Hiding the Hate—Contextual Effects on Hate Crime Reports

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical and Empirical Background

2.1. Traces of White Supremacy as the Root Cause

2.2. Advocates of White Supremacy—Right-Wing Hate Groups

3. White Privilege as a Mild Surrogate of White Supremacy

4. Data

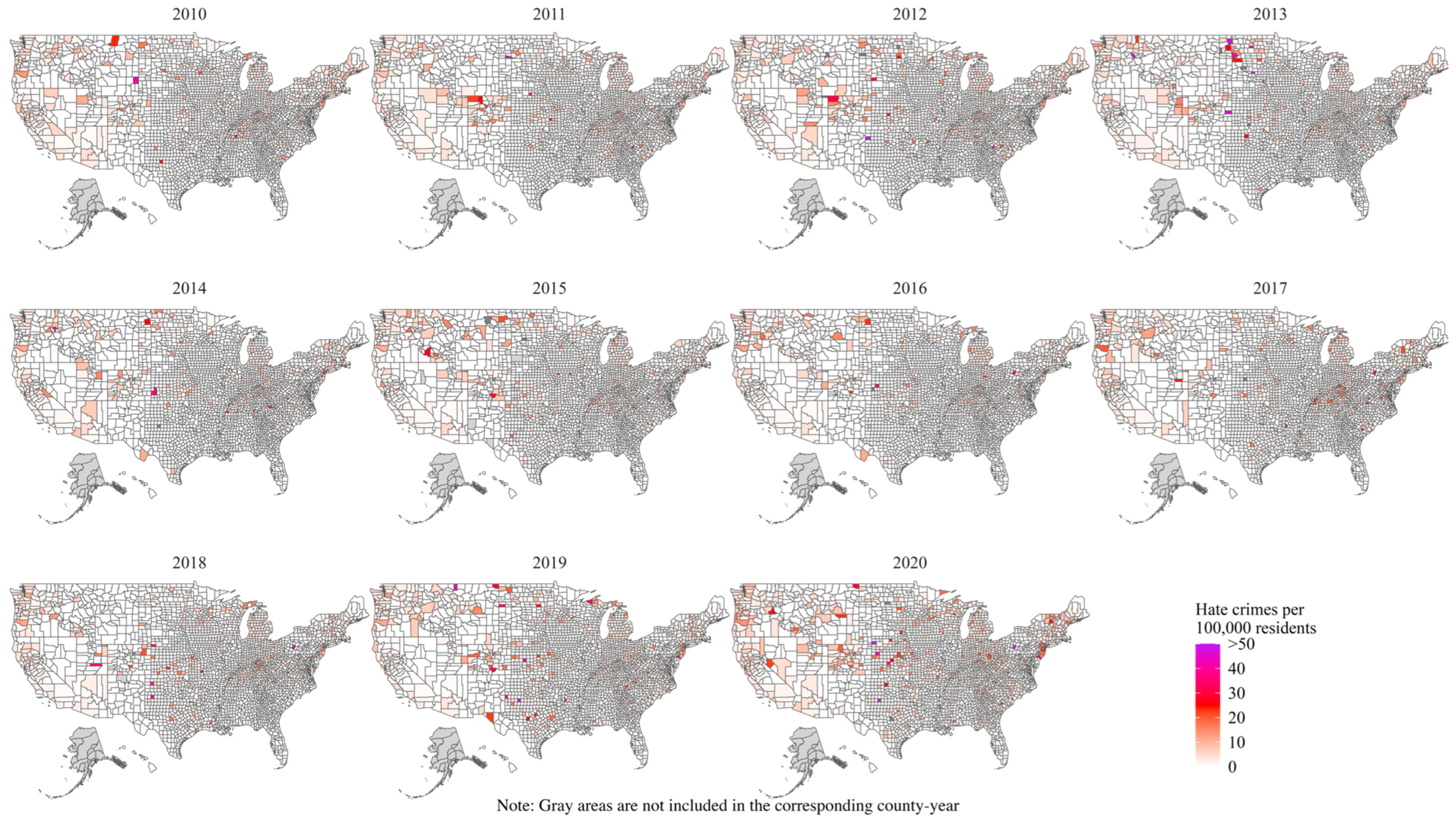

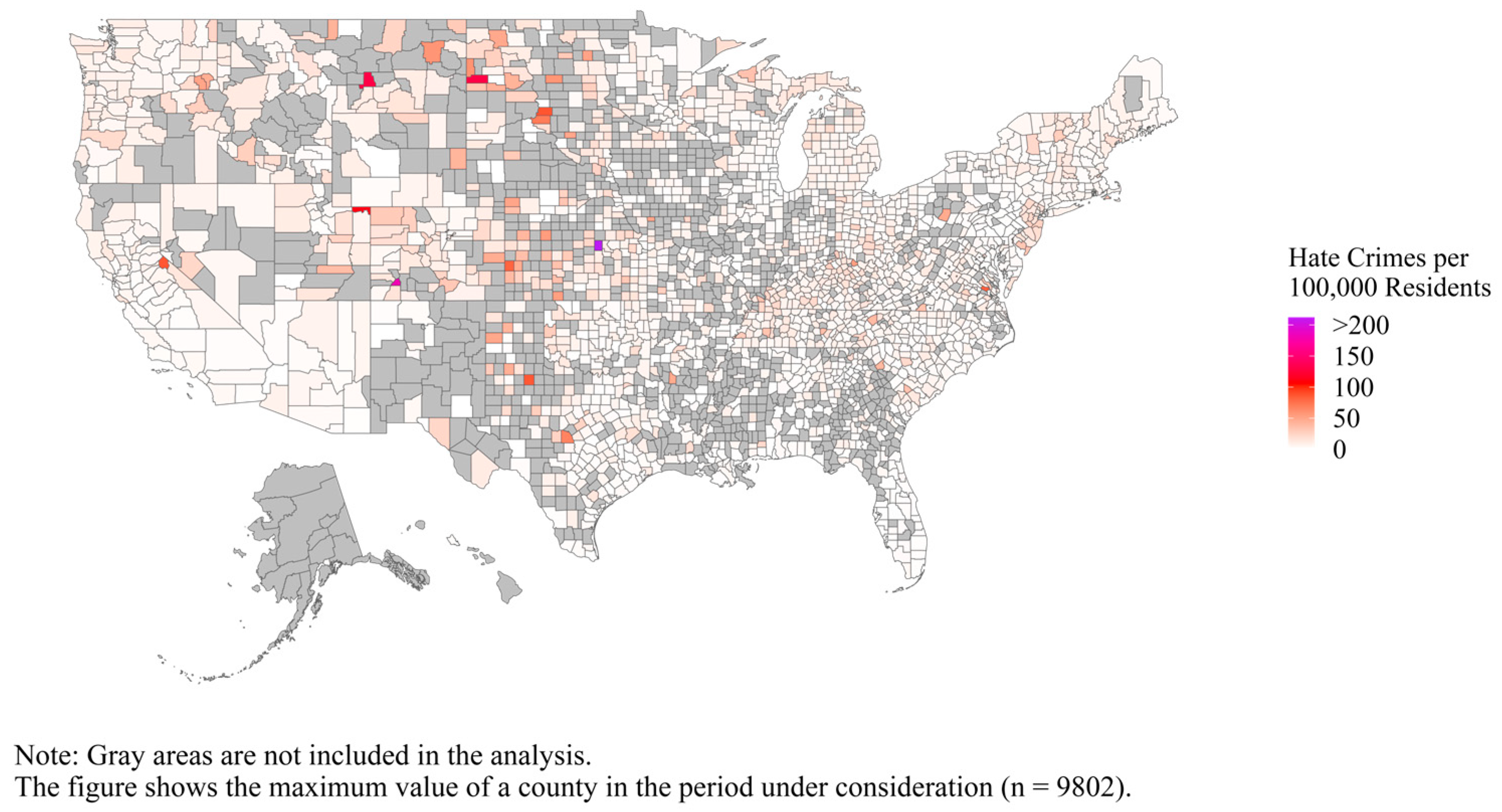

4.1. Dependent Variable

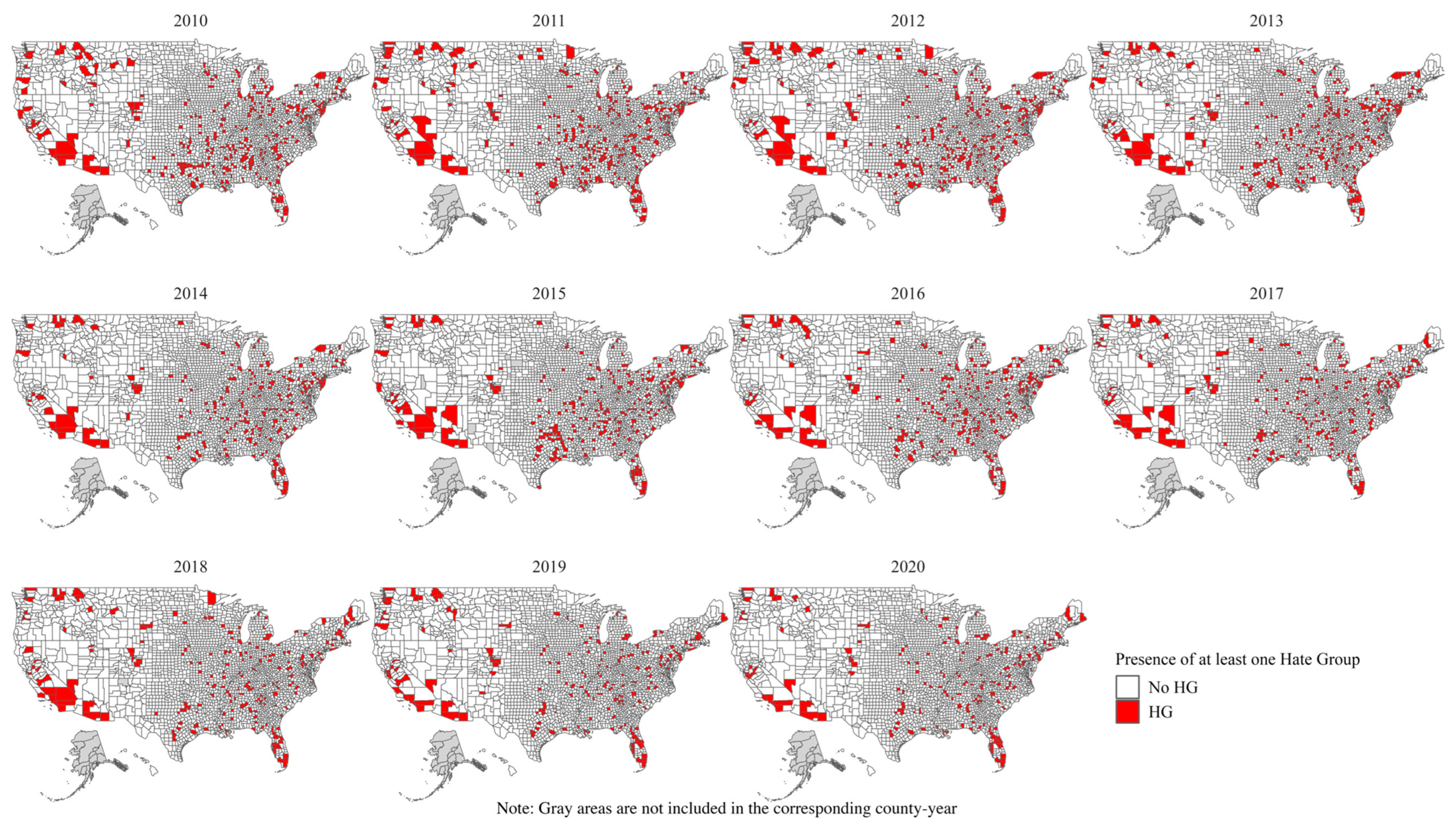

4.2. Independent Variables

5. Method

