3. Results

The episodes below arose when students discussed their goals for the future, chose their challenges of the month, and then reflected on the activity. These conversations were chosen purposefully since they show an apparent effect on students’ goal setting, regardless of whether students meet their goals.

3.1. Gabriel’s Challenge of the Month

Episode one in

Table 2 took place when Gabriel shared his goals for the future. One of the goals he had was buying a movie ticket by himself. Sebastian and Nicole suggested that he should save in a moneybox the money he did not spend at the university.

Episode two in

Table 3 took place in a later session when the students formally chose their challenges of the month. In this episode, Gabriel remembered his peers’ suggestion and chose “to save money” as his challenge of the month.

As shown in episodes one and two, prior to filling in their challenge of the month forms, Gabriel’s peers and facilitator had suggested that Gabriel save the money he did not spend at the university to meet his goal of buying a movie ticket by himself. These conversations set the ground for Gabriel to choose his challenge and he filled in his form accordingly. After choosing his challenge, courses of action were proposed to achieve it, as well as to regularly track his progress on the form.

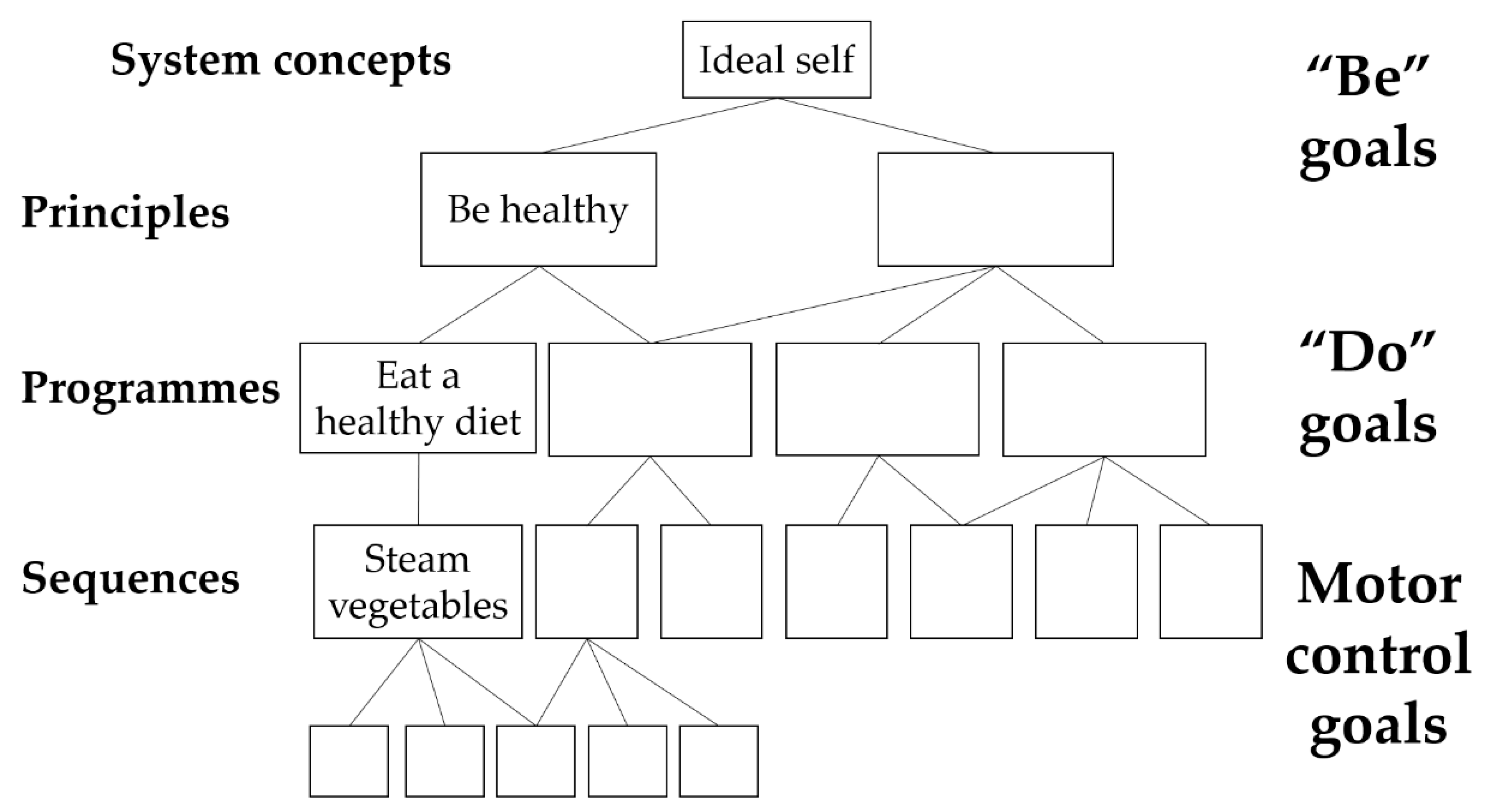

Figure 3 gives an overview of Gabriel’s goal and the courses of action that were proposed organised into their level of abstraction/concreteness.

It is important to mention that, at the time of the intervention, the facilitator was not aware of the levels of abstraction/concreteness at which the discussions remained, so she did not employ these explicitly. These levels were identified during the data analysis.

Gabriel’s goal was to buy a movie ticket. “Buy a movie ticket” was categorised as a ‘Do goal’. The conversations revolved around other ‘do goals’ to accomplish this overarching goal. Therefore, the highest level of abstraction discussed in relation to Gabriel’s goal was the ‘do goal’ “buy a movie ticket”, since it was the reason why the rest of the actions were proposed (

Figure 3). The reasons behind Gabriel’s interest in buying the ticket, (i.e., be goals) were not discussed.

The conversations in which courses of action were proposed to achieve Gabriel’s challenge follow. In episode three in

Table 4, the facilitator took up Gabriel’s challenge as an example to illustrate how to fill in the Challenge of the month form. Firstly, she explained that the form said “March” on the top because that was the month running at the time. Then, the participants discussed how to fill in the form and how to regularly monitor Gabriel’s progress.

