Abstract

The representation of disabled individuals in museum spaces worldwide has sparked substantial debate in recent decades. It has become increasingly evident that disabled people’s lives and experiences have been overlooked, under/misrepresented in museum narratives, or as museum professionals and academics have highlighted, ‘buried in the footnotes’ of history. Museums can either challenge or continue such exclusion through their actions. This marginalization of disabled people from our present museums narratives contributes to the perpetuation of prejudice and systematic biases that reinforce their exclusion in contemporary society. Nevertheless, the call for change has never been more pressing. Museums, as ‘agents of social change’, are required to not only address the absence of disabled people in their narratives but to combat prejudicial ideas about disability and drive societal changes to support social inclusion. This paper intends to use the recent movement of disability representation to envisage how national museums in Egypt can challenge societal prejudice by representing disability narratives from ancient Egypt in their exhibitions. The historical perspective of disability in ancient Egypt is a compelling example for illustrating social acceptance and the level of inclusion for disabled individuals in contrast to the negative stereotypes prevalent in contemporary Egyptian society. By adopting the new emergent approach of ‘Representing Disability’. Egyptian museums can stimulate discussions on disability issues and advocate for social change while connecting disabled individuals with a history that acknowledges their contributions and existence. The paper employed qualitative research methods to answer the following research question: what impact do representations of disability from ancient Egypt have on the way national museums engage with societal discourses about disability? Please note the article includes images of human remains.

1. Introduction

The concept of what a museum is, who it is for, and what cultural and social impact it can have on society is undergoing change and rebirth. The traditional responsibilities of museums that aim to collect, preserve, and share knowledge are now being called upon to embrace new roles in fostering relationships, encouraging participation, advocating for social justice, and promoting inclusion (Coffee 2008; Janes and Sandell 2019; Sandell 1998; Silverman 2010). The old perception of the museum that was built upon its cultural status as a ‘cultural authority’ (McCall and Gray 2014) and centered on “museum methods, and too little about the purposes of museums” (Vergo 1989, p. 3) had, over time, altered to focus more on its social purposes.

With the emergence of the ‘new museology’ in the late 1980s (Desvallées and Mairesse 2010), the roles of museums were redefined to consider wider social and political dimensions (Brown and Mairesse 2018; McCall and Gray 2014) and extended to become more visitor-centered in countering the traditional approach of curatorship and collections-based function (Weil 1999). The conceptual and critical thinking around museums has, therefore, moved in a variety of directions to impact positively the lives of individuals, communities, and the wider society (Sandell 2002, p. xvii).

New terms and concepts appeared in 2022’s updated ICOM definition of museums that were approved during the 26th ICOM General Conference in Prague, emphasizing inclusion, communities, and social roles as core values for the museums now and in the future. ‘Inclusivity’, ‘accessibility’, ‘diversity’, and ‘sustainability’, (International Council of Museums—ICOM 2022) became imperative for museums to stay relevant in the troubled world (Janes 2009) and to engage in developing sustainable solutions toward human rights and social justice. This expansion in the roles encompassed policies and organizational actions for ensuring a culturally accessible experience and integrating universal design principles to overcome physical, sensory, intellectual, and social barriers faced by disabled people in museum environments.

Over time, the increased access to museums by disabled people has demanded museums to encompass issues related to disability representation to consider what these disabled individuals would encounter and how to acknowledge their histories, voices, and perspectives in museum experiences (Lawrence 2025).

In Egypt, as in many parts of the Arab world, disabled individuals encounter numerous structural and sociocultural barriers that restrict their participation in society. They are frequently marginalized and stigmatized due to the prevailing biases in Egyptian society towards the medical and charity models of disability and prevalent cultural stigma, negative attitudes, and discriminatory social structures. In recent years, Egypt’s national museums have experienced significant changes in their social roles to support the inclusion of disabled people through several programs and initiatives. In responding to these growing social responsibilities of Egyptian museums, incorporating disability representations from ancient Egyptian history in their exhibitions and programs, which is currently lacking, can contribute to expanding their societal responsibilities and reshaping public attitudes towards disability, challenging societal stereotyping and prejudice in contemporary Egyptian society.

This qualitative research examines how the national museums of Egypt, particularly those ancient Egyptian collections, can incorporate disability representations into their content to uncover underrepresented or misrepresented disability histories from ancient Egypt. The case studies focus on the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (EMC) and the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization (NMEC). The study empirically assesses the current portrayal (or omission) of disability in museum narratives and exhibitions. Furthermore, it explores the potential of incorporating disability-related narratives from ancient Egypt to broaden the museums’ engagement with societal discussions about disability while addressing biases and prejudices prevalent in contemporary Egyptian society.

The author has intentionally used identity-first language (e.g., ‘disabled individual’) throughout. This choice aligns with the preferences of many disability theorists and researchers (Barnes and Mercer 2010, p. 11; Oliver 1990).

2. Literature Review: Theoretical Framework

2.1. Museums and the Inclusion of Disabled Individuals: From Margins to the Core

Over the last century, museums experienced paradigmatic shifts—in both theories and practices—that emerged from the need to achieve relevance to contemporary society (Anderson 2004; Black 2012; Sandell and Nightingale 2012). While their cultural role as institutions is to collect, preserve, display, and educate the public about art and artifacts, they are rooted in society and have an acting role and public function in the service of society (Bennett 1995; Brown and Mairesse 2018). Many diverse policies, structures, and social practices have developed within the museum in response to and contributing to its social relationship with communities (Coffee 2008; Morse 2022, pp. 10–12) to be more inclusive and collaborative and to share authority with the community outside the museum (American Alliance of Museums 2002; Hein 1998; Hooper-Greenhill 2000).

Museums have moved away from exclusivity and being isolated from the modern world—as it was argued in 1971 (Brown and Mairesse 2018; Hudson 1977)—to embrace the constructivist theories of the post-modern, advocating a new approach centered on people and the inclusive mission of the museum (Hein 1998; Hooper-Greenhill 2000). Hooper-Greenhill viewed this shift as a new model of the museum, ‘the post-museum’ that transforms from collecting and storing to entertaining and engaging, and it became more inclusive to maintain relevance to contemporary society and continue to shape our knowledge (Hooper-Greenhill 2000).

These emergent social roles that museums have today toward society, beyond their distinct cultural roles, were shaped by complex socioenvironmental conditions, activists’ movements, the impact of new technologies, the establishment of social history, the scientific revolution, and much more rapid societal developments that we are all a part of (Black 2012; Janes and Sandell 2019; Moore et al. 2022; Morse 2022). As society continues to change, museums continue to evolve and expand to stay relevant to the rapidly changing society and continuously challenging sociopolitical issues of contemporary life. Within this emergent perspective of the social work of museums, the value of inclusion explicitly penetrated the museum discourse as the ‘social inclusion theory’ (Moore et al. 2022, p. 14) and harnessed museums’ services and resources to address contested issues in their communities (Tlili 2008), and social exclusion, that are perceived as access barriers and advocating for the inclusion of oppressed, marginalized, and vulnerable groups beyond the confines of their buildings (Moore et al. 2022; Morse 2022).

In many empirical studies worldwide on the museums’ social roles, museums are acknowledged as ‘agents of social change’ (Sandell 1998). A shift harkens back to the pioneering article of Sandell, which expressed museums’ political roles and social responsibilities in the face of ongoing societal changes (Sandell 1998, 2002). Extensive literature has been produced, advocating for maximizing museums’ engagement in social work (Silverman 2010) and promoting socially purposeful practices at museums (Dodd 2015) to embrace public debates and contested human rights issues (Sandell and Nightingale 2012). Many international works highlight the social purpose and positive impact museums have as society changers on supporting people’s lives and alleviating their social exclusion and injustices.

