Abstract

This article presents a participatory action research initiative involving counsellors and parents at a perinatal and family center for drug addiction in order to reflect on what shape parental participation might take within this resource. The goal was to document how moments of discussion would impact the parents’ participation, the parents’ journeys, and Rond-Point’s (RP) planned interventions. In November 2014, a group of parents took part in eight meetings, and a team of RP counsellors, in three meetings. Two combined “pooling meetings” were held between both groups in order to share ideas. Both before and after the initiative, to complete the data collection process, group meetings were held with the counsellors and individual interviews took place with the parents. In the parent group, the initiative gave rise to a culture of voicing their views, reflecting, and raising questions. In the counsellor group, the initiative led to changing how they worked and transforming the way they viewed parental participation. Nevertheless, the parents’ participation did not significantly change the center’s planned offerings. A number of clinical and organizational issues constituted obstacles to the parents’ power to act in this regard.

1. Introduction

In Quebec, Canada, and elsewhere in the world, over the last two decades, the topic of users’ participation in the management of public services—especially in the realm of health and social services—has featured prominently in political agendas (Hamel and Jouve 2006). Indeed, the new public management context and its resulting social policies, with their focus on efficiency, seek to expand actors’ responsibility and to boost users’ participation in their own well-being (Bellot et al. 2013). However, this exhortation to greater participation, situated as it is in a top-down logic, may well have a limited democratic reach. Indeed, it may be aimed more at strengthening individual skills than questioning the social safety net (Ewan 2017). Moreover, in a management context that prioritizes evidence-based practice in defining social programs (Couturier et al. 2009, 2013), adapting programs to local needs and requests may be challenging, in spite of the claims made in this regard (Bourque 2009; Dupuis and Farinas 2009). Since the fall of 2013, in Montreal, Quebec (Canada), pregnant women, children exposed to drugs and alcohol in utero, as well as their parents, have been able to receive integrated and specialized services from a multidisciplinary team under the same roof. Rond-Point (RP) is intended as a living environment, which, in addition to providing families with specialized and individualized services, offers various activities (e.g., yoga and art workshops), communal meals, daycare services to promote parental respite, or simply moments of leisure, thus nurturing a sense of belonging within an informal setting. The original objectives of the center included fostering the parents’ empowerment and social integration. To realize this philosophy, at the time of the center’s founding, the initiators considered consulting parents about the center and developing a parent committee (Risler and Marielle 2013). In such a context, parents are viewed as partners in the services offered, given that they are the experts on their own life experiences. They are in the best position to influence the center’s planned offerings and to act in order to diminish the harmful effects of children’s exposure to substance abuse. A discussion group was held in 2009 with seven current or former drug users to help determine the optimal interventions to be offered at the center (Venne et al. 2009). Hence, this interest in nurturing parents’ participation was already displayed by the managers and counsellors on the RP Development Committee.

On the ground, a project manager is responsible for running RP, and a dozen counsellors from the health and community network, who are “on loan” from their home institutions,1 work with the parents who come to the center. A Steering Committee composed of a manager representative for each partner organization oversees the project and its continuation, including human resources and the center’s budget. The individuals targeted for intervention, the eligibility criteria, and the terms of access to RP were set out in a service agreement signed in 2015 by the partner organizations. The agreement mentions that the center is intended for “pregnant women and parents of young children (0–5 years old) with psychoactive drug problems (whether current, recent, or previous with a risk of relapse).”

An innovative structure in Montreal and indeed in Quebec, RP was inspired by similar initiatives that seem to have proven worthwhile elsewhere in the country. The evaluative research conducted on the Breaking the Cycle (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) and Sheway (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) projects, for example, has demonstrated multiple positive effects for mothers and their children (Leslie 2007; Motz et al. 2006; Poole 2000). However, these centers do not seem to embrace a participatory management approach that would enable parents to influence and define the services they receive, as envisioned at RP.

Users’ participation in the decision-making spaces that concern them comes up against many issues and challenges in the field, particularly for marginalized populations. Individually speaking, participating in decision-making spaces requires time and some prerequisite learning which, as we will see further on, may go well beyond individual participation in the therapeutic process. Prior to actively participating as users, upon their arrival at a center, many participants lack self-confidence and have a low sense of competence (Motz et al. 2006; Poole 2000; Greene 2007; Tremblay and Olivet 2011). In addition, service users undergoing opioid replacement therapy appear to suffer from significant stigma (Tremblay and Olivet 2011). However, even if the experience of participating is fraught with many issues, it seems to generate many benefits, both individually and collectively, when the conditions are favorable to recognition, equality and reciprocity (Tremblay and Olivet 2011). Nevertheless, few studies document the benefits of such participation for service users, service providers, and intervention offerings.

This article presents a participatory action research (PAR) initiative conducted with counsellors and parents at the RP center. The intent was to stimulate reflection with these two groups of actors in order to be able to document how moments of discussion would impact the parents’ participation, personal journeys (at the center and in their daily lives), and RP’s planned interventions.

2. Methodology

2.1. Process

As mentioned earlier, at RP’s inception, the Development Committee considered the creation of a parent committee. However, in spite of this organizational will, the form of the committee was not defined and no human resources were planned to support the development of such a participatory mechanism. Our research team initiated the participatory action research (PAR) initiative precisely to support this wish on the part of RP to give voice to the parents.