In episode three, details on how the ‘do goal’ “save money” could be facilitated were discussed at a lower level of abstraction: “having a moneybox in Gabriel’s locker” and “ask support from his teachers and/or parents”. The facilitator also asked questions on how to track Gabriel’s progress on the form. At the lowest level of abstraction, participants proposed actions related to specific forms of tracking progress on the challenge of the month and suggesting people to get the moneybox from.

It is also relevant to mention that, although the challenge discussed was Gabriel’s, sometimes teacher Amy, Sebastian, Nicole and the facilitator contributed to the conversation without really promoting Gabriel’s active participation, even referring to Gabriel in the third person in some occasions. Moreover, many of the questions the facilitator asked Gabriel were closed-ended, thus maintaining a directive role over the task (e.g., turns 1224 and 1246).

Conversations continued once Gabriel started working on his goal. For instance, week by week Gabriel chose how much money he would put in his moneybox based on the money he had left over. After two weeks of saving $10 Mexican pesos his peer Sebastian proposed to Gabriel a course of action: “If you want, well, if you have enough, you can put more [money] in… I mean, it doesn’t have to be $10 always”. Gabriel nodded in agreement but did not put more money in, even though he had more left-over money in his wallet. Sebastian repeated, “You could put another $10 if you wanted to” Gabriel replied “Yes”. I intervened “But you don’t want to?” To which Gabriel shook his head indicating no. After having a look at this form, we concluded that it would take him another three weeks to save enough money for a movie ticket if he continued saving $10 per week and he was comfortable with that.

After two more weeks of saving money ($20 in one week and $10 in the other), Gabriel saved enough money to buy his movie ticket. In relation to this Gabriel said he felt “very good… because I will be able to achieve what I set for myself this month”.

3.2. Nicole’s Challenge of the Month

When choosing her challenge, Nicole mentioned that she was undecided between two of the goals she had shared in a previous session. After a brief discussion, she chose her challenge of the month (

Table 5).

In episode four, Nicole chose her challenge of the month after the facilitator focused the conversation on a key aspect of the activity: that the challenges were meant to achieve goals (turn 1407).

Figure 4 shows an overview of Nicole’s goal and the courses of action that were proposed, organised into their level of abstraction/concreteness.

