Abstract

Empowering women requires a multidimensional and holistic approach that encompasses the social, political, and economic aspects of women’s development. Economic empowerment is particularly crucial for achieving sustainable development in society. This is especially important in South Asia, where women’s poverty levels are high. Microfinancing for South Asian women expands their opportunities in public works, agriculture, finance, and other sectors, thereby accelerating economic growth and helping to mitigate the effects of current and future financial crises, especially at the household level. This study systematically examines evidence of the impact of microfinance initiatives on women in South Asian countries (SAARC countries) using 38 articles. It considers the effects on decision-making; economic gains, such as income, savings, and expenses; freedom and mobility; educational gains; and asset accumulation. The study also assesses the impact on non-financial outcomes like food security, health and nutrition, and social benefits. The results conclude that efficient and effective women’s microfinancing can bring significant benefits for women in the region.

1. Introduction

Women contribute to the economic growth and sustainable livelihoods for their families and communities. Microfinance, provision of financial services to the poor, especially for women in a sustainable manner help families to develop income generating activities and better cope with risk. Thus, empowering women through microfinance betters families and communities while also helping to deliver newfound respect, independence, and participation for women in their communities (ILO n.d.). According to the Microcredit Summit Campaign report in 2007, there were 93 million poor clients for microfinance and 85% (79 million) of these were women. According to World Development Report (2012), “Putting resources into poor women’s hands while promoting gender equality in the household and in society results in large development payoffs. Expanding women’s opportunities in public works, agriculture, finance, and other sectors accelerate economic growth, helping to mitigate the effects of current and future financial crises”. Gaonkar (2004) conceptualized the empowerment of women as a multidimensional and holistic approach, and it covers the social, political, and economic aspects of women’s development. The idea is supported by many other research outcomes as well (Kabeer 1999; Endeley 2001; Acharya and Ghimire 2005; Samanta 2009). Khursheed et al. (2021) highlight the transformative effects of microfinance, noting that it not only enhances women’s economic status but also fosters broader societal benefits.

Measuring empowerment presents significant challenges, as the definitions, objectives, and outcomes of such measurements can differ greatly across various cultural, social, economic, and political contexts (Uddin 2015). Thus, using microfinance for investment activities or productive purposes is important to make a change (Samanta 2009). According to Ali and Hatta (2012), empowerment depends on various factors, such as a members’ background (family background, educational background, self-awareness level, health consciousness, and so on), the nature of the loan (residing place of the members, the goal of the lending organization, like whether the organization works for women empowerment, improving the consumption level of its members or bringing about family well-being, the amount of the loans given and the utilization of the loans controlling of the loans, the spending authority of the loans, and the accountability and responsibility of repayment of the loans).

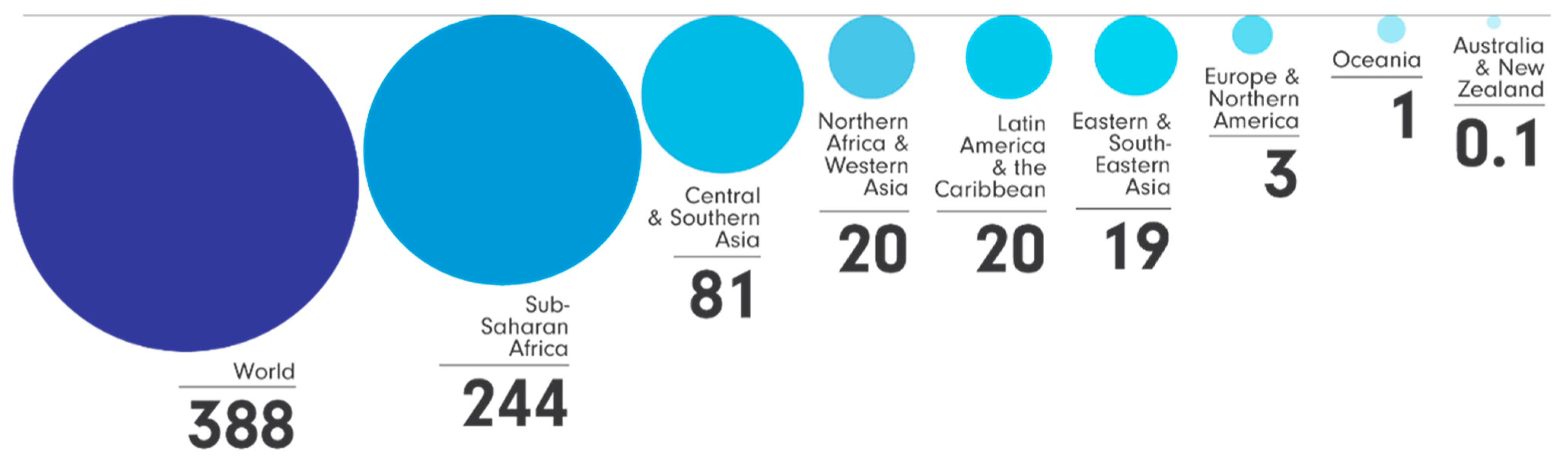

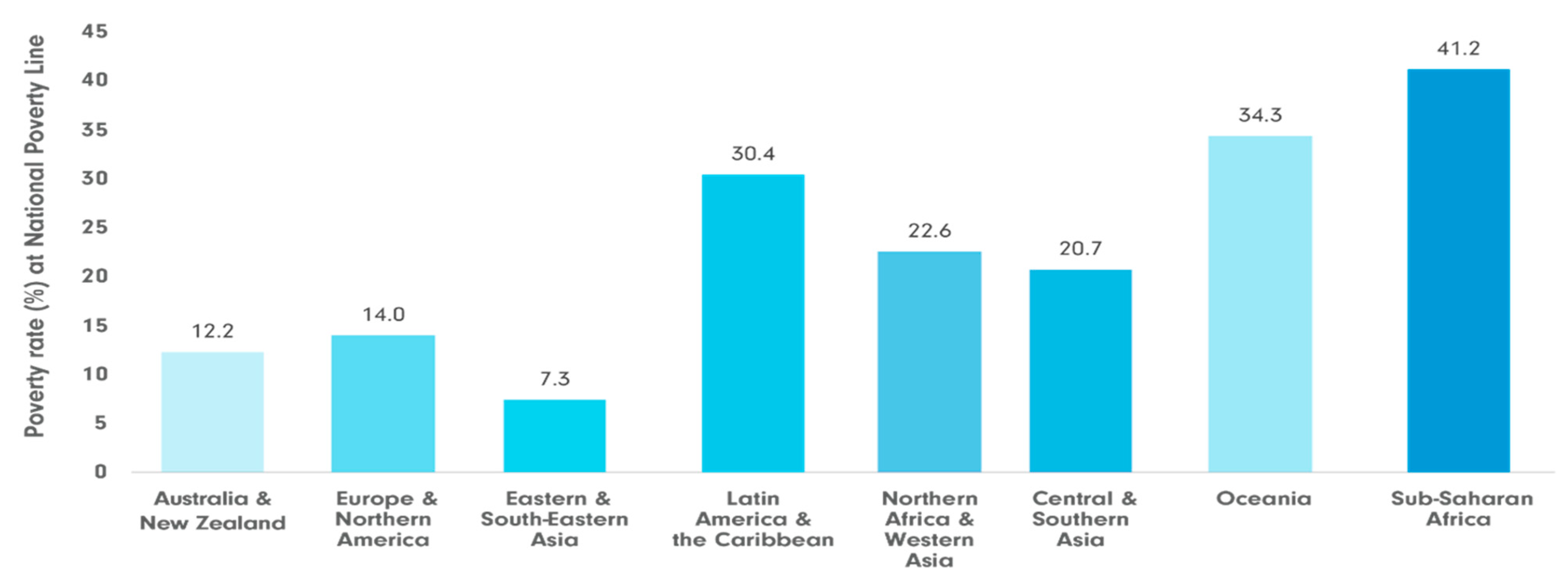

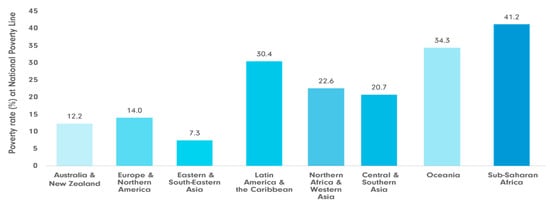

New projections of global poverty by UN Women, UNDP, and the Pardee Center for International Futures estimate that, globally, 388 million women and girls will be living in extreme poverty in 2022 (compared to 372 million men and boys). According to these new forecasts, 83.7% of the world’s extreme poor women and girls will live in just two regions: Sub-Saharan Africa (62.8%) and Central and South Asia (20.9%). The figure is 19% for eastern and southeastern Asia (Figure 1). Figure 2 shows the female poverty rate by region, indicating that Africa, Oceania, Latin America, and Asia have the highest rates.

Figure 1.

Female population living in extreme poverty, by region, 2022 (in millions). Source: UN Women, UNDP and Pardee Center for International Futures using the International Futures modeling platform (UN Women 2022).

Figure 2.

Female poverty rates by region, using national poverty line estimates, 2022 projections. Source: UN Women, UNDP, and Pardee Center for International Futures using the International Futures modeling platform (UN Women 2022).

Reducing poverty necessitates long-term efforts focused on reaching and serving the poor. This can be effectively achieved through the active and financially sustainable operations of microfinance institutions (MFIs). Numerous studies support the idea that providing credit to many active borrowers, especially women, can significantly reduce household poverty levels. Microfinancing offers small-scale financial support, such as loans, savings accounts, and insurance, to individuals who typically lack access to regular banking services, particularly in impoverished communities. The primary goal of microfinance is to assist those often excluded from traditional financial systems.

