Abstract

This study explores the phenomena of group polarization and echo chambers within the context of online discussions among immigrants in Japan, also known as gaijins, specifically within the #GaijinTwitter community. By analyzing the key topics discussed by divergent groups of Twitter users and examining their interactions through qualitative and quantitative approaches, we provide evidence of group polarization. Additionally, we investigate how blocking and sharing screenshots of tweets instead of reacting to them in the standard ways contribute to the formation and perpetuation of online echo chambers.

Keywords:

group polarization; echo chamber; social media; Twitter; immigrants; Japan; #GaijinTwitter 1. Introduction

The exploration of group polarization and echo chambers transcends the realm of politics and extends to discussions across various domains. These phenomena can manifest in discussions encompassing a wide array of topics, ranging from social issues and cultural debates to scientific controversies and consumer preferences. The underlying mechanisms driving group polarization and the formation of echo chambers remain pertinent regardless of the subject matter under discussion. Therefore, investigating these phenomena in a broader sense provides valuable insights into human behavior and communication dynamics across diverse contexts.

As detailed in the literature review, researchers have explored a wide range of topics to investigate potential group polarization and echo chambers. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have specifically examined polarization and echo chambers in the context of immigration or immigrant-related issues in Japan. This gap in the literature highlights a crucial area for investigation, given the unique social and political landscape of Japan.

This study delves into group polarization and echo chambers within the context of online discussions among immigrants in Japan, often referred to as gaijin, focusing specifically on the #GaijinTwitter community. Through a combination of qualitative and quantitative analyses, we examine the key topics discussed by two divergent groups of Twitter users and explore the nature of their interactions. Our findings provide compelling evidence of group polarization within this digital space, highlighting how distinct groups engage with shared topics yet remain ideologically or socially fragmented.

Furthermore, we investigate the role of specific online behaviors—such as blocking and the practice of sharing screenshots of tweets instead of engaging directly through likes, retweets, or comments—in shaping and sustaining echo chambers. These behaviors not only limit cross-group interactions but also reinforce pre-existing biases by restricting the visibility of opposing viewpoints. By situating our analysis within the broader literature on digital communication, homophily, and social polarization, this study sheds light on the implications of online discourse for immigrant communities, social cohesion, and the broader dynamics of polarization in the digital age.

In particular, we inquire in this study whether group polarization and echo chambers are observable phenomena within the #GaijinTwitter community. To guide the development of our methodology, we propose the following research questions:

- RQ1: To what extent are the interactions within the #GaijinTwitter community evidence of group polarization?

- RQ2: What are the prominent contemporary topics under scrutiny within these discussions?

- RQ3: Can it be argued that the culture of social blocking within the #GaijinTwitter community effectively contributes to the establishment and reinforcement of echo chambers?

In particular, we are providing evidence of polarization (RQ1) and then additionally providing an innovative analysis of echo chamber formation using social blocking data (RQ3). This can be considered important since echo chambers can contribute to polarization.

Recent changes to Twitter’s API policies have significantly constrained large-scale data collection, presenting challenges for researchers studying online interactions. While data collection for this study initially relied on traditional methods, these limitations prompted us to innovate by developing and proposing a novel framework for locally storing and processing Twitter data. This framework enables the collection and analysis of smaller-scale datasets, particularly focusing on unique behaviors such as blocking and screenshot sharing—practices that play a central role in the formation and reinforcement of echo chambers.

A key contribution of this study lies in the integration of quantitative and qualitative approaches. Quantitatively, we analyze the interaction map to uncover patterns of polarization between user groups, revealing structural and behavioral divides. Qualitatively, we incorporate a rich analysis of tweet screenshots, including tweet content, memes, and visual elements, to provide deeper insights into the narratives shaping online discourse. This dual approach, particularly the emphasis on blocking and screenshot sharing, represents a novel methodological contribution to echo chamber studies and forms the core innovation of this work.

In order to provide a clearer context and establish a solid foundation for understanding the underlying causes and aspects of polarization and echo chambers, we will first present a concise review of the literature on immigration issues and the political discourse surrounding them in Japan. This review will offer essential insights into how these factors may intersect and influence the formation of polarized communities and echo chambers within the Japanese context. We will then review the definitions of fundamental concepts, including homophily, polarization, and echo chambers, along with the related literature.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Immigrant Issues in Japan

Challenges faced by individuals living in countries other than their own, encompassing refugees, immigrants, and permanent residents, represent one of the most pressing global issues of recent times. While studies have delved into the fragmentation of anti-refugee sentiments, as examined by Yurtcicek Ozaydin (2018), there is still a lack of thorough study particularly concerning immigration issues.

This gap in research extends to various contexts, including the case of Japan, where the dynamics of immigration and integration present unique challenges and complexities that warrant closer examination. According to Kyodo News (2024) and The Mainichi News (2024), the number of foreign residents in Japan has recently reached 3.4 million, accounting for 2.7% of the total population. Almost 900 thousand residents hold permanent residency. The top three countries that the largest populations of foreign residents are coming from are China, Vietnam, and South Korea, with approximately 821 thousand, 565 thousand, and 410 thousand, respectively.

Indeed, according to Kotomi (2020) on Nippon.com, while individuals living in Japan without Japanese citizenship are technically referred to as “gaikokujin”, which may not inherently carry a xenophobic connotation (see Asahina and Higuchi (2020), for example, on xenophobia in East Asia), the same cannot be said for the shortened version of the word, “gaijin”, in daily life. Many Japanese people perceive the use of “gaijin” as impolite and prefer to adhere to the term “gaikokujin”. However, many foreigners residing in Japan, irrespective of their visa or citizenship status, do not have reservations about using the term gaijin. They even use the hashtags #GaijinTwitter or #GaijinWars on Twitter.

As will be detailed below, the goals and aims of this work is to examine the #GaijinTwitter community. Focusing on contemporary topics and discussions in these topics, we ask whether group polarization and echo chambers are phenomena that can be observed clearly within the #GaijinTwitter community.

In this study, we identify hot topics attracting intensive discussions around immigrant issues in Japan. For analyzing the interactions, we select a number of Twitter users who are highly active in these discussions and collect their relevant tweets. Almost all of the users in consideration are foreigners, or “gaikokujins”. Since we are retrieving public data on Twitter but not having one-to-one discussions or consented interviews, we are not disclosing their personal information but rather protecting their privacy by censoring their Twitter screennames, profile pictures, and so on. Each user under consideration is potentially different in various aspects from others, including age, nationality, residence status, profession, and even migration path. Their common attribute that we are examining in this study is being a “gaikokujin” and being active in the discussions on the identified topics.

Also, we are not focusing on the particular political ideologies of the selected users yet not ruling out the potential to infer it from the contents of their tweeets or their interaction patterns. This approach is similar to the above-mentioned study of Yardi and Boyd (2010), where group polarization was studied based on discussions with two hashtags prominent about a particular topic, though the political leanings of the subjects can be inferred from their tweets.

The gaijin-related issues in Japan have garnered attention from researchers across various contexts. For example, Arudou (2017) examined “The Underground Files of Gaijin Crime”, also known as “Gaijin Hanzai Ura Fairu” in Japanese, depicting foreigners in a pejorative manner as ‘dangerous’ and ‘evil’. This study shed light on the collective endeavors of non-Japanese residents in Japan, comprising a diverse cohort with multifaceted backgrounds and linguistic diversity. They unified to assert their rights in a case largely disregarded by the Japanese media. Moody (2014) employed an interactional sociolinguistics framework to analyze discourse data collected from a two-day observation of an American intern at a Japanese corporation. The dataset revealed the use of English and humor by the intern and his peers, collectively constructing a ‘gaijin’ or ‘foreigner’ identity, fostering positive interpersonal dynamics and social outcomes. These findings show how using diverse cultural backgrounds helps to bridge language and social gaps, improving communication and relationships in multicultural workplaces. These findings illustrate how diverse cultural backgrounds and linguistic practices can play a crucial role in shaping social dynamics and perceptions of identity in Japan. While Arudou (2017) highlights the collective activism of non-Japanese residents against discriminatory portrayals, Moody (2014) demonstrates how language and humor can be employed to navigate and construct a positive ‘gaijin’ identity within a corporate setting. Together, these studies underscore the complex interplay between language, identity, and social integration in Japan’s multicultural landscape.

Schmid and Roedder (2021) suggested that foreign ownership significantly influences the representation of foreign directors on boards. Drawing from resource dependence theory, they argue that firms dependent on foreign owners perceive foreign nationals as valuable assets. Their research found that firms regard the inclusion of foreign directors as a strategic response to the divergent expectations of foreign owners, viewing them as a means to align with the preferences and demands of these stakeholders. Shin et al. (2024) explored the experiences of foreign migrants who arrived in Japan during the 2000s, aiming to investigate the correlation between their daily anxieties and discomfort and the prevalence of prejudice and discrimination. Framing their analysis around the axes of direct and indirect prejudice experienced by foreigners, the study seeks to elucidate these nuances. Shircliff (2024) delved into the intersection between lifestyle migration to Japan and the entrenched organizational norms of native speakerism and capitalist exploitation. This investigation underscores the intertwined dynamics of lifestyle migration and native speakerism within organizational frameworks, revealing the ostensibly ‘win-win’ agreements with labor that perpetuate ideological reproduction within the material landscape. The intricacies and obstacles faced by asylum seekers in Japan have been extensively examined in a recent study by Suzuki (2023), which delves into the concept of precarity within this demographic. These studies collectively highlight the complex landscape of foreign involvement and experiences in Japan, from corporate governance to individual lived experiences. While Schmid and Roedder (2021) emphasize the strategic value of foreign directors in aligning with the expectations of foreign stakeholders, Shin et al. (2024) reveal the everyday challenges faced by migrants due to prevalent prejudice and discrimination. Additionally, Shircliff (2024) explores how lifestyle migration intersects with organizational norms, shedding light on the reproduction of ideological frameworks within the labor market. Meanwhile, the precarious conditions faced by asylum seekers, as discussed by Suzuki (2023), further underscore the broader social and economic challenges that accompany foreign presence in Japan.

Let us focus on the cultural and political aspects regarding immigrants and immigration issues in Japan. According to Liu-Farrer (2020), on the one hand, Japan is an “emerging immigrant destination”. On the other hand, being an “ethno-nationalist society”, linked to the myth of Japanese ethnic homogeneity, it is denying immigrants. Also, the social and cultural aspects of Japan not only attract but also deter potential immigrants.

The growing influx of migrants in East Asia marks what Asahina and Higuchi (2020) identify as the third round of migrant incorporation, characterized by persistent ethnic nationalism that challenges the development of multicultural societies. This trend is particularly evident in Japan, where, as Liu-Farrer (2020) argues, the deeply rooted ethno-nationalist identity poses significant barriers to immigrant integration. Despite Japan’s increasing reliance on foreign workers to counter its rapidly aging population and shrinking workforce, the nation’s adherence to cultural and ethnic homogeneity, embodied in discourses such as nihonjinron (theories of Japanese identity) and tan’itsu minzokuron (the myth of Japanese ethnic homogeneity), continues to hinder the full incorporation of immigrants into Japanese society. As Asahina and Higuchi (2020) note, the limits of multiculturalism in East Asia, particularly in Japan, are shaped by these enduring features of the developmental state. Liu-Farrer (2020) further elaborates on this by documenting how Japan’s ethno-nationalist identity results in a discursive denial of immigration, leading to a lack of institutional and structural support for the integration of immigrants. This creates a paradoxical situation where, despite the growing numbers of immigrants, Japan struggles to provide them with equal opportunities and a sense of belonging. Both Asahina and Higuchi (2020) and Liu-Farrer (2020) emphasize the need for a more open dialogue on immigration and multiculturalism in East Asia and Japan. As Japan increasingly becomes an immigrant destination, as Liu-Farrer (2020) suggests, overcoming the challenges posed by its ethno-nationalist identity will be crucial. The intersection of these works underscores the unique yet ordinary nature of migrant incorporation in East Asia, highlighting the complex dynamics of polarization, multiculturalism, and nationalism in the region.

According to Higuchi (2024), nationalism influences immigration policies in Japan, with policymakers often cautious to avoid arousing nationalist sentiments. While ethno-nationalist attitudes prevail, nationalism is not the primary driver of migration policies. It is argued that examining factors that mitigate nationalist tendencies, such as decolonization, human rights, blood ties, labor needs, and merit-based principles, sheds light on the complexities of immigration policy-making in Japan despite strong nationalist sentiments. A study by Laurence et al. (2022) examines the impact of immigration on public sentiment toward immigrants in Japan, using longitudinal data to track changes in perceived threat and interaction levels. It aims to test whether Western theories on immigration attitudes are applicable in Japan and to understand the factors influencing positive or negative perceptions of immigrants. Findings indicate that increased immigration in an area correlates with heightened negative sentiments due to perceived threats. However, greater contact with immigrants reduces these negative feelings, suggesting that while immigration can initially foster negativity, personal interaction tends to improve attitudes, aligning with Western research outcomes. These findings underscore the nuanced interplay between nationalism and immigration in Japan. While the former argues that nationalism shapes but does not solely drive immigration policies, it emphasizes the importance of factors like decolonization, human rights, and labor needs in mitigating nationalist sentiments. Meanwhile, the latter provides empirical evidence that increased immigration can initially heighten negative public sentiment, but personal interactions with immigrants often improve these attitudes over time. Together, these studies reveal the complexities of immigration policy-making and public sentiment in Japan, where nationalist tendencies are both a significant factor and a challenge to be managed.

Tokyo offers a unique case study on the integration of transnational migrants due to recent migration policy changes and economic strategies aimed at diversifying the city’s population. This includes welcoming lower-skilled labor and global professionals. The work of Yamamura (2022) examines how newer, upper-class transnational corporate migrants integrate into urban areas, highlighting different socio-spatial patterns compared to earlier migrant generations. They reveal dynamics of inclusion and exclusion in Tokyo’s urban landscape and provide insights into the city’s evolving role in the global trend of urban superdiversification.

