Analyzing Migration Management: On the Recruitment of Nurses to Germany

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Principles and Politics of Migration Management

3. Analyzing Migration Management: Recruitment of Nurses in Germany

3.1. The Demographization of the Care Crisis: Migration as a Solution Strategy

“The partners agree that, because of the substantial increase in the demand for skilled personnel in elderly care, not only must the domestic [sic] potential be more strongly promoted and tapped to secure a foundation of skilled staff, but the potential available in the EU labor market, as well as, at least in the mid to long term, qualified immigration from third countries, must also be fully utilized”.3

3.2. Categorization: Figures of Migration in the Care Sector

“We begin with simple personal care and making beds; the very easy stuff. When that’s covered, they have to document it. Because this is also an important part of the tools of the trade. Then we wait and see what their German is like, as it were”(Practical instructor/mentor (Ward A), Hospital 1)

“Because the young ones (nurses from Romania) often already have children and a family. (laughing) (…) Yes, they typically stay at home. (…) It’s clear; the two months here are without children. And that has to be clear from the outset because they cannot learn as much if a child is here.”(Placement officer 3, Hesse)

“There is this example—the question at the core of emotional intelligence – you are probably familiar with it: ‘A lollipop now or two lollipops an hour later.’ (…) And ultimately we want two lollipops; we offer two lollipops, but you have to wait six months before you get the lollipops; and this question is of a selective nature. Because there are people who cannot imagine this in the first place; they can’t think about such cycles; they don’t want to. Those are therefore not the right ones. And those who don’t want to do this won’t learn the language either. (…) We still explain it, but we also let it stand as a selective criterion. Because the person who is willing to muster emotional intelligence to this degree and say ‘I know it’s worth the investment’ is also a reliable worker in the long run.”(Placement officer 1, Hesse)

3.3. Change in Statehood: Privatization and Diversification of Migration Control in the Case of Nurses

“First, for our own needs. Then we became aware of how much work it actually involves and how much energy it consumes. And then we said, ‘Okay, plenty of others have the same problem that we have.’ And then we turned it into a business model.”(Director of an elderly-care facility, Hesse)

- Matching demand for skilled labor in Germany with the supply of skilled labor in EU countries in accordance with the principle of the free movement of labor within the EU (e.g., the Federal Employment Agency’s Foreign Placement Agency (Zentrale Auslands und Fachvermittlung), together with European Employment Services, organizes job fairs in other EU countries);

- Providing a systematic overview of the formal and organizational aspects involved in recruitment from third countries, which employers frequently perceive as representing substantial barriers, and making it available to a variety of actors (e.g., checklists for recruitment, language and skill-oriented preparation in the country of origin, application of residential and working permits in Germany; (Peters et al. 2016);

- Creating platforms for projects where common agreements can be made that extend to all participating organizations (e.g., in the context of the Hessian recruitment initiative, an agreement was reached defining the conditions under which recruits could continue attending language classes during their induction phase).

“We only make the offer; as an association, we’re only attempting to organize it as a service, so that the companies can do it. But how they do it in the end is simply up to them.”(Representative of an association of service providers, Hesse)

3.4. Technologies: Steering the Migration of Foreign-Trained Nurses

4. Discussion and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afentakis, Anja, and Tobias Maier. 2010. Projektionen des Personalbedarfs und-angebots in Pflegeberufen bis 2025. Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/WirtschaftStatistik/Gesundheitswesen/ProjektionPersonalbedarf112010.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (accessed on 16 February 2019).

- Altenried, Moritz, Manuela Bojadžijev, Leif Höfler, Sandro Mezzadra, and Mira Wallis. 2017. Politiken und Vermittlung mobiler Arbeit–ein Forschungsprojekt. In Logistische Grenzlandschaften: Das Regime mobiler Arbeit nach dem Sommer der Migration. Edited by Moritz Altenried, Manuela Bojadžijev, Leif Höfler, Sandro Mezzadra and Mira Wallis. Münster: UNRAST, pp. 15–141. [Google Scholar]

- Auth, Diana. 2017. Pflegearbeit in Zeiten der Ökonomisierung: Wandel von Care-Regimen in Großbritannien, Schweden und Deutschland. Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot. [Google Scholar]

