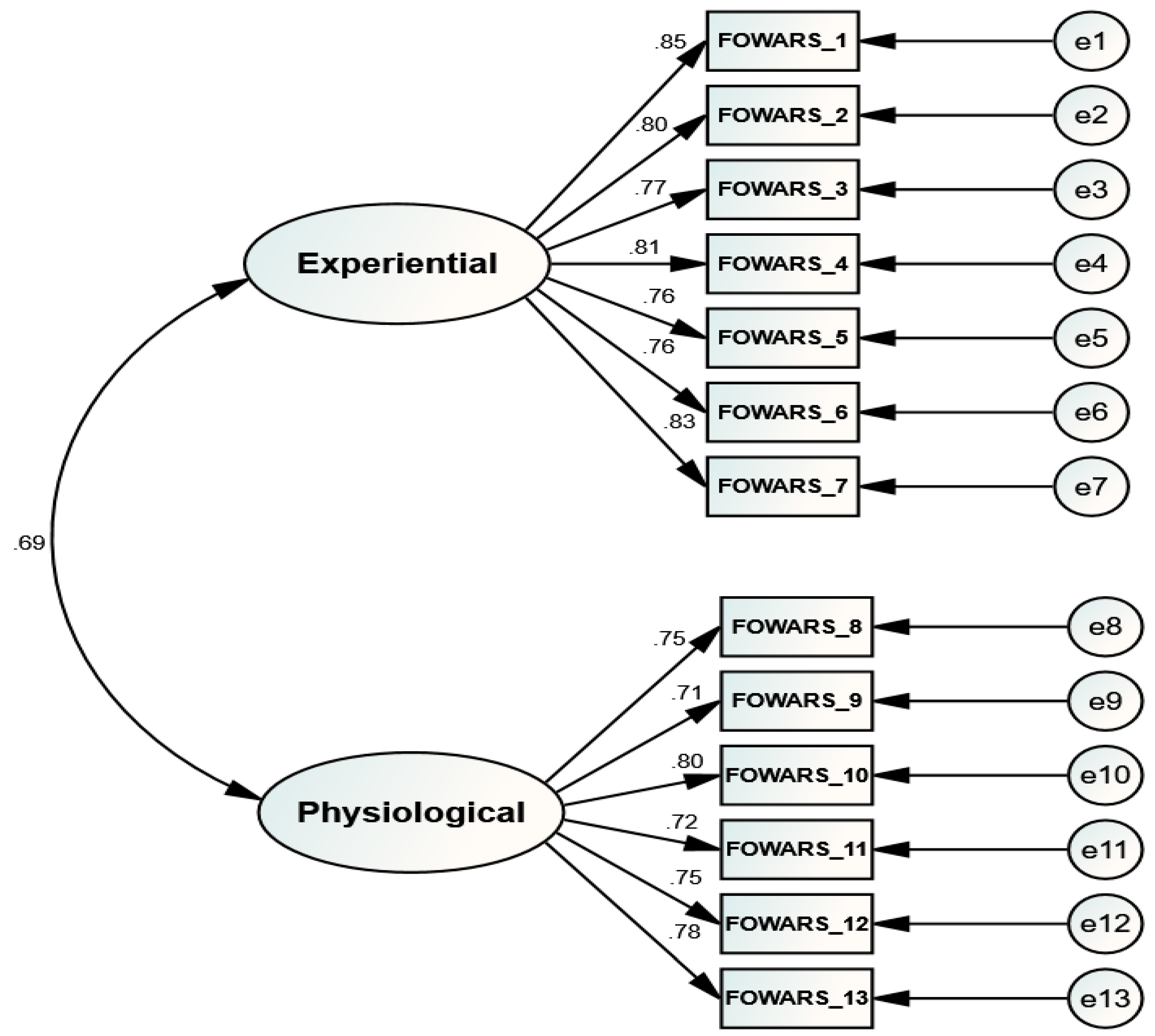

3.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.4. Construct Validity (Convergent Validity)

