Abstract

Influenced by Hegel, modern Chinese philosophers (e.g., Mou Zong-San, Lao Sze-Kwang, etc.) and Japanese philosophers (e.g., Nishida Kitaro) were inclined to narrate Chinese or Japanese culture in terms of the Hegelian concept of ‘spirit’. Nevertheless, the Hegelian philosophy of culture assumes the existence of an unchangeable cultural spirit and was therefore criticised by Watsuji Tetsuro. Watsuji denies the existence of an unchangeable cultural spirit and argues that cultures arise from the aidagara (interactions) between Ningen (human society) and Fudo (nature). Yet Watsuji’s narration of culture overemphasised the aidagara between Ningen and Fudo but disregarded that culture may also arise from the aidagara among cultures. Therefore, by reinterpreting Watsuji’s concept of aidagara, this paper proposes the concept of Bungen to explain the formation of cultures in terms of intercultural interactions and therefore highlight the diversity of East Asian cultures.

1. Introduction

Facing the challenges of Western civilisations and modernisation, Chinese and Japanese philosophers were concerned with the philosophy of culture since the nineteenth century. Their research on the philosophy of culture focuses on the epistemic question of ‘What is our own culture?’ and the ontological question of ‘How can we formulate our cultural subjectivity?’ (Tam 2020a, p. 14).

To answer these two questions, these philosophers narrated their cultures and preserved certain values they prioritised as the foundation of their cultural subjectivities. Influenced by Hegel’s dialectics, the majority of Chinese and Japanese philosophers of culture define cultures in terms of spirit. According to Hegel, the ‘essence of spirit … is self-consciousness … [In other words,] the nations are the concepts which the spirit has formed of itself. Thus, it is the conception of the spirit that is realised in history.’ (Hegel 1995, p. 51). Hegel’s concept of spirit was adopted by Chinese and Japanese philosophers of culture who argued that their cultural spirits are distinguished from the Western cultures. (Tang 2015) (Nishida 1998).

These East Asian Hegelians could be identified as essentialists because they define culture in terms of certain essential cultural values or spirits. According to Ghaffour, ‘for essentialists, culture is deemed a homogeneous group … despite scholars acknowledging diversities within nations, they are still bound to the fixed, determined cultural identity, contradictory and essentialist-like.’ (Ghaffour 2022, p. 275).

Yet the Hegelian assumption of the existence of the unchangeable cultural spirit is questionable. According to Tam, there are three more problems in essentialism: ‘(1) the impossibility of changes in cultural values, (2) the lack of an empirical method to identity cultural spirit and (3) the neglect of openness of value interpretation.’ (Tam 2020a, p. 187). Remarkably, (2) and (3) are inevitable weaknesses in essentialism because essentialists were inclined to arbitrarily regard certain values as essential values defining a cultural spirit with no empirical evidence. Neither Tang nor Nishida undertook fieldwork to verify that the cultural activities in China or Japan expressed the essential values (Confucian concept of humanness or Buddhist concept of non-Being) they indicated. To overcome these weaknesses, Tam introduced Kierkegaard’s concept of culture in terms of the manifestations of passions and argued that philosophers should examine how cultural activities manifest different kinds of passions to identify the essential values of a culture. ‘It is not one particular value or one spirit that determines the cultural development; instead, it is the passions for certain values which drive the cultural development.’ (Tam 2020a, p. 284). Although Tam correctly pointed out the need for a paradigm shift of East Asian philosophy of culture from the Hegelian model to something else, Tam did not apply his theory to address the concept of cultural hybridity and intercultural interactions, which are highlighted by non-essentialists.1

For non-essentialists, ‘cultures are not homogeneous but rather heterogeneous, changing, and dynamic.’ (Ghaffour 2022, p. 275). ‘All cultures are dynamic and constantly change over time due to political, economic, and historical events and developments resulting from interactions with and influences from other cultures. Cultures also change over time because of their members’ internal contestation of their meanings, norms, values, and practices.’ (Byram et al. 2013, p. 15). In this sense, non-essentialists or transculturalists reject not only the existence of unchangeable cultural spirits but also essential cultural differences because they claim that all cultures are essential hybrid, fluid and impermanent.

Yet non-essentialists’ radical rejection of cultural differences has several theoretical problems. Firstly, non-essentialists failed to defend East Asian cultures from the threats of cultural assimilation because they denounced cultural differences. Facing the threat of Imperialism in the nineteenth century and Communism in the twentieth century, East Asian philosophers, remarkably New Confucians, were devoted to demonstrating the worthiness of preserving traditional East Asian cultures by arguing for the essential differences between the East and the West and the impossibility of forcing East Asians to adopt the ‘Western’ ideologies (Capitalism, Communism, etc.). Because non-essentialists believe that all cultural differences are relative, theoretically speaking, all cultures can be assimilated into one single culture, and they do not explicitly propose any normative argument against cultural assimilations. Secondly, non-essentialists only indicate the ‘hybridity’ of cultures but fail to explain why some values were adopted while others were rejected in the process of intercultural dialogues. One may wonder whether the choices of values involve normative judgments rather than merely irrational xenophobia or exclusivism.

This paper examines the limitations of modern Chinese and Japanese philosophers of culture who defined culture in terms of spirit, introduces Watsuji Tetsuro’s definition of culture as the aidagara (interactions) between Fudo (nature) and Ningen (human society), and proposes the concept of Bungen (文間, literally means the betweenness among cultures)2 as aidagara among cultures. This paper argued that cultures are not only conditioned by the aidagara between Fudo and Ningen but also by intercultural interactions because in every culture there is a ‘Thou in I’ and ‘I in Thou’ where values permeate one another. Each culture connects different values through different Bungen, which form a set of cultural values. Every culture decides which values to be accepted or rejected according to its prioritised values. Here prioritised values become normative principles determining the inclusiveness and exclusiveness of a culture. By proposing the concept of Bungen, this paper provides an alternative philosophy of culture to both essentialism and transculturalism.

2. Literature Review: The Problem of Essentialism and Transculturalism

In A Manifesto on the Reappraisal of Chinese Culture (1958), New Confucians like Tang Jung-yi and Mou Zong-san defined the Chinese Cultural spirit in terms of mind-nature theory and distinguished the Chinese culture from Western culture accordingly (Tang 2015, pp. 139–44). As they claimed:

Chinese culture arose out of the extension of primordial religious passion to ethico-moral principles and to daily living. For this reason, although its religious aspects have not been developed, it is yet pervaded by such sentiments and hence is quite different from occidental atheism. To comprehend this, it is necessary to discuss the doctrine of “hsin-hsin” (concentration of mind on an exhaustive study of the nature of the universe), which is a study of the basis of ethics and forms the nucleus of Chinese thought and is the source of all theories of the “conformity of heaven and man in virtue.”(Chiang 1962, p. 461)

Similarly, the Kyoto school philosopher Nishida Kitaro defined the Japanese cultural spirit in terms of non-Being and distinguished it from the Western cultures, which are based on the ontology of Being (Nishida 1998, p. 21).

However, in the twentieth-first century, the cultural narrations suggested by New Confucians and the Kyoto school philosophers are criticised for essentialism as they one-sidedly highlighted differences in cultural values. Fabian Heubel argued that A Manifesto on the Reappraisal of Chinese Culture expressed the ‘cultural essentialism of New Confucianism’. (Heubal 2009, p. 135). ‘The modern ideology of cultural essentialism and nationalism often distinguishes self and other and therefore can hardly acknowledge cultural diversity and hybridity. They lead to different levels of “cultural schizophrenia”.’ (Heubel 2008, p. 186). Heubel even proposed to replace the term ‘Chinese philosophy’ with the term ‘Hanyu (Chinese languages) philosophy’ because the term ‘Chinese’ assumed the concept of a ‘Chinese nation’ while Hanyu did not (Heubel 2008, p. 187). Influenced by Heubel, Cheung Ching-yuen also criticised Nishida for cultural essentialism. Cheung argued that Nishida ‘inaccurately explains the characteristics of the Japanese culture in terms of the purity of “blood”.’ (Cheung 2017, p. 108). To contrast with the essentialism of New Confucianism and the Kyoto school, one may identify the philosophy of Cheung and Heubel as transculturalism or non-essentialism.

A similar criticism of Chinese cultural essentialism is also found among Catholic interpreters. For instance, Dorottya Nagy warned about the danger of “Chinese national essentialisation” underlying the Christian Sinicization proclaimed by the CCP regime. She argued that Christian Sinicization assumed a CCP acknowledged “essentialised Chineseness” that Christianity must conform to. “In this sense the patriotic propaganda within the PRC and the nationalist rhetoric including but going beyond the PRC build up the same kind of Christianity: an essentialised one, which easily leads to what can be called nationalistic Christianity or Christian nationalism.” (Nagy 2010, p. 80). Yet non-essentialists may also criticise that the Catholic’s criticism of Chinese essentialism also assumed Christian essentialism: because Catholic theologians insisted that certain essential doctrines could not be compromised with the so-called essentialised Chineseness, they deny the essentialised Chineseness so that they could flexibly convert Chinese culture into a culture conforming to essential Catholic doctrines.

