1. Introduction

Globalization can be understood as a variable structural characteristic of any network in which long-distance (“global”) links are becoming denser relative to the density of less distant (local) links, or as a proportion of all links. This definition of globalization as

large-scale connectedness is similar to Charles Tilly’s definition of globalization—“an increase in geographic range of locally consequential social interactions, especially when that increase stretches a significant proportion of all interactions across international or intercontinental limits” (

Tilly 1995, pp. 1–2). Tilly was talking about spatial expansion over time, but a nonexpanding network can also become more (or less) globalized if the ratio of long-distance to local links increases or decreases.

Structural globalization as an objective variable characteristic of world society is very different from the “globalization project” of capitalist neoliberalism—a political and economic program that has supported policies such as deregulation, privatization, the alleged superiority of market forces, monetization, free flows of investment capital and attacks on welfare programs and labor unions. The rise of neoliberalism in the 1970s (Reaganism/Thatcherism and the “Washington Consensus”) replaced Keynesian national development as the predominant developmental ideology in local, national and international contexts (

Harvey 2005;

McMichael 2017;

Mittelman, forthcoming). This is what most people think of as globalization, and the history and current incarnations of this developmental ideology and political program are important subjects for social science. However, this article mainly focuses on the trajectory of structural globalization (connectedness) as an objective variable feature of the whole world-system.

1Systemness is about processes that are important for the reproduction or change of social institutions and social structures. Some of these processes are always local, but the degree to which they involve nonlocal connections varies over time. Studies of trade networks in world history show a long-term cyclical trend in which relatively long-distance networks rise and fall, periodically increasing their spatial scale in upsweeps to larger levels and then oscillating again until the next upsweep. The downswings are periods of trade deglobalization. This paper compares the current period of plateauing and possible deglobalization with earlier plateaus and phases of deglobalization that occurred in the 19th and 20th centuries.

2Structural globalization is composed of different kinds of interaction networks that have been studied as different dimensions (

Chase-Dunn 1999;

Gygli et al. 2019). Economic interaction networks can be compared with political, social, communications, intermarriage and migration links. This study will focus on what the KOF project (

KOF Globalization Index n.d.) calls de facto economic globalization (international trade and foreign direct investment). We see the modern global world-system as a single integrated hierarchical structure of connectedness of all the humans on Earth, but this study focuses mainly on the dimension of actual economic connectedness. As world-system analysts, we by no means want to perpetuate the myth that connectedness implies only equal exchange that is producing an increasingly flat global social structure. Connectedness and hierarchy are two important dimensions of global social structure that should both be studied together. Global inequality is a combination of within- and between-country inequalities, a core-semiperiphery-periphery hierarchy and a global class structure that have changed over time (see

Chase-Dunn 1998;

Korzeniewicz and Moran 2012), but in this study, we will mainly focus on changes in the degree of global connectedness.

Cultural globalization tracks the decline in the number of spoken languages and the emergence of intercultural trade languages and standard systems of space and time reckoning, as well as the convergence of local and civilizational cultures toward an emerging global culture (

Meyer 2009).

Immanuel Wallerstein (

2012) analyzed what he called the “geoculture”—those aspects of the emerging global culture that are composed of political ideas and institutions.

Political globalization refers to the evolutionary trajectory of global governance. In the modern system, global governance has mainly been organized around the hegemony of a series of core states that have provided a degree of order for the whole system, but these hegemons have risen and fallen, and so, the system periodically experiences a situation of interimperial rivalry and global warfare in which contenders for hegemony have fought it out for preeminence. The hegemons—the Dutch in the 17th century, the British in the 19th century, and the United States in the 20th century—became successively larger relative to the size of the whole system (

Wallerstein (

1984);

Chase-Dunn et al. (

2011)). The successful hegemons have combined military power with economic power by developing comparative advantages in the production of high-technology commodities and the provision of financial services. The hegemons have also proclaimed universalistic ideologies to legitimate the global order that they have strived to maintain. In addition to global governance by hegemony, since the Napoleonic Wars, a set of international organizations have emerged that supplement the systemic leadership of the hegemons—the Concert of Europe, the League of Nations, and the United Nations. Thus, the rise of international organizations and the increasing relative size of the hegemons have constituted the evolution of global political/military governance. Political deglobalization occurs during periods of interimperial rivalry and nationalistic revival, and indeed, this may be one of the main current drivers of economic deglobalization.

3The quantitative study of long-term economic globalization and deglobalization was begun by

Paul Bairoch (

1996;

Bairoch and Kozul-Wright 1998) and has been taken forward both by economic historians who explicitly study recurrent periods of structural deglobalization (e.g.,

Williamson 1996;

O’Rourke and Williamson 2002;

O’Rourke 2018)

4 and by sociologists (e.g.,

Hirst et al. 2018). Economic globalization also has several different subdimensions that should be compared with one another. In this paper on structural economic deglobalization, we will focus on changes in the globalization of actual trade and foreign investment (what the KOF project calls de facto globalization), but we will also discuss changes in the policies of free trade and protectionism—what KOF calls de jure economic globalization. De jure globalization includes policies that are either intended to increase or decrease international connectedness such as treaties that raise or lower tariffs on trade or regulate international investments. The distinction we are making between structural globalization and the globalization project overlaps with, and is informed by, the KOF distinction between de facto and de jure dimensions of economic globalization (

Gygli et al. 2019).

When we began working on this study in 2018, the idea of deglobalization was still unpopular among both social scientists and in the public discourse. However, developments in the last decade, such as trade wars, geopolitical competition between the United States and China, the rise of populist authoritarian regimes and increasing nationalism, as well as the COVID-19 pandemic, have converted skepticism into a vibrant academic and popular debate.

5 Nevertheless, we want to be careful with the conclusion that the contemporary world-system has entered a new period of deglobalization. What do the trajectories of measures of structural de facto economic globalization tell us?

