College Students and Environmental Disasters: A Review of the Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

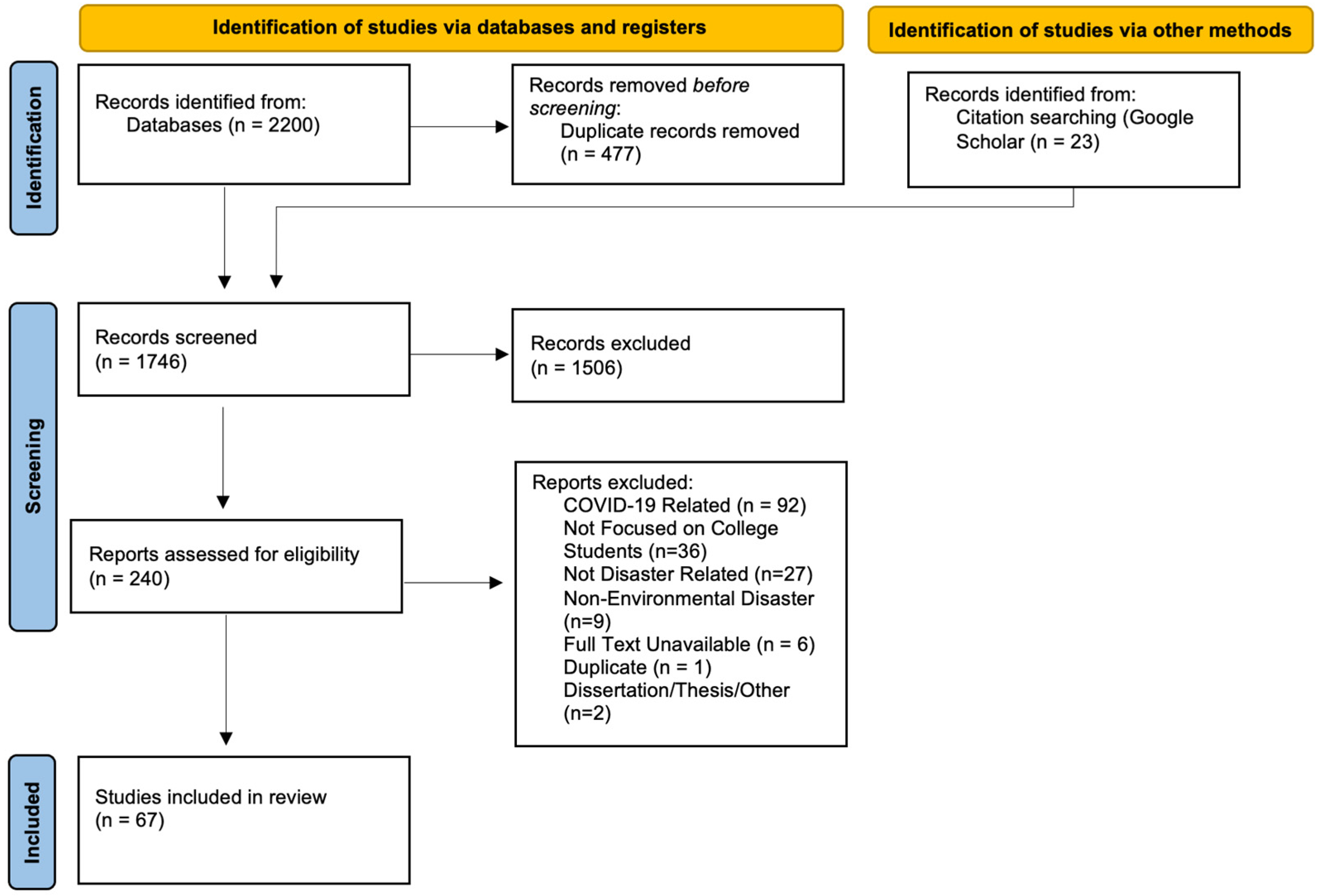

2.1. Phase One: Data Collection and Curation

2.2. Phase Two: Screening and Extraction

2.3. Phase Three: Data Analysis

3. Results

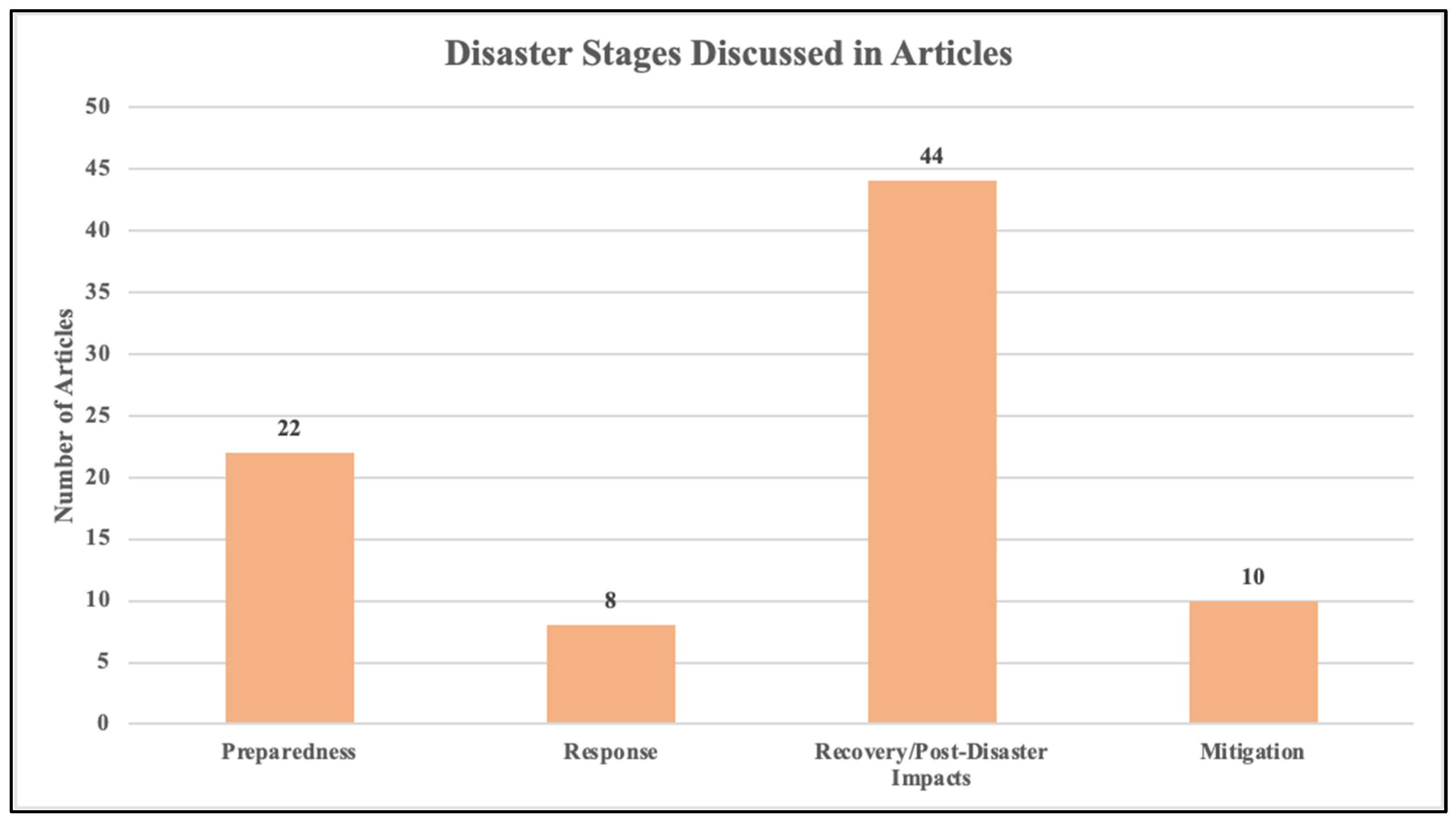

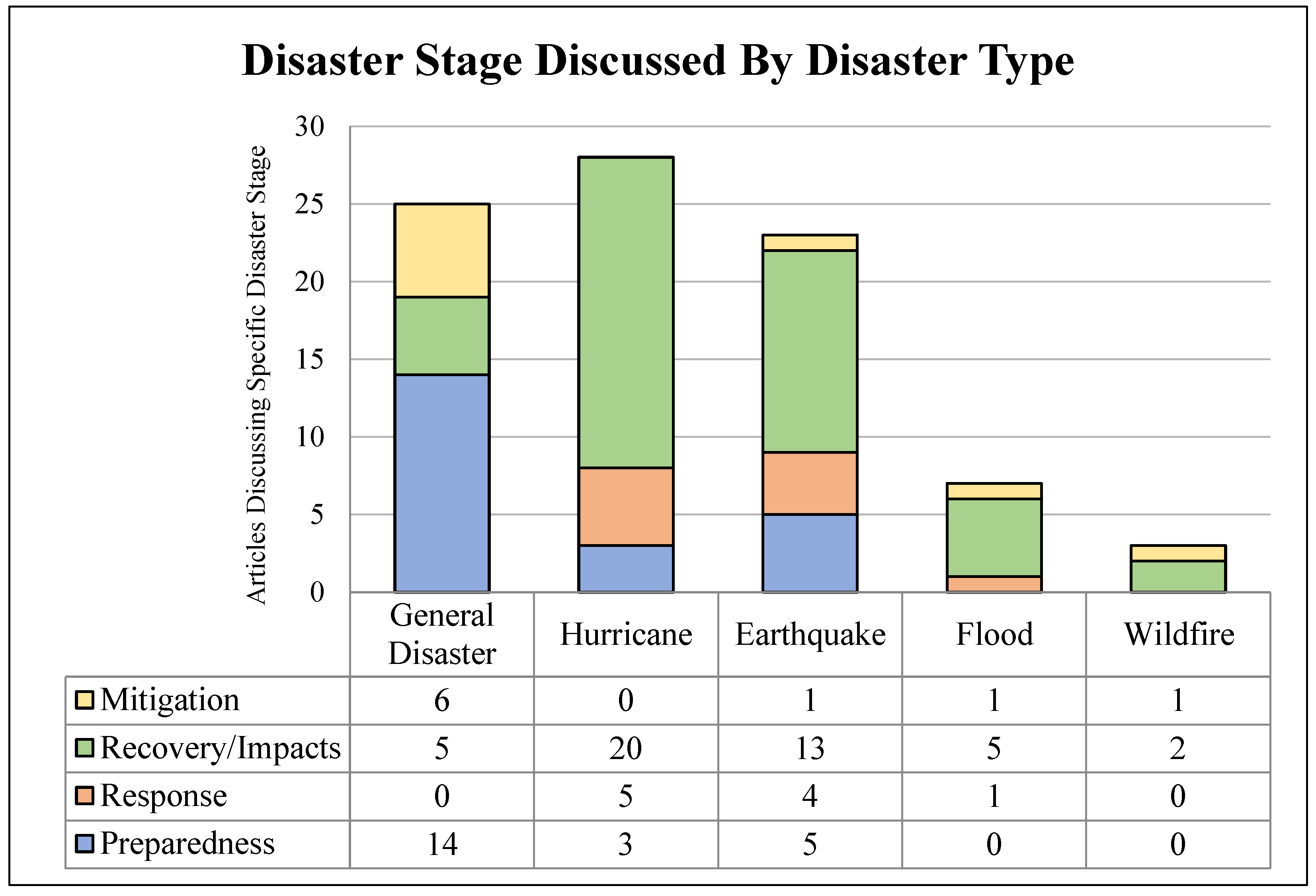

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

3.2. Qualitative Analysis

3.2.1. College Students’ Disaster Preparedness and Literacy

3.2.2. Enhancing Disaster Preparedness Education in Higher Education

3.2.3. Disaster Impacts to the Health, Wellbeing, and Education of College Students

Health and Wellbeing Impacts

Educational and Academic Impacts

4. Discussion

5. Future Research Directions

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abrams, Zara. 2022. Monitor on Psychology 53. Available online: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2022/10/mental-health-campus-care (accessed on 29 September 2023).

