Abstract

The adultification of Black children is a form of anti-Blackness that brings Black children into adult situations. The adultification of Black children can be rooted in early 20th-century children’s books with minstrel imagery showing Black children in perilous situations for adult entertainment and for white children’s learning. This essay puts “digital blackface”—the online cross-racial memes using Black children’s reactions, emotions, and stereotypes as cross-racial humor—in conversation with historical children’s books featuring Black children. Linking digital representations and misrepresentations to children’s picture books demonstrates how Black children in both formats and social spheres are thrust into adult politics at their expense. Adultifying Black children across time in children’s books with minstrel imagery and digital blackface shows how Black children have never been exempt from the anti-Blackness and systemic white supremacy erroneously believed to be an adult issue.

What shall I tell my children who are BlackOf what it means to be a captive in this dark skin?What shall I tell my dear one, fruit of my womb.Of how beautiful they are when everywhere they turnThey are faced with abhorrence of everything that is Black?Margaret Burroughs, “What Shall I Tell My Children Who Are Black (Reflections of an African American Mother)” (Burroughs 1963)

1. Black Children and Anti-Blackness

The United States of America has a long, complicated, and disturbing multi-layered history of depicting Black children in problematic ways and treating them poorly. This treatment of Black children mirrors the treatment of Black adults rooted in the global illusion of white supremacy and often manifested in anti-Black violence, both real and fictional. Such anti-Blackness comes in many forms, one of which is digital memes that, while believed to be harmless online internet jokes, insert Black children into adult situations for the sake of adult racialized mockery and humor. Such online manifestations constitute another form of seemingly inconsequential discriminatory racial microaggressions. Amanda Williams offers social and political context for this kind of racial online activity:

While our essay is not a history of internet racism, we recognize unmistakable connections with early US children’s books. Our contention is that a certain genre of Black visualization in memes engages Black children in adult politics, reinforcing the same problematic messages that plagued early children’s books written primarily by non-Black authors invested in creating and sustaining the illusion of white superiority. This online adultification of Black children in memes extends the tenants of systemic racism that deny Black children—and by extension, Black people and entire Black communities—justice and humanity.Despite original projections that the Internet would provide a safe space for individuals belonging to marginalized groups, racial prejudice and discrimination persists online…. Internet memes are a popular and pervasive phenomenon that may contribute to the climate of racial discrimination that can exist in online communities. Internet memes are individual bits of cultural information… that are widely shared electronically. Although Internet memes are often intended to be social commentaries, they can be racist in nature. (Williams 2016)

More broadly speaking, digital blackface is the trend wherein adults across racial lines employ memes and gifs of Black people to express or emote online, typically for humor or comic relief to a viewing audience. We contend that digital blackface is rooted in the tradition of US minstrelsy wherein both Black and white actors darkened their faces to act out dehumanizing stereotypes and caricatures of Black people. Such stereotypes and caricatures served to uphold the illusion of the superiority of whiteness as a social construct. Such patterns of misrepresentation showed up in everyday ways, from commercial products to children’s songs and ditties and books created for young white reading audiences. Narrator Esther Rolle, in Marlon Riggs’s documentary Ethnic Notions (Riggs 1987), offers this catalog of anti-Black images that endure and impact racial attitudes today:

The mammy, the pickaninny, the coon, the Sambo, the Uncle. Well into the middle of the twentieth century, these were some of the most popular depictions of Black America…. These were the images that decorated our homes, that served and amused and made us laugh. Taken for granted, they worked their way into the mainstream of American life. Of ethnic caricatures in America, these have been the most enduring. Today, there’s little doubt that they shaped the most gut-level feelings about race.

That Black children were not exempt from these misrepresentations is evidenced in the myriad books intended for mostly white children, ensuring that the adult politics of white supremacy were socialized and perpetuated. Indeed, these images are the basis of digital blackface as defined by John Blake: “If a White person shares an image online that perpetuates stereotypes of Black people as loud, dumb, hyperviolent or hypersexual, they’ve entered digital blackface territory” (Blake 2023). The anonymity of memes and gifs makes it hard to locate their origins, even as digital blackface perpetuates and sustains harmful racial stereotypes with each keyboard click, heart, thumbs up, and share action. Such online creator anonymity means that there is little to no social accountability for digital blackface, what Ruha Benjamin calls the “New Jim Code,”

As a “New Jim Code,” children and adults fall prey to creators’ seemingly unending ways to keep Black people in their places of social subservience.an overt simultaneously private and public anti-blackness wherein technologies often hide, speed up, and even deepen discrimination, while appearing to be neutral or benevolent when compared to the racism of a previous era. This set of practices … en-compasses a range of discriminatory designs–some that explicitly work to amplify hierarchies, many that ignore and thus replicate social divisions, and a number that aim to fix racial bias but end up doing the opposite. (Benjamin 2019, p. 8)

This essay considers the visual and narrative parallels between children’s books written by racial outsiders for the sole purpose of advancing white supremacy and the digital manifestations of this blackface in a sampling of digital memes. Our effort is not to be exhaustive but rather to show how digitization is but one of the newest ways to practice racism and to observe and analyze US racism. Our cultural studies approach is informed by both studies in narrative and culture. More specifically, we see these representative early 1800s and 1900s white-authored children’s books in social and political conversation with present-day memes that continue the racial misrepresentation and dehumanization common to the Black adult world: Sara Cone Bryant’s Epaminondas and His Auntie (1937) and the meme “Did I Do That?”; Lynda Graham’s Pinky Marie: The Story of Her Adventure with the Seven Blackbirds (1939) and the meme “Crying Black Girl”; and Nora Case’s Ten Little N***er Boys and Ten Little N***er Girls (1962) with “African Kids Dancing.” While books are static in what and how they are published, meme images can take on different messages depending on the creators. What is consistent, however, no matter the caption, is the static visual that speaks to our digital blackface premise. Our work here aligns with Kim Gallon whose thoughts about the recovery work of digital Black humanities rest at the intersection of early racist children’s books and anti-Black digital memes:

Recovery rests at the heart of Black studies, as a scholarly tradition that seeks to restore the humanity of black people lost and stolen through systemic global racialization. It follows, then, that the project of recovering lost historical and literary texts should be foundational to the black digital humanities. It is a deeply political enterprise that seeks not simply to transform literary canons and historiography by incorporating black voices and centering an African American and African diasporic experience, though it certainly does that; black digital humanities troubles the very core of what we have come to know as the humanities by recovering alternate constructions of humanity that have been historically excluded from that concept. (Gallon 2016, p. 44)

The specific memes we have selected highlight how Black pain, specifically Black children’s pain, is often memeified for adult humor. These memes were chosen because they connect with the most prevalent blackface minstrelsy images and narratives in selected popular children’s books. These memes individually and collectively underscore a reoccurring pattern within the internet space regarding the treatment and adultification of Black children. This same kind of dehumanization across memes is not common in children’s books that feature white children. This adultifying and disparaging humor connecting past and present stereotypical representations drives our choices of memes. Calling out the prevalence of adultification through various forms of anti-Black violence at its center is a rescue and recovery effort to restore humanity to all Black people, adults and children alike.