The waves of global integration that have swept the world in the decades since World War II can be better understood by studying their similarities and differences with the waves of international trade and foreign investment expansion that have occurred in earlier centuries, especially the last half of the 19th century. William I. Robinson’s delineation of a new stage of global capitalism provides important insights about the degree to which a transnational capitalist class (TCC) has been able to shape global governance in recent decades by repurposing national states to pursue the neoliberal program of privatization, etc., and the high level of transnational financial and production organization that has emerged. Robinson’s emphasis on the uniqueness of the recent wave of globalization is partly based on his claim that before the emergence of the stage of global capitalism in the last decades of the 20th century, the world-system was composed of national economies that were largely autonomous from one another with regard to the circulation of capital (

Robinson 2019, p. 55). The world-system perspective has contended that the circuits of capital have been organized as an hierarchical division of labor linking the core with the non-core since the emergence of the Europe-centered world-system 500 years ago. The interpenetrating circuits of capital began to be globalized in the 16th century and there have been waves of increasing globalization and deglobalization of capital since then. Robinson is right to argue that globalization has gone to a new higher level of integration in the recent period, but he does not see that there were earlier waves of integration that were separated by troughs of deglobalization.

6 W. I. Robinson’s (

2023) analysis of the increasingly divergent interests between the TCC and national states in the current period of declining U.S. hegemony and the increasing contradictions between the logic of geopolitics in the interstate system and the logic of capitalist accumulation. Arguably, these developments are consistent with the idea that the system may once again be experiencing a period of deglobalization.

Immanuel Wallerstein insisted that U.S. economic hegemony has been declining since the 1970s. He and

George Modelski (

2005) interpreted the U.S. unilateralism of the Bush administration as a repetition of the “imperial over-reach” of earlier declining hegemons that had attempted to substitute military superiority for economic comparative advantage (

Wallerstein 2003). Many of those who denied the notion of U.S. hegemonic decline during what

Giovanni Arrighi (

1994) called the

belle époque of financialization have now come around to Wallerstein’s position in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2007–2008 and subsequent events. Wallerstein contended that, once the world-system cycles and trends and the game of musical chairs (some limited upward and downward mobility in the core/periphery hierarchy) that is caused by capitalist uneven development are considered, the “new stage of global capitalism” does not seem that different from earlier periods. However, accurate specification of both the similarities and the differences is important, as we shall see when we compare the earlier periods of deglobalization with what may be happening now.

2. Measuring Structural de Facto Economic Globalization and Deglobalization

Again, structural globalization is a characteristic of the global political economy that changes over time. This globalization as connectedness is an increase in the spatial range of economic interactions, or an increase in the number and size of long-distance economic interactions relative to the amount of local or within-country economic interactions. The modern Europe-centered world-system became truly Earth-wide in the first half of the 19th century when it geopolitically engulfed the East Asian system (

Chase-Dunn and Inoue 2023). Changes in the magnitude of economic globalization have been estimated by comparing the ratios of the amount of long-distance economic interaction to the size of the global economy. Most efforts to measure changes in the magnitude of structural globalization have compared estimates of the amount of international interaction to estimates of the size of the whole world economy. Usually, both the whole world economy gets larger and the amount of international interaction increases, but it is the relative rates of these increases that are understood to be estimates of increasing or decreasing globalization. Deglobalization means that the amount of international interaction decreases relative to the size of the whole world economy.

Early studies that measured structural economic globalization over long periods of time were carried out by economic historian

Paul Bairoch (

1996;

Bairoch and Kozul-Wright 1998). It was Bairoch who discovered that structural economic globalization was a cyclical upward trend with intermittent periods of deglobalization, but Bairoch and most of the other scholars who studied long-term globalization employed rather intermittent temporal estimates that made it difficult to see the timing of changes.

7One problem with using international financial statistics for both cross-national quantitative comparisons and for aggregating across nation-states to estimate global characteristics is that it is usually necessary to convert country currencies into a single standard that is comparable across countries. Most economic indicators in national accounts are produced in national currencies. To make these comparable across countries or for purposes of aggregation, they are usually converted into U.S. dollars, but doing this is problematic. From the Bretton Woods agreements in 1944 until 1971, most country currencies were pegged to the U.S. dollar, which was theoretically redeemable in gold from Fort Knox, and these rates were mainly set and maintained by national financial authorities (central banks). Since 1971, when the U.S. abandoned the Bretton Woods exchange rate system, exchange rates for country currencies (so-called FX) have been set by the global currency market.

Depending on what the monetary values are intended to indicate, neither pegged nor currency market exchange rates are ideal for standardizing country currencies into a comparable indicator. If one is interested in comparing the availability of goods and services to populations within countries, the use of currency market exchange rates does not do this well because exchange rates among currencies reflect many other things besides the relative value of goods and services in different countries.

Kravis et al. (

1982) sought to correct this problem and to produce comparable estimates of real gross product by weighting GDP figures using a correction for the prices of a basket of typical consumer goods in each country, so-called purchasing power parity or PPP. These corrections were initially estimated for 1980.

Korzeniewicz et al. (

1998) noted that PPP weights are unrealistic for studies over long periods of time unless the weights are recalculated for the earlier time periods. Angus Maddison developed a method for estimating PPP values back in time, and he produced a widely used set of international financial statistics that have been used for both cross-national comparisons and for aggregating world totals to estimate the magnitudes of characteristics of the whole world political economy (

Maddison 1995).

8Maddison’s (

1995, p. 227) estimates of total world GDP jumped from 1820 to 1870, and then to 1900, 1913, 1929 and then to 1950. These temporal gaps make it difficult to see the finer temporal aspects of changes in the level of trade globalization. It would be desirable to have accurate yearly estimates to see short-term changes and to specify the starts and ends of periods of globalization and deglobalization. Some scholars who want to use monetary quantities to estimate the sizes or the relative economic power of national societies or to estimate global characteristics such global income inequality prefer to use currency market exchange rates (FX) to convert country currency values into U.S dollars because they are more interested in what a government can afford to buy abroad than in the basket of goods purchased by residents within the country. Whichever method is used, it is important to understand how the available datasets have been produced.

