3.1. Who Are We Laughing at? Disability and Comedy

As Susanne Hamscha points out in her work on “Crip Humor,” laughter can be related to disability in two distinct ways. On the one hand, there is laughter directed at disability, making disabled people the object of ridicule and humiliation. On the other hand, there also exists laughter produced by people with disabilities that, according to Hamscha, often serves as “a coping mechanism to release stress, anxiety, and pain” (

Hamscha 2016, p. 349). This basic distinction has been theorized by disability studies scholars as the crucial difference between

disabling humor and

disability humor (

Albrecht 1999;

Reid et al. 2006). According to them, disabling humor refers to humor that denigrates people with disabilities based on their bodily difference (

Reid et al. 2006, p. 631). Disabling humor can best be understood if viewed under the framework of what scholars of humor theory, going back to the early writings on humor by Plato and Aristotle, have come to call the superiority theory of humor. As Eva Dadlez explains in her analysis of the moral implications of humor, superiority theories are based on the idea that humor is inherently connected to “ridicule and the enjoyment of one’s own superiority in pinpointing the foibles or weaknesses of another” (

Dadlez 2011, p. 2). In a similar vein, Jure Gantar explains in

The Pleasure of Fools that the very act of laughing is always, at least potentially, offensive, raising the very question of whether comedy can ever be ethical (

Gantar 2005, pp. 11–17).

As a humor that breaks with social hierarchies by centering disability, disability humor may serve as one possible way out of this ethical dilemma. Most often, disability humor is performed by disabled people themselves, freeing them from their traditionally passive roles as mere objects or side-kicks of disability-related jokes (

Reid et al. 2006, p. 631). Unlike disabling humor, I relate disability humor to a humor that is based on incongruity. Incongruity theories of humor, that go back to the writing of Schopenhauer, usually foreground the connection between aesthetics and humor, claiming that the object of amusement is the incongruous (

Kulka 2007, pp. 321–22). Thinking of disabling humor under the framework of incongruity, I agree with Garry Albrecht, who argues that disability humor is more than a coping mechanism (

Albrecht 1999, p. 72). Instead of making non-disabled people feel more comfortable, this form of humor is used to poke fun at absurd situations that disabled people experience in everyday life and therefore also used to make fun of non-disabled people, or at least of their reactions to disability. As Laurence Clark aptly remarks about his comedy: “As a disabled person, many bizarre things happen to you. If you don’t get a piss out of it, you are going mad” (qtd. in

Monaghan 2012). Disability humor thus, as most forms of humor, conveys group solidarity, an

us vs.

them, but it also challenges inherent value structures by placing experiences of disability in a greater socio-cultural context.

In order to fully understand these different forms of humor and how they relate to disability, the history of disability in popular culture has to be considered. Historically, there has been a significant shift in the ways popular culture trains its audiences to approach disability, from laughing at disability first in the freak show and later in the movies (see

Hamscha 2016, pp. 352–55), to years of conditioning people that staring and laughing at disability are not right after all. The latter had the ambivalent effect of turning away from difference, a refusal to see that builds the basis for cringe humor about disability. It is precisely because our societal codes of conduct tell us, as Rosemarie Garland Thomson reminds us, not to stare, that encounters with disability can make us uncomfortable (

Garland-Thomson 2009, p. 4). Cringe humor then builds on this uncomfortable feeling and uses it for its own purposes. Doing so, cringe humor makes us look at disability. More importantly, it makes us look at reactions to disability. Therefore, I claim that cringe humor participates in a cultural shift that moves notions of disability away from serving as mere insults and instead focuses on larger questions of social interaction.