- Balibar, Etienne. 2005. Difference, Otherness, Exclusion. Parallax 11: 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, Chris. 2003. Labour Flexibility and Regional Development: The Role of Labour Market Intermediaries. Regional Studies 37: 621–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, Ulrich, Jessica Erbe, Nadja Schmitz, Stefan Arnold, Robert Koch, Sandra Mundt, and Friederike Rausch-Berhie. 2019. Berufliche Anerkennung im Einwanderungsprozess – Stand und Herausforderungen bei der Antragstellung aus dem Ausland: Ergebnisse des BIBB-Anerkennungsmonitorings (Vorabfassung). Available online: https://www.bibb.de/dokumente/pdf/2019_01_15_a3.3_fbi_best_berufliche_anerkennung_einwanderungsprozess_1.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2019).

- Bhambra, Gurminder K. 2017. The current crisis of Europe: Refugees, colonialism, and the limits of cosmopolitanism. European Law Journal 23: 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bild am Sonntag. 2018. Drei Minister leisten den Pflege-Schwur. June 30. Available online: https://www.bild.de/bild-plus/politik/inland/altenpflege/hier-versprechen-drei-minister-das-sie-den-pflegenotstand-beenden-56170936 (accessed on 2 March 2019).

- Bludau, Heidi. 2015. Creating a transnational labor chain between Eastern Europe and the Middle East. A case study in healthcare. InterDisciplines. Journal of History and Sociology 6: 95–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonin, Holger, Grit Braeseke, and Angelika Ganserer. 2015. Internationale Fachkräfterekrutierung in der deutschen Pflegebranche: Chancen und Hemmnisse aus Sicht der Einrichtungen. Available online: https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/fileadmin/files/Projekte/28_Einwanderung_und_Vielfalt/Studie_IB_Internationale_Fachkraefterekrutierung_in_der_deutschen_Pflegebranche_2015.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Braeseke, Grit, Meiko Merda, Thomas K. Bauer, Sebastian Otten, Magdalena A. Stroka, and A. E. Talmann. 2013. Migration. Chancen für die Gewinnung von Fachkräften in der Pflegewirtschaft. Bundesgesundheitsblatt, Gesundheitsforschung, Gesundheitsschutz 56: 1119–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckel, Sonja. 2012. Managing Migration – Eine intersektionale Kapitalismusanalyse am Beispiel der Europäischen Migrationspolitik. Berliner Journal für Soziologie 22: 79–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesagentur für Arbeit. 2018a. Arbeitsmarktsituation im Pflegebereich. Available online: https://statistik.arbeitsagentur.de/Statischer-Content/Arbeitsmarktberichte/Berufe/generische-Publikationen/Altenpflege.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Bundesagentur für Arbeit. 2018b. Fachkräfteengpassanalyse Dezember 2018. Available online: https://statistik.arbeitsagentur.de/Statischer-Content/Arbeitsmarktberichte/Fachkraeftebedarf-Stellen/Fachkraefte/BA-FK-Engpassanalyse.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales. 2016. Sonderprogramm MobiPro-EU. Available online: https://www.bmas.de/DE/Themen/Arbeitsmarkt/Modellprogramme/mobi-pro-eu.html (accessed on 16 February 2019).

- Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend. 2012. Ausbildungs- und Qualifizierungsoffensive Altenpflege 2012–2015. Available online: https://www.bmfsfj.de/blob/77250/7289d3d306c8d157d282ae5883c6fd64/vereinbarungstext-ausbildungs-und-qualifizierungsoffensive-apltenpflege-data.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft. 2012. Chancen zur Gewinnung von Fachkräften in der Pflegewirtschaft. Available online: https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Studien/chancen-zur-gewinnung-von-fachkraeften-in-der-pflegewirtschaft.pdf;jsessionid=92AF259DA9D2B6BE17748D2D662156E6?__blob=publicationFile&v=10 (accessed on 3 March 2017).

