Abstract

Sport mega-events (SMEs) remake cities as global brandscapes of leisured consumption; reliant in part upon securitization designed to create an atmosphere free from disturbance and render invisible those “abject” populations who might puncture the tourist bubble that surrounds stadia and fan-zones. Yet, such “shiny” cityspaces are not devoid of complexity, contestation, and compunction. In this paper, we draw on extensive ethnographic- and community-based participatory research in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (prior to, during, and after two SMEs) collected in collaboration with sex workers, working in areas of SME intervention. Our focus is on the contingent nature of securitization amidst the contested terrains and trajectories of SME urbanism. Our analysis resonates with observations from other host cities, challenging dominant myths that the sport mega-event creates impermeable securitized cityscapes by revealing the fluid topography of formality and informality, contestation and negotiation, and oppression and power.

1. Dialectics of Security: “Security” as Practices of Governance

We are increasingly governed through security or under the guise of security. The term “security” carries significant weight across diverse domains. From ensuring food security and human security to cybersecurity and “securities” as a tradeable financial asset, through to the type of surveillance security within public streets and in spaces such as malls, stadiums, and airports, there exists a noticeable trend wherein state agencies, private security firms, and even non-state actors increasingly utilize a growing variety of technologies to monitor, militarize, and “secure” spaces and activities. With its proliferation and popular deployments, security is hardly considered the realm of experts, their machinery, or their cavalry, but has become an expectation bestowed upon ordinary people. As Valverde (2011, p. 4) earlier writes, “Neighbours, teachers, parents, bank tellers, air travellers and numerous other groups are constantly exhorted to watch for security breaches or risks and do their part”.

Despite, or perhaps due to, their widespread implementation, security initiatives frequently express internal contradictions and inconsistencies. One notable example is the supposed “modernizing” of policing practices, which continue to exacerbate historical patterns for marginalized, mostly racialized groups. Efforts aimed at ensuring security persistently grapple with its complexities and adverse consequences, exhibiting its internal contradictions. Indeed, Beck (1992) contended that while modern societies have made considerable strides in managing traditional risks such as those stemming from natural disasters and infectious diseases, they concurrently introduce new risks through technological innovations and industrial processes. For instance, surveillance technologies, ostensibly designed to bolster security, often encroach upon individual privacy rights and engender new vulnerabilities, such as data breaches and cyber assaults. Beck introduced the concept of “manufactured risks” to delineate these novel hazards, which are frequently obscure, intricate, and resistant to prediction or control. His argument that technologies developed to enhance security often inadvertently generate new risks emphasizes the objects of security without acknowledging the internal contradictions of security. Ultimately, irrespective of the latest devices or technological advancements—characteristic of so-called modern societies in a globalizing world—security remains inherently conflicted.

Valverde (2011) underscores the inherent paradoxes of security, viewing it not as a static concept or tangible entity, but as dynamic and internally contradictory practices of governance. Valverde (2011, p. 5) argues that while the term “security” is grammatically employed as a noun, caution is needed against assuming its concrete existence—it is dangerous to assume that “security actually exists, even as a fuzzy concept” (2011, p. 5). Valverde posits that security is contingent, concluding, “all that we can know about security is what people do in its name, and that therefore our focus should be on practices of governance that in fact appeal to ‘security’” (2011, p. 5). Consequently, she advocates for a shift away from generalized theories of security towards an adaptable, content-neutral framework conducive to empirical investigations into security governance, with the aim of elucidating its practical manifestations. We follow her work in this paper as we unpack the messy, localized contestation of security practices in Rio de Janeiro before, during, and after two sport mega-events—the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games. Through a focus on local actors, our emphasis is on understanding security as a practice, or set of governance practices, that are performed with full knowledge that an actual objective condition of security is “probably unattainable and at best impermanent” (Zedner 2009, p. 19).

2. Security and the Sport Mega-Event

Security practices at sport mega-events have attracted considerable attention, particularly in a post-9/11 era. As suggested by Whelan (2014), surveillance and security studies of the sport mega-event (namely the Olympics and FIFA World Cup) tend to focus on three overlapping issues: (i) security “legacies” of sport mega-events; (ii) security risks and the infrastructures and technologies used in attempt to manage those risks; and (iii) the overall “security spectacle” that characterizes sport mega-events. Each theme is briefly overviewed now.

Giulianotti and Klauser (2010, p. 54) call attention to six security legacies: security technologies; new security practices; governmental policies and new legislation; externally imposed social transformations; generalized changes in social and trans-societal relationships; and urban development. Whelan (2014) notes that security technologies such as surveillance systems are often the focus of most critical sport mega-event security studies, yet, increasingly, legacies of newly adopted governmental policies and legislative reform are considered in analyses—particularly the legislative powers bestowed to police and security agencies. For example, the influx of federal funding and resources for the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles bolstered the capacity of law enforcement agencies, enabling widespread surveillance capabilities and newly enacted militarized policing strategies. This militarization of policing, coupled with racial biases and discriminatory practices, contributed to the erosion of trust between law enforcement and Black and Brown communities in Los Angeles. A recent investigation of such legacies demonstrates that “much of the [1984 Olympic] security budget went towards more personnel and weapons that would go on to normalize extreme, violent practices and the idea of a fully militarized police department as the new reality” (NOlympicsLA 2020, para. 13). One egregious legacy is Operation Hammer, which expanded upon the “gang sweeps” that occurred across Los Angeles in preparation for the games, and targeted young Black and Brown men—the use of excessive police force was eventually captured on camera with the violent, forceful arrest of Rodney King.

Security risks at sport mega-events are identified by three categories: (i) terrorism; (ii) spectator and political violence; and (iii) poverty, social divisions, and urban crime. Collectively, these categories are used to rationalize the enormous investment in infrastructures and technologies. For example, Fussey et al. (2011) describe the “total” security model implemented at the 2012 London Games that (i) involved intense planning for “resilience” should a terrorist attack eventuate; (ii) the development of “island” security and the transformation of public and private space through “defensible space” techniques at key sites; and, finally, (iii) the deployment of advanced surveillance technologies, which were intended to monitor people and space and expanded the existent network in host communities. Atkinson and Young (2012) further extrapolate from such studies of risk and its infrastructures to argue that the omnipresent risk of terrorism has transformed the organization and experience of sporting events, influencing public perceptions of risk and associated policy.

Overall, event securities and the intense militarization of host cities is thought to contribute to a “security spectacle” rather than deter or remedy actual security risks. In host cities, it is typical to witness RAF fighters soaring overhead, long-range surface-to-air missiles stationed at various points, portable missiles visibly positioned on buildings near Olympic sites, drones hovering above, parked tanks, docked aircraft carriers, and the strategic deployment of tactile teams and snipers near venues (see especially Manley and Silk 2014). Boyle and Haggerty (2009) argue that security spectacles are largely about providing the illusion of “absolute security” or the appearance of control despite uncertainty. Such enormous displays of security, whilst increasing feelings of “security” for some exacerbate feelings of “insecurity” in others familiarly forced into its theatre (Zedner 2009).

