A Control Theory Approach to Understanding the Dynamics of Cognitive Wellbeing

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Conceptual Delimitations

- Perception of life circumstances and events;

- Affective reactions to those events;

- Recall of past experiences;

- Integrative evaluation about one’s life as a whole.

- Goals—defined as internal representations of desired outcomes of one’s behavior—can vary in what concerns their content, importance, and the motivation behind pursuing them, but they certainly influence the SWB (Kasser and Ryan 1993; Brdar et al. 2009).

- Hope, defined as the cognitive and motivational capacity to devise and pursue meaningful pathways to desired goals—is a critical determinant of subjective wellbeing because it enhances emotional resilience, fosters positive affect, and ultimately elevates life satisfaction (Pleeging et al. 2021).

- Desires are defined (Crawford Solberg et al. 2002) as personally significant goals or expressed wishes that are chronically accessible and central to life satisfaction. The link between desires and satisfaction lies in “desire discrepancy”, where dissatisfaction occurs when one’s possessions or circumstances do not align with their desires. If desires are unmet, life satisfaction tends to decrease, whereas when desires align closely with reality, satisfaction increases.

- Affective forecasting is defined as the process by which individuals predict their future emotional states in response to anticipated events, including estimations of the valence, intensity, and duration of their feelings. Research by Wilson and Gilbert (2003), Bertoni and Corazzini (2018), and many others indicates that people often misjudge these future affective responses—typically overestimating both the intensity and the persistence of their emotions, and such forecasting errors can significantly impact subjective wellbeing by influencing decision-making and goal-setting. When individuals base major life choices on inaccurate predictions of happiness or distress, the resulting discrepancy between expected and experienced emotions may lead to lower life satisfaction.

- Time perspective. Since all human experiences are processed within a temporal framework, appraisals of one’s own quality of life are also influenced by the individual time perspective. Zimbardo and Boyd (1999, p. 18) defined time perspective as “the often nonconscious process whereby the continual flows of personal and social experiences are assigned to temporal categories, or time frames, that help to give order, coherence, and meaning to those events”. Numerous studies explored the connections between time perspective and subjective wellbeing. A recent meta-analysis of these studies (Diaconu-Gherasim et al. 2023, p. 1) found that “a present hedonist time perspective had positive relations with life satisfaction, happiness, and positive affects. The future time perspective was linked to higher levels of positive indicators of well-being and lower levels of negative indicators”. On the contrary, the present fatalistic time perspective and the deviation from the balanced time perspective are negatively correlated with wellbeing.

1.2. The Dual Cognitive–Affective Nature of SWB

1.3. Brief Overview of the Ideas on the Dynamics of SWB

- The actual control mechanisms involved in the stability of SWB are not sufficiently explained. The concept of “SWB buffers” used in (Cummins 2010) is rather elusive.

- These theories do not explain the individual differences in the adaptive response time of the control loop of SWB.

- The stability of SWB may be the result of multiple control loops, with multiple set points.

- Set points do not necessarily correspond to hedonic neutrality, but tend to be, on average, positive.

- Finally, these theories do not explain the lasting positive effects on SWB obtained, for example, through positive psychology interventions (PPIs) (Bolier et al. 2013).