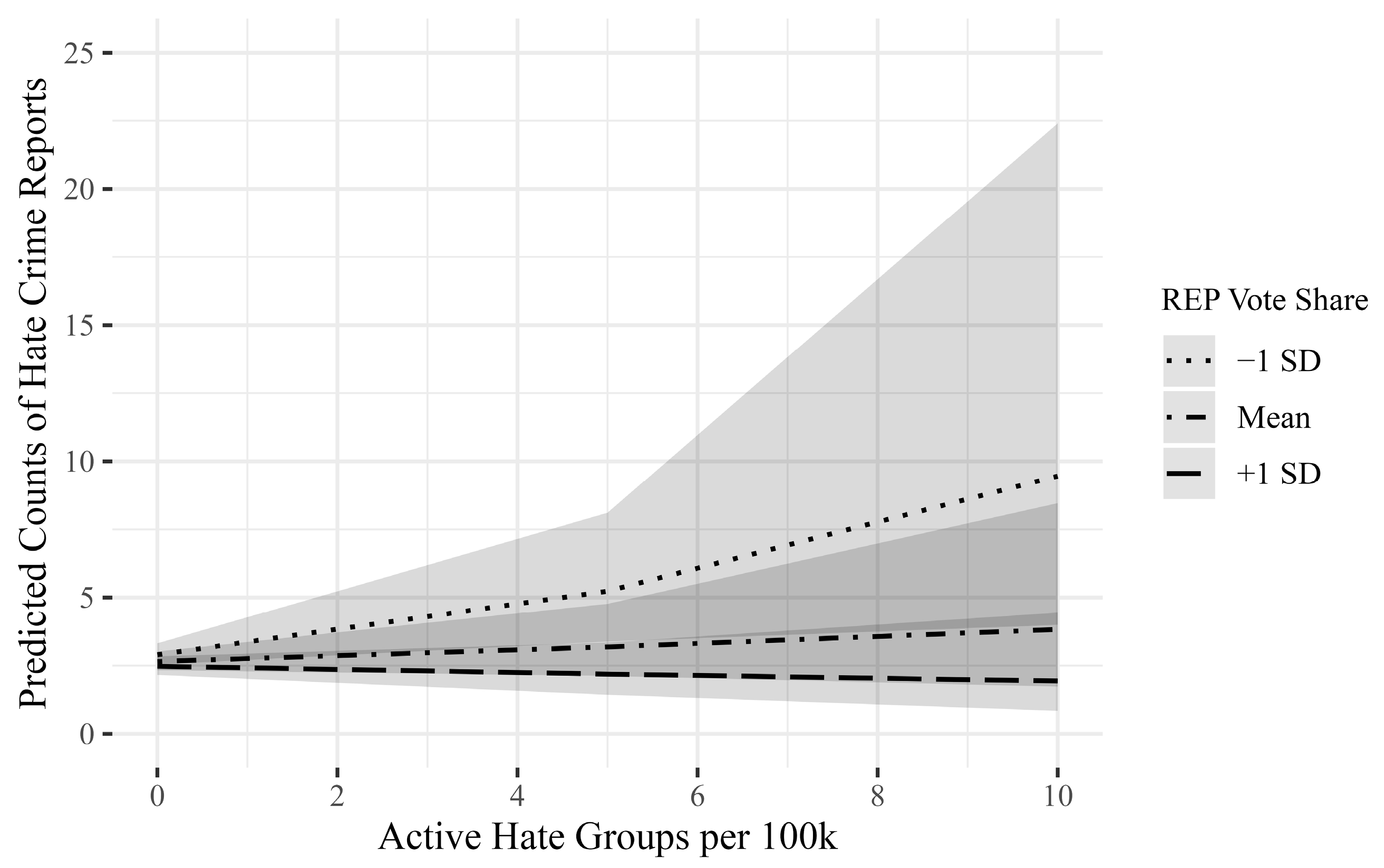

6. Results

7. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | IRR | CI | p | IRR | CI | p | IRR | CI | p | IRR | CI | p |

| Count Model | ||||||||||||

| Active Hate Group | 0.96 | 0.93–0.98 | 0.002 | 1.49 | 1.20–1.86 | <0.001 | 1.07 | 1.01–1.14 | 0.030 | 2.45 | 1.92–3.12 | <0.001 |

| Active Hate Group—spatial lag | 0.94 | 0.88–1.01 | 0.075 | 3.95 | 2.47–6.32 | <0.001 | 1.30 | 1.12–1.51 | 0.001 | 6.37 | 3.80–10.66 | <0.001 |

| Current REP vote log | 0.51 | 0.46–0.57 | <0.001 | 0.54 | 0.49–0.60 | <0.001 | 0.53 | 0.48–0.59 | <0.001 | 0.59 | 0.53–0.66 | <0.001 |

| Crime log | 1.37 | 1.26–1.49 | <0.001 | 1.37 | 1.27–1.49 | <0.001 | 1.34 | 1.24–1.46 | <0.001 | 1.34 | 1.24–1.46 | <0.001 |

| Moved diff. county log | 1.48 | 1.34–1.63 | <0.001 | 1.44 | 1.31–1.59 | <0.001 | 1.49 | 1.35–1.64 | <0.001 | 1.44 | 1.31–1.59 | <0.001 |

| Foreign-born log | 0.92 | 0.85–1.00 | 0.053 | 0.93 | 0.86–1.00 | 0.062 | 0.93 | 0.86–1.00 | 0.062 | 0.93 | 0.86–1.01 | 0.084 |