Few studies have complicated the “totalizing rhetoric” of mega-event security (Muller 2015, with notable exceptions such as Cornelissen 2011; Pauschinger 2020; Paton et al. 2012). Indeed, whilst mega-event securities might be overdetermined by “exclusive corporate territorial enclaves within the Olympic city” (Duignan and McGillivray 2019, p. 709), there exists little work on the contingent nature of securitization and how city spaces are indeed far messier, contested terrains. Through ethnographic work during the 2016 Rio Olympics, (Duignan and McGillivray 2019; Duignan et al. 2020, 2022) attended to these in-between spaces—the physical, spatial, and imagined borders, boundaries, barriers, and buffers between the allegedly “formal” and the “informal” city. Their work reveals moments of disorganization in which microentrepreneurs reimagine “official” corporate merchandise and exploit gaps to secure their own livelihoods, noting that exceptional legislation was inconsistently applied by law enforcement, and that efforts to securitize visitor flows and mobility are never guaranteed. With Pavoni (2015, 2017), this paints a more complex picture than any totalizing rhetoric, instead recognizing the internal contradictions, frictions, and resistances—however fleeting, dangerous, necessary, or indeed mundane—inherent to security. This type of approach invites us to strip back the “urban macula” (Silk 2010), and understand the dispossessive tendencies of mega-event development, its convergence with broader nodes and modes of neoliberal capitalism, and—given our focus—the creative capacities of people laboring in popular economies. In so doing, we add to the literatures on “contestation” at the sport mega-event, furthering understandings of what Horne (2015) terms the three main sites of political contestation—rights, legacy, and labor. Specifically, we can begin to gather a more nuanced recognition of the localised and diverse impacts of the sport mega-event on host communities, popularly figured as victim or vulnerable, and the continued innovation needed to harness urban interstices and exceptions (De Lisio et al. 2019b; De Lisio and Sodre 2019).

Despite advancing our knowledge of security planning, infrastructures, surveillance technologies, and their ongoing legacies, there remains something of a scholarly lacuna that examines how local contexts both enable and constrain entrepreneurial action generally and in the context of sport mega-events (see Duignan et al. 2020). The work alluded to in this section mostly focused on tourist experiences—albeit supplemented with some fascinating observational/visual insights—with little-to-no voice or perspective from local actors. Indeed, Duignan and McGillivray (2019) point to the need for longer periods of ethnographic engagement that extends from the “live staging” focus of their work. They suggest the need for extended ethnographic work that can examine lived spatial transformations in the build up to and in the legacies of mega-events. Thus, we aim to both complement and extend work to date through an extended longitudinal exploration with groups in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, prior to, during, and after the 2014 FIFA World Cup and 2016 Olympic Games. Through long-term engagement with host communities, this work advances sport mega-event security studies through a particular focus on how sport mega-event “security” is coordinated by actually existing practices and systems of governance. While virtually all analysts recognize that “sporting mega-events involve a level of organization unmatched outside of wartime and planning that requires significant alteration to the governance of the host city or country” (Fussey and Coaffee 2012, p. 2), very few have sought to examine how security agents actually negotiate and mediate established practices amongst and within host communities. For this reason, an analysis of security logics, scope, and techniques that is attentive to security’s inherent everyday contradictions and dynamics is needed.

3. Methodological Approach: Everyday in/Securities in Event Cities

The data discussed herein were drawn from an integrated methodological approach that included (i) document analyses of “official” development plans and policing strategies for the sport mega-event; (ii) the collection of observational data (Hammersley and Atkinson 2019; Markula and Silk 2011); and (iii) context-building conversational interview data (both formal and informal) with over 100 interviewees (mostly ciswomen and travesti sex workers). Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Toronto (ID: 29538, 12 March 2013), Bournemouth University (ID: 12427, 10 August 2016), and the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (ID: 55633816-8-0000-5699, 1 July 2016). Data collection occurred across two studies centred on the preparation for, the staging of, and the “legacy” of the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Rio Olympic Games respectively.1 Potential concerns with access, risk, power relations, and trust were mitigated through the longevity of the data collection period, which led to familiarity and integration. Furthermore, to counter such concerns, we worked in collaboration with the Prostitution Policy Watch at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and were present in the field at various stages between April 2014 and August 20182. One author, De Lisio, lived in Rio de Janeiro for one year and continues to work with respective collaborators and community groups, virtually, especially during the pandemic, and in-person, returning in December 2022 for an additional month of research. Time not spent in Brazil is used to leverage opportunities for knowledge mobilization, translation of relevant Brazilian sex worker-authored material, and the writing of various applications to financially support the continuance of partnered research activities. Data analysis focused largely on urban mobilities and creative (socio-spatial) opposition to, and contestation of, everyday insecurities in mega-event Rio de Janeiro.3 Our intent was to learn from the often-silenced stories of event hosting, and our integrative dataset, which included document analysis, interview, and observational data, allowed us to do so. We now analyse a small subset of this larger dataset to illustrate security practices in 2014/2016 host contexts. Analyses thus homed in on one particular concern: the consequence of mega-event “security” on sex workers in Rio de Janeiro.