In this regard, it seems interesting to note that the increasing presence of cringe that scholars like Melissa Dahl and Adam Kotsko attest for the last 15 years (

Dahl 2018;

Kotsko 2010) correlates with an increased presence of disability on television and in film (

GLAAD 2021;

Ellis et al. 2020). While I do not want to go as far as to propose a direct causal link between the two, comedy in general—because it is based on a transgression of norms and on the unexpected—frequently clings on to disability as a narrative device. With reference to a wider context of different genres and media, David Mitchell and Sharon Snyder have coined this practice “narrative prosthesis,” denoting the very reliance of many narratives on disability and their simultaneous failure to truly engage with experiences of disability (

Mitchell and Snyder 2000, p. 6). Referring to Mitchell and Snyder’s highly-acclaimed concept, Beth Haller and Amy Bree Becker conclude for the genre of comedy that “disability becomes the representational ‘crutch’ that props up the humor in many comedy narratives created by nondisabled people” (

Haller and Becker 2014, n. pag.).

In more recent years, following marginalized artists from a range of different groups, comedy’s very reliance on disability has, at least partly, provided disabled actors with roles. As Arab-American actor, comedian and disability activist Mayzoon Zayid aptly remarks in one of her stand-up performances: “It became clear to me that casting directors didn’t hire fluffy, ethnic, disabled people. They only hired perfect people. But there were exceptions to the rule. I grew up watching Whoopi Goldberg, Roseanne Barr, Ellen—and all these women had one thing in common: They were comedians. So I became a comic” (

TEDWomen 2013). At the same time that these female, Black, and queer comedians began to change the comedy scene on television, disabled comedians started to enjoy unprecedented success, albeit often on smaller stages. Following the disability movements and the emergence of disability studies in both the UK and the US, these comedians brought with them “the potential to revolutionize humor,” as Haller and Becker have enthusiastically argued. Yet, although comedy provides one of the few spaces where disabled actors are more frequently shown, their roles often remain marginal.

3.2. From Awkward Silences to Giving Disability a Voice

On television, disabled actors are most commonly hired for one or two episodes only (

Raynor and Hayward 2009). Although an appearance like that of Julie Fernandez on the British hit show

The Office can be said to contribute to the visibility of disabled actors on screen, it seems important to note that her character occupies only a minor role in the overall series. Quite similarly, the show’s U.S. adaptation that ran for an impressive total of nine seasons included the character of Billy Merchant, portrayed by the late Marcus A. York, for only four episodes (

The Office (U.S.) 2006–2010, S2E12; S2E22; S04E1–2; S05E22). Since the overall screentime given to these characters is rather limited, a close analysis of the scenes involving them seems particularly pertinent. The continuing underrepresentation of disability in British and American television makes appearances of disabled characters on screen especially relevant in terms of their cultural work (

Wegner 2019), perhaps also increasing the pressure on producers to deliver a scene that leaves little room for unwanted criticism later on. After all, shows like

The Office reach very large audiences within and outside the UK and the U.S. (

Turner Garrison 2011). Their global impact makes them relevant objects of study not only from an Anglo-American but also from a transnational perspective. In the following, I perform a close reading of one rather iconic “disability scene” that appears in the second season of the show’s British original.

In the second episode of season 2, a fire drill disrupts the usual happenings at the titular office. While the present characters are quick to evacuate the building, the show’s protagonist David Brent (Ricky Gervais) is seen to hold back Brenda (Julie Fernandez), an employee using a wheelchair, from exiting the building with two comparatively strong-looking co-workers. Together with Gareth Keenan (Mackenzie Crook), David takes on the task of assisting Brenda, declaring valiantly: “I’m going to get you out of here” (S02E02). In the next shot, David and Gareth are shown to carry Brenda down the stairs with much difficulty. Realizing that “this isn’t working, it’s too difficult,” David decides to leave Brenda in the middle of the staircase while ordering Gareth to follow him outside. Brenda’s suggestion to use the elevator together is denied by David and she is thus left alone, staring at the camera rather helplessly (see

Figure 1).

