Sapiens Dominabitur Astris: A Diachronic Survey of a Ubiquitous Astrological Phrase

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Sapiens Dominabitur Astris: Origins and Historiography of the Phrase

3. Scholastic Wise Men: The Thomistic Synthesis and the Orthodox Christian

The wise man was one in control of his baser instincts. Here, free will was important not just as a necessity so humans could freely choose to follow Christ but also to preserve sin as a choice between good and evil, as it did not have the “quality of a moral evil” unless it was entered into “voluntarily” (Aquinas [1266–1273] 1948, 2.74.1–2.75.1, pp. 919–20 and 927–28).16The majority of men follow their passions, which are movements of the sensitive appetite, in which movements of the heavenly bodies can cooperate: but few are wise enough to resist these passions. Consequently, astrologers are able to foretell the truth in the majority of cases, especially in a general way. But not in particular cases; for nothing prevents man resisting his passions by his free-will. Wherefore the astrologers themselves are wont to say that ‘the wise man is master of the stars’, forasmuch as, to wit, he conquers his passions.

4. The Reign of the Thomist Interpretation, ca. 1280–1500

5. Early Modern Fracturing 1: Humanist Political Reinterpretations

Machiavelli simply struck for middle ground between the role of fortune and free will in human affairs. He argued that acting in accordance with nature depended less on astrological influence and more on the “times and the temperament” (ibid.). Unlike the Thomist interpretation, the Machiavellian combined a rejection of both astrological determinism and Christian free will—at least as defined by the scholastics—as well as an acknowledgment that humanity was inclined by the natural forces of “temperament and humor” (ibid.). Even though he changed the influencing factors, he maintained a soft determinism by refusing to consider any man wise enough to be in full control of his destiny. Most men, he claimed, were not wise but “shortsighted” and could not “command the nature” of the stars or fate. Rather, he argued, “fortune varies and commands men and holds them under her yoke” (Machiavelli 2019, p. 33). According to Ernst Cassirer, Machiavelli defined a wise man as someone more than learned or even politically perceptive, and instead as someone who possessed both the power and the will to apply his limited wisdom for his own personal gain. In what Cassirer called the “secularization of the symbol of Fortune,” Machiavelli aptly compared the astrologers’ power to use their knowledge to determine potential fortunes with the will of intellectually and socially powerful men to change their political destinies (Cassirer 1947, p. 160; Cassirer 1963, esp. pp. 64–66, 84–91, 109–12).it is not unknown to me how many men have had, and still have, the opinion that the affairs of the world are in such wise governed by fortune and by God that men with their wisdom cannot direct them and that no one can even help them; and because of this they would have us believe that it is not necessary to labour much in affairs, but to let chance govern them. This opinion has been more credited in our times because of the great changes in affairs which have been seen, and may still be seen, every day, beyond all human conjecture. Sometimes pondering over this, I am in some degree inclined to their opinion. Nevertheless, not to extinguish our free will, I hold it to be true that Fortune is the arbiter of one-half of our actions, but that she still leaves us to direct the other half, or perhaps a little less.

6. Early Modern Fracturing 2: The Protestant “Fleshly Man” and Everyday Astrology

7. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The phrase can also be found in other forms, including “sapiens dominatur astris,” “vir sapiens dominabitur astris,” “vir bonum dominabitur astris,” “vir mediante Deo sapiens dominabitur astris,” or “homo sapiens dominabitur astris.” Though the Latin verb dominor takes the third person singular future passive indicative ending “-abitur,” it is a deponent verb which is translated as active. Both historical commentators on astrology and modern historians addressing the phrase have noted these potential ambiguities, misunderstandings, and double meanings. Although the versions of the phrase without “vir” can be interpreted as either a male or female wise person, the historical sources who used it almost universally referred to the wise “man.” I have, somewhat reluctantly, retained this translation throughout. |

| 2 | Charting every use of this phrase would be a worthwhile though extraordinarily difficult goal. Digital databases of manuscripts and printed works have been helpful, but even these are not comprehensive. For example, a phrase search at the database aggregator and finding aid for manuscript documents between 1000–1500, www.manuscriptsonline.org (accessed on 31 August 2021), yields 113 instances across nine databases. A search of printed texts using optical capture recognition from 1500–1700 at the Münchener DigitalisierungsZentrum Digitale Bibliotek (https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/, accessed on 9 October 2021) returns 323 documents and nearly 300 more from 1700 to the present. Other digital manuscript databases at which once can find unique documents containing this phrase include https://fbc.pionier.net/pl/ (accessed on 9 October 2021), https://opacplus.bsb-muenchen.de/metaopac/start.do (accessed on 9 October 2021), https://europeana.eu (accessed on 9 October 2021), and https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/library (accessed on 9 October), among others. |

