Conceptualizing the Patterns of Change in Cultural Values: The Paradoxical Effects of Modernization, Demographics, and Globalization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Culture and Cultural Value Dimensions

2.1. Inglehart’s Traditional vs. Secular-Rational

2.2. Inglehart’s Survival vs. Self-Expression Values

2.3. Hofstede’s Collectivism vs. Individualism

2.4. Schwartz’s Embeddedness (Conservatism) vs. Autonomy

2.5. Hofstede’s Power Distance

2.6. Hofstede’s Past vs. Future Orientation (Short- vs. Long-Term)

2.7. Schwartz’s Hierarchy vs. Egalitarianism

2.8. GLOBE’s Gender Egalitarianism

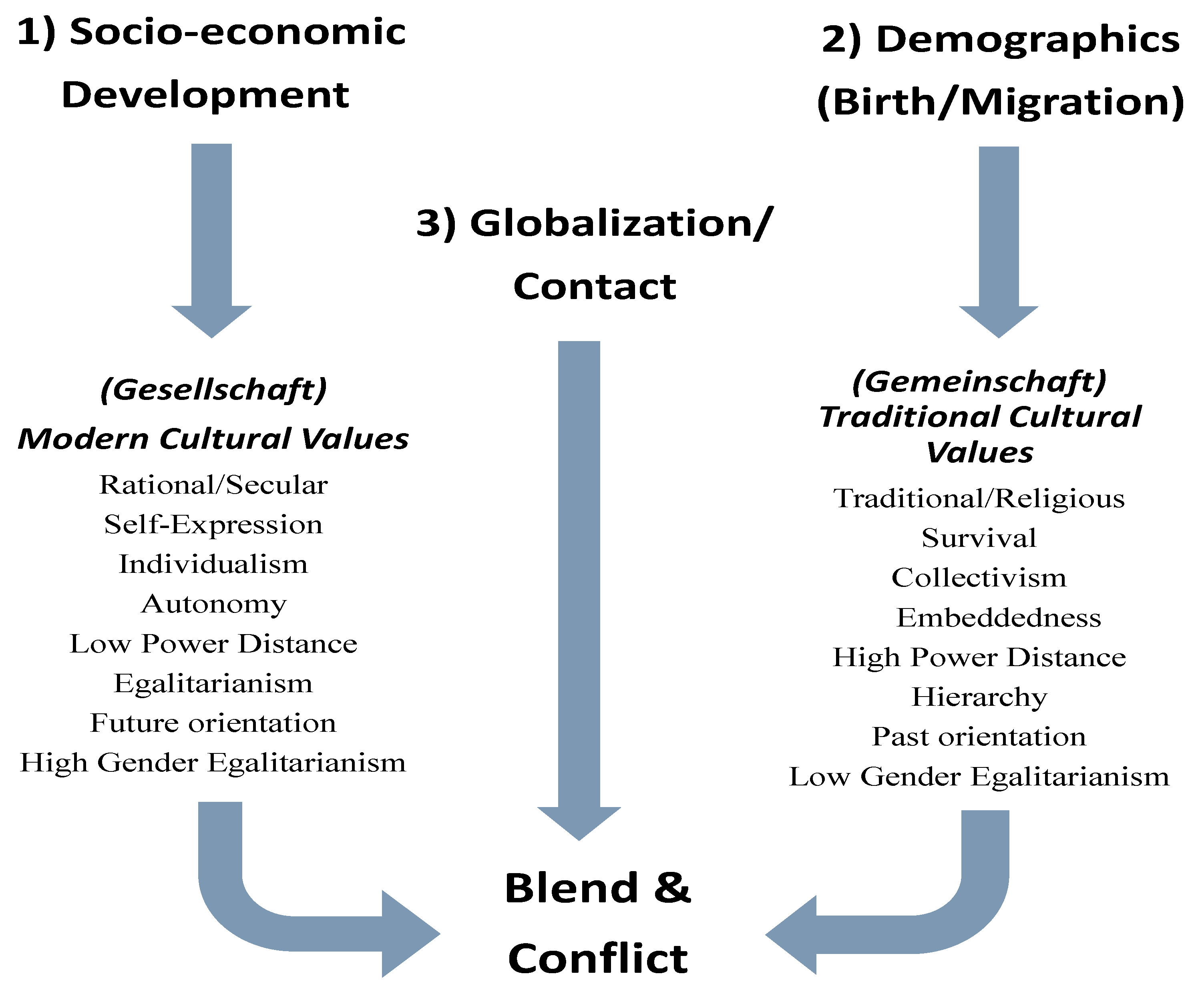

3. Pattern-1: Cultural Change via Socio-Economic Development: The Growth of Modern (Gesellschaft) Values

The Changes in Cultural Dimensions via Modernization

- Traditional vs. Secular-Rational

- Survival vs. Self-Expression Values

- Collectivism vs. Individualism

- Embeddedness (Conservatism) vs. Autonomy

- High Power Distance vs. Low Power Distance

- Hierarchy vs. Egalitarianism

- Past vs. Future Orientation

- High vs. Low Gender Egalitarianism

4. Highlighting the Relationship between Modernization and Cultural Value Dimensions

5. Pattern-2: Cultural Change via Demographics: The Growth of Traditional (Gemeinschaft) Values

The Changes in Cultural Dimensions via Birth and Migration

- Traditional vs. Secular-Rational

- Survival vs. Self-Expression Values

- Collectivism vs. Individualism

- Embeddedness (Conservatism) vs. Autonomy

- High Power Distance vs. Low Power Distance

- Hierarchy vs. Egalitarianism

- Past vs. Future-Orientation

- High vs. Low Gender Egalitarianism

6. Highlighting the Relationships between Cultural Dimensions, Birth Rates and Migration

7. Pattern-3: Cultural Change via Globalization and Contact: The Blend of Traditional (Gemeinschaft) and Modern (Gesellschaft)