Nevertheless, there is also a weakness in non-essentialism: their one-sided emphasised the diversity and hybridity of cultural values but failed to explain according to which principles were values related to one single culture. In Cheung’s lecture on An Introduction to the Philosophy of Culture at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 2013, when Cheung proposed his trans-culturalism and was challenged by the question above, Cheung argued that both Chinese and Japanese cultures are diverse and mixed, like different brands of cokes with varying levels of sugar content or even sugar-free. Likewise, cultural differences are only differences in the proportion of value components. However, the different components of Coke are connected by specific chemical bonds. For example, carbonic acid is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula H2CO3, which contains hydrogen, carbon, and oxygen. One may wonder if there is any principle that synthesises different values into a single culture.

One may use the concept of mixture and compound in chemistry as an analogy to discuss the relationship between cultures and values. A compound refers to a substance in which two or more elements are bonded together in a fixed ratio through a chemical bond, while a mixture refers to a substance composed of two or more pure substances (elements or compounds) that are mixed without undergoing a chemical synthesis. If values were regarded as the elements of a culture, one may wonder whether a culture is a ‘compound’—where various values are synthesised according to certain principles, or a ‘mixture’—where various values coexist without being governed by any principle.

While Cheung did not provide a straightforward answer, he seemed to assume cultures as compounds and tried to find out the principles of synthesising values. These principles must be confining and normative and therefore exclusive to a certain extent to determine whether some values belong to a culture while others do not. Yet Cheung only highlighted the openness of cultural principles and disregarded exclusiveness. Cheung argued that ‘although Nishida said I and Thou are different, both share the same medium.’ (Cheung 2017, p. 110)3. Accordingly, Cheung formulates a hybrid Japanese culture with the help of Nishida’s theory of otherness: ‘The Japanese culture is not purely Japanese but is a hybrid culture containing others. … There is a Thou in I and an I in Thou. As a “transcultural philosophy”, Nishida’s “I and Thou” avoided his doubts over “hybridity” and asserted the potential of thoughts on hybridity.’ (Cheung 2017, p. 112). Yet one may immediately ask: why is there only a ‘Thou’ in I but not ‘he’, ‘she’ or ‘it’? For example, the Chinese theologian Zia Nai-zin realised that after one thousand and three hundred years, traditional Chinese culture and Christianity ‘had only lived together unwillingly without marriage, and therefore they never gave birth to good fruits.’ (Zia 1980, p. 14). Here Zia realised the problem of cultural exclusiveness. Yet Zia did not eliminate exclusiveness; instead, to overcome exclusiveness, he emphasised the ‘sameness’ of Confucianism and Christianity in the problem of ‘the unity of Heaven and Humans’ to overcome the ‘differences’ between the two traditions (Zia 1980, p. 62). Likewise, when Japanese theologians were struggling with the exclusion of Christianity in Japanese culture, Ebina Danjo proposed his controversial theology of ‘purifying Shinto’ where he tried to reinterpret Shinto myths in terms of the Christian doctrines (Furuya et al. 2002, p. 14).

By contrast, owing to Cheung’s perspective on the differences and sameness between the self and others, Cheung did not acknowledge the exclusiveness of cultural principles. Cheung said: ‘Different from comparative philosophy (which asserts the “differences” between the self and others) or the intercultural philosophy (which asserts the “sameness” between the self and strangers), transcultural philosophy highlighted “the differences in the commonness” between the self and others.’ (Cheung 2017, p. 112). Because exclusiveness only highlights differences, transcultural philosophy can hardly assert exclusiveness. Yet when a culture has no exclusive principle and accepts any values indiscriminately, the differences in values between cultures no longer have a reason to exist. Chinese culture can readily accept all Western values and be completely Westernised, which poses a risk to global cultural homogenisation. In the end, a mere emphasis on cultural hybridity and a disregard for exclusiveness failed to acknowledge cultural differences. When ‘differences’ cease to exist, the transcultural philosophy of “the differences in the commonness” is reduced to the intercultural philosophy that asserted the commonness one-sidedly.

In short, while essentialists one-sidedly emphasised cultural differences, non-essentialists one-sidedly asserted cultural sameness. To overcome their weaknesses, the following section introduces Watsuji’s definition of culture in Fudo (1935) and explores a cultural principle that is both inclusive and exclusive.

3. Culture as the Aidagara Between Fudo and Ningen and the Meaning of Aidagara

To understand Watsuji’s philosophy of culture, one must understand his concepts of aidagara, Ningen, and Fudo in advance. Aidagara 間柄 is a daily word in Japanese that means kinship or interactive relationship. Watsuji’s usage of the term refers to the second meaning: aidagara refers to the

act-connections between person and person, like communication or association, in which persons as subjects concern themselves with each other. We cannot sustain ourselves in any aida or naka implying a living and dynamic betweenness as a subjective interconnection of acts. A betweenness of this sort and the spatio-temporal world combine to produce the meaning conveyed by the words se-ken (the public) or yo-no-naka (the public).(Watsuji 1996, p. 18)

We described ningen, which possesses this dual structure, as something subjective. The implication is that ningen, although being subjective communal existence as the interconnection of acts, is, at the same time, an individual that acts through these connections. This subjective and dynamic structure does not allow us to account for ningen as a ‘thing’ or ‘substance’. Ningen cannot be thought of as such apart from the constantly moving interconnection of acts.(Watsuji 1996, p. 19)

From Watsuji’s perspective, Ningen is not a Being or substance in the sense of Western philosophy because it is not an entity. Watsuji used the term Sonzai 存在 to grasp the impermanence of Ningen. ‘Son … is on every occasion capable of changing into “loss”. That is to say, it is son of sonbo [存亡] (‘‘maintenance and loss”).’’ (Watsuji 1961a, pp. 20–21).

Further, Ningen sonzai is not merely about social relationships; instead, it is the duality of individuality and sociality. Merely highlighting sociality and disregarding individuality would be considered as being one-sided by Watsuji, for he said:

With regard to the term ningen, which is characterised by yononaka and at the same time by hito (i.e., an individual human being), we call the character of yononaka the social nature of ningen, on the one hand, and that of hito the individual nature of ningen, on the other.(Watsuji 1996, p. 19)

Based on the concept of Ningen sonzai, Watsuji further criticised Heidegger’s concept of Dasein for disregarding both the duality of individuality and sociality. Watsuji said:

The togetherness of one Dasein with another can arise only with that space in which our relational concerns with such things as tools take place. What is the field in which two Dasein coexist? This field must also belong to the basic structure of sonzai. As we turn our eyes to this basic spatiality, we must simultaneously consider that temporality that breaks through the confinement of individual beings, and turns out to be constitutive of ningen sonzai.(Watsuji 1996, p. 20)

Watsuji argued that, unlike Dasein, which assumes the concept of substance (as independently existing entities), Sonzai implies the interdependent existence of both individuals and societies; in this sense, an individual existence assumes his/her coexistence with others in different kinds of aidagara.

Following Watsuji’s argument, one must acknowledge the multiplicity of aidagara constituting Ningen sonzai and categorise different kinds of aidagara accordingly. As mentioned above, in Watsuji’s reading of Mengzi’s idea of Gorin, the self manifests different consciousness in each interpersonal relationship. Likewise, Ningen sonzai manifests its different aspects when interacting with different others in different aidagara, e.g., human–land relationships and intercultural relationships. While these aidagara are interdependent, their emphases are different and should be discussed separately for clarity.4

However, based on the Kanji of aidagara 間柄, Watsuji seems to emphasise aida over gara in his writing. Watsuji only explains the meaning of aida in aidagara and Ningen, as well as his understanding of humanity, but never defines gara. Therefore, it is necessary to discuss the meaning of gara in this paper.

If aidagara merely refers to ‘betweenness’ and ‘interconnection’ (which are found in the kanji 間 aida), the kanji gara would be unnecessary. Yet in Classical Chinese, gara has several meanings: it may refer to handle, measure word, plant stem, material for joke, root, or power. In Watsuji’s context, only the last two meanings seem relevant. If gara means power, aidagara literally suggested that aida has the ‘power’ to determine the nature of society and individuals. Yet since such a deterministic statement may be against Watsuji’s philosophy, the sense of gara as power is left aside here. By contrast, the sense of gara as a root is more consistent with Watsuji’s philosophy: it implies that individuals and society come from aida. Aida has the ontological status of being an origin through the interpretation of gara above.