2. No Innocence for Black Children

Children’s books with minstrel imagery were typically written by white authors making caricatures and stereotypes of Black children’s and adults’ lives and usually engaging in anti-Black violence to uphold the illusion of white supremacy. Librarian Augusta Baker addresses these inauthentic and humanizing representations:

Including memes that present both pre-teens and teenagers in our exercise underscores the fact of Black dehumanization and adultification from which no Black child is exempt. Considering teens also highlights that Black children are rarely allowed to exist in a world that does not make them victims of systemic racism and adultification. Anissa Durham explains this particular adult bias that other adults create and perpetuate:In the 1920s and 1930s, children’s books seemed to foster prejudice by planting false images in the minds of children. Most authors were white. With little knowledge about black life, and yet they wrote as if they were authorities. No wonder it was an accepted fact in children’s books that blacks were lazy, shiftless, lived in shanties, had nothing and wanted nothing, sang and laughed all day…. Consequently, few children knew that blacks lived just as other people lived, having the same aspirations and hopes. (Baker 1975)

Durham’s definition contextualizes these memes and children’s books as adult spaces wherein Black childhood as a social construct is denied even a semblance of the illusory innocence and purity of white children who are socially valued and worthy of adult protection and attention.Adultification bias is a stereotype based on the ways in which adults perceive children and their childlike behavior. It’s rooted in anti-Black racism that goes back to chattel slavery—as enslaved Black children were used for their labor, often working in the field with no recreation or means of gaining an education. This stereotype often treats Black children like they do not deserve to play. They need less nurturing, protection, support, and comfort. (Durham 2022)

Because anti-Black violence includes but also extends beyond physical injury, we include under this anti-Blackness umbrella the very act of adultification that denies Black children the ability to be seen and treated as innocents. As for this racialized, gendered, and classed notion of childhood innocence, Phillip Goff, in a study on Black boys and innocence, offers this clarification:

Black girls are also perceived and treated as being less innocent than white girls, as Monique Morris notes:Children in most societies are considered to be in a distinct group with characteristics such as innocence and the need for protection. Our research found that black boys can be seen as responsible for their actions at an age when white boys still benefit from the assumption that children are essentially innocent. (Goff et al. 2014)

Childhood innocence, then, is a privilege and luxury not afforded Black children in the same way that white children inhabit this ubiquitous, safe, and elevated social, political, and cultural space. For Black children, violence is normalized and pervasive, past and present, physical or representational.The assignment of more adult-like characteristics to the expressions of young Black girls is a form of age compression. Along this truncated age continuum, Black girls are likened more to adults than to children and are treated as if they are willfully engaging in behaviors typically expected of Black women. This compression strip[s] Black girls of their childhood freedoms [and] renders Black girlhood interchangeable with Black womanhood. The lack of protection and innocence leads to the criminalizing of Black children and making it impossible for Black children to make mistakes without severe consequences.

3. Children’s Books and Memes

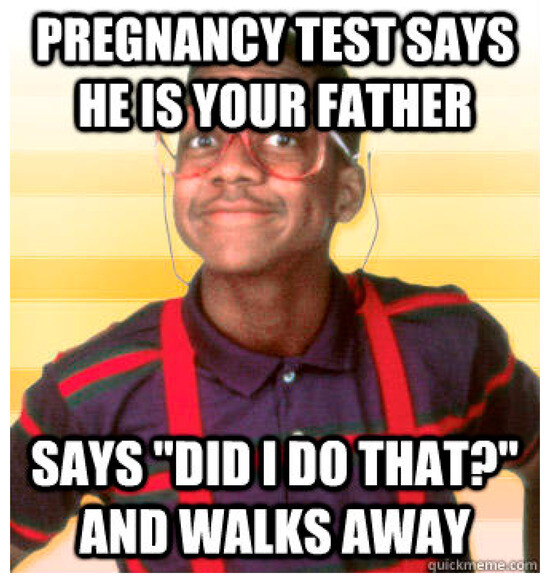

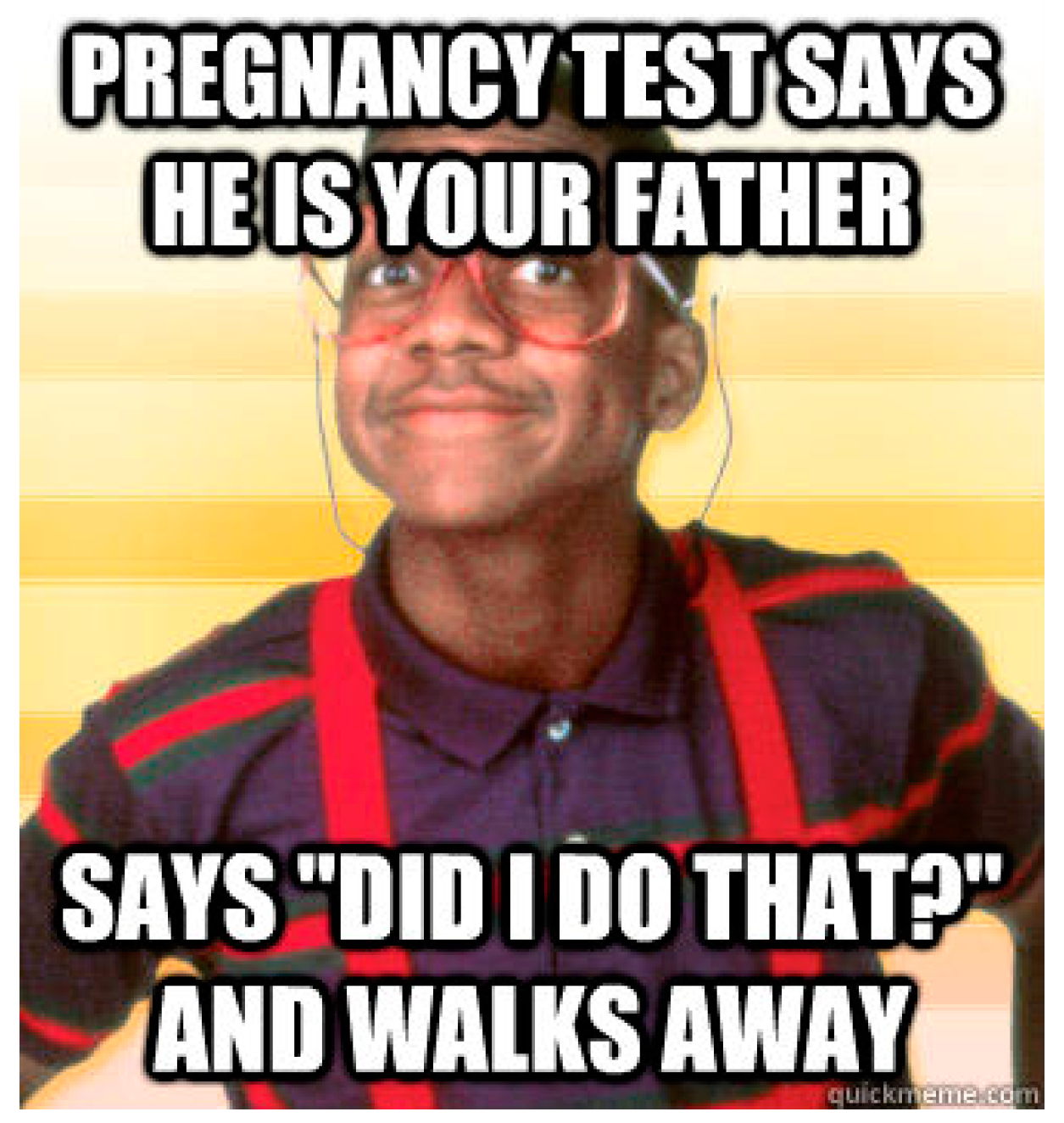

3.1. “Did I Do That?”: Urkel and Epaminondas

A meme based on the popular television show Family Matters (1989–1998) centers on the main character Steve Urkel’s catchphrase, “Did I do that?” to convey his nerdy confusion whenever something goes wrong. Urkel is a troublemaker and a social outcast within the show, and using this meme furthers that comic point. One of the running gags throughout the show and within each episode is that Urkel will do something wrong, be superficially punished, and ultimately utter his catchphrase, “Did I do that?” According to this sitcom formula, the African American family within the show—the Winslows—react with annoyance and anger at Urkel for the problems he causes. Although the Winslow family members tolerate him, the show’s comedy at Urkel’s expense comes in their efforts to rid themselves of him for causing problems. Urkel is a social outcast throughout the episodes until he transforms into his ultra-cool alter ego, Stefan Urquelle, who has swagger and does not have the high-pitched voice, oversized glasses, or suspenders that geeky Urkel has as his signature high-waisted costumed performance. That Urkel is a child throughout the show offers interesting commentary on the treatment of Black children, especially as comic relief. Arguably, Urkel is a part of the US minstrel tradition in his exaggerated nerd/geek portrayal and as a social outcast made into a joke at his own expense.

