1. Introduction

Much of the policy debate in the last few decades in the UK has centred on the issues of reducing inequalities in education and promoting intergenerational social mobility (

Cabinet Office 2011;

Department for Education 2017). In this debate, the role of education features prominently as the main instrument through which to promote social mobility. Scholars have manifested strong scepticism about the reliance solely on educational expansion and educational reforms to eradicate social class inequalities in the labour market. This is because possessing high levels of education in most cases is an essential requirement for social mobility to take place but it is not a sufficient condition to guarantee equal chances of accessing top-level jobs (

Boliver 2017;

Brown 2013;

Iannelli and Paterson 2007). In other words, researchers have warned that simply increasing the number of working class people graduating from higher education (HE) will not automatically increase social mobility. The empirical evidence has indeed confirmed this. Various studies have consistently shown that tertiary graduates from more advantaged social classes have higher chances of entering top-level jobs compared to their counterparts from less advantaged social classes (

Crawford et al. 2016;

Britton et al. 2016;

Jacob et al. 2015).

These studies have focused on national and cross-country analysis of patterns of social inequalities but have not paid much attention to within-country geographical variation in employment opportunities to further understand those patterns (an exception is the recent work by

Friedman and Laurison (

2017); see next section). Human geographers, on the other hand, have long analysed the importance of job opportunities in different areas/regions of the UK to explain different degrees of career promotion (e.g., see the seminal work by

Fielding (

1992), on the ‘escalator’ regions) and different patterns of geographical mobility. However, they have overlooked the relationship between area-level opportunities and inequalities in labour market outcomes by social class of origin.

This paper aims to fill the missing link between these two strands of literature, thus providing new important evidence on the spatial dimension of social class inequalities in graduates’ labour market outcomes. It seeks to contribute to our understanding of how opportunity structures in the labour market relate to social class inequalities in graduates’ occupational destinations, ultimately providing new insights which can inform policies aimed at improving social mobility chances. Specifically, this paper investigates whether and the extent to which, the chances of graduates from different social origins gaining access to top-level occupations (i.e., a higher professional/managerial occupation) and avoiding low-level jobs varies by area-level characteristics. It will further contribute to the existing literature by providing a more in-depth and nuanced picture of the importance of graduates’ HE experiences (i.e., prestige of the HE institution attended, fields of study and class of degree achieved), sector of employment entered and geographical mobility to explain area-level variations in social class inequalities in graduates’ destinations.

Our key research questions are:

- (1)

Does the social-class gap in graduates’ occupational destinations vary depending on area-level job opportunities? If so, how do they vary?

- (2)

How far do the observed patterns result from area-level factors rather than selective migration?

2. Social Class, Labour Market Structure and Geographical Location

The link between job opportunities and social class inequalities is not straightforward. Social mobility research has shown that even when opportunities expand social class inequalities may remain stable. Thus, the expansion of professional and managerial occupations which occurred in the UK in the 1970s and 1980s, while offering new opportunities for a minority of socially disadvantaged people, did not change the relative distribution of opportunities which remained largely in favour of middle class children (

Goldthorpe 1987;

Payne 1987;

Marshall et al. 1988;

Erikson and Goldthorpe 1992). More recent social mobility research has confirmed substantial stability in relative patterns of social mobility in the UK despite the growing numbers of highly educated people from less advantaged social classes (

Bukodi et al. 2015;

Iannelli and Paterson 2006;

Goldthorpe and Mills 2004).

Several explanations focusing on individual and institutional factors have been put forward to explain the relationship between social origin and graduates’ labour market outcomes. Graduates from different social origins tend to differ in their HE experiences–such as the prestige of the HE institution attended (

Iannelli et al. 2016;

Sullivan et al. 2014;

Boliver 2011), chosen field of study (

Iannelli et al. 2018;

Laurison and Friedman 2016;

Van de Werfhorst et al. 2003) and class of degree achieved (

Crawford 2014;

Crawford et al. 2016)—but also in earlier cognitive skills (

Sullivan et al. 2017). However,

Crawford et al. (

2016) found that ‘even among those attending the same university, attaining the same degree class in the same subject, those from more privileged backgrounds are more likely to access the top professions’ (p. 14). National institutional factors have also been found to shape the transition from higher education to the labour market (

