Unlocking the Power of Mentoring: A Comprehensive Guide to Evaluating the Impact of STEM Mentorship Programs for Women

Abstract

:1. Introduction

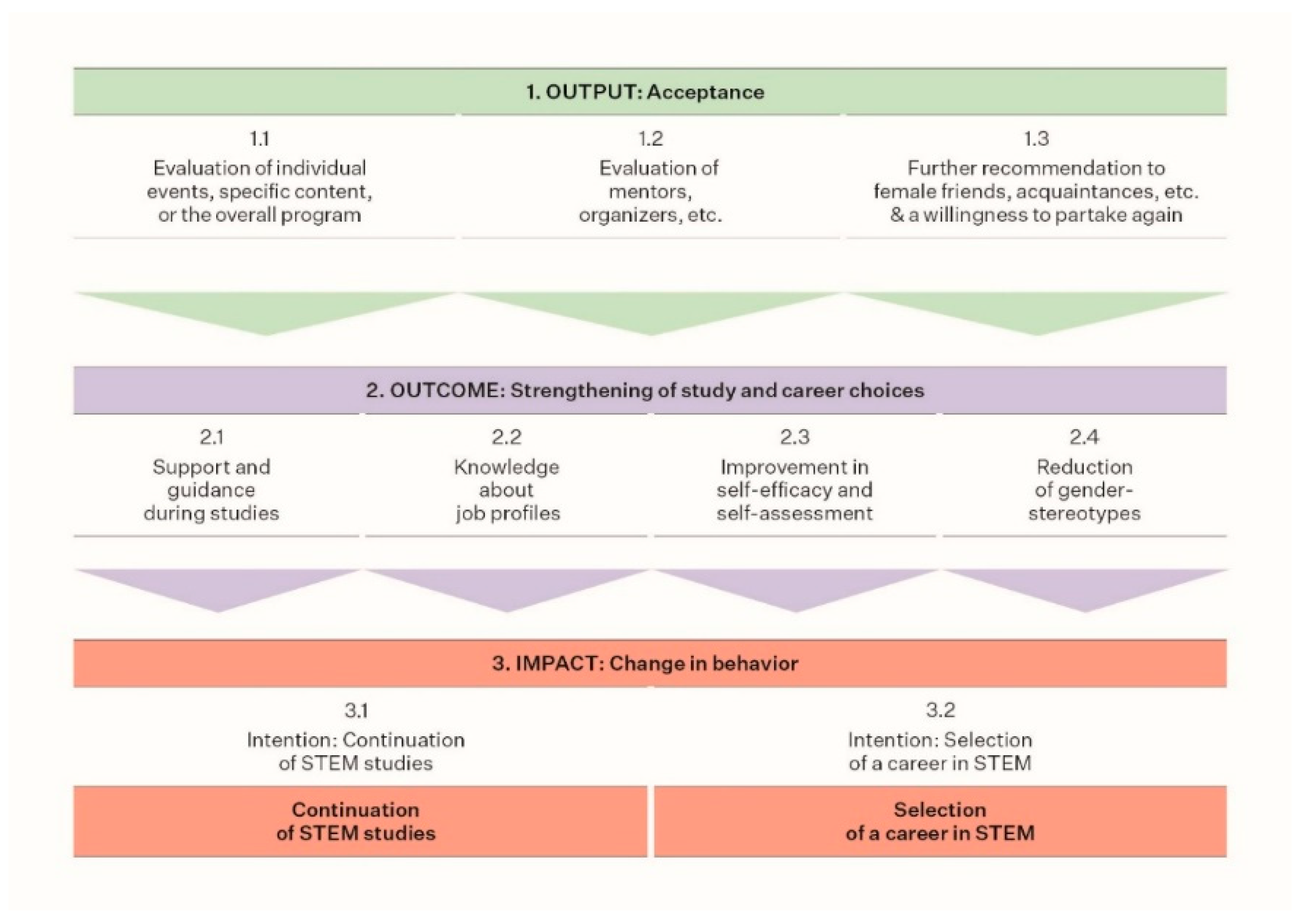

2. The Basic Idea of Our Evaluating Concept for Mentoring Programs

3. The Change Theory of Mentoring Programs of Female STEM Students

3.1. The Output of a Mentoring Program

- Which events of the mentoring program have you attended at least once? (1.1)

- How satisfied are you, with regard to the following organizational aspects? (Online Information, registration process, communication with the program manager, organization of the mentoring program) (1.1)

- How often have you had personal meetings with your mentor? (1.2)

- How satisfied are you with the following aspects of the mentoring relationship?