From November 2014 to May 2015, a group of parents took part in eight meetings, and a counsellor team from RP participated in three meetings. Two pooling meetings with all these individuals and certain members of the research team were also held in order to share ideas. The initiative as a whole was facilitated by two members of the research team, one of whom was a community organizer with experience in group facilitation who worked for Quebec’s Integrated University Health and Social Services Centres (CIUSSS). Both team members used various facilitation tools—which were either custom-developed or borrowed from popular education practices such as photolanguage (Ampleman et al. 1983)—in order to guide along reflections on the topic of participation, with a view to transforming individual voices into collective ones. The meetings were attended by nine parents, 14 counsellors, and the project manager; some attended very diligently, while others were more ad hoc. Additionally, five individual interviews were held with the parents eight months after the group meetings to complete the data collection process. The purpose of these interviews was to document the effects of their participation on various levels. The main criterion for selection was the parents’ diligence in attending the group meetings. Each parent received $20 for each meeting attended, whether collective or individual, and childcare services were made available.

2.2. Reference Framework

To address our research goals, we adopted two areas of analysis—based on two main concepts—to help understand parents’ participation at RP and the context surrounding this participation. The first area had to do with the parents’ level of participation. In this respect we draw on (Tremblay and Olivet 2011), who identify three possible levels of participation: (1) individual participation, which connects with the concept of the patient care partnership (Réseau Universitaire Intégré de Santé (RUIS) 2013) in which the patient becomes an “active agent in their own care” (Bourret 2009). The principles of this approach include recognizing patients’ experiential knowledge and regarding them as full-fledged members of the care team; (2) institutional participation, which entails users’ participation in defining service offerings in collaboration with counsellors and decision-makers (Tremblay and Olivet 2011). In this context, some use the term “co-construction” (Vaillancourt and Leclerc 2008); and (3) civic participation, which goes beyond institutional boundaries and touches upon broader social issues. More than just a consumer of services, the individual then attains the status of full-fledged citizen (Tremblay and Olivet 2011). Civic participation, which is often demanded by social actors, is viewed as a means for taking action and becoming a political subject, in response to a predominant sense of powerlessness under the liberal democratic system (D. Lamoureux 2008; J. Lamoureux 2008; Parazelli and Latendresse 2006). In this case, the parents formed a collective subject-actor, which Duperré defines as “a group of people organized and mobilized around a common project based on their converging experiences, interests and solidarities” (Tremblay and Olivet 2011). The second area of analysis more specifically dealt with the contextual factors surrounding participation. A number of structural barriers may be encountered by users during a participatory experience. Overcoming this limitation requires working to transform the limiting conditions in question, which are viewed as injustices. This brings into play what Nancy Fraser calls “participatory parity” (Fraser 2005), which has three dimensions: (1) distribution (the economic dimension, which concerns access to resources and acceptable living conditions); (2) recognition (the sense of having a place in society, of being socially useful); and (3) representation (in other words, the political dimension of life in society: being among those who are able to influence, deliberate and decide on the common matters that concern them) (Fraser 2010). The question thus arises of whether belonging to a parent group at RP would help involved individuals feel better equipped (i.e., resources), more valued (i.e., recognition), and/or better represented in terms of their own interests (i.e., citizenship).

2.3. Analyses

Our extensive interactions with the individuals in the field in order to document the contextualized phenomenon of parental participation at RP in some ways resemble an ethnographic study (Olivier de Sardan 1995). We adopted a “comprehensive” posture by being immersed in the phenomenon in order to be able to grasp meanings and workings (Mucchielli 2007). As such, our understanding of this participatory experience evolved over the course of the research project in relation to our original theoretical references.

All group meetings and individual interviews were transcribed verbatim, over the course of the initiative, for analytical purposes. Research meeting minutes and field notes were recorded in a logbook. The entire data corpus was subject to thematic coding in order to identify key themes. These themes evolved over the course of the PAR. Indeed, the participants provided new content on their experience at the center. For example, what they said about participation at the first meeting might have a different meaning at the eighth meeting, given all that they had experienced in the intervening months. Subsequent analytical work was done to construct the meaning while taking timeframes into account. We also condensed the data based on annotations of the verbatim transcriptions. Summary tables were produced for each group meeting (parent, counsellor and pooling meetings) and for individual interviews.

A meeting to validate the results was held in June 2016 with the parents, the counsellors, and the project manager. The Steering Committee was also invited.