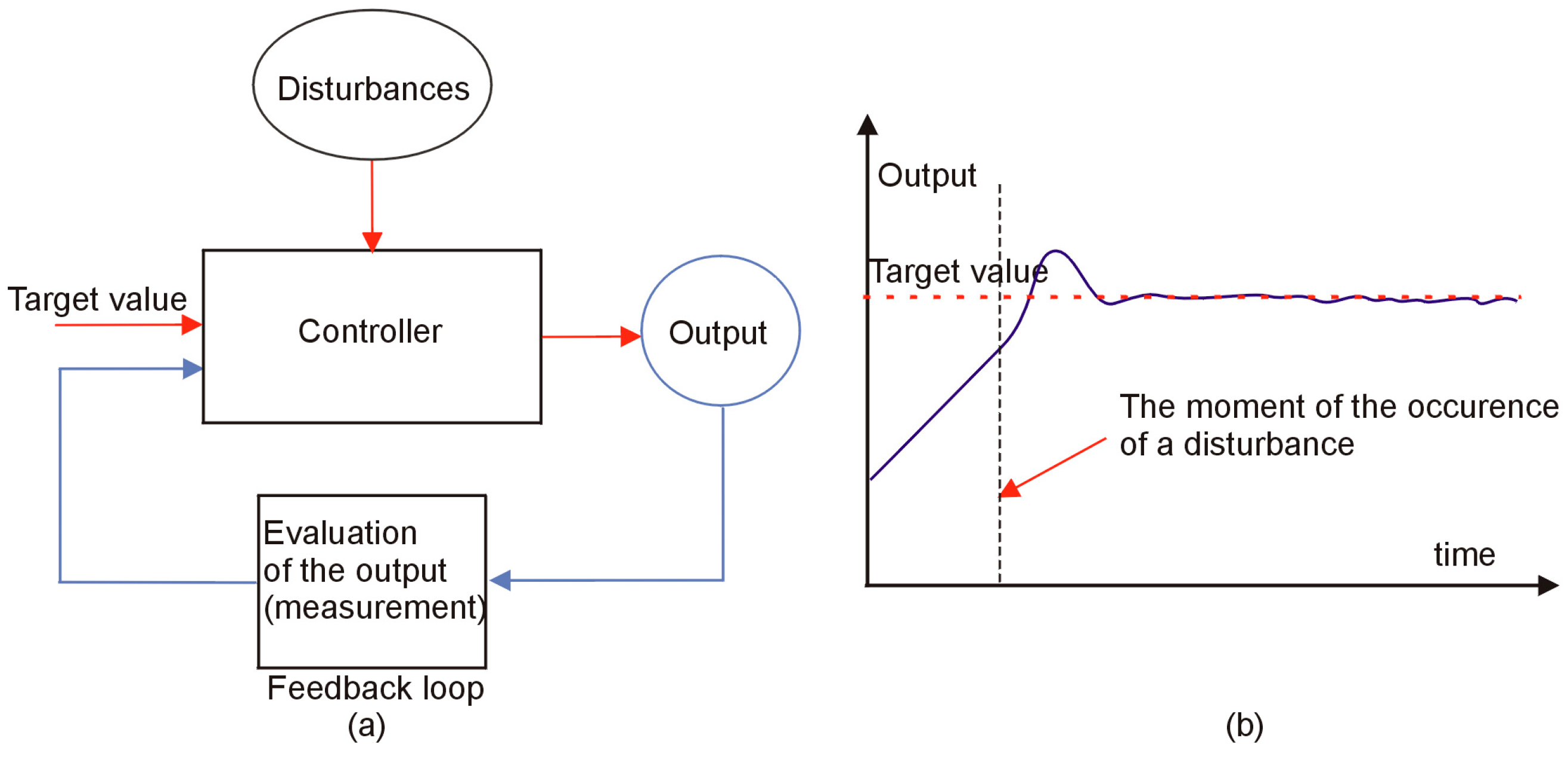

2. Towards a Model of CWB Based on Feedback Control

2.1. Control Theory as a Framework for Understanding the Dynamics of SWB

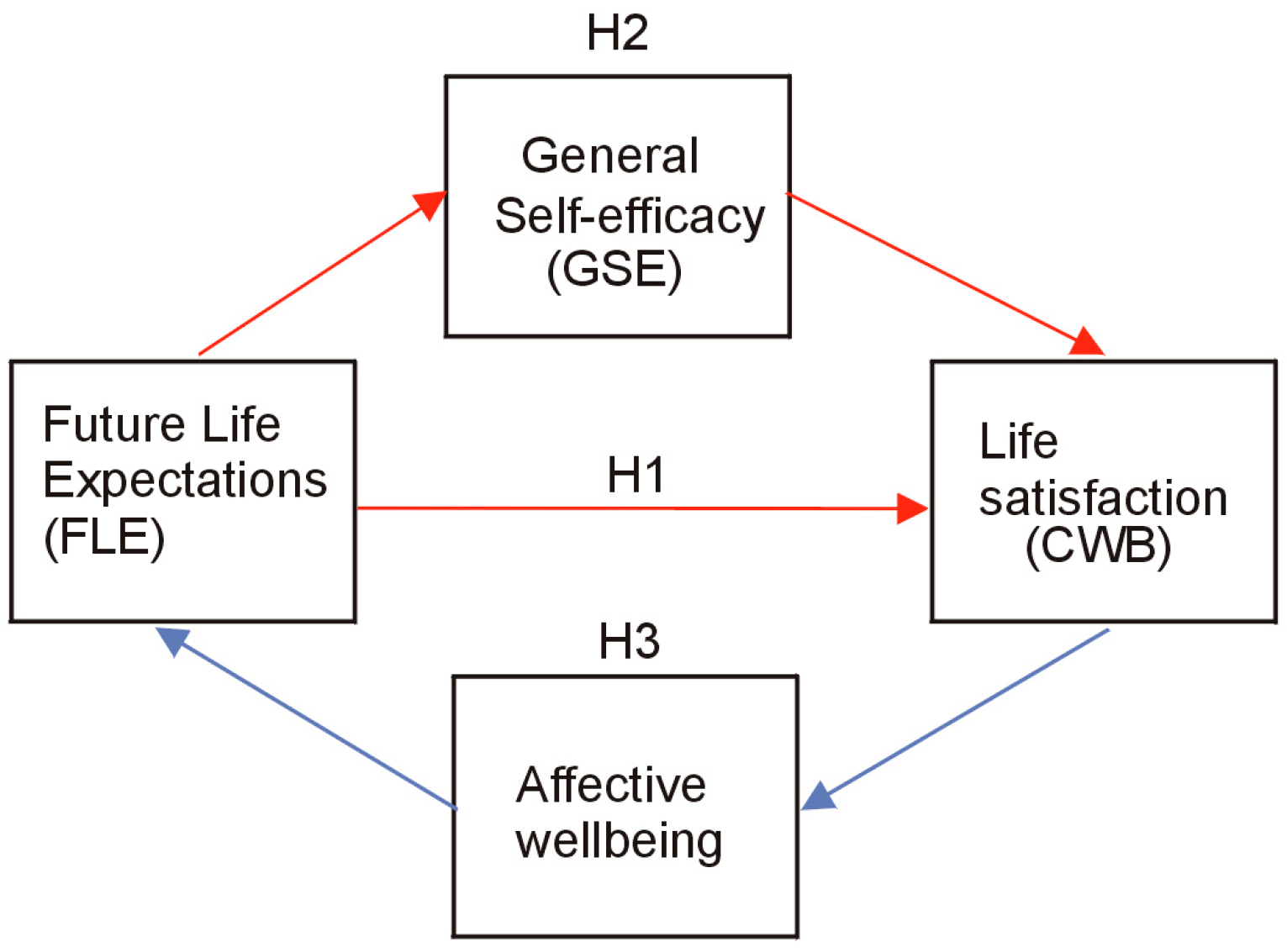

2.2. Building Hypotheses

- SWB is not a state but a process of continuous adjustments (Kim-Prieto et al. 2005).

