Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought increased attention to the existing gender asymmetries in academia, which have been extensively studied in the literature. Using the analytical lens of “gendered academic citizenship”, this paper takes a micropolitical perspective to examine how the pandemic has impacted the dynamics of academic work, specifically focusing on the often-overlooked aspect of everyday interactions in the work environment. Through qualitative and quantitative analysis of survey data collected from 1750 lecturers and researchers in Portuguese higher education and research institutions, the study uncovers that women, especially those who are younger, single, have specific caregiving responsibilities, and are in the early stages of their careers, were more vulnerable to experiencing “everyday” microaggressions such as silencing, exclusion, belittlement, being ignored, lack of validation, and invisibility compared to men during the pandemic. These findings suggest that, while the marginalization of women in academia is a longstanding issue, the virtual work model has created a platform for the expression of subtle forms of disempowerment and discrimination against women. These dynamics are perpetuated within the micropolitics of organizations, shaping subjective feelings of belonging and circulating differential levels of recognition within academic institutions.

1. Introduction

Gender inequalities in academic professions have been a subject of scholarly work for decades, and their persistence over time has increasingly drawn the attention of transnational organizations, including the European Commission (2016, 2019, 2021). These inequalities manifest in several ways, such as women’s lower salaries compared to men, underrepresentation in decision-making bodies, and patterns of horizontal and vertical segregation that disproportionately concentrate women in lower, less secure, and less prestigious positions in both higher education and R&D institutions (Whittington 2011; Currie 2012; Van der Lee and Ellemers 2015; Johnson 2017; European Commission 2019; UNESCO 2019). The literature teems with metaphors that symbolize the numerous challenges and barriers faced by academic women in their careers. These metaphors paint a compelling picture of scientific institutions as hostile environments, replete with leaky pipelines, glass ceilings, and sticky floors (e.g., Jones and Palmer 2011; Resmini 2016; Brown et al. 2020).

In Portuguese academia, despite the recent portrayal of Portugal as a leader in gender equality in scientific research in Europe based on certain prominent figures (Elsevier 2021), women still face significant disadvantages compared to men in terms of participation, status, and working conditions. The significant participation of women as researchers, Ph.D. candidates, and active authors in the country, approaching parity, and their strong performance in terms of publication metrics contribute to the positive perception of Portugal’s achievements in gender equality. However, noteworthy gender inequalities persist in the national academic labor market. According to the She Figures report by the European Commission (2021), women in Portugal in 2019 were significantly underrepresented in decision-making and leadership positions in research organizations, comprising only 35% of board members. Additionally, they hold only 27.2% of top-ranking positions in the academic hierarchy. Women also face challenges in accessing research funding, as the success rate of men applying for funding is higher than that of women by almost 3 percentage points (2.9 p.p.), the sixth highest of the 28 countries. Moreover, women researchers in Portugal are disproportionately concentrated in precarious employment arrangements, with 11.4% employed in such roles compared to 8% of men. This figure exceeds the European average of 7.6% for women and 5.9% for men in 2019 (European Commission 2021).

The COVID-19 outbreak, and subsequent containment measures, have caused significant disruptions to academic activities, leading to profound transformations in the lives of lecturers and researchers. Since the beginning of the pandemic, there has been particularly intense debate about the gendered nature of the impact of COVID-19 in academia, namely on the scientific productivity of women (Meehan et al. 2021; Krukowski et al. 2021; Shalaby et al. 2021). In an academic context where the number of publications is considered one of the main indicators of performance and a condition for career advancement, the observed decline in women’s research productivity during the pandemic may have profound and lasting negative consequences for their professional trajectories. Much of the early research highlighting such emerging gender inequalities in pandemic academia has tended to link them to factors external to scientific institutions, particularly the intensification of private reproductive labor and care work (Myers et al. 2020; Viglione 2020; Minello et al. 2021; Kasymova et al. 2021), while a smaller body of scholarship has examined internal factors within scientific institutions, particularly the gender inequalities prevalent in the division of academic labor (Ferreira et al. 2021; Górska et al. 2021).

While previous studies have made important contributions, they tended to overlook a crucial dimension of the production of gender asymmetries in higher education and research institutions—the realm of everyday practices and interpersonal relations in the work environment. This paper aims to address this gap in the literature by examining the gendered effects of the pandemic on the dynamics of academic work, with a specific focus on the overlooked dimension of the micropolitics of everyday interactions in the academic work environment under COVID-19. Our main aim is to understand how the pandemic-induced changes in academic work conditions have influenced the everyday experiences and interactions of women academics in higher education and research institutions.

To achieve this, we draw on the concept of “gendered academic citizenship” (Sümer et al. 2020), which focuses on the formal and informal aspects of individuals’ integration in academic institutions or scientific communities, emphasizing how such integration is influenced by gendered power relations. Our analysis specifically focuses on these informal, relational, and experiential aspects of academic citizenship. Informed by a micropolitical perspective, attentive to the “ways in which power is relayed in everyday practices” (Morley 2000, p. 232), we seek to shed some light on how gendered experiences and hierarchies were (re)produced in everyday transactions in academic institutions during the pandemic crisis.

Our analytical focus falls specifically on Portuguese higher education. We collected empirical data through an online survey administered to a sample of 1750 academics, including lecturers and researchers affiliated with higher education and research institutions in Portugal. The survey focused on respondents’ work experiences during the first year of the sanitary crisis, which encompassed three waves of the pandemic and two general lockdowns.

The article is structured as follows. First, we provide a concise review of previous studies that analyzed the differential effects of the pandemic on the lives of academic women and men. Next, we provide a comprehensive presentation of the theoretical-analytical framework used in our study, which is primarily based on the concept of gendered academic citizenship proposed by Sümer et al. (2020). Subsequently, we detail the research methods employed in our study. Finally, we present and discuss the results obtained.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Gendered Impacts of COVID-19 in Academia: Insights from Previous Studies

Several studies focused on the academic context have drawn attention to the fact that the double burden of paid and unpaid work has become even heavier for women during periods of lockdown, given the growing demands of domestic and family care responsibilities (Newcomb 2021; Lopes et al. 2021; França et al. 2023). Women have remained primarily responsible for tasks such as cooking and cleaning, and these activities have been intensified due to the increased occupancy of domestic space during confinement (Aldossari and Chaudhry 2021). Furthermore, the closure of schools and nurseries has led to increased domestic and care workloads for women with dependent children (Yildirim and Eslen-Ziya 2021; Minello et al. 2021; Mazzucchelli et al. 2022).

Amidst the pandemic crisis, women academics were faced not only with the challenge of managing escalating domestic and caregiving responsibilities but also with heightened demands in their professional lives (Meehan et al. 2021; Shalaby et al. 2021; Washburn et al. 2021). This situation was exacerbated by longstanding gendered divisions of labor within academia (Ferreira et al. 2021; Lopes et al. 2021). The rapid shift to remote teaching posed numerous difficulties for lecturers, including an increased workload arising from the need to acquire new skills for online instruction and adapt teaching methods to the virtual format (Augustus 2021). As women are more frequently assigned undervalued academic tasks such as teaching, tutoring, and student supervision (Misra et al. 2012; Weisshaar 2017; Cabero and Epifanio 2021), they disproportionately experienced work overload during lockdowns.

The pandemic-induced context of work intensification and challenges in balancing family demands and professional responsibilities (Burk et al. 2021; Lopes et al. 2021) had a significant impact on the research productivity of women academics. Findings from a virtual survey conducted among lecturers and researchers from various countries reveal that 48% of women reported difficulties in maintaining focus and productivity during the lockdown periods, while only 28% of men experienced similar challenges (Watchorn et al. 2020). Moreover, data reveal a decrease in the number of publication submissions by women during the pandemic crisis, while the numbers for men remained unaffected (Andersen et al. 2020; Vincent-Lamarre et al. 2020) or even showed an increase (Cui et al. 2022). This trend is consistent across disciplinary fields: Shurchkov et al. (2020) found a decrease in working paper submissions by women researchers in the field of economics, and an analysis of 41,858 papers published in the largest virtual repository of preprints in Social Sciences revealed a significant increase in the gender gap during the same period, with women’s productivity decreasing by 13% compared to men (Cui et al. 2022). Andersen et al. (2020), examining a set of medical journals, observed a 19% drop in the number of articles with a woman as the first author compared to the same period in 2019.