2.2. Museums and the Advocacy for Social Justice and Activism

In today’s rapidly changing world, museums have increasingly been working towards being socially purposeful. They are positioning themselves as ‘social agencies’ actively engaging with contemporary political issues to promote equity and social justice (O’Neill 2011), confront prejudice, advocate for human rights, and empower marginalized groups, such as disabled individuals (Janes and Sandell 2019; Sandell 2002; Sandell and Nightingale 2012). “Social Justice is at the heart of the impact of museums” as echoed by the 2013 report and campaigns of Museum Change Lives of the Museum Associations, which stressed the museums’ potential for supporting positive social change and fostering debates and critical thinking in response to contemporary issues (Museum Association 2013, p. 4).

The argument supporting the social justice agenda in museums is based on the profound impact that museums have on their audiences, communities, and wider society (Sandell 2007). The way museums address complex and contentious topics can significantly influence the views of their visitors. Advocates argue that for museums to undertake socially impactful work, they must actively participate in activism and advocate for political and social change. Marstine contends that “the museum can be an ideal laboratory for promoting social justice and human rights” (Marstine 2011, p. 13). MacLeod emphasizes that museums can present authentic and nuanced narratives as “environments full of possibility rather than displays full of information” (MacLeod 2018, p. 25).

Several academic authors in museum studies have argued that museums need to prioritize ethical approaches in their museological practices to challenge negative stereotypes and representations of disabled people prevalent in society, helping visitors make meaning (Dodd 2015; Sandell 2011; Sandell et al. 2010). As ‘trustworthy institutions’ museums are in a strong position to challenge dominant views and “provoke, stimulate debate and expose visitors to alternative perspectives” (Sandell 2011, p. 141). This perspective has led to new movements in the museums sector outside its traditional practices, encouraging museums to address ‘activism’ and ‘disability’, advocate for human rights, and engage visitors in dialogues to rethink their attitudes and understanding of disability issues (Janes and Sandell 2019; Sandell 2011; Sandell et al. 2010). ‘Exploring anti-ableism’ is one of the key themes addressed in the 2023 Museum Association, where sessions delved into how museum representation can powerfully address societal conversations and combat prejudices (Museum Association 2023). In this way, museums offer visitors new ways of seeing and engaging in activist ethical approaches, and in doing so, they reinforce human rights. The ‘activist museum practice’, which emanated from disability studies and human rights activism (Janes and Sandell 2019) and reshaped museum practices to be anti-discriminatory (Bayer et al. 2017), has developed inclusive visions in narrative production in museums to offer “ways of seeing which subvert dominant (discriminatory, oppressive, stereotypical) representations” (Sandell 2011, p. 129) and instead provide visitors with new ways to understand disability and the lives or experiences of disabled people, challenging stereotypes, and prejudice (Delin 2002; Martins 2018; Sandell et al. 2010; Sandell and Dodd 2010) (See Below).

2.3. Hidden Histories

The concept of representing ‘hidden histories’ is gaining increased attention in the museum sector (Hunt 2021, p. 23). Museums have the potential and responsibility to address various social issues, give voice to overlooked disabled communities, and impact public perception (Delin 2002; Sandell et al. 2010). ‘Hidden histories’ encompass a range of narratives labeled as contested, silenced, or challenging—stories that have often been overlooked or omitted due to societal taboos and a lack of documentation (Hunt 2021; Martins 2018). These hidden narratives pose a challenge for museums as they may contradict the preferred traditional narratives and are concealed due to various factors that work together to prevent their telling.

Delin (2002) argued that there are three reasons for the absence of disabled people in museum content. First, throughout history, disabled people have faced barriers in finding employment. They were frequently limited to specific roles, such as relying on charity or being exhibited in freak shows. As a result, the stories we hear about disability history often lack diversity and tend to focus on these limited perspectives. Second, present-day prejudices prevent modern curators from engaging with disability history. They are unwilling to engage in debate around disability, refusing to “search under words ‘deformity’ or ‘cripple’—which is where disabled history is” (Delin 2002, p. 86). Consequently, this history continues to be silenced—”not passively hidden but actively concealed” (see Hunt 2021, p. 24). Third, biographical narratives from disabled people have been marginalized over time, overshadowed by more durable records and physical artifacts. Consequently, museum collections tend to overemphasize the medical aspects of disability due to the prevalent types of artifacts available for curation, interpretation, and exhibition.

The lack of a representation of disabled people perpetuates the prevalent societal stereotype that disabled individuals are passive in society and insignificant to historical events. Historical connection to disability past may be perceived as unimportant or omitted for fear of offending. This leads to their exclusion from our shared heritage and culture (Research Centre for Museums and Galleries and National Trust 2023). Many academic authors and museum professionals believe museums are able to shape social values and attitudes and have the capacity to affect social injustice, prejudice, and exclusion (Hooper-Greenhill et al. 2000). Over time, it has become essential for museums to embrace these hidden histories and present a more inclusive and ethical portrayal of our past connected to disability (see below).

2.4. Representing Disability in Museums

Recent decades have seen significant changes in how ‘access’ and ‘inclusion’ to museums are understood. Museums worldwide are increasingly engaging with questions about which communities are represented and which are absent in their exhibition content and collections, and whose knowledge and perspective are reflected in interpretations of objects, texts, and historical narratives. Until the latter part of the 20th century, museums primarily focused on making their spaces physically accessible and attracting new visitors (Sandell and Dodd 2010; Sandell 2011). However, this approach has sparked criticism regarding the underrepresentation and misrepresentation of disabled individuals in museum narratives. Museums have been widely criticized for being elite spaces and serving a narrow section of society (Bennett 1995; Hudson 1977).

Further, studies have shown that disabled communities are not only marginalized in museum content but even when they are represented; they have often been portrayed using negative stereotypes and tropes prevalent in broader society, contributing to an environment of discrimination and inequality (Delin 2002; Martins 2018; Sandell 2017). While some academic and museum professionals advocate for activist practice, using exhibitions and collections to actively engage with social debates and authentically represent disabled communities (Sandell and Dodd 2010; Sandell 2011), others contend that museums have an obligation to provide visitors with an unbiased account of the history and offer nuanced representations of disabled people and their experiences (Sandell et al. 2010). Recent studies by the University of Leicester’s Research Centre for Museums and Galleries and the National Trust (2021–2023) aimed to tackle new ethical and inclusive ways of (re)presenting narratives connected to disability and the lives of disabled people (Research Centre for Museums and Galleries and National Trust 2023). The ‘Everywhere and Nowhere’ project delved into how museums can create more nuanced portrayals of disabled individuals and their experiences. The project developed an ethical framework for practice and presented ten case studies of historical figures from the National Trust’s collection (Research Centre for Museums and Galleries and National Trust 2023).

The growing recognition of the importance of disability representation has motivated museums to actively search disability histories, address their exclusion/misrepresentation, and raise awareness of and challenge the prevalent negative stereotypes surrounding disability. Incorporating disability histories into museum narratives involves embracing theories and methodologies from the disability rights movement, including the social model which identifies attitudes and barriers as limiting opportunities and access for disabled people and recognizes society’s responsibility to address these barriers (Barnes et al. 1999). This model guides representations of disability within museums to ensures ethical interpretive practices (Research Centre for Museums and Galleries and National Trust 2023; Sandell and Dodd 2010). Further, instead of relying solely on established disciplinary knowledge, museums have embraced a ‘contemporary lens’, allowing visitors to critically engage with the narratives they encounter (Lawrence 2025). In addition, disabled voices were included in creating and producing the narratives to ensure relevance to disabled communities.