3. Results

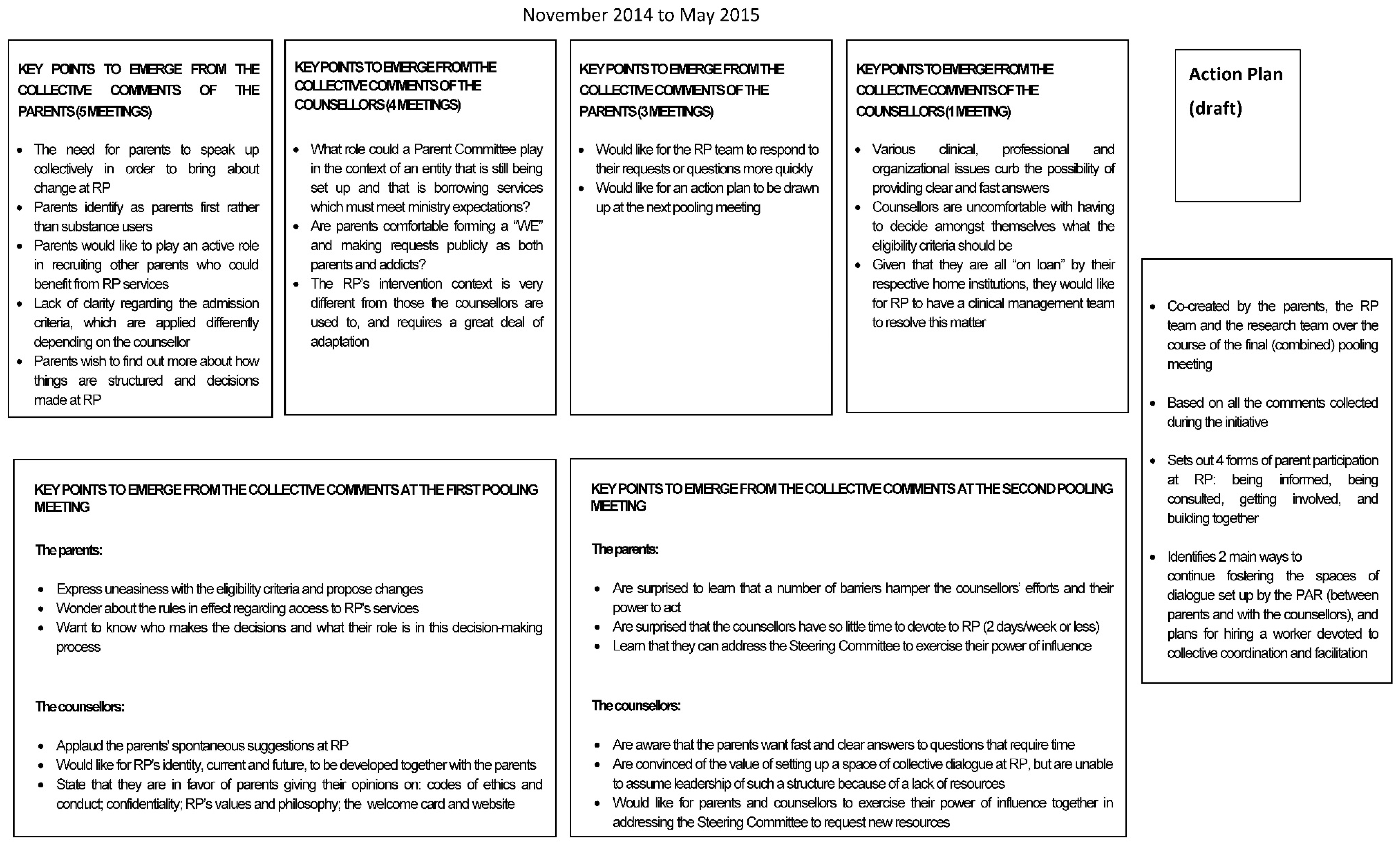

The next section presents the elements that emerged from the discussions with the parent group and with the counsellor group from November 2014 to May 2015. Specifically, it relates the key moments and reflections that proved significant in connection with our three research goals. We will describe the contents of the parent and counsellor meetings up to the first pooling meeting between both groups halfway through the initiative, and then up to the second pooling meeting at the end of the initiative. Figure 1 gives an overview of the initiative at large.

Figure 1.

The initiative.

3.1. First Part of the Initiative: The Five Meetings with the Parents

The parents stated that they came to the RP to meet with counsellors who would support them in their parenting role; their identity as parents superseded their identity associated with addiction. From the first meeting, the parents’ outlook on participation underscored the importance of speaking up in order to effect change, and of doing so collectively in order to share ideas and find greater strength in numbers. They were curious to find out more about the operational and decision-making structure at RP. From the outset, they stated that participating means being able to promote the resource and to invite people in their circles whom they think could benefit from RP’s services. However, when sharing their admission experiences and the situations of exclusion they had witnessed, the parents found that the admission criteria were unclear and seemed to vary from one counsellor to another. They also questioned the notion of “risk of relapse” which appears in the RP’s official documents. Furthermore, they pointed out that all parents do not appear to be introduced to RP the same way. When they invite parents to an initial visit, some counsellors do not tell them that the center is for parents with substance abuse problems.

3.2. First Part of the Initiative: The Four Meetings with the Counsellors

The counsellors were concerned about the actual role a parent committee might play in a context where the organization was still being set up and its operating modes remained to be defined. According to some counsellors, RP represented a different intervention context compared to their respective institutions. They were aware that they were being “loaned out” in accordance with very specific mandates, and that they had to meet ministry expectations. Consequently, they wondered about the committee’s latitude for shaping the center’s service offerings and more broadly its orientations, which had already been officially approved at another level. In the counsellors’ opinion, the parents face another challenge in this context, namely presenting themselves as both addicts and parents. Sitting on a parent committee and making requests could potentially confront them with having to embrace this dual status publicly, and having to create a “We”, which does not go without saying. In light of these observations, the counsellors were aware that they would have to follow up with parents to promote their diligent involvement as members of a parent committee. Given that the counsellors already struggle to foster involvement in the therapeutic relationship, they wondered about parents’ ability to succeed in this regard.