This visual meme (Figure 1) of Urkel is deliberate in its comic mockery and Othering. Urkel’s oversized glasses make his face clownish. His bulging eyes exaggerate his features and make his look funny and ridiculous, not unlike the white adult socially constructed “happy smiling darkies” trope common in so many popular children’s books, sheet music, commercial advertisements, and children’s plantation ditties. This meme visualization easily links to minstrelsy as it presents this Black child character as static, one-dimensional, and a source of others’ humor and entertainment. Elvin Holt, in “A Coon Alphabet and the Comic Mask of Racial Prejudice”—assessing A Coon Alphabet’s author and illustrator Edward Windsor Kemble’s drawings as “repulsive and degrading”—further explains this popular portrayal of Black adults and Black children alike:

In keeping with the prevailing stereotypes of the late nineteenth century, Kemble’s blacks are portrayed as nappy-headed, saucer-eyes, broad-nosed, thick-lipped, grinning, ragged subhumans whose misfortunes were an unending source of humor for whites….Kemble’s crude parody of black dialect creates the illusion of a black narrative voice caught up in a pathetic display of self-mockery. The visual images and the verses convey a powerful message about the way whites perceived blacks at the turn of the century. (Holt 1986, pp. 307–9)

Figure 1.

“Did I Do That?” meme features African American television fictional character Steve Urkel played by actor Jaleel White.

Figure 1.

“Did I Do That?” meme features African American television fictional character Steve Urkel played by actor Jaleel White.

This meme injects Urkel into an adult situation and circumstance through its caption, an allusion to the popular Maury (1991–2022), a US daytime television reality show often solely about paternity test reveals. This show was most often about young Black heterosexual couples getting the results of paternity tests as live audiences witnessed their emotional responses. Since, as the folkloric saying goes, “Momma’s baby is poppa’s maybe,” the show thrived in this Black stereotypical public space of Black adult promiscuity and social irresponsibility, especially regarding Black men who are either responsibility shirkers, deadbeat dads, or players incapable of monogamous relationship commitment until forced through public shaming.

This lack of Black male responsibility plays into the Black buck caricature of Black men as irresponsible and hypersexual. Suzane Jardim points out that “Black bucks are usually muscular men, who defy the will of the whites and are a damn menace to American society. They are excitable, restless, moody, impulsive, extremely violent, and of course, sexually attracted to white women—and only them” (Jardim 2016). While Steve Urkel is not the muscular personification of this buck image, the meme’s premise here is that heartless, philandering Black men target Black women to victimize in demonstration of their manhood. Attaching this adultification of adolescent Urkel to sexual promiscuity, unplanned pregnancy, and irresponsibility furthers the anti-Black stereotypes common to Black adults. This is also not far removed from the Black rapist stereotype that historically and hysterically created fear among white women and catalyzed white men to respond with lynching to protect virtuous white womanhood. In reality, teenagers do engage in sex and can impregnate and become pregnant. However, what is different here in this meme is that the hypothetical suggestion of Urkel doing so is the source of racist humor. The racist stereotypes at the center of Maury were deeply controversial, and rapper Chuck D took to Twitter to speak on it: “Just how much the fed$ pay these old white dudes like Maury & Jerry showtiming young folks dysfunctional sht on Air...especially young blacks. Beware of elder media Nucointelpro buzzards hovering. Everything ain’t entertainment in fact it’s exploitation.” Chuck D emphasizes how these reality shows—Maury and The Jerry Springer Show (1991–2018)—profited off distorted stereotypes of Black men as inactive fathers and hypersexual men while generating revenue for the shows’ presumably white creators and producers. This meme exploits Black cisgender males through racist stereotypes that paint Black males as irresponsible who, after impregnating unsuspecting women, are anti-social and unwilling to take responsibility for the children they co-created.

The meme caption furthers the Black buck caricature through Urkel’s smiling and taking no responsibility for his actions of allegedly impregnating someone. Here, Urkel is a child who is simultaneously mocked and adultified. Naomi Day explains how these kinds of gifs and images reduce compassion and understanding of different race groups: “Having more flat representations of Black people in images and GIFs does nothing to improve cross-cultural understanding. In my experience, it actually decreases the likelihood that people will extend compassion to other racial groups” (Day 2020). While teenage parenting is a reality for some, this meme’s humor denies Urkel a compassionate humanity of understanding what he might be going through as a teen parent; instead, linking him to the historical representations of hypersexualized Black males who need to be feared, tamed, policed, and too often killed. Danielle Selby speaks to the trope of Black men and boys as rapists:

From the Scottsboro Boys, who were wrongly convicted of raping two white women, to the “Exonerated Five” to Christopher Cooper, the man a white woman falsely told police had threatened her life in May, Black and brown men in America have continued to be perceived as dangerous, violent, and hypersexual. The harmful and racist stereotypes of Black men as predators has contributed to Black men being incarcerated at higher rates and to wrongful conviction. (Selby 2020)

As an historical literary companion to Urkel’s problematic representation above, Sara Cone Bryant’s Epaminondas and His Auntie (1937), illustrated by Inez Hogan, is a children’s book with blackface minstrel imagery depicting Black child Epaminondas’s efforts to complete chores for his “Auntie”—this generic Black women’s adult name itself one associated with US slavery and Jim Crow era segregation designed to keep Black people in their places of subservience beneath white people in every social aspect. Bryant’s book invokes visual minstrelsy with young Epaminondas and his family’s pitch-black skin, hair spiraling up from the boy child’s head, exaggerated bright red lips, and the characters’ exaggerated minstrelsy dialect. Throughout the story, Epaminondas follows his Auntie’s and Mammy’s instructions to the word, clearly not understanding the complexities of adult directions or instructions. For instance, Epaminondas first receives a cake from his Auntie to take home. Her instruction to him is to “take [cake] home to his Mammy—yet another racist derogatory naming for Black adult women with its own problematic social mythologies. The child hears and acts on this seemingly straightforward: “Epaminondas took it in his fist and held it all scrunched up tight…. By the time he got home, there wasn’t anything left but a fistful of crumbs” (Bryant 1976, p. 4). His understanding is that he should carry it like any other ordinary object, not like a delicate piece of cake that would crush in his tight fist. Having misunderstood what was being asked of him, he returns home to this adult chastisement and berating: “Epaminondas, you ain’t got the sense you was born with!” along with an explanation of what he should have done with handling the cake, but after the fact: “That’s no way to carry cake. The way to carry cake is to wrap it all up nice in some leaves and put it in your hat, and put your hat on your head, and come along home” (Bryant 1976, p. 6). The problem with the cake incident is that Epaminondas had not been given instructions on how to handle the cake and, therefore, had to figure it out on his own. When he fails to do so as the adults expect, he receives a shameful scorning: “Epaminondas, you ain’t got the sense you was born with!” (Bryant 1976, p. 8). That this child allegedly lacks what the chastising adult defines as “common sense” imagines that his thinking should “mirror the adults.’ This pattern of not understanding follows the child throughout every subsequent task he is given, tasks which he predictably fails at because he has no “common sense,” like cooling butter and caring for a puppy. Bryant even shows the child abusing a puppy because he does not understand what he has been instructed to do. Here, not only is the child being verbally abused, but the child is also unknowingly and unwittingly engaging in animal cruelty and violence.

