How Do Professionals Regard Vulnerable People in a Portuguese Community Setting? A Qualitative Content Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Setting, Participants, and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Study Rigor

2.6. Ethics

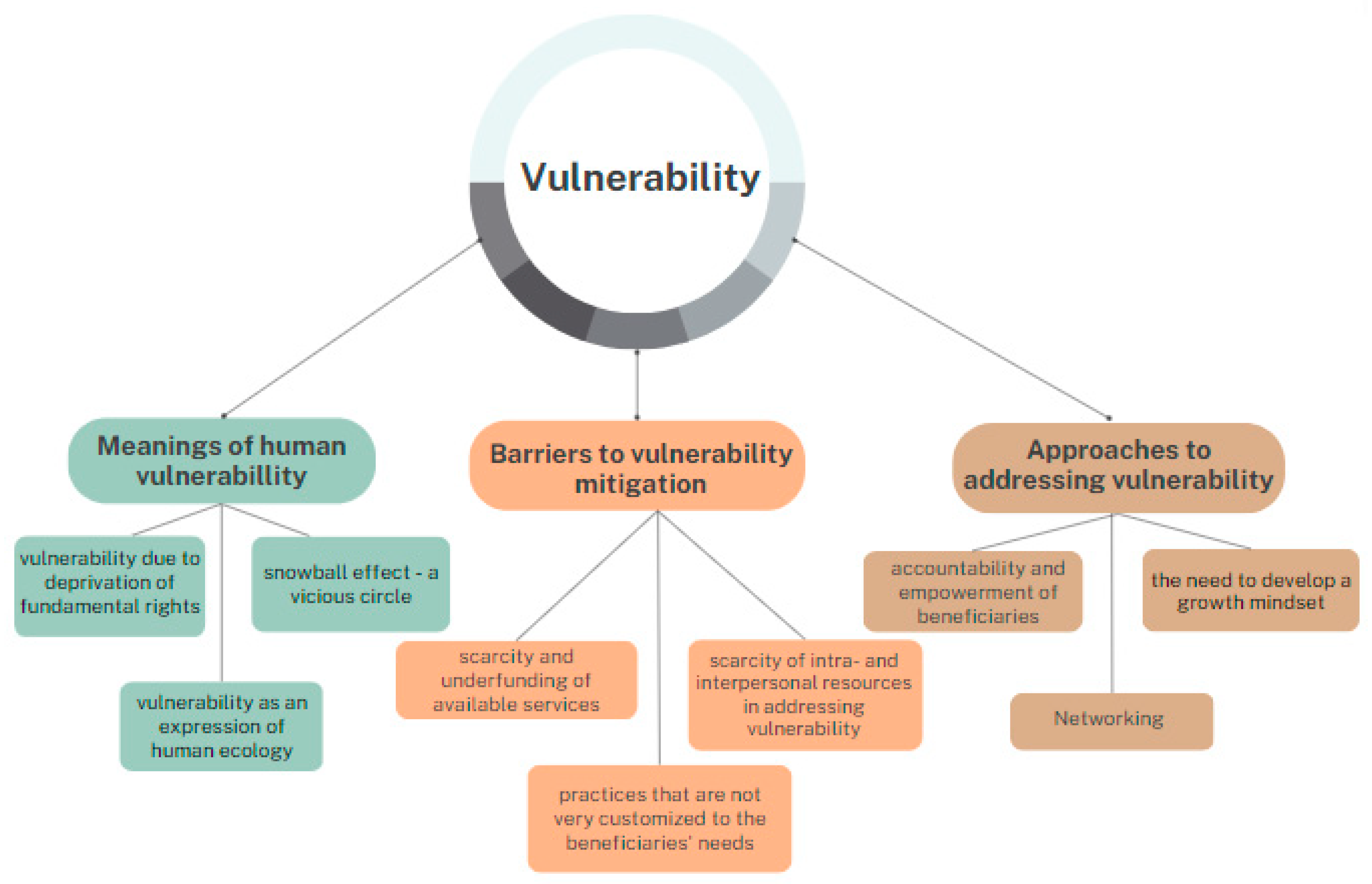

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Findings from Interviews

3.2.1. Meanings of Human Vulnerability

P11: “Nowadays access to many services is practically only done online. […] some services stopped working in person […] it is also a vulnerability”.