Incorporating and improving disability representation has increasingly been framed as a museum responsibility, particularly following the project of ‘Buried in the Footnotes: The Representation of disabled people in Museum and Gallery Collections (2003–2004)’ carried out by Leicester University Research Center for Museums and Galleries (RCMG) (Delin 2002). The project investigated how disability-related artifacts were displayed, interpreted, and communicated to the public in UK museums. The project concluded that the interpretations of these artifacts reproduced cultural stereotypes about disabled people (Sandell et al. 2005). The findings of this project have informed the ‘Rethinking Disability Representation in Museums and Galleries (RCMG)’ action projects (2006–2008). RCMG initiated and managed these projects in collaboration with museum staff and a think tank of disabled activists and cultural practitioners (Dodd et al. 2010; Sandell 2011). These projects addressed the reasons for the lack of museum engagement with disability themes and identified problematic representation. Later, they collaborated with nine museums across the UK to reinterpret disability-related objects in their collections and explore the following:

“What happens when visitors to museums and galleries encounter displays, educational programmes and other interpretive projects that are designed to offer and elicit support for new ways of understanding disability?”.(Dodd et al. 2010, p. 92)

These projects revealed fundamental shifts in visitors’ perceptions and understanding of disability within its social and cultural context. They have played a significant role in constructing and communicating meaning about disability, bringing narratives about disabled people into museum settings where their lived experiences are valued as experts. This challenges stereotypes that marginalize disabled individuals and highlight that disability is an integral part of broader human experiences, both in the past and present.

Several prominent worldwide exhibitions have been produced that focus on representing disability, portraying disabled people in both historical and contemporary settings, and reflecting on their histories, experiences, and voices (Martins et al. 2018; Tooke 2006). These exhibitions have included interpretive interventions allowing for the exploration of misconceptions about disability, forms of discrimination, and prejudice. At the same time, they communicate new ideas and insights that encourage social transformation and changes in attitudes toward persons with disabilities (Zakaria 2025). These efforts are guided by the social model of disability, which views disability as a human rights issue.

3. Research Strategy

Drawing on the global movement to represent disability in museums and the pivotal role that museums can play in combating prejudice and reshaping public attitudes about disability, this study aims to envisage how national museums in Egypt can confront societal biases and prejudice by representing authentic narratives connected to disability from ancient Egypt in their exhibitions and programs. The study strongly advocates for expanding the representation of disability narratives from ancient Egypt in Egyptian museums, highlighting the untapped potential for reinterpreting disability-related artifacts, and revealing underrepresented or misrepresented disability histories. The historical perspective of disability in ancient Egypt is a compelling example for illustrating social acceptance and the level of inclusion for disabled individuals in contrast to the negative stereotypes and stigmatization prevalent in contemporary Egyptian society.

3.1. Description of the Case Study

The study explores the implications of disability representation in the national museums of Egypt on expanding their engagement with societal discourse about disability and energizing initiatives that promote the inclusion of disabled people in society. Two main national museums, the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (EMC) and the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization (NMEC), have been selected for case study analysis. The study seeks to assess their current practices in presenting and interpreting disability-related artifacts to develop a holistic view of re-presenting disability histories from ancient Egypt in national museums of Egypt in a way that can stimulate a shift in current thinking in Egyptian society and reshape public perceptions of disability. Both museums are affiliated with the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities (MoTA), the leading governmental body overseeing Egypt’s cultural heritage (archaeological sites and museums) (Zakaria 2024, Table 5). These two museums, specifically the EMC, are known for their extensive collections of ancient Egyptian artifacts and their renowned reputation. They have significant impacts not only on a national level but also on an international scale.

3.1.1. Egyptian Museum of Cairo (EMC)

The Egyptian Museum, also known as ‘the mother of all Egyptian museums’, is situated in the heart of Tahrir Square, Cairo. The museum features a unique building purposefully designed to house its collection of ancient Egyptian artifacts, the oldest in the world. With over 100 exhibition halls, the museum was established as a result of a competition initiated by the Egyptian Government in 1895, making it the first national museum in the Middle East (The Egyptian Museum 2024a). It is one of the largest museums globally and holds significant scientific value. The museum is a leading institution for studying, researching, conserving, and exhibiting ancient Egyptian history. Its collection spans prehistory, ancient Egyptian historical periods, and the Graeco-Roman periods (El-Saddik 2005). In 2019–2023, the MoTA launched the ‘Transforming the Egyptian Museum of Cairo’ project in collaboration with an EU consortium of five major European museums. The consortium includes the Museo Egizio (Turin, Italy), the British Museum (London, UK), the Musée du Louvre (Paris, France), the Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung (Berlin, Germany), the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden (Leiden, The Netherlands), and the ICA (Istituto Centrale per l’Archeologia, Ministero per i Beni e le Attivitá, Italy) (European Union 2023). The project aims to develop a master plan for the museum after relocating some of its collections and artifacts to the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM), NMEC, and other new national museum projects. The plan focuses on improving the EMC’s permanent galleries through new displays and refurbishment, as well as collaborating with European partners on conservation and restoration projects (Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities 2019; The Egyptian Museum 2024b). Several galleries have recently reopened with new displays, improved lighting systems, updated labels, audience programs, and digital services.

3.1.2. National Museum of Egyptian Civilization (NMEC)

The National Museum of Egyptian Civilization (NMEC) is a significant museum established by the Egyptian government in cooperation with UNESCO. It is situated in old historic Cairo, a World Heritage Site known as Al-Fustat. It is the first museum of civilization in the Arab world. The museum aims to present the extensive and varied history of Egyptian civilization till the present day. It presents the richness and diversity of Egyptian civilization from prehistoric, ancient Egyptian, Graeco-Roman, Coptic, Islamic, modern, and contemporary eras, illustrating the continuous legacy of Egypt’s tangible and intangible heritage (Abdel Moniem 2005). The NMEC’s foundation stone was laid in 2002, and the first phase began in 2004, followed by the second in 2010. As of now, only two out of the eight planned permanent galleries have been completed and were officially opened on 4 April 2021. These two halls are the core gallery (ground floor) and the mummy gallery (lower floor), which displays twenty royal mummies of Egyptian kings and queens (Zakaria 2025). Additionally, a temporary gallery has been open since 2017, initially showcasing ‘Egyptian crafts and industries across Ages.’ This temporary exhibition gallery, now named the Egyptian Textile Hall, currently exhibits the textile collections from the Textile Museum on Al-Moez Street, which were moved to NMEC in 2022 (National Museum of Egyptian Civilization 2022b). In 2021, the NMEC hosted a significant opening ceremony featuring the transportation of the royal mummies from the EMC to the mummy exhibition gallery at NMEC. This grand event was attended by the state president and numerous dignitaries, adding to its historical significance.

3.2. What Is the Historical Perspective of Disability in Ancient Egypt, and Why Is It Significant?

Ancient Egypt, commonly known as the Pharaonic culture, was one of the earliest and most advanced civilizations in ancient times. The history of ancient Egypt spans from prehistoric times to the Graeco-Roman periods and includes the following periods: Prehistoric times (c.700,000 BP), Predynastic (c.4000–3200 BC), Early Dynastic Period (c.3200–2686 BC), Old Kingdom (c.2686–2160 BC), 1st Intermediate Period (c.2160–2034 BC), Middle Kingdom (c.2043–1650 BC), 2nd Intermediate Period (c.1650–1550 BC), New Kingdom (c.1550–1069 BC), 3rd Intermediate Period (1069–664 BC), to Late Period (c. 664–332 BC), and Graeco-Roman Periods (332 BC–306 AD) (Zakaria 2021, p. 6). Ancient Egyptians built large architectural monuments, temples, and tombs to honor their deities and rulers. Their language and historical documentation provide modern scholars valuable insights into their daily lives through inscriptions, representations on tomb and temple walls, and documents on papyri and funerary objects (Shaw 2003).

The extensive collection of iconographic and textual resources, still preserved today, presents an exceptional and significant opportunity to explore ancient Egyptian society’s perception of disability. The depictions of disabled individuals with various impairments and mythological figures, such as those with dwarfism were prevalent in the tombs’ wall paintings, artifacts, and other sculptures as part of everyday life (Figure 1a,b and Figure 2), indicating the diverse and inclusive nature of ancient Egyptian society (Dasen 2013; Dawson 1938; Mahran and Mostafa Kamal 2016; Nunn 1996). The inclusion of disabled people in different work domains and professions, whether in religious or public services, was documented in Egyptian art, tombs, wall paintings, and textual records (David 2016, pp. 83–84).

