2. The Obedience Studies Reinterpreted

Milgram, who was Jewish, was both intrigued and horrified by the Holocaust. He wondered what would happen if, as ordinary Germans did during World War Two, average Americans were ordered to hurt others. He invented a rudimentary psychology experiment where participants were instructed to inflict punishment in the form of electric “shocks” on an actor pretending to be an incompetent learner. To determine the research idea’s potential, Milgram tasked his students with running a pilot study (see

Russell 2018, pp. 61–64). During this first pilot, many participants across a few conditions inflicted every shock asked of them. It was then that Milgram likely sensed enormous potential in his research idea and thereafter decided to run an official research programme that had two main goals. First, because nobody would be surprised by an experiment that obtained a low rate of obedience to hurt an innocent person, Milgram knew his first official baseline experiment had to create what he termed “the strongest obedience situation”—it

had to “maximize obedience” (quoted in

Russell 2011, pp. 149, 158). Second, to unravel why most participants in the first baseline inflicted every shock, as mentioned, he planned to undertake a variety of slight baseline variations. Through a gradual process of elimination, Milgram hoped these variations would lead him towards a theory capable of explaining why most participants completed the baseline.

To achieve his goals, Milgram needed help in the form of financial backing, professional laboratory facilities, technical equipment, and numerous technicians, research assistants, and actors. Converting the student-run pilots into an official research programme was a massive logistical undertaking. To achieve his goals, Milgram had to design a meticulous and well-coordinated participant-processing and data-collecting organisational process where, across many months, all helpers sequentially performed their specialist roles.

Because during the student-run pilots many participants, according to Milgram, experienced “extreme tension” when inflicting the “painful” shocks (quoted in

Russell 2018, p. 157), one hurdle threating goal achievement was that both he and his many helpers might conclude the stress-inducing experiments were unethical, and thus decide to not fulfil their essential roles. To ensure that every functionary, including Milgram himself, agreed to perform their specialist roles, Milgram relied on two main psychological techniques. First, he utilised an array of Strain Resolving Mechanisms (SRMs), which are techniques that people employ to reduce tensions they might otherwise feel in relation to their harmful actions (

Milgram 1974, pp. 153–64). For example, because Milgram believed his research held the potential to better understand the Holocaust, he became convinced that despite participants being stressed, undertaking the research was for the greater good and thus necessary (see

Russell 2014a, p. 414). Milgram then encouraged his funders at the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the chairman of Yale University’s Department of Psychology Claude Buxton—together with Alan Elms (research assistant) and several actors (particularly the “experimenter,” John Williams and the “learner,” James McDonough)—“to view” the experimental programme “as an analogue of Nazi evil” (

Fermaglich 2006, p. 89). This conversion of “something evil” (inflicting stress on innocent people) into something “good” (scientific knowledge) is a SRM termed “moral inversion” (

Adams and Balfour 1998, p. XX). Thus, the research programme’s higher scientific goals invested the experiments with an ideologically-driven organisational sense of mission: data collection was, according to Williams, of “tremendous value” and therefore “must be done” (quoted in

Russell 2018, p. 162). The NSF, however, expressed concerns that some participants might experience “negative effects” (

Blass 2004, p. 71) and, related to this, Buxton thought the experiments could generate a public relations problem for Yale (see

Russell 2018, p. 158). Milgram likely eased these concerns by stating in his official research proposal that measures would be introduced to “insure the subject’s well being [

sic]” (quoted in

Russell 2018, p. 158) (SRM).

The second psychological technique Milgram relied on to better ensure all his helpers did as he desired was what he termed “binding factors” (BF). BFs are external bonds that can tempt, coerce, or entrap a person into doing something they would prefer not to do (

Milgram 1974, p. 148). One powerful BF was Milgram’s attempts to efficaciously appeal to his helpers’ sometimes different self-interested personal or organisational needs, wants, and desires. For example, regarding himself, although Milgram suspected that completing the Obedience Studies offered the possibility of better understanding the Holocaust, he also knew that, in terms of job security, fame, and fortune, he would likely benefit from goal achievement (BF). For example, when inventing the basic experimental procedure, the then untenured Milgram told Jerome Bruner at Harvard, “My hope is that the obedience experiments will take their place along with the [world-famous] studies of Sherif, Lewin and Asch” (quoted in

Perry 2012, p. 57). Milgram also appealed to the NSF’s central organisational objective to sponsor innovative research, when claiming in his proposal that the research was “a relatively unexplored domain of social behavior” in which the first “Pilot studies … yielded unexpected”—even “startling”—“results” (quoted in

Russell 2018, p. 159) (BF). Statements such as this also appealed to Yale University’s central organisational mission—the acquisition of knowledge—thereby securing their institutional support (

Russell 2014a, p. 414). Research assistant Alan

Elms (

2009, p. 32) outlined an array of BFs influencing his involvement: Yale’s psychology graduate programme required he secure a “faculty sponsor,” Milgram payed him for services rendered, and there was the draw of his (Elms’) own intellectual curiosity. In terms of the acting staff, Milgram sensed that moral inversion was, on its own, unlikely to secure their long-term commitment. Milgram therefore offered them a generous hourly rate that he increased three times across their eight months of employment (

Russell 2014a, p. 416) (BF). If any staff refused to fulfil their roles—as one actor did (see

Perry 2012, p. 226)—Milgram simply hired someone else who would.

Thus, Milgram’s strategy to ensuring all helpers performed their specialist roles involved him both easing their individual fears and also appealing to their varied self-interested needs and desires. Whether they were an individual or institution, Milgram applied what he anticipated to be the most likely successful individually tailored motivational formula—quid pro quo arrangements where benefits are provided in exchange for services rendered. In the end, Milgram and his helpers, armed with similar rationalisations, collectively resolved the moral dilemma over whether to participate in a potentially harmful study. They all did so by being convinced and/or opportunistically tempted into making their essential specialist contributions to the Obedience Study’s participant-processing data-collecting organisational process (

Russell 2018, pp. 155–98).

One might suspect that Milgram and his helpers would have felt anxious over the possibly of harming innocent people, especially after weighing this cost up against their mere “scientific,” personal, or organisational benefits. This is especially so considering that both during and soon after the official data collection process, at least two stressed participants informed Milgram they thought they were going to have—or perhaps had—a heart attack (see

Russell 2018, p. 117). However, alleviating such concerns was that as Milgram drew all his helpers into fulfilling their specialist roles, the issue of individual responsibility for harm-infliction underwent a subtle yet powerful transformation. That is, when Milgram and all his helpers agreed to perform their specialist roles, they unwittingly became links in a goal-directed assembly line-like bureaucratic process.

To clarify, intrinsic to bureaucracy is the division of labour, which is where an organisational goal is subdivided into numerous tasks. These numerous tasks are then performed by a variety of specialist functionary helpers (

Ritzer 1996, p. 18; see also

Bauman 1989). For functionaries, however, this compartmentalisation can promote a disjuncture between cause (e.g., making partial contributions to the achievement of Milgram’s goals) and any negative effects generated by goal achievement (e.g., the infliction of intense stress on participants). This disjuncture between cause and effect among functionaries can stimulate what Russell and Gregory term “responsibility ambiguity” (

Russell and Gregory 2015, p. 136). Responsibility ambiguity is a metaphorical haziness, which renders debatable who exactly is aware of and responsible for any harm inflicted by the organisational process. Responsibility ambiguity also makes it difficult for arbiters to later determine who should be held to account for such harmful outcomes.