4. Practices of Governance in Mega-Event Rio de Janeiro

A dominant discourse of urban insecurity is often mobilized to rationalize mega-event investment in securities—i.e., the deployment of expansive personnel, technologies, and hardware. In this section, we speak to the collision of practices of governance in Rio de Janeiro and the extent to which the sport mega-event attempted to intervene. We argue that, despite the enormous investment and façade of newly militarized host communities, insecurities remained, and “security” as a practice failed to be guaranteed. In order to discuss the particularities of mega-event securities in Rio de Janeiro, it is important to offer an abbreviated overview of the different technologies, policies, and personnel that frame geographies of in/security in Rio de Janeiro—to which a complex assemblage of military strategies, surveillance technologies, favela pacification, and armed milícias (militias) offer a unified impression (de Certeau 1984) of security yet mask lived and living realities of urban insecurity. For example, security preparations for the 2007 Pan/Parapan American Games, an event that initially sought to secure subsequent mega-event bids, involved Civil and Military Police violently invading Complexo do Alemão, resulting in the killing of 19 people. In October 2009, less than a month after Rio de Janeiro was named host of the 2016 Summer Olympic Games, a large-calibre weapon shot down a police helicopter one mile from the Maracanã football stadium. With stories of urban violence internationally spotlighted, Brazilian authorities made a public commitment to enhance state security. Specifically, the 2016 Olympic Bid Committee promised to resolve urban insecurities before 2012 and noted investments in personnel, equipment, and technologies as priorities. Rodrigo Pimentel, former police captain for the Military Police in Rio de Janeiro, stated in an interview to the New York Times: “Now the cost of security will be very high, but it will be worth it. Let’s be honest, one more helicopter that falls down in Rio de Janeiro or another slum invasion could seriously raise the chances of the Olympics and World Cup pulling out of Brazil” (as cited by Barrionuevo 2009). Authorities also installed biometric and genomic technologies: such as an integrated camera circuit controlled by the Integrated Command and Control Centre (CICC). The Israeli firm International Security and Defense Systems (ISDS), contracted for the 2007 Pan/Parapan Games, allegedly signed an additional BRL 2.2 billion contract to coordinate future event securities (Desai and Sykes 2019). The imperious instalment of networked surveillance technologies, personnel, and international expertise was combined with strategies framed as more peaceful or friendlier, such as the widely criticized UPP (Pacifying Police Unit/Programme). The installation of pacification police targeted urban geographies historically occupied and maintained by Afro-Brazilian people (Ystanes and Salem 2020) and combined a racialized discourse of anti-Blackness with a public health discourse of hygienization to rationalize the eviction of people deemed contagious, diseased, and/or harmful to social order. Hygienization and pacification are entrenched in the colonial logic of Black disposability in Rio de Janeiro (Alves 2018) and render the widespread displacement of Black communities from the downtown/tourist core as a predictable outcome of mega-event reform.

Understanding practices of mega-event security in Rio de Janeiro also requires understanding the work of milícias (militias). Historically, militias emerged to provide a temporary fix to violent inequalities, structural insecurities, and the imminent threat of drug-related violence in communities without adequate investment. In 2006, ahead of the 2007 Pan/Parapan American Games, the Mayor of Rio de Janeiro, Cesar Maia, enthusiastically embraced militias as a form of “community self-defence” thought to prevent the spontaneous violence associated with drug trafficking gangs (namely Comando Vermelho, Terceiro Comando Puro, and Amigo dos Amigos) and maintaining relative calm across host communities (Benmergui and Gonçalves 2019, p. 381). Yet militias’ modus operandi involves the coercive control of territories and communities by an illegally armed group that communicates the notion that it is the only faction capable of citizen safety and protection (Cano 2013). The ability of militias to act violently with degrees of impunity is due to the integral involvement of elected and appointed authorities in their leadership. Indeed, Marielle Franco, the first Black, feminist, bisexual favela resident elected to Rio de Janeiro City Council (murdered in March 2018 in an attack linked to militias) documented the presence of militias in 171 communities and detailed their intricate connection with state authorities. Her investigation led to the indictment of 218 people—67 were military police, 8 civil policemen, 5 city councilmen, some were linked to other public agencies, and another 879 were notified without sufficient evidence for an indictment (Misse 2018, p. 75). Of the 171 communities, 119 never belonged to a drug faction and, thus, complicated the notion that militias occupy communities to combat drug-related violence. The scholarly work and political advocacy of Marielle Franco illuminates the intricate involvement of Brazilian state and municipal authorities throughout Rio de Janeiro and their consolidation of a parallel state structure and alternative rule of law within urban peripheries.

Critical urban scholarship, not necessarily invested in analyses of the sport mega-event, is attuned to the various systems and practices of governance that construct everyday in/securities. With unreliable state involvement and rule of law, criminal gangs assume multifaceted roles beyond mere involvement in illicit trade. Drawing from insights of critical geographer Jennifer Tucker (2023) and her exploration of outlaw capital, these groups are enlisted to address grievances of everyday life—they are called upon to right the wrongs—thereby garnering tolerance and, at times, even reverence. Moreover, by offering assistance and aid amid sporadic and multiple crises, they acquire the perception of “good” or “benign” bandits. While studies on sport mega-event securities acknowledge this complex terrain, the emphasis on totalizing plans and strategies can only superficially account for, at best, or entirely obscure the synchronicities that unfold at the local level. With special attention focused on Rio de Janeiro, Duignan et al. (2022, p. 72) noted the following:

There are multiple Rios, and it is dangerous to summarize the complexity of such a complex city, but Rio is associated with social inequality and inner-city conflict. It is a polarized city, where decadent lifestyles coexist with destitution (Gaffney 2015), a so-called splintering urbanism (Graham and Marvin 2002) where tourist-zones and local-neighbourhoods are juxtaposed and clearly separated.

We aim to highlight some of the various systems and practices of governance in Rio de Janeiro, challenging dominant discourses that justify heavy investments in “official” security forces, by revealing persistent insecurities. Overall, we argue that the security strategies implemented in mega-event Rio de Janeiro not only failed to guarantee security but also masked deeper practices of governance and power dynamics within and across host communities. In analyses of mega-event securities, there is a need to understand the “multiple Rios” which converge to create in/securities. In the next section, we prioritize the voices, experiences, and perspectives of sex workers, so often forced to contest and negotiate state practices of security, used to militate against so-called criminal or “abject” populations, and more recently converging with religious and feminist forces to “rescue” women.

5. Managing in/Securities in Mega-Event Rio de Janeiro

Whilst global in nature, (mega-event) securities designed to secure tourism and associated capital are constituted and consolidated at a highly localized level. As Simone (2004, p. 407) insists, the “incessantly flexible, mobile and provisional” human activities that contour urban infrastructure—the delicate dance to secure Rio de Janeiro for an international audience—were reliant upon host communities and their interaction with newly installed urban hardware (e.g., networked CCTV, video surveillance, etc.), as well as the existent plurality of social order (Arias and Barnes 2016). The contested nature of (mega-event) securities in Rio de Janeiro, on the one hand, depended upon the “aesthetic of security” (Caldeira 1996, 2000) that is familiar across FIFA/IOC host cities: pacified favela or “slum” communities fortified for tourist consumption, spectacular militarism (see Figure 1, Copacabana Palace, the official home of FIFA/Olympic executive), and the introduction of so-called rescue industries for women and children (Mitchell 2022). On the other hand, it involved the routine work of women who are made to navigate local authorities that also benefit from their labor. Their realities reflect a framework of securitization that is manufactured and realized in the street through women and their bodies—not political, legislative, or even technologic processes.

Figure 1.

Copacabana Palace.

Urban insecurities were a regular and mundane topic of conversation amongst sex workers. Indeed, this was seen as a condition of their labor and precarious status within Rio de Janeiro, yet this seldom resulted in the widespread erasure of sexual commerce.

Everyone wanted to end prostitution in Copacabana. But they need to understand that will never happen. When they close one bar, another one opens up. They close one, the girls move to another. If they close it, the girls will go somewhere else. They’re never going to leave. They’ll never get rid of the prostitutes—because they’ll never end the demand.