Figure 1.

(a): Showcase featuring the group statue of Seneb, a high-ranking priest with dwarfism, depicted alongside his average-sized wife, their two children, and funerary items from his tomb, the Old Kingdom, EMC. (Photo by author). (b): Close-up view of Seneb and his wife, highlighting the detailed craftsmanship. (Photo by author).

Figure 2.

Two standing statues of individuals with dwarfism. On the left is Khnumhotep, a figure of high social status, and on the right is Petpennisut. Both are from the Old Kingdom, EMC. (Photo by author).

Artistic representations from the Old and Middle Kingdoms often depicted individuals with leg, knee, or back impairments engaged in daily activities (Dasen 2013; David 2008, 2016; Dawson 1938; Mahran and Mostafa Kamal 2016; Weeks 1970), contrasting with the idealized portrayals of kings and elites, whose perfect physiques symbolized their afterlife aspirations. Minor figures were shown in profile with full chest and shoulder views, allowing for realistic depictions of movement and bodily features, including disabilities (Dasen 2013; Kanawati et al. 2009; Weeks 1970; Zakrzewski 2014). Scholars suggest that conditions like dwarfism or congenital disabilities were socially accommodated, while impairments acquired later, such as spinal kyphosis from tuberculosis, were often viewed negatively and associated with non-elite status, reflecting instances of exclusion (Jeffreys and Tait 2000, pp. 91–92). Others argue that disability was normalized as part of life, highlighting the active role of physical differences and varying abilities in ancient Egyptian society, assuming a form of a ‘fluid continuum of ability’ between the disabled and able-bodied in different situations and at various stages of their lives (Zakrzewski 2014, pp. 64–65). Interestingly, this latter perception resonates with contemporary rural communities in Egypt, where modern biases are less prevalent. Disabled individuals are valued as active members of their families and communities, contributing to work activities and communal life according to their abilities.

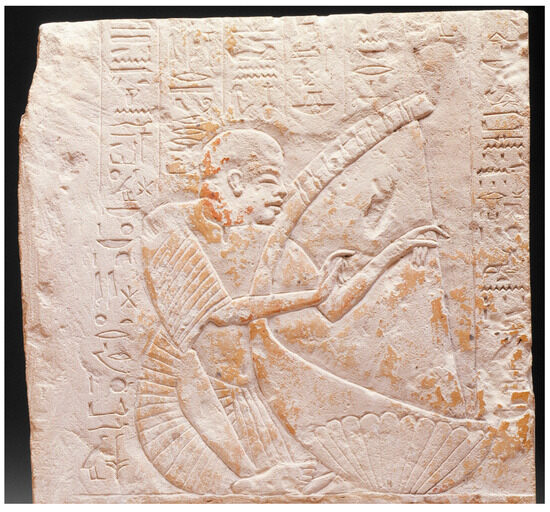

Depictions of blind individuals suggest they held a special societal status. They are often shown as harpists and choir singers in religious festivals or elite households (Fuchs 2006; Manniche 1991), reflecting societal acceptance and encouraging musical careers for the blind. Portrayals of blind harpists with closed eyelids or blindfolded eyes indicate many musicians were blind (Figure 3). While some depictions may have been symbolic (Manniche 1991), they highlight roles deemed suitable for blind individuals, underscoring their inclusion in artistic records and societal significance.

Figure 3.

Relief depicting a blind harpist, 1350–1300 BCE, the New Kingdom. (Source: Detroit Institute of Arts, public domain image).

Throughout history, many civilizations have associated physical beauty and perfect bodies with divine approval and regarded physical deformities as signs of divine disfavor (David 2016, p. 84; Sullivan 2001). In contrast to this view, ancient Egyptian society demonstrated cultural acceptance of physical disabilities, with some disabilities being viewed as divine blessings. Rather than being stigmatized, disability was represented in ancient Egyptian art as a natural part of human differences (Zakrzewski 2014, pp. 64–65) (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Dog holder with kyphosis, the tomb of Nikauisesi, the Old Kingdom, Saqqara. (Photograph by Ahmed Romeih).

Figure 5.

Man with kyphosis, the Old Kingdom, EMC. (Photo by author).

Physical disabilities were not labeled as specific medical conditions but rather embraced as embodiments of physical uniqueness and were even associated with gods, emphasizing their significance in the culture (David 2016, pp. 82–85). Further, ancient Egyptians developed assistive technology to support people with physical disabilities, including mobility aids such as sticks and prostheses (Boonshoft-White 2022; Loebl and Nunn 1997) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Prosthetic toe of Tabaketenmut, an Egyptian woman who had her big toe amputated, Third Intermediate Period, NMEC. (Photo by author).

Undoubtedly, the distinct religious beliefs of the ancient Egyptians shaped their perception of disability and body deformities, particularly the Osirian mythology, which promoted the worship of a physically damaged god who nevertheless attained eternal perfection (David 2016, p. 86). Within the Egyptian pantheon, many gods had non-normative attributes, including deities with dwarfs, such as Bes, Beset, Ptah/Pataikos, and other gods with deformed bodies, such as Hapi (Dawson 1938; Sullivan 2001) (Figure 7). Further, some scholars argue that ancient Egyptians portrayed their Ptolemaic-Egyptian God Harpocrates as having cerebral palsy in their artwork: amulets and statues (Morris 2022, pp. 145–204; 2023). These physical characteristics of bodily differences were often seen as a positive mark of divine blessings with religious significance, leading to the care and respect for the disabled.

Figure 7.

Amulets depicting the god Bes, a protective deity depicted with dwarfism, the Late Period, EMC. (Photo by author).

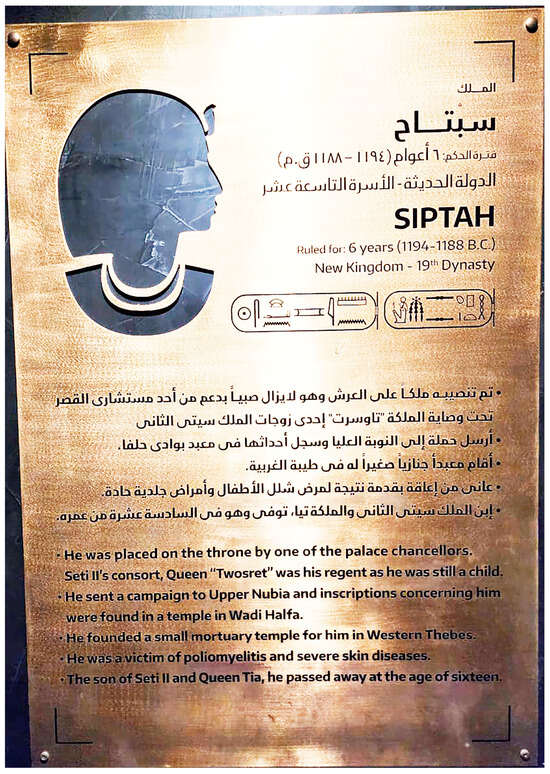

Further, textual resources from different historical periods showcase the evolving social response toward diverse disabilities (Lichtheim 1976, p. 160; 1980, p. 194; Simpson and Ritner 2003). The ‘Instruction of Amenemope’ for example, authored by the high official Amenemope from the 18th Dynasty, offers ethical guidance that mirrors the fundamental values of ancient Egyptian culture, including specific, emphatic directives on the proper treatment of disabled people with respect, regardless of any physical or mental conditions they may have (Lichtheim 1976, p. 160). Moreover, the substantial amount of paleopathological evidence provides insights into various types of disabilities and medical treatment (see Aufderheide and Rodríguez Martín 2011; Sabbahy 2018). Studying human remains and mummies provides significant evidence of the state of health and supplies many biological and cultural data (David 2008; Larsen 1997; Nunn 1996). For example, a recent examination of King Tutankhamun’s mummy from the 18th Dynasty indicates that he may have had clubfoot or congenital talipes equinovarus, as well as other disabling conditions such as Marfan’s Syndrome or Köhler disease II (Hawass et al. 2010). A detailed examination of the king’s feet revealed juvenile aseptic bone necrosis of the left second and third metatarsals (Hawass et al. 2010). There are also other cases of kings with reduced mobility, such as King Siptah from the 19th Dynasty (Figure 8) (see below). However, the disabilities of King Tutankhamun and King Siptah did not prevent them from ruling Egypt.