3.3. First Part of the Initiative: The Pooling Meeting between the Two Groups

Importantly, at the beginning of the meeting, it was clarified that the intent of the pooling meetings was not to come up with answers on the spot. Instead, both groups would jointly decide at the end of the meeting on the mechanism they wished to adopt in order to respond to their mutual questions. The research team clarified that it would not bear the responsibility for this mechanism.

The parents related to the counsellors how uneasy they felt with the eligibility criteria and they proposed changes, including being able to continue to visit RP even if they are not using (given the risk of a relapse) and being welcome even if their child is above the age limit of six years old. They asked about the rules regarding access to transportation tickets and medical services, as they had noticed that such access seems to vary depending on the counsellor they are assigned. They wanted to know who makes the decisions and what their role might be in this decision-making process. The counsellors, for their part, expressed their admiration to the parents for their involvement in the research initiative. They told them their wish was for RP’s identity, current and future, to be defined not just by the counsellors but by the parents as well. They also stated that they were very much in favor of parents sharing their opinions on the center’s code of ethics, code of conduct, confidentiality matters, values and philosophy, recruitment methods, and website.

3.4. Second Part of the Initiative: The 3 Meetings with the Parents

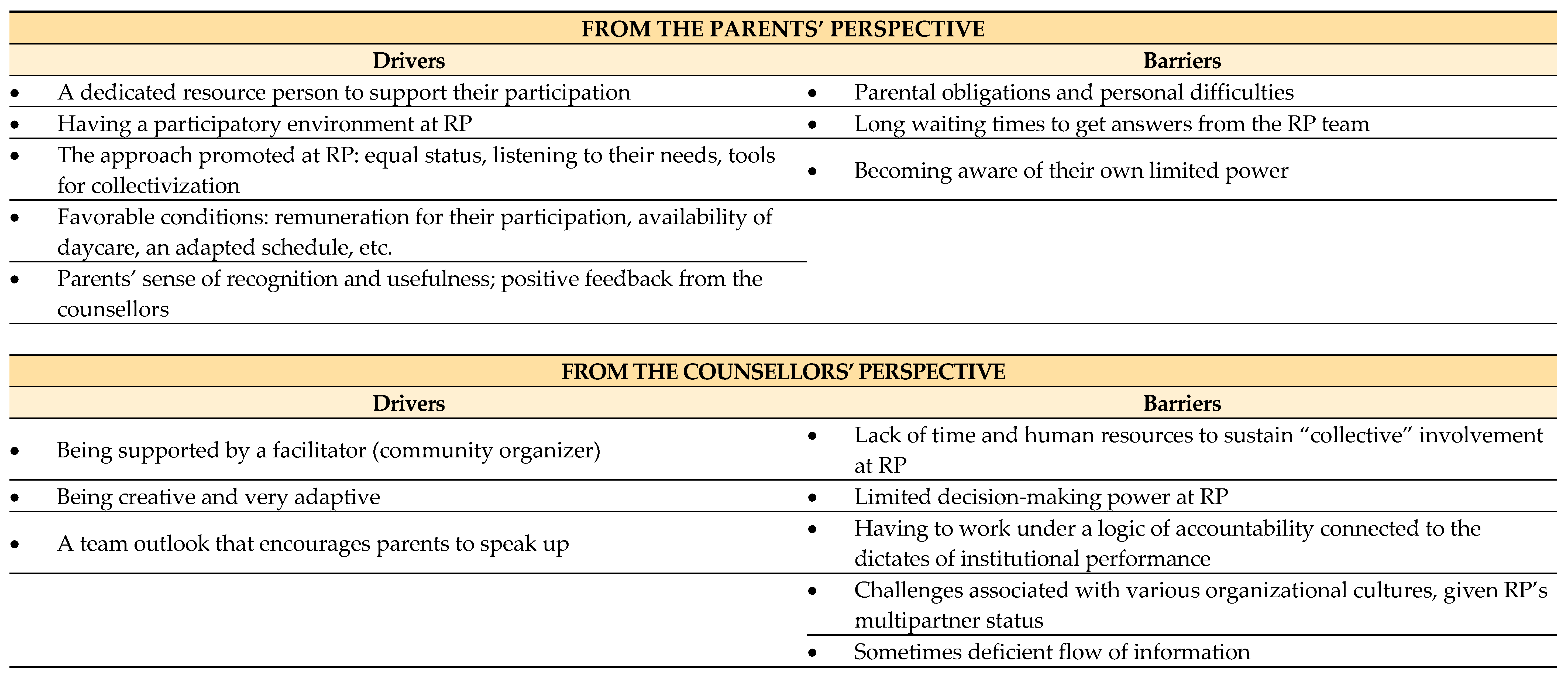

Following this pooling meeting, the second part of the research study was undertaken. In this stage, the researchers invited the parents to reflect on drivers of and barriers to participation. These elements are listed in Figure 2. Over the course of these reflections, the parents showed some skepticism about being able to hold another pooling meeting with the counsellors, as they found that their requests were not being addressed. They did not understand why the issue of inclusion criteria had not yet been settled by the Steering Committee in spite of the openness RP had shown for some time. They expected for concrete courses of action to be proposed by the end of the initiative.

