Abstract

This article examines recent aggregate statistical data generated by Scottish Government medical bodies concerning suicide rates and the social contexts of those who die by suicide. It compares rates and trends with international studies. Inherent in the data sets explored are indications suggesting that suicide is patterned by variables such as gender, employment, class and marital status. Neoliberalism increases social disparities that influence patterns of suicide, resulting in anomie and alienation, disproportionately impacting the already disenfranchised. Using recent statistical data (2011–2017), the article offers a theorization of suicide through the lens of Emile Durkheim’s social causation model of suicide. Suicide is associated with risk factors inherent in social structures and political processes.

1. Scottish Context

Suicide is one of the ten most frequent causes of death among adults in western industrialized countries, and among younger adults (15–35) suicide is the second most frequent cause of death (Bronisch 2015). Suicide can be examined over time and under different political regimes rather than in terms of individual pathology. Durkheim’s contribution to understanding suicide as a sociological phenomenon grapples with social structures and their differential impacts on those who have died by suicide (Tomasi 2000). He believed there were sociologically significant qualitative differences between suicide rates (Poggi 2000, p. 63). Suicide through a Durkheimian lens does not analyze in terms of individual pathology that exists independently of an array of social structures, particularly for disenfranchised groups most exposed to the adverse effects of Conservative-led neoliberal policies in Britain. Shaw et al. (2002) demonstrate that during periods of Conservative government there were social, economic and political factors affecting suicide. Neoliberalism casts the Welfare State as the enemy of freedom, privileging corporate and private interests supported by minimal taxation and prioritising profit and personal wealth (Hall 2011). Neoliberalism as an economic model arose in the 1980s under Prime Minister Thatcher who argued there was no ‘common good’ and that society was a fiction. Thatcher altered supportive social structures, abolishing local tax rates and replacing them with a ‘poll tax’ which intensified inequalities, while cuts in income for local councils hampered their effectiveness in combatting poverty. Changes in council housing policies led to segregation as many could not afford to purchase their rented housing unit whilst flexible working legislation made working-class employees significantly less secure (Steger and Roy 2013).

The suicide data set, compiled by Scottish government bodies, relied upon in this article, covers the period 2011–2017 in Scotland. The research question which this paper grapples with is: What do official statistics, created by the government on suicide occurring in Scotland, reveal about connections between social structures and suicide? In Scotland suicides are three times more likely among those living in the most deprived communities, including rural areas (Levin and Leyland 2005, p. 2888; NHS National Services Scotland 2016). The epidemiology of suicide in Scotland reflects substantial socio-economic and socio-democratic inequalities across the population (NHS National Services Scotland 2018, p. 6). Stark et al. (2008) found the greatest rise in suicide in Scotland was among the most deprived areas widening existing social disparities and, they argued, Scottish Government policy on tackling social exclusion was a factor in helping reduce suicide rates among young men. Using publicly available data, we present evidence to explore the argument that a Durkheimian perspective offers a valuable lens to understand patterns of suicide in Scotland. The contribution of this study lies in its utilization of official data regarding suicide rates in Scotland, combined with a secondary qualitative analysis informed by Emile Durkheim’s account of four types of suicide (see Moore 2016). Egoistic suicide occurs when persons feel they are not well integrated into a society, which the community also signals. The person is isolated and without moral guidance. They are reliant upon their own resources (Parkin 1992, p. 16). Egoistic suicide relates to individualism where bonds with others are loosened (Poggi 2000, p. 70). Anomic suicide arises when there are serious disruptions to how society is regulated, for example during economic or social crises that engulf individuals leaving them without clear norms about how to adjust and unclear social expectations, so moral guidance is weak. Altruistic suicide arises from being over-regulated into a community which causes pressures to succeed and to please. This person may commit suicide in order to support their community, or after they fail, turn to suicide out of respect for the values of the group which they identify with and do not wish to burden. Parkin (Parkin 1992, p. 16) suggests altruistic suicide is more common in the military than the civil society. The group to which such suicide victims belong is the chief focus of their preoccupations (Poggi 2000). In some cultures, women are expected to commit suicide on the death of her partner (Scott 2014). Under altruism, the individual “does not belong to himself” Durkheim proposes (Durkheim [1897] 2006, p. 239): What guides his behavior lies outside the individual.1 Finally, fatalistic suicide occurs when the regulation of society or community is over-controlling or very controlling (see below).