- (personality and sex of the mentor, professional fit with the mentor, spatial distance to the mentor, commitment of the mentor, discussed topics) (1.2)

- Will you recommend the mentoring program to fellow students? (1.3)

- Can you imagine participating as a mentor in the future? (1.3)

3.2. The Outcome of a Mentoring Program

- Participation in the mentoring program helped me to get … (e.g., motivation for my studies, support for the practical semester/final thesis, access to networks, to know my strengths and weaknesses) (based on Höppel 2016). (2.1 and 2.3)

- How satisfied are you, overall, with your studies? (2.1)

- Are you well-informed about possible jobs you can take up after graduation? (2.2)

- Participation in the mentoring program helped me to get … (e.g., to know role models, insights into the everyday working life of a professional, access to networks, a better idea of the kind of company I want to work in later, a better idea of which professional field I want to work in later, an understanding of the obstacles women face in their careers, information about the ”rules of the game” in companies) (based on Höppel 2016). (2.2)

- If I take up an activity in my professional field, then … (e.g., I can contribute to solving important social problems, I need good social competence, I can combine my job with my own family, I work a lot in a team, …). (2.2)

- How confident are you that you can cope with the demands of your studies? (Fellenberg and Hannover 2006). (2.3)

- After completing my studies, I can imagine … (e.g., leading a project team, mastering negotiating (with men) confidently, working in a male-dominated environment, to have a female supervisor). (2.3 and 2.4)

- Do you agree with the following statements? (2.4)

- Most women know well about ‘…’ (put in a specific STEM field).

- Most men know well about ‘…’ (put in a specific STEM field).

- I can identify well with my field of study. (2.1 and 2.4)

3.3. The Impact of a Mentoring Program

- I am seriously thinking of dropping out of university/my doctorate (Fellenberg and Hannover 2006). (3.1)

- I am seriously thinking of taking up a master’s program after completing my bachelor’s degree. (3.1)

- After completing my studies, I will take up a profession in the STEM field. (3.2)

- In the course of my career, I will take a leadership position. (3.2)

4. The Empirical Evaluation Design

5. Collecting and Interpreting the Data

6. Summary and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Of course, mentoring programs can not only impact participants, but also contribute to structural change within a university or faculty. Although these cultural changes are most valuable to women’s opportunities in STEM, measuring these changes is far more difficult and goes beyond our goal. |

| 2 | The choice of the concrete questions is fundamentally important to gain valid results. Note, however, that the list of questions for the empirical measurement of self-efficacy and stereotypes should always be adapted to the concrete program, the specific target group of the mentoring program, and the cultural context. A universal valid questionnaire for all mentoring programs is not available, though. Herce-Palomares et al. (2022), Luo et al. (2021), and Verdugo-Castro et al. (2022) describe different methodologies to develop and validate instruments to quantify the concepts of self-efficacy and gender stereotypes in the context of STEM professions, and can serve as a blueprint for designing an adequate questionnaire. |

| 3 | The pre-tests within our pilot studies revealed that statements that formulate a very specific and certain intention better capture personal differences in terms of credibility of intention. We therefore followed the example of Fellenberg and Hannover (2006) and formulated very clear statements regarding the future studies and career plans. |

| 4 | This measure requires a matching of before and after responses on an individual level and reveals individual effects that might remain invisible in the group means. |