So, if we laugh, what are we laughing about in this very moment? I propose that, in this particular scene, we neither laugh at disability nor do we laugh with the disabled character. Instead, we are laughing at the protagonist, who tries to navigate the situation yet fails miserably. The disembodied camera makes it very difficult to identify with any of the characters. While our sympathy may lie with Brenda, the emphasis of the scene itself is that we neither want to be in her position nor do we want to be one of the two men. The mockumentary genre of the series engages viewers in a unique way, emphasizing their position as witnesses who are forced to watch what is happening without being able to intervene. Brenda’s look at the camera, and by extension at the audience, increases the scene’s potential to makes viewers cringe. The show uses her searching eyes quite self-reflexively, drawing attention to the fact that audience members unwillingly become complicit in David and Gareth’s actions by simply watching the events unfold. In this scene, it is not solely David and Gareth’s inappropriate behavior toward Brenda that may lead audiences to cringe but the mockumentary’s emphasis on the very act of watching and witnessing these indiscretions. Yet, although the scene primarily makes fun of David and Gareth and not of Brenda, the cultural work it performs seems rather ambivalent. Next to the specifics of the camera, this ambivalence is created through the silence at the end of the shot. As an effective stylistic choice, it is this very silence that increases the cringe-worthiness of the moment. As Julie Fernandez admitted in an interview: “I was saying to Stephen and Ricky, ‘oh please let me say something.’ And they were like ‘no it’s stronger if you stay silent.’ And it really was quite strong in staying silent. But, you know, the thing that scares me the most is that I‘ve actually had disabled people come up to me since then and say that this actual thing has happened to them and you just think ‘no, that’s not possible’” (qtd. in

Monaghan 2012).

Next to the effect of silence, the quote by Fernandez points to a second important aspect of the scene, namely the tension that is created between the fictional setting of the television series and the embodiment of the actor portraying Brenda. Due to the overall fictionality of the series and the conventions of the genre, this scene might be read as an exaggeration, allowing non-disabled audiences to find comfort in the fact that the situation that unfolds in front of them, although based on familiar feelings of awkwardness, is just a little too over the top to be true. Unfortunately, however, as Fernandez’ statement clarifies, this is not necessarily the case. I propose that for the reception of this scene it is decisive whether audience members are just too painfully familiar with the situation or whether they observe what’s happening from a safe distance, hoping that this will never happen to them.

The fact that David Brent acts particularly inappropriately indeed helps to create a distance that makes it safe to watch, cringe, and laugh at his behavior. After all, while some of his actions may, potentially, also happen to others, audience members can comfort themselves by assuming that they will most likely never behave as badly as David Brent does. While Jason Middleton argues that awkward moments occur “when an encounter feels too real: unscripted, unplanned, and, above all, occurring in person” (

Middleton 2014, p. 2), the protagonist’s exaggerated attributes and the series’ fictionality increase the scene’s cringe factor. Watching the scene, audience members are not truly “suffering,” as some scholars of cringe comedy have more generally suggested. Instead, the show uses vicarious embarrassment to such a high extent that the discomfort we feel at watching the characters also becomes the show’s greatest source of comfort—after all, audiences can constantly assure themselves that their own actions in real life are at least not as embarrassing as those of David and Gareth. However, those who use a wheelchair and thus may identify with Brenda—who quite tellingly does not seem to have a last name—are perhaps unable to distance themselves from the scene as easily as non-disabled audience members.

Let me now, in comparison, turn to the performances of Laurence Clark. On his official website, Clark describes himself as an “internationally-acclaimed comedian, writer and actor who has cerebral palsy.” (

Clark 2012a, n.pag.). Indeed, Clark is one of the most successful British comedians with a visible disability: He appeared on television in various capacities and has been a guest writer for

BBC Ouch,

The Independent, and

The Guardian. The magazine

Shortlist named Clark Britain’s “Funniest New Comedian” in 2007; a few years later, he came in second in the AmusedMoose Edinburgh Comedy Awards (ibid.). As well as being a successful solo performer, Clark also regularly performs with the comedy collective Abnormally Funny People, which was founded in 2005 (

Abnormally Funny People 2021). In his stand-up performances, Clark uses an unusual mixture of pre-recorded material and live performance, with the pre-recorded material taking up a majority of his stage time. The videos he introduces, and further comments on, show Clark in a real-life setting, most frequently out on the streets interacting with different passersby.

