Representation of Whom? Ancient Moments of Seeking Refuge and Protection

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Protagonists of Ancient Refuge Seeking

But will you banish me without the regard due a suppliant?…I accept my exile: it was not exile I sought reprieve of.(Euripides, Medea lines 326, 338)

Euripides’s harrowing dramatisation of Medea’s abandonment by the oath-breaking Jason, of her wrath, of the agony of loss and of her enduring exile, continues to resonate through the ages.What do I gain by living? I have no fatherland, no house, and no means to turn aside misfortune. My mistake was when I left my father’s house, persuaded by the words of a Greek. This man—a god being my helper—will pay for what he has done to me.… Let no one think me weak, contemptible, untroublesome.No, quite the opposite, hurtful to foes, to friends kindly. Such persons live a life of greatest glory.(Euripides, Medea lines 798–810)

So I (ἐγὼ) too, fond of lamenting in Ionian strains,rend my soft, sun-baked cheekand my heart unused to tears;I cull the flowers of grief,in apprehension whether these friendless exilesfrom the Land of Mistshave any protector here.(Aeschylus Suppliant Women, lines 69–76)

Such brief accounts are situated as stages within wider historical descriptions of conflict and interstate relations where there is little space for, or interest in, pausing to consider what such an experience entailed in negotiation for protection, the places of refuge, everyday life there and modes of survival.… at Alba oppressive silence and grief that found no words quite overwhelmed the spirits of all the people; too dismayed to think what they should take with them and what leave behind, they would ask each other’s advice again and again, now standing on their thresholds, and now roaming aimlessly through the houses they were to look upon for that last time.Rome, meanwhile, was increased by Alba’s downfall. The number of citizens was doubled.(Livy 1. 29.3; 1.30.1)

3. Episodic Images of Flight and Appeals for Protection

Come then, dear father, mount upon my neck;on my own shoulders I will support you, and this task will not weigh me down.(Vergil Aeneid, 2.707–708)

O ancestral gods, hear us with favour, and see where justice lies:by not giving our youth to be possessed in marriageagainst what is proper,by showing you truly hate outrageous behaviour,you will act justly < >Even for distressed fugitives from waran altar is a defence against harm that gods respect.(Aeschylus, Suppliant Women, lines 79–85)

Why do you say you are supplicating me in the name of these Assembled Gods, holding these fresh-plucked, white-wreathed boughs?

So that I may not become a slave to the sons of Aegyptus.(Aeschylus, Suppliant Women, lines 333–35)