- Bundesregierung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. 2018. Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Nicole Westig, Michael Theurer, Renata Alt, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der FDP. Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 19/5274. Available online: http://dipbt.bundestag.de/doc/btd/19/056/1905654.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Bundesregierung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. 2019. Entwurf eines Fachkräfteeinwanderungsgesetzes, vom Bundestag beschlossen am 07.06.2019. Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 19/8285. Available online: http://dip21.bundestag.de/dip21/btd/19/082/1908285.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2019).

- Çalışkan, Koray, and Michel Callon. 2010. Economization, part 2: A research programme for the study of markets. Economy and Society 39: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorus, Silke. 2013. Care-Ökonomie im Postfordismus: Perspektiven einer integralen Ökonomietheorie. Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot. [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, Sara. 2016. Converging logics? Managing migration and managing diversity. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42: 341–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, Sara, Irene Messinge, Theresa Schütze, and Gerd Valchars. 2017. Migrationsmanagement: Praktiken, Intentionen, Interventionen (Editorial). Journal für Entwicklungspolitik 33: 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dijstelbloem, Huub, and Dennis Broeders. 2015. Border surveillance, mobility management and the shaping of non-publics in Europe. European Journal of Social Theory 18: 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dünnwald, Stephan. 2010. Politiken der “freiwilligen” Rückführung. In Grenzregime: Diskurse, Praktiken, Institutionen in Europa. Edited by Sabine Hess and Bernd Kasparek. Berlin and Hamburg: Assoziation A, pp. 179–99. [Google Scholar]

- Düvell, Franck. 2002. Die Globalisierung des Migrationsregimes: Zur neuen Einwanderungspolitik in Europa. Berlin and Hamburg: Assoziation A. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrentraut, Oliver, Tobias Hackmann, Lisa Krämer, and Sabrina Schmutz. 2017. Zukunft der Pflegepolitik—Perspektiven, Handlungsoptionen und Politikempfehlungen. Available online: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/wiso/12140.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2019).

- Ette, Andreas, Stefan Rühl, and Lenore Sauer. 2012. Die Entwicklung der Zuwanderung hochqualifizierter Drittstaatsangehöriger nach Deutschland. Zeitschrift für Ausländerrecht und Ausländerpolitik 32: 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. 2019. European Professional Card. Available online: https://europa.eu/youreurope/citizens/work/professional-qualifications/european-professional-card/index_en.htm (accessed on 10 March 2019).

- Forschungsgruppe »Staatsprojekt Europa«, ed. 2014. Kämpfe um Migrationspolitik: Theorie, Methode und Analysen kritischer Europaforschung. Bielefeld: transcript. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, Martin, and Antoine Pécoud. 2010. 1 The Politics of International Migration Management. In The Politics of International Migration Management. Edited by Martin Geiger and Antoine Pécoud. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Georgi, Fabian. 2007. Migrationsmanagement in Europa: Eine kritische Studie am Beispiel des International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD). Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller. [Google Scholar]

- Georgi, Fabian, Nikolai Huke, and Jens Wissel. 2014. Fachkräftemangel, Lohndumping und Puzzle-Politik: Die europäische ‚Blue Card‘ als arbeitskraftpolitisches Projekt. In Kämpfe um Migrationspolitik: Theorie, Methode und Analysen kritischer Europaforschung. Edited by Forschungsgruppe »Staatsprojekt Europa«. Bielefeld: Transcript, pp. 209–25. [Google Scholar]

- Hämel, Kerstin, and Doris Schaeffer. 2013. Who cares? Fachkräftemangel in der Pflege. Zeitschrift für Sozialreform 59: 413–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedemann, Ulla, Lukas Worm, and Ingrid Artus. 2017. Mehr von uns ist besser für alle«: Dokumentation einer Veranstaltung zum Pflegestreik an der Charité. In Sorge-Kämpfe: Auseinandersetzungen um Arbeit in sozialen Dienstleistungen. Edited by Ingrid Artus, Peter Birke, Stefan Kerber-Clasen and Wolfgang Menz. Hamburg: VSA, pp. 116–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, Sabine, Lisa-Marie Heimeshoff, Stefanie Kron, Helen Schwenken, and Miriam Trzeciak. 2014. Einleitung. In Grenzregime II: Migration-Kontrolle-Wissen. Transnationale Perspektiven. Edited by Lisa-Marie Heimeshoff, Sabine Hess, Stefanie Kron, Helen Schwenken and Miriam Trzeciak. Berlin and Hamburg: Assoziation A, pp. 9–39. [Google Scholar]