- The process of adjustment of the SWB towards the target value is not entirely unconscious. People can and do set conscious goals, actively make decisions, and adjust behavior in order to reach these goals (Hitlin and Kirkpatrick Johnson 2015).

- Though AWB and CWB are strongly correlated, they are distinct constructs (Luhmann et al. 2012a) and their distinct levels of stability are due to the existence of distinct feedback control loops. While the set point of the control loop for AWB seems to be genetically determined (Cummins 2010), we hypothesize that the control loop for CWB follows a different target value, which is individual and may change with time.

3. Method

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Instruments

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Items of the Future Life Expectations Scale References

- I will have a happy family.

- I will have many close friends.

- I will have a home just the way I want.

- I will have a job where I will do something I like.

- I will be involved and appreciated by the community I live in.

- I will continue to study and improve myself professionally, or in other areas that interest me.

- I will have a fully satisfactory financial situation.

References

- Alkhatib, Maha Ahmed Hussein. 2020. Investigate the Relation between Psychological Well-Being, Self-Efficacy and Positive Thinking at Prince Sattam Bin Abdul Aziz University Students. IJHE 9: 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, Fay, Marcus Henning, Fiona Moir, and Chris Krägeloh. 2024. A Structural Equation Model Analysis of the Relationships between Career Indecision, Sense of Control, Self-Efficacy, Rumination and Depression in High School Students. Discover Psychology 4: 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, James. 2011. IBM SPSS Amos 20 User’s Guide. New York: Amos Development Corporation, SPSS Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Azizli, Nicole, Breanna E. Atkinson, Holly M. Baughman, and Erica A. Giammarco. 2015. Relationships between General Self-Efficacy, Planning for the Future, and Life Satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences 82: 58–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, Albert. 1977. Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review 84: 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertoni, Marco, and Luca Corazzini. 2018. Asymmetric Affective Forecasting Errors and Their Correlation with Subjective Well-Being. PLoS ONE 13: e0192941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolier, Linda, Merel Haverman, Gerben J. Westerhof, Heleen Riper, Filip Smit, and Ernst Bohlmeijer. 2013. Positive Psychology Interventions: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Studies. BMC Public Health 13: 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brdar, Ingrid, Majda Rijavec, and Dubravka Miljković. 2009. Life Goals and Well-Being: Are Extrinsic Aspirations Always Detrimental to Well-Being? Psihologijske Teme 18: 317–34. [Google Scholar]

- Brickman, Philip. 1971. Hedonic Relativism and Planning the Good Society. In Adaptation Level Theory: A symposium. Edited by Mortimer H. Appley. New York: Academic Press, pp. 287–301. [Google Scholar]

- Buecker, Susanne, Maike Luhmann, Peter Haehner, Janina Larissa Bühler, Laura C. Dapp, Eva C. Luciano, and Ulrich Orth. 2023. The Development of Subjective Well-Being across the Life Span: A Meta-Analytic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Psychological Bulletin 149: 418–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Barbara M. 2013. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Carey, Timothy A., Margaret Carey, Richard J. Mullan, Christopher G. Spratt, and Margaret B. Spratt. 2009. Assessing the Statistical and Personal Significance of the Method of Levels. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy 37: 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, Alan, Katie Cullen, Cora Keeney, Ciaran Canning, Olwyn Mooney, Ellen Chinseallaigh, and Annie O’Dowd. 2021. Effectiveness of Positive Psychology Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology 16: 749–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, Alba, Maria Rubio-Aparicio, Guadalupe Molinari, Ángel Enrique, Julio Sánchez-Meca, and Rosa M. Baños. 2019. Effects of the Best Possible Self Intervention: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 14: e0222386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, Charles S., and Michael F. Scheier. 1982. Control Theory: A Useful Conceptual Framework for Personality–Social, Clinical, and Health Psychology. Psychological Bulletin 92: 111–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattelino, Elena, Silvia Testa, Emanuela Calandri, Angela Fedi, Silvia Gattino, Federica Graziano, Chiara Rollero, and Tatiana Begotti. 2023. Self-Efficacy, Subjective Well-Being and Positive Coping in Adolescents with Regard to COVID-19 Lockdown. Current Psychology 42: 17304–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Gilad, Stanley M. Gully, and Dov Eden. 2001. Validation of a New General Self-Efficacy Scale. Organizational Research Methods 4: 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Gilad, Stanley M. Gully, and Dov Eden. 2004. General Self-efficacy and Self-esteem: Toward Theoretical and Empirical Distinction between Correlated Self-evaluations. Journal of Organizational Behavior 25: 375–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopik, William J., Jeewon Oh, Eric S. Kim, Ted Schwaba, Michael D. Krämer, David Richter, and Jacqui Smith. 2020. Changes in Optimism and Pessimism in Response to Life Events: Evidence from Three Large Panel Studies. Journal of Research in Personality 88: 103985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford Solberg, Emily, Ed Diener, Derrik Wirtz, Rrichard E. Lucas, and Shigehiro Oishi. 2002. Wanting, Having, and Satisfaction: Examining the Role of Desire Discrepancies in Satisfaction with Income. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83: 725–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, Robert A. 1995. On the Trail of the Gold Standard for Subjective Well-Being. Social Indicators Research 35: 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, Robert A. 2010. Subjective Wellbeing, Homeostatically Protected Mood and Depression: A Synthesis. Journal of Happiness Studies 11: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, Robert A. 2014. Can Happiness Change? Theories and Evidence. In Stability of Happiness. Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 75–97. Available online: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780124114784000059 (accessed on 23 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Cummins, Robert A., Anna L. D. Lau, and Melanie T. Davern. 2012. Subjective Wellbeing Homeostasis. In Handbook of Social Indicators and Quality of Life Research. Edited by Kenneth C. Land, Alex C. Michalos and Sirgy M. Joseph. Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 79–98. ISBN 978-94-007-2420-4. [Google Scholar]