This narrative and representation ignore the reality that Epaminondas is a young child of about seven or eight years old whose brain cannot know exactly what adults want when they do not spell out their wants and expectations. At no point in this story are the Black adults held accountable for failing to give this child age-appropriate instructions on how to care for the dog. Instead, he is supposed to know what to do with the dog, the butter, the cake, and lastly, the pies. This uneducable and unintelligent trope mocked Black adults and children in US minstrelsy, a source of entertainment and Othering that separated Black folks from intelligent white people who psychologically and systemically benefitted from these myriad and consistent Black misrepresentations. Past and present manifestations of white supremacy further created pseudo-science expressly to prove that Black people are less intelligent than white people, allegedly because they have smaller brains. Charles Murray and Richard Hernstein’s The Bell Curve (Herrnstein and Murray 1994), for example, was a New York Times best-seller arguing that Black people, especially economically insecure Black people, are less intelligent than other people. Tom Morganthau summarizes the authors’ racist notions:

Their most explosive argument is a blunt declaration that blacks as a group are intellectually inferior to whites…. Murray and Hernstein say the evidence of a black-white IQ gap is overwhelming. They think the difference helps explain why many blacks seem destined to remain mired in poverty, and they insist that whites and blacks alike must face up to the reality of black intellectual disadvantage. (Morganthau 1994, p. 53)

US minstrelsy presented Black people as ignorant and lacking intelligence, and the story of Epaminondas channels this sentiment through his many mistakes and mess-ups. Epaminondas is not granted the innocence of childhood to make mistakes and is instead told six different times that he has no common sense and verbally abused: “[Y]ou ain’t got the sense you was born with; you never did have the sense you was born with, you never will have the sense you was born with!” (Bryant 1976, p. 14). That his Mammy has given up on the possibility that Epaminondas will ever learn anything meaningful characterizes him as lacking intelligence even though he is a child. Such a static conclusion locks this Black child into the subhuman Other, also defined by white supremacy in much the way minstrelsy presented and defined Black adults. That a white author creates a verbally abusive and mean-spirited children’s text for white children speaks to a racist romanticization of Black people that ultimately justifies denying Black people their full humanity and their social justice.

Contrastingly, Amelia Bedelia (1963), by Peggy Parish, is another older children’s book featuring and premised on a white adult female housekeeper who makes multiple mistakes in her job. Amelia Bedelia does not lose her job after her many mess-ups; instead, her boss extends to her compassion, kindness, and forgiveness—fundamental elements that define humanity. In the end, Amelia Bedelia takes everything literally, much like Epaminondas—dressing food and dusting furniture, for example—but suffers no consequences for these actions. In Parish’s book, she is neither ridiculed nor mocked. In fact, when she is about to be fired from this job, she makes a pie that moves the white Rogers family from anger: “Mrs. Rogers was angry. She was very angry. She opened her mouth. Mrs. Rogers meant to tell Amelia Bedelia she was fired. But before she could get the words out, Mr. Rogers put something in her mouth. It was so good Mrs. Rogers forgot about being angry” (Parish 1963,p. 60). Thus, the book teaches forgiveness and human frailty that is not necessarily grounded in racial or adult mockery.

One might read these two instances of miscommunications in Epaminondas and Amelia Bedelia as adults not making their expectations clear to other adults and children. One might also read these stories as ableist, faultily assuming that every child and adult is neurotypical. Perhaps there are cognitive issues wherein one who receives instructional information may not understand what is being asked of them. To acknowledge such a possibility is once again to grant humanity and humility to all without mocking or otherwise shaming and belittling. Aamna Mohdin interviewed a Black woman diagnosed with ADHD who recalls being labeled defiant as a child in school because she was neurodivergent:

That white adults label this Black child here as difficult shows how adults across the racial spectrum adultify Black children.I went through all of my schooling without being diagnosed with ADHD; no one picked up on it. All my teachers just assumed I was being defiant, and my impulsive outbursts were seen as me being rude. They associated my behavior as a child with words you would use to describe an adult—they saw me as calculating and disrespectful, not just a young child struggling. They never gave me any grace as a child. (Mohdin 2022)

Urkel’s and Epaminondas’s representations reinforce violence toward Black children through adultification. Such adultification is not just fictionalized. It traces historically through real-life violence of Black boys as in the case of Emmett Till, a Black fourteen-year-old murdered by two white male adults for allegedly whistling at, touching, or “being fresh” with a white woman, a pronounced and deeply coded Jim Crow era taboo, especially for Black men and boys in their interactions with white women and white girls. His murderers seemed set on making Till pay for his mistake of not knowing the ways of Southern US culture regarding treating white people:

A Black child’s being talked to by adults in this way underscores the white patriarchal threat that shadowed all Black males—children and adults—for any real, suspected, or even fabricated racial transgression. Upon finding Till’s dead body, Sheriff H.C. Strider recounts this inherent Black male child adultification: “The body we took from the river looked more like that of a grown man instead of a young boy” (Famous Trials). The lack of childhood innocence denied Black children correlates to real-world violence toward Black children, as in the cases of Tamir Rice, Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, Alexander McClay Williams1, George Stinney2, and so many others.The men searched the occupied beds looking for Till. Coming to Till’s bed, Milam shined a flashlight in the boy’s face and asked, “You the n***ah that did the talking down at Money?” When Till answered, “Yeah,” Milam said, “Don’t say “yeah” to me, n***ah. I’ll blow your head off. Get your clothes on.” (Famous Trials)

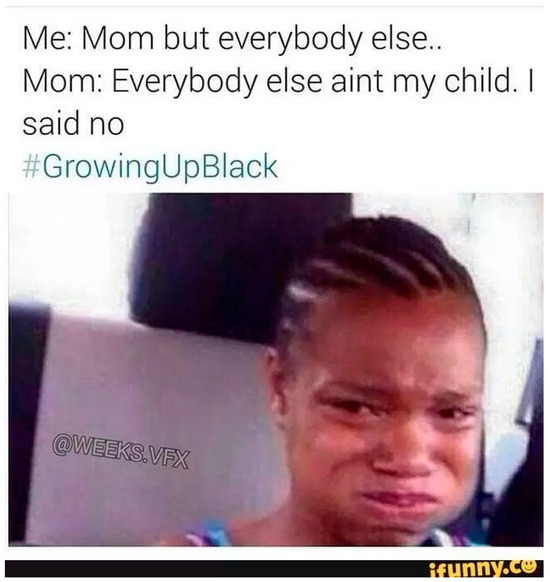

3.2. No Tears for “Crying Black Girl” and Pinky Marie

The “Crying Black Girl” meme shows a young nine- or ten-year-old Black girl crying in the backseat of a car, and is used online to convey emotional upset. Her crying could be due to frustration or sadness, as the meme leaves the possibility of both or neither. In this meme (Figure 2), the Black girl seems to be shying away from the photographer, perhaps because few adults or children would welcome being photographed in this state of emotional vulnerability, especially for the public display of social media. Being in a car suggests that her physical space is limited and that she is further cornered into this picture. The Black girl here is turned into a Black cultural joke. Lauren Michelle Jackson’s comments about digital blackface’s effects on Black women also apply to Black girls: “After all, our culture frequently associates black people with excessive behaviors, regardless of the behavior at hand. Black women will often be accused of yelling when we haven’t so much as raised our voice” (Jackson 2017). “Excessive behavior” is defined by adults and refers to Black girls showing emotions. In contrast, for white women and white children, crying is deemed a socially normal display of humanity and emotional complexity. The caption is part of the hashtag “Growing Up Black” about Black people making jokes about their potentially traumatic childhood experiences. While there is no proof that the person posting the meme is Black, the meme takes on different critical nuances through the lens of race. For instance, Ellen Jones is a white person who made a fake Black woman online profile named Wanda. Doing so is fundamentally blackface. That she does so allegedly to embody her racially problematic perceptions of Black people adds insult to this injurious creation. Jones justifies her racist creation as flattery:

A non-Black person fascinated with Black culture and Othering it by calling it “loud” and “weird” and then making a digital blackface profile engages in misogynoir, a specific humanity-denying sexism specifically towards Black women and girls.When I created Wanda, … I was living in northeast Washington DC, AKA ‘Chocolate City.’ I was surrounded by black culture at the time. I loved it and I miss it …. There is such a thing as black culture. It exists. And it’s great because it’s honest and loud and proud and it’s got character and funkiness and weirdness and backbone. (Jones 2020)

Figure 2.

