Abstract

The Danish artist Peter Brandes (1944–2025) visited the poet’s town of Tübingen (Germany) in 2007 and was inspired by the four portraits of Hölderlin (1770–1843) that were created during his time in the so-called tower. Hölderlin spent half of his life there. Admitted to the University Clinic in Tübingen, diagnosed as incurable after six and a half months, he was released into the care of the carpenter Ernst Zimmer and his family in the house by the Neckar River, where he remained until his death. Based on these portraits, Brandes created over 100 works, seeking dialogue with Hölderlin. Following a brief overview of the artist Peter Brandes, we discuss the background of the four portraits that inspired his Bildgespräche: Hölderlin’s illness, his condition during his stay in the tower, and briefly, the poems he wrote during this period. A detailed discussion of the four portraits is followed by a presentation of Brandes’ “Annäherungen” (approaches) to these images in the form of his Bildgespräche.

1. The Artist Peter Brandes: A “Kulturwanderer”

Peter Brandes (* March 5 1944, Assens/Denmark, † January 4 2025) was a master at home in various genres: painting, drawing, graphics, woodcutting, sculpting, ceramics, stained glass and photography. He studied at Odense Cathedral High School in Denmark, graduating in 1964; studies in philosophy and French followed at the University of Copenhagen and the University of Aix-en-Provence in southern France. In 1966 he had his first solo exhibition at the Art Gallery Filosofgangen in Odense. In the following years, his travels took him to Turkey, Greece, North Africa, Spain and France. From 1976 onwards, he organized an exhibition in the aforementioned disciplines almost every year. Commissioned work took him to Sweden, Norway, Israel, Italy, France, Germany and the USA. He presented a remarkable body of work: about 50 exhibitions and 130 books and catalogues.1

A citizen of the world who spoke several languages fluently, a master of the art of living, a storyteller who carried the history of a century within him without despairing, generous and possessing an unfailing sense of humor, he was well aware of the difficult history of our century, which never let go of him, and he consciously confronted it in his work. Whoever engages with Brandes:

[…] und seine Werke betrachtet, der erfährt augenblicklich, dass das scheinbare Antike in die Gegenwart reicht, sich erneuert hat in Gestalt und zeitlosen Formen der ungelösten alten menschlichen Konflikte, sich wiederholt in betörenden wie auch grausamsten, nicht abgeschlossenen Erzählungen.(Baltzer 2008, p. 8)

[…] and views his works, immediately realizes that what appears to belong to antiquity extends into the present; it has renewed itself in the shapes and timeless forms of unresolved, ancient human conflicts, repeating itself in beguiling, and in most cruel, unfinished stories.

But all his countless trips and stays in other countries alone do not make him a “cultural wanderer.” It is the concept of “translatio studii”, or “cultural migration”, that Ettore Rocca sees in Brandes’ complete work.2

In contemporary art, there are scarcely any other artists for whom a new interpretation of classical Kulturwanderung [cultural migration] is as central as it is for Peter Brandes. There is only one other example of a similar cultural migration, and that is found in the work of Anselm Kiefer.

The concept of Kulturwanderung goes back far in Western culture. It designates the way in which art forms, sciences, and ideas migrate from people to people, from culture to culture.(Rocca 2019, p. 10)

For Peter Brandes, cultural migration is first and foremost a fact inscribed in his family history. But his family history is only an occasion for the migration among cultures that he undertakes with his art. Brandes understands his artistic activity as cultural migration. He is in uninterrupted conversation with his history, and as a result is in continuous dialogue with the most varied array of cultures.(Rocca 2019, p. 11)

Brandes himself expresses it this way:

But it is Mediterranean culture, the interaction between Judaism, Christianity, and Hellenism, and the products of culture in that region, that have been the greatest driving force in my art.(Brandes quoted in Rocca 2019, p. 11 and note 7)

Brandes’ work is characterized by his preoccupation with the oldest excavations of cultural history, Greek mythology, history and literature (Homer’s Odyssey and Iliad, Kierkegaard, Paul Celan, Franz Kafka, James Joyce, Friedrich Hölderlin), the Bible—for the Roskilde Cathedral he designed the large, regal entrance gate and a chapel, and recently he completed several works with a variety of materials for the Aarhus Cathedral. The monumental foot he created (1994; H. 550 × W. 600 cm) is impressive; it hovers over the water in the harbor of Tuborg (Denmark) as a symbol of transition—the word for foot and flight are identical in an Aramaic dialect. As an admonitory reminder of the book burnings planned by the National Socialists in 1933, Brandes created 30 burning heads carved and printed as woodcuts.3