3.5. Construct Validity (Differentiation by Groups)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahorsu, Daniel Kwasi, Chung-Ying Lin, Vida Imani, Mohsen Saffari, Mark D. Griffiths, and Amir H. Pakpour. 2020. The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Development and Initial Validation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 20: 1537–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- APA Dictionary of Psychology. n.d. Dictionary.apa.org. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/fear (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Armstrong-Jones, Robert. 1917. The Psychology of Fear and the Effects of Panic Fear in War Time. Reprinted Journal of Mental Science 63: 346–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, David H. 2002. Anxiety and Its Disorders: The Nature and Treatment of Anxiety and Panic, 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, Roy F., Ellen Bratslavsky, Catrin Finkenauer, and Kathleen D. Vohs. 2001. Bad is Stronger than Good. Review of General Psychology 5: 323–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, Godfred O., Torsten B. Neilands, Edward A. Frongillo, Hugo R. Melgar-Quiñonez, and Sera L. Young. 2018. Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioral Research: A Primer. Frontiers in Public Health 6: 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehnke, Klaus, and Shalom H. Schwartz. 1997. Fear of war: Relations to values, gender, and mental health in Germany and Israel. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 3: 149–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredemeier, Keith, Kerry McCole, Lauren Luther, Aaron T. Beck, and Paul M. Grant. 2018. Reliability and Validity of a Brief Version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale in Outpatients with Psychosis. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment 41: 221–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, Michael W., and Robert Cudeck. 1989. Single Sample Cross-Validation Indices for Covariance Structures. Multivariate Behavioral Research 24: 445–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhr, Kristine, and Michael J. Dugas. 2002. The intolerance of uncertainty scale: Psychometric properties of the English version. Behaviour Research and Therapy 40: 931–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzan, Barry. 2009. People, States and Fear, 2nd ed. Colchester: ECPR Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carleton, R. Nicholas, and Gordon J. G. Asmundson. 2009. The multidimensionality of fear of pain: Construct independence for the fear of Pain Questionnaire-Short Form and the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale-20. The Journal of Pain 10: 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carleton, R. Nicholas, M. A. Peter J. Norton, and Gordon J. G. Asmundson. 2007. Fearing the unknown: A short version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 21: 105–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, Michael A. 1991. Developing a measure of nuclear war anxiety: A factor analytic study. Humboldt Journal of Social Relations 16: 39–63. [Google Scholar]

- Council on Foreign Relations. 2022. Conflict in Ukraine. Global Conflict Tracker; Council on Foreign Relations. Available online: https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/conflict-ukraine (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Coyne, Christopher J., and Rachel L. Mathers, eds. 2011. The Handbook on the Political Economy of War. Northampton: Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar]