Figure 2.

What are the drivers of and barriers to parents’ participation at RP?

3.5. Second Part of the Initiative: The Meeting with the Counsellors

The counsellors were also invited to reflect on drivers of and barriers to parents’ participation (Figure 2). Among other things, they mentioned that a number of clinical, professional, and organizational issues prevented them from providing parents with answers. They felt uncomfortable with having to decide amongst themselves what the eligibility criteria should be, and considered that this was not their responsibility. They would have liked for RP to have a clinical management team to resolve the matter. At the beginning of the initiative, the counsellors were convinced more than ever of the value of setting up a space of collective dialogue at RP. However, owing to a lack of resources, they were unable to assume leadership of such a mechanism.

3.6. Second Part of the Initiative: The Pooling Meeting between the Two Groups

The parents were surprised to learn that a number of organizational, clinical and structural barriers hampered the counsellors’ efforts and their power to act. They were also surprised that counsellors had so little time to devote to RP (2 days/week or less). They also discovered that they could address the Steering Committee in order to exercise their power of influence. Moreover, they mentioned their lack of familiarity with mechanisms of influence and participation, and their sense of being “subjected” to decisions that are made for them. For their part, the counsellors were sensitive to the fact that parents would like to have clear answers, especially concerning eligibility criteria, but pointed out that some of these answers must be developed together with the parents, and this requires time. Nevertheless, they reiterated that it is important for parents to have decision-making power and would like for them to join the counsellors in exercising their power of influence with respect to the Steering Committee in order to request new resources.

Being more familiar with the drivers and barriers encountered by their respective groups, the parents and counsellors drew up an action plan setting out possible forms of participation, along with actions and means by which to implement them. They proposed meeting regularly for “20 min” sessions, but several concerns were raised about the idea. Who would lead the sessions? When would they start? How often would they be held? What would be the committee’s goals? The two groups swiftly came to the conclusion that creating such a community would require the support of a qualified resource person to facilitate and coordinate a collective initiative of this kind.

3.7. Follow-Ups to the Research Initiative

As set out in the research protocol, our research team withdrew from the field after the second pooling meeting in May 2015. However, a number of actions related to the parents’ participation were undertaken after our initiative, in the year following the study. The first was the beginning of “20 min” parent meetings, called “the 20 min,” which were implemented at the end of the PAR initiative. Fourteen such meetings were held from January to May 2016. They were co-facilitated by a social work intern and by a member of the RP team. During this period, parents began a dialogue with the Steering Committee, via correspondence and meetings. Two round tables with the Steering Committee, parents, counsellors, and the project manager were facilitated by the community organizer (on our research team). A follow-up committee was formed to handle communication and follow-ups with each respective group of stakeholders. However, with the intern’s departure in June 2016, parent participation in the RP dissipated.

4. Discussion

The analysis presented here is based on what happened with the above-described PAR initiative, in conjunction with the content of the individual interviews with the parents and the group interview with the counsellors, held a few months after the initiative ended. Additionally, even if the meetings facilitated by the intern are not a source of our research data, per se, we do refer to their content when it relates to the PAR Initiative.

The first observation to note is that the PAR initiative prompted genuine participation from parents, that is, parental participation as RP users that went beyond merely attending the activities organized by the center. Throughout the meetings, the parents expressed their wish to improve services and to be able to make their own contribution, both in their own interest and in that of other families. This is despite the fact that, at first, stimulating parental involvement appeared to the counsellors as a challenge. Given the parents’ difficulty with involvement in their own journey as care recipients, the counsellors expected parental participation as users or as citizens to be even less likely. This assumption was born from their past experience with this complex “clientele,” which is echoed by the academic literature on the topic, namely the complexity of these parents’ living conditions, the many difficulties they face, and the risk factors behind their substance abuse problems, all of which may explain their low participation. Indeed, this situation can be seen, among other things, with the women involved in the Breaking the Cycle (Toronto, Ontario, Canada) and Sheway (Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) projects addressed to women with substance abuse problems (Leslie 2007; Motz et al. 2006; Poole 2000). Based on this literature and the RP team’s skepticism about the parents’ involvement, the question arises of what might explain the RP’s participatory success.

Part of the answer lies in the approach used to get parents involved. A number of previously identified drivers helped stimulate their engagement, such as remuneration for their participation, the availability of daycare during meetings, and the presence of a facilitator (community organizer) to lead the research initiative. Another factor was the counsellors’ attitude of openness, recognition and respect toward the parents. Over the course of both the pooling meetings and their interactions outside the research initiative, they showed that the parents’ input was relevant and influential with regard to ways of thinking and ways of running the RP. The initiative enabled the parents to interact among themselves and to rally around a positive initiative, and to choose to identify as parents first and foremost, which is very significant in light of the continual battle they must wage in order to resist substance abuse.