Todo mundo queria acabar com a prostituição em Copacabana. Mas eles precisam entender que isso nunca vai acontecer. Quando fecham um bar, outro abre. Fecham um, as meninas se mudam para outro. Se fecharem ele, as meninas vão para outro lugar. Elas nunca vão embora. Eles nunca vão se livrar das prostitutas–porque eles nunca vão acabar com a demanda.(author translated, personal communication, 22 September 2016)

Hubbard and Wilkinson (2014, p. 610) argue that sex work is inherently important to the touristic offer of all global cities, albeit this is seldom acknowledged in official urban redevelopment policy or rhetoric. With the sport mega-event, there is still interest in the maintenance of sexual economies, even if visibilities are transformed. The closure of a well-known beachfront restaurant in Copacabana that was famous for prostitution, Balcony Bar, reinforced this account. With the restaurant ordered to close, due to an allegation of forced sexual exploitation of women and children which remained unfounded, women relocated to the adjacent piazza and harnessed the still-active wireless internet to contact clientele. The ideological debate on prostitution (and the resultant lack of clear legislation) benefitted women and their establishment of cross-class solidarities (see Blanchette and da Silva 2011). The synchronicities required to orchestrate popular economies (see especially Gago 2017) are reflective of the false division between formal and informal. One woman who worked in privé nearest Porto Maravilha explicated as follows:

Did you ever think this establishment would be closed by the police?

Never. Because when you work in these places, you see that there is a bribe paid to the police. As soon as you don’t pay then it could happen, but the owner/Madame would never want to risk that, especially at a time when there is more money to be made. So, there was no risk of that.

Você já pensou que esse estabelecimento seria fechado pela polícia?

Nunca. Porque quando você trabalha nesses lugares, você vê que tem uma propina sendo paga pra polícia. Assim que você não pagar, isso pode acontecer, mas o proprietário/Madame nunca ia querer arriscar isso, principalmente num momento em que tem mais dinheiro pra ser ganhado. Então, não havia risco disso.(author translated, personal communication, 4 July 2014)

Another woman traveled from São Paulo to work in the tourist-oriented South Zone of Rio de Janeiro for the duration of the 2014 FIFA World Cup and 2016 Summer Olympic Games. With her knowledge of Brazilian cities, she provided further insight into the intimate and complex network between government authorities, law enforcement, militia, and other criminal entities that maintained the businesses she traveled to for work:

Let me tell you something about these supposedly illegal clubs. Every day there are judges, prosecutors, police officers, sheriffs, magistrates, etc. in there. Most (sex) businesses would never work if it were not for those men. They create a kind of buffer. They make it work. So, we don’t really fear the cops. No one will arrest you … We work inside with security. It is exactly like I told you: For a business to function, for any brothel to work, there must be this buffer.

Deixe-me dizer-lhe algo sobre esses clubes supostamente ilegais. Todos os dias têm juízes, promotores, policiais, delegados, magistrados, etc. lá dentro. A maioria dos negócios (sexuais) nunca funcionaria se não fossem esses homens. Eles criam uma espécie de proteção. Eles fazem funcionar. Então, a gente não tem muito medo dos policiais. Ninguém vai te prender… Trabalhamos lá dentro com segurança. É exatamente como eu te disse: para um negócio funcionar, para qualquer bordel funcionar, tem que haver essa proteção.(author translated, personal communication, 4 July 2014)

In conversation, she expertly illustrates the work of Alba Zaluar (2000) and José Cláudio Souza Alves (1998, 2020) with respect to organized crime, which crosses all social classes and is integrated—however perversely—with organized “legal” business. Zaluar (2000, p. 654) argues poignantly that organized crime cannot survive without institutional support from state authorities. The arbitrariness of prostitution legislation in Brazil opened possibilities for people to create a separate realm for arbitration (see also Zaluar and Conceição 2007). This buffer—as described by a project participant—tightly comprised elected and appointed authorities and afforded women some assurance. José Cláudio Souza Alves (1998, 2020) details the mutually beneficial connection between organized crime and state agencies wherein access to registries of publicly owned land was shared with militia to request title. Through extensive fieldwork within communities in Rio de Janeiro, Alves narrates the institutional supports that made possible the “militia tax” added on properties (approximately BRL 1000) listed for sale. Land irregularly tallied, measured, and registered added opportunities for men to practice their own entrepreneurialism.

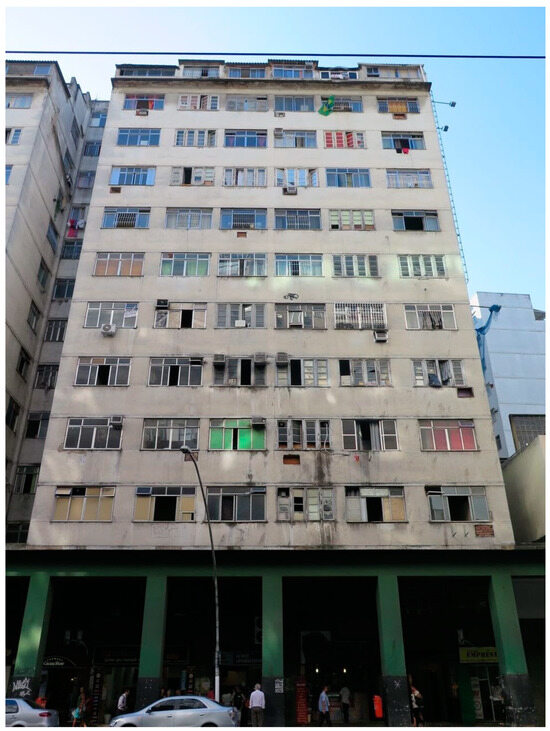

Similarly, across from the newly privatized port area of Rio de Janeiro sat the sister municipality of Niterói, which served as the backdrop for Porto Maravilha and de facto destination for much of the event-related tourist traffic. Event-prompted development in downtown Rio de Janeiro rippled across the Guanabara Bay to stimulate an urban facelift in the adjacent port area here (de Queiroz Ribeiro and Corrêa 2017). One particular site of contention—threatened due to heightened real estate speculation—was an 11-storey condominium above a bank (the Caixa) that served as the largest sex zone in the area ever since it emerged in the aftermath of the second dictatorship (1964–1985) (Figure 2). Women worked in the Caixa semi-autonomously, backed by militia; some pocketed BRL 8000/month (approximately USD 4000), but most made well over minimum wage (BRL 880/month or BRL 228/month). As one noted, “In a week you could make R$2000 or R$1500 [approx. USD$500 or $390]. It was good there, really” (personal communication, 24 September 2016). Slightly melancholic, she seemed keen to elaborate. We sat in silence a minute more, and then she resumed speaking:

Figure 2.

