Violence against Women: Attachment, Psychopathology, and Beliefs in Intimate Partner Violence

Abstract

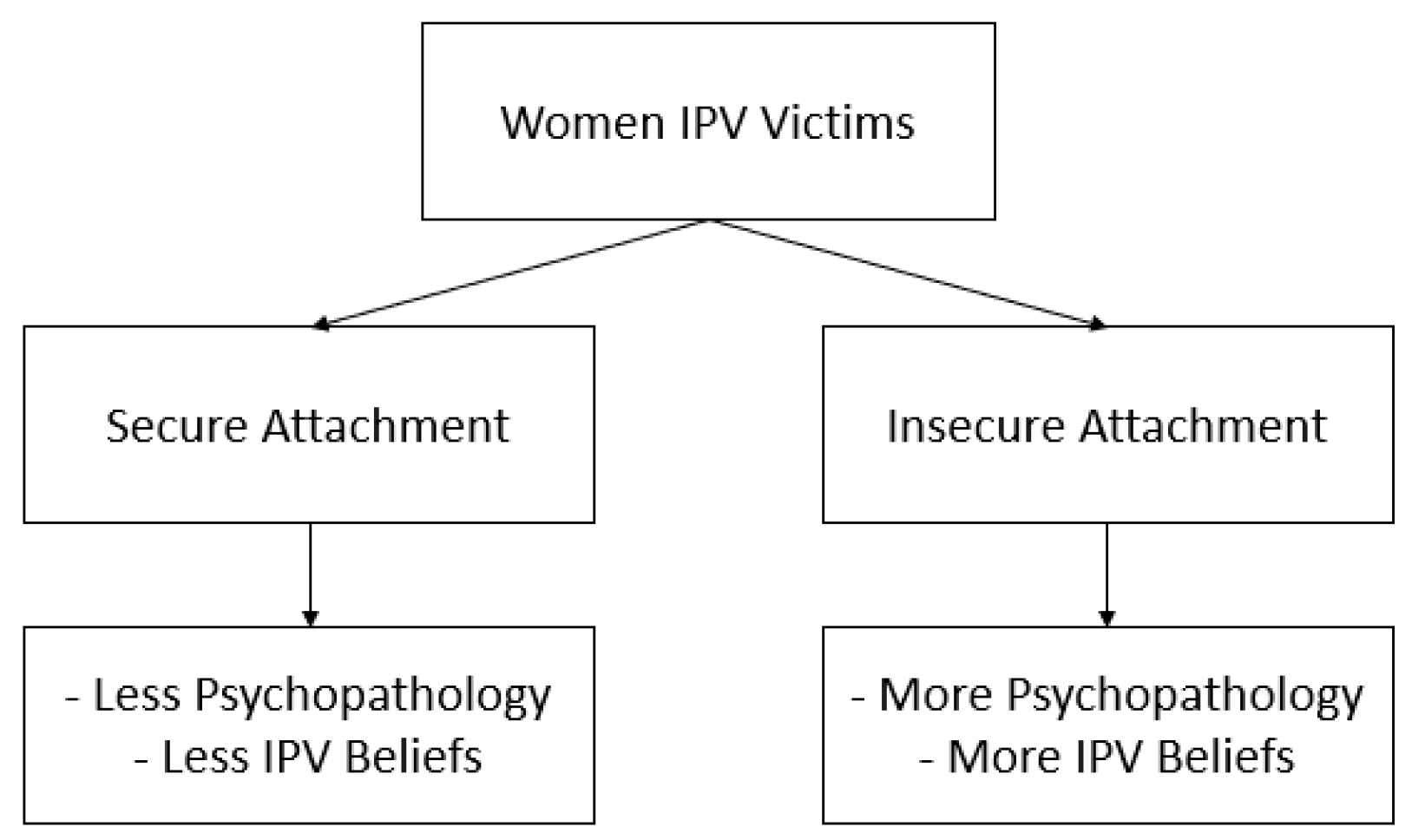

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alkan, Ömer, and Hasan Hüseyin Tekmanlı. 2021. Determination of the factors affecting sexual violence against women in Turkey: A population-based analysis. BMC Women’s Health 21: 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, Colleen J., Kim Bartholomew, Ofra Mayseless, and Donald G Dutton. 2008. Love as a battlefield: Attachment and relationship dynamics in couples identified for male partner violence. Journal of Family Issues 29: 125–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, Iris, Ana Ramalho, Maria Belmira Fernandes, and Renata Guarda Guarda. 2019. Adult attachment as a risk factor for intimate partner violence. Annals of Medicine 51: 187–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Almeida, Iris, and Cristina Soeiro. 2010. Avaliação de risco de violência conjugal: Versão para polícias (SARA: PV) [Risk factor analysis of spousal assault: Using the brief version of the Spousal Assault Risk Assessment-Portuguese version]. Análise Psicológica 28: 179–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaro, Nicole, and Todd K. Shackelford. 2019. Environmental unpredictability in childhood is associated with anxious romantic attachment and intimate partner violence perpetration. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 34: 240–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbaro, Nicole, Yael Sela, Mohammad Atari, Todd K. Shackelford, and Virgil Zeigler-Hill. 2019. Romantic attachment and mate retention behaviour: The mediating role of the perceived risk of partner infidelity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 36: 940–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, Kim. 1990. Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 7: 147–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bartholomew, Kim, and Leonard M. Horowitz. 1991. Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 61: 226–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonache, Helena, Rosaura Gonzalez-Mendez, and Barbara Krahé. 2019. Adult attachment styles, destructive conflict resolution, and the experience of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 34: 287–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bookwala, Jamila, and Bozena Zdaniuk. 1998. Adult attachment styles and aggressive behavior within dating relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 15: 175–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, Kelly A., Catherine L. Clark, and Phillip R. Shaver. 1998. Self-report measurement of adult romantic attachment: An integrative overview. In Attachment Theory and Close Relationships. Edited by Jeffry A. Simpson and William S. Rholes. New York: Guilford, pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan, Kelly, and Philip Shaver. 1995. Dimensions of adult attachment, affect regulation, and romantic relationship functioning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 21: 267–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavarro, Maria Cristina. 1999. Inventário de Sintomas Psicopatológicos: BSI. In Testes e provas psicológicas em Portugal. Edited by Mário R. Simões, C. Machado, Miguel M. Gonçalves and Leandro S. Almeida. Braga: SHO/APPORT, vol. 2, pp. 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Canavarro, Maria Cristina. 2007. Inventário de Sintomas Psicopatológicos: Uma revisão crítica dos estudos realizados em Portugal. In Avaliação psicológica: Instrumentos validados para a população Portuguesa. Edited by Mário R. Simões, C. Machado, Miguel M. Gonçalves and Leandro S. Almeida. Coimbra: Quarteto Editora, vol. 3, pp. 305–31. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, Bonnie E., and Alissa P. Worden. 2005. Attitudes and beliefs about domestic violence: Results of a public opinion survey: I. definitions of domestic violence, criminal domestic violence, and prevalence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 20: 1197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnelley, Katherine B., Lorna J. Otway, and Angela C. Rowe. 2016. The effects of attachment priming on depressed and anxious mood. Clinical Psychological Science 4: 433–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copp, Jennifer E., Peggy C. Giordano, Monica A. Longmore, and Wendy D. Manning. 2019. The development of attitudes toward intimate partner violence: An examination of key correlates among a sample of young adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 34: 1357–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derogatis, Leonard R., and Nick Melisaratos. 1983. The Brief Symptom Inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine 13: 595–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Doumas, Diana M., Christine L. Pearson, Jenna E. Elgin, and Lisa L. McKinley. 2008. Adult attachment as a risk factor for intimate partner violence: The “Misparing” of partners’ attachment styles. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 23: 616–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutton, Donald G., and Katherine R. White. 2012. Attachment insecurity and intimate partner violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior 17: 475–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, Donald G., Keith Saunders, Andrew Starzomski, and Kim Bartholomew. 1994. Intimacy-anger and insecure attachment as precursors of abuse in intimate relationships. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 24: 1367–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, Judith A., and Patrícia Noller. 1990. Attachment style as a predictor of adult romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 58: 281–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godbout, Natacha, Donald G. Dutton, Yavan Lussier, and Séphane Sabourin. 2009. Early exposure to violence, domestic violence, attachment representations, and marital adjustment. Personal Relationships 16: 301–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormley, Barbara. 