Abstract

In this article, we contend that understanding Brazil’s current communicative landscape requires a closer examination of the relevance of legacy media outlets, challenging the widely accepted “traditional media bypass” thesis, which posits that social media platforms have overtaken traditional media as the primary influencers of political discourse, an argument often used to explain the rise of extreme-right ideologies across different national contexts. In order to test the association between voting preferences and the use of different types of media, we employ logistic regression analysis using data from a recent survey that includes numerous questions about the information and media consumption habits of Brazilian voters. Our findings highlight that legacy media, particularly broadcast TV channels like Globo, Record, and SBT, remain dominant in Brazil as sources of political information. Contrary to the bypass thesis, Bolsonaro’s supporters, while favoring social media, also consume significant amounts of legacy media. Analysis reveals stark differences in media preferences between the supporters of different political candidates, challenging the notion of an exclusive reliance on social media by right-wing supporters. The data also indicate nuanced media consumption habits, such as a preference for certain TV channels and fact-checking behaviors, underscoring the complex interplay between legacy and social media.

1. Introduction

On 3 October 2023, the newspaper O Estado de São Paulo inaccurately reported that Lula had directly facilitated the release of over a billion USD to Argentina, purportedly to impede the far right-wing candidacy of Javier Milei against the then-incumbent candidate Sergio Massa. This report was refuted by the Brazilian government the following day. Despite governmental efforts to rectify the disinformation, false news rapidly disseminated. The “Observatório das Redes” report on this incident of fake news indicates that the most-interacted-with posts perpetuated the erroneous narrative against Lula. The majority of these posts echoed the initial report, levying criticism at Lula for allegedly attempting to meddle in Argentina’s elections. Some insinuated that the Brazilian president was engaging in a fiscal responsibility crime, while others accused him of endorsing dictatorships. Notably, Javier Milei himself contributed to the discourse, posting a critique of Lula’s supposed interference in the Argentine election, which became one of the most accessed posts on the topic in Brazil. Furthermore, Brazilian far-right profiles have lauded the Argentine candidate Javier Milei, labeling him as the “Argentine Bolsonaro” and asserting his endorsement by the Brazilian right.

This event is one of many that shows the synergy between the news media coverage of politics in Brazil presented by legacy media outlets and influencers in the social networks in promoting the circulation of disinformation. Most of the academic literature on the recent rise of the far right1 in Brazil ascribes a prominent role to political communication and, at the same time, seems to fall prey to the facile explanation that the internet and social media are responsible for such a development. In other words, they reproduce the interpretation that extreme-right forces, chiefly Jair Bolsonaro and his followers, intensively invested in social media communication in order to obtain direct access to the public, thus bypassing the traditional media.

In this article we argue that while that might have been the case in the 2018 presidential election won by Bolsonaro, for understanding the Brazilian communicative environment of the 2022 electoral campaign, a more complex and nuanced picture must be drawn, one that also takes into consideration the role of legacy media outlets. The chief problem of taking the “traditional media bypass thesis” as a stable fact of extremist right-wing politics in Brazil is to discount the important role played by legacy and partisan media in the consumption of political communication by present-day Brazilians, and especially by Bolsonaro’s supporters. Instead of analyzing the supply side of political communication, that is, the content and strategies produced by politicians, parties, and influencers, we look into the information consumption habits of Brazilian voters through the statistical analysis of survey data collected in early 2023, that is, right after the presidential election of October 2022.

In the following section, we delve into the international literature addressing the rise of the far right and its interplay with social media. Subsequently, we analyze the reception of this debate, highlighting the prominence of the “traditional media bypass thesis” in the literature on the Brazilian case. Next, the methodology is presented, followed by a discussion about the issues (variables) that may contribute to a better understanding of the relationship between legacy media and social networks. Finally, we summarize the findings by showing the untenability of a radical interpretation of the “traditional media bypass thesis” and argue for the need for analytical approaches that explore the interaction between legacy and social media in the dissemination of political communication.

2. The Far Right and Social Media

The proliferation of social media platforms on the internet has transformed the landscape of political communication, dramatically expanding the creation, circulation and consumption of content. Echoing the initial optimism surrounding the internet’s emergence two decades earlier, commentators placed high expectations on these new communication technologies to democratizing the public sphere (Bingham and Conner 2010; Stieglitz and Dang-Xuan 2013). Gradually, however, the patterns of political mobilization, protest, and electoral competition started being affected by these novel forms of communication, not always in a benign and progressive fashion. Some innovations seem to foster deliberative democracy, but others are driven by extreme-right groups whose agenda includes delegitimizing democratic institutions, attacking human rights and minority groups, and advocating for authoritarian political solutions.

In fact, social media platforms, such as Twitter (now X), YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram, have been instrumental in disseminating extreme-right content to a broader audience. This led to the formation of stable communities and facilitated the creation of international networks among groups with similar inclinations (O’Callaghan et al. 2012; Robles et al. 2019). In essence, these platforms enabled the self-organization of networks of extreme-right content producers (influencers) with populist, misogynistic, homophobic, and nationalist framings, along with actively connected followers who repost the received material, thus promoting its dissemination (Kluknavská and Hruška 2018).

In addition to the new opportunities for expression and organization available to extreme-right groups, the heavily commercial logic of content propagation algorithms operated by the social networks favors the creation of informational bubbles, gathering people with similar preferences (Lifland 2013; Bozdag and van den Hoven 2015; Matakos and Gionis 2018; Nikolov et al. 2018).

In turn, the media practices of extreme-right groups reinforce their internal organization, hierarchy, and ideological consistency, aiding them in consolidating their profile and becoming recognizable in public spaces (Castelli Gattinara and Bouron 2020). Visual communication on platforms like Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, etc., allows extreme-right groups to renegotiate nationalist, fascist, and Nazi doctrines in contemporary cultural contexts, potentially revitalizing them (Forchtner and Kølvraa 2017). Furthermore, the disruptive and aggressive communication style adopted by these groups contributes to the amplification of their messages, as platform algorithms tend to promote such content (González-Bailón et al. 2022), thereby benefiting the far right at the expense of groups with different ideological orientations.

Many authors also accuse social media of contributing to the growth of political polarization in various national contexts, as extreme and polarized beliefs emerge and spread, influencing the voting behaviors of both extremist and moderate voters (Levy and Razin 2020; Aruguete et al. 2020; Bail et al. 2018; Kearney 2019), while others offer a more nuanced perspective on the capacity of social media to promote ideological segregation and affective polarization (Gentzkow and Shapiro 2011; Guess et al. 2023). However, the bias in favor of extreme-right content introduced via social media is only part of the present day political communication landscape. It is also necessary to consider the role of legacy media, which continues to operate worldwide, either through its traditional channels or via its internet pages and social media sites. There is evidence that left-wing and right-wing activists use digital and traditional media differently to achieve political goals. For example, Freelon et al. have noted that while left-wing actors primarily engage in “hashtag activism” and offline protests, right-wing groups manipulate the traditional media, migrate to alternative platforms, and strategically work with partisan media to disseminate their messages. This difference extends to the content of communication, with the right embracing strategic disinformation and conspiracy theories more than the left (Freelon et al. 2020; González-Bailón et al. 2022).