Additionally, research suggests that the pandemic’s negative effects on academic productivity were particularly pronounced among women with children, indicating a further penalization of motherhood within academia during the COVID-19 crisis (Lopes et al. 2021; Kasymova et al. 2021; Myers et al. 2020). Findings from a comprehensive survey conducted with faculty across various countries and disciplines revealed that women researchers with children experienced twice the reduction in daily research time compared to men in similar circumstances (Deryugina et al. 2021).

The impacts of the pandemic on the productivity of academics also appear to be influenced by career stage. Analysis of 307,459 submissions across virtual preprints repositories and research report platforms found that the largest decrease in the number of submissions occurred among early-career women (Vincent-Lamarre et al. 2020). Similarly, Cui et al. (2022) found that Assistant Professors experienced greater declines in their academic productivity. Building on a comprehensive review of existing studies, Herman et al. (2021, p. 11) concluded that women researchers and junior researchers disproportionately experienced the greatest difficulties arising from the pandemic.

The adoption of business-oriented management practices and a focus on productivity imperatives (Deem et al. 2008; O’Connor 2014; Acker and Wagner 2019) have led to an increased emphasis on bibliometric indicators in evaluating scientific performance. Publications in reputable scientific journals have become the primary measure of success in the competitive “academic market”, conditioning access to positions, recognition, and funding (Brandser and Sümer 2020). Therefore, the decrease in the number of publications by women during the pandemic may have profound and enduring negative consequences for their professional trajectories, particularly for early-career academics with more precarious employment conditions. This scenario is likely to exacerbate gender inequalities in academia, perpetuate vertical segregation, and to further penalize motherhood.

Despite the valuable insights gained from previous studies, there are still significant gaps in the literature on the gendered effects of COVID-19 on academic work. Prior investigations have overlooked the intricate nature of everyday interactions within scientific institutions and how they are influenced by gender dynamics that operate subtly. As a result, these studies fail to recognize the vital role that everyday practices, relationships, and emotions have played in shaping power dynamics in academia during the pandemic.

To help illuminate these less visible aspects of the functioning of academic institutions under COVID-19, we mobilize the concept of gendered academic citizenship.

2.2. Theoretical Framework: Gendered Academic Citizenship

The theoretical framework of this study is based on the concept of gendered academic citizenship introduced by Sümer et al. (2020). The authors propose the notion of gendered academic citizenship as an analytical lens that allows for the exploration of the formal and informal aspects of individuals’ integration in academic institutions or scientific communities, emphasizing how this process is influenced by gendered power relations.

Drawing on earlier feminist contributions to citizenship studies, Sümer et al. (2020) define gendered academic citizenship as comprising three key components: membership, recognition, and belonging. Membership pertains to the formal contractual relationship between academics and scientific institutions, with a key differentiating element being the permanent or temporary nature of the contracts (Sümer et al. 2020, p. 20). The dimension of “recognition”, in turn, involves the decision-making power that each person has in his or her institution with regard to the possibilities of influencing internal processes and making his or her voice heard at the organizational level. This facet of academic citizenship also includes the “level of respect and acknowledgment academics receive from management, colleagues and students” (Sümer et al. 2020, p. 20). Finally, the “belonging” component of gendered academic citizenship refers to the subjective sense of “being a part”, that is, “the feeling of being ‘at home’ and fitting into a particular institution and to a broader academic community” (Sümer et al. 2020, p. 20). Because of its experiential nature, this dimension cannot be assumed based on the other components of gendered academic citizenship. In this sense, it cannot be stated prior to situated empirical analyses that, for example, a woman Full Professor (i.e., holder of high “membership”) necessarily cultivates a high sense of belonging to her institution. Organizational cultures and departmental micropolitical dynamics permeated by gender hierarchies can generate feelings of exclusion that have a negative impact on the sense of belonging of academics, especially in the case of women.

A significant contribution of this concept is the recognition that academic citizenship extends beyond formal membership and encompasses the “relational and emotional aspects of participation, recognition and belonging” (Sümer et al. 2020, p. 2). This framework emphasizes the role of informal practices in shaping power dynamics within academic settings. It also highlights the importance of understanding how these everyday practices are perceived and experienced by academics, as emphasized by Roseneil et al. (2012) in the concept of “lived citizenship”. In this study, we specifically focus on the components of recognition and belonging within this framework to gain insights into the lived experiences of academic citizenship during the pandemic.

Previous research has extensively shown that issues of power and powerlessness in academia extend beyond numerical representation and formal monolithic management structures. Subtle forms of disempowerment, harassment, and discrimination against women are perpetuated in the micropolitics of organizations through informal elements such as coalitions, influence, denial, gossip, alliances, sarcasm, language, and rumors (Morley 1995). A micropolitical analytical perspective implies a critique of conventional understandings of how power operates in society and organizations. In contrast to a centralized conception of power, which understands it as solely held by individuals in authoritative positions within formal hierarchies, a micropolitical perspective pays attention to the ways in which power permeates social relations at all levels, making everyday interactions an integral part of the diffuse and capillary networks through which it operates (Foucault 1991). This perspective understands that, for it to function, “power must be articulated at the ground level in human practices” (Goldfarb 2008, p. 1818). From this analytical standpoint, small events of everyday life in organizations are understood as carrying political significance, so they need to be interpreted not on the basis of their particularity and immediate context but, rather, in terms of the ways in which they point to issues that extend beyond them—to broader social relations and structural forms of oppression.

Aiston (2011) highlights that much of the discrimination women experience in academia is subtle and intangible, encompassing processes of “internal and external silence/ing” (Aiston and Fo 2021, p. 8). This phenomenon occurs within an organizational culture of higher education, where women are still expected to conform, while an emerging discourse encouraging women to “lean in” holds them “accountable for sexism by focusing on internal rather than external change” (Jackson 2017, p. 8). Earlier research often failed to capture these subterranean conflicts and nuances of social relations (Morley 1999) that have contributed to scientific institutions being characterized as “gendered organizations” (Acker 1992). Recognizing and understanding the contemporary manifestations of prejudice and discrimination against women is crucial for the effective identification and addressing of gender discrimination.

Scholars studying these contemporary forms of prejudice and discrimination draw from various constructs in the literature (Basford et al. 2014). The concept of “everyday sexism” is frequently used to describe the daily experiences of interpersonal discrimination that women face in their lives (Bates 2016; Bourabain 2021). It encompasses women’s everyday struggles with invisibility, microaggressions, and marginalization, which are “considered inconsequential, harmless, and frivolous, not easily observed, often unnoticed and reported” (Das et al. 2023, p. 589). It is the regularity and ordinariness of gendered positioning that comes to constitute what Savigny (2014) termed “cultural sexism”. The construct “cultural sexism” combines the notion that sexism “is an everyday, ordinary, occurrence, combined with the cultural context which gives rise to it, and its cumulative, drip-drip effects that have impacts and outcomes on women, and which may disempower or marginalize their experiences and contributions” (Savigny 2017, p. 6). Underlying this notion is the implication that women face a “chilly climate” within academia. The notion of a “chilly climate” further underscores how seemingly inconsequential, cumulative, routinized practices and discourses can have a significant impact on women. These practices fail to recognize and value women’s contributions, leading to a loss of confidence, marginalization, and a diminished sense of belonging (Hall and Sandler 1982; Prentice 2000). By incorporating the concepts of “everyday sexism” and “cultural sexism”, we bring attention to the pervasive and cumulative nature of gendered positioning, which undermines women’s experiences and contributions, and we shed light on the detrimental effects of a “chilly climate” in academia, where seemingly inconsequential practices erode women’s confidence and sense of belonging.