References

- Ajzen, Icek. 1991. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50: 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, Christopher J., and Mark Conner. 2001. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour. A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology 40: 471–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, Albert. 1997. Self-Efficacy. The Exercise of Control. New York: Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Makini, Jillian Cadwell, Anne Kern, Ke Wu, Maniphone Dickerson, and Melinda Howard. 2021. Critical feminist analysis of STEM mentoring programs: A meta-synthesis of the existing literature. Gender, Work & Organization 29: 167–87. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, Heidi. 2017. The Status of Women in STEM in Higher Education: A Review of the Literature 2007–2017. Science & Technology Libraries 36: 235–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bong, Mimi, and Einar M. Skaalvik. 2003. Academic self-concept and self-efficacy: How different are they really? Educational Psychology Review 15: 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenning, Stefanie, and Elke Wolf. 2022. MINT-Mentoring zwischen Breiten- und Elitenförderung: Eine Diskussion anhand der Karriereorientierung und -einstellungen von Mentees und anderen Studierenden. In Geschlechtergerechtigkeit und MINT: Irritationen, Ambivalenzen und Widersprüche in Geschlechterdiskursen an Hochschulen. Edited by Clarissa Rudolph, Sophia Dollsack and Anne Reber. Leverkusen: Verlag Barbara Budrich, pp. 129–48. [Google Scholar]

- Byars-Winston, Angela M., Janet Branchaw, Christine Pfund, Patrice Leverett, and Joseph Newton. 2015. Culturally diverse undergraduate researchers’ academic outcomes and perceptions of their research mentoring relationships. International Journal of Science Education 37: 2533–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callies, Nathalie, and Elke Breuer. 2010. Going Diverse 2009: Innovative Answers to Future Challenges. Bericht über die internationale Abschlusskonferenz des EU-Projektes TANDEMplusIDEA zu Gender und Diversity in Wissenschaft und Wirtschaft am 29.-30. Oktober 2009. Journal Netzwerk Frauenforschung 26: 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright, Nancy. 2007. Hunting Causes and Using Them. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheryan, Sapna, Allison Master, and Andrew N. Meltzoff. 2015. Cultural stereotypes as gatekeepers: Increasing girls’ interest in computer science and engineering by diversifying stereotypes. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbjørnsen, Tom. 2003. Der Hawthorne-Effekt oder die Human-Relations-Theorie. Über die experimentelle Situation und ihren Einfluss. In Theorien und Methoden in den Sozialwissenschaften. Edited by Stein Ugelvik Larsen and Ekkart Zimmermann. Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag, pp. 131–43. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Thomas D. 2007. Describing what is special about the role of experiments in contemporary educational research: Putting the “gold standard” rhetoric into perspective. Journal of Multidisciplinary Evaluation 3: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, Shelley J. 2001. Gender and the Career Choice Process. The Role of Biased Self-Assessments. American Journal of Sociology 10: 1691–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, Shelley J. 2004. Constraints into Preferences. Gender, Status, and Emerging Career Aspirations. American Sociological Review 69: 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, Angus, and Nancy Cartwright. 2018. Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials. Social Science and Medicine 210: 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennehy, Tara C., and Nilanjana Dasgupta. 2017. Female peer mentors early in college increase women’s positive academic experiences and retention in engineering. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114: 5964–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derboven, Wibke, and Gabriele Winker. 2010. Tausend Formeln und dahinter keine Welt. Eine geschlechtersensitive Studie zum Studien-abbruch in den Ingenieurwissenschaften. Beiträge zur Hochschulforschung 32: 56–78. [Google Scholar]

- Diekman, Amanda B., Elisabeth R. Brown, Amanda M. Johnston, and Emily K. Clark. 2010. Seeking congruity between goals and roles: A new look at why women opt out of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics careers. Psychological Science 21: 1051–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, Andreas. 2012. Empirische Sozialforschung. Grundlagen, Methoden, Anwendungen. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Döring, Nicola, and Jürgen Bortz. 2016. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation in den Sozial- und Humanwissenschaften. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Duflo, Esther, Rachel Glennerster, and Michael Kremer. 2007. Using randomization in development economics research. A toolkit. In Discussion Paper Nr. 6059. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, Jacquelynne S. 2005. Subjective task value and the Eccles et al. model of achievement-related choices. In Handbook of Competence and Motivation. Edited by Andrew J. Elliot and Carol S. Dweck. New York: Guilford Press, pp. 105–21. [Google Scholar]

