Abstract

Access to maternal healthcare has been a challenge for women of African descent. Similarly, to previous illness outbreaks such as the Ebola and Zika outbreaks, the Coronavirus pandemic effects vary from one demographic group to another. Women, compared to men, are left in a more vulnerable position due to long-existing social inequalities and disparities. Differentiated effects include, amongst others, access to health and healthcare, risk of infection and coping strategies. This study examined the experiences of expectant and new mothers in accessing maternal healthcare services during the COVID-19 pandemic. In-depth interviews were used, and participants were selected from Mmabatho, North-West Province in South Africa. The findings show that women accessing maternal healthcare services have had diverse experiences. Some expectant and new mothers experienced fear, anxiety, and frustration, while some had more positive experiences. The positive experiences included spending more time with their families and newborn babies. Some of the participants were worried because of the fear of being infected with the coronavirus. Furthermore, the unavailability and inadequacy of, as well as limited access to, maternal healthcare services during the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected some of the women in the study. This study recommends that public and private sectors responsible for providing maternal healthcare should have emergency preparedness measures in place to ensure the continuous provision of maternal healthcare and cushion women in future disease pandemics.

1. Introduction

Disease outbreaks that occur on a larger scale cause a rapid increase in morbidity and mortality over various geographical areas. This in turn leads to immense social, political, and economic disruptions (Huber et al. 2018; Evans et al. 2015). Disease outbreaks cannot be uniformly felt. Most studies have indicated women are more vulnerable to the conditions that disease outbreaks create (Baker 2010; Mogashoa and Pelser 2014; Moyakhe 2014). This might be attributable to social inequities, biological differences, and restrictive cultural norms, among many factors (Gerberding 2004). Although many interventions and policies incorporate a gendered lens in coming up with mitigations and responses to disease outbreaks, it is usually applied as an afterthought (Asi et al. 2022). In most cases, the different experiences of the vulnerable sections of society are not taken into consideration (Baker 2010; Mogashoa and Pelser 2014; Moyakhe 2014).

In 2017, over 295,000 deaths occurred globally related to pregnancy and delivery complications because of a significant decline in the utilization of services of maternal healthcare. The National Department of Health (2017) mentioned in their report that the private healthcare sector consisted of 80% of healthcare workers serving only 16% of the population, while the public healthcare sector was left understaffed. Pretorius and Klopper (2012) also noted that healthcare facilities in urban communities are designed to cater only to a certain number of people. The number of healthcare workers is not sufficient to service a large number of patients. This imbalance consequently leads to poor service delivery in the healthcare sectors (Pretorius and Klopper 2012). This scenario leads to insufficient services due to the strained budget. If expectant and new mothers cannot access proper services or no services at all, complications during and after pregnancy may occur (Huber et al. 2018).

The Coronavirus pandemic exerted increased pressure on the healthcare systems, with pregnant women encountering the most adverse situations. Furthermore, measures put in place to reduce the transmission of the virus such as lockdowns and maintaining social distance adversely affected the provision of services of maternal health such as antenatal, postnatal, and newborn care (Chitungo et al. 2022; Dzinamarira et al. 2022). Pregnant women faced challenges in accessing public transport to healthcare facilities. In addition, healthcare workers were focusing more on COVID-19 patients compared to other medical conditions (Kc et al. 2020; Pant et al. 2020).

1.1. Research Aim

This paper explored the experiences of women in accessing maternal healthcare services in Mmabatho, North-West Province, South Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The rationale for the selection of Mmabatho was that despite the North-West Province being declared the worst performer on maternal health-related issues, there was insufficient literature concerning the effects of disease outbreaks on maternal healthcare in this context. Furthermore, there is a dearth of literature on understanding the experiences of women accessing maternal healthcare during disease pandemics. Although the results of this study cannot be generalized to other communities, obtaining an emic view of expectant and new mothers will assist in designing comprehensive maternal health interventions and programming that can cushion women against the shocks of disease pandemics in rural contexts.

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. Factors Affecting the Utilization and Provision of Maternal Healthcare

Health and health-related outcomes are not only affected by access and use of healthcare services globally; complex and multidimensional factors can also play a role as social determinants of healthcare. As emphasized by Ataguba et al. (2015), political, economic, social, and environmental factors are linked to the provision of, and access to, quality healthcare services within different healthcare sectors. The different factors affect how women experience and perceive maternal healthcare services. As emphasized by El Shiekh and Kwaak (2015), women’s ability to seek maternal healthcare services is influenced by predisposing and enabling factors and health needs. El Shiekh and Kwaak (2015) emphasize, amongst other things, how lack/low use of maternal healthcare services poses a high risk that often leads to different consequences that can also lead to high maternal mortality, morbidity, and, to some extent, disability.

Various mechanisms of predisposing factors are intertwined and interconnected. El Shiekh and Kwaak (2015) argue that the decision to utilize maternal healthcare is influenced by predisposing factors such as beliefs, attitudes, and values held by expectant and new mothers. Enabling factors include those such as the family and community, and health needs include those such as gender, culture, and tradition. The factors such as beliefs, values and attitudes further influence expectant and new mothers in whether to use formal or informal maternal healthcare services. In addition, women’s access to maternal healthcare services is influenced by their levels of education and knowledge regarding maternal healthcare and health in general. Physical movement and distance to the maternal healthcare facilities also serve as predictors of maternal healthcare. In addition, the responsiveness of healthcare workers plays a major role in influencing mothers to access maternal health services (El Shiekh and Kwaak 2015). Although several scholars have examined the predisposing factors toward maternal healthcare, there is a dearth of literature that seeks to understand the rural contexts during times of crisis.

1.2.2. Fear and Mistrust

The available literature suggests that pregnant women experienced fear and mistrust during their prenatal visits to healthcare facilities (Henwood et al. 2017). They feared contracting the Ebola virus and being stigmatized by other community members and healthcare providers. Miller et al. (2018) advanced the notion that expectant mothers were fearful of contracting the virus because it was alleged that healthcare workers were deliberately injecting and spreading the virus in exchange for money. In addition, patients who were suffering from ailments other than Ebola were placed in Ebola treatment centers, leading to the spread of the virus.

The healthcare system of Liberia has not fully recovered since the Ebola disease outbreak. Most studies did not propose recommendations on how the public and private health sectors could protect women seeking maternal healthcare during the Ebola pandemic (Henwood et al. 2017; Miller et al. 2018; Yerger et al. 2020). The failure of these studies to provide solutions played a role in the prolonged effects of Ebola. In light of the above, this paper seeks to understand the experiences of expectant and new mothers in South African rural communities during the COVID-19 pandemic and provide recommendations for policy and programming preparedness during times of crisis.