Figure 8.

Mummy of King Siptah, who had a disability in his left leg, the New Kingdom (19th Dynasty), NMEC (Hawass 2021, p. 110, Figure 53).

In ancient Egyptian society, disability was accepted as a natural part of societal diversity. However, in today’s Egypt, disabled individuals still face negative attitudes and stigma due to implicit biases that contribute to ableism and discrimination. Exploring the historical perspective of disability in ancient Egypt can influence current practices and change public perceptions toward disability.

3.3. Current Disability Landscape in Contemporary Egypt

In Egypt, disabled individuals often experience marginalization and stigma due to pervasive cultural biases, negative attitudes, and discriminatory social structures. According to the 2017 Egyptian Census, 10.7 percent of the population has disabilities (Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics 2024). However, in recent years, the Egyptian government declared that approximately 15% of the population is disabled, making them the largest minority group in the country (Zakaria 2020). As in many societies, contemporary Egypt is shaped by implicit biases—unconscious attitudes and preferences that shape perceptions of individuals based on their abilities or disabilities that may ultimately lead to discriminatory actions (Godsil et al. 2014; Harder et al. 2019).

Egypt is recognized as one of the first countries in the Middle East and North Africa region to address equity in law and advocate for the rights of disabled people (Hagrass 2005). However, these efforts are predominantly rooted in the medical model of disability, which remains entrenched in national policies, academic discourse, and official definitions used in statistics, legislation, and policy development (Zakaria 2020, 2025). The Egyptian Rehabilitation Act 39 of 1975, later amended under Law 49 of 1982, reflects this medicalized perspective, framing disability through a lens of impairment and individual deficiency. This has reinforced the ‘personal tragedy’ model (Oliver 2009), which portrays disabled individuals as victims in need of charity and pity (Hagrass 2005; Zakaria 2020). As a result, national policies concerning disabled people are largely influenced by charitable organizations, religious practices, and individual initiatives, with limited government intervention. The dominance of these approaches perpetuates stereotypes, undermining the agency of disabled individuals. While the 1975 Rehabilitation Act has been replaced by the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Law No. 10 of 2018 (2020), which emphasizes the non-discrimination, accessibility, and empowerment of disabled individuals, the enforcement of this progressive legislation remains incomplete. There is an apparent disconnect between what the state claims in legislation and what is practiced on the ground, particularly in enforcing the rights of disabled individuals across all state sectors. For example, the lack of systematic implementation has perpetuated barriers to accessing education, employment, and healthcare, leaving many disabled individuals excluded from mainstream opportunities. Moreover, the current legislation does not address the required physical adjustments for public transportation, architectural designs, and other environmental barriers, nor does it prioritize public awareness campaigns to combat societal stigma. The cultural shift necessary to foster social inclusion remains elusive without addressing these systemic shortcomings. This gap between policy and practice has further entrenched biases and social exclusion, perpetuating disabled people’s marginalization as societal attitudes continue to view disability through a lens of ‘otherness’. Also, ‘able-bodied’ still holds the dominant social ‘power’ and shapes the narrative around disability through what can be described as an ‘invisible lens’ of social representation (Omarah 2020, p. 8).

3.4. Study Methods and Data Collection

The study used various methods to review and extract data from existing bodies of research literature. This study employed a systematic review approach (Grant and Booth 2009), conducting a thorough examination of the field using the most appropriate databases to establish a theoretical framework designed to explore the shift in museums’ thinking toward the suitability of disability as a topic for museum display. It also delved into how museums have become increasingly motivated to represent disability and use interpretive strategies to encourage the public to rethink their attitudes toward disability. It explored the new movement by museums worldwide, particularly in the UK, where museums have adopted the social model of disability to inform their exhibitions. This approach addresses the social exclusion and marginalization of disabled individuals in the past and present. Additionally, the study included a literature review on ancient Egypt’s perception of disability and historical evidence.

The study also employed semi-structured interviews as a qualitative approach (Creswell and Creswell 2018; Kvale 1996) to explore the views and concerns of museum professionals and curators on incorporating representations of disability and the untold stories of disabled individuals from ancient Egypt into museums exhibitions. The goal was to enhance the understanding of disability issues in Egyptian society and to challenge negative and stigmatizing attitudes towards disabled people. The qualitative approach was chosen due to the scarcity of data and studies on disability representation in national museums of Egypt, as well as the limited information on the historical context of disability within the narratives and storylines presented in these museums (Creswell and Guetterman 2019).

The research questions that underpin this study are the following:

Research Question (1): What impact do representations of disability from ancient Egypt have on the way the national museums of Egypt engage with societal discourses about disability?

Research Question (2): How can these representations reveal the historical perception of disability in ancient Egypt and redefine museums’ societal responsibilities in challenging prevalent negative stereotypes?

Additionally, the study conducted fieldwork and used an observational approach to explore the content of the exhibitions and labels associated with the displays of ancient Egyptian objects related to disability in the permanent galleries of the EMC and NMEC.

3.5. Participants

Twelve participants were intentionally chosen from the museums of EMC and NMEC. Among the participants were six curators from the EMC and four curators from the NMEC, all representing museums affiliated with the MoTA. In order to gain insights from the perspective of disabled people, the study also included two individuals associated with the General Administration for People with Special Needs (GAPSNS), which is affiliated with the MoTA’s museums sector. This included the director himself, who is visually impaired, as well as a museum educator with a disability.

3.6. Data Analysis

The study involved participants from Egypt and was conducted in their native language, Arabic, using the Zoom platform. Open-ended interview questions were employed to gain deep insights into the participants’ perspectives and experiences, allowing for diverse, detailed, and personalized responses (Kvale 1996). Each participant provided informed consent before the interviews, which lasted between 30 and 45 min. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim in Arabic and later translated to facilitate analysis. The data analysis process involved several steps: organizing, sorting, and categorizing the data based on emerging themes that aligned with the study’s research questions, scope, and objectives. This thematic approach ensured that the analysis remained focused on addressing the study’s central aim while capturing the richness of the participants’ experiences. In addition to the main research questions, the study also used the following sub-questions during the interviews:

- How many artifacts related to disability are currently on display in the museums?

- What interpretive methods have been employed to present these artifacts?

- How are these artifacts integrated into the museum’s narratives and exhibitions related to disability?

- Did the museum provide any exhibitions focused on disability in ancient Egypt? If so, what factors have influenced these exhibitions?

- What is the purpose of these exhibitions, and what programs have been implemented to address the topic of ‘disability’? What are the visitors’ responses to these exhibitions?

- How do these exhibitions relate to the ongoing discussions surrounding disability?

4. Results

The feedback from the NMEC and EMC participants revealed a significant gap in the representation of disability and how it is portrayed and framed within the storylines of museums. The study findings, along with participants’ responses, were analyzed and categorized based on themes that emerged from their comments, observations during fieldwork, and a review of displays and labels. Quoted statements from the study participants are used to provide direct insights into their perspectives.

4.1. Disability-Related Artifacts

The EMC contains a diverse range of disability-related artifacts, while the NMEC also houses some, though not many, artifacts related to disabled individuals from ancient Egypt. These artifacts are displayed chronologically in permanent galleries at the EMC and thematically at the NMEC.