Nicole proposed as her challenge of the month ‘to follow her diet’. This was one of the goals that Nicole shared when she had talked about her goals for the future in a previous session: “[I want to] keep my diet because I want to have a healthy life, without diseases and pain”. This aim of ‘Being healthy’ was thus considered the highest level of abstraction discussed in relation to this goal (

Figure 4). After choosing her challenge, the facilitator and Nicole discussed how she would monitor whether she was following her diet (

Table 6).

Nicole shared that she wanted to follow her diet to reach her ideal weight. Thus, to “follow a diet” was thought of as a means to “achieve ideal weight”, which in turn was a means to “be healthy”. Therefore, we categorised “achieve ideal weight” and “follow diet” as ‘Do goals’ to achieve the ‘Be goal’ of being healthy. Two ways of following a diet were briefly discussed: following a set menu or eating with moderation. Nicole focused the conversation on the latter and the facilitator proposed a way to track her progress on the challenge of the month form. This tracking on the form was the lowest level of abstraction discussed relating to this matter.

Nicole maintained this challenge of the month for the three months that this activity lasted. She usually reported feeling “good” with her progress in the activity. On the days that Nicole considered having eaten healthily, she put a tick on her form; this was on most days. When she ate junk food, she marked the day with a cross and wrote down the junk food consumed, e.g., “pizza, hamburger, cornbread”. When discussing this in one of our later sessions she explained that she could eat junk food once a week: “once a week, my doctor says yes”. At the end of the activity, Nicole was still two kilograms above the recommended weight. However Nicole commented: “[the challenge of the month form helped me] to see what days I failed so that the next day I would not fail with my diet and say no, here I failed and today I do not have to fail in my diet and I have to keep it well”.

3.3. Sebastian Chooses His Challenge of the Month

Sebastian proposed as his challenge of the month to take his own breakfast from the independent-living flat where he lived to the university (

Table 7).

The interaction between Sebastian and Nicole in turns 1425 to 1426 is interesting because, after having chosen his challenge, Sebastian incorporates Nicole into the conversation by asking for her confirmation: “Sometimes I forget, right?” It makes sense that Sebastian asked Nicole for her confirmation since both were very close friends and usually sat down together in the university cafeteria during mealtimes. Nicole answered by focusing Sebastian on the question the facilitator had previously asked: “But which days do you want to bring breakfast, or all week?”. In this way Nicole provided support to her peer to move his task forward.

In turn 1432, the facilitator posed the question to Sebastian “What is your goal?” and as a scaffolding strategy to encourage Sebastian’s response she gave him some options: to bring breakfast every day, at least three times a week. However, with these options she was assuming that Sebastian’s goal was related to bringing food to the university on a certain number of days per week. Fortunately, Sebastian clarified the previous contribution shedding light onto what his goal was: “trying not to spend so much money”.

Figure 5 shows an overview of Sebastian’s goal and the courses of action that were proposed, organised into their level of abstraction/concreteness.

Sebastian’s goal was discussed at the ‘Do goals’ level only, similar to Gabriel’s case. The conversations in which these propositions aroused are transcribed below (

Table 8).

At the beginning of the previous episode, the facilitator moved the conversation towards completing the challenge of the month form by asking: “Ok then what are we going to do? The days that you bring breakfast, you’ll cross them out or how are you going to mark there that you did bring breakfast?...” (turn 1468). Consequently, a ‘Do goal’ was proposed, i.e., to fill in the form (turn 1474). The suggestion was elaborated in the following turns. In turn 1477, the facilitator posed a different question: “How do we do it so that every day you remember to mark if yes or no?” Sebastian and Nicole proposed courses of action (turns 1481 and 1490); however, they were not related to the question that the facilitator was posing. In the following episode, the facilitator rephrased the latter question (

Table 9).

In episode eight it is interesting to see how Sebastian asks Nicole for support to fulfil his goal. However, the facilitator hinted at a different course of action that would allow Sebastian to achieve his goal without relying on Nicole.