While there is debate about whether attending college in North America and Western Europe fosters pro-immigrant views, less is known about this effect in Japan. With rising foreign worker numbers and increased university enrollment, Kato and Lu (2023) explore the link between higher education and Japanese attitudes toward immigrants using 2009 and 2022 survey data. Findings indicate that although college education is generally associated with positive views on immigration, this link is weaker for those who attended college in the 1990s and 2000s. This suggests that the influence of higher education on immigration attitudes varies significantly outside Western contexts. Sato (2021) examined how young individuals in Japan, who identify as fully Japanese, are often labeled as mixed-race or non-Japanese due to their appearance. This mislabeling arises from rigid perceptions of Japanese identity and leads to exclusion and differential treatment. The study highlights the confusion and efforts to understand these ‘differences’. It suggests that marginalizing and labeling diverse groups as not fully Japanese helps society avoid challenging its definition of Japanese identity. Recognizing diversity within the Japanese majority is crucial to addressing exclusion. Davison and Peng (2021) examined factors influencing immigration attitudes in Japan, distinguishing between material and identity concerns. Based on interviews with 28 local residents and leaders in Yamanashi Prefecture in 2015, widespread opposition to immigration, except for care workers, was found. Identity-related worries mainly drove anti-immigration sentiment, whereas support for care worker immigration stemmed from material considerations. Our findings reveal a ‘pragmatic divergence’ where strong material concerns can outweigh identity-based ones. These studies shed light on the complexities surrounding immigration attitudes in Japan, particularly in relation to education, identity, and material concerns. While Kato and Lu (2023) reveal that higher education tends to foster more positive views on immigration, this effect varies depending on the era of college attendance, indicating a distinct context compared to Western countries. Sato (2021) further explores the rigid perceptions of Japanese identity, highlighting how labeling and exclusion of individuals based on appearance perpetuate a narrow definition of what it means to be Japanese. Meanwhile, Davison and Peng (2021) underscore the pragmatic divergence between identity-related opposition and material support for immigration, particularly in the context of care workers, emphasizing the complex factors that shape public sentiment toward immigration in Japan.

Japan, facing population decline, historically relied on the technical intern program (TITP) for low-skilled migrant workers. However, mounting criticism and economic pressures led to the introduction of the Specified Skilled Worker (SSW) program in 2018, allowing access to new sectors and longer stays. Roberts and Fujita (2024) examined stakeholders’ perspectives, particularly in agriculture, on these changes and their implications for the future of low-skilled labor migration. While businesses need labor urgently, they approach the SSW program cautiously, revealing contradictions in Japan’s migration policies that prioritize ‘skilled’ labor.

Recent research suggests that fiscal concerns significantly shape public opinions on immigration, with expert opinions playing a crucial role. Survey experiments conducted by Kage et al. (2022) in Japan indicate that citizens are more responsive to experts warning about negative fiscal impacts than to suggestions of positive economic or cultural benefits. This responsiveness persists across various demographic groups, including well-educated individuals, wealthier respondents, and younger respondents. A follow-up survey conducted four years later confirms these findings and identifies macro-level variables influencing the effectiveness of expert cues in shaping public attitudes towards immigration.

2.2. Group Polarization and Echo Chambers

Homophily refers to the tendency of individuals to associate and bond with others who are similar to them in terms of certain attributes, such as beliefs, values, or social characteristics. In online political communications, homophily manifests when individuals preferentially connect with and consume information from others who share similar political ideologies, leading to the formation of like-minded communities, as highlighted by McPherson et al. (2001), Sunstein (2001), and Flaxman et al. (2016). In the realm of online communication, it plays a crucial role in the development of polarized communities, where individuals are exposed predominantly to information and viewpoints that reinforce their pre-existing beliefs. According to Conover et al. (2011), this selective exposure can contribute to the formation of echo chambers. Due to this importance, the cross-national differences in partisan selective exposure have been recently analyzed by Kobayashi et al. (2024) among the US, Japan, and Hong Kong, and they were clearly observed only in the case of the US.

As pointed out by DiMaggio et al. (1996), the term “polarization” is usually used in the context of politics and it denotes the escalating divergence of political viewpoints over time. In the context of deliberative democracy, neither an absence of polarization nor excessive polarization is deemed desirable. Instead, according to the law of group polarization of Sunstein (1999), the aim is to cultivate a society of well-informed citizens who not only tolerate but actively engage with diverse stances. Moderate polarization can facilitate the synthesis of conflicting political ideologies, thereby enriching democratic discourse. When social networks effectively serve this purpose, democracy is strengthened. However, a substantial body of research indicates the contrary, suggesting that polarization may undermine democratic ideals. Furthermore, Giacomini and Paura (2023) showed that polarization is recognized as a catalyst for fostering reasonable democratic pluralism, although it may necessitate remedial actions if it escalates to a problematic extent. Identifying users’ stances has been a crucial step in examining group polarization, as demonstrated in studies such as Aldayel and Magdy (2022); Lai et al. (2019); Westfall et al. (2015).

The common dictionary definition of “echo chamber”, as explained by Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary (2024), describes settings where people mostly hear opinions similar to their own, which strengthens their existing views without considering different perspectives. According to Lazarsfeld (1954) and to Colleoni et al. (2014), this phenomenon is observed both in face-to-face interactions and online communications, respectively, where individuals often engage with like-minded individuals, contributing to the perpetuation of their shared beliefs.

Classic examples of offline echo chambers include school classrooms or company meeting rooms as discussed by Lazarsfeld (1954), where individuals, despite having the opportunity to interact with those holding diverse perspectives, may predominantly engage with others who share similar viewpoints. This dominance of interactions within similar-minded groups serves as evidence of the existence of offline echo chambers.

In contrast, online echo chambers, while sharing similarities with their offline counterparts, exhibit greater complexity due to the expansive reach and diverse nature of online communication platforms. Unlike face-to-face interactions, online communications are not constrained by physical proximity or limited audience size. Consequently, online echo chambers encompass a broader spectrum of participants and interactions, contributing to their increased complexity compared to offline echo chambers.

The question of whether social media leads to group polarization and echo chambers, or instead promotes diverse viewpoints, is crucial. Numerous researchers, including Matakos et al. (2017) and Chitra and Musco (2020), have endeavored to address this issue through purely mathematical frameworks. Some researchers built advanced mathematical models for analyzing the empirical data. For example, Barberá (2015) developed a Bayesian model for estimating ideal points for large samples of Twitter data from several countries, and Colleoni et al. (2014) employed machine learning for classifying the political orientation of Twitter and measuring homophily. Concurrently, a plethora of studies by Yurtcicek Ozaydin and Nishida (2021) have sought empirical evidence to shed light on this phenomenon, such as detecting echo chambers in political youth organizations and investigating political polarization on Twitter by analyzing how the interactions shape the public sphere.

Advanced techniques have been developed for analyzing the impact of social bots by Ferrara et al. (2016), for large datasets for examining elections by Najafi et al. (2024), and for language training models by Najafi and Varol (2024), while polarization due to misinformation on Twitter regarding the 2017 Elections in Japan is also being examined by Usui et al. (2018). Very recently, echo chambers have been studied by Toriumi and Yamamoto (2024) within the context of informational health, and potential ways for mitigation of such risks have been discussed.

A seminal work in the field, which explores group polarization based on tweets on a specific topic and serves as a motivation for the present study, is as follows. In the aftermath of the shooting of late-term abortion doctor George Tiller, two categories of hashtags emerged: neutral, such as #Tiller, and non-neutral, including #pro-life and #pro-choice. Analyzing around 30 thousand tweets and examining group polarization based on the replies exchanged among these tweets, Yardi and Boyd (2010) discovered that group identity is reinforced through interactions among like-minded individuals, while group affiliations are strengthened through exchanges between individuals with differing viewpoints. Their study found that responses between people with similar views strengthen group identity, whereas interactions between individuals with divergent views reinforce distinctions between in-groups and out-groups. While people are exposed to a broader range of viewpoints than before, their ability to engage in meaningful discourse is constrained. The findings have implications for various forms of social participation on Twitter and underscore the complexities of online interactions.

3. Methods

Our approach employs a hybrid methodology that integrates both qualitative and quantitative analyses. On the qualitative side, we examine the content of selected tweets, illustrating key points through carefully chosen screenshots. Meanwhile, the quantitative aspect focuses on analyzing the interaction map between two distinct user groups, leveraging techniques to uncover patterns and relationships. This dual approach enables a comprehensive exploration of the polarization and echo chambers within the #GaijinTwitter community, as elaborated in the sections below.

A pivotal consideration in shaping the methodology of this study was the evolving policies of X (formerly known as Twitter). Subsequent to these policy adjustments, the feasibility and practicality of retrieving extensive Twitter data through its API, contingent upon the research context and available resources, have notably diminished compared to previous circumstances. Previously, the acquisition of vast tweet volumes and subsequent dataset creation facilitated relatively straightforward analyses. However, present conditions necessitate a shift towards a more comprehensive set of pre-actions, such as specification determination and categorization, prior to data retrieval.

It is important to highlight that a significant and relatively new type of data utilized in this study have never been available through the Twitter API: screenshot sharing (as will be elaborated later) rather than retweeting, where a user captures a screenshot of another user’s tweet and shares it as an image. Therefore, our data collection method extends beyond merely adapting to changes in Twitter’s policies and API.

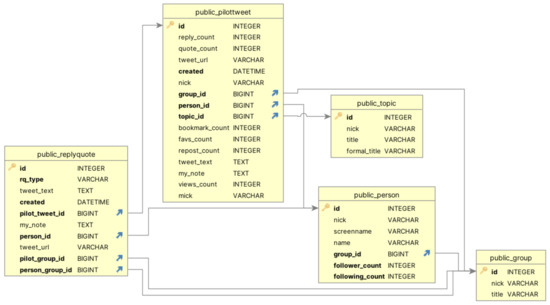

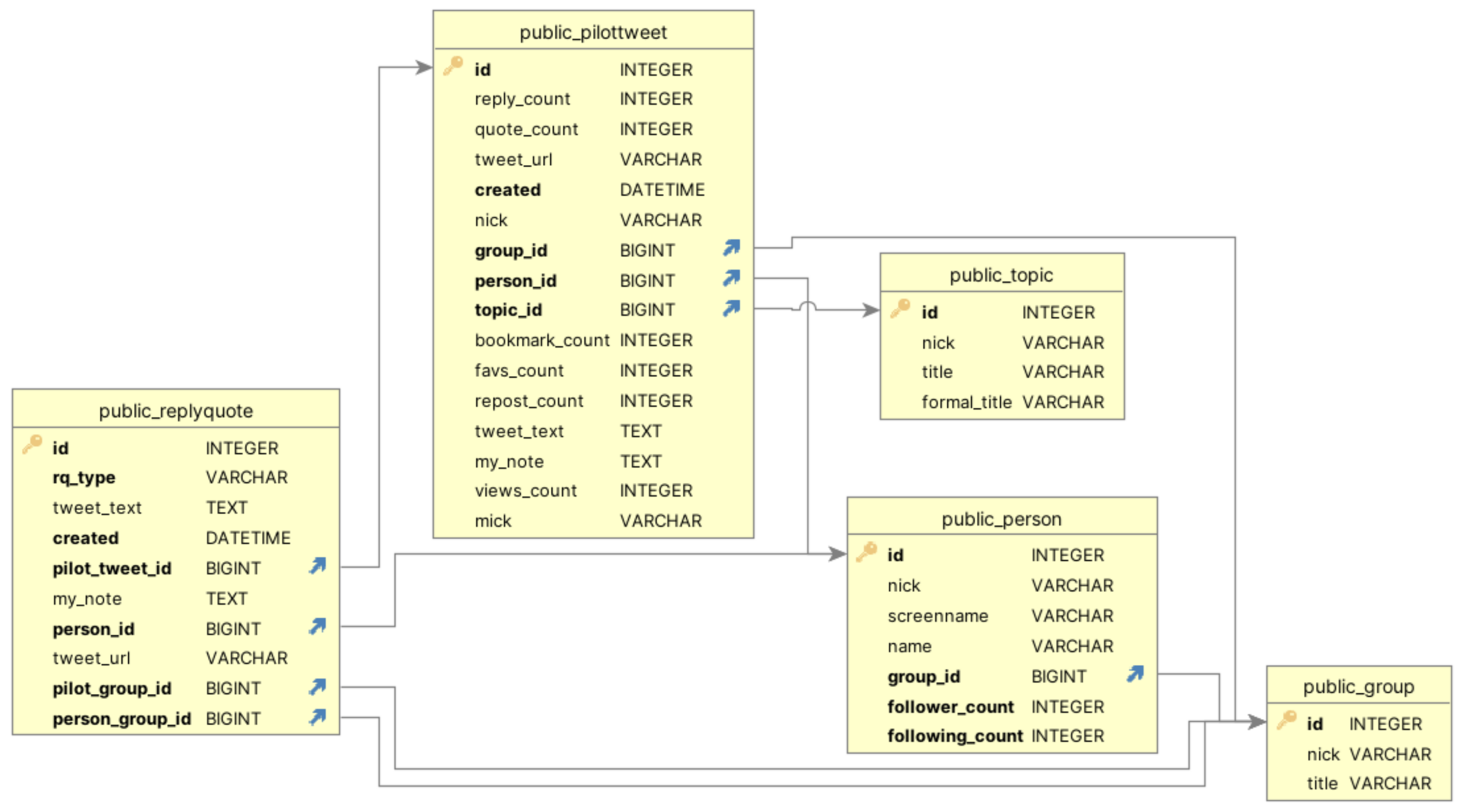

In alignment with this trajectory, alongside highlighting the principal contributions of this study, we present our method as an exemplar for the contemplation of scholars seeking a simple yet potent framework for managing, processing, and querying data retrieved from social network platforms. To establish and administer the database, we employed Django 5.0, the web framework designed for the Python programming language, with Python version 3.11.5. SQLite is chosen for the database due to its simplicity and portability. As outlined in the Data Availability Statement, the database file including the tweet data will be made available to scholars upon reasonable request. Below, we outline the data categories to be maintained, along with their corresponding tables. We also present the entity relationship diagram in Figure A1 in Appendix A.