The Caixa.

Now I’m going to tell you this: the Caixa Econômica [as it was commonly referred] was different because of the security we had. The music wasn’t too loud and there were three security guards on every floor. If anything happened, the guy would have to pass them. If something happened with a girl, they would beat him up and throw him down the stairs. And there was no way he could rip you off because he had to pay to go up to the room, so the money was already there. And during the sessions, the manager would go there and knock on the door to ask if everything was cool.

Agora vou te dizer o seguinte: a Caixa Econômica [como era comumente referida] era diferente por causa da segurança que a gente tinha. A música não era muito alta e tinha três seguranças em cada andar. Se acontecesse alguma coisa, o cara ia ter que passar por eles. Se algo acontecesse com uma menina, eles espancavam ele e jogavam ele escada abaixo. E não tinha como ele te passar pra trás porque ele tinha que pagar pra ir até o quarto, então o dinheiro já estava lá. E durante as sessões, o gerente ia lá e batia na porta pra perguntar se estava tudo legal.(author translated, personal communication, 24 September 2016)

In addition to hired security, women explained that they also maintained a collegial relationship with the nearby Civil Police precinct. Some policemen acted as regular clientele at the Caixa Econômica, while the division collected a generous monthly stipend—a standard arrangement for businesses marked with irregularities (further discussed below). With the launch of Olympic militarism/urbanism, a new territorial war ensued between the militias and newly empowered state agencies (see especially Murray 2014), which caused the violent eviction at the Caixa Econômica. Even though the eviction was marred by illegalities and brute violence, media focused on the women and their supposed (im)moralities. Centred yet neglected, voiceless yet constructed as a threat, the official narrative rationalized the eviction of women reliant upon sex work and typified the culture of machismo moral impunity. The media coverage and broader public reaction, although not the focus of our analysis, validated the action and celebrated the infiltration of a supposed crime ring, obscuring the intricate involvement of state authorities in such businesses.

At home, as with at work, women routinely spoke of the need to invent and invest in their own security strategies—despite the massive state investment in event securities. To do so, women maintained their own network of well-connected businessmen—an allegiance that was appropriately compensated. Most referenced was the arrangement with Civil Police, who routinely collected an acerto (settlement) or bribe.4 One worker/manager of a privé in Centro/downtown explained as follows:

The house I work in, every house I have ever worked in, pays the police to stay open. If not, for sure, they would be closed. Everyone coughs up the money for police to leave them alone. Not for protection. Just to stay away. The government will never help us. And that is fine. But if we could have some kind of security … Not like a private-paid bodyguard [which is technically illegal under pimping laws] but something else. Because we encounter violence at work—whenever you deny someone, they occasionally demand more. Men feel entitled because they are paying for a service. So, we definitely encounter violence, but we can never report it. If I said, “Look, this is happening at my work, and I would like to file a BO [Boletim de Ocorrência or police report]”, and then say it happened at a brothel, no one is going to care. They will laugh and tell me to deal with it or say, “Sorry sweetheart, I am busy.” Mock us hard-core, you understand? So, there is no security even though we pay bribes. All that money is just a provision. Money so that we will not be shutdown. But if anything happens, no way they would help.

A casa que eu trabalho, todas as casas que eu já trabalhei, pagam a polícia pra ficarem abertas. Senão, com certeza, iam estar fechados. Todo mundo dá dinheiro pra polícia deixar eles em paz. Não pra proteção. Só para ficar longe. O governo nunca vai nos ajudar. E tudo bem. Mas se a gente pudesse ter algum tipo de segurança… Não como um guarda-costas pago por particulares [o que é tecnicamente ilegal sob as leis do lenocínio], mas outra coisa. Porque a gente se depara com a violência no trabalho—sempre que você nega alguém, eles às vezes exigem mais. Os homens se sentem no direito porque estão pagando por um serviço. Então, definitivamente, nos deparamos com a violência, mas nunca podemos denunciar. Se eu disser: “Olha, isso está acontecendo no meu trabalho, e eu gostaria de registrar um BO [Boletim de Ocorrência ou Boletim de Ocorrência]”, e depois dizer que aconteceu em um bordel, ninguém vai se importar. Eles vão rir e me falar pra eu me virar com isso ou dizer: “Desculpe, querida, estou ocupado”. Zomba da gente pra caramba, entendeu? Então, não há segurança mesmo com a gente pagando propina. Todo esse dinheiro é apenas uma precaução. Dinheiro pra que a gente não seja fechado. Mas se algo acontecer, de forma alguma eles ajudariam.(author translated, personal communication, 10 January 2017)

On one afternoon, a plain-clothed policeman suddenly appeared in the brothel amid an interview. The man showed little apprehension as he requested to see the manager as though he were a regular client. The manager of the business interrupted our interview to explain:

Excuse me, did you see who came? That man came to collect. He came to collect. I told you it would be today. There’s nowhere to run. Either you do it or you don’t, and if you don’t do it, you don’t work. I mean, this is not a super fancy establishment. I would be ashamed to knock on the door if I were a police officer—to collect money from a place that is so small-time. Such small fish. I would be embarrassed. But they have no shame. And I doubt I can even blame them now. It is a long time for someone to not be paid their salary, right. So now they want to double the bribe, but I refuse. Sometimes they come at me with, “Ah, we have to change this or that” but I never indulge them.

Desculpa, você viu quem veio? Aquele homem veio cobrar. Ele veio pra cobrar. Eu falei que seria hoje. Não tem para onde correr. Ou você faz ou não faz, e se você não faz, você não trabalha. Quero dizer, este não é um estabelecimento super chique. Eu teria vergonha de bater na porta se fosse policial—de cobrar dinheiro em um lugar que é tão pequeno. Peixes tão pequenos. Eu teria vergonha. Mas eles não têm vergonha. E duvido que eu possa até culpar eles agora. É muito tempo pra alguém não receber seu salário, né. Então, agora eles querem dobrar a propina, mas eu me recuso. Às vezes eles vêm para mim com um “Ah, a gente tem que mudar isso ou aquilo”, mas eu nunca dou bola pra eles.(author translated, personal communication, 10 January 2017)

Such an arrangement with local authorities is possible due to the ambiguous nature of prostitution legislation in Brazil.5 One-month prior to the 2016 Olympic event, several policemen organized a strike in Galeão International Airport with a sign that read, “Welcome to Hell. Police and firefighters don’t get paid; whoever comes to Rio de Janeiro will not be safe” (cited in Mohan 2016). At the time, women speculated that the acerto [bribe] subsidized salaries halted amid the 2016 recession. Despite their payment to local authorities, women still received little direct benefit. As one woman explained: “Look, if men refuse to pay, I call the police. And the police resolve the situation but keep half the money” (personal communication, 14 October 2016). Another woman, newer to the profession, added, “Our money is their money too, and money makes the world go around! Tax us, and then take our bribe. We always have to pay” (personal communication, 15 March 2017). This echoes the ethnographic work of Cabezas (2009) in Cuba and the Dominican Republic which found that state authorities benefitted from the coercive capabilities of law within and around sexual commerce. As with our work in Rio de Janeiro, Cabezas (2009) argued that legal ambiguities empower state authorities to demand financial compensation or threaten violence with impunity.