This observation about creating a collective entity may be connected to the three possible levels of participation in an institutional context as proposed by (Tremblay and Olivet 2011): (1) individual, i.e., being able to commit to a therapeutic journey; (2) institutional, i.e., getting involved as a user of a given resource; and (3) civic, i.e., bringing up questions and issues that go beyond the institution itself. In our view, the parents’ participation falls under levels two and three of the above typology. Through their various questions and requests in connection with RP, the parents focused on their own interests as users as well as defending the needs of other vulnerable parents with whom they interact in the community. Likewise, their participation can be situated at the user and civic levels when they ask for a human resource to facilitate the group while asserting their wish to act as stakeholders in recruiting new parents. Given that it goes beyond a logic of service alone, the parents’ engagement comes under a collective perspective, tying in with issues of citizenship. This does not mean that the participants did not also engage personally as individuals (first level), but merely highlights that, as a group, they mobilized at the two other levels of participation.

With respect to participatory parity as set forth by (Fraser 2005, 2010) in her theory of justice (the dimensions of redistribution, recognition and representation), the parents called for a better redistribution of services for all parents struggling with addiction. In fact, when they were able to change one of the eligibility criteria, namely by allowing RP parents who no longer have a substance problem to come to the center, they scored gains in terms of redistribution. Even if these gains may have been limited, they bear witness to their engagement in this direction.

With respect to recognition, the mere fact of getting involved helped foster a greater sense of being recognized. Becoming a collective subject-actor, as defined earlier (Duperré), represents a significant step toward emancipation, as noted by (J. Lamoureux 2004), who examines the becoming-subject of the most excluded and marginalized individuals. The creation of a place to voice views as users/citizen-parents, and the presence of all the counsellors during the pooling meetings, undoubtedly contributed to the parents’ sense of recognition.

However, regarding the third dimension in Fraser’s theory of justice, parity of representation, our assessment is mixed when it comes to the parents’ progress with participating in decision-making spaces. Even if some progress can be seen when looking at the initiative as a whole, it was only possible to agree to the requests of the parents insofar as they did not challenge the organization’s mission, budget and planned offer of services. No transformation was seen in the organization’s operating modes, and no mechanisms set up to support parental participation on a continuing basis.

Based on these observations, it appears worthwhile to reframe our PAR in the broader context of participation today, and the barriers confronting service users as those “primarily concerned” by the services and programs addressed to them. Participation in a new public management context tends to be limited to brief moments of consultation and discussion (Blondiaux 2008). Even when the promoters appear, at first, to call for participation, this potential participation is fraught with many disparities, which may be seen as structural barriers to greater participatory parity between users. Participatory non-parity in fact often resides in the structure itself, when those primarily concerned have no access to decision-making spaces, even if they are able to assemble. Is this the case here?

At the center’s inception, the RP Development Committee was open to parental participation. However, parents’ actual participation was limited. The first reason for this is the RP’s structure as a multipartner and service agreement-based resource open two days per week (and only one day in its first two years of operations). In the field, both intervention and the management structure are shaped by partners with distinct organizational cultures, mandates and practices. In this context, both stakeholder groups, i.e., the parents and the counsellors involved in the PAR, observed over time that their power at RP was limited. Ultimately, it emerged that the parents viewed the resource as a center that provided a living environment, whereas the initial structure was a service agreement to loan out staff for one and then two days per week, thus limiting the development of such a structure. The second explanatory factor is the defective information flow at the center. For example, RP lacked any literature documenting the services available to parents, the roles of the different actors and partners involved, the center’s decision-making structure, etc. Moreover, communication between the Steering Committee, the RP team and the parents did not always seem fluid. Information sharing is a key issue when it comes to facilitating genuine participation, as a great deal of research on civic participation has shown (Greene 2007; Esau 2007; MacNeill 2009; McDaid 2009).

Study Limitations

We were unable to carry out some of the ideal phases of a PAR. In this type of study, it is desirable to incorporate the individuals primarily concerned throughout all phases of research (Anadón and Savoie-Zajc 2007). It was not possible, in our case, to involve parents from the very beginning, given that the resource was just being set up and no parents were using it yet at the time the research protocol was being drawn up. Another important limitation is that the members of the Steering Committee were not involved as partners in the PAR. The research team assumed, at the start of the initiative, that the RP team would communicate information on the initiative and on the parents’ requests to the Steering Committee. However, for various reasons, the Steering Committee was not always aware of what was going on with the PAR. It is worth noting that, due to major changes taking place in the structure of the health network as a result of a Quebec government policy, the members of the Steering Committee did not convene during the PAR. Moreover, when the members of this committee began to meet once more after the PAR ended, they did not immediately understand the importance of the PAR at the center, and more specifically that the parents had written an action plan and had demands regarding the admission criteria and other issues. Only a few months later, via the activities subsequently organized by the social work intern and a member of the RP team, did the Steering Committee realize the scope, importance, and effects of this initiative in which the parents had been involved.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, it appears important to recall that the RP was initiated in the midst of a reform of the health and social services network in Quebec, Canada. This reform is a prime example of participatory spaces for users being shrunk in favour of centralized decision-making by ministries. The organizational logic of the health network in Quebec, Canada is one which, even before the reform, was founded on a top-down management approach. Accordingly, even if the results uncover certain shared observations by different groups regarding organizational and policy-related problems (e.g., the eligibility criteria), it would have been surprising for the counsellors or the managers to be able to respond any differently to the requests for non-standard participation. It was impossible for RP stakeholders to make changes, at least as quickly as the parents would have liked. The accountability and efficiency requirements that apply to a resource such as RP take predominance over any requests for participation. Nevertheless, even if our assessment is mixed in terms of the power of influence in such spaces, it remains important to continue working with different groups of actors on doing things differently, and on creating alternative spaces that allow for this kind of experimentation. By opening a window on an approach that usually attracts little recognition, this initiative can serve as a model for user committees wishing to pursue a co-creation of knowledge. Finally, it is worth noting that a transformation in organizational culture takes time, and a will to work on expanding the participation of those primarily concerned. The feedback we received about RP in winter 2018 shows how parents can be rallied as active agents and can benefit from the recognition of the other partners involved.