The starting point for all of his work is culture, i.e., the totality of the intellectual, artistic and creative achievements of a human community (as opposed to the natural world). He is occasionally criticized for his literary and philosophical interests. To this he replied: “Ist es verboten, beim Malen Gedanken zu haben und wissend zu sein? Cézanne sagte, er habe nur das Licht gemalt. Vielleicht ist das so am besten” (Baltzer 2008, p. 8; Is it forbidden to have thoughts and to be knowledgeable while painting? Cézanne said he only painted the light. Perhaps it is best that way), he added with a smile.)

Brandes selected his materials with great knowledge and care4: the type of wood, its qualities, its origin, and finally the grain of the wood used for the wooden blocks, of such importance for all woodcutters, as we also know from the works of Edvard Munch (1863–1944). With the same care, Brandes chose his paper, including old paper, about whose production he was well-informed, and which he often found in Italy. About any of the materials he worked with—wood, paper, ceramic, glass—he was able to give a scholarly lecture off the cuff.

In 2013, Brandes was the first visual artist to receive the Friedrich Hölderlin Prize, donated by the University and City of Tübingen (awarded every two years from 1989 to 2015). As a thank you for the prize, Peter Brandes created the bronze sculpture Hölderlin—Heidegger—Celan for Tübingen. He was well aware of the controversial figure he evoked with Heidegger—especially after the discovery of the long-lost Black Notebooks of 1945/46. Yet Heidegger was “ein großer Bewunderer und Interpret von Hölderlin und Paul Celan. Er hat nie sein großes Engagement für diese beiden Dichter verborgen”5 (a great admirer and interpreter of Hölderlin and Paul Celan. He never made a secret of his profound engagement on behalf these two poets). Heidegger influenced a century of Hölderlin reception and, especially in France, significantly shaped it. In Brandes’ sculpture, Heidegger is not figuratively represented—unlike the two poets—but is understood symbolically as a phenomenon possessing two attributes: a wooden stump with an axe hewn into it.6

The reference points connecting the three figures are manifold. As Brandes explained:

Die Konstellation zwischen den drei Persönlichkeiten, ihre Gedanken und ihr Ausdruck ist mein Versuch, einen Aktualisierungsprozess anzustoßen—im Umkreis eines der wichtigsten Dichter Deutschlands, Friedrich Hölderlin.7

The constellation between the three personalities, their thoughts and their words, is my attempt to initiate a process of updating—within the circle of one of Germany’s most important poets, Friedrich Hölderlin.

The Jewish Brandes family8 originally came from Czernowitz (Chernivtsi). With its eventful history, Chernivtsi belonged to the Principality of Moldau (1359–1774) for 400 years, until the city and the entire Bukovina fell to the Habsburg Monarchy, which integrated both into the Austrian Kingdom of Galicia. In 1849, the Duchy of Bukovina became its own crown land, with Chernivtsi as its capital. In this city, which today lies in south-western Ukraine, Joseph Isak Brandes was born on November 14, 1877.9 “As a young man, he refused military service, and was made stateless as a result.” (Rocca 2019, p. 16) He emigrated to Leipzig where he married Anna Czapek. They moved to Bern, Switzerland, where their son Isidor Thomas Johannes, Peter Brandes’ father, was born in 1905; as the son of a stateless father, he, too, had no citizenship. Later the family moved to Zürich and stayed there until 1920.10 They then moved to Leipzig, where Isidor founded the first radio station—a new medium—and began “die bis heute bestimmenden Live-Musik-Übertragungen, damals als Brandes-Konzerte unter Kopfhörern ein Begriff”11 (the live music broadcasts still prevalent today, known at the time as “Brandes concerts” with headphones). “After the first ant-semitic laws and boycotts of Jewish-owned businesses were introduced” (Rocca 2019, p. 14), Isidor fled in March 1934 to Paris.