2005. An adult attachment theoretical perspective of gender symmetry in intimate partner violence. Sex Roles 52: 785–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grych, John H., and Kristen M. Kinsfogel. 2010. Exploring the role of attachment style in the relation between family aggression and abuse in adolescent dating relationships. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 19: 624–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazan, Cindy, and Philip Shaver. 1987. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 52: 511–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, Antonia J. Z., Kim Bartholomew, and Donald Dutton. 1997. He loves me; he loves me not: Attachment and separation resolution of abused women. Journal of Family Violence 12: 169–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, Antonia J. Z., Kim Bartholomew, Shanna J. Trinke, and Marylin J. Kwong. 2005. When loving means hurting: An exploration of attachment and intimate abuse in a community sample. Journal of Family Violence 20: 219–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtzworth-Munroe, Amy, Natalie Smutzer, and Elizabeth Sandin. 1997. A brief review of the research on husband violence: Part II. The psychological effects of husband violence on battered women and their children. Aggression and Violent Behavior 2: 179–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koral, Ayse I., and Monika Kovacs. 2022. The role of anxious attachment in the continuation of abusive relationships: The potential for strengthening a secure attachment schema as a tool of empowerment. Acta Psychologica 225: 103537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuijpers, Karlijn F., Leontien M. van der Knaap, and Frans Willem Winkel. 2012. Risk of revictimization of intimate partner violence: The role of attachment, anger and violent behavior of the victim. Journal of Family Violence 27: 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Machado, Carla, Marlene Matos, and Miguel M. Gonçalves. 2007. Manual da escala de crenças sobre a violência conjugal (ECVC) e do inventário de violência conjugal (IVC.) [Manual: Scale of Beliefs about Marital Violence and the Marital Violence Inventory]. Braga: Psiquilíbrios Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik, James R., Etiony Aldarondo, Steven Gilbert-Gokhale, and Erika Shore. 2005. The role of insecure attachment and gender role stress in predicting controlling behaviors in men who batter. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 20: 617–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McClure, Margaret M., and Megan Parmenter. 2020. Childhood trauma, trait anxiety, and anxious attachment as predictors of intimate partner violence in college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 35: 6067–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikulincer, Mario, and Philip R. Shaver. 2012. An attachment perspective on psychopathology. World Psychiatry 11: 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, João M., Wolfgang Lind, Maria João Santos, Ana Ribeiro Moreira, Mário Jorge Gomes, João Justo, Ana Paula Oliveira, Luís André Filipe, and Mário Faustino. 2006. “Experiências em Relações Próximas”, um questionário de avaliação das dimensões básicas dos estilos de vinculação nos adultos: Tradução e validação para a população portuguesa. Laboratório de Psicologia 4: 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, Ana Cristina, and Iris Almeida. 2020. Beliefs about intimate partner violence: Gender and generation effects. In Psychology and Law: Research for Practice, Sciendo. Warsaw: Sciendo, pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørke, Elisabeth C., Stal Bjorkly, Mariana Dufort, and Solveig K. B. Vatnar. 2021. Attachment characteristics among women victimized in no, one, and multiple IPV relationships: A case-control study. Violence against Women 27: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pianta, Robert C., Byron Egeland, and Emma K. Adam. 1996. Adult attachment classification and self-reported psychiatric symptomatology as assessed by the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory—2. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64: 273–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponti, Lucia, and Franca Tani. 2019. Attachment bonds as risk factors of intimate partner violence. Journal of Child and Family Studies 28: 1425–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rholes, W. Steven, Jeffry A. Simpson, and Grich J. Stevens. 1998. Attachment orientations, social support, and conflict resolution in close relationships. In Attachment Theory and Close Relationships. Edited by Jeffry A. Simpson and W. Steven Rholes. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 166–88. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, Nigel, and Patricia Noller. 1998. The associations between adult attachment and couple violence: The role of communication patterns and relationship satisfaction. In Attachment theory and close relationships. Edited by Jeffry A. Simpson and W. Steven Rholes. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 317–51. [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg, David A., Christine E. Valdez, Jessica L. Engle, and Ekta Menghrajani. 2019. Attachment anxiety as a risk factor for subsequent intimate partner violence victimization: A 6-month prospective study among college women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 34: 1410–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Rogina L., and James V. Cordova. 2002. The influence of adult attachment styles on the association between marital adjustment and depressive symptoms. Journal of Family Psychology 16: 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaver, Philip, and Mario Mikulincer. 2004. What do self-report attachment measures assess? In Adult Attachment: Theory, Research and Clinical Implications. Edited by Jeffry A. Simpson and W. Steven Rholes. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 17–54. [Google Scholar]