To the extent that law enforcement and the broader judiciary system is delegitimated, women are forced to also hire their own private security. Within the context of the 2014 FIFA World Cup and 2016 Olympic Games, economies of securitization thrived. “I made friends with a moto-taxi boy to act as my bodyguard. I would get money from the client, pretend to give it to him, and he would wait. I mean, I would pay him a little and he would wait a bit and then, leave. But the client thought he was there the whole time” (personal communication, 22 September 2016). Such a (panoptic) technique was thought to pre-emptively deter or dissuade violence—yet without guarantee:

On my first day in Copacabana, I made R$800. I was really happy, but that same day, a Brazilian guy took me to his apartment, locked the door, and threatened me with a knife. He said was going to have his way with me. And if I screamed, he would slit my throat. I had to protect myself. So, I smashed his head with a lamp. It is the law of survival. You learn it quick.

No meu primeiro dia em Copacabana, eu ganhei R$ 800. Fiquei muito feliz, mas naquele mesmo dia, um brasileiro me levou para o apartamento dele, trancou a porta e me ameaçou com uma faca. Ele disse que ia fazer o que quer comigo. E se eu gritasse, ele cortava minha garganta. Eu tinha que me proteger. Então, bati na cabeça dele com uma lâmpada. É a lei da sobrevivência. Você aprende rápido.(author translated, personal communication, 22 September 2016)

Women argued that the perceived threat of closure of local businesses (e.g., the Balcony Bar; the Caixa Econômica; Lido, an hourly hotel in Copacabana; and CasaNem, a shelter and political occupation for trans* and LGBTQ+ communities) never deterred or curbed demand but disrupted established orders and rendered feminized bodies more vulnerable:

Now that Balcony Bar is closed, it is more dangerous. There were security guys that respected us, never robbed us. But without that, we are all exposed, the girls and the clients. I even heard there were 12-year-old girls around here now. Before you had to show ID. Sure, maybe it was fake, but to work in a club, you needed to show an ID.

Agora que o Balcony Bar está fechado, é mais perigoso. Tinha seguranças que respeitavam a gente, nunca nos roubavam. Mas, sem isso, nós estamos todos expostos; as meninas e os clientes. Cheguei a ouvir que tinha meninas de 12 anos por aqui agora. Antes você tinha que mostrar a identidade. Claro, talvez fosse falso, mas para trabalhar em uma boate, você precisava mostrar a identidade.(author translated, personal communication, 22 June 2014)

[After a violent confrontation with a client in Copacabana, a woman explained] That is why I had problems, I had to go to his apartment. Before I always went to [Hotel] Lido, where they have a door guy, cameras in the corridors, and it is close to police. Now going to apartments, we end up being robbed, assaulted. Many times, really many times.

Por isso que eu tive problemas, eu tive que ir para o apartamento dele. Antes eu sempre ia ao [Hotel] Lido, onde tem um cara na porta, câmeras nos corredores, e é perto da polícia. Agora indo para apartamentos, a gente acaba sendo roubada, assaltada. Muitas vezes, sério, muitas vezes.(author translated, personal communication, 22 June 2014)

Rather than provide a “solution” to urban violence, women demonstrate that mega-event security disrupted the established order and created new opportunities for (armed) private personnel to profit from women and their precarity (see also Sampaio 2021). Critically aware of the performative nature of security—security as inherently contradicted and never guaranteed—women sought avenues through its inconsistencies and interstices:

To be honest, I would change nothing. If the law were different, there would be a brothel on every corner. I don’t drink, I don’t smoke, I don’t do drugs. All the money I make is to support my family, my daughters, you understand. Their school is R$800/month, each. If I made less money, they would never be able to study at a good school or have a decent health plan. If it were not for this job, no way could I afford this life. So, it is like that, unfortunately.

Pra ser sincera, eu não mudaria nada. Se a lei fosse diferente, teria um bordel em cada esquina. Eu não bebo, não fumo, não uso drogas. Todo o dinheiro que eu ganho é para sustentar minha família, minhas filhas, entendeu? A escola custa R$ 800/mês, cada uma. Se eu ganhasse menos dinheiro, elas nunca iam conseguir estudar em uma boa escola ou ter um plano de saúde decente. Se não fosse esse trabalho, de jeito nenhum eu poderia bancar essa vida. Então, é assim, infelizmente.(author translated, personal communication, 1 September 2016)

Indeed, from the perspective of women involved in this project, violence was routine and, in turn, necessitated thoughtful strategies, as risk was normalized. Dispossession and displacement were approached as mere occupational liabilities—and, for some, served to mitigate competition. Ironically, that unease, palpable across host communities, fueled an entire network of economies which promised security yet further perpetuated unease. The State of Rio de Janeiro, which declared a state of fiscal emergency in July 2016, allocated BRL 2.9 billion (USD 895 million) for mega-event security. This included the deployment of an additional 85,000 police personnel—nearly double that deployed at the 2012 London Olympics. Nevertheless, through the lived realities of women involved in sexual commerce—an occupation officially recognized by the Brazilian Ministry of Labor and Employment since 2002—the façade of security is indisputable. Despite the enormous investment in event security, women still required their own independently contracted projection, networks, and contingent safety measures.

6. Conclusions

Within this paper, we highlight how, despite enormous security investments and newly militarized/pacified communities, insecurities remained. Understanding security as a set of governance practices rather than a definitive outcome, we drew on Valverde (2011), arguing for the importance of more nuanced analyses of sport mega-event security, so as to better account for its contested nature, complexities, and unintended consequences. Our approach is one that highlights the need to take seriously the diverse impacts of mega-event securities on local communities, emphasizing and prioritizing research methods that offer long-term engagement with local actors. We use our ongoing research collaborations with sex worker and trans* rights groups in Rio de Janeiro to challenge prevailing narratives that justify enormous investments in “official” security forces by highlighting ongoing insecurities that persist despite these efforts. To do so, we offer a discussion of security practices that centres the voices, experiences, and perspectives of sex workers to demonstrate the ways in which mega-investments in event securities actually reshaped rather than eliminated host insecurities.