In Scotland, between 2009 and 2014, 71% of deaths by suicide were by unmarried/not partnered men (NHS National Services Scotland 2016). A Scottish national survey discovered those who had the best mental health reported the least stress in their lives, were under 55, lived in affluent areas and felt in control of factors in their lives affecting mental health (Glendinning et al. 2002). Middle-class, professional managerial groups who felt they could manage their income and without long-standing health problems also scored highly. Reported stress levels were high among people, especially women, aged 35–54, and those who had experienced mental health problems. Mok et al. (2012), using national data about suicides in England, Wales and Scotland, 1960–2008, found that in Scotland, trends in suicide rates increased markedly in recent decades compared with England. Between 2014 and 2018 the probable suicide rate was three times higher in the most deprived areas compared to the least deprived areas (NHS National Services Scotland 2018). There are marked differences by social class in suicide and area: In Glasgow, for instance, the suicide rate was significantly higher than the Scottish average between 1989 and 2004 (Platt et al. 2007). Levin and Leyland (2005) found that between 1981 and 1991, rates of suicide in Scotland increased. For 1995–1999, the highest were in remote rural areas, the risk being higher especially for young males relative to the risk young males faced in urban areas. Physical isolation from social networks and support services and a culture of self-reliance are thought to heighten depression and anxiety in rural areas (Rural Poverty and Exclusion Working Group 2001). Furthermore, during the period 1996–1997, the increase in the proportion of deaths by suicide in Scottish rural areas coincided with blows to the Scottish rural economy arising from diseases affecting cattle and sheep exports (Levin and Leyland 2005, p. 2887). Suicide has a socio-emotional structure linked with larger social factors which Durkheim’s types of suicide attempt to mirror (Abrutyn and Mueller 2014).

2. Literature Review

Durkheim’s ([1897] 2006, p. 19) definition is that “Suicide is applied to all cases of death resulting directly or indirectly from a positive or negative act of the victim himself, which he knows will produce the result”. He argues people from different religions and classes destroy themselves in different proportions. Decline in social regulation increases anomie-related suicide (Bradatan 2007). Anomic suicide is the ultimate expression of earlier experiences in the life of the person and the way in which individuals organize their lives. Weak regulation is a key feature of its causation. The expression of anomie in Durkheim is one of relative isolation, disorientation, loneliness and feelings of separateness from the group (Travis 1990). Such social changes would be intensified by the introduction of a neoliberal social order where capitalist markets, privatization and individualism negatively impact collective life and welfare support through the public sector. Parkinson et al. (2017) cite Scotland’s higher mortality rates compared with all other Western European countries as well as wider health inequalities, noting that by comparison with the rest of Britain in 2001 only half these differences were explicable by deprivation.

For Durkheim egoism and anomie were major risk factors for suicide in industrial society (Travis 1990); Wray et al. (2011) note that most 20th-century research on suicide focused upon issues of integration and regulation. Durkheim dwells upon how negative meanings and emotions were produced within individuals and groups during dramatic social changes and how groups were made more vulnerable. His multi-dimensional scheme privileges social explanations of suicide. He devised a four-fold typology of suicide that is based upon the intersection of two major axes: Integration and regulation. By integration he means social belonging, inclusion through care, love, attachments, things that come from social ties (Durkheim [1897] 2006, p. 224). However, groups that tie together individuals through loyalty or love can also contribute to group suicide rates. These groups value the needs of the group over the individual’s need to survive. Social integration is where his key insight lies, and that idea remains influential. Durkheim was also concerned with regulation: The monitoring and guidance that comes with social ties, creating an external constraint that prevents a drift into states of despair.

These social forces of integration/regulation interact in a U-shaped way to form the basis of his four-fold typology of suicide. Suicide arises in social structures characterized by extremes. Egotistical suicide occurs when integration is low, altruistic suicide occurs when integration is high. Both suicide types represent situations where care deviates from moderate levels. Anomic and fatalistic suicide represent risk arising from social structures that respectively under- or over-regulate individuals. Previous scholarship is selective in terms of the dimension of Durkheim’s suicide theory examined. In this article, the focus concerns the application of Durkheim’s anomic and fatalistic suicide types regarding which there exists a rich literature.

Recent fluctuations in the labour market in industrial sectors are associated with suicide increase in black male suicide rates aged 15–34 (Wray et al. 2011, p. 512). Scourfield et al. (2012) sought to understand suicide in men. Employment problems and criminal activity are more often associated with suicide by men. Isolation and mental illness and problems relating to children are more common in female suicides. Debt problems are relevant to men and women. Relationship problems are especially relevant to male suicide. There is a traditional tie between financial problems, unemployment, relationship difficulties and male suicide across nations (Gorman et al. 2018; Scourfield et al. 2012; Stack and Wassermen 2007). Relationship breakdown is associated with suicide in men or boys when they split with partners or girlfriends. Marriage offers men greater protection from suicide than women (Stack 2000, p. 470). The reasons for this consistent finding admit of many interpretations: Companionship, emotional support, material provision or other factors may be protective of male wellbeing.

Durkheim argues that people from different religions and classes destroy themselves in different proportions. Groups with a good balance between individual initiative and communal solidarity have the lowest rates of suicide. Anomie suicide he saw as resulting from industrial and commercial upheaval or disorder. It occurs, he argues, when people no longer know the rules that apply over the business cycle. Anomie type suffering undermines self-control and orientation. For him, society has a “regulatory action” that affects “the social rate of suicide” (Durkheim [1897] 2006, p. 262). For Durkheim, it is economic crises that have an aggregating influence on suicide. Such crises disturb the collective order, the social body, and so people are more prone to kill themselves. Anomic suicide occurs when traditional rules have “lost some of their authority” (Durkheim [1897] 2006, p. 277). His analysis here and throughout demonstrates a rudimentary understanding of psychology. The discourse within which he couches his analysis of the suicide slides into a psychological explanation. This pattern suggests he faced a struggle to limit his focus to an exclusively sociological treatment.