One method that avoids having to convert country currencies into a single comparable measure (USDs) is to use ratios of country currency characteristics. The country ratios can be compared or aggregated without having to convert into U.S. dollars because the country currency monetary units cancel out when a ratio is computed. The

Chase-Dunn et al. (

2000) study of trade globalization did this to estimate how the extent of trade globalization had changed from 1820 to 1995. Using statistics in country currencies for national income and for the value of imports from the publications of

Brian R. Mitchell (

1992,

1993,

1995), Chase-Dunn, Kawano and Brewer calculated the yearly ratios of imports to national income, usually understood as a measure of “trade openness”.

9 They showed that the average of national trade openness scores were arithmetically identical with the ratio of total world imports to total world GDP when the openness scores were weighted by the population sizes of the countries.

10 These are the estimates that were used to produce the estimates from 1830 to 1994 in

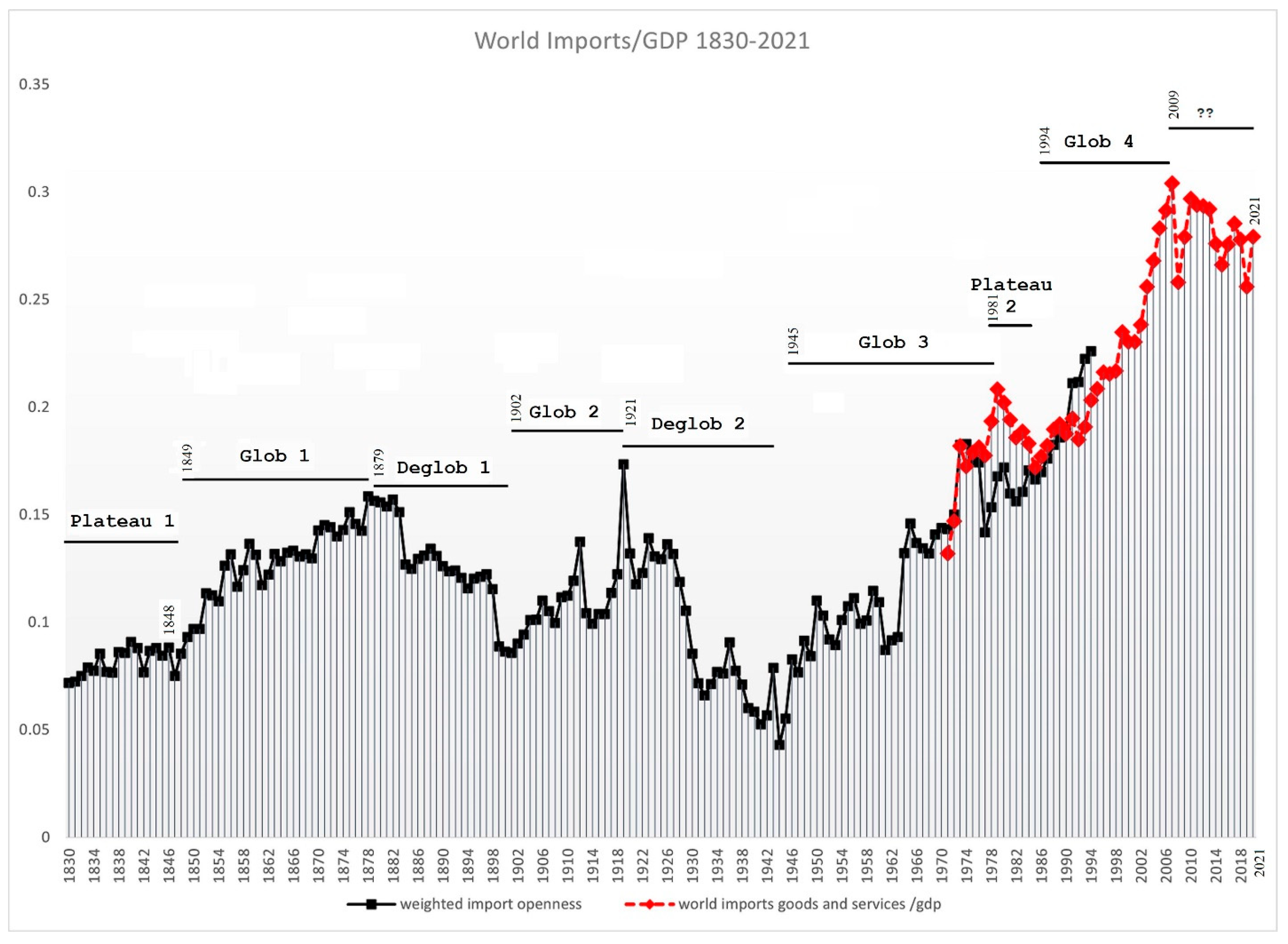

Figure 1 below.

Most of the indicators of structural economic globalization use data on nation-states to calculate global characteristics, but world-system scholars have long argued that the global economy is composed of transnational commodity chains—exchanges among raw material producers, transporters, production processes and final consumers that often cross political boundaries (

Hopkins and Wallerstein 1986;

Bair 2009).

11 The reality of the global economy is that it is a complex network of interactions among all the individuals, households, neighborhoods, organizations, settlements, counties, prefectures, nation-states and transnational/supra-national organizations (

Scholte 2008). Using nation-states as the main unit of data collection occludes the complexity within them and much of the complexity of transnational linkages. Smuggling has always been an important feature of cross-polity economic interaction, and it is not represented in official trade statistics. The insight that transnationalization has gone to a new higher level in the upsweep of globalization since World War II has led researchers to study relations among firms rather than interstate relations, thus revealing global networks in greater complexity (see overview and critique of these studies in

Bair et al. 2021). While this is a valuable refocus of research, the data requirements for this change in the unit of data collection require that only recent decades can be studied, and so the long-term comparisons that are the focus of this article are not possible to do at this level of resolution (links to our excel datasets and to other useful data sources are contained in the

Supplementary Materials to this article which is at

https://irows.ucr.edu/cd/appendices/deglob/deglobapp.pdf, accessed on 31 March 2023).

3. Trade Globalization and Deglobalization

For studying international trade quantities over long periods of time, estimates of the value of imports are more reliable than exports because nation-states long used import tariffs as an important source of revenues and set up customs bureaucracies to keep records of the value of imports so that they could tax them.