Triventi 2013;

Jacob et al. 2015). Specifically, in the UK, social class inequalities in graduates’ occupational outcomes were found to be more marked than in Germany and only partly mediated by graduates’ field of study, higher education achievement and institution attended (

Jacob et al. 2015). Given the larger supply of university graduates and the weaker links between HE qualifications and labour market outcomes in the UK, employers may need to rely on factors other than credentials (e.g., soft skills; candidates’ social and cultural capital) to select their future employees. This ultimately favours people from higher social origins (

Jackson et al. 2005).

The patterns highlighted in the research above are based on national-level averages and may cover the existence of very different patterns within the country. Indeed, as in other European countries, employment opportunities are unevenly distributed within the UK. Statistics published by the Office of National Statistics show wide regional and sub-regional variations in employment, unemployment and inactivity rates (see

ONS 2018a) and in labour productivity (

ONS 2018b). These differences may play an important role in altering the patterns of social class inequalities among graduates. As mentioned in the introduction, research mainly conducted by human geographers has highlighted the importance of analysing local labour market opportunities and the relationship between the job opportunities available in different geographical areas and individuals’ chances of getting a good job. In particular, several studies have linked intra-generational social mobility (i.e., movements within and between social classes occurring during one’s occupational career) with spatial mobility (e.g.,

Fielding 1992;

Van Ham et al. 2012;

Champion et al. 2013). They showed that more economically developed areas in the UK (e.g., South-East area and London in England or Edinburgh in Scotland) act as ‘escalator regions’ (

Fielding 1992) displaying a higher level of upward intra-generational occupational mobility for both people who stay and people who migrate into these regions. The issue of geographical mobility has been the topic of many studies. The main results of this literature have pointed out that highly educated people are more geographically mobile than less educated people; geographical mobility is associated with higher occupational and economic returns (

Fielding 1992;

Van Ham et al. 2012;

Kidd et al. 2017); and that the likelihood of moving for HE studies and for employment are highly correlated (

Faggian et al. 2007).

Kidd et al. (

2017) also stress that mobility in terms of employment is crucial. Their results suggest that being mobile for employment is more important than the initial decision of whether or not to move to study. Indeed, those individuals who move to go to university but subsequently return to the family domicile area and those who remain in the same university location for employment either do not have an earning premium relative to non-graduates or have only a modest premium in comparison to those who moved away for employment.

Labour economists have also contributed to this theme of enquiry by focusing on geographical variations in earnings and trying to distinguish the effects of area-level factors from individual-level factors.

O’Leary and Sloane (

2008) found substantial variations in the earnings benefits of university graduates across regions of the UK, with graduates in London having the highest economic returns, followed by South-East England. However, the regional earnings differential was substantially reduced once the costs of living were taken into account. Moreover, the remaining earning differentials were not explained by differences in occupational and industrial structures across regions, despite the fact that London and the South-East had a larger number of graduates employed in managerial and senior positions. The authors highlight that the main driver of these differences can be traced to the higher productivity of these areas derived from spillover and agglomeration effects in areas of high concentration of graduates.

Gibbons et al. (

2010) examined the extent to which wage disparities are due to a sorting mechanism—i.e., workers with different characteristics gather in different areas—or whether they are due to an area-of-employment effect—i.e., the same types of workers achieve different outcomes in different areas of the country. They showed that individual characteristics explain a much larger part of wage disparities across areas than area effects (90% versus 10% of area-level wage variation). Area effects also explain only 1% of the overall levels of individual wage disparity.

Nonetheless, these latter studies did not investigate the role of family of origin and whether and how social class inequalities in graduates’ occupational outcomes vary by area-level characteristics; in other words, they did not investigate whether intergenerational social mobility is also related to geographical area of employment.