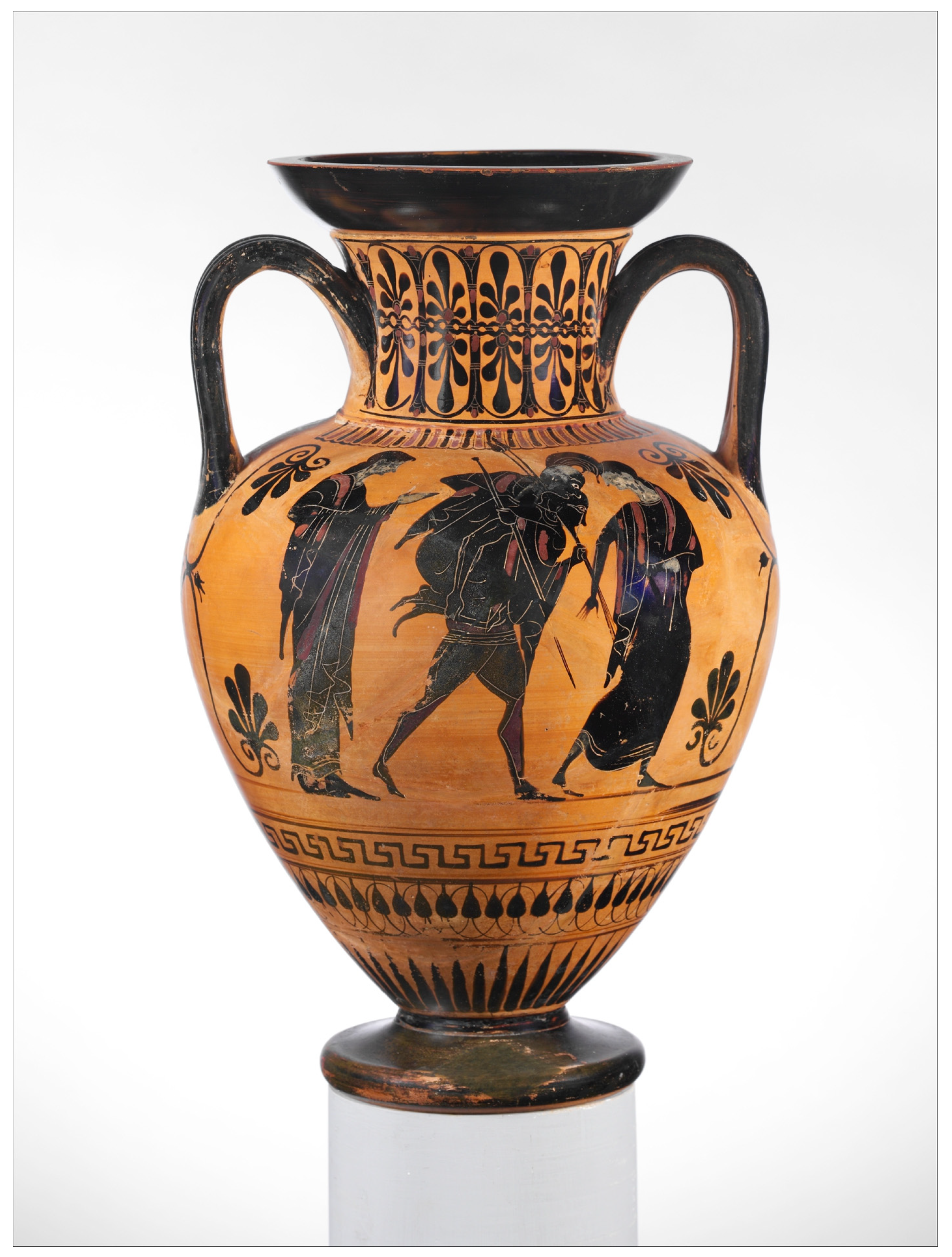

By continually making reference to the protective altars and statues surrounding them, the Suppliant Women’s chorus animates the divine beings and compels them into guardianship of the refuge seekers. While no ancient images depicting episodes from the Suppliant Women have been recognised to date (Taplin 2007, p. 146), illustrations of other such moments do survive. The most analogous is a scene on a red-figure Lucanian pelike of circa 400 BCE, from South Italy (Figure 3). The composition illustrates an episode from the myth of Herakles’ children in flight from the Argive king Eurystheus, which is the subject of Euripides’ tragedy Herakleidai.28If you don’t make a promise to our band that we can rely on—…With all speed… [we will] hang ourselves from these gods.…You understand! I have opened your eyes to see more clearly.(Aeschylus, Suppliant Women, lines 461, 465, 467)

4. Modes of Petitioning in Negotiations for Refuge and Protection

Yet it is precisely bold speech that we hear from suppliants in Greek tragedies, such as the argument presented by the guardian Iolaus, in Euripides’ Herakleidai. His response is addressed to the Athenian citizens and most directly to Demophon, their king. The response acts as a counter to the threatening words of the herald of the Argive king, Eurystheus, whose mission is to prevent the Athenians from giving refuge to Herakles’ children:33answer the natives in words that display respect, sorrow and need,as it is proper for outsiders to do,explaining clearly this flight of yours which is not due to bloodshed.Let your speech, in the first place, not be accompanied by arrogance,and let it emerge from your disciplined faces and your calm eyesthat you are free of wantonness…Remember to be yielding—you are a needy foreign refugee:bold speech does not suit those in a weak position.(Aeschylus, Suppliant Women, lines 192–199)

I am an Argive myself, and those I am seeking to remove are Argives who have run away from my own country, persons sentenced to die in accordance with that country’s laws. We, who are the city’s inhabitants, have the right to pass binding sentences against our own number.(Euripides, Herakleidai, lines 139–46)