- Das, Kirti V., Carla Jones-Harrell, Yingling Fan, Anu Ramaswami, Ben Orlove, and Nisha Botchwey. 2020. Understanding Subjective Well-Being: Perspectives from Psychology and Public Health. Public Health Reviews 41: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaconu-Gherasim, Loredana R., Cristina R. Mardari, and Cornelia Măirean. 2023. The Relation between Time Perspectives and Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis on Research. Current Psychology 42: 5951–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, Richard E. Lucas, and Christie Napa Scollon. 2009. Beyond the Hedonic Treadmill: Revising the Adaptation Theory of Well-Being. In The Science of Well-Being. Edited by Diener Ed. Social Indicators Research Series; Dordrecht: Springer, vol. 37, pp. 103–18. ISBN 978-90-481-2349-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, Satoshi Kanazawa, Eunkook M. Suh, and Shigehiro Oishi. 2015. Why People Are in a Generally Good Mood. Personality and Social Psychology Review 19: 235–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, Ed, Shigehiro Oishi, and Louis Tay. 2018. Advances in Subjective Well-Being Research. Nature Human Behaviour 2: 253–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, Weiting Ng, James Harter, and Raksha Arora. 2010. Wealth and Happiness across the World: Material Prosperity Predicts Life Evaluation, Whereas Psychosocial Prosperity Predicts Positive Feeling. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 99: 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, Rachel, Annette Daly, Jan Huyton, and Lalage Sanders. 2012. The challenge of defining wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing 2: 222–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, Michael, and Ed Diener. 2004. Global Judgments of Subjective Well-Being: Situational Variability and Long-Term Stability. Social Indicators Research 65: 245–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, Jane, Chris Keyworth, and Mary P. Tully. 2018. If No-One Stops Me, I’ll Make the Mistake Again’: Changing Prescribing Behaviours through Feedback; A Perceptual Control Theory Perspective. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 14: 241–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fors Connolly, Filip, and Tommy Gärling. 2024. What Distinguishes Life Satisfaction from Emotional Wellbeing? Frontiers in Psychology 15: 1434373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, Matthew W., Laura J. Long, and Colleen A. Phillips. 2020. Hope, Optimism, Self-efficacy, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Meta-analytic Review of the Protective Effects of Positive Expectancies. Journal of Clinical Psychology 76: 329–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Yiqun. 2020. Happy People Live Longer and Better: Advances in Research on Subjective Well-Being. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 12: 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, Paul. 2015. Happiness and Education: Troubling Students for Their Own Contentment. Time & Society 24: 54–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2017. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Headey, Bruce. 2007. The Set-Point Theory of Well-Being: Negative Results and Consequent Revisions. Social Indicators Research 85: 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headey, Bruce. 2010. The Set Point Theory of Well-Being Has Serious Flaws: On the Eve of a Scientific Revolution? Social Indicators Research 97: 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headey, Bruce, and Alexander James Wearing. 1992. Understanding Happiness: A Theory of Subjective Well-Being. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire. [Google Scholar]

- Hitlin, Steven, and Monica Kirkpatrick Johnson. 2015. Reconceptualizing Agency within the Life Course: The Power of Looking Ahead. American Journal of Sociology 120: 1429–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Li-Tze, and Peter M. Bentler. 1995. Evaluating model fit. In Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Edited by Rick H. Hoyle. Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 76–99. [Google Scholar]

- International Wellbeing Group. 2013. Personal Wellbeing Index. Geelong: Australian Centre on Quality of Life, Deakin University. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Angus Deaton. 2010. High Income Improves Evaluation of Life but Not Emotional Well-Being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107: 16489–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karademas, Evangelos C. 2006. Self-Efficacy, Social Support and Well-Being. Personality and Individual Differences 40: 1281–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karademas, Evangelos C., Konstantinos Kafetsios, and Georgios D. Sideridis. 2007. Optimism, Self-efficacy and Information Processing of Threat- and Well-being-related Stimuli. Stress and Health 23: 285–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasser, Tim, and Richard M. Ryan. 1993. A Dark Side of the American Dream: Correlates of Financial Success as a Central Life Aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 65: 410–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasser, Tim, and Richard M. Ryan. 2001. Be careful what you wish for: Optimal functioning and the relative attainment of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. In Life Goals and Well-Being. Edited by Peter Schmuck and Kennon Sheldon. Gottingen: Hogrefe, pp. 116–31. [Google Scholar]