In our study, we contend that a holistic analysis of the gendered effects of COVID-19 on the lives of academics should encompass an examination of the everyday processes of “stalling, sabotage, manipulation, power bargaining, bullying, harassment, and spite” (Morley 2000, p. 232) that have traditionally helped to perpetuate the position of women as second-class academic citizens. By shedding light on these subtle yet impactful dynamics, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of the gendered experiences of academics during the pandemic beyond issues of pay, promotion, and tenure.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Procedures: Data Collection and Sample

In this article, we present findings based on empirical data collected between March and April 2021 as part of a nationwide study aimed at exploring the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic on academic work. The data were gathered through a web-based survey completed by 1750 lecturers and researchers who were affiliated with Portuguese higher education and R&D institutions during the second semester of the academic year 2019/2020 and the first semester of the 2020/2021 academic year.

To reach potential participants, survey invitations were sent initially to a list of 7883 e-mail addresses of academics obtained from the websites of 14 selected Portuguese higher education institutions, including universities and polytechnics. In a subsequent phase, with the support of the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT), invitations were extended to 3317 lecturers and researchers who had applied for funding under the Call for Scientific Research and Technological Development Projects in March 2020. The response rate of 15.6% achieved in this online survey can be considered reasonable, as indicated by Smith (2008) in the context of online surveys.

Participants were invited to complete the questionnaire electronically through a secure online link using the LimeSurvey platform. The survey was self-administered, meaning that participants independently accessed and provided their responses without direct involvement from researchers. However, contact information of the researchers conducting the study was provided, and participants were encouraged to reach out with any questions or concerns. This proactive approach aimed to ensure participant engagement and address any doubts or inquiries that may have arisen during the survey process while still maintaining participant anonymity and privacy.

The research protocol underwent a thorough review and approval by the Ethics Committee of the Institution that hosted the research, ensuring compliance with ethical guidelines and standards. We strictly adhered to the ethical principles of informed consent, privacy, and confidentiality throughout the research process. An informed consent outlining the purpose and objectives of the study, confidentiality measures, voluntary participation, and the option to withdraw from the study at any time was integrated into the questionnaire protocol, and participants were required to provide their consent as part of the survey process.

A pilot test of the questionnaire was conducted with a small sample of participants to ensure data validity and reliability. This allowed us to identify and address issues and areas of confusion, refining the questionnaire for clarity and understanding. We provided clear and concise instructions to participants, including response format, scoring instructions, and skip patterns. To prevent response bias, we carefully balanced positively and negatively worded items. Additionally, we monitored data collection for missing data, outliers, and patterns of response that could indicate careless responding, ensuring the reliability of the collected data. The pilot test also allowed us to estimate the average duration of the questionnaire, which was approximately 25 min.

3.2. Instruments

The questionnaire used in the study included a brief presentation of its objectives and was composed of both open and closed questions organized into eight thematic sections, totaling 83 questions. The sections covered various aspects of the participants’ profiles and experiences during the pandemic, including (a) socio-demographic and professional characteristics, (b) strategies for adapting to remote work/teaching, (c) opinions on remote teaching and research, (d) institutional practices, (e) effects on academic performance, (f) work–family articulation, and (g) reactions received to their academic work during the pandemic.

In this article, we draw on data from sections (a) and (g). Section (a) provided information on independent variables/covariates, including the following categories: gender (men/women); marital status (living/not living in a couple); children aged <12 years (yes/no); care for people with special needs (yes/no); type of academic profession (teach-ing/research); employment contract (permanent/not permanent); working time regime (full-time/part-time); age (scale); seniority in the institution (scale); education subsystem (university/polytechnic).

From section (g) of the questionnaire, we collected data on the participants’ perceived reactions to their academic work during the COVID-19 pandemic. These reactions were measured on an ordinal scale of 1 (Never), 2 (Sometimes), and 3 (Often) to indicate the frequency with which the participants experienced each reaction. The dependent variables extracted from these close-ended questions were as follows: Silence, Exclusion, Being ignored or passed over, Reluctant support, Lack of validation, Invisibility, Belittlement, Acknowledgment of respective viewpoints/positions, Compliments on the quality of work, Receiving citations, and Receiving invitations to be a keynote speaker or speaker on panels at conferences and seminars. Participants were asked to provide responses for each of these reactions based on their experiences during the pandemic. Additionally, to capture any other reactions or experiences not covered by the close-ended questions, two open spaces were included where participants could provide personal testimonies. These testimonies allowed participants to express any additional comments or experiences related to the issues addressed in this section of the questionnaire.

3.3. Data Analysis Methods

Data analysis for this study involved both quantitative and qualitative methods. The quantitative data collected from the questionnaires were processed and analyzed using SPSS statistical software (version 26). Various statistical techniques were employed, including descriptive analysis to summarize the data, inferential analysis, and univariate, bivariate, and multivariate analyses.

Frequency analysis was used to examine the distribution of responses for different variables. Contingency analysis was performed to explore associations between categorical variables. For dependent variables measured on an ordinal scale, such as the perceived reactions to academic work during the pandemic, bivariate Mann–Whitney U tests were conducted to compare score distributions between two independent groups (men and women). To investigate the relationships between dependent and independent variables, multivariate ordinal logistic regressions were employed. We considered several key socio-demographic and occupational variables as covariates (see subsection above) in the regression analyses to control for relevant factors. For statistical significance, test statistics with p-values equal to or below 0.1 were considered significant.

For the analysis of the discourses captured in the open-ended responses, we employed an essentially inductive approach, allowing the data to guide the identification of themes. In this process, our efforts were guided by the principles of inductive thematic analysis as defined by Braun and Clarke (2006). During the preliminary analysis of the material, we aimed to identify overarching categories through an open and axial coding process. Subsequently, in the second phase of analysis, each of these broad categories was further subdivided into themes related to specific factors that shaped the academic experience of teaching and research under COVID-19. The thematic analysis was carried out manually, with a focus on identifying and organizing themes based on the explicit (or semantic) content of the responses (Boyatzis 1998). To ensure rigor and reliability in the identification and selection of themes, respondents’ comments were thoroughly read and re-read by the three authors and two assistant researchers, and meaningful units of information were identified and grouped into broad categories. Through an iterative process of coding and organizing the data, recurring patterns and key concepts were identified to derive the themes. Regular meetings and discussions among the research team were held to review the codes and themes and to consolidate the categories for analysis. In this article, we focus on the category that directly relates to our main area of interest: daily working interpersonal relations under COVID-19. Under this category, a collection of 42 testimonies was grouped. From this broad category of comments, three main themes were identified. From these themes, we have selected excerpts that best represent the data collected.

3.4. Participants Characterization

We will now present the characteristics of our sample (Table 1 and Table 2) and, where possible, compare them to the overall characteristics of the target population to assess its representativeness. When examining the gender distribution, we noticed some disparities between our sample and the universe. While women constituted 45.8% of the total lecturers and researchers in higher education nationwide during the 2020/2021 academic year (DGEEC 2022), the sample exhibited a higher representation of women, at 57.3%. As shown in Table 1, out of the 1750 respondents, 1001 identified as women and 749 identified as men. The option of “non-binary” was provided, but no respondents selected that category.1 The participants in the sample ranged in age from 21 to 83 years, with an average age of 51.42 years (SD = 9.20). In comparison, the national average age of higher education lecturers at the end of 2019 was 48 years (49 for men and 47 for women) (DGEEC 2020a), indicating that our sample is relatively older than the overall population. Over one-third of survey respondents lived in households with significant caregiving responsibilities. Specifically, 29.7% (n = 520) lived with children aged 12 years or younger, while 7.6% lived with individuals requiring special daily care. The majority of the sample (86.1%) were in couple relationships, with the dual career family model being prevalent in 4 out of 5 cases.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic breakdown of the sample.

Table 2.

Socio-professional breakdown of the sample.