1.3. Theoretical Framework

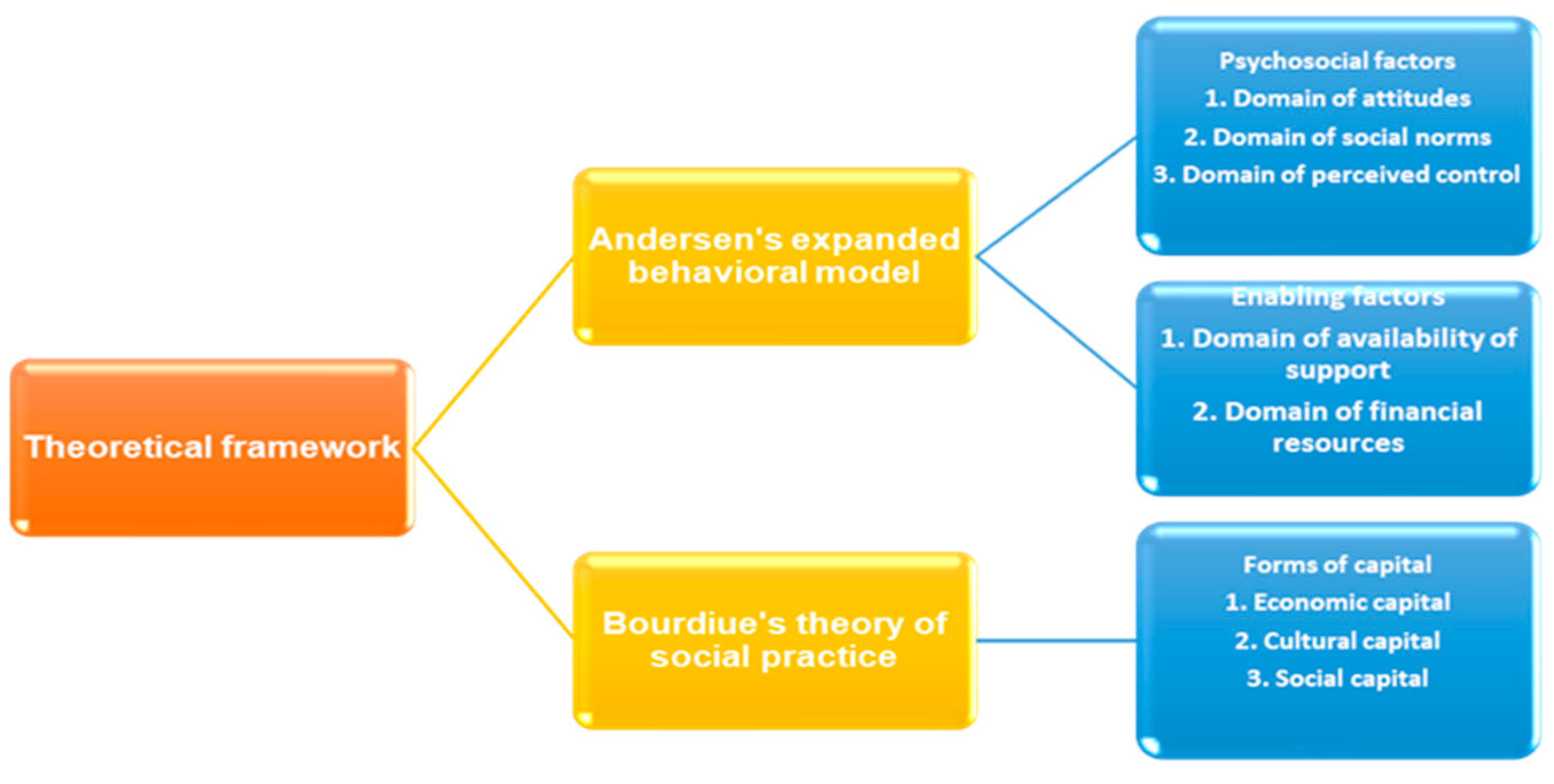

To understand the experiences of pregnant women in accessing maternal healthcare services, this study utilized a combination of two theories, which are Andersen’s expanded behavioral model of health use and Bourdieu’s theory of social practice. Figure 1 below illustrates the model used in this study:

Figure 1.

Major tenets of Andersen’s expanded socio-behavioral model of health services use and Bourdieu’s theory of social practice.

Andersen’s expanded behavioral model of health use is derived from his socio-behavioral model of 1995. The latter sought to explain and predict the provision of healthcare services and the utilization of such services based on people’s traits, the characteristics of the population they belong to, as well as the environment in which they live. Andersen’s expanded behavioral model, on the other hand, explains healthcare services and utilization of services using psychosocial and enabling factors. Both factors consist of different 34 domains, including the domain of attitudes, social norms, perceived control, and enabling factors that consist of the availability of support as well as financial resources. Most theoretical frameworks, including the health belief model and social cognitive theory, view people’s behavior in association with how they seek healthcare as people’s rational choices. This approach provides inadequate focus on the impact of social context on people’s actions (Andersen 1995). It is for this reason that Andersen’s expanded socio-behavioral model of health services use was important for this study.

To illustrate this, a study by Simkhada et al. (2008) found that several studies reviewed showed that women’s decisions to utilize antenatal healthcare services were based on “maternal education, husband’s education, marital status, availability, cost, household income, women’s employment, media exposure and having a history of obstetric complications”. The factors also include cultural beliefs and ideas about pregnancy. The study looked at how the factors mentioned above affected women accessing maternal healthcare services in Mmabatho, North-West in South Africa.

The analytical framework also drew from Bourdieu’s theory of social practice, to understand the influence of factors such as cultural practices, norms, and values on the choices women make regarding usage of healthcare services during and after childbirth. Bourdieu’s theory of social practice was used to analyze the relationship that existed between the women in the study and social structures regarding access to a variety of socio-economic and cultural conditions (Bourdieu 1986; Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992). Field and capital are two important concepts of Practice theory. According to Bourdieu and Wacquant (1992, pp. 22–28), field refers to resources that are available to individuals in society, and they are limited; therefore, individuals are said to be competing for the resources. In the context of access to maternal healthcare, the field can refer to the healthcare services available to mothers before and after childbirth. As the theory is hinged on power dynamics, unequal access to resources is an important factor for consideration.