Anomie is reinforced by the fact that passions are less disciplined at the very time when they need a stronger discipline: The less a person feels limited in his behavior “the more intolerable any limitation becomes” (Durkheim [1897] 2006, p. 278). For Durkheim, economic progress has led to the freeing of “industrial relations from any regulation”, before industrialization “a whole system of moral power was in place to discipline them” (Durkheim [1897] 2006, p. 279). That engenders suicide when “economic” changes occur. It is greatest within the industrial/commercial professions, occurring when “society is not sufficiently present” for individuals so there is little or no regulatory control. (Durkheim [1897] 2006, p. 284). There is also “domestic anomie” that occurs, for example, after the death of a spouse, or after divorce: Areas of high divorce rates also have high rates of suicide. (Durkheim [1897] 2006, p. 284). For men, marriage has a positive regulatory impact through controlling urges and bestowing moral wellbeing. The Scottish Government recommends that a major suicide challenge is to increase social integration and social capital, especially among vulnerable, socially excluded men (NHS National Services Scotland 2018, p. 14).

Durkheim describes fatalistic suicide as resulting from over-regulation, when people’s futures are blocked, aspirations denied, and their lives take place in highly controlling political situations (Stack 1979; Lester 1991). Bergen et al. (2009) found that, as Durkheim’s ideas on fatalistic suicide would predict, in the Netherlands, young immigrant women of Turkish, Moroccan and South Asian origin, whose lives were characterized by over-regulation giving limited agency, had higher rates of suicide attempts compared with Dutch young women. The Dutch women had greater autonomy than the immigrant women belonging to ethnic minority communities. Durkheim describes highly regulated and unrewarding lives as likely sources for fatalistic suicide: “futures are pitilessly blocked, and passions violently choked by oppressive discipline” (Durkheim [1897] 2006, p. 276). Marriage as a community is also protective, at least in the West. Widowed men and women kill themselves more than do married couples. By contrast, in rural China, where the rates are three times higher than urban rates for suicide, for young women (15–35), marriage is associated with fatalistic suicide, and unmarried women experience stronger social support and have lower risk factors, whereas Western data sets endorse Durkheim’s social integration theory of suicide (Zhang 2010). In China, married women experienced tight regulation, internal family tensions and have less easy access to external networks than unmarried Chinese young women.

3. Methodology

The methodology is premised upon a qualitative analysis of the most recent suicide rate data compiled by government bodies in Scotland and held in the Scottish Suicide Information Data Base (NHS National Services Scotland 2018).

During the period 2011–2017, 5286 individuals died from suicide in Scotland. The average annual suicide rate over this period was 14 per 100,000 people, just under three-quarters (73%) were male and just under three-quarters (73%) of suicides involved single, widowed or divorced individuals. About 47% of suicides were by people aged 35–54 at the time of death. The highest numbers and rates of suicide fall into this middle-age group. Suicide deaths were three times more likely to occur among those living in the most socio-economically deprived areas, than among those living in the least deprived communities. The Scottish authorities suggest that these “changes may reflect the impact of cultural, social and economic changes over time (‘period effects’) in interaction with characteristics of cohorts born in the 1970–1980s”, the period when neoliberalism was being entrenched (NHS National Services Scotland 2018, p. 13; Steger and Roy 2013).

4. Results

4.1. Gender and Suicide

It has been suggested that these cohorts of men, especially those living in more socio-economically deprived areas, were exposed earlier and more profoundly than other socio-economic groups to the negative consequences of neoliberal economic policies, including de-industrialisation, which had “lasting psychological and economic impacts through to middle age.” (NHS National Services Scotland 2018). Neoliberalism and de-industrialisation are themes that relate to deep social change and Durkheim’s worries about the impact of 19th-century industrialisation on wellbeing. Moreover, also resonating with Durkheim’s analysis of anomic suicide is the suggestion by this Scottish source that under-regulation left attached individuals at risk: Single and divorced people are over-represented in these data, and it is suggested “that non-married people are more likely to be socially isolated and ‘disconnected’ from their local community and wider social networks, situations which give rise to a higher risk of suicide” (NHS National Services Scotland 2018, pp. 13–14).