“Crying Black Girl” meme features emotional young Black girl crying as she is stared at and photographed.

The “Crying Black Girl” meme makes fun of a Black girl’s pain and connects with Lynda Graham’s Pinky Marie: The Story of Her Adventure with the Seven Bluebirds (1939), a children’s book about a young eight- or nine-year-old Black girl being violently attacked by birds as she sleeps. This child is on a wagon with her father on a trip into town when she falls asleep. A flock of birds, envious of the child’s multiple bright colorful ribbons atop her pickaninny-imaged head, picks at her head to take out her many ribbons. While the child is rightfully upset and traumatized, her Black parents make light of the circumstance by giving her a bandanna to wear as though the Black girl child’s physical appearance is all that she has suffered and all that should matter in this adult world. The parents easily give up looking for the ribbons even as Pinky Marie cries. Making light of the violent bird assault that is easily akin to rape, her parents respond to the child’s distraught by giving her a headscarf to cover her head; thus, visually making this child a younger and smaller version of her mammy-troped mother. This lack of care is important, and Neal A. Lester comments on this commonplace violence towards this Black child in this story:

Graham is more interested in the joke of Pinky Marie’s pain and adultification by forcing her, at least visually, into a one-dimensional stereotypical mammy role. The source of the humor, then, is having a Black girl experience a traumatic event, denying her the ability to act out her emotions and connecting her with adulthood. The lack of care for the pain and emotions that the Black girl is experiencing in the meme and this children’s book is itself a form of anti-Black violence. Rebecca Epstein explains this common adultification of Black girls:The narrative’s solution to this trauma is to give Pinky Marie a bandanna to wear, making her a younger embodiment of her Mammy mother: her Pappy “pulled out his big red-and-blue-and-green hanky and tied it around Pinky Marie’s scrumbled-scrambled, kinky, wooly head just like Mrs. Washington Jefferson Jackson tied hers. And then he said, ‘There you is, honey. You looks fine again’” (n.p.). The adult “father” birds’ violently forcing this young girl into womanhood is similar to the many narratives of the sexual and other types of “adultification” of Black girls in contemporary times. (Lester 2022)

Casting Black girls into adult situations means that they are not granted the grace of presumed childhood innocence that white children and white people inherently and automatically receive. In these instances, adult creators and adult audiences turn a Black girl child’s pain and suffering into a spectacle for adult entertainment and amusement.Beginning as early as 5 years of age, Black girls were more likely to be viewed as behaving and seeming older than their stated age; more knowledgeable about adult topics, including sex; and more likely to take on adult roles and responsibilities than what would have been expected for their age. (Epstein et al. 2017)

The success of US minstrelsy and digital blackface relies on emotion and dialect, which correlates to both Pinky Marie and the “Crying Black Girl.” The meme stereotypes Black people and dehumanizes Black people for comedy. InJeong Yoon’s analysis of internet memes associated with racism explains this connection between meme creation and circulation and systemic racism:

The comedic content of both this meme and picture book denies Black children a full range of emotions by ignoring them altogether or making light of their pain. This one-dimensional blurred minstrelsy mammy/pickaninny image appears across multiple anti-Blackness children’s texts, among them Pickaninnies Little Redskins (1910), wherein the rhyme asks: “Mammy, mammy, I love you so,/What shall I do when I shall grow,/Too big, this tired head to rest/In slumber on they kindly breast?” A later page shows two Black children in a kitchen anxiously waiting: “On a griddle mammy bakes” (np). Thus, the cycle of societal and historical subservience for Black women and Black girls continues this minstrel interconnected representation between mother and young daughter.The Internet is one of the few sites where racist humor can be accessed and shared without being censored…. [Internet memes can provide] a critical understanding of how race matters, how racism works, and how issues around race and racism affect people’s lives …. Even if the intention of these memes is satirical, they function to create a space where people can mock and ridicule people of color. Furthermore, racial and ethnic humor should not be discussed in terms of the speaker’s intentions, but with regard to its impact on people of color and the whole society. (Yoon 2016, pp. 93–94, 109)