Figure 1 shows the trade globalization graph based on ratios of the value of imports to the size of national economies that was published in

Chase-Dunn et al. (

2000). This figure shows the great 19th century wave of global trade integration, a short and volatile wave between 1900 and 1929, and the post-1945 upswing that is often characterized as the “stage of global capitalism”. This indicates that, as Paul Bairoch found, structural trade globalization is both a cycle and a bumpy trend. There were significant periods of deglobalization in the late 19th century and in the first half of the 20th century. In addition, there were “plateaus”—periods in which the level of globalization appeared to be oscillating around a stable level, rather than going up or down.

Figure 1 also includes more recent estimates of import globalization from 1970 to 2021 from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators.

The indicator of imports globalization in

Figure 2 are the same as in

Figure 1, but the time scale has been shortened so that we are better able to see what has happened in the years since 1970.

Figure 2 shows that there was a plateau from 1981 to 1993 and then a bumpy recovery to 2008. Then, there was a precipitous drop in the level of import globalization in 2008 and 2009, then a two-year recovery, but then a slow decline from 2011 to 2016 and then another two-year partial recovery and a two-year decline from 2018 to 2020 and then another recovery in 2021, but it was still not back to the peak of 2008. These recent changes can be seen more clearly in

Figure 3, which zooms in on the period between 2007 and 2021. The World Bank estimate for 2021 is the most recent available at the time of publication—May 2023.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 can be interpreted to support the idea that the world-system is entering another period of structural deglobalization, though this is not certain because there was a 12-year plateau from 1981 to 1993 (Plateau 2) that was followed by a recovery of the upward trend in effect since 1945. The big difference between the current period and Plateau 2 was the large initial decline caused by the financial crisis. This was a 21% decrease from the previous year, the largest reversal in trade globalization since World War II. However, the trajectory since 2008 has also been more volatile than Plateau 2. The COVID-19 pandemic also caused a major contraction in trade globalization in 2019 when trade contracted more than total output (GDP). The recovery of trade in 2021 was larger than the recovery of production, resulting in an upswing in trade globalization nearly back to the 2018 level but still well below earlier peaks.

The question is whether the sharp decrease after the financial meltdown was the beginning of a new reversal or a plateauing of the long upward trend of the past half century or just another temporary hiccup.

Bond (

2018),

Van Bergeijk (

2010,

2018a,

2018b) and

Witt (

2019) have argued that the world-system has already entered another phase of deglobalization (see also

Aiyar and Ilyina (

2023), who call plateauing “slowbalization”).

6. Globalization, Deglobalization and Plateaus since 1830

As shown in

Figure 5 and

Table 1, there was a Plateau 1 (relatively flat) phase from 1830 to 1848, but we do not know when it began because we do not have reliable trade globalization estimates before 1830. Then, there was a trade globalization phase (Glob 1) from 1849 to 1878. The first closely dated period of deglobalization (Deglob 1 in

Figure 5) was from 1879 to 1901. In 1902, another short phase of globalization (Glob 2) began that was interrupted by a sharp decline during World War I and resumed to a peak in 1920. The period from 1921 to 1944 was another phase of deglobalization (Deglob 2) that was then followed by a period of trade globalization from 1945 to 1980 (Glob 3) and then by Plateau 2 from 1981–1993 (see

Figure 3) and then another period of globalization from 1994 to 2008. Then from 2009 to 2021, there has been what looks like the start of another phase of deglobalization or a plateau, but it could be just an adjustment that will be soon followed by another resumption of the long-term upward trend of trade globalization, (hence the ?? in

Figure 5).

6.1. Deglobalization 1 (1879–1901): Financial Panics and the Great Recession

Deglob 1 started with the financial panic of 1873 in Europe and North America. Economic historians call the period from 1873 to 1897 the Long Depression. In the decades of the late 19th century, challengers to British economic hegemony were emerging as other core states industrialized. German unification and the rise of the United States to core status in the 1880s led to a less unicentric structure of economic and military power within the core. In 1884, the British organized the Berlin Conference on Africa, which divided that continent up into European colonies. This was an effort by the British to include Germany in the club of colonial empires as a cooperating ally rather than as a hegemonic challenger. Thus, another wave of European colonialism was contemporaneous with the period of deglobalization that emerged in the late 19th century (see

Figure S5 in the Supplementary Materials).

Paul Bairoch (

1993) noted that the period between 1815 and 1860 was one in which the British opened their home market to foreign goods and advocated that other countries should do the same. This was the heyday of Cobden and Bright and their Anti-Corn Law League.

13 However, it was only between 1860 and 1879 that other countries on the European continent decreased their tariff barriers to imports. The United States adopted greater tariff protection following the northern victory in the U.S. Civil War. After 1879, the European states gradually slipped back toward protectionism, while the British maintained low tariffs until 1914 despite huge political arguments over this policy (

Taylor 1996).

Bairoch (

1993, p. 51) shows that the reintroduction of protectionism did not have a long-term negative affect on the growth of exports for those countries that went protectionist. One of the big differences between Deglob 1, Deglob 2 and the contemporary period is in the configuration of politics of the left and right (

Chase-Dunn and Almeida 2020). In Deglob 1, the labor movement and socialist parties were on the rise, becoming active in politics in many world regions at the beginning of the 20th century. In Britain, this produced the “social imperialism” and protectionism of Joseph Chamberlain in which redistributive polices were combined with an effort to protect jobs through tariffs and to revitalize and further expand the empire with the English working class as a putative partner.

14 According to Bairoch, in the second decade following their reintroduction of protectionism, France, Germany, Italy, Denmark and Switzerland all had higher rates of export growth than in the decade before they went protectionist, and this was also true for Europe as a whole. The United Kingdom, where a liberal trade policy was maintained, had a declining rate of export growth over this same general period. Bairoch did not go so far as to claim that protectionism causes globalization, but he does assert and support the contention that trade liberalization did not cause globalization in the late 19th century.