Watsuji’s understanding of Aidagara and Ningen comes from his reinterpretation of Mengzi’s concept of five relationships (gorin 五倫). As Tam indicates, in Rinrigaku, Watsuji reinterpreted Mengzi’s concept of five relationships in terms of aidagara to define ethics (rinri 倫理) as concrete interpersonal relationships—ruler and minister, father and son, husband and wife, brothers and friends (Tam 2020b, p. 149). In other words, Gorin formulates five aspects of the same human existence in Watsuji’s ethics. Similarly, Yang argued that ‘The kanji of “Jinrin” 人倫 must have normative senses. The first normative sense must be the “communion of humanity”, while the “five constants of human ethics” refer to five constant principles in the communion of humanity. In Watsuji’s sense, “communion” and “constant principles” are interchangeable … “communion” refers to rin, while “foundation of the existence of the communion” refers to ri.’ (Yang 2012, p. 403). Since Watsuji regarded ri merely as the normative principle governing interpersonal relationships, Yang argued that Watsuji emphasised Rin over Ri and rejected the idea of the Heavenly principle (tenri 天理) in the Cheng Zhu school of Confucianism (Yang 2012, pp. 403–4).

Watsuji deviated from Confucianism and reinterpreted rinri because he introduced the Buddhist notions of ‘emptiness’ and ‘no self’. He negated the existence of the self as a substance and believed that self-consciousness only arises from the aidagara of Jinrin. As Tam said, ‘Influenced by Buddhism, Watsuji claimed that self-consciousness arises from the integration of the five aggregates: form (rupa), sensations (vedana), perceptions (samjna), mental activity (sankhara), and consciousness (vijnana).’ (Tam 2022, p. 19)5. In other words, culture as self-consciousness arises from aidagara. As Watsuji argued:

… in our daily lives, we look at, doubt, or love a Thou. That is to say, ‘I become conscious of Thou.’ My seeing Thou is already determined by your seeing me, and the activity of my loving Thou is already determined by your loving me. Hence, my becoming conscious of Thou is inextricably interconnected with your becoming conscious of me. This interconnection we have called betweenness is quite distinct from the intentionality of consciousness. … [For] so far as betweenness-oriented [aidagara] existences are concerned, each consciousness interpenetrates the other. When Thou gets angry, my consciousness may be entirely coloured by Thou’s expressed anger, and when I feel sorrow, Thou’s consciousness is influenced by I’s sorrow. It can never be argued that the consciousness of such a self is independent.(Watsuji 1996, p. 69)

Intentionality refers to the ability of the mind to represent or manifest external objects. Yet Watsuji argued the aidagara consciousness of ‘I am aware of your anger’ is different from the intentional consciousness of ‘I am aware of a banana peel on the floor’, for the former involves the aidagara between different consciousnesses where individual self-consciousness arises. Ningen is the whole of Rinri formulated by such the aidagara.

Ye aidagara is not limited to interpersonal interactions; it can also refer to interactions between humans and nature. In Fudo, Watsuji proposed the aidagara between human society and nature: ‘When we feel cold, we ourselves are already in the coldness of the outside air. That we come into contact with the cold means that we are outside in the cold. In this sense, our state is characterised by “ex-sistere” as Heidegger emphasises, or, in our terms, by “intentionality”. … Therefore, in feeling the Cold, We discover ourselves in the Cold itself.’ (Watsuji 1961a, p. 3). Because all human societies interact with nature, Watsuji claimed that ‘there is no historical event that does not possess its climatic character, nor is there climatic phenomenon that is without its historical component.’ (Watsuji 1961a, p. 116).

To Watsuji, cultures are the aidagara between Ningen and Fudo. Fudo is defined as ‘ “wind and earth”, as a general term for the natural environment of a given land, its climate, its weather, the geological and productive nature of the soil, [and] its topographic and scenic features. …’ (Watsuji 1961a, p. 1). Yet Fudo is distinguished from natural environments because Fudo refers to how nature interacts with human beings. In the example of feeling cold, Fudo is not regarded as an object that exists independently but as the place (場所basho) where human beings discover themselves. ‘We can also discover climatic [Fudo] phenomena in all the expressions of human activity, such as literature, art, religion, and manners and customs. This is a natural consequence as long as man apprehends himself in climate [Fudo].’ (Watsuji 1961a, p. 8). When human society interacts with Fudo, a particular way of living and cultural consciousness is formed. As Watsuji said:

From the standpoint of the individual, this becomes consciousness of the body, but in the context of the more concrete ground of human life, it reveals itself in the ways of creating communities, presence consciousness, in the ways of consciousness, and thus in the ways of constructing speech, the methods of production, the styles of building, and so on. Transcendence, as the structure of human life, must include all these entities.’(Watsuji 1961a, p. 12)

Watsuji distinguished Fudo according to climatic features of temperature and humidity into three types: monsoon, desert, and meadow, which give birth to three kinds of cultures accordingly.

Nevertheless, Watsuji’s classification of Fudo departs from the original meanings of Fudo in Kanji. In Kanji, Fudo consists of two characters—Fu 風, which means wind or climate, and Do 土, which means earth or landforms. Yet in the Japanese context, Fudo does not refer to natural environments but a landscape influenced by human activities. Hence Fu in Fudo also means customs or fashion (Fuzoku 風俗). During the Nara period, the emperor Gemmei (661–721) commanded all states to write their own Fudoki 風土記 (records of wind and earth) in Classical Chinese. While most of these documents are lost, the standard structure of Fudoki is mentioned in Shoku Nihongi 続日本記: ‘the names and characters of all states, counties and prefectures in the region of Kinai; the silver, copper, coloured plants, trees, birds, beasts, fish, and insects that inhabit there, as well as the records of their colours and characteristics; the fertility of the land; the origins of the names of mountains, rivers, and plains; and stories and legends passed down from the ancient time.’ (Suganono et al. 1883, p. 53). In other words, Fudo includes not only the climate but also landscape and customs, yet Watsuji only focused on the climatic features when discussing Fudo. It seems that Watsuji emphasised Fu over Do.

It should be noticed that Watsuji’s Fudo study does not imply environmental determinism because Watsuji only claimed that ‘cultures result from the interactions between “our” Ningen and Fudo.’ (Tam 2022, p. 12). Fudo only conditions cultures. ‘When humans interacted with the same Fudo in different historical situations, there would be different outcomes of interactions that led to different ways of living.’ (Tam 2022, p. 12). Watsuji insisted that cultural consciousness is determined by humans’ free will. When discussing Herder’s study of Fudo, Watsuji argued that Herder was the first Western philosopher of culture who distinguished cultures from nature and asserted that the former is determined by free will. ‘“Nature” is what gave humanity reason and free will, and it desired that humans perform all actions that transcend their animal nature entirely voluntarily.’ (Watsuji 1961b, p. 223). Watsuji only argued that culture does not exist until it arises from the interactions between nature and society.

However, since Watsuji’s claim that aidagara between Fudo and Ningen pre-exists cultures is too strong, this paper suspends such a controversial ontological assumption. As mentioned above, Watsuji adopted the Buddhist notion of emptiness and no-self as well as the denial of substance and developed his philosophy of aidagara. Yet if such a radical Buddhist assumption was adopted, Watsuji’s philosophy of culture would be inapplicable to the non-Buddhist (remarkably Christian) philosophy of cultures, which assumed the concept of Being and substance. For example, Tillich claimed that ‘religion is the substance of culture, culture is the form of religion.’ (Tillich 1964, p. 42). Yet as Tam argued, ‘even if one denies the Buddhist claims that “the self is equivalent to self-consciousness” and “substance does not exist”, one may still restraint aidagara to explain the formation of a particular self-awareness or feeling.’ (Tam 2022, p. 355). Tam continued:

… from the perspective of Christian ontology represented by Kierkegaard, one has just discovered a particular self-consciousness of feeling cold in coldness but not the self as a whole. The ‘self-feeling cold’, the ‘self-feeling humid, the ‘self-feeling of British cuisine distasteful’ are irrelevant to each other, but they belong to the same individual self which is the self as a substance and as a whole.(Tam 2022, p. 355)

Therefore, while this paper adopts Watsuji’s concept of aidagara to examine how cultures are influenced by intercultural interactions, this paper suspends Watsuji’s ontological assumption of emptiness and no-self. Even if one believed that culture pre-exists the aidagara between Fudo and Ningen and among cultures, one may focus on how the concept of aidagara clarifies how a culture accepts or rejects external values when it interacts with another culture.

Based on the conceptual clarifications above, one may explore the origin of the normativity of cultural principles as well as their inclusiveness and exclusiveness. If cultures are the aidagara between Ningen and Fudo, cultural principles may come from Ningen, Fudo, or aidagara. Yet since Watsuji only acknowledged Fudo as conditions rather than determinations of values, here Fudo should not be an option. The possible options would be: (1) since Ri (principle) is included in the Rinri (ethics) of Ningen, the normativity of cultural principles comes from Ningen; (2) since gara of aidagara may mean power, it suggests that aidagara has power determining normative values; or (3) since Ningen also consists of aidagara, normative principles may come from both.

As we have seen in previous sections, the normativity of Ningen comes from the ri of Rinri, or the ‘existence of communion’ or principles of social life as Yang indicated (Yang 2012, p. 403). For instance, the principle of the relationship between rulers and ministers is loyalty. But what is the origin of such Ri? Since Watsuji rejects metaphysical entities like Heavenly command (as the Cheng Zhu school claimed), mind nature (as the Lu Wang School claimed), or God (as Christians believed), Ri can only come from aidagara, namely, interactions among self, others, individuals, society, Ningen, and Fudo. Yet aidagara as an interactive relationship seems to fail to determine normative values. For example, while ‘family love’ is a normative value in the aidagara between parents and children, it is not necessarily manifested within such an interactive relationship in the case of family tragedies. The absence of ‘proper ’normative value in interpersonal relationships suggests that the existence of aidagara does not guarantee the manifestation of normative values but is just a place where these values are manifested. In other words, (2) and (3) are false.