On the other hand, capital refers to the power or ability that individuals should possess to enable them to gain access to the field. In this study, capital can be economic, social, or cultural resources (Bourdieu 1986; Bourdieu and Wacquant 1992). More specifically, capital is attached to class and other forms of stratification (Bourdieu 1986). In the context of this study, the concept of capital will be used to analyze the role of socioeconomic status, support, education, marital status, and other factors in the practices women espouse through their journey of accessing maternal healthcare. In a study conducted in the United Kingdom, Kandt (2018) uses the two concepts to characterize health inequalities for people with different lifestyles. According to Kandt, lifestyles can be considered as fields where social positioning is reinforced and contested through practices. In other words, people’s healthcare practices affect their position in society. This, in turn, leads to people being categorized into groups based on, among other factors, the capital they possess, such as income, level of education, marital status, and so forth. The two concepts are important; however, they focus on the impact of structure on individuals and may be seen to disregard individual agency. It is for this reason that the theories are used together to understand holistically the decision-making processes of women in accessing maternal healthcare services.

The following section discusses the methodology adopted in this study.

2. Materials and Methods

A qualitative research design was used to understand the experiences of women in accessing maternal healthcare services in Mmabatho during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study used a phenomenological approach to capture the thick deep descriptions of the selected participants. Phenomenology enabled researchers to examine the qualities of people’s experiences through in-depth interviews. The population in this study comprised expectant and new mothers accessing maternal healthcare services in Mmabatho unit 9 and Montshioa town clinics during the COVID-19 pandemic. Purposive and snowball sampling techniques were utilized to select the participants in these two different clinics. Purposive sampling is a non-probability sampling technique in which the researcher specifically chooses participants based on traits or criteria that are pertinent to the study topic or aims. When the target population is small, distinct, or challenging to reach, this sampling technique is frequently used. Because of this, the researchers relied on their judgment to find people who could offer insightful commentary or represent particular viewpoints.

Data collection was stopped at a point of data saturation when themes kept recurring. Polit and Beck (2012) advanced the notion that purposive sampling focuses on characteristics of the population that are aimed at providing answers to research questions. In this case, expectant and new mothers and nurses provided rich data on the experiences of women in accessing maternal healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic. Snowball sampling was not only time efficient but also enabled the researcher to identify other expectant and new mothers. The study included 30 black African women (residing in North-West Province, Mmabatho) in their reproductive years from 20 to 55 years old who gave birth on 5 March 2020 and pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. The justification for this population was that Mmabatho as a study area is made up of 95.5% black Africans that are dependent on public healthcare services (Statistics South Africa 2017). Women who gave birth before 5 March 2020 and the announcement of the National lockdown were excluded from the study. Eighteen women who participated in the study were pregnant, and 13 women had given birth during the data collection phase between August and November 2021. Females younger than 20 years old were excluded from the study for ethical implications. The sample also consisted of 10 qualified midwives with more than 2 years of experience in midwifery. These health workers provided the researchers with rich data on the experiences of women who were accessing maternal healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study utilized in-depth interviews to gain insights into women’s experiences in accessing maternal healthcare services during COVID-19. Since detailed input was needed, the use of structured interviews was ideal. In-depth interviews were conducted telephonically and via online platforms. Audio-visual online platforms allowed the researcher to gain an in-depth insight into women’s experiences in accessing maternal healthcare. The justification for using the online platforms was because of the COVID-19 restrictions, including social distancing to reduce transmission of the virus. The researchers sought informed consent from the participants in the study. Furthermore, permission was sought from the Department of Health, North-West Provincial Office to visit the identified clinics. Ethical clearance was approved by the North-West ethics committee (NWU-00673-21-A7).

The study used Braun and Clarke’s six steps of thematic analysis to bring meaning and order to the mass of data collected. The researchers adopted the following steps in analyzing data.

Step 1: Familiarizing with the data

Data were transcribed by listening to recordings, as the researchers needed to familiarize themselves with the data collected. This step provided the researchers with the foundation for subsequent analysis (Braun and Clarke 2006).

Step 2: Generating initial codes

Preliminary codes were identified, and this allowed the researchers to identify interesting and meaningful patterns and themes. Even though codes are numerous and specific as compared to themes, they provided an indication of the context to be analyzed (Braun and Clarke 2006).

Step 3: Searching for themes

The codes initially extracted from the data collected were grouped in line with the objectives of the study. The researchers were able to identify the relationships and links between codes, themes, and subthemes (Braun and Clarke 2006).

Step 4: Reviewing

This step usually has two phases where the researchers must link the themes and codes initially extracted as well as the overall data set (Braun and Clarke 2006).

Step 5: Defining and naming themes

The researchers then defined and named the different themes that emerged from the data collected. The researchers named the themes that were in line with the objectives of the study (Braun and Clarke 2006).

Step 6: Producing the report

Finally, the researchers transformed the analysis into a report in line with the research questions, themes, and literature reviewed. The report compiled by the researchers was not just a mere description of the themes that emerged, but an analysis supported by empirical evidence that addressed the problem of the study (Braun and Clarke 2006).

3. Results

The following themes were extracted from the study.

3.1. The Experiences of Women in Accessing Maternal Healthcare Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.1.1. The Experiences of Expectant Mothers with Formal Healthcare Providers

The findings of the study showed that due to the increased workload during the COVID-19 pandemic, some nurses were impatient with their clients, which in turn affected the quality of maternal healthcare services and care. This was substantiated by the nine studies conducted in Africa by Mannava et al. (2015), who emphasize that attitudes and behaviors of nurses are an important element in the provision of quality healthcare, as they influence how women experience and perceive maternal healthcare. In Andersen’s expanded model, the domain of attitudes supports the results of the study, as it highlights how the attitudes and behaviors of nurses affect how women experience their access to maternal healthcare. This includes how nurses render maternal healthcare services, and how they treat and communicate with expectant mothers. Most women were asked about their experiences in accessing healthcare services, and most participants reported that they skipped their monthly maternity appointments and medical tests due not only to fear of contracting the virus but also the treatment from nurses. Some interviewees had this to say:

“This has been the most stressful phase of my life and not because of the pregnancy. I remember at one of the clinics, the midwife was so rude to me. She spoke to me as if I was a high school teenager and that has affected my experience in accessing maternal healthcare services. I even changed clinics because of the bad experience. Nurses must change their attitudes”.(Interviewee No. 2, 11 October 2021)

And

“I was deeply affected by the nurses’ attitudes. It was as if they were forced to assist us. The most devastating part is that when such things happen, we do not know where to lodge our grievances”.(Interviewee No. 6, 29 September 2021)

The interview excerpts above reveal that nurses have an impact on the experiences of women accessing maternal healthcare services. In other words, they impact women’s ability and inability to utilize and access maternal healthcare services. As alluded to by Mannava et al. (2015), the attitudes of nurses determine the quality provision of maternal healthcare. The negative experiences reported by the expectant mothers were due to negative interpersonal interactions. This consequently led to some negative experiences for expectant mothers in both clinics.