It is important to note that the following steps do not represent a straightforward linear process of first Step A, then Step B, and then Step C. Instead, they involve a more complex process with feedback mechanisms. For example, “users” cannot be identified independently of “topics” or “tweets”, and vice versa. Hence, the identification of data in each category provides valuable insights into identifying data in other categories.

3.1. Identifying Stances Leading to Formation of User Groups

Given that the core of this research focuses on detecting and analyzing group polarization, as well as investigating the potential formation of echo chambers within these groups, the first step in our methodology is to identify the two distinct stances around which users tend to cluster. Given that this research focuses on two opposing stances, it aims to uncover a bipartite interaction network, where users primarily interact with others within their own group.

This step involves a thorough manual examination of the discussions under study, creating provisional lists of topics, users, and other relevant data. These lists are subject to refinement in subsequent steps, which will focus on highlighting the two opposing stances.

3.2. Topics

The next phase of this research is the identification of contemporary topics that prominently contribute to the formation of polarization and echo chambers to address the second research question (RQ2) of this study. This phase involves following many Twitter users potentially relevant to this study; searching for specific hashtags; examining, classifying, and aggregation of interactions; preparing provisional lists for topics appearing as the best candidates for providing insights; and others. Although the selected topics are potentially related, since the topics are utilized for selecting specific Tweets in order to analyze the interaction map, no categorization is considered for the topics.

3.3. Users

This step is to identify users who are both the authors of the tweets to be selected and the creators of reactions to the selected tweets. In other words, this phase entails identifying users who significantly contribute to the discussed topics under examination in both ways. Therefore, this stage also requires a thorough manual examination of the discussions. Based on their stance, each user is to be associated with one of the two groups.

3.4. Tweets

Along with identifying the groups, topics, and users who significantly contribute to the discussions, the next step involves carefully choosing a set of tweets from these users in these topics, which have received a lot of attention. The content of these tweets, encompassing both text and images, will illuminate the potential group polarization.

3.5. Interactions

This is the step that will lead to an answer to the research question (RQ1) on group polarization. While, similar to the tweets, the content of the interactions is expected to shed light on the polarization, the interaction pattern will provide a clear picture of a potential echo chamber. In particular, the percentage of interactions from users in each group to the tweets of each group will show whether users are interacting mostly with the tweets of the same or the opposite group. These interactions include {Fav, Reply, Quote, Repost}.

Following the retrieval of interactions, the subsequent step involves data visualization. To facilitate a comparative analysis of interaction volumes, we choose to position the tweets at the center of the figure, with users from groups A and B on the left and right sides, respectively. By drawing arrows from each user to a specific tweet, the magnitude of interactions becomes readily apparent. Moreover, these arrows are color-coded to signify the type of interaction. Given the substantial empirical nature of this research concerning the contents of tweets, screenshots of relevant tweets selected from a comprehensive dataset will be presented where applicable. To safeguard privacy, user screennames, profile pictures, and other sensitive information will be censored in the screenshots. Throughout the text and tables, Twitter users in consideration will be referred to as {A1, A2, … A6, B1, B2, … B6}. Also, gender-neutral phrases such as “they” and “their” will be used.

3.6. Social Blocking

In order to answer research question RQ3, we collect and analyze the data on blocking. However, X, or formerly Twitter, does not provide the blocking information in a systematic or automated way. Therefore, our manual process will be based on studying the tweets of the users involved to find evidence of social blocking.

In particular, we manually scan the tweets of the selected users in two groups within the last 12 months looking for any information (i) on blocking the users in the other group and (ii) on a systematic blocking behavior. When a user finds out that they are blocked by another user, especially in the other group, they might be taking a screenshot and sharing this screenshot in a tweet. Such tweets contain valuable information for our study.

In addition to blocking a particular Twitter user, we search for evidence of an interesting type of “social blocking”: When a user reacts to a tweet in any standard way, the author of that tweet and their (non-blocked) followers can see that reaction. However, a user might choose to react in a partially hidden way by taking the screenshot of a target tweet and then tweeting that screenshot with some comments as the reaction. This way, unless the author of the target tweet or the followers of that author checks the tweets of that user, they will not have a chance see this reaction. Since such a deliberate action can potentially contribute to forming and enforcing echo chambers, we look for evidence of such tweets as well.

The tweets found during the manual scan that fall into either category are saved in the local database for analysis as presented in the Results section.

Among these tweets observed manually, some contain interesting and valuable images that can improve our understanding of group polarization and echo chambers. Such images are saved in the database, and a few of them that we find the most interesting will be presented in the Results.

4. Results

Two distinct groups of Twitter users, denoted as groups A and B, naturally formed around similar viewpoints. We can see from their tweets that members of Group A tend to criticize the views of Group B on Japan and its society. The main topics discussed in this discourse are listed below and summarized in Table 1. It is noteworthy that while certain topics, such as social blocking or ALT, have been discussed in various contexts, since our focus primarily centers on these issues within the #GaijinTwitter context, the tweets and interactions about these topics are selected accordingly.

Table 1.

Topics.

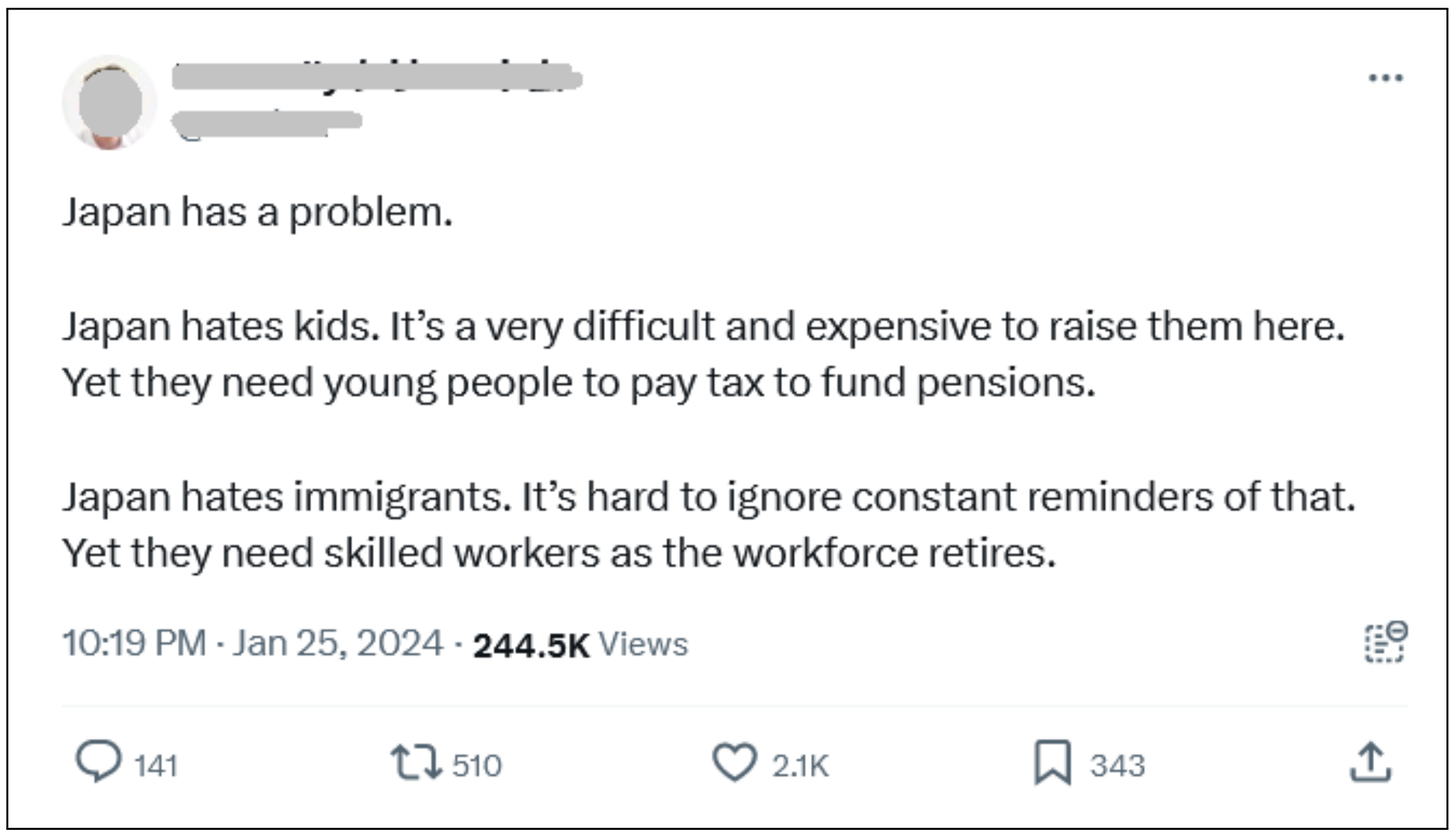

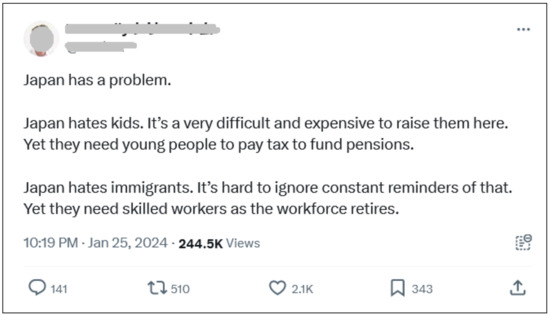

Japan Hates Kids. This claim constitutes a major issue in the discussions about immigrants and Japanese society. Figure 1 presents the screenshot of the tweet TW19 of user B1 which received many interactions. There are several other tweets from both groups as listed in Table A1 in Appendix A.

Figure 1.

Screenshot of tweet TW19 of the user B1 on the T1 topic.

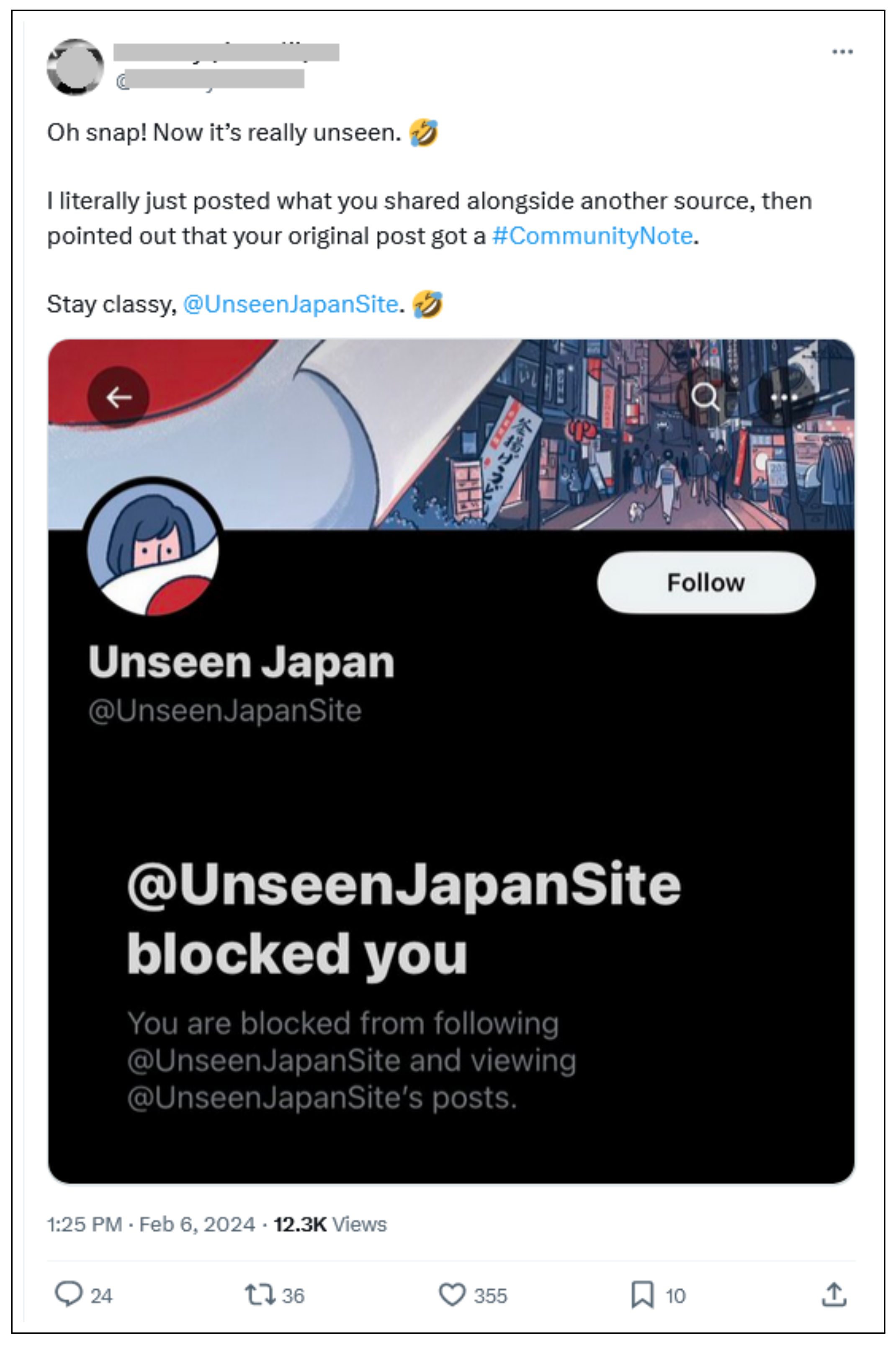

Japanese beauty contest. Ukrainian-born Karolina Shiino, who became a naturalized Japanese citizen, was the winner of Miss Japan contest in January 2024. This led to many online discussions, also raising questions such as “What does it mean to be Japanese?” Mainichi Japan (2024). Later, K. Shiino resigned. Figure 2 presents the tweet on this issue of the Unseen Japan media account, which has over 120 thousand followers. This tweet, which received many interactions, at first suggests that the resigning is due to right wing hate. Nevertheless, it was soon revealed that the resigning was due to some other issues of K. Shiino Takahara (2024). Unseen Japan deleted this tweet and blocked some accounts that criticized it.