This metaphorical haziness produces two main types of functionaries. The first type of functionary is genuinely unaware of their personal responsibility in contributing to a harmful outcome because they remain structurally oblivious of the eventually destructive consequences (like, for example, the engineer who constructed the shock machine and whom, in all likelihood, remained unaware of what Milgram planned to do with it). The second type of functionary, however, is aware that harm may be inflicted but opportunistically decides to make their partial contributions to the wider process because of a suspicion they will be rewarded in the short term and never punished in the long term. That is, hidden within the fog of responsibility, the second type of functionary chooses to contribute to harm infliction because they sense that should anyone later question them about their unethical decision to proceed, they can always claim to be the first type of functionary—they (apparently) did not know about harm-infliction or they (apparently) did not believe any harm was inflicted (SRM). Below we will argue that Milgram and the NSF were examples of second-type functionaries.

In addition, because so many other functionaries are involved in contributing to the wider process, second-type functionaries can also—if they so choose—draw on other powerful sources of responsibility ambiguity like, for example, relying on the diffusion or displacement of responsibility. To clarify, the diffusion of responsibility is where all functionaries across the organisational process make partial contributions to a harmful outcome and, as a result, second-type functionaries feel only fractionally responsible for the harm inflicted. Because no single contributor feels most responsible for the harm inflicted, ultimate responsibility gets “diluted” across all contributors. With everyone just a tiny bit responsible, the diffusion of responsibility reduces the psychological strain felt by any one second type of functionary (SRM).

The displacement of responsibility is where second-type functionaries choose to “pass the buck” of responsibility for their contributions elsewhere (SRM) (

Russell and Gregory 2015, p. 136). This passing of the buck is possible because so many other functionaries are involved in contributing to goal achievement. For example, had a participant been seriously injured, Williams—the inflictor of that stress—could blame Milgram: the experimenter was only following his boss’s instructions. However, Milgram, the principle investigator, was only undertaking the kind of ground-breaking research that Yale University pressured non-tenured faculty into pursuing—he too was only doing his job. Perhaps the NSF committee or Chairman Buxton (Milgram’s boss) was most responsible—they were the highest-ranking functionaries that allowed the research to proceed. The NSF committee and Buxton, however, never directly hurt anybody. Furthermore, these high-ranking figures could add that Milgram never informed them of his intentions to run particularly unethical variations (for example, Milgram independently deciding to run the

Relationship condition, which was never mentioned in any of his research proposals). As with many leaders of destructive organisations, to some degree they (apparently) never knew what their underlings were up to. Perhaps in the end the most blameworthy entity was (rather conveniently) the reified ideological pursuit of “scientific knowledge” (SRM).

5 The point is, for opportunistic functionaries working across a malevolent bureaucracy, there is a sense that should anyone later question their decisions to contribute, they can claim plausible deniability—they did not know or believe harm was being inflicted. If indisputable evidence undermines the truthfulness of such denials, because of the difficultly in identifying any one person as ultimately responsible, all can claim to be a tiny bit responsible or simply blame someone (or something else) as more responsible for their eventually harmful contributions. Ultimately, because “others” were involved, many Obedience-Study functionaries likely sensed that they could probably continue making (and benefiting from) their individual contributions to the wider organisational process and, even if a participant was seriously harmed, they could do so with probable impunity. Feeling they were “covered” likely explains why Milgram and his helpers risked partaking in such dangerous research (see

Russell 2018, pp. 166, 173, 175).

A second factor that likely enhanced feelings of responsibility ambiguity and thus encouraged all helpers to make their harmful contributions was that none had to directly (physically) inflict “harm.” This included the coercive experimenter who delivered participant stress by way of mere words.

A third factor that likely enhanced feelings of responsibility ambiguity and helped push and pull all helpers into role fulfilment is termed bureaucratic momentum (

Russell 2018, p. 179). Bureaucratic momentum takes hold when functionaries experience real or imagined pressure to perform their specialist roles by preceding and sometimes succeeding functionary links in the organisational chain. This coercive force appears to be generated by the cumulative momentum of the many simultaneously moving functionary cogs bearing down and exerting pressure on every singular cog—experienced in the form of group pressure whereby “to get along” individuals feel the push to “go along” (BF). For example, workers on an assembly line often feel pressured into quickly fulfilling their specialist roles so co-workers can perform their roles. The pressure of bureaucratic momentum to, for example, contribute to harm-infliction is difficult to resist because a potentially uncooperative functionary must: (1) sacrifice whatever self-interested benefits were on offer in exchange for role performance; and (2) be willing to deprive other (potentially belligerent) functionaries from obtaining whatever benefits they anticipated receiving for contributing to goal achievement. It is easier if all functionaries just do their bit for organisational goal achievement. Bureaucratic momentum can enhance feelings of responsibility ambiguity (thus reduce strain) across each link in the division of labour because if individuals feel pressured by other functionaries (or even structures as, for example, the set speed of an assembly-line process) into fulfilling their roles, then these individuals can be tempted into blaming those others (and other structures) as most responsible for their actions (SRM).

During the Obedience Studies, it is likely that Milgram and all his helpers felt the push and pull of bureaucratic momentum. For example, to please his generous NSF funders, Milgram felt pressure to collect a full set of data. Collecting a full dataset, however, required the long-term retention of the experimenter’s acting services. In return for longer-term employment, Williams likely felt contractually obliged to continue placing participants under enormous stress (see

Russell 2018, pp. 179–259).

Finally, the foot-in-the-door phenomenon also likely helped reduce Milgram and his helpers’ feelings of anxiety over their contributions to a potentially harmful study (SRM/BF). The foot-in-the-door phenomenon is where persons are more likely to agree to a significant request if it is preceded by a comparatively insignificant request (

Freedman and Fraser 1966). For example, it could be argued that, after Milgram and his research team agreed to undertake the first official and relatively benign

Remote-Feedback baseline condition (learner banged wall), they became more amenable or desensitised to undertaking the fifth and far more radical

New Baseline (learner with heart condition screams in agony). With the entire research team having agreed to undertake the more radical

New Baseline, they were more amenable to helping run the final

Relationship condition (participant pushed into inflicting agonising “shocks” on someone they knew). The point being, the slippery slope of the foot-in-the-door phenomenon—small and barely perceivable steps in an increasingly radicalised direction—likely had both a strain-resolving and binding influence on all those working within the Obedience Study organisational chain.

In summary, it can be argued that a morally inverted and ideologically essential “scientific” rationale for inflicting harm (SRM), personal/organisational benefits (BF), the option of plausible deniability or the diffusion/displacement of responsibility (SRM), an indirect means of harm-infliction (SRM), bureaucratic momentum (SRM/BF), and the foot-in-the-door phenomenon (SRM/BF) all likely contributed to Milgram and his helpers’ decision to collect a full set of ethically questionable data.