Recent policy reports have stressed the fact that regional characteristics can enable or hamper social mobility (

Friedman et al. 2017;

Social Mobility Commission 2017) and hence, those coming from less privileged backgrounds and who live in areas with fewer opportunities can suffer a double disadvantage, not only related to their family of origin but also to the geographic area. The 2017 Social Mobility Commission report provided detailed geographical analysis of a variety of factors which can influence

intergenerational social mobility, showing that there are great regional disparities in the UK: in England, two thirds of highly skilled and knowledge-based jobs are in cities, with 1 in 3 of such jobs being based in London. However, this report did not focus explicitly on graduates and access to top-level jobs.

Friedman et al. (

2017) focused on professional jobs and regional inequalities. They found that there are large inequalities within the higher professional and managerial occupations in Britain, in particular in Central London (and in the lucrative banking and finance jobs in the City). Indeed, in Central London, the social composition of professional and managerial jobs is disproportionately in favour of people from socially privileged backgrounds. Moreover, those from working-class backgrounds who reach these positions have lower economic returns: their average earnings are 10 percentile points lower than their colleagues who comes from more advantaged backgrounds.

3. Theoretical Explanations and Hypotheses

Various explanations may account for the existence, or lack, of geographical variation in social class inequalities in graduates’ destinations.

Based on the social mobility research (e.g.,

Goldthorpe 1987;

Payne 1987;

Marshall et al. 1988;

Erikson and Goldthorpe 1992), we could argue that social class inequalities tend to reproduce themselves irrespective of the economic conditions of a place. Thus, better regional job opportunities may not translate into a more equal distribution of professional jobs (as was the case in the 1970s and 1980s when professional and managerial jobs expanded). This is because the chances of all graduates from all backgrounds would equally increase; hence, the relative gap by parental background would remain the same regardless of the regional opportunities as the same mechanisms which perpetuate inequality will be at work in all types of areas (hypothesis of constant inequalities). Moreover, information on job opportunities may be harder to access for graduates from less advantaged social backgrounds and the high costs of moving and of living in areas with higher professional job opportunities (such as London and Edinburgh) may discourage such moves.

Following this line of thinking we would expect that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Class-of-origin effect on entering top-level occupations does not vary across areas with different job opportunities.

On the other hand, following the ‘escalator’ regions literature (e.g.,

Fielding 1992;

Van Ham et al. 2012;

Champion et al. 2013), we could envisage an alternative scenario. Thus, in places where job opportunities are greater, graduates from lower social backgrounds may have easier access to professional and managerial jobs and the terms of job competition may be more meritocratic. Areas with more job opportunities are likely to offer a wider range of occupations and for a wider range of graduates, therefore, there will be less social bias which usually accompanies access to traditional professions (

Van de Werfhorst et al. 2003;

Friedman et al. 2017). In contrast, in places where job opportunities for graduates are scarce the competition for professional jobs is higher and inequalities may be greater since those from higher social classes of origin are likely to be better equipped to compete. This advantage may be because they possess the best match (in terms of types of degree requested, for example, more traditional professions such as doctors and lawyers), or because they benefit from direct support from their parents, such social networks, advice and financial assistance which would allow them either to wait for the next suitable vacancy or to move away to areas where the opportunities are available.

Thus, an alternative hypothesis is:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). The higher the job opportunities in the geographical area of employment, the smaller the social class inequalities among graduates in accessing top-level jobs.

The reason for lower social class inequalities in employment areas with high level of employment, especially in professional and managerial jobs, could be explained by two mechanisms: area-level effect or selective migration. To discern which effect is at play, we will distinguish between graduates who moved from their area of domicile and graduates who stayed there. For example, if lower inequalities are driven by structural opportunities and areas with more job opportunities indeed act as equalizers of graduates’ employment prospects, then we would expect that:

Hypothesis 2a (H2a). The smaller social class inequalities in areas with greater job opportunities will apply both to those graduates who moved to these areas of employment and to graduates who are from those areas (or returned there after having studied in a different area).

On the contrary, if different patterns emerge between movers and non-movers, then we will analyse whether a potential reduction in inequalities in areas with higher job opportunities reflect the selection of the ‘best’ or ‘most suitable’ graduates from various areas of the country, irrespective of their social class of origin (selective migration). In this case we would expect that:

Hypothesis 2b (H2b). The smaller social class inequalities in areas with greater job opportunities can be explained by graduates’ individual characteristics.