- Edzie, Rosemary L. 2014. Exploring the Factors that Influence and Motivate Female Students to Enroll and Persist in Collegiate STEM Degree Programs: A Mixed Methods study. Ph.D. thesis, The University of Nebraska—Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ertl, Bernhard, Silke Luttenberger, and Manuela Paechter. 2014. Stereotype als Einflussfaktoren auf die Motivation und die Einschätzung der eigenen Fähigkeiten bei Studentinnen in MINT-Fächern. Gruppendynamik und Organisationsberatung 45: 419–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellenberg, Franziska, and Bettina Hannover. 2006. Kaum begonnen, schon zerronnen? Psychologische Ursachenfaktoren für die Neigung von Studienanfängern, das Studium abzubrechen oder das Fach zu wechseln. Empirische Pädagogik 20: 381–99. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger, Leon. 1957. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Findeisen, Ina. 2006. Evaluation 2005. Mentoring-Programm. Konstanz: Universität Konstanz, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Vanessa, Maik Walpuski, Martin Lang, Melanie Letzner, Sabine Manzel, Patrick Motté, Bianca Paczulla, Elke Sumfleth, and Detlev Leutner. 2020. Was beeinflusst die Entscheidung zum Studienabbruch? Längsschnittliche Analysen zum Zusammenspiel von Studienzufriedenheit, Fachwissen und Abbruchintention in den Fächern Chemie, Ingenieur- und Sozialwissenschaften. Zeitschrift für empirische Hochschulforschung 1: 55–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer, Jens, Detlev Leutner, Matthias Brand, and Hans E. Fischer. 2019. Vorhersage des Studienabbruchs in naturwissenschaftlich-technischen Studienfächern. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaften 22: 1077–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, Emily, and Lisa Dyson. 2017. Implications of the Changing Conversation About Causality for Evaluators. American Journal of Evaluation 38: 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Anne-Francoise. 2008. Sind technische Fachkulturen männlich geprägt? Hi-Tech, Das Magazin der Berner Fachhochschule Technik und Informatik 2: 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Glick, Peter, and Susan T. Fiske. 1999. Sexism and other “isms”: Independence, status, and the ambivalent content of stereotypes. In Sexism and Stereotypes in Modern Society: The Gender Science of Janet Taylor Spence. Edited by William B. Swann Jr., Judith H. Langlois and Lucia Albino Gilbert. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 193–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Pérez, Susana, Ruth Mateos de Cabo, and Milagros Sáinz. 2020. Girls in STEM: Is It a Female Role-Model Thing? Frontiers in Psychology 11: 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herce-Palomares, Maria Pilar, Carmen Botella Mascarell, Esther de Ves, Emilia López-Inesta, Anabel Forte, Xaro Benavent, and Silvia Rueda. 2022. On the Design and Validation of Assessing Tools for Measuring the Ompact of Programs Promoting STEM Vocations. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 937058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, Paul R. 2018. Landscape of Assessments of Mentoring Relationship Processes in Postsecondary STEMM Contexts: A Synthesis of Validity Evidence from Mentee, Mentor, Institutional/Programmatic Perspectives. Commissioned paper prepared for the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Committee on the Science of Effective Mentoring in Science, Technology, Engineering, Medicine, and Mathematics (STEMM) 10: 24918. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, Paul R., Brittany Bloodhart, Rebecca T. Barnes, Amanda S. Adams, Sandra M. Clinton, Ilana Pollack, Elaine Godfrey, Melissa Burt, and Emily V. Fischer. 2017. Promoting professional identity, motivation, and persistence: Benefits of an informal mentoring program for female undergraduate students. PLoS ONE 12: e0187531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessisches Koordinationsbüro des MentorinnenNetzwerks. 2010. Mentoring Wirkt! Evaluation des MentorinnenNetzwerks für Frauen in Naturwissenschaft und Technik, Frankfurt. Frankfurt: Hessisches Koordinationsbüro des MentorinnenNetzwerks. [Google Scholar]