Why, then, did most participants complete the

New Baseline? Before it is possible to address this question, it is important to note that participants were the last functionary link in Milgram’s wider data-collecting organisational chain. Because of this last-link position,

Russell and Gregory (

2015) argued that participants were therefore susceptible to the same kinds of pushes (BFs) and pulls (SRMs) that affected all the other functionary links further up the bureaucratic chain.

For example, when the participant entered the laboratory the experimenter attempted to convince them that shocking an innocent person was of great scientific importance because doing so would help unravel the effects of punishment on learning (

Milgram 1974, p. 18). Although this was a slightly different strain-resolving rationale to that which Milgram provided to his helpers, it was similar in that the ideological pursuit of scientific discovery was deployed whereby something evil (harming an innocent person) was morally inverted into something good (serving science) (

Milgram 1974, p. 187) (SRM).

At the start of the experiment, nearly every participant inflicted the first six relatively light shocks (15–90 volts). However, doing so saw them fulfil the most important criterion of the foot-in-the-door phenomenon (SRM/BF): compliance with one or several small requests which, unbeknownst to them, were to be followed by some far greater ones. For participants—somewhat as it did for Milgram and his helpers—the foot-in-the-door phenomenon likely had two important consequences:

(a) it engages subjects in committing precedent-setting acts of obedience before they realize the ‘momentum’ which the situation is capable of creating, and the ‘ugly direction’ in which that momentum is driving them; and (b) it erects and reinforces the impression that quitting at any particular level of shock is unjustified (since consecutive shock levels differ only slightly and quantitatively).

Across many small 15-volt steps, most participants ended up inflicting intensifying “shocks.”

If the foot-in-the-door technique failed and a participant hesitated to inflict further shocks, the experimenter unleashed his barrage of binding prods: “It is absolutely essential that you continue,” and such. This pressure to inflict further shocks was arguably an extension of the bureaucratic momentum working its way down the organisational chain—goal achievement required all helpers fulfil their specialist roles (SRM/BF).

One particularly powerful SRM that made it psychologically much easier for participants to fulfil their specialist role was the research programme’s specific means of inflicting harm. Because the shock machine directly inflicted the “painful” blows, much like all the other functionary links further up the organisational chain, participants were also, technically speaking,

indirect inflictors of harm—they “only” flicked switches (

Russell and Gregory 2015, pp. 143–46). Thus, and it is no coincidence, every human link across Milgram’s organisational chain avoided the stressful act of

direct harm-infliction—an outcome that, among every helper, greatly advanced feelings of responsibility ambiguity.

Having said this, as the learner’s pained reactions to the higher voltage “shocks” intensified, for participants the close relationship between cause (flicking switches) and effect (screaming learner) saw most of them react with nervous facial expressions. This nervousness suggests most participants started to

feel more responsible for their actions. Most wanted to stop inflicting the shocks but something inhibited them from acting on this desire. It transpires this inhibition likely traced back to a fear that in order to stop the experiment they would have to engage in a socially awkward and forceful confrontation with the experimenter (

Miller et al. 1995, p. 9;

Russell and Gregory 2011, pp. 499–500). To avoid this clash, many participants attempted to invent their own non-confrontational means of prematurely stopping the experiment. The most important of the many such examples of this kind of behaviour occurred after participants reached the final third of the shock switches (see

Russell and Gregory 2011, pp. 504–11), whereby some participants concluded it might be wise to have the experimenter explicitly establish the direct lines of responsibility. In the unlikely case that the experimenter would accept full responsibility for the participant inflicting perhaps life-threatening shocks on the learner, it seems these participants anticipated that they would then have been armed with an inoffensive opportunity to politely pull out of the experiment. That is, the experimenter could not reasonably expect the participant to shoulder full responsibility for what is quite clearly

their harmful experiment (

Meeus and Raaijmakers 1995, pp. 164–65). However, when participants attempted to clarify the lines of responsibility, to their surprise the experimenter stated, “I’m responsible for anything that happens to him. Continue, please” (

Milgram 1974, p. 74). The participants’ search for non-confrontational exit strategies such as this not only failed but typically backfired because, while trying to think of such improvised excuses for stopping, they only got lured into inflicting even more morally dubious shocks (

Russell and Gregory 2015, p. 141). Even if they gathered enough courage to forcefully stop the experiment, they would have been faced with the additional burden of explaining why they inflicted so many shocks after the learner earlier complained about his heart condition at the 150-volt switch (

Milgram 1974, p. 149). “The … problem then,”

Milgram (

1965, p. 73) explained, “is how to become disengaged from a situation which is moving in an altogether ugly direction.” Many participants likely felt locked into participation.

As participants contemplated the ugly direction they were headed, a tempting opportunity emerged: if they unquestionably did as the experimenter asked, then participants could blame the experimenter for their shock-inflicting actions (

Eckman 1977, p. 97). That is, the prods likely tempted many participants to suspect that, despite

feeling they were engaged in wrongdoing, because the experimenter was explicitly demanding they continue, the participants may not have

appeared to others present as the person most responsible for the learner’s pain. Thus, confrontation-adverse participants were encouraged to suspect they could displace responsibility for their actions on to the experimenter because the latter said, and the former wanted to believe, it was “essential” to continue, that they had “no choice” but to do so, and that only the experimenter was “responsible.” It is likely that this last prod proved extremely tempting for many participants because appearing to believe that only the experimenter was responsible not only enabled them to avoid a confrontation, it also absolved them from moral and legal culpability for continuing (see

Russell 2018, pp. 199–230). When participants capitalised on the responsibility ambiguity inherent within this situation by “passing the buck,” this helped reassure many of them that—similar to all the other second type functionaries involved—they could probably personally benefit from their individual contributions to the system. Most importantly, they could probably also do so with impunity. Effectively, the prods planted a dark seed in the participants’ mind: they gifted them with a credible and tempting excuse for their decision to continue engaging in wrongdoing (

Russell and Gregory 2015, p. 142).

Therefore, participants could either: (1) critically rebuke the experimenter and refuse to inflict further shocks; or (2) accept the experimenter’s assurances that they could continue shocking the learner and not only avoid a confrontation (benefit), but do so with probable impunity. When participants contemplated the latter option, the psychological noose inherent in the experimental procedure tightened. Faced by this dilemma, some participants refused to continue, but most chose what for them was the easier self-interestedly “beneficial” option: inflict more shocks.

It is difficult for observers to comprehend how most participants could turn their backs on the learner, and do so for such a trivial reason. However, because observers are outside this situation, they are typically oblivious of the basic procedure’s many subtle manipulative forces. For example, observers are often insensitive to the reality that: (1) all the symbols of power—the “Yale”-sponsored experimenter, “Dr” Milgram and his prestigious “Ivy League” institution—bolstered the perception that harming an innocent person was normative “model” behaviour; (2) because “obedient” participants are encouraged to feel they are free to pursue wrongdoing, they are led to suspect that only they will ever know about their immoral decision to prioritise their lesser important desires over the learner’s clearly more important needs; (3) there were many small steps that gradually and imperceptibly lured participants well beyond what felt like a point of no return; and (4) the wider organisational process was structured in a way whereby—similar with every other functionary helper involved—unethical choices always felt easy and ethical ones personally burdensome.