4. Data and Methods

The data used in this study come from the Destinations of Leavers from Higher Education Early and Longitudinal Survey (DLHE), which was conducted by the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) in 2012. These data contain labour market information on graduates who completed higher education programmes at a UK HE institution in the academic year 2008/09, 3.5 years after graduation.

1 Labour market information from the survey was linked to the HESA administrative student records which contain information on students’ family background characteristics, HE institution attended, programme of study and final qualification achieved.

The sample used in this paper is restricted to UK-domiciled full-time first-degree graduates who were aged 21 or under at the time of entering HE. Our focus on young graduates is mainly due to the limited information on parental social class of mature students available in this dataset. UCAS (Universities and Colleges Admissions Services) consistently collects this information only from young HE applicants since mature applicants are asked about information on their own occupation before entering HE. However, due to data availability and comparability of macro-indicators at NUTS 3 (Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics) area-level, the analysis focuses on Great Britain (GB) and hence does not include Northern Ireland. We started with a sample of about 29,000

2 for GB, of whom 24,585 were in employment 3.5 years from graduation (85%).

3 Of these, about 23% had missing data on at least one of the key variables used in the analysis. These cases were removed from the analysis, leaving us with a total working sample of 18,940.

4 Finally, the sample was clustered according to

NUTS 3 regions of employment which we derived from the information on graduates’ postcodes of employment.

5 We used the most detailed classification of NUTS 3 (133 geographical units/128 units for GB) derived from the ONS NSPD lookup table referring to May 2009.