- Heublein, Ulrich, Christopher Hutzsch, Jochen Schreiber, Dieter Sommer, and Georg Besuch. 2010. Ursachen des Studienabbruchs in Bachelor- und in herkömmlichen Studiengängen. Ergebnisse einer bundesweiten Befragung von Exmatrikulierten des Studienjahren 2007/08. Projektbericht. Hannover: HIS. [Google Scholar]

- Höppel, Dagmar. 2016. Aufwind mit Mentoring. Wirksamkeit von Mentoring-Projekten zur Karriereförderungen von Frauen in der Wissenschaft. Baden-Baden: Nomos. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Roxanne. 2014. The evolution of the chilly climate for women in science. In Girls and Women in STEM: A Never Ending Story. Edited by Janice Koch, Barbara Polnick and Beverly Irby. Charlotte: IAP, pp. 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ihsen, Susanne, and Antje Ducki. 2012. Gender Toolbox. Berlin: Gender und Technik Zentrum (GuTZ) der Beuth Hochschule für Technik Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- Ihsen, Susanne. 2006. Von der homogenen technischen Fachkultur zu Mixed Teams—Gender –Diversity. In Hochschuldidaktik und Fachkulturen. Gender als didaktisches Prinzip. Edited by Anne Dudeck and Bettina Jansen-Schulz. Bielefeld: UVW, Webler, pp. 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ihsen, Susanne. 2010. Technikkultur im Wandel: Ergebnisse der Geschlechterforschung in Technischen Universitäten. Beiträge zur Hochschulforschung 32: 80–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kalpazidou Schmidt, Evanthia, Susanne Bührer, Martina Schraudner, Sybille Reidl, Jörg Müller, Rachel Palmén, Sanne Haase, Ebbe K. Graversen, Florian Holzinger, Clemens Striebing, and et al. 2017. A Conceptual Evaluation Framework for Promoting Gender Equality in Research and Innovation. Toolbox I—A Synthesis Report. Stuttgart: Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft. [Google Scholar]

- Kessels, Ursula, and Bettina Hannover. 2006. Zum Einfluss des Image von mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Schulfächern auf die schulische Interessenentwicklung. In Untersuchungen zur Bildungsqualität von Schule. Abschlussbericht des DFG-Schwerpunktprogramms. Edited by Manfred Prenzel and Lars Allolio-Näcke. Münster: Waxmann, pp. 350–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kessels, Ursula. 2015. Bridging the gap by enhancing the fit: How stereotypes about STEM clash with stereotypes about girls. International Journal of Gender, Science and Technology 7: 280–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Min-sun, and John E. Hunter. 1993. Relationships among attitudes, behavioral intentions, and behavior. A meta-analysis of past research, part 2. Communication Research 20: 331–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, Isabelle. 2020. Evaluating STEM Gender Equity Programs. A Guide to Effective Program Evaluation. Office of the Women in STEM Ambassador. Available online: https://womeninstem.org.au/national-evaluation-guide (accessed on 9 July 2023).

- Kosuch, Renate. 2006. Modifikation des Studienwahlverhaltens nach dem Konzept der Selbstwirksamkeit—Ergebnisse zur Verbreitung und Effektivität der «Sommerhochschule» in Naturwissenschaft und Technik für Schülerinnen. In Hochschulinnovation. Gender-Initiativen in der Technik. Gender Studies in den Angewandten Wissenschaften 3. Edited by Carmen Gransee. Hamburg: LIT, pp. 115–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Jennifer A. 2008. Gender Equity Issues in Technology Education: A Qualitative Approach Touncovering the Barriers. Raleigh: North Carolina State University. [Google Scholar]

- Leicht-Scholten, Carmen, and Henrike Wolf. 2009. Vergleichende Evaluation von Mentoring-Programmen für High Potentials mit disziplinärem Schwerpunkt. In Mentoring: Theoretische Hintergründe, empirische Befunde und praktische Anwendungen. Edited by Heidrun Stöger, Elisabeth Ziegler and Diana Schimke. Lengerich/Westfalen: Pabst Science Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, Robert W., Steven D. Brown, and Gail Hackett. 1994. Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior 45: 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, Cornelia, Sabine Mellies, and Barbara Schwarze. 2008. Frauen in der technischen Bildung—Die Top-Ressource für die Zukunft. In Technische Bildung für Alle. Ein vernachlässigtes Schlüsselelement der Innovationspolitik. Berlin: VDI iit, pp. 257–327. [Google Scholar]