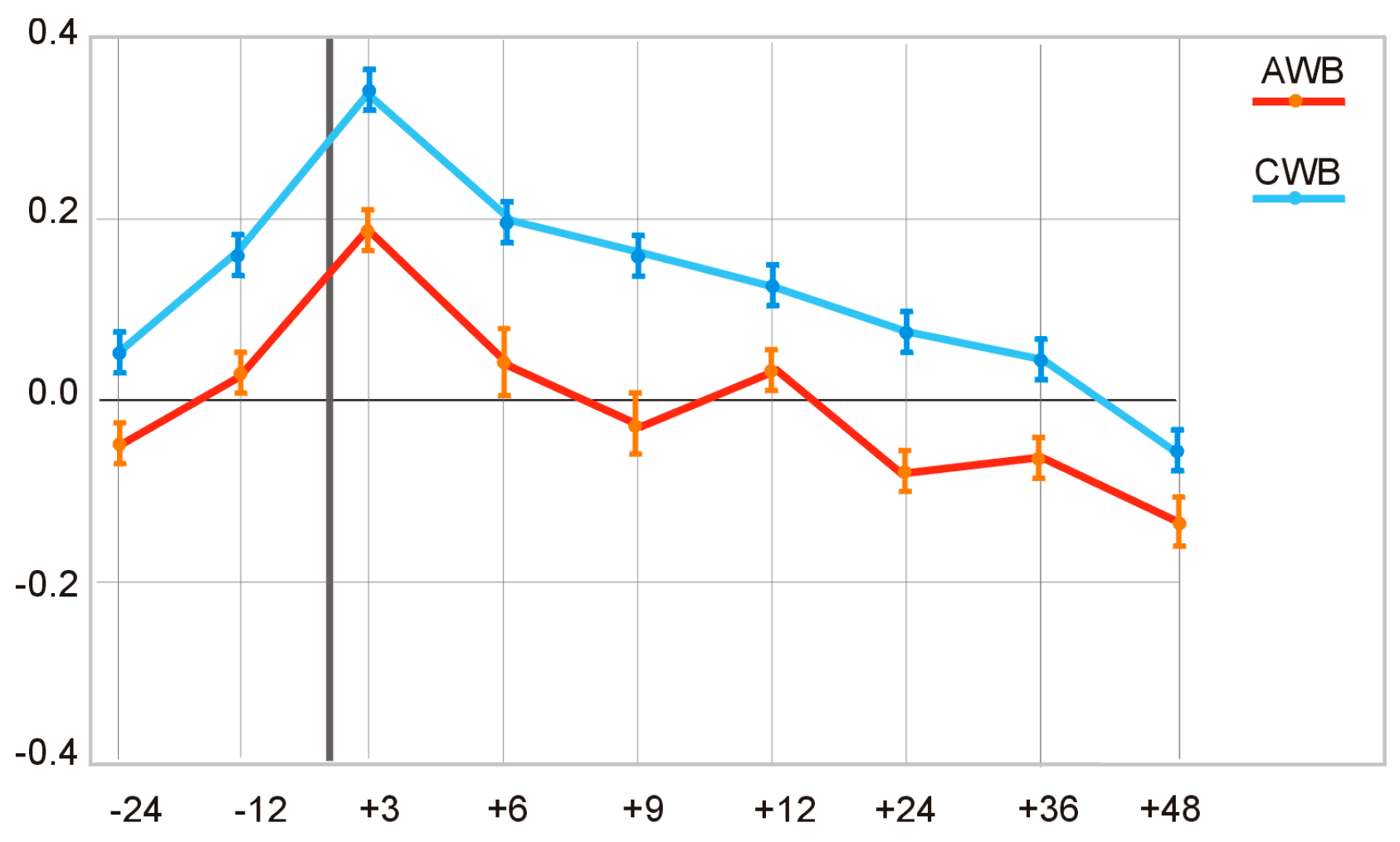

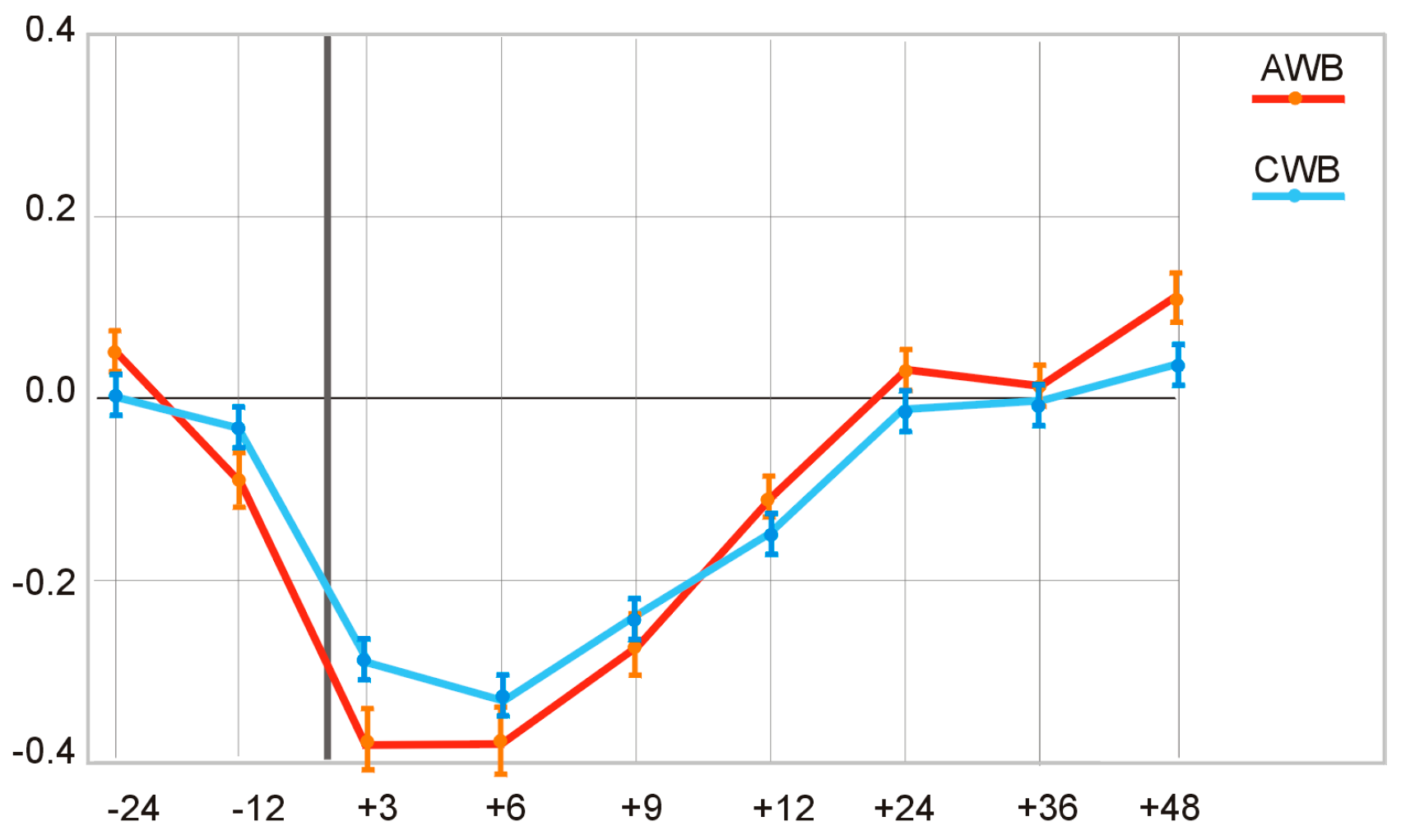

- Kettlewell, Nathan, Richard W. Morris, Nick Ho, Deborah A. Cobb-Clark, Sally Cripps, and Nick Glozier. 2020. The Differential Impact of Major Life Events on Cognitive and Affective Wellbeing. SSM—Population Health 10: 100533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Mihyeon. 2014. Family Background, Students’ Academic Self-Efficacy, and Students’ Career and Life Success Expectations. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling 36: 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim-Prieto, Chu, Ed Diener, Maya Tamir, Chistie Scollon, and Marissa Diener. 2005. Integrating The Diverse Definitions of Happiness: A Time-Sequential Framework of Subjective Well-Being. Journal of Happiness Studies 6: 261–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knabe, Andreas, Steffen Rätzel, Ronnie Schöb, and Joachim Weimann. 2010. Dissatisfied with Life but Having a Good Day: Time-use and Well-being of the Unemployed. The Economic Journal 120: 867–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Lufanna C. H., Robert A. Cummins, and Anna L. D. Lau. 2013. Cross-Cultural Difference in Subjective Wellbeing: Cultural Response Bias as an Explanation. Social Indicators Research 114: 607–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lench, Heather C. 2011. Personality and Health Outcomes: Making Positive Expectations a Reality. Journal of Happiness Studies 12: 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindfors, Pirjo Maria, O. A. Meretoja, S. M. Töyry, Ritva Luukkonen, Marko Elovainio, and Timo J. Leino. 2007. Job Satisfaction, Work Ability and Life Satisfaction among Finnish Anaesthesiologists. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 51: 815–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, Myles-Jay, Paul Dieppe, and Antonieta Medina-Lara. 2016. Review of 99 Self-Report Measures for Assessing Well-Being in Adults: Exploring Dimensions of Well-Being and Developments over Time. BMJ Open 6: e010641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucas, Richard E. 2007. Adaptation and the Set-Point Model of Subjective Well-Being: Does Happiness Change After Major Life Events? Current Directions in Psychological Science 16: 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, Richard E., Andrew. E. Clark, Yannis Georgellis, and Ed Diener. 2004. Unemployment Alters the Set Point for Life Satisfaction. Psychological Science 15: 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, Maike, and Sabrina Intelisano. 2018. Hedonic Adaptation and the Set Point for Subjective Well-Being. In Handbook of Well-Being. Salt Lake City: DEF Publishers, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, Maike, Louise C. Hawkley, Michaeal Eid, and John T. Cacioppo. 2012a. Time Frames and the Distinction between Affective and Cognitive Well-Being. Journal of Research in Personality 46: 431–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, Maike, Ulrich Schimmack, and Michael Eid. 2011. Stability and Variability in the Relationship between Subjective Well-Being and Income. Journal of Research in Personality 45: 186–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, Maike, Wilhelm Hofmann, Michael Eid, and Richard E. Lucas. 2012b. Subjective Well-Being and Adaptation to Life Events: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 102: 592–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lykken, David, and Auke Tellegen. 1996. Happiness Is a Stochastic Phenomenon. Psychological Science 7: 186–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansell, Warren, and Richard S. Marken. 