Hence Watsuji seems to suggest that normative principles are determined by Ningen as a human society rather than aidagara. As he claimed, ‘What they call a developed stage of the feeling of obligation is, in truth, none other than a developed stage of this socio-ethical organization. The feeling of approval or disapproval is simply an experience one has from within this organization.’ (Watsuji 1996, p. 128). Yet if normative principles are merely determined by a socio-ethical organization, Watsuji’s ethics would be inclined to collectivism, which contradicts the duality of individuality and sociality asserted by his concept of Ningen. While this paper does not aim to defend Watsuji from criticism for being a collectivist or even an authoritarian, one may suspend such criticism against Watsuji because Watsuji argued that societies arise from the interactions among individuals. If normative principles were determined by society, individual members may also be involved in the process of decision-making. Furthermore, equality is embedded in the concept of aidagara, which highlighted duality: rulers and ministers, parents and children, husband and wife, the elderly and the young, and friends are equally committed to normative values in their interpersonal relationships with the same duties. In this sense, they are equal moral agents.

Therefore, in Watsuji’s philosophy, normative principles can only come from and be determined by Ningen. Yet Watsuji did not explain how these normative principles are decided in Ningen: whether individual members have equal rights to participate in the process of decision is questionable. If Watsuji believed that only the authority (e.g., the government) is entitled to decide the normative principles for a Ningen, Watsuji may be criticised for being an authoritarian. Yet since this paper discusses the philosophy of culture rather than political philosophy, this paper will not comment on the issue of whether Watsuji is a collectivist or an authoritarian any further.

Instead, this paper is interested in the impacts of normative principles on the inclusiveness and exclusiveness of a culture: how do normative principles of a culture determine whether to accept or reject external values from another culture? To answer this question, in the following section, this paper extends Watsuji’s concept of aidagara to intercultural interactions by formulating the concept of Bungen.

4. Bungen: The Aidagara Among Cultures

Bungen, which is the short form for Bunka no aidagara 文化の間柄, is a new concept invented by this paper based on Watsuji’s philosophy. Bun refers to culture (Bunka 文化), while Gen refers to the aida 間 in aidagara 間柄. The formulation of such a concept is intended to overcome the limitation of Watsuji’s philosophy of culture. Watsuji only examined the aidagara between Ningen and Fudo, individuals and society, and the self and others, yet he never applied the concept of aidagara to investigate intercultural interactions. Nevertheless, throughout history, there are many examples of cultures being influenced by intercultural interactions. For instance, Han Buddhism was the result of interactions between East Asian and Hindu civilisations. The traditional clothing of Japan (kimono) and Korea (hanbok) was influenced by Hanfu in ancient China. Macanese cuisine was influenced by Portuguese, Chinese, African, and Indian cuisines. Yet cultures are not always inclusive of external influence; they can be exclusive on certain occasions. For example, Zia complained that the traditional Chinese culture remained exclusive to Christianity in the twentieth century (Zia 1980, p. 14). To examine the formation of exclusiveness and inclusiveness indicated above, this section introduced the concept of Bungen and argued that Bungen begins with the aidagara between languages (Gogen 語間), where two societies communicate with each other and gradually recognise their similarities and differences before selectively forming connections among values.

Similar to Ningen, Bungen is also conditioned by Fudo. For instance, if there were no encounter between an indigenous tribe in the Amazon rainforest and an Inuit community in Greenland, there would be no Bungen formed between these two communities. Conversely, owing to their close proximity, a Bungen between Korea and Japan is more likely to be formed. Nevertheless, thanks to technological advances in transportation and communication, humans have overcome the constraints of Fudo. This suggests that Fudo fails to determine the formation of Bungen.

If Ningen discovers itself when interacting with Fudo, a culture may discover itself when interacting with a cultural other. Yet these two interactions are qualitatively different: firstly, in the aidagara between Ningen and Fudo, Ningen is active while Fudo is passive because Fudo is not an acting subject communicating with Ningen, and Ningen and Fudo do not share equal status. Fudo does not use human language to communicate with Ningen; therefore, in the context of communication, Fudo is passive.6 Conversely, in Bungen, the cultural self and others are both active and passive and share equal roles. Secondly, Bungen necessarily involves dialogues among cultures. Languages are necessary for interpersonal relationships. As Martin Buber argued, humans are living in ‘the world of relation’ which consists of three spheres: ‘our life with nature’, ‘our life with men’, and ‘our life with intelligible forms’, namely, the God–man relationship (Buber 2008, p. 6). Using Watsuji’s terminology, the first sphere is the aidagara between Ningen and Fudo, the second is the aidagara between Self and others, and the third is the aidagara between God and humans.7 Bungen as intercultural interactions belong to the second sphere, which involves dialogue between self and others and therefore involves languages.

To understand how an intercultural dialogue begins, one may refer to Han Byung-Chul’s study of otherness. According to Han, dialogues begin with listening rather than speaking:

Listening is not a passive act. It is distinguished by a special activity: first I must welcome the Other, which means affirming the Other in their otherness. Then I give them an ear. Listening is a bestowal, a giving, a gift. It helps the Other to speak in the first place. It does not passively follow the speech of the Other. In a sense, listening precedes speaking; it is only listening that causes the Other to speak. I am already listening before the Other speaks, or I listen so that the Other will speak.(Han 2018, p. 70)

Han’s model of dialogue may explain Bungen: Bungen begins with a cultural self listening to a cultural other instead of the cultural other speaking to the cultural self. If the self refused to listen to the other in the beginning, the other could not manifest to the self, and Bungen would not occur. Hence Bungen begins with the openness of the cultural self to the cultural other.

Nevertheless, from the perspective of aidagara, Han’s model of ‘listen first, speak latter’ seems to assume that the self pre-exists others: the self exists first and then listens to others. Yet according to Watsuji, the occurrence of aidagara precedes the self and others whose existences depend on aidagara. However, as it is mentioned above, this paper suspends the ontological debates on whether the self pre-exists aidagara. To avoid inclining to Han’s assumption that the self and listening preexist, the dialogues in Bungen should not begin with the self’s listening but with speaking and listening to each other and being open to each other.