Author Contributions

I.L., J-F.R. and N.G. helped develop the research design, interpret the results, and write the article. R-È. D. (the community organizer working for the CIUSSS) and I.M. facilitated the groups with the parents and with the Counsellors. F.M., a clinical activities specialist with the CIUSSS addiction program, coordinated between the research team and the RP counsellor team. F.M. and R-È. D. provided valuable support for interpreting the results.

Funding

This study was supported by a $42,000 grant linked to the Rond-Point project, which is funded by the Lucie and André Chagnon Foundation and Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| RP | Rond-point |

| PAR | participatory action research |

References

- Ampleman, Gisèle, Gérard Doré, Lorraine Gaudreau, Claude Larose, Louise Leboeuf, and Ventelou Denise. 1983. Pratiques de conscientisation: Expériences d’éducation populaire au Québec. Montréal: Nouvelle Optique, pp. 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Anadón, Marta, and Lorraine Savoie-Zajc. 2007. La recherche-action dans certains pays anglo-saxons et latino-américains: Une forme de recherche participative (Action Research in Certain Anglo-Saxon and Latin American Countries: A Form of Participatory Research). In Recherches Participatives: Multiples Regards (Participatory Research: Multiple Perspectives). Edited by Anadón Marta. Québec City: Presses de l’Université du Québec, pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bellot, Céline, Maryse Bresson, and Christian Jetté. 2013. Le travail social et la nouvelle gestion publique (Social Work and New Public Management). Québec City: Presses de l’Université du Québec, pp. 1–264. [Google Scholar]

- Blondiaux, Loïc. 2008. Démocratie délibérative vs. démocratie agonistique? Le statut du conflit dans les théories et les pratiques de participation contemporaines (Deliberative Democracy vs. Agonistic Democracy? The Status of Conflict in Contemporary Theories and Practices of Participation). Raisons Politiques 30: 131–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bourque, Denis. 2009. Transformation du réseau public de services sociaux et impact sur les pratiques des intervenants sociaux au Québec (The Transformation of the Public Network of Social Services and Its Impact on Social Workers’ Practices in Quebec). Gatineau: Université du Québec en Outaouais, Cahiers de la CRCOC, no 0907. [Google Scholar]

- Bourret, Christian-Jean. 2009. Évolution du rôle des patients et nouvelles organisations d’interface en santé. Éléments pour une approche comparée (The Evolution of Parents’ Role and New Interface Organizations in Healthcare. Some Elements for a Comparative Approach): France, Royaume-Uni, Catalogne (Espagne). Recherches en Communication 32: 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Couturier, Yves, Dominique Gagnon, and Sébastien Carrier. 2009. Management des conduites professionnelles par les résultats probants de la recherche. Une analyse critique (Managing Professional Conduct Using Evidence-Based Data. A Critical Analysis). Criminologie 42: 185–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couturier, Yves, Dominique Gagnon, Louise Belzile, and Abdoul Aziz Gbaya. 2013. Pratiques professionnelles fondées sur les résultats probants de la recherche et travail social (Professional Practices Drawing on Evidence-Based Data in Social Work). In Le Travail Social. Québec City: Presses de l’Université du Québec, pp. 1–464. [Google Scholar]

- Lamoureux, Daniel. 2008. Démocratiser radicalement la démocratie (Radically Democratizing Democracy). Nouvelles Pratiques Sociales 21: 121–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, Alain, and Luc Farinas. 2009. Une critique des modes managérialistes dans la gestion des organisations de services humains complexes de santé et de services sociaux (A Critique of Managerialist Methods in the Management of Complex Health and Social Services Organizations). Cahier de recherche du Cergo 2009-02. Paris: Cergo, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Esau, Michelle V. 2007. Citizen Participation and the Poor: A Participatory Approach to Achieving Political, Social and Economic Freedom? Politikon 34: 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewan, Ferlie. 2017. Business Policy and Strategy in the New Public Management Studies. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, Nancy. 2005. Reframing Justice in a Globalizing World. New Left Review 36: 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, Nancy. 2010. Qui compte comme sujet de justice? La communauté des citoyens, l’humanité toute entière ou la communauté transnationale du risque? (Who Counts as a Subject of Justice? National Citizenry, Global Humanity, or Transnational Community of Risk?). Rue Descartes 67: 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, Saara. 2007. Including young mothers: Community based participation and the continuum of active citizenship. Community Development Journal 42: 167–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, Pierre, and Bernard Jouve. 2006. Un modèle québécois? Gouvernance et participation dans la gestion publique (A Quebec Model? Governance and Participation in Public Management). Montréal: Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, pp. 1–142. [Google Scholar]