- Hessisches Sozialministerium. 2013. Aus der Region Madrid in den Rheingau-Taunus: Spanische Fachkräfte unterstützen die Pflege. News release. Available online: https://www.hessen.de/presse/pressemitteilung/aus-der-region-madrid-den-rheingau-taunus-spanische-fachkraefte (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Jäger, Margarete, and Regina Wamper. 2017. Von der Willkommenskultur zur Notstandsstimmung: Der Fluchtdiskurs in deutschen Medien 2015 und 2016; Duisburger Institut für Sprach- und Sozialforschung. Available online: http://www.diss-duisburg.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/DISS-2017-Von-der-Willkommenskultur-zur-Notstandsstimmung.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2020).

- Kannankulam, John. 2014. Kräfteverhältnisse in der bundesdeutschen Migrationspolitik: Die Asyldebatte als Schlüsselereignis des schwerfälligen Wandels vom Gastarbeitsregime hin zu Managed Migration in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. In Kämpfe um Migrationspolitik: Theorie, Methode und Analysen kritischer Europaforschung. Edited by Forschungsgruppe »Staatsprojekt Europa«. Bielefeld: Transcript, pp. 93–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, Holger. 2014. Vom ‘restriktiven Außenseiter’ zum ‘liberalen Musterland’ – Der deutsche Politikwechsel in der Arbeitsmigrationspolitik. In Rapide Politikwechsel in der Bundesrepublik: Theoretischer Rahmen und empirische Befunde. Edited by Friedbert W. Rüb. Zeitschrift für Politik: Sonderband 6. Baden-Baden: Nomos, pp. 71–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kordes, Jan. 2019. Anwerbeprogramme in der Pflege: Migrationspolitiken als räumliche Bearbeitungsweise der Krise sozialer Reproduktion. PROKLA 49: 551–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawietz, Johanna, and Stefanie Visel. 2014. “Die examinierten Praktikanten”—Differenzkonstruktionen in der Anerkennung von ausländischen Pflegequalifikationen. In Prekarisierung transnationaler Carearbeit: Ambivalente Anerkennung. Edited by Johanna Krawietz and Stefanie Visel. Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot, pp. 82–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lagios, Thanasis, Vasia Lekka, and Grigoris Panoutsopoulos. 2018. Borders, Bodies and Narratives of Crisis in Europe. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Meissner, Fran. 2018. Legal status diversity: Regulating to control and everyday contingencies. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44: 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Menz, Georg. 2011. Neo-liberalism, Privatization and the Outsourcing of Migration Management: A Five-Country Comparison. Competition & Change 15: 116–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroşanu, Laura. 2016. Professional Bridges: Migrants’ Ties with Natives and Occupational Advancement. Sociology 50: 349–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourão Permoser, Julia. 2017. Redefining membership: Restrictive rights and categorisation in European Union migration policy. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43: 2536–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neues Deutschland. 2018. Politiker fordern Spurwechsel. August 17. Available online: https://www.neues-deutschland.de/artikel/1097678.einwanderungsgesetz-politiker-fordern-spurwechsel.html (accessed on 2 March 2019).

- Parusel, Bernd. 2010. Abschottungs- und Anwerbungsstrategien: EU-Institutionen und Arbeitsmigration. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Verena, Esther Hofmann, Grit Braeseke, Katja Keller, Gertrud Stöcker, Manfred Schneider, Karmen Ozvatic, Angela Siebold, and Elisa Siebold. 2016. Handlungsempfehlungen für die Fachkräftegewinnung in der Altenpflege. Auszug aus der Studie “Begleitung des Pilotprojekts Fachkräftegewinnung für die Pflegewirtschaft”. Available online: https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Studien/pilotprojekt-fachkraeftegewinnung.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=14 (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Prognos. 2012. Pflegelandschaft 2030: Eine Studie der Prognos AG im Auftrag der vbw-Vereinigung der Bayerischen Wirtschaft e.V. Available online: https://www.prognos.com/fileadmin/pdf/publikationsdatenbank/121000_Prognos_vbw_Pflegelandschaft_2030.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2017).