As shown in Table 2, regarding employment status, 87.5% of the respondents (n = 1532) had a teaching contract in a Higher Education Institution, and 12.5% (n = 218) had a contract or grant as a researcher in an R&D Center. Among the researchers, women accounted for 66% of the total, while they represented 55.9% of the teaching group. Comparing the gender distribution of our sample with the overall population, women had a greater presence in our sample compared to the national figures. In 2019/2020, women represented 45.8% of the total number of lecturers in higher education at the national level, while in our sample, they accounted for 55.9% (DGEEC 2020a). A similar situation occurs with regard to researchers: women comprised 50.1% of the total in Portugal in 2019 (DGEEC 2020b), whereas in our sample, they constituted 66%. Out of those surveyed, 77.9% (n = 1355) were integrated into teaching or research careers, meaning they held tenured or tenure-track positions. Among this group, the representation of women and men was close to parity, with women accounting for 55.9% and men representing 44.1%. However, among those who were not integrated into the career, the gender differences were more pronounced, with women comprising 66.6% and men representing 33.4% of this subgroup.

Following general trends observed for academia in the country as a whole, a more significant proportion of lecturers/researchers in the sample were present in university institutions (as compared to polytechnic institutions), although the prevalence is higher in the sample (69.8% compared to 61.4% at the national level in 2019/2020) (DGEEC 2020a).

In terms of scientific areas, our sample exhibits a configuration that closely resembles the national distribution, albeit with a relatively higher presence of the Social Sciences. This field had the highest concentration of academics in the sample, with 29.4%, compared to the national figure of 20.1% in 2019. On the other hand, the Exact and Natural Sciences had a lower representation in our sample, at 16.7%, compared to the national figure of 27.8% (DGEEC 2020b). Similarly, the career level distribution in our sample mirrors that of the national population, with a higher representation in the lowest tenure-track career category (grade C) and a relatively lower occurrence in the top category (grade A) (58.3% and 6.7% in our sample, respectively, compared to 53.2% and 4.7% in the target population in 2019/2020) (DGEEC 2020a).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Gendered Everyday Experiences under COVID-19: Changes and Continuities

The notion of gendered academic citizenship brings a significant contribution to the study of integration and exclusion processes of men and women in academia, particularly in its attention to micropolitical practices. Sümer et al. (2020) emphasize the vital role of everyday interactions in shaping subjective feelings of belonging and circulating differential levels of recognition within academic institutions and scientific communities. It is widely recognized in the literature that interpersonal dynamics within academia are also permeated by gender hierarchies, figuring as one of the many dimensions through which institutional inequalities are both created and perpetuated (Morley 1999; Acker 2006).

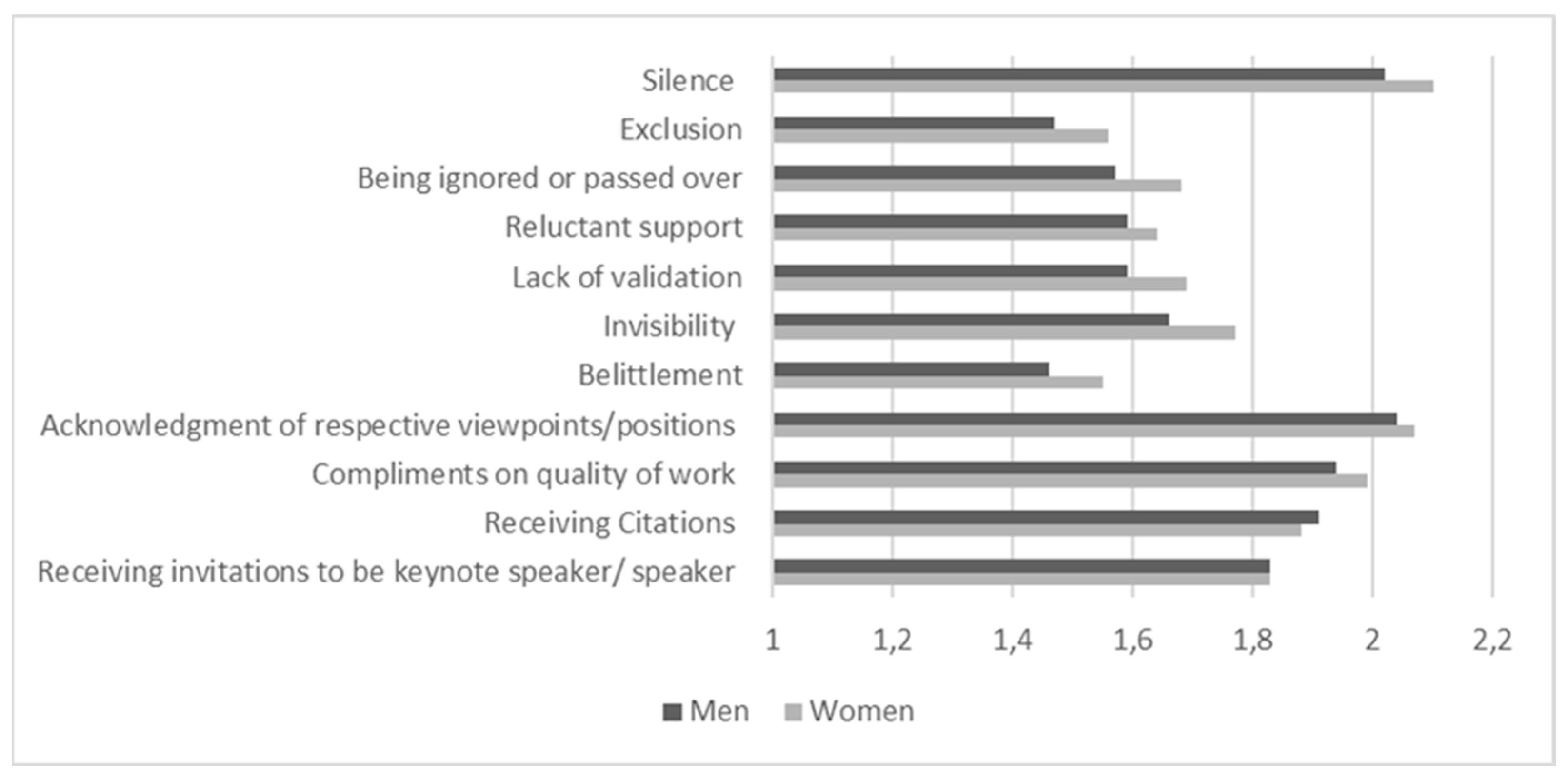

To examine the patterns in everyday interactions during the COVID-19 pandemic, lecturers and researchers were surveyed about their perceptions of the reactions they received toward their academic work. The participants were asked to indicate the frequency of eleven possible reactions they experienced during the pandemic crisis, using a scale ranging from Never (1) to Often (3). Figure 1 displays the average values of the reactions experienced by both women and men in response to their academic work during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1.

Average Frequency of reactions Towards Academic Work During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Women and Men.

Upon initial observation of the figure, it is evident that women reported experiencing a higher frequency of negative reactions compared to men. Specifically, women reported higher frequencies of reactions such as silence, exclusion, being ignored/passed over, reluctant support, lack of validation, invisibility, and belittlement. On the other hand, the results regarding perceived positive reactions and practices displayed less clear and expressive gender trends. Women reported higher frequencies of compliments on the quality of their work and acknowledgment of their viewpoints but lower frequencies of more objective forms of recognition, such as citations and invitations as keynote speakers.

To assess the statistical significance of the differences in average responses between women and men, bivariate tests (Mann–Whitney U) were conducted. The bivariate analysis provides an initial assessment of the relationship between gender and perceived reactions. The findings from these tests are presented in Table 3. The analysis revealed that almost all the gender differences in average responses associated with negative reactions, except for “reluctant support”, were statistically significant. However, none of the differences in perceived positive reactions and practices reached statistical significance.

Table 3.

Perceived receptivity toward academic’s work. Mann–Whitney U test by gender.

This means that women in the surveyed population experienced a higher prevalence of negative reactions toward their academic work during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to men. The findings suggest that gender biases persisted, and the virtual work model may have further exacerbated these issues, providing a platform for the expression of subtle forms of disempowerment and discrimination against women, which are perpetuated in the micropolitics of organizations.