As described in episodes six to eight, Sebastian’s goal was to spend less money. “Spend less money” was the goal at the highest level of abstraction because it is the reason why the rest of the courses of action were proposed. To spend less money, Sebastian proposed to “bring his own breakfast to the university” rather than buying it there. To do so, he proposed to “prepare breakfast the night before”. The facilitator focused the conversation on ways to track down Sebastian’s progress on the form. Other regular ‘Do goals’ were proposed: “cross out the days when Sebastian brought breakfast” and “ask for support”.

After a few weeks, Sebastian changed his challenge of the month to stay within a daily budget of

$100 Mexican pesos for food expenses at university. Taking his own breakfast was one of the suggested strategies to stay within this budget. Nevertheless, Sebastian found it challenging to keep his daily expenses within his budget (

Table 10).

Episode nine shows the importance of following up the intervention with further discussions. At the end of the challenge of the month activity, Sebastian started a job in a museum. This brought about changes in Sebastian’s routine, including taking food to work daily. At this Sebastian reflected: “[Staying inside the budget] was a big challenge. Most of the time I was over budget because I would have to take breakfast from my flat to the university. From this I learned that it was better to prepare a meal and now that I am working in the museum, I take my food. This has helped me save money”.

4. Discussion

The challenges of the month were aimed at meeting some of the students’ goals. Additionally, some courses of action were proposed to carry out these challenges and monitor them regularly.

The episodes show that students chose their own challenges based on their goals and that they perceived the activity as beneficial to meet their challenges. However, the episodes also show how the students’ goal setting was affected in relation to the level of abstraction at which discussions remained. In relation to the latter, the findings revealed that the discussions were mainly on specific and concrete actions to achieve goals (i.e., ‘Do goals’). This was mainly due to the facilitators’ interest in students meeting their goals and learning a self-regulation strategy that allowed them to monitor their progress. Furthermore, at the time of the intervention the facilitator was not aware of the level of abstraction/concreteness at which the conversations were taking place. However, by focusing on the “hows” there were almost null opportunities to explore the students’ overarching motivations behind their goals (i.e., ‘Be goals’). We argue that to move from practices that train students to achieve goals to pedagogies that truly acknowledge the students’ experiences, bearing in mind these levels of abstraction/concreteness might be useful.

Moreover, leaving the conversation at a ‘Do’ level may potentially limit the students’ self-determination. If we are to advocate that self-determination is not only to do with mastering a set of skills but more with volition and becoming causal agents in one’s life (

Wehmeyer 2005), we must foster educational interventions that promote the students’ consciousness and intentionality in their decision-making process. In this way, the role of teachers is to promote students to express their interests and preferences and truly involve them in the decision making processes that concern them.

Freire (

1970) claims that pedagogies are to be developed through a constant dialogue in which the emergence of consciousness and individuals’ critical intervention in reality is sought. Therefore, to promote students’ self-determination, a first step would have to be to talk to them about their ‘Be goals’ to better understand their experiences and understanding of self-determination. Perhaps in this way, we could move from thinking of “setting goals” as a skill that people with disabilities must master, to an opportunity to open-up a space in which people with disabilities articulate a discourse contrary to the labels of “deficiency” that are still attributed to them. Moreover, the students’ consciousness might be promoted by encouraging them to reflect on their motives behind their goals.

In addition to the level of abstraction, the findings revealed other ways that could risk the self-determination of the students. The findings show that even when students are present, and efforts are made to involve them in the conversation, there might be times when students may be agreeing passively while others talk about them in the third person, as happened with Gabriel in episode three. Even though giving students response options is a common pedagogical strategy, educators must also ensure a classroom ethos in which the students can disagree or give another option that truly reveals their desires. In episode six, the facilitator gave options to scaffold Sebastian’s response after asking him what the goal was he was pursuing in his challenge of taking breakfast to his university. The options provided by the facilitator had to do with bringing breakfast a certain number of days per week. In response, Sebastian stated that his goal was to spend less money. In this example, the scaffolding strategy worked well since it prompted Sebastian’s response. Moreover, in his response Sebastian discarded the options the facilitator had given him and instead expressed what his goal was. Unfortunately, there may be times when students simply choose options that do not correspond with their desires and go unnoticed.