Figure 2.

Screenshot of the tweet of Unseen Japan media account on the T2 topic. The text in Japanese reads Miss Japan Association: “The Gramd Prix will be vacant”. Carolina’s request to resign was “accepted”—a first in history for both the title and the vacancy.

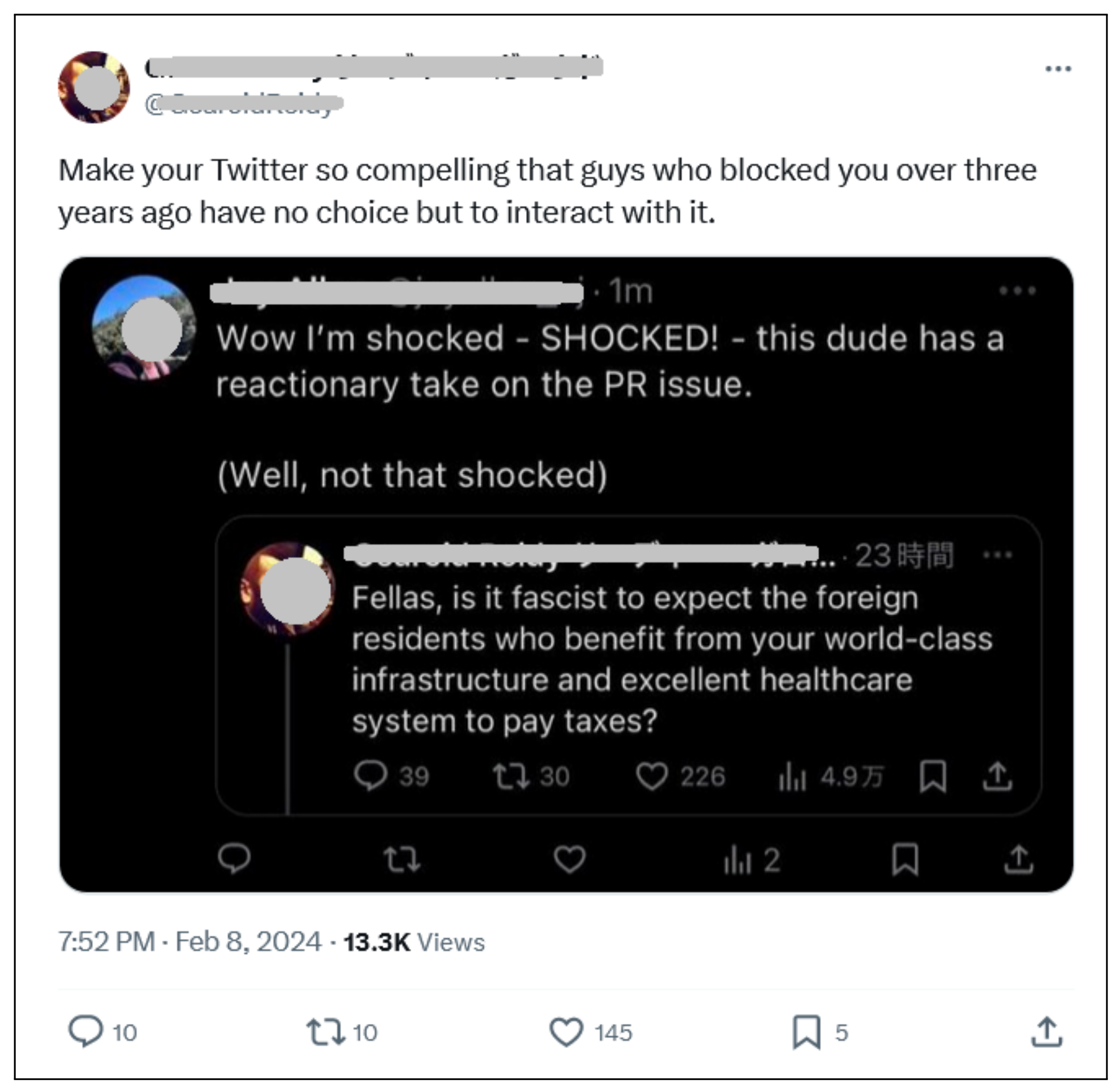

PR and taxes. Permanent residency visa status or PR is another prominent topic under discussion among not only foreigners but also Japanese people, and 12 of the tweets selected are on this topic. Following the Japanese Government’s consideration of revoking the permanent residence permits of foreigners who continuously fail to pay taxes and social security insurance premiums Nikkei Asia (2024), many discussions were held as well in the #GaijinTwitter community, even among users who blocked each other.

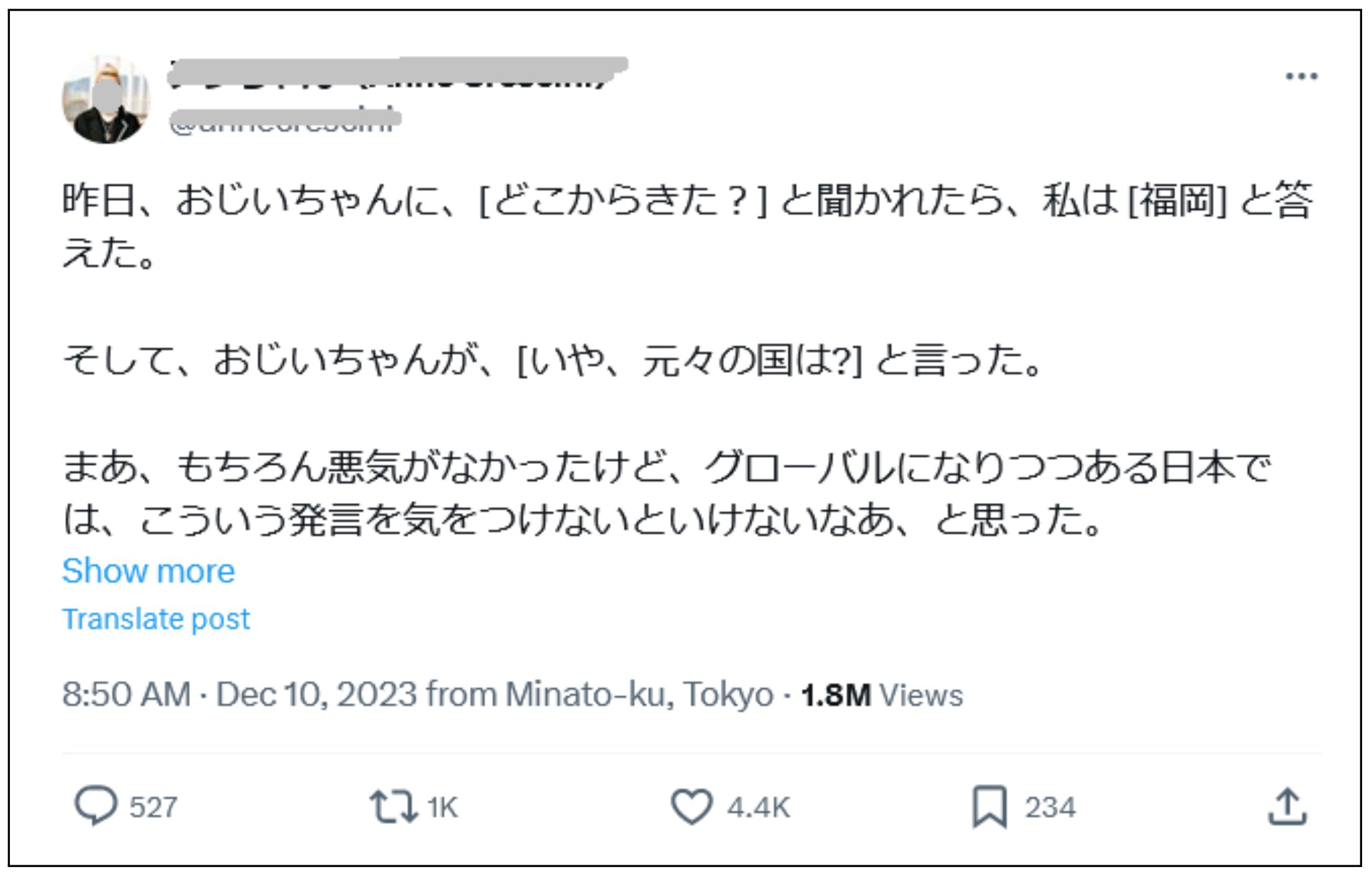

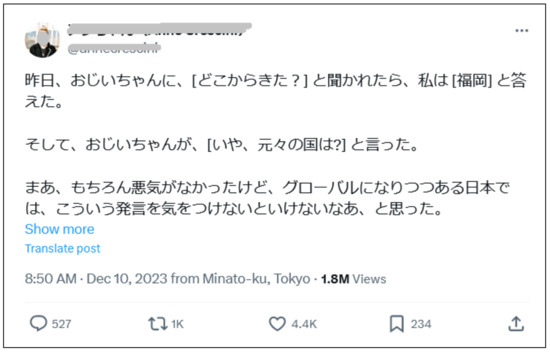

Citizenship (ex-foreigner). This topic encompasses significant examples. As shown in Figure 3 with the screenshot of the tweet TW34, viewed 1.8 million times, some foreigners who were naturalized Japanese citizens find it aggressive in daily life when Japanese people ask where they are from, for example.

Figure 3.

Screenshot of the tweet TW34 on the T4 topic, which can be translated into English as follows: Yesterday, when a grandpa asked me, “Where are you from?”, I answered, “Fukuoka.” And the grandpa said, “No, what country were you originally from?” Well, of course no harm was meant, but it made me think that in Japan that is becoming increasingly global, we need to be careful about making these kinds of statements.

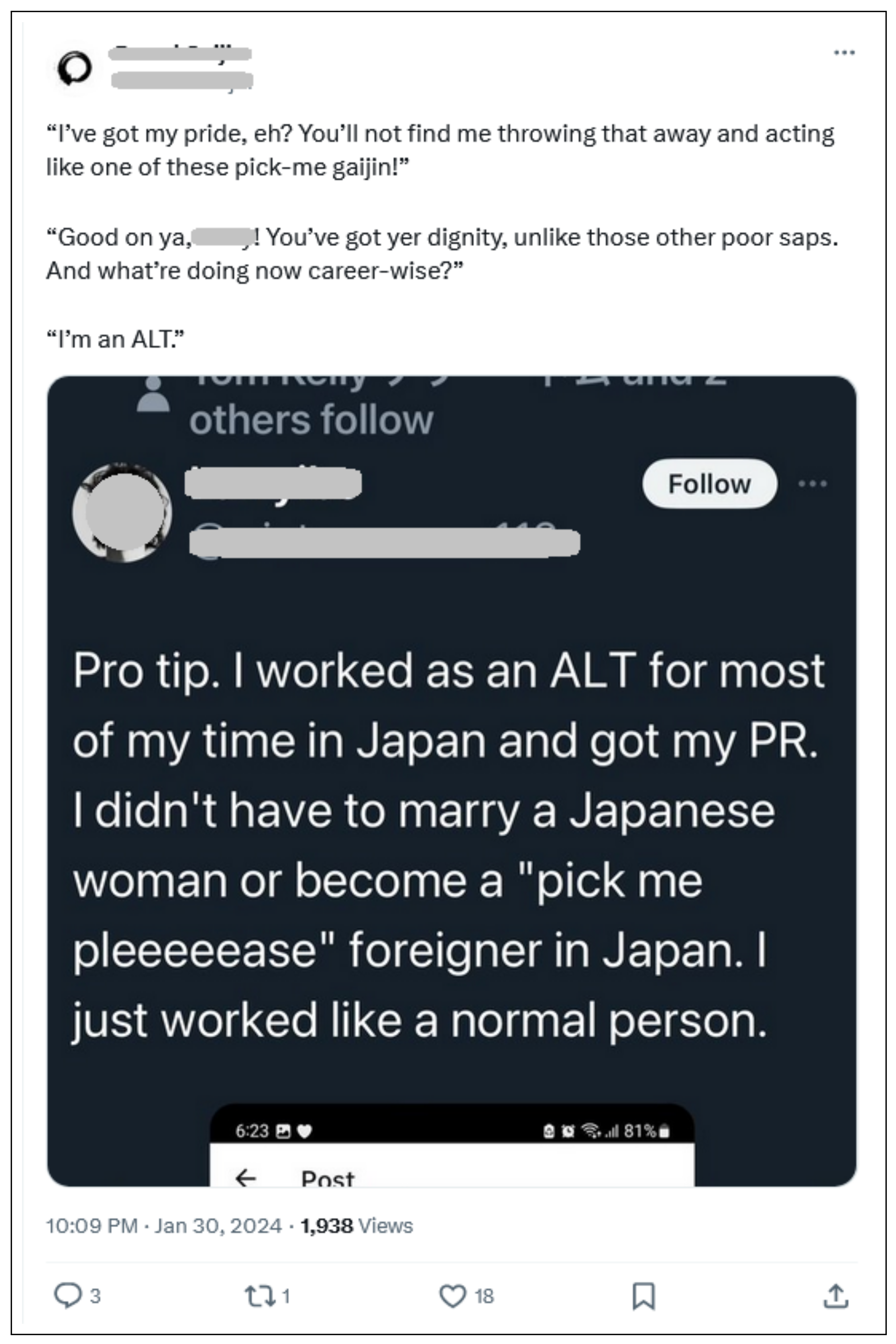

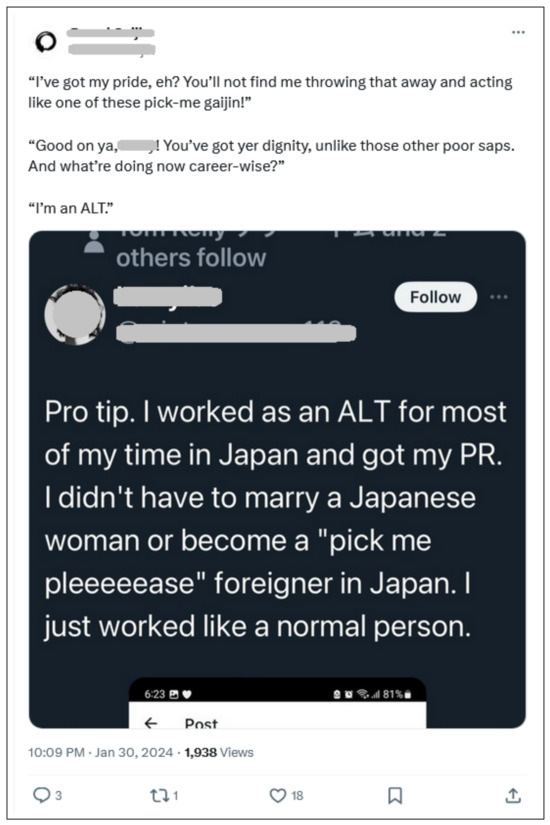

ALT. According to One World Language Services (2024), an Assistant Language Teacher (ALT) is a foreign national serving as an assistant teacher in a Japanese classroom, particularly for English. The term was created by the Japanese Ministry of Education (MEXT). ALTs share issues unique to them on SNS platforms. ALTs are usually criticized by other foreigners for consistently critiquing Japan, which is not uncommon in both offline and online communications, and in particular in the #GaijinTwitter community. Figure 4 presents a neat example on these critiques.