The process of coding the responses to the open-ended questions of the questionnaire led to the emergence of a set of themes organized according to their contents. One of the broad categories identified in the responses was “daily working interpersonal relations under COVID-19”. The discourses grouped under this broad category conveyed three main themes, namely “deterioration of relationships during the pandemic”, “continuity of pre-pandemic relationship patterns”, and “improvement of relationships during the pandemic”, the latter theme being significantly less prevalent than the first two, particularly among women respondents. Many of the comments referred (explicitly or tacitly) to at least one of the eleven reactions listed in Table 3, particularly those comments related to the themes of “deterioration” and “continuity” of interpersonal relation patterns during the pandemic. However, no clear patterns of prevalence for each reaction were identified, preventing the construction of other sub-themes.

A comment made by a university lecturer in one of the survey’s open-ended questions illustrates one of the themes identified and is consistent with the picture drawn by the quantitative analysis regarding the deterioration of everyday working relationships under COVID-19. It points to how changes in academic work brought about by the pandemic may have contributed to the intensification of negative everyday experiences for women.

“The atmosphere among colleagues has deteriorated. The competitiveness and the moral harassment of women in academia by male colleagues have worsened. They felt more protected with the lockdown to develop disqualifying and misogynistic narratives”.(Woman Associate Professor with Aggregation at a University, 56 years old)

The comment highlights the potential impact of transitioning to a virtual work model on interpersonal relationships and the amplification of misogynistic experiences. The literature has shown how the characteristics of the architecture of the online environment, by providing the preservation of a certain degree of anonymity and impersonality, facilitate the absence of civility and disinhibition (Papacharissi 2004; Álvares 2017). In this context, men may have felt more “protected” to openly circulate misogynistic and disqualifying discourses toward their women colleagues.

However, it is essential to recognize that the way women were disproportionately affected by negative reactions to their work, as observed in our data, cannot be solely attributed to the transition to a virtual work model. Extensive research has consistently underscored the enduring nature of everyday gender discrimination against women in scientific institutions long before the onset of the pandemic (Gutek and Cohen 1992; Morley 2006; Savigny 2014; Savigny 2017; Husu 2020; Aiston and Fo 2021; Bourabain 2021; Das et al. 2023). The virtual domain is not an autonomous monad in relation to society; rather, it reflects and reenacts the longstanding social structures and power dynamics that exist in the offline societies in which we live (Loader and Mercea 2012; Brophy 2010). In this sense, a theme that emerged in the responses to the open-ended questions highlights not the changes brought about by the pandemic but the continuities in pre-existing gendered power relations:

“The belittlement to which one has been subjected for more than three decades (although I am the only one with a doctorate and an aggregation in a specific field, I do not hold an administrative position at any level) is no longer even felt, so it was not the pandemic that caused it”.(Woman Associate Professor with Aggregation at a University, 67 years old)

The comment underscores that the marginalization of women in academia is not a phenomenon exclusive to the COVID-19 pandemic but rather a longstanding issue. The teacher’s comment further highlights that the sense of belonging experienced by academics within their scientific institution does not always align with expectations based on their relative standing in other components of gendered academic citizenship. The respondent is tenured and possesses significant academic qualifications, being the most qualified in a specific field, which indicates a high level of academic “membership”. At the same time, however, she emphasizes that she does not hold any administrative position and has experienced marginalization for more than three decades, thus indicating a lack of “recognition” and a diminished sense of “belonging”.

In line with the previous testimony, other comments also demonstrate the continuity of traditional patterns of gender discrimination in scientific institutions during the sanitary crisis.

“The previous situation was characterized by a very entropic and negative atmosphere, with some faculty members falling victim to the first four attitudes on the list [the respondent refers to the reactions of “silence”, “exclusion”, “being ignored or passed over”, and “reluctant support” mentioned in the survey question]. As was also the case for me, I chose to accept a position as a Visiting Full Professor at a Brazilian university. However, the pandemic forced me to decline the opportunity and cancel my request for unpaid leave”.(Woman Associate Professor at a Polytechnic Institute, 65 years old)

“I never expect anything, so it does not surprise me that there are no great expressions of praise. It does not dissatisfy me; it is normal in Portugal. For now, I am free from feelings of ‘competition’ and ‘envy’ from colleagues, which I think is great!”.(Woman Researcher at a University Research Center, 46 years old)

The Polytechnic teacher’s remark about the “negative atmosphere” in the institution, even before the pandemic crisis, aligns with the concept of a “chilly climate” introduced by Hall and Sandler (1982). This term describes the pervasive patterns of unequal treatment within the academic environment that, as they accumulate, undermine confidence and self-esteem and disproportionately affect women’s achievements and sense of belonging to institutions (Britton 2017). Prentice (2000) further emphasizes that the “chilly climate” includes “a compounding of everyday practices which block women’s full participation in the university” (Prentice 2000, p. 196). Aside from providing a good example of what an organizational “chilly climate” looks like, the comment also shows how the cumulative effect of small, everyday negative interactions can lead to women’s withdrawal from academic institutions (Brennan 2013), thus shedding light on the connections between micropolitical practices and more visible phenomena such as leaky pipelines (Sümer and Eslen-Ziya 2023).

In turn, the comment made by the woman researcher begins with a certain tone of resignation, indicating that negative daily interactions, due to their ubiquity and longevity, have been practically normalized as part of organizational cultures in the country (“it is normal in Portugal”). The respondent then mentions a rather surprising “positive” aspect of not being recognized or praised for her academic work during the pandemic, as it frees her from competition and envy from colleagues. Thus, we observe the complex interplay of broad power dynamics and how they are contextually sedimented: the gender bias that informs the differential distribution of recognition between men and women in scientific institutions interacts with the increasing academic competitiveness, a characteristic of the prevailing model of the neoliberal and performative university (Santos 2014; Hark 2016; Ferreira 2019).

4.2. Intersecting Micropolitical Inequalities

To further investigate the influence of gender on perceived reactions toward academic work and examine the intersections between gender and other social markers, we employed multivariate regression analyses. By using ordinal logistic regressions, we controlled for the potential effects of socio-demographic and occupational variables known to shape individuals’ experiences. This approach allowed us to assess the independent contribution of gender in explaining variations in perceived reactions while considering the intersecting effects of other factors, namely marital status, presence of children, academic profession, employment contract type, working time regime, age, seniority in the institution, and education subsystem (cf. methods session). The results, presented in Table 4, provide information on the statistical significance and magnitude of the associations between these variables and respondents’ perceived reactions. This analysis provides valuable insights into the complex relationship between gender and perceived reactions toward academic work, taking into account the effects of other influential factors.

Table 4.

Perceived reactions toward academic’s work. Ordinal regression estimates.

After conducting the regression analysis, gender remained a significant predictor for all the perceived negative reactions identified as gender-relevant in the bivariate analysis, including silence, exclusion, being ignored/passed over, lack of validation, invisibility, and belittlement. This indicates that gender plays a crucial role in determining the experiences of academics in terms of the negative reactions they receive toward their work, even after controlling for socio-demographic and occupational variables.

Moreover, the regression analysis revealed that other factors also contributed to the perceived reactions, highlighting the complexity and multifaceted nature of gender-based inequality (e.g., Crenshaw 1995). Variables such as age, marital status, caregiving responsibilities for people with special needs, working time regime, and seniority in the institution emerged as significant predictors. This implies that individuals who are single, with caregiving responsibilities for people with special needs, and younger and earlier career academics working full-time are particularly susceptible to experiencing “everyday” microaggressions, which reflect the subtle power dynamics and informal practices that impact academics’ experiences (O’Connor et al. 2020).

These results highlight the complex interplay between gender dynamics, marital status, caregiving responsibilities, work arrangements, and institutional hierarchy in shaping the experiences of academics during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings suggest that single women with caregiving responsibilities for people with special needs, working full-time in the early stages of their careers, face heightened vulnerability to “cultural sexism” (Savigny 2014) in the academic environment, reflecting the ways in which “power is relayed in everyday practices” (Morley 2000, p. 232).