Thus, the Obedience Studies are not about “obedience” per se (see

Russell 2018, pp. 133–36). The participants’ common post-experimental justification that they were “just following orders” was more likely a convenient excuse that enabled them to both pursue their self-interested desires whilst evading responsibility for their decision to “harm” the learner. In our view, the experiments are about how every functionary link across a harmful ideologically-driven goal-directed organisation was collectively persuaded, tempted or pushed into resolving a moral dilemma that was likely to end in the achievement of Milgram’s over-arching and potentially harmful goal to maximise “obedience” (completions). They illustrate how a powerful figure such as Milgram used bureaucracy as an institutional tool of goal achievement to push and pull all of his helpers into, as

Bandura (

1999, p. 194) might put it, morally disengaging self-sanctions. Indeed, this experimental programme saw nearly all of those involved pursue self-serving desires that could have harmed the participants or, had the experiments been real, would have harmed the powerless learner. Ultimately, the “Obedience” studies are about how the powerful are able to deploy organisational processes to achieve their harmful goals at the expense of the powerless. They are, as Edward E. Jones put it, a “triumph of social engineering” (quoted in

Parker 2000, p. 112); a veritable “demonstration of power itself” (

Stam et al. 1998, p. 173). Because the “Obedience” experiments are actually about a powerful figure’s utilisation of bureaucratic organisation to socially engineer his harmful desires into a reality, at their root the Obedience Studies are also about the abuse of that power (

Russell 2018, pp. 74, 90, 260–61).

That Milgram abused his power became clearer after the publication of the first baseline experiment in 1963. In it he alluded to the possibility that he had captured elements of the Holocaust in the laboratory setting, revealing results he expected would impress the scholarly community. However, the first scholarly response to Milgram’s publication was

Baumrind’s (

1964) scathing ethical critique—Milgram, she claimed, had used and abused his innocent participants perhaps, she implies, to benefit his academic career. Baumrind bolstered her point about participant abuse by citing a quote from Milgram’s article:

I observed a mature and initially poised businessman enter the laboratory smiling and confident. Within 20 min he was reduced to a twitching, stuttering wreck, who was rapidly approaching a point of nervous collapse.

Baumrind’s critique threatened to label Milgram’s research programme unethical and thus had the potential to destroy his academic career. With his self-interests suddenly on the line, Milgram thereafter pursued a misleading public relations campaign where he told lies, massaged the truth, and chose not to reveal his most controversial results. For example,

Milgram (

1964, p. 848) counter-critiqued Baumrind for confusing “the unanticipated outcome of an experiment with its basic procedure”, then elaborating that “The extreme tension induced in some subjects was unexpected.” Milgram said this despite him having run pilot studies where, as mentioned, some participants experienced “extreme tension …” (quoted in

Russell 2018, p. 157). Milgram added that after each experimental trial all participants were informed that the learner never received any shocks (

Milgram 1964, p. 849). Gina Perry, however, later discovered that in fact most participants were never dehoaxed (

Perry 2012, p. 92). In his response to Baumrind, Milgram even described participant stress as “momentary excitement” (

Milgram 1964, p. 849), a sudden change in tone from his 1963 article that

Patten (

1977, p. 356) describes as “a most astonishing about-face …” Despite those participants who complained to him about their hearts, Milgram continued to use this phrase; later arguing in one interview that he genuinely thought no “permanent damage results” (quoted in

Meyer 1970, p. 132). In his 1974 book, Milgram let slip that before the start of each trial participants signed “a general release form, which stated: ‘In participating in this experimental research of my own free will, I release Yale University and its employees from any legal claims arising from my participation’” (1974, p. 64). Not mentioned, however, was an admission in his personal archive that, “The release, of course, was not used for experimental purposes, but to protect us against legal claims” (quoted in

Russell 2018, p. 172). If Milgram genuinely believed the experiments were harmless, why did he need legal protection? Milgram clearly maintained two contradictory perspectives: one of

public denial of harm infliction and one involving privately pursued actions that aimed to protect his personal interests if and when participants were harmed. The arguably ambitious Milgram, who was later recruited by Harvard University for a tenure track professorship (

Blass 2004, p. 131), was a second-type functionary.

Another omission was that, although pre-Baumrind (1964) Milgram promised to publish the

Relationship condition, after the publication of her critique, he never again mentioned the variation’s existence (

Russell 2014b). Had Baumrind caught wind of this condition—where, for example, a father was pushed into inflicting shocks on his yelping son—one can only imagine the ethical firestorm she would have unleashed on him. In his book’s draft notes Milgram justified his (mis)treatment of participants by arguing that the research’s enormous benefits—greater knowledge—outweighed the costs:

Under what conditions does one ask about destructive obedience? Perhaps under the same conditions that a medical researcher asks about cancer or polio; because it is a threat to human welfare and has shown itself a scourage [sic] to humanity.

Of course, if the purist acquisition of knowledge was his greatest priority, why did he fail to publish the Relationship condition—an experiment that might aid in his (apparently) all-important pursuit for greater knowledge? In Milgram’s private notes, he admitted to some regrets:

… considered as a personal motive of the author—the possible benefits that might redound to humanity—withered to insignificance alonisde [sic] the strident demands of intellectual curiosity. When an investigator keeps his eyes open throughout a [scientific] study, he learns things about himself as well as about his subjects, and the observations do not always flatter.

However, to his NSF funders, Milgram labelled his “obedient” participants “moral imbeciles …” (quoted in

Blass 2004, p. 100), and thereafter spent years trying to understand why

they engaged in wrongdoing. The next section explores what this organisational interpretation of the Obedience Studies can offer to better understanding humankind’s present inability to avert climate catastrophe.

3. The Obedience Studies and Climate Catastrophe

If our leaders seek to conceal the truth, or we as people become accepting of alternative realities that are no longer grounded in facts, then we as American citizens are on a pathway to relinquishing our freedom.

—Rex Tillerson, May 2018.

6

One fruitful way of shedding light on the present inability to avert climate catastrophe requires the reader view a central cause of accumulating GHG emissions—the production and consumption of fossil fuels—as an Obedience study-like ideologically-driven, unethically goal-directed, and inherently harmful organisational process. This organisation, it could be argued, is utilised by the powerful to best ensure every link across the chain is sufficiently pushed and pulled into fulfilling their specialist roles within the wider process. When applying this organisational lens to climate catastrophe, it is firstly important to establish, similar to during the invention of the Obedience Studies, the fossil fuel industry’s organisational goal. Consider, for example, our main case study: Exxon and, after the 1999 merger, ExxonMobil—one of the world’s largest oil companies. Bolstered by the ideology of capitalism and the continuous drive for economic growth, the main goal of such companies, as expressed in ExxonMobil’s mission statement, is to maximise profit by selling as much oil as possible for the highest price:

We are committed to enhancing the long-term value of the investment dollars entrusted to us by our shareholders.

7

Therefore, executive management must first envision then (somewhat similar to Milgram) construct an organisational process that will effectuate goal achievement. Achieving the goal of profit maximisation naturally requires an enormous amount of help: specialist investors, geologists, engineers, constructors, transporters, marketers, wholesalers, retailers, and, finally, consumers. After management inserts all the functionary links into their specific place across the division of labour, goal achievement then necessitates they all sequentially and sometimes repeatedly (e.g., consumers) perform their specialist roles.