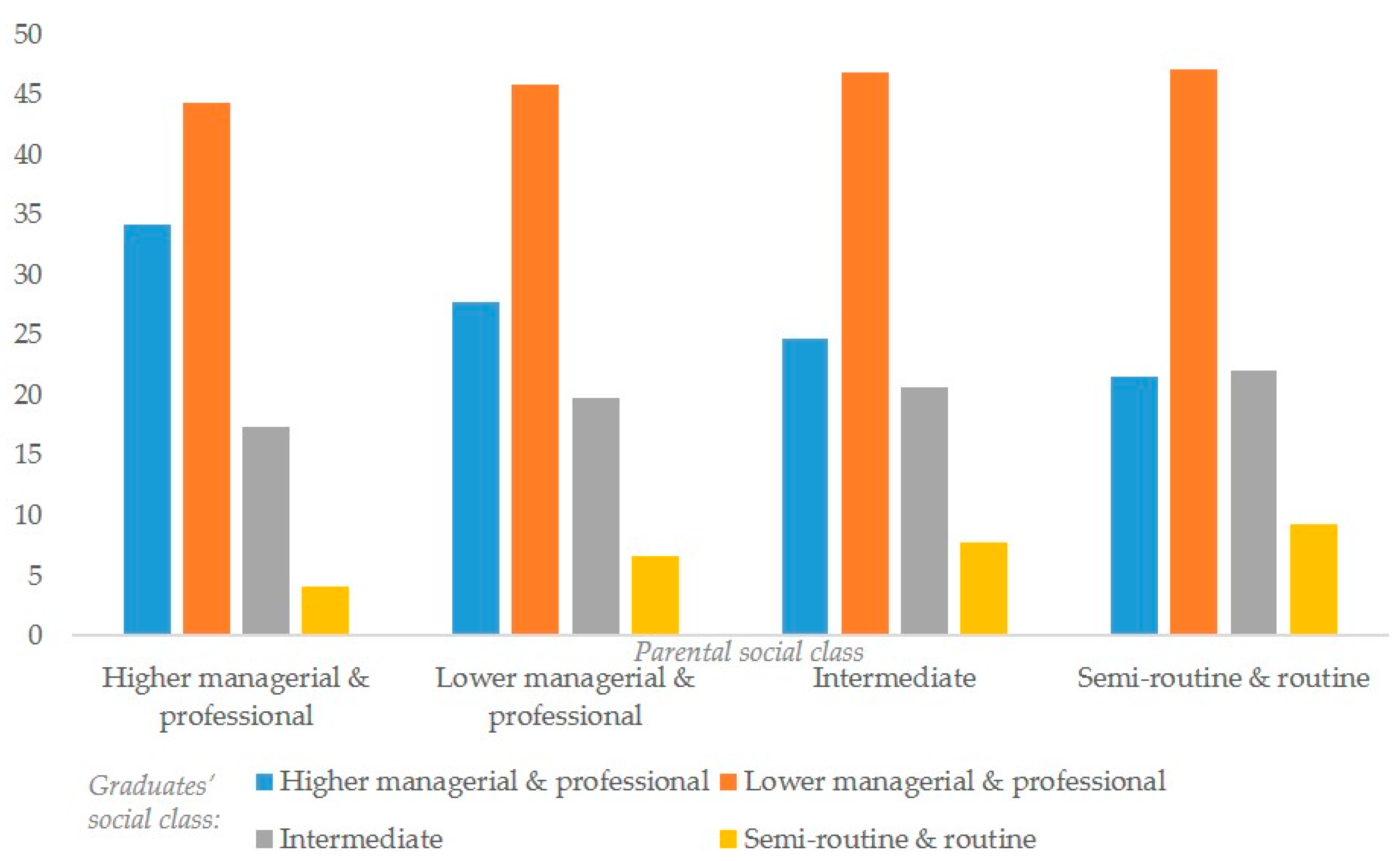

The dependent variable in the study is

social class of destination 3.5 years after graduation. This is measured using the National Statistics Socio-Economic Classification (NS-SEC) (

Rose et al. 2005) which distinguishes higher managerial and professional occupations (NS-SEC 1), lower managerial and professional occupations (NS-SEC 2), intermediate occupations (NS-SEC 3-5) and semi-routine and routine occupations (NS-SEC 6-7).

Our key independent variable, based on which we assess social inequalities is

parental social class, also measured by NS-SEC, using the same categories as for respondents’ social class. Further explanatory variables capture key aspects of graduates’ higher education experiences. First, the

type of HE institution attended is a categorical variable which comprises the oldest and most prestigious universities in the UK (Universities of Oxford and Cambridge in England and the Universities of Edinburgh, Glasgow, Aberdeen and St. Andrews in Scotland), other old universities founded before 1950, newer universities (founded between 1950 and 1992) and post-92 universities (former polytechnics) and other higher education institutions. Second,

field of study distinguishes between nine categories: Medicine and Veterinary, Subjects allied to medicine, Natural Sciences (i.e., Biological Sciences, Agriculture, Physics, Maths, Computer Science), Engineering and Architecture, Humanities, Social Sciences and Arts (i.e., Social Studies, Languages, Historical & Philosophical Studies, Arts & Design), Law, Business and Mass Communication, Education Studies and Combined degrees. Thirdly,

attainment in higher education is measured by the class of degree achieved: first class (1), upper-second class (2:1), lower-second class (2:2), third class (3) and unclassified (mainly ordinary degrees). Fourthly,

further qualification achieved after first degree captures whether graduates acquired any additional credentials, distinguishing between nine categories: No further qualification, Higher degree by research, Higher degree by taught course, Postgraduate diploma or certificate, First degree, Other diploma or certificate, Professional qualifications, Other qualifications, Not aiming for a qualification. This variable is included in the statistical modelling to control for possible effects of further qualification achieved between first leaving HE education and the occupation acquired 3.5 years after graduation. In addition, apart from the social class of destination, we also examine another employment characteristic via the type of industry where graduates work. We distinguish between nine sectors: Primary; Secondary; Tertiary; Finance, Insurance and Real Estate; Professional, Scientific and Technical; Public Administration, Defence and Compulsory Social Security; Education; Human Health and Social work; and Other Quaternary. Although, field of study might also serve as a proxy for the sector in which graduates are likely to work, there is also a fair amount of mismatch between field of study and occupational/industry fields (

Docherty and Fernandez 2014). For this reason, accounting for the industry of the current employer provides a more direct measure of the labour market in which graduates work.