2015. The Origins and Future of Control Theory in Psychology. Review of General Psychology 19: 425–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, Rachel, and Mikko Myrskylä. 2013. Family, Money, and Health: Regional Differences in the Determinants of Life Satisfaction over the Life Course. Advances in Life Course Research 18: 115–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2013. Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques. In OECD Guidelines on Measuring Subjective Well-Being. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi, Shigehiro, Jesse Graham, Selin Kesebir, and Iolanda C. Galinha. 2013. Concepts of Happiness Across Time and Cultures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 39: 559–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orkin, Kate, Rob Garlick, Mahreen Mahmud, Richard Sedlmayr, Johannes Haushofer, and Stefan Dercon. 2023. Aspiring to a Better Future: Can a Simple Psychological Intervention Reduce Poverty? Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, p. w31735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Alexander, and Kyung-Hyun Suh. 2023. Hardiness and Expectations for Future Life: The Roles of Perceived Stress, Music Listening for Negative Emotion Regulation, and Life Satisfaction. Behavioral Sciences 13: 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleeging, Emma, Martijn Burger, and Job Van Exel. 2021. The Relations between Hope and Subjective Well-Being: A Literature Overview and Empirical Analysis. Applied Research Quality Life 16: 1019–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, William Treval. 1973. Behavior: The Control of Perception. New York: Benchmark Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rojas, Mariano, and Ruut Veenhoven. 2013. Contentment and Affect in the Estimation of Happiness. Social Indicators Research 110: 415–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusk, Reuben D. 2022. An Adaptive Motivation Approach to Understanding the ‘How’ and ‘Why’ of Wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19: 12784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, Laurie. 2024. The Science of Well-Being. Available online: https://www.coursera.org/learn/the-science-of-well-being (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Savi Çakar, Firdevs. 2012. The Relationship between the Self-Efficacy and Life Satisfaction of Young Adults. IES 5: 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Huanhuan, Zahari Ishak, and Liheng Fan. 2022. The Higher the Life Satisfaction, the Better the Psychological Capital? Life Satisfaction and Psychological Capital: A Moderated Mediation Model. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 772129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staehr, Johansen K. 1998. The Use of Well-Being Measures in Primary Health Care-the DepCare Project. In World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe: Well-Being Measures in Primary Health Care-the DepCare Project. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Steel, Piers, Joseph Schmidt, and Jonas Shultz. 2008. Refining the Relationship between Personality and Subjective Well-Being. Psychological Bulletin 134: 138–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavousi, Mahmoud, Ali Reza Hidarnia, Ali Montazeri, Ebrahim Hajizadeh, Farhad Taremain, and Fazlollah Ghofranipour. 2009. Are Perceived Behavioral Control and Self-Efficacy Distinct Constructs. European Journal of Scientific Research 30: 146–52. [Google Scholar]