- Fergus, Thomas A., and Kevin D. Wu. 2012. The Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. Assessment 20: 555–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Álvarez, Javier, Amanda Díaz-García, Desirée Colombo, Cristina Botella, Pietro Cipresso, and Giuseppe Riva. 2022. Technological Interventions for Emotion Regulation. Comprehensive Clinical Psychology, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, Andy P. 2009. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Franke, Hillary A. 2014. Toxic Stress: Effects, Prevention and Treatment. Children 1: 390–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, Ute. 2003. The Psychology of Fear of Crime. Conceptual and Methodological Perspectives. British Journal of Criminology 43: 600–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, Darren, and Paul Mallery. 2010. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference. 17.0 Update (10a ed.). Boston: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, Julie D., and John R. Crawford. 2005. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology 44: 227–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, Daire, Joseph Coughlan, and Michael R. Mullen. 2008. Structural Equation Modelling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 6: 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Jankovic, Slobodan M., Gordana V. Antonijević, Snježana N. Mirković, Katarina M. Raspopović, Ljiljana R. Radoičić, Srđan S. Putnik, Marija N. Živković-Radojević, Ivana R. Vasic, Boško V. Nikolic, Dragan R. Stanojevic, and et al. 2020. Surgical Fear Questionnaire (SFQ)—Serbian cultural adaptation. Vojnosanitetski Pregled 77: 1266–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, P. 2022. Why Has Russia Invaded Ukraine and What Does Putin Want? BBC News. March 2. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-56720589 (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Kotta, Ibolya, Kinga Kalcza-Janosi, Kinga Szabo, and Eszter Eniko Marschalko. 2021. Development and Validation of the Multidimensional COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Scale. Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics 18: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lederer, David. 2012. Fear of the Thirty Years War. Facing Fear 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Chan Jean, and Eduardo B. Andrade. 2011. Fear, Social Projection, and Financial Decision Making. Journal of Marketing Research 48: S121–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jiyeon, Eun-Hyun Lee, and Seung Hei Moon. 2019. Systematic review of the measurement properties of the depression anxiety stress scales–21 by applying updated COSMIN methodology. Quality of Life Research 28: 2325–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loo, Robert, and Leisa Shea. 1996. Structure of the Collett-Lester Fear of Death and Dying Scale. Death Studies 20: 577–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovibond, Peter F., and Sydney H. Lovibond. 1995. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. Sydney: School of Psychology, University of New South Wales. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Faxiang, Reza Ghanei Gheshlagh, Sahar Dalvand, Sholeh Saedmoucheshi, and Qingyun Li. 2021. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Fear of COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 661078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lybarger, Jeremy. 2020. The Threat of Nuclear War. Apa.org. Available online: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2018/03/nuclear-war (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Meiselman, Herbert L. 2016. Emotion Measurement. Emotion Measurement, 645–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, John S. 2017. Toxic stress and child refugees. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing 23: e12200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, Babak, Chia-Wei Fan, William J. Boone, Mark D. Griffiths, Chung-Ying Lin, and Amir H. Pakpour. 2020. Validating the Persian Intuitive Eating Scale-2 Among Breast Cancer Survivors Who Are Overweight/Obese. Evaluation and the Health Professions 44: 385–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallant, Julie. 2013. SPSS Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS for Windows. New York: Mcgraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Poikolainen, Kari, Terhi Aalto-Setälä, Annamari Tuulio-Henriksson, Mauri Marttunen, and Jouko Lönnqvist. 2004. Fear of nuclear war increases the risk of common mental disorders among young adults: A five-year follow-up study. BMC Public Health 4: 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preventing a Wider European Conflict. n.d. Council on Foreign Relations. Available online: https://www.cfr.org/report/preventing-wider-european-conflict (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Ropeik, David. 2004. The consequences of fear. EMBO Reports 5: S56–S60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severino, Giovanina A., and W. David G. Haynes. 2010. Development of an Italian version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales. Psychology, Health and Medicine 15: 607–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shern, David L., Andrea K. Blanch, and Sarah M. Steverman. 2016. Toxic stress, behavioral health, and the next major era in public health. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 86: 109–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stănculescu, Elena. 2022. Fear of COVID-19 in Romania: Validation of the Romanian Version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale Using Graded Response Model Analysis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 20: 1094–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Surzykiewicz, Janusz, Sebastian Binyamin Skalski, Małgorzata Niesiobędzka, Olga Gladysh, and Karol Konaszewski. 2022. Brief screening measures of mental health for war-related dysfunctional anxiety and negative persistent thinking. Personality and Individual Differences 195: 111697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, Marianna. 2010. The short version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Factor structure in a young adolescent sample. Journal of Adolescence 33: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, Barbara G., and Linda S. Fidell. 2013. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed. Boston: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- The Science of Emotion: Exploring the Basics of Emotional Psychology. 2019. UWA Online. June 27. Available online: https://online.uwa.edu/news/emotional-psychology (accessed on 20 April 2023).

- Tran, Thach Duc, Tuan Tran, and Jane Fisher. 2013. Validation of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) 21 as a screening instrument for depression and anxiety in a rural community-based cohort of northern Vietnamese women. BMC Psychiatry 13: 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzur Bitan, Dana, Ariella Grossman-Giron, Yuval Bloch, Yael Mayer, Noga Shiffman, and Shlomo Mendlovic. 2020. Fear of COVID-19 scale: Psychometric characteristics, reliability and validity in the Israeli population. Psychiatry Research 289: 113100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, Robert J. 2006. Introduction: Statistical and Methodological Myths and Urban Legends. Organizational Research Methods 9: 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Brett, Andrys Onsman, and Ted Brown. 2010. Exploratory factor analysis: A five-step guide for novices. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine 8: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Nathalie E., Dirgha Ghimire, and Karen A. Snedker. 2018. Fear of violence during armed conflict: Social roles and responsibilities as determinants of fear. Social Science Research 71: 145–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Emily J., Lexine Stapinski, David M. Dueber, Ronald M. Rapee, Amy L. Burton, and Maree J. Abbott. 2020. Psychometric properties of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale-12 in generalized anxiety disorder: Assessment of factor structure, measurement properties and clinical utility. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 76: 102309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group A (n = 670) | Group B (n = 461) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M ± SD) | 18–71 (38.53 ± 11.56) | 18–72 (45.04 ± 12.79) | |