P12: “[…] we are in a post-pandemic period and in which human relationships existed, but they existed in a completely different way […] and we feel in these children […] this difficulty in dealing with themselves and with the other”.

P6: “the easiest refuge is through consumption […] an easier and more immediate escape. Then there are its effects linked to the consumption of illicit substances”.

3.2.2. Barriers to Vulnerability Mitigation

P15: Homeless people should not be on the street for more than 24 h, but then in practice, this does not materialize, because there are no effective responses on the ground [...] we do not have enough means or resources […] we call the social emergency line and they don’t respond immediately, so the whole structure itself is not working.

P5: “[…] the bureaucratic burden and the complexity associated with these processes are great […] there is also a lack of sensitivity on the part of the services themselves and a great lack of preparation of professionals in this area […]”.

P14: “[…] Sometimes we want to develop skills with people who can’t develop them at all, and this limits the effectiveness of interventions”.

P13: “[…] People need other types of support (especially in the health area), psychological support, and other responses that allow us to refer people”.

P4: [...] the biggest difficulty, deep down, is for us to understand what the other person sometimes wants [...] This leads us to disappointments [...] and disappointment is created because we create expectations [...]. It’s hard to go home knowing the problems we all deal with daily [...] sometimes it’s hard to dissociate their problems from ours.

P15: “I feel that sometimes there is a feeling of ingratitude towards our work [...] but our mission is to create empathetic relationships. But sometimes we get too involved and find it difficult to distance ourselves”.

P6: “[…] many questions make me think and reflect […] in professional terms […] we think we know the right path for people, but that doesn’t always happen […]”.

P10: “Many times, we set expectations that will be good for them, but then they don’t meet our expectations”.

P3: “[…] Sometimes we believe more in people than they believe in themselves”.

3.2.3. Approaches to Addressing Vulnerability

P4: “[…] it is very important. The person is focused and the interest emerges from them to emancipate and reintegrate in society”.

P3: I think that […] putting the person at the center of the intervention is fundamental, considering that each person is a person. We here at InPulsar have a principle, which is the principle of humanism: treating all people with respect. All people are human beings who deserve to be heard and this is an essential point [...].

P7: “It is good practice to provide our users with some strategies for emotional management, communication, and how to communicate more assertively […] this helps them integrate into the community”.

P9: “[…] Whenever there is a request for help, we try to respond as best we can; and when we don’t succeed, we look for other partners […] answers in terms of clothing and food”.

P3: “[...] we mobilize all the support that exists, in terms of economic support, training that exists [...] to fill the identified needs and often access to services they can take advantage of”.

P4: […] our resources, more and more, we have a network of beneficial resources […] nobody should be on the street more than 24 h, right? And, unfortunately, we haven’t been able to bridge that yet. And, therefore, there is this lack of resources here […] to give that immediate response.

P2: “[…] meetings are important moments that help us make more informed and enlightened decisions”.

P13: “[…] engagements with stakeholders are crucial for our purposes”.

P1: “[…] it is an enriching experience because every day we learn from them […] they manage to deal with what they have and want to change […] they realize that we are here for them […]”.

P8: “[…] I use my life experience, and my life path as a tool to solve my problems”.

P7: “[…] we often need to be creative […] in the sense of creating other options for what would be obvious to resolve […] It is often necessary to think outside the box, completely “out of the box”, to be able to resolve immediate situations [...]”.