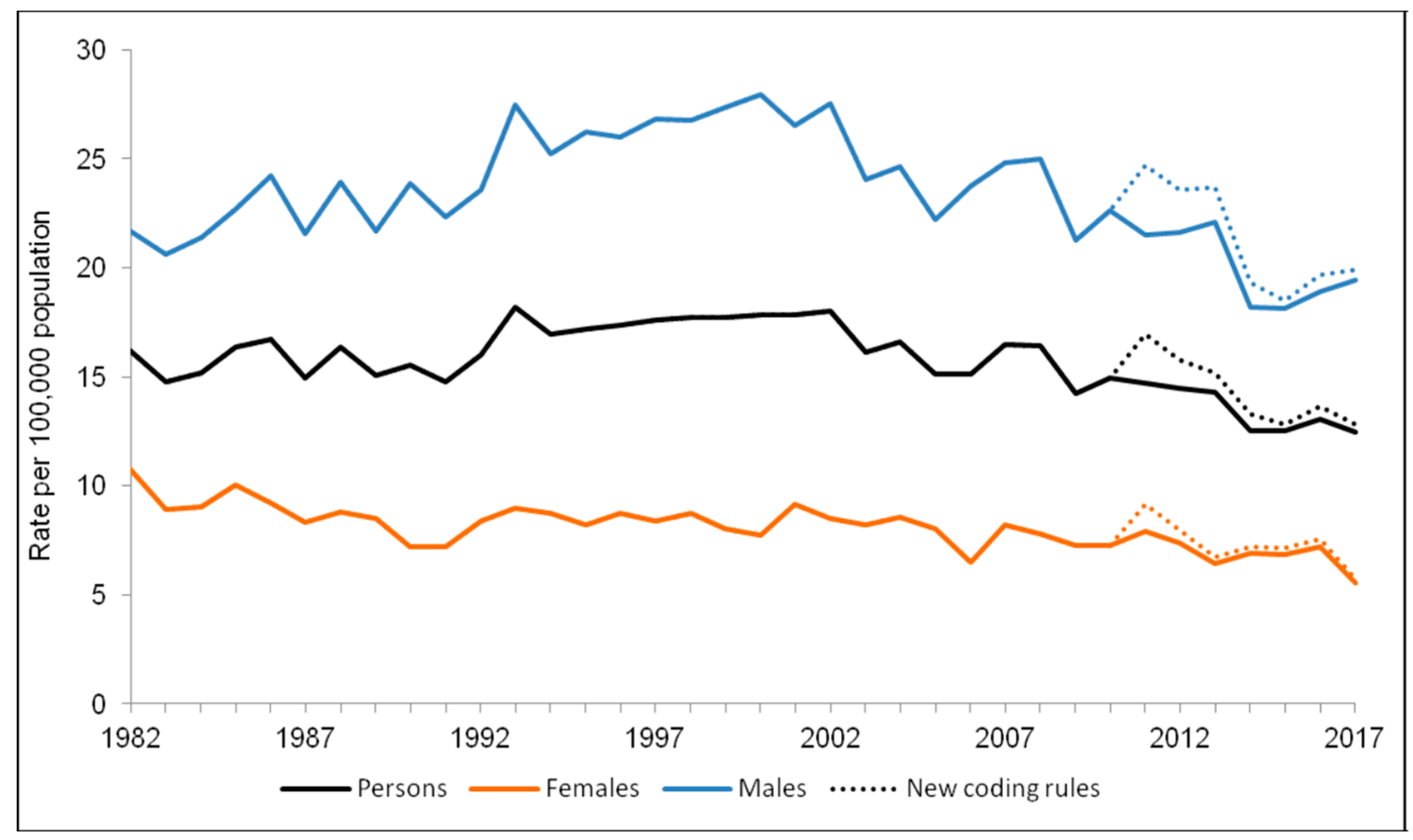

‘Probable suicides’ refers to deaths from intentional self-harm and events of undetermined intent. There were 680 probable suicides registered in Scotland in 2017. In Figure 1 the number of males (blue line) who died from suicide was 522 and the number of females (yellow line) 158. There is, therefore, a marked gender difference in suicide rates that are roughly consistent as a pattern over the period 1982–2017. Between 2013 and 2017, the probable suicide rate was more than two and a half times higher in the most deprived areas of Scotland. Most deaths were for men and women between 35–54. As these data stand using the prism of Durkheim’s anomie suicide, two points follow: Firstly, that males appear as less well integrated into the social order than females and thus they are subject to less regulation and attendant support, secondly, as there is a strong correlation for both genders with deprivation that suggests there is an experience of alienation and loss of purpose.

Figure 1.

Standardized rate of ‘probable suicide’ in Scotland, 1982–2017.2.

Taking the prism of fatalistic suicide, an alternative interpretation is to argue that males are more inclined to pessimism and resolve the depression that can accompany it by suicide. They perceive their future is more hopeless compared with women who may be inclined to utilize social support more readily. Anomic and fatalistic concepts of explanation are compatible with illuminating these standardized rates, 1982–2017. Blocked futures and aspirations denied are key dimensions of fatalistic suicide, where the experience of deprivation is likely to affect the sense of reward gained through daily living. Recent research into suicide deaths among Polish residents in Scotland during 2012–2016 found that of the 59 suicides (51 males, 8 females) Polish men had rates higher than indigenous Scottish men, mirroring the greater levels of suicide of Polish men living in Poland compared with Scottish men domiciled in Scotland (Gorman et al. 2018).