| White and under 25 years log | 2.48 | 2.05–3.01 | <0.001 | 2.57 | 2.11–3.12 | <0.001 | 2.34 | 1.93–2.84 | <0.001 | 2.41 | 1.98–2.92 | <0.001 |

| Black and under 25 years log | 0.87 | 0.80–0.94 | <0.001 | 0.87 | 0.80–0.94 | <0.001 | 0.88 | 0.81–0.95 | 0.001 | 0.89 | 0.82–0.96 | 0.002 |

| Below poverty line log | 1.25 | 1.07–1.46 | 0.006 | 1.21 | 1.04–1.42 | 0.017 | 1.16 | 0.99–1.36 | 0.065 | 1.09 | 0.93–1.28 | 0.293 |

| Unemployment log | 0.97 | 0.87–1.08 | 0.569 | 0.99 | 0.89–1.10 | 0.828 | 0.96 | 0.86–1.07 | 0.488 | 0.98 | 0.88–1.10 | 0.778 |

| Per capita income log | 1.94 | 1.36–2.75 | <0.001 | 2.11 | 1.49–3.00 | <0.001 | 1.71 | 1.20–2.43 | 0.003 | 1.81 | 1.27–2.58 | 0.001 |

| Edu.—Bachelor or higher log | 2.00 | 1.64–2.43 | <0.001 | 1.85 | 1.53–2.25 | <0.001 | 2.02 | 1.66–2.46 | <0.001 | 1.85 | 1.52–2.25 | <0.001 |

| Region Midwest (Ref.: West) | 0.71 | 0.60–0.85 | <0.001 | 0.70 | 0.59–0.84 | <0.001 | 0.73 | 0.61–0.87 | 0.001 | 0.70 | 0.59–0.84 | <0.001 |

| Region Northeast (Ref.: West) | 0.79 | 0.63–0.98 | 0.032 | 0.78 | 0.62–0.97 | 0.026 | 0.87 | 0.69–1.08 | 0.205 | 0.87 | 0.70–1.09 | 0.216 |

| Region South (Ref.: West) | 0.80 | 0.67–0.96 | 0.018 | 0.81 | 0.67–0.97 | 0.021 | 0.82 | 0.68–0.98 | 0.031 | 0.79 | 0.65–0.95 | 0.012 |

| RUCC 2 (Ref.: RUCC 1) | 0.97 | 0.81–1.16 | 0.742 | 0.97 | 0.81–1.16 | 0.740 | 0.99 | 0.83–1.18 | 0.903 | 1.00 | 0.84–1.20 | 0.980 |

| RUCC 3 (Ref.: RUCC 1) | 1.00 | 0.83–1.21 | 0.989 | 0.99 | 0.82–1.20 | 0.938 | 1.03 | 0.85–1.25 | 0.748 | 1.04 | 0.86–1.26 | 0.680 |

| RUCC 4 (Ref.: RUCC 1) | 1.04 | 0.83–1.29 | 0.753 | 1.02 | 0.82–1.27 | 0.841 | 1.07 | 0.86–1.33 | 0.544 | 1.07 | 0.86–1.33 | 0.542 |

| RUCC 5 (Ref.: RUCC 1) | 1.11 | 0.82–1.49 | 0.500 | 1.08 | 0.80–1.45 | 0.602 | 1.16 | 0.86–1.57 | 0.320 | 1.16 | 0.86–1.56 | 0.330 |

| RUCC 6 (Ref.: RUCC 1) | 1.07 | 0.88–1.30 | 0.495 | 1.04 | 0.86–1.26 | 0.691 | 1.11 | 0.91–1.34 | 0.311 | 1.09 | 0.90–1.32 | 0.393 |

| RUCC 7 (Ref.: RUCC 1) | 1.35 | 1.09–1.67 | 0.005 | 1.31 | 1.06–1.61 | 0.013 | 1.41 | 1.14–1.74 | 0.002 | 1.38 | 1.12–1.71 | 0.003 |

| RUCC 8 (Ref.: RUCC 1) | 1.09 | 0.80–1.49 | 0.582 | 1.06 | 0.78–1.45 | 0.699 | 1.13 | 0.83–1.55 | 0.443 | 1.11 | 0.82–1.52 | 0.496 |

| RUCC 9 (Ref.: RUCC 1) | 1.39 | 1.05–1.85 | 0.021 | 1.35 | 1.02–1.79 | 0.039 | 1.45 | 1.09–1.93 | 0.010 | 1.42 | 1.07–1.89 | 0.015 |

| Active Hate Group × Current REP | 0.88 | 0.83–0.94 | <0.001 | 0.79 | 0.74–0.85 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Active Hate Group—spatial lag × Current REP | 0.66 | 0.58–0.76 | <0.001 | 0.63 | 0.55–0.73 | <0.001 | ||||||