- Tay, Louis, Miao Li, David Myers, and Ed Diener. 2014. Religiosity and Subjective Well-Being: An International Perspective. In Religion and Spirituality Across Cultures. Edited by Chu Kim-Prieto. Cross-Cultural Advancements in Positive Psychology. Dordrecht: Springer, vol. 9, pp. 163–75. ISBN 978-94-017-8949-3. [Google Scholar]

- Tov, William. 2018. Well-Being Concepts and Components. Handbook of Well-Being 30: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman. 2000. Loss Aversion in Riskless Choice: A Reference-Dependent Model. In Choices, Values, and Frames. Edited by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 143–58. ISBN 978-0-511-80347-5. [Google Scholar]

- Wardle, Jane, Andrew Steptoe, Gabriel Guliš, Gudrun Sartory, Helena Sêk, Irina Todorova, Claus Vögele, and Michal Ziarko. 2004. Depression, Perceived Control, and Life Satisfaction in University Students from Central-Eastern and Western Europe. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 11: 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiest, Maja, Benjamin Schüz, Noah Webster, and Susanne Wurm. 2011. Subjective Well-Being and Mortality Revisited: Differential Effects of Cognitive and Emotional Facets of Well-Being on Mortality. Health Psychology 30: 728–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Timothy D., and Daniel T. Gilbert. 2003. Affective Forecasting. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 35, pp. 345–411. ISBN 978-0-12-015235-3. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, Hasan. 2018. Fear of Success and Life Satisfaction in Terms of Self-Efficacy. UJER 6: 1278–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, Shinpei, and Yuma Hashimoto. 2020. The Effect of Induced Optimism on the Optimistic Update Bias. BMC Psychology 8: 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Yulan, and Jun Luo. 2018. Dispositional Optimism and Well-Being in College Students: Self-Efficacy as a Mediator. Social Behavior and Personality 46: 783–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, Philip G., and John N. Boyd. 1999. Putting Time in Perspective: A Valid, Reliable Individual-Differences Metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77: 1271–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Scale | Number of Items | Cronbach Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction | PWI | 7 | 0.778 |

| AWB | WHO-5 | 5 | 0.879 |

| General self-efficacy | GSE | 8 | 0.900 |

| Future life expectations | FLE | 7 | 0.827 |

| Mean | SD | PWI | WHO-5 | FLE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PWI | 19.22 | 4.587 | 1 | ||

| WHO-5 | 10.79 | 4.616 | 0.718 *** | 1 | |

| FLE | 20.57 | 4.922 | 0.620 *** | 0.541 *** | 1 |

| GSE | 23.22 | 5.160 | 0.519 *** | 0.377 *** | 0.585 *** |

| Effect | B | SE (B) | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a: FLEs → GSE | 0.6138 | 0.0867 | 0.5855 | 7.0756 | 0.0000 |

| b: GSE → PWI | 0.2110 | 0.0855 | 0.2374 | 2.4669 | 0.0154 |

| c (total): FLEs → PWI | 0.5780 | 0.0746 | 0.6203 | 7.7478 | 0.0000 |

| c’ (direct): FLEs → PWI | 0.4485 | 0.0897 | 0.4813 | 5.0011 | 0.0000 |

| ab (indirect): FLEs → GSE → PWI | 0.1295 | 0.0560 | 0.1390 | 2.3125 | 0.0210 |

| Effect | B | SE(B) | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a: PWI → WHO-5 | 0.4213 | 0.0662 | 0.5449 | 6.3677 | 0.0000 |

| b: WHO-5 → FLEs | 0.6578 | 0.0940 | 0.5457 | 7.0000 | 0.0000 |

| c (total): PWI → FLEs | 0.5781 | 0.0746 | 0.6203 | 7.7478 | 0.0000 |

| c’ (direct): PWI → FLEs | 0.3009 | 0.0727 | 0.3229 | 4.1419 | 0.0001 |

| Ab (indirect): PWI → WHO-5 → FLEs | 0.2770 | 0.0590 | 0.2974 | 4.6949 | 0.0000 |

| Index | Description | Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | Chi-square divided by degrees of freedom | ≤3 |

| GFI | Goodness of Fit Index | ≥0.90 |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index | ≥0.90 |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index | ≥0.90 |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation | ≤0.06 |

| PCLOSE | p-value of closeness of fit | ≥0.05 |

| Index | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| χ2/df | Chi-square divided by degrees of freedom | 0.378 |