| 3 | To some degree, astral knowledge has begun to replace “astral sciences,” which emerged out of archaeological and anthropological investigations of the ancient world (see e.g., Hunger and Pingree 1999), as a more all-encompassing term for these beliefs and practices. For the most part, I have maintained the use of the word “astrology” throughout this essay, largely because this is the term my historical figures use. |

| 4 | |

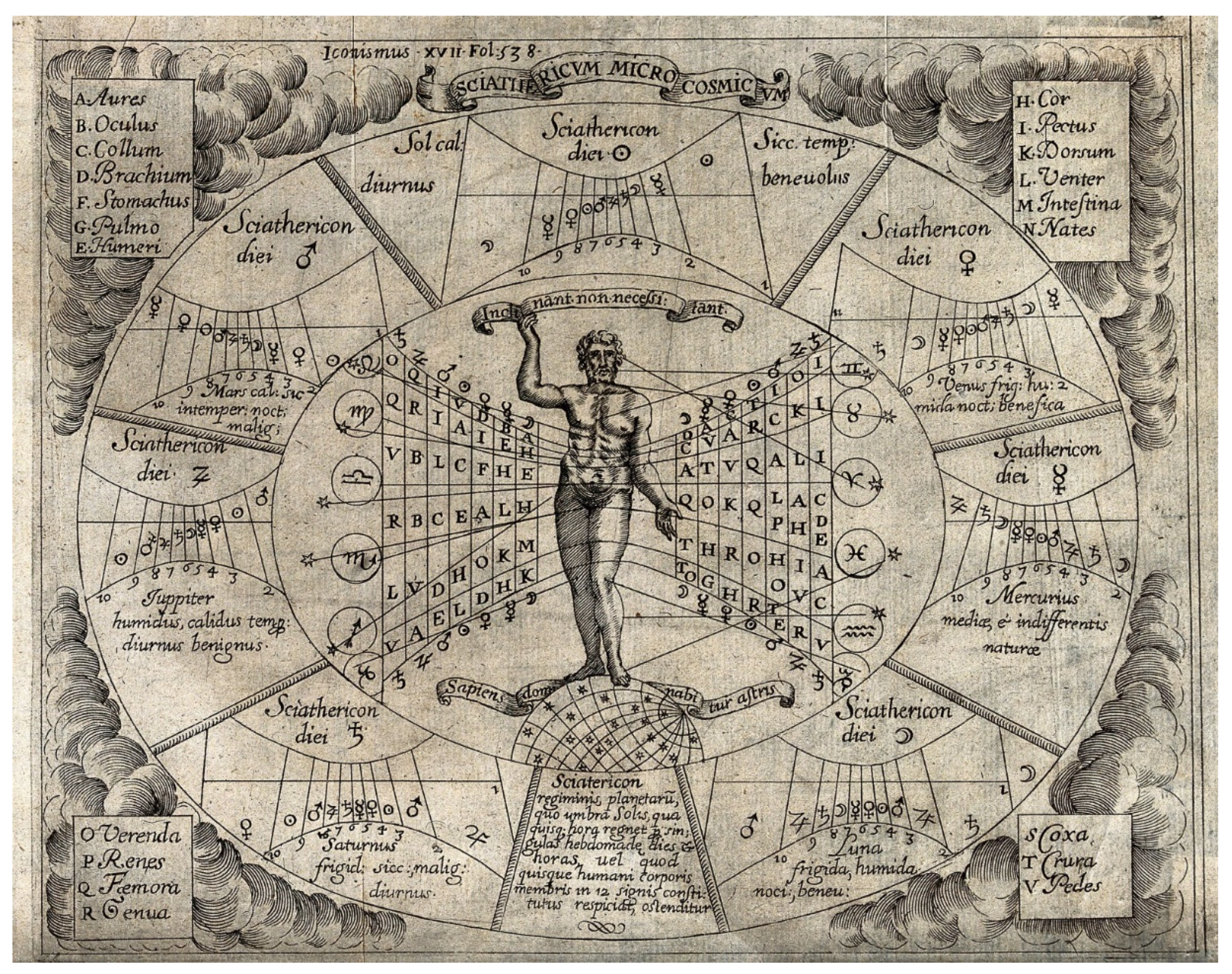

| 5 | Tester notes at least four Latin translations of the Centiloquium in the 1130s and 1140s: by Hugh of Santalla in 1136, John of Seville in 1136, Plato of Tivoli in 1138, and John of Spain in 1140. The Introductorium maius in astrologiam was translated into Latin by John of Seville in 1133 and Herman of Carinthia in 1140. |