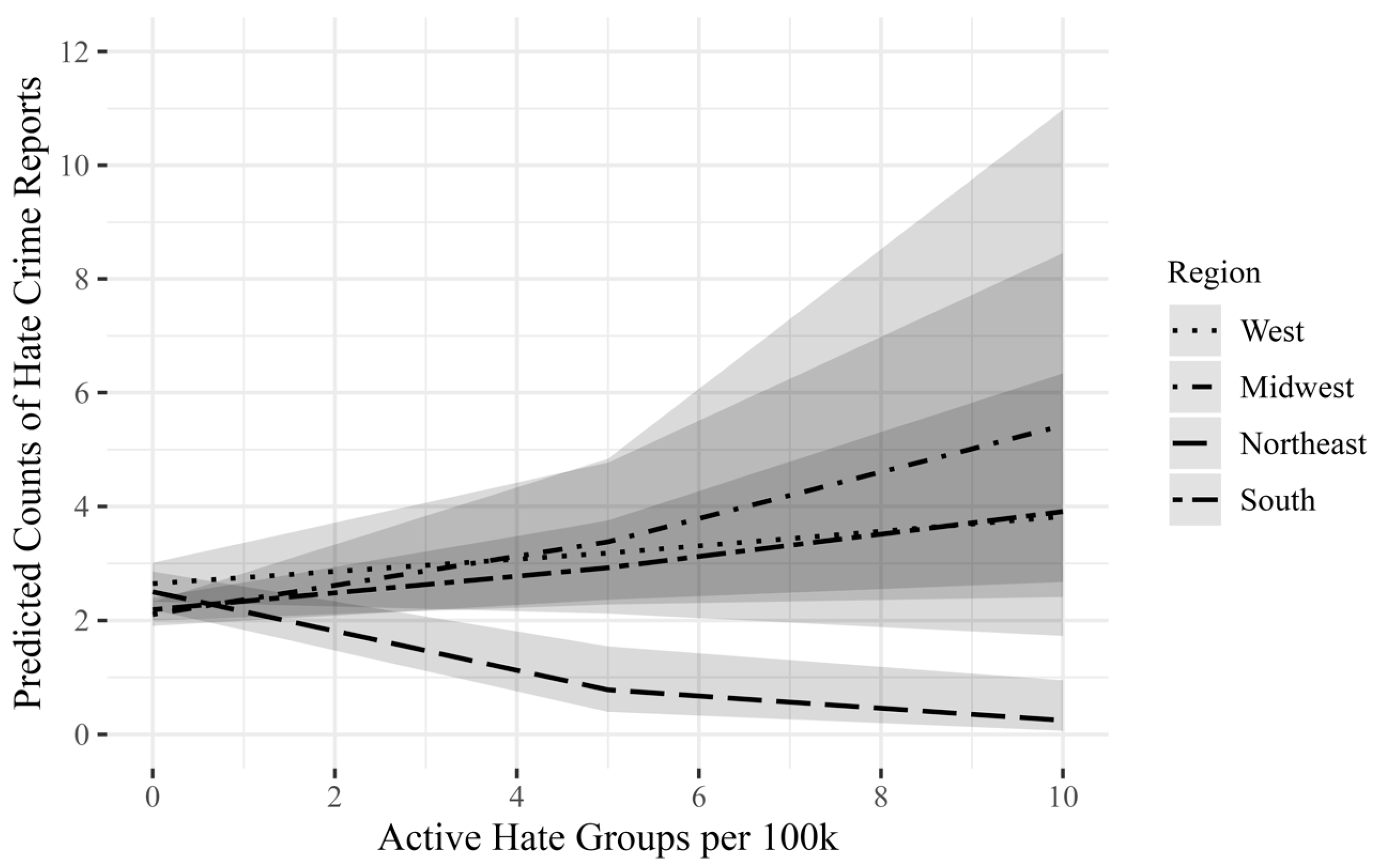

| Active Hate Group × Region Midwest | 1.00 | 0.92–1.08 | 0.916 | 1.04 | 0.95–1.13 | 0.377 | ||||||

| Active Hate Group × Region Northeast | 0.79 | 0.73–0.85 | <0.001 | 0.78 | 0.72–0.84 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Active Hate Group × Region South | 0.98 | 0.90–1.06 | 0.582 | 1.05 | 0.96–1.14 | 0.303 | ||||||

| Active Hate Group—spatial lag × Region Midwest | 0.89 | 0.71–1.12 | 0.313 | 1.00 | 0.79–1.26 | 0.998 | ||||||

| Active Hate Group—spatial lag × Region Northeast | 0.66 | 0.56–0.79 | <0.001 | 0.63 | 0.53–0.76 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Active Hate Group—spatial lag × Region South | 0.76 | 0.61–0.95 | 0.017 | 0.93 | 0.74–1.17 | 0.521 | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.00 | 0.00–0.00 | <0.001 | 0.00 | 0.00–0.00 | <0.001 | 0.00 | 0.00–0.00 | <0.001 | 0.00 | 0.00–0.00 | <0.001 |

| Zero-Inflated Model | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | 1.00 | 0.85–1.18 | 0.972 | 1.00 | 0.85–1.18 | 0.966 | 1.00 | 0.84–1.17 | 0.953 | 1.00 | 0.85–1.18 | 0.979 |

| Population/10,000 log | 0.48 | 0.44–0.51 | <0.001 | 0.48 | 0.44–0.51 | <0.001 | 0.48 | 0.44–0.51 | <0.001 | 0.48 | 0.44–0.51 | <0.001 |

| NCounties | 3114 | 3114 | 3114 | 3114 | ||||||||

| NYears | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | ||||||||

| NObservations | 34180 | 34180 | 34180 | 34180 | ||||||||

| Marginal R2/Conditional R2 | 0.036/0.196 | 0.036/0.195 | 0.034/0.195 | 0.034/0.194 | ||||||||

| AIC | 61,617.86 | 61,548.79 | 61,525.84 | 61,403.23 | ||||||||

| BIC | 61,854.16 | 61,801.98 | 61,812.78 | 61,707.05 | ||||||||

| log-likelihood | −30,780.93 | −30,744.39 | −30,728.92 | −30,665.61 | ||||||||

| 1 | The term “hate crime” is misleading according to McDevitt and Iwama (2016), as there are crimes that are motivated by hate but not by biases. It is therefore more precise to speak of bias-motivated crimes. For simplicity, the term “hate crime” is used throughout the following. |

| 2 | A multitude of theories, such as racial threat (Blalock 1967; Hopkins 2010, pp. 41–42), focus on the social consequences and mechanisms of this phenomenon, which is why there is an immense corpus of scientific research on this topic. |

| 3 | The calculations for the spatial weights were carried out in R using the spdep package (Spatial Dependence: Weighting Schemes, Statistics). |

| 4 | The described methodological procedure was implemented in R using, among others, the glmmTMB package (Brooks et al. 2017). |

| 5 | To test the potential influence of local civil rights groups cited in the literature discussed, I ran an additional model with a dataset limited due to data availability that included civil rights groups but found no significant results to support this argument (see Table S3 in the Supplementary Materials). |