How have oil corporations including ExxonMobil encouraged all their helpers to partake in role performance? As with Milgram, management tries to anticipate then apply, for each specialist link, the most likely successful quid pro quo motivational formula. In exchange for services rendered, management offers its prospective helpers competitive salaries, attractive pension plans, health and dental benefits, stock options, prestigious job titles, and, for consumers, a highly desirable product (BF).

8 Again, all links must (and do) personally benefit from role fulfilment. As Milgram found, appealing to helpers’ self-interests has long proven to be an effective organisational recruitment and retention strategy.

For more than a hundred years, the oil industry has invested massive sums of money into developing an increasingly efficient worldwide oil-delivery infrastructure that, in terms of standard of living, has delivered benefits to much of humankind. Then in 1988 a major threat to goal achievement arose: NASA’s leading climate scientist James Hansen warned the U.S. Senate that rising global temperatures are “… now large enough that we can ascribe with a high degree of confidence …”—99% in fact—“a cause and effect relationship to the greenhouse effect.”

9 The New York Times increased public awareness about Hansen’s warning with an article titled “Global Warming Has Begun, Expert Tells Senate” (

Banerjee et al. 2015, Part 1). With the help of the first IPCC assessment report in 1990 and their subsequent and increasingly grave warnings, international public awareness of climate catastrophe only grew. Despite this greater awareness, rising emissions illustrates that functionaries across the fossil fuel industry infrastructure, including investors and consumers, have continued fulfilling their specialist roles. To help explain this destructive behaviour, we argue that climate catastrophe has all except one of the key factors that encouraged Milgram, nearly all of his helpers, and most of his baseline participants, to fulfil their specialist roles in the Obedience research’s personally beneficial yet ultimately harmful wider organisational process.

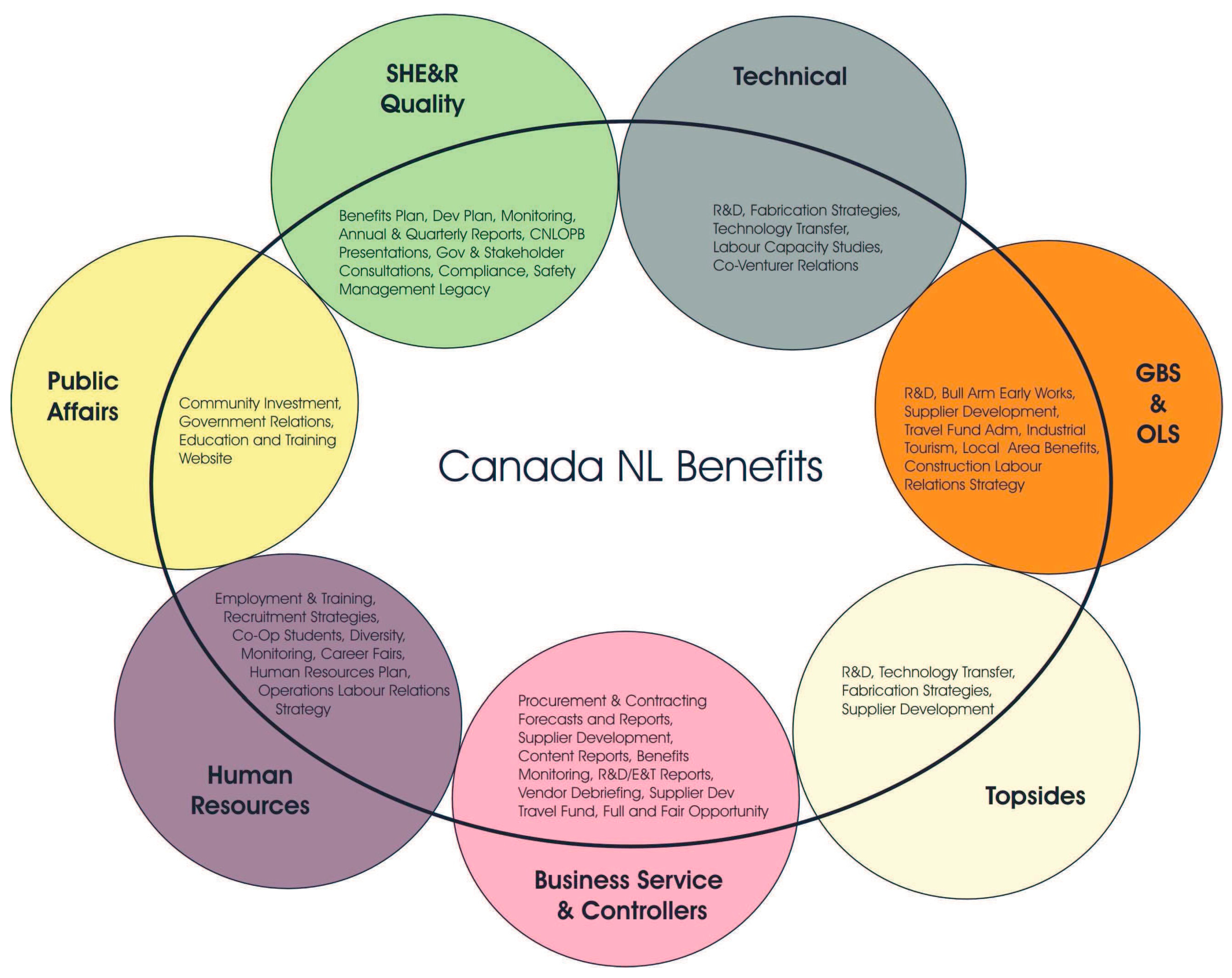

First, there is moral inversion. As with all oil companies, ExxonMobil continues to morally invert the side-effect of its now dangerous organisational goal into something good: greater oil consumption will improve the economy, increase job opportunities, raise tax revenues, and generally increase (contemporary) humankind’s standard of living (SRM). Consider, for example, the below diagram (

Figure 2) outlining the “benefits” expected from ExxonMobil Canada’s Hebron off-shore Newfoundland oil field project:

This document details Hebron’s “effect on the economy”,

Hebron will create large amounts of business and employment in the Province during all phases of activity. This will, in turn, create spin-off business and employment, as well as create new revenues for government through personal, business and property taxes.

11

If any prospective or current Hebron employees express reservations about working for a company that greatly contributes to climate catastrophe (and, as it turned out, the “Largest oil spill in N[ewfoundland] history” as one headline put it),

12 ExxonMobil management can, as Milgram did, substitute hesitant with more eager helpers.

Once the oil economy functionaries agree to contribute to the goal of profit maximisation, all—if they so choose—can secondly engage in various forms of denial (like, for example, denying their awareness or doubting the existence of climate catastrophe). If such denials are unfeasible, because “others” across the division of labour are involved, all can then simply diffuse or displace elsewhere personal responsibility for their contributions to climate catastrophe. Let us briefly consider these options.