| 6 | Boudet (2020, p. 283) cites Maria Mavroudi’s contribution “The Byzantine Reception of Ptolemy’s Karpos and the Origins of the Text” (Karpos being the Greek title for the Latin Centiloquium) to the proceedings of the conference Ptolemy’s Science of the Stars in the Middle Ages, London, The Warburg Institute, 5–7 November 2015, but I have been unable to locate a published version of this paper. See conference proceedings schedule here: https://ptolemaeus.badw.de/news/9 (accessed on 31 August 2021). On the Centiloquium’s possible Syriac origins, see Nau (1931–1932). |

| 7 | Edward Grant, the modern editor of Tempier’s condemnations, notes that his English translation comes from the Latin version found in Chartularium Universitatis Parisiensis, Vol. I, ed. H. Denifle and E. Chatelain (Paris, 1889–1897), pp. 543–55. |

| 8 | The fact that Albertus Magnus and Berthold von Regensburg are two of the earliest possibilities is no coincidence. There is some historical evidence for contact between them: Albertus served as the Bishop of Regensburg from 1260 to 1263 and in his final year Pope Urban IV directed Berthold, who had been on a preaching tour of central Europe, to support Albertus in preaching a crusade against the heretical Waldensian sect. Moreover, one Latin letter survives by Albertus responding to a question by Berthold (Gottschall 2013, p. 753; Tester 1987, p. 178). In his Opus Majus, Bacon cited pseudo-Ptolemy’s Centiloquium and wrote: “God has not imposed necessity on human actions … therefore, man can take thought beforehand for all his advantages, and remove obstacles, if he is skillful in this science.” Berthold of Regensburg wrote that “God…gave…powers to the stars, that they have power over all things, except power over one thing. It is man’s free will: over that no man has any authority except himself.” |

| 9 | |

| 10 | In these instances, Albertus rendered the phrase as “sapiens dominatur astris.” On these uses, see Zambelli (1992, p. 71, 167 n.46–7). De natura locorum is undated, but Zambelli argues that it appeared no earlier than 1259. |

| 11 | The Speculum Astronomiae was written anonymously around 1260 and was deliberately left untitled. Its first attribution to Albertus did not come until William Pasgregno in 1339 (Paravicini Bagliani 2001), which Hackett (2013, pp. 445–46) suggests as the origin of the theory of Albertus’s authorship. Roger Bacon, Campanus of Novara, and Richard de Fournival have all been suggested as potential authors (Mandonnet 1910; Roy 2000; Burnett 2018; Weill-Parot 2018). |

| 12 | For more on this context, see Zambelli (1992, p. 259). |

| 13 | |

| 14 | On the rejection of the stars’ “necessitation,” see Albertus Magnus De quatuor coaequevis 3.18.1 and Super ethica 50.3.1.8. |

| 15 | For more on this use, see Zambelli (1992, p. 71). |

| 16 | This also appears in Thomas Aquinas De malo 2.2.238a. On sin and free will in this astrological context, see Boruchoff (2009, p. 377). |

| 17 | On the “indirect” affects of the stars, see Tester (1987, p. 181), Campion (2009, p. 50), and Christopoulos (2010, p. 393). |

| 18 | On Aquinas’s use of this companion phrase, see his Summa Theologica 1.111.2, 1.115.4, 2.9.4–5, and 2.95.4; Summa contra gentiles 3.84 and 3.93; De verdate 5.9–10; De anima 31.4; and Compendium theologiae 1.127–28. This also sometimes appeared in later versions as “inclanant non necessitant.” |

| 19 | Jean de Meun alone composed the sections that reference astrology. |

| 20 | Wedel quotes Benvenuto da Imola Commentum 1.520. |

| 21 | Oresme wrote not in Latin but in Middle French. He rendered the phrase as “un homme sage seignourie sur les etoilles.” |

| 22 | Konarska-Zimnicka cites Stanisław of Skarbimierz, Stanisław of Zawada, Jakub of Paradyż, Tomasz of Strzempin, and Benedict Hesse among those who cited it negatively, and Jan of Głogów as one who cited it in favor of astrology. |

| 23 | |

| 24 | |

| 25 | Mangolt and Schöner borrowed this directly from Lutheran reformer, theologian, and astrological supporter Philipp Melanchthon. |

| 26 | Barnes quotes Hieronymus Wilhelm, Practica 1571, in Verzeichnis der im deutchen Sprachbereich erscheinenen Drucke des 16. Jahrhunderts, W 3093. I have been unable to examine this document myself. |

| 27 | Barnes quotes Christoph Stathamion, Practica 1563, in Verzeichnis der im deutchen Sprachbereich erscheinenen Drucke des 16. Jahrhunderts, S 8653, 1–2. I have been unable to examine this document myself. |