- Pütz, Robert, and Mathias Rodatz. 2013. Kommunale Integrations- und Vielfaltskonzepte im Neoliberalismus: Zur strategischen Steuerung von Integration in deutschen Großstädten. Geographische Zeitschrift 101: 166–83. [Google Scholar]

- Pütz, Robert, Maria Kontos, Christa Larsen, Sigrid Rand, and Minna-Kristiina Ruokonen-Engler, eds. 2019. Betriebliche Integration von Pflegefachkräften aus dem Ausland. Innenansichten zu Herausforderungen globalisierter Arbeitsmärkte. Available online: https://www.boeckler.de/pdf/p_study_hbs_416.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2019).

- Rand, Sigrid, Robert Pütz, and Christa Larsen. 2019. Die Herausbildung eines globalisierten Pflegearbeitsmarktes in Deutschland. In Betriebliche Integration von Pflegefachkräften aus dem Ausland. Innenansichten zu Herausforderungen globalisierter Arbeitsmärkte. Edited by Robert Pütz, Maria Kontos, Christa Larsen, Sigrid Rand and Minna-Kristiina Ruokonen-Engler. pp. 20–59. Available online: https://www.boeckler.de/pdf/p_study_hbs_416.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2019).

- Ratfisch, Philipp. 2015. Zwischen nützlichen und bedrohlichen Subjekten: Figuren der Migration im europäischen ‚Migrationsmanagement‘ am Beispiel des Stockholmer Programms. movements. Journal für kritische Migrations- und Grenzregimeforschung 1: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, Nikolas, and Peter Miller. 1992. Political Power beyond the State: Problematics of Government. The British Journal of Sociology 43: 173–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothgang, Heinz, Rolf Müller, Rainer Unger, Christian Weiß, and Annika Wolter. 2012. BARMER GEK Pflegereport 2012. Available online: https://www.barmer.de/blob/37026/cc127a3bf245e033dbdc9d20c938b07a/data/pdf-pflegereport-2012.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Schmitz, Nadja, and Stefan Winnige. 2019. Anerkennung ausländischer Berufsqualifikationen: Anträge aus dem Ausland im Spiegel der amtlichen Statistik: Ergebnisse des BIBB-Anerkennungsmonitorings (Vorabfassung). Available online: http://www.bibb.de/anerkennung-auslandsantraege (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Schultz, Susanne. 2016. Die zukünftige Nation. Demografisierung von Migrationspolitik und neue Konjunkturen des Rassismus. movements. Journal für kritische Migrations- und Grenzregimeforschung 2: 117–38. [Google Scholar]

- Schwiter, Karin, Christian Berndt, and Linda Schilling. 2014. Ein sorgender Markt: Wie transnationale Vermittlungsagenturen für Seniorenbetreuung Im/mobilität, Ethnizität und Geschlecht in Wert setzen. Geographische Zeitschrift 102: 212–31. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Sam. 2017. Venues and Filters in Managed Migration Policy: The Case of the United Kingdom. International Migration Review 51: 375–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, Ilka. 2014. Die Müh(l)en der staatlichen Anerkennung – Selektionsmechanismen der Umwandlung “ausländischer” in “deutsche” Pflegefachkräfte zwischen Berufsrecht und Anerkennungspraxis. In Prekarisierung transnationaler Carearbeit: Ambivalente Anerkennung. Edited by Johanna Krawietz and Stefanie Visel. Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot, pp. 56–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sontowski, Simon. 2017. Speed, timing and duration: Contested temporalities, techno-political controversies and the emergence of the EU’s smart border. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 27: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szent-Ivanyi, Timot. 2018. Anwerbeprogramme für Pfleger aus dem Ausland laufen schleppend. Hannoversche Allgemeine. November 15. Available online: http://www.haz.de/Nachrichten/Politik/Deutschland-Welt/Anwerbeprogramme-fuer-Pfleger-laufen-schleppend (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Tomei, Gabriele. 2016. Social Transformation, Subjectification, and Labour Migration: Theorizing the Heterogeneity of Migration Flows in the Current Italian Crisis. In An Anthology of Migration and Social Transformation. Edited by Anna Amelina, Kenneth Horvath and Bruno Meeus. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 167–81. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2006. Working Together for Health: The World Health Report 2006. Available online: http://www.who.int/whr/2006/whr06_en.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2016).