Women’s microfinancing specifically provides financial services, such as microcredit and microloans, tailored to women. These initiatives and programs aim to economically empower women by offering access to financial resources, training, and support for entrepreneurial activities. According to Cull et al. (2007), smaller loan sizes suggest that MFIs are targeting poorer customers, thereby contributing to a decline in poverty. The breadth of outreach, including the number of active borrowers and women borrowers, has also demonstrated a significant positive impact on poverty reduction (Hermes et al. 2009). Furthermore, MFIs that predominantly lend to groups rather than individuals tend to charge considerably lower interest rates, leading to higher outreach costs (Cull et al. 2008). This indicates that group lending not only increases outreach but also contributes to poverty reduction. Additionally, a study by Javid and Abrar (2015) shows that smaller loan sizes are associated with higher interest rates.

1.1. Understanding the Regional Context

South Asia, a sub-region of Asia, lies between the Himalaya Mountains in the north and the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal in the south. Stretching from the main part of the continent to the Indian Ocean, South Asia is bounded by the Indian Ocean, the Himalayas, and Afghanistan. The region comprises eight countries, including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Pakistan, Nepal, and the island nations of Sri Lanka and the Maldives. With a vast population of around 1.5 billion people, South Asia is known for its rich diversity, encompassing various ethnic and cultural groups. The region’s political entities have historical roots in its colonial past, predominantly under the influence of Great Britain.

As of 2023, Southern Asia has a population of approximately 2.01 billion, representing about 24.89% of the global population. The region has a population density of 303 people per square kilometer over a land area of 6,400,127 square kilometers. In 2021, the rural population was 1.23 billion, and the urban population was 672 million. Females accounted for 48.82% of the total population in 2021 (Ritchie et al. n.d.; World Bank). According to the World Bank’s Poverty and Shared Prosperity Report 2018, poverty is a significant challenge in South Asia, posing a substantial obstacle to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals.

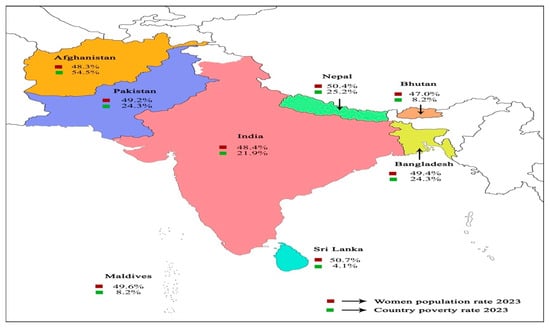

In Afghanistan, the total population stands at 45.08 million, with a slight majority of 51.7% being male and 48.3% female. The majority of Afghans reside in rural areas, with urban dwellers numbering around 10.55 million. Unfortunately, in 2020, nearly half of the population, about 49.4%, were living below the national poverty line, underscoring significant socio-economic hurdles (Asian Development Bank 2023).

In Bangladesh, where the population stands at 170.373 million, females constitute 49.4% of the total. Rural areas accommodate 61.05% of the population, contrasting with 39.0% in urban regions. This diversity highlights varying socio-economic conditions, evidenced by a national poverty rate of 18.7% (World Bank 2023). The female labor force participation (FLFP) rate stands at around 37%, based on 2016 data. Notably, FLFP experienced rapid growth in the early 2000s, with a notable 10 percentage point increase. This surge was fueled, in part, by the expansion of the ready-made-garment sector (RMG), creating nearly 3 million jobs during this period. However, women encounter numerous barriers hindering their workforce entry, especially in accessing quality employment opportunities beyond household responsibilities.

In Bhutan, with a total population of 784.9 thousand, 52.9% are male and 47.1% are female, with approximately 56.1% residing in rural areas. According to the World Bank, 12.4% of the population was below the national poverty line in 2022. Notably, poverty affects women more than men in Bhutan, with 1.1% of employed women living below the international poverty line compared to only 0.8% of men. This gender disparity is compounded by lower adult literacy rates among women (62.8%) compared to men (77.9%).

In 2023, India had a total population of 1.43 billion, with males constituting 51.95% (730 million) and females making up 48.05% (675 million) (Silver et al. 2023). As of 2021, the rural population was approximately 909 million. Notably, women account for 60% of unpaid family workers and 98% of those involved in domestic work (Acharya and Ghimire 2005). In 2023, women represented nearly 53% of employed individuals in India, marking an increase from the previous year. Since 2016, women have consistently formed a larger share of India’s employable talent compared to men. The female labor force participation rate also saw a significant rise in 2023, increasing by 4.7 percentage points and reaching a peak of 32.68%.

In the Maldives, 36% of the population resides in the capital, Male’, while the remainder is spread across 200 other islands (Sinha 2009). The total population is 569,422, with 49.6% being female and 50.4% male (Maldives Bureau of Statistics 2022). The overall poverty rate in 2022 was 8.2%. Women play a vital role in the social, economic, and political fabric of Maldivian life, influencing everything from family dynamics to political and private sector leadership. However, they face disproportionately high unemployment levels, with many considered economically inactive. Despite the tourism industry being a cornerstone of the economy, women make up only 7% of the tourism labor force, a trend that is similar across other key industries, including fish processing, tailoring, and agriculture, with Maldivian women engaging in management roles.

In 2023, Nepal’s population is estimated at 30.89 million, with 6.31 million living in urban areas and 23.72 million in rural regions. Women slightly outnumber men, with 15.15 million females compared to 14.91 million males. About 15% of the population, primarily in rural areas, falls below the poverty line (PopulationStat n.d.). Women’s labor force participation is less than half that of men, and they earn lower average monthly wages. Furthermore, women face significant barriers to accessing property, income, inheritance, and credit, which compounds their economic difficulties.

Pakistan’s population currently stands at 240.48 million, with 86.36 million residing in urban areas and the remainder in rural regions. In 2021, the rural population was reported to be 144.76 million. Females make up about 49.2% of the total population, with the majority living below the international poverty line (PopulationU.com n.d.). Women’s labor force participation in Pakistan is only 25%, compared to 85% for men. Despite making up nearly half of the population, women are significantly underrepresented in the workforce, holding only around 5% of high-level roles.

Sri Lanka’s population is 21.69 million, with 49.3% males and 50.7% females. In 2023, 19.2% of the population resided in urban centers, while 80.8% lived in rural areas (Trading Economics n.d.). Notably, 69% of the economically inactive population are women who face significant financial challenges (Bernard et al. 2016). The female labor force participation rate in Sri Lanka is around 36%, down from 41% in 2019.

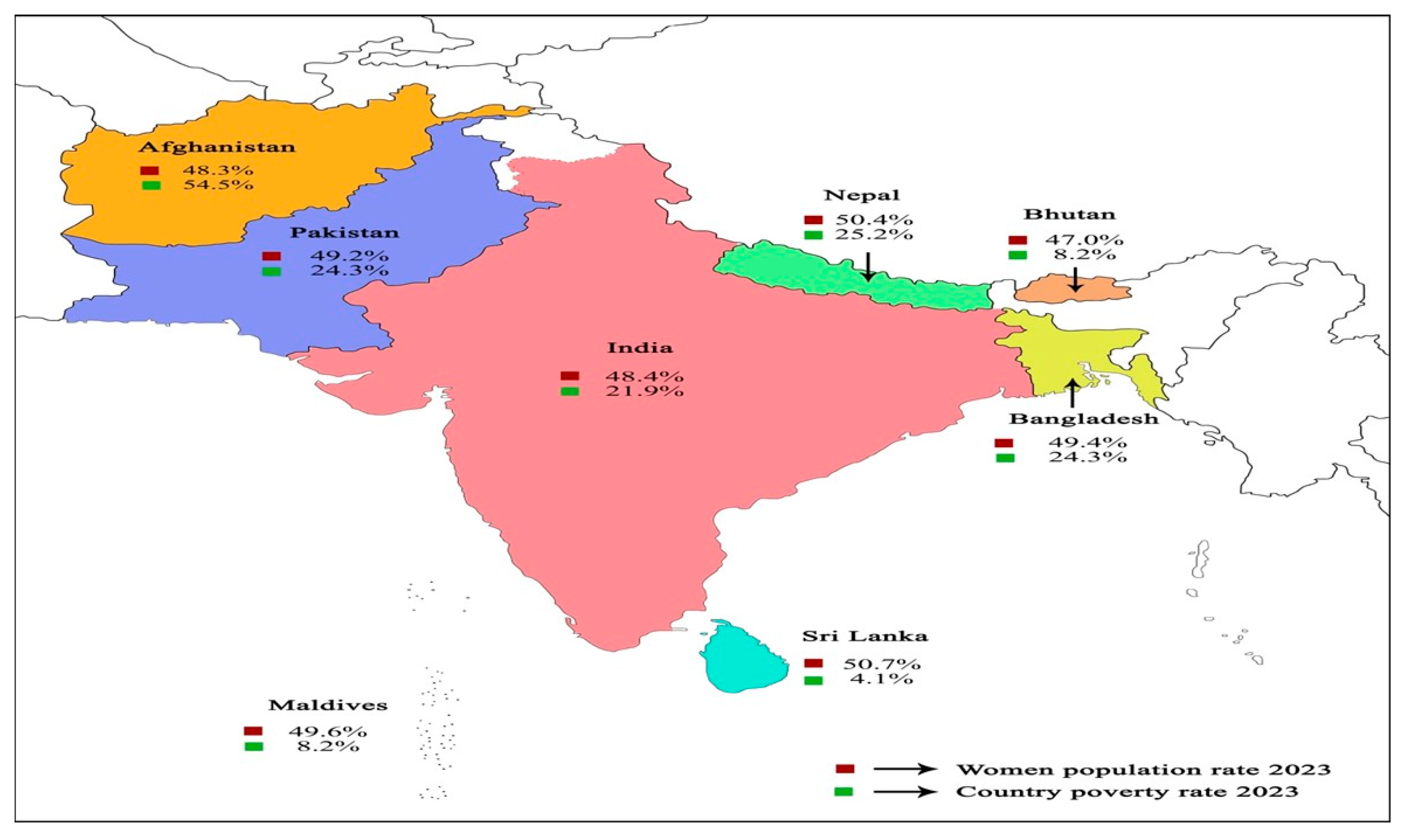

As per recent UN data, the poverty rate among women in South Asia is projected to rise in 2021 due to the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic. This trend emphasizes that, in the next decade, a higher number of women in the 25–34 age group are expected to experience increased poverty. The impact of the coronavirus pandemic may have led to as many as 47 million women and girls falling into extreme poverty by 2021 in South Asia (United Nations 2020). Figure 3 illustrates the female population in South Asia alongside the country poverty rate.