| 28 | Based on a phrase search at the database Early English Books Online (https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebogroup/, accessed on 31 August 2021), there are 105 instances across 94 published works. Of the 94, 75 come from 1620 or later. Fittingly, the earliest comes from an edition of Albertus Magnus’s Secreta mulierum et virorum from 1483. |

| 29 | Though most historians have long since jettisoned the idea that the rise of modern science alone led to the decline of astrology (along with alchemy, magic, witchcraft, and the “occult” more generally), the process still is not well understood. Some, like Vermij and Hirai (2017), have suggested that it was an unsystematic demise in fits and starts that transformed, displaced, fractured, and otherwise marginalized astrology from the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries. Others, like Willis and Curry (2004), Bruno Latour (1993), and Jason Ā. Josephson-Storm (2017) have argued that historians should disregard the notion of “decline” and “disenchantment” altogether and simply accept that astrology has never really gone away. |

| 30 | See e.g., “New Logo of Ukraine’s Defense Intelligence Makes Russian Officials Lose Temper,” Publica Aici Sunt Ştirile, 30 October 2016, https://en.publika.md/new-logo-of-ukraines-defense-intelligence-makes-russian-officials-lose-temper_2629975.html (accessed on 31 August 2021). |

References

- Ackerman Smoller, Laura. 1994. History, Prophecy, and the Stars: The Christian Astrology of Pierre d’Ailly, 1350–1420. Princeton: University of Princeton Press. [Google Scholar]

- Akopyan, Ovanes. 2021. Introduction: Not Simple Twists of Fate. In Fate and Fortune in European Thought, ca. 1400–1650. Edited by Ovanes Akopyan. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Albertus. 1992. Speculum Astronomiae. In The Speculum Astronomiae and Its Enigma: Astrology, Theology, and Science in Albertus Magnus and his Contemporaries. Translated by Charles Burnett, Kristen Lippincott, David Pingree, and Paola Zambelli. Edited by Paola Zambelli. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 203–73. First published ca. 1260. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, John. 1659. Judicial Astrologers Totally Routed and Their Pretence to Scripture, Reason & Experience Briefly, Yet Clearly and Fully Answered, or, A Brief Discourse, Wherein Is Clearly Manifested That Divining by the Stars Hath No Solid Foundation…. London: John Allen. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez de la Granja, María, ed. 2008. Fixed Expressions in Cross-Linguistic Perspective: A Multilingual and Multidisciplinary Approach. Hamburg: Verlag Dr. Krovač. [Google Scholar]

- Aquinas, Thomas. 1928. Summa contra gentiles. In The Summa Contra Gentiles of St. Thomas Aquinas. Translated and Edited by the Fathers of the English Dominican Province. London: Burns Oates and Washburn. First published 1259–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Aquinas, Thomas. 1948. Summa Theologica. 5 vols, Translated by Fathers of the English Dominican Province. New York: Benzinger Brothers. First published 1266–1273. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon, Roger. 1961. Opus Majus. 2 vols, Translated by Robert Belle Burke. New York: Russell and Russell, Inc. First published 1267. [Google Scholar]

- Bacon, Francis. 2000. The Oxford Francis Bacon, Vol. 4: The Advancement of Learning. Edited by Michael Kiernan. Oxford: Clarendon Press. First published 1605. [Google Scholar]

- Bamborough, John Bernard, and John Christopher Eade. 1981. Robert Burton’s Astrological Notebooks. Review of English Studies 32: 267–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, Robin. 2016. Astrology and Reformation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barolini, Teodolinda. 2014. Contemporaries Who Found Heterodoxy in Dante, Featuring (But Not Exclusively) Cecco d’Ascoli. In Dante and Heterodoxy: The Temptations of 13th-Century Radical Thought. Edited by Maria Luisa Ardizzone. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 259–75. [Google Scholar]

- Boruchoff, David A. 2009. Free Will, the Picaresque, and the Exemplarity of Cervates’s Novelas Ejemplares. Modern Language Notes 124: 372–403. [Google Scholar]

- Boudet, Jean-Patrice. 2013. Ptolémée dans l’Occident médiéval: Roi, savant et philosophe. Micrologus 21: 193–217. [Google Scholar]

- Boudet, Jean-Patrice. 2014. Astrology between Rational Science and Divine Inspiration. The Pseudo-Ptolemy’s Centiloquium. In Dialogues among Books in Medieval Western Magic and Divination. Edited by Stefano Rapisarda and Erik Niblaeus. Florence: SISMEL, Edizioni del Galluzzo, pp. 47–73. [Google Scholar]

- Boudet, Jean-Patrice. 2020. The Medieval Latin Versions of Pseudo-Ptolemy’s Centiloquium: A Survey. In Ptolemy’s Science of the Stars in the Middle Ages. Edited by David Juste, Benno van Dahlen, Dag Nicolaus Hasse and Charles Burnett. Turnout: Brepols, pp. 283–304. [Google Scholar]