3.1.2. The Experiences of Expectant Mothers with Informal Healthcare Providers

Findings from the study revealed that some expectant mothers in Mmabatho resorted to informal caregiving not by choice but due to the circumstances they found themselves in. They highlighted that their family members assisted in their prenatal and postnatal journeys. Participants in the study mentioned that they chose informal over professional caregivers because informal caregivers were more empathetic. The maternal health knowledge passed on from generation to generation was passed on with empathy and patience, unlike in clinics. After giving birth, the family continued to ensure that the new mothers were well taken care of to recover. In one of the interviews, an interviewee confirmed that:

“I remember how my mother took care of me after delivery. She prepared salt baths for me until I fully recovered. She took care of my newborn baby and used traditional techniques of taking care of the baby’s umbilical stump. It was a great experience”.(Interviewee No. 1, 24 September 2021)

Some women highlighted that their experiences with informal caregivers were pleasant, as their caregivers were family members with all of the necessary information about pregnancy and delivery.

“I am so blessed that I still have my great-grandmother who was supportive throughout pregnancy and delivery. I used both the health workers from the clinic and my grandmother’s knowledge; if I had to choose, I would choose to stay home and be taken care of by my grandmother. It was such a peaceful experience”.(Interviewee No. 18, 19 October 2021)

And

“I stopped going to the clinic after the second trimester and I was assisted by my grandmother until delivery. I asked her where she accumulated all the knowledge, and she said that is how things were done in the past and this knowledge was also from her grandmother. She assisted me with the birthing process; I only went to the clinic to ensure everything went well. After birth, she still assisted in making sure we were both fine. This is my first smooth pregnancy”.(Interviewee No. 8, 2 October 2021)

The empirical findings of the study highlighted how some new mothers in Mmabatho valued the assistance that they received from informal caregivers during COVID-19. The knowledge passed from generation to generation was valuable, as it provided proper care to expectant mothers. This notion is also supported by Bourdieu’s cultural capital, which demonstrates how learned behaviors from cultural practices influence how women access maternal healthcare services (Zuo et al. 2022). Local knowledge regarding pregnancy and delivery comes in handy when professional healthcare providers cannot provide the necessary information regarding pregnancy and delivery. In this instance, the local knowledge and cultural practices provided an alternative field for new mothers. In other words, the fact that access to healthcare facilities was limited did not stop the mothers from receiving the needed care. This suggests a need to reconsider the idea of field and capital. Going back to the ideas of lifestyles as a way of categorizing people into certain echelons (Kandt 2018), the mothers in the study were more concerned with finding assistance that was empathetic than about appearing to be affluent.

Childbearing is one of the most important events in women’s lives. Therefore, pregnant women must be taken care of, both by their families and by qualified healthcare providers. Despite the sudden overwhelming experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic, there were also drastic changes in how women accessed maternal healthcare services. They led to the discontinuation of antenatal healthcare; consequently, expectant and new mothers were also impacted. Results from this study align with findings from China. The expectant and new mothers benefited from informal caregivers of their family members (Zuo et al. 2022). The family became a cushion for expectant and new mothers in the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.1.3. Preparedness for Birth

Empirical findings confirmed that the birthing experiences of women differed in terms of their birth plans and the clinic/hospital preventive measures. Some women expressed satisfaction in their birthing experiences, while others did not due to various reasons. Some participants reported the unavailability of social support, which negatively affected the experiences of women in Mmabatho. Interviewees confirmed that:

“My birthing experience was not what I initially planned. I had planned a home water birth but unfortunately home births were canceled because of travel restrictions”.(Interviewee No. 9, 2 October 2021)

And

“My husband was unable to join us during labor or even stay with me and our baby after birth. I was sad, not a birthing experience I had hoped for, for my first child”.(Interviewee No. 18, 19 October 2021)

The results above showed that the COVID-19 pandemic affected the birthing plans of women in Mmabatho. This is in line with the findings of a study conducted by Goyal et al. (2020), who advanced the notion that disease outbreaks have had either direct or indirect effects on women accessing maternal healthcare services. Some women also reported that their child delivery experiences were affected by a lack of support from their loved ones. The domain of availability of support in Anderson’s models clearly states that a solid support structure is considered an essential component during the journey of pregnancy and motherhood. It plays a significant role in shaping how women perceive and experience maternal healthcare services.

3.1.4. Experiences with Maternal Healthcare Services

There are several essential services offered within the maternal healthcare sector. These include HIV/AIDS and maternal healthcare counseling, consisting of family planning services as well, and will be discussed in the following section.

HIV/AIDS Counseling

The findings of the study emphasize that women go through several tests during pregnancy. The first test identified was the urine test to confirm pregnancy. Furthermore, expectant mothers had to undergo blood tests to confirm pregnancy. High levels of hormones (human chorionic gonadotropin) can falsely detect that the woman is pregnant (Chilaka and Konje 2021). The blood test is not performed only to confirm the pregnancy but also to test for HIV/AIDS. Interviewees confirm that:

“Pregnancy can be quite tiring, especially the first month. There is just a lot required from you. There are tests, I took a urine test first to confirm the pregnancy and I also took an HIV/AIDS test. This was done to ensure safe delivery”.(Interviewee No.1, 24 September 2021)

And

“I had a face-to-face consultation where the nurse explained the tests I had to undertake. I did a urine test to confirm the pregnancy, the nurse took my blood for other tests. After I undertook an ultrasound test. Honestly, the process is tiring emotionally especially the HIV testing”.(Interviewee No. 2, 11 October 2021)

The findings above also show that the right and necessary information affects how women perceive and experience maternal healthcare services in Mmabatho. Expectant and new mothers need to possess the necessary information on when to visit the healthcare centers for monthly check-ups and the correct medication required for pregnancy. Most participants highlighted that maternal healthcare services have been reported as emotionally draining. The whole process requires emotional support. Tolera et al. (2020) state that various support systems are essential for expectant and new mothers.