Based on Crown Office Record analysis of the NRS data, these researchers found the social contexts of both Polish and Scottish male suicide deaths shared key features: Unemployment or irregular work, shift and manual work, relationship problems and alcohol excess. The anomie coupled with the ‘migrant experience’ of difficulties integrating and with an unfamiliar culture was a general conclusion, one that Durkheim’s anomie thesis accommodates. Within Polish society, Gorman et al. (2018, p. 12) comment that the strong male suicide gender bias is connected with a crisis in the traditional “patriarchal family system” within Polish society: Men struggle with financial instability and feel inhibited from seeking support, leading to substance abuse, while Polish women, by contrast, are inclined to seek support, and confide in others. As hypothesized earlier, the male gender bias may also be explicable through the lens of fatalistic suicide.

4.2. Marital Status and Suicide

Consistent with Durkheim’s emphasis on the social integration contribution of marriage, many of the Polish suicides in Scotland involved “failed relationships prior to the suicide” (Gorman et al. 2018, p. 16). Marital status statistics are known for 5239 of the individuals in the 2011–2017 cohorts of suicides who were aged 16 and over (NHS National Services Scotland 2018, p. 19). Nearly three-quarters (73%) were reported as single, widowed or divorced at the time of their death. The remaining 27% were either married or in civil partnerships when they died. Compared with the general population of Scotland, as demonstrated through the Scottish census of 2011, those in this cohort were very significantly more likely to be single or divorced and less likely to be married than the general population. Durkheim’s anomic suicide suggests the 73% are characterized by limited regulation and attachments. As suicides in Scotland occur more frequently in deprived areas, this 73% of cases will include many who experienced de-regulation due to unemployment or poverty. Substance abuse and domestic violence are correlated with indexes of deprivation in Scotland, so the adversity they introduce would impact the capacity of individuals to access a more regulated existence situated within stable social groups (Scottish Government 2011, 2017a, 2017b; Millard et al. 2016).

Kyung-Sook et al. (2018) confirmed in a meta-analysis Durkheim’s anomic suicide premise that bonds matter and that marital status is an index of social integration within social structures, and a key predictor of suicide. Non-married men displayed a greater risk of suicide than married men. That status difference in terms of suicide was elevated for divorced men, suggesting the breakdown of established regulatory bonds was particularly damaging. They conclude that breaking the bonds between the individual and the marriage union increases suicide risk. Studies of suicide between 1996 and 2005 in Northern Ireland confirmed the importance of marriage as a protective factor for both genders, but the protection it gives is greater for men, with divorced young men being a group at high risk of suicide. The results of other studies present us with a mixed picture about the association between not being married and suicide: Men who never married were found at higher risk of suicide than those who were divorced, especially as these groups aged (Corcoran and Nagar 2010, pp. 798–99). Corcoran and Nagar (2010, pp. 798–99) tentatively conclude that “Durkheim’s hypothesis that marriage leads to greater social integration and more supportive social networks may be applicable to these findings”.

4.3. Employment Status, Occupation and Suicide

Durkheim believed that work and employment was advantageous to wellbeing and social integration (Khattab and Fenton 2009). Doherty (2017), however, describes the growth of a ‘precariat’, a new stratum of people loosely connected with the world of work through insecure, zero-hours employment, for whom the workplace no longer offers the moral integration that Durkheim imputed to earlier industrial forms of employment. Beck (2000) argued income-generating work is a core value and mode of integration in modern societies, a view echoing Durkheim, but on the other hand, it is at odds with some alienating forms of employment that cause individual vulnerability and opportunism (Standing 2014).

Khattab and Fenton (2009) argue that Durkheim’s ([1893] 1964) study ‘The Division of Labour in Society’ is more about social cohesion than labour. For Durkheim, the division of labour has moral functions that create social solidarity. He hypotheses two forms of solidarity: Mechanical and organic. Mechanical forms are earlier types of labour solidarity based on the similarity of this form’s members. Organic solidary stresses differences between members and typifies advanced industrial societies. The former regulates the individual in repressive ways by subjecting them to a ‘collective conscience’, whereas in organic solidarity, members become interdependent through their individual specialisms.

Employment is a (potential) source of moral and social integration, that can foster ‘industrial citizenship’ (Strangleman 2015). Industrial citizenship offers a moral bridge between the family and the state, curbing self-interest and so, reducing the risk of egoistic suicide. In his analysis of the anomie division of labour, Durkheim recognized that not all types of employment facilitated life satisfaction and societal bonding. Sennett’s (2008) studies of manual work indicate the return to older models of economic life where rewards include a boosting of personal attributes and moral purpose. In summary, employment, like marriage, has implications for how individuals integrate and thrive. In the light of this literature, we might anticipate that occupations may differ in terms of their members’ suicide risk, and that unemployment may have effects: It is to the analysis of this area that we now turn.

Regarding the variable ‘employment status’ the figures are set out in Table 1 below. Of the 5286 individuals in the cohort mentioned earlier, 4661 (88%) were of working age (16–64) and 67% were in employment at the time of their death. Over half (54%) of those whose employment status was known were classed as ‘employees, apprentices, armed forces (non-officer ranks)’.

Table 1.

Suicide by employment status (16–64-year-olds).