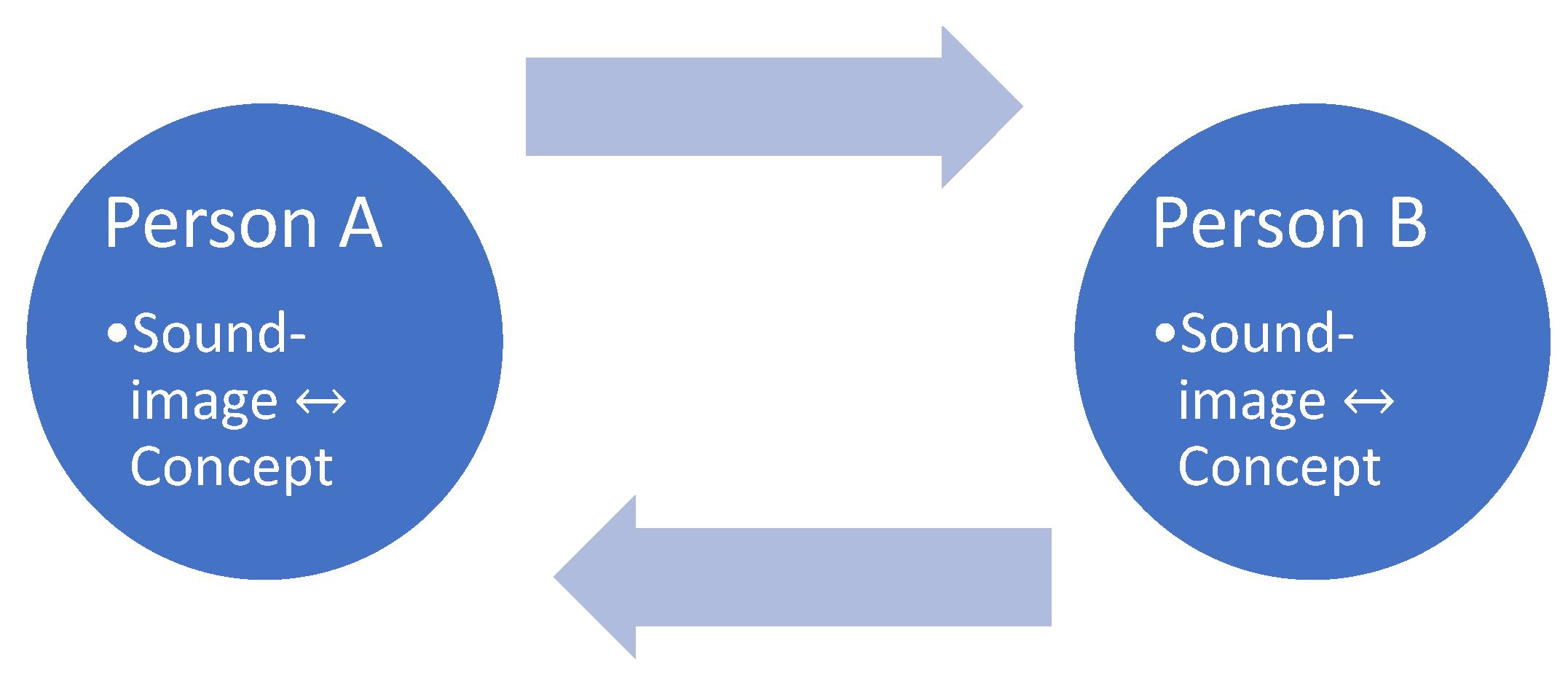

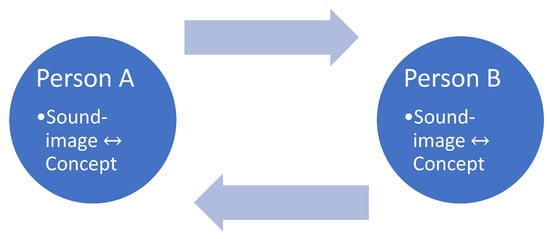

Another problem of Han’s model with ‘listen first, speak later’ is the assumption that listening and speaking can be separated. Yet the separation of listening and speaking implies the destruction of languages and understanding. Ferdinand de Saussure proposed in his Courses in General Linguistics the distinction between la Parole, which is individual and heterogeneous, and la Langue, which is a socially homogeneous system with established principles. The former ‘is an individual act. It is wilful and intellectual’, while the latter is ‘not a function of the speaker; it is a product that is passively assimilated by the individual.’ (Saussure 1983, p. 14). In Saussure’s model of the speaking circuit, where two persons A and B are speakers and listeners at the same time, they convert sound-image perceived to concepts and concepts to sound-image expressed (Saussure 1983, pp. 11–12) (see Figure 1). Here both persons A and B share the same la Langue so that they can map concepts and sound-images in a similar way and understand each other.

Figure 1.

Reconstruction of Saussure’s Speaking-Circuit.

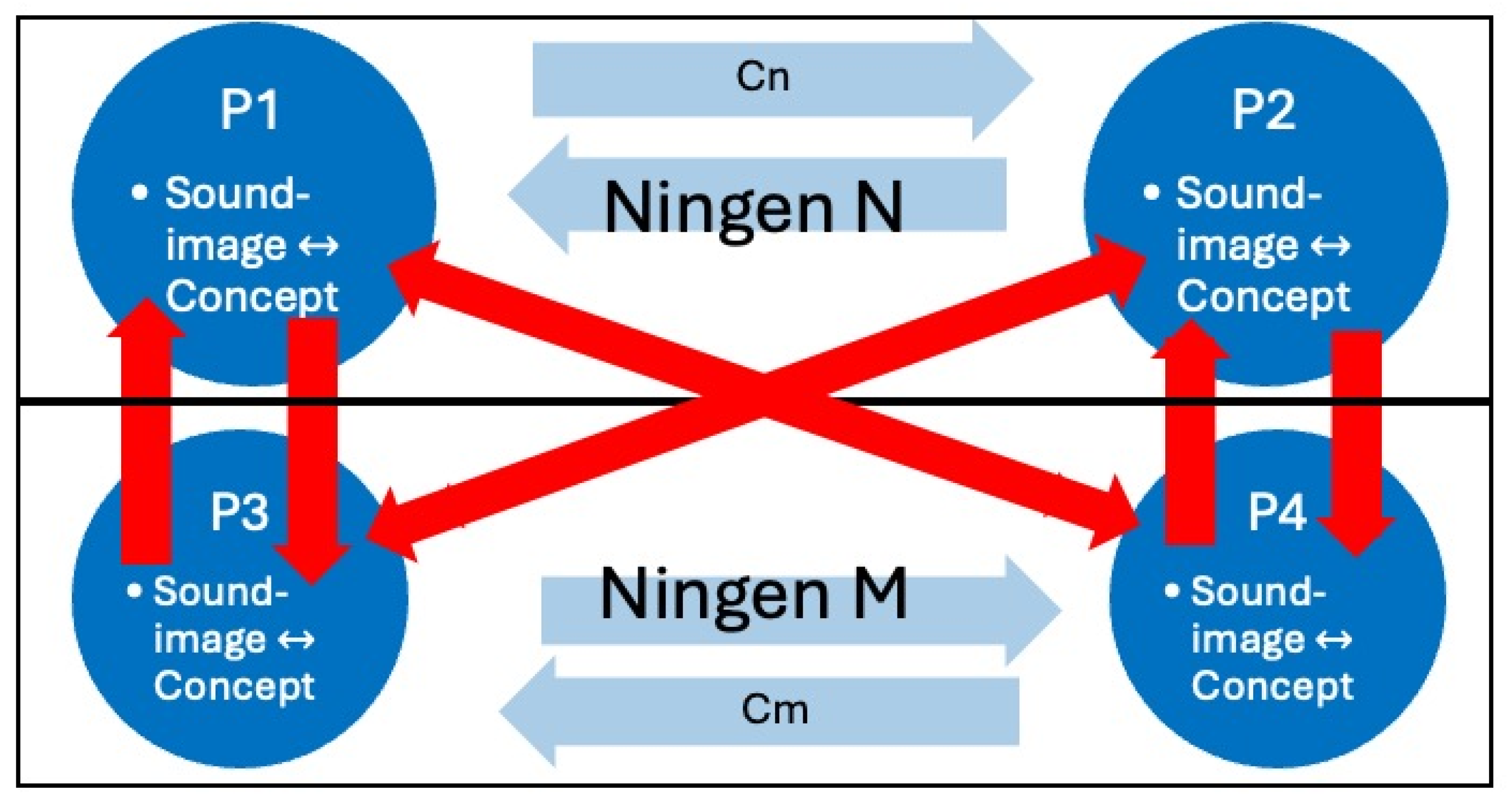

However, Saussure’s model seems to be inapplicable to intercultural interactions because the participants are not individuals but Ningen, which is the duality of individuality and sociality. There is not just one speaking circuit, but at least two speaking circuits, and the challenge would be how these circuits can interact with each other because in Saussure’s model, a speaking circuit is a closed system. An open system is needed to overcome Sassure’s limitations. Let there be two Ningen N and M, N with two members P1 and P2 formulating a circuit Cn while M with two members P3 and P4 formulating a circuit Cm, and P1, P2, P3, and P4 communicate with each other, as shown in Figure 2. The horizontal arrows (between P1 and P2 and P3 and P4) are within the same Ningen, while the vertical (between P1 and P3 and P2 and P4) and diagonal arrows (between P1 and P4 and P2 and P3) are inter-Ningen (and therefore intercultural). Here Cn and Cm are open to each other because individuals of both M and N participate in intercultural communication.

Figure 2.

Inter-Ningen or intercultural communication.