References

- Adamczyk, Amy, Jeff Gruenewald, Steven M. Chermak, and Joshua D. Freilich. 2014. The Relationship Between Hate Groups and Far-Right Ideological Violence. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 30: 310–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, John. 1996. Mapping politics: How context counts in electoral geography. Political Geography 15: 129–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoll, Allison P. 2018. What Makes a Good Neighbor? Race, Place, and Norms of Political Participation. American Political Science Review 112: 494–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Elwood M. 2000. Guess Who’s Coming to Town: White Supremacy, Ethnic Competition, and Social Change. Sociological Focus 33: 153–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, Donald J. 1970. Production of Crime Rates. American Sociological Review 35: 733–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blalock, Hubert M. 1967. Toward a Theory of Minority-Group Relations. New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Blevins, Emily J., and Nathan R. Todd. 2022. Remembering where we’re from: Community- and individual-level predictors of college students’ White privilege awareness. American Journal of Community Psychology 70: 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonds, Anne, and Joshua Inwood. 2016. Beyond white privilege: Geographies of white supremacy and settler colonialism. Progress in Human Geography 40: 715–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, Mollie E., Kasper Kristensen, Koen J. Van Benthem, Arni Magnusson, Casper W. Berg, Anders Nielsen, Hans J. Skaug, Martin Machler, and Benjamin M. Bolker. 2017. glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. The R Journal 9: 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborti, Neil. 2015. Framing the boundaries of hate crime. In The Routledge International Handbook on Hate Crime, 1st ed. London: Routledge, pp. 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chermak, Steven, Joshua Freilich, and Michael Suttmoeller. 2013. The Organizational Dynamics of Far-Right Hate Groups in the United States: Comparing Violent to Nonviolent Organizations. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 36: 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, Robert B., and Melanie R. Trost. 1998. Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In The Handbook of Social Psychology, 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, vols. 1–2, pp. 151–92. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, Cloee. 2019. How a Right-Wing Network Mobilized Sheriffs’ Departments. Political Research Associates. October 6. Available online: https://politicalresearch.org/2019/06/10/how-a-right-wing-network-mobilized-sheriffs-departments (accessed on 27 January 2023).

- Crowder, Kyle, and Scott J. South. 2008. Spatial Dynamics of White Flight: The Effects of Local and Extralocal Racial Conditions on Neighborhood Out-Migration. American Sociological Review 73: 792–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiLorenzo, Matthew. 2021. Trade Layoffs and Hate in the United States. Social Science Quarterly 102: 771–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disha, Ilir, James C. Cavendish, and Ryan D. King. 2011. Historical Events and Spaces of Hate: Hate Crimes against Arabs and Muslims in Post-9/11 America. Social Problems 58: 21–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druckman, James N., Samara Klar, Yanna Krupnikov, Matthew Levendusky, and John Barry Ryan. 2021. Affective polarization, local contexts and public opinion in America. Nature Human Behaviour 5: 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dugan, Laura, and Erica Chenoweth. 2020. Threat, emboldenment, or both? The effects of political power on violent hate crimes*. Criminology 58: 714–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunbar, Edward, Jary Quinones, and Desiree A. Crevecoeur. 2005. Assessment of Hate Crime Offenders: The Role of Bias Intent in Examining Violence Risk. Journal of Forensic Psychology Practice 5: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durso, Rachel M., and David Jacobs. 2013. The Determinants of the Number of White Supremacist Groups: A Pooled Time-Series Analysis. Social Problems 60: 128–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embrick, David G., and Wendy Leo Moore. 2020. White Space(s) and the Reproduction of White Supremacy. American Behavioral Scientist 64: 1935–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferber, Abby L. 1998. Constructing whiteness: The intersections of race and gender in US white supremacist discourse. Ethnic and Racial Studies 21: 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fording, Richard C., and Sanford F. Schram. 2020. Hard White: The Mainstreaming of Racism in American Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goetz, Stephan J., Anil Rupasingha, and Scott Loveridge. 2012. Social Capital, Religion, Wal-Mart, and Hate Groups in America*. Social Science Quarterly 93: 379–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, Danica G., Catherine Y. Chang, and Pamela Havice. 2008. White Racial Identity Statuses as Predictors of White Privilege Awareness. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development 47: 234–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilbron, David C. 1994. Zero-Altered and other Regression Models for Count Data with Added Zeros. Biometrical Journal 36: 531–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, Daniel J. 2010. Politicized Places: Explaining Where and When Immigrants Provoke Local Opposition. American Political Science Review 104: 40–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, Philip N., and Frederic L. Pryor. 1999. On the geography of hate. Economics Letters 65: 389–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jendryke, Michael, and Stephen C. McClure. 2019. Mapping crime—Hate crimes and hate groups in the USA: A spatial analysis with gridded data. Applied Geography 111: 102072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Ryan D. 2007. The Context of Minority Group Threat: Race, Institutions, and Complying with Hate Crime Law. Law & Society Review 41: 189–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Ryan D., Steven F. Messner, and Robert D. Baller. 2009. Contemporary Hate Crimes, Law Enforcement, and the Legacy of Racial Violence. American Sociological Review 74: 291–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitsuse, John I., and Aaron V. Cicourel. 1963. A note on the uses of official statistics. Social Problems 11: 131–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Jack, and Jack McDevitt. 2013. Hate Crimes: The Rising Tide of Bigotry and Bloodshed. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, Jack. 2007. The violence of hate: Confronting racism, anti-Semitism, and other forms of bigotry. In JAB. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Available online: https://tandis.odihr.pl/handle/20.500.12389/19748 (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Lieske, Joel. 2010. The Changing Regional Subcultures of the American States and the Utility of a New Cultural Measure. Political Research Quarterly 63: 538–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Chaeyoon, and Carol Ann MacGregor. 2012. Religion and Volunteering in Context: Disentangling the Contextual Effects of Religion on Voluntary Behavior. American Sociological Review 77: 747–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsitz, George. 2011. How Racism Takes Place. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, William Ming. 2017. White male power and privilege: The relationship between White supremacy and social class. Journal of Counseling Psychology 64: 349–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeys, Tom, Beatrijs Moerkerke, Olivia De Smet, and Ann Buysse. 2012. The analysis of zero-inflated count data: Beyond zero-inflated Poisson regression. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology 65: 163–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcom, Zachary T., and Brendan Lantz. 2021. Hate Crime Victimization and Weapon Use. Criminal Justice and Behavior 48: 1148–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, Gail. 2015. Legislating against hate. In The Routledge International Handbook on Hate Crime, 1st ed. London: Routledge, p. 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masucci, Madeline. 2017. Hate Crime Victimization, 2004–2015; Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice/Bureau of Justice Statistics.