In our statistical modelling, we also include a measure of geographic mobility to identify whether respondents moved from their area of domicile (as reported when entering higher education) to another area for employment, that is, whether the domicile NUTS 3 is different from the employment NUTS 3. A more refined geographic mobility variable accounting for distance and moves to the HE institution was also examined but the identified patterns of those who moved for both HE and employment, those who moved for employment only and those who moved for HE and remained in the area of the HE institution were very similar. Also, the patterns of those who did not move at all and those who moved for HE and returned to the domicile area were similar. Therefore, for parsimony we decided to opt for the simplified version, which distinguishes whether graduates moved for employment or not.

In our analyses, we control for other individual characteristics, that is, age (i.e., four age groups 20, 21–22, 23–24, 25+), gender (male/female), ethnicity (White, Asian, Black, Other), disability (whether disabled or not) and country of domicile (England, Wales, Scotland).

Our key independent variables at macro level include

macro indicators measuring job opportunities in the area of employment which were attached to NUTS 3 areas. These indicators were provided by the ONS Annual Population Survey, October 2009–September 2010 (

ONS SSD 2015) and include: (1) Percentages of Professionals; (2) Percentages of Managers, Directors & Senior Officials and (3) Employment rate. For simplicity, we will focus more on the first indicator and include results using the latter two indicators in the

supplementary material (

Figures S1 and S2).

6 In the statistical modelling, we adopt a multilevel framework with graduates nested into NUTS3 regions of the area of employment

7 to analyse the variance in graduates’ destinations at both individual (level 1) and area level (level 2) and to disentangle the effect of macro- and micro- level factors on the outcome. Macro-level indicators were attached to the area of employment to measure the regional job opportunities. Models are estimated using MLwiN software (

Rasbash et al. 2015). We use IGLS (iterative generalized least squares) estimation, followed by Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), therefore the MCMC initial parameters starting value is based on the IGLS estimations. The analysis was carried out using a multilevel multinomial model which can be expressed by the following equation:

Our dependent variable is expressed by the log-odds ratios of being in category k instead of category 1 for individual i in group j; is the intercept and is the effect of for the contrast of category k versus category 1 for individual i in group j and is the level 2 random effect for the contrast of response category k with the reference category.

First, to assess the variance at area level (level 2) and the extent to which different macro-indicators explain this variance, we run several models starting with the null model and adding one macro-indicator variable at a time, without including any other control variable. We then compare the amount of area variance explained by each macro-indicator against the null model. In this way, we test the statistical significance of the macro-level indicators, the direction of the association with our outcome and, at the same time, we assess to what extent these macro-level indicators explain the initially identified variance at level 2. Second, to investigate whether the social-class gap in graduates’ occupational destinations varies depending on the job opportunities in the area of employment, we test interactions between social origin (level 1) and our macro-level indicators (level 2), generally referred to as cross-level or micro-macro interaction. The interaction terms allow us to establish whether the percentage of professional or managerial jobs available in the area of employment and the employment rate moderate the relationship between parental social class and the social class attained by graduates 3.5 years after graduation. Building on these models, we also test three-way interactions to assess whether the observed patterns are similar across different groups. The estimates obtained from the multilevel models are presented in the

supplementary material.

6. Conclusions

This paper provides new empirical evidence on the link between area-level opportunities and social class inequalities in graduates’ occupational outcomes. It assesses whether the social-class gap in graduates’ occupational destinations documented in various studies may vary depending on area-level job opportunities and, if so, the mechanisms behind this spatial variation. Based on the literature on social mobility and the ‘escalator’ regions, we formulated two main hypotheses: one predicting constant social class inequalities across areas with different levels of job opportunities and another predicting a decline in social class inequalities with the increase in job opportunities. Moreover, regarding the latter hypothesis, we investigated why such a decline in inequalities might occur—whether due to structural area factors (i.e., the higher number and variety of jobs requiring a degree available in such areas) or because of selective migration, that is, the most qualified graduates, regardless of their social background, are attracted to areas with more opportunities.

In line with other studies (e.g.,

Gibbons et al. 2010), we found that the overall area-level variation in the chances of getting a top-level job and avoiding a low-level job is low compared to the individual-level variation. However, area characteristics such as the percentage of professional jobs available and the employment rate significantly increase graduates’ chances of getting a top-level job. Three main findings emerged in relation to social class inequalities in graduates’ occupational destinations.