My lord, since this is the law in your land, I have the right to hear and be heard in turn, and no one shall thrust me away before I am done, as they have elsewhere.We have nothing to do with this man. Since we no longer have a share in Argos, and this has been ratified by vote, but are in exile from our native land, how can this man rightfully take us off as Mycenaeans, when they have banished us from the country? We are now foreigners. Or do you think it right that whoever is banished from Argos should be banished from the whole Greek world?(Euripides, Herakleidai lines 181–90)

For when the Argives came to your ancestors and implored them to take up for burial the bodies of the dead at the foot of the Cadmea, your forefathers yielded to their persuasion … and thus not only gained renown for themselves in those times, but also bequeathed to your city a glory never to be forgotten for all time to come, and this glory it would be unworthy of you to betray. For it is disgraceful that you should pride yourselves on the glorious deeds of your ancestors and then be found acting concerning your suppliants in a manner the very opposite of theirs.(Isocrates, Plataicus, 14.53)

to have no refuge, to be without a fatherland, daily to suffer hardships and to watch without having the power to succour the suffering of one’s own, why need I say how far this has exceeded all other calamities?(Isocrates, Plataicus, 14.55)

The Plataeans do not hide their position of weakness, destitution or expulsion from their city. Instead, they confront the Athenians as equals, as previous allies, as hosts and as compatriots in exile; after all, the people of Athens, too, have endured its hardship. In praising them for their past glory and just actions, the Plataeans challenge them to live up to the prominence of their ancestors and stand by their claims of greatness. They also remind the Athenians of reciprocal duties owed for the refuge they previously received among the Plataeans.Alone of the Greeks you Athenians owe us this contribution of succour, to rescue us now that we have been driven from our homes. It is a just request, for our ancestors, we are told, when in the Persian War your fathers had abandoned this land, alone of those who lived outside of the Peloponnesus shared in their perils and thus helped them to save their city. It is but just, therefore, that we should receive in return the same benefaction which we first conferred upon you.(Isocrates, Plataicus, 14.56–57)

5. Conclusions

Hamid says that focusing on the journey is part of the othering. He avoids journeys, which in his eyes make refugees look different from non-refugees, to focus on everyday experiences that the majority of human beings share, such as love, sadness, and the will to live.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | See, for example, the way that late antique terminologies and the status categorisation of noncitizens and outsiders were connected to levels of protection (Peters 2019, pp. 87–88). |

| 2 | (Gray 2015), in particular, discusses forms of exilic discourse in his Stasis and Stability. See also (Dougherty 2022; Kasimis 2018; Isayev 2022). |

| 3 | For perspectives on permanent temporariness, see (Gizaw 2022; Hilal and Petti 2018); for context and further discussion in relation to ancient wandering, see (Isayev 2021). |

| 4 | (Arendt 1943, p. 264) (in Kohn and Feldman edition 2007). See also discussion: (Ritivoi 2019), especially p. 103. |

| 5 | Isocrates 14, Plataicus. All text and translations are from: Isocrates. Evagoras, Helen. Busiris. Plataicus. Concerning the Team of Horses. Trapeziticus. Against Callimachus. Aegineticus. Against Lochites. Against Euthynus. Letters. Translated by La Rue Van Hook. Loeb Classical Library 373. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1945. |

| 6 | The frequency of this is indicated in the case of the Acarnians and is noted below: Polybius, Histories 9.40. |

| 7 | Polybius, Histories 1.18.6–7. |

| 8 | Polybius, Histories 1.29.6–7. |

| 9 | Polybius, Histories 1.61.8. |

| 10 | A substantial collection is included in IG XII, 6.1.17–41 (IG–Inscriptiones Graecae 2000), with detailed discussions by (Engen 2010; Gray 2015; Rubinstein 2018). |

| 11 | Xenophon, Anabasis; Cicero, ad Familiares 4.4.4; Ovid, Tristia. |

| 12 | |

| 13 | For an overview of ancient migration and mobility, see (Baroud and Isayev 2022; Isayev 2017a, chps. 1, 10, 11). |

| 14 | Polybius, Histories 9.40. |

| 15 | See, for example, the complicated story of Polyartus, who attempted to seek sanctuary at the public hearth of Phaselis: Polybius Histories 30.9. |