- Winker, Gabriele. 2015. Care Revolution: Schritte in eine solidarische Gesellschaft. Bielefeld: Transcript. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | While Germany is also a destination country for (informal) carers providing long-term care in private homes, this article focuses on qualified nursing professionals working in hospitals, elderly care homes and for mobile health care providers. |

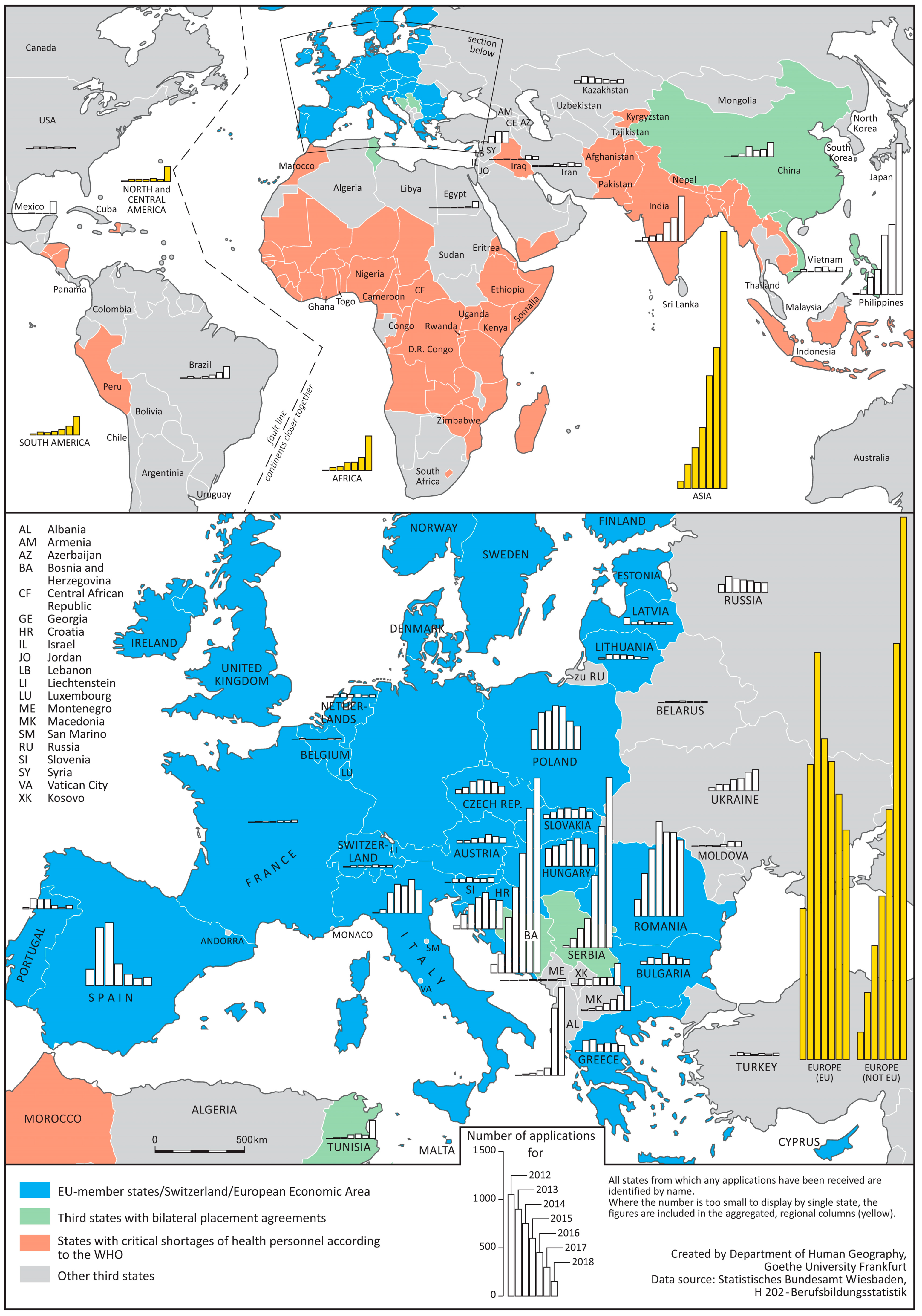

| 2 | The empirical research referenced in this paper took place between 2015 and 2017 during the project Betriebliche Integration von Pflegefachkräften aus dem Ausland (Organizational integration of foreign nurses) conducted by the Department of Human Geography, the Institut für Wirtschaft, Arbeit und Kultur (Institute for Economy, Labor, and Culture) and the Institut für Sozialforschung (Institute of Social Research) [all at Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main] and funded by the Hans Böckler Foundation. During this endeavor, which is only partially referenced here, 14 interviews with representatives of employers, recruitment agencies, vocational training institutes and qualification recognition authorities (among others), as well as 40 narrative interviews with migrant and autochthon nurses, were conducted. While we consider the perspectives of migrant nurses themselves to be essential, their voices and experiences are not part of this paper due to the focus on a specific political project of migration management. Their perspectives were reflected at length in other publications resulting from the project, which were published by Pütz et al. (2019). |

| 3 | All quotes were translated from German by the authors. |

| 4 | Statistically, it is not possible to differentiate between autonomous and recruited migration. Although autonomous migration originates primarily in countries that enjoy privileges arising from freedom of movement, these countries are also subject to private and public recruitment initiatives. Conversely, it is possible to immigrate from third countries in the absence of recruitment activities. However, this involves considerable effort. All statistical data regarding recognition proceedings refer to the country of issuance of the respective diploma, not the citizenship of the applicant—although the two are almost exclusively identical. |