Figure 3.

Women population rate in South Asia, 2023.

1.2. Research Questions and Objectives

Many studies have examined microfinance in SAARC countries, including Afghanistan, Bhutan, Bangladesh, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka (Gupta and Sharma 2023; UN Women 2022; Samanta 2009; Hermes et al. 2009; Gaonkar 2004). While these studies generally focus on the impact of microfinance on the poor, there is a noticeable lack of specific information regarding its effects on women in South Asia. Despite significant microfinance activities targeting women in the region, the outcomes of these efforts are not well-documented or organized. This gap in data makes it challenging to accurately assess and discuss the economic benefits and drawbacks associated with women’s participation in microfinance initiatives.

Thus, the aim of this review study is to address the following research questions:

- What is the scale and participation of women in microfinance in South Asia?

- Does this involvement have a significant impact on empowering women in South Asia?

To achieve clarity on these research questions, the study has set the following objectives:

- Identify the significance of microcredit/microfinance programs especially for women in South Asia.

- Recognize the main achievements, potentials, and obstacles in women’s microfinancing programs.

- Develop a framework and discuss policy strategies to enhance the benefits of women’s microfinancing in South Asia.

The paper is divided into six sections. Section 2 outlines the theoretical insights of women microfinance. Section 3 outlines the review methodology. Section 4 details the review results and discussion for each country. Section 5 presents key findings and the conceptual framework. The final section provides the conclusions and limitations of the study.

2. Theoretical Insights on Women Microfinance

Microfinance has emerged as a critical instrument for advancing women’s economic and social empowerment, supported by various theoretical frameworks. The economic empowerment theory asserts that access to financial resources and economic opportunities enables individuals, especially women, to boost their income, stability, and overall well-being. Microfinance and similar initiatives provide the means for individuals to start or expand businesses, thus improving their economic standing (Morduch and Armendariz 2010). This economic progress translates into broader social empowerment, as microfinance facilitates women’s acquisition of social status and decision-making power within their communities (Schuler et al. 1998). The feminist economic theory highlights the need for economic systems to address and correct gender imbalances, advocating for increased economic participation and resource access for women as a path to greater equality and empowerment. It contends that microfinance disrupts traditional gender norms by providing marginalized women with opportunities for economic involvement previously out of reach (Elson 1999; Mayoux 2000). Additionally, the capability approach underscores how microfinance enhances women’s capabilities and agency, enabling them to make independent choices that enhance their quality of life (Sen 1999; Robeyns 2005). Frameworks focusing on financial access and social capital stress the significance of inclusive financial systems and the role of microfinance in fostering supportive networks among women (Sengupta and Aubuchon 2008). Collectively, these theoretical perspectives demonstrate that microfinance not only mitigates economic inequalities but also fosters social and personal empowerment for women, positioning it as a crucial element in development strategies. Narayan (n.d.) further emphasizes the relationship between empowerment and poverty reduction, offering insights into how microfinance influences women’s agency.

In South Asia, where poverty rates among women are particularly high, microfinancing is instrumental in addressing their financial needs. The region faces significant socio-economic challenges, including pervasive poverty and gender inequality, which affect women’s access to resources and opportunities (World Bank 2024). Microfinance initiatives in South Asia are vital for providing women with the capital necessary to start businesses and enhance their livelihoods, thereby contributing to poverty reduction and economic growth (Banerjee et al. 2015). Evidence indicates that microfinance programs targeting South Asian women lead to notable improvements in household income and educational outcomes for girls, underscoring the importance of such financial support. These programs also address systemic barriers faced by women, such as limited access to formal financial services and social exclusion, thereby playing a critical role in enhancing their economic empowerment and overall well-being (Duflo 2012).

3. Method of Review

The study follows the “systematic review” procedure recommended by Tranfield et al. (2003). This approach, extensively utilized in the microfinance literature by numerous researchers (Gupta and Sharma 2023; Hermes and Hudon 2018; Rasel and Win 2020), has provided a structured framework for this study. Researchers outline two key elements in the systematic review approach: the data collection method and the characteristics of the extracted data.

The search for relevant research has encompassed papers published between 2000 and 2022. To identify relevant research papers, clear inclusion and exclusion criteria were established. Selecting the appropriate databases was crucial for gathering accurate data. First, high-quality, peer-reviewed journals in Scopus and Web of Science were examined. Second, Google Scholar was utilized with an awareness of the proliferation of predatory journals, focusing on accepted and prominent journals from South Asian countries. Additionally, an effort was made to identify potential PhD dissertations and theses, primarily focusing on microfinancing in South Asia.

To include the relevant papers, the following criteria were established: The paper must provide information on microfinance or microcredit for women in South Asia. Additionally, it should demonstrate a clear relationship between microfinancing and women. Importantly, working papers, conference papers, and any papers not published in English were excluded.

To ensure comprehensive coverage for the period between 2000 and 2022, various search string combinations were employed to encompass Asian countries. The combinations included: “Microfinance for women in South Asia”, “Gender Diversity and Microfinance in South Asia”, “Women and Microfinance in South Asia”, “Women and microcredit”, and “Microcredit for women in South Asia”. Additionally, specific strings such as “Female microcredit/microfinance”, “Women microfinance for India”, “Women microfinance for Pakistan”, “Women microfinance for Sri Lanka”, “Women microfinance for Nepal”, “Women microfinance for Bangladesh”, “Women microfinance for Bhutan”, “Women microfinance for Maldives”, and “Women microfinance for Afghanistan” were utilized.

Using this comprehensive set of keywords and search strings, 102 articles were initially gathered. Of these, 44 articles were deemed relevant to the research objectives and included in the final analysis, while 58 articles were excluded. Despite having relevant titles and abstracts, a thorough reading of the full articles revealed a lack of substantial connection between microfinance and women, particularly in terms of social or financial impact. Some articles did not adequately address women in microfinance or failed to give sufficient attention to women in their analyses. After a meticulous review of these 44 articles, 38 were selected for the systematic review. These 38 articles explicitly discussed women in microfinance and related impacts, mostly from a qualitative perspective, as studies based on quantitative data are limited in terms of achievement. The selection of the final papers was based on the established inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Paper search and data collection procedure.

4. Review Results and Discussion

The results and discussion for each country are derived from the final selection of 38 papers obtained through the review process. Despite extensive efforts, the search did not yield any microfinance papers specifically focused on women for Afghanistan and Maldives. While microfinance programs exist in these countries, none were exclusively designed for women, making it challenging to align with the objectives of this review paper. As a result, the experiences of these two countries are not fully incorporated into the final conclusions. However, the study attempts to provide a broader perspective based on general microfinance and credit initiatives conducted in these countries.

4.1. Afghanistan

In Afghanistan, women encounter significant barriers to achieving fair participation in economic activities. A considerable number of households are led by females, and 13% of adult women are widows, making it challenging for them to sustain their livelihood without a male breadwinner. Female labor payments are typically only half or less than that of men, reflecting an economic disparity. Additionally, women in Afghanistan often have limited marketable skills and access to education, with an estimated literacy rate of only 21% (Lyby 2006). Ownership, control, and access to productive assets are frequently lacking for women, contributing to their economic challenges. Recognizing these hurdles, opportunities to access various forms of microfinance hold the potential to be a valuable step forward for women in Afghanistan (Lyby 2006).

Key microfinance institutions in Afghanistan, such as The First Microfinance Bank (FMFB-A), FINCA Afghanistan, OXUS Afghanistan, the Mutahid Development Finance Institute, The Afghanistan Rural Microcredit Program (ARMP), the Micro Finance Agency for Development (MoFAD), Parwaz, and Women for Women (WFW), play a vital role in providing financial services for economic development. However, evaluating their distinct impact on women microfinancing is challenging due to limited available data. The World Bank has actively contributed to various initiatives aimed at promoting women’s economic empowerment and rural development in Afghanistan. These projects include the Women’s Economic Empowerment Rural Development Project, Afghan Women’s Economic Empowerment, Afghanistan Access to Finance, as well as efforts focused on expanding microfinance outreach and improving sustainability (World Bank 2024). UN Women (2024) reports that the “Rebuilding the Women’s Movement in Afghanistan” program has partnered with 113 organizations across 19 provinces, helping at least 515 women secure paid employment. This initiative is supported by donors from Austria, Belgium, Canada, Norway, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland.