Previous studies focusing on women in science (Herschberg et al. 2019; Steinþórsdóttir et al. 2019), including some specifically examining the effects of the pandemic (Cardel et al. 2020; Meehan et al. 2021; Ghislieri et al. 2022), have consistently highlighted the unique challenges and disadvantages faced by early career academics compared to more senior faculty members. These challenges include precarious employment, limited resources, and limited opportunities for career advancement (Herschberg et al. 2019; Spina et al. 2022). Moreover, the early career phase, which aligns with significant personal life events such as starting a family or securing a mortgage, can render women researchers more vulnerable (Brandser and Sümer 2020). Early career academics are particularly vulnerable to the process of precarization currently affecting higher education (Murgia and Poggio 2019). The vulnerability of early career academics to the process of precarization is closely linked to cultural changes in the research sector, such as evolving management models and the pervasive influence of neoliberal rationality within universities (Vohlídalová 2021). Our study complements these analyses by shedding light on the subtle mechanisms of segregation and disempowerment experienced by individuals, particularly women, in the early stages of their careers. We found that as seniority decreases, there is an increase in the frequency of perceived negative reactions toward academic work, specifically in the form of microaggressions such as “exclusion”, “being ignored or passed over”, and “lack of validation”.

Other intersectional populations that our results portray as particularly vulnerable to micropolitical processes contributing to the perpetuation of asymmetries in academic work during the pandemic include caregivers of dependents with daily special needs. This group refers to individuals who provide daily care and support to individuals with diseases, elderly individuals with special needs, or those with disabilities. The findings from the ordinal regression analysis indicate that being a caregiver of a person with special needs is a significant factor in explaining the perception of various negative reactions toward their work during the pandemic, including silence, exclusion, being ignored/passed over, lack of validation, invisibility, and belittlement. These findings align with previous descriptions of the academic environment as “careless” (Lynch 2010), where caregiving responsibilities are often seen as incompatible with the scientific career. The increased care responsibilities resulting from stay-at-home orders and the closure of daycare services during the pandemic intensified the challenges faced by academics who provide care for dependents with special needs. Previous studies have raised concerns about the detrimental effects of these circumstances on the lives of academics, particularly women (Nash and Churchill 2020; Kotini-Shah et al. 2022).

The results of our study reveal an interesting pattern in these daily experiences of academics during the COVID-19 pandemic. While we found that the intersection between gender and caregiving for individuals with special daily needs significantly influenced the negative interactions experienced by women, we did not observe a similar influence when it came to the presence of children under 13 years of age in the household. This difference may be explained by the wide symbolic societal recognition of parenthood and the acceptance of mothers caring for young children (Hochschild and Machung 2012). Such recognition aligns with social expectations and creates a more supportive academic environment for mothers. In contrast, caring for individuals with special needs may be less visible (Brown and Leigh 2018) or perceived as more challenging (Earle and Heymann 2012), leading to a lack of awareness and accommodation for academics in such caregiving roles.

Our findings challenge prevalent conceptions about the impact of motherhood on women’s integration in academia, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Prior research has shown that motherhood often leads to additional challenges and penalties for women in academic careers (Mirick and Wladkowski 2018; Wolf-Wendel and Ward 2006). Moreover, there has been a growing concern that the pandemic has further exacerbated the penalization of motherhood in academia (Kelly and Senior 2020; Burk et al. 2021; Wagner et al. 2022). Studies report that academic mothers, especially those with young children, experienced significant declines in research productivity and output during the pandemic (Lutter and Schröder 2020; Krukowski et al. 2021; Myers et al. 2020; Ferreira et al. 2021; Lopes et al. 2021; Meehan et al. 2021).

The evidence from this study, however, suggests a different perspective. While motherhood may visibly impact professional routines and research productivity, it does not appear to have a significant influence on the perceived negative reactions experienced in everyday interactions that undermine the components of “recognition” and “belonging” within the framework of “gendered academic citizenship”. This unexpected finding calls for a nuanced understanding of the experiences of mothers in academia. It highlights the need to recognize that the impact of motherhood on various aspects of academic life may differ.

Our findings on marital status also challenge prevalent notions on the impact of marriage on women’s academic trajectories and experiences (Wolfinger et al. 2008; Goulden et al. 2011; Takahashi and Takahashi 2015). The regression results indicate that single women are more prone to perceive reactions of “exclusion” and “invisibility”. Cultural expectations surrounding marriage and gender roles can play a significant role in these micropolitical dynamics. In cultures dominated by an ideology of marriage and family life (Budgeon 2008), married women may be perceived as having more stability and support systems, which could potentially provide some protection against microaggressions. On the other hand, single women may be seen as more independent and less tied to traditional roles (DePaulo and Morris 2005), which could make them more susceptible to subtle discrimination. Additionally, the experiences of single women may be influenced by other factors such as social networks, access to resources, and institutional support. Married women may have access to support from wider social networks, which could provide them with more opportunities and resources to navigate and address microaggressions. Single women, on the other hand, may lack such support systems and may face additional challenges in addressing and overcoming microaggressions.

The comment of a married university lecturer with young children illustrates such contrasting effects of motherhood and marriage at the level of more visible indicators (scientific productivity) and in terms of patterns of everyday interaction with colleagues, superiors, and management.

“I feel very frustrated, and I feel like I have not been able to make progress throughout this year (March 2020–March 2021) or produce the scientific outputs that I had planned. We were only able to carry out the scheduled experiments, but the same did not happen with the planned articles. I feel a great inequality compared to unmarried colleagues without children, who were not affected by the pandemic in the same way. I spend my days working, I am still working on a project right now, I am very tired, and it seems like we are not accomplishing anything because we do not want to […] Fortunately, neither my research team coordinator nor the organization in the institution blame nor penalize me for the situation. There is a lot of understanding. But of course, I feel frustrated for not being able to meet the outputs that I set for myself”.(Woman Assistant Professor at a University, 41 years old)

On the other hand, a comment from an unmarried lecturer without children, which illustrates the theme of deterioration of everyday working interpersonal relations during the pandemic, shows how the combination of these markers seems to be associated with negative experiences in terms of interactions with colleagues and superiors.

“There was no psychological support [from the institution]. On the contrary, there was psychological harassment, which contributed to the faculty member’s psychological and even physical distress. The feeling of not being recognized for my efforts and the arrogance of the director and the president of the Unit’s Board proved to be detrimental to the faculty member”.(Women Assistant Professor at a Polytechnic Institute, 46 years old)

Moreover, our unexpected findings on the effects of motherhood and marital status reveal how traditional social expectations of femininity influence everyday interactions and interpersonal dynamics within scientific organizations. While motherhood and marriage are factors that tend to disadvantage women academics in indicators such as salary, tenure, and promotion, at the micropolitical level, these elements may actually have the opposite effect, being associated with a lower frequency of negative experiences regarding everyday transactions. Thus, our findings shed light on the subtle ways in which normative models of femininity are valued and reproduced in academic cultures, such that women who conform to traditional roles of mother and wife hold a symbolic advantage over women who do not adhere to these roles and are less likely to experience everyday microaggressions.

5. Conclusions

With recent advancements in gender equality policies and the development of anti-discrimination legislation, the official and institutionalized practices of exclusion and subordination of women in academia have lost ground around the world. However, scientific institutions still bear deep gender asymmetries. While efforts have been made to eradicate discrimination, the complexities beyond the broad indicators of gender equality require a micropolitical analytical perspective for a comprehensive understanding (Morley 2006). Building upon this perspective, our analysis sheds light on the micropolitical processes that contribute to the perpetuation of gender asymmetries in academic work, uncovering insights not thoroughly explored in previous studies within the Portuguese context.