Figure 4.

Users A1, A2, A3, A4, and A6 in Group A were shown in a meme in a tweet of A4 to be tweeting against the users in Group B.

Blocking. As will be elaborated upon in Section 4.2, a significant number of users within the #GaijinTwitter community extensively employed the practice of blocking Twitter users with differing opinions. Hence, social blocking became one of the prominent topics in this context. Due to its contribution to the formation of echo chambers, we believe this topic receives particular attention. Note that the activities (tweets and interactions) in the Blocking topic are handled not in general but only within the #GaijinTwitter context and among the selected users.

Criticizing Japan. This is probably the topic central to the discussions in the #GaijinTwitter community. While some critiques might have a solid ground, some are criticized for being exaggerated. In our categorization, users in Group A are claiming that users in Group B are usually the ones who exaggerate, criticizing many things in Japan about foreign people.

4.1. Group Polarization

Identifying the users within each group is crucial for understanding if group polarization and echo chambers exist. We will accomplish this by carefully examining the content of tweets and the resulting interactions. Following an extensive period of observation encompassing the identities of those engaging in discourse within respective topics coming from different viewpoints, along with additional tweets from outside individuals about the growing factions, six users are identified as organic constituents of each group, i.e., A1 through A6 and B1 through B6. The follower and following counts of the selected users are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Statistics of the Twitter users in each group.

Figure 4 presents a tweet of user A4 posting a meme alleging that the users A1, A2, A3, A4 (themself), and A6, constituting the majority of Group A within our study, have coalesced into a collective actively posting content in opposition to users espousing divergent viewpoints, which are aligned with Group B in our investigation. As a matter of fact, Group A are opposing Group B claiming that they tend to criticize Japan harshly. The language used in the tweets (including the word in the meme in Figure 4) highlights the existence of group polarization.

Subsequently, the task entailed pinpointing tweets authored by users that markedly influenced the discourse on the chosen topics. A comprehensive examination encompassing tweet and interaction metrics, alongside tweet content analysis, facilitated the curation of the top three tweets per user. The detailed compilation of these tweets, omitting their contents, which are available upon request, along with the hyperlinks to the original tweets, is delineated in Table A1 in Appendix A.

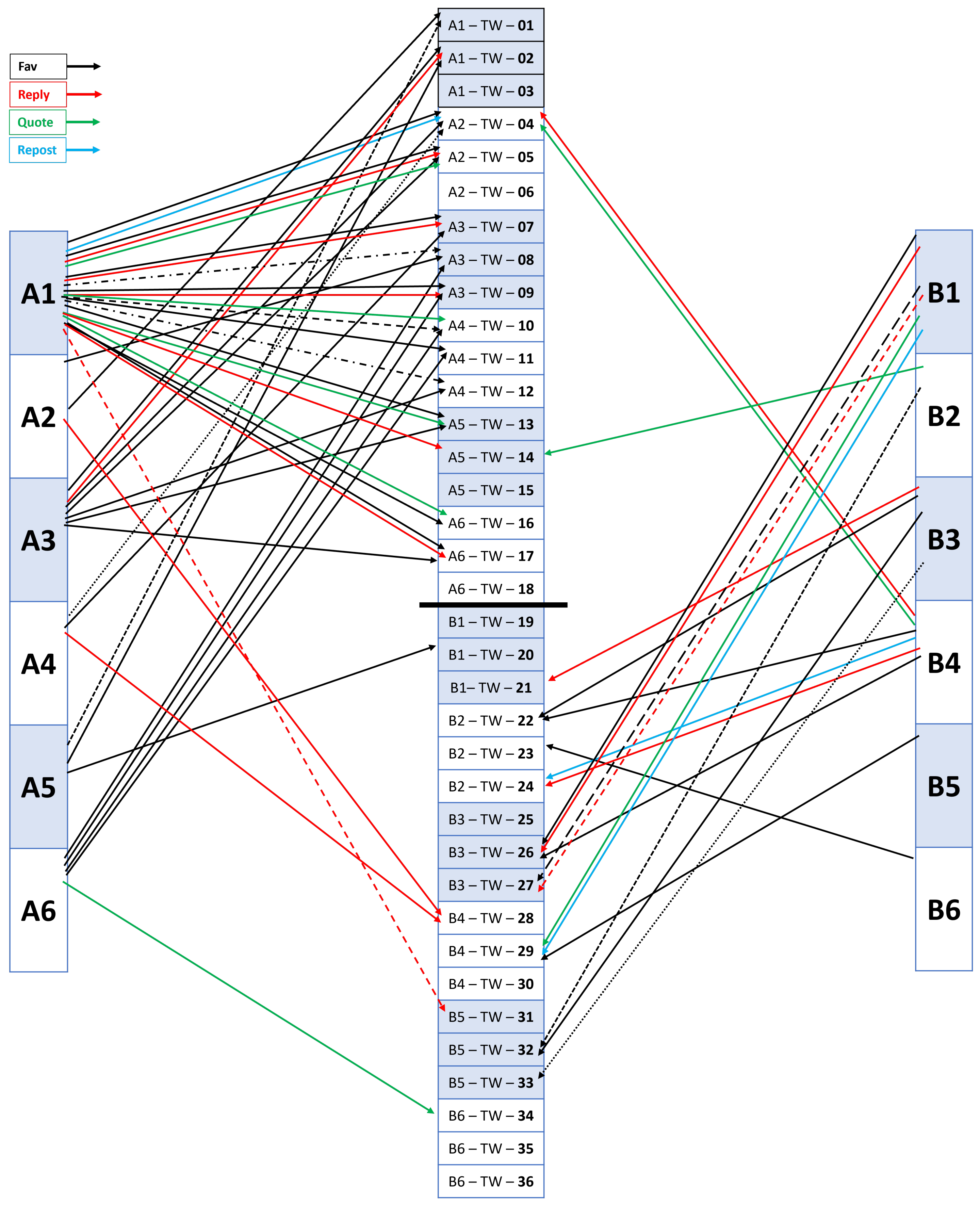

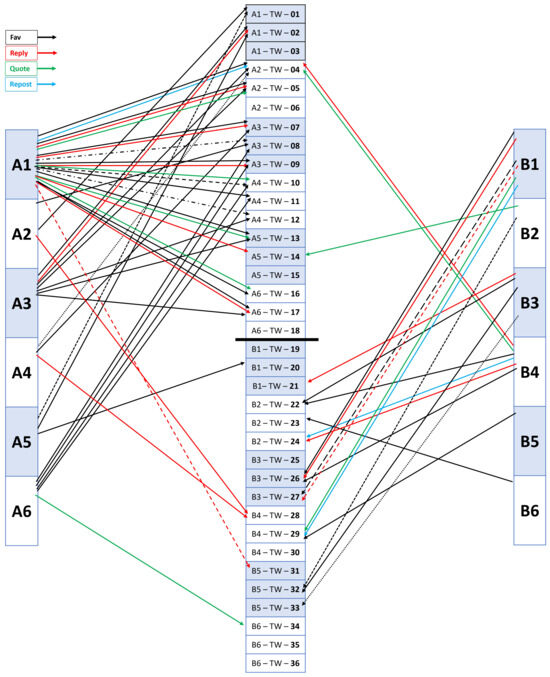

The pivotal discovery of this study is elucidated through the interaction map. Interaction, as conceptualized in our research, encompasses responses initiated by users from either Group A or Group B in response to tweets authored by users from either group. Having identified the users, topics, and the main 36 tweets through checking a vast number of tweets, the overall interactions towards these tweets were studied. In particular, 1783 Replies, 1768 Quotes, 4454 Reposts, and 32,271 Favs, summing up to 40,276 interactions, were analyzed. Among these interactions, 64 are identified to be between the users of the two groups, which are {Reply: 14, Quote: 8, Repost: 3, Fav: 39}, and are graphically depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Interaction map from Group A and Group B to the set of selected tweets from Group A or Group B. Some lines are displayed as solid, dashed, or dotted-dashed only for the sake of clarity and do not have an additional meaning.

The tweets occupy the central position of the figure, with the 18 selected tweets from Group A situated at the top and the 18 chosen tweets from Group B positioned at the bottom. Users affiliated with Group A are situated on the left side, while those associated with Group B are located on the right side. Each interaction is represented by an arrow extending from a user to a tweet, color-coded according to the type of interaction. It is noteworthy that certain lines may be displayed as solid, dashed, or dotted-dashed only for the sake of clarity. Although Figure 5 is beneficial in presenting the interaction map in detail, it is also difficult to follow each interaction. Hence, a clearer figure is needed in which only the percentages and directions of the interactions are presented.

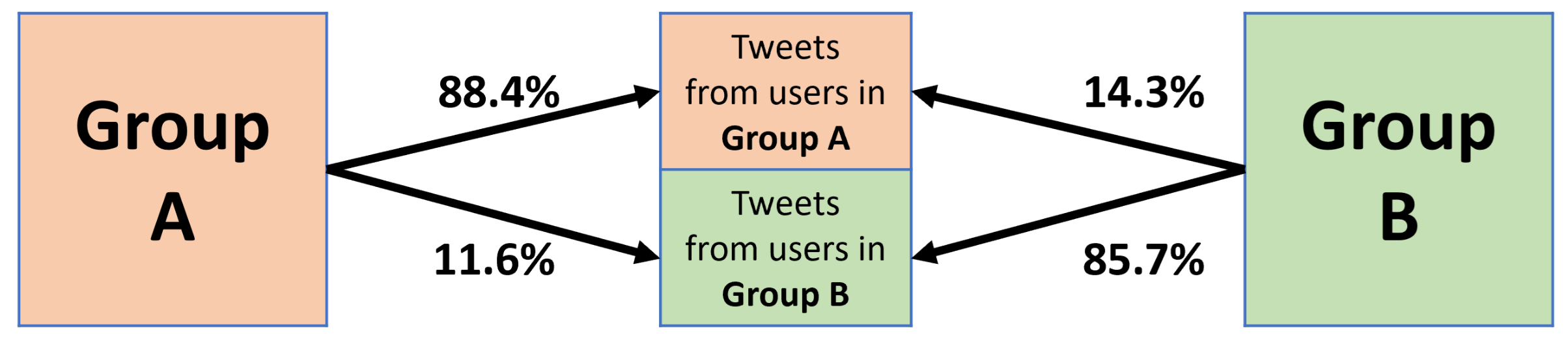

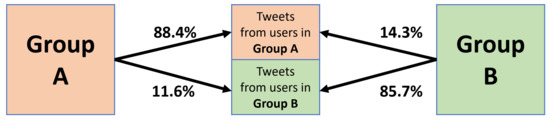

As summarized in Figure 6, out of 43 interactions originating from Group A, 38 are directed towards tweets within Group A, while 5 interactions are directed towards tweets within Group B. Conversely, out of 21 interactions originating from Group B, 18 are directed towards tweets within Group B, while 3 interactions are directed towards tweets within Group A.

Figure 6.

Percentages of interactions from Group A and Group B towards tweets from Group A or Group B.

To develop meaningful insights into group polarization, we focus on the detailed interaction map shown in Figure 5. With one exception (from A5 to B1’s tweet TW-20), all the Favs, represented by black arrows, occur within each group. Since it is reasonable to assume that a Fav indicates agreement or shared opinion, tracing these interactions serves as a reliable indicator of group formation.

A similar argument applies to the Reposts, which, notably, exhibit no exceptions within the interaction map. In contrast, Replies and Quotes can originate from users with either similar or opposing opinions. Consequently, inter-group interactions, represented by red and green arrows, are expected to appear on the map. These cross-interactions provide additional insights into group interactions and may suggest group polarization.

Evidence of polarization is further substantiated by linguistic patterns, the use of memes within tweets, and a qualitative examination of the tweet content. In response to RQ1, these findings indicate that immigrant-related issues in Japan contribute significantly to the polarization of immigrant groups within the #GaijinTwitter community.

As a response to the second research question (RQ2), the topics listed in Table 1 spanning these interactions are found to be prominent contemporary topics under scrutiny within the discussions that lead to group polarization.

Moreover, the predominance of interactions occurring within each respective group, compared with the lesser frequency of interactions across groups, indicates the existence of group polarization. Since group polarization is a necessary but insufficient condition for the formation of echo chambers, this finding also indicates a potential for echo chambers. Given that the formation and reinforcement of echo chambers among polarized groups often stem from intentional behaviors such as selective exposure, our subsequent analysis aims to uncover any discernible evidence of deliberate actions in this regard.