- Shurman, Lauren A., and Christina M. Rodriguez. 2006. Cognitive-affective predictors of women’s readiness to end domestic violence relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 21: 1417–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Silva, Alexandra, Simão Ferreira, Élia Silva Pinto, Susana Aguiar Rocha, and Nuno Barbosa-Rocha. 2023. The relationship between childhood abuse and adult attachment styles: The mediator role of sensory over-responsivity. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Linda Sapanski, and Carla Smith Stover. 2016. The moderating role of attachment on the relationship between history of trauma and intimate partner violence victimization. Violence Against Women 22: 745–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soeiro, Cristina, Rita Ribeiro, Iris Almeida, Rosa Saavedra, Sónia Caridade, Ana Oliveira, and Manuela Santos. 2023. Violence against women during the COVID-10 pandemic: From children to the elderly. Social Sciences 12: 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women. 2021. Measuring the Shadow Pandemic: Violence against Women during COVID-19. UN Women. Available online: https://data.unwomen.org/publications/vaw-rga (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- United Nations. 1993. Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/documents/atrocity-crimes/Doc.21_declaration%20elimination%20vaw.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- United Nations. 2023. Gender Equality. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/gender-equality/#:~:text=Globally%2C%2026%20per%20cent%20of%20ever-partnered%20women%20aged,has%20experienced%20some%20form%20of%20violence%20since%20COVID-19 (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- United Nations Secretary-General. 2018. Remarks on International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women. Available online: https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/speeches/2018-11-19/international-day-for-elimination-of-violence-against-women-remarks (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Velotti, Patrizia, Sara Beomonte Zobel, Guyonne Rogier, and Renata Tambelli. 2018. Exploring relationships: A systematic review on intimate partner violence and attachment. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weston, Rebecca. 2008. Insecure attachment mediates effects of partners’ emotional abuse and violence on women’s relationship quality. Journal of Family Violence 23: 483–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2013. Global and Regional Estimates of Violence against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence. World Health Organization. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/85239/?sequence=1 (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- World Health Organization. 2021a. Violence against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018: Global, Regional and National Prevalence Estimates for Intimate Partner Violence against Women and Global and Regional Prevalence Estimates for Non-Partner Sexual Violence against Women. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240022256 (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- World Health Organization. 2021b. Violence against Women. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women (accessed on 15 April 2023).