| 16 | Euripides, Medea. For a more extensive discussion, see Isayev (2021, esp. 12–16). All text and translations are from the Loeb edition: Euripides. Cyclops. Alcestis. Medea. Loeb Classical Library 12. Edited and translated by David Kovacs. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994. vol. 1. For a detailed discussion see (Bakewell 2013; Cole 2004; Isayev 2017b; Zeitlin 1992). |

| 17 | Aeschylus, Suppliant Women, Lines 69–76. All text and translations are from Aeschylus. Persians. Seven against Thebes. Suppliants. Prometheus Bound. Loeb Classical Library 145. Edited and translated by Alan H. Sommerstein. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 2009. |

| 18 | These include studies on the ancient context, such as (Garland 2014), and the more contemporary, such as (Derrida [1997] 2000). |

| 19 | Euripides Medea created in 431 BCE; Euripides, Helen created in 412 BCE. |

| 20 | Livy, Ab Urbe Condita. For an extended discussion on the subject, see Isayev 2017a. All text and translations are from Livy. History of Rome, Volume V: Books 21–22. Loeb Classical Library 233. Translated by B. O. Foster. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1929. |

| 21 | In relation to their presentation as dregs of society, see Jewell (2019). For critical discourse on the plebeians and earlier bibliography, see (Logghe 2017; Mouritsen 2001; Purcell 1994). |

| 22 | Vergil Aeneid. All text and translations are from: Virgil. Eclogues. Georgics. Aeneid: Books 1–6. Translated by H. Rushton Fairclough. Revised by G. P. Goold (2019). Loeb Classical Library 63. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1916. |

| 23 | |

| 24 | For example, the 1st-century CE wall painting that used to adorn the House of M. Fabius Ululitremulus in Pompeii, IX.13.5: (Spinazzola 1953, Tav. XVII). |

| 25 | Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, 189 UNTS 150, 28 July 1951 (entered into force 22 April 1954). |

| 26 | For a discussion on historical cases and the conflicting debates around giving asylum, see (Chaniotis 1996; Naiden 2006, 2014; Sinn 1993). Examples of unsympathetic treatment of suppliants, where such treatment tends to have moralistic undertones in ancient literature, catalysed many legends that speak of punishments against the perpetrators, often in the form of natural disasters: earthquakes and tidal waves are noted for example by Pausanias 7.25.1 and Thucydides 1.128.1. |

| 27 | Isocrates 14, Plataicus. |

| 28 | That the image is most likely related to the opening scenes of Euripides Heraklaiedai: (Taplin 2007, p. 127). |

| 29 | For an overview of supplication scenes on ancient vases, see (Pedrina 2017). |

| 30 | For the interest in Greek theatre outside Greece and its representation, see (Biles and Thorn 2014; Robinson 2014; Nervegna 2015; Taplin 2007, 2012). |

| 31 | Reference and provenance: Louvre G458: https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010270306 (accessed on 10 December 2022). |

| 32 | They may represent what (Sassen 2014, p. 211) refers to as the ‘systemic edge’: ‘the extreme character of conditions at the edge makes visible larger trends that are less extreme and hence more difficult to capture’. |

| 33 | Euripides Heraklaiedai. See also a discussion on the play: (Burnett 1976; Tzanetou 2012, pp. 73–104). All text and translations are from Euripides. Children of Heracles. Hippolytus. Andromache. Hecuba. Loeb Classical Library 484. Edited and translated by David Kovacs. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995. |

| 34 | All text and translations are from: Isocrates. Evagoras, Helen. Busiris. Plataicus. Concerning the Team of Horses. Trapeziticus. Against Callimachus. Aegineticus. Against Lochites. Against Euthynus. Letters. Translated by La Rue Van Hook. Loeb Classical Library 373. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1945. |

| 35 | (Chaniotis 1996, esp. 82–86). For contemporary perspectives on representation of refugee experiences, asylum requests and the law, see (Behrman 2016). |

| 36 | For a discussion on accords, statutes and laws that would have impacted on the potential to be given or denied refuge and protection: (Moatti 2021). |

| 37 | Isocrates 14, Plataicus, lines 45–47, 57; for a discussion on services, see (Isayev 2017b). |

| 38 | For a discussion on ancient refuge and contexts of citizenship, see (Gray 2018), and in relation to the metic (resident alien), see (Kasimis 2018). |

| 39 | Some examples of the discourse on the most recent events include (Neumann 2021, 2022). Those concerning these last decades include (Malkki 1992; Mbembe 2003, 2019; De Genova 2010; Mezzadra and Neilson 2013; Tazzioli 2015; Boano and Astolfo 2020). |