- Abukhalaf, Amer Hamad Issa, Jason von Meding, Jake R. Dooling, and Deyaaldeen M. Abusal. 2022. Assessing international students’ vulnerability to hurricanes: University of Florida case study. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 71: 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksa, Furqan I., Sugeng Utaya, Syamsul Bachri, and Budi Handoyo. 2020. The role of knowledge and fatalism in college students related to the earthquake-risk perception. Jàmbá: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies 12: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, David, Phoebe Prioleau, Kanako Taku, Yu Naruse, Hideharu Sekine, Masaharu Maeda, Hirooki Yabe, Craig Katz, and Robert Yanagisawa. 2016. Post-traumatic stress and growth among medical student volunteers after the March 2011 disaster in Fukushima, Japan: Implications for student involvement with future disasters. Psychiatric Quarterly 87: 241–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, Bilal Ahmad, Sidrat-Ul-Muntaha Anees, S. N. Z. Geelani, Nusrat, Irfana Jan, and Bisma Ashraf Zargar. 2017. A Study on Disaster Awareness and Preparedness among College Students $n District Ganderbal of Kashmir Valley. International Journal for Science and Advance Research in Technology (IJSART) 3: 156–59. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchini, V., R. Roncone, L. Giusti, M. Casacchia, M. G. Cifone, and R. Pollice. 2015. PTSD growth and substance abuse among a college student community: Coping strategies after 2009 L’Aquila earthquake. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health 11: 140–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breen, Kyle. 2022. Disaster racism: Using Black sociology, critical race theory and history to understand racial disparity to disaster in the United States. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 31: 229–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, Kyle, and Michelle Meyer. 2021. Staying above water: Educational outcomes of college students during the 2016 Louisiana flood. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters 39: 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, Kyle, Meredith Greig, and Haorui Wu. 2023. Learning green social work in global disaster contexts: A case study approach. Social Sciences 12: 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carales, Vincent D., and Ruth M. Lopez. 2022. Navigating college after a disaster: Understanding the impact and institutional support for community college students after Hurricane Harvey. Community College Journal of Research and Practice 46: 145–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlton, Sally, and Colleen E. Mills. 2017. The Student Volunteer Army: A ‘repeat emergent’ emergency response organisation. Disasters 41: 764–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlton, Sally, Sylvia Nissen, Jennifer H. K. Wong, and Sam Johnson. 2022. “A shovel or a shopping cart”: Lessons from ten years of disaster response by a student-led volunteer group. Natural Hazards 111: 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmutina, Ksenia, and Jason von Meding. 2019. A dilemma of language: “Natural disasters” in academic literature. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 10: 283–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmutina, Ksenia, Jason von Meding, J. C. Gaillard, and Lee Bosher. 2017. Why Natural Disasters Aren’t All That Natural. OpenDemocracy, September 14. Available online: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/why-natural-disasters-arent-all-that-natural/ (accessed on 14 October 2023).