The first is that the relationship between area-level job opportunities and graduates’ chances of getting a top-level job is not constant among graduates from different social backgrounds. Graduates from working class of origin have significantly lower chances of entering top-level jobs when the employment opportunities are low but they catch up when the job opportunities are particularly high (in the ‘escalator’ areas). In contrast, graduates from the highest social class of origin show a less steep increase in their chances of gaining a top professional or managerial job since they have relatively higher chances of entering these jobs irrespective of the job opportunities in the area of employment. This pattern confirms our alternative research hypothesis, that is, there are lower social class inequalities in graduates’ probabilities of getting a high professional and managerial job in areas with a higher number of these jobs. This finding seems to suggest that areas with higher professional jobs may offer more equal opportunities.

However, a more in-depth analysis of the data reveals our second main finding, that is this pattern only applies to graduates who were geographically mobile. This leads us to reject the idea that structural characteristics of the area are behind the observed reduction in inequalities (H2a) as if this had been the case, graduates who did not move should have shown a similar pattern, which they do not. Therefore, moving for employment to areas with higher job opportunities appears to enhance substantially the chances of accessing a top-level job for graduates from lower social classes, to the extent that they have almost the same chances as the highest social classes.

Thus, our third finding suggests that selective migration may be the main mechanism behind the equalization of graduates’ occupational outcomes in areas with greater occupational opportunities (H2b, that is, the best qualified graduates from all social backgrounds move to areas with the best opportunities). We have further investigated this by testing the role of individual factors (HE experiences and sector of employment entered) in explaining the movers’ patterns. We found that ‘fields of study’ and ‘sector of activity’ have the strongest explanatory power of the social class gap among mobile graduates employed in areas with different levels of professional job opportunities. The other factors which contribute to explain the gap are ‘class degree’ and ‘HE institution type.’ In relation to ‘fields of study’ and ‘sector of activity,’ we found that ‘Medicine and Veterinary’ and working in ‘Human Health and Social Work’ (and to a lesser extent in the Finance and Professional Scientific sectors) provide an advantage for middle class graduates to enter top-level jobs in areas with low percentages of professional jobs.

It is important to acknowledge that our study has some limitations. First, our analysis offers only a snapshot of graduates’ occupational opportunities at a relatively early point in time (3.5 years after graduation) and for those graduates who were in employment. 11% of graduates were still studying and another 5% were unemployed or inactive at the time of the survey. This means that we cannot assess whether our findings would hold for those people who entered the labour market at a later stage. Secondly, due to the limited information available in the data, we could not investigate the reasons behind the different patterns found among immobile graduates. Finally, we may have underestimated the extent of the social class gap due to the issues of survey and item non-response, which have led to a slight over-representation of graduates from more advantaged social classes of origin in our sample (see

Supplementary Materials, Tables S1 and S2).

Nevertheless, our findings provide important evidence that area-level opportunities together with geographical mobility are key to gaining access to top-level jobs for graduates from working class backgrounds. However, it is worth noting that among the mobile graduates, an equalization of job opportunities between those from working class and middle-class backgrounds is visible only in areas with the highest percentages of professional jobs (top decile). This suggests that in the other areas of the country, inequalities are still marked and the reasons for why this is the case will require further investigation.

Important policy implications can be drawn from our findings. On the one hand, widening access to some fields, such as Medicine, has the potential to make the competition for professional jobs in areas with lower job opportunities more equal. On the other hand, governmental policies mostly focused on widening access to higher education are inevitably too narrow and need to be extended to include measures aimed to equalize occupational opportunities. Promoting social mobility requires sustained support beyond access to and graduation from higher education to enable graduates from disadvantaged backgrounds to progress into professional graduate employment. Financial support for mobility may be needed to ensure that access to a wider range of opportunities for graduates is not shaped by the resources of their family of origin. Universities have a role too. University career services could play a key part in supporting young people from lower social backgrounds during the critical transition to the labour market by providing essential information on professional job opportunities and their geographical location. In conclusion, our findings have highlighted the need for policies which are not limited to a one-off intervention but take a life-course perspective to ensure equality of opportunity and outcomes for those from different social classes of origin.