The trends revealed by our results shed light on the ongoing challenges faced by women in academia, as they continue to encounter more negative reactions toward their work compared to men, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. These findings indicate that gendered power dynamics within academia persist not only through overt mechanisms of segregation but also through subtle practices embedded in everyday interactions and interpersonal dynamics (Acker 2006; Morley 2006; Savigny 2014; Savigny 2017; Husu 2020; Aiston and Fo 2021; Bourabain 2021; Das et al. 2023).

As emphasized by Ridgeway (2009, p. 146), gender inequalities encompass multi-level phenomena involving hierarchies produced through the articulation and mutual reinforcement of processes occurring at macrostructural/institutional, interpersonal, and individual levels. Our findings uncover experiences of silencing, exclusion, belittlement, being ignored, lack of validation, and invisibility, which can be understood as forms of microaggressions permeating the daily lives of women lecturers and researchers. These experiences undermine women’s ability to develop a strong sense of belonging to their scientific community and gain recognition from colleagues, consequently reducing their prospects of achieving full academic citizenship.

Our study shows that the virtual work model has provided a platform for the expression of subtle forms of disempowerment and discrimination against women, potentially exacerbating sexist everyday interactions within the work environment. However, the testimonies gathered in our study clearly indicate that the “chilly climate” for women is not exclusive to the virtual work context. Instead, they reflect the enduring nature of everyday gender discrimination against women in scientific institutions, which predates the pandemic.

Furthermore, our findings demonstrate that the experiences of microaggressions within academia are not uniformly distributed among women, indicating the presence of intersecting factors such as age, marital and family status, and seniority that further shape and compound the inequalities experienced by women in their pursuit of full academic citizenship. This highlights the complexity of gender-based inequality and the need for an intersectional analysis that considers the interplay between gender and other forms of discrimination. By adopting this approach, we gain a deeper understanding of the complex social relations that contribute to diverging experiences among women.

The concept of gendered academic citizenship has been instrumental in capturing the intricate power dynamics and everyday practices within academia. It has highlighted the multiple—and sometimes contradictory—positions women occupy in social power relations, experiencing both privilege and oppression across different dimensions of academic citizenship. Our focus on the emotional and relational aspects of academic citizenship has revealed that women may simultaneously enjoy certain privileges in terms of academic “membership” while experiencing oppression in terms of “recognition” and “belonging”. By challenging prevailing assumptions about the impact of marital and family status on women’s academic trajectories, which have traditionally focused on formal aspects of academic citizenship such as tenure status, salary, and promotion, our study underscores the non-uniformity of women’s experiences.

These findings highlight the need for a nuanced understanding of gender inequality and its various dimensions. By acknowledging the diverse experiences of women in academia, we can better address the challenges they face and foster an academic culture that values and supports women in all dimensions of academic citizenship. With insights into the “lived experiences” of academics, our study provides a foundation for addressing and mitigating the microaggressions experienced by women in their academic work environments.

Future studies dedicated to analyzing, from a micropolitical perspective, the intersectional dynamics that negatively impact the academic citizenship of certain groups could broaden the scope of social markers of difference explored in this study. Specifically, there is a need to further investigate how certain social markers, such as sexual orientation and non-normative gender identity, generate specific intersectional inscriptions that influenced the experiences of academics in scientific institutions during the COVID-19 crisis. As highlighted by Morley and Leyton (2023, p. 52), this area of research remains particularly underexplored in the literature on the gendered impacts of the pandemic on higher education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L. and V.F.; methodology, M.L. and V.F.; software, C.S.; validation, M.L. and V.F.; formal analysis, M.L., V.F. and C.S.; investigation, M.L., V.F. and C.S.; data curation, C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, V.F., C.S. and M.L.; writing—review and editing, M.L., C.S. and V.F.; visualization, C.S.; supervision, M.L. and V.F.; project administration, V.F.; funding acquisition, V.F. and M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financed by Portuguese funds through FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology under the projects “Pandemic and Academia at home—what effects on teaching, research and career? Study on the changes in the scientific and higher education system” (RESEARCH GENDER 4 COVID, grant 77) and “ENGENDER: Gender mainstreaming in curricula and pedagogical practices in Portuguese Public Universities” (ref. PTDC/SOC-ASO/7173/2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Centre for Social Studies of the University of Coimbra (opinion 09 issued on 8 March 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available yet due to the Portuguese privacy law. The data are available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Cristina Coimbra Vieira (study and research conceptualization), Luísa Winter and Joana Silva (data collection) and Florbela Vitória (statistical analysis).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Note

| 1 | We acknowledge that traditional survey instruments that seek to gather information on gender identity by relying on discrete and fixed categories do not sufficiently respond to the complexities of non-normative and queer forms of identification (Ruberg and Ruelos 2020; Morley and Leyton 2023). Our decision to include a third option in the questionnaire so as not to limit the possibilities of responses to the categories of woman/man represents an effort aimed at adapting these instruments. |

References

- Acker, Joan. 1992. From Sex Roles to Gendered Institutions. Contemporary Sociology 21: 565–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, Joan. 2006. Inequality Regimes: Gender, Class, and Race in Organizations. Gender & Society 20: 441–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, Sandra, and Anne Wagner. 2019. Feminist Scholars Working Around the Neoliberal University. Gender and Education 31: 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiston, Sarah Jane. 2011. Equality, Justice and Gender: Barriers to the Ethical University for Women. Ethics and Education 6: 279–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiston, Sarah Jane, and Chee Kent Fo. 2021. The silence/ing of academic women. Gender and Education 33: 138–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldossari, Maryam, and Sara Chaudhry. 2021. Women and Burnout in the Context of a Pandemic. Gender, Work & Organization 28: 826–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvares, Cláudia. 2017. Pós-feminismo, misoginia online e a despolitização do privado. Media & Jornalismo 17: 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, Jens P., Mathias W. Nielsen, Nicole L. Simone, Resa Lewiss, and Reshma Jagsi. 2020. COVID-19 Medical Papers Have Fewer Women First Authors Than Expected. Department of Radiation Oncology Faculty Papers. Available online: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/radoncfp/134 (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Augustus, Jo. 2021. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Women Working in Higher Education. Frontiers in Education 6: 648365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basford, Tessa E., Lynn R. Offermann, and Tara S. Behrend. 2014. Do You See What I See? Perceptions of Gender Microaggressions in the Workplace. Psychology of Women Quarterly 38: 340–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, Laura. 2016. Everyday Sexism: The Project That Inspired a Worldwide Movement. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Bourabain, Dounia. 2021. Everyday Sexism and Racism in the Ivory Tower: The Experiences of Early Career Researchers on the Intersection of Gender and Ethnicity in the Academic Workplace. Gender, Work and Organization 28: 248–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, Richard E. 1998. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Washington, DC: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Brandser, Gry, and Sevil Sümer. 2020. Gender and Academic Citizenship Practices: The Norwegian Case. In Gendered Academic Citizenship: Issues and Experiences. Edited by Sevil Sümer. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 103–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, Samantha. 2013. Rethinking the Moral Significance of Micro-inequities: The Case of Women in Philosophy. In Women in Philosophy: What Needs to Change? Edited by Katrina Hutchison and Fiona Jenkins. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 180–96. [Google Scholar]

- Britton, Dana M. 2017. Beyond the Chilly Climate: The Salience of Gender in Women’s Academic Careers. Gender & Society 31: 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, Jessica. 2010. Developing a Corporeal Cyberfeminism: Beyond Cyberutopia. New Media & Society 12: 929–45. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Jennifer V. E., Paul E. S. Crampton, Gabrielle M. Finn, and Jessica E. Morgan on Behalf of the Project Team. 2020. From the Sticky Floor to the Glass Ceiling and Everything in Between: Protocol for a Systematic Review of Barriers and Facilitators to Clinical Academic Careers and Interventions to Address These, with a Focus on Gender Inequality. Systematic Reviews 9: 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Nicole, and Jennifer Leigh. 2018. Ableism in academia: Where are the disabled and ill academics? Disability & Society 33: 985–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budgeon, Shelly. 2008. Couple Culture and the Production of Singleness. Sexualities 11: 301–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burk, Brooke N., Anna Pechenik Mausolf, and Linda Oakleaf. 2021. Pandemic motherhood and the academy: A critical examination of the leisure-work dichotomy. Leisure Sciences 43: 225–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabero, Ismael, and Irene Epifanio. 2021. A Data Science Analysis of Academic Staff Workload Profiles in Spanish Universities: Gender Gap Laid Bare. Education Sciences 11: 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardel, Michelle I., Natalie Dean, and Diana Montoya-Williams. 2020. Preventing a Secondary Epidemic of Lost Early Career Scientists: Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic on Women with Children. Annals of the American Thoracic Society 17: 1366–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé Williams. 1995. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. In Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement. Edited by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, Neil Gotanda, Gary Peller and Kendall Thomas. New York: The New Press, pp. 357–83. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Ruomeng, Hao Ding, and Feng Zhu. 2022. Gender Inequality in Research Productivity During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management 24: 707–26. [Google Scholar]