4.2. Bangladesh

In the past 10–20 years, Bangladesh has witnessed significant growth in microfinance programs (Chowdhury and Mukhopadhaya 2011). A pivotal moment in financial support for women occurred in the 1970s, when Professor Yunus initiated a pilot project to provide collateral-free microloans to impoverished women in Jobra, Bangladesh (Mia et al. 2019). Despite possessing entrepreneurial skills comparable to men, women in this Muslim-dominated country were often discouraged from participating in the labor force or engaging in entrepreneurial activities (Mia 2021).

Economic development in Bangladesh is propelled by two key drivers: financing through the banking system and the promotion of entrepreneurship. Islami Bank Bangladesh Limited (IBBL) plays a significant role in fostering Islamic microfinance and supporting women entrepreneurship through its Rural Development Scheme (RDS), initiated in 1995. Currently operational in 60 districts across the country, the scheme engages around 0.52 million group members (Mizanur Rahman and Ahmad 2004).

A research study conducted by Dalal et al. (2013) investigating the connection between microfinance program membership and intimate partner violence (IPV) among women in Bangladesh revealed interesting findings. For women with secondary or higher education and those belonging to the two wealthiest levels of the wealth index, microfinance program membership was associated with a twofold and threefold increase in exposure to IPV, respectively. Conversely, the least educated and poorest groups showed no discernible change in exposure to IPV linked to microfinance programs. Remarkably, educated women who actively participated in decision-making and maintained more equal family relationships with their spouses experienced an increased exposure to IPV through their membership in microfinance programs.

Contraceptive decision-making holds significant importance within overall household decision-making dynamics, as the consistent use of contraception has the potential to positively impact public health outcomes in Bangladesh. Microfinance participation by women has been identified as a catalyst for shared decision-making power between spouses, resulting in higher odds of joint decision-making (Murshid and Ely 2016). In Bangladesh, where approximately 61% of women report using contraceptives, understanding how contraceptive decision-making unfolds among married couples is crucial. Research indicates a significant association between microfinance participation, pregnancy planning, and contraceptive decision-making, highlighting the positive impact of microfinance on sexual health behavior, risk, and overall women’s empowerment (Murshid and Ely 2016). Interestingly, the study suggests that microfinance participation may lower the husband’s involvement in decision-making, potentially introducing an element of women’s empowerment or positively influencing women’s overall household decision-making (Murshid and Ely 2016).

The Rural Development Scheme (RDS) has exhibited impressive performance over an extended period, surpassing other prominent microfinance institutions (MFIs) operating in Bangladesh. Operating with an Islamic microfinance approach, RDS has effectively adopted a model reminiscent of the Grameen bank, incorporating an Islamic social perspective tailored to the Muslim society of Bangladesh. Similar to the Grameen bank model, RDS focuses on empowering women, with 80% of its clientele comprising economically disadvantaged women (Hassan and Saleem 2017). This strategic alignment underscores RDS’s commitment to leveraging Islamic microfinance principles to address poverty in Bangladesh, particularly by uplifting women economically.

In an investigation into the impact of microfinance on women’s control over resources in Bangladesh, Murshid (2018b) found that women participating in microfinance programs exhibited a higher prevalence of control over their resources compared to their non-participating counterparts. Aligning with Sherraden’s theory, the study suggests that microfinance participation enables women to develop “human capital” by gaining financial knowledge and acquiring the skills to manage a business and financial capital. This newfound capability empowers them to assert control over their resources, having learned the necessary skills through their engagement in microfinance activities. Additionally, the study emphasizes the significance of household wealth, urban residence (associated with progressive values), media exposure, older age, and higher education in enhancing women’s ability to control their resources. Notably, the findings indicate that empowerment, as defined in terms of household decision-making, autonomy, and justification of partner violence, is not strongly associated with microfinance participation among the representative sample of married women in Bangladesh (Murshid 2018a).

According to Zafarullah and Nawaz (2019), both employment and microfinance have had some positive impact on women’s empowerment, albeit with challenges, some of which stem from deep-seated tradition, religious conservatism, and family values, while others derive from a changing social environment that is often disquieting for women’s everyday life and mobility. With the creation of a more permissive environment, women will gain confidence in becoming more involved in community activities, create opportunities for them to take on leadership roles and enlarge their decisional influence in both political and strategic domains (Zafarullah and Nawaz 2019).

An increase in income and assets managed by women can boost their influence in household decisions and encourage their participation in off-farm and market-based activities. However, a rise in overall household income may limit women’s involvement due to socio-cultural barriers, reinforcing their traditional roles (Islam and Pakrashi 2020). When men control microfinance, it may lead to increased labor market activities for men, but not necessarily improve women’s participation. The impact on women’s labor supply depends on factors such as the substitution effect, income effect, and changes in women’s bargaining power within households (Islam and Pakrashi 2020). This study shows that having access to microfinance makes women follow traditional roles or contributes to more equality in households. The results suggest that families with microfinance are more inclined to try various types of jobs, especially those not related to farming.

The study by Shohel et al. (2021) reveals that microfinance programs in Bangladesh have not led to a shift in gender norms or financial empowerment for women. The control over women’s loans remained with men, reinforcing traditional patriarchal gender roles. The findings emphasize that, in Bangladesh, income-generation is perceived as a male responsibility, leading women to surrender control of their finances, including microfinance loans. The study highlights the persistence of patriarchal gender norms through socialization processes, hindering women’s agency in financial matters and participation in income-generating activities. Despite access to microfinance, women’s financial empowerment is constrained by ingrained gender norms, emphasizing the need for broader transformations in gender relations for substantive empowerment (Shohel et al. 2021).

Key microfinance institutions for women in Bangladesh include Grameen Bank, Microcredit Regulatory Authority, BRAC, and United Nations Capital Development Fund (Mia 2022). The World Bank’s projects, such as the Additional Credit for Second Poverty Alleviation Microfinance Project, underscore their crucial role in empowering individuals and communities across Bangladesh.

4.3. Bhutan

There is not much research on women’s microfinance in Bhutan, but the studies available highlight its importance. According to Yoezer (2015), giving rural women access to credit is crucial for boosting their economic empowerment. However, these women still face challenges from social, cultural, economic, and geographical factors. Many rural women (95%) primarily work on farms and engage in unpaid family labor. Gender stereotypes within families and communities limit women’s participation in economic activities and decision-making (Zangpo 2014), making it harder for them to access services like microfinancing. The low education level of women is also a problem (Jamtsho 2018). A study by Sariyev et al. (2020) found that women play a significant role in making decisions about household livelihoods and dietary quality.

In Bhutan, there are four main financial institutions involved in microfinance. These include two commercial banks, namely Bhutan National Bank (BNB) and the Bank of Bhutan (BOB), and two non-bank financial institutions, Bhutan Development Finance Corporation (BDFC) and the Royal Insurance Corporation of Bhutan (RICB) (Royal Monetary Authority of Bhutan 2020).

4.4. India

Microfinance programs, such as the Self-Help Bank Linkage Program (SBLP), have played a crucial role in promoting the economic empowerment of women in India. Multiple sources suggest that over 60 million Indian women benefit from microcredit programs, impacting as many as 300 million families (Swain and Wallentin 2017).

The development of underdeveloped sections has been a central focus of welfare states. In India, both government and non-government agencies have long been engaged in implementing various programs to achieve this objective. One notable initiative is the Self-Help Groups (SHGs), designed to foster the development and empowerment of underdeveloped segments of society, with a particular emphasis on women (Nayak and Panigrahi 2020). Funding agencies and government bodies are increasingly using women-led self-help groups (SHGs) as platforms for implementing development activities. The SHG is a small, economically homogeneous, affinity group of poor people that regularly saves money in a common fund to meet the emergency needs of its members by providing collateral-free and low-interest loans on terms decided by the group (Nayak 2015).

Participation in Self-Help Groups (SHGs) not only yields economic benefits but also contributes to the social and political empowerment of its members. Research findings indicate that increased involvement in SHGs results in heightened economic empowerment, offering employment opportunities, higher income, job stability, and enhanced entrepreneurial skills. Moreover, greater participation fosters social empowerment by enhancing decision-making abilities within households, providing access to healthcare, boosting self-confidence, improving self-esteem, enhancing communication skills, and facilitating transactions with banks and NGOs. Additionally, increased engagement in SHGs leads to greater political empowerment, manifesting in higher political participation and improved community mobilization. It is noteworthy that socio-economic status and the location of operation significantly influence the impact of participation levels on the empowerment of women (SHG members) (Nayak and Panigrahi 2020).

In rural India, a novel and quickly scalable community-based program was introduced, which integrated maternal health literacy delivered through women-only Self-Help Groups (SHGs) based on a microfinance model (Ahmad et al. 2021). This study shows that adding maternal health education to microfinance programs helps women recognize danger signs and seek better care. Women in Self-Help Groups (SHGs) benefit from both health literacy and funds for health reasons, improving the overall microfinance experience (Ahmad et al. 2021).

A study conducted by Solomon (2021) aimed to assess the impact of microfinance on women’s empowerment through Self-Help Groups (SHGs) revealed the importance of empowering women for a nation’s development, highlighting the key role played by microfinance institutions in such issues. The study reveals a notable impact of microfinance on both economic and social empowerment within self-help groups. Microfinance has contributed to women achieving greater self-independence, enabling them to address problems autonomously. Additionally, the study notes an increase in income and a boost in women’s confidence to move about freely (Solomon 2021).