One of the EMC’s curators highlighted the following: “We have numerous artifacts related to people with physical disabilities and those with dwarfism from various historical periods. This includes sculptures for people with conditions such as hunched backs and statuettes for Egyptian gods depicted as dwarfs, like the god Bes, as well as numerous terracotta figures depicting people with disabilities from the Graeco-Roman period. It is an exciting collection”. Another curator at EMC added, “We have some coffins with mummies that recent research and CT scans revealed to have disabilities in leg and foot deformities. There is even one from the New Kingdom period with polio, which has been transported to be displayed at the GEM recently”.

NMEC displays the mummy of King Siptah in its mummy gallery. Siptah, an Egyptian ruler from the 19th Dynasty, had a physical disability in his left foot, believed by some Egyptologists to be caused by poliomyelitis, cerebral palsy, or a club foot developed during his childhood (Hawass 2021, pp. 108–10; Ikram 1998; Morris 2022) (see Figure 8). One of the NMEC’s curators remarked the following: “Among the Egyptian mummies in the mummy gallery is the mummy of King Siptah, who had a disability; he suffered from polio”. Another curator shared their experience: “I participated in preparing a showcase in the core gallery for a prosthesis for an Egyptian lady who was disabled” (see Figure 6). A third commented, “I guess we have some artifacts relevant to disability, but they are from other historical periods”.

4.2. Lack of Exhibitions Representing Disability

Despite the presence of disability-related artifacts, neither the EMC nor NMEC has developed dedicated exhibitions or thematic storylines that narrate the historical perspective of disability in ancient Egypt. Similarly, there are no exhibitions focusing on the lived experiences of disabled individuals from this era. Most responses highlight the significant progress that has been made recently in enhancing physical and intellectual access to museums for disabled visitors—such as the installation of a tactile path at the EMC and the organization of social events and performances accommodating disabled individuals at the NMEC (Zakaria 2023); a noticeable gap remains in the representation of disability within the content of their exhibitions.

While NMEC participants indicated that the museum has not yet organized an exhibition specifically focused on disability, the EMC has made some efforts to acknowledge the topic. Notably, EMC held a small-scale exhibition on International Disability Day, featuring a monthly one-object display highlighting an artifact related to disability. However, these initiatives remain limited and lack the depth of comprehensive storytelling. One of the EMC curators reflected on these efforts: “We haven’t created exhibitions that tell the story of disability in ancient Egypt, but we once organized an exhibition based on one artifact related to disability as part of our monthly one-object exhibition”. The curator’s comment highlights both the challenge and opportunity for EMC. While the museum has taken steps to recognize distality, there is significant potential to move beyond occasional displays towards a more sustained and integrated approach. Given the richness of the EMC’s collection, relying on a single artifact in a temporary exhibition falls short of fully exploring the histories and lived experiences of disabled individuals in ancient Egypt.

Another curator shared their experience: “On International Disability Day, we were supposed to present one object about disability, but we managed to present a whole dedicated showcase featuring disability artifacts, including new items not part of our permanent exhibits. Some fascinating artifacts related to disabled individuals were found in the Graeco-Roman collection, and several were displayed for the first time”. Building on this, another curator highlighted efforts to revise artifacts’ labels: “We revised the artifact labels to emphasize that individuals with disabilities in ancient Egypt lived similar to normal people and also mentioned that they had employment opportunities in the past”.

The discovery of relevant artifacts within the Graeco-Roman collection is particularly noteworthy. It suggests other hidden artifacts related to disability within the museum’s broader collection that need to be further researched, interpreted, and displayed. This finding also indicates that disability was a recognized aspect of life across various historical periods, opening up opportunities to develop exhibition content that explores cross-cultural comparisons and perspectives on the experiences of disabled individuals throughout ancient Egyptian history.

Study participants, mainly educators with disabilities, argue that while “disability is represented by objects in museum galleries, their stories are not reflected in the information provided alongside these objects or in the tour guides”. They stressed that incorporating museum objects to represent disabled individuals of the past more thoughtfully is essential for their work and the effectiveness of educational programs. From their perspective, disability remains underrepresented in exhibitions because developing storylines that highlight the lived experiences of disabled people is not currently a priority for museums.

4.3. Limited Interpretative Techniques

The lack of explanatory materials about disabled people and their lived experience in ancient Egypt is a significant issue across many national museums. Exhibition galleries often rely primarily on written labels and panels to provide context for disability-related objects, resulting in a minimal interpretive environment (Zakaria 2021, p. 32). According to EMC’s curators, “The labels and text panels are the main interpretive tools used in the majority of exhibition galleries”. Another curator commented, “We have recently updated some labels, such as those used with Old Kingdom statues of people with dwarfism”. However, one participant acknowledged, “Most disability-related objects have only labels as an explanatory tool, and some objects have no labels at all”. While these labels offer limited data, the absence of other interpretative materials significantly hinders visitors’ ability to engage or understand the social and historical contexts of the artifacts. Moreover, the presence of outdated or derogatory language in the labels raises additional concerns. Further, the two museum educators emphasized the absence of educational or public programs specifically created to involve the general public or school children in discussions about disability in ancient Egypt.

One of the NMEC’s curators reported, “NMEC is using audio-visual media and videos in addition to exhibition labels”. Among the artifacts related to disability displayed in the core gallery is a prosthesis belonging to an Egyptian lady who had to amputate one of her big toes due to arterial disease complications (Boonshoft-White 2022, pp. 79–80). The curator explained, “The museum collaborated with the Center for Documentation of Cultural and Natural Heritage (CULTNAT), affiliated with Bibliotheca Alexandrina, to produce an illustrative video about this prosthetic device and how advanced ancient Egyptian people were in prosthetic devices”. However, the video focuses on the design and technique of prosthetic devices in ancient Egypt without providing context about individuals with physical disabilities, their lived experiences, or the broader social impact of disability on their lives or work.

Moreover, the mummies displayed at NMEC are accompanied by CT scan images and X-rays that reveal the results of scientific analysis (National Museum of Egyptian Civilization 2022a). These displays provide a detailed visualization, allowing visitors to gain insights into the diseases and medical conditions of Egyptian rulers. However, this approach focuses heavily on the medical aspects while overlooking broader sociocultural and historical contexts.

Additionally, none of the study participants reported using visitor questionnaires or evaluations to gather feedback on the exhibition galleries, including those featuring disability-related objects. This lack of visitor engagement and evaluation tools limits the museums’ ability to assess how effectively their exhibits communicate narratives about disability and connect with diverse audiences.

5. Discussion

As revealed by the study findings, both museums include ancient Egyptian artifacts related to disability. The EMC houses an extensive collection directly linked to disability, encompassing statues, figurines, coffins, amulets, prostheses, and paleopathological resources such as mummies and human remains. While the NMEC does not have many artifacts related to disability from ancient Egypt, it does display unique and distinctive objects that provide meaningful context for understanding disability in ancient Egypt.

There is a consensus among all the study participants that national museums have both the potential and the capability to integrate disability representation and shed light on the underrepresented histories of disability from ancient Egypt. Participants believe that doing so would not only enhance public understanding of ancient Egyptian culture but also align with recent societal efforts to promote inclusion and support the rights of disabled people in society. The following section delves into the study results, highlighting key findings drawn from the author’s direct observations during fieldwork at the two museums, focusing on their displays and the interpretation provided through labels and panels.

5.1. Representation of Disability Context

While both museums possess artifacts relevant to disability history, these artifacts are neither incorporated into exhibitions or narratives that explore the lived experiences of disabled people nor utilized to stimulate societal dialogue about the contemporary perception of disability, whether in temporary or permanent galleries.

At the EMC, disability-related objects are arranged chronologically, which often scatters them across different historical periods. This approach makes it difficult for visitors to connect the stories or understand how disability was perceived and experienced throughout ancient Egyptian history. The display method prioritizes the factual information about the objects—such as date, provenance, and brief descriptions—over their broader social or cultural significance. Consequently, disability history remains invisible within the overarching narrative of ancient Egyptian galleries, lacking a cohesive storyline that invites visitors to reflect on the embodied experience of disabled individuals in the ancient past.