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

4.2. Implications for Policy and Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adobor, Henry. 2022. Vulnerability, Moral Responsibility, and Moral Obligations: The case of Industrial Action in the Medical and Allied Professions. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 25: 333–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, Julia, and Joanna Sleigh. 2021. Too Vulnerable to Involve? Challenges of Engaging Vulnerable Groups in the Co-production of Public Services through Research. International Journal of Public Administration 44: 715–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Mohamed, Lotte Nørgaard, Afonso Cavaco, Matthew Witry, Lisa Hillman, Alina Cernasev, and Shane Desselle. 2020. Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Research in Social & Administrative Pharmacy: RSAP 16: 1472–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldt, Joachim. 2019. The concept of vulnerability in medical ethics and philosophy. Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine 14: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brantmeier, Edward. 2021. A Pedagogy of Vulnerability for Troubled Times; James Madison University. Available online: https://www.jmu.edu/cfi/_files/t-t_21-22/10.07.21-pedagogy-of-vulnerability.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Brown, Kate. 2011. Vulnerability: Handle with Care. Ethics and Social Welfare 5: 313–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carden, Julia, Rebecca Jones, and Jonathan Passmore. 2022. Defining Self-Awareness in the Context of Adult Development: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Management Education 46: 140–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Beth, and Nina Preto. 2018. Exploring the concept of vulnerability in health care. Canadian Medical Association Journal 190: 308–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, Janet. 2021. Vulnerability as a key concept in relational patient-centered professionalism. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 24: 155–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Direção Geral de Saúde. 2021. Plano Nacional de Saúde 2021–2030. Lisboa: Direção Geral de Saúde. Available online: https://pns.dgs.pt/files/2023/02/PNS2021-2030_Saude-da-Populacao-em-Portugal.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- European Commission. 2021. European Network of Public Employment Services (PES); Luxembourg: European Commission: Social Europe. [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. 2022. Living Conditions in Europe—Poverty and Social Exclusion. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Living_conditions_in_Europe_-_poverty_and_social_exclusion (accessed on 18 June 2023).

- Fawcett, Barbara. 2009. Vulnerability: Questioning the certainties in social work and health. International Social Work 52: 473–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fineman, Martha Albertson. 2013. Equality, autonomy and the vulnerable subject in Law and Politics. In Vulnerability: Reflections on a New Ethical Foundation for Law and Politics. Edited by Martha Albertson Fineman and Anna Grear. Surrey: Ashgate, pp. 13–28. Available online: https://www.perlego.com/book/1632306/vulnerability-reflections-on-a-new-ethical-foundation-for-law-and-politics-pdf (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Fineman, Martha Albertson. 2019. Vulnerability and Social Justice. Valparaiso University Law Review 53: 341–69. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/303865322.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023). [CrossRef]