Maternal Healthcare Counseling

The findings of the study showed that maternal healthcare counseling is offered in healthcare facilities. Expectant mothers are informed about various methods of family planning to ensure healthy birth spacing practices. This process has been associated with improvement of the mental well-being of expectant mothers. Furthermore, these sessions provide expectant mothers an opportunity to find out about perceived barriers, individually and throughout pregnancy (Ruart et al. 2020). Some women reported having been offered the information about family planning before booking for maternity and after birth, while others did not receive the information after birth due to the overcrowded hospitals and clinics. Furthermore, healthcare workers did not have enough time after delivery due to the high influx of COVID-19 patients. Interviewees confirm that:

“After giving birth I was informed about different family planning methods, their side effects as well as how effective they are. I was allowed to choose one which is suitable for me. All the necessary information about the chosen family planning method was provided”.(Interviewee No. 18, 19 October 2021)

And

“I gave birth during lockdown level five, and I did not receive any maternal healthcare counseling. The hospital was crowded and with only one midwife working, there was just a lot happening and the only thing I wanted was to give birth and go rest at home with my family”.(Interviewee No. 1, 24 September 2021)

As the findings of the study state, some women received the necessary information about family planning services that form part of maternal healthcare counseling, while some women did not due to more healthcare workers attending to the increasing number of COVID-19 patients. The findings of the study support Anderson’s behavioral model, which argues that the availability of knowledge also plays a significant role in shaping women’s experiences when it comes to accessing maternal healthcare services (Travers et al. 2020).

3.1.5. Expectant Mothers Feeling Lonely and Detached

The findings of the study reveal that the reduced support during COVID-19 resulted in some women experiencing loneliness and detachment during pregnancy and delivery due to restricted movement and access to hospitals for accompanying relatives. Expectant mothers could not be accompanied by their families to monthly check-ups as well as during delivery. United Nations Children’s Fund (2021) also noted and identified how only mothers were allowed in the maternity wards in a bid to limit transmission of the COVID-19 virus. The results revealed that some expectant mothers experienced reduced support from health providers due to COVID-19 restrictions. Some interviewees confirmed that:

“Pregnancy and motherhood are exciting and scary, now with COVID-19 added to the list it was just hectic. One had to be cautious all the time. With a large family like mine, it was difficult to explain why they cannot visit to see the child as it was a norm before the COVID-19 pandemic. How do you begin to sanitize your great-uncle before he carries the child? And preventing them from kissing your cute baby. During her vaccine days we had to go early so that when people gather, we are long gone. As a working mom, I must constantly sanitize and dispose of the mask when I get home because my workplace can be a possible spreader or harbor of the virus”.(Interviewee No. 14, 12 October 2021)

And

“During delivery, no one was allowed to visit the hospital as there were risks of spreading the virus, this meant I had to embark on this scary journey alone”.(Interviewee No. 11, 7 October 2021)

And

“I had the loneliest journey of pregnancy. My partner could not even hold my hand during delivery let alone be allowed inside the maternity ward”.(Interviewee No. 2, 11 October 2021)

In combating COVID-19 transmission, the government introduced preventive measures that affected access to maternal healthcare. Some preventive measures included limiting people allowed in the maternity ward to only the mothers giving birth and the midwives. Social distancing also affected in-person visitation and routine access to maternal healthcare services (Andersen 1995). Although this negatively impacted the experiences of expectant mothers, healthcare facilities adopted alternative strategies to minimize complications. Some of the strategies identified by Wanyana et al. (2021) included drive-through consultations and virtual follow-up sessions consisting of antenatal classes that could be transferred easily through different social media platforms (Rozo et al. 2021; Wanyana et al. 2021). This assisted pregnant mothers in accessing information that would assist them in ensuring proper maternal healthcare.

3.1.6. Fear Experienced by Women in Accessing Maternal Healthcare

One of the major findings emanating from the study was the fear of contracting the virus while accessing maternal healthcare services. This is similar to (Freitas-Jesus et al. 2021) and Ombere (2021) advanced, namely that women accessing maternal healthcare services around the world have expressed fear of being exposed to the COVID-19 virus and, as a result, opting for home deliveries rather than hospital/clinic births. In one of the interviews, the interviewees confirm that:

“I was nervous and excited at the same time. I knew giving birth was a blessing, However, I wondered whether the timing was perfect or not. I was also nervous about whether I would contract the virus or not because I had monthly check-ups and that meant getting on and off taxis”.(Interviewee No. 6, 29 September 2021)

And

“I knew going for monthly check-ups was essential and highly recommended, but my worst fear was contracting the COVID-19 virus. I kept thinking about the worst-case scenarios. What if I die from the virus? I have a daughter. That was my biggest fear amongst other things”.(Interviewee No. 11, 7 October 2021)

Results of the study show that women expressed mixed feelings regarding giving birth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some women enjoyed their experiences during the pandemic, as they spent more time with their newborn babies. Some participants mentioned:

“I was so happy that I gave birth to a healthy baby under such circumstances. I was pleased with the treatment that I got from the nurses. It was a tough journey, but I am truly grateful to the nurses that were supportive and helpful throughout the journey”.(Interviewee No. 18, 19 October 2021)

And

“I was so excited about giving birth, this is my first child, and it was a great experience overall. I did not encounter any challenges”.(Interviewee No. 8, 2 October 2021)

As much as some women in Mmabatho had positive experiences under the COVID-19 regulations, some women stopped attending their monthly medical check-ups because of the fear of possibly contracting the virus. The results of the study confirm the previous findings conducted on barriers to maternal healthcare services during the Ebola virus outbreak in three West African countries (Palo et al. 2022; Lawry et al. 2021; Campbell et al. 2022). During the Ebola pandemic, most women accessing maternal healthcare services feared going to healthcare facilities, the reason being the possibility of contracting the virus and possibly dying from it. Similarly, in this study, some women put on hold their monthly check-ups.

4. Discussion

The experiences of women accessing and providing maternal healthcare services play a vital role in guiding healthcare practices during times of crisis (Sweet et al. 2021). Results from this study indicate that women accessing maternal healthcare services have had different experiences. The results from the study show both negative and positive experiences in accessing maternal healthcare services. For instance, cases of nervousness were reported because some women reported to have been worried because of the fear of being infected with the virus. The findings are similar to arguments advanced by Durankuş and Aksu (2020), Orjingene et al. (2020), and the World Health Organization (2020).