- Löther, Andrea, and Jana Girlich. 2011. Frauen in MINT-Fächern: Bilanzierung der Aktivitäten im hochschulischen Bereich. Materialien der Gemeinsamen Wissenschaftskonferenz 21. Bonn: Gemeinsame Wissenschaftskonferenz. [Google Scholar]

- Löther, Andrea, Nina Steinweg, Anke Lipinsky, and Hanna Meyer. 2021. Wie gut die Maßnahmen zur Gleichstellung wirken. Forschung und Lehre 28: 3. [Google Scholar]

- Löther, Andrea. 2019. Is It Working? An Impact Evaluation of the German “Women Professors Program”. Social Sciences 8: 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Tian, Winnie Wing Mui So, Wai Chin Li, and Jianxin Yao. 2021. The Development and Validation of a Survey for Evaluating Primary Students’ Self-efficacy in STEM Activities. Journal of Science Education and Technology 30: 408–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPhee, David, Samantha Farro, and Silvia Sara Canetto. 2013. Academic Self-Efficacy and Performance of Underrepresented STEM Majors: Gender, Ethnic, and Social Class Patterns. Analysis of Social Issues and Public Policy 13: 347–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Master, Allison. 2021. Gender Stereotypes Influence Children’s STEM Motivation. Children Development Perspectives 15: 203–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinefeld, Werner. 1999. Studienabbruch an der technischen Fakultät der Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg. In Studienerfolg und Studienabbruch. Beiträge aus Forschung und Praxis. Edited by Manuela Schröder-Gronostay and Hans-Dieter Daniel. Neuwied: Luchterhand Verlag, pp. 181–93. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, Thomas, Markus Diem, Remy Droz, Francoise Galley, and Urs Kiener. 1999. Hochschule –Studium—Studienabbruch. Synthesebericht zum Forschungsprojekt “Studienabbruch an schweizerischen Hochschulen als Spiegel von Funktionslogiken”. In Nationales Forschungsprogramm 33. Zürich: Rüegger. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, David I., Kyle M. Nolla, Alice H. Eagly, and David H. Uttal. 2018. The Development of Children’s Gender-Science Stereotypes: A Meta-analysis of 5 Decades of U.S. Draw-A-Scientist Studies. Child Development 89: 1943–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, Kathi N., Samantha C. January, Kelly K. Dray, and Adrienne R. Carter-Sowell. 2019. Is it always this cold? Chilly interpersonal climates as a barrier to the well-being of early-career women faculty in STEM. Equality Diversity and Inclusion 38: 226–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minks, Karl-Heinz. 2004. Wo ist der Ingenieurnachwuchs? In HIS Kurzinformation A54. Hannover: HIS-Hochschul -Informations-System GmbH, pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, Christoph E., and Maria Albrecht. 2016. The Future of Impact Evaluation is Rigorous and Theory-Driven. In The Future of Evaluation. Global Trends, New Challenges, Shared Perspectives. Edited by Reinhard Stockmann and Wolfgang Meyer. New York: Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 283–93. [Google Scholar]

- National Academy of Science, Engineering and Medicine. 2019. The science of effective mentorship in STEMM, Online Guide V1.0. Available online: https://www.nap.edu/resource/25568/interactive/ (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- National Center for Women & Information Technology. 2011. Evaluating a Mentoring Program. Guide. Boulder: National Center for Women & Information Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Nationales MINT Forum. 2018. Wirkungsvolle Arbeit außerschulischer MINT-Initiativen. Ein praktischer Leitfaden zur Selbstanalyse: Nationales MINT Forum e. V. Berlin: Nationales MINT Forum e. V. [Google Scholar]