The high incidence of suicide (29.7%) of the no occupation group indicated in Table 1 seems to support Durkheim’s anomie theory where it highlights the protective function of societal integration through social bonds and the negative effects of limited regulation. Regarding the highest statistic stated in Table 1 (54.1%), anomie theory seems less convincing as these 2522 individuals were in employment at the time of death. Moreover, armed forces employees belong to a community which privileges team-work and role allocation within a chain of command. Apprentices are also members of a workforce to which they contribute from within a hierarchy, support is available from supervisory qualified tradesmen. The explanatory relevance of anomie theory appears unconvincing. Fatalistic suicide theory may provide a more cogent explanation of these particular suicide phenomena: As army officers suffer a comparatively limited incidence of suicide, their status and a higher degree of control and autonomy may offer protection from which rank and file soldiers are excluded.

A similar fate may accommodate the dependent apprentice class who die by suicide, possibly expressing their sense of confined agency and limited futures. Equally, the unemployed may develop pessimism about moving out of their adverse status and the exclusion and stigma, and for that reason, fatalistic suicide might reasonably describe the social causes of their decision. Ambiguity may be reduced by knowing more about the nature of an employment status since occupations have specific demands and a certain status within the class structure. Table 2 sets out the occupations of those within the same cohort.

Table 2.

Suicide by occupational group (16–64-year olds).

The “Elementary occupations” in Table 2 consist of simple and routine tasks requiring the use of hand-held tools and often some physical effort. These data indicate suicide is greater among the working classes, e.g., skilled trades (25.1%), process, plant and machine operatives (13%) and elementary occupations (16.4%). For professional occupations, it is 8.7%. However, it is even lower for the especially low paid jobs of care workers and home carers (3.4%), and low for gardeners and landscape gardeners (2%). Class itself cannot explain these illustrative differences. Men are associated with skilled trades and are often self-employed. That situation may reduce their regulation and support through social bonds, leaving them exposed to anomie. Care staff are often women and that factor, together with being intimately associated with those in greater need may, by integrating them into social structures, protect them. Members of the elementary job group (16.4%) may be poorly integrated due to reasons of status they may gain only limited recognition leaving them at risk of anomic suicide.

5. Discussion

In summary, the Scottish suicide rate data analyzed fell into three main areas: Gender, marital status, and employment/occupation. The review of previous studies in this field indicated support for Durkheim’s theorization that social structure and process impacts upon these areas in the lives of individuals who die by suicide. Through a qualitative interpretation of official statistics, an attempt was made to connect these rate data to Durkheim’s types of suicide. Whilst there were plausible associations identified with anomic and fatalistic suicides in relation to each of the three areas, it remains challenging to be certain about the validity and reliability of the choice of one or other of Durkheim’s types of suicide. In fact, it may be argued that individuals could have their deaths accounted for by combinations of his typology. Those who hold employment that is low paid or who have no employment may have undergone death by suicide for reasons connected with alienation and anomie and as they might also have envisaged a bleak future, fatalistic suicide may be apposite to these deaths. Regarding the research question, the broad analysis of each of the three areas demonstrates there are relationships between social structures and suicide deaths, as Durkheim and others since have uncovered. The risk of suicide death is elevated for those living at the base of the social hierarchy, those without the regulation and support of intimate partner ties and those who are young males.

Overlaid with the class and deprivation strands associated with the rates of suicide found in the Scottish data are gender differences. The rates of suicide for men, especially younger men, are significantly greater than for women. Durkheim theorizes that marriage is a protective factor for men as it is thought to focus their lives in a way that is not so important for married women. Bradatan (2007, p. 428) over the period 1994–1996 found, especially for men, that suicide rates for the divorced and widowed were considerably higher than for other marital statuses and concluded marriage “is still a protection against suicide” in 20th century Romania. The statistical evidence in Scotland and France shows an association of suicide with being outside of marriage. Recent empirical research in the US utilizing the interpersonal theory of suicide emphasises the role of perceived burdensomeness to family, friends and society, and failed belonging.

Failed belonging resonates with the notion of anomie where there is a sense of felt isolation and loneliness, including from other people’s experiences (Joiner 2007). US studies identified higher levels of socio-economic deprivation associated with suicide and deliberate self-injury and, moreover, in certain areas of New York, suicide is greater when there are higher levels of income inequality (Miller et al. 2005). Four hundred death certificates recorded between 1959 and 1984 from an Alaskan ethnic group formed Travis’s (1990) data, each of which was classified as suicide by state bodies. They were interpreted through a conventional Durkheimian lens: Social disintegration through the loss of land ownership, unemployment, cultural imperialism from the encroachment of white mainstream Americans and a dwindling marriage pool were salient (Travis 1990, p. 226). Utilizing Durkheim’s model Travis found that when a society integrates it “holds individuals under its control, since individuals cling to life more when they find it meaningful.” Excessive individualism creates a risk of isolation and loss of meaning through removing people from the protective wrap of tradition. It is clear from this scholarship that Durkheim’s perspective on suicide offers an analysis of the social world that brings into view the absence of group membership as a risk factor and cautions against the assumption of suicide’s aetiology as necessarily connected with a pathological individual condition.