- Brentjes, Sonja, and Dagmar Schäfer. 2020. Visualizations of the Heavens before 1700 as a Concern of the History of Science, Medicine, and Technology. NTM Zeitschrift für Geschichte der Wissenschaften, Technik, und Medizin 28: 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, Charles. 2018. Richard de Fournival and the Speculum astronomiae. In Richard de Fournival et les sciences au XIIIe siècle. Edited by Joëlle Ducos and Christopher Lucken. Florence: SISMEL, pp. 339–48. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, Charles, and Dorian Geisler Greenbaum, eds. 2015. From Māshā’allāh to Kepler: Theory and Practice in Medieval and Renaissance Astrology. Ceredigion: Sophia Centre Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cadden, Joan. 1997. Charles V, Nicole Oresme, and Christine de Pizan. In Texts and Contexts in Ancient and Medieval Science. Edited by Edith Sylla and Michael McVaugh. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, pp. 208–44. [Google Scholar]

- Calvin, John. 1845. Institutes of the Christian Religion. Translated and Edited by Henry Beveridge. Edinburgh: Calvin Translation Society. First published 1536. [Google Scholar]

- Campion, Nicholas. 2009. A History of Western Astrology, Vol. 2: The Medieval and Modern Worlds. London: Continuum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Capp, Bernard S. 1979. Astrology and the Popular Press: English Almanacs, 1500–1800. London: Faber and Faber. [Google Scholar]

- Caroti, Stafano. 1987a. Melanchthon’s Astrology. In “Astrologi hallucinati”: Stars and the End of the World in Luther’s Time. Edited by Paola Zambelli. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 109–21. [Google Scholar]

- Caroti, Stafano. 1987b. Nicole Oresme’s Polemic against Astrology in His ‘Quodlibeta’. In Astrology, Science, and Society. Edited by Patrick Curry. London: Boydell Press, pp. 75–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cassirer, Ernst. 1947. The Myth of the State. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cassirer, Ernst. 1963. The Individual and the Cosmos in Renaissance Philosophy. Translated and Edited by Mario Domandi. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chamber, John. 1601. A Treatise Against Judicial Astrologie Dedicated to the Right Honorable Sir Thomas Egerton Knight, Lord Keeper of the Great Seale, and One of her Majesties Most Honorable Privie Councell…. London: John Harison. [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos, John. 2010. By «Your Own Careful Attention and the Care of Doctors and Astrologers»: Marsilio Ficino’s Medical Astrology and Its Thomist Context. Bruniana & Campanelliana 16: 389–404. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane, Rexmond C. 1958. Francis Bacon and the Architect of Fortune. Studies in the Renaissance 5: 176–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coopland, George William. 1952. Nicole Oresme and the Astrologers: A Study of His Livre de Divinacions. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Curry, Patrick. 2005. The Historiography of Astrology: A Diagnosis and a Prescription. In Horoscopes and History. Edited by Kocku von Stuckrad, Günther Oestmann and H. Darrel Rutkin. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, pp. 261–74. [Google Scholar]

- d’Ailly, Pierre. 1490. Concordantia astronomie cum theologia. Concordantia astronomie cum hystorica narration. Et elucidarium duorum precedentium. Augsburg: Erhard Ratdolt. [Google Scholar]

- d’Ascoli, Cecco. 1820. L’acerba. Venice: F. Andreola. First published 1327. [Google Scholar]

- da Legnano, Giovanni. 1917. Tractatus de Bello, de Represaliis et de Duello. Edited by Thomas Erskine Holland. Translated by James Leslie Bierly. Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published c. 1390. [Google Scholar]

- da Siena, Bernardino. 1880. Le prediche volgari dette nella piazza del campo l’anno 1427, vol. 1. Edited by Luciano Bianchi. Siena: Tip. Edit, all’inseg. di S. Bernardino. [Google Scholar]

- Dante. 1961a. Inferno. The Divine Comedy 1: Inferno. Translated and Edited by John D. Sinclair. Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published ca. 1308–1320. [Google Scholar]

- Dante. 1961b. Purgatorio. The Divine Comedy 2: Purgatorio. Translated and Edited by John D. Sinclair. Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published ca. 1308–1320. [Google Scholar]

- de Lorris, Guillaume, and Jean de Meun. 1971. Roman de la Rose. Translated by Charles Dahlberg. Princeton: Princeton University Press. First published ca. 1230–1275. [Google Scholar]

- Erasmus, Desiderius. 1524. De libero arbitrio diatribe sive collation. Basel: Joannem Beb. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzherbert, Thomas. 1606. The First Part of a Treatise Concerning Policy, and Religion Wherein the Infirmitie of Humane Wit Is Amply Declared, with the Necessitie of Gods Grace, and True Religion for the Perfection of Policy…. Douai: Laurence Kellam. [Google Scholar]