- Nickolaus, Reinhold, and Svitlana Mokhonko. 2016. In 5 Schritten zum Zielführenden Evaluationsdesign, Eine Handreichung für Bildungsinitiativen im MINT-Bereich. München: Acatech–Deutsche Akademie für Technikwissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Palmén, Rahel, and Evanthia Kalpazidou Schmidt. 2019. Analysing facilitating and hindering factors for implementing gender equality interventions in R&I: Structures and processes. Evaluation and Program Planning 77: 101726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulitz, Tanja. 2014. Fach und Geschlecht. Neue Perspektiven auf technik- und naturwissenschaftliche Wissenskulturen. In Vielfalt der Informatik: Ein Beitrag zu Selbstverständnis und Außenwirkung. Edited by Anja Zeising, Claude Draude Heide Schelhowe and Susanne Maaß. Bremen: Universität Bremen, pp. 95–105. [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, Charlotte R., Derek Heim, Andrew R. Levy, and Derek T. Larkin. 2016. Twenty Years of Stereotype Threat Research: A Review of Psychological Mediators. PLoS ONE 11: e0146487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, Renate, Mechthild Budde, Pia Simone Brocke, Gitta Doebert, Helga Rudack, and Henrike Wolf. 2017. Praxishandbuch Mentoring in der Wissenschaft. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohlenz, Philipp, and Karen Tinsner. 2004. Bestimmungsgrößen des Studienabbruchs—Eine empirische Untersuchung zu Ursachen und Verantwortlichkeiten. Servicestelle für Lehrevaluation an der Universität Potsdam. Potsdam: Universitätsverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, Donna M., and James A. Wolff. 1994. The time interval in the intention-behaviour relationship. Meta-analysis. British Journal of Social Psychology 33: 405–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea, Jessica N. 2015. See Your Way to Success: Imagery Perspective Influences Performance Understereotype Threat. Ph.D. thesis, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, Jackie, Erica Smith, Nansiri Iamsuk, and Jennifer Miller. 2016. Balancing the Equation: Mentoring First-Year Female STEM Students at a Regional University. International Journal of Innovation in Science and Mathematics Education 24: 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Reinholz, Daniel L., and Tessa C. Andrews. 2020. Change theheory anf theory of change: What’s the difference anyway? International Journal of STEM Education 7: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scriven, Michael. 2008. A summative evaluation of RCT methodology: & An alternative approach to causalresearch. Journal of Multidisciplinary Evaluation 5: 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Seemann, Maika, and Wenke Gausch. 2012. Studienabbruch und Studienfachwechsel in den mathematisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Bachelorstudiengängen der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. In Schriftenreihe zum Qualitätsmanagement an Hochschulen 6. Berlin: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, Emily S., David M. Marx, and Radmila Prislin. 2013. Mind the gap: Framing of women’s success and representation in STEM affects women’s math performance under threat. Sex Roles 68: 454–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, Jenessa R., Amy M. Williams, and Mariam Hambarchyan. 2013. Are all interventions created equal? A multi-threat approach to tailoring stereotype threat interventions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 104: 277–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, Jenessa R., and Amy M. Williams. 2012. The Role of Stereotype Threats in Undermining Girls’ and Women’s Performance and Interest in STEM Fields. Sex Roles 66: 175–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Jiyun Elizabeth L., Sheri R. Levy, and Bonita London. 2016. Effects of role model exposure on STEM and non-STEM student engagement. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 46: 410–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solga, Heike, and Lisa Pfahl. 2009. Doing Gender im technisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Bereich. In Förderung des Nachwuchses in Technik und Naturwissenschaft. Edited by Joachim Milberg. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 155–218. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, Steven J., Claude M. Steele, and Diane M. Quinn. 1999. Stereotype threat and women’s math performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 35: 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, Melanie C., and Irena D. Ebert. 2016. Berufswahl. In Frauen—Männer—Karrieren. Edited by Melanie C. Steffens and Irena D. Ebert. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 129–39. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, Peter M., Angela Wroblewski, and Thomas D. Cook. 2009. Randomized Experiments and Quasi-Experimental Designs in Educational Research. In The International Handbook of Educational Evaluation. Edited by Katherine E. Ryan and J. Bradley Cousins. Los Angeles: SAGE, pp. 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Stelter, Rebecca L., Janis B. Kupersmidt, and Kathryn N. Stump. 2021. Establishing effective STEM mentoring relationships through mentor training. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1483: 224–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöger, Heidrun, Manuel Hopp, and Albert Ziegler. 2017. Online mentoring as an extracurricular measure to encourage talented girls in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics): An empirical study of one-on-one versus group mentoring. Gifted Child Quarterly 61: 239–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöger, Heidrun, Sigrun Schirner, Lena Laemmle, Stephanie Obergriesser, Michael Heileman, and Albert Ziegler. 2016. A contextual perspective on talented female participants and their development in extracurricular STEM programs. Annals of New York Academy of Science 1377: 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöger, Heidrun, Xiaoju Duan, Sigrun Schirner, Teresa Greindl, and Albert Ziegler. 2013. The effectiveness of a one-year online mentoring program for girls in STEM. Computers & Education 69: 408–18. [Google Scholar]