Through this collaborative and longitudinal approach, we reveal dialectics of “security” that, on the one hand, create a sanitized image of fortified favelas and militarized public spaces for international consumption and, on the other hand, create new or relaunch familiar security risks, particularly for sex workers. Empirical evidence outlines some of the ways that sex workers navigate the ambiguous legal landscape surrounding their profession, highlighting the strategies needed to maintain security amidst fluctuating enforcement and societal attitudes, as well as the deeply embedded nature of sex work with the social reproduction of cities. Indeed, closures and spatial displacements disrupted established safety measures, shifting (without eliminating) geographies of sex work that necessitated new opportunities for partnered activities and networks. There remains a need—in different contexts—to engage with groups that are often made the target of security practices in order to better understand sources and causes of insecurity in host cities and create security practices that respond accordingly. Ultimately, the insights drawn from this paper are suggestive of a shift in academic focus on the securitization of sport mega-events from a totalising rhetoric (Muller 2015) towards an exploration of the localized and contested nature of security.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.L., M.S. and P.H.; methodology, M.S., A.D.L. and P.H.; investigation, A.D.L.; formal analysis, A.D.L., M.S. and P.H.; resources, M.S.; original draft preparation, A.D.L., M.S. and P.H.; writing, reviewing and editing, A.D.L., M.S. and P.H.; funding acquisition and project administration, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), grant number ES/N018656/1; and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), grant number 767-2012-2111. The APC was funded by Bournemouth University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the University of Toronto (ID: 29538, 12 March 2013) and the Ethics Review Committee at Bournemouth University (ID: 12427, 10 August 2016). In line with ESRC guidance on international collaboration, ethical approval was also obtained via the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (Case: 55633816-8-0000-5699, 1 July 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

As per ethical approval, informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Full datasets are available at UK Data Service. These data are safeguarded and require permission from the data owner (Silk).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of participants to this work, as well as colleagues at the Prostitution Policy Watch at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, namely Thaddeus Blanchette, Thayane Brêtas, Ana Paula da Silva, Laura Murray, Gregory C. Mitchell, and Soraya Silveira Simões. Special thank you also to Caroline Fusco, Carly Fuller, Benton Oliver, Daisy Ueda, João Gabriel Rabello Sodré, and Yaa Sarpong.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | This paper draws on datasets gathered as part of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC)-funded project “Sex Work in the Context of Mega Events” (ES/N018656/1) and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) grant (767-2012-2111). |

| 2 | For a more comprehensive account of the methodologies deployed across these studies, we direct the reader to De Lisio and Fusco (2019), De Lisio et al. (2017), and the report from the ESRC funded project (De Lisio et al. 2019a; available here: https://www.bournemouth.ac.uk/sites/default/files/asset/document/BU-01%20Sex%20Report%205_1.pdf). (accessed 25 May 2024). |

| 3 | In line with UKRO funder requirements, the full datasets are available under restricted access at the UK Data Archive. |

| 4 | Since 1831, the police in Brazil have been divided into a civil and military force—which usually compete—with progressive dominance afforded to the militarized force in street patrol. The 1988 democratic constitution identified civil police as responsible for judiciary and administrative activities and the military police for ostensive and uniformed patrol, serving as a reserve auxiliary force to the army that is subordinate to state authorities (Caldeira 2000, pp. 146–50). |

| 5 | Legislation related to prostitution in Brazil is notoriously vague: simultaneously abolitionist, regulationist, and prohibitionist. Through international treaties, Brazil is committed to the abolition or elimination of prostitution. Brazilian law has maintained this commitment via the criminalization of third parties, the establishment of certain businesses, and the recruitment of people into the profession. However, law in Brazil has never criminalized the sale of sex. The consequence is that those involved in sexual commerce are locally regulated via municipal authorities and law enforcement, who decide to whom the vaguely worded legislation is applied. Historically, those able to allocate a portion of their salaries to police either legally through a licensing agreement or illegally through a bribery system avoid the legitimate or extrajudicial violence (see also Santos et al. 2020). |

References

- Alves, Jaime Amparo. 2018. The Anti-Black City: Police Terror and Black Urban Life in Brazil. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, José Cláudio Souza. 1998. Baixada Fluminense: A Violência na Construção do Poder. Doctoral dissertation, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, José Cláudio Souza. 2020. Dos barões ao extermínio: Uma história da violência na Baixada Fluminense. Rio de Janeiro: Consequência. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, Enrique Desmond, and Nicholas Barnes. 2016. Crime and plural orders in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Current Sociology 65: 448–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, Michael, and Kevin Young. 2012. Shadowed by the corpse of war: Sport spectacles and the spirit of terrorism. International Review for the Sociology of Sport 47: 286–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrionuevo, Alexei. 2009. Violence in the Newest Olympic City Rattles Brazil. New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/21/world/americas/21rio.html (accessed on 20 October 2009).

- Beck, Ulrich. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. New York: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Benmergui, Leandro, and Rafael Soares Gonçalves. 2019. Urbanismo Miliciano in Rio de Janeiro: Rio de Janeiro’s poor communities face increasing vulnerability as armed groups expand control of entire neighborhoods, operating illicit businesses from protection rackets to real estate, with dire consequences for local residents living under a violent parallel state. NACLA Report on the Americas 51: 379–85. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchette, Thaddeus G., and Ana Paula da Silva. 2011. Prostitution in Contemporary Rio de Janeiro. In Policing Pleasure: Sex Work, Policy, and the State in Global Perspective. Edited by Susan Dewey and Patty Kelley. New York: New York University Press, pp. 13–145. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, Philip, and Kevin D. Haggerty. 2009. Spectacular Security: Mega-Events and the Security Complex. International Political Sociology 3: 257–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas, Amalia L. 2009. Economies of Desire: Sex and Tourism in Cuba and the Dominican Republic. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira, Teresa P. R. 1996. Fortified Enclaves: The New Urban Segregation. Public Culture 8: 303–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, Teresa P. R. 2000. City of Walls: Crime, Segregation, and Citizenship in São Paulo. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cano, Ignacio. 2013. Violence and organized crime in Brazil: The case of “militias” in Rio de Janeiro. In Transnational Organized Crime: Analyses of a Global Challenge to Democracy. Edited by Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung and Regine Schönenberg. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, pp. 179–88. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelissen, Scarlett. 2011. Mega event securitisation in a Third World setting: Glocal processes and ramifications during the 2010 FIFA World Cup. Urban Studies 48: 3221–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Lisio, Amanda, and Caroline Fusco. 2019. Creative destruction: Zika and (alleged) Bodies of Contagion. Columbia Journal of Gender and Law 38: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- De Lisio, Amanda, and Joao Gabriel R. Sodre. 2019. FIFA/IOC-Sanctioned Development and the Imminence of Erotic Space. Bulletin of Latin American Research 38: 333–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lisio, Amanda, Michael Silk, Philip Hubbard, Thaddeus Blanchette, Laura Murray, Caroline Fusco, and Thayane Bretas. 2019a. Sex Work in the Context of the Sport Mega-Event. Bournemouth: Made. [Google Scholar]