Because of contemporary society’s widely discussed and near total cognizance of climate catastrophe, awareness denials are difficult for any person in good faith to maintain. However, the existence of those within the oil economy denying the reality of climate catastrophe is more common. Interestingly, within this denial community, the holding of two Milgram-like contradictory perspectives can be found. For example, in his (apparent) beliefs, current U.S. President Donald Trump (who hired ex-ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson as his Secretary of State)

publicly denies the existence of climate catastrophe: “… GLOBAL WARMING-a total hoax!”

13 However, in

private he, as Milgram did, can be found protecting his personal interests by pursuing actions that contradict this belief (e.g., Trump’s desire to build a sea wall to protect his golf course in Ireland from, as noted in his company’s planning application to the Clare County Council, the effects of “Predicted sea level rise and more frequent storm events”).

14Much more common than the deniers, however, are those who present arguments that inadvertently encourage the diffusion of responsibility over climate catastrophe. On this topic, consider, for example,

Heede’s (

2014) carbon inventory, which led him to blame a small number of corporations for climate catastrophe. According to him, one-fifth (19%) of all CO

2 released between 1854 and 2010 traces back to seven private and state-held companies: Chevron, ExxonMobil, Saudi Aramco, British Petroleum, Gazprom, Royal Dutch/Shell, and the National Iranian Oil Company (

Heede 2014, p. 237). This finger-pointing provoked UC San Diego’s David Victor to respond with a popular counterargument: Heede’s research is “part of a larger narrative of trying to create villains; to draw lines between producers as responsible for the problem and everyone else as victims. Frankly, we’re all the users and therefore we’re all guilty.”

15 Another energy expert, UC Berkeley’s Severin Borenstein agreed: “It’s a cop-out to blame the producers of products that we have demanded, and benefited from, for more than a century …”

16 However, Carroll Muffett, from the Center for International Environmental Law disagreed. In support of Heede having narrowed down climate catastrophe to a small group who are

most responsible, he inadvertently alluded to how bureaucratic organisation helps diffuse personal responsibility to the point that it renders those most responsible invisible: “For decades there’s been a persistent myth that everyone is responsible,” but “… if everyone is responsible then no one is responsible”.

17 Of course, if it is widely accepted that no one will ever be held accountable for climate catastrophe, why would those Heede objectively demonstrates are most responsible ever stop pursuing their disproportionately destructive actions? In terms of the displacement of responsibility, consider, for example, ex-ExxonMobil CEO Rex Tillerson who conceded that human-induced climate catastrophe is real,

18 but who simultaneously advocated in favour of extracting what, thanks to gradual warming, has become the economically more viable

19 and potentially massive Arctic oil reserves.

20 How does Tillerson square his belief in climate catastrophe with his support for increased oil production? Tillerson does so by relegating the importance of his own role as a powerful decision-maker by choosing to displace all blame for climate catastrophe onto consumers: “It’s back to that insatiable appetite that the world has for energy. Oil demand is going to continue to grow.”

21 Who, then, do consumers blame for climate catastrophe? They can often be found blaming weak political leaders who cave to the pressure of corporation-sponsored lobby groups. In several countries, this has manifested into lawsuits filed against governments, in particular Colombia

22, Norway

23 and the Netherlands.

24 With some success, many of these cases have been initiated by younger plaintiffs—the present generation most likely to be affected by climate catastrophe—suing either their own governments

252627 or specific leaders.

28 De Smet et al. (

2016) more specifically highlighted the failure of the political community as a whole to fulfil its responsibility at the input-side of the delegation of authority. Who, then, do the politicians blame for climate catastrophe? Similar to Tillerson’s blaming consumers, one of several possible targets involves politicians pointing the finger at the voting public (see

Bache et al. 2015).

29 Politicians do so because if they tried to substantively curb fossil fuel consumption, such policies would, as

Giddens (

2009, p. 11) put it, prove “unpopular” and (somewhat in support of Tillerson’s point) then be “actively resisted” at the start of the next electoral cycle. As one political official stated, what matters is “what wins votes not what matters in the long-term” (quoted in

Bache et al. 2015, p. 84). Of course, what the vast majority of working, middle, and upper-class voters are most impressed by is what presently affects them: a perennial obsession with continuous economic growth and more jobs (

Bache et al. 2015, p. 78).

At the expense of overemphasising our point, the ability of all links in the chain to simply deny the awareness/existence of harm-doing,

30 diffuse, or displace responsibility for their harmful contributions traces back to the ambiguous state of personal responsibility inherent within divided and compartmentalised means of bureaucratic organisation. Most importantly, all links across the organisational chain can engage in denial, responsibility diffusion, and responsibility displacement while continuing to make (and benefit from) their harmful contributions to the wider process. Consequently, responsibility ambiguity at each link across the GHG emitting organisational process has generated a blame-avoidant “accountability vacuum” (

Bache et al. 2015, p. 65).

Third, once all links in the oil economy organisational chain commit to role fulfilment, the inherently coercive and strain-resolving effect of bureaucratic momentum can then exert its influence. That is, once set in motion, all functionaries are likely to feel the coercive push and pull of preceding and succeeding links to perform their specialist role within the wider process. For example, after the engineering infrastructure is constructed, those extracting unrefined oil feel obligated to fulfil their roles within the wider process. When the unrefined oil arrives at the refineries, to inhibit a systemic bottleneck from forming, the refiners feel pressure to do their bit. The refined product is passed on to the next step in the process, thereby generating the same pressure of role fulfilment. Even the last-link consumers feel, albeit more subtly, the pressure of bureaucratic momentum. As President George W. Bush reminded Americans in 2006: to keep “our [oil-based] economy growing” it was important they fulfil their essential roles in the wider process, upon which he then encouraged them “…all to go shopping more.”

31 Again, bureaucratic momentum can have a strain-resolving effect on a potentially guilty conscience because if functionaries feel someone (or something else, e.g. capitalism) is most responsible for generating pressure to engage in role fulfilment, then the former can blame the latter as most responsible for their decision to continue contributing to harm infliction. In all these ways bureaucratic momentum helps further advance feelings of responsibility ambiguity.

Additionally, bureaucratic momentum makes difficult a functionary’s decision to suddenly disengage from role fulfilment. Similar to during the Obedience Studies, refusing to fulfil one’s role requires forfeiting all self-interested benefits and (at least in the short term) inhibits other predictably angry functionary helpers from accessing whatever benefits—typically economic—they anticipated in exchange for making their contributions to goal achievement. For example, imagine the financial sacrifice

and wider social pressure (abuse) likely encountered by petroleum fuel truck drivers who—perhaps motivated by the

Extinction Rebellion movement

32—collectively refused to make their deliveries to petrol stations. Bureaucratic momentum thus structurally helps ensure that to “get along” it is just easier for all functionaries to “go along,” even if all happen to be heading in a foreseeably Obedience study-like “ugly” direction. Thus, for all functionaries, bureaucratic momentum helps ensure unethical decisions come easily and ethical ones are threatened by the burden of personal sacrifice.

Fourth, there is the foot-in-the-door phenomenon. For example, as the oil economy has grown, so have GHG emissions: 320 ppm in 1965; 330 ppm in 1975; 345 ppm in 1985; 360 ppm in 1995; 380 ppm in 2005; and 400 ppm in 2015.