References

- Arendt, Hannah. 1943. We Refugees. Menorah Journal 31: 69–77, Reprinted in The Jewish Writings. Editedy by Jerome Kohn and Rob H. Feldman. 2007. New York: Schocken Books, pp. 264–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bakewell, Geoffrey W. 2013. Aeschylus’s Suppliant Women: The Tragedy of Immigration. Madison and London: University of Wisconsin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baroud, George, and Elena Isayev. 2022. migration and mobility. In Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrman, Simon. 2016. Between Law and the Nation State. Refuge: Canada’s Journal on Refugees 32: 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biles, Zachary, and Jed Thorn. 2014. Rethinking Choregic Iconography in Apulia. In Greek Theatre in the Fourth Century B.C. Edited by Eric Csapo, Hans Goette, Richard Green and Peter Wilson. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 295–318. [Google Scholar]

- Blommaert, Jan. 2001. Investigating Narrative Inequality: African Asylum Seekers’ Stories in Belgium. Discourse and Society 12: 413–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blommaert, Jan. 2009. Language, Asylum, and the National Order. Current Anthropology 50: 415–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boano, Camillo, and Giovanna Astolfo. 2020. Notes around Hospitality as Inhabitation Engaging with the Politics of Care and Refugees’ Dwelling Practices in the Italian Urban Context. Migration and Society: Advances in Research 3: 222–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, Anne. 1976. Tribe and City, Custom and Decree in Children of Heracles. Classical Philology 71: 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabot, Heath. 2019. The business of anthropology and the European refugee regime. American Ethnologist 46: 261–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaniotis, Angelos. 1996. Conflicting Authorities: Asylia between Secular and Divine Law in the Classical and Hellenistic Poleis. Kernos 9: 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, Susan G. 2004. Landscapes, Gender, and Ritual Space: The Ancient Greek Experience. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coutin, Susan Bibler, and Erica Vogel. 2016. Migrant Narratives and Ethnographic Tropes: Navigating Tragedy, Creating Possibilities. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 45: 631–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Genova, Nicholas. 2010. The queer politics of migration: Reflections on “Illegality” and incorrigibility. Studies in Social Justice 4: 101–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derrida, Jacques. 2000. Of Hospitality: Anne Dufourmantelle Invites Jacques Derrida to Respond. Translated by Rachel Bowlby. Stanford: Stanford University Press. First published 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty, Carol. 2022. As If a Stranger at the Door: Hospitality and Tragic Form in Democratic Athens. Social Research 89: 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engen, Darel T. 2010. Honor and Profit: Athenian Trade Policy and the Economy and Society of Greece, 415–307 BCE. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, Robert. 2014. Wandering Greeks: The Ancient Greek Diaspora from the Age of Homer to the Death of Alexander the Great. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gizaw, Gerawork T. 2022. Kakuma Refugee Camp: Pseudo-Permanence in Permanent Transience. Africa Today 69: 162–89. [Google Scholar]

- Gizaw, Gerawork T., and Kate Reed. 2022. ‘No Words’: Refugee Camps and Empathy’s Limits. Public Books. Available online: https://www.publicbooks.org/refugee-camps-empathy-narrative/ (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Gray, Benjamin. 2015. Stasis and Stability: Exile, the Polis, and Political Thought, c. 404–146 BC. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Benjamin. 2018. Citizenship as Barrier and Opportunity for Ancient Greek and Modern Refugees. Humanities 7: 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, Mohsin. 2017. Exit West. Harlow: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hilal, Sandi, and Alessandro Petti. 2018. Permanent Temporariness. Stockholm: Art and Theory Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- IG–Inscriptiones Graecae. 2000. IG XII.6–Inscriptiones Graecae: Inscriptiones Chii et Sami cum Corassiis Icariaque. Edited by Klaus Hallof and Angelos P. Matthaiou. Berlin and New York: Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften. [Google Scholar]