Moreover, the results of the study indicated how informal and formal healthcare givers have influenced the experiences of women in accessing maternal healthcare services. Comparing the two types of caregivers, the informal healthcare givers were reported to have been doing an outstanding job in assisting women during pregnancy and delivery. Therefore, more women were satisfied and had pleasant experiences with the informal healthcare givers. Attitudes and behaviors from qualified nurses were reported as one of the factors hindering access to maternal healthcare services during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings of the study also revealed that nurses were being impatient, which also affected how expectant and new mothers experienced maternal healthcare services. This was substantiated by the nine studies conducted in Africa by Mannava et al. (2015). Andersen’s expanded model within the domain of attitudes also supports the results of the study, as it highlights how the attitudes and behaviors of nurses affect how women experience maternal healthcare services throughout their journeys of pregnancy and delivery in Mmabatho. Andersen’s domain of attitudes states that the role of nurses regarding how they render maternal healthcare services, including how they treat and communicate with patients, affects their patients’ experiences of accessing maternal healthcare services. Therefore, it is important that women accessing maternal healthcare services and nurses have healthy relationships to better the experiences of women accessing maternal healthcare services in Mmabatho. The findings also contributed to the theory of social practice by showing that the ideas of capital may change in times of crisis. Cultural practices and reliance on traditional knowledge became vital in accessing maternal healthcare services among women in Mmabatho. The women, as one might look at it, stepped out of the conventional field and tapped into cultural capital instead of competing for limited resources. This suggests that the notions of “field” and “capital” are not universal and there is a need to consider how these may differ in various contexts.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

In conclusion, the study aimed to explore the experiences of women accessing maternal healthcare services in Mmabatho, North-West. The empirical evidence from the study indicated that expecting, and new mothers in Mmabatho experienced maternal healthcare services differently during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is important that women accessing maternal healthcare services and nurses have healthy relationships to better the experiences of women accessing maternal healthcare services in Mmabatho. This was corroborated by Sweet et al. (2021), who stated that the experiences of women accessing maternal healthcare services are important, and the effectiveness of those providing the services plays a vital role in guiding healthcare practices during this challenging phase.

Based on the empirical findings, the study offers the following recommendations.

As there has been an alteration and disruption in the global healthcare system, the public and private sectors must act urgently to ensure that mothers and their children can receive needed care during these times. Special preference should be given to pregnant mothers and those with newborn babies. Apart from this, effective strategies must be put in place to control cases of COVID-19 infection among pregnant women and nursing mothers. This is in line with the World Health Organization 2019, which highlighted that access and utilization of maternal healthcare services should remain at the top of the global agenda daily (World Health Organization 2019).

The private and public healthcare systems should ensure that expectant mothers access required information at any stage of their pregnancy. Pamphlets with all of the relevant information should be placed at clinic reception desks. Pamphlets might contain medical jargon that makes it difficult for some women to understand. Community healthcare workers could also assist in the dissemination of information as traditional information sources when they perform check-ups around the communities. This is in line with the findings of the study conducted by Lu et al. (2022) which highlighted that pregnancy is considered to be the most delicate phase of women’s lives. Therefore, necessary medical care and various types of information are required during this phase. Traditional information sources provide critical and insightful information regarding pregnancy, and this information is often not contextualized in personal situations (Lu et al. 2022).

The private and public healthcare systems should devise a strategy to pre-empt the negative impacts that occurred in previous disease outbreaks such as the COVID-19, Ebola, and Zika virus outbreaks. Challenges such as discontinuation of antenatal classes and other maternal healthcare-related challenges should be addressed thoroughly to be avoided in future disease pandemics. It was discovered in the study that transportation and logistics were major challenges for access to maternal healthcare during the pandemic. To this end, the public and private healthcare systems should create referral pathways and adequate transportation systems that can be utilized for emergencies of this nature. Arrangements should be made to ensure proper transportation networks during times of crisis. This is in line with Aranda et al.’s (2022) study, which highlighted that proper transportation alternatives for expectant mothers should be arranged. Furthermore, in some countries, remote antenatal care has been implemented to mitigate potential coronavirus exposure. This was to assist women struggling to reach healthcare facilities due to lack of transportation (Aranda et al. 2022).

Prenatal counselling should be offered throughout the pregnancy. Prenatal counseling is important because it provides a secure space for prospective mothers to express problems that are not often discussed before and throughout pregnancy. It will also assist expectant women in improving their mental health with supportive care. This is also supported by the findings of the study conducted by Ruart et al. (2020). The authors mention that counseling throughout pregnancy plays an important role in ensuring that expectant mothers are well, both mentally and physically (Ruart et al. 2020).

The private and public health systems should consider promoting the use of indigenous knowledge in maternal healthcare. Indigenous knowledge/informal maternal healthcare, with formal care, can help reduce maternal and child mortality rates. This is in line with the findings of the study conducted by Sarmiento et al. (2021), which indicated that there have been positive effects in utilizing indigenous knowledge and traditional midwives in some parts of the world, including Southern Mexico (Sarmiento et al. 2021). Furthermore, Palo et al. (2022) proposed that licensing informal healthcare workers could ease the continuous demand pressure on health systems globally (Palo et al. 2022). Alderwick et al. (2021) further indicated that collaboration between healthcare systems and other sectors could be a useful route to improving not only maternal healthcare but population health at large. This could improve access to and utilization of healthcare services during times of crisis (Alderwick et al. 2021).

Women who accessed maternity healthcare services expressed anxiety and worry about getting sick. This underlines the necessity for health professionals to address these worries, offer assurance and precise information, and generally help expectant and new mothers to feel less anxious. Healthcare systems globally should give priority to proper communication channels to offer aid in emergencies.