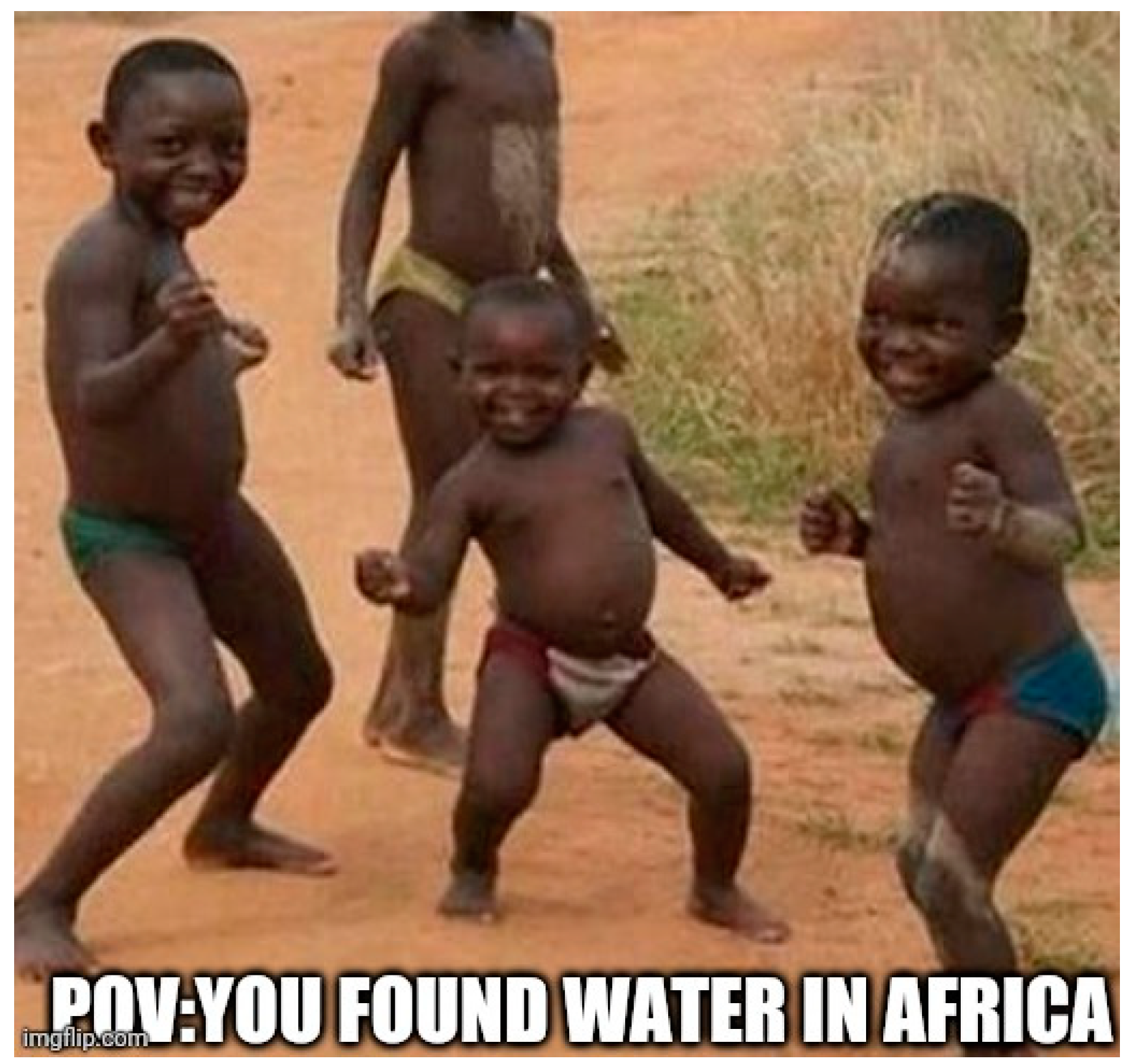

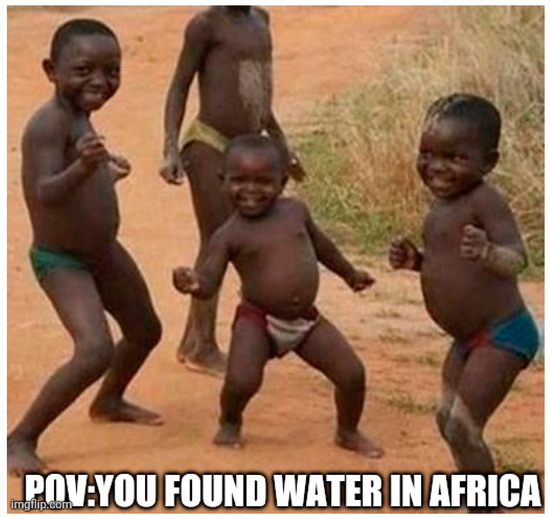

3.3. “African Kids Dancing” and Ten Little N***er Children

The “African Kids Dancing” meme showcases four- to six-year-old Black children dancing on an arid plain in their underwear. This state of undress connects Black children with racist stereotypes of Blackness as the antithesis of civilization, decorum, and humanity. Having no visual gender marker in the meme indicates that the Black children have no distinct identities beyond their pickaninny identity in a white world. Making these Black children appear less human and more like wild animals that do not wear clothes is part of the humor and the racial Othering. The imagery of genderless naked Black children dancing employs elements of the common pickaninny child caricature in US antebellum popular culture and in both antebellum adult and children’s literature:

This combination of smiling, dancing, and bug-eyeing is a visual minstrel performance in this meme. The imagery of dancing Black children is also part of the quaint appeal of the children’s book Kinky Kids (1908), wherein the Black children dance much like the Black adults who are footloose and fancy-free with not a care in the world: “Way down South in the land of cotton/… That’s where the little darkie children/Play all day in the sun;/Dancing, singing, eating, sleeping, My! But they do have fun” (np). Again, these images intersect with the historically racist stereotypes of Black adults as simple, close-to-nature, animalistic, irresponsible, and prone to little more than watermelon eating and being controlled by their carnal pleasures and self-gratification (Figure 3).Picaninny [children] … have big, wide eyes, and oversized mouths—ostensibly to accommodate huge pieces of watermelon. The picaninny caricature shows black children as either poorly dressed, wearing ragged, torn, old and oversized clothes, or, and worse, they are shown as nude or near-nude. This nudity suggests that black children, and by extension black parents, are not concerned with modesty. The nudity also implies that black parents neglect their children. A loving parent would provide clothing. The nudity of black children suggests that black people are less civilized than whites (who wear clothes). The nudity is also problematic because it sexualizes these children. Black children are shown with exposed genitalia and buttocks—often without apparent shame. (Pilgrim 2000)

Figure 3.

“African Kids Dancing” meme features four scantily-clad young Black children dancing in an arid outdoor space.

Along with the imagery, this caption, “POV:YOU FOUND WATER IN AFRICA,” points to the colonization of Africa, which led to resource scarcity, especially water. According to the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), “while three out of four people worldwide used safely managed drinking water services in 2020, regional coverage ranged from 96 per cent in Europe and Northern America to just 30 per cent in sub-Saharan Africa.” Data show how scarce clean drinking water still is in parts of Africa, so finding water for Black children and adults might be a joyous occasion due to water insecurity. Here, however, the joyous occasion is but the source of adult humor and Black children’s mockery. Francesca Sobande points out:

The digital commodity is humor at the expense of Black children’s complicated lives and experiences. As such, this meme furthers the adultification of Black children.On many occasions photographs and videos of Black people, sometimes in distress, have been used as part of the creation of a Graphics Interchange Format (GIF). These GIFs are commonly intended to be humorous but may be used in ways that involve complete disregard of the original context in which such Black people are depicted and indicate much disinterest in their possible upset in response to images of them being remixed in this way. Such digital activity can involve a Black person’s mannerisms, facial expressions, image, and overall humanity being treated as though it is nothing more than a mere digital commodity and means to communicate online. (Sobande 2021)

Nora Case’s Ten Little N***er Boys and Ten Little N***er Girls (1962) is a counting book for children using the historically and present-day racially derogatory and inflammatory n-word. In this children’s book used as a white adult’s teaching tool, Black boys are added to this narrative one by one in dehumanizing ways, while the Black girls in the second half of the book are taken out of the story in violent ways. The Black boys’ story shows how each Black boy is added to the group as they begin their day: “One little n***er boy/ Putting on his shoe. Sambo comes to help him,/ And then there are two” (Case 1957, pp. 7–8). The name “Sambo” connects this tar-black imaged Black male child to Helen Bannerman’s popular children’s book Little Black Sambo (Bannerman 1899), wherein a little Black boy, Sambo, is threatened by three hungry tigers as he strolls alone happily through a jungle in his new clothes. Case shows the boys doing rather arbitrary activities: rowing out to sea to save a drowning friend, diving into a water hole, sitting by a lake and almost being strangled by a snake, learning how to skate, marching in a line and being tripped, chasing a chicken. That they are called “naughty” has no logical justification or explanation as they mostly do good deeds. However, in the world of US minstrelsy, narratives do not rely on logic and rationale as these characteristics are reserved for white people: “Nine little n***er boys,/ Naughty little men,/ Chasing chicken round the yard/ And calling number ten” (Case 1957, p. 24). Randomly calling the boys “men” pushes at adultification. At the end of the story, the Black boys are little more than “Ten little n***er boys,/ In deep disgrace, you see/ Sent to bed at five o’clock/Without any tea./...Naughty little n***er boys/ Sleep well, good night” (Case 1957, p. 27). The language and minstrel imagery of the exaggerated red lips, bulging eyes, and coal-black skin make a humorous interaction of pain, struggle, and unwarranted chastisement of a white child’s math education and entertainment.

The Ten Little N***er Boys is Nora Case’s educational companion to Ten Little N***er Girls, using violent imagery to teach white children how to subtract. The book starts differently from the Boys book: “Ten little n***er girls/ Dressed so fine” (Case 1957, p. 31). The girls are given a degree of modesty and grown-up class in their dress. The story continues a similar plot as the Ten Little N***er Boys by showing the girls engaging in gendered labor and having them do household tasks: “Five little n***er girls/ Scrubbing the floor,/ One says she’s tired of it,/ And then there are four” (Case 1957, p. 43). The continuous disappearance of the girls is violent even in their everyday play: “Nine little n***er girls/ Swinging on a gate,/ One turns a somersault,/ And then there are eight” (Case 1957, p. 35). The violence is also in the girls’ playing with or interacting with nature and animals:

Six little n***er girls/ Playing near a hive,/ A honey-bee stings one/ And then there are five./… Four little n***er girls/ Taking their tea,/ A bird flies away one/And then there are three./ Three little n***er girls,/ Went to the Zoo,/ The polar bear hugs one/ And then there are two./ Two little n***er girls/ Paddling in the sun,/ A big fish feels hungry/ And so there is one. (Case 1957, pp. 42–48)

Even within the narrative, the author-orchestrated physical violence is shocking to the girls as their eyes are bulging and their mouths agape, further connecting them with US minstrelsy visuals. Like the Pinky Marie story above, this story also involves a Black girl’s violent attack by birds. The Black girls’ fear of violently dying here makes for a comic ending for the last Black girl left: “One little n***er girl/ Safe home once more,/ ‘Dear Dinah let me in,/ And shut fast the door’” (Case 1957, p. 51). The fear is apparent with the final girl fleeing and being left alone, unlike the boys, who safely get into the room and fall asleep together. The carnage the Black girls experience is cyclical as the book closes: “Only the cabin,/ No one about,/ Wait till the morning/ And they’ll all come out” (Case 1957, p. 52). The ending normalizes violence against and even the death of Black children for adult humor and the education of white children. Using illustrator Inez Hogan’s same crude and grotesque blackface images as in Epaminondas and His Auntie, Anne Christopher’s Petunia Be Keerful (Christopher 1934) makes Epaminondas and Petunia twin siblings in their constant mistakes and inability to understand adult instructions. Aside from the exaggerated minstrelsy language created to Other, to mock, and to elicit white adult and child humor at a Black girl’s expense, Christopher choreographs similar verbal abuse of a child by a Black family member. For her honest childhood mistakes, the child meets with these degrading adult responses: “You no ‘count chile”; “You is powerful dumb, Petunia Brown…”; “What de name ‘er goodness is you got eyes fo’?; and “Lawsy mussy … You is de stupidest black chile I’se eber done see” (np).