- Flint, Valerie I. J. 1991. The Rise of Magic in the Early Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaguin, Robert. 1904. Epistolae et Orations. Edited by Louis Thuasne. Paris: Bouillon. [Google Scholar]

- Garin, Eugenio. 1982. Astrology in the Renaissance: The Zodiac of Life. Translated by Carolyn Jackson, and June Allen. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gottschall, Dagmar. 2013. Albert’s Contributions to or Influence on Vernacular Literatures. In A Companion to Albert the Great: Theology, Philosophy, and the Sciences. Edited by Irven M. Resnick. Leiden: Brill, pp. 725–57. [Google Scholar]

- Granger, Sylviane, and Fanny Meunier, eds. 2008. Phraseology: An Interdisciplinary Perspective. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Edward. 1979. The Condemnation of 1277, God’s Absolute Power, and Physical Thought in the Later Middle Ages. Viator 10: 211–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, Edward. 1982. The Effect of the Condemnation of 1277. In The Cambridge History of Later Medieval Philosophy. Edited by Norman Kretzman, Anthony Kenny and Jan Pinborg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 537–39. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Edward. 1996. The Foundations of Modern Science in the Middle Ages: Their Religious, Institutional, and Intellectual Contexts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, Jeremiah. 2000. Aristotle, Astrologia, and the Controversy at the University of Paris. In Learning Institutionalized: Teaching in the Medieval University. Edited by John van Engen. Notre Dame: Notre Dame University Press, pp. 69–110. [Google Scholar]

- Hackett, Jeremiah. 2013. Albert the Great and the Speculum astronomiae: The State of Research at the Beginning of the 21st Century. In A Companion to Albert the Great: Theology, Philosophy, and the Sciences. Edited by Irven M. Resnick. Leiden: Brill, pp. 437–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix, Scott D. 2020. Albert the Great and Rational Astrology. Religions 11: 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger, Hermann, and David Pingree. 1999. Astral Sciences in Mesopotamia. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, Michael. 2020. The Decline of Magic: Britain in the Enlightenment. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Phebe. 2020. Astrology, Almanacs, and the Early Modern English Calendar. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Josephson-Storm, Jason Ā. 2017. The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kieckhefer, Richard. 2000. Magic in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- King, Henry. 1628. An Exposition upon the Lords Prayer Delivered in Certaine Sermons, in the Cathedrall Church of S. Paul. By Henry King Archdeacon of Colchester, and Residentiary of the Same Church. London: John Hauiland. [Google Scholar]

- Kircher, Athanasius. 1646. Ars magna lucis et umbrae. Rome: Hermanni Scheus. [Google Scholar]

- Kircher, Athanasius. 1665. Mundus Subterraneus. Amsterdam: Joannem Janssonium & Elizeum Weyerstraten. [Google Scholar]

- Kléber Monod, Paul. 2013. Solomon’s Secret Arts: The Occult in the Age of Enlightenment. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Konarska-Zimnicka, Sylwia. 2011. Astrologia Licita? Astrologia Illicita? The Perception of Astrology at Kraków University in the Fifteenth Century. Culture and Cosmos: A Journal of the History of Astrology and Cultural Astronomy 15: 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Konarska-Zimnicka, Sylwia. 2017. Why Was Astrology Criticised in the Middle Ages? Contribution to Further Research (On the Basis of Selected Treatises of Professors of the University of Krakow in the Fifteenth Century). Saeculum Christianum 24: 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, Heinrich, and Jacob Sprenger. 1928. Malleus Maleficarum. Translated and Edited by Montague Summers. London: John Rodker. First published in 1484. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, Bruno. 1993. We Have Never Been Modern. London: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Lemay, Richard. 1962. Abū Ma’shar and Latin Aristotelianism in the Twelfth Century: The Recovery of Aristotle’s Natural Philosophy through Arabic Astrology. Beirut: American University of Beirut. [Google Scholar]

- Lemay, Richard. 1978. Origins and Success of the Kitāb Tamara of Abū Ja‘far Aḥmad ibn Yūsuf ibn Ibrahim from the Tenth to Seventeenth Century in the World of Islam and the Latin West. In Proceedings of the First International Symposium for the History of Arabic Science, University of Aleppo, Institute for the History of Arabic Science, April 5–12, 1976, Volume II, Papers in European Languages. Edited by Ahmad Y. Al-Hassan, Ghada Karmi and Nizar Namnum. Aleppo: University of Aleppo Press, pp. 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Lemay, Helen. 1980. The Stars and Human Sexuality: Some Medieval Scientific Views. Isis 71: 127–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilly, William. 2005. Christian Astrology. Abingdon: Astrology Classics. First published in 1647. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg, David C. 1992. The Beginnings of Western Science: The European Scientific Tradition in Philosophical, Religious, and Institutional Context, 600 B.C. to A.D. 1450. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Litt, Thomas. 1963. Les corps célestes dans l’univers de saint Thomas d’Aquin. Louvain: Publications Universitaire. [Google Scholar]