The NMEC, with its thematic approach, offers a promising platform for presenting disability histories. However, as the study revealed, despite the museum’s potential and its unique objects, disability is not integrated into any specific themes, sub-themes, or narratives. This reflects a broader trend in which museums, despite their rich collections, neglect to connect material culture with the experiences and voices of marginalized groups—such as disabled individuals in this case.

Despite the increasing global awareness regarding the significance of disability representation in museums as a social demographic, Egyptian museums have yet to incorporate this approach, instead placing their emphasis on accessibility, which remains an evolving practice (Zakaria 2025). Notably, the themes and narratives for museums under the MoTA—whether related to museum renovations, exhibitions, or new national museum projects—are primarily determined by the High Scientific Committee for Museum Scenarios, established by Ministerial Decree No. 214 of 2018 (Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities 2018). This committee is responsible for proposing narratives, creating curatorial briefs, and developing graphic and interpretative materials. However, its focus largely revolves around conventional themes concerning daily life and the afterlife in various Egyptian historical periods, often repeated across museum displays, with few exceptions. Unfortunately, the histories of disability and the cultural, social, and historical contextualization of the experiences of disabled individuals are neither prioritized nor emphasized within its agenda.

5.2. The Dominance of the Medical Perspective and Ableism in Egyptology

There is a significant gap in the representation of disabilities in Egyptian museums, as exemplified by the EMC and the NMEC case studies. The issue lies not only in the underrepresentation of disabled people in museum narratives and thematic topics but also in the way these representations are framed in the labels and text panels. The current interpretation adopts a medicalized perspective, focusing on the diagnoses and physical manifestations of disabilities—such as hunched backs, polio, or dwarfism—while neglecting the broader sociocultural contexts that shaped the lived experiences of disabled individuals in ancient Egypt.

This is largely due to previous research on disability in ancient Egypt having predominantly taken a medical perspective. Such studies have relied heavily on visual records and human remains to classify disabilities under terms like ‘deformities’, ‘diseases’, or ‘pathological conditions’ (Morris 2022, pp. 288–301; Vogel 2020, pp. 26–34; Vogel and Power 2022). This approach tends to overlook the embodied experiences, individual circumstances, and broader sociocultural dynamics that shape the lived conditions of disabled individuals. The Egyptology literature frequently ‘objectifies’ those with disabilities, neglecting their identities and cultural significance, which are fundamental for the comprehensive interpretation of the evidence (Vogel 2020, pp. 59–62).

Moreover, Egyptology scholarship tends to interpret ancient Egyptian resources through biased and ableist assumptions, leading to the marginalization of disabled individuals in Egyptological studies. Their lived experiences and stories remain hidden, overlooked, or oversimplified. Recent studies (Vogel 2020) have brought to attention the prevalence of ableist narratives and Eurocentric bias within Egyptology scholarship, which have been perpetuated in part by a reliance on Western medical diagnostics of ‘normative bodily standards’ and dichotomous of ‘abled-bodied’ versus ‘disabled.’ This perspective has also contributed to the exclusion of disabled individuals from historical narratives presented in museums (Morris 2022, pp. 288–301). Present interpretations mostly rely on medical and palaeopathological literature, viewing disability solely as an impairment condition. This reliance on the medical model of disability limits our understanding of disabled individuals in ancient Egypt, framing them within an abled/disabled binary that oversimplifies their complex lived realities.

5.3. Language Used in Labels and Text Panels

Typically, all panels, labels, and other written materials in the MoTA’s museums are presented in bilingual formats, Arabic and English (Zakaria 2021, p. 32), with a few exceptions, such as the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM), which includes Japanese in some exhibition labels (Zakaria 2024). Accordingly, the labels and panels at both the EMC and NMEC are bilingual, ensuring accessibility to Arabic- and English-speaking visitors. The language used in labels and exhibition texts to describe disabled individuals in EMC and NMEC reflects the medical and charity model of disability, portraying disabled people as victims in need of ‘pity’. Terms used in the labels often contain outdated and inappropriate language, particularly in Arabic, which can perpetuate discriminatory views. For instance, in the EMC, updated Arabic labels use expressions such as “afflicted with dwarfism” and “afflicted with kyphosis”. An example is the label accompanying a statue of a man with kyphosis (see Figure 5), where the Arabic version states, “… like this man afflicted with kyphosis”, referring to the statue’s owner. Such terminology considered inappropriate according to the practical guidelines for disability-inclusive language outlined by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) (United Nations 2024), which Egypt signed and ratified in 2008 (Zakaria 2020). Such terminology implies constant pain, powerlessness, and a poor quality of life, reinforcing negative stereotypes. By contrast, the English version reads, “… like this man with kyphosis”. This discrepancy highlights inconsistencies in the language used between the Arabic and English texts, further emphasizing the need for alignment, unified guidelines, and inclusive language in addressing disability terms in exhibition texts.

On the other hand, in the NMEC, the term ‘victim’ appears in both the Arabic and English versions of the label for King Siptah, stating that “he was a victim of poliomyelitis” (see Figure 9). This phrasing perpetuates the charity model of disability, framing the individual as passive and defined by their condition rather than acknowledging their agency or broader historical significance (see United Nations 2024).

Figure 9.

Label accompanying the display of the mummy of King Siptah, the mummy gallery, NMEC. (Photograph by Ahmed Romeih).

Using language such as ‘suffering from’, ‘afflicted with’ or ‘victim of’ reinforces negative stereotypes and depicts disabled people as pitiable or solely defined by their impairments. This kind of language not only perpetuates ableist perspectives but also marginalizes disabled individuals by presenting ‘disability’ as inherently negative physical suffering, thus reducing their identity to limited physical conditions instead of portraying them as active participants in ancient Egyptian society. For example, instead of referring to King Siptah as a ‘victim’ of poliomyelitis, the label could simply state that ‘King Siptah had poliomyelitis’ and follow this with more context about his life and how he ruled Egypt.

5.4. Study Limitation

When interpreting the findings of this study, it is important to consider several limitations. Firstly, it is worth noting that the study focused primarily on the EMC and the NMEC and did not encompass all national museums with ancient Egyptian collections. As a result, the findings should be viewed as a reflection of these specific museums rather than a comprehensive representation of all national museums, limiting the generalizability of the findings across other museums in Egypt that house ancient Egyptian artifacts related to disability.

Additionally, the study faced constraints related to the number of participants from these national museums, resulting in a small sample size. This limited number of participants does not fully capture the diversity of curatorial practices, perspectives, or experiences across different museums, particularly those not included in the study. Furthermore, there is a potential for response bias from the study’s participants, particularly curators, as their responses may have been influenced by various factors such as the policies and practices of their respective museums, personal understanding and perceptions of disability, or their interpretations of ancient Egyptian history. External factors like institutional constraints, professional experiences, or individual attitudes toward disability could have also shaped their responses, potentially affecting the study’s findings. Lastly, it is important to note that the study did not fully explore all the factors that might impact how disability is represented in museum exhibitions, such as financial limitations, institutional priorities, or governmental policies.

Nonetheless, this current study can act as a foundation for future studies on the representation of disability in Egyptian museums. It can also contribute to planning future actions and experimental practices in the MoTA’s national museums to integrate authentic cultural narratives about disabled people among their exhibitions, leveraging interpretations that draw upon historical and contemporary contexts to prompt the public to rethink their attitudes towards disability.

6. Future Avenues and Conclusions

In recent years, museums worldwide have increasingly undertaken projects, exhibitions, and initiatives dedicated to representing disabled individuals in both historical and contemporary contexts. The perspective of disability in ancient Egypt, evidenced by iconographic and textual resources, reveals a society that embraced disabled individuals as an integral and valued aspect of human differences (David 2016; Zakrzewski 2014). While some scholars suggested instances of exclusion based on visible bodily differences (Jeffreys and Tait 2000), a closer look at the perception of disabilities as divine blessings and their association with revered gods shows a notably unique view of disability. This perception, along with the richness of visual and textual representations, indicates that disabled individuals were neither stigmatized nor marginalized—an approach contrasting with contemporary Egyptian society, where stigmatization and prejudice prevail.