There is a need for training programs to address healthcare provider attitudes, ensuring respectful and patient-centered care. Global efforts should be made to promote a culture of empathy, patience, and respectful communication among healthcare providers. The study identified negative attitudes and behaviors of qualified nurses that impeded access to maternal healthcare services. Instances of nurses acting impatiently and rushing women through deliveries were uncovered by the study, endangering the health and well-being of both mothers and infants. Prioritizing high-quality care is essential, as is ensuring that healthcare professionals have enough time and resources to offer complete maternal healthcare services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z.M., T.C.G. and B.B.; methodology, M.Z.M., T.C.G. and B.B.; software, M.Z.M.; validation, M.Z.M., T.C.G. and B.B.; formal analysis, M.Z.M.; investigation, M.Z.M.; resources, M.Z.M., T.C.G. and B.B.; data curation, M.Z.M.; writing—M.Z.M.; writing—M.Z.M., T.C.G. and B.B.; visualization, M.Z.M., T.C.G. and B.B.; supervision, T.C.G. and B.B.; project administration, M.Z.M.; funding acquisition, M.Z.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the National Research Foundation, grant number 130637.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the North West University, and approved by the Basic and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (BaSSREC) protocol code NWU-00673-21-A7 and approved on the 20th of September 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

Faculty of Humanities Research Committees and National Research Foundation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Alderwick, Hugh, Andrew Hutchings, Adam Briggs, and Nicholas Mays. 2021. The Impacts of Collaboration between Local Health Care and Non-Health Care Organizations and Factors Shaping How They Work: A Systematic Review of Reviews. BMC Public Health 21: 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, Ronald M. 1995. Revisiting the Behavioral Model and Access to Medical Care: Does It Matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda, Zeus, Thierry Binde, Katherine Tashman, Ananya Tadikonda, Bill Mawindo, Daniel Maweu, Emma Jean Boley, Isaac Mphande, Isata Dumbuya, Mariana Montaño, and et al. 2022. Disruptions in Maternal Health Service Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic in 2020: Experiences from 37 Health Facilities in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries. BMJ Global Health 7: e007247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asi, Yara M., Priliantina Bebasari, Emily Hardy, Michelle Lokot, Kristen Meagher, Emilomo Ogbe, Ateeb Ahmad Parray, Vandana Sharma, Claire J. Standley, and Luissa Vahedi. 2022. Assessing Gender Responsiveness of COVID-19 Response Plans for Populations in Conflict-Affected Humanitarian Emergencies. Conflict and Health 16: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataguba, John Ele-Ojo, Candy Day, and Di McIntyre. 2015. Explaining the Role of the Social Determinants of Health-on-Health Inequality in South Africa. Global Health Action 8: 28865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Peter A. 2010. From Apartheid to Neoliberalism: Health Equity in Post-Apartheid South Africa. International Journal of Health Services 40: 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The Forms of Capital. In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Edited by John G. Richardson. New York: Greenwood Press, pp. 241–58. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Loïc J. D. Wacquant. 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Fiona, Andrew Booth, Christopher Carroll, Andrew Lee, and Clare Relton. 2022. Qualitative Evidence Syntheses of Attitudes and Preferences to Inform Guidelines on Infant Feeding in the Context of Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) Transmission Risk. Edited by Michael R. Holbrook. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 16: e0010080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilaka, Victor N., and Justin C. Konje. 2021. HIV in Pregnancy—An Update. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 256: 484–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitungo, Itai, Tafadzwa Dzinamarira, Nigel Tungwarara, Munashe Chimene, Solomon Mukwenha, Edward Kunonga, Godfrey Musuka, and Grant Murewanhema. 2022. COVID-19 Response in Zimbabwe: The Need for a Paradigm Shift? COVID 2: 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durankuş, Ferit, and Erson Aksu. 2020. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Pregnant Women: A Preliminary Study. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine 35: 205–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzinamarira, Tafadzwa, Grant Murewanhema, Malizgani Mhango, Patrick Gad Iradukunda, Itai Chitungo, Moreblessing Mashora, Pelagia Makanda, James Atwine, Munashe Chimene, Elliot Mbunge, and et al. 2022. COVID-19 Prevalence among Healthcare Workers. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Shiekh, Babker, and Anke van der Kwaak. 2015. Factors Influencing the Utilization of Maternal Health Care Services by Nomads in Sudan. Pastoralism 5: 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, David K., Markus Goldstein, and Anna Popova. 2015. “Health-Care Worker Mortality and the Legacy of the Ebola Epidemic. The Lancet Global Health 3: e439–e440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas-Jesus, Juliana Vasconcellos, Odette Del Risco Sánchez, Larissa Rodrigues, Débora Bicudo Faria-Schützer, Adrielle Amanda Altomani Serapilha, and Fernanda Garanhani Surita. 2021. Stigma, Guilt and Motherhood: Experiences of Pregnant Women with COVID-19 in Brazil. Women and Birth 35: 403–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerberding, Julie L. 2004. Women and Infectious Diseases. Emerging Infectious Diseases 10: 1965–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, Parag, Justin J. Choi, Laura C. Pinheiro, Edward J. Schenck, Ruijun Chen, Assem Jabri, Michael J. Satlin, Thomas R. Campion, Jr., Musarrat Nahid, Joanna B. Ringel, and et al. 2020. Clinical Characteristics of COVID-19 in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine 382: 2372–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henwood, Patricia C., Lisa M. Bebell, Reshma Roshania, Vanessa Wolfman, Michaela Mallow, Anushka Kalyanpur, and Adam C. Levine. 2017. Ebola Virus Disease and Pregnancy: A Retrospective Cohort Study of Patients Managed at 5 Ebola Treatment Units in West Africa. Clinical Infectious Diseases 65: 292–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, Caroline, Lyn Finelli, and Warren Stevens. 2018. The economic and social burden of the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. The Journal of Infectious Diseases 218: S698–S704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandt, J. 2018. Social practice, plural lifestyles and health inequalities in the United Kingdom. Sociology of Health & Illness 40: 1294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kc, Ashish, Rejina Gurung, Mary V. Kinney, Avinash K. Sunny, Md Moinuddin, Omkar Basnet, Prajwal Paudel, Pratiksha Bhattarai, Kalpana Subedi, Mahendra Prasad Shrestha, and et al. 2020. Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic Response on Intrapartum Care, Stillbirth, and Neonatal Mortality Outcomes in Nepal: A Prospective Observational Study. The Lancet Global Health 8: e1273–e1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawry, Lynn Lieberman, Nancy Stroupe Kannappan, Covadonga Canteli, and William Clemmer. 2021. Mixed-Methods Assessment of Health and Mental Health Characteristics and Barriers to Healthcare for Ebola Survivors in Beni, Butembo and Katwa Health Zones of the Democratic Republic of Congo. BMJ Open 11: e050349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Yu, Laura A. Barrett, Rebecca Z. Lin, Muhammad Amith, Cui Tao, and Zhe He. 2022. Understanding Information Needs and Barriers to Accessing Health Information across All Stages of Pregnancy: Systematic Review. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting 5: e32235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannava, Peter, Kelly Durrant, Jane Fisher, Matthew Chersich, and S. Luchters. 2015. Attitudes and Behaviours of Maternal Health Care Providers in Interactions with Clients: A Systematic Review. Globalization and Health 11: 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, Nathan H., Penelope Milsom, Ginger C. Johnson, Juliet Bedford, Aline Simen Kapeu, Abdoulaye Baniré Diallo, Kebir Hassen, Nuzhat Rafique, Kamrul Islam, Robert Camar, and et al. 2018. Community Health Workers during the Ebola Outbreak in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone. Journal of Global Health 8: 020601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogashoa, Monene Grysel, and Gert Petrus Jacobus Pelser. 2014. An analysis of the implementation of the national core standards in public hospitals. Africa Insight 44: 142–57. [Google Scholar]