| 5 | As a result of this lack of statistical data, the actual number of migrants seeking employment as nurses is larger than indicated here but cannot be determined precisely. Conversely, it is conceivable ― although presumably only in individual cases―that people whose credentials have been recognized upon applying from their home countries may ultimately abstain from migrating to Germany (Schmitz and Winnige 2019, p. 8). |

| 6 | Ratfisch deliberately employs the language used by the European Council. We prefer speaking of ‘illegalized migration’ (Düvell 2002, pp. 52–53) to indicate that humans as such cannot be illegal; only by means of legal intervention is the mode of ‘illegality’ constructed. |

| 7 | Liechtenstein, Norway, Iceland, and Switzerland are essentially treated on the same terms as EU member states. |

| 8 | The WHO list has been adopted into German law so that, according to § 38 of the Employment Regulation, the German Federal Employment Agency is the only eligible placement service provider for individuals from the 57 countries on that list. |

| 9 | In recent legislative procedures, the German parliament (Bundestag) resolved that, for the time being, the positive list would no longer be applied as an instrument of selection. The new law intends for immigration to be possible for all occupations in which professional or vocational credentials are recognized. |

| 10 | On the problems inherent in the contemporary practice to require candidates to apply from abroad, see Best et al. (2019). |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kordes, J.; Pütz, R.; Rand, S. Analyzing Migration Management: On the Recruitment of Nurses to Germany. Soc. Sci. 2020, 9, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9020019

Kordes J, Pütz R, Rand S. Analyzing Migration Management: On the Recruitment of Nurses to Germany. Social Sciences. 2020; 9(2):19. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9020019

Chicago/Turabian StyleKordes, Jan, Robert Pütz, and Sigrid Rand. 2020. "Analyzing Migration Management: On the Recruitment of Nurses to Germany" Social Sciences 9, no. 2: 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9020019

APA StyleKordes, J., Pütz, R., & Rand, S. (2020). Analyzing Migration Management: On the Recruitment of Nurses to Germany. Social Sciences, 9(2), 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci9020019