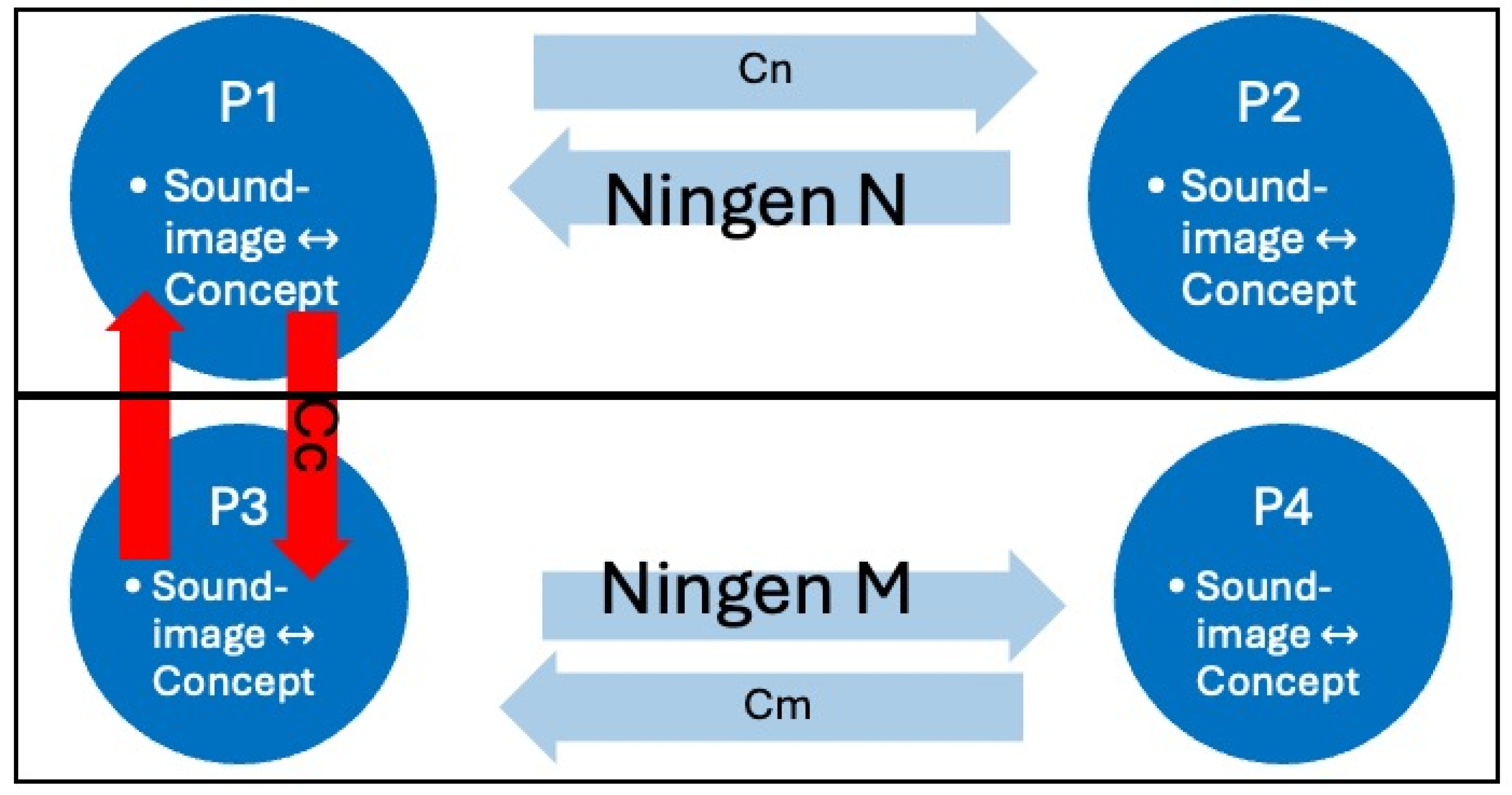

But here is another question: how could individuals communicate with other individuals from other Ningen? In-Ningen communication seems possible if M and N share the same common language like Latin or Kanji, although M and N have their own languages. For example, although Arai Hakuseki 新井白石 (1657–1725) spoke Japanese and the Korean diplomat Jo Tae-eok趙泰億 (1675–1728) spoke Korean, because they shared Classical Chinese as a common language, they engaged in an inter-Ningen communication recorded in Kōkan hitsudan 江関筆談. Although in Arai’s time, only very few Japanese and Koreans could communicate with each other, Arai’s and Jo’s identities as diplomats and scholars mean that their intercultural communications were not merely personal but also social-political, shaping the intercultural understanding between Japan and Korea. The case of Kōkan hitsudan suggests that key persons with particular social status have a leading role in intercultural communication. In Figure 3, even though P1 and P3 are the only individuals from M and N, respectively, who participated in intercultural communication (through the circuit Cc), if P1 and P3 have certain social statuses to extend the influence of their communications to their Ningen, Cn and Cm remain open to each other.

Figure 3.

Case when only P1 and P3 are involved in intercultural communication.

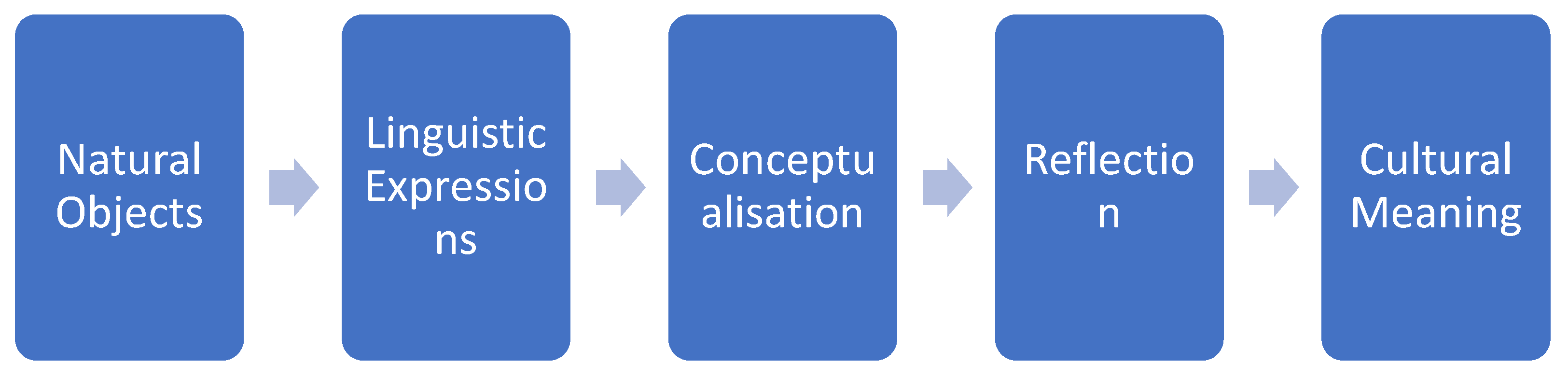

Yet one may wonder how Cc could be established when there is no common transcultural language shared between N and M. In this case, intercultural communication could only be achieved by interpretations and translations to overcome the exclusiveness of languages in order to form Bungen. Yet all translations and interpretations have an assumption: that meanings and utterances expressed in another’s language can also be expressed by the self’s language. For example, Huajiyiuyu 華夷譯語 (1382), a dictionary of interpretations used by the Ming Dynasty, used Kanji to denote pronunciations of foreign languages and assumed that these pronunciations convey meanings.8 Yet one would not assume that a crow’s chirps or the traces of an ant’s footsteps convey linguistic meanings to be interpreted because these utterances are not expressed by human beings. As Tam argued, in the human world, humans assume each other’s sounds and signs follow the same linguistic-cultural formula for designations of meanings (Tam 2020a, p. 21); while this formula is not a language, it is a common structure shared by all languages. Since such a formula allows languages to interact with each other and achieve mutual understanding, such a formula may also be regarded as an aidagara among languages, or Gogen 語間: because all Ningen sonzai share this common linguistic-cultural formula, one assumes that the sound-image or word-image expressed by a member of another culture is meaningful (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The process of designating meanings to objects.

Through listening and speaking to each other, a culture discovers itself in Bungen; a culture discovers that the self and others are both similar and different. Just as listening and speaking are simultaneous, the manifestations of similarities and differences in Bungen are also simultaneous. When the self encounters another in Bungen, on the one hand, the self becomes aware of the shared Gogen that is used; on the other hand, it is found that different values are expressed in different languages. In Saussure’s terms, in Gogen, a foreign language presents itself not as la parole but as la langue, constituting a circuit that leads to the formation of Bungen. Nevertheless, a circuit is a closed recycling system; thus, when the self is open to the other A based on a shared Gogen, this simultaneously excludes other others B, C, or D, etc. Hence, openness and exclusiveness are both found in Bungen.

When Bungen occurs, there are three possible choices for the self and others:

- Completely accept the other’s different values.

- Partially accept the other’s different values/partially reject the other’s different values.

- Completely reject the other’s different values.

When one culture accepts the values of another culture, it is conditioned by Bungen. If Confucianism had not been introduced from China to Japan, the Confucian values of humaneness, rightness, propriety, and wisdom, which were regarded as essential values of Bushido by Nitobe Inazo (Nitobe 1969, p. 58), would not have been adopted by Japanese culture. Since Nitobe regarded Bushido as a product of the integration of Shinto, Confucianism, and Buddhism, he claimed that in the future Bushido may even include the Christian value of universal love (Nitobe 1969, p. 127).

Additionally, even when one culture rejects the values of another culture, it is also conditioned by Bungen, because the denial of foreign values re-asserts or even reinterprets essential values prioritised by the culture. In the eighteenth century, when the Japanese scholars of Kokugaku tried to resist Chinese cultural influences, criticise Confucianism and Buddhism, and ‘restore’ the ‘authentic’ Shinto, they reconstructed new concepts that represent the so-called Japanese values. Motoori Norinaga, a remarkable scholar of Kokugaku, argued that the Japanese must reject the Chinese heart (Kan kokoro 漢心) and restore the Japanese heart (Yamato kokoro 大和心) by re-interpretation the ‘national’ writings. In Motoori’s reinterpretation of The Tale of Genji, he argued that 物の哀れ Mono no aware, which is an immediate emotional response to external affairs, is an essential value of Japanese culture. He further argued that Confucian and Buddhist teachings on the suppression of emotions were against the value of Mono no aware and therefore should be rejected (Motoori 2011, p. 1176). Yet Mono no aware was not regarded as an essential value for Japanese culture until Motoori. In other words, by rejecting Chinese values, the scholars of Kokugaku re-emphasise or even reinterpret the disregarded values of Japanese culture as something essential. In this sense, their conservatism also arises from the Bungen between Chinese and Japanese cultures.

