Abstract

It is expected that the number of elected female mayors in local government will increase globally, yet no major progress has been registered lately despite the increased focus on the topic. At the European level, no country exceeds 40% female mayors or other leaders of the municipal council (or equivalent), with the highest descriptive representation of 39.1% in Iceland. Following the 2020 elections in Romania, only around 5% of mayors were female with a strong over-representation of male mayors. The current study aims to analyze the male–female distribution of mayors, the degree of re-election, the relationship between the number of candidates and re-election of incumbents, and how these factors impact female political representation at the local level in Romania. Thus, we argue that a high degree of re-election of incumbents may be a barrier to women’s access to the position of mayor. In addition, it is important to determine whether female incumbents are as successful as their male counterparts in being re-elected. While there is an extensive body of literature on incumbency that covers a range of topics, there is a gap in the literature regarding the proposed subject. The present research aims to fill the gap and contribute to a better understanding of the political representation of women in Eastern Europe. We utilized a dataset of Romanian elections from 2008 to 2020 to test our hypotheses. Our findings indicate that during the studied period, more than 95% of mayors were male, the re-election was a frequent occurrence in Romania with a percentage ranging from 70.82% (2008–2012) to 72% (2012–2016 and 2016–2020), and female incumbents were just as likely to be re-elected as their male counterparts.

1. Introduction

In 2023, at the European level, there were only four countries that exceeded the 35% critical mass (Childs and Krook 2008) of female mayors or other leaders of the municipal council (or equivalent): Iceland, Finland, Sweden, and Norway, revealing Nordic dominance (EIGE 2024). The EU-27 average is 18.2% and the most under-represented countries from the group, with less than 10% female mayors (or equivalent), are Romania at 5.3%, Lithuania and Greece at 6.7%, and Cyprus at 7.6%. This may be linked to the fact that, except for Lithuania, the other countries are dominantly orthodox, a denomination that perpetuates the subordination of women (Kizenko 2013), and studies show that in Romania, in the high-standard socio-professional areas—academia and politics—the positions are occupied predominantly by males (Cordoneanu 2012). Even though Romania is politically and socially classified as a democratic society, the dominance of the Orthodox Church, which is, more than other Christian denominations, the least flexible to democratic social changes (Cordoneanu 2012), may influence women’s intention to become involved in politics. At the European level, a lower representation than in Romania is seen in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Turkey, Kosovo, and North Macedonia. In Romania, women’s descriptive representation in politics is low at all levels (Matei et al. 2010; Gârboni 2014), including national and European, and it is decreasing rather than increasing. In parliament, females represent only 18.5% compared to 19.1% in 2016; at the European level, 21.2% are female (Băluță and Tufiș 2021). However, the highest presence of women is observed in the European parliament, while the lowest presence is at the local level. Therefore, parties show a greater interest in promoting women on the external level rather than at the local or national levels (Fedor et al. 2019).

The total of 5.3% female mayors following the 2020 elections translates to 169 seats out of 3186, with 160 of these in the rural area (comune). However, in counties in which the numerical majority is constituted by a minority, there is an absence of female mayors. Thus, this represents a case of intersectional exclusion, particularly in Harghita and Covasna, where the gender discrimination overlaps with minority status. In Romania, the Hungarian minority is geographically concentrated, and after the fall of the communist dictatorship, they founded a party, UDMR, which is governed by the ethnic minority. Ilieș (1998) highlights the fact that after 1990 the idea of ethnic minorities providing the vote to the ethnic parties representing them was revived, but this aspect is not translated into an advantage for females’ representation in politics. Studies suggest that the impact of ethnic parties on the election of women is contingent upon both institutional and cultural factors (Holmsten et al. 2009), which, in turn, restrict women’s access to the position of mayor.

At the international level, the causes of female under-representation in local politics as mayors (or equivalent) have been widely studied, but little attention has been given to the role of incumbency as an additional impediment to female political representation (Shair-Rosenfield and Hinojosa 2014). This is because incumbents are predominantly male (De Paola et al. 2010) and women have to challenge and defeat male incumbents to win office (Schwindt-Bayer 2005). In Romania, the presence of females in politics has been the subject of debate for researchers from diverse fields such as political science (I. Băluță (2010, 2012, 2013, 2015), O. Băluță (2015, 2017), Iancu (2021), Neaga (2012, 2014), Hurubean (2015), Ghebrea (2015), Ghebrea and Tătărâm (2005); geography (Matei et al. 2010; Fedor et al. 2021); and history (Cosma 2002; Jingă 2015), yet the accent was more on the national level than the local (except from Ghebrea and (Fedor and Iațu 2022)) and none of them focused on how the incumbency may influence females’ access to the position of mayor.

Therefore, the present research seeks to address the following questions: (1) What is the re-election rate of incumbent mayors in Romania in local elections in 2012, 2016, and 2020, and how does it impact women’s access to the mayoral position? (2) Are female incumbent mayors as likely to be re-elected as their male counterparts? (3) Is there a correlation between the number of candidates and the incumbent’s chances of being re-elected?

The article covers in following section the incumbency advantage and potential causes, as well as the limited number of studies that examine the degree of re-election of mayors and the female incumbency advantage, which will emphasize the gap and place the study in the European and global context. Following this, the data and the methodology, based on a quantitative approach, will be presented. The results section will analyze the outcomes obtained within the context of Romania and compare them, where applicable, with developments at the European/global level.

2. Literature Review

Despite the fast-growing literature on the incumbency advantage in mayoral elections (Karnig and Walter 1981; Titiunik 2009; Kukovič and Haček 2013; Marschall 2014; De Magalhaes 2015; Freier 2015; Holman 2017) and the considerable number of studies that analyze women’s descriptive representation (Pitkin 1967) at the local level of mayors (Saltzstein 1986; Smith et al. 2012; Carroll and Sanbonmatsu 2013; Ferreira and Gyourko 2014; Maškarinec et al. 2018; Kjaer et al. 2018; Cardenas Acosta 2019; Alberti et al. 2021; Lukáčová and Maličká 2023), there are only a few studies that bridge these two topics. The present research aims to contribute to the existing literature on the topic by examining the degree of re-election of incumbent mayors in Romania and its impact on female mayors. In other words, can the incumbency advantage of male legislators become a disadvantage for their female counterparts in local elections?

Incumbency has been widely studied, and there is evidence that incumbents are strong and advantaged, (Erikson 1971; Garand and Gross 1984; Alford and Brady 1988; Gelman and King 1990; Katz and King 1999; Lee 2008; Butler 2009; Kendall and Rekkas 2012) with a high likelihood of being re-elected. However, most of these studies focused on national elections and were gender-blind. Although mayors play a crucial role within communities, enjoying considerable powers and responsibilities, this type of election has been overlooked. At the mayoral level, incumbent mayors who choose to run for re-elections win in high percentages: 70% USA (Karnig and Walter 1981), 58% in 2005 and 69% in 2009 in Brazil (Moreira 2012), 82.4% in 2010 in Slovenia (Kukovič and Haček 2013), and 72% in 2010 in Slovakia (Sloboda 2014) and in 2011 in Lithuania (Kukovic and Lazauskienė 2018), and in Portugal before the term limit was introduced, on average, 83% of the incumbents ran for re-election and 86% of them were re-elected (Veiga and Veiga 2018). Through the present research, Romania’s case will also be analyzed and placed in an international context. Several studies have analyzed women’s participation in local government as mayors and the female incumbency advantage in Chile, Slovakia, and California such as Shair-Rosenfield and Hinojosa (2014), Sloboda (2014), and Martin and Conroy (2024). The mentioned studies concluded that incumbents are very strong, but this is a disadvantage for women, as they are rarely incumbents. However, according to studies conducted in Chile and Slovakia when female incumbents are re-nominated, they are as likely as male incumbents to be re-elected, confirming Fox and Oxley’s (2003) findings that women are just as likely to be successful as their similarly situated male counterparts. On the other hand, in California, the incumbency advantage does not apply equally to male and female incumbents, as the latter has a lower vote share.

It is important to note that the research conducted thus far has been in countries with different forms of organization, types of elections, and length of the terms (Tybuchowska-Hartlińska 2019), which makes it even more difficult to observe similarities and patterns. Freier’s analysis (Freier 2015) identified three main dimensions as causal for the incumbency effect: the first one is the characteristics of the town, the second is the mayor’s past performance in terms of local economic indicators, and the third is the constitutional setting under which the mayor works.

For the purpose of this research, certain factors were considered relevant in contributing to the re-election of mayors, including the type of election of the mayor, whether the number of terms is limited, and the voting system (one-round/two-round system).

For instance, in Europe, the methods of electing mayors and their responsibilities and powers can vary significantly depending on the country. In the European Union-27, seven countries hold direct elections (Bulgaria, Cyprus, Hungary, Italy, Romania, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia), two hold elections directly or indirectly, depending on the state (Germany and Austria), and the rest are indirect, either elected by the council (Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Sweden) or the mayor is the head of the party list council election (Spain, Portugal, Greece, Croatia, France), or they are appointed by the central government on the recommendation of the municipality (Belgium, Luxembourg, Netherlands) (Czyż 2009; Várnagy and Ilonski 2012; Hambleton 2013; Podolnjak and Gardašević 2013; Hambleton and Sweeting 2014; Tybuchowska-Hartlińska 2019; Górecki and Gendźwiłł 2020; Rajca 2021).

The role of the directly elected mayors has been the subject of much debate. On one hand, they are considered to be more powerful than other types of city leaders (Gash and Sims 2012; Hambleton et al. 2022) and the concentration of power in the hands of one individual can have drawbacks (Hambleton et al. 2022). For example, there is evidence from Lithuania that directly elected mayors lead to a shorter mayoral incumbency, whereas in Slovenia the share of re-elected mayors grew (Kukovic and Lazauskienė 2018). In addition, the one-round system can contribute to a high degree of re-election as the new candidates have little chance of being elected and, with no limitations of the terms, mayors can remain in office for decades. For instance, in France, there are mayors who stayed in office for more than 30 years such as Jacques Mahéas in Neuilly-sur-Marne-DVG and Laurent Cathala in Créteil-PS who were mayors for 37 years. To avoid long tenures in office, some countries have implemented limits on the number of terms that a mayor can serve. For instance, in Brazil, the number of terms has been limited and, at the European level, Portugal and Italy have limited the number of consecutive terms, the latter to one to two terms for municipalities with more than 3000 inhabitants and three terms for the municipalities under 3000 (Veiga and Veiga 2018; Dalle Nogare and Kauder 2017; De Benedetto and De Paola 2019).

There is evidence that long-serving mayors de-mobilize voters, as elections may be seen as a formality to perpetuate the incumbent mayor (Veiga and Veiga 2018); for example, in Portugal, the turnout increased after the implementation of a limited number of terms. In addition, there is a concern that politicians who have been in power for too long might be more likely to develop a set of corrupt relations (Coviello and Gagliarducci 2017). Studies have also found that Romanian mayors, on average, become more corrupt the longer they stay in office (Klašnja 2015).

Certainly, in addition to the local laws that somehow may advantage the re-election of incumbents, there are numerous other (subjective) factors that can contribute to their successful re-election: Leoni et al. (2004) identified some key elements that can influence the re-election of a candidate including their success in the past, personal characteristics, and electoral vulnerability. Moreover, as Mondak (1995) noted they are often competent, and also succeed in attracting funding and contributing to the development of the commune, city, and municipality.

Among the advantages of re-electing incumbents is the argument that they are familiar with the way in which the political function is performed and eliminate the need for an introductory period at the beginning of the term (Kukovič and Haček 2013).

3. Materials and Methods

We evaluate our hypotheses using an original dataset of all candidates for election in Romania during 2012, 2016, and 2020, as well as the elected mayors from 2008, 2012, 2016, and 2020. It must be noted that between 2008 and 2012, there were some administrative re-organizations after which three new administrative units were founded that were excluded from the 2008–2012 calculations as there were no data available for comparison. Additionally, the mayoral elections in 2008 and 2012 used a two-round system (or two-ballot), while the 2016 and 2020 elections used the one-round system, also known as first-past-the-post (FPTP). Under the FPTP system, the candidate receiving the largest share of valid votes is elected, even if s/he receives less than 50% of the total votes.

All the data were collected from the Central Electoral Commission, Romanian Permanent Electoral Authority, and the data from 2020 were collected from Vote Results, a platform developed with the aim of supporting participatory democracy and providing electoral information accompanied by analyses. It is developed by Code for Romania in the Civic Lab, an independent non-governmental organization that is not politically affiliated.

The dataset is of elections for mayors and includes not only candidate names but also their gender, administrative unit, and party. The dataset includes 14,138 candidates for the position of mayor in 2012, 14,041 in 2016, and 13,872 in 2020. Additionally, there were 3183 elected mayors in 2008, and 3186 in 2012, 2016, and 2020.

As for administrative units in Romania, there are 102 (103 if we include the capital) municipalities (municipii), 217 cities (orașe), 2861 communes (comune) that comprise 12.957 villages (sate). In total, there are 42 counties (including the capital) organized in eight regions of development (Table 1). The county represents the traditional administrative-territorial unit in Romania, comprising municipalities, cities, and communes, depending on the geographical, economic, and social–political conditions and the cultural and traditional ties of the population (INS).

Table 1.

Development regions in Romania. Quantitative characteristics.

The municipality is a city with an important economic, social, political, and cultural role, and it usually has an administrative function. Municipalities and cities present a lifestyle and a professional structure of the population specific to urban areas, while the communes include the rural population. According to the 2021 Census, 52.16% of the population reside in urban areas, while 47.83% live in a rural area (Recensământul populației din 2021).

The data were processed manually in Microsoft Office Excel as the variation in name spelling, the use of the father’s initial surname in some cases and not in others, and accent use did not allow accurate results in other programs.

By analyzing the data, we observed the percentage of female mayors, the re-nomination of incumbents, the degree of re-election, and the success rate of male and female incumbents who chose to run for another term.

First, we calculated the female representation in each election as follows:

where

- F—female candidates;

- T—total candidates.

Second, we analyzed and compared the mayors and candidates from two successive terms: 2008 with 2012, 2012 with 2016, and 2016 with 2020. This analysis resulted in two categories of classes and two subcategories: (R) re-elected incumbents; (N) not re-elected incumbents, including (Na) incumbents who ran for re-election but were not successful and (Nb) incumbents did not run for another term. To determine the proportion of incumbents who chose to run for re-election, we used the following formula:

where

- R—re-elected incumbents;

- Na—incumbents who ran for re-election but were not re-elected;

- T—total number administrative units (3186).

We also calculated two key metrics to assess the electoral performance of incumbents: the success rate and the degree of re-election. The success rate of incumbents was calculated by dividing the number of re-elected incumbents by the total number of incumbents who ran for re-election, which is the sum of re-elected incumbents and incumbents who ran but were not re-elected:

where

- R—re-elected incumbents;

- Na—incumbents who ran for re-election but were not re-elected.

- R—re-elected incumbents;

- Na—incumbents who ran for re-election but were not re-elected;

- T—total number administrative units (3186).

Third, we calculated the success rates of male and female incumbents separately. The success rate of female incumbents was calculated as follows:

where

- RF—re-elected female mayors;

- TFI—total number of incumbent female mayors.

Similarly, the success rate of male incumbents (SRMI) was calculated as follows:

where

- RM—re-elected male mayors;

- TMI—total number of incumbent male mayors.

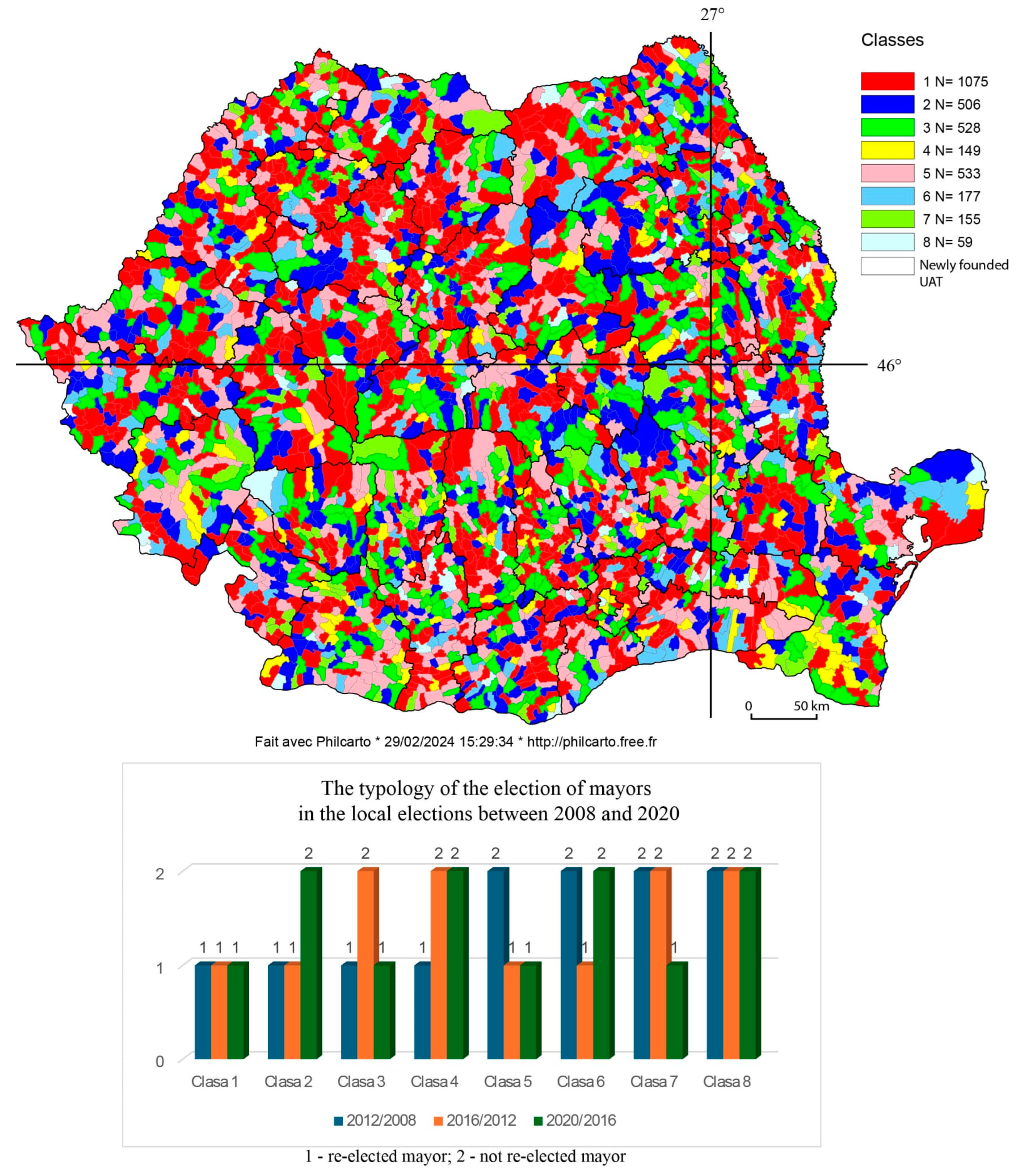

We utilized the data from the studied period for the two categories, (1) re-elected mayors and (2) not re-elected mayors, to generate a cartogram using the open-source Philcarto software V.2020.f (Montpellier, France). This cartogram represented the typologies of re-election for the 2008–2012, 2012–2016, and 2016–2020 elections. The Hierarchical Ascendant Classification highlights the unique features of each class resulted from the representation of the two variables for the studied period.

4. Results

4.1. How Big Is the Incumbent’s Advantage? The Re-Election of Mayors in Romania

Every four years in Romania, incumbent mayors have the opportunity to run for re-election and be re-elected by citizens through a free, equal, secret, and direct voting in a one-round system without any term limitation. Once elected, the mayor is employed full-time; there is evidence from Germany that the incumbency advantage is greater for towns with full-time mayor positions, as they spend more time on the job and have more interactions with constituents (Freier 2015).

In the 2012 local elections, 92% of the incumbent mayors ran for another term, while in 2016 and 2020, 86.12 and 86.94% of incumbents ran for re-election (Table 2). Most of the incumbents who ran for re-election were successful as follows: 76.92% in 2012, 83.60% in 2016, and 82.81% in 2020. This translates to a re-election rate of 70.84 in 2012, 72.00% in 2016, and 72% 2020 for the 3186 administrative units in which the incumbent mayor retained their position. These re-election rates place Romania in close proximity to Slovakia (72% in 2010) and Slovenia (82.4% in 2010), where the mayors are also directly elected. Therefore, the incumbent advantage is confirmed in the Romanian local elections.

Table 2.

The incumbent candidates and their re-election as mayor in Romania in 2012, 2016, and 2020.

A possible explanation for the lower rate of success of the incumbent mayors from 2012 (76.92%), despite the high number of them running for another term, might be the fact that in these elections, the mayor was elected in two rounds, while the following elections used the first-past-the-post election system where a winning candidate might become mayor without majority support (Van der Kolk et al. 2004). Romania adopted the first-past-the-post electoral system for a local election in 2011 (Law No. 129/2011) under the pretext of the economic crisis. Prior to this, the election of mayors was conducted in a two-round system, which was considered too costly by the ruling party PDL (Democrat Liberal Party). There was great debate around the adopted law. On one hand, there were different perspectives of the representants of the parties; some of the PDL (Democrat Liberal Party)1 representants considered the measure as a means to support the economy and argued that voting intent is accurately reflected in the first round, while PNL (National Liberal Party) contended that the law would represent a step away from democracy and democratic values. Meanwhile, PSD (Social Democrat Party) asserted that the election of the mayor in a single round would be conducted with a fourth or maybe even less of the citizens with the right to vote (Chamber of Deputies, 30 May 2011). On the other hand, experts in the field and civil society underlined the effects of this law, and there were unsuccessful initiatives regarding the return to the election of mayors in a two-round system. Consequently, the new system enables voters to express their support for one of the candidates and although s/he does not have the majority of votes cast, s/he can win the position. As a result, the number of candidates for both genders decreased (Fedor et al. 2021), as did the number of parties in the elections, leading to an increase in electoral alliances. The existing literature shows that the first-past-the-post electoral system is very costly for female candidates and fails to elect more women (Shrestha and Mishra 2024), as it favors incumbents. Research from South Africa—for the national elections—suggests that when the first-past-the-post system was used, there was a vivid underrepresentation of small political parties, women, and minorities (Britton 2008; Johnson-Myers 2016).

Furthermore, there is evidence that the more times the incumbent is re-elected, the stronger the incumbency advantage becomes (Sloboda 2014). In Romania, incumbents frequently run for re-election and, as the data show, in 1075 out of 3186 administrative units, the mayor was re-elected in all of the studied elections. Consequently, 32.71% of the Romanian localities continued to have the same administrative leader for (at least) 16 years2. Additionally, within the 1075 administrative units, the electoral data show that the rate of re-election is higher in rural areas with 34.95% of communes that continued with the incumbents in comparison with 25.8% re-elected mayors in cities and 17.64% in municipalities.

Overall, for the studied period of 16 years, covering four local elections, eight distinct classes were identified in relation to the two categories of (1) re-elected mayors and (2) not re-elected mayors. These classes are as follows: (1) administrative units where the mayor served for four consecutive terms, represented with red on the map—1075 units; (2) administrative units where the mayor served for three consecutive terms, represented in navy blue—506 units; (3) administrative units where the incumbent mayor was re-elected in 2008–2012, not re-elected and changed in 2012–2016, and re-elected in 2016–2020 represented with lime on the map; (4) administrative units where the incumbent mayor was re-elected in 2008–2012, but not re-elected in 2012–2016 and 2016–2020, represented with yellow on the map—149 units; (5) administrative units where the incumbent mayor was not re-elected in 2008–2012, but the new mayor was re-elected in 2012–2016 and 2016–2020, faded pink on the map—533; (6) administrative units where the mayor was not re-elected in 2008–2012, but the changed mayor was re-elected in 2012–2016 and not re-elected in 2016–2020, represented with blue sky; (7) administrative units where the incumbent mayor was not re-elected in 2008–2012 and 2012–2016, but the changed mayor was re-elected in 2016–2020, represented in spring green on the map—155 administrative units and, (8) administrative units where there were no consecutive terms of the same mayor represented in light cyan (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The typology of the election of mayors in Romania between 2008 and 2020: the eight classes. Source: (BEC n.d.; ROAEP n.d.), Rezultate Vot, processed data by the authors accessed on 10 January 2024 (made with Philcarto, http://philcarto.free.fr). * authomatically inserted by the Philcarto.

At the NUT2 level, it could be observed that the region with the highest success rate of incumbents was the center region which is characterized by the significant Hungarian minority presence. In two counties within the region, the minority constitutes the majority and is represented by the UDMR, a party which proves to be conservative. In the mentioned region, 90% of the incumbents chose to run for another term and 84,45% of them were successful. In 2016, even if the north-west region had the highest percentage of incumbents who chose to re-run (87.67%), the center region occupied again the first place regarding the success rate of incumbents: out of 83.09% incumbents that ran for re-election, 87.5% were re-elected. In 2020, two regions had the highest rates of incumbent re-election: the north-west region with 84.89% and the center region with 84.55%. At the county level, in 2012, the lowest percentage of incumbents that re-ran for election was 84.62%—Botoșani—and there was one county—Brăila—with 100%. In 2016, it decreased, registering a minimum of 75.32% in Caraș-Severin and a maximum of 94.55% in Călărași; while in 2020, Tulcea was the county with the lowest percentage of incumbents that chose to enter the electoral race again of 72.55%; while the highest was Maramureș—96.05%.

4.2. Can the Number of Candidates Influence Re-Elections?

Counting the number of ‘real’ candidates in elections is complicated, as there are many candidates, but they only win a small share of votes and have no realistic chance of winning the election (Niemi and Hsieh 2002). However, if it is to present the numerical data in Romania at the national level, the average number of candidates is around four in the rural areas and six in the urban areas (Table 3).

Table 3.

Candidates in the 2012, 2016, and 2020 local election in rural and urban areas.

Yet, in the counties in which the Hungarian minority is the majority, the average number of candidates, comprising both rural and urban areas, is less than three, with many rural administrative units having only one candidate running for office. For instance, in 2012, there were 46 administrative units which had only 1 candidate; in 2016, 82 administrative units had 1 candidate, of which 54 were candidates from the Hungarian minority party; while in 2020, 75 administrative units had only 1 candidate. This high number of candidates does not prevent the re-election of incumbents as their positions are very strong, and once mayors manage to establish themselves in town halls, it is quite difficult for challengers to dislodge them (Morales and Belmar 2022). For instance, apart from the capital, Gorj County has the highest average of candidates: 6,04 in 2012, and 6,99 in 2016 and 2020, yet the percentage of incumbents that ran for re-election was 91.43% in 2012, 85.71% in 2016, and 92.86% in 2020, and their success rate was higher than 70%, which shows again that a high number of candidates does not necessarily contribute to the replacement of the incumbent mayor.

In addition, particular attention was paid to the administrative units where the incumbent mayor did not run for another term to observe if the number of candidates increased. However, after analyzing the data a strong link could not be identified, and even if the number increased, their realistic chances of winning the elections are also low because there are cases in which the previous mayor proposes a specific candidate to the party, sometimes even a relative. The mayors of communes/small cities lead the party’s local branches and control the membership. They do not necessarily encourage internal competition, and they may take actions to ensure their control. When comparing the 2008–2012 election cycle to observe the new winners (of the seats for which the incumbents did not run), it could be observed that there are cases in which the newly elected mayor has the same surname as the previous one. In some cases, there was clear evidence in the media that they were relatives: father–son, husband–wife. The titles are suggestive: “following father’s footsteps” or “dynasty at the town hall in a commune” (Adevărul 2011; Tomita 2012; Departamentul Social Mediafax 2013; Boța 2013; 7 Est 2015; Felseghi 2016; Adevărul 2016; Ionescu 2017; Marian 2020; Jurnalul De Arges 2021). One of the female mayors declared in an article, ”To some extent, it is a family heirloom. My father-in-law was mayor for almost 18 years, during Ceaușescu’s time, then my mother-in-law from 2004 to 2012, then, until last year, it was my husband, who was dismissed by order of the prefect, because he had hired my mother-in-law as a councilor to the mayor. While this was allowed at the time, it was later deemed a conflict of interest. Then, in order not to give in, more to the insistence of the residents…” (Felseghi 2016).

4.3. To What Extent Are Incumbent Female Mayors Re-Elected in Compared to Their Male Counterparts?

Can a high rate of re-election of incumbents affect female access to the local government? There is a link, as highly advantaged incumbents are more likely to win the election, allowing fewer seats for newcomers/non-incumbents. Incumbency effects are usually seen as an additional impediment to female political representation (Shair-Rosenfield and Hinojosa 2014; Luhiste 2015), as incumbents are mainly males and are more likely to be re-elected (De Paola et al. 2010). Before analyzing the degree of re-election, it is essential to observe the number of candidacies and the male–female distribution of mayoral seats. In the studied elections, female candidates represented 6.9% in 2012, 8.41% in 2016, and 9.73% in 2020 of the totals of candidacies, placing the country below the “critical mass” threshold even at the candidacy level. During the study period, none of the counties exceeded 20% and there were numerous administrative units that did not have any female candidate: 2350 in 2012, 2230 in 2016, and 2124 in 2020.

In 2012, 705 administrative units had one female candidate, 121 had two female candidates, 9 had three female candidates, and 1 had four. In 2016, 763 had one female candidate, 158 had two female candidates, 28 had three female candidates, and 3 administrative units had four female candidates. In 2020, the number of administrative units with one female candidate increased to 820, 192 had two female candidates, 44 had three female candidates, 5 administrative units had four candidates, and 1 sector of the capital had ten female candidates out of a total of twenty. Additionally, out of the 75 administrative units that had only one candidate, only two were female. Although most political parties do not have a set of formal requirements that a candidate needs to meet (Luhiste 2015), they will seek to select a candidate that will maximize the chance of success (Gallagher and Marsh 1988), thereby preferring the political seniority of the incumbent mayors over a new candidate. As a result, the biggest problem is that women do not have the opportunity to be nominated, as seats are already occupied. The national legislation does not regulate this, and parties, in the absence of quota regulations, fail to propose female candidates. In addition, the predominant male presence within the parties’ gatekeepers at the national or local level can both discourage women’s participation (Sundström and Wängnerud 2016) and lead to the selection of fewer women as viable candidates, as they undermine women (Sanbonmatsu 2002). Consequently, the lack of quotas together with a one-round system and no limitation of terms make it impossible for women to be nominated. Of course, the socio-cultural background also plays a decisive role: after 1989, Romanian citizens proved to be in a continuous transition, with little preoccupation for civil and political life, and women are no exception. Their lack of involvement in local politics, even as active and vocal citizens, doubled by the mentality (theirs and that of voters) that it is a male job, the division of housework, religion, and even the sometimes-violent electoral campaigns make it even more difficult for females to access political positions.

Under these circumstances, the percentage of female mayors slowly increased from 3.7% in 2012 to 5.3% in 2020, showing an over-representation of male mayors. In the 2012 local elections at the national level, 118 women (3.70%) and 3068 men (96.29%) won the mayor’s office from a total of 3186 territorial administrative units. The lowest representation was recorded in the center region with 11 female mayors from a total of 414 administrative units (representing 2.66% at the regional level), while the south-east region registered the highest representation with 18 female mayors elected from a total of 390 administrative units (representing 4.62% at the regional level). Several counties had a 100% male representation (Bucharest, Bistrița-Năsăud, Covasna, Olt, Brașov, Mehedinți, Harghita), namely a total of 416 administrative units (representing 13.06% nationally).

In the 2016 local elections at the national level, 144 women (4.51%) and 3042 men (95.48%) won the mayor’s office from a total of 3186 territorial administrative units. The lowest representation was recorded in the center region, with 13 female mayors from a total of 414 administrative units (representing 3.14% at the regional level), while the north-east region recorded the percentage with the highest representation—36 women mayors were elected from a total of 552 administrative units (representing 6.52% at the regional level). Several counties had a 100% male representation (Bucharest, Bistrita-Năsăud, Brasov, Harghita, Buzău, Timiș), totaling 379 administrative units (representing 11.9% nationally).

In 2020, 169 women (5.3%) and 3017 men (94.69%) won the mayor’s office from a total of 3186 territorial administrative units. The lowest representation was recorded in the south-west development region with 17 female mayors from a total of 448 administrative units (representing 3.79% at the regional level), while the north-east development region recorded the percentage with the highest representation, with 36 women mayors elected from a total of 552 administrative units (representing 6.52% at the regional level). This was closely followed by the western development region with a percentage of 6.5% at the regional level with a number of 21 female mayors elected from a total of 323 administrative units. The only county that had a 100% male representation was Bistrița-Năsăud County (62 administrative units).

Although only 169 women won the mayoral position following the 2020 elections, 104 of them were incumbents. Out of a total of 145 female mayors in 2016, 21 did not run for another term, while 124 ran but 20 were not re-elected. In the latter case, in 12 administrative units out of 20 that changed the mayor, the number of candidates was higher than the county average while in eight lower than the county average. Regarding the 104 administrative units that re-elected the female incumbent mayor must be mentioned that in 63 of them the average number of candidates was lower than the county average and in 41 higher than the county average. Thus, in 61% of the cases the female incumbent mayors were seen as strong and there were few challengers.

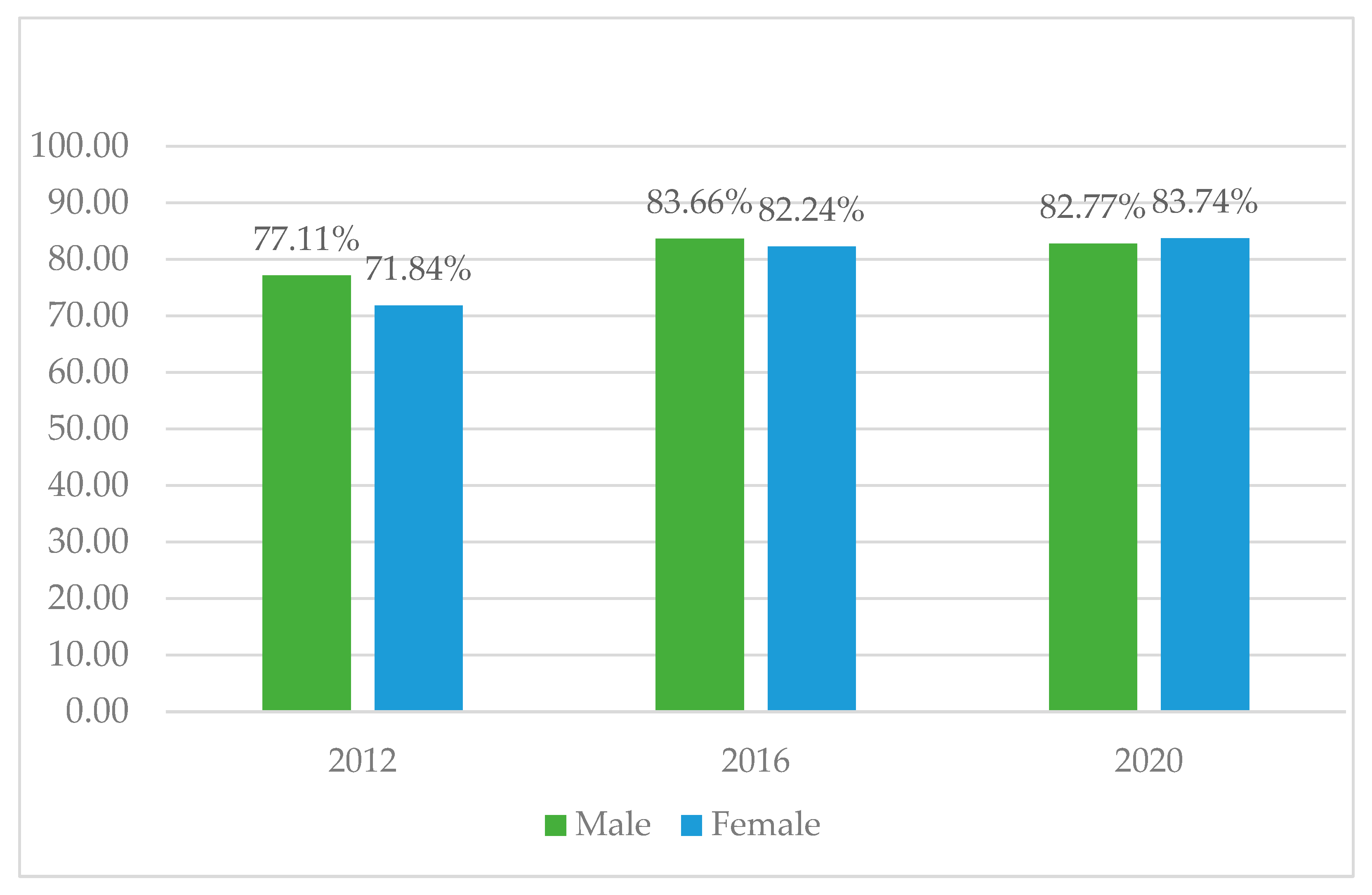

When it comes to re-election, one can observe that the success rates of incumbents both male and female are over 70%, with a notable difference in 2012 in female disadvantage, but very similar in 2016 and with a slight advantage in 2020 (Table 4). Thus, just as in Shair-Rosenfield and Hinojosa’s findings (2014), it is demonstrated that female incumbents are just as likely to be renominated as their male counterparts. Moreover, it is proved that once female mayors are proposed and elected, their re-election is as probable as that of their male counterparts. Black and Erickson (2003) find that women might even have a slight advantage over their male colleagues at renomination that was somewhat confirmed in the 2020 elections.

Table 4.

Male and female incumbents and their success rate in being re-elected.

Given the data, in Romania, the incumbent advantage is confirmed by the female incumbents as well (Figure 2). Moreover, some of them succeeded, as did their male counterparts, in spending a long time in office, as out of the 1075 administrative units that had re-elected the same mayor for four consecutive terms, 1037 were males and 38 females.

Figure 2.

The success rate (%) of male and female incumbents for 2012, 2016, and 2020 elections. Source: Processed by the authors using (BEC n.d.; ROAEP n.d.), Rezultate Vot data.

5. Conclusions and Discussions

The present research makes an in-depth analysis of the re-election of mayors in Romania, given that this topic is not covered in the specialized literature. Romania can be considered a special case with a history of about 50 years of communism (1947–1989), a period leaving traces still visible at the level of society even today.

After analyzing the electoral data for three elections in 3186 administrative units in Romania, an overwhelming domination of male candidates and mayors over their female counterparts was observed. For all the studied elections (2012, 2016, and 2020), the percentage of male candidates exceeded 90% as follows: 93.1% in 2012, 91.59% in 2016, and 90.27% in 2020. As mayors, only 1 out of 20 is a woman, which is very few in comparison to the European level. For instance, in Slovakia, 1 out of 10 mayors was a woman (Sloboda 2014).

The nomination of female candidates by a party does not necessarily ensure the election of that candidate, so the phenomenon of the election of women to the position of mayor is difficult to control. Only an increase in the number of female candidates could ultimately lead to their election. The problem remains the will of the parties to nominate as many female candidates as possible. Obviously, female candidates must also be more visible in terms of imposing themselves as candidates. Women’s organizations should be more vocal and constitute credible alternatives to male candidates. It depends not only on the availability of the parties but also on the availability of women to represent themselves as candidates. Although it seems a bit forced, the political strategy of imposing a minimum threshold of women’s presence might have effects in the first phase in the context of a situation in which women seem to more and more frequently assume a different role in society than the traditional one. These mutations at the socio-economic level for women can lead to their greater political involvement and a rebalancing of the political scene, currently dominated categorically by men.

However, the success of these efforts also depends significantly on the behavior of the electorate, which still maintains certain patriarchal mentalities regarding female politicians. In other words, it is not enough for the parties to have the will to impose as many women as possible on the political chessboard, but the electorate must also transform and perceive the woman politician through a modern point of view in which she assumes responsibilities at the political level as well as at the economic level, overcoming the conservative framework specific to the 19th century and the first part of the 20th century.

Moreover, this under-representation of female mayors leaves little room for improvement, as the degree of re-election of (predominantly male) incumbents is higher than 70% for all the studied elections and with no limitation of terms mayors can stay in office until retirement. In a system in which incumbency is so powerful, it is difficult to increase minority representation (McGregor et al. 2017). The incumbency effect in the Romanian administrative units reaches the level Sloboda and Kukovic and Lazauskienė described in Slovakia and Lithuania. Also, an important role within the high success rate of incumbents may be the first-past-the-post system, which encourages re-election. Hence, further research on the topic of the previous elections (1996, 2000, 2004, 2008), when a two-round system was used, is required in order to understand the extent to which first-past-the-post changed or did not change the patterns.

Thus, the present study succeeded in bringing arguments for an affirmative answer to the question: Can the incumbency advantage for the male legislators become a disadvantage for their female counterparts, while also strengthening previous findings that proved that high incumbency affects women’s inclusion in politics (De Paola et al. 2010; Shair-Rosenfield and Hinojosa 2014; Luhiste 2015).

These findings succeeded in providing an overview of the Romanian situation regarding a subject that has not been studied previously in this country. It will fill the gap and contribute, together with studies from Slovakia, Slovenia, Lithuania, and Portugal, to a better understanding of the European context.

Important events such as Romania’s accession to the EU (2007) have had a significant impact on the phenomenon of local elections. In particular, the infusion of EU-financed projects was an important boost in this regard for those who knew how to attract European projects. Although it was not the subject of our analysis in this article, the political affiliation of the mayors played an important role as well. The phenomenon of political migration towards the ruling party (or parties) is so prevalent in Romania that it requires a separate approach.

Even if there are major differences regarding the descriptive representation between the two genders numerically, in what concerns the degree of re-election of mayors, there were not observed significant differences. This allows us to draw the conclusion that gender is not the decisive factor in the re-election of mayors. Instead, other factors play an important role such as the advantage of being in office, making decisions as mayor to appeal to the electorate for re-election, ensuring appropriate visibility compared to other potential candidates, and forming profitable alliances.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.-D.F. and C.I.; methodology, A.-D.F. and C.I.; software, C.I.; validation, C.I.; formal analysis, A.-D.F. and C. Iinvestigation, A.-D.F. and C.I. resources, A.-D.F. and C.I.; data curation, A.-D.F. and C.I.; writing—original draft preparation, A.-D.F. writing—review and editing, C.I.; visualization, A.-D.F. and C.I.; supervision, C.I.; funding acquisition, C.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Department of Geography, Faculty of Geography, and Geology, “Alexandru Ioan Cuza” University of Iasi, Romania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets from this study can be accessed upon reasonable request from one of the first two authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | In 2014, the Democrat Liberal Party merged with the National Liberal Party to form the entity known as the National Liberal Party. |

| 2 | There is a limitation, as the research is conducted only for the 2008–2020 elections and there is the possibility that the incumbents spent other years in office before 2008. |

References

- 7 Est. 2015. Sorin Lazăr se ascunde după fusta nevestei. De ce a votat senatorul din Strunga împotriva arestării lui Dan Șova. 7Est. April 2. Available online: https://www.7est.ro/2015/04/sorin-lazar-se-ascunde-dupa-fusta-nevestei-de-ce-a-votat-senatorul-din-strunga-impotriva-arestarii-lui-dan-sova/ (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Adevărul. 2011. Pe urmele tatălui: Noul primar din Cernăteşti este chiar fiul fostului edil, decedat. Adevărul. February 21. Available online: https://adevarul.ro/stiri-locale/buzau/pe-urmele-tatalui-noul-primar-din-cernatesti-este-904969.html (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Adevărul. 2016. Dinastie la primărie. Într-o comună din Galaţi, soţia şi-a succedat soţul ca primar, iar acum vrea să lase postul cumnatului. Adevărul. January 25. Available online: https://adevarul.ro/stiri-locale/galati/dinastie-la-primarie-intr-o-comuna-din-galati-1683228.html (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Alberti, Carla, Diego Diaz-Rioseco, and Giancarlo Visconti. 2021. Gendered bureaucracies: Women mayors and the size and composition of local governments. Governance 35: 757–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alford, John, and David W. Brady. 1988. Partisan and Incumbent Advantage in U.S. House Elections, 1846–1986. Houston: Center for the Study of Institution and Values, Rice University. [Google Scholar]

- Autoritatea Electorala Permanenta [Permanent Electoral Authority]. ROAEP. n.d. Available online: http://www.roaep.ro/ (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Băluţă, Ionela. 2010. Le parlement roumain à l’épreuve du genre: Les femmes politiques dans la législature 2004–2008. Studia Politica: Romanian Political Science Review 10: 123–51. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-446742 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Băluţă, Ionela. 2012. Femeile în spațiul politic din România postcomunistă: De la “jocul” politic la construcția socială. Annals of the University of Bucharest/Political Science Series 14: 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Băluţă, Ionela. 2013. Reprezentarea politică a femeilor: Alegerile parlamentare din 2012. Sfera Politicii 174: 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Băluţă, Ionela. 2015. (Re)Constructing democracy without women. Gender and politics in post-communist Romania. Clio 41: 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Băluță, Ionela, and Claudiu Tufiș. 2021. Reprezentarea politică a femeilor în România, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Available online: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/bukarest/18818.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Băluță, Oana. 2015. Women, Mobilization and Political Representation (editorial). Journal of Gender and Feminist Studies 5: 3–7. Available online: http://www.analize-journal.ro/library/files/5_1.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Băluță, Oana. 2017. Alegerile locale și reprezentarea politică parlamentară. Trambulină pentru bărbați, obstacol pentru femei? Revista Sfera Politicii 25: 193–94. Available online: http://www.sferapoliticii.ro/sfera/193-194/art02-Baluta.php (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Biroul Electoral Central (BEC) [Central Electoral Commission]. n.d. Available online: https://www.bec.ro (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Black, Jerome H., and Lynda Erickson. 2003. Women candidates and voter bias: Do women politicians need to be better? Electoral Studies 22: 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boța, Dragoş. 2013. Soţia mafiotului pedelist Omer Radovancovici, candidatul USL pentru funcţia de primar lăsată liberă de soțul ajuns în pușcărie’. Pressalert. May 15. Available online: https://www.pressalert.ro/2013/05/sotia-mafiotului-pedelist-omer-radovancovici-candidatul-usl-pentru-functia-de-primar-lasata-libera-de-sotul-ajuns-in-puscarie/ (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Britton, Hannah E. 2008. South Africa: Challenging traditional thinking on electoral systems. In Women and Legislative Representation. Edited by Manon Tremblay. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 117–28. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Daniel Mark. 2009. A regression discontinuity design analysis of the incumbency advantage and tenure in the U.S. House. Electoral Studies 28: 123–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardenas Acosta, Georgina. 2019. Women mayors in Mexico 2017, an overview. La Ventana 6: 9–44. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Susan J., and Kira Sanbonmatsu. 2013. Entering the mayor’s office: Women’s decisions to run for municipal positions. In Women and Executive Office: Pathways and Performance. Edited by Melody Rose. Boulder: Lynne Rienner, pp. 115–36. [Google Scholar]

- Childs, Sarah, and Mona Lena Krook. 2008. Critical Mass Theory and Women’s Political Representation. Political Studies 56: 725–36. [Google Scholar]

- Cordoneanu, Felicia. 2012. Condiţia socială a femeii în ortodoxia contemporană românească. Iasi: Editura Lumen. ISBN 9731663142, 9789731663142. [Google Scholar]

- Cosma, Ghizela. 2002. Femeile şi politica în România: Evoluţia dreptului de vot în perioada interbelică [Women and Politics in Romania: The Evolution of the Right to Vote in the Period between the Wars]. Cluj-Napoca: Presa Universitară Clujeană. [Google Scholar]

- Coviello, Decio, and Stefano Gagliarducci. 2017. Tenure in Office and Public Procurement. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 9: 59–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyż, Anna. 2009. Samorząd terytorialny w państwach Europy Środkowej i Wschodniej. Studia Politicae Universitatis Silesiensis 7: 134–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dalle Nogare, Chiara, and Björn Kauder. 2017. Term limits for mayors and intergovernmental grants: Evidence from Italian cities. Regional Science and Urban Economics 64: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Benedetto, Marco Alberto, and Maria De Paola. 2019. Term limit extension and electoral participation. Evidence from a diff-in-discontinuities design at the local level in Italy. European Journal of Political Economy 59: 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Magalhaes, Leandro. 2015. Incumbency Effects in a Comparative Perspective: Evidence from Brazilian Mayoral Elections. Political Analysis 23: 113–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paola, Maria, Vincenzo Scoppa, and Rosetta Lombardo. 2010. Can gender quotas break down negative stereotypes? Evidence from changes in electoral rules. Journal of Public Economics 94: 344–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Departamentul Social Mediafax. 2013. Fostul primar al comunei băcăuane Sărata, găsit incompatibil de către ANI. Mediafax. April 4 (mediafax.ro). Available online: https://www.mediafax.ro/social/fostul-primar-al-comunei-bacauane-sarata-gasit-incompatibil-de-catre-ani-10711538 (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Erikson, Robert S. 1971. The advantage of incumbency in congressional elections. Polity 3: 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedor, Andreea-Daniela, and Corneliu Iațu. 2022. Women’s Participation in the Local Government as Voters, Candidates and Mayors in the North East Region of Romania. Open Journal of Political Science 12: 108–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedor, Andreea Daniela, Corneliu Iațu, and Marinela Istrate. 2019. The Need of Local Identity in Politics. The Case of Women Mayors in the North-East Region of Romania. Territorial Identity and Development 4: 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedor, Andreea Daniela, Marinela Istrate, and Corneliu Iațu. 2021. Equal Opportunities in Romanian Politics Work in Progress. A Chronological and Spatial Analysis of Women’s Participation in Political Life. In International Scientific Conference GEOBALCANICA 2021. Skopje: Geobalcanica Society, pp. 237–44. [Google Scholar]

- Felseghi, Bianca. 2016. Dinastie la primărie. PressOne, July 20. Dinastia Lazăr, o familie “cu tradiţie” la o primărie de comună (antena3.ro). Available online: https://www.antena3.ro/actualitate/locale/dinastia-lazar-o-familie-cu-traditie-la-o-primarie-de-comuna-368866.html (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Ferreira, Fernando, and Joseph Gyourko. 2014. Does gender matter for political leadership? The case of U.S. mayors. Journal of Public Economics 112: 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, Richard L., and Zoe M. Oxley. 2003. Gender Stereotyping in State Executive Elections: Candidate Selection and Success. Journal of Politics 65: 833–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freier, Ronny. 2015. The mayor’s advantage: Causal evidence on incumbency effects in German mayoral elections. European Journal of Political Economy 40: 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, Michael, and Michael Marsh. 1988. Candidate Selection in Comparative Perspective: The Secret Garden of Politics. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Garand, James C., and Donald A. Gross. 1984. Change in the Vote Margins for Congressional Candidates: A Specification of the Historical Trends. American Political Science Review 78: 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gash, Tom, and Sam Sims, eds. 2012. What Can Elected Mayors Do for Our Cities? London: Institute for Government. Available online: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/publication_mayors_and_cities_signed_off.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Gârboni, Emanuela Simona. 2014. Women in Politics during the Romanian Transition. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences 163: 247–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gelman, Andrew, and Gary King. 1990. Estimating Incumbency Advantage without Bias. American Journal of Political Science 34: 1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghebrea, Georgeta. 2015. Contextul de acţiune a egalităţii de gen înainte de 1989 în Statutul femeii în România comunistă. Edited by Alina Hurubean. Iaşi: Institutul European Iaşi. [Google Scholar]

- Ghebrea, Georgeta, and Marina Elena Tătărâm. 2005. O sister where art thou?: Women’s under-representation in Romanian politics. Studia Politica: Romanian Political Science Review 5: 49–88. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-56258-3 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Górecki, Maciej A., and Adam Gendźwiłł. 2020. Polity size and voter turnout revisited: Micro-level evidence from 14 countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Local Government Studies 47: 31–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambleton, Robin, and David Sweeting. 2014. Innovation in urban political leadership. Reflections on the introduction of a directly-elected mayor in Bristol, UK. Public Money and Management 34: 315–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambleton, Robin. 2013. Elected mayors: An international rising tide? Policy & Politics 41: 125–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hambleton, Robin, David Sweeting, and Thom Oliver. 2022. Place, power and leadership: Insights from mayoral governance and leadership innovation in Bristol, UK. Leadership 18: 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, Mirya R. 2017. Women in Local Government. State and Local Government Review 49: 285–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmsten, Stephanie S., Robert G. Moser, and Mary C. Slosar. 2009. Do Ethnic Parties Exclude Women? Comparative Political Studies 43: 1179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurubean, Alina. 2015. Statutul femeii în România comunistă. Politici publice şi viaţă privată. Iași: Editura Institutul European. [Google Scholar]

- Iancu, Alexandra. 2021. Increasing women’s political representation in post-communism: Party nudges and financial corrections in Romania. East European Politics 37: 598–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieș, Alexandru. 1998. Comportamentul electoral al minorităților din Transilvania, Banat, Crișana și Maramureș la alegerile de primari din 1992 și 1996. Studiu geografic. (Electoral behavoiur of minoritiesn from Crișana-Maramureș at local election (mayors) in 1992 and 1996. Geographical Studies). Revue Roumaine de Géographie 42. [Google Scholar]

- Institutul National de Statistica (INS) [National Institute of Statistics]. n.d. Available online: http://www.insse.ro/ (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Ionescu, Ramona. 2017. Primarul Norocel Ciubotaru a preluat ștafeta de la tatăl său. Desteptarea. June 22. Available online: https://www.desteptarea.ro/primarul-norocel-ciubotaru-a-preluat-stafeta-de-la-tatal-sau/ (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Jinga, Luciana-Marioara. 2015. Gen si reprezentare in Romania comunista: 1944–1989. Iași: Editura Polirom. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson-Myers, Tracy-Ann. 2016. The Impact of Electoral Systems on Women’s Political Representation. Springer Briefs in Political Science. Cham: Springer, pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurnalul De Arges. 2021. Şi-a pierdut mandatul şi nu scapă nici de insistenţa părinţilor. Jurnalul de Argeș. September 10. Available online: https://jurnaluldearges.ro/si-a-pierdut-mandatul-si-nu-scapa-nici-de-insistenta-parintilor-primarul-de-la-berevoesti-ajunge-din-nou-in-instanta-pentru-un-imprumut-144577/ (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Karnig, Albert K., and B. Oliver Walter. 1981. Joint Electoral Fate of Local Incumbents. The Journal of Politics 43: 889–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Jonathan N., and Gary King. 1999. A Statistical Model for Multiparty Electoral Data. American Political Science Review 93: 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, Chad, and Marie Rekkas. 2012. Incumbency Advantage in the Canadian Parliament. Canadian Journal of Economics 45: 1560–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizenko, Nadieszda. 2013. Feminized Patriarchy? Orthodoxy and Gender in Post-Soviet Russia. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 38: 595–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjaer, Ulrik, Kelly Dittmar, and Susan J. Carroll. 2018. Council Size Matters: Filling Blanks in Women’s Municipal Representation in New Jersey. State and Local Government Review 50: 215–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klašnja, Marko. 2015. Corruption and the Incumbency Disadvantage: Theory and Evidence. The Journal of Politics 77: 928–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukovič, Simona, and Aistė Lazauskienė. 2018. Pre-mayoral Career and Incumbency of Local Leaders in Post-Communist Countries: Evidence from Lithuania and Slovenia. Political Preferences 18: 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kukovič, Simona, and Miro Haček. 2013. The Re-Election of Mayors in the Slovenian Local Self-Government. Lex Localis 11: 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, David S. 2008. Randomized Experiments from Non-Random Selection in U.S. House Elections. Journal of Econometrics 142: 675–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoni, Eduardo, Carlos Pereira, and Lucio Renno. 2004. Political Survival Strategies: Political Career Decisions in the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies. Journal of Latin American Studies 36: 109–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhiste, Maarja. 2015. Party gatekeepers’ support for viable female candidacy in PR-list systems. Politics & Gender 11: 89–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukáčová, Jana, and Lenka Maličká. 2023. Women mayors in the Slovak Republic in the last two decades: The municipalities size category perspective. Geografický Časopis 75: 177–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, Mircea. 2020. În comuna Mihai Eminescu, soții Gireadă fac din nou rocada la primărie. Verginel Gireadă, penal PNL. Newseek. August 18. Available online: https://newsweek.ro/politica/in-comuna-mihai-eminescu-sotii-gireada-fac-din-nou-rocada-la-primarie-verginel-gireada-penal-pnl (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Marschall, Melissa J. 2014. A descriptive analysis of female mayors: The US and Texas in comparative perspective. In Local Politics and Mayoral Elections in 21st Century America: The Keys to City Hall. Edited by Sean D. Foreman and Marcia L. Godwin. New York: Routledge, pp. 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, Danielle Joesten, and Meredith Conroy. 2024. Female Candidates’ Incumbency and Quality (Dis)Advantage in Local Elections. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 45: 335–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskarinec, Pavel, Daniel Klimovsky, and Stanislava Danisova. 2018. The representation of women in the position of mayor in the Czech Republic and Slovakia in 2006–2014: A comparative analysis of the factors of success. Czech Sociological Review 54: 529–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, Elena, Corneliu Iaţu, and Constantin Vert. 2010. Romanian Woman Involvement in Governance after 1990. Geographica Pannonica 14: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, R. Michael, Aaron Moore, Samantha Jackson, Karen Bird, and Laura B. Stephenson. 2017. Why So Few Women and Minorities in Local Politics?: Incumbency and Affinity Voting in Low Information Elections. Representation 53: 135–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondak, Jeffery J. 1995. Competence, Integrity, and the Electoral Success of Congressional Incumbents. The Journal of Politics 57: 1043–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, Mauricio, and Fabián Belmar. 2022. Clientelism Turnout and Incumbents’ Performance in Chilean Local Government Elections. Social Sciences 11: 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, Manoel Gehrke Ryff. 2012. Are Incumbents Advantaged? Evidences from Brazilian. Municipalities Using a Quasi-Experimental Approach. Bocconi University—European Commission (JRC): Available online: https://www.exeter.ac.uk/media/universityofexeter/elecdem/pdfs/florence/Moreira_Are_Incumbents_Advantaged.pdf (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Neaga, Diana Elena. 2012. “Poor” Romanian Women—Between the policy (politics) of IFM and local government. European Journal of Science and Theology 8: 291–303. [Google Scholar]

- Neaga, Diana Elena. 2014. A top-down image of political participation—Interviews with “succeful” political women. European Journal of Science and Theology 10. [Google Scholar]

- Niemi, Richard, and John Fuh-sheng Hsieh. 2002. Counting Candidates: An Alternative to the Effective N: With an Application to the M + 1 Rule in Japan. Party Politics 8: 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitkin, Hanna Fenichel. 1967. The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Podolnjak, Robert, and Đorđe Gardašević. 2013. Directly Elected Mayors and the Problem of Cohabitation: The Case of the Croatian Capital Zagreb. Elections and Democracy 20: 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajca, Lucyna. 2021. The Position of Mayor Within Local Authority Relations in Hungary and Poland in a Comparative. Środkowoeuropejskie Studia Polityczne 1: 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recensământul populației din. 2021. Rezultate definitive: Caracteristici demografice—Recensamantul Populatiei si Locuintelor. Available online: https://www.recensamantromania.ro/ (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Saltzstein, Grace Hall. 1986. Female Mayors and Women in Municipal Jobs. American Journal of Political Science 30: 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanbonmatsu, Kira. 2002. Political parties and the recruitment of women to state legislatures. Journal of Politics 64: 791–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwindt-Bayer, Leslie. 2005. The incumbency disadvantage and women’s election to legislative office. Electoral Studies 24: 227–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shair-Rosenfield, Sarah, and Magda Hinojosa. 2014. Does Female Incumbency Reduce Gender Bias in Elections? Evidence from Chile. Political Research Quarterly 67: 837–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, Amrit Kumar, and Indira Achary Mishra. 2024. Effect of the electoral system on women’s representation: Evidence from national elections of Nepal. Humanities and Social Sciences Letters, Conscientia Beam 12: 101–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloboda, Matúš. 2014. Women’s participation and Incumbency Advantage in Slovak Cities: The Case Study of Mayoral elections in Slovakia. Socialiniai tyrimai/Social Research 36: 101–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Adrienne, Beth Reingold, and Michael Leo Owens. 2012. The political determinants of women’s descriptive representation in cities. Political Research Quarterly 65: 315–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundström, Aksel, and Lena Wängnerud. 2016. Corruption as an obstacle to women’s political representation: Evidence from local councils in 18 European countries. Party Politics 22: 354–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tybuchowska-Hartlińska, Karolina. 2019. Leaders, Managers or Administrators—Mayors in Central and Eastern European Countries. Political Sciences 58: 155–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titiunik, Rocio. 2009. Incumbency Advantage in Brazil: Evidence from Municipal Mayor Elections. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Tomita, Marius. 2012. Olt: Deputatul Nicolae Stan candidează ca independent pentru Camera Deputaţilor. SemnalEu. November 1. Available online: https://semnal.eu/olt-deputatul-nicolae-stan-candideaza-ca-independent-pentru-camera-deputatilor/ (accessed on 28 March 2024).

- Van der Kolk, Henk, Colin Rallings, and Michael Thrasher. 2004. Electing Mayors: A Comparison of Different Electoral Procedures. Local Government Studies 30: 589–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Várnagy, Réka, and Gabriella Ilonszki. 2012. Üvegplafonok. Pártok Lent És Fent. Politikatudományi Szemle 21: 7–25. [Google Scholar]

- Veiga, Francisco José, and Linda Gonçalves Veiga. 2018. Term limits and voter turnout. Electoral Studies 53: 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).