Our yearly indicator of trade globalization is similarly contradictory with the hypothesis that trade liberalization causes globalization and protectionism causes deglobalization. The first wave of trade globalization began well before the European shift toward free trade, and the downturn in 1879 was preceded by several years by the readoption of protectionist policies by most of the European states. There was an economic recovery, but then, World War I caused trade deglobalization, which was then followed by a recovery after the war that peaked in 1920.

Another round of deglobalization began in 1921, but then there was a recovery during the 1920s followed by the great crash of 1929 that ushered in another wave of protectionism and deglobalization. The trough of Deglob 2 was in 1942 when the world economy reached a point of trade deglobalization well below that of the trough of Deglob 1.

6.2. Deglobalization 2 (1921–1945)

Deglob 2 began in 1921 and was accelerated by the stock market crash of 1929. Its trough was in 1942, and the connectedness of world trade did not recover to the 1921 level until 1974. Other studies that compare the current period of possible deglobalization with earlier periods all focus on the 1930s (Deglob 2) but do not compare with Deglob 1 (

Van Bergeijk 2010,

2018a,

2018b;

O’Rourke 2018). They note that both Deglob 2 and the current period were triggered by a financial collapse. This was also true of Deglob 1, and the disruptions of economic difficulties, the holocaust and World War II caused a great wave of immigration by refugees.

Despite the common belief that the economic collapse of the 1930s was caused by protectionism,

Bairoch (

1996) showed that protectionism was not particularly high in the 1920s and the Smoot–Hawley tariff was adopted in the U.S. after the stock market crash of 1929 and after the decline in trade globalization had already begun. The rise of the middle wave occurred during a period in which tariffs were high but not rising or falling, and the rising tariffs of the 1930s occurred after trade globalization had already begun to fall.

The political configuration of movements and parties in the geoculture had evolved considerably since Deglob 1. Now, the global left was ensconced in labor and socialist parties in many states, and communists had taken state power in the Soviet Union in the World Revolution

15 of 1917. The new kid on the block was fascism, a form of virulent and authoritarian nationalism that had been emerging since the turn of the century but that had taken state power in several countries by the time of Deglob 2 (

Chase-Dunn et al. 2019;

Chase-Dunn and Almeida 2020).

6.3. Globalization 3: 1945–1980

The third wave of globalization after World War II began well before the trade liberalization advocated by the now-hegemonic U.S. had been adopted by many countries. The post-World War II recovery was dominated by the U.S. because it was the only core country that had not had its industrial infrastructure mangled by the war. The Bretton Woods conference produced a global monetary agreement in which national currencies were pegged to the fictional price of gold in Fort Knox and the U.S dollar was established as world money. The Cold War with the Soviet Union and communist parties elsewhere provided a justification for U.S. hegemonic leadership in Europe and much of the rest of the world. The U.S. comparative advantage in industrial production and exports funded an expansion of automobile and home ownership, suburbanization, and a shift toward business unionism in the labor movement. The lunch buckets were full for those unionized workers in the primary sector.

The Marshall Plan supported the rebuilding of industrial infrastructure in Europe, and the U.S. lent support to decolonization movements in many of the colonies of other core powers on condition of the establishment of U.S. military bases in these emerging new nations. The final wave of decolonization after World War II and during Glob 3 produced a global polity composed of theoretically sovereign nation states, and the U.S.-supported United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and opposed the efforts of colonial powers to hang on to or reconquer their colonies. Institutions of neocolonialism and clientelism replaced the structure of colonial empires.

6.4. Plateau 2 (1981–1993)

The upsurge of Glob 3 was interrupted in the 1980s by a 12-year hiatus in which trade connectedness stopped increasing. The oil crisis of 1974 caused a one-year downturn in trade globalization, but then the upward trend continued until 1980, and in the 1980s, there was a debt crisis in Latin America in which countries that had borrowed heavily for development projects were not able to keep up their payments. The trajectory of investment globalization shown in

Figure 4 was flat until 1990 but then began an upsweep until 1995; it had a short downturn and then a steep rise that began in 1992.

6.5. Globalization 4 (1994–2008)

The greater trade openness of the non-core countries subjected to International Monetary Fund structural adjustment that began in the 1980s did not show up in the trade globalization trajectory until 1994. The opening of the Chinese economy to foreign investment and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989 radically expanded the size of the global labor market and were among the spurs of Glob 4. The countries that grew during the “Asian miracle” period based on export promotion contributed to the rise of trade globalization, and their successes were largely due to their access to the U.S. market, so trade liberalization in the last decades of the 20th century probably had a positive impact on the level of trade globalization. However, the cycles of trade globalization and deglobalization over the long run do not correspond very closely with changes in the degree of international trade liberalization.

Figure 4 shows that investment globalization had two very high peaks in 2000 and 2007, which undoubtedly were other spurs of Glob 4. This was the heyday of the neoliberal globalization project in which communications and computational technologies were used to expand financial services and to move manufacturing to countries with lower labor costs.

7. The Period since 2009

Most remember the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers on 15 September 2008 as the trigger of the financial collapse, but signs of trouble were emerging at least since 2006 when a housing bubble arose in both the United States and China. In 2007, stock prices were volatile and a high delinquency rate on sub-prime mortgages made investors and financial regulators nervous. The crisis was most severe in the U.S. and in Iceland, where the three biggest banks collapsed, and the prime minister was convicted of misconduct in office. China helped the recovery of the global economy by creating credit and investing in infrastructure and increasing demand for raw materials and other goods that helped the crisis-ridden countries of both the Global North and the Global South recover. The boom in mineral and agricultural exports and sentiments against the structural adjustment programs imposed by the International Monetary Fund facilitated the rise of left populist regimes in most Latin American countries (

Rodrik 2018).

Rising Chinese investments in Mexico, especially in Nuevo Leon, relatively close to the U.S., are examples of “nearshoring” as Chinese firms try to keep access to the U.S. market and avoid the rising costs of transoceanic shipping (

Goodman 2023). This restructuring of supply chains can be seen as a type of partial deglobalization in which supply chains are getting geographically shorter but still involve transportation across international borders.