If the self and others completely accept each other’s values, both cultures are integrated into a new culture. Conversely, if either the self or others completely reject the other’s values, both cultures are separated. If only one party completely accepts the other’s values, there is assimilation. On the one hand, since both integration and assimilation imply the disappearance of the distinction between the self and others, Bungen is also eliminated. On the other hand, when there is a separation, Bungen also ceases to exist. Therefore, only when the self and others maintain being similar yet distinct, accepting some values from each other while rejecting others, can Bungen be maintained.

In short, the formation of Bungen may be summarised as below:

- Gogen: the cultural self and others listen and speak to each other.

- The cultural self and others present their value judgements to each other.

- If both maintain being similar yet distinct, Bungen continues to exist. If there is separation, integration, or assimilation, Bungen ceases to exist.

One may wonder how the cultural self and others decide whether to maintain Bungen. It seems that it is not merely determined by clashes of value. For instance, when two people go out for dinner together, one would like to go to a sushi restaurant while the other does not want to eat sushi at all. Here is a conflict of choices between two persons, yet it does not necessarily lead to separation because they may compromise and make mutual concessions, e.g., go to a restaurant that serves both sushi and bento. A separation only results from the situation when both sides refuse to make any concessions and regard their choices as essentially important.

What determines the existence of Bungen is passions or interests for values instead of the values themselves; namely, when a culture is particularly interested in certain values, these values are prioritised, and any foreign value contradicting the prioritised values would be rejected. As Tam said, ‘Passions orient the cultural development by prioritising certain values (aesthetic, epistemic, ethical, and passion) in particular ways.’ (Tam 2020a, pp. 248–49). Tam continued:

It is not one particular value or one spirit that determines cultural development; instead, it is the passion for certain values that drives cultural development. Every individual is capable of manifesting aesthetic, epistemic, ethical, and religious passions, and all cultural groups are a community consisting of individuals; therefore, a culture can manifest and prioritise any passion; there is no fixed ‘spirit’ or value system to determine its development.(Tam 2020a, p. 248)

Hence, the formation of Bungen should be revised as below:

- Gogen: the cultural self and others listen and speak to each other.

- Orientation: cultural self and others present their value selections according to their own passions to each other.

- If both maintain being similar yet distinct, Bungen continues to exist. If there is separation, integration, or assimilation, Bungen ceases to exist.

Therefore, in Bungen, when the self prioritises certain values, these values become essential normative principles deciding which values should be accepted or rejected and preserved or destroyed. Yanagita used the legend of wolfs as an example: ‘Some people are concerned (心持 kokoromo) that without vigorous dissemination by specific groups, ancient legends will lose their value in terms of being heard and remembered and will eventually die out on their own.’ (Yanagita 1939, p. 101). Being subjectively acknowledged the importance of the preservation of ancient legends, writers rewrote and circulated them. Similar examples are also found in Confucianism. Confucius said: ‘That I fail to cultivate Virtue, that I fail to inquire more deeply into that which I have learned, that upon hearing what is right I remain unable to move myself to do it, and that I prove unable to reform when I have done something wrong—such potential failings are a source of constant worry to me.’ (Analects 7.3) (Slingerland 2003, p. 64). All these examples suggest that subjective commitment to certain values determines value preservation.

In addition, changes in relationships between the self and others may lead to changes in value judgement. For example, Yanagita realised that the ancient legend of the ‘good wolf’ was replaced by the early modern legend of the ‘evil wolf’ when Japanese farmers expanded their farmlands to forests (Yanagita 1939, pp. 209–10). Japanese’ value judgement on wolves varied with their relationships with wolves.

Similarly, in Bungen, changes in intercultural relationships may lead to changes in value judgement. Remarkably, the case of the Chinese rites controversy shows that the clash of values does not necessarily disrupt the Bungen between two cultures; it disrupted Bungen only when there is a clash of prioritised values and both parties refuse to make a concession.

The Chinese rites controversy was a dispute among Catholic missionaries on whether Confucian rituals of sacrifices to ancestors should be allowed. Gradually, such controversy led to the ban of Catholicism by the Qing dynasty in the eighteenth century, when the pope officially disallowed all East Asian Catholics to sacrifice to ancestors. In the light of the concept of Bungen, the case of the Chinese rites controversy may be analysed as follows:

Firstly, Gogen. Catholic missionaries translated Four Books and Five Classics to Latin and catechisms to Classical Chinese so that a dialogue between Confucians and Christians was constructed.

Secondly, orientation. Christians prioritised the belief in God the Trinity and salvation through Christ’s resurrection, while Confucians prioritised the virtues of humaneness. According to Confucius, filial piety is the root of humaneness (Analects 1.2), and filial piety is expressed by the sacrifices to ancestors. Hence sacrifices to ancestors were emphasised by Confucians. Here is a value difference between Christianity and Confucianism: while the former highlighted belief in God, the latter highlighted manifesting filial piety.

Early in the seventeenth century, the value difference indicated above had developed into a clash of prioritised values between Christianity and Confucianism, since Franciscan and Dominican missionaries forbade Chinese Catholics to sacrifice to ancestors because they regarded such a ritual as a rite of idol worship. Their teaching provoked Confucian officers like Chen Yidian, who argued that

[Catholics] instigate the people below and said: ‘Ancestors do not require any sacrifice; one should only worship God so that one can enter Heaven and avoid Hell.’ While teachings on Heaven and Hell are also found in Buddhism and Daoism, these teachings are used to encourage filial piety but discourage unfilial piety, disrespect, and evil karma. So they are conducive to Confucian teaching. Since the Catholic church asked people not to sacrifice to ancestors, Catholicism is a religion with no filial piety.(Chen 2022)

Yet the clash of values was overcome when Matteo Ricci (1552–1610) and other Jesuit missionaries allowed Chinese Catholics to sacrifice to Heaven, ancestors, and Confucius as long as these Confucian rituals did not involve supervision (Franzen 1988, p. 324). Since Jesuits made a concession by providing an alternative interpretation of sacrifices to ancestors, a clash of values was avoided: Catholics did not regard the sacrifices to ancestors, which were prioritised as essential rituals by Confucians, as something against their prioritised religious values.

However, the Qing court changed its attitudes toward Catholicism when Pope Clement XI enacted bans on sacrifices to Heaven, ancestors, and Confucius in 1704 and 1715. The Kangxi emperor, who regarded Confucianism as the official philosophy of the empire, was provoked by the Pope’s edicts and banned Catholicism in 1721 in response. Bungen was suspended as a result. Since both parties refused to make any concession, a clash of prioritised values is inevitable.

Yet Bungen may be restored when intercultural relationships and interpretations of values change. Having been defeated by the British Empire in the Opium War in 1842, the Qing dynasty was forced to open to missionary trade. In 1939, having consulted bishops in China, in Plane compertum est, Pope Pius X officially allowed Catholics to participate in ancestor venerations. In 1974, the Bishops in Taipei ‘approved the “Proposed Catholic Ancestor Memorial Liturgy” in which ancestor veneration became an integral part of Chinese Catholic life.’ (Butcher 1994, p. i).

The case study of the Chinese rites controversy illustrates a feature of the exclusiveness of Bungen: a clash of values may not lead to the suspension of Bungen if it does not involve prioritised values. As mentioned above, Chen condemned Catholicism not because Confucianism does not share the Christian teaching of Heaven and Hell but because the Catholic ban on ancestor veneration was against the Confucian essential teaching on filial piety.

The case study of the Chinese rites controversy also highlighted the impact of the openness to interpretations on the clash of prioritised values: the higher the openness is, the higher inclusiveness of culture is. There is an openness to interpretations of ancestral veneration. While Franciscan and Dominican missionaries regarded ancestor veneration as an act of idol worship, Chan Man Ning investigated 28 articles written by Chinese Catholic literati in the seventeenth century, arguing that ancestor veneration is not an act of idol worship but a secular ritual expressing filial piety (Chan 2017, pp. 52–62). Since there is an openness to the interpretation of ancestor veneration, here the inclusiveness of Confucianism to Christianity is maintained.

In short, the inclusiveness and exclusiveness of Bungen are revealed in the orientation of the two cultures when they prioritise different values. The prioritised values formulate the normative principles determining which foreign values are to be accepted and rejected. Yet the openness to interpretations of value also influences the inclusiveness and exclusiveness of Bungen: the higher the openness is, the more inclusive the culture is; the lower the openness is, the more exclusive the culture is.

5. Conclusions

By proposing the concept of Bungen, this paper provides a new perspective on intercultural interactions and overcomes the problem of essentialism and transculutralism. On the one hand, unlike essentialism, Bungen suspends the assumption of the pre-existence of a ‘cultural spirit’ or a set of essential values. On the other hand, unlike transculturalism, Bungen maintains the exclusiveness and normativity of cultures by investigating the orientations of cultures.