- Isayev, Elena. 2017a. Migration, Mobility and Place in Ancient Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Isayev, Elena. 2017b. Between Hospitality and Asylum: A Historical Perspective on Agency. International Review of the Red Cross, Migration and Displacement 99: 1–24, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isayev, Elena. 2021. Ancient Wandering and Permanent Temporariness. Humanities 10: 91, Edited by E. Isayev and E. Jewell. Special Issue Displacement and the Humanities: Manifestos from the Ancient to the Present. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isayev, Elena. 2022. Hosts and Higher Powers: Asylum Requests and Sovereignty. In Sovereignty: A Global Perspective. Proceedings of the British Academy. Edited by Christopher Smith. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 282–306. [Google Scholar]

- Jewell, Evan. 2019. (Re)moving the Masses: Colonisation as Domestic Displacement in the Roman Republic. Humanities 8: 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasimis, Demetra. 2018. The Perpetual Immigrant and the Limits of Athenian Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Khosravi, Shahram. 2018. Afterword: Experiences and Stories along the Way. Geoforum 116: 292–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobelinsky, Carolina. 2015. Judging Intimacies at the French Court of Asylum. PoLAR 38: 338–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushner, Tony. 2006. Remembering Refugees: Then and Now. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Logghe, Loonis. 2017. Plebeian agency in the later Roman Republic. In Mass and Elite in the Greek and Roman Worlds. From Sparta to Late Antiquity. Edited by Richard Evans. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, pp. 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Luraghi, Nino. 2008. The Ancient Messenians: Constructions of Ethnicity and Memory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Malkki, Liisa H. 1996. Speechless Emissaries: Refugees, Humanitarianism, and Dehistoricization. Cultural Anthropology 11: 377–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkki, Liisa. 1992. National Geographic: The Rooting of Peoples and the Territorialization of National Identity among Scholars and Refugees. Cultural Anthropology 7: 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkki, Liisa. 1995. Purity and Exile: Violence, Memory, and National Cosmology among Hutu Refugees in Tanzania. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marfleet, Philip. 2007. Refugees and History: Why We Must Address the Past. Refugee Survey Quarterly 26: 136–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfleet, Philip. 2011. Understanding ‘Sanctuary’: Faith and Traditions of Asylum. Journal of Refugee Studies 24: 440–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbembe, Achille. 2003. Necropolitics. Translated by Libby Meintjes. Public Culture 15: 11–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbembe, Achille. 2019. Necropolitics. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mezzadra, Sandro, and Brett Neilson. 2013. Border as Method, or the Multiplication of Labor. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moatti, Claudia. 2021. Mobilite, refugies et droit dans le monde romain. (Mobility, Refugees and the law in the Roman World). Vergentis. Revista de Investigación de la Cátedra Internacional Conjunta Inocencio III 12: 19–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mouritsen, Heinrik. 2001. Plebs and Politics in the Late Roman Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Naiden, Fred S. 2006. Ancient Supplication. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Naiden, Fred S. 2014. So-Called “Asylum” for Suppliants. Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 188: 136–38. [Google Scholar]

- Nervegna, Sebastiana. 2015. The Actors’ Repertoire, Fifth-Century Comedy and Early Tragic Revivals. CHS Research Bulletin 3. Available online: http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:NervegnaS.The_Actors_Repertoire.2015 (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Neumann, Klaus. 2021. ‘Uses and abuses of refugee histories’. In Refugee Journeys: Histories of Resettlement, Representation and Resistance, 1st ed. Edited by Jordana Silverstein and Rachel Stevens. Canberra: ANU Press, pp. 211–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, Klaus. 2022. ‘European Solidarity’. Inside Story. December 3. Available online: https://insidestory.org.au/european-solidarity/ (accessed on 15 February 2023).