- Moyakhe, Nolonwabo Patronella. 2014. Quality Healthcare: An Attainable Goal for All South Africans? South African Journal of Bioethics and Law 7: 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orjingene, Obinna, Nsahtime L. Akondeng, Aminata S. Kone-Coulibaly, Temitope Ogojah, and Maria Ganama. 2020. Global Disease Outbreaks and Effects on Maternal, Newborn & Child Health in Global South, a Systematic Review. International Journal of TROPICAL DISEASE & Health 41: 47–58. Available online: https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/portal/resource/pt/sea-209705 (accessed on 15 November 2020).

- Ombere, Stephen Okumu. 2021. Access to Maternal Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Experiences of Indigent Mothers and Health Care Providers in Kilifi County, Kenya. Frontiers in Sociology 6: 613042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palo, Subrata Kumar, Shubhankar Dubey, Sapna Negi, Mili Roopchand Sahay, Kripalini Patel, Swagatika Swain, Bijaya Kumar Mishra, Dinesh Bhuyan, Srikanta Kanungo, Meena Som, and et al. 2022. Effective Interventions to Ensure MCH (Maternal and Child Health) Services during Pandemic Related Health Emergencies (Zika, Ebola, and COVID-19): A Systematic Review. Edited by Md Nuruzzaman Khan. PLoS ONE 17: e0268106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, Smriti, Saugat Koirala, and Madhusudan Subedi. 2020. Access to Maternal Health Services during COVID-19. Europasian Journal of Medical Sciences 2: 48–52. Available online: www.europasianjournals.org/ejms/index.php/ejms/article/view/110 (accessed on 21 January 2021). [CrossRef]

- Polit, Denise F., and Cheryl Tatano Beck. 2012. Nursing Research: Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Pretorius, R., and H.C. Klopper. 2012. Positive Practice Environments in Critical Care Units in South Africa. International Nursing Review 59: 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozo, Nathaly, Diana Valencia, Suzanne M. Newton, Greace Avila, Maritza A. Gonzalez, Christina L. Sancken, Veronica K. Burkel, Sascha R. Ellington, Suzanne M. Gilboa, Carol Y. Rao, and et al. 2021. Severity of Illness by Pregnancy Status among Laboratory-Confirmed SARS-CoV-2 Infections Occurring in Reproductive-Aged Women in Colombia. Pediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology 36: 456–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruart, Shelly, Stéphane Sinnapah, Olivier Hue, Eustase Janky, and Sophie Antoine-Jonville. 2020. Prenatal Counseling throughout Pregnancy: Effects on Physical Activity Level, Perceived Barriers, and Perinatal Health Outcomes: A Quasi-Experimental Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 8887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, Iván, Sergio Paredes-Solís, Anna Dion, Hilah Silver, Emily R. Vargas, Paloma Cruz, Juan Pimentel, Germán Zuluaga, Anne Cockcroft, and Neil Andersson. 2021. Maternal Health and Indigenous Traditional Midwives in Southern Mexico: Contextualisation of a Scoping Review. BMJ Open 11: e054542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkhada, Bibha, Edwin R. van Teijlingen, Maureen Porter, and Padam Simkhada. 2008. Factors Affecting the Utilization of Antenatal Care in Developing Countries: Systematic Review of the Literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing 61: 244–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. 2017. Local Municipality Statistics South Africa. Available online: https://www.statssa.gov.za/?page_id=993&id=mafikeng-municipality (accessed on 30 July 2020).

- Sweet, Linda, Zoe Bradfield, VidankaI Vasilevski, Karen Wynter, Yvonne Hauck, Lesley Kuliukas, Caroline S.E Homer, Rebecca A Szabo, and Alyce N. Wilson. 2021. Becoming a Mother in the ‘New’ Social World in Australia during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Midwifery 98: 102996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Department of Health. 2017. Annual Performance Plan 2018/19–2020/21. The Republic of South Africa. Available online: www.health.gov.za/index.php/2014-03-17-09-09-38/annual-performance-plans?download=4491:ndoh-annual-performance-plan-parliament (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Tolera, Habtamu, Tegegne Gebre-Egziabher, and Helmut Kloos. 2020. Using Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Care Utilization in a Decentralized Program to Examine the Use of Antenatal Care in Rural Western Ethiopia. Edited by Kannan Navaneetham. PLoS ONE 15: e0228282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travers, Jasmine L., Karen B. Hirschman, and Mary D. Naylor. 2020. Adapting Andersen’s Expanded Behavioral Model of Health Services Use to Include Older Adults Receiving Long-Term Services and Supports. BMC Geriatrics 20: 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. 2021. COVID-19: A Threat to Progress against Child Marriage. UNICEF DATA. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/covid (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Wanyana Dan, Rachel Wong, and Dieudonne Hakizimana. 2021. Rapid Assessment on the Utilization of Maternal and Child Health Services during COVID-19 in Rwanda. Public Health Action 11: 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2019. Maternal Health. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/maternal-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- World Health Organization. 2020. Pulse Survey on Continuity of Essential Health Services during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Interim Report, 27 August 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-EHS_continuity-survey-2020.1 (accessed on 9 August 2022).

- Yerger, Piper, Mohamed Jalloh, Cordelia E. M. Coltart, and Carina King. 2020. Barriers to Maternal Health Services during the Ebola Outbreak in Three West African Countries: A Literature Review. BMJ Global Health 5: e002974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, Yan, Bi-Ru Luo, Ling-Ning Wang, Bo-Chao Cheng, and Xiao-Lin Hu. 2022. Exploring Lived Experiences of Informal Caregivers for Pregnant Women Seeking Scheduled Antenatal Care during the COVID-19 Lockdown in China: A Phenomenological Study. Midwifery 109: 103316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).