- Choudhury, Mahed, and Haorui Wu. 2023. Disaster education in the context of post-secondary education: A systematic literature review. Natural Hazards Review 24: 3. Available online: https://ascelibrary.org/doi/10.1061/NHREFO.NHENG-1778 (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Collings, David A., Juliet A. Gerrard, and Ashley Garrill. 2019. Shaking up biology—Our experiences teaching cell biology and biochemistry to a first year undergraduate class through the Canterbury (New Zealand) Earthquakes. Journal of Biological Education 53: 236–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, David, Ashley Garrill, and Lucy Johnston. 2018. Student application for special consideration for examination performance following a natural disaster. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 43: 260–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congressional Research Service. 2023. Wildfire Statistics. Available online: https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/IF10244.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Contreras, Rosario Clarabel C. 2014. Assessment of environmental literacy, concern and disaster preparedness among college students. Asia Pacific Journal of Multidisciplinary Research 2: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Covidence. n.d. Available online: https://www.covidence.org (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Di Pietro, Giorgio. 2018. The academic impact of natural disasters: Evidence from L’Aquila earthquake. Education Economics 26: 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, Matthew D., Brian Lockwood, and John G. Comiskey. 2017. Superstorm Sandy and the academic achievement of university students. Disasters 41: 748–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekuase-Anwansedo, Ajayi, Jose Noguera, and Brandon Dumas. 2017. Transitioning from Blackboard to Moodle amidst natural disaster: Faculty and students perceptions. Paper presented at 2017 ACM SIGUCCS Annual Conference, Seattle, WA, USA, October 1–14; Part F131713. pp. 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadilah, Muhyiatul, Anna Permanasari, Riandi, and Enok Maryani. 2020. The level of disaster literacy of earthquake-experienced students in mathematics and science faculty of state university in Indonesia. Journal of Engineering Science and Technology (JESTEC) 14: 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, Kevin M., and Matthew L. Spialek. 2021. Review of Hurricane Harvey’s Aftermath: Place, Race, and Inequality in Disaster Recovery. Social Forces 100: e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, Leo, Vanessa Raditz, and Michael Méndez. 2022. Queer and present danger: Understanding the disparate impacts of disasters on LGBTQ+ communities. Disasters 46: 946–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon-Hollingsworth, Arlene T., Julia E. Thompson, Meghan A. Geary, Mark A. Schexnaildre, Betty S. Lai, and Mary Lou Kelley. 2016. Social support questionnaire for children: Development and initial validation. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development 49: 122–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouramanis, Chris, and Carlos Alberto Morales Ramirez. 2021. Deep understanding of natural hazards based on the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction in a higher education geography module in Singapore. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 30: 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, Alex, Hao-Che Wu, and Haley Murphy. 2018. A serendipitous, quasi-natural experiment: Earthquake risk perceptions and hazard adjustments among college students. Natural Hazards 93: 987–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Brian J., Ying Xin Xiong, Paul S. Y. Yip, Chao Kei Lao, Wei Shi, Elvo K. L. Sou, Kay Chang, Li Wang, and Agnes I. F. Lam. 2019. The association between disaster exposure and media use on post-traumatic stress disorder following Typhoon Hato in Macao, China. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 10: 1558709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamideh, Sara, Sabine Loos, Jason Rivera, Alessandra Jerolleman, Heather Champeau, and Haorui Wu. 2023. IJMED special issue: Longitudinal recovery. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters 41: 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Khalid, Masuma Moriom, Shariaj Ibna Mizan Shuprio, Tahmina Bintay Younos, and Arif Chowdhury. 2022. Exploring disaster preparedness of students at university in Bangladesh. Natural Hazards 111: 817–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzweiss, Peggy C., Daniel W. Walker, Ruth Chisum, and Thomas Sosebee. 2020. Crisis planning for online students: Lessons learned from a major disruption. Online Learning 24: 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Kinshi, Miho Sekiguchi, Takuya Nikaido, Ken-Ichi Otoshi, Yohei Matsuo, Takahiro Igari, Yoshihiro Kobayashi, Misa Takegami, Norio Fukumori, Shingo Fukuma, and et al. 2017. Psychosocial stress after a disaster and low back pain-related interference with daily living among college students. Spine 42: 1255–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Inhong, and Won-Oak Oh. 2019. Predictors of posttraumatic growth among university students who experienced a recent earthquake. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 40: 176–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılıç, Nurhayat, and Nuray Şimşek. 2019. The effects of psychological first aid training on disaster preparedness perception and self-efficacy. Nurse Education Today 83: 104203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornbluh, Mariah, Mathew C. Withers, James Ades, Gillian Grennan, and Jyoti Mishra. 2022. Identifying protective socio-ecological factors for college students in California’s deadliest wildfire. Journal of American College Health, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagmay, Ezekiel Adriel D., and Maria Mercedes T. Rodrigo. 2022. The impact of extreme weather on student online learning participation. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning 17: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Betty S., Ann-Margaret Esnard, Chris Wyczalkowski, Ryan Savage, and Hazel Shah. 2019. Trajectories of school recovery after a natural disaster: Risk and protective factors. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy 10: 32–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Betty S., Barbora Hoskova, Alexa Riobueno-Naylor, Courtney A. Colgan, Samantha S. Aubé, and Belle Liang. 2022. College students and COVID-19: Mental health and purpose formation. Journal of Emergency Management 20: 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Betty S., Melissa C. Osborne, NaeHyung Lee, Shannon Self-Brown, Ann-Margaret Esnard, and Mary Lou Kelley. 2018. Trauma-informed schools: Child disaster exposure, community violence and somatic symptoms. Journal of affective disorders 238: 586–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemieux, Catherine M., Aimee Moles, Kimberly M. Brown, and Erma J. Borskey. 2020. Social work students in the aftermath of the Great Flood of 2016: Mental health, substance use, and adaptive coping. Journal of Social Work Education 56: 630–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loudd, Grace, Nicole Willis, and Needha Boutté-Queen. 2018. Back to college during hurricane recovery: Faculty and Students Navigating the New Semester Together. Reflections: Narratives of Professional Helping 24: 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lovekamp, William E., and Sara K. McMahon. 2011. I have a Snickers bar in the trunk of my car: Student narratives of disaster risk, fear, preparedness, and reflections on Union University. International Journal of Mass Emergencies & Disasters 29: 132–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, Sarah R., Andrew Ratanatharathorn, Betty S. Lai, Willem van der Mei, Anna C. Barbano, Richard A. Bryant, Douglas L. Delahanty, Yutaka J. Matsuoka, Miranda Olff, Ulrich Schnyder, and et al. 2021. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptom trajectories within the first year following emergency department admissions: Pooled results from the International Consortium to predict PTSD. Psychological Medicine 51: 1129–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marris, Emma. 2019. Why young climate activists have captured the world’s attention. Nature 573: 471–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marthoenis, Marthoenis, Inong Meutia, Hizir Sofyan, and Meryam Schouler-Ocak. 2018a. Exposure to traumatic events and PTSD in a post conflict and disaster-prone area. Journal of Loss & Trauma 23: 128–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marthoenis, Marthoenis, Inong Meutia, Liza Fathiariani, and Hizir Sofyan. 2018b. Prevalence of depression and anxiety among college students living in a disaster-prone region. Alexandria Journal of Medicine 54: 337–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, Marry L. 2012. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica (Zagreb) 22: 276–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mızrak, Sefa, and Ramazan Aslan. 2020. Disaster risk perception of university students. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy 11: 411–33. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, Wai Yin, Jonathan Rex Mok, and Kit Yee Cheung. 2016. On effort and achievement of business undergraduate and graduate students under a disastrous event. International Education Studies 9: 230–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Neal, Jennifer Watling, Zachary P. Neal, Erika VanDyke, and Mariah Kornbluh. 2015. Expediting the Analysis of Qualitative Data in Evaluation: A Procedure for the Rapid Identification of Themes From Audio Recordings (RITA). American Journal of Evaluation 36: 118–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, Sylvia, Sally Carlton, Jennifer H. K. Wong, and Sam Johnson. 2021. ‘Spontaneous’ volunteers? Factors enabling the Student Volunteer Armymobilisation following the Canterbury earthquakes, 2010–2011. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 53: 102008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA. 2023a. State of the Climate: Global Climate Report for 2022. January 18. Available online: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/monthly-report/global/202213 (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- NOAA. 2023b. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Overview. National Centers for Environmental Information. Available online: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions/ (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Novak, Jenny, Julian C. Lozos, and Suzanne E. Spear. 2019. Development of an interactive escape room intervention to educate college students about earthquake preparedness. Natural Hazards Review 20: 06018001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Medicine 18: 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Ronik Ketankumar, Apurva Pamidimukkala, Sharareh Kermanshachi, and Roya Etminani-Ghasrodashti. 2023. Disaster preparedness and awareness among university students: A structural equation analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20: 4447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Ronik Ketankumar, Sharareh Kermanshachi, and Thahomina Jahan Nipa. 2020. Establishment of a framework to measure disaster preparedness: Development of strategies to enhance disaster preparedness activities. Paper presented at Creative Construction e-Conference 2020, Budapest, Hungary, June 28–July 1; pp. 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Peek, Lori, Jennifer Tobin-Gurley, Robin S. Cox, Leila Scannell, Sarah Fletcher, and Cheryl Heykoop. 2016. Engaging youth in post-disaster research lessons learned from a creative methods approach. Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement 9: 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, Lori, Jennifer Tobin, Rachel Adams, Haorui Wu, and Mason Mathews. 2020. A framework for convergence research in the hazards and disaster field: The natural hazards engineering research infrastructure CONVERGE facility. Frontiers in Built Environment 6: 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, Lori, Tricia Wachtendorf, and Michelle Annette Meyer. 2021. Sociology of Disasters. In Handbook of Environmental Sociology. Edited by Beth Schaefer Caniglia, Andrew Jorgenson, Stephanie A. Malin, Lori Peek, David N. Pellow and Xiaorui Huang. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, Betty, Carl F. Weems, Brandon G. Scott, Pascal Nitiéma, Mary A. Noffsinger, Rose L. Pfefferbaum, Vandana Varma, and Amarsha Chakraburtty. 2013. Research Methods in Child Disaster Studies: A Review of Studies Generated by the September 11, 2001, Terrorist Attacks; the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami; and Hurricane Katrina. Child & Youth Care Forum 42: 285–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowski, Chris. 2015. Mass media use by college students during hurricane threat. College Student Journal 49: 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, Amanda, Brenda Sautner, Joy Omege, Edward Denga, Bernard Nwaka, Idowu Akinjise, Sandra E. Corbett, Shahram Moosavi, Andrew Greenshaw, Pierre Chue, and et al. 2021. Long-term mental health effects of a devastating wildfire are amplified by sociodemographic and clinical antecedents in college students. Disaster Medicine And Public Health Preparedness 15: 707–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque, Genesaret Flores. 2022. Psychological effects before, during and after Hurricane Maria. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 35: 843–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T., H. Ambo, and K. Fukuda. 2017. Sleep problems caused by a great natural disaster: A 4-year longitudinal study after the great east Japan earthquake in 2011. Sleep Medicine 40: e292–e293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannonhouse, Laura, Michele Hill, and Jennifer Hightower. 2022. Trauma exposure, suicidality, and reporting in college students. Journal of American College Health 70: 331–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Vinita, Bruce Lubotsky Levin, Guitele J. Rahill, Julie A. Baldwin, Aditi Luitel, and Stephanie L. Marhefka. 2021. Post-earthquake self-reported depressive symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder and their correlates among college-youths in Kathmandu, Nepal. Psychiatric Quarterly 92: 1595–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Wei, and Brian J. Hall. 2020. Help-seeking preferences among Chinese college students exposed to a natural disaster: A person-centered approach. European Journal of Psychotraumatology 11: 1761621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Wei, and Brian J. Hall. 2021. Help-seeking intention among Chinese college students exposed to a natural disaster: An application of an extended theory of planned behavior (E-TPB). Social Psychiatry And Psychiatric Epidemiology 56: 1273–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sholes, Jay, Adam Sullivan, and Stanley Self. 2023. The impact of long-term disruptions on academic success in higher education and best practices to help students overcome them. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice 23: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sözen, Erol. 2019. The earthquake awareness levels of undergraduate students. Journal of Pedagogical Research 3: 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SSEER. 2023. SSEER Researchers Map. University of Colorado Boulder. Available online: https://converge.colorado.edu/research-networks/sseer/researchers-map/ (accessed on 17 October 2023).