In one of his most famous pieces, Clark goes out to collect money for fake charities, each being more hideous than the last. Introducing the recording of this stunt to his live audiences, Clark explains that recently, he has received money from a stranger on the streets without asking for it. His personal account thereby mirrors that of several disabled activists, who openly criticize the media for providing limited images of visibly disabled people as either “beggar” or “Batman” and warn of the real-life implications these tropes frequently have (

Radtke 2003). With this sketch, Clark challenges the trope of the disabled beggar and provides both the unaware passersby in London and his audiences across the UK an opportunity to reflect on their (potential) reactions to visibly disabled people. His stunt starts with him sitting on the sidewalk of a street, holding up a bucket that reads in bold letters: “PAY OFF MY MORTGAGE” (

Clark 2011, 00:01:06). What follows are a number of interactions with people that give money to Clark despite him persisting that “no sir, you really don’t want to pay off my mortgage” (

Clark 2011, 00:01:21). Throughout his live performances, Clark shows the recordings of various fake charity causes, briefly introducing each before playing the recording. He amplifies the humorous effect of his stunt by showing increasingly ludicrous causes which he received money for. In his second-to-last video, Clark is shown to hold up a bucket that reads “KILL THE PUPPIES!” (

Clark 2011, 00:06:07), a cause that, as is shown, people are still willing to give him money for despite his warnings not to do so (see

Figure 2). It is only in his final video that Clark fails to collect money. Providing a clever twist at the end of the performance, he shows his unsuccessful attempt at collecting money to “top up Heather Mills [sic] £24.3 million settlement” (

Clark 2011, 00:07:59). With this final “charity case,” Clark does not only reference Mills’ much-discussed divorce from Paul McCartney but, by choosing the famous amputee model, he further counters the idea that disabled people are necessarily in need of financial support.

In Clark’s sketch, incongruity is used as a social corrective. Clark’s performance challenges the values of the dominant group while giving voice to those who are usually subordinated. The charity collection performance combines invective strategies, in that it shames the people who donate, with strategies of identification. Although Clark never addresses his audience directly, the videos he shows ultimately encourage audiences to ask themselves how they would have reacted to Clark’s presence on the street. Because his videos feature various passersby who embody different markers of identity with regard to their age, gender, and race, identification is made possible for a wide range of different audiences. Unlike in

The Office and other popular cringe comedies on television, it is not the white, non-disabled, heterosexual cisgender man who serves as the ultimate subject of cringe. Instead, Clark’s stunts illustrate that ableist perceptions are widespread and can lead to cringe-worthy behavior among most people. Yet, while identification with the passersby is therefore encouraged, audiences get to witness the situation from Clark’s perspective, which is enforced by the very fact that he introduces his reasons for each of his “social experiments” before playing the respective video clip. In a larger context, Teresa Milbrodt argues: “While disabled people are often positioned by society as helpless, spiteful, and/or lacking agency and control, by telling comic stories, individuals can position themselves on their own terms, and subvert dominant ideologies” (

Milbrodt 2018, n. pag.). Building on this argument, I propose that it is not only Clark’s function as a first-person narrator but also his very embodiment on the stage that increases this effect. As Reid, Stoughton, and Smith note, “[disabled people’s] stories

and presence onstage also counter prevalent ideas that disabled people are unhappy and long to be ‘normal’. Finally, they reveal that their lives are full, rich, and well worth living” (

Reid et al. 2006, p. 633; emphasis added). By joking and laughing on stage, Clark challenges dominant perceptions of disability and illustrates that it is neither a contradiction nor extraordinary to be disabled and live a fulfilling life.