Peter Brandes’ etchings Brandes Tonhalle Leipzig 1933 (2018) recall his father walking with “his radio on his shoulders like a knapsack.” (Rocca 2019, p. 14)12

Thanks to a Jewish–Danish organization Isidor was able to go to Denmark in June 1935 where he spent six months as a cultural student in Voldbro, near Assens. There he met his future wife Gerda Petersen, the daughter of a farmer. They became engaged in 1935. Thanks to a petition of his future father-in-law to the Minister of Justice he “was not expelled from the country.” (Rocca 2019, p. 18) He converted to Christianity and was baptized on November 28 1936. (Rocca 2019, p. 30, note 53) The risk of being stateless remained, although Isidor married in 1937. “Even marriage to a Dane, however, did not offer security for a stateless person in Denmark. Politically, such marriages were suspected of being pro forma unions.” (Rocca 2019, p. 20) He was able to stay, but without a work permit. He secretly gave language lessons, was denounced, and arrested. Once again, his father-in-law wrote to Copenhagen, and Isidor had to report to the Ministry of Justice. The condition for remaining was to pass a language test.13

Als Isidor Brandes vor dem Rektoratsbüro wartete, hörte er, wie drinnen aus dem Faust deklamiert wurde. […], klopfte und übernahm die Rolle des Mephisto, bis die Tür aufgerissen wurde und ein verwunderter Rektor und sein Gast herausstürzten: Poul Reumert[h], einer der bedeutendsten und in Europa bekannten Schauspieler Dänemarks.14

As Isidor Brandes waited outside the rector’s office, he heard recitations from Faust coming from inside. [...], he knocked and took on the role of Mephisto until the door flew open and a surprised rector and his guest rushed out: Poul Reumert[h], one of Denmark’s most important and well-known actors in Europe.

The language test was no longer relevant; Isidor’s teaching position was secure.

The rescue of about 7500 Danish Jews by King Christian X’s resistance is a chapter in history all of its own. Isidor managed to escape imminent deportation in October 1943 and reached Sweden in a fishing boat. While in exile in Sweden in 1944, he learned through his wife’s Gerda Petersen coded message, sent under an alias and not deciphered by the security guards, about the birth of his son Peter. It was not until 1950 that he and his two children, Peter and his two years older sister Kirsten Anna, obtained Danish citizenship.

While Isidor fled to Paris, his parents with their two other children Bertha, born in 1909, and Eleonore, born in 1918, stayed in Leipzig. In 1938 they emigrated to Paris. In 1943, 1569 Jews were arrested there, among them Joseph Isak Brandes. On February 17 he was transferred to the camp of Drancy, about 15 km northeast of Paris. From there, over 60,000 Jews were transported to extermination camps, mainly to Auschwitz–Birkenau. “On March 4, together with 1002 other Jews, he was deported from Drancy in convoy 50.” (Rocca 2019, p. 21) Destination: Cholm, in eastern Poland to the extermination camp Sobibór close to Cholm, where he was murdered.15

His grandson would later erect a monument to him.

Peter Brandes created enormously tall vases; firing them required appropriate ovens and gas:

Ich habe immer an meinen Großvater denken müssen. Also machte ich die Vase für Yad Vashem [1995]. Die Vase als symbolisches Vorratsgefäß für Öl und Wein, als Urne für Gebeine und Asche und als Symbol für das Spirituelle, den Geist und den Glauben, denn auch Texte, die man im Toten Meer fand, wurden in solchen Gefäßen aufbewahrt. Sie sind mit ihren fünf Metern Höhe monströs, diese Vasen. Monströs wie die Tötungen. Ich kann das nicht begreifen, aber so habe ich meinem Großvater Isaak Brandes ein bisschen Ruhe bereitet.16

I always had to think of my grandfather. So I made the vase for Yad Vashem [1995]. The vase as a symbolic storage vessel for oil and wine, as an urn for bones and ashes and as a symbol of the spiritual, the mind and faith, because the texts that were found in the Dead Sea were also kept in such vessels. At five meters high, these vases are monstrous. Monstrous like the killings. I cannot understand it, but in this manner I have given my grandfather Isaak Brandes a little peace.