Khandare and Gajanan (2016) found that women with better access to education, family protection plans, and additional information experience more guaranteed benefits from microfinance interventions. In a study by Kotahwala (2012), it was found that microfinance institutions play a significant role for the poor by providing a means to generate income. The small loans proved instrumental for women in initiating and managing small businesses, leading to financial gains. Beyond monetary benefits, microcredit had broader impacts. Women became more independent, gained knowledge and awareness, and enhanced their voice. Collaborating with other women increased mobility, and they acquired insights into their rights and the importance of expressing their opinions. Moreover, the absence of knowledge about clients, their backgrounds, and cultural and social norms contributes to the failure of microfinance initiatives. Recognizing the cultural context of a community facilitates the effective distribution of loans to women and enhances their success in small businesses (Kotahwala 2012).

In a study conducted in Bihar, India, Walia et al. (2020) found that sharing health messages in microfinance-based Self-Help Groups (SHGs) is linked to a notable increase in antenatal care (ANC) practices. The findings indicate the potential of microfinance based SHGs to enhance maternal health services (Walia et al. 2020). Another study conducted in the Kashmir Valley in India by Khan and Bhat (2022) revealed that women’s access to microfinance loans for starting businesses should be dependent on their ability to fully control financial and operational decisions in their enterprises. This approach aims to expedite the empowerment of women.

Several important microfinance institutions (MFIs) play a crucial role in India’s financial inclusion and development (Manzoor 2018). Key players include the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), Bharat Financial Inclusion, Bandhan Financial Services Limited, Equitas Small Finance, and the Small Industries Development Bank of India. Other notable MFIs, such as ESAF Microfinance and Investments, Fusion Microfinance, Annapurna Microfinance, Arohan Financial Services Limited, and BSS Microfinance Limited, also contribute significantly to empowering individuals in rural and underserved areas, fostering entrepreneurship, and facilitating financial access. A study by Vishwakarma (2017) revealed that MFIs should consider incorporating femininity in their board and senior management positions to enhance financial viability and social performance of women microfinance.

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) aids women’s empowerment in India through micro-entrepreneurship projects, supporting low-income entrepreneurs. ADB collaborates with microfinance institutions, facilitating access to financial resources. Additionally, the World Bank contributes to rural livelihoods, as seen in initiatives like the Northeast Rural Livelihoods Project (NERLP).

4.5. Maldives

Microfinance in Maldives is primarily facilitated through government initiatives and foreign aid agencies due to the absence of proper microfinance institutions. However, this process is not sustainable as people rely on voluntary aid (Muneeza 2011). While there have been credit programs in the past, including post-tsunami efforts, specific microfinance programs for women have been lacking. Microfinance plays a crucial role in the economic development of Maldives (Morduch and Cull n.d.). Various institutions, such as the Maldives Center for Islamic Finance (MCIF), BML Islamic, and Maldives Fund Management Corporation Limited (MFMC), contribute significantly to financial inclusion. Government-led initiatives, such as the Agricultural Revolving Fund for Economic Development and Credit for Women Empowerment, are implemented through standalone programs to support economic development across the islands (Sinha 2009).

4.6. Nepal

Women in Nepal face multiple challenges, including economic disempowerment, limited decision-making rights within families, lack of assets, insecure workplaces, early marriages, and restricted autonomy in pregnancy decisions (Lamichhane 2020). Dahal et al. (2022) emphasizes the vulnerability of Nepalese women to discrimination, attributing it to patriarchal structures, educational and skill deficiencies, workplace exclusions, and marginalization in decision-making processes. Microfinance institutions (MFIs) play a crucial role in addressing poverty and unemployment in Nepal by providing employment and self-employment opportunities. While these services have positively impacted women’s financial access, the utilization of credits and savings by deprived women remains limited. For microfinance to truly empower women, a substantial increase in the number of women actively using financial services is essential, influencing their bargaining power in domestic and outdoor decisions.

In 1982, the Nepalese government launched the Production Credit for Rural Women (PCRW), the country’s initial women-centric socio-economic initiative. Developed in collaboration with the United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), NRB, Commercial Banks (CBs), and ADBN, the program aimed to enhance women’s skills for economic development (Shakya 2016). Unfortunately, the program faced challenges in providing ample opportunities for rural women, attributed to the factors mentioned above and the prevalent issue of higher illiteracy among this demographic.

A study examining the influence of microfinance on women’s empowerment (Rajouria 2008) found that engaging in microfinance programs had noteworthy positive impacts on self-esteem, self-efficacy, and contributions to family income. The study controlled for socio-demographic variables such as age, education level, family size, and family income. The findings suggest that microfinance has the potential to empower female participants, as concluded by the study (Rajouria 2008).

Jain (2020) highlights the dual contribution of microfinance: empowering women economically and socially through productive activities and fostering national development by encouraging savings for education and future security. The involvement of women in microfinance emerges as a potent tool against poverty and gender inequality when integrated with broader economic and social strategies, as indicated by the positive association between microfinance services and women’s empowerment (Jain 2020).

Dhungana et al. (2023), highlight that certain microfinance strategies prove more beneficial for impoverished individuals compared to others. Consequently, communication strategies need to be tailored to the specific clientele. Private microfinance institutions (MFIs) and their approaches demonstrate greater outreach to the poor than other MFIs. Notably, communication strategies vary, as government-owned MFIs cater to better-educated clients who are more inclined to read newspapers. The exploratory factor analysis indicates that respondent women perceive both poverty alleviation and empowerment through these strategies.

A study investigating the impact of gender participation on the maturity of overdue microfinance loans in Nepal (Dahal et al. 2023) discovered that female borrowers tend to repay their loans on time compared to male borrowers. This suggests that policymakers should not hesitate to provide loans to female borrowers, and it indicates that non-performing loans do not increase due to female debtors (Dahal et al. 2023). Women show promise in both utilizing and repaying loans.

In Nepal, several Class D Development Banks, including Aasha Laghubitta Bittiya Sanstha Ltd., First Microfinance Bittiya Sanstha Ltd., Mero Microfinance Bittiya Sanstha Ltd., and National Microfinance Bittiya Sanstha Ltd., actively engage in microfinancing (Aryal 2019). Additionally, key Class A Commercial Banks like Bank of Kathmandu, Laxmi Bank Limited, KIST Commercial Bank, NMB Bank, and Nepal Rastra Bank play a vital role in deprived sector lending (Subedi and Timilsina 2023). Furthermore, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) contributes significantly to projects such as “Nepal: Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women”.

4.7. Pakistan

In Pakistan, approximately sixty percent (60%) of the population is living below the international poverty line, the majority of whom are women (Niaz and Iqbal 2019). According to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP 2016), Pakistan entered the microfinance industry relatively late, and yet, there exists an absence of a strong financial system for effectively alleviating poverty.

The potential role of Islamic microfinancing in improving people’s lives is substantial. However, only one fully-fledged Islamic microfinance bank is operational in Pakistan, as highlighted by Ayaz et al. (2019). The challenges in the Islamic microfinance industry in Pakistan stem from factors including the weak role of the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP), inadequate government support, bankers’ disinterest, lack of collateral, recovery risks, insufficient research in product development, low customer awareness, inadequate training, and skill development, as well as a shortage of trained staff with the banks (Ayaz et al. 2019).

According to World Bank sources, compared to all other South Asian countries, microfinance sector to women borrowers had always been extremely low for Pakistan, hovering between 50 to 60 percent of borrowers. Some argue that this is because most of the financial support for women are used by the men while the woman ‘borrower’ is responsible for attending all the group meetings, all repayments, all the stress, and all the transactions costs.

A study conducted to explore the influence and impact of microfinance on women’s entrepreneurship and empowerment in Pakistan (Mahmood 2011) discloses that microfinance enabled fewer than half of the women borrowers to initiate new business ventures. The majority of urban women utilized the funds for developing their own businesses. Approximately 62 percent of women utilized microfinance for business purposes, with a significant portion engaged in animal husbandry for milk production. However, some women did not employ the funds for the intended purpose, and this appears to be linked to a lack of business-related training. Nearly one in five women, predominantly those in rural areas, accessed microfinance for survival purposes, such as facilitating consumption or repaying existing loans (Mahmood 2011).

In a study conducted on the role of microfinance in the economic empowerment of women in Lahore, Pakistan, Shaheen et al. (2018) find that microfinance has a positive impact on the economic empowerment of women. This effect is attributed to women’s easy access to credit, its effective utilization, and the close monitoring by microfinance institution (MFI) officials who encourage clients to engage in entrepreneurial activities. The study concludes that interest-free microfinance is a key approach to empower women economically, allowing them to lead a life of respect and dignity. Meantime, in a study examining the non-financial services of microfinance institutions on women, Ul-Hameed et al. (2018) uncover the fact that those activities, such as training and skill development programs, along with social capital development, play a positive role in women’s empowerment. Additionally, the study highlights that vulnerability moderates the relationship between social capital and women’s empowerment (Ul-Hameed et al. 2018).

Key microfinance banks in Pakistan, including Advans Microfinance Bank, APNA Microfinance Bank, FINCA Microfinance Bank, Mobilink Microfinance Bank, NRSP Microfinance Bank, and Sindh Microfinance Bank, are pivotal in the sector (Saeed 2023). Non-bank microfinance entities (MBMFCS) like AGAHE Pakistan, Akhuwat Islamic Microfinance Company, AMRDO Foundation, Kashf Foundation, and others also play significant roles (Saeed 2023). The World Bank contributes through projects such as the Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund Project and the Third Pakistan Poverty Alleviation Fund Project (World Bank 2014).