Different from Watsuji, who only investigated the aidagara between Ningen and Fudo, this paper extends the concept of aidagara to investigate how cultures are conditioned by intercultural interactions. Yet since this paper suspended Watsuji’s Buddhist ontological assumption of no-self and emptiness, this paper does not claim whether the existence of cultures precedes intercultural interactions. Instead, this paper only demonstrates how cultures are conditioned by Bungen and manifest their normative values by accepting and rejecting foreign values. Bungen begins with Gogen, when a dialogue between two cultures is formed. Then two cultures present their own essential values. In the case of Kokugaku, the cultural self discovers its essential values by disagreeing and rejecting the other’s values. When there is a clash of prioritised values and both sides refuse to make any concession by interpreting values in alternative ways or revising their own normative principles (by prioritising other values instead, for example), there is a separation and Bungen ceases to exist. However, if a culture completely accepts all values of another culture, or two cultures fully accept each other’s values, since cultural differences cease to exist, Bungen is also eliminated. Bungen remains existing only when both cultures maintain their values, similarities, and differences. Future research may further examine how the theory of Bungen explains the formulation of certain ‘integrated’ cultures, e.g., how Hong Kong culture arises from the interaction between the Chinese and Western cultures, and help to solve the clashes of values by reinterpreting cultural values.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

This paper was based on two oral presentations: one at Space Between/Aidagara: Landscape, Mindscape, Architecture from 6 to 8 March 2023 at the University of Glasgow, and another at the Annual Conference of Chinese Philosophy Association on 18 December 2022 at the Fujen University. The author would express gratitude to Ramona Fotiade and Cheung Ching-yuen for their constructive comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Since this paper focuses on how resources from Watsuji’s philosophy may help overcome the limitations of both essentialism and non-essentialism, criticism of the Hegelian model is not the focus of this paper. For the criticism of the Hegelian model, please refer to (Tam 2020a). |

| 2 | While a reviewer suggests translating Bungen to “interculturality”, interculturality is not preferred here, because “inter-” in English usually assumes that the existences of A and B precede that of the relationship between A and B. Yet, Bungen, as a kind of aidagara, assumes the reverse: the existence of the relationship between A and B precedes those of A and B. For this reason, this paper preserves the term Bungen. |

| 3 | Cheung argued that there are different interpretations of the concepts of self and others in Nishida’s philosophy, including basho, personality and empathy. Yet Cheung did not discuss which interpretation he preferred. (Cheung 2017, p. 110). |

| 4 | Because one reviewer argues that aidagara with nature and cultures should not be separated as different aidagara, here I explain the necessity to distinguish both. |

| 5 | Yet one should not misunderstand that Watsuji is ‘interpreting Confucianism in terms of Buddhism’. Although Watsuji adopted the Buddhist ontology of emptiness or nothingness, as Tam argued, Watsuji’s concept of Ningen is not completely Buddhist because he only picked up Ningen from the Buddhist notions of Six Paths but rejected all other concepts of ‘paths’ or worlds. In this sense, Watsuji is neither Confucian nor Buddhist. See (Tam 2020b, p. 174). |

| 6 | However, in other contexts, Fudo actively interacts with Ningen. For example, Fudo actively brings natural disasters to Ningen who could only passively react. Fudo also actively assert geographical limitations on agriculture and transportation. |

| 7 | For the concept of aidagara between God and humans, please refer to (Tam 2022). Buber’s trichotomy of relationships is very similar to the dialectics of community proposed by Kierkegaard; for relevant discussions, please refer to (Tam 2020a). |

| 8 | Translation also involves transcultural understanding, so Bungen and translation are mutually influenced. For example, when Protestant translated the Scripture into Chinese, they were manifesting Christianity by means of not only Chinese languages but also Chinese culture. |

References

- Buber, Martin. 2008. I and Thou. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, Beverly Joan. 1994. Remembrance, Emulation, Imagination: The Chinese and Chinese American Catholic Ancestor Memorial Service. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Byram, Michael, Martyn Barrett, Ildikó Lázár, Pascale Mompoint-Gaillard, and Stavroula Philippou. 2013. Developing Intercultural Competence Through Educatio. Strasbourg: Council of Europe. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Man Ning (陳文寧). 2017. An Analysis of Ming and Qing Dynasties Chinese Scholar-Believers’ Studies on Ancestral Offering Ritual 論明清中國士人信徒對祭祖禮的探討. Hong Kong: Red Publish. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yi-dian (陳懿典). 2022. Sheng Chao Po Xie Ji Juan Yi Nan Gong Shu Du 聖朝破邪集卷一.南宮署牘. 6.10. Available online: https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&chapter=866735 (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Cheung, Ching-yuen (張政遠). 2017. Nishida Kitaro: Japanese Philosophy in Transcultural Perspective 西田幾多郎: 跨文化視野下的日本哲學. Taipei: National Taiwan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, Junmai (張君勵). 1962. The Development of Neo-Confucian Thought. India: Bookman Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Franzen, August. 1988. Kleine Kirchengeschichte. Freiburg: Herder. [Google Scholar]

- Furuya, Yasuo (古屋安雄), Akio Doi (土肥昭夫), Toshio Sato (佐藤敏夫), Seiichi Yagi (八木誠一), and Masaya Odagaki (小田垣雅也). 2002. A History of Japanese Theology 日本神學史. Translated by Ruo-shui Lu (陸若水), and Guo-peng Liu (劉國鵬). Shanghai: Joint Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffour, Mohamed Toufik. 2022. Anti-Essentialist Culture Conception for Better Intercultural Language Teaching in EFL Contexts. Arab World English Journal 13: 273–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Byung-Chul. 2018. The Expulsion of the Other: Society, Perception and Communication Today. Translated by Wieland Hoban. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. 1995. Lectures on the Philosophy of the World History. Edited by Robert F. Brown and Peter C. Hodgson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Heubal, Fabian. 2009. Transcultural Critique and Philosophical Reflections on Chinese Modernity 跨文化批判與中國現代性之哲學反思. Router: A Journal of Cultural Studies 8: 125–47. [Google Scholar]

- Heubel, Fabian. 2008. Contemporary Sinophone Philosophy in the Midst of Transcultural Dynamics 跨文化動態中的當代漢語哲學. Si Xiang 8: 175–87. [Google Scholar]

- Motoori, Norinaga. 2011. Mono no aware. In Japanese Philosophy: A Sourcebook. Edited by James W. Heisig, Thomas P. Kasulis and John C. Maraldo. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 1176–77. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, Dorottya. 2010. Where is China in World Christianity? Diversities 12: 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida, Kitaro (西田幾多郎). 1998. The Forms of Culture of the Classical Periods of East and West Seen from a Metaphysical Perspective. In Sourcebook for Modern Japanese Philosophy: Selected Documents. Edited by David A. Dilworth, Valdo H. Viglielmo and Augstin Jacinto Zavala. London: Greenwood Press, pp. 21–36. [Google Scholar]

- Nitobe, Inazo. 1969. Bushido: The Soul of Japan. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Saussure, Ferdinand de. 1983. Course in General Linguistics. Edited by Perry Meisel and Haun Saussy. Translated by Wade Baskin. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Slingerland, Edward. 2003. Confucius Analects. Indianapolis and Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Suganono, Mizuchi (菅野真道), No Tugutada Fujiwara (藤原継縄), and No Yasuhito Akishino (秋篠安人). 1883. Shokunihonki 続日本紀. 40 vols. Tokyo: Kishida Ginkou, vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, Andrew Ka Pok (譚家博). 2020a. On the Kierkegaardian Philosophy of Culture and Its Implications in the Chinese and Japanese Context (Post-1842). Ph.D. thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, Andrew Ka Pok. 2020b. On the Relation between Watsuji Tetsurō’s Ningen Rinrigaku and Mencius’ Five Relationships. Taiwan Journal of East Asian Studies 17: 135–82. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, Andrew Ka Pok (譚家博). 2022. God-Man Relation as the Aidagara of the Pain of God—A Response to KITAMORI Kazoh’s Theology of the Pain of God 神人關係作為「上帝之痛」的間柄—對北森嘉藏《上帝之痛的神學》的回應. Logos and Pneuma-Chinese Journal of Theology 57: 337–64. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Jungyi (唐君毅). 2015. Shuo Zhong Hua Min Zu Zhi Hua Guo Piao Ling 說中華民族之花果飄零. Taipei: Sanmin Book Co. Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Tillich, Paul. 1964. Theology of Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watsuji, Tetsuro (和辻哲郎). 1961a. A Climate: A Philosophical Study. Translated by Geoffrey Bownas. Tokyo: Ministry of Education Japan. [Google Scholar]

- Watsuji, Tetsuro. 1961b. The Complete Collection of Watsuji Tetsuro 和辻哲郎全集. Tokyo: Iwanami, vol. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Watsuji, Tetsuro. 1996. Watsuji Tetsurō’s Rinrigaku. Translated by Yamamoto Seisaku, and Robert E. Carter. Albany: State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagita, Kunio. 1939. 孤猿随筆 Koen Zuihitsu. Tokyo: Sogensha. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Ru-bin (楊儒賓). 2012. The Meaning of Oppositions: A Reflections on the Anti-Neoconfucianism in Modern East Asia 異議的意義:近世東亞的反理學思潮. Taipei: National Taiwan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zia, Nai Zin (謝扶雅). 1980. Christianity and Chinese Thoughts 基督教與中國思想. Hong Kong: Chinese Christian Literature Council. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).