- Osman, Alideeq. 2020. Prison of Dust: One Man’s Experience of Life in a Dadaab Refugee Camp. Independently Published-Public Books. [Google Scholar]

- Pedrina, Marta. 2017. La supplication sur les vases grecs. Mythes et images. Biblioteca di “Eidola” 2. Pisa. Roma: Fabrizio Serra Editore. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Edward. 2019. Viatores: Images of Forced Migrants and Refugees, Medieval and Contemporary. Viator 50: 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrain, David. 2014. Homer in Stone: The Tabulae Iliacae in Their Roman Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell, Nicholas. 1994. The City of Rome and the plebs urbana in the Late Republic. In The Cambridge Ancient History, 2nd ed. Edited by John A. Crook, Andrew Lintott and Elizabeth Rawson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, vol. 9, pp. 644–88. [Google Scholar]

- Rabben, Linda. 2016. A Thousand Years of Medieval Sanctuary. In Sanctuary and Asylum: A Social and Political History. Seattle: University of Washington Press, pp. 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ranieri Panetta, Marisa, ed. 2005. Pompeji. Geschichte, Kunst und Leben in der versunkenen Stadt. Stuttgart: Belser. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, Kate, and Marcia C. Schenck, eds. 2023. The Right to Research: Historical Narratives by Refugee and Global South Researchers. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ritivoi, Andreea Deciu. 2019. Reading (with) Hannah Arendt: Aesthetic Representation for an Ethics of Alterity. Humanities 8: 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Edward. 2004. Reception of comic theatre amongst the indigenous south Italians. Mediterranean Archaeology 17: 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Edward. 2014. Greek Theatre in Non-Greek Apulia. In Greek Theatre in the Fourth Century B.C. Edited by Eric Csapo, Hans Goette, Richard Green and Peter Wilson. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 319–32. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein, Lene. 2018. Immigration and Refugee Crises in Fourth-Century Greece: An Athenian Perspective. The European Legacy 23: 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassen, Saskia. 2014. Expulsions. Brutality and Complexity in the Global Economy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sinn, Ulrich. 1993. Greek Sanctuaries as Places of Refuge. In Greek Sanctuaries: New Approaches. Edited by Nanno Marinatos and Robin Hagg. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Spinazzola, Vittorio. 1953. Pompei alla luce degli Scavi Nuovi di Via dell’Abbondanza (anni 1910–1923). Roma: La Libreria della Stato, Tav, XVII. [Google Scholar]

- Taplin, Oliver. 2007. Pots and Plays: Interactions between Tragedy and Greek Vase-Painting of the Fourth Century BC. Los Angeles: Getty Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Taplin, Oliver. 2012. How was Athenian tragedy played in the Greek West? In Theater outside Athens: Drama in Greek Sicily and South Italy. Edited by Kathryn Bosher. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 226–50. [Google Scholar]

- Tazzioli, Martina. 2015. Which Europe? Migrants’ uneven geographies and counter-mapping at the limits of representation. Movements. Journal for Critical Migration and Border Regime Studies 1: 1–19. Available online: http://movements-journal.org/issues/02.kaempfe/04.tazzioli--europe-migrants-geographies-counter-mapping-representation.html (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Tzanetou, Angeliki. 2012. City of Suppliants: Tragedy and the Athenian Empire. Austin: University of Texas Press. [Google Scholar]

- Varriale, Ivan. 2012. Architecture and Decoration in the House of Menander in Pompeii. In Contested Spaces. Houses and Temples in Roman Antiquity and the New Testament. Edited by David L. Balch and Annette Weissenrieder. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, pp. 163–84. [Google Scholar]

- Zeitlin, Froma. 1992. The Politics of Eros in the Danaid Trilogy of Aeschylus. In Innovations of Antiquity. Edited by Ralph Hexter and Daniel Seldon. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Isayev, E. Representation of Whom? Ancient Moments of Seeking Refuge and Protection. Humanities 2023, 12, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/h12020023

Isayev E. Representation of Whom? Ancient Moments of Seeking Refuge and Protection. Humanities. 2023; 12(2):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/h12020023

Chicago/Turabian StyleIsayev, Elena. 2023. "Representation of Whom? Ancient Moments of Seeking Refuge and Protection" Humanities 12, no. 2: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/h12020023

APA StyleIsayev, E. (2023). Representation of Whom? Ancient Moments of Seeking Refuge and Protection. Humanities, 12(2), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/h12020023