33 Is it possible that, foot-in-the-door-like, we have all been drawn into taking more and more seemingly insignificant little steps up the metaphorical carbon parts per million “shock board”? The half-century increase from 320 ppm to 400 ppm is a radical shift, but because penultimate emission recordings only differ slightly to the latest record-breaking measurements, most people remain unperturbed by each small increase. We simply acclimatise to a new slightly more radical normal.

Who, then, is really to blame for the present inability to avert climate catastrophe? In support of Victor and Borenstein, the simple (convenient?) answer is that, as consumers of oil products, we are indeed all responsible. Nobody set out to cause climate catastrophe so it is tempting to “

feel responsible only for what we intend;” but as

Sabini and Silver (

1982, p. 66) then add, we are still “responsible for all that we do …”

34 However, what we oil consumers typically fail to recognise is that similar to the participants at the end of the Obedience organisational process, having

options in terms of our preferred course of action means that we fulfil somewhat powerful positions: we have the power to choose. The level of power invested in these choices becomes more obvious when it is compared to those beings in the future with no such choice; those who must suffer the devastating consequences of our choices—

Gardiner’s (

2014, p. 301) so-called “tyranny of the contemporary”. From this perspective, because we, particularly those across all classes in the developed world, have thus far self-interestedly chosen inaction as our preferred course, it can therefore be argued that in choosing a path that will gravely affect future beings, we (similar to Milgram and his helpers) are essentially abusers of our greater (largely invisible) power.

35 Here in lies Friedrich’s answer to the question surrounding the present failure to avert climate catastrophe:

We often prefer denial to confronting our problems, inescapable as they may be. We often shirk from responsibility for our share of the mess and hope that others will do the clean-up. We have an immoral tendency to weasel out when we feel that the bill will be footed by distant strangers or future generations. And we are lo[a]th to accept as true something that might jeopardise our cherished way of life. Therefore, some of us are more than willing to listen to charlatans telling us what we like to hear, for example that climate change is a hoax and that we should think positively and all will be well.

36

Although we see some merit in Victor and Borenstein’s popular argument that everybody is responsible for climate catastrophe, we ultimately side with

Heede (

2014) that

certain links in the organisational chain are much more responsible than others. We more specifically place particular blame on those in key corporate leadership positions; particularly powerful figures including the likes of Lee Raymond, Rex Tillerson, and Darren Woods—members of the so-called “

carbon-capital elite” (

Carroll 2017, p. 229). The main reason we side with Heede’s argument is because, as the following illustrates, these leaders have long known about climate catastrophe and they—as powerful Milgram-esque social engineers—have effectively used their access to enormous organisational resources to manipulate the choices made by their less powerful oil-economy functionaries, investors and consumers.

In support of these arguments, consider for example, that Exxon scientist James F. Black was one of the first people aware of the human-induced GHG effect.

37 In 1977, Black warned Exxon executives that rising CO

2 emissions “could harm the environment and humankind” (

Banerjee et al. 2015, Part 2). Largely because of “the threat accumulating CO

2 posed to the company’s core business”, Exxon undertook a wide range of climate-related research that from the late 1970s to the mid-1980s led to their scientists, managers, and executives developing a “sophisticated understanding of the potential effects of rising CO

2 concentrations” (

Banerjee et al. 2015, Part 2). In 1979, Steve Knisely, a young Exxon research intern, informed one curious vice president that, if emissions were not reduced, by 2010 there would be about 400 ppm of CO

2 in the air (

Banerjee et al. 2015, Part 3). His prediction was only five years off. By 1982, Roger Cohen, head of theoretical sciences at Exxon’s Corporate Research Laboratories, said regarding their climate research, “a clear scientific consensus has emerged” (quoted in

Banerjee et al. 2015, Part 3). In fact, Exxon’s climate science was so advanced that time proved their models to have been far superior to similar models at MIT (

Banerjee et al. 2015, Part 3). Documents—typically “restricted to Exxon personnel”—demonstrate that, although “scientific uncertainties” remained, Exxon scientists, managers, and executives were nonetheless aware of the

likely negative effects associated with accumulating GHGs (

Banerjee et al. 2015, Part 3). The statistical uncertainty inherent in their own (and others’) accumulating research, however, did not stop Exxon during the 1990s from protecting their bottom line by climate change-proofing some of the corporation’s oil-extraction infrastructure.

38 Nonetheless, somewhat similar to Milgram’s secret awareness that his experiment could be dangerous, Exxon’s leadership knew decades ago about “potentially catastrophic events”—rising sea levels, increased human migration, reduced albedo effect, and increases in various weeds and pests—that “might not be reversible” (

Banerjee et al. 2015, Part 3, Part 2).

Despite this, however, after Hansen’s 1988 Senate speech followed by the sudden and thereafter increasing public awareness about climate catastrophe, Exxon and then ExxonMobil chose to pursue an aggressive campaign of what

Virilio (

2000, p. 49) terms the “remote guidance of confusion …”

39 That is, in 1989 the oil giant helped fund the formation of the Global Climate Coalition,

40 and later climate change denial scientists (e.g., Willie Soon), politicians, and lobbyists, including Randy Randol and Joe Walker (SRM) (see

Union of Concerned Scientists 2007;

Farrell 2016a;

Banerjee et al. 2015, Part 6, p. 1;

Ward 2006). Many of these figures proposed alternative (statistically improbable and quickly debunked) non-anthropogenic theories to explain away rising average global temperatures (

Farrell 2016b;

Supran and Oreskes 2017). Then, across nine newspapers in the late 1990s and early 2000s Mobil/ExxonMobil published advertorials to audiences reaching into the millions, some of which promoted the climate change “doubt” scenario (

Brown and Waltzer 2005, pp. 199, 201;

Supran and Oreskes 2017). Characteristic of such advertorials was, for example, in 2000 when, in The Washington Post, an ExxonMobil advertorial criticised a US National Assessment report on climate catastrophe, stating it had put the “political cart before a scientific horse” and was based “on unreliable models” (see

Supran and Oreskes 2017). Later, ExxonMobil also included statements in their 2005 Corporate Citizen Report that questioned the accuracy of the IPCC’s then latest assessment, which

Ward (

2006) from The Royal Society (the U.K.’s premier scientific academy), described as “very misleading.” As

MacKay and Munro (

2012, p. 1530) conclude:

… ExxonMobil has embarked on a deliberate campaign of confusion and disinformation, producing a counter-science to manufacture public uncertainty by funding a diffuse network of ideologically driven advocacy organizations, as well as other issues management, public relations, lobbying and legal tactics.

This carefully coordinated—eventually industrywide

41—misinformation campaign took advantage of the inherent uncertainty in all climate science modelling data—a methodological approach that makes assertions based on probabilities not certainties. This is illustrated in the statements of some Exxon and ExxonMobil CEOs. For example, despite all of Exxon’s previous research, in 1996, CEO Lee Raymond argued: “Currently, the scientific evidence is inconclusive as to whether human activities are having a significant effect on the global climate” (

Banerjee et al. 2015, Part 6). Because, as mentioned, in his actions over his words, Raymond was, around this point in time, climate change-protecting some of his corporation’s oil-extraction infrastructure, it is difficult to accept the sincerity of his statement. Two decades later and after five IPCC Assessment Reports, in 2015 a cautious Rex Tillerson sounded almost as uncertain as his predecessor: “What if … it turns out our models are lousy, and we don’t get the effects we predict?” (quoted in

Banerjee et al. 2015, Part 6).