The strengths of Durkheim’s quintessentially interpretative typology lie in its embrace of a constellation of social structural factors and awareness of change over time. His typology will have an intuitive appeal to many, given its recognition of the importance of social integration, stability and regulation through a normative framework. A critical limitation is that it appears to minimize individual nuance and contextual variables that problematize the meaning of his concepts (Stanley et al. 2016, p. 114). We do not know, for instance, if marital breakdown after twenty years is more of a risk than it is after ten years. Data reported earlier challenged Durkheim’s view that employment is a benign influence: A significant proportion of suicide deaths involved those in employment. However, as that is likely to have been low paid employment, these individuals would be more vulnerable to the damaging effects of neoliberal policies. Durkheim’s conservative moralism may have blinkered the development of his suicide theory in such a way that it struggled to embrace sufficiently other variables germane to an understanding of suicide death, such as class, age, politics and ethnicity. Despite Durkheim’s belief that his sociology embraced a factual world whose existence must be studied through the methods employed to explore the physical universe, his positivism is dense with the interpretative values of his historical culture and positionality. His empirical categories of suicide have an inescapable connection with cultural assumptions. However, it is a great strength of his approach to have harnessed masses of statistical data to test general hypotheses about the functioning of society. A limitation of the Scottish data set and others used in the literature lies in how the courts and coroners classify deaths and what factors they know about and consider. As Parkin (1992, p. 20) argues, official statistics represent social constructions “based the perceptions, intuitions, and subjective judgements of fallible human agents.” Suicide deaths are not social facts akin to facts about the physical world. In the light of this limitation around official statistics, the real or true rates of suicide might be inherently elusive with an evidence base contaminated by unknown confounding variables. Implications of the study reported in this article lie in two areas: Firstly, if categories of suicide are to be utilised, ethnographic enquires could combine with statistical analysis to contribute to the grounding of the latter’s validity and reliability. Secondly, as only a very limited proportion of those vulnerable socio-demographic groups—young men, the unemployed, divorced people and unmarried men—experience death by suicide, we need to know why the majority of those living under broadly similar environmental conditions of adversity seem to experience no apparent anomie or, if they do, it nevertheless has no fatal effect on them. Regulation and integration processes are more deeply complex and nuanced than Durkheim theorised, and for their investigation, require a range of methodologies that address the limitations of his empirically informed theorising.

Author Contributions

C.H., conception of paper, and writing, R.M. ideas, analysis and editing.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abrutyn, Seth, and Anna S. Mueller. 2014. The Socioemotional Foundations of Suicide: A Micro sociological View of Durkheim’s Suicide. Sociological Theory 32: 327–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, Ulrich. 2000. The Brave New World of Work. Translated by Patrick Camiller. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bergen, Diana Van, Johannes H. Smit, Anton van Balkom, and Saharso Sawitri. 2009. Suicidal behavior of young immigrant women in the Netherlands. Can we use Durkheim’s concept of ‘fatalistic suicide’ to explain their high incidence of attempted suicide? Ethnic and Racial Studies 32: 302–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradatan, Christina. 2007. About Some 19th-Century Theories of Suicide. International Journal of Comparative Sociology 48: 417–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronisch, Thomas. 2015. Suicide. In International Encyclopedia of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 23, pp. 673–81. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran, Paul, and Aaron Nagar. 2010. Suicide and marital status in Northern Ireland. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 45: 795–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, Catherine. 2017. Edufare for the future precariat: The moral agenda in Australia’s ‘earning or learning’ policy. Journal of Education Policy 32: 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, Emile. 1964. The Division of Labour in Society. New York: Free Press. First published 1893. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim, Emile. 2006. On Suicide. Translated by R. Buss. London: Penguin Books. First published 1897. [Google Scholar]

- Glendinning, Richard, Buchanan Tim, and Nickie Rose. 2002. Well? What Do You Think? A National Scottish Survey of Public Attitudes to Mental Health, Well Being and Mental Health Problems; Edinburgh: Scottish Government. Available online: http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2002/12/15967/15270 (accessed on 20 March 2018).

- Gorman, Dermot, Rachel King, Magda Czarnecka, Wojtek Wojcik, and Phil Mackie. 2018. A Review of Suicides of Polish People Living in Scotland. Glasgow: ScotPHN. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, Stuart. 2011. The Neoliberal Revolution. Soundings: A Journal of Politics and Culture 48: 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joiner, Thomas. 2007. Why People Die by Suicide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khattab, Nabile, and Steve Fenton. 2009. What Makes Young Adults Happy? Employment and Non-work as Determinants of Life Satisfaction. Sociology 33: 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyung-Sook, Woo, Shin Sang-Soo, and Shin Sangjin. 2018. Marital status integration and suicide: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Social Science and Medicine 197: 116–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lester, David. 1991. Totalitarianism and fatalistic suicide. Journal of Social Psychology 131: 129–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Kate, and Alistair Leyland. 2005. Urban/rural inequalities in suicide in Scotland, 1981–1999. Social Science and Medicine 60: 2877–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millard, Alan, McCartney Graham, MacKinnon Alistair, Van Heelsum Alan, Gasiorowski Anthony, and Barkat Susan. 2016. Inverclyde Health and Wellbeing Profiles—Key Indicators and Overview. Edinburgh: ISD Scotland. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Jeffrey, Tinka Markham Piper, Jennifer Ahern, Melissa Tracy, Kenneth J. Tardiff, David Vlahov, and Sandro Galea. 2005. Income Inequality and Risk of Suicide in New York City Neighborhoods: A Multilevel Case-Control Study. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 35: 448–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, Pearl, Navneet Kapur, Kirsteen Windfuhr, Alastair H. Leyland, Louis Appleby, Stephen Platt, and Roger T. Webb. 2012. Trends in national suicide rates for Scotland and for England and Wales, 1960–2008. British Journal of Psychiatry 200: 245–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Matthew. 2016. Durkheim’s types of suicide and social capital: A cross-national comparison of 53 countries. International Social Science Journal 66: 151–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS National Services Scotland. 2016. A Profile of Deaths by Suicide in Scotland 2009–2014. A Report from the Scottish Suicide Information Database (ScotSID). Edinburgh. Available online: http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Public-Health/Publications/2016-08-10/2016-08-10-ScotSID-Report.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2018).