4.8. Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka’, in a study by Rathiranee and Semasinghe (2015) titled “Factors determining women empowerment through microfinance: An empirical study in Sri Lanka”, the findings suggest that employing microfinance can enhance the income levels of women in the country. The aftermath of the 30-year civil war and the 2004 tsunami has left numerous women as single or widows, emphasizing the need for extra support, such as microfinancing, to help them rebuild their lives.

In the realm of women’s microfinance studies, there is a notable scarcity of research from Sri Lanka. Hansen (2015) conducted a study focusing on the impact of a microfinance intervention on psychological empowerment among women in the northern region of Sri Lanka. Psychological empowerment, encompassing personal control beliefs and social networks, was the key focus. The intervention included training, savings activities, and, for those effectively managing their economic situation, a microloan. While all women participated in group-saving activities, not everyone attended trainings or received microloans. The findings revealed that women engaged in the microfinance intervention exhibited higher levels of personal control beliefs and had a larger social network compared to a matched control group without access to microfinance services, highlighting the positive effects of such interventions on women’s empowerment (Hansen 2015).

The Women’s Development Federation (WDF) is actively engaged in fieldwork, collaborating with the largest grassroots women’s organization in Sri Lanka. Established in 1989 in the Hambantota District, WDF was founded by women with the goal of reducing poverty through women’s empowerment. Women in this region organized themselves into groups, initiating various activities to enhance the well-being of their families. Presently, WDF extends its reach to over 70,000 women, offering microfinance services and addressing health and nutrition issues as part of its ongoing efforts to combat poverty (WDF 2015).

A study conducted by Huis et al. (2019) explored the effects of husbands’ engagement in goal-setting training on women’s empowerment. The research suggests that providing women with access to microcredit and business training is an effective strategy to enhance their empowerment. Interestingly, while men appear to benefit from business training, the same does not hold true for women. However, women who participated in the training showed an increase in their SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound) goal-setting skills. Overall, business training was found to significantly enhance participants’ goal-setting abilities across different conditions, aligning with expectations (Huis et al. 2019).

In Sri Lanka, microfinance services are offered by a range of institutions, including licensed banks, finance companies, co-operative rural banks, thrift and credit co-operative societies, divinaguma banks, other community-based organizations, and microfinance companies (Central Bank of Sri Lanka n.d.). According to Thrikawala et al. (2018), the financial performance of MFIs in Sri Lanka sees enhancement in the presence of female CEOs, or client representatives on MFI boards. Furthermore, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) has played a role in supporting women entrepreneurs in Sri Lanka (ADB 2018).

5. Key Findings and Conceptual Framework

While the overall study on microfinance is extensive, comprehensive research specifically focusing on women’s microfinance impacts, evaluations, and potentials in South Asia remains limited. Even the existing studies predominantly rely on qualitative analyses, with a noticeable lack of quantitative assessments. Quantifying the impacts of microfinance initiatives is inherently challenging and time-consuming. Therefore, this study utilizes the updated literature on microfinance for women in South Asia to gauge its tangible effects on women.

The study successfully identified significant microfinance programs in each country, fulfilling one of its primary objectives. Additionally, it evaluated the main achievements, potential, and obstacles related to women’s microfinancing, addressing the second objective of the study based on the 38 selected studies. Table 2 summarizes findings from 38 studies conducted across South Asian countries, focusing on the positive impacts of microfinance, including microcredit and microloans, on women. The impacts assessed in these studies are categorized into the following six key indicators based on the existing literature:

Table 2.

Impact on women in microfinance intervention, 2000–2020.

- Decision-making abilities;

- Freedom of mobility;

- Education and skill development;

- Economic gains for the family;

- Self-confidence;

- Asset accumulation within households.

The findings on microfinance interventions for women’s empowerment in South Asia highlight diverse impacts across the region. Analysis focused on studies that clearly show positive outcomes for women, excluding those with insufficient data or negative effects. The data detail the percentage of positive impacts across six categories for each country, except Afghanistan and the Maldives, where data are lacking.

Table 2 illustrates the potential of microfinance to empower South Asian women. Pakistan and Sri Lanka stand out with the highest positive impacts on women’s decision-making roles, at 83.3% and 100%, respectively. However, freedom and mobility are generally low across the region, with most countries reporting 20% or lower, except India, which shows a higher rate of 55.5%. India also excels in education and skills, with an 88.9% positive impact, reflecting the effectiveness of its microfinance programs in this area. Economic gains vary widely, with Nepal achieving a 100% positive impact, while Sri Lanka’s impact is much lower at 20%. Self-confidence improvements are generally low, with India (55.5%) and Nepal (40%) performing slightly better.

In Bangladesh, a review of 10 studies on microfinance interventions reveals mixed impacts with decision-making (40%), freedom and mobility (10%), education and skills (30%), economic gains (50%), self-confidence (20%), and asset accumulation (30%). While economic gains and asset accumulation show relatively strong support, improvements in freedom and mobility are less consistent. Studies such as Chowdhury et al. (2005)’s work emphasize economic benefits and improved decision-making, while Murshid and Ely (2016) discuss shifts in household decision-making dynamics. Murshid (2018a) notes greater control over resources among microfinance participants, though Zafarullah and Nawaz (2019) highlight ongoing challenges from traditional and religious conservatism. Islam and Pakrashi (2020) suggest that microfinance may reinforce rather than challenge traditional roles, indicating that while there are positive impacts on economic and decision-making aspects, comprehensive empowerment is hindered by deep-rooted socio-cultural barriers.

In Bhutan, studies show positive impacts of microfinance on decision-making (66.7%), education and skills (33.3%), economic gains (66.7%), and asset accumulation (33.3%). Sariyev et al. (2020) highlight women’s roles in household decision-making and dietary quality, while Yoezer (2015) emphasizes the importance of credit access for boosting rural women’s economic empowerment. However, Zangpo (2014) points out that gender stereotypes within families and communities limit women’s participation in economic activities, indicating that socio-cultural barriers still impede comprehensive empowerment despite positive impacts in certain areas.

For India, 88.9% of studies report positive effects on education and skills, and 66.7% highlight economic gains. Improvements are also noted in freedom and mobility (55.5%) and self-confidence (55.5%), with moderate impacts on decision-making and asset accumulation (44.4% each). Walia et al. (2020) link health message sharing in microfinance-based SHGs to increased antenatal care practices and education, while Kotahwala (2012) emphasizes the importance of cultural context in successful loan distribution. Studies by Khan and Bhat (2022) and Vishwakarma (2017) reveal that microfinance loans for business start-ups improve decision-making.

In Nepal, all studies (100%) report positive effects on economic gains, with 40% noting improvements in decision-making, education and skills, and self-confidence; freedom and mobility show a 20% positive impact. Rajouria (2008) finds significant positive impacts on self-esteem, self-efficacy, and family income contributions, while Jain (2020) highlights economic benefits through women’s empowerment. Dahal et al. (2023) find that female borrowers repay their loans on time compared to male borrowers.

In Pakistan, decision-making (83.3%) and economic gains (66.7%) show significant improvements, though impacts on self-confidence (16.7%) and freedom and mobility (16.7%) are notably lower. Education and skills have a 50% positive impact. The World Bank reports low participation rates in Pakistan’s microfinance sector for women, with Mahmood (2011) noting that fewer than half of women borrowers initiate new businesses. Shaheen et al. (2018) highlight economic empowerment, while Ul-Hameed et al. (2018) stress the importance of training and skill development.

In Sri Lanka, microfinance programs show consistent positive impacts on decision-making and education and skills, with 100% of studies reflecting these benefits. However, economic gains are noted in only 20% of studies, and improvements in freedom and mobility and self-confidence are minimal, at 20% and 10%, respectively. Rathiranee and Semasinghe (2015) find enhanced income levels, while Hansen (2015) notes psychological empowerment improvements. Huis et al. (2019) suggest that involving husbands in goal-setting training supports women’s empowerment, highlighting the mixed success of microfinance in different areas.

Comparing these findings with research from African regions, studies in Ghana show that women’s empowerment through microfinance leads to increased workforce participation and positive economic impacts (Peprah 2012; Salia et al. 2017; Addai 2017). In Ethiopia, microfinance institutions are key to economic development for women and low-income groups (Meressa 2020). A global study of 50,229 clients, including 66 percent women, reveals that microfinance improves financial literacy, household conditions, and resource management (60 Decibels, FinDev Gateway). These findings underscore the broader potential of microfinance to positively impact women’s empowerment, although the extent and nature of these impacts vary by region and are influenced by local socio-cultural factors.