4.2. Social Blocking and Echo Chambers

Detecting or quantifying the deliberate actions of social media users in terms of whom they follow and their exposure to diverse opinions poses considerable challenges, often proving unreliable and infeasible in many cases. However, observing deliberative behaviors in terms of limiting exposure, such as through blocking, may offer a more discernible and straightforward avenue for analysis.

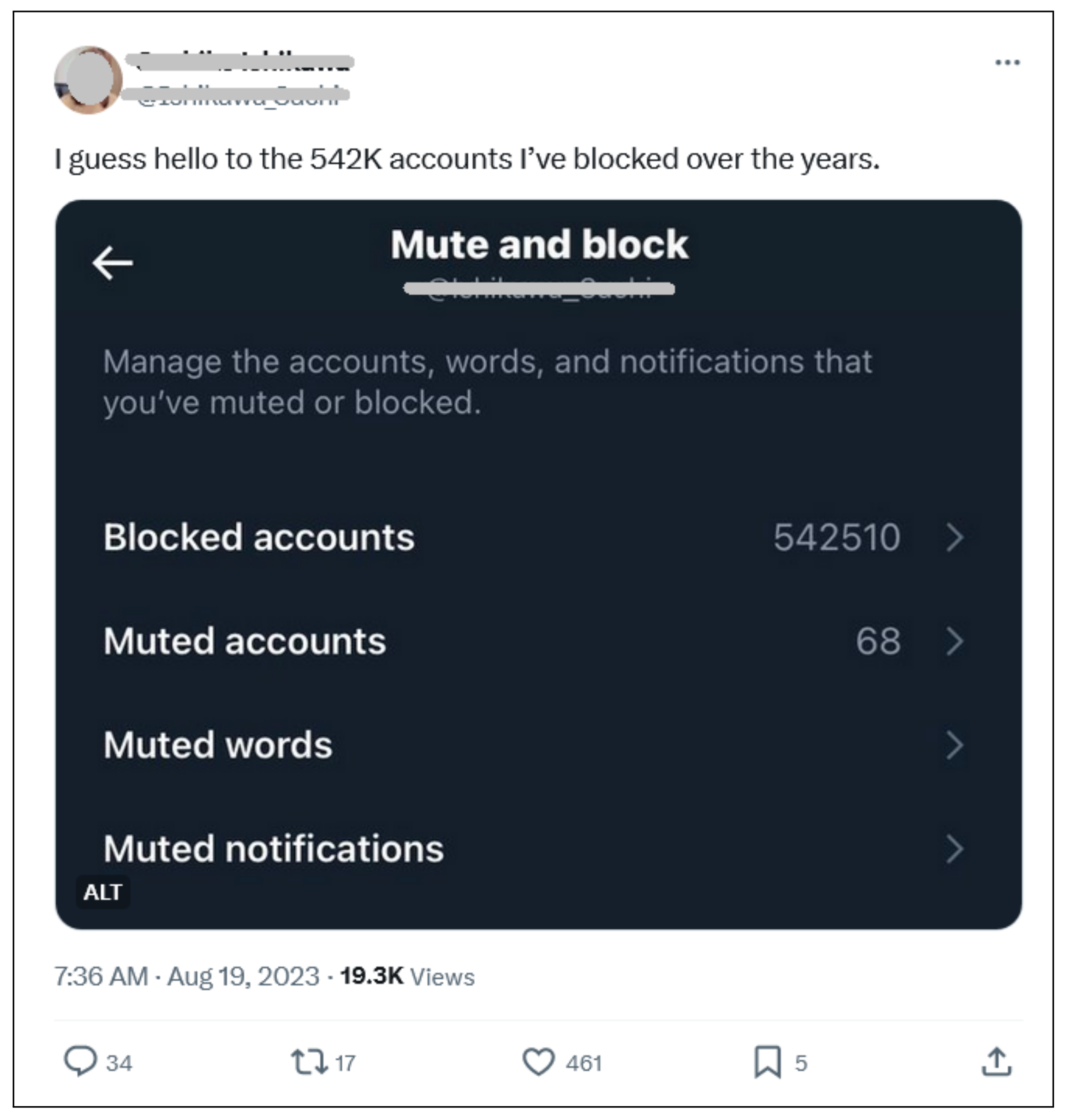

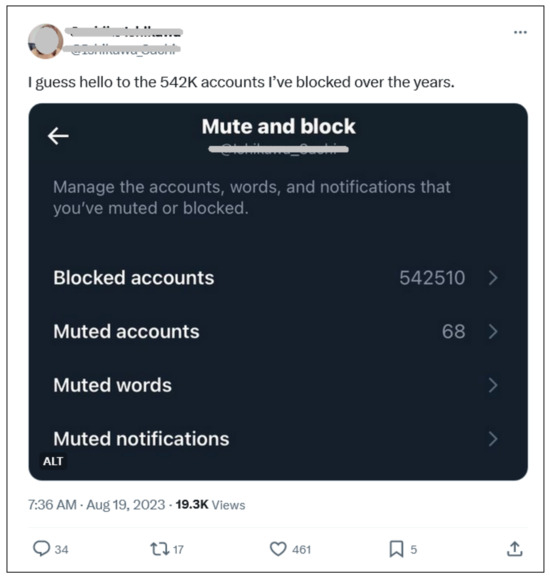

A particularly noteworthy example is the case of user B5, highlighted in Figure 7. This user disclosed their Twitter account statistics, revealing an extensive history of blocking and muting accounts, totaling over half a million. While not all the blocked users may have been involved in the #GaijinTwitter discourse, the significant activity of this user within this specific discussion context suggests that social blocking carries implications for contributing to polarization and the formation of echo chambers.

Figure 7.

The screenshot of a tweet of user B5 showing the mass blocking of other Twitter users.