“African Kids Dancing” connects to Ten Little N-word Boys through adultification. Even though their alleged environmental circumstance is violent—draught and barrenness—they frolic with no care in the world. The meme and children’s stories deny Black children’s humanity while demanding that they grin and bear any potential hardships. Such historical and modern-day racial representations and misrepresentations collapse the differences associated with Black adults and children, dangerously engaging and treating Black children as adults.

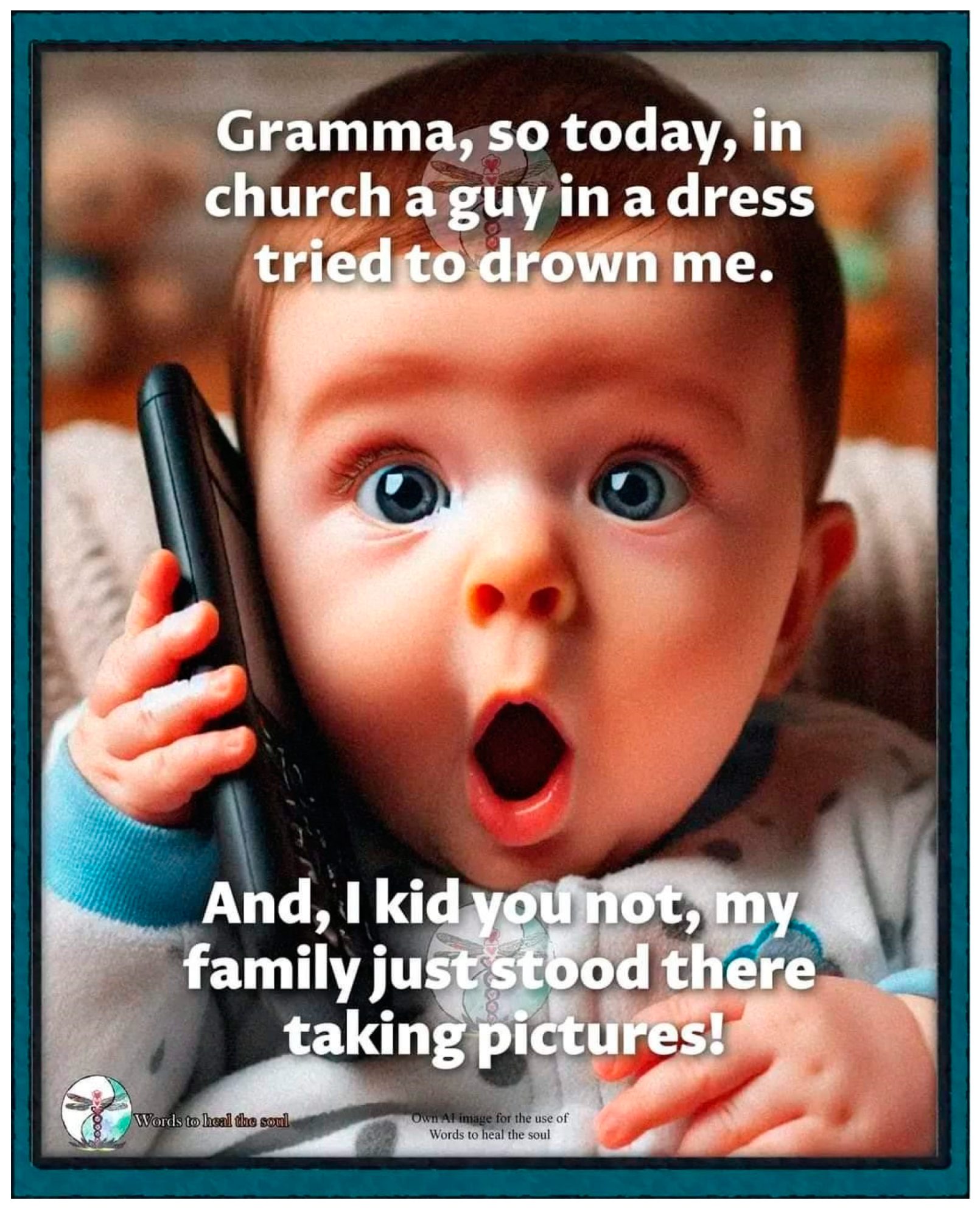

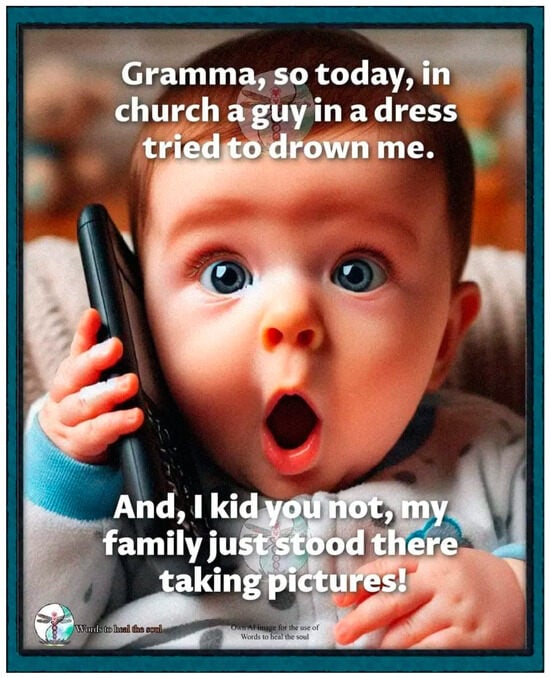

4. Not Allowing Black Children to Be Children

The adultification of Black children connects digital blackface in memes with the misrepresentation and mockery of early racist children’s books that center on US minstrelsy. While historical US minstrelsy was primarily created by and for white audiences and performed primarily by white actors in blackface, digital blackface crosses racial lines. The problem with crossing racial lines is that it expands and makes people, regardless of race, complicit in adultifying, dehumanizing, and ultimately endangering Black children. We fully acknowledge that such adultification also happens to white children in memes used for adult humor and emotion (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

This humorous meme featuring a white infant using a cell phone to call a family member contrasts memes that mock Black children as racist adult humor.