- Lamoureux, Jocelyne. 2004. On est des entêté(e)s. Pensez pas nous épuiser (We’re Stubborn. You Can’t Wear Us Down). Lien Social et Politiques 51: 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamoureux, Jocelyne. 2008. Paroles divergentes, scènes inédites; subversions égalitaires: Réflexion sur la subjectivation politique (Diverging Words, Unprecedented Scenes; Egalitarian Subversions: Reflection on Political Subjectification). In Vivre à la marge, Réflexion autour de la souffrance sociale (Living on the Margin, A Reflection around Social Suffering). Collection Société, cultures et santé. Québec City: Les Presses de l’Université Laval, pp. 213–37. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, Margaret. 2007. Synthèse du programme Breaking the Cycle, vol. 1: Les origines des relations (Breaking the Cycle Compendium, Vol. 1: The Roots of Relationship). Toronto: The Mothercraft Press, pp. 1–159. [Google Scholar]

- MacNeill, Virgina. 2009. Forming partnerships with parents from a community development perspective: Lessons learnt from Sure Start. Health & Social Care in the Community 17: 659–65. [Google Scholar]

- McDaid, Shari. 2009. An equality of condition framework for user involvement in mental health policy and planning: Evidence from participatory action research. Disability and Society 24: 461–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motz, Mary, Margaret Leslie, Debra J. Pepler, Timothy Moore, and Patricia A. Freeman. 2006. Breaking the Cycle: Measures of Progress 1995–2005. Journal of FAS International 4: e22. [Google Scholar]

- Mucchielli, Alex. 2007. Les processus intellectuels fondamentaux sous-jacents aux techniques et méthodes qualitatives (The Fundamental Intellectual Processes Underlying Qualitative Techniques and Methods). Actes du colloque Bilan et prospective de la recherche qualitative. Recherches Qualitatives, Hors Série 3: 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Olivier de Sardan, Jean-Pierre. 1995. La politique du terrain (The Policy of Fieldwork). Enquête, No 1. Available online: https://enquete.revues.org/263 (accessed on 4 January 2017).

- Parazelli, Michel, and Anne Latendresse. 2006. Penser les conditions de la démocratie participative (Pondering the Conditions for Participative Democracy). Nouvelles Pratiques Sociales 18: 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, Nancy. 2000. Evaluation Report of the Sheway Project for High-Risk Pregnant and Parenting Women. Vancouver: British Columbia Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health, pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Réseau Universitaire Intégré de Santé (RUIS). 2013. Guide d’implantation du partenariat de soins et de services. Vers une pratique collaborative optimale entre intervenants et avec le patient (Care and Service Partnership Establishment Guide. Towards Optimal Collaborative Practice between Professionals and with the Patient). Comité sur les pratiques collaboratives et la formation interprofessionnelle. Montréal: Université de Montréal, pp. 1–66. [Google Scholar]

- Risler, Isabelle, and Venne Marielle. 2013. Centre Périnatal et Familial de Toxicomanie (CPFT). PowerPoint Presentation to the MD of the Centre de Santé et de Services Sociaux Jeanne-Mance. Available online: http://www.cremis.ca/le-rond-point-centre-perinatal-familial-en-toxicomanie-construire-un-espace-parents (accessed on 8 January 2015).

- Tremblay, Mireille, and Frabrice Olivet. 2011. De la participation citoyenne à la reconnaissance du droit au plaisir: Insertion sociale et droits des usagers des opioïdes (Citizens’ Participation in Recognizing the Right to Pleasure: The Social Integration and Rights of Opioid Users). Drogues, Santé et Société 10: 169–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillancourt, Yves, and Philippe Leclerc. 2008. Note de recherche sur l’apport de l’économie sociale dans la coproduction et la coconstruction des politiques publiques (Research Note on the Contribution of the Social Economy in the Coproduction and Coconstruction of Public Policies). Collection Études théoriques, copublication CRISES/Innovation sociale et développement des communautés (ARUC ISDC). Gatineau: Université du Québec en Outaouais, pp. 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Venne, Marielle, Lecompte Jocelyne, and Lauriault Ghislaine. 2009. Des soins et des services intégrés pour les parents toxicomanes et leurs enfants. Centre perinatal et familial de toxicomanie. Montreal: Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal, pp. 1–35. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The partners that signed the service agreement (2015) were the Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM), the Centre de santé et de services sociaux Jeanne-Mance (CSSS JM), the Centre de réadaptation en dépendance de Montréal-Institut universitaire (CRDM-IU), Dans la Rue, the Centre de recherche et d’aide pour narcomanes (CRAN), Portage, the Centre de pédiatrie sociale Centre-Sud (CPS-CS), the Centre Jeunesse de Montréal-Institut universitaire (CJM-IU) and the Agence de la santé publique du Canada (ASPC)/Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).