Over the last years, Clark has come up with a range of different so-called “experiments” that he records and uses for his live performances. In 2012, he subverted the idea of what disabled comedian and activist Stella Young has famously called “inspiration porn” (

Young 2012, n.pag.) by stopping passersby on the street to tell them how inspiring they are to him. Among other things, Clark sits on the bottom of a set of stairs to congratulate everyone on their achievement of using the stairs: “How do you do that? That’s so inspiring” (

Clark 2012b, 00:00:45). In yet another stunt, Clark gives away free snacks to people who personally address him on the street. But although he sets up big signs, instructing people to talk to him (see

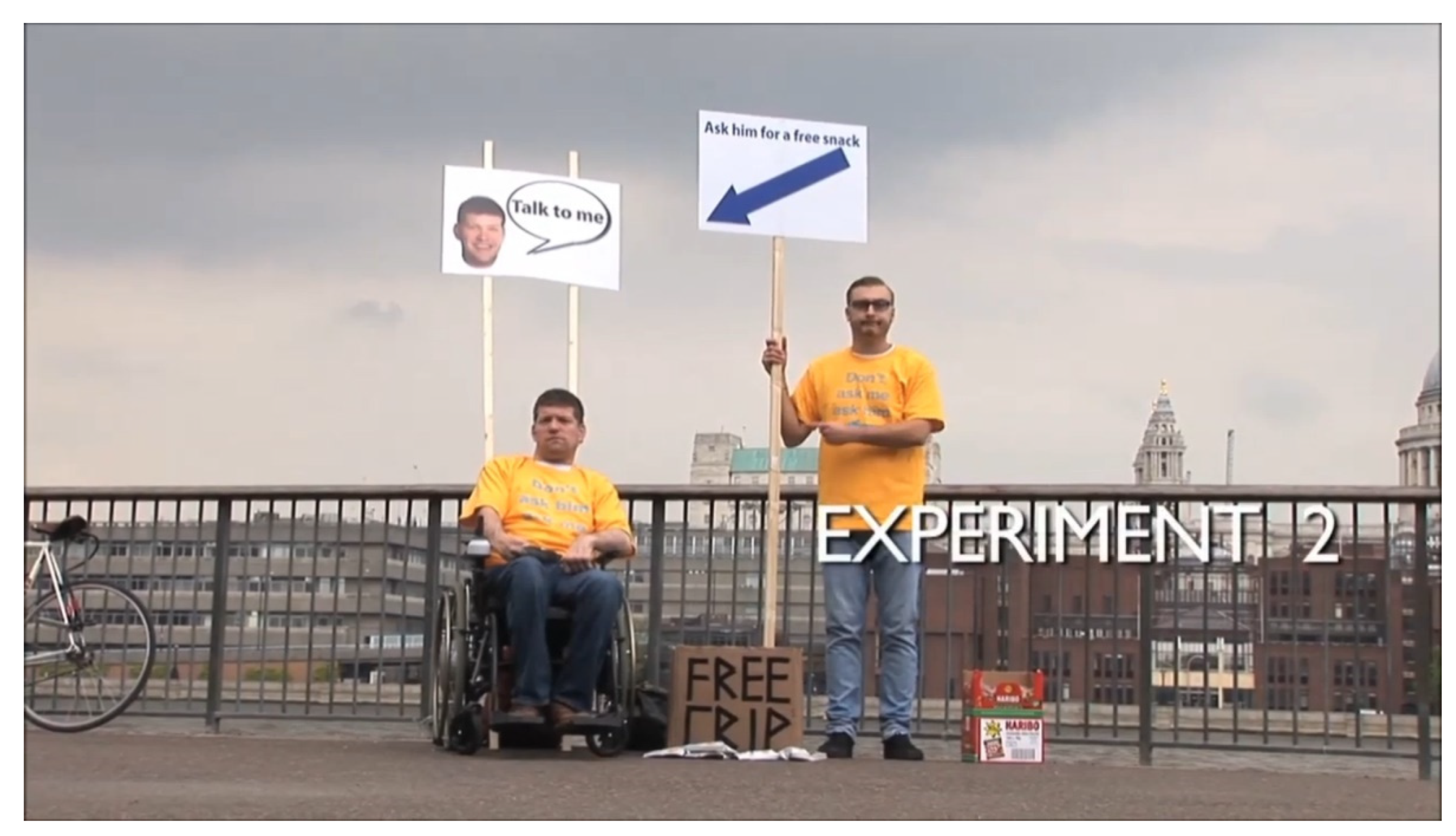

Figure 3), many passersby are shown to automatically walk up to his friend instead.