- Currie, Jan. 2012. Gender Pay Equity Reviews in Australian and Swedish Universities: Are They an Impetus for Change? Journal of Critical Studies in Business & Society 3: 129–57. [Google Scholar]

- Das, Sarmistha, Obja Borah Hazarika, and Sriparna Pathak. 2023. Everyday Sexism in Higher Education: Narratives of Women in Indian Academia. Journal of Gender Studies 32: 588–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deem, Rosemary, Sam Hilliard, and Michael Reed. 2008. Knowledge, Higher Education and the New Managerialism: The Changing Management of UK Universities. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- DePaulo, Bella, and Wendy Morris. 2005. Single in Society and Science. Psychological Inquiry 16: 57–83. [Google Scholar]

- Deryugina, Tatyana, Olga Shurchkov, and Jenna E. Stearns. 2021. COVID-19 Disruptions Disproportionately Affect Female Academics. NBER Working Paper No. 28360. Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w28360 (accessed on 29 March 2023).

- Direção-Geral de Estatísticas da Educação e Ciência—DGEEC. 2020a. Principais Resultados do Perfil do Docente do Ensino Superior-2019/20. Available online: https://www.dgeec.mec.pt/np4/461/%7B$clientServletPath%7D/?newsId=1053&fileName=DGEEC_DSEE_DEES_2020_DestaqueDocentes_20.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2023).

- Direção-Geral de Estatísticas da Educação e Ciência—DGEEC. 2020b. Inquérito ao Potencial Científico e Tecnológico Nacional (IPCTN19)-Sumários Estatísticos-Setor Ensino Superior. Available online: https://www.dgeec.mec.pt/np4/206/%7B$clientServletPath%7D/?newsId=11&fileName=IPCTN19_SumEstatisticos_EnsinoSuperior.xlsx (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Direção-Geral de Estatísticas da Educação e Ciência—DGEEC. 2022. Perfil do Docente do Ensino Superior-2020/21. Available online: https://www.dgeec.mec.pt/np4/461/ (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Earle, Alison, and Jody Heymann. 2012. The cost of caregiving: Wage loss among caregivers of elderly and disabled adults and children with special needs. Community, Work & Family 15: 357–75. [Google Scholar]

- Elsevier. 2021. Gender in the Portugal Research Arena: A Case Study in European Leadership. London and New York: RELX Analytical Services. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission/Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. 2016. She Figures 2015. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission/Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. 2019. She Figures 2018. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission/Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. 2021. She Figures 2021. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, Virgínia. 2019. Estudos de Género na universidade performativa. Paper presented at the XIII Congreso Español de Sociología, Valencia, Spain, July 3–6; Valencia: Facultat de Ciències Socials, Campus de Tarongers, Universitat de València, Espanha. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, Virgínia, Cristina C. Vieira, Mónica Lopes, and Caynnã Santos. 2021. Pandemia e Academia em Casa: Efeitos no ensino, na investigação e na cidadania académica sob uma perspetiva de género. Coimbra: CES. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1991. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- França, Thais, Filipa Godinho, Beatriz Padilla, Mara Vicente, Lígia Amâncio, and Ana Fernandes. 2023. Having a family is the new normal”: Parenting in neoliberal academia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gender, Work & Organization 30: 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ghislieri, Chiara, Domenico Sanseverino, Tindara Addabbo, Vincenzo Bochicchio, Rosy Musumeci, Ilenia Picardi, Patrizia Tomio, Gloria Guidetti, and Daniela Converso. 2022. The Show Must Go On: A Snapshot of Italian Academic Working Life during Mandatory Work from Home through the Results of a National Survey. Social Sciences 11: 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, Jeffrey. 2008. The Sociology of Micro-politics: An Examination of a Neglected Field of Political Action in the Middle East and Beyond. Sociology Compass 2: 1816–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górska, Anna, Karolina Kulicka, Zuzanna Staniszewska, and Dorota Dobija. 2021. Deepening Inequalities: What Did COVID-19 Reveal about the Gendered Nature of Academic Work? Gender, Work & Organization 28: 1546–61. [Google Scholar]

- Goulden, Marc, Mary Ann Mason, and Karie Frasch. 2011. Keeping women in the science pipeline. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 638: 141–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutek, Barbara A., and Groff A. Cohen. 1992. Sex ratios, sex role spill over, and sex at work: A comparison of men’s and women’s experiences. In Gendering Organizational Analysis. Edited by Albert J. Mills and Peta Tancred. Washington, DC: Sage, pp. 133–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Roberta M., and Bernice R. Sandler. 1982. The Classroom Climate: A Chilly One for Women? Project on the Status and Education of Women–Association of American Colleges. Available online: http://eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED215628.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2023).

- Hark, Sabine. 2016. Contending directions. Gender studies in the entrepreneurial university. Women’s Studies International Forum 54: 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, Eti, David Nicholas, Anthony Watkinson, Blanca Rodríguez-Bravo, Abdullah Abrizah, Chérifa Boukacem-Zeghmouri, Hamid R. Jamali, David Sims, Suzie Allard, Carol Tenopir, and et al. 2021. The Impact of the Pandemic on Early Career Researchers: What We Already Know from the Internationally Published Literature. Profesional de la Información 30: e300208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herschberg, Channah, Yvonne Benschop, and Marieke Van den Brink. 2019. The peril of potential: Gender practices in the recruitment and selection of early career researchers. In Gender and Precarious Research Careers: A Comparative Analysis. Edited by Annalisa Murgia and Barbara Poggio. Abingdon and Oxford: Routledge, pp. 111–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, Arlie, and Anne Machung. 2012. The Second Shift: Working Families and the Revolution at Home. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Husu, Liisa. 2020. What Does Not Happen: Interrogating a Tool for Building a Gender-Sensitive University. In The Gender-Sensitive University: A Contradiction of Terms? Edited by Eileen Drew and Siobhán Canavan. Oxford: Routledge, pp. 166–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Liz. 2017. Leaning Out in Higher Education: A Structural, Postcolonial Perspective. Policy Futures in Education 15: 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, Heather L. 2017. Pipelines, Pathways, and Institutional Leadership: An Update on the Status of Women in Higher Education. American Council on Education and the Center for Policy Research and Strategy. Available online: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/84062/UpdateWomenHigherEducation.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- Jones, Stephanie J., and Elyn M. Palmer. 2011. Glass Ceilings and Catfights: Career Barriers for Professional Women in Academia. Advancing Women in Leadership Journal 31: 189–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasymova, Salima, Jean Marie S. Place, Deborah L. Billings, and Jesus D. Aldape. 2021. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Productivity of Academics Who Mother. Gender, Work & Organization 28: 419–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, Simon, and Adele Senior. 2020. Toward a feminist parental ethics. Gender, Work & Organization 28: 807–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotini-Shah, Pavitra, Bernice Man, Ruth Pobee, Laura E. Hirshfield, Barbara J. Risman, Irina A. Buhimschi, and Heather M. Weinreich. 2022. Work-Life Balance and Productivity among Academic Faculty During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Latent Class Analysis. Journal of Women’s Health 31: 321–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]