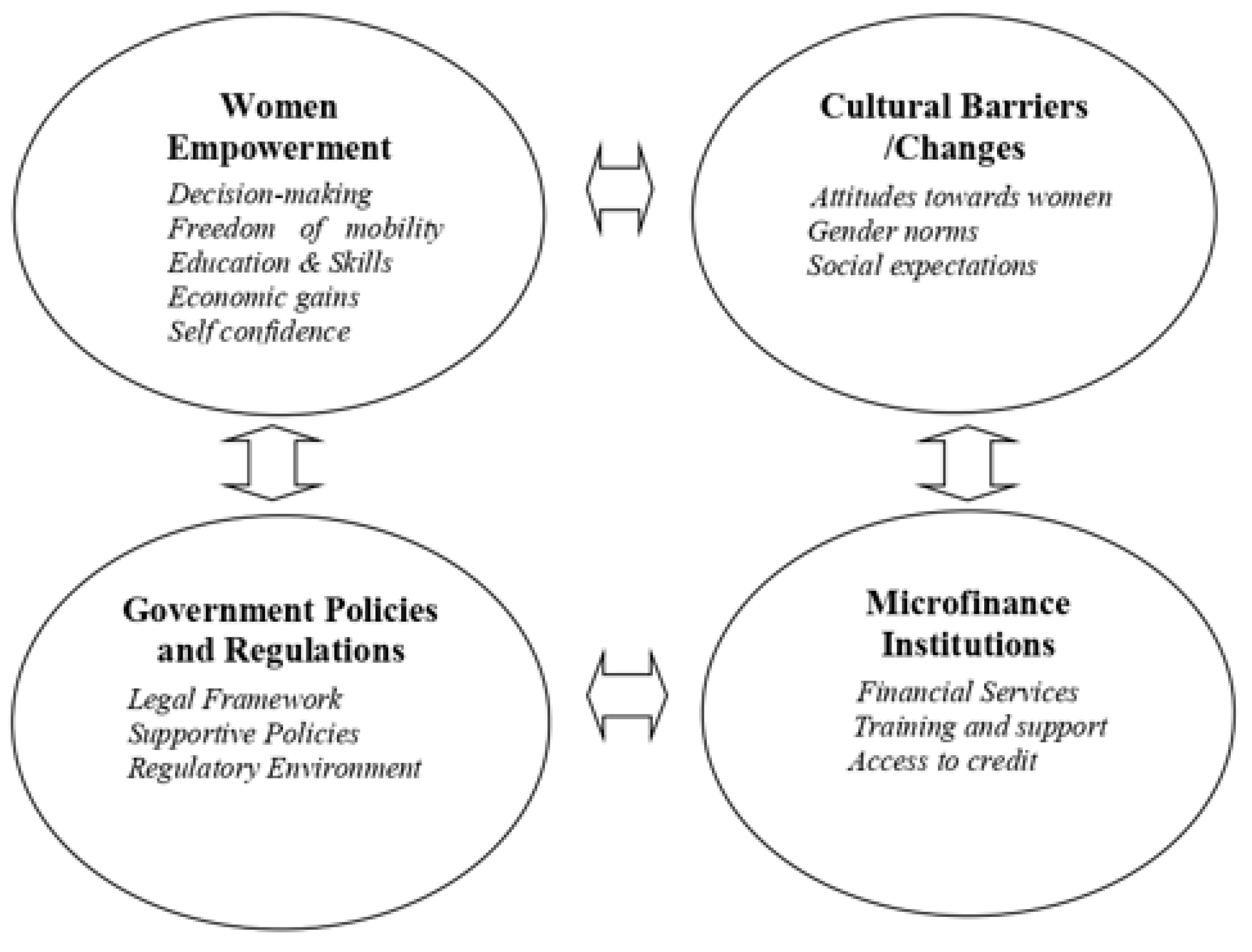

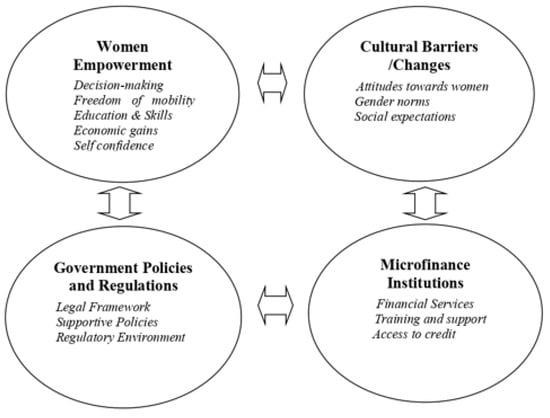

While Table 2 focuses on the positive effects observed only in selected studies, the literature highlights additional factors influencing women’s experiences in microfinance. Cultural barriers, women’s limited educational opportunities, social expectations and acceptance, unpaid caregiving responsibilities including childcare, and inadequate access to information are identified as significant challenges affecting women’s participation in microfinance initiatives. Moreover, networking emerges as a crucial factor contributing to the success of microfinance programs aimed at empowering women. The study’s findings contribute to the development of a conceptual framework for understanding the fundamental structure of women’s microfinance in South Asia, addressing the final objective of the study as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Conceptual framework for microfinancing women in South Asia. Source: Developed by author.

The framework offers a structured approach to analyzing the problem, understanding the relationships among key factors, and exploring potential policy options. It comprises the following four essential components: microfinance institutions, government policies and regulations, cultural barriers/changes, and women’s empowerment.

Microfinance institutions play a crucial role by offering essential financial services, training, and access to credit, which empower women to participate in economic activities. The effectiveness of these institutions is heavily influenced by government policies and regulations, which provide the necessary legal framework, supportive policies, and regulatory environment for microfinance initiatives to thrive.

Additionally, cultural barriers/changes, including societal attitudes towards women, entrenched gender norms, and prevailing social expectations, significantly affect how women can utilize microfinance opportunities. These cultural factors can either hinder or facilitate the empowerment process.

Ultimately, the interplay of these components impacts women’s empowerment, enhancing their decision-making abilities, freedom of mobility, education and skills, economic gains, and self-confidence. This framework highlights the multifaceted nature of empowering women through microfinance, underscoring the need for a holistic approach that addresses financial, regulatory, and cultural dimensions to achieve sustainable and meaningful empowerment.

6. Review Conclusions and Limitations

Advancing women’s empowerment in South Asia presents a multifaceted and challenging endeavor. Women in the region face high poverty rates, limited educational opportunities, and entrenched cultural barriers, making progress in this area particularly demanding. Sharing clear information and fostering strong networks is crucial for encouraging meaningful discussions about women’s empowerment. These efforts must be tailored to the unique cultural and societal contexts of each country. Increasing research on the impacts of women’s empowerment initiatives will offer policymakers valuable insights to refine and enhance funding programs for women across the region.

This study aimed to achieve three primary objectives: First, it identified the significance of microcredit and microfinance programs for women in South Asia, highlighting their role in economic empowerment. Second, the study recognized the main achievements, potential, and obstacles within women’s microfinancing programs, shedding light on areas of success and ongoing challenges. Finally, the study developed a comprehensive framework and discussed policy strategies to enhance the benefits of women’s microfinancing in the region.

The research met these objectives to varying degrees. Identifying significant microfinance programs provided useful insights into their impact on women’s empowerment, even with limited studies. Evaluating achievements, potentials, and obstacles offered a clearer view of the current state of women’s microfinancing. Additionally, developing an initial conceptual framework provided a basic approach for addressing challenges and exploring opportunities in the sector. Overall, the findings contribute to a more informed perspective on women’s microfinancing in South Asia and highlight the need for continued research and tailored policy interventions to support and enhance women’s empowerment efforts in the region.

A primary limitation of this study was the challenge of locating published articles and other studies specifically focused on women’s microfinancing. Many microfinancing initiatives in the region target both men and women among the poor, which was not the extent of this study. These broader microfinancing efforts also yield positive impacts on families and society, ultimately affecting women’s empowerment either directly or indirectly.

In countries like Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nepal, women encounter significant barriers to achieving fair participation in economic activities. Afghanistan faces several limitations and potential biases, including an unstable political and security situation, leading to gaps in available information. Studies often rely on small sample sizes that may not represent the broader population, potentially skewing the results. For instance, a country like India with a large female population needs more data. Cultural biases and societal norms can influence both the reporting and interpretation of data. Researchers may face challenges in accessing certain regions or communities, and women themselves might be hesitant to participate due to fears of social stigma or retribution. This is especially prominent in rural areas of Muslim countries where women are less likely to be allowed to participate in outdoor activities.

Furthermore, the influence of external donor agendas can sometimes shape research priorities and methodologies, introducing another layer of bias into the studies used for this review analysis. The inconsistency in program delivery, training, and support services can lead to heterogeneous outcomes, making it difficult to attribute observed changes solely to microfinance activities. Lastly, there is a need for longitudinal studies to assess the long-term impacts of microfinance on women’s empowerment and economic stability. The short-term nature of most studies does not account for the sustainability of the benefits gained through microfinance, nor does it capture potential long-term challenges or setbacks. Addressing these limitations in future research is essential. Therefore, it is essential to approach conclusions with caution and consider the inherent limitations and potential biases present in the research context.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Acharya, Meena, and Puspa Ghimire. 2005. Gender indicators of equality, inclusion and poverty reduction: Measuring programme/project effectiveness. Economic and Political Weekly 40: 4719–28. [Google Scholar]

- Addai, Bismark. 2017. Women empowerment through microfinance: Empirical evidence from Ghana. Journal of Finance and Accounting 5: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Danish, Itismita Mohanty, Avishek Hazra, and Theo Niyonsenga. 2021. The knowledge of danger signs of obstetric complications among women in rural India: Evaluating an integrated microfinance and health literacy program. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 21: 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, Isahaque, and Zulkarnain A. Hatta. 2012. Women’s empowerment or disempowerment through microfinance; evidence from Bangladesh. Asian Social Work and Policy Review 6: 111–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, Mina. 2019. List Of Class D Banks In Nepal. Available online: https://ictframe.com/list-of-class-d-bank-in-nepal/ (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- Asian Development Bank. 2018. ADB Receives $12.6 Million Grant from We-Fi to Promote Sri Lankan Women Entrepreneurs. News Release. Available online: https://www.adb.org/news/adb-receives-126-million-grant-we-fi-promote-sri-lankan-women-entrepreneurs (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- Asian Development Bank. 2023. Afghanistan: Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.adb.org/publications/afghanistan-fact-sheet (accessed on 26 December 2023).