- Szecsi, Tunde, Hasan Aydin, and Debra Giambo. 2023. Lived experiences of Puerto Rican university students displaced to South Florida after Hurricane Maria. Multicultural Learning and Teaching 18: 163–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, Alexa, and Brent Doberstein. 2015. Emergency preparedness amongst university students. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 13: 409–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorup-Binger, Christian, and Nadia A. Charania. 2019. Vulnerability and capacities of international students in the face of disasters in Auckland, New Zealand: A qualitative descriptive study. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 39: 101136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachuck, Mathew A., Stefan E. Schulenberg, and Elicia C. Lair. 2018. Natural disaster preparedness in college students: Implications for institutions of higher learning. Journal of American College Health 66: 269–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tompkins, Forbes, and Brian Watts. 2022. Flooding Is Nearly a Daily Occurrence Throughout the U.S. Pew Charitable Trusts. Available online: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/articles/2022/12/15/flooding-is-nearly-a-daily-occurrence-throughout-the-us#:~:text=Since%202000%2C%20at%20least%20one,affected%20by%20flooding%20in%202021 (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Türksever, Ömer. 2021. Analysis of Disaster Awareness Perception Levels of Students in Social Studies Teaching Undergraduate Program. Education Quarterly Reviews 4: 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction [UNDRR]. 2015. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren.pdf?_gl=1*v7kiii*_ga*ODcwMzUyODA1LjE3MDExODQwMzY.*_ga_D8G5WXP6YM*MTcwMTE4NDA0Ni4xLjEuMTcwMTE4NDExMi4wLjAuMA (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Villasana, Marcia, Tecnológico de Monterrey Mexico, Bertha E. Cárdenas, Marianela Adriaenséns, Ana Catalina Treviño, and Jorge Lozano. 2016. Mainstreaming disaster risk management in higher education. Ad-Minister 28: 243–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, Cameron T., and Melanie M. Bowers. 2023. Queering Climate Change: Exploring the Influence of LGBTQ+ Identity on Climate Change Belief and Risk Perceptions. Sociological Inquiry 93: 413–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Haorui. 2020. Airdropped urban condominiums and stay-behind elders’ overall well-being: 10-year lessons learned from the post-Wenchuan earthquake rural recovery. Journal of Rural Studies 79: 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Haorui. 2022. Mass email risk communication: Lessons learned from the COVID-19-triggered campus-wide eviction in Canada and the United States. PLoS ONE 17: e0266242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Haorui, and F. Etienne. 2021. Effect of climate change on food production (animal products). In A Comprehensive Study of Physical, Social, and Political Issues. Edited by Trevor M. Letcher. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 233–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Haorui, Lindsay Heyland, Mandy Yung, and Maryon Schneider. 2023. Human-animal interactions in disaster settings: A scope literature review. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 14: 369–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Haorui, Marla Perez-Lugo, Cecilio Ortiz Garcia, Frances Gonzalez Crespo, and Adriana Castillo. 2021. Empowered stakeholders: University female students’ leadership during the COVID-19-triggered on-campus evictions in Canada and the United States. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 12: 581–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Guangzhe, Crystal L. Park, Samuel R. Birkeland, Paul S. Y. Yip, and Brian J. Hall. 2021a. A network analysis of the associations between posttraumatic stress symptoms and posttraumatic growth among disaster-exposed Chinese young adults. Journal of Traumatic Stress 34: 786–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Guangzhe, Wei Shi, Sarah Lowe, Kay Chang, Todd Jackson, and Brian J. Hall. 2021b. Associations between posttraumatic stress symptoms, perceived social support and psychological distress among disaster-exposed Chinese young adults: A three-wave longitudinal mediation model. Journal of Psychiatric Research 137: 491–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Di, Xiaofang Zhu, Zhengrong Zhou, Xiao Xu, Xueying Ji, and Aihua Gong. 2021. Research on disaster literacy and affecting factors of college students in central China. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 15: 216–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Identified Publications | Duplicates Removed | Total Publications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Embase | 433 | 86 | 347 |