This painful family history is reflected in a drawing entitled Isaak, shown in an exhibit of Brandes’ works in the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in 1995. The figure, head bowed, neck bent at an angle of more than 90 degrees, served as the model for the images he later placed on the Yad Vashem vase. Here, two figures, one much larger than the other, stand facing each other, mirror-images except for their size, both heads bowed deeply before the other. With this expanded version of the drawing, Brandes linked his family history suggestively to the biblical motif of Abraham and Isaac. The bent, tormented, broken human being is the subject of many of Brandes’ works.

For a long time, the family believed that Isak’s wife Anna had also been deported and gassed. Peter Brandes relates:

Erst ein Jahr nach dem Krieg kam die Schwester [Eleonore] meines Vaters aus der Schweiz nach Paris zurück. Sie entdeckte ihre Mutter, wie sie in Mülltonnen nach Essbarem suchte. Das war ein Schock für beide, ein größerer für meine Großmutter, denn drei Tage nachdem sie gefunden worden war, versuchte sie, sich umzubringen.17

It was not until a year after the war that my father’s sister [Eleonore] returned to Paris from Switzerland. She discovered her mother searching through garbage cans for anything edible. It was a shock for both of them, but even more so for my grandmother because, three days after she was found, she attempted to take her own life.

But the family was reunited, and Peter Brandes got to know his grandmother as a child. From Denmark she moved to the US with her daughter Bertha, where she died a few months later in 1957. Her son Isidor Thomas Johannes died on 21 April 1980 in Denmark, his wife Gerda on November 29 2018.18

After many detours, Brandes was able to find his father’s cousin Rosa Hoffer19, then aged 85, in a retirement home in Israel. She was Paul Celan’s French teacher in Czernowitz. During the Ceauşescu regime, she was sold to Israel for foreign currency. There, she worked as an interpreter in the Eichmann trial, translating into Hebrew and French.20

2. Portraits of Hölderlin from His Time in the Zimmer House on the Neckar

Ja, die Gedichte sind echt, die sind von mir, aber der Name ist gefälscht, ich habe nie Hölderlin geheißen, sondern Scardanelli oder Scarivari oder Salvator Rosa oder so was.21

Yes, the poems are genuine, they are mine, but the name is fake, my name was never Hölderlin, but Scardanelli or Scarivari or Salvator Rosa or something like that.

With these words, Hölderlin accepted the first printed volume of his poems (Hölderlin 1826). Published in 1826 by Johann Friedrich Cotta, planned as early as 1801, but not published then for unknown reasons, the volume was brought to him by Christoph Theo-dor Schwab (1821–1883) in 184122, the son of Gustav Schwab (1792–1850). Hälfte des Lebens (Half of Life), probably Hölderlin‘s most well-known poem today, which has been translated into almost all languages of the world, and which was published in a pocket calendar in 1804, is not to be found in the volume. It did not stand up to the verdict of “wahnsinniger” (mad) poet and was simply deleted from the list compiled for the publication, which was to include all of Hölderlin’s poems previously published in almanacs. The cut is radical and divides Hölderlin’s life and work into two halves. No less striking is the division that separates the portraits of the young Hölderlin from those made of the old, sick poet in the Tower.

Let us first briefly consider the early portraits of Hölderlin: the young 16-year-old in the tinted pencil drawing from 1786, the 18-year-old captured in the pencil drawing by his childhood friend Immanuel Nast from 1788, the silhouette of Hölderlin as Magister from 1790, the pastel portrait by Franz Karl Hiemer from 1792, and finally a later silhouette, probably from 1797.23 Various junctures and events mark the time of their creation: entry into the monastery school in Maulbronn, graduation two years later, Masters examination, the pastel given as a gift at the wedding of Hölderlin’s sister. The occasion for the fifth portrait, the silhouette from 1797, is unknown. But here, Hölderlin’s hairstyle deserves note: the short-cut hair falling over the forehead is in keeping with the tradition since the French Revolution. From 1797 on, the admired, beautiful young man, of whom his fellow students said, “Wenn er vor Tische auf- und abgegangen, sei es gewesen, als schritte Apollo durch den Saal” ((Ring 1859, p. 159). When he walked up and down before dinner, it was as if Apollo were striding through the hall) was no longer depicted. Twenty-six years of silence. The break could scarcely be more visible, more obvious.