7.1. Globalization/Contact and the Spread of Modern (Gesellschaft) Values

7.2. Globalization/Contact and the Persistence of Traditional (Gemeinschaft) Values

7.3. Globalization/Contact and the Blend of Traditional and Modern Values

8. Discussion

9. Modeling the Dynamic Relationship between Traditional and Modern Cultures

10. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akaliyski, Plamen, Christian Welzel, and Josef Hien. 2022. A community of shared values? Dimensions and dynamics of cultural integration in the European Union. Journal of European Integration 44: 569–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1990. Disjuncture and difference in the global cultural economy. Theory, Culture & Society 7: 295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Bacaër, Nicolas. 2011. Lotka, Volterra and the predator–Prey system (1920–1926). In A Short History of Mathematical Population Dynamics. London: Springer, pp. 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, Maurice Stevenson. 1957. On theoretical models for competitive and predatory biological systems. Biometrika 44: 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Ulrich. 2018. What Is Globalization? Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Daniel. 1973. The Coming of Post-Industrial Society. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Daniel. 1976. The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bendix, Reinhard. 1974. Inequality and social structure: A comparison of Marx and Weber. American Sociological Review 39: 149–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, Peter. 2002. The Cultural Dynamics of Globalization. In Many Globalizations: Cultural Diversity in the Contemporary World. Edited by Peter L. Berger and Samuel P. Huntington. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, Peter L., and Samuel P. Huntington, eds. 2003. Many Globalizations: Cultural Diversity in the Contemporary World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, Richard D. E. 2009. Globalization and cultural identity in Caribbean society: The Jamaican case. Caribbean Journal of Philosophy 1: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Carnoy, Martin, Manuel Castells, Stephen S. Cohen, and Fernando Henrique Cardoso. 1993. The New Global Economy in the Informational Age: Reflections on Our Changing World. University Park: Penn State Press. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, Manuel. 1996. The Network Society. Oxford: Blackwell, 469 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Cvetkovich, Ann. 2018. Articulating the Global and the Local: Globalization and Cultural Studies. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Desilver, Drew. 2019. Despite Global Concerns about Democracy, More than Half of Countries Are Democratic. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/05/14/more-than-half-of-countries-are-democratic/ (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Dollar, David, and Roberta Gatti. 1999. Gender Inequality, Income, and Growth: Are Good Times Good for Women? Washington, DC: Development Research Group, The World Bank, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Drescher, Jack. 2015. Out of DSM: Depathologizing homosexuality. Behavioral Sciences 5: 565–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durkheim, Émile, and Niklas Luhmann. 1988. Über soziale Arbeitsteilung: Studie über die Organisation höherer Gesellschaften. Berlin: Suhrkamp. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstadt, Shmuel N. 2000. The Reconstruction of Religious Arenas in the Framework of Multiple Modernities’. Millennium 29: 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Tony. 2003. A critique of Hofstede’s fifth national culture dimension. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 3: 347–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, Nancy, Roberto Patricio Korzeniewicz, and Valerie Durrant. 2000. Gender inequalities and economic growth: A longitudinal evaluation. Economic Development and Cultural Change 48: 573–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, Francis. 