- McCann, Stewart J. H. 2009. Authoritarianism, Conservatism, Racial Diversity Threat, and the State Distribution of Hate Groups. The Journal of Psychology 144: 37–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott, Monica, and Frank L. Samson. 2005. White Racial and Ethnic Identity in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology 31: 245–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDevitt, Jack, and Janice A. Iwama. 2016. Challenges in Measuring and Understanding Hate Crime. In The Handbook of Measurement Issues in Criminology and Criminal Justice. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 131–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDevitt, Jack, Jennifer M. Balboni, Susan Bennett, Joan C. Weiss, Stan Orchowsky, and Lisa Walbolt. 2003. Improving the quality and accuracy of bias crime statistics nationally. In Hate and Bias Crime: A Reader. London: Routledge, pp. 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- McVeigh, Rory, David Cunningham, and Justin Farrell. 2014. Political Polarization as a Social Movement Outcome: 1960s Klan Activism and Its Enduring Impact on Political Realignment in Southern Counties, 1960 to 2000. American Sociological Review 79: 1144–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVeigh, Rory, Michael R. Welch, and Thoroddur Bjarnason. 2003. Hate Crime Reporting as a Successful Social Movement Outcome. American Sociological Review 68: 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, Richard M., Emily Nicolosi, Simon Brewer, and Andrew M. Linke. 2018. Geographies of Organized Hate in America: A Regional Analysis. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 108: 1006–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIT Election Data and Science Lab. 2022. County Presidential Election Returns 2000–2020. Available online: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/VOQCHQ (accessed on 25 June 2022).

- Morris, Aldon. 2022. Alternative View of Modernity: The Subaltern Speaks. American Sociological Review 87: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulholland, Sean E. 2010. Hate Fuel: On the Relationship Between Local Government Policy and Hate Group Activity. Eastern Economic Journal 36: 480–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mulholland, Sean E. 2013. White supremacist groups and hate crime. Public Choice 157: 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, Deborah, and Duncan Temple Lang. 2015. Data Science in R: A Case Studies Approach to Computational Reasoning and Problem Solving. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Christopher Sebastian, and Christopher C. Towler. 2019. Race and Authoritarianism in American Politics. Annual Review of Political Science 22: 503–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, Barbara J. 1998. Defenders of the faith: Hate groups and ideologies of power in the United States. Patterns of Prejudice 32: 32–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, Barbara J. 2001. In the Name of Hate: Understanding Hate Crimes. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, Barbara J. 2010. Counting—And Countering—Hate Crime in Europe. European Journal of Crime, Criminal Law and Criminal Justice 18: 349–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatkowska, Sylwia J., Steven F. Messner, and Tse-Chuan Yang. 2018. Understanding the Relationship Between Relative Group Size and Hate Crime Rates: Linking Methods with Concepts. Justice Quarterly 36: 1072–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, Laura. 2015. Geographies of race and ethnicity 1: White supremacy vs white privilege in environmental racism research. Progress in Human Geography 39: 809–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reny, Tyler T., Loren Collingwood, and Ali A. Valenzuela. 2019. Vote Switching in the 2016 Election: How Racial and Immigration Attitudes, Not Economics, Explain Shifts in White Voting. Public Opinion Quarterly 83: 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, Joel Michael. 2022. Disability and White Supremacy. Critical Philosophy of Race 10: 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Matt E., and Peter T. Leeson. 2011. Hate groups and hate crime. International Review of Law and Economics 31: 256–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simi, Pete, Kathleen Blee, Matthew DeMichele, and Steven Windisch. 2017. Addicted to Hate: Identity Residual among Former White Supremacists. American Sociological Review 82: 1167–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southern Poverty Law Center. 2023a. Frequently Asked Questions about Hate Groups. Available online: https://www.splcenter.org/20200318/frequently-asked-questions-about-hate-groups (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Southern Poverty Law Center. 2023b. Hate Map. Available online: https://www.splcenter.org/hate-map (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- Southern Poverty Law Center. 2024. General Hate. Available online: https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/ideology/general-hate (accessed on 29 August 2024).

- Stipak, Brian, and Carl Hensler. 1982. Statistical Inference in Contextual Analysis. American Journal of Political Science 26: 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tankard, Margaret E., and Elizabeth Levy Paluck. 2016. Norm Perception as a Vehicle for Social Change: Vehicle for Social Change. Social Issues and Policy Review 10: 181–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Census Bureau. 2023. American Community Survey (ACS). Census.Gov. January 20. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- US Department of Justice. 2022. Facts and Statistics. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/hatecrimes/hate-crime-statistics (accessed on 19 January 2023).

- US Department of Justice. 2023. Learn About Hate Crimes|HATECRIMES|Department of Justice. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/hatecrimes/learn-about-hate-crimes (accessed on 20 January 2023).