These findings taken together show the importance of looking into interactions in detail to promote educators’ reflection on their practices and come up with strategies that help educators in this process. Reflective inquiry is a method that has been proved to be helpful in teacher’s professional development (e.g.,

Lyons et al. 2013;

Rodgers 2002;

Vrikki et al. 2019). It takes place when practitioners observe carefully and reflect critically on their own practice in order to enhance the teaching-learning process. A resource aimed to support educators’ inquiry in relation to dialogic teaching practices is the Teacher Scheme for Educational Dialogue Analysis (T-SEDA) (

http://bit.ly/T-SEDA). Future research could use resources like T-SEDA to support teachers’ inquiries into opening up dialogic spaces that promote self-determination and the monitoring of what happens over time.

In another vein, it was interesting to see that having a discussion space in which not only teachers but also peers participate opened the possibility of giving and receiving support among peers. Social support is key to optimal functioning within a social context (

Jackson et al. 2005). In the inclusive education field, much has been said about the importance of providing support to students identified with a disability (e.g.,

Buntix and Schalock 2010). Research has documented the benefits associated with peer support in teenagers and young adults (e.g.,

Carter et al. 2005;

Vogel et al. 2007). Nevertheless, students identified with a disability tend to be tutees receiving support from a peer that has not been identified with a disability. The findings documented in this research show the potential of students with ID to take the role of active tutors and not just to assume the novice role that they tend to be given. Even more so, when dealing with topics that directly concern the life of the student, their active role is fundamental. In the words of

Nirje (

1972, p. 177) in relation to the right to self-determination:

the choices, wishes, desires, and aspirations of a [person with a disability] have to be taken into consideration as much as possible in actions affecting him… It is especially difficult for someone who has a disability or is otherwise perceives as devalued... Thus, the road to self-determination is indeed both difficult and all important.

A limitation of this study is that the findings come from conversations with the only three students involved in the “Challenge of the month” activity in the context of the wider study. The replication of this study with a larger sample and/or with other groups of students with ID is thus recommended in future research projects. Another limitation was that in most cases the students put into practice the courses of action by themselves. This limited opportunities for intervention that would favour the achievement of goals. In this study, the researcher decided to limit her intervention while the students exercised their courses of action for two reasons. First, the students exercised these courses of action in moments and settings in which the researcher was not always present (e.g., independent-living flats, mealtimes). Second, even if present, the researcher considered that her intervention could be counterproductive for the social inclusion of the students in certain scenarios. For example, in the university cafeteria, Sebastian had to decide what to buy to stay within his budget. The researcher could have stood by him and guided his purchases. However, the presence of a teacher/researcher in these moments in which students come together with other university students could favour labels of “dependency” usually attributed to people identified with ID. Nevertheless, an interesting and useful implementation in future research could be to plan strategies through which researchers and teachers could follow the students more closely in the implementation of courses of action since it is key for the achievement of their goals (

Zimmerman 2005).

The results shown in this paper do not translate straightforwardly into effects on self-determination. We believe that to have a broader vision of the students’ self-determination, observations of their interactions with different agents and in different contexts might be helpful, as well as conversations that shed light into their own definitions of self-determination. A brief example is shown in

Table 1 which describes some other aspects related to self-determination that the participating students experienced at the time of intervention. However, we hope the findings here reported contribute to the field. First, we show examples of agency and the active role that students with intellectual disabilities take both by proposing courses of action to achieve their goals, and also by suggesting strategies to their peers to do so. These Zones of Proximal Development (ZDP,

Vygotsky 1988) which emerge between peers may be of great interest for analysis in future research. Second we would argue that educators need to take a more active role in supporting students’ agency by inquiring purposefully about the students’ “Be goals”, which did not generally appear in the students’ conversations. This is an important reflective strategy required to promote students’ consciousness and intentionality and thus, potentially, their self-determination.

Moreover, we hope that the evidence presented in this paper upholds the importance of not overlooking the interactions that take place when the students set goals, since these interactions open up opportunities to promote or hinder the students’ volition and agency, on which their self-determination is based. In the current literature in the field, the importance of having conversations with students and actively involving them in their goal setting is acknowledged. Unfortunately, however, this is more easily said than done. Therefore, supporting educators in analysing and reflecting on their dialogic practices is important to reduce unnoticed oppressive educational interactions.