1989. The end of history? The National Interest 16: 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry, William A., and Trudy E. Sparks. 2012. A convergence/divergence perspective of leadership competencies managers believe are most important for success in organizations: A cross-cultural multilevel analysis of 40 countries. Journal of Business and Psychology 27: 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, Anthony. 1990. Thee Consequences of Modernity Cambridge. Polity 53: 245–60. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Chao. 2015. Cultural convergence, divergence, and crossvergence. In Wiley Encyclopedia of Management. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, Conrad, Phillip Connor, Marcin Stonawski, Vegard Skirbekk, Magdalena Potancokova, and Guy Abel. 2015. The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010–2050. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Edward T. 1976. Beyond Culture. New York: Anchor Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, John L., Joseph Clatworthy, Ian H. McNaughton, and Graham R. Sagar. 1961. The evolution and ecology of closely related species living in the same area. Evolution 15: 209–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassell, Michael P., and Herbert N. Comins. 1976. Discrete-time models for two-species competition. Theoretical Population Biology 9: 202–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofstede, Geert. 2001. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations. Thousand Oaks: Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Holmwood, John. 2005. Functionalism and its Critics. In Modern Social Theory: An Introduction. Glendale: Scientific Research Publishing, pp. 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- House, Robert J., Paul J. Hanges, Mansour Javidan, Peter W. Dorfman, and Vipin Gupta. 2004. Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, Samuel P. 1968. Political Order in Changing Societies. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, Ronald F. 1997. Modernization and Post-Modernization: Cultural, Economic and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Christian Welzel. 2005. Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Pippa Norris. 2004. Sacred and Secular. Religion and Politics Worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, (Cambridge Studies in Social Theory, Religion, and Politics). [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Wayne E. Baker. 2000. Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review 65: 19–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkeles, Alex. 2019. One World Emerging?: Convergence and Divergence in Industrial Societies. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, Bruce E. 2016. Globalization and convergence–divergence of HRM across nations: New measures, explanatory theory, and non-standard predictions from bringing in economics. Human Resource Management Review 26: 338–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenworthy, Lane, and Melissa Malami. 1999. Gender inequality in political representation: A worldwide comparative analysis. Social Forces 78: 235–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluckhohn, Florence Rockwood, and Fred L. Strodtbeck. 1961. Variations in Value Orientations. New York: Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Kroeber, Alfred Louis, and Clyde Kluckhohn. 1952. Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions. In Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, vol. 47, pp. 1–223. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Seonghoon, Mingnan Liu, and Mengyao Hu. 2017. Relationship between future time orientation and item nonresponse on subjective probability questions: A cross-cultural analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 48: 698–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévi-Strauss, Claude, and Georges Charbonnier. 1969. Entretiens avec Claude Lévi-Strauss. Paris: Union générale d’éditions. [Google Scholar]