Kevin H. O’Rourke’s (

2018) comparison of the similarities and differences between the current period since 2008 and the Great Depression of the 1930s (Deglob 2) points out that colonial empires still existed in the 1930s, and he shows that international trade became more segmented during the Great Depression as core states traded with one another less and increased trade with their own colonies (

O’Rourke 2018: Table 1). O’Rourke contends that this is an important difference between Deglob 2 and the current period, but it is also possible that the functional equivalents of colonial empires are reemerging as neo-colonial structures of control between international organizations and core states and “their” bilateral connections with non-core regions. The demonstrations against the World Trade Organization by the Global Justice movement in Seattle in 1999 and Cancún in 2003 caused a retreat from efforts to structure North–South relations through multilateral agencies and an embrace of bilateral trade deals that are somewhat reminiscent of the formal colonial empires that existed during Deglob 2. O’Rourke also shows that the stock markets rebounded much more quickly in 2008 than they did in 1929. The willingness of governments to quickly bail out the banks shows that the regulators do learn from their earlier mistakes.

The contradictions of capitalist neoliberalism, environmental degradation and uneven development have provoked different kinds of anti-globalization populism, rivalry among contending powers, trade wars and movements for mitigating the effects of anthropogenic climate change. The plateauing and possible downturn in trade and investment connectedness since 2008 is occurring in the context of U.S. hegemonic decline and the emergence of a more multipolar configuration of economic and political power among states. The combination of greater communications connectivity and greater awareness of North/South inequalities, as well as destabilizing conflicts and climate change, have provoked waves of refugee migrations and political reactions against immigrants.

The constellation of movements and parties in the geoculture is different from what existed in the earlier waves of deglobalization. Some of the old movements are still around but have evolved under different economic and political conditions, and new movements have emerged. The culture of the global left was reconstituted in the World Revolution of 1968 in which students in the New Left criticized the parties and unions of the Old Left for the failures of the World Revolution of 1917. In addition, the rise of the neoliberal globalization project led many progressive observers to conclude that the working class as a progressive force had come to the end of its chain (but see

Karatasli 2022). A new communitarian and anarchistic individualism and participatory forms of democracy supported a critique of all forms of organizational hierarchy and asserted “horizontalism”—the abjuration of any semblance of hierarchy in movement organizations. Global indigenism and a critique of Eurocentrism were central tropes of the Global Justice movement that emerged with the World Social Forum in 2001.

Chase-Dunn and Almeida (

2020) studied the constellation of movements participating in the World Social Forum process and concluded that the climate justice movement is the most likely to emerge as a fulcrum for mobilizing the global left in the coming years. On the right, populist authoritarianism and racial nationalism, similar in some ways to the fascism of the 20th century, emerged as a substantial political force in many countries in reaction to the neoliberal globalization project (

Rodrik 2018;

Chase-Dunn et al. 2019).

Some progressive activists see a period of deglobalization as a possible opportunity for the Global South to pursue more autonomous policies. In earlier periods of deglobalization in which, especially during world wars, the capacities of core countries to control and exploit the countries of the Global South were interrupted, more autonomous development projects were able to emerge and to make headway. There has always been a tension within the new global left regarding anti-globalization versus the idea of an alternative progressive form of globalization.

Samir Amin (

1990) and

Walden Bello (

2002) are important progressive advocates of deglobalization and delinking of the Global South from the Global North to protect against neo-imperialism and to make possible self-reliant and egalitarian developments. Alter-globalization advocates pursue a more egalitarian world society that is integrated by cooperative and equal interactions with less exploitation and domination. The alter-globalization project has been studied by

Geoffrey Pleyers (

2011) as an “uneasy convergence” of largely horizontalist and independent activist groups and progressive NGOs (see also

Carroll 2016).

8. Formal Network of Analyses of Globalization/Deglobalization

Most quantitative studies of globalization use attributes of nation-states that measure their relations with all other states and construct quantitative indicators of the whole world economy by weighting and averaging these national attributes or by summing up the trade amounts and the national GDPs to compute the global ratios. However, a lot of information is lost in this process regarding the relations among the states. Most of the measures of trade globalization used above sum up the imports of all nation-states to estimate the quantity of global trade and, then divide that by the sum of all the national GDPs to estimate the size of the world economy. However, the matrix of international trade shows which countries a given country trades with and the magnitudes of the exchanges. All that information is lost when a country’s trade is summed up into a single lump of imports. The method of formal social network analysis in social science has been developed to study quantitative characteristics of whole networks and network characteristics of the nodes of which networks are composed and to visualize networks.

16Johan Galtung’s (

1971) article, “A structural theory of imperialism”, noted that the “center” countries trade with one another more densely than “periphery” countries do.

Jisoo Kim (

2020) used the UCINet program and International Monetary Fund Balance of Trade Statistics on merchandise trade from 2005–2019 to calculate changes in network density and degree centrality for the global network of nation-states and for the network of 20 core states.

17 Network density is the ratio of the number of actual connections among a set of nodes to the number of possible connections. The possible connections are the square of the number of nodes. Kim counted connections as existing whenever there was a non-zero amount of trade between nodes, but he also used the distribution of trade magnitudes in the matrix to count only stronger links—those above the mean and those that are one standard deviation above the mean amount of trade among countries. In calculating density and other network measures, it is important to use a constant set of nodes (countries) over time because, if one allows the set of nodes to change, it impossible to know whether apparent changes in the network characteristics were due to the real changes in the structure of the network or to changes in the set of nodes that have been included (trade globalization for constant cases are shown in

Figure S3 in the Supplementary Materials). Kim found that increasing the dichotomization cutting points to compare all connections versus very strong connections revealed somewhat different trajectories of density. He also found that network trade density trended upward over the period studied but that there were recent declines like what were reported above in

Figure 1 of this article (see Figures 3–5 in Kim’s article). Regarding changes in the density of the 20 core states that Kim studied, he found that the cutting points matter and there was an overall downward trend in density for trade links greater than the mean and greater than one standard deviation above the mean (Figures 6 and 7 in Kim’s article).

There are several rather different ways to measure network centrality, which is an effort quantify the degree to which a network structure is centralized (like a star in which a central node is the single link that connects all the other nodes) or decentralized, in which all the nodes are connected directly to all the other nodes. Kim used Freeman’s degree centrality measure for the core countries and found that the core network was not highly centralized, and there was not much change in the centralization of the core network over the period he studied.