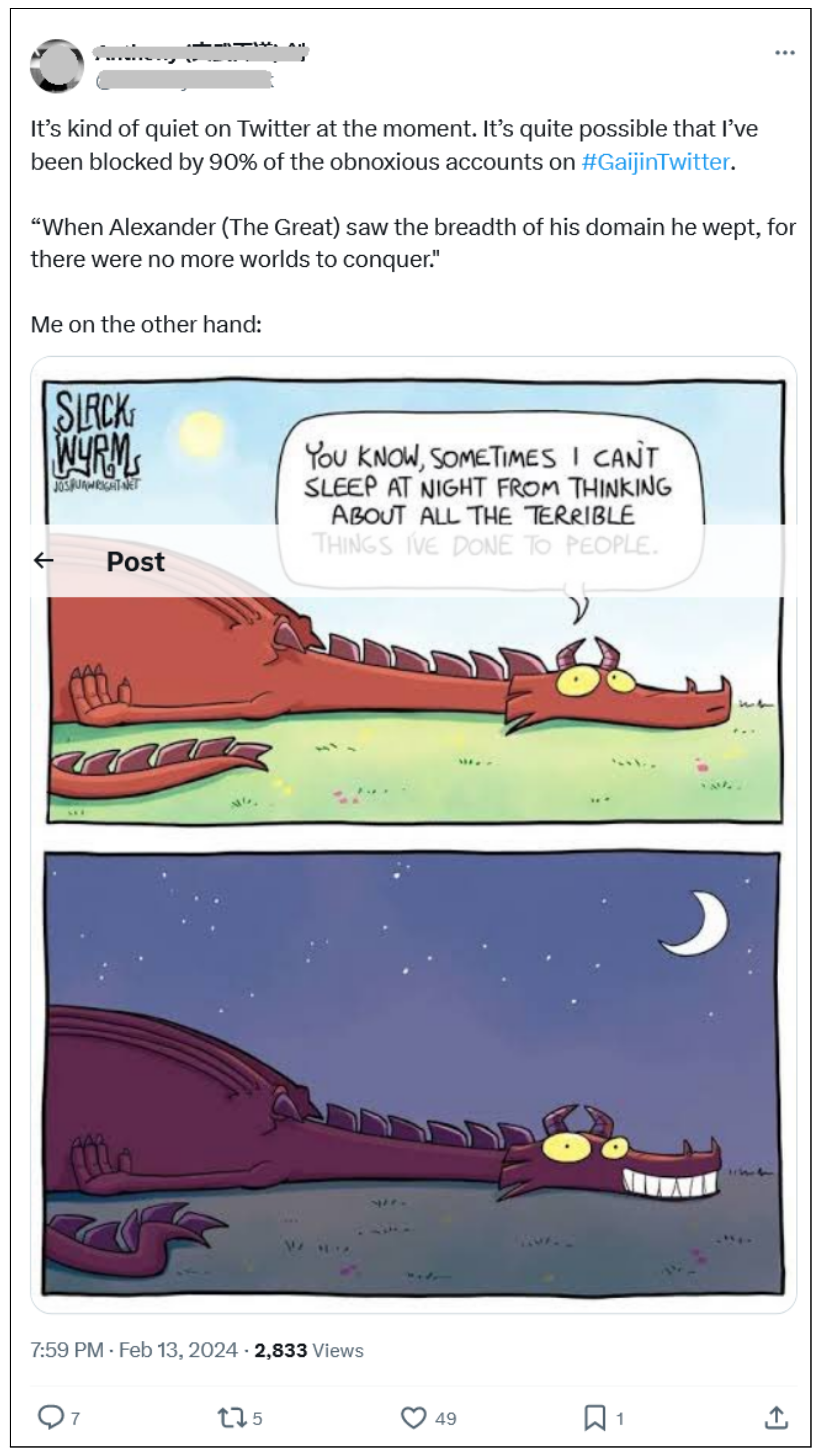

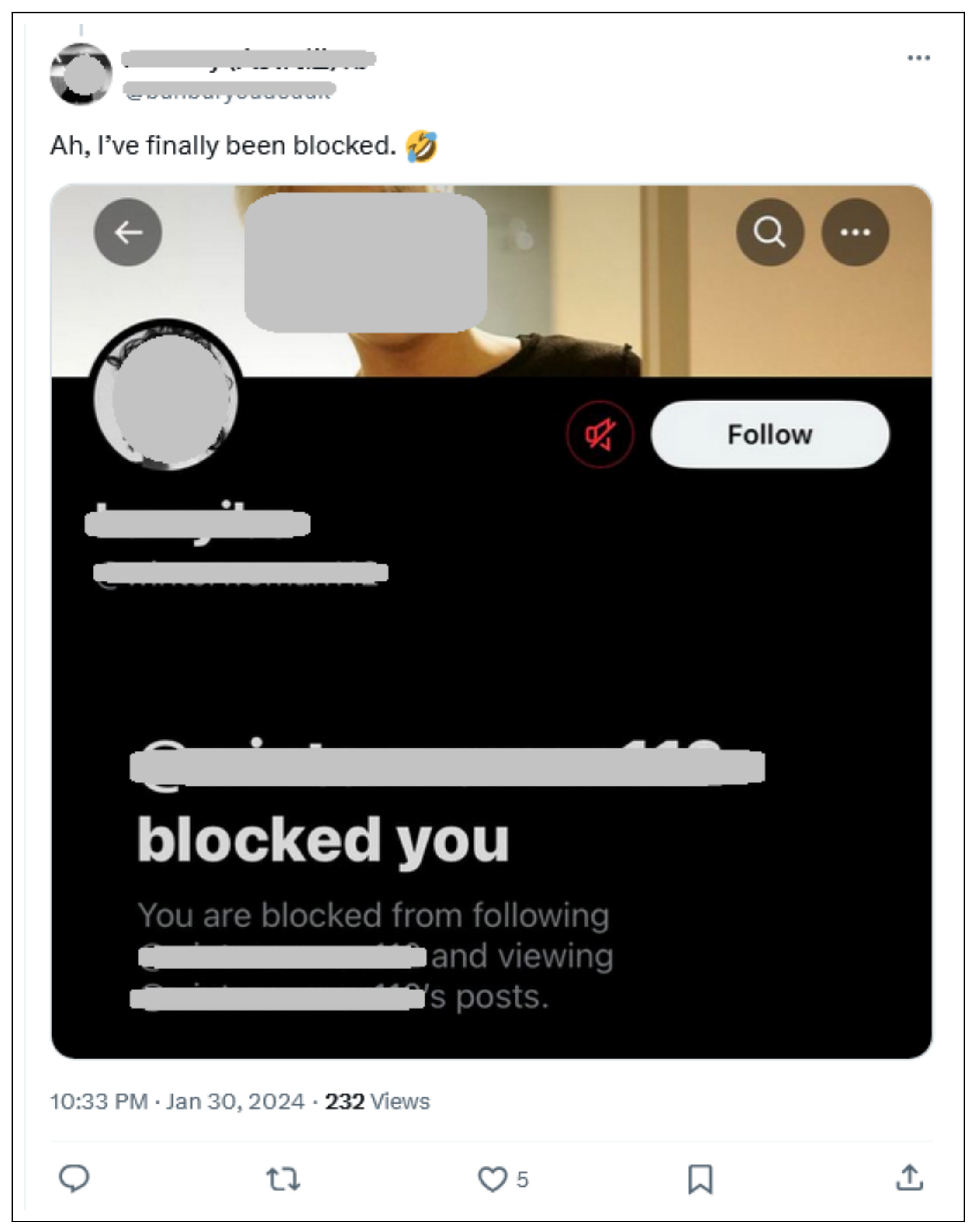

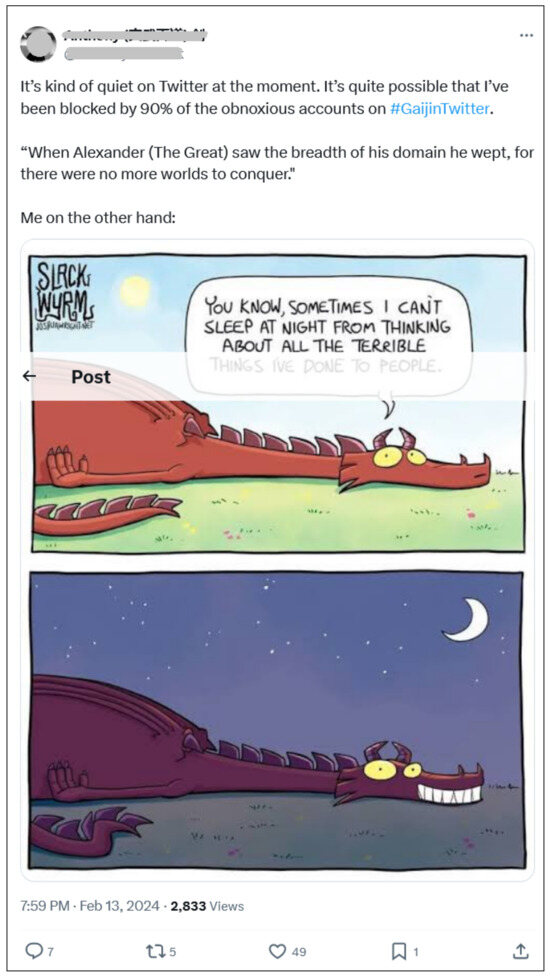

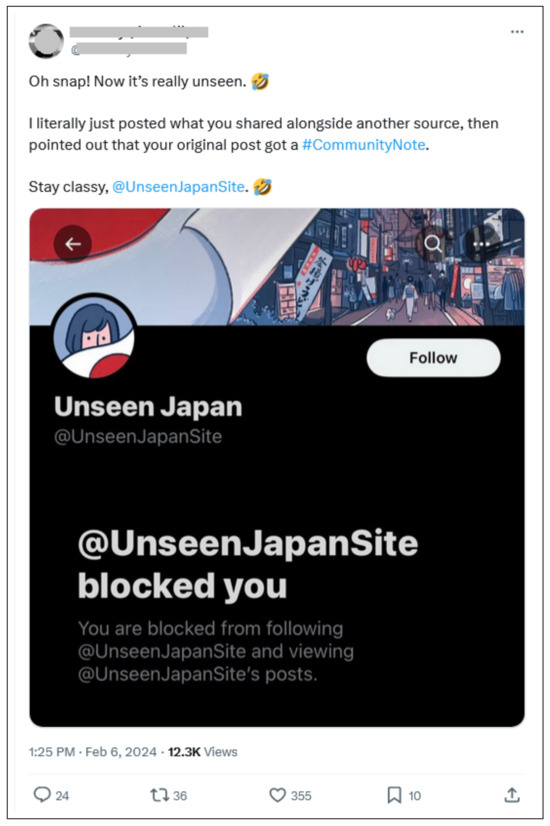

Moreover, we find solid evidence that both groups employ the blocking of users in the other group. Our first indication is a tweet of user A1 (see Figure 8) claiming that they have been blocked by 90% of accounts in the #GaijinTwitter community. Our second indication is again based on user A1’s tweet (see Figure 9) showing that the Unseen Japan media outlet blocked them.

Figure 8.

Screenshot of a tweet of user A1 claiming to be blocked by 90% of the users in the #GaijinTwitter community.

Figure 9.

Screenshot of a tweet of user A1 showing that they are blocked by the Unseen Japan media account.

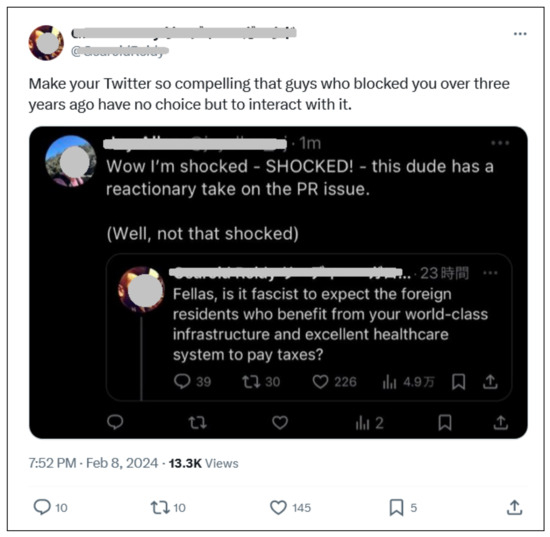

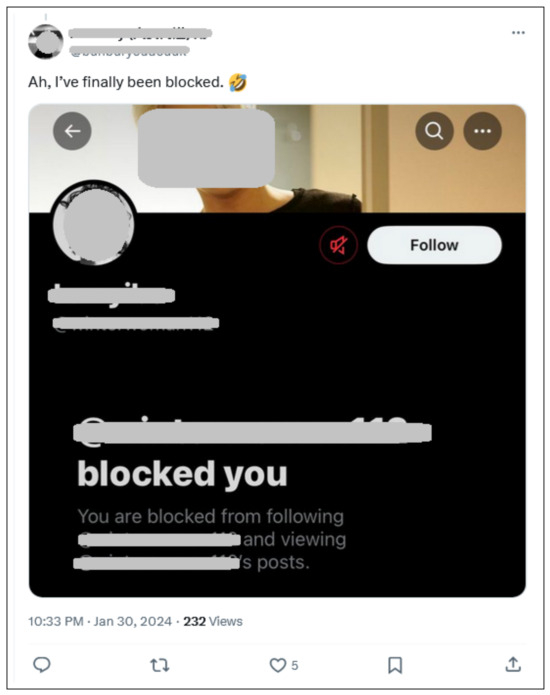

Next is a tweet of user A2 in Figure 10, showing that user B2 blocked them. This is followed in Figure 11 showing that user A1 is blocked by user B3.

Figure 10.

Screenshot of the tweet of user A2 on being blocked by user B2. In the picture, “23 (Chinese character)” means 23 hours in English.

Figure 11.

Screenshot of the tweet of user A1 showing that they are blocked by user B3.

The impact of blocking on the formation and perpetuation of echo chambers is readily apparent. However, our research has uncovered an additional intriguing behavior. Rather than engaging with a tweet in conventional manners such as replying or quoting, some users choose to capture a screenshot of the target tweet (of a user from the other group) and create a new tweet containing that screenshot along with their commentary. This method, though less straightforward than the standard interactions requiring only a single click, circumvents direct notification to the author of the target tweet and their followers. Consequently, neither the author nor their followers are directly exposed to this reaction nor provided an opportunity to respond. We posit that this intentional action serves to reinforce and solidify echo chambers. An illustrative example from the #GaijinTwitter community is presented in Figure 12, wherein user A3 shares a tweet featuring a screenshot of a tweet authored by user B3.

Figure 12.

An example tweet showing that instead of reacting to the tweet of user B3 in a standard way, user A3 chose the capture the screenshot of that tweet and posted it in a new tweet.

4.3. Additional Hypotheses for Future Research

In this subsection, we present five new hypotheses in four categories for further research. Each hypothesis is grounded in the findings of our study, particularly the interaction patterns, social blocking behaviors, and screenshot-sharing practices. Additionally, we elaborate on the underlying assumptions and explain how they are inferred from the research findings.

4.3.1. Role of Interaction Dynamics in Echo Chambers

Hypothesis 1.

Higher frequency of blocking between users within online communities reinforces echo chambers by reducing exposure to opposing viewpoints.

Assumption 1: Blocking is a deliberate action primarily used to avoid exposure to conflicting opinions.

Justification: The study identifies extensive blocking practices (Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11), with users like B5 blocking hundreds of thousands of accounts. The rationale behind blocking stems from the desire to avoid confrontation and opposing viewpoints, as evidenced by the minimal inter-group interactions observed in Figure 5. This supports the assumption that blocking is intentional and leads to self-reinforcing echo chambers by reducing cross-group exposure.

Hypothesis 2.

Screenshot-sharing practices, particularly when used to mock or criticize opposing groups, amplify polarization by fostering in-group solidarity and reinforcing out-group stereotypes.

Assumption 2: Screenshot-sharing is employed as an alternative to direct interaction to limit the opposing group’s ability to respond.

Justification: As shown in Figure 12, users frequently capture screenshots of tweets instead of replying or quoting directly. This behavior bypasses standard interactions, preventing notifications to the original tweet’s author and their followers. The intention appears to be avoiding direct confrontation while fostering in-group consensus, which aligns with the assumption that screenshot-sharing contributes to polarization.

4.3.2. Cultural Identity and Online Polarization

Hypothesis 3.

In immigrant communities like #GaijinTwitter, discussions around shared cultural experiences intensify polarization by highlighting identity-based divisions.

Assumption 3: Discussions of cultural identity trigger emotional responses and accentuate existing divisions within immigrant communities.

Justification: Topics such as “Citizenship (ex-foreigner)” (Figure 3) and “Japan Hates Kids” (Figure 1) reveal strong emotional undertones in user interactions. Users in Group A and Group B often interpret these issues through their cultural lenses, leading to polarized discourse. The assumption that cultural identity discussions intensify divisions is supported by the observed patterns of intra-group agreement and inter-group conflict.

4.3.3. Cross-Platform Comparison

Hypothesis 4.

Echo chamber and polarization effects are more pronounced on platforms like Twitter, where brevity and viral content dominate, compared to platforms with longer-form discussions such as Reddit.

Assumption 4: Platform design influences the nature and depth of user interactions.

Justification: The findings highlight Twitter’s role in encouraging brief, viral interactions, as seen in the prevalence of memes, screenshots, and short critiques (Figure 4 and Figure 12). Unlike platforms like Reddit, where longer discussions allow for more nuanced debates, Twitter’s format prioritizes rapid, emotionally charged content. This supports the assumption that platform design shapes interaction patterns and contributes to polarization.

4.3.4. Temporal Evolution of Polarization

Hypothesis 5.

Over time, interaction patterns within polarized groups evolve to exhibit more extreme positions, reducing the likelihood of inter-group dialogue.

Assumption 5: Prolonged intra-group interactions reinforce shared viewpoints and reduce openness to opposing perspectives.

Justification: Figure 6 shows a stark imbalance between intra-group and inter-group interactions. This pattern suggests that repeated exposure to similar viewpoints within groups (Group A or Group B) reinforces pre-existing beliefs, creating a feedback loop that diminishes the likelihood of future cross-group engagement. Over time, this behavior aligns with the assumption that polarization intensifies as positions become more entrenched.

By connecting these hypotheses to the study’s findings and articulating the underlying assumptions, we provide a robust framework for future research. These assumptions reflect observable user behaviors and patterns within the #GaijinTwitter community, offering valuable insights into the mechanisms driving group polarization and echo chambers.

5. Discussion

Changes to Twitter’s API access have significantly constrained research possibilities and there is a need to innovate with small-scale manual data collection, e.g., of social blocking, and that is the methodological contribution of this paper.

This manual data collection process, reliant on extensive human effort, confers an advantage over automated methods. While automated methods are effective at gathering tweet data and monitoring responses to individual tweets, they struggle when users choose to take a screenshot of a tweet and then post it as a new tweet. In contrast, human oversight is skilled at identifying such instances, whereas automated processes are likely to overlook them unless equipped with advanced AI techniques such as image processing, optical character recognition, and sentiment analysis.

The behavior observed in this study, where users choose to post a new tweet containing a screenshot of the target tweet along with their commentary rather than reacting through conventional means, effectively conceals this reaction from both the author of the target tweet and their followers. Particularly noteworthy is the fact that the author of the target tweet often belongs to a group with contrasting opinions. We identify this behavior as a contributing factor to the formation and reinforcement of echo chambers. This observation aligns with broader implications regarding interaction behaviors on social media platforms, as discussed below.

Our findings reveal that specific interaction behaviors, such as blocking and screenshot-sharing, play a pivotal role in shaping polarization and echo chambers. These behaviors not only limit exposure to diverse viewpoints but also encourage the dissemination of content that reinforces existing biases. Social media platforms might consider implementing features that promote constructive dialogue, such as moderated discussion spaces or prompts encouraging users to engage with opposing viewpoints.

Although Twitter’s content ranking and follow suggestion algorithms could potentially contribute to polarization, their opaque nature precludes their inclusion in our current analysis. Nevertheless, further exploration of these algorithms, alongside user behavior, could illuminate the mechanisms driving polarization and echo chamber formation on digital platforms.

Inspired by Liu-Farrer (2020), we believe it would be fruitful in future research to conduct consented interviews with selected users to reveal attributes such as the emotional geography of online interactions, shedding light on the root causes of group polarization and echo chambers observed in this study. Additionally, we find the paradox pointed out by Liu-Farrer (2020) intriguing—that Japan simultaneously provides social and cultural attractions for immigrants while deterring them with opposing or similar forces. One might argue that this paradox underpins the group polarization considered here, warranting further examination in future research.

Theoretical contributions of this study extend beyond descriptive analysis, offering insights into how group polarization and echo chambers manifest within expatriate communities. Unlike general online groups, communities such as #GaijinTwitter are shaped by shared cultural and geographic experiences, adding unique layers to their polarization dynamics. This duality of unification and division within such communities highlights the interplay of cultural identity and online discourse.

Evaluating which connection (the ‘following’ relation on Twitter) is more significant in determining the dynamics of group polarization and, more generally, the spread of information was not in the scope of the present study. However, mathematical models for quantifying the significance of connections in a social network, such as those proposed in Yurtcicek Ozaydin and Ozaydin (2021) and Lubashevskiy et al. (2023), could contribute to our understanding of these connections and their role in fostering group polarization. These models, combined with longitudinal studies, could reveal how interaction patterns evolve and whether they sustain or mitigate echo chambers over time.