- Lotka, Alfred J. 1925. Elements of Physical Biology. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane, Alan. 1992. Louis Dumont and the origins of individualism. The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology 16: 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- McGrew, Anthony. 1990. A Global Society. In Modernity and Its Futures. Edited by Stuart Hall, David Held and Tony McGrew. Cambridge: Polity Press in association with the Open University, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Minkov, Michael, and Geert Hofstede. 2014. Nations versus religions: Which has a stronger effect on societal values? Management International Review 54: 801–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2011. Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, Roderick. 2015. The European Union and the Geopolitics of Migration. UI Paper no. 1/2015. Available online: https://www.ui.se/globalassets/butiken/ui-paper/2015/european-union-and-the-geopolitics-of-migration---rp.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Phillips, Mark Salber, Mark Phillips, and Gordon J. Schochet, eds. 2004. Questions of Tradition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse, Jan Nederveen. 1996. Globalization and culture: Three paradigms. Economic and Political Weekly 31: 1389–93. [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse, Jan Nederveen. 2006. Globalization Goes in Circles: Hybridities East-West. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/252220774_Globalization_goes_in_circles_Hybridities_East-West (accessed on 12 August 2009).

- Prasad, Ajnesh, and Pushkala Prasad. 2006. Global Transitions: The Emerging New World Order and its Implications for Business and Management. Business Renaissance Quarterly 1: 91–113. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, Andrew. 1999. Women in the Legislatures and Executives of the World: Knocking at the Highest Glass Ceiling. World Politics 51: 547–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzer, George, and Zeynep Atalay, eds. 2010. Readings in Globalization: Key Concepts and Major Debates. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, Roland. 2001. Globalization Theory 2000+: Ma] or Problematics. In Handbook of Social Theory. p. 458. Available online: https://omnilogos.com/globalization-theory-major-problematics/ (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Rule, Wilma. 1994. Women’s Underrepresentation and Electoral Systems. Political Science and Politics 27: 689–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 1992. Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 Countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Edited by M. P. Zanna. San Diego: Academic Press, vol. 25, pp. 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 1994. Beyond Individualism/Collectivism: New Cultural Dimensions of Values. In Individualism and Collectivism: Theory, Method and Applications. Edited by U. Kim, H. C. Triandis, Ç. E. Kâğitçibaşi, S. C. E. Choi and G. E. Yoon. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 85–122. [Google Scholar]

- Seguino, Stephanie. 2011. Help or hindrance? Religion’s impact on gender inequality in attitudes and outcomes. World Development 39: 1308–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siaroff, Alan. 2000. Women’s representation in legislatures and cabinets in industrial democracies. International Political Science Review 21: 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmel, Georg. 1997. Simmel on Culture: Selected Writings. Thousand Oaks: Sage, vol. 903. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, John. 2003. Globalization and Cultural Identity. The GlobalTrans- Formations Reader 2: 269–77. [Google Scholar]

- Tönnies, Ferdinand. 1957. Community and Society (gemeinschaft und gesellschaft). Translated by Charles P. Loomis. East Lansing: The Michigan State University Press. First published in 1887. [Google Scholar]

- Tönnies, Ferdinand, and John Harris. 2001. Tonnies: Community and Civil Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tung, Rosalie L., and Alain Verbeke. 2010. Beyond Hofstede and GLOBE: Improving the quality of cross-cultural research. Journal of International Business Studies 41: 1259–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 2019. Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division 2019. World Population Prospects 2019. Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/423). New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- Volterra, Vito. 1928. Variations and fluctuations in the number of individuals in animal species living together. ICES Journal of Marine Science 3: 3–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welzel, Christian, Ronald Inglehart, and HansDieter Klingemann. 2003. Human development as a theory of social change: A cross-cultural perspective. European Journal of Political Science 42: 341–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Traditional Societies (Gemeinschaft) Developing Economies | Modern Societies (Gesellschaft) Developed Economies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Dimension | HDI | Modernization | Cultural Dimension | HDI | Modernization |

| Traditional/Religious | −0.597 ** | −0.896 ** | Rational/Secular | +0.597 ** | +0.896 ** |