Jeffrey Kentor and Robert Clark (

Kentor and Clark 2023) also used formal network analysis to study density and centrality in the global matrix of foreign direct investment (FDI) stocks

18 in 2009 and 2017 using the Coordinated Direct Investment Surveys (CDIS) dataset from the International Monetary Fund.

19 Kentor and Clark studied both direct investment stocks held within each country by nationals abroad (inward position) and the stocks of investments in other countries held by national investors (outward position) in these two years for the group of countries that returned the surveys (N = 92 in 2009 and 116 in 2017) for inward position) and for sets of countries grouped into the World Bank’s level of economic development categories (high-income, upper-middle, lower-middle and low-income). Kentor and Clark found that the total number of FDI ties (both inflows and outflows) for the group of surveyed countries in the dataset declined from 4847 in 2009 to 4339 in 2017 (see their Table 1). They also showed that the number of FDI ties of lower-middle income countries increased from 2009 to 2017, and the number of FDI ties of the low-income countries in the CDIS dataset increased from 198 to 447 (see their Table 1). They lumped inward and outward positions together, but it would be very interesting to know what happened regarding FDI stocks held by nationals (outward position) versus FDI stocks held by non-nationals (inward position) separately. Non-core countries have long been dependent on foreign investment from abroad, but they have probably increased the amounts of investment stocks held by their own nationals in recent decades. The “expanding markets” in the Global South are an important aspect of economic globalization, and it would be useful to know how much foreign investment by investors in low-income countries has increased. Kentor and Clark also found that FDI stocks held by low-income countries that are held in other low-income countries have a more positive effect on national economic growth than do capital stocks held in more developed countries.

9. Causes of Globalization and Deglobalization

How can we explain the trajectory of trade globalization and deglobalization? For globalization, there are two things that need to be explained: the trend and the cycles. For the trend, the falling costs of transportation and communications must be a main driving force of the upsurges of globalization, but these declining costs of long-distance transport and communications are facilitating background factors that cannot explain the periods of deglobalization because costs did not usually radically increase when globalization declined.

To explain cycles, we must find causes that are themselves cyclical. How have the cycles of globalization and deglobalization corresponded with other known cycles in the global political economy? Can we assume that the causes of upswings are the same as the causes of downswings, except in reverse? That would simplify things, but the example of transportation and communications costs just mentioned implies that things may not be so simple.

How do the ups and downs of economic globalization correspond temporally with other known cycles? Causality should be revealed in the temporal relationships among variables. The contenders here are business cycles (increases and decreases of the rates of economic growth and trade (the Kuznets cycle and the Kondratieff wave), profit squeezes, waves of colonization and of decolonization, the rise and fall of hegemonic core powers (the hegemonic sequence)

20, failures of global governance caused by weakened international institutions, rise of authoritarian regimes, waves of immigration, anti-immigrant movements, uneven development, the war wave and the incidence of world wars, the debt cycle and changes in the level of trade protectionism, changes in the terms of trade and the prices of raw materials produced in the Global South and demographic shifts in age distributions and growth rates.

The hegemonic sequence has been quantitatively measured in terms of naval and air power by George Modelski and William R. Thompson (

Modelski and Thompson 1988). They examined the proportion of intercontinental power capability that was controlled by the most powerful country. In the period we are studying, they found the rise and decline of Britain in the 19th century and the rise of the United States in the 20th century. The world-system perspective has emphasized the importance of economic power in the hegemonic sequence. These two approaches have influenced each other, and

Modelski and Thompson (

1994) included economic power as an important part of their conceptualization and measurement of “global leadership”.

Giovanni Arrighi (

1994) also recognized the importance of ideology and legitimacy in the successful performance of the hegemonic role.

Regarding the problem at hand, both the first and the third waves of globalization corresponded to the rise and consolidation of hegemonies, the British in the 19th century and the U.S. after World War II. However, the middle wave (Glob 2) from 1902 occurred in a period in which hegemony was being radically contested in World War I. This middle wave was short and wobbly, possibly because of the absence of a hegemon.

The Kuznets business cycle is a 20-year cycle in which economic growth increases for about 10 years and then stagnates for about 10 years. This is too short a period to account for the waves of globalization and deglobalization. The Kondratieff wave is a longer business cycle that varies from 40 to 60 years. This is a closer match to the waves of globalization. The 1929 crash occurred during Deglob 2. Most K-wave studies find a K-wave decline (B-phase) beginning in about 1970. This one is not associated with a period of deglobalization, although as noted above in the discussion of

Figure 2, there was a short plateau from 1981 to 1993, but then, there was a rise to the highest level of globalization known.

World wars do not fit well with the three waves of globalization, nor with the deglobalizations. After the Napoleonic Wars, there were no world wars among core powers in the 19th century. There were three “Great Power Wars” between 1815 and 1914, but none of them were very big (

Levy 1983, pp. 72–73). World War I occurred during the first rise of the middle wave of globalization (Glob2). World War II occurred during the last years of Deglob 2. There is no regular relationship between world wars and the globalization/deglobalization cycles. Both migration waves and anti-immigrant movements occurred during Deglob 1 and Deglob2 and in the period since 2008.

10. Summary of Findings, Conclusions and Further Research

We have contributed to the research literature on deglobalization phases by adding comparisons with the Deglob 1 in the late 19th century.

Table 2 summarizes some of the similarities and differences across the two phases of deglobalization and the current period in which the world-system may have entered another phase of deglobalization or a plateau.

Regarding the question of causation, some of the similarities across all three periods, such as trade protectionism, have been disputed as causes (see discussion of Bairoch above). Contemporaneity does not prove causation. Of the 12 systemic characteristics listed in

Table 2, seven were present in both previous deglobalization phases and have been present in the period since 2008. These are hegemonic decline and rising challengers, rising nationalism, a financial crisis trigger, economic slowdown, rising protectionism, heightened competition among core states and firms, rising migration and anti-immigrant movements. The five systemic characteristics that were present for some, but not all, of the phases are world wars, colonial expansion, rising decolonization and rising authoritarianism. Of course, a given kind of historical outcome may have different causes, so consistency or inconsistency does not rule out a systemic condition as a possible cause. For example, as discussed above, formal colonial empires were abolished in the post-World War II global order, but functional equivalents of colonial relationships continued to exist (foreign investment, clientelism, military base agreements, etc.), and it may be that the most recent phase since 2008 has been accompanied by a resegmentation of the economic relationships between core states and sets of non-core regions that is structurally similar to the former colonial empires.