| GFI | Goodness of Fit Index | 0.998 |

| TLI | Tucker–Lewis Index | 0.987 |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index | 1.000 |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation | 0.000 |

| PCLOSE | p-value of closeness of fit | 0.585 |

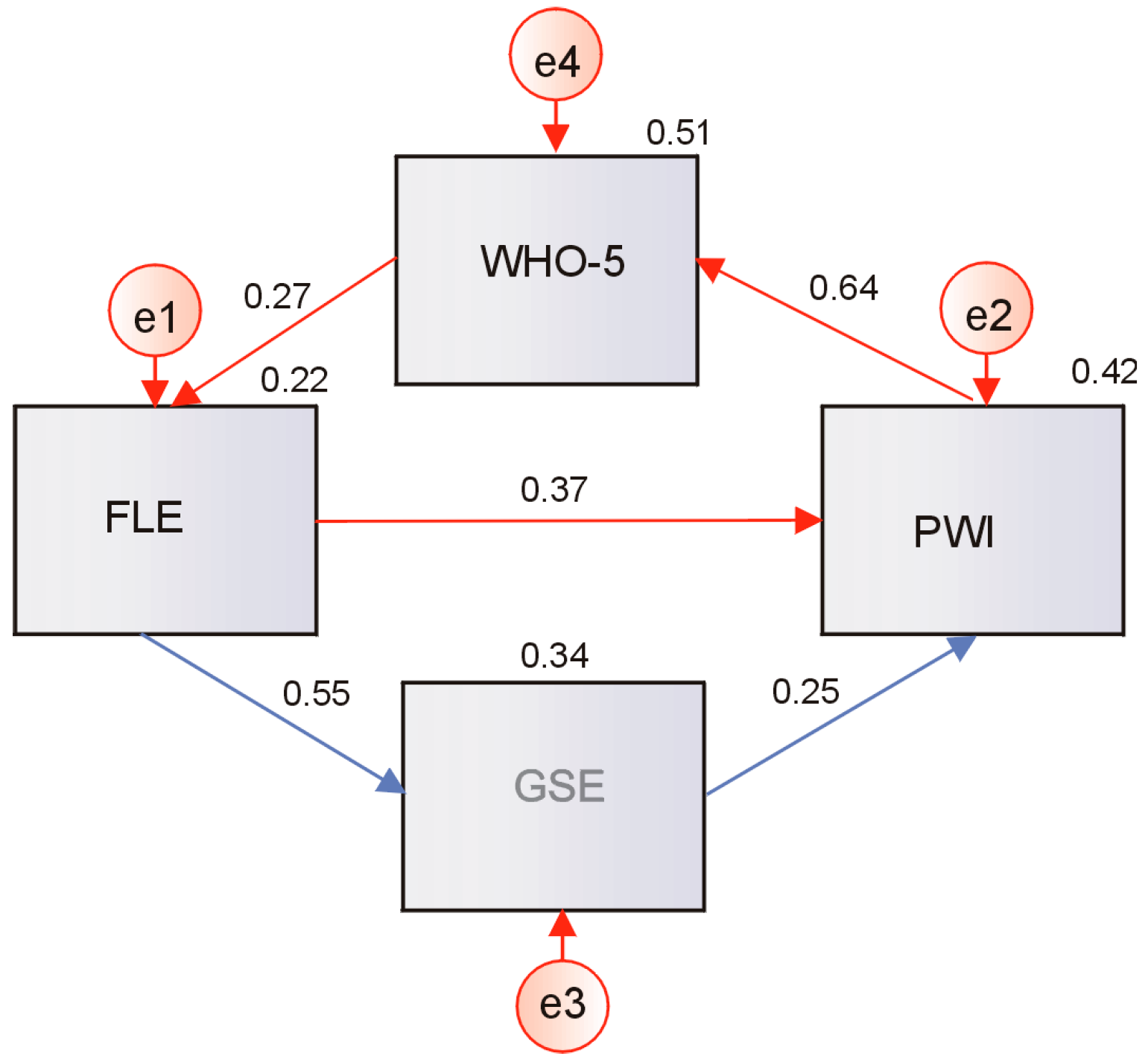

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PWI | <--- | FLE | 0.391 | 0.119 | 3.298 | *** |

| WHO | <--- | PWI | 0.469 | 0.057 | 8.226 | *** |

| FLE | <--- | WHO | 0.343 | 0.161 | 2.134 | 0.033 |

| GSE | <--- | FLE | 0.582 | 0.089 | 6.552 | *** |

| PWI | <--- | GSE | 0.253 | 0.098 | 2.586 | 0.010 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Susnea, I.; Pecheanu, E.; Cocu, A.; Iacobescu, P.; Tudorie, C.; Susnea, S. A Control Theory Approach to Understanding the Dynamics of Cognitive Wellbeing. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14030158

Susnea I, Pecheanu E, Cocu A, Iacobescu P, Tudorie C, Susnea S. A Control Theory Approach to Understanding the Dynamics of Cognitive Wellbeing. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(3):158. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14030158

Chicago/Turabian StyleSusnea, Ioan, Emilia Pecheanu, Adina Cocu, Paul Iacobescu, Cornelia Tudorie, and Simona Susnea. 2025. "A Control Theory Approach to Understanding the Dynamics of Cognitive Wellbeing" Social Sciences 14, no. 3: 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14030158

APA StyleSusnea, I., Pecheanu, E., Cocu, A., Iacobescu, P., Tudorie, C., & Susnea, S. (2025). A Control Theory Approach to Understanding the Dynamics of Cognitive Wellbeing. Social Sciences, 14(3), 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14030158