Falling in line with the views of those at the top of the corporation, Exxon/ExxonMobil scientist Roger Cohen became a sceptic of his previously mentioned 1982 scientific “consensus…” Even after retiring from ExxonMobil, Cohen described on a climate denial website the IPCC’s 2008 case for anthropogenic global warming as “flimsy” (quoted in

Banerjee et al. 2015, Part 3). Perhaps in desperation to help move the political conversation beyond the resilient issue of doubt, in 2007, the world’s largest organisation of physicists—the American Physical Society (APS)—forcefully concluded: “The evidence is

incontrovertible: Global warming is occurring” (

Banerjee et al. 2015, Part 3 [emphasis added]). Roger Cohen and several others criticised the APS’s use of this unscientific word and in 2009 and 2010 petitioned the organisation to remove it (

Mann 2013, pp. 196–97).

42 Despite the IPCC moving from a conservative >66% (2001: “likely”), >90% (2007: “very likely”), to 95–100% (2013: “extremely likely”) probability that increased warming over the last half-century was due to human activity (

Palmer 2014, p. 5), in 2015, the APS finally backed down. That is, the APS removed the word “incontrovertible” and inserted the following scientifically more rigorous yet far less definitive (doubt-sowing?) sentence:

Although the magnitudes of future effects are uncertain, human influences on the climate are growing.

43

As

Banerjee et al. (

2015, Part 3) put it, “As the consensus grew within the scientific world, Exxon doubled down on the uncertainty.” However, over time, Exxon/ExxonMobil’s preferred position of public denial of human-induced climate catastrophe has become—in the face of an overwhelming mountain of scientific evidence—increasingly untenable. As a result, the corporation was forced to gradually shift their public position from denial (Lee Raymond),

44 ambivalence (Rex Tillerson), to it conceding that human-induced climate catastrophe is likely to be real (Darren Woods).

45 Under CEO Woods, ExxonMobil now (apparently) supports “advancing effective solutions to address climate change.”

46 This “softer, ‘climate friendly’” (

MacKay and Munro 2012, p. 1509) image, however, likely lacks substance. The title of one recent article by The Economist dated 9 February 2019, for example, says it all: “ExxonMobil gambles on growth—A fossil-fuel titan’s strategy is at odds with efforts to hold back climate change …”

47 ExxonMobil today continues to bank—much as Tillerson did when he was at the helm—on consumer demand for oil increasing. Therefore, ExxonMobil’s new more climate responsible image is largely greenwash and more about the corporation’s desperate attempts to neutralise (socially engineer) the increasingly critical concerns of present and future employees, investors and consumers. Technically speaking, the ExxonMobil website’s latest “climate friendly” words are what

Milgram (

1974, p. 159) termed a mere “balm to the … conscience”: a suddenly introduced behavioural change that actually did little more than enable “obedient” participants to feel better—more at ease—about the ugly direction they thereafter continued to head.

48 On the issue of disinformation, for example, according to a 31 August 2018 article by the Union of Concerned Scientists, ExxonMobil continues to fund climate science denier groups.

49 Perhaps this is why during Geoffrey Supran’s 21 March 2019 expert parliamentary testimony to the European Union, ExxonMobil received a special mention:

… this evidence points only one way: fossil fuel companies and trade associations, including ExxonMobil, have variously promoted disinformation about climate change so as to stifle action by misleading our public and politicians.

50

Woods, who initially planned on attending this meeting, failed to show up.

51Most disconcerting, however, is that because public doubt surrounding the advancing scientific consensus on anthropogenic climate change has been “substantial and growing” (

Anderegg et al. 2010, p. 12107), some scholars conclude that ExxonMobil’s war of disinformation was “broadly successful” (

MacKay and Munro 2012, p. 1529) and has “… largely succeeded.”

52 Thus, despite ExxonMobil (apparently) having changed its unethical ways, the damage has been done: the reverberating echo chamber of climate catastrophe doubters likely continues to exert influence.

Why, then, would ExxonMobil pursue a campaign of confusion? As with Milgram, when more knowledge threatened ExxonMobil’s core self-interests (their bottom line), corporate leadership deemed it necessary for the(ir) greater good to massage the truth, omit certain facts, and tell complete lies. In addition, similar to Milgram, they accepted the risk that others would be harmed because they rather opportunistically sensed, as the powerful often do, their probable immunity from culpability. Again, they could act with impunity because (1) of the uncertainty always inherent in scientific data and, when overwhelming evidence made their doubts sound ridiculous, they could, as Tillerson eventually did, (2) capitalise on the responsibility ambiguity inherent in the division of labour by displacing responsibility for climate catastrophe onto others. Conveniently lost in the fog of responsibility ambiguity, past and present ExxonMobil executives have likely sensed that their harmful decisions would be rewarded in the short term and never punished in the long term. Much as Milgram did during the running of his Obedience Studies, it seems all the corporate executives involved felt sufficiently “covered.” Furthermore, (3) they could likely act with impunity because—and this one applies to nearly all of us—by the time the disaster really takes hold, they (we?) will probably be dead. On this note, would the present course of inaction to climate catastrophe apply if the majority of leading climate scientists suddenly issued a dire warning that within the next couple of years the Earth would become an inhabitable dead zone? With essentially nobody able to act with impunity, how would the present and largely “nothing can be done” attitude fare?

53Most egregiously, though, is that as Tillerson blames consumers for climate catastrophe, he conveniently skirts over his ability as a powerful and influential figure in the organisational infrastructure to (as Milgram did) exert immense manipulative control over the content of the information received by his relatively less powerful helpers further down the organisational chain. As our ExxonMobil case study illustrates, the content of that (mis)information can and likely has had a powerful influence over the detrimental choices these lower-level helpers—particularly investors and consumers—continue to make. As said Milgram, who during his numerous pilot studies gradually learnt how to best manipulate most participants into inflicting every shock (see

Russell 2018, pp. 37–78): “Moral factors can be shunted aside with relative ease by a calculated restructuring of the informational and social field” (

Milgram 1974, p. 7).

54 Thus, as with Milgram blaming “moral imbeciles” for completing his experiment, when Tillerson blames consumer demand for impending climate catastrophe he fails to acknowledge his own furtive role aimed at structurally ensuring investors, employees, and consumers shunted all climate catastrophe-related moral factors aside.

Interestingly, as illustrated by Milgram’s previously mentioned

Subject Free to Choose Shock Level condition, when ordinary people at the end of an organisational chain (e.g., consumers) are aware of the harmful consequences of their actions and they are then offered the unimpeded option to act ethically, 97.5 per cent chose to do so. As long as their self-interests are not too heavily compromised by manipulative up-stream meddling, Milgram’s research clearly illustrates that most people prefer to pursue what they understand to be the morally right course of action. Thus, perhaps more than any other factor, our present inability to avert climate catastrophe is largely an abuse of (mostly higher) power and a total failure of leadership.

55 The fish rots from the head down.