| ProQuest Central | 1208 | 247 | 961 |

| Scopus | 218 | 143 | 75 |

| Web of Science | 341 | 1 | 340 |

| Google Scholar | 20 | 0 | 20 |

| Total | 2220 | 477 | 1743 |

| Keyword Groups | Keywords |

|---|---|

| College Student | “college student” OR “college students” OR “university student” or “university students” OR higher education OR tertiary education |

| Disaster | disaster* OR “disaster response” OR “disaster preparedness” OR “disaster recovery” OR “disaster relief” OR “disaster reconstruction” OR “disaster mitigation” OR flood* OR wildfire* OR bushfire* OR hurricane* OR earthquake* OR storm* OR heatwave* OR tornado* |

| Impacts | “mental health” OR well-being OR disrupt* OR relocate* OR displace* OR grade* OR “education impacts” |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| The population of interest must include college students, including those enrolled at community colleges and in post-graduate programs such as graduate schools and professional schools (e.g., JD, MD, DDS, etc.). | Studies focused on university staff or faculty. Studies examining students who are not in college including elementary school or high school. |

| Selected articles will be situated in the context of environmental disasters and/or hazards impacting college students, including floods, hurricanes, wildfires, etc. | Studies focused on public health disasters such as COVID-19 or influenza will be excluded as the focus is on the effect of environmental disasters on college students. Studies examining technological disasters or willful/intentional disasters such as shootings, oil spills, war, and explosions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Breen, K.; Montes, M.; Wu, H.; Lai, B.S. College Students and Environmental Disasters: A Review of the Literature. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13010008

Breen K, Montes M, Wu H, Lai BS. College Students and Environmental Disasters: A Review of the Literature. Social Sciences. 2024; 13(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleBreen, Kyle, Mauricio Montes, Haorui Wu, and Betty S. Lai. 2024. "College Students and Environmental Disasters: A Review of the Literature" Social Sciences 13, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13010008

APA StyleBreen, K., Montes, M., Wu, H., & Lai, B. S. (2024). College Students and Environmental Disasters: A Review of the Literature. Social Sciences, 13(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13010008