- Fineman, Martha Albertson. 2021. Universality, Vulnerability, and Collective Responsibility. Les ateliers de l’éthique/The Ethics Forum 16: 101–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, Kim, Zoreh Eslami, and Hassan Bashir. 2018. Culture’s influence on social network vulnerabilities for ethnic minorities in rural disaster events. Journal of International Humanitarian Action 3: 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilodi, Amalia, Isabelle Albert, and Birte Nienaber. 2022. Vulnerability in the Context of Migration: A Critical Overview and a New Conceptual Model. Human Arenas 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneheim, Ulla, and Berit Lundman. 2004. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today 24: 105–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneheim, Ulla, Brit-Marie Lindgrena, and Berit Lundman. 2017. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Education Today 56: 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häfliger, Clara, Nicola Diviani, and Sara Rubinelli. 2023. Communication inequalities and health disparities among vulnerable groups during the COVID-19 pandemic—A scoping review of qualitative and quantitative evidence. BMC Public Health 23: 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Soo Jeoung, and Vicki Stieha. 2020. Growth Mindset for Human Resource Development: A Scoping Review of the Literature with Recommended Interventions. Human Resource Development Review 19: 309–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Soo Jeoung, Lei Xie, Michael Beyerlein, and Rodney Boehm. 2022. Examining the mediating role of team growth mindset on the relationship of individual mindsets and shared leadership. European Journal of Training and Development, ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herring, Jonathan. 2016. Vulnerable Adults and the Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization. 2023. World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2023. Geneva: International Labour Office. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Hyejin, Justine Sefcik, and Christine Bradway. 2017. Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: A systematic review. Research in Nursing & Health 40: 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, Amanda. 2022. From Vulnerability to Empowerment: Critical Reflections on Canada’s Engagement with Refugee Policy. Laws 11: 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, Margaret E., Anna D. Gage, Catherine Arsenault, Keely Jordan, Hannah H. Leslie, Sanam Roder-DeWan, Olusoji Adeyi, Pierre Barker, Bernadette Daelmans, Svetlana V. Doubova, and et al. 2018. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: Time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health 6: 1196–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laranjeira, Carlos, Inês Piaça, Henrique Vinagre, Ana Rita Vaz, Sofia Ferreira, Lisete Cordeiro, and Ana Querido. 2022. Vulnerability through the Eyes of People Attended by a Portuguese Community-Based Association: A Thematic Analysis. Healthcare 10: 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Rhonda, Pamela Martin, and Bianca Guzman. 2022a. COVID-19 and vulnerable populations. Journal of Community Psychology 50: 2537–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, Sophie, Karen Willis, Marie Bismark, and Natasha Smallwood. 2022b. A time for self-care? Frontline health workers’ strategies for managing mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. SSM Mental Health 2: 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindgren, Britt-Marie, Berit Lundman, and Ulla Graneheim. 2020. Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. International Journal of Nursing Studies 108: 103632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmot, Michael. 2015. The Health Gap. The Challenge of an Unequal World. London: Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezzina, Roberto, Vandana Gopikumar, John Jenkins, Benedetto Saraceno, and Sashidharan. 2022. Social Vulnerability and Mental Health Inequalities in the “Syndemic”: Call for Action. Frontiers in Psychiatry 13: 894370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustaniemi-Laakso, Maija, Mikaela Heikkilä, Eleonora Del Gaudio, Sotiris Konstantis, Maria Nagore Casas, Dolores Morondo, Venkatachala Hegde, and Graham Finlay. 2016. The Protection of Vulnerable Individuals in the Context of EU Policies on Border Checks, Asylum and Immigration. The Protection of Vulnerable Individuals in the Context of EU Policies on Border Checks, Asylum and Immigration Work Package No. 11—Deliverable No. 3. Large-Scale FP7 Collaborative Project GA. Available online: https://www.fp7-frame.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Deliverable-11.3.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Peroni, Lourdes, and Alexandra Timmer. 2013. Vulnerable Groups: The Promise of an Emerging Concept in European Human Rights Convention Law. International Journal of Constitutional Law 11: 1056–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, Bridget. 2019. Inclusion of Marginalized Groups and Communities in Global Health Research Priority-Setting. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics: An International Journal 14: 169–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proag, Virendra. 2014. The concept of vulnerability and resilience. Procedia Economics and Finance 18: 369–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendtorff, Jacob Dahl. 2002. Basic ethical principles in European bioethics and biolaw: Autonomy, dignity, integrity and vulnerability—Towards a foundation of bioethics and biolaw. Medicine Health Care & Philosophy 5: 235–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, Ana Isabel, Ludivine Launay, Elodie Guillaume, Guy Launoy, and Henrique Barros. 2018. The Portuguese version of the European Deprivation Index: Development and association with all-cause mortality. PLoS ONE 13: e0208320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, Lauralie, John Furler, Konstancja Densley, Jeannie Haggerty, Russell Grant, Jean-Frederic Levesque, and Jane Gunn. 2016. Equity of access to primary healthcare for vulnerable populations: The IMPACT international online survey of innovations. International Journal for Equity in Health 15: 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Fernández, María, Rocío Ortiz-Amo, Elena Andina-Díaz, Isabel Fernández-Medina, José Hernández-Padilla, Cayetano Fernández-Sola, and Ángela Ortega-Galán. 2021. Emotions, Feelings, and Experiences of Social Workers While Attending to Vulnerable Groups: A Qualitative Approach. Healthcare 9: 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, Juliano Beck, Caroline de Abreu Prola, Aline Cardoso Siqueira, and Caroline Rubin Rossato Pereira. 2018. O conceito de vulnerabilidade social no âmbito da psicologia no Brasil: Uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Psicologia em Revista 24: 600–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Leiyue, and Gregory Stevens. 2005. Vulnerability and unmet health care needs. The influence of multiple risk factors. Journal of General Internal Medicine 20: 148–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, Stephanie. 2013. Protecting and respecting the vulnerable: Existing regulations or further protections? Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics 34: 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, Francisclê Neri, and Dayse Neri de Souza. 2021. Sete etapas essenciais (subtarefas transversais) para Análise Qualitativa de Dados com Integração do Software webQDA. Available online: https://www.webqda.net/sete-etapas-essenciais-subtarefas-transversais-para-analise-qualitativa-de-dados-com-integracao-do-software-webqda/ (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Symonds, Jon, Caroline Milles, Mike Steel, Sue Porter, and Val Williams. 2019. Making person-centred assessments. Journal of Social Work 20: 431–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Have, Henk. 2014. The principle of vulnerability in the UNESCO declaration on bioethics and human rights: Religious perspectives on human vulnerability in bioethics: Advancing global bioethics. In Religious Perspectives on Human Vulnerability in Bioethics: Advancing Global Bioethics. Edited by Joseph Tham, Alberto Garcia and Gonzalo Miranda. Dordrecht: Springer, vol. 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Have, Henk, and Bert Gordijn. 2021. Vulnerability in light of the COVID-19 crisis. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 24: 153–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolley, Elizabeth, Priscilla R. Ulin, Natasha Mack, Elizabeth T. Robinson, and Stacey M. Succop. 2005. Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Alison, Peter Sainsbury, and Jonathan Craig. 2007. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 19: 349–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 2021. Engineering for sustainable development: Delivering on the Sustainable Development Goals. International Centre for Engineering Education under the Auspices of UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000375644.locale=en (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- United Nations. 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Virokannas, Elina, Suvi Liuski, and Marjo Kuronen. 2018. The contested concept of vulnerability—A literature review. European Journal of Social Work 23: 327–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. 2021. COVID-19 and the Social Determinants of Health and Health Equity: Evidence Brief. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1389412/retrieve (accessed on 10 June 2023).