- Ayaz, Mohammad H. Shah, Amanthun Noor, Sadaf Shaheen, and Jibrail Bin Yusuf. 2019. Islamic microfinancing by the banking sector of Pakistan: Problems and solutions. Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization 9: 148–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, Abhijit, Esther Duflo, Rachel Glennerster, and Cynthia Kinnan. 2015. The miracle of microfinance? Evidence from a randomized evaluation. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 7: 22–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, D. Kingsley, Low Lock Teng Kevin, and Aye Aye Khin. 2016. Entrepreneurial success through microfinance services among women entrepreneurs in Sri Lanka: A pilot study and overview of the findings. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 6: 1144–50. [Google Scholar]

- Central Bank of Sri Lanka. n.d. Microfinance Sector. Available online: https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/en/financial-system/financial-system-stability/microfinance-sector (accessed on 27 December 2023).

- Chowdhury, M. Jahangir Alam, Dipak Ghosh, and Robert E. Wright. 2005. The impact of micro-credit on poverty: Evidence from Bangladesh. Progress in Development Studies 5: 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, Tamgid Ahmed, and Pundarik Mukhopadhaya. 2011. Poverty Alleviation and Service Delivery: Government and Non-Government Organizations in Rural Bangladesh. Oxford Development Studies 39: 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cull, Robert, Asli Demirguç-Kunt, and Jonathan Morduch. 2007. Financial Performance and Outreach: A Global Analysis of Leading Microbanks. The Economic Journal 117: F107–F133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cull, Robert, Asli Demirguç-Kunt, and Jonathan Morduch. 2008. Microfinance Meets the Market. Journal of Economic Perspectives 23: 167–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, Arjun Kumar, Ganesh Bhattarai, and Prem Bahadur Budhathoki. 2023. Effect of gender participation on determining the maturity of crossed-due loans: Evidence from microfinance companies of Nepal. Banks and Bank Systems 18: 184–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, Pranab, Sunil Kumar Joshi, and Katarina Swahnberg. 2022. A qualitative study on gender inequality and gender-based violence in Nepal. BMC Public Health 22: 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalal, Koustuv, Örjan Dahlström, and Toomas Timpka. 2013. Interactions between microfinance programmes and non-economic empowerment of women associated with intimate partner violence in Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 3: e002941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhungana, Bharat Ram, Ramkrishna Chapagain, and Arvind Ashta. 2023. Alternative strategies of for-profit, not-for-profit and state-owned Nepalese microfinance institutions for poverty alleviation and women empowerment. Cogent Economics & Finance 11: 2233778. [Google Scholar]

- Duflo, Esther. 2012. Women’s empowerment and economic development. Journal of Economic Literature 50: 1051–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elson, Diane. 1999. Labor markets as gendered institutions: Equality, efficiency, and empowerment. World Development 27: 611–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endeley, Joyce B. 2001. Conceptualising women’s empowerment in societies in Cameroon: How does money fit in? Gender and Development 9: 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaonkar, Rekha R. 2004. Role of Self-Help Groups in Empowerment of women. Paper presented at the ISTR Sixth National Conference, Toronto, ON, Canada, July 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, Prashant Kumar, and Seema Sharma. 2023. Literature review on effect of microfinance institutions on poverty in South Asian countries and their sustainability. International Journal of Emerging Markets 18: 1827–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Nina. 2015. The development of psychological capacity for action: The empowering effect of a microfinance program on women in Sri Lanka. Journal of Social Issues 71: 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Abul, and Shamim Saleem. 2017. An Islamic microfinance business model in Bangladesh: Its role in alleviation of poverty and socio-economic well-being of women. Humanomics 33: 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, Niels, and Marek Hudon. 2018. Determinants of the performance of microfinance institutions: A systematic review. Journal of Economic Surveys 32: 1483–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, Niels, Robert Lensink, and Aljar Meesters. 2009. Outreach and Efficiency of Microfinance Institutions. Groningen: Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Groningen. [Google Scholar]

- Huis, Marloes Anne, Nina Hansen, Sabine Otten, and Robert Lensink. 2019. The impact of husbands’ involvement in goal-setting training on women’s empowerment: First evidence from an intervention among female microfinance borrowers in Sri Lanka. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology 29: 336–51. [Google Scholar]

- ILO (Iinternational Labor Organization). n.d. Small Change, Big Challenges: Women and Microfinance. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---gender/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_091581.pdf (accessed on 26 December 2023).

- Islam, Asadul, and Debayan Pakrashi. 2020. Labour market participation of women in rural Bangladesh: The role of microfinance. The Journal of Development Studies 56: 1927–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, Bandana. 2020. Microfinance services and women empowerment in Biratnagar metropolitan, Nepal. Journal of Underrepresented & Minority Progress 4: 251–70. [Google Scholar]

- Jamtsho, Thinley. 2018. Women Empowerment through Microfinance in Thimphu, Bhutan. Ph.D. dissertation, Royal Institute of Management (RIM), Semtokha, Thimpu, Bhutan. [Google Scholar]

- Javid, Attiya Yasmin, and Afsheen Abrar. 2015. Microfinance institutions and poverty reduction: A cross regional analysis. The Pakistan Development Review 54: 371–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer, Naila. 1999. Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change 30: 435–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Shagufta Tariq, and Mohd Abass Bhat. 2022. Can microfinance-backed entrepreneurship be a holistic empowerment tool for women? Empirical evidence from Kashmir Valley, India. Journal of Business and Socio-Economic Development 2: 117–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandare, D. M., and Ratnaparkhe D. Gajanan. 2016. A Study of Microfinance and Women Empowerment in Rural Development in India. BVIMSR’s Journal of Management Research 8: 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Khursheed, Ambreen, Ather Azim Khan, and Faisal Mustafa. 2021. Women’s Social Empowerment and Microfinance: A Brief Review of Literature. Journal of International Women’s Studies 22: 249–65. [Google Scholar]

- Kotahwala, Vidhi. 2012. Microfinance in India and How it Empowers Women. Ph.D. dissertation, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Lamichhane, Basu Dev. 2020. Microfinance for women empowerment: A review of best practices. Interdisciplinary Journal of Management and Social Sciences 1: 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyby, Erik. 2006. Microfinance and Gender Roles in Afghanistan. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, Samia. 2011. Microfinance and women entrepreneurs in Pakistan. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 3: 265–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldives Bureau of Statistics. 2022. Census 2022. Available online: https://census.gov.mv/2022/ (accessed on 26 December 2023).

- Manzoor, Amir. 2018. Role of Microfinance Institutions in Development of India. In Microfinance and Its Impact on Entrepreneurial Development, Sustainability, and Inclusive Growth. Hershey: IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayoux, Linda. 2000. Micro-Finance and the Empowerment of Women: A Review of the Key Issues. ILO Working Papers No. 993441343402676. Geneva: International Labor Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Meressa, Hayelom Abrha. 2020. Growth of micro and small-scale enterprises and its driving factors: Empirical evidence from entrepreneurs in emerging region of Ethiopia. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 9: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, Md Aslam. 2021. Participation of women in the South Asian microfinance industry: An observation. Journal of Public Affairs 21: e2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, Md Aslam. 2022. Microfinance and Microfinance Institutions: History, Concept and Purpose. In Social Purpose, Commercialization, and Innovations in Microfinance. Singapore: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, Md Aslam, Hwok-Aun Lee, V. G. R. Chandran, Rajah Rasiah, and Mahfuzur Rahman. 2019. History of microfinance in Bangladesh: A life cycle theory approach. Business History 61: 703–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizanur Rahman, M., and Fariduddin Ahmad. 2004. Impact of microfinance of IBBL on the rural poor’ livelihood in Bangladesh: An empirical study. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 3: 168–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morduch, Jonathan J., and Beatriz Armendariz. 2010. The Economics of Microfinance. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. ISBN 978026251398. [Google Scholar]

- Morduch, Jonathan J., and Robert J. Cull. n.d. Microfinance and Economic Development. Policy Research Working Paper, No. WPS 8252. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/107171511360386561/Microfinance-and-economic-development (accessed on 5 January 2024). (In English)

- Muneeza, Rusni Hassan Aishath. 2011. Islamisation Of Microfinance: A Case Study Of Maldives. Journal of Applied Sciences Research 7: 2189–99. [Google Scholar]

- Murshid, Nadine Shaanta. 2018a. Microfinance participation and women’s empowerment: Evidence from a nationally representative sample of women in Bangladesh. Journal of Social Service Research 44: 375–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshid, Nadine Shaanta. 2018b. Women’s participation in microfinance: Does it increase their control over resources? Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 28: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshid, Nadine Shaanta, and Gretchen E. Ely. 2016. Microfinance participation and contraceptive decision-making: Results from a national sample of women in Bangladesh. Public Health 139: 141–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, Deepa. n.d. Empowerment and Poverty Reduction: A Sourcebook. World Bank. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/827431468765280211/Empowerment-and-poverty-reduction-a-sourcebook (accessed on 22 December 2023).

- Nayak, Akhaya Kumar. 2015. Developing Social Capital through Self-help Groups. Indore Management Journal 7: 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Nayak, Akhaya Kumar, and Prabin Kumar Panigrahi. 2020. Participation in self-help groups and empowerment of women: A structural model analysis. The Journal of Developing Areas 54: 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]