- van Kirk, Amy, and Jessica P. Hodge. 2016. Hate Crimes and Hate Crime Law. In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, Amanda, and Ariel Zellman. 2022. Mobilizing the White: White Nationalism and Congressional Politics in the American South. American Politics Research 50: 707–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingher, Joshua N. 2018. Polarization, Demographic Change, and White Flight from the Democratic Party. The Journal of Politics 80: 860–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hate crimes 1 | 5.91 | 18.40 | 0 | 374 |

| Active hate groups per 100k | 0.15 | 0.71 | 0.00 | 26.86 |

| Active hate groups—spatial lag 1 | 0.26 | 0.51 | 0.00 | 6.50 |

| Crimes | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.00 | 1.85 |

| Current REP vote | 3.99 | 0.32 | 1.66 | 4.55 |

| Moved within state | 1.53 | 0.38 | 0.00 | 3.15 |

| Foreign-born | 1.75 | 0.76 | 0.00 | 4.00 |

| White and u25 | 3.23 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 4.11 |

| Black and u25 | 1.11 | 0.81 | 0.00 | 3.44 |

| Below poverty line | 2.69 | 0.36 | 1.30 | 3.94 |

| Unemployment | 2.05 | 0.35 | 0.00 | 3.27 |

| Income and education index | 1.10 | 0.28 | 0.14 | 2.13 |

| Region: West 1 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0 | 1 |

| Region: Midwest 1 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0 | 1 |

| Region: Northeast 1,2 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0 | 1 |

| Region: South 1 | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 |

| Population 1 | 256,690 | 552,105.8 | 552 | 10,105,722 |

| n | 9802 | |||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | IRR | SE | IRR | SE | IRR | SE | IRR | SE |

| Active hate groups per 100k | 1.02 | 0.02 | 2.13 *** | 0.46 | 1.04 | 0.04 | 3.00 *** | 0.68 |

| Active hate groups— | 0.94 * | 0.02 | 1.62 * | 0.32 | 0.97 | 0.04 | 1.64 * | 0.35 |

| spatial lag | ||||||||

| Current REP vote log | 0.69 *** | 0.05 | 0.78 ** | 0.06 | 0.69 *** | 0.05 | 0.78 ** | 0.06 |

| Crime log | 1.14 ** | 0.05 | 1.14 ** | 0.05 | 1.13 ** | 0.05 | 1.14 ** | 0.05 |

| Moved diff. county log | 1.46 *** | 0.07 | 1.46 *** | 0.07 | 1.45 *** | 0.07 | 1.46 *** | 0.07 |

| Foreign-born log | 0.76 *** | 0.03 | 0.77 *** | 0.03 | 0.76 *** | 0.03 | 0.77 *** | 0.03 |

| White and under 25 years log | 0.90 | 0.08 | 0.89 | 0.08 | 0.91 | 0.08 | 0.90 | 0.08 |

| Black and under 25 years log | 0.72 *** | 0.02 | 0.72 *** | 0.02 | 0.72 *** | 0.02 | 0.72 *** | 0.02 |

| Below poverty line log | 1.21 ** | 0.09 | 1.21 ** | 0.09 | 1.20 * | 0.09 | 1.19 * | 0.09 |

| Unemployment log | 0.66 *** | 0.04 | 0.67 *** | 0.04 | 0.66 *** | 0.04 | 0.67 *** | 0.04 |

| Income and education index log | 0.74 ** | 0.08 | 0.75 * | 0.09 | 0.73 ** | 0.08 | 0.74 ** | 0.08 |

| Region: Midwest (Ref.: West) | 0.82 ** | 0.06 | 0.81 ** | 0.06 | 0.83 * | 0.06 | 0.83 ** | 0.06 |

| Region: Northeast (Ref.: West) | 0.91 | 0.07 | 0.91 | 0.07 | 0.93 | 0.08 | 0.96 | 0.08 |

| Region: South (Ref.: West) | 0.84 * | 0.06 | 0.83 ** | 0.06 | 0.84 * | 0.06 | 0.84 * | 0.06 |

| Hate groups × Current REP | 0.84 *** | 0.04 | 0.77 *** | 0.04 | ||||

| Hate groups—spatial lag × Current REP | 0.86 ** | 0.05 | 0.87 * | 0.05 | ||||

| Hate groups × Midwest | 1.02 | 0.05 | 1.06 | 0.06 | ||||

| Hate groups × Northeast | 0.84 * | 0.07 | 0.77 *** | 0.06 | ||||

| Hate groups × South | 0.99 | 0.05 | 1.02 | 0.05 | ||||

| Hate groups—spatial lag | 0.86 | 0.08 | 0.86 | 0.08 | ||||

| × Midwest | ||||||||

| Hate groups—spatial lag | 0.99 | 0.06 | 0.96 | 0.06 | ||||

| × Northeast | ||||||||

| Hate groups—spatial lag | 1.01 | 0.07 | 0.96 | 0.07 | ||||

| × South | ||||||||

| Marginal pseudo R2 | 0.082 | 0.084 | 0.083 | 0.084 | ||||

| Conditional pseudo R2 | 0.270 | 0.269 | 0.271 | 0.270 | ||||

| AIC | 41,402.8 | 41,382.6 | 41,404.6 | 41,373.7 | ||||

| BIC | 41,532.2 | 41,526.4 | 41,577.1 | 41,560.7 | ||||

| log-likelihood | −20,683.4 | −20,671.3 | −20,678.3 | −20,660.9 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Küchler, A.C.D. Hiding the Hate—Contextual Effects on Hate Crime Reports. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13090466

Küchler ACD. Hiding the Hate—Contextual Effects on Hate Crime Reports. Social Sciences. 2024; 13(9):466. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13090466

Chicago/Turabian StyleKüchler, Armin C. D. 2024. "Hiding the Hate—Contextual Effects on Hate Crime Reports" Social Sciences 13, no. 9: 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13090466

APA StyleKüchler, A. C. D. (2024). Hiding the Hate—Contextual Effects on Hate Crime Reports. Social Sciences, 13(9), 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13090466