- Luther, Martin. 1823. On the Bondage of the Will. Translated and Edited by Henry Cole. London: T. Bensley. First published 1525. [Google Scholar]

- Machiavelli, Niccolò. 2005. The Prince. Translated and Edited by Peter Bondanella. Oxford: Oxford University Press. First published in 1532. [Google Scholar]

- Machiavelli, Niccolò. 2019. Machiavelli: Political, Historical, and Literary Writings. Edited by Mark Jurdjevic and Meredith K. Ray. Philadelphia: UPenn Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mandonnet, Pierre. 1910. Roger Bacon et la Speculum Astronomiae (1277). Revue néoscolastique de philisophie 17: 313–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, Christopher. 2011. ‘Fräulein Sprengel’ and the Origins of the Golden Dawn: A Surprising Discovery. Aries 11: 249–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriman, Marcus. 2000. The Rough Wooings: Mary Queen of Scots, 1542–1551. Edinburgh: Tuckwell Press. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, Richard A. 2020. Grace and Freedom: William Perkins and the Early Modern Reformed Understanding of Free Choice and Divine Grace. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nau, François. 1931–1932. Un fragment syriaque de l’ouvrages astrologiques de Claude Ptolémée intitulé le Livre du fruit. Revue de l’Orient chrétien 28: 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Orsesme, Nicole. 1952. Livre de Divinacions. In Nicole Oresme and the Astrologers. Edited by George William Coopland. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, pp. 50–121. First published in 1350. [Google Scholar]

- Paravicini Bagliani, Agostino. 2001. Le Speculum Astronomiae, une énigme? Enquête sur les manuscrits. Florence: SISMEL. [Google Scholar]

- Parel, Anthony J. 1991. The Question of Machiavelli’s Modernity. Review of Politics 53: 320–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parel, Anthony J. 1992. The Machiavellian Cosmos. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parel, Anthony J. 1993. Ptolemy as a Source of ‘The Prince 25’. History of Political Thought 14: 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Penny, D. Andrew. 1990. Free Will or Predestination: The Battle over Saving Grace in Mid-Tudor England. Suffolk: Boydell Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petrarch, Francesco. 1581. Epistolae rerum senilium. In Opera quae extant Omnia. Edited by Sebastian Henricpetri. Basel: Sebastian Henricpetri. [Google Scholar]

- Price, Betsey Barker. 1980. The Physical Astronomy and Astrology of Albertus Magnus. In Albertus Magnus and the Sciences. Edited by James A. Weisheipl. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Medieval Studies, pp. 155–85. [Google Scholar]

- Pseudo-Ptolemy. 1936. Centiloquium. In Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos, or Quadripartite: Being Four Books on the Influence of the Stars. Translated and Edited by J. M. Ashmand. Chicago: Aries Press, pp. 153–61. First published ca. 912-922. [Google Scholar]

- Ptolemy, Claudius. 1936. Tetrabiblos. In Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos, or Quadripartite: Being Four Books on the Influence of the Stars. Translated and Edited by J. M. Ashmand. Chicago: Aries Press, pp. 1–143. First published ca. 150 C.E. [Google Scholar]

- Recorde, Robert. 1556. The Castle of Knowledge. London: Reginald Wolfe. [Google Scholar]

- Ridder-Patrick, Jane. 2012. Astrology in Early Modern Scotland, 1560–1726. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Rinotas, Athanasios. 2015. Compatibility between Philosophy and Magic in the Work of Albertus Magnus. Revisita Española de Filosofía Medieval 22: 171–80. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, Bruno. 2000. Richard de Fournival, auteur du Speculum astronomie? Archives d’histoire doctrinale et littéraire du Moyen Âge 67: 159–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rutkin, H. Darrell. 2013. Astrology and Magic. In A Companion to Albert the Great: Theology, Philosophy, and the Sciences. Edited by Irven M. Resnick. Leiden: Brill, pp. 451–505. [Google Scholar]

- Rutkin, H. Darrell. 2019. Sapientia Astrologica: Astrology, Magic, and Natural Knowledge, ca. 1250–1800, Part 1: Medieval Structures (1250–1500): Conceptual, Institutional, Socio-Political, Theologico-Religious and Cultural. Dordrecht: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Rutz, Matthew T. 2016. Astral Knowledge in an International Age: Transmission of the Cuneiform Tradition, ca. 1500–1000 B.C. In The Circulation of Astronomical Knowledge in the Ancient World. Edited by John M. Steele. Leiden: Brill, pp. 18–54. [Google Scholar]