| Gender | Female | 622 (92.8%) | 419 (90.9%) |

| Male | 48 (7.2%) | 42 (9.1%) | |

| Country | Hu | 458 (68.4%) | 395 (85.7%) |

| Ro | 212 (31.6%) | 66 (14.3%) | |

| Education level | 10 grades/grade 10 or less | 8 (1.2%) | 14 (3%) |

| High school/baccalaureate | 173 (25.8%) | 130 (28.2%) | |

| College, university | 304 (45.4%) | 222 (48.2%) | |

| Master’s degree | 160 (23.9%) | 84 (18.2%) | |

| Doctor’s degree | 25 (3.7%) | 11 (2.4%) | |

| Residency | Capital city | 259 (38.7%) | 162 (35.1%) |

| City | 294 (43.9%) | 208 (45.1%) | |

| Village | 117 (17.5%) | 91 (19.7%) | |

| DASS (M ± SD) | Depression | 0–21 (6.54 ± 5.88) | - |

| Anxiety | 0–20 (4.50 ± 4.57) | - | |

| Stress | 0–21 (8.46 ± 5.84) | - | |

| IUS (M ± SD) | 12–60 (35.51 ± 10.82) | - | |

| FOWARS (M ± SD) | Total scale | 1–5 (3.05 ± 0.88) | 1–5 (2.64 ± 0.94) |

| Experiential subscale | 1–5 (3.79 ± 0.93) | 1–5 (3.34 ± 1.11) | |

| Physiological subscale | 1–5 (2.19 ± 1.06) | 1–5 (1.84 ± 0.95) |

| Item | Components | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | 2. | |

| 1. Félek, mert tudom, hogy a háború emberi életekbe kerül. 1 (I am scared because I know war costs human lives.) 2 | 0.783 | 0.498 |

| 2. Félek, hogy a háború hosszasan elhúzódik. 1 (I am afraid that the war will drag on for a long time.) 2 | 0.777 | 0.502 |

| 3. Attól tartok, hogy a béketárgyalások eredménytelenek lesznek. 1 (I fear that the peace talks will be fruitless.) 2 | 0.716 | 0.417 |

| 4. Félek attól, hogy a világ már nem lesz biztonságos hely. 1 (I am afraid the world will no longer be a safe place.) 2 | 0.752 | 0.489 |

| 5. Kényelmetlenül érzem magam, ha a háborúra gondolok. 1 (I feel uncomfortable when I think of the war.) 2 | 0.755 | 0.555 |

| 6. Aggódom a háború súlyos következményei (gazdasági, politikai stb.) miatt. 1 (I am concerned about the serious consequences of the war (economic, political, etc.).) 2 | 0.667 | 0.433 |

| 7. Félek attól, hogy kitör a nukleáris háború. 1 (I am afraid that a nuclear war will break out.) 2 | 0.679 | 0.451 |

| 8. Remegni kezdek, amikor arra gondolok, hogy ide is elér a háború. 1 (I start to tremble when I think the war reaches here, as well.) 2 | 0.424 | 0.746 |

| 9. Izzad a tenyerem, ha arra gondolok, hogy a háború bennünket is elér. 1 (My palms sweat when I think the war will reach us too.) 2 | 0.459 | 0.743 |

| 10. A szívem gyorsabban ver (pulzusom megnő) amikor arra gondolok, hogy nálunk is kitör a háború. 1 (My heart is beating faster (my heart rate is rising) when I think the war will break out in our country too) 2 | 0.450 | 0.722 |

| 11. Alvászavarom van, mert aggódom, hogy ide is elér a háború. 1 (I have a sleep disorder because I am worried the war will get to us too.) 2 | 0.581 | 0.803 |

| 12. Kiráz a hideg (libabőrös leszek), amikor arra gondolok, hogy nálunk is kitör a háború. 1 (It gives me the creeps (I get goose bumps) when I think the war will break out here too.) 2 | 0.510 | 0.726 |