- De Lisio, Amanda, Philip Hubbard, and Michael Silk. 2019b. Economies of (Alleged) Deviance: Sex Work and the Sport Mega-Event. Sexuality Research and Social Policy 16: 179–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lisio, Amanda, Thayane Bretas, Michael Silk, and Philip Hubbard. 2017. Sex work and the sport mega-event. In Mega Event Foot Prints: Past, Present & Future. Edited by Leonardo Jose Mataruna-Dos-Santos and Bianca Game Pena. Engenho: Rio de Janeiro, pp. 782–801. [Google Scholar]

- de Queiroz Ribeiro, Luiz, and Filipe Corrêa. 2017. Political Culture, Citizenship, and the Representation of the Urbs Without Civitas: The Metropolis of Rio de Janeiro. In Urban Transformations in Rio de Janeiro: Development, Segregation, and Governance. Edited by Luiz de Queiroz Ribeiro. Cham: Springer, pp. 231–56. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, Chandni, and Heather Sykes. 2019. An ‘Olympics without Apartheid’: Brazilian-Palestinian solidarity against Israeli securitisation. Race & Class 60: 27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Duignan, Michael B., and David McGillivray. 2019. Disorganised host community touristic event-spaces: Revealing Rio’s fault lines at the 2016 Olympic Games. Leisure Studies 38: 692–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duignan, Michael B., Ilaria Pappalepore, Andrew Smith, and Yvonne Ivanescu. 2022. Tourists’ experiences of mega-event cities: Rio’s Olympic ‘double bubbles’. Annals of Leisure Research 25: 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duignan, Michael B., Simon Down, and Danny O’Brien. 2020. Entrepreneurial leveraging in liminoid Olympic transit zones. Annals of Tourism Research 80: 102774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fussey, Pete, and Jon Coaffee. 2012. Balancing local and global security leitmotifs: Counter-terrorism and the spectacle of sporting mega-events. International Review for the Sociology of Sport 47: 268–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fussey, Pete, Jon Coaffee, and Dick Hobbs. 2011. Securing and Sustaining the Olympic City: Reconfiguring London for 2012 and Beyond, 1st ed. Abingdon: Taylor and Francis, p. xiii. [Google Scholar]

- Gago, Verónica. 2017. Neoliberalism from Below: Popular Pragmatics and Baroque Economies. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Giulianotti, Richard, and Francisco Klauser. 2010. Security Governance and Sport Mega-Events: Toward an Interdisciplinary Research Agenda. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 34: 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley, Martyn, and Paul Atkinson. 2019. Ethnography: Principles in Practice, 4th ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Horne, John. 2015. Sport mega-events: Three sites of contemporary political contestation. Sport in Society 20: 3280340. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, Phil, and Eleanor Wilkinson. 2014. “Welcoming the World”: Hospitality, Homonationalism, and the London 2012 Olympics. Antipode 47: 598–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manley, Andrew, and Michael Silk. 2014. Liquid London: Sporting spectacle, Britishness & ban-optic surveillance. Surveillance & Society 11: 360–76. [Google Scholar]

- Markula, Pirkko, and Michael Silk. 2011. Qualitative Research for Physical Culture. London: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Misse, Michel. 2018. Between death squads and drug dealers: Political merchandise, criminal subjection, and the social accumulation of violence in Rio de Janeiro. The Global South 12: 131–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Gregory. 2022. Panics without Borders: How Global Sporting Events Drive Myths about Sex Trafficking. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, Megha. 2016. Rio 2016: ‘Welcome to Hell’ Warn Police. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/blogs-trending-36653007 (accessed on 28 June 2016).

- Muller, Martin. 2015. The mega-event syndrome: Why so much goes wrong in mega-event planning and what to do about it. Journal of the American Planning Association 81: 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, Laura. 2014. Victim management and the politics of protection: Between “fazer direito” and “direitinho”. Revista Artemis 18: 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOlympicsLA. 2020. Examining the LA 1984 Olympic Legacy: Capitalism, Police Violence and Privatization. Available online: https://nolympicsla.com/2020/06/29/examining-the-la-1984-olympic-legacy-capitalism-police-violence-and-privatization/ (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Paton, Kirsteen, Gerry Mooney, and Kim McKee. 2012. Class, Citizenship and Regeneration: Glasgow and the Commonwealth Games 2014. Antipode 44: 105101578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauschinger, Dennis. 2020. The Permeable Olympic Fortress: Mega-Event Security as Camouflage in Rio de Janeiro. Conflict and Society 6: 108–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavoni, Andrea. 2015. Resistant legacies. Annals of Leisure Research 18: 470–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavoni, Andrea. 2017. Controlling Urban Events: Law, Ethics and the Material. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio, Antônio. 2021. Urban Resources and their Linkage to Political Agendas for Armed Groups in Cities. Journal of Illicit Economies and Development 2: 171–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, Betania, Indianarae Siqueira, Cristiane Oliveira, Laura Murray, Thaddeus Blanchette, Carolina Bonomi, Ana Paula da Silva, and Soraya Simões. 2020. Sex work, essential work: A historical and (Necro) political analysis of sex work in times of COVID-19 in Brazil. Social Sciences 10: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silk, Michael. 2010. Postcards from pigtown. Cultural Studies—Critical Methodologies 10: 143–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, AbdouMaliq. 2004. People as Infrastructure: Intersecting Fragments in Johannesburg. Public Culture 16: 407–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, Jennifer L. 2023. Outlaw Capital: Everyday Illegalities and the Making of Uneven Development. Athens: The University of Georgia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Valverde, Mariana. 2011. Questions of security: A framework for research. Theoretical Criminology 15: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, Chad. 2014. Surveillance, security and sporting mega events: Toward a research agenda on the organisation of security networks. Surveillance & Society 11: 392–404. [Google Scholar]

- Ystanes, Margit, and Tomas Salem. 2020. Introduction: Exceptionalism and Necropolitical Security Dynamics in Olympic Rio de Janeiro. Conflict and Society 6: 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaluar, Alba. 2000. Perverse Integration: Drug Trafficking and Youth in the ‘Favelas’ of Rio de Janeiro. Journal of International Affairs 53: 653–71. [Google Scholar]

- Zaluar, Alba, and Isabel Siqueira Conceição. 2007. Favelas sob o controle das Milícias no Rio de Janeiro. São Paulo em Perspectiva 21: 89–101. [Google Scholar]

- Zedner, Lucia. 2009. Security. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).