- Stout, Jane G., Nilanjana Dasgupta, Matthew Hunsinger, and Melissa A. McManus. 2011. STEMing the tide: Using ingroup experts to inoculate women’s self-concept in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 100: 255–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strayhorn, Terrell Lammont. 2012. College Students’ Sense of Belonging: A Key to Educational Success for All Students. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Rong, and James Rounds. 2015. All STEM fields are not created equal: People and things interests explain gender disparities across STEM fields. Frontiers in Psychology 25: 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thébaud, Sarah, and Maria Charles. 2018. Segregation, stereotypes, and STEM. Social Sciences 7: 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdugo-Castro, Sonia, M. Cruz Sánchez-Gómez, and Aicia Garcia-Holgado. 2022. University students’ view regarding gender in STEM studies: Design and validation of an instrument. Education and Information Technologies 27: 12301–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinhardt, Felix. 2017. Ursache für Frauenmangel in MINT-Berufen? Mädchen unterschätzen schon in der fünften Klasse ihre Fähigkeiten in Mathematik. DIW Wochenbericht 84: 1009–14. [Google Scholar]

- W.K. Kellogg Foundation. 2004. Logic Model Development Guide. Battle Creek: W.K. Kellogg Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, Elke, and Stefanie Brenning. 2019. What works? Eine Meta-Analyse von Evaluationen von MINT-Projekten für Schülerinnen und Studentinnen, Hochschule München. Available online: https://www.oth-regensburg.de/en/faculties/social-and-health-care-sciences/mint-strategien-40.html (accessed on 19 February 2020).

- Wolf, Elke, and Stefanie Brenning. 2021a. Wirkung messen. Handbuch zur Evaluation von MINT-Projekten für Schülerinnen. München: Hochschule München. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, Elke, and Stefanie Brenning. 2021b. Wirkung messen. Handbuch zur Evaluation von Mentoring-Programmen für MINT-Studentinnen. München: Hochschule München. [Google Scholar]

- Wooldridge, Jeffrey. 2013. Introductory Econometrics: A Modern Approach. Mason: Nelson Education. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Forum. 2019. Global Gender Gap Report 2020. Cologny: WEF. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wolf, E.; Brenning, S. Unlocking the Power of Mentoring: A Comprehensive Guide to Evaluating the Impact of STEM Mentorship Programs for Women. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090508

Wolf E, Brenning S. Unlocking the Power of Mentoring: A Comprehensive Guide to Evaluating the Impact of STEM Mentorship Programs for Women. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(9):508. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090508

Chicago/Turabian StyleWolf, Elke, and Stefanie Brenning. 2023. "Unlocking the Power of Mentoring: A Comprehensive Guide to Evaluating the Impact of STEM Mentorship Programs for Women" Social Sciences 12, no. 9: 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090508

APA StyleWolf, E., & Brenning, S. (2023). Unlocking the Power of Mentoring: A Comprehensive Guide to Evaluating the Impact of STEM Mentorship Programs for Women. Social Sciences, 12(9), 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090508