21The world-system may be entering another phase of deglobalization, although a partial recovery of the upward trend in connectedness occurred in 2021, the most recent year for which we have World Bank estimates that allow us to calculate global economic connectedness. The upswing of 2021 was probably a consequence of the reopening of economic activity after the shutdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic (

Abdal and Ferreira 2021). The main causes of deglobalization are probably primarily tied to the contradictions of global capitalism and an emerging crisis of global governance as the U.S. economic hegemony continues to decline. Increasing competition among core states and emerging semiperipheral challengers seems unlikely to be reversed soon, and the remaining U.S. military unipolarity may be unsustainable in the absence of a new round of U.S. economic hegemony, despite the efforts of a section of the U.S. leadership to try to base hegemony on financial sanctions and leadership against the rise of authoritarian regimes.

Regarding the relationship between hegemony and globalization, an anonymous reviewer of an earlier version of this article said:

I also wonder if Arrighi’s distinction between signal and terminal crisis can help explain deglobalization periods and solve the middle wave of globalization problem. After all “Deglob1” seems to have occurred during the signal crisis of the British world-hegemony (1873/96) and “Deglob2” during the terminal crisis of the interwar period. Likewise, “Plateau2” seems to have occurred during the signal crisis of the U.S. in the 1973/80, and the current moment can be seen as the terminal crisis of U.S. hegemony. The middle waves of globalization seem to be linked to financial globalization periods that occur in between signal and terminal crisis.

Giovanni Arrighi (

1994,

2006; and

Arrighi and Silver 1999) saw the evolution of the modern world-system as a series of overlapping “systemic cycles of capitalist accumulation” that had been and was being led by hegemonic capitalist states or state coalitions. Arrighi did not conceptualize or measure waves of globalization (connectedness), but the reviewer is right that his idea of signal and terminal crises fits quite well with our periodization of the deglobalization and plateau phases. We see this as further indication that what political scientists have called “hegemonic stability theory” is an important explanation that links geopolitical and economic processes in the modern system.

It is tempting to conclude that the world-system is reentering another phase of deglobalization, but this is by no means yet certain.

Table 1 shows that the earlier deglobalization phases were 22 and 23 years long, and we only have 13 years of estimates since the downturn of 2008. So, the prudent conclusion at this point would be “too soon to tell”. The KOF project to quantify different dimensions of globalization contends that de jure indicators, which quantify policies of economic openness and free trade, should be among the antecedent causes of greater de facto trade and financial connectedness (

Gygli et al. 2019). This might help us predict the future if de jure indicators have gone down (or up) in recent years, but comparison of the KOF trade and financial indicators from 1970 to 2020 shows that the de jure indicators do not seem to account for changes in the direction of de facto indicators. In addition, the KOF de jure indicator for trade globalization goes up a little since 2008 and does not show any decline while the de facto trade indicator plunged in 2008 and again from 2011 to 2016 and from 2018 to 2020. The KOF de jure financial indicator did not go down, but rather plateaued since 2007 with a small rise in 2013. So, the KOF measures do not shed light on the nature of the period since 2008 or on what is likely to happen in the next few years. Average world tariff rates declined from 1994 to 2019. When the Trump administration in the United States raised tariff rates in trade with China most countries did not follow suit and the U.S. reduced its tariff rate with China after Trump left the presidency (

World Bank 2023, TM.TAX.MRCH.WM.AR.ZS;

Macrotrends 2022). So it was not rising tariffs that caused the bumpy trend in trade globalization since 2008.

Will the 2021 recovery of trade connectedness shown in

Figure 3 and in investment connectedness shown in

Figure 4 be followed by a return to the upward trend toward greater connectedness, or will it continue as a plateau, or will it trend downward into a longer phase of deglobalization that started in 2008? This will not be known for sure for at least five years from now.

However, the important similarities between the period since 2008 and earlier periods of deglobalization shown in

Table 2 lead us to conclude that it is very likely that the current period will be one of either deglobalization or another plateau. Recent instability in the global financial system also leans us in that direction.

If, indeed, we are entering another phase of deglobalization, we can expect more and larger wars, more financial debacles, more organized resistance to the remains of U.S. hegemony, greater migration pressure from the Global South, more nationalism, less cosmopolitanism, more authoritarian regimes, more local and transnational rebellions and more disruptions caused by global climate change because the organizations and agencies tasked with disaster prevention and mitigation will have less capacity to rise to the occasions. We may be entering a “time of troubles not unlike the first half of the 20th century.

22In the meantime, researchers should further develop and test hypotheses about the causes and consequences of earlier phases of deglobalization and should study the causes and consequences of trade oscillations for sociocultural evolution by comparing the modern world-system with earlier regional world-systems. We plan to develop a typology of different structural types of globalization and deglobalization and operationalize these types. Is the international network of trade and investment becoming more segmented into a neo-colonial structure in which some or most core states are increasing their ties with some non-core states and decreasing them with others, producing a functional equivalent of the colonial empires that existed in both earlier phases of deglobalization? This question can be answered by studying recent changes in the structure of the international networks of trade and investment. Have transnational commodity chains and transnational production networks among firms continued to become more fragmented by increased sourcing of inputs from concentrated non-core trading partners? If so, this would add support to the hypothesis that the whole system is plateauing or deglobalizing. We plan to use formal network analysis to study density and centrality with constant cases and to compare foreign direct investment with the portfolio investment network data produced by the Coordinated Portfolio Investment Survey (CPIS) dataset from the International Monetary Fund.

23 We also intend to compare quantitative measures of globalization/deglobalization with quantitative estimates of changes in global inequalities in our future studies of deglobalization.