- Saxony, John of. 1485. Libellus Ysagogicus Abdilaz: Id est serui gloriosi dei: Qui dicitur Alchabitius ad magisterum iudiciorum astrorum. Venice: Erhard Ratdolt. [Google Scholar]

- Sirasi, Nancy G. 1990. Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stanglin, Keith D., and Thomas H. McCall. 2012. Jacob Arminius: Theologian of Grace. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, Robert, ed. 1898. Three Prose Versions of the Secretum Secretorum. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Alasdair M. 1975. Sapiens Dominabitur Astris: Wedderburn, Abell, and Luther. Aberdeen Review 46: 55–62. [Google Scholar]

- Tempier, Étienne. 1974. The Condemnation of 1277. In A Sourcebook in Medieval Science. Translated and Edited by Edward Grant. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tester, S. Jim. 1987. A History of Western Astrology. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thijssen, Johannes M.M.H. 1997. What Really Happened on 7 March 1277? In Texts and Contexts in Ancient and Medieval Science. Edited by Edith Sylla and Michael McVaugh. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, pp. 84–105. [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike, Lynn. 1934. History of Magic and Experimental Science, Vol. 4: The Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, Part 2. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike, Lynn. 1955. The True Place of Astrology in the History of Science. Isis 46: 273–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Asselt, Wilhelm, J. Martin Bac, and Roelf T. ta Velt, eds. 2010. Reformed Thought on Freedom: The Concept of Free Choice in Early Modern Theology. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- van Heijnsbergen, Theo. 2004. Paradigms Lost: Sixteenth-Century Scotland. In Schooling and Society: The Ordering of Reordering of Knowledge in the Western Middle Ages. Edited by Alasdair A. MacDonald and Michael W. Twomey. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

- van Heijnsbergen, Theo. 2013. The Renaissance Uses of a Medieval Seneca: Murder, Stoicism, and Gender in the Marginalia of Glasgow Hunter 297. Studies in Scottish Literature 39: 55–81. [Google Scholar]

- Vanden Broecke, Steven. 2003. The Limits of Influence: Pico, Louvain, and the Crisis of Renaissance Astrology. Boston and Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Vermij, Reink, and Hiro Hirai, eds. 2017. The Marginalization of Astrology. Early Science and Medicine 22: 405–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- von Regensburg, Berthold. 1862. Völlstandige Ausgabe seiner Predigten. Edited by Franz Pfeiffer. Vienna: Wilhelm Braumüller. [Google Scholar]

- Waterworth, Jamesand, ed. 1835. The Council of Trent: The Canons and Decrees of the Sacred and Œcumenical Council of Trent. Jamesand Waterworth, trans. London: Dolman. [Google Scholar]

- Wedel, Theodore Otto. 1920. The Medieval Attitude towards Astrology. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weill-Parot, Nicolas. 2018. La Biblionomia de Richard de Fournival, le Speculum astronomiae et le secret. In Richard de Fournival et les sciences au XIIIe siècle. Edited by Joëlle Ducos and Christopher Lucken. Florence: SISMEL, pp. 323–38. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, Roy, and Patrick Curry. 2004. Pulling Down the Moon: Astrology, Science, and Culture. New York: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Wither, George. 1635. A Collection of Emblems, Ancient and Moderne. London: A.M. for Henry Tauntan. [Google Scholar]

- Zambelli, Paola. 1982. Albert le Grand et l’astrologie. Recherches de Théologie Ancienne et Medieval 49: 141–58. [Google Scholar]

- Zambelli, Paola. 1992. The Speculum Astronomiae and Its Enigma: Astrology, Theology, and Science in Albertus Magnus and his Contemporaries. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Zambelli, Paola. 2007. White Magic, Black Magic, and the European Renaissance: From Pico, Ficino, della Porta to Trithemius, Agrippa, Bruno. Boston and Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niermeier-Dohoney, J. Sapiens Dominabitur Astris: A Diachronic Survey of a Ubiquitous Astrological Phrase. Humanities 2021, 10, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/h10040117

Niermeier-Dohoney J. Sapiens Dominabitur Astris: A Diachronic Survey of a Ubiquitous Astrological Phrase. Humanities. 2021; 10(4):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/h10040117

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiermeier-Dohoney, Justin. 2021. "Sapiens Dominabitur Astris: A Diachronic Survey of a Ubiquitous Astrological Phrase" Humanities 10, no. 4: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/h10040117

APA StyleNiermeier-Dohoney, J. (2021). Sapiens Dominabitur Astris: A Diachronic Survey of a Ubiquitous Astrological Phrase. Humanities, 10(4), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/h10040117