On September 15 1806, a closed carriage brought the court librarian Hölderlin from Bad Homburg to the University Clinic in Tübingen. There are several hypotheses regarding the reasons that led to his admission on that date (Franz 2024, pp. 270–76). Professor Johann Heinrich Ferdinand von Autenrieth (1772–1835), director of the University’s first psychiatric clinic, situated in the Alte Burse (bursary) and opened on May 13, 1805, was tasked with driving “die Poesie u[nd] die Narrheit zugleich”24 (both poetry and madness) out of Hölderlin, who was one of his first patients. The treatments ended after seven and a half months with the prognosis of “Manie” (mania), which would evolve into a kind of “Blödsinn” (idiocy). The “Furiose” (ravings) would cease over time; the patient would become completely “steif und torpid” (Fichtner 1980, p. 62; stiff and torpid). According to current medical knowledge, a diagnosis of schizophrenia can no longer be maintained, especially since the autopsy at the time had already pointed to an organically caused psycho-syndrome.

With Autenrieth’s declaration that “der Kranke werde höchstens noch drei Jahre leben” (StA 7.2, p. 377 [no. 361]; the patient would live for a maximum of three years), Hölderlin was placed under the care of the carpenter Ernst Friedrich Zimmer (1772–1838) and his family on May 3 1807; one could call it an open psychiatric hospital. One of Autenrieths insights was not to return the patients to their families, which he diagnosed as harmful, but if possible they should be taken into a family unit. Just a few steps from the Alte Burse (bursary), Hölderlin moved into the tower room on the second floor of the house on the Neckar, which his landlord had recently purchased. He lived there for 36 years until his death in 1843. He “fühlte die Erleichterung seiner Lage sehr deutlich und bewahrte eine unauslöschliche Dankbarkeit für seine treuen Pflegeältern”25 (felt the relief of his situation very clearly and retained an indelible gratitude for his loyal caretakers), says Schwab, who met the poet in the last two years of his life and prepared the first edition of his works.

Hölderlin was given the status of foster son in his hometown of Nürtingen. His mother’s application to the city was approved, as was her fifth application (after four unsuccessful tries, the first of which was made on November 29 1805) to the Stuttgart Consistory, the Royal Department of the Württemberg Church (StA 7.3, p. 110 [no. 514]). With the grant of 150 guilders per year from the Consistory, which was approved by decree on October 12 1806, in addition to Nürtingen’s “Pflegsohn” (foster son) allowance, Hölderlin’s living expenses were covered. Every quarter—on Candlemas, St. George’s Day, St. James’s Day, and St. Martin’s Day—Zimmer submitted bills for food, clothing, linen, tobacco, etc. to Hölderlin’s mother and, after her death in 1828, to the administrative guardian in Nürtingen. After Ernst Zimmer’s death in 1838, the youngest daughter Charlotte (1813–1879), also known as Lotte, took over Hölderlin’s care and cost accounting. Their communications were always accompanied by reports, some quite detailed, on Hölderlin’s condition, his daily life in the tower, and provided information about the visitors, who, in turn, gave rise to many legends about the poet. These reports are eloquent testimonies of the care and respect that Hölderlin received in the Zimmer house.

Zimmer had met Hölderlin in the Clinic, where he was doing carpentry work. He esteemed the poet, had read his Hyperion and, when introducing him to the Oberamtspfleger (district administrative guardian) in Nürtingen, noted with great respect that: “Die neusten Tag Blätter nennen Ihn den ersten Elegischen Dichter Deutschlands”26 (The latest newspapers call him the foremost elegiac poet in Germany).

Zimmer spoke repeatedly of Hölderlin’s poetry, as in this letter written in 1812:

Sein dichterischer Geist zeigt Sich noch immer thätig, so sah Er bey mir eine Zeichnung von einem Tempel Er sagte mir ich solte einen von Holz so machen, ich versetze Ihm drauf daß ich um Brod arbeiten müßte, ich sey nicht so glüklich so in Philosofischer ruhe zu leben wie Er, gleich versetze Er, Ach ich bin doch ein armer Mensch, und in der nehmlichen Minute schrieb Er mir folgenden Vers mit Bleistift auf ein Brett

Die Linien des Lebens sind Verschieden

Wie Wege sind, und wie der Berge Gