Abstract

The Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE) is a unique economic model that addresses contemporary community problems by democratising the economy through activities that promote sustainability, solidarity, and collective prosperity. Research on the SSE has increased in recent years, showing its potential as an alternative to dominant economic schemes. This article aims to analyse how the SSE can contribute to sustainability in rural sector associations in Ecuador through the Participatory Action Research (PAR) method. This method empowers various stakeholders, including the community, associations, and the university, to be actively involved in designing, developing, and implementing solutions to alleviate their problems. The results show that in the context of a developing country, this active participation, interaction, and commitment can identify the various problems that the rural sector and its associations are experiencing. This situation allows for possible joint action solutions, involving people who usually do not have decision-making power or are vulnerable, by diagnosing their socio-economic conditions and establishing a training programme where knowledge production is democratic, thus combining theoretical and practical elements according to the needs detected.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the social and solidarity economy (SSE) has received increasing interest in industrialised and developing countries, where policymakers, academics, and interested professionals have paid attention to its development (Lee 2020; Wallimann 2014). The SSE is a community-based alternative response that addresses contemporary problems related to economic, social, and environmental aspects (Esteves et al. 2021; Tello-Rozas 2016), as well as society’s dissatisfaction with its needs caused by the forces of the market and the public sector (Dash 2016). Therefore, the SSE facilitates a fair and collective allocation of resources, offering an alternative to predominant market-centred economic ideologies (Dash 2016; Villalba-Eguiluz et al. 2020).

The SSE is an active economic paradigm, a social movement, and an alternative to market capitalism (Arampatzi 2020; Lemaître and Helmsing 2012). This paradigm takes root in society by promoting sustainable development based on solidarity, trust, and cooperation among citizens and involving them in economic activities under a democratic scheme (Dash 2016; Sahakian 2016). The SSE fosters governance, which enables the creation of equity and shared wealth (Bell et al. 2018), while, at the individual level, it enables economic reinvention based on values related to solidarity, reciprocity, and sustainability (Dash 2016). In other words, the SSE is based on collective and associative prosperity and leads to an organisation seeking equitable wealth distribution.

The SSE, being a human-centred socio-economic activity, eludes the dominant forms of the market and the state (Sahakian 2016), so its development and applications can play an essential role in establishing transformative policies and models of development (Chaves-Avila and Gallego-Bono 2020), reinstituting urban commons (Arampatzi 2020), job creation and poverty alleviation (Lee 2020), as well as compliance with the sustainable development goals promoted by the United Nations 2030 (Saguier and Brent 2017; Villalba-Eguiluz et al. 2020).

In recent decades, the SSE has experienced significant development in Latin America, mainly in South America, where its societies have sought political and economic changes in response to the prevailing negative socio-economic externalities (Tello-Rozas 2016; Villalba-Eguiluz et al. 2020). The SSE in this region is presented as a social movement composed of organised networks that collaborate with the state in the formulation of public policies (Esteves 2014), causing production and consumption activities to be solidarity-based and seeking to meet the needs of the community (Saguier and Brent 2017). The SSE has been adapted according to the particularities of each country, focusing on urban and rural contexts, where people with low incomes are considered primary stakeholders in the development of economic activities (Sahakian 2016; Villalba-Eguiluz et al. 2020). In this context, Ecuador and Bolivia are trying to recover the cultural identity associated with the rural cycle work of the land. Argentina established close relationships between the state and the communities, Mexico, and Chile, in local development under the self-management system. Peru operates a system of self-managed cooperative industries, while Nicaragua has an interventionist State with ambitious public policies that oppose the government’s capacity to carry them out (Castelao Caruana and Srnec 2013; Grugel and Riggirozzi 2012; Utting 2017; Veltmeyer 2018). The Social Economy is an essential sector in some countries and builds social relations among its members based on principles of reciprocity and cooperation (Sahakian 2016). However, rural sectors are the most vulnerable and require a commitment among their stakeholders to achieve sustainable development, which is elusive.

This research aims to analyse how the SSE can contribute to sustainability in associations in Ecuador’s rural sector by considering the Participatory Action Research (PAR) method for empowering its members and community. Based on the previous discussion, we address the following research questions:

RQ1: Can the SSE contribute to the sustainable development of the rural sector?

RQ2: Can Participatory Action Research be used in associations based on SSE?

RQ3: Is it possible to establish interactions between the community, associations, and universities to promote the sustainable development of the rural sector?

The article consists of six main sections. First, the introduction shows how the social economy provides for the sustainable development of a community based on partnership and collective prosperity; second, a brief literature review of its effects in Latin America and Ecuador; third, we consider participatory action research (PAR) as a methodological framework for studying the social economy and its impact on rural associations; fourth, the results obtained with participatory action research (PAR) are presented; third, it considers PAR as a methodological framework for the study of the social economy and its effects on rural associations; fourth, the results obtained with the participation of the partners, the community and the university; fifth, the discussion of the findings obtained; and finally, the sixth part addresses the conclusions and limitations of the study.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE)

The Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE) is a term widely used to describe types of economic activity that prioritise social and often environmental objectives, which require the cooperative action of producers, employees, customers, and citizens (Bergeron et al. 2015; Borzaga et al. 2019). Researchers consider the SSE oriented towards satisfying non-covered needs, where the common interest prevails over the collective one (Arampatzi 2020).

The SSE adds value to the community through its economic and social benefits and the benefits associated with a change in its organisations. These benefits are associated with increased community participation in civic affairs, decision-making, access to education, sources of employment and higher incomes, reduced poverty, social assistance, and insecurity (Arampatzi 2020; Bell et al. 2018; Matei and Dorobantu 2015).

This economy features a wide range of socially focused organisations such as cooperatives, mutual aids, and voluntary associations (Ku and Kan 2020), as well as various self-help groups that organise themselves to produce goods and services, are independent of government, and pursue goals and standards that prioritise social cohesion, collaboration, and solidarity (Fonteneau et al. 2011; Utting et al. 2014). In the SSE, organisations are hybrid in the sense that they have commercial activities like a business and, at the same time, promote social objectives. That is, they seek to ensure a balance between profit generation and service to members and society, which leads to it being seen as a third sector that complements the public and private sectors (Ferguson 2018).

These social economy organisations share values, which are found in their organisational structure and relate to the following: (1) The aim of the enterprise is to serve its members or the community rather than solely seeking financial gain; (2) The independence of the organisation from the state; (3) The preference for people and labour over the capital in the distribution of income and profit; (4) Participation, empowerment, individual and community responsibility are the pillars of their functioning (Dash 2016; Gleerup et al. 2019; Matei and Dorobantu 2015; Neamtan 2002).

To reiterate, the SSE is an autonomous entity, and its legitimacy is derived from its role in addressing the economic and social development issues of its members. These members are not mere spectators but active participants in its productive and management activities (Bergeron et al. 2015; Matei and Dorobantu 2015). It is important to reemphasise that the SSE is distinct from populism. Populism, in contrast, is a phenomenon characterised by the mass mobilisation of people and resources towards specific political objectives (Coraggio 2015). This is diametrically opposed to the community and participation interests championed by the SSE.

The SSE, for its versatility, is conceived as part of the economic character initiatives that arise from the unsustainable practices of socio-economic development, such as the degradation of the ecosystems, poverty, room, inequality, and climate change (Harris et al. 2023; Langergaard and Rendtorff 2022). The United Nations Organization considers these initiatives “New Economics for Sustainable Development” as a set of tools that allow the advancement of the very dimensions of the ODS. These initiatives correspond to, in no specific order, the Social and Solidarity Economy, Blue Economy, Care Economy, Creative Economy, Attention Economy, Circular Economy, Green Economy and Frugal Innovation Economy (Yi et al. 2023).

The ESS maintains a relationship with one of its initiatives: (i) Blue Economy—the small fish scale guards the relationship between the SSE organisations—is part of its food and life system (García-Lorenzo et al. 2024). (ii) Care Economy, also known as the purple economy, includes social services and assistance that enable the SSE benefits to provide favorable conditions against poor remuneration conditions (Wendt 2022). (iii) Creative Economy, called the dark economy, is based on economic, cultural and social aspects that combine with technology, awareness, and tourist objects, which allows the economic development of a community, which, in turn, allows access to the SSE (Henderson et al. 2023; Rodríguez-Insuasti et al. 2022). (iv) Attention Economy, or economics of information, is considered as an emphasis on human attention as a good asset in the management of information, as the handling and calibration of personal information, applicable to the principles of SSE, and as the governance of digital technologies (Line Carpentier 2023; Malta and Baptista 2013). (v) Circular Economy, in which the principles of the SSE foment the characteristics of the trading model based on this economy, and in which the conscious participation and cooperation of the consumer are fomented as if to maximise the social and environmental objects before the economy is decided. The capacities related to recycling, recovery and Repair activities (Harris et al. 2023; Villalba-Eguiluz et al. 2023). (vi) Green Economy, in which the organisation of the SSE recognises the use of goods and services that are sensitive to the environment in addition to productive processes (Quiroz-Niño and Murga-Menoyo 2017); (vii) Frugal Innovation Economy, in which it is more compatible with less to internalise social and environmental costs in the SSE (Yi et al. 2023).

2.2. The SSE in Latin America and Ecuador

In Latin America, the concept of the SSE is linked to the cooperative movement and the development paradigm called “Buen Vivir” (Spanish) or its equivalent in indigenous languages, Quechua “sumac kawsay”, shuar “pénker pujústin” or Aymara “suma qamaña” (Acosta 2017; Sahakian 2016; Veltmeyer 2018). This social economy movement appears as a direct response to the economic and political crisis of the 1990s, seeking alternatives to the neoliberal policies imposed in the region (Coraggio 2015; Larrabure et al. 2011). Its implementation is linked to pressure from workers, social groups, indigenous movements and left-wing parties, who have succeeded in getting the SSE recognised in some Latin American countries in their legislation, in the establishment of public institutions or programmes (Castelao Caruana and Srnec 2013; Veltmeyer 2018). In the case of Ecuador and Bolivia, where deep crises and revolts organised by indigenous movements and popular forces were experienced (Acosta 2017), some authors called this era the “post-neoliberal turn”, which seeks to implement economic changes and social objectives inspired by human development, as well as a reunion with its origins (Coraggio 2015; Kothari et al. 2014; Veltmeyer 2018). These changes were promoted by some governments in the region, with the conception that the social economy is beneficial and promotes social inclusion and economic development (Castelao Caruana and Srnec 2013; Larrabure et al. 2011).

In Latin America, we have several examples. Brazil has one of the most advanced economic solidarity systems in the world to drive a social reform for the livelihood of the population, inequality and solidarity, with the institution of the SSE based on agroecologías and agroforestry practices in the Amazons, as well as a public structure that includes 120 local forests and 27 estates that allow the development of action plans (Otsuki and de Castro 2020). Mexico is coordinated by the National Institute for Social Economy (INAES), contacted by 15,705 economic entities, which represent 10% of employees and 1.6% of GDP (OECD 2024). In Nicaragua, the SSE had a broad expansion due to the revolution organised by the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN), wherein in the 1980s, 25% of the agricultural lands were expropriated and handed over to more than 3000 new cooperatives, which additionally received technical and financial support for their operation (Utting 2017). These social economy organisations share values found in Colombia. The solidarity economy accounts for around 4% of GDP, the largest share of which comes from the 10,500 cooperatives registered with the Chamber of Commerce (Supersolidaria 2022). Meanwhile, Chile is one of the nations in the region with the least developed social economy sector, with around 2.4% of the formal labour force, according to The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) (CEPAL 2022).

In Ecuador, the economic system has historically been pluralistic and heterogeneous, and the existing primacy of capitalism has not been an obstacle to the development of the SSE (Sánchez 2016). In fact, since 2007, with the Constitution (the supreme norm in the country), it has been established that the country’s economic system is social and supportive in which the relationships between society, market and society are balanced (Constitución de La República Del Ecuador 2008; Article 283). In this same year, the concept of “living well” was taken up by the current government in Ecuador, which faces a process of change in its economic model (Calvo et al. 2020; Villalba-Eguiluz et al. 2020), where the basis of its growth is focused on public investment as a driving force, political and economic changes, and human development and socio-economic activities are linked to the environment (Veltmeyer 2018).

Over the last ten years, the non-financial sector has seen a 194% increase in the number of organisations, totalling 16,460. With a collective membership of 548,773, these organisations are active across 14 economic activities (refer to Table 1). Among these activities, agriculture is the most significant due to the largest number of organisations, partners, and sales volume. Overall, the estimated income for these organisations by 2022 is 1440 million USD.

Table 1.

SSE overview in Ecuador.

These organisations are regulated and controlled by the Superintendency of Popular and Solidarity Economy, a technical government regulation body with administrative and financial autonomy. Furthermore, they have a broad legal framework that allows them to carry out their economic and social activities aimed at good living without implying profit or capital accumulation (Ley Orgánica de La Economía Popular y Solidaria 2011). In the law mentioned above (articles 4 and 5), it is established that the acts carried out by these organisations do not constitute commercial or civil acts but rather acts of solidarity that must be guided by eight principles: (i) The search for good living and the common good; (ii) Priority of work over capital; (iii) fair trade and ethical consumption as responsible; (iv) Gender equality; (v) Respect for cultural identity; (vi) Self-management; (vii) Social and environmental responsibility; (viii) The equitable and supportive distribution of surpluses.

The SSE organisations in Ecuador are distributed by sectors, with the Associative sector being the most representative, with 83.32%, followed by the Cooperative sector (15.91%) and the Community sector (0.77%). These sectors are composed of rurality and poverty ranks, corresponding to the organisation’s location in Ecuador’s rural and poor populations. Table 2 reveals that all organisations operate in areas that impact the rural population, with over 38.91% having more than 50% rural inhabitants. Additionally, the Associative sector stands out as the most representative. However, 69.68% of the organisations operate in communities where 50% or more live in poverty. The data suggest that as the influence of the rural population within the SSE organisations grows, poverty levels also rise. In general, despite the aforementioned regulations and principles, SEE organisations suffer from problems related to deficiencies in financial and commercial management capabilities, productive diversification, and solidarity-based value addition to change the national productive matrix (Arguello Núñez et al. 2019).

Table 2.

SSE Rurality and Poverty ranks in Ecuador.

As mentioned above, it is of special interest to examine the rural associations of the popular and solidarity economy.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participatory Action Research (PAR)

PAR is a form of action research where co-learning is emphasised, allowing for changes in research objectives, hypotheses, and interpretations as the research develops (Sparre 2020). Therefore, they present flexible and adaptable research protocols as they change and as the research develops (Heard 2022). PAR belongs to qualitative research approaches that enable the construction of equity and social justice by involving marginalised human groups to alleviate their suffering (Dudgeon et al. 2017; Heard 2022). It involves participants meaningfully in the design, development, and evaluation of the research (Johnson and Flynn 2021), even allowing them to act as co-researchers, and their local knowledge is considered valid for the development of the study (Bellino et al. 2021). In this way, research can be connected to participants’ needs, concerns and experiences by considering community members (Anonson et al. 2022; Bradbury et al. 2019) and, in this case, the associations.

For these reasons, researchers view PAR as a social, practical, and collaborative process that identifies potential solutions and establishes cooperative actions to address social problems, improve living conditions, and even shape local practices (Fox et al. 2021; Siu and Xiao 2020). It enables the generation of knowledge, actions and even empowerment of participants by building and deepening their knowledge (Anonson et al. 2022; Bradbury and Reason 2003). Ultimately, there is an improvement in the social reality of communities, with their members being the primary beneficiaries (Maldonado-Erazo et al. 2023). Researchers have employed PAR in various studies involving the industry, vulnerable groups, or communities with university participation (Bellino et al. 2021; Sparre 2020).

3.2. Study Zone

The province of Los Ríos is located in the centre of Ecuador (South America), in the coastal region, with an estimated surface area of 7205.27 Km2. According to the National Institute of Statistics and Census—INEC, it has 899,632 inhabitants, where only 35.4% are economically active (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos 2022). Socio-economic development is related to agriculture as the primary source of income and employment (Comercio 2018). The province contributes to the country’s agricultural production with bananas (64.7%), maize (56.3%), rice (39.6%), cocoa (29.2%), passion fruit (19.6%), and African palm (16.6%) (GADP de Los Ríos 2019).

According to statistics from the Superintendence of Popular and Solidarity Economy (2024), 908 organisations are registered in the province of Los Ríos, accounting for 5.52% of the national total. Most of these organisations belong to the associative sector (811; 89.32%), and their strength is related to the agricultural sector (543; 66.95%). These associations related to the agricultural sector (see Table 3) show that their members are primarily men (66.0%) with high school education (83.0%), aged over 40 (76.47%) and have been involved in the association for more than six years (74.58%). The SSE analysis of the agricultural sector is appropriate because it allows for contrasting the various proposed relationships of a set of associations that are homogeneous in terms of the type of activity and belong to the same environment.

Table 3.

SSE members and its overview in Ecuador.

3.3. Design of the Study

In this study, the researchers and students attached to the Technical University of Quevedo and stakeholders from the associations and community played a crucial role. This study presents multiple sessions of work with the participants, which allowed for the design, development, and evaluation of the action proposal.

This university intervention in the study zone is related to multidisciplinary participation in activities to serve the community. These activities play an essential role in detecting the associations’ basic needs and their members’ needs, which require prompt solutions through the development of capabilities with the synergy of the university and the associations. The PAR enables the development and application of these mechanisms. This type of participatory research establishes phases necessary to carry out the research and is related to planning, action, reflection, and evaluation (Duijs et al. 2021). Each of these phases is important, and action and reflection allow the research to be evaluated and adjustments can be made to the process; that is, all phases interact (Kidd et al. 2018).

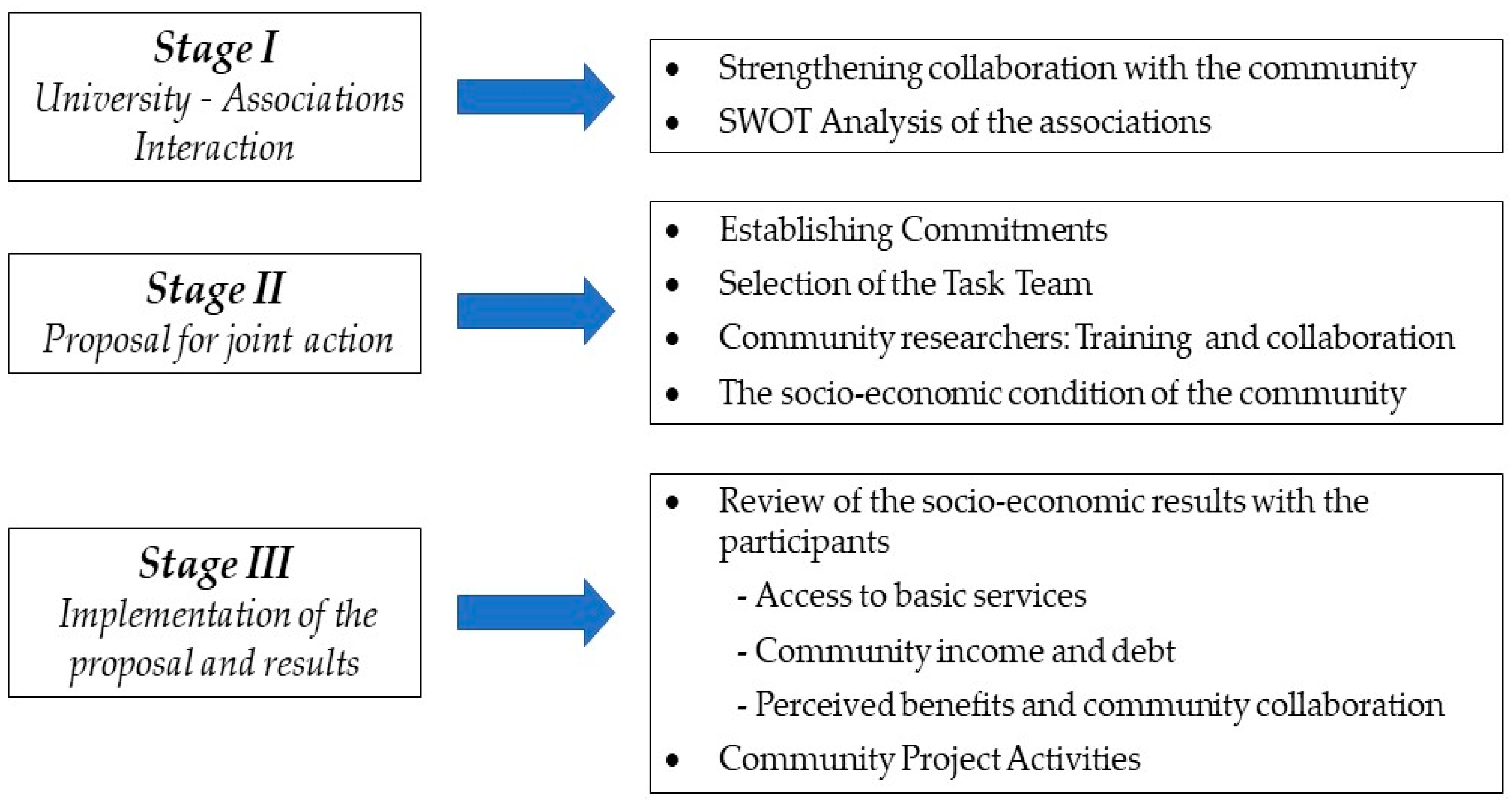

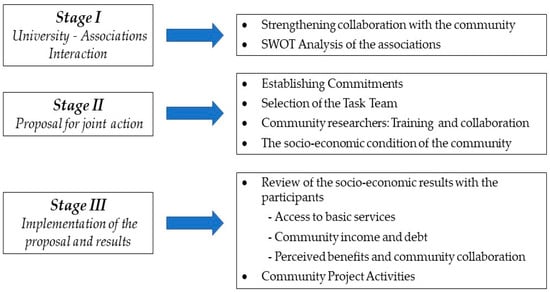

This study presents a methodology that allows a better understanding of the interaction between the community and the university, developed in three phases (see Figure 1): (i) University-Associations Interaction. (ii) Proposal for joint action. (iii) Implementation of the proposal and results obtained. The project reflects these phases, carried out between seven and 18 months.

Figure 1.

Methodological Scheme.

3.3.1. Stage I: University-Associations Interaction

In this stage, we planned, took action, and reflected on the initial activities. We defined the communities and associations that intervened, involving the university community. We established mechanisms for interaction between the university and the associations, including strengthening collaboration with the community, conducting SWOT analyses of the associations, and establishing commitments and agreements.

3.3.2. Stage II: Proposal for Joint Action

This stage focuses on the action-participation process through dialogue, mediation, and interaction between the university, associations, and communities. This action-participation process allowed the formation of working groups and the construction of diagnostic mechanisms based on the needs of the participants, with the university acting as a channel for these requirements. The stage considers several activities developed from the strategies obtained with the SWOT analysis, which allowed the action and participation of the stakeholders: (i) The establishment of commitments; (ii) The selection of the work team by the university; (iii) The formation and collaboration of a group of partners who were designated as researchers, representing the community; (iv) The design of the survey to know the social and economic situation, by collecting primary information in-situ from the members of the association. These activities generally require workshops and information sessions, allowing people not involved in decision-making (local authority) to collaborate in the proposal.

3.3.3. Stage III: Implementation of the Proposal and Results

In this last stage, once the survey and interview results had been obtained, a strategic plan for the associations was constructed to improve their operational, management, and financial capacities by training the association’s members. This construction is called “Community Project Activities” and consists of community workshops on improvements in production management, finance, and social economy.

4. Results

4.1. Stage I: University-Associations Interaction

4.1.1. Strengthening Collaboration with the Community

In the planning, the university researchers defined the communities where to intervene and the associations involved. Initially, rural communities in Ecuador, in the province of Los Ríos, were chosen due to their limited socio-economic development and the popular and solidarity economy associations that operate in them. The researchers needed an initial approach with the communities and associations to invite them to participate in a joint effort, which was capitalised by approaching their community/association leaders (representatives). This meeting allowed the research’s general objectives to be informed and discussed, as the collaboration between the university associations and the economic and social transformation this study intends to achieve using the PAR. The PAR allows participants to become meaningfully involved in the study; they actively participate in the research with the design, development and analysis of results (Johnson and Flynn 2021).

The meetings allowed access to three agricultural associations in the rural sector close to Quevedo. The Superintendence of Popular and Solidarity Economy registers the associations, serving as the governmental control body for associations in the popular and solidarity economy sector (Table 4).

Table 4.

Associations of popular and solidarity economy part of the study.

4.1.2. SWOT Analysis of the Associations

This type of analysis is regularly used as management support for strategy building due to its simplicity (Pickton and Wright 1998). SWOT allows the analysis of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats, which leads to a holistic understanding of the organisation under study (Goranczewski and Puciato 2011). In other words, this analysis provides an overview of the situation of the associations (diagnosis) and the establishment of actions (of a strategic nature) that enable desirable results to be obtained by minimising the negative aspects and maximising the positive aspects of the diagnosis obtained.

The SWOT analysis can be shown in a two-dimensional matrix (see Table 5) due to the interaction of the partnership members and the university community. As this was the first joint activity, university teachers, students and association leaders needed to act as facilitators of the process. In these meetings, the importance and purpose of the activity was explained. The members of the associations, as participants, were asked to consider the internal environment of their organisations, which allowed them to draw out strengths and weaknesses. They were also encouraged to analyse the external environment of the associations in order to identify opportunities and threats (see Table 5 and Figure 2). The participants discussed and consolidated these issues to make them representative of the associations and allow them to build the strategies.

Table 5.

SWOT Matrix of the Associations.

Figure 2.

Meetings with members of the associations to determine the SWOT matrix.

These strategies, as a result of the SWOT analysis, allow the elaboration of the proposal for work between the university and the associations based on Participatory Action Research (PAR) to obtain direct benefits for those involved, especially the members of the associations.

The SWOT analysis made it possible to propose strategies that allowed for adequate work between the associations and the university, distinguishable into four types: (i) Defensive actions, by considering a combination between the strengths (S) to reduce the threats (T) of the external environment; (ii) Building strength for a defensive strategy, by using the information weakness (W) and considering the latent threats (T); (iii) Attacking strategies, by considering the strengths (S) and the maximisation of opportunities (O); (iv) Building strength for attacking strategies considering weakness (W) of the associations and the exploitations of the opportunities (O).

These strategies served as input to establish the time-bound commitments between the parties (see Table 6).

Table 6.

PAR strategies for implementation of the project.

4.2. Stage II: Proposal for Joint Action

4.2.1. Establishment of Commitments

Establishing commitments between the university, communities, and associations is indispensable to formally integrating them into the project. The integration guarantees the creation of organisational structures that allow the implementation of activities and the achievement of relevant results for the stakeholders involved. In this context, the university established specific academic cooperation agreements that allow it to contribute to solving problems of interest, taking advantage of the resources or strengths of those involved. Mutual agreement among the participants allows for establishing specific obligations they can execute. Typically, these agreements cover long periods (such as five years in this context) and ensure permanent results for the stakeholders involved.

The three associations signed agreements with the university for the development of the activities described above under the umbrella of the project “Strengthening of Popular and Solidarity Economy Organisations as an Instrument for the economic development of Quevedo and its Area of Influence”:

- Agricultural production association “30 de junio San Pablo” known as “Aspronsanpablo”. Specific Academic Cooperation Agreement of December 2021.

- Farmers’ Association “Señor de la Salud”. Agreement UTEQ-DIRVINC-2022-0114-M of January 2022.

- Montubia Association “La llanta”. Agreement UTEQ-DIRVINC-2021-0644-M of December 2021.

4.2.2. Selection of the Working Group

The university initially defined the characteristics of the work teams for this study. These guidelines align with the requirements of the community outreach projects that the university has been promoting since 2017, involving teachers and students.

- University Staff: These are academics with interest, training and experience in issues related to community outreach. These professionals are subject to accrediting at least one research project with the community as experience and availability during the project at least 10 h per week in the case of the director and a maximum of six hours per week in the case of research staff. In this specific project, they must also have experience in social and solidarity economy, social responsibility, and local development. The authors of this study have experience in social and financial development in public institutions such as the Banco de Desarrollo del Ecuador B.P. (BDE) and Corporación Financiera Nacional (CFN), as well as in the elaboration of projects to strengthen the MSME sector, in community development, and community outreach work through academia. Three academics participated in economics degree programmes. Three academics participated in economics degree programmes and one in an agronomy degree programme.

- Students: As part of their academic training, actively participate in the project. Specifically, those in the seventh semester of their degree with experience in professional corporate internships form groups of five to seven people. Each group has a leader who reports to the project director. The leader’s selection works on their predisposition, communication skills, and capacity for teamwork. In total, 21 students from the economics degree programme were involved.

4.2.3. Community Researchers: Training and Collaboration

The project’s involvement of the three associations required the integration of their organisational structures to ensure that the planning, development and implementation of activities and outcomes are relevant to the associations and, thus, to the community (Anonson et al. 2022). Each association collaborated in identifying, selecting, and recruiting members to be part of the project (Figure 3). These researchers contributed information and ideas to the survey design and the interview, as well as their perspectives on the required training.

Figure 3.

Meetings with members of associations and the university community.

The university researchers gave the community a set of criteria to consider when selecting community researchers. This selection takes into account some of the criteria mentioned by Dudgeon et al. (2017): (a) Membership of the community and majority acceptance by the community; (b) Knowledge of the local community; (c) Communication skills; (d) Capacity to establish cooperative networks. This task is for the association leaders, one for each association.

4.2.4. The Socio-Economic Condition of the Community

In the first group sessions with the members of the three associations, relevant information was obtained and provided to the researchers on the essential aspects that require a diagnosis of the current situation with a social and economic focus.

This diagnosis intends to know the magnitude of the problem and to remedy to some degree the problems faced by the members of the associations and, thus, the community. The selected problems have been analysed to estimate their causes and to seek to optimise the capacities of the associates for the common good. To this end, questions were developed by the research team to cover the issues raised by the members of the associations.

The research questionnaire was previously reviewed by professionals related to SSE, social development, and economics, with input from representative community stakeholders. This design ensures that the respondents correctly understand the questionnaire. In this rural sector, simple language is applied in the questionnaire to obtain as much information as possible about the constructs and their dimensions.

The survey consists of four sections: (i) Access to basic services (drinking water, basic sanitation, rubbish collection); (ii) Community income and debt; (iii) Perceived benefits and community engagement. The items and scales were constructed through discussion and reflection between the researchers and members of the community and associations. The variables used are presented as a nominal scale and, in some cases, as a dichotomous scale. Between October and December 2021, we collected data. The estimated time for administering the survey was 15 min per person, allowing us to obtain respondents’ consent and inform them about the purpose of data collection and the importance of the results for the community. Regarding the representativeness of the informants, we surveyed all the associates without stratifying by gender, age, or education. We surveyed fifty-nine people, all of whom belong to the associations mentioned in this study.

4.3. Stage III: Implementation of the Proposal and Results

4.3.1. The Socio-Economic Condition of the Community

The collected data come from a survey administered to these active and legally registered association members. The study population comprises three agricultural associations registered with the Popular and Solidarity Economy Superintendence. We decided to survey the members of these associations, surveying situ. Between May and June 2021, we made up to three personal contacts with the association members. We received a total of 59 valid questionnaires during the data collection process.

- (i)

- Access to basic services

4.3.2. Water Supply in the Comunity

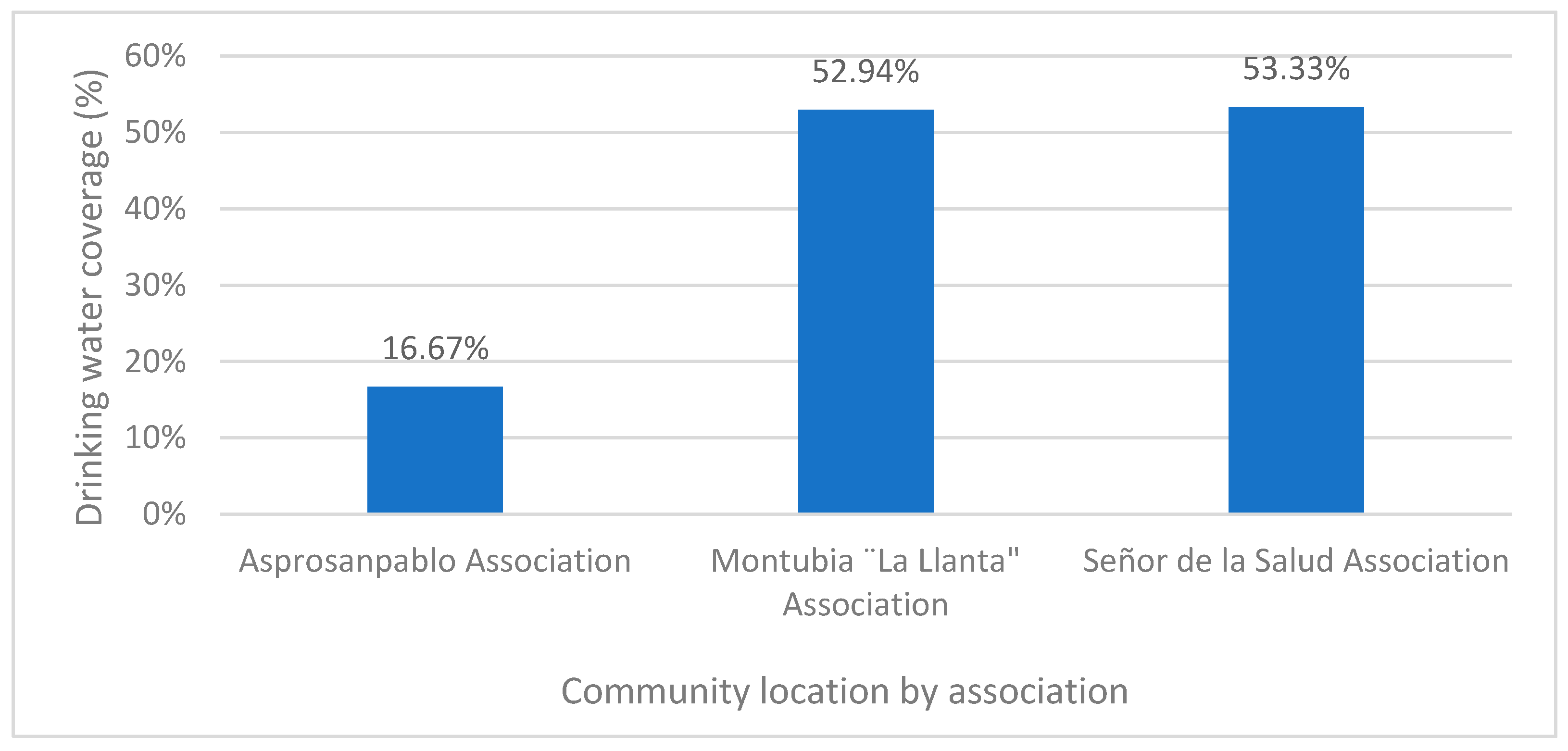

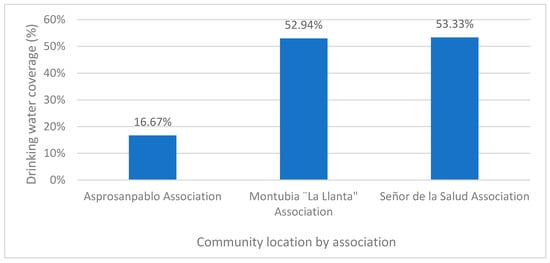

The associations in the rural sector have low drinking water coverage (see Figure 4). Their average co-coverage is 41%, with the Asprosanpablo Association (16.67%) having the lowest coverage. These amounts differ from those reported by INEC and other international organisations that monitor this resource. These figures differ from those reported by INEC and other international organisations monitoring this resource.

Figure 4.

Drinking water coverage in the influence zone of the associations.

In Ecuador, the Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) of UNICEF and WHO consider that Ecuador has met target 7C of the Millennium Development Goals on water and sanitation. Access to water resources by the population is 80.7%, with a gap between urban and rural areas of 95.5% and 74.3%, respectively (Molina et al. 2018; UNICEF 2017). These data, both from international organisations and from the survey, show that the three associations have coverage below the national average in terms of access to water.

Access to water is not easy; most members (69.49%) require additional efforts when purchasing water in distant places. The MDGs consider this situation, which defines basic water service as an improved facility located 30 min from and to the resource (UNICEF 2017). In Ecuador, basic access is when the community has access to this resource through a public network that allows direct access to the home (Molina et al. 2018).

SSE and access to water are, in many ways, complementary. The limited access and supply of water in the rural sector require associations to provide alternatives for production and consumption, which are limited to their infrastructure, knowledge for reusing the vital liquid, and even reaching places that are difficult to access (Katajamäki 2023). A key aspect is that SSE participants know their real needs, allowing them to decide on specific solutions, including circulars suitable for associations and their members (Katajamäki 2023; Zhang et al. 2021). According to the results presented (see Figure 4), most informants require access to basic water services, which shows that it is a pending task of Objective 6 of the SDGs. The objective considers the population’s access to water, which must be close to the home (accessibility), meet needs (availability) and be free of contaminants (quality) (Molina et al. 2018).

4.3.3. Community Sanitation

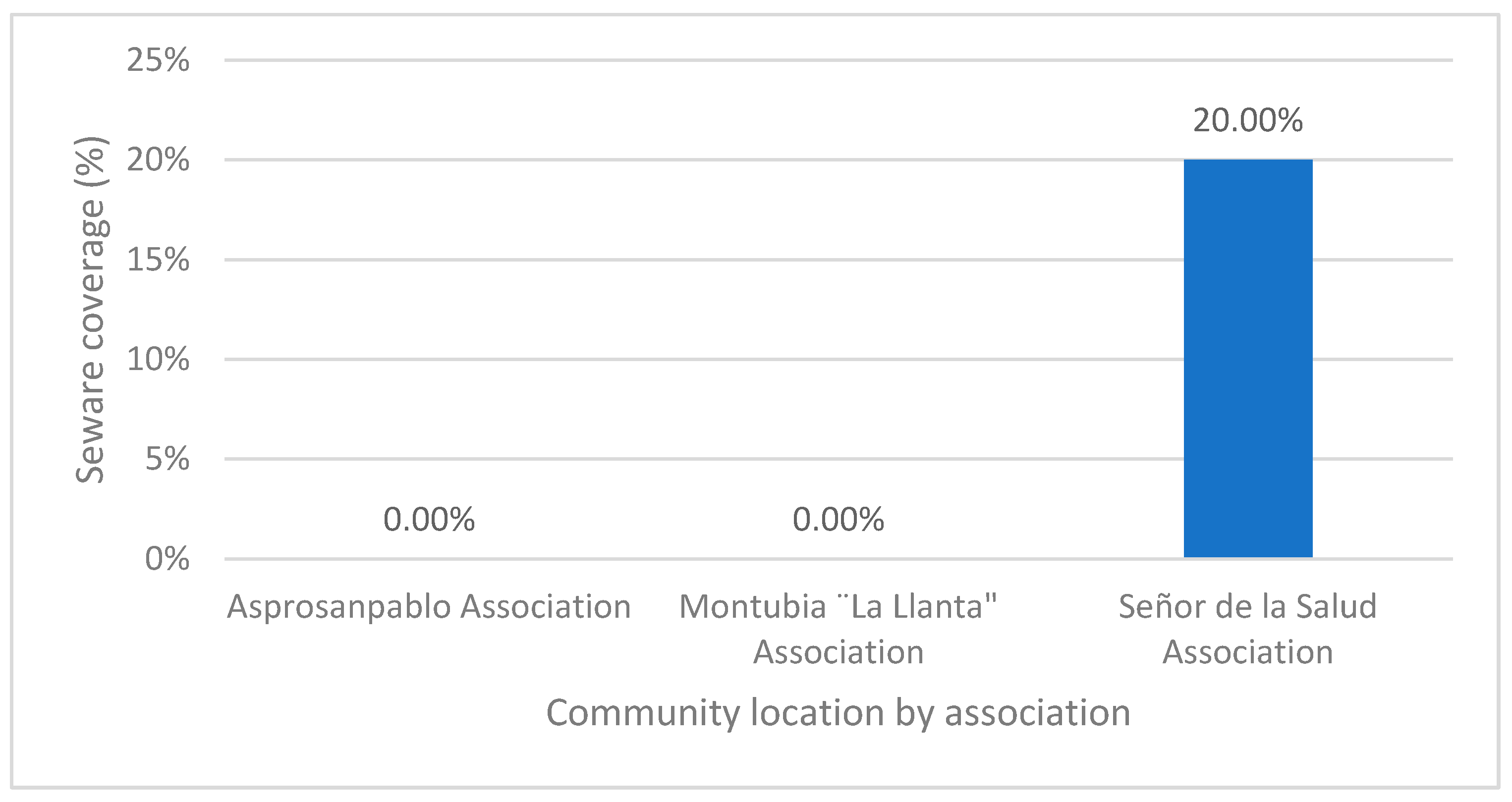

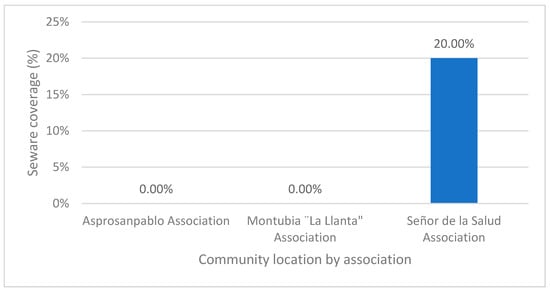

Asprosanpablo and Montubia “La Llanta” members reported that they do not have sewerage services (see Figure 5), and those of the association “Señor de la Salud” mentioned that they have a low coverage (20%). This situation is more common than is generally believed. Poor access to sewerage services and, thus, sanitation infrastructure is a global problem, primarily affecting rural areas (Huang et al. 2022). Here, having acceptable sanitation is very difficult for low-income people (McGranahan and Mitlin 2016), as well as the local government’s high investment and operational costs caused by low population density and dispersed households (Bo and Wen 2022; Huang et al. 2022). Therefore, access to sewerage in rural areas should be a priority to improve community habitat and meet the global sustainable development goals (GSDGs) (Zhong et al. 2023).

Figure 5.

Community Sanitation access.

In Ecuador, basic sanitation is considered the population’s access to an improved facility (sewerage, or failing that, a septic tank or cesspit) and the exclusive use of the toilet at home (Molina et al. 2018). In addition, there is a broad legal framework on the issue, as access to sanitation is in the Constitution as part of the right to a dignified life (Constitución de La República Del Ecuador 2008), and the decentralised autonomous governments are responsible for providing sewerage services (Ministerio de Coordinación de la Política 2011). In the province, the sewerage network is considered deficient. Specifically, in rural areas, this problem is more significant, as there is no evidence of any sewage treatment mechanism. According to the Municipal Government of Los Ríos, most households dispose of wastewater using septic tanks (50.57%), cesspits (15.23%) and other types of non-conventional mechanisms (16.85%), but only 17.35% of households have connection to the public sewerage network (GADP de Los Ríos 2019).

Organisations linked to the SSE may own and manage sewage structures, sanitation facilities, or wells as part of social development projects promoted by government or non-profit organisations. This management allows members of the SSE organisations to search for specific solutions appropriate for the associations and the community since they are involved in the decision-making processes (Katajamäki 2023; Villalba-Eguiluz et al. 2023). Therefore, the SSE can play an essential role in the inclusive circular economy by managing sanitation and balancing the social and environmental objectives of the communities where these associations are based. That is, they respond to the needs detected regarding the deficiency in health, which means that associates can live and work in a hygienic environment that is not dangerous to health.

4.3.4. Waste Recollection Coverage

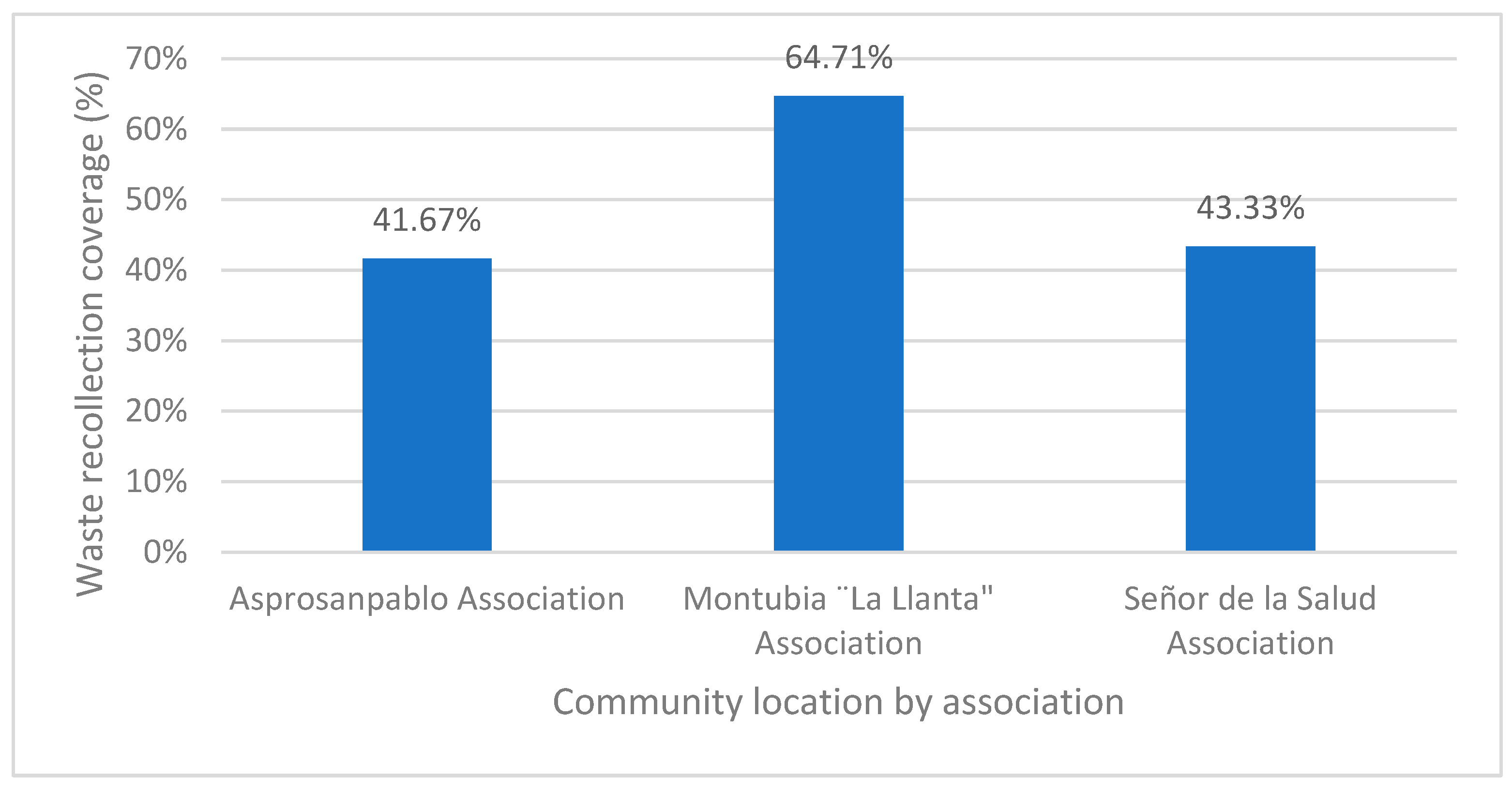

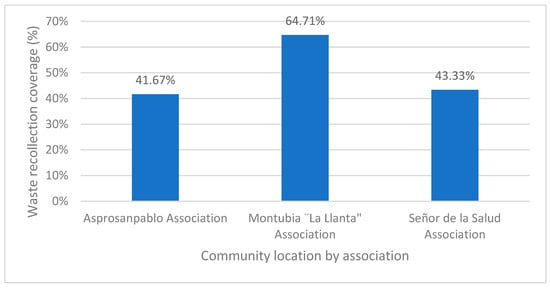

Informants mentioned the existence of access to waste collection, although its coverage is deficient. In Figure 6, the Asprosanpablo association (41.67%) shows the lowest value of waste collection compared to the Montubia Association “La Llanta” (64.71%). According to the Autonomous Decentralised Government of Los Ríos, waste collection is mostly in urban areas (62.69%), while the rest of the population buries or burns it (GADP de Los Ríos 2019).

Figure 6.

Community Waste recollection.

These wastes comprise food and green waste in about 60% of developing countries (Kharola et al. 2022). The management of this waste is the responsibility of the Municipal Autonomous Decentralised Governments (Ministerio de Coordinación de la Política 2011). However, they have low management capacity and no administrative and financial autonomy (Ministerio del Ambiente 2022). Therefore, one of the solutions observed for rubbish disposal in landfills, where there is no control, no defined areas, the presence of uncontrolled open dumps and, to a lesser extent, controlled landfills (Kharola et al. 2022).

There is a lack of waste treatment and recycling policies, which is why the SSE Organisation has become essential (Campagnaro and D’Urzo 2021). Organisations can improve local waste collection systems or participate in the waste management chain. In this way, these organisations can address important solutions for their socio-economic development, such as, apart from recycling, the reuse of textiles, plastics and other materials, the generation of fertilizers from food or fuel waste.

- (ii)

- Community income and debt

The community mostly mentions (81.04%) that the monthly income per family is 400 USD or less. They have no additional income, such as rent (98.28%) or access to remittances (91.38%). This income figure is lower than the national average household income (840 USD), as well as the basic food basket (541.91 USD) (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos 2023). This difference in income is a characteristic of rural areas, which concentrate a disproportionately low-income population compared to urban areas, and is also a common factor in the countries of the region (Hermida and Shalom 2022; Hernández-Vásquez et al. 2022).

For the improvement of the economic situation, it is necessary to access some individual factors such as bank loans (34.48%), training (1.72%), or subsidies (1.72%). However, the majority prefer a combination of these elements, such as bank loans and training (34.48%) or bank loans, training, and subsidies (5.17%). The desirable factors are loans and training. The latter is to be worked on actively between the university and the community.

The initiatives of the SSE organisations enable better socio-economic development by operating more sustainably. The rural sector is no exception, being able to consider the production of agroecological foods; recycling and reuse of inputs for the business economy, promoting the circular economy; the use and development of alternative energies; the use of community currency or barter (Campagnaro and D’Urzo 2021; Otsuki and de Castro 2020; Rossi et al. 2021).

- (iii)

- Perceived benefits and community collaboration

The associates considered the benefits of pursuing sustainable development as (i) Prosperity in quality of life, seen as a unique element (35.59%) or related to partnerships with other associations (20.34%) or to the protection of natural resources (11.86%); (ii) Partnership with other associations (5.08%) and (iii) Protection of natural resources (3.39%). Other combinations related to promoting peace, justice, and inclusive societies with the above arguments show a 23.73% acceptance.

Development in most developing countries is linked to agriculture (Kasem and Thapa 2012). The fact that agriculture is close to cooperatives can lead to an increase in inputs, the income of their members, and thus poverty alleviation (Blekking et al. 2021). This is an opportunity for members to obtain the desired prosperity in quality of life, and the university can actively participate in this process by addressing goals 1 (end poverty), 12 (responsible production and consumption) and 17 (alliances to achieve the goals) of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Informants consider collaborating on projects that allow them access to improve their production processes and basic services. This collaboration translates into continuous support from the community (69.49%) or occasional support (30.51%). This behaviour allows cooperative members to be more active, own more cultivated land and have higher levels of education (Blekking et al. 2021). In other words, this active participation combined with community engagement enables the realisation of activities according to the PAR methodology (Anonson et al. 2022; Fox et al. 2021; Siu and Xiao 2020). These initiatives of the SSE organisations enable better socio-economic development by operating more sustainably. The rural sector is no exception, being able to consider the production of agroecological foods, recycle and reuse inputs for the business economy, promote the circular economy, use and develop alternative energies, and use community currency or barter (Campagnaro and D’Urzo 2021; Otsuki and de Castro 2020; Rossi et al. 2021).

4.3.5. Community Project Activities

Once the data from the survey were collected, members of the associations were invited to a meeting, which was scheduled several weeks in advance. The purpose was to involve the community and its partners in working together to promote participatory action and capacity building. The partners were interested in the results and possible actions to take.

At the meeting, the data collectors presented the survey results, allowing space to discuss possible actions for social change. Participants were encouraged to share their thoughts and reflections on the diagnostic results, possible interventions, or future considerations.

In general terms, the information obtained shows a socio-economic panorama of the community:

- Deficient coverage of basic services. 41% of people have access to drinking water, 6.67% to sewerage, and 49.9% to rubbish collection—numbers below the national average.

- Insufficient income. Less than 400 USD for more than 81%. Most do not have additional income.

- Structural changes. They see access to bank financing and training as necessary. They are willing to carry out continuous support in the community in projects that allow them to revert deficiencies.

- Perceived benefits: Achieving prosperity in the quality of life (67.80%), based on the primary activity of these associations, agriculture, associativity in rural entrepreneurship and community organisation.

This information enabled the developing of a training programme focused on associations and their members as part of the community.

4.3.6. Training Programme

The social economy allows its members to develop social cohesion under a common purpose, solve their social problems, and improve their processes. Its members have a sense of belonging to a common cause, innovating services. The reasons, which allow the implementation of a training programme, are shown in two approaches:

- (i)

- A common training for all associations in which the functions and benefits of the Popular and Solidarity Economy are explained, as well as related laws and the SDGs. This programme lasts eight weeks and 86 h of training (see Table 7).

Table 7. Participatory Action Research (PAR) in general capacitation program.

Table 7. Participatory Action Research (PAR) in general capacitation program. - (ii)

- A specific training for the business activity of the association. The programme lasts five weeks and 50 h (see Table 8).

Table 8. Participatory Action Research (PAR) in specific capacitation program.

Table 8. Participatory Action Research (PAR) in specific capacitation program.

5. Discussion

The social economy has gained importance in recent years by prioritising social objectives over economic ones, seeking social cohesion, cooperation and solidarity among its members (Bergeron et al. 2015; Utting et al. 2014). The community-association-university partnership described in this research shows how the rural area in a developing country is a natural setting that allows the study of the social and solidarity economy and its development in human groups associated with various economic activities (see Table 4).

SSE is an alternative when studying vulnerable groups that require substantial improvements in economic and social development, new forms of participation and relationships among their members, and the creation or improvement of structures and processes (Matei and Dorobantu 2015; Neamtan 2002). In particular, these groups must receive support to strengthen their capacities and encourage them to carry out their activities to achieve sustainability. The participatory action method (PAR) is appropriate to the reality of these stakeholders, and all stages of this study are applied (Anonson et al. 2022; Ku and Kan 2020). However, its study in developing countries in rural communities is scarce.

The support of the university in the rural sector is essential because of the guidance and credibility they show in their activities towards the community and associations. The rural sector is aware of its limitations, so a collaboration to determine its socio-economic situation and intervention to organise associations and support in the training process make it a strategic partner.

This research contributes to the academic literature on the Social and Solidarity Economy by considering their social entities and the changes they can undergo to pursue sustainable development through an action-participation proposal based on PAR as a social, collaborative, and practical process. This allows us to know firsthand the associations’ members’ needs, concerns, and experiences (Anonson et al. 2022; Bradbury et al. 2019). This proposal has allowed the communities studied to perceive an added value in their social economy because of the following: (a) It is possible to associate university-community-associations to identify problems and seek solutions; (b) They obtain greater inclusion among their members in the activities of the associations, including people who usually have no decision-making power or are vulnerable; (c) They applied the SSE principles, showing that the associations have commitments to the community by showing concern about the socio-economic condition of the places where they have their operations; (d) They fostered the improvement of human capital by establishing a training programme where the production of knowledge is democratic, thus combining theoretical and practical elements according to the needs of the associates.

6. Conclusions

The social economy allows a society’s resources to be shared equitably by prioritising social objectives and empowering its members to seek solutions to their economic, social, and environmental problems. This article contributes to this debate by considering popular and solidarity economy associations in the rural sector in Ecuador. The research focuses on three agricultural associations where their members face diverse socio-economic and management problems. This research presented the challenge of achieving interaction between the university, associations, and the community using the Participatory Action Research method to involve these groups in the design, development, and evaluation of research, which allows them to diagnose and seek solutions to alleviate these problems to some degree.

Three rural associations related to agricultural activities, with the auspices of the university, establish relations with a written commitment to collaboration. This alliance allowed us to explore how the SSE can develop and present the transformative potential for the sustainable development of its organisations and members, which entails a potential benefit to its community. The study demonstrated that interaction between the university, associations, and the community is possible, where those involved have co-learning, and their needs, concerns, and experiences can be better understood. This interaction allows them to obtain information to design, develop, and evaluate the research, obtain a socio-economic diagnosis of the communities, and establish a training programme to begin their sustainable development. The training programme allows members of the associations to strengthen their knowledge, make improvements in production processes, and learn how these can contribute to the reduction of inequalities. This last aspect is complex to address and is becoming a recurring issue in the rural areas of Ecuador and Latin America. In the study sector, members of ESS associations show low income, inadequate coverage of drinking water and sanitation, and government negligence. It is a complex situation that has an initial change with the intervention of the actors involved in the investigation. Establishing practices and strategies by associations promotes citizen participation, community development, social change, and access to resources and services currently limited among their members.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, J.L.-M., L.A., N.M.-B. and R.P.-S.; methodology, J.L.-M., L.A., N.M.-B., L.C.-M. and R.P.-S.; validation, J.L.-M., L.A., N.M.-B. and L.C.-M.; formal analysis, J.L.-M., L.A., N.M.-B. and L.C.-M.; investigation, J.L.-M., L.A., N.M.-B. and L.C.-M.; resources, J.L.-M. and L.A.; data curation, J.L.-M., L.A., N.M.-B. and L.C.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.-M., L.A., N.M.-B., L.C.-M. and R.P.-S.; writing—review and editing, J.L.-M., L.A., N.M.-B., L.C.-M. and R.P.-S.; visualisation, J.L.-M. and N.M.-B.; supervision, J.L.-M.; project administration, J.L.-M.; funding acquisition, J.L.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require an ethical review or approval as it does not involve medical patients, and the information gathered is not associated with medical research (Declaration of Helsinki, October 2008). The data collection techniques and question design were carried out in collaboration with the members of the associations, who signed an agreement with the university (see Section 4.2, “Establishment of commitments” and “Community Researchers: Training and Collaboration”).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the research project of Quevedo State Technical University, “Strengthening of Popular and Solidarity Economy organisations as an instrument of territorial economic development in Quevedo and its area of influence”, with code FCSEF-PVSUTEQ-FCE-11. We also appreciate the support of NOVA Science Research Associates. Finally, the authors appreciate the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Acosta, Alberto. 2017. Living Well: Ideas for reinventing the future. Third World Quarterly 38: 2600–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anonson, June, Hyuna Bae, Jade Anderson, Melanie Kaczur, Brenda Mishak, and Sandy Galbraith. 2022. A collaborative approach to studying homelessness in rural Saskatchewan through participatory action research. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice 26: 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arampatzi, Athina. 2020. Social solidarity economy and urban commoning in post-crisis contexts: Madrid and Athens in a comparative perspective. Journal of Urban Affairs 44: 1375–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arguello Núñez, León Benigno, Walther Boanerge Purcachi Aguirre, and Mario Alejandro Pérez Arévalo. 2019. La economía popular y solidaria en el desarrollo territorial. Análisis de las organizaciones del sector no financiero en la provincia de los Ríos-Ecuador. Revista Científica Olimpia 16, 53, Edición Especial. Available online: https://revistas.udg.co.cu/index.php/olimpia/article/view/644 (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Bell, Myrtle P., Joy Leopold, Daphne Berry, and Alison V. Hall. 2018. Diversity, Discrimination, and Persistent Inequality: Hope for the Future through the Solidarity Economy Movement. Journal of Social Issues 74: 224–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellino, Michelle J., Vidur Chopra, and Nikhit D’Sa. 2021. “Slowly by Slowly”: Youth Participatory Action Research in Contexts of Displacement. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education 123: 145–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, Suzanne, Stephen Healy, Carina Millstone, Bénédicte Fonteneau, Georgina Gómez, Marguerite Mendell, Paul Nelson, John-Justin McMurtry, Cecilia Rossel, and Abhijit Ghosh. 2015. Social and Solidarity Economy: Beyond the Fringe. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Blekking, Jordan, Nicolas Gatti, Kurt Waldman, Tom Evans, and Kathy Baylis. 2021. The benefits and limitations of agricultural input cooperatives in Zambia. World Development 146: 105616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, Yang, and Wang Wen. 2022. Treatment and technology of domestic sewage for improvement of rural environment in China. Journal of King Saud University-Science 34: 102181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzaga, Carlo, Gianluca Salvatori, and Riccardo Bodini. 2019. Social and Solidarity Economy and the Future of Work. Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Emerging Economies 5: 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, Hilary, and Peter Reason. 2003. Action Research. An Opportunity for Revitalizing Research Purpose and Practices. Qualitative Social Work 2: 155–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, Hilary, Steve Waddell, Karen O’Brien, Marina Apgar, Ben Teehankee, and Ioan Fazey. 2019. A call to Action Research for Transformations: The times demand it. Action Research 17: 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, Sara, Stephen Syrett, and Andres Morales. 2020. The political institutionalization of the social economy in Ecuador: Indigeneity and institutional logics. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 38: 269–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnaro, Cristian, and Marco D’Urzo. 2021. Social Cooperation as a Driver for a Social and Solidarity Focused Approach to the Circular Economy. Sustainability 13: 10145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelao Caruana, Maria Eugenia, and Cynthia Cecilia Srnec. 2013. Public Policies Addressed to the Social and Solidarity Economy in South America. Toward a New Model? VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 24: 713–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEPAL. 2022. CEPAL presenta en Chile estudios sobre cooperativismo y economía social en América Latina para contribuir al desarrollo del sector en el país. Available online: https://www.cepal.org/es/notas/cepal-presenta-chile-estudios-cooperativismo-economia-social-america-latina-contribuir-al (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Chaves-Avila, Rafael, and Juan Ramon Gallego-Bono. 2020. Transformative Policies for the Social and Solidarity Economy: The New Generation of Public Policies Fostering the Social Economy in Order to Achieve Sustainable Development Goals. The European and Spanish Cases. Sustainability 12: 4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comercio, R. El. 2018. Radiografía Económica de la provincia de Los Ríos. Available online: https://www.elcomercio.com/pages/economia-provincia-rios.html (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Constitución de La República Del Ecuador. 2008. Biblioteca LEXIS. Available online: https://www.lexis.com.ec/biblioteca/constitucion-republica-ecuador (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Coraggio, José Luis. 2015. Institutionalising the Social and Solidarity Economy in Latin America. In Social and Solidarity Economy: Beyond the Fringe. Edited by Peter Utting. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 130–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, Anup. 2016. An Epistemological Reflection on Social and Solidarity Economy. Forum for Social Economics 45: 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudgeon, Pat, Clair Scrine, Adele Cox, and Roz Walker. 2017. Facilitating Empowerment and Self-Determination Through Participatory Action Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duijs, Saskia E., Vivianne E. Baur, and Tineke A. Abma. 2021. Why action needs compassion: Creating space for experiences of powerlessness and suffering in participatory action research. Action Research 19: 498–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, Ana Margarida. 2014. Decolonizing Livelihoods, Decolonizing the Will: Solidarity economy as a social justice paradigm in Latin America. In Routledge International Handbook of Social Justice. Edited by Michael Reisch. Abingdon: Rouledge, pp. 74–90. [Google Scholar]