| Participant | Age (Years) | Sex | Professional Activity in InPulsar |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | Female | 9 months |

| 2 | 46 | Female | 2 years |

| 3 | 42 | Female | 11 years |

| 4 | 27 | Female | 1.5 years |

| 5 | 40 | Female | 7 years |

| 6 | 28 | Male | 6 years |

| 7 | 30 | Female | 2 years |

| 8 | 58 | Male | 5 years |

| 9 | 22 | Female | 2 years |

| 10 | 44 | Female | 4 years |

| 11 | 38 | Female | 10 years |

| 12 | 44 | Female | 1.5 years |

| 13 | 44 | Female | 4 years and 3 months |

| 14 | 30 | Female | 3 years and 2 months |

| 15 | 32 | Female | 7 years |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Laranjeira, C.; Coelho, C.; Ferreira, C.; Pereira, M.; Ribeiro, M.I.; Cordeiro, L.; Querido, A. How Do Professionals Regard Vulnerable People in a Portuguese Community Setting? A Qualitative Content Analysis. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 499. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090499

Laranjeira C, Coelho C, Ferreira C, Pereira M, Ribeiro MI, Cordeiro L, Querido A. How Do Professionals Regard Vulnerable People in a Portuguese Community Setting? A Qualitative Content Analysis. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(9):499. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090499

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaranjeira, Carlos, Catarina Coelho, Catarina Ferreira, Margarida Pereira, Maria Inês Ribeiro, Lisete Cordeiro, and Ana Querido. 2023. "How Do Professionals Regard Vulnerable People in a Portuguese Community Setting? A Qualitative Content Analysis" Social Sciences 12, no. 9: 499. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090499

APA StyleLaranjeira, C., Coelho, C., Ferreira, C., Pereira, M., Ribeiro, M. I., Cordeiro, L., & Querido, A. (2023). How Do Professionals Regard Vulnerable People in a Portuguese Community Setting? A Qualitative Content Analysis. Social Sciences, 12(9), 499. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090499