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Educational qualifications | ||

| 1st Cycle (1–4th year) | 28 | 17.7 |

| 2nd Cycle (5–6th year) | 24 | 15.2 |

| 3rd Cycle (7–9th grade) | 27 | 17.1 |

| Secondary Education (10–12th grade) | 25 | 15.8 |

| BSc Degree | 26 | 16.5 |

| Master | 14 | 8.9 |

| Professions | ||

| Leaders | 1 | 0.6 |

| Intellectual and scientific professions (e.g., lawyer, nurse, doctor, professor) | 25 | 15.8 |

| Technicians and professionals of intermediate level (e.g., nursing or doctor assistant, fitness instructor) | 13 | 8.2 |

| Administrative staff (e.g., secretary, receptionist) | 12 | 7.6 |

| Service and sellers (e.g., cook, hairdresser, police officer) | 38 | 24.1 |

| Agricultural, fishing and forestry workers (e.g., gardener) | 7 | 4.4 |

| Unemployed | 35 | 22.2 |

| Retired | 10 | 6.3 |

| Students | 13 | 8.3 |

| Avoidance | Anxiety | |

|---|---|---|

| Somatization (BSI) | 0.155 | 0.254 * |

| Obsessive Compulsive (BSI) | 0.136 | 0.265 * |

| Interpersonal Sensitivity (BSI) | 0.044 | 0.452 ** |

| Depression (BSI) | 0.230 | 0.429 ** |

| Anxiety (BSI) | 0.170 | 0.204 |

| Hostility (BSI) | 0.146 | 0.421 ** |

| Phobic Anxiety (BSI) | 0.257 * | 0.072 |

| Paranoid Ideation (BSI) | 0.133 | 0.432 ** |

| Psychoticism (BSI) | 0.174 | 0.328 ** |

| Global Severity Index (BSI–IGS) | 0.277 * | 0.131 |

| Positive Symptom Distress Index (BSI–ISP) | 0.281 * | 0.020 |

| Positive Symptom Total (BSI–TSP) | 0.198 | 0.377 ** |

| Factor 1 (ECVC) | 0.184 | 0.461 ** |

| Factor 2 (ECVC) | 0.236 * | 0.392 ** |

| Factor 3 (ECVC) | 0.245 * | 0.358 ** |

| Factor 4 (ECVC) | 0.284 * | 0.429 ** |

| Total Factor (ECVC) | 0.245 * | 0.442 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almeida, I.; Nobre, C.; Marques, J.; Oliveira, P. Violence against Women: Attachment, Psychopathology, and Beliefs in Intimate Partner Violence. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12060346

Almeida I, Nobre C, Marques J, Oliveira P. Violence against Women: Attachment, Psychopathology, and Beliefs in Intimate Partner Violence. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(6):346. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12060346

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmeida, Iris, Carolina Nobre, Joana Marques, and Patrícia Oliveira. 2023. "Violence against Women: Attachment, Psychopathology, and Beliefs in Intimate Partner Violence" Social Sciences 12, no. 6: 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12060346

APA StyleAlmeida, I., Nobre, C., Marques, J., & Oliveira, P. (2023). Violence against Women: Attachment, Psychopathology, and Beliefs in Intimate Partner Violence. Social Sciences, 12(6), 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12060346