While having the white child above with bulging eyes and mouth agape is also a source of adult humor, this white infant child is fully clothed and protected as they are narratively making a call, presumably to an adult, about their safety within a “civilized” Christian church ritual. Contrastingly, memes that thrust Black children into adult circumstances and situations make Black children part of the adult world of anti-Black violence and mockery with little to no adult protection or care. In addition, no long and multilayered US history reduces white children or denies them of their fundamental humanity and dignity. Memes about Black children amplify the larger problem of anti-Blackness and global white supremacy from which Black children and Black adults are not exempt. While meme captions change from creator to creator depending on a creator’s purpose and intent, nothing historically changes the static image and its accompanying attitudes and beliefs about the inferiority of Black children and Black adults. Yoon—whose 2016 study revealed that of all racial and ethnic groups memeified, African Americans were memeified significantly more than American Indians, Asians, Jewish people, Mexicans and Mexican Americans, Muslims, and White people (Yoon 2016, p. 106)—validates our critical concerns and social alarm that continue from early racist children’s books to the rapidly circulated and consumed digital manifestations of anti-Blackness using Black children:

Internet memes on racism should be investigated as a site of ideological reproduction. Popular discourse including humor is an ideal lens through which to examine how everyday interaction and social dynamics are influenced by ideology and the social structure. … Internet memes impact people on the macro level in that they shape people’s mindsets, forms of behavior, and actions, despite that they are spread on a micro basis. (Yoon 2016, pp. 93, 96)

Our effort here has not been to assess the success of memes based on digital engagement through likes and shares. Similarly, we have not spent time and attention trying to track down more specific demographic details about who bought, read, and shared these books that are still in public circulation. Nor do we make any effort to hypothesize about a more specific demographic who reads the books or receives and responds to these memes. For us, the very existence of these texts as cultural artifacts substantiates our position that both formats are indeed racially and socially problematic for Black people who know that Barack Obama’s ascendancy to the US presidency did not bring about the alleged post-racial society and for non-Black folks who only see racism in overt confrontational ways. As Tabitha Fairchild contends:

Hence, these books and digitization make it easier and more palatable to practice, perpetuate, and sustain global anti-Black bias manifested in racial discrimination and continued social injustice.Digitally, internet memes are widely used rhetorical vehicles, reaching large and broad audiences. The roles these artifacts play in the reproduction and transmission of racist ideology is often obfuscated by the perception that internet memes are “just jokes”. …Memes act as mechanisms through which culture in its various forms is produced, disseminated, and reproduced. Digital spaces often function as mechanisms through which the culture of society at large is reproduced resulting in a digital world that mirrors the oppressions of the real world. Digital social platforms create new spaces and methods for discussions where the stereotypes and racial biases of the physical world are often reified, an issue that may potentially be exacerbated as the divide between our digital and corporeal identities grows thinner. (Fairchild 2020, pp. 2–3)

Author Contributions

Writing—review and editing, C.F. and N.A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

We have used no such datasheets for this piece.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | See Maryclaire Dale’s story of the exonerated 16-year-old Alexander McClay Williams, the youngest person in Philadelphia executed in 1931 for allegedly stabbing to death a white woman (Dale 2024). |

| 2 | Fourteen-year-old George Stinney, Jr. was executed in South Carolina, allegedly for killing two young white girls in 1944. See (Fourteen-Year-Old George Stinney Executed in South Carolina n.d.). |

References

- Baker, Augusta. 1975. The Changing Image of the Black in Children’s Literature. Horn Book, February 1, 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bannerman, Helen. 1899. Little Black Sambo. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, Ruha. 2019. Race after Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, John. 2023. Analysis: What’s ‘Digital Blackface?’ and Why Is It Wrong when White People Use It? CNN, Cable News Network. March 26. Available online: www.cnn.com/2023/03/26/us/digital-blackface-social-media-explainer-blake-cec/index.html (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Bryant, Sara Cone. 1976. Epaminondas and His Auntie. New York: Buccaneer Books. [Google Scholar]

- Burroughs, Margaret. 1963. “What Shall I Tell My Children Who Are Black (Reflections of an African American Mother”. Poetry Foundation. Available online: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/146263/what-shall-i-tell-my-children-who-are-black-reflections-of-an-african-american-mother (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Case, Nora. 1957. Ten Little N****er Boys and Ten Little N***er Girls. London: Chatto & Windus. [Google Scholar]

- Christopher, Anne. 1934. Petunia Be Keerful. Atlanta: Whitman Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Dale, Maryclaire. 2024. Family of Black Philadelphia Teen Wrongly Executed in 1931 Seeks Damages after 2022 Exoneration. WHYY.Org, May 20. [Google Scholar]

- Day, Naomi. 2020. Reaction Gifs of Black People Are More Problematic than You Think. Medium. June 3. Available online: https://onezero.medium.com/stop-sending-reaction-gifs-of-black-people-if-youre-not-black-b1b200244924 (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Durham, Anissa. 2022. What You Should Know About Adultification Bias. USC Center for Health Journalism. Available online: https://centerforhealthjournalism.org/our-work/reporting/what-you-should-know-about-adultification-bias (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Epstein, Rebecca, Jamilia Blake, and Thalia González. 2017. Girlhood Interrupted: The Erasure of Black Girls’ Childhood. June 27. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3000695 (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Fairchild, Tabitha. 2020. It’s Funny Because It’s True: The Transmission of Explicit and Implicit Racism in Internet Memes. Richmond: Virginia Commonwealth University Graduate School Theses and Dissertations. [Google Scholar]

- Fourteen-Year-Old George Stinney Executed in South Carolina. n.d. A History of Racial Injustice. Available online: http://calendar.eji.org/racial-injustice/jun/16 (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Gallon, Kim. 2016. Making a Case for the Black Digital Humanities. In Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016. Edited by Matthew K. Gold and Lauren F. Klein. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goff, Phillip Atiba, Matthew Christian Jackson, Brooke Allison Lewis Di Leone, Carmen Marie Culotta, and Natalie Ann DiTomasso. 2014. The Essence of Innocence: Consequences of Dehumanizing Black Children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 106: 526–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrnstein, Richard J., and Charles A. Murray. 1994. The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, Elvin. 1986. A Coon Alphabet and the Comic Mask of Racial Prejudice. Studies in American Humor 5: 307–18. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Lauren Michele. 2017. We Need to Talk About Digital Blackface in Reaction GIFs. Teen Vogue. August 2. Available online: www.teenvogue.com/story/digital-blackface-reaction-gifs (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Jardim, Suzane. 2016. Recognizing Racist Stereotypes in U.S. Media. Medium. August 4. Available online: https://medium.com/@suzanejardim/reconhecendo-esteri%C3%B3tipos-racistas-internacionais-b00f80861fc9 (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Jones, Ellen E. 2020. Why Are Memes of Black People Reacting so Popular Online? The Guardian. June 12. Available online: www.theguardian.com/culture/2018/jul/08/why-are-memes-of-black-people-reacting-so-popular-online (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Lester, Neal A. 2022. Black Children’s Lives Matter: Representational Violence against Black Children. Humanities 11: 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohdin, Aamna. 2022. ‘They Saw Me as Calculating, Not a Child’: How Adultification Leads to Black Children Being Treated as Criminals. The Guardian. July 5. Available online: www.theguardian.com/society/2022/jul/05/they-saw-me-as-calculating-not-a-child-how-adultification-leads-to-black-children-being-treated-as-criminals (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Morganthau, Tom. 1994. Is It Destiny? An Angry Book Ignites a New Debate over Race, Intelligence and Class. Newsweek, October 24, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Parish, Peggy. 1963. Amelia Bedelia. New York: Harper & Row Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Pilgrim, David. 2000. The Picaninny Caricature: Anti-Black Imagery. Jim Crow Museum. Available online: https://jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/antiblack/picaninny/homepage.htm (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Riggs, Marlon. 1987. Ethnic Notions. Berkley: California Reel. [Google Scholar]

- Selby, Daniele. 2020. From Emmett Till to Pervis Payne: Black Men in America Are Still Killed for Crimes They Didn’t Commit. Innocence Project. Available online: https://innocenceproject.org/emmett-till-birthday-pervis-payne-innocent-black-men-slavery-racism/ (accessed on 15 April 2024).

- Sobande, Francesca. 2021. Spectacularized and Branded Digital (Re)presentations of Black People and Blackness. Television & New Media 22: 131–46. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Amanda. 2016. Racial Microaggressions and Perceptions of Internet Memes. Computers in Human Behavior 63: 424–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Injeong. 2016. Why Is it Not Just a Joke?: Analysis of Internet Memes Associated with Racism and Hidden Ideology of Colorblindness. Journal of Cultural Research in Art Education 33: 92–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).