- Esteves, Ana Margarida, Audley Genus, Thomas Henfrey, Gil Penha-Lopes, and May East. 2021. Sustainable entrepreneurship and the Sustainable Development Goals: Community-led initiatives, the social solidarity economy and commons ecologies. Business Strategy and the Environment 30: 1423–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, Gretchen. 2018. The Social Economy in Bolivia: Indigeneity, Solidarity, and Alternatives to Capitalism. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 29: 1233–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonteneau, Bénédicte, Nancy Neamtan, Fredrick Wanyama, Leandro Morais, Mathieu de Poorter, Carlo Borzaga, Giulia Galera, Tom Fox, and Nathaneal Ojong. 2011. Social and Solidarity Economy: Our Common Road towards Decent Work. Available online: https://www.socioeco.org/bdf_fiche-outil-10_en.html (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Fox, Mim, Dominque Hopkins, and Jenni Graves. 2021. Building research capacity in hospital-based social workers: A participatory action research approach. Qualitative Social Work 22: 123–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GADP de Los Ríos. 2019. Gobierno de Los Ríos—PDOT Diagnóstico. Plan de Desarrollo y Ordenamiento Territorial 2020–2025. Available online: https://losrios.gob.ec/diagnostico (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- García-Lorenzo, Iria, Manuel Varela-Lafuente, María Dolores Garza-Gil, and U. Rashid Sumaila. 2024. Social and solidarity economy in small-scale fisheries: An international analysis. Ocean & Coastal Management 253: 107166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleerup, Janne, Lars Hulgaard, and Simon Teasdale. 2019. Action research and participatory democracy in social enterprise. Social Enterprise Journal 16: 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goranczewski, Bolesław, and Daniel Puciato. 2011. SWOT analysis in the formulation of tourism development strategies for destinations. Turyzm/Tourism 20: 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grugel, Jean, and Pía Riggirozzi. 2012. Post-neoliberalism in Latin America: Rebuilding and Reclaiming the State after Crisis. Development and Change 43: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Elliott, Chantal Line Carpentier, Sara Castro de Hallgren, Alex Julca, Santiago Rodriguez Goicoechea, Babken Der Gregorian, Danon Gnezale, Sebastien Vauzelle, and Amritpal Singh Virdee. 2023. Setting a Path towards New Economics for Sustainable Development—An Overview. Available online: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/nesd_overview_20_march.pdf#page=10.04 (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Heard, Emma. 2022. Ethical challenges in participatory action research: Experiences and insights from an arts-based study in the pacific. Qualitative Research 23: 1112–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, Marisa, Chantal Line Carpentier, Raymond Landveld, Raidan Al-Saqqaf, Olaf Jan de Groot, Michal Podolski, Andrea Antonelli, Nurjemal Jalilova, and Diandra Pratami. 2023. New Economics for Sustaianble Development—Creative Economy. United Nations Economist Network. Available online: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/orange_economy_14_march.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Hermida, María Julia, and Diego Edgar Shalom. 2022. Child Cognitive Development in Latin American Rural Poverty: What Should Researchers Consider for Conducting Fieldwork? In Cognitive Sciences and Education in Non-WEIRD Populations. Cham: Springer, pp. 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Vásquez, Akram, Fabriccio J. Visconti-Lopez, and Rodrigo Vargas-Fernández. 2022. Factors Associated with Food Insecurity in Latin America and the Caribbean Countries: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of 13 Countries. Nutrients 14: 3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Yuansheng, Lizhou Wu, Peng Li, Nanke Li, and Yiliang He. 2022. What’s the cost-effective pattern for rural wastewater treatment? Journal of Environmental Management 303: 114226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos. 2022. INEC Población y Demografía. Available online: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/estadisticas/ (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos. 2023. Índice de Precios al Consumidor (IPC) Marzo 2023. Available online: https://www.indec.gob.ar/uploads/informesdeprensa/ipc_04_23411BFA2B5E.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Johnson, Holly, and Catherine Flynn. 2021. Collaboration for Improving Social Work Practice: The Promise of Feminist Participatory Action Research. Affilia 36: 441–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasem, Sukallaya, and Gopal B. Thapa. 2012. Sustainable development policies and achievements in the context of the agriculture sector in Thailand. Sustainable Development 20: 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katajamäki, Waltteri. 2023. Energy, water and waste management sectors. In Encyclopedia of the Social and Solidarity Economy. Edited by Ilcheong Yi. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kharola, Shristi, Mangey Ram, Nupur Goyal, Sachin Kumar Mangla, O. P. Nautiyal, Anita Rawat, Yigit Kazancoglu, and Durgesh Pant. 2022. Barriers to organic waste management in a circular economy. Journal of Cleaner Production 362: 132282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, Sean, Larry Davidson, Tyler Frederick, and Michael J. Kral. 2018. Reflecting on Participatory, Action-Oriented Research Methods in Community Psychology: Progress, Problems, and Paths Forward. American Journal of Community Psychology 61: 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kothari, Ashish, Federico Demaria, and Alberto Acosta. 2014. Buen Vivir, Degrowth and Ecological Swaraj: Alternatives to sustainable development and the Green Economy. Development 57: 362–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, Hok Bun, and Karita Kan. 2020. Social work and sustainable rural development: The practice of social economy in China. International Journal of Social Welfare 29: 346–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langergaard, Luise Li, and Jacob Dahl Rendtorff. 2022. Introduction: New Economies for Sustainability: Limits and Potentials for Possible Futures. In New Economies for Sustainability: Limits and Potentials for Possible Futures. Cham: Springer, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrabure, Manuel, Marcelo Vieta, and Daniel Schugurensky. 2011. The ‘New Cooperativism’ in Latin America: Worker-Recuperated Enterprises and Socialist Production Units. Studies in the Education of Adults 43: 181–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. 2020. Role of social and solidarity economy in localizing the sustainable development goals. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology 27: 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaître, Andreia, and Albertus Hendrikus Johannes Helmsing. 2012. Solidarity Economy in Brazil: Movement, Discourse and Practice Analysis Through a Polanyian Understanding of the Economy. Journal of International Development 24: 745–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley Orgánica de La Economía Popular y Solidaria. 2011. Pub. L. No. Registro Oficial 29, Suplemento II. Available online: www.gob.ec/sites/default/files/regulations/2020-02/Documento_Ley-Orgánica-Economía-Popular-Solidaria.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Line Carpentier, Chantal. 2023. New Economics for Sustaianble Development. Attention Economy. United Nations Economist Network. Available online: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/attention_economy_feb.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Maldonado-Erazo, Claudia Patricia, María de la Cruz del Río-Rama, Erica Estefanía Andino-Peñafiel, and José Álvarez-García. 2023. Social Use through Tourism of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of the Amazonian Kichwa Nationality. Land 12: 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malta, Mariana Curado, and Ana Alice Baptista. 2013. Social and Solidarity Economy Web Information Systems. In Social E-Enterprise: Value Creation through ICT. Pennsylvania: IGI Global, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, Ani, and Adela Daniela Dorobantu. 2015. Social Economy—Added Value for Local Development and Social Cohesion. Procedia Economics and Finance 26: 490–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGranahan, Gordon, and Diana Mitlin. 2016. Learning from Sustained Success: How Community-Driven Initiatives to Improve Urban Sanitation Can Meet the Challenges. World Development 87: 307–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Coordinación de la Política. 2011. Código Orgánico de Organización Territorial, Autonomía y Descentralización—COOTAD. Available online: www.gob.ec/sites/default/files/regulations/2021-01/Documento_Codigo-Orgánico-Organización-Territorial-Autonomia-Descentralización.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Ministerio del Ambiente. 2022. Programa ‘PNGIDS’ Ecuador. Available online: https://www.ambiente.gob.ec/programa-pngids-ecuador/ (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Molina, Andrea, Monica Pozo, and Juan Carlos Serrano. 2018. Agua, Saneamiento e Higiene: Medición de los ODS en Ecuador. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/ecuador/media/1156/file/Agua,%20saneamiento%20e%20higiene.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Neamtan, Nancy. 2002. The Social and Solidarity Economy: Towards an ‘Alternative’ Globalisation. Available online: http://www.socioeco.org/bdf_fiche-document-2084_en.html (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- OECD. 2024. Mapping Social and Solidarity Ecosystems around the World. Paris: OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/social-economy/oecd-global-action/country-fact-sheets.htm (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Otsuki, Kei, and Fabio de Castro. 2020. Solidarity Economy in Brazil: Towards Institutionalization of Sharing and Agroecological Practices. In Sharing Ecosystem Services: Building More Sustainable and Resilient Society. Singapore: Springer, pp. 159–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickton, David W., and Sheila Wright. 1998. What’s swot in strategic analysis? Strategic Change 7: 101–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz-Niño, Catalina, and María Ángeles Murga-Menoyo. 2017. Social and Solidarity Economy, Sustainable Development Goals, and Community Development: The Mission of Adult Education & Training. Sustainability 9: 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Insuasti, Homero, Néstor Montalván-Burbano, Otto Suárez-Rodríguez, Marcela Yonfá-Medranda, and Katherine Parrales-Guerrero. 2022. Creative Economy: A Worldwide Research in Business, Management and Accounting. Sustainability 14: 16010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, Adanella, Mario Coscarello, and Davide Biolghini. 2021. (Re)Commoning Food and Food Systems. The Contribution of Social Innovation from Solidarity Economy. Agriculture 11: 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saguier, Marcelo, and Zoe Brent. 2017. Social and Solidarity Economy in South American regional governance. Global Social Policy 17: 259–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahakian, Marlyne. 2016. The Social and Solidarity Economy: Why Is It Relevant to Industrial Ecology? In Taking Stock of Industrial Ecology. Cham: Springer, pp. 205–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, Jeannette. 2016. Institucionalidad y políticas para la economía popular y solidaria: Balance de la experiencia ecuatoriana. In Economía Solidaria. Historias y prácticas de su fortalecimiento. pp. 35–48. Available online: https://biblio.flacsoandes.edu.ec/libros/digital/56679.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Siu, Kin Wai Michael, and Jia Xin Xiao. 2020. Public facility design for sustainability: Participatory action research on household recycling in Hong Kong. Action Research 18: 448–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparre, Mogens. 2020. Utilizing Participatory Action Research to Change Perception About Organizational Culture From Knowledge Consumption to Knowledge Creation. Sage Open 10: 215824401990017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Superintendency of Popular and Solidarity Economy. 2024. Data SEPS. Available online: https://data.seps.gob.ec/#/dashboards/home (accessed on 19 May 2024).

- Supersolidaria. 2022. Superintendente de la Economía Solidaria Habló Sobre el Presente y Futuro del Sector Solidario. Available online: https://www.supersolidaria.gov.co/es/content/superintendente-de-la-economia-solidaria-hablo-sobre-el-presente-y-futuro-del-sector (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Tello-Rozas, Sonia. 2016. Inclusive Innovations Through Social and Solidarity Economy Initiatives: A Process Analysis of a Peruvian Case Study. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 27: 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF. 2017. Estrategia de Agua, Saneamiento e Higiene 2016–2030. New York: UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- Utting, Peter. 2017. Public Policies for Social and Solidarity Economy: Assessing Progress in Seven Countries. Geneva: ILO/International Labour Office. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/publications/public-policies-social-and-solidarity-economy-assessing-progress-seven (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Utting, Peter, Nadine van Dijk, and Marie-Adélaïde Matheï. 2014. Social and Solidarity Economy: Is There a New Economy in the Making? UNRISD Occasional Paper 10: Potential and Limits of Social and Solidarity Economy. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10419/148793 (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Veltmeyer, Henry. 2018. The social economy in Latin America as alternative development. Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne d’études Du Développement 39: 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba-Eguiluz, Unai, Asier Arcos-Alonso, Juan Carlos Pérez de Mendiguren, and Leticia Urretabizkaia. 2020. Social and Solidarity Economy in Ecuador: Fostering an Alternative Development Model? Sustainability 12: 6876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba-Eguiluz, Unai, Marlyne Sahakian, Catalina González-Jamett, and Enekoitz Etxezarreta. 2023. Social and solidarity economy insights for the circular economy: Limited-profit and sufficiency. Journal of Cleaner Production 418: 138050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallimann, Isidor. 2014. Social and solidarity economy for sustainable development: Its premises—And the Social Economy Basel example of practice. International Review of Sociology 24: 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendt, Wolf Rainer. 2022. Solidarity in Care and Social Economy. In Doing Care and Doing Economy. Wiesbaden: Springer, pp. 125–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, I., F. Farinelli, and R. Landveld. 2023. New Economics for Sustainable Development. Social and Solidarity Economy. United Nations Economist Network. Available online: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/social_and_solidarity_economy_29_march_2023.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2024).

- Zhang, Chuan-Hong, Wandella Amos Benjamin, and Miao Wang. 2021. The contribution of cooperative irrigation scheme to poverty reduction in Tanzania. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 20: 953–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]