| Survival | −0.569 ** | −0.959 ** | Self-Expression | +0.569 ** | +0.959 ** |

| Collectivism Embeddedness | −0.638 ** −0.617 ** | −0.503 ** −0.818 ** | Individualism Autonomy | +0.638 ** +0.617 ** | +0.503 ** +0.818 ** |

| High Power Distance Hierarchy | −0.552 ** −0.493 ** | −0.631 ** −0.523 ** | Low Power Distance Egalitarianism | +0.552 ** +0.493 ** | +0.631 ** +0.523 ** |

| Past orientation | −0.340 ** | −0.290 * | Future orientation | +0.340 ** | +0.290 * |

| Low Gender Egalitarianism | −0.476 ** | −0.559 ** | High Gender Egalitarianism | +0.476 ** | +0.559 ** |

| Traditional Societies (Gemeinschaft) Developing Economies | Modern Societies (Gesellschaft) Developed Economies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Dimension | Fertility | Out-Migration | Cultural Dimension | Fertility | Out-Migration |

| Traditional/Religious | +0.604 ** | +0.191 | Rational/Secular | −0.604 ** | −0.191 |

| Survival | +0.102 | +0.491 ** | Self-Expression | −0.102 | −0.491 ** |

| Collectivism Embeddedness | +0.315 ** +0.498 ** | +0.485 ** +0.381 ** | Individualism Autonomy | −0.315 ** −0.498 ** | −0.485 ** −0.381 ** |

| High Power Distance Hierarchy | +0.229 +0.246 | +0.363 ** +0.321 * | Low Power Distance Egalitarianism | −0.229 −0.246 | −0.363 ** −0.321 * |

| Past orientation | +0.336 ** | +0.273 * | Future orientation | −0.336 ** | −0.273 * |

| Low Gender Egalitarianism | +0.281* | +0.173 * | High Gender Egalitarianism | −0.281 * | −0.173 * |

| The Year 1900 | Year 1950 | The Year 2000 | Year 2022 | Growth Percent | The Year 1900 | Year 1950 | The Year 2000 | Year 2022 | Growth Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 45 * m | 51 m | 59 m | 67 m | 49% | Egypt | 10 m | 21 m | 69 m | 106 m | 960% |

| France | 39 m | 42 m | 61 m | 68 m | 74% | Saudi Arabia | 2.5 m | 3.2 m | 20 m | 36 m | 1340% |

| Germany | 57 m | 51 m | 82 m | 84 m | 47% | Nigeria | 16 m | 38 m | 122 m | 216 m | 1250% |

| Italy | 33 m | 47 m | 57 m | 59 m | 79% | Algeria | 5 m | 9 m | 31 m | 46 m | 820% |

| Spain | 19 m | 28 m | 41 m | 48 m | 152% | India | 240 m | 376 m | 1057 m | 1417 m | 490% |

| Belgium | 7 m | 9 m | 10 m | 12 m | 71% | China | 400 m | 554 m | 1263 m | 1414 m | 254% |

| Netherlands | 5 m | 10 m | 16 m | 18 m | 260% | Pakistan | 23 m | 38 m | 142 m | 230 m | 900% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yeganeh, H. Conceptualizing the Patterns of Change in Cultural Values: The Paradoxical Effects of Modernization, Demographics, and Globalization. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13090439

Yeganeh H. Conceptualizing the Patterns of Change in Cultural Values: The Paradoxical Effects of Modernization, Demographics, and Globalization. Social Sciences. 2024; 13(9):439. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13090439

Chicago/Turabian StyleYeganeh, Hamid. 2024. "Conceptualizing the Patterns of Change in Cultural Values: The Paradoxical Effects of Modernization, Demographics, and Globalization" Social Sciences 13, no. 9: 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13090439

APA StyleYeganeh, H. (2024). Conceptualizing the Patterns of Change in Cultural Values: The Paradoxical Effects of Modernization, Demographics, and Globalization. Social Sciences, 13(9), 439. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13090439