Finally, as a potential direction for future research, it may be insightful to compare the dynamics of polarization and echo chambers across different platforms, such as Twitter and Reddit, to identify platform-specific factors. Expanding the analysis with sentiment analysis or natural language processing techniques could provide a more granular understanding of the sentiments and themes driving polarization within the #GaijinTwitter community and beyond.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study sheds light on group polarization and echo chambers within the online discussions of immigrants in Japan, particularly within the #GaijinTwitter community. Through our analysis of divergent group interactions and the prevalence of social blocking and screenshot-sharing, we have demonstrated the existence of group polarization and echo chambers. These findings underscore the importance of understanding and addressing these phenomena within online sociological contexts. Further research should delve deeper into the mechanisms underlying these dynamics and explore potential interventions to mitigate their effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y.O.; methodology, S.Y.O., V.L. and F.O.; software, V.L. and F.O.; validation, S.Y.O., V.L. and F.O.; formal analysis, S.Y.O., V.L. and F.O.; investigation, S.Y.O., V.L. and F.O.; resources, S.Y.O., V.L. and F.O.; data curation, V.L. and F.O.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Y.O., V.L. and F.O.; writing—review and editing, S.Y.O., V.L. and F.O.; visualization, V.L. and F.O.; supervision, S.Y.O.; project administration, S.Y.O.; funding acquisition, F.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

F.O. acknowledges the financial support of Tokyo International University Personal Research Fund.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this work will be provided to scholars upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

The entity relationshop diagram is presented in Figure A1. It is noteworthy that table names commence with “public”, denoting the dedicated application on Django. Additionally, certain table or field names are selected to avoid conflicts with Python or Django keywords. Supplementary fields and redundant relationships are incorporated to facilitate efficient querying.

Figure A1.

Entity relationship diagram of the database.

Figure A1.

Entity relationship diagram of the database.

Table A1.

Basic statistics of the Twitter users in two groups as the authors of the tweets under consideration.

Table A1.

Basic statistics of the Twitter users in two groups as the authors of the tweets under consideration.

| Tweet | User | Topic | Views | Replies | Quotes | Reposts | Favs | Bookmarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TW01 | A1 | T1 | 36,100 | 37 | 7 | 55 | 397 | 34 |

| TW02 | A1 | T2 | 163,000 | 135 | 90 | 671 | 3000 | 391 |

| TW03 | A1 | T4 | 16,500 | 18 | 9 | 24 | 183 | 31 |

| TW04 | A2 | T3 | 56,500 | 38 | 12 | 20 | 242 | 20 |

| TW05 | A2 | T6 | 12,800 | 9 | 2 | 10 | 146 | 5 |

| TW06 | A2 | T3 | 45,900 | 30 | 9 | 27 | 322 | 23 |

| TW07 | A3 | T5 | 1794 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 18 | 0 |

| TW08 | A3 | T1 | 3000 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 64 | 2 |

| TW09 | A3 | T1 | 14,000 | 23 | 1 | 6 | 125 | 14 |

| TW10 | A4 | T4 | 17,100 | 11 | 5 | 13 | 162 | 11 |

| TW11 | A4 | T2 | 6200 | 11 | 6 | 12 | 135 | 5 |

| TW12 | A4 | T3 | 4623 | 12 | 2 | 10 | 77 | 0 |

| TW13 | A5 | T3 | 95,300 | 64 | 30 | 55 | 274 | 119 |

| TW14 | A5 | T5 | 55,800 | 221 | 53 | 43 | 722 | 29 |

| TW15 | A5 | T5 | 3800 | 13 | 0 | 12 | 95 | 8 |

| TW16 | A6 | T3 | 8860 | 13 | 3 | 23 | 151 | 17 |

| TW17 | A6 | T1 | 14,900 | 21 | 3 | 53 | 340 | 27 |

| TW18 | A6 | T6 | 6900 | 8 | 1 | 16 | 114 | 8 |

| TW19 | B1 | T1 | 242,000 | 144 | 120 | 398 | 2100 | 352 |

| TW20 | B1 | T1 | 29,500 | 17 | 8 | 55 | 563 | 21 |

| TW21 | B1 | T3 | 63,100 | 47 | 13 | 18 | 227 | 44 |

| TW22 | B2 | T3 | 10,200 | 13 | 0 | 1 | 98 | 8 |

| TW23 | B2 | T7 | 81,800 | 34 | 28 | 518 | 2400 | 136 |

| TW24 | B2 | T3 | 13,400 | 10 | 1 | 7 | 91 | 7 |

| TW25 | B3 | T5 | 21,100 | 19 | 2 | 11 | 257 | 62 |

| TW26 | B3 | T3 | 2600 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 68 | 1 |

| TW27 | B3 | T5 | 1730 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 1 |

| TW28 | B4 | T3 | 20,000 | 16 | 1 | 14 | 119 | 17 |

| TW29 | B4 | T3 | 132,800 | 84 | 38 | 78 | 358 | 67 |

| TW30 | B4 | T3 | 21,500 | 18 | 4 | 22 | 181 | 14 |

| TW31 | B5 | T6 | 19,200 | 34 | 3 | 14 | 463 | 4 |

| TW32 | B5 | T7 | 40,000 | 33 | 7 | 182 | 1200 | 56 |

| TW33 | B5 | T7 | 22,700 | 32 | 2 | 24 | 430 | 17 |

| TW34 | B6 | T4 | 1,800,000 | 533 | 645 | 416 | 4400 | 239 |

| TW35 | B6 | T4 | 48,600 | 62 | 21 | 39 | 416 | 17 |

| TW36 | B6 | T2 | 2,800,000 | 0 | 641 | 1600 | 12,300 | 371 |

| Total | 5,933,307 | 1783 | 1768 | 4454 | 32,271 | 2178 |

References

- Aldayel, Abeer, and Walid Magdy. 2022. Characterizing the role of bots’ in polarized stance on social media. Social Network Analysis and Mining 12: 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arudou, Debito. 2017. Media marginalization and vilification of minorities in Japan. In Press Freedom in Contemporary Japan. Kyoto: International Research Centre for Japanese Studies, National Institute for the Humanities, pp. 213–28. [Google Scholar]

- Asahina, Yuki, and Naoto Higuchi. 2020. Guest editorial the third round of migrant incorporation in East Asia: An introduction to the special issue on friends and foes of multicultural East Asia. Journal of Contemporary Eastern Asia 19: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberá, Pablo. 2015. Birds of the same feather tweet together: Bayesian ideal point estimation using twitter data. Political Analysis 23: 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitra, Uthsav, and Christopher Musco. 2020. Analyzing the impact of filter bubbles on social network polarization. Paper presented at the 13th International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Houston, TX, USA, February 3–7; pp. 115–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colleoni, Elanor, Alessandro Rozza, and Adam Arvidsson. 2014. Echo chamber or public sphere? predicting political orientation and measuring political homophily in twitter using big data. Journal of Communication 64: 317–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conover, Michael, Matthew Ratkiewicz, Jacoband Francisco, Bruno Goncalves, Filippo Menczer, and Alessandro Flammini. 2011. Political polarization on twitter. Paper presented at the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Barcelona, Spain, July 17–21, vol. 5, pp. 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Davison, Jeremy, and Ito Peng. 2021. Views on immigration in Japan: Identities, interests, and pragmatic divergence. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47: 2578–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, Paul, John Evans, and Bethany Bryson. 1996. Have american’s social attitudes become more polarized? American Journal of Sociology 102: 690–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, Emilio, Onur Varol, Clayton Davis, Filippo Menczer, and Alessandro Flammini. 2016. The rise of social bots. Communications of the ACM 59: 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaxman, Seth, Sharad Goel, and Justin M. Rao. 2016. Filter bubbles, echo chambers, and online news consumption. Public Opinion Quarterly 80: 298–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomini, Gabriele, and Roberto Paura. 2023. The ideal of pluralism and the problem of online polarisation. four scenarios and five proposals for the future. Journal of Futures Studies 27: 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, Naoto. 2024. Immigration and nationalism in Japan. In Migration and Nationalism. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 136–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kage, Rieko, Frances M. Rosenbluth, and Seiki Tanaka. 2022. The fiscal politics of immigration: Expert information and concerns over fiscal drain. Political Communication 39: 826–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Gento, and Fan Lu. 2023. The relationship between university education and pro-immigrant attitudes varies by generation: Insights from Japan. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 35: edad027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Tetsuro, Zhifan Zhang, and Ling Liu. 2024. Is partisan selective exposure an American peculiarity? A comparative study of news browsing behaviors in the United States, Japan, and Hong Kong. Communication Research, 00936502241289109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotomi, Li. 2020. Before You Call Me “gaijin”. July 13. Available online: https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-topics/g00859/ (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Kyodo News. 2024. Record 3.4 Million Foreign Residents in Japan as Work Visas Rise. March 22. Available online: https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2024/03/d72c3226dfb0-record-34-million-foreign-residents-in-japan-as-work-visas-rise.html (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Lai, Mirko, Marcella Tambuscio, Viviana Patti, Giancarlo Ruffo, and Paolo Rosso. 2019. Stance polarity in political debates: A diachronic perspective of network homophily and conversations on Twitter. Data & Knowledge Engineering 124: 101738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurence, James, Akira Igarashi, and Kenji Ishida. 2022. The dynamics of immigration and anti-immigrant sentiment in Japan: How and why changes in immigrant share affect attitudes toward immigration in a newly diversifying society. Social Forces 101: 369–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarsfeld, Paul F. 1954. Friendship as a social process: A substantive and methodological analysis. Freedom and Control in Modern Society 18: 18–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Farrer, Gracia. 2020. Immigrant Japan: Mobility and Belonging in an Ethno-Nationalist Society. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lubashevskiy, Vasily, Seval Yurtcicek Ozaydin, and Fatih Ozaydin. 2023. Improved link entropy with dynamic community number detection for quantifying significance of edges in complex social networks. Entropy 25: 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainichi Japan. 2024. Ukrainian-Born Miss Japan Rekindles an Old Question: What Does It Mean to Be Japanese? Mainichi Japan, January 29. Available online: https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20240129/p2g/00m/0na/011000c (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Matakos, Antonis, Evimaria Terzi, and Panayiotis Tsaparas. 2017. Measuring and moderating opinion polarization in social networks. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 31: 1480–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, Miller, Lynn Smith-Lovin, and James M. Cook. 2001. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology 27: 415–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, Stephen J. 2014. “Well, I’m a Gaijin”: Constructing identity through english and humor in the international workplace. Journal of Pragmatics 60: 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, Ali, and Onur Varol. 2024. Turkishbertweet: Fast and reliable large language model for social media analysis. Expert Systems with Applications 255: 124737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, Ali, Nihat Mugurtay, Yasser Zouzou, Ege Demirci, Serhat Demirkiran, Huseyin Alper Karadeniz, and Onur Varol. 2024. First public dataset to study 2023 turkish general election. Scientific Reports 14: 8794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkei Asia. 2024. Japan to Make It Easier to Revoke Foreigners’ Permanent Residency. Nikkei Asia, February 9. Available online: https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Japan-immigration/Japan-to-make-it-easier-to-revoke-foreigners-permanent-residency (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- One World Language Services. 2024. What Is an Alt? Fukuoka: OWLS Co., Ltd. Available online: https://en.owlsone.co.jp/what-is-an-alt/ (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary. 2024. Echo Chamber. Oxford: Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary. Available online: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/us/definition/english/echo-chamber (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Roberts, Glenda S., and Noriko Fujita. 2024. Low-skilled migrant labor schemes in Japan’s agriculture: Voices from the field. Social Science Japan Journal 27: 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, Yuna. 2021. ‘Others’ among ‘us’: Exploring racial misidentification of Japanese youth. Japanese Studies 41: 303–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, Stefan, and Felix Roedder. 2021. Gaijin invasion? A resource dependence perspective on foreign ownership and foreign directors. International Business Review 30: 101861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Jiwon, Hwajin Lim, and Jiyeon Shin. 2024. Prejudice and discrimination experienced by high-skilled migrants in their daily lives: Focus group interviews with Tokyo metropolitan area residents. Asian Journal of Social Science 52: 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shircliff, Jesse Ezra. 2024. Lifestyle migration and native speakerism in Japan: The case of NOVA Eikaiwa. Socius 10: 23780231241233231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, Cass R. 1999. The law of group polarization. In University of Chicago Law School, John M. Olin Law & Economics Working Paper. Chicago: The University of Chicago Law School. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, Cass R. 2001. Echo Chambers: Bush v. Gore, Impeachment, and Beyond. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, Taku. 2023. Precarity and hope among asylum seekers in Japan. In Sustainability, Diversity, and Equality: Key Challenges for Japan. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 125–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahara, Kanako. 2024. Ukraine-Born Miss Japan Relinquishes Crown Following Affair. The Japan Times, February 6. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2024/02/06/japan/society/miss-japan-karolina-shiino-resigns/ (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- The Mainichi News. 2024. Editorial: It’s Time the Gov’t Said It Loud and Clear: Japan Is Now an Immigrant Nation. May 7. Available online: https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20240507/p2a/00m/0op/020000c (accessed on 7 June 2024).

- Toriumi, Fujio, and Tatsuhiko Yamamoto. 2024. Informational health–toward the reduction of risks in the information space. arXiv arXiv:2407.14634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usui, Shohei, Mitsuo Yoshida, and Fujio Toriumi. 2018. Analysis of information polarization during Japan’s 2017 election. Paper presented at the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Seattle, WA, USA, December 10–13; pp. 4383–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westfall, Jacob, Leaf Van Boven, John R. Chambers, and Charles M. Judd. 2015. Perceiving political polarization in the united states: Party identity strength and attitude extremity exacerbate the perceived partisan divide. Perspectives on Psychological Science 10: 145–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, Sakura. 2022. Transnational migrants and the socio-spatial superdiversification of the global city Tokyo. Urban Studies 59: 3382–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardi, Sarita, and Danah Boyd. 2010. Dynamic debates: An analysis of group polarization over time on Twitter. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 30: 316–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtcicek Ozaydin, Seval. 2018. The right of vote to Syrian migrants: The rise and fragmentation of anti-migrant sentiments in Turkey. Paper presented at the Asian Conference on Media, Communication & Film, Tokyo, Japan, October 9–11; pp. 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yurtcicek Ozaydin, Seval, and Fatih Ozaydin. 2021. Deep link entropy for quantifying edge significance in social networks. Applied Sciences 11: 11182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurtcicek Ozaydin, Seval, and Ryosuke Nishida. 2021. Fragmentation and dynamics of echo chambers of Turkish political youth groups on Twitter. Journal of Socio-Informatics 14: 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).