The topic at hand, supported by a wealth of materials related to disability, provides an opportunity for museums housing ancient Egyptian collections to engage communities in meaningful conversations about disability, away from the medicalized perspective and the dominant ableist and disabled assumptions in Egyptology. The global movement of ‘representing disability’ in museums advocates for ethical interpretive interventions drawing on the social model of disability. This approach challenges conventional perceptions and promotes progressive ways of rethinking disability (Delin 2002; Martins et al. 2018; Sandell et al. 2010; Tooke 2006).

Egyptian museums have an opportunity to contribute to this movement and expand their social engagement with disability issues. Egyptian museums, with their extensive ancient Egyptian collections—comprising 82% of national museum holdings, according to a recent study (Zakaria 2024)—are particularly well-positioned to contribute to this movement. These institutions can leverage disability-related artifacts, many of which are either on display or in storage, as a foundation for exhibitions, educational programs, and community events. By effectively communicating authentic disability narratives from ancient Egypt along with educational programs, museums can bridge historical and contemporary disability contexts, fostering meaningful public discourse and challenging negative stereotypes. Such initiatives can shed light on the barriers disabled individuals face in modern Egyptian society, influence societal attitudes and practices, and thus contribute to reshaping public perceptions of disability. To achieve meaningful representation of disability in Egyptian museums, two primary directions are essential.

6.1. Transitioning from Medical Intervention to More Social–Cultural Dimensions

Museums, as spaces for ‘shaping knowledge’, have the power to construct and communicate social values (Hooper-Greenhill 1992; Hooper-Greenhill et al. 2000). Whether through their collections, exhibitions, or narratives, they can influence how people view disabled individuals historically and today. If national museums such as EMC and NMEC provide representation that emphasizes disability solely from a medical perspective, they reinforce ableism and limit public understanding of disability. In contrast, if they offer contextual interpretations about disability in ancient Egypt that go beyond medicalized views, embrace sociocultural narratives reflecting the lived experiences of disabled individuals, and utilize interpretative methods and inclusive language to support this perspective, they can challenge prevailing stereotypes against disabled people in society. Moreover, they can empower disabled individuals by connecting them to a history that acknowledges their contributions and affirms their existence.

6.2. Curatorial Changes: Intersections with Disability Studies and the Integration of Voices from Disabled Individuals

The underrepresentation of the experiences and identities of disabled individuals reveals two significant gaps. Firstly, there is a lack of awareness among museum professionals/curators regarding the emergent practice of ‘representing disability’ in museums (Sandell et al. 2010) and the importance of incorporating narratives about disabled individuals, emphasizing their existence and historical contributions. Secondly, this reflects broader issues within Egyptology scholarship, which has predominantly focused on medical interpretation rather than sociocultural contexts. This has resulted in a lack of contextualization of the embodied experiences and identities of disabled people in historical studies and the Egyptological literature.

To address these issues, it is essential that national museums in Egypt—primarily the EMC and NMEC, which serve as the case studies—along with the responsible committee for museum scenarios and storylines, implement curatorial changes. These changes should focus on developing new narrative frameworks that encourage intersections with disability studies, ensuring the presentation of balanced and inclusive accounts of historical and contemporary contexts. This would allow for a reinterpretation of disability history in ancient Egypt and related artifacts. Since most museum curators are originally Egyptologists who studied Egyptian archaeology, their academic background in this field often leans heavily on traditional frameworks that may carry ableist assumptions and modern biases. By adopting a more inclusive, balanced approach to re-examining historical perspectives, these museum professionals can develop new concepts and storylines that provide nuanced, multidimensional interpretations of disability, moving beyond the dominant medical and one-dimensional narratives typically found in Egyptology. One promising avenue for this shift is the collaboration between Egyptian museums and disability agencies. A compelling example of such collaborative efforts is the work of the Greater Manchester Coalition of Disabled People (GMCDP) in the UK, which has developed initiatives in collaboration with museums to document, re-examine, and exhibit the history and lived experiences of disabled individuals. Their long-term project, Nothing About Us Without Us, which looks at the representation of disabled people (People’s History Museum 2022), highlights personal narratives and actions carried out by disabled people to break down barriers and political and cultural movements, reframing disability from a marginalized perspective to one of empowerment and agency. Drawing on such models, Egyptian museums could partner with local disability organizations to co-create narratives of disabled people, shaping their histories and challenging stereotypes that move beyond medicalized or ableist lenses. These partnerships could foster exhibitions that reflect the lived experiences of disabled individuals while bridging ancient and contemporary perspectives, making museum displays more inclusive for all audiences.

By integrating the expertise and voices of disability advocates into the curatorial process, museums can ensure that exhibitions employ inclusive concepts and respectful language across labels, panels, websites, and other media. This collaboration would provide a platform for diverse voices to be reflected in museum narratives, contributing to more authentic representations of disabled individuals from ancient Egypt. This will also help make the exhibitions more relevant and meaningful to disabled communities.

The EMC and NMEC have a unique opportunity to lead the way in current curatorial practices by representing narratives connected to disability in ancient Egypt in their exhibitions and developing guidelines for ethical interpretative methods. As the flagship institution of Egyptian museums, the EMC has historically set standards for museological and scientific practices. The NMEC, through its recent success in engaging with the disabled community via programs and initiatives, has laid a solid foundation for further inclusion efforts (Zakaria 2025). Both museums have established partnerships with disability-related organizations and NGOs, positioning them to pioneer experimental practices in representing disability within their exhibitions. Their leadership has the potential to inspire other museums under the MoTA to follow suit. This approach can encourage experimental practices in other national museums with pharaonic collections to integrate representations of disabled people’s lived experiences from ancient Egypt into their exhibitions (online and physical), reinterpret material evidence related to disability within their diverse collections, and communicate/curate narratives of disabled people in their exhibitions.

By adopting the ‘Re-presenting Disability’ approach with new interpretive interventions that are developed in cooperation with distality organizations and advocators, the EMC and NMEC can significantly engage with social discussion about disability and contribute to reshaping public perceptions of disability in Egyptian society. For example, by highlighting the historical figure of King Siptah, NMEC has the opportunity to convey a powerful narrative: disability did not hinder an individual’s ability to ascend the throne and rule Egypt. This story can challenge contemporary stereotypes and promote the idea that disabled individuals, both historically and today, possess the capability to lead and contribute meaningfully to society. Incorporating such narratives from ancient Egypt that have always been a source of national pride for all Egyptians can inspire the public to rethink traditional perceptions of disability, fostering greater awareness and inclusion.

Funding

This study was conducted as part of my Alexander von Humboldt Post-Doctoral Fellowship at the University of Würzburg. The article processing charge (APC) was funded by the Open Access Publication Fund and the Museology Department of the University of Würzburg.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study as local legislation and institutional requirements do not mandate such procedures.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included within the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I would like to sincerely acknowledge all the research participants who generously shared their time and insights from their experiences in the museum field. Their contributions have been invaluable to this research, and I am deeply grateful for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdel Moniem, Ayman. 2005. The National Museum of Egyptian Civilization. Museum International. Heritage Landscape of Egypt 57: 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- American Alliance of Museums. 2002. Mastering Civic Engagement: A Challenge to Museums. Washington, DC: American Alliance of Museums. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Gail. 2004. Introduction. In Reinventing the Museum. Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on the Paradigm Shift. Edited by Gail Anderson. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Aufderheide, Arthur C., and Conrado Rodríguez Martín. 2011. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Paleopathology, 1st paperback ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, Colin, and Geof Mercer. 2010. Exploring Disability: A Sociological Introduction, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, Colin, Geof Mercer, and Tom Shakespeare. 1999. Exploring Disability. A Sociological Introduction. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bayer, Natalie, Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński, and Nora Sternfeld, eds. 2017. Kuratieren als Antirassistische Praxis. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Tony. 1995. The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]