Clark’s friend “Hans,” a made-up character who speaks a fictional language, is repeatedly addressed and talked to while only a few people are shown to speak to Clark (

Clark 2014).

As with his charity buckets, Clark presents us with a variety of different reactions he receives on the street. Because his performances offer this sample of different reactions, audiences are again invited to recognize their own behavior among that of the various pedestrians. In all three sketches introduced in this paper, Clark playfully negotiates and criticizes the ways in which some people have (not) talked to him in the past.

Indeed, disabled comedians have long been practicing what some call “constructive humor.” Back in the 1990s, disabled comedian Fred Burns noted in the San Diego Union-Tribune that “when you’re disabled, unlike other comics, audiences don’t want to laugh at you. They’re taught all their lives not to make fun of handicapped people.

That was the challenge—to get them to laugh at their concepts of people who are disabled” (qtd. in Haller and Becker; emphais added). In the context of disability representation, Bruce Baum defines constructive humor as a “humor arising from their experiences as disabled people that teach the audiences about their lives” (

Baum 1998, p. 4). However, as a closer look at the examples provided above reveals, Clark’s performances do not merely teach audiences something about the performer’s life. Instead, Clark uses cringe humor to teach audiences about their own lives and their participation in the social construction of disability. Clark’s performances, I argue, are as much about him living with a disability as they are about other people disabling him. Yet, instead of only showing one extreme reaction, that would create an ultimate moment of cringe as witnessed in the previous scene of

The Office, Clark’s performances emphasize the common practice behind some of the pedestrians’ reactions.

Doing so, the unusual format of his stand-up shows creates enough distance to reduce anxiety on the part of the audience. The mediated form of his interactions with non-disabled people makes it possible for audience members to feel embarrassed for the other—and for oneself—without making it unbearable to sit through Clark’s performance. His use of videos skillfully mediates his experiences, keeping his live comedy shows from becoming reproachful. Instead of engaging the audience more directly, for instance by asking audience members to come up on stage with him, the format of the video helps to create a safe space for audiences to ponder questions of disablement. At the same time, Clark’s performances also offer points of identification for disabled audience members who may or may not have experienced similar situations to those that Clark captures with his videos.

All in all, Clark’s performances help to move disability away from being the mere humorous device which it is still frequently used as in television comedies. To be fair, contemporary cringe comedies like The Office do not employ disabling humor; they mostly refrain from participating in older traditions of explicitly denigrating people with disabilities. At the same time, The Office’s portrayal of disability neither qualifies as disability humor, as Brenda remains mostly silent throughout her brief appearances. Compared to The Office, Clark’s use of cringe humor is less ambiguous and more didactic in nature. Using a more personal approach to storytelling, Clark’s comedy is clearly situated within the context of disability activism and disability humor. His performances make obvious why people should, at least according to him, be embarrassed by certain actions and reactions to disability. Doing so, he also draws attention to situations that, at first sight, may seem less loaded. While The Office allows audiences to lean back and enjoy a firework of awkwardness and embarrassment, the live performances of Laurence Clark make it more difficult, I argue, to simply watch the show without reflecting on one’s own behavior and positionality.

While embarrassment and shame are commonly thought of as hindering or at least being counterproductive to processes of learning, Clark’s work of narrating and displaying cringe-worthy moments is both funny and educational. Among other things, Clark’s performances (1) encourage audiences to reflect on their own experiences and actions, (2) question notions of disability as pitiful and inspirational, and (3) offer a subjective view on what it means to be disabled. Doing so, Clark’s performances indeed seem to fulfill many of the aims that disability studies has set for itself in a more formally educational context.