- NHS National Services Scotland. 2018. A Profile of Deaths by Suicide in Scotland 2011–2017. A Report from the Scottish Suicide Information Database (ScotSID). Edinburgh. Available online: https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Public-Health/Publications/2018-12-04/2018-12-04-ScotSID-Report.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2019).

- Parkin, Frank. 1992. Durkheim. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson, Jane, Jon Minton, James Lewsey, Janet Bouttell, and Gerry McCartney. 2017. Recent cohort effects in suicide in Scotland: A legacy of the 1980s? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 71: 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platt, Stephen, Paul Boyle, Iain Crombie, Zhiqiang Feng, and Dan Exeter. 2007. The Epidemiology of Suicide in Scotland, 1989–2004. Edinburgh: Scottish Government. [Google Scholar]

- Poggi, Gianfranco. 2000. Durkheim. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rural Poverty and Exclusion Working Group. 2001. Poverty and Social Exclusion in Rural Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, John. 2014. A Dictionary of Sociology. Oxford: Oxford Reference Online. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Government. 2011. Drugs and Alcohol—Prevalence of Problem Drug Users. Available online: http://www.gov.scot/Topics/Statistics/Browse/Crime-Justice/TrendPrev (accessed on 22 March 2018).

- Scottish Government. 2017a. Domestic Abuse Recorded by the Police in Scotland, 2016–2017. Available online: http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2017/10/3700 (accessed on 22 March 2018).

- Scottish Government. 2017b. Drug Seizures and Offender Characteristics, 2014–2015 and 2015–2016. Available online: http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2017 (accessed on 22 March 2018).

- Jonathan, Scourfield, Fincham Ben, Langer Susanne, and Shiner Michael. 2012. Sociological autopsy: An integrated approach to the study of suicide in men. Social Science and Medicine 74: 466–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sennett, Ricard. 2008. The Craftsman. London: Allen Lane. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, Martin, Danny Dorling, and G. Davey Smith. 2002. Mortality and political climate: How suicide rates have risen during periods of Conservative government, 1901–2000. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 56: 723–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, Steven. 1979. Durkheim’s theory of fatalistic suicide: A cross-national approach. The Journal of Social Psychology 107: 161–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, Steven. 2000. Suicide: A 15-year review of the sociological literature: Part II: Modernization and social integration perspectives. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behaviour 30: 163–76. [Google Scholar]

- Seven, Stack, and Wassermen Ira. 2007. Economic strain and suicide risk: A qualitative analysis. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behaviour 37: 103–12. [Google Scholar]

- Standing, Guy. 2014. A Precariat Charter. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Ian, Stanley, Hom Melanie, Rogers Megan, Hagan Christopher, and Joiner Thomas. 2016. Understanding suicide among older adults: A review of psychological and sociological theories of suicide. Aging & Mental Health 20: 113–22. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, Cameron, Diane Stockton, and Rob Henderson. 2008. Reduction in young male suicide in Scotland. BMC Public Health 8: 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steger, Manfred, and Ravi Roy. 2013. Neoliberalism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strangleman, Tim. 2015. Rethinking industrial citizenship: The role and meaning of work in an age of austerity. British Journal of Sociology 66: 673–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasi, Luigi. 2000. Emile Durkheim’s contribution to the sociological explanation of suicide. In Durkheim’s Suicide: A Century of Research and Debate. Edited by W. S. F. Pickering and Geoffrey Walford. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Travis, Robert. 1990. Halbwachs and Durkheim: A test of two theories of suicide. The British Journal of Sociology 41: 225–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wray, Matt, Cynthia Colen, and Bernice Pescosolido. 2011. The Sociology of Suicide. Annual Review of Sociology 37: 505–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Jie. 2010. Marriage and Suicide among Chinese Rural Young Women. Social Forces 89: 311–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | All page references in text except those tied with other citations are to Durkheim ([1897] 2006). ‘On Suicide’. trans. R. Buss. London: Penguin Books. |

| 2 | National Services Scotland: Suicide Statistics (2018). |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).