| 13. Felfordul a gyomrom (hányingerem, gyomoridegem van), amikor arra gondolok, hogy nálunk is kitör a háború. 1 (It makes me sick to the stomach (I have nausea, stomach upset) when I think the war will break out here too.) 2 | 0.522 | 0.725 |

| Eigenvalues | 6.392 | 1.639 |

| % of variance | 49.167 | 12.605 |

| α | 0.888 | 0.883 |

| α total scale | 0.912 | |

| Variable | M | SD | S | K | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. FOWARS | 3.05 | 0.88 | −0.115 | −0.534 | 1 | |||||

| 2. Experiential subscale | 3.79 | 0.93 | −0.878 | 0.318 | 0.89 *** | 1 | ||||

| 3. Physiological subscale | 2.19 | 1.06 | 0.681 | −0.496 | 0.89 *** | 0.59 *** | 1 | |||

| 4. Depression | 6.54 | 5.88 | 0.719 | −0.596 | 0.57 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.53 *** | 1 | ||

| 5. Anxiety | 4.50 | 4.57 | 1.153 | 0.688 | 0.64 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.68 *** | 0.70 *** | 1 | |

| 6. Stress | 8.46 | 5.84 | 0.241 | −0.977 | 0.65 *** | 0.57 *** | 0.58 *** | 0.76 *** | 0.73 *** | 1 |

| 7. Intolerance of uncertainty | 35.51 | 10.82 | 0.079 | −0.667 | 0.61 *** | 0.57 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.63 *** | 0.57 *** | 0.63 *** |

| Variable | FOWARS Total | Experiential Subscale | Physiological Subscale | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

| Gender | Male (n = 48) | 2.41 (0.86) | 3.10 (1.08) | 1.60 (0.81) |

| Female (n = 622) | 3.10 (0.87) | 3.84 (0.90) | 2.24 (1.06) | |

| t (df) | −5.31 (668) | −5.36 (668) | −5.13 (60.22) | |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Hedges’s g | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.61 | |

| Country | Romania (n = 212) | 2.87 (0.86) | 3.63 (0.92) | 1.98 (0.99) |

| Hungary (n = 458) | 3.14 (0.88) | 3.86 (0.93) | 2.29 (1.07) | |

| t (df) | −3.59 (668) | −2.90 (668) | −3.52 (668) | |

| p | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Hedges’s g | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.30 | |

| Residency | Capital city (n = 259) | 3.07 (0.88) | 3.81 (0.94) | 2.21 (1.03) |

| City (n = 294) | 3.01 (0.89) | 3.75 (0.96) | 2.15 (1.04) | |

| Village (n = 117) | 3.11 (0.88) | 3.79 (0.84) | 2.27 (1.13) | |

| F (df) | 0.67 (2, 667) | 0.51 (2, 667) | 0.59 (2, 667) | |

| p | 0.508 | 0.597 | 0.555 | |

| Educational level | 10 grades/grade 10 or less (n = 8) | 2.73 (0.78) | 3.41 (0.72) | 1.93 (1.07) |

| High school/baccalaureate (n = 173) | 3.04 (0.94) | 3.71 (1.00) | 2.22 (1.09) | |

| College, university (n = 304) | 3.10 (0.89) | 3.82 (0.94) | 2.27 (1.07) | |

| Master’s degree (n = 160) | 2.99 (0.80) | 3.79 (0.82) | 2.06 (0.98) | |

| Doctor’s degree (n = 25) | 2.97 (0.87) | 3.82 (1.06) | 1.98 (0.99) | |

| F (df) | 0.78 (4, 665) | 0.50 (4, 665) | 1.52 (4, 665) | |

| p | 0.536 | 0.734 | 0.194 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kalcza-Janosi, K.; Kotta, I.; Marschalko, E.E.; Szabo, K. The Fear of War Scale (FOWARS): Development and Initial Validation. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050283

Kalcza-Janosi K, Kotta I, Marschalko EE, Szabo K. The Fear of War Scale (FOWARS): Development and Initial Validation. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(5):283. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050283

Chicago/Turabian StyleKalcza-Janosi, Kinga, Ibolya Kotta, Eszter Eniko Marschalko, and Kinga Szabo. 2023. "The Fear of War Scale (FOWARS): Development and Initial Validation" Social Sciences 12, no. 5: 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050283