The literature on political communication is replete with works showing the influence of media bias on the formation of citizens’ political preferences (Baum and Groeling 2008; Gregory and Ali 2017; Ceron and Memoli 2015). However, this scenario has become more complex with the rapid growth of social networks as a source of political information. Studies that focus on the supply of information, such as Amani Ismail’s case study on the interplay between social networks and local traditional media during the extreme-right protests in Ferguson (2014) and Charlottesville (2017), demonstrate that journalistic coverage can be significantly influenced by agendas and themes originating from social networks (Ismail et al. 2019). On the demand side, there is evidence that, nowadays, social networks and traditional media jointly influence the formation of political preferences and identities (Ejaz 2021).

3. The Case of Bolsonaro

Almost everything that has been said above about the development of political communication in the international scenario in recent years applies to the case of Brazil. The rise of Jair Bolsonaro to power is often portrayed as an example of the role of social media in contemporary populism, although it is questionable whether he embodies the characteristics of a typical populist (Feres Júnior et al. 2022). A relatively unknown extreme-right politician, he secured victory in the 2018 presidential election with a campaign that was heavily reliant on social media and messaging services, particularly Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp (Nicolau 2020), and nearly achieved re-election in 2022.

Several authors have argued that Bolsonaro’s political communication strategy is focused on leveraging social media for direct communication with supporters, bypassing the traditional media channels. In fact, a common thread in the burgeoning academic literature on Bolsonarism, which flourished following his 2018 election win, is the attribution of the “Bolsonaro phenomenon” to the direct influence of social media. This argument often echoes the international literature on the role of social media and the rise of the extreme right: social media allows for the widespread dissemination of disinformation, which, in turn, benefits the political agents who are more prone to use disinformation in their communication strategies, namely the extreme right, at the same time, undermining the credibility of traditional media outlets and the public trust in the news (Albuquerque 2020).

In fact, the interpretation that the traditional press was bypassed by social media in Brazil, more specifically, by Bolsonaro, is common in the literature (Feltran 2020; Baptista et al. 2022; Mendonça and Caetano 2021). Drawing from an online ethnography of pro-Bolsonaro WhatsApp groups and other platforms such as Twitter and Facebook, Cesarino argues that the anti-structural affordances of social media played a decisive role in the proliferation of populist discourse. This was achieved by suspending markers of social structure, fostering the formation of new communities united by shared ultraconservative cultural values, and influencing the emergence of new political subjectivities, which did not depend on legacy media for maintaining their identity (Cesarino 2020).

The “traditional media bypass thesis” has also been used by authors that approached Bolsonarism as a sociological phenomenon, describing it as a social movement that adopted the communicative strategy of counterpublicity to conquer the Brazilian post-bourgeois public sphere, reversing its historical trajectory toward increasing democracy participation and social inclusion. In fact, the concept of counterpublicity contains the idea of communicative behavior the disrupts the usual channels and patterns of communication (Rocha et al. 2021; Solano 2018).

Indeed, the analysis of quantitative survey data shows that Bolsonaro’s supporters were more likely to use social media as sources of political information compared to the supporters of other candidates (Amaral 2020). That did not preclude some authors who studied Bolsonarism using statistical methodologies to assume the “traditional media bypass thesis” without even controlling for variables, such as media and information consumption habits (Rennó 2020; Almeida and Guarnieri 2020; Amaral 2020).

The ascension of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil marks a significant shift in the nation’s political landscape. Political analysists were all taken by surprise given that the most competitive candidates in presidential elections from 1989 to 2014 always had the largest, most organized, and most powerful parties or party coalitions behind them (Nicolau 2020). But Bolsonaro won the election running on the ticket of a minuscule party, with no strong coalition of parties to back up his campaign, and with very few “official” resources to use for political communication. At the same time, his presence in social media and messaging services, such as Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp, was massive as compared to the other candidates. That allowed him to run a campaign exploring a range of themes that included a right-wing conservative discourse (Azevedo and Robertson 2022), a neoliberal response to economic crises (Grigera et al. 2019), a strong “law and order” and anticorruption message, and a reaction against the perceived failures of the left-wing government (Hunter and Power 2019) couched on the exploration of widespread resentment toward established political parties (Saad-Filho and Boffo 2021).

During his presidency, Bolsonaro’s communication strategy was, in part, a continuation of that adopted during the campaign, based on the promotion of intense polarization, disinformation, and the defense of controversial policies (Medeiros Teixeira and Couto Junior 2021; Albuquerque 2021). However, now he had additional means to reach his supporters, aligned legacy media channels, such as the Record, Rede TV, and SBT television networks, the Jovem Pan cable news channel, the Jovem Pan radio network, and a plethora of regional and local media channels that were coopted by his political group through means that are not yet clear (Oliveira and Martins 2021).

The context of the 2022 election differed significantly from the 2018 election, which was won by Bolsonaro. In 2018, he was a relatively unknown figure, positioning himself as an outsider. By 2022, he had become the incumbent president, facing criticism for his administration’s poor management of the COVID-19 pandemic and an economic crisis. His main opponent in 2018 was Fernando Haddad, a younger politician from the Workers’ Party. In contrast, in 2022, he faced Lula, Brazil’s most prominent political figure. The 2018 public debate was largely shaped by the media coverage of Operation Lava Jato, which led to Lula’s imprisonment and barred his presidential candidacy. However, in 2022, following the collapse of Operation Lava Jato and the overturning of Lula’s convictions, issues like unemployment, high inflation, and sluggish economic growth returned to the forefront of the political debate.

The evolution of Brazil’s political and ideological landscape shares similarities with that of the United States; while the right has become more radicalized and anti-establishment, the left has largely maintained its position. The Workers’ Party (PT) has been a prominent force in the Brazilian political party system for decades, which is simultaneously the most supported and most reviled (Samuels and Zucco 2018). Initially, the PT advocated a socialist agenda focused on labor. However, after four consecutive terms in power starting in 2002, the party shifted towards a social democratic stance, moving to the center left. Despite this ideological shift, there has been a notable increase in ideological and affective polarization, especially on the right side of the political spectrum, beginning with the protest wave in 2013 (Fuks and Marques 2023; Fuks et al. 2021). Therefore, in the October 2022 elections, Brazilian voters faced a choice between the popular social democrat Lula and the equally popular extreme-rightist Bolsonaro, who was then representing the Liberal Party (PL).

The media landscape of Brazil has been profoundly affected by the rise of the internet and social media. Before the advent of digital media, mass communication in the country was in the hands of an oligopoly of family-owned media conglomerates lead by Grupo Globo, the largest and most powerful of them all. The academic literature of media studies in Brazil has extensively analyzed and documented the anti-left bias of the political journalism produced by the most powerful media outlets at least since Brazil’s return to democracy in the 1980s (Azevedo 2017). While presenting themselves as the champions of American-style professional journalism, these media operations produced content that harmed candidates on the left, chiefly from the PT, and benefited candidates on the right and center right (Colling 2004). But Bolsonaro was not favored by the key media companies such Globo and Folha de S. Paulo in 2018, receiving coverage during the campaign period that was even more negative than that received by Haddad of the PT (Feres Júnior 2020). On the other hand, some TV networks, such as Record, SBT, and Rede TV, treated Bolsonaro more favorably.

Upon assuming the presidency, he consolidated the support of those outlets and of other regional and local media operations, a fact that is just starting to be explored in the literature (Araújo and Cardoso Soares Da Silva 2023; Porto et al. 2020; Mundim et al. 2022). Most of the analyses produced so far have focused on the supply side of communication, that is, on the content and strategies produced by Bolsonaro and his followers. However, to test the bypass by the social media hypothesis, we intend to focus on the demand side of political communication, that is, on the information consumption patterns and habits of the Brazilian electorate. It is one thing to observe that certain media outlets have adopted a pro-Bolsonaro slant in their news coverage; it is another to verify whether the audiences choose their information sources based on the political orientation of these sources.

4. Materials and Methods

The primary methodology employed in this study is the application of logistic regression to data from a quantitative opinion poll. Other scholars analyzing Bolsonarism as a public opinion phenomenon commonly employ similar statistical tools (Amaral 2020; Rennó 2020; Fuks et al. 2021; Russo et al. 2022; Almeida and Guarnieri 2020). However, these authors typically prioritize demographic and ideological variables to elucidate the preferences for Bolsonaro, often neglecting to examine variables related to the information consumption habits of survey respondents.

The present analysis uses as a source the database of the survey “The Face of Democracy in Brazil—2023” produced by the INCT Institute of Democracy and the Democratization of Communication (IDDC-INCT).2 The interviews were conducted between 22 and 29 August 2023. The statistical sample was comprised of 2500 voters aged 16 years or older. The unique characteristic of this survey, its comprehensive battery of questions regarding information and media consumption preferences, distinguishes it from the limited selection of publicly available polling data sources and made it the ideal choice for this study.

Following the standardization of variables to establish consistent hierarchical values, we employed the glm function (fitting generalized linear models) within the readily available stats package in R to test models of logistic regression (logit). This function excels in fitting generalized linear models by accommodating both a symbolic representation of the linear predictor and a comprehensive description of the error distribution.

Although the model uses ‘Vote for Bolsonaro’ (VB) as the dependent variable and media consumption habits as independent variables, we are not asserting a causal relationship between them. For the current analysis, given the absence of other confirmatory evidence, we should interpret the regression outcomes with caution as they merely indicate associations between certain factors.

We have used ChatGPT 4 to refine certain passages of the manuscript, exclusively for the purpose of enhancing their grammatical correctness. All analyses and arguments found in the article were generated solely by the authors, without the aid of any AI tools.

5. Results

In our regression models the dependent variable is the “Vote for Bolsonaro”. This was obtained by converting the original variable, which contained the responses to voting in the second round of the election, into a binary format. An argument could be made that the voters’ preferences are more authentically reflected in the first round of the election. However, the first round of Brazil’s 2022 presidential election anticipated the second round. This is evidenced by the fact that Lula and Bolsonaro collectively garnered 92% of the votes. Considering that the second round was a direct face-off between these two candidates, it is reasonable to infer that the majority of the ‘no’ responses in the transformed variable (VB) predominantly represent individuals who voted for Lula (Table 1).

Table 1.

Vote for Bolsonaro.

The survey questionnaire contains a battery of eleven questions related to information consumption habits and preferences, out of which seven pertain directly to the subject of this article. The most important one is the preferred type of media for obtaining political information. As Table 2 shows, broadcast TV news is the preferred channel for obtaining political information. If the combined use of social networks, internet sites, blogs, and Google Search is considered, we would have a close match. However, other types of media, such as print newspapers, magazines, and radio broadcasts, can be classified as ‘traditional’. This inclusion puts legacy media consumption ahead of social media. Furthermore, the data do not discriminate the consumption of political information from websites and news portals on the internet owned by big media companies, such as Globo’s G1 (Quesada Tavares and Goulart Massuchin 2017). In sum, if all is taken into account, it is reasonable to say that legacy media still dominated the supply of political information in 2023 Brazil, a finding that does not match well with the bypass by social media thesis (Table 2).

Table 2.

Preferred source of political information.

When we cross the media consumption information with voting preferences in the second round of the 2022 presidential election, significant differences appear (Table 3).

Table 3.

Preferred source of political information about voting.

Bolsonaro supporters tend to receive political information from social media and the internet almost twice as much as those who voted for Lula. On the other hand, Lula supporters rely almost twice as much on legacy media for obtaining political information than Bolsonaro’s. It should be noted, however, that around 30% of Lula’s voters give priority to social media and the internet, while a similar proportion of Bolsonaristas identify legacy media (TV news, newspapers, and magazines) as their preferred source of information. Thus, although Bolsonaristas indeed prefer social media for obtaining political information, we are far from having a situation of exclusivity, as suggested by the bypass thesis.

The concentration of legacy media ownership in Brazil is high, and the media regulation environment is lenient (Pieranti 2006). Notably, there are no restrictions on the variety of media types a single company can own or its market share in specific media services. The Globo Group is particularly prominent, owning an extensive range of media, including broadcast and cable TV channels, radio stations, prominent newspapers, magazines, and online news portals. Lately, TV Globo’s viewership ratings have faced some competition from TV Record, owned by Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus, Brazil’s largest Pentecostal denomination, and SBT, controlled by the conservative media tycoon Silvio Santos (Rebouças 2018). But Globo’s news programs still have a solid leadership over the competition, both on broadcast and cable television.4

Historically, Lula and the Workers’ Party (PT) have been subjected to consistently negative coverage by the media outlets of the Globo Group and other mainstream media, as extensively documented in the academic literature (Feres Júnior and Sassara 2016; C Mont’Alverne and Marques 2018; Azevedo 2017). Bolsonaro has similarly experienced unfavorable news coverage from Globo since his 2018 electoral campaign and throughout his presidency (Feres Júnior 2020). However, the political strategies employed by these figures in response to the perceived media bias have significantly differed. While Lula and the Workers’ Party (PT) have generally avoided creating substantial alternative media channels, typically responding to the challenges by either ignoring them or through official press statements, Bolsonaro and his supporters have proactively worked to establish a communication network. This network includes internet platforms and social media influencers, loosely coordinated around what has been termed the “Cabinet of Hate” (Mello 2020). It also encompasses media outlets owned by sympathetic evangelical and conservative Catholic leaders, along with various legacy media platforms. These platforms include major channels like Record, SBT, Rede TV, and hybrid legacy/partisan outlets, such as FM radio Jovem Pan, cable channel Jovem Pan News, Gazeta do Povo, O Antagonista, among others.

Bolsonaro’s communication strategy aimed at establishing his own distinct communicative sphere places special emphasis on openly rejecting Globo and accusing it of disseminating fake news against him. This strategy also extends to other prominent outlets, such as the newspapers Folha de S. Paulo and O Globo, but it is particularly focused on TV Globo (Fávero 2019; Feltrin 2020).

When the respondents of the 2023 survey were asked whether they identify TV Globo as a source of fake news, their responses were as follows (Table 4):

Table 4.

Globo as source of fake news.

The perceptions of TV Globo appear to be closely correlated with the voting preferences. Among Lula’s voters, the opinions are split evenly regarding Globo. However, among Bolsonaro’s supporters, those who consider Globo a purveyor of fake news significantly outweigh those who do not by a notable 41 percentage points. Interestingly, the perspectives of non-voters on this issue are more aligned with Lula’s supporters than with Bolsonaro’s.

The perceptions about TV Record as a source of fake news are quite different, as shown below (Table 5).

Table 5.

Record as source of fake news.

Supporters of both the candidates displayed a similar level of skepticism towards TV Record, suggesting a general cautious attitude toward the network. When comparing the perceptions of Globo and Record, the supporters of Lula perceived Globo as more likely to broadcast “fake” news compared to Record, possibly due to Globo’s history of unfavorable coverage towards their favored candidate. Conversely, the supporters of Bolsonaro exhibited opposite views concerning these two networks, which is indicative of their deep-seated skepticism towards Globo. The p-value of 0.2114 indicates that the differences observed in the table are not statistically significant at the level of 5%. This implies that the perception of Record as a source of fake news is not significantly different among Lula’s voters, Bolsonaro’s supporters, and the non-voters. Thus, we will discard this variable.

The respondents were also requested to identify the types of sources they consult upon encountering news items they suspect to be false (Table 6).

Table 6.

Sources for checking news.

The results indicate that the supporters of Bolsonaro are more likely to seek confirmatory information on social media and the internet when they encounter news they suspect to be false compared to Lula’s supporters. In contrast, they place considerably less trust in legacy media for this purpose than do the supporters of Lula.

The survey also included a question asking respondents to name their preferred TV channel for viewing political news (Table 7).

Table 7.

Favorite TV channel.

The data reveal a distinct pattern in media preferences among the supporters of Lula and Bolsonaro. Lula’s supporters are more than three times as likely to choose Globo for their political news compared to Bolsonaro’s supporters, which is a trend that extends to GloboNews, Globo’s cable news channel. Conversely, only 13% of Lula’s supporters favor TV Record as their primary news source compared to 36% of Bolsonaro’s supporters, reflecting another 3:1 ratio. Bolsonaro’s followers also show a preference for SBT, another network aligned with Bolsonaro, at twice the rate of Lula’s supporters. Additionally, 8% of the Bolsonarists favor Jovem Pan News, which is often likened to Brazil’s version of Fox News. Notably, none of the 962 respondents who declared voting for Lula selected Jovem Pan News as their preferred TV channel.

In summary, rather than robustly supporting the “legacy media bypass” interpretation, the data reveal that Bolsonaro’s followers do engage with broadcast TV news, though they are selective about their sources. In the historically politicized media landscape of Brazil, politicians, especially those on the right, may not need to sidestep legacy media entirely if some outlets share their viewpoints and function as steadfast supporters.

As for the least favorite broadcast television channel, the answers were as follows (Table 8).

Table 8.

Least favorite TV channel.

The findings present an almost exact reversal of the list of favorite channels, with Bolsonaro’s supporters showing a strong aversion to Globo, while Lula’s supporters least favor TV Record and SBT for political information. Notably, the preferences of the non-voters for a president fall somewhere in the middle between these two extremes, both in terms of favorite and least favorite TV channels. This middle-ground positioning is consistent across the main TV channels.

The set of independent variables was obtained by converting the original categorical variables with multiple responses into binary variables in the following way (Table 9).

Table 9.

Recoded variables.

We constructed three regression models using ‘Vote for Bolsonaro’ (VB) as a binary dependent variable. Model 1 incorporates only ‘Legacy media’ as the independent variable. Model 2 includes a set of seven independent variables that represent media consumption habits. Model 3 further extends this by adding socioeconomic control variables to the independent variables used in the previous model. These control variables are the religious persuasion, the region of residence, the income level, the gender, and the race of the respondents. The rationale for selecting these specific variables is grounded in the literature that consistently demonstrates their interactions with voting behaviors for Bolsonaro (Almeida and Guarnieri 2020; Rennó 2020; Amaral 2020). Notably, the education level of respondents does not feature among them (Table 10).

Table 10.

Determinants of Vote for Bolsonaro6.

According to Model 1, the individuals who primarily use legacy media as a source of political news are 10.5 percentage points less likely to vote for Bolsonaro. This result, which is highly statistically significant, supports the legacy media bypass thesis to a certain extent. However, the model’s accuracy is poor (0.65) compared to that of the others, and its Cohen’s Kappa value indicates that the model’s performance is equivalent to random chance. The lack of predictive capability and poor overall goodness of fit in Model 1, as opposed to the other two models, suggest that it might be too simplistic for the complexity of the underlying data.

The introduction of other variables related to media consumption significantly improves the accuracy and fit of the analysis, as seen in Model 2. Introducing socioeconomic control variables in Model 3 further enhances these aspects. Therefore, we should focus on the results of Model 3.

Notably, in Model 3, the impact of legacy media preference diminishes to almost a fifth of its value in Model 1 and loses the statistical significance it initially had. Most of this reduction in intensity and significance already occurred in Model 2 with the inclusion of the other media consumption variables. This indicates that when examining media consumption in detail, the broad thesis of Bolsonaro voters bypassing legacy media loses its strength. However, Bolsonaro’s voters are less likely to use legacy media for fact checking than the other voters, with respective probabilities of 25% against 32% (p < 0.01). Although a difference exists, it is not as pronounced compared to the other discrepancies characterizing the media habits of these groups.

Table 2 has already demonstrated that broadcast TV is the preferred source of political information in Brazil. Indeed, the regression results show a significant difference in the preference for broadcast TV as a political news source between Bolsonaro’s voters and others, mostly those who voted for Lula. The probability of the latter group preferring TV is almost twice that of the former, 46% vs. 24% (p < 0.001).

However, there is nuance in how each group consumes broadcast TV for political information. The likelihood of the Bolsonaro supporters perceiving Globo as the main source of fake news (Globo is negative) is 15 percentage points higher than that of the non-Bolsonaro voters (p < 0.001). This trend is further confirmed by the results for favorite and least favorite TV channels. The channels reputed to support Bolsonaro (Record, SBT, Rede TV, and Jovem Pan) are preferred by his voters more than twice as much compared to the other voters—52% against 25% (p < 0.001). Similarly, channels critical of Bolsonaro (Globo and GloboNews) are more intensely rejected by his voters than by others, 35% against 18%, respectively (p < 0.001).

6. Conclusions

The analysis above provides ample evidence to conclude that the traditional press was not entirely bypassed by social media in the context of Brazil’s 2022 presidential election, and this is also true for the subset of Brazilians who voted for Bolsonaro. First, as we have shown, legacy media outlets, particularly broadcast TV channels such as Globo and Record, are frequently accessed by Brazilians for political information. It is true that Bolsonaristas compared to those who did not vote for him obtain more news from social media. However, their substantial engagement with traditional media indicates that the Brazilian political information landscape is more intricate than what a stringent interpretation of the bypass theory would suggest.

Rather than rejecting legacy media and broadcast TV outright, Bolsonaro’s voters appear to be highly selective regarding their preferred information sources. They strongly reject Globo’s channels, while showing a marked preference for networks that have supported Bolsonaro even before the 2018 election. These findings suggest that legacy media was not bypassed by Bolsonaristas, but is consumed in conjunction with social media, sometimes as the primary information source, and sometimes for fact checking suspicious material.

In this paper, we have examined the association between voting preferences and media consumption patterns, while deliberately avoiding causal assertions. Given Bolsonaro’s frequent critiques of the traditional press and other media outlets, it is plausible to assume that his followers might adopt a more critical stance towards the media entities he openly disparages. Conversely, it is equally conceivable that the individuals’ pre-existing media preferences could predispose them to either support or oppose Bolsonaro, influenced by the extent to which their preferred media outlets endorse or criticize him. Both these dynamics are particularly pertinent in the highly politicized media landscape of Brazil. However, the investigation of these potential causal relationships will be deferred to in future research.

Our study did not specifically seek evidence of informational bubbles among Bolsonaristas, as described by Lifland (2013), Bozdag and van den Hoven (2015), and Matakos and Gionis (2018). Nonetheless, it is noteworthy that they tend to prefer social media to fact check information they find suspicious, while other voters prefer legacy media channels. Future research on the Brazilian case should aim to unravel the complex paths different groups adopt for accessing and verifying information, possibly combining social and legacy media, as explored by Ismail et al. (2019) and Ejaz (2021) in other contexts.

While our data do not directly test the connection between social media and increasing political polarization, as argued by Levy and Razin (2020), Aruguete et al. (2020), Bail et al. (2018), and Kearney (2019), they do indicate that present-day Brazilians’ trust in TV channels as sources of political information varies according to their political leanings in a manner that can reasonably be described as ‘polarized’. Bolsonaristas strongly reject Globo, the country’s most popular and powerful media company, a sentiment that is not shared by the rest of the electorate.

Considering the supply side of communication, Freelon et al. (2020) found that the media choices of political content creators in the United States vary according to their ideological orientation. Our analysis shows that, on the demand side in Brazil, there are not only different preferences for types of media, but also for specific outlets within the same medium, as evidenced in the case of broadcast television.

Bolsonaro’s surprising electoral victory in 2018 led many commentators to quickly adopt the ‘bypass thesis’. Indeed, his campaign heavily relied on social media and messaging services to communicate with voters. However, in that context, Record and SBT were already instrumental in promoting his candidacy by providing him with favorable media exposure, a fact that was not taken into account by most of the literature. During his presidency, he consolidated the support of these and other national, regional, and local legacy media outlets.

The chief issue with the legacy media bypass thesis is not its emphasis on the significant role of social media in contemporary communication. Social media has indeed become increasingly vital for political discourse in Brazil and globally. The problem lies in the thesis’s tendency to downplay the enduring influence of traditional media in political communication. This is particularly relevant in Brazil, where broadcast television still is the dominant news source. Additionally, the pronounced politicization of Brazil’s major media companies traditionally allows for political agents to seek their support rather than circumvent them to reach potential followers. As we said above, Bolsonaro managed to garner the support of Record, SBT, Jovem Pan, and many other legacy media operations. However, what distinguishes him from other Brazilian politicians is his strategy of openly politicizing communication, particularly selecting Globo as his primary adversary. He has publicly accused this television channel and its journalists of leftism, Petismo, disregard for traditional moral values, and of being a fake news mill aimed at harming him.

While politicians, particularly those with an anti-establishment rhetoric, naturally attempt to establish direct communication channels with their electorate, their strategic use of legacy media should not be overlooked. The potential to align with at least a segment of traditional media outlets presents a compelling advantage that is unlikely to be disregarded by them.

If the rise of the extreme right threatens democracy, as the evidence suggests, then protecting it requires a deeper understanding of how anti-democratic leaders communicate with their followers. In other words, academic specialists need to pay more attention to the complex interactions among different types of media and to the roles played by traditional and social media in these interactions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.F.J. and B.M.S.; methodology, J.F.J. and B.M.S.; software: J.F.J. and B.M.S.; validation, E.B., J.F.J. and B.M.S.; formal analysis: J.F.J. and B.M.S.; investigation, E.B., J.F.J. and B.M.S.; resources, Feres Junior; data curation, J.F.J. and B.M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F.J., B.M.S. and E.B.; writing—review and editing, J.F.J. and B.M.S.; supervision, J.F.J.; project administration, J.F.J.; funding acquisition, J.F.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by grant number Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), grant number 269597/2023; Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), grant number 408491/2023-0 e INCT Instituto da Democracia e da Democratização da Comunicação, grant number 465535/2014-3.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the fact that opinion polls do not require ethical review according to Brazilian law. Furthermore, the data used in this articles was produced by a third party, the INCT Instituto da Democracia e da Democratização da Comunicação, and not by the authors.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be published by the INCT Instituto da Democracia e da Democratização da Comunicação in the following months. Researchers interested in having access to it may contact the authors directly.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics.

Table A1.

Descriptive statistics.

| Variable | N | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Vot_B | 2558 | |

| ... 0 | 1661 | 65% |

| ... 1 | 897 | 35% |

| legacy_media | 2558 | |

| ... 0 | 1399 | 55% |

| ... 1 | 1159 | 45% |

| negative_Globo | 2558 | |

| ... 0 | 1759 | 69% |

| ... 1 | 799 | 31% |

| legacy_fact_checking | 2558 | |

| ... 0 | 1911 | 75% |

| ... 1 | 647 | 25% |

| political_news_TV | 2558 | |

| ... 0 | 827 | 32% |

| ... 1 | 1731 | 68% |

| TV_favorite_Bolsonaro | 2558 | |

| ... 0 | 1966 | 77% |

| ... 1 | 592 | 23% |

| TV_least_favorite_Bolsonaro | 2558 | |

| ... 0 | 1958 | 77% |

| ... 1 | 600 | 23% |

| Religion | 2558 | |

| ... Catholic | 1307 | 51% |

| ... Evangelical | 799 | 31% |

| ... No religion, atheist | 207 | 8% |

| ... Other | 245 | 10% |

| Income | 2558 | |

| ... 0–1 MW | 570 | 22% |

| ... 1–2 MW | 469 | 18% |

| ... 10+ MW | 100 | 4% |

| ... 2–5 MW | 958 | 37% |

| ... 5–10 MW | 461 | 18% |

| Region | 2558 | |

| ... Center-West | 193 | 8% |

| ... North | 209 | 8% |

| ... Northeast | 690 | 27% |

| ... South | 387 | 15% |

| ... Southeast | 1079 | 42% |

| Gender | 2558 | |

| ... Female | 1343 | 53% |

| ... Male | 1215 | 47% |

| Race | 2558 | |

| ... Non-white | 1828 | 71% |

| ... White | 730 | 29% |

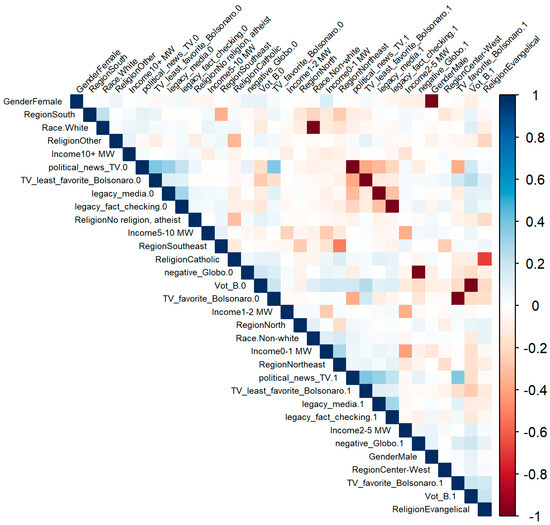

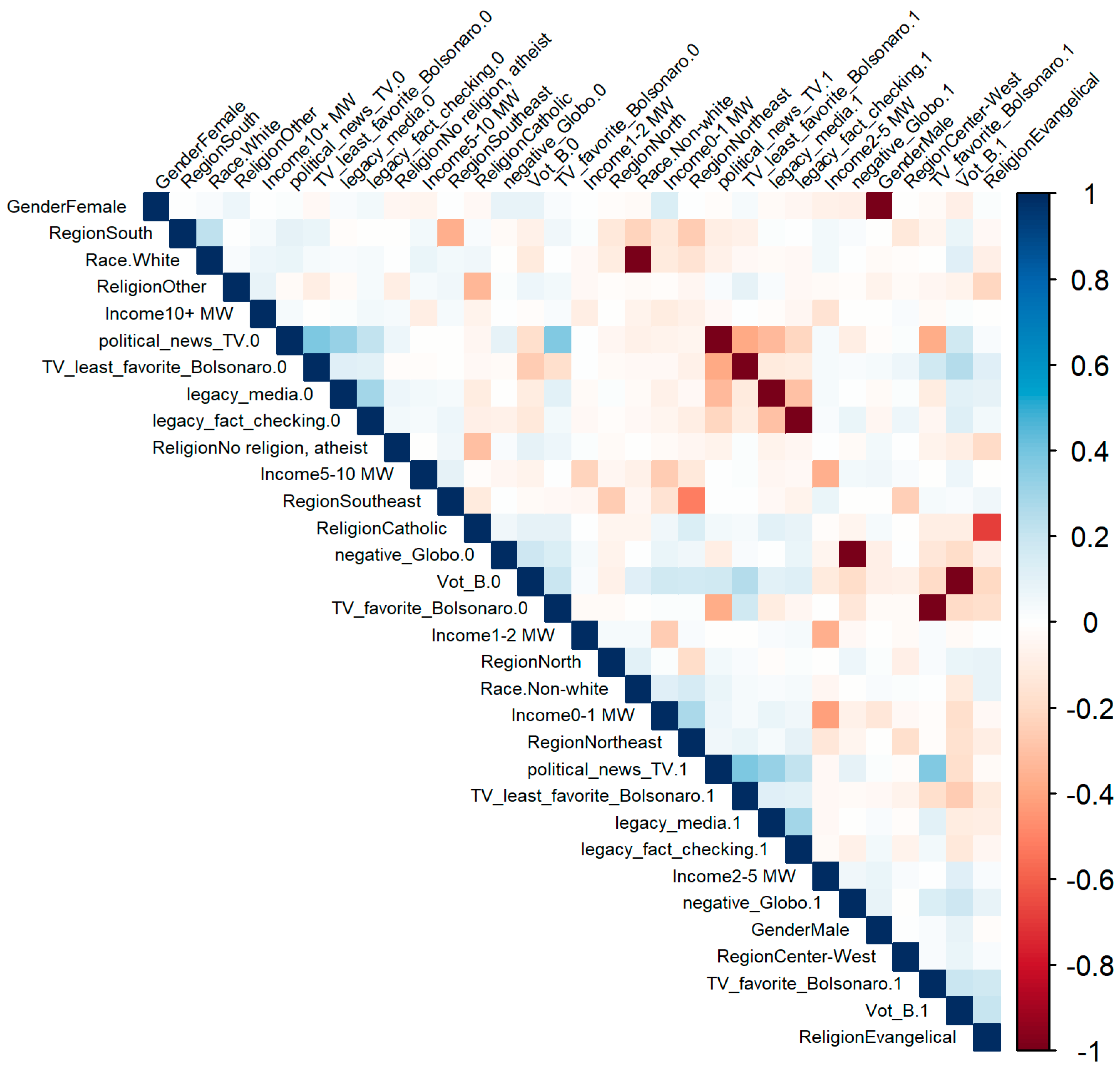

Figure A1.

Correlation matrix.

Figure A1.

Correlation matrix.

Regression Equations

Modelo 1

Modelo 2

Modelo 3

Table A2.

Full results of the regression models.

Table A2.

Full results of the regression models.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | −0.413 *** | −0.250 ** | −0.823 *** |

| (0.055) | (0.078) | (0.220) | |

| legacy_media1 | −0.466 *** | −0.181 | −0.102 |

| (0.085) | (0.099) | (0.105) | |

| negative_Globo1 | 0.831 *** | 0.704 *** | |

| (0.097) | (0.102) | ||

| legacy_fact_checking1 | −0.334 ** | −0.321 ** | |

| (0.116) | (0.122) | ||

| political_news_TV1 | −1.010 *** | −1.020 *** | |

| (0.124) | (0.131) | ||

| TV_favorite_Bolsonaro1 | 1.272 *** | 1.209 *** | |

| (0.123) | (0.130) | ||

| TV_least_favorite_Bolsonaro1 | −0.936 *** | −0.875 *** | |

| (0.149) | (0.155) | ||

| ReligionEvangelical | 0.575 *** | ||

| (0.107) | |||

| ReligionNo religion, atheist | −0.806 *** | ||

| (0.201) | |||

| ReligionOther | −0.260 | ||

| (0.179) | |||

| RegionNorth | 0.195 | ||

| (0.230) | |||

| RegionNortheast | −0.825 *** | ||

| (0.195) | |||

| RegionSouth | −0.286 | ||

| (0.203) | |||

| RegionSoutheast | −0.428 * | ||

| (0.179) | |||

| Income1–2 MW | 0.465 ** | ||

| (0.161) | |||

| Income10+ MW | 0.598 * | ||

| (0.267) | |||

| Income2–5 MW | 0.833 *** | ||

| (0.142) | |||

| Income5–10 MW | 0.845 *** | ||

| (0.163) | |||

| GenderMale | 0.298 ** | ||

| (0.097) | |||

| RaceWhite | 0.487 *** | ||

| (0.107) | |||

| AIC | 3287.649 | 2898.122 | 2711.124 |

| BIC | 3299.342 | 2939.051 | 2828.064 |

| Log Likelihood | −1641.824 | −1442.061 | −1335.562 |

| Deviance | 3283.649 | 2884.122 | 2671.124 |

| Num. obs. | 2558 | 2558 | 2558 |

| Accuracy | 0.65 | 0.71 | 0.75 |

| Kappa | 0 | 0.29 | 0.42 |

*** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

A Kappa value of 0 indicates that the model’s performance is equivalent to a random chance.

Table A3.

Multicollinearity test.

Table A3.

Multicollinearity test.

| Variable | VIF | VIF_CI_ Low | VIF_CI_ High | SE_ Factor | Tolerance | Tolerance_ CI_Low | Tolerance_ CI_High |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| legacy_media | 1.20 | 1.15 | 1.26 | 1.09 | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.87 |

| negative_Globo | 1.05 | 1.02 | 1.12 | 1.02 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.98 |

| legacy_fact_checking | 1.11 | 1.07 | 1.17 | 1.05 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.93 |

| political_news_TV | 1.84 | 1.74 | 1.94 | 1.35 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.57 |

| TV_favorite_Bolsonaro | 1.51 | 1.44 | 1.59 | 1.23 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.70 |

| TV_least_favorite_Bolsonaro | 1.25 | 1.19 | 1.31 | 1.12 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.84 |

| Religion | 1.11 | 1.07 | 1.17 | 1.05 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.93 |

| Region | 1.21 | 1.16 | 1.27 | 1.10 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.86 |

| Income | 1.14 | 1.10 | 1.20 | 1.07 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.91 |

| Gender | 1.04 | 1.02 | 1.11 | 1.02 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.98 |

| Race | 1.10 | 1.06 | 1.16 | 1.05 | 0.91 | 0.86 | 0.94 |

All the VIF values of variables of Model 3 are well below the common thresholds of concern (5 or 10), suggesting that multicollinearity is not likely to be adversely affecting the estimates of the coefficients. The “Increased SE” values are close to 1, and the “Tolerance” values are reasonably high, which further suggests that multicollinearity is not a significant problem in this model.

Notes

| 1 | Since the vocabulary used to describe different types of right-wing politics is not consensual among scholars, and this piece is not focused on the conceptualization of such ideologies, we have chosen to adopt the typology proposed by Cas Mudde (2019). He uses the term “far right” to designate two subsets of ideologies: the extreme right, which rejects the essence of democracy, including popular sovereignty and majority rule, and the radical right, which supports democracy in theory but challenges key institutions and values of liberal democracy (Mudde 2019, pp. 17–18). Much could be said about Bolsonaro’s alignment with one or the other category, but that is not the goal of this article. |

| 2 | One of the authors is a member of the INCT Institute of Democracy and the Democratization of Communication (IDDC-INCT), which funded the survey, and participated directly in designing its questionnaire. |

| 3 | The Chi-squared test is a statistical method used to determine whether there is a significant difference between expected and observed frequencies in one or more categories. It’s commonly applied in hypothesis testing, particularly in contexts involving categorical data such as in our survey database. The test calculates the sum of the squared difference between observed and expected frequencies, divided by the expected frequency for each category. This sum produces the Chi-squared statistic, which, when compared to a critical value from the Chi-squared distribution (depending on the degrees of freedom and the desired confidence level), helps in deciding whether to reject or not reject the null hypothesis. |

| 4 | Based on information from Kantar IBOPE Media, which is a market research company focusing on media measurement and analytics, as of August 2023, the average viewership of Jornal Nacional, the principal daily news program of Globo, was 3.5 times higher than that of Jornal da Record, the main daily news program on TV Record. The viewership for cable television in Brazil is notably lower compared to broadcast TV. Within the small but competitive market of news cable channels, Globo News consistently achieves a viewership that is three to four times higher than that of Jovem Pan News and CNN-Brazil, which are both tied for the second position. See https://www.poder360.com.br/midia/tvs-de-noticias-tem-audiencia-conjunta-de-2484-mil-pessoas/ (accessed on 12 December 2023). |

| 5 | The p-value much higher than the threshold of 0.05 show that there is no statistically significant association between the voter categories (Lula, Bolsonaro, Did not vote) and the responses given to the question about Record being a recognizable source of fake news. |

| 6 | View the complete regression equations in the Appendix A. |

| 7 | See Appendix A for the complete results of Model 3. |

| 8 | Accuracy = correct_predictions/total_predictions. |

References

- Albuquerque, Afonso. 2020. O discurso das fake news e sua implicação comunicacional na política e na ciência. Revista Eletrônica de Comunicação, Informação & Inovação em Saúde 14: 184–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, Bruno da Silveira. 2021. Evangélicos, bolsonarismo e a pandemia fundamentalista. Topoi (rio De Janeiro) 22: 821–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, Maria Hermínia Tavares de, and Fernando Henrique Guarnieri. 2020. The Unlikely President: The Populist Captain and His Voters. Revista Euro Latinoamericana de Análisis Social y Político (RELASP) 1: 139–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, Oswaldo E. do. 2020. The Victory of Jair Bolsonaro According to the Brazilian Electoral Study of 2018. Brazilian Political Science Review 14: e0004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, Bruno Bernardo De, and Bruna Cardoso Soares Da Silva. 2023. A COVID-19 e Os Enquadramentos de Jair Bolsonaro No Telejornalismo Brasileiro: Uma Análise Do Fantástico e Do Domingo Espetacular. Observatorio (OBS*) 17: 107–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruguete, Natalia, Ernesto Calvo, and Tiago Ventura. 2020. News Sharing, Gatekeeping, and Polarization: A Study of the #Bolsonaro Election. Digital Journalism 9: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, Fernando Antònio. 2017. A Grande Imprensa e o PT (1989–2014). São Carlos: Editora UFSCar. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, Mario Luiz Neves de, and Susan Lee Robertson. 2022. Authoritarian Populism in Brazil: Bolsonaro’s Caesarism, ‘Counter-Trasformismo’ and Reactionary Education Politics. Globalisation, Societies and Education 20: 151–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bail, Christopher A., Lisa P. Argyle, Taylor W. Brown, John P. Bumpus, Haohan Chen, M. B. Fallin Hunzaker, Jaemin Lee, Marcus Mann, Friedolin Merhout, and Alexander Volfovsky. 2018. Exposure to Opposing Views on Social Media Can Increase Political Polarization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115: 9216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptista, Érica Anita, Gabriela Hauber, and Maiara Orlandini. 2022. Despolitização e Populismo: As Estratégias Discursivas de Trump e Bolsonaro. Media & Jornalismo 22: 105–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baum, Matthew A., and Tim Groeling. 2008. New Media and the Polarization of American Political Discourse. Political Communication 25: 345–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, Tony, and Marcia Conner. 2010. The New Social Learning: A Guide to Transforming Organizations through Social Media. San Francisco: ASTD Press: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bozdag, Engin, and Jeroen van den Hoven. 2015. Breaking the Filter Bubble: Democracy and Design. Ethics and Information Technology 17: 249–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli Gattinara, Pietro, and Samuel Bouron. 2020. Extreme-right communication in Italy and France: Political culture and media practices in CasaPound Italia and Les Identitaires. Information, Communication & Society 23: 1805–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ceron, Andrea, and Vincenzo Memoli. 2015. Trust in Government and Media Slant: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Media Effects in Twenty-Seven European Countries. The International Journal of Press/Politics 20: 339–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesarino, Leticia. 2020. How Social Media Affords Populist Politics: Remarks on Liminality Based on the Brazilian Case. Trabalhos Em Linguística Aplicada 59: 404–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colling, Leandro. 2004. Os Estudos Sobre o Jornal Nacional Nas Eleições Pós-Ditadura e Algumas Reflexões Sobre o Papel Desempenhado Em 2002. In Eleições Presidenciais Em 2002: Ensaios Sobre Mídia, Cultura e Política. Edited by Antonio Rubim and Albino Canelas. São Paulo: Hacker Editores, pp. 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ejaz, Waqas. 2021. Traditional and Online Media: Relationship between Media Preference, Credibility Perceptions, Predispositions, and European Identity. Central European Journal of Communication 13: 333–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fávero, Bruno. 2019. Bolsonaro Fez 162 Críticas à Imprensa Desde Janeiro; Globo e Folha São Principais Alvos. Aos Fatos. Available online: https://www.aosfatos.org/noticias/bolsonaro-fez-162-criticas-imprensa-desde-janeiro-globo-e-folha-sao-principais-alvos (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Feltran, Gabriel. 2020. The Revolution We Are Living. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 10: 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltrin, Ricardo. 2020. Análise: Entenda Porque Bolsonaro Odeia Tanto a Globo. UOL. Available online: https://www.uol.com.br/splash/noticias/ooops/2020/07/20/analise-entenda-porque-bolsonaro-tem-tanto-odio-da-globo.htm (accessed on 12 December 2023).

- Feres Júnior, João. 2020. Cerco Midiático: O Lugar Da Esquerda Na Esfera “Publicada. Democracia e Direitos Humanos. São Paulo: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. [Google Scholar]

- Feres Júnior, João, and Luna de Oliveira Sassara. 2016. O Cão Que Nem Sempre Late: O Grupo Globo e a Cobertura Das Eleições Presidenciais de 2014 e 1998. Compolítica 6: 30–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feres Júnior, João, Fernanda Cavassana, and Juliana Gagliardi. 2022. Is Jair Bolsonaro a Classic Populist? Globalizations 20: 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forchtner, Bernhard, and Christoffer Kølvraa. 2017. Extreme Right Images of Radical Authenticity: Multimodal Aesthetics of History, Nature, and Gender Roles in Social Media. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology 4: 252–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freelon, Deen, Alice Marwick, and Daniel Kreiss. 2020. False Equivalencies: Online Activism from Left to Right. Science 369: 1197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuks, Mario, and Pedro Henrique Marques. 2023. Polarização e contexto: Medindo e explicando a polarização política no Brasil. Opinião Pública 28: 560–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuks, Mario, Ednaldo Ribeiro, and Julian Borba. 2021. From Antipetismo to Generalized Antipartisanship: The Impact of Rejection of Political Parties on the 2018 Vote for Bolsonaro. Brazilian Political Science Review 15: e0005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentzkow, Matthew, and Jesse M. Shapiro. 2011. Ideological Segregation Online and Offline. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 126: 1799–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Bailón, Sandra, Valeria d’Andrea, Deen Freelon, and Manlio De Domenico. 2022. The Advantage of the Right in Social Media News Sharing. PNAS Nexus 1: pgac137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, J. Martin, and Yurukoglu Ali. 2017. Bias in Cable News: Persuasion and Polarization. American Economic Review 107: 2565–99. [Google Scholar]

- Grigera, Juan, Jeffery R. Webber, Ludmila Abilio, Ricardo Antunes, Marcelo Badaró Mattos, Sabrina Fernandes, Rodrigo Nunes, Leda Paulani, and Sean Purdy. 2019. The Long Brazilian Crisis: A Forum. Historical Materialism 27: 59–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guess, Andrew M., Neil Malhotra, Jennifer Pan, Pablo Barberá, Hunt Allcott, Taylor Brown, Adriana Crespo-Tenorio, Drew Dimmery, Deen Freelon, Matthew Gentzkow, and et al. 2023. Reshares on Social Media Amplify Political News but Do Not Detectably Affect Beliefs or Opinions. Science 381: 404–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, Wendy, and Timothy J. Power. 2019. Bolsonaro and Brazil’s Illiberal Backlash. Journal of Democracy 30: 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, Amani, Gayane Torosyan, and Melissa Tully. 2019. Social Media, Legacy Media and Gatekeeping: The Protest Paradigm in News of Ferguson and Charlottesville. The Communication Review 22: 169–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, Michael Wayne. 2019. Analyzing Change in Network Polarization. New Media & Society 21: 1380–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluknavská, Alena, and Matej Hruška. 2018. We Talk about the ‘Others’ and You Listen Closely. Problems of Post-Communism 66: 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, Gilat, and Ronny Razin. 2020. Social Media and Political Polarisation. LSE Public Policy Review 1: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lifland, Amy. 2013. Right Wing Rising: Eurozone Crisis and Nationalism. Harvard International Review 34: 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Matakos, Antonis, and A. Gionis. 2018. Tell Me Something My Friends Do Not Know: Diversity Maximization in Social Networks. Knowledge and Information Systems 62: 3697–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, Patricia Campos. 2020. A Máquina Do Ódio: Notas de Uma Repórter Sobre Fake News e Violência Digital, 1st ed. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, Editora Schwarcz. [Google Scholar]

- Mendonça, Ricardo F., and Renato Duarte Caetano. 2021. Populism as Parody: The Visual Self-Presentation of Jair Bolsonaro on Instagram. The International Journal of Press/Politics 26: 210–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mont’Alverne, Camila, and Francisco Paulo Jamil Marques. 2018. Seria o Jornalismo Adversário Da Política? Os Editoriais de O Estado de S. Paulo Sobre o Congresso Nacional Brasileiro. Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies/Revue Canadienne Des Études Latino-Américaines et Caraïbes 43: 417–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudde, Cas. 2019. The Far Right Today. Cambridge and Medford: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Mundim, Pedro Santos, Wladimir Gramacho, Mathieu Turgeon, and Max Stabile. 2022. Viés Noticioso e Exposição Seletiva Nos Telejornais Brasileiros Durante a Pandemia de COVID-19. Opinião Pública 28: 615–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, Jairo Marconi. 2020. O Brasil Dobrou à Direita: Uma Radiografia da Eleição de Bolsonaro em 2018. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolov, Dimitar, Mounia Lalmas, Alessandro Flammini, and Filippo Menczer. 2018. Quantifying Biases in Online Information Exposure. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, Derek, Derek Greene, Maura Conway, Joe Carthy, and Pádraig Cunningham. 2012. An Analysis of Interactions within and between Extreme Right Communities in Social Media. In Ubiquitous Social Media Analysis. Edited by Martin Atzmueller, Alvin Chin, Denis Helic and Andreas Hotho. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 88–107. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, Fabrício Roberto Costa, and Cáio César Nogueira Martins. 2021. O discurso eleitoral da Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus e a ascensão de Bolsonaro. PLURAL, Revista do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sociologia da USP 28: 237–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieranti, Octavio Penna. 2006. Políticas para a mídia: Dos militares ao governo Lula. Lua Nova: Revista de Cultura e Política, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, Mauro, Daniela Neves, and Bárbara Lima. 2020. Crise Hegemônica, Ascensão Da Extrema Direita e Paralelismo Político. Compolítica 10: 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada Tavares, Camilla, and Michele Goulart Massuchin. 2017. Interesse Público Ou Entretenimento: Que Tipo de Informação o Leitor Procura Na Internet? E-Compós 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebouças, Edgard. 2018. Lobbying Groups in Communications and Media Policies in Brazil. In Contributions to Management Science. Edited by Datis Khajeheian, Mike Friedrichsen and Wilfried Mödinger. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 175–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennó, Lucio R. 2020. The Bolsonaro Voter: Issue Positions and Vote Choice in the 2018 Brazilian Presidential Elections. Latin American Politics and Society 62: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, José Manuel, Julia Atienza, Daniel Gómez, and Juan Antonio Guevara. 2019. La polarización de ‘La Manada’: El debate público en España y los riesgos de la comunicación política digital. Tempo Social 31: 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, Camila, Esther Solano, and Jonas Medeiros. 2021. The Bolsonaro Paradox: The Public Sphere and Right-Wing Counterpublicity in Contemporary Brazil. Latin American Societies. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, Guilherme Azzi, Jairo Pimentel Junior, and George Avelino. 2022. O Crescimento Da Direita e o Voto Em Bolsonaro: Causalidade Reversa? Opinião Pública 28: 594–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad-Filho, Alfredo, and Marco Boffo. 2021. The Corruption of Democracy: Corruption Scandals, Class Alliances, and Political Authoritarianism in Brazil. Geoforum 124: 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, David J., and Cesar Zucco. 2018. Partisans, Antipartisans, and Nonpartisans: Voting Behavior in Brazil. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Solano, Esther. 2018. Crise Da Democracia e Extremismos de Direita. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung 42. Available online: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/brasilien/14508.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2023).

- Stieglitz, Stefan, and Linh Dang-Xuan. 2013. Social Media and Political Communication: A Social Media Analytics Framework. Social Network Analysis and Mining 3: 1277–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, Marcelle Medeiros, and Dilton Ribeiro Couto Junior. 2021. Na pandemia brasileira, tá tendo boneco de neve no norte e nordeste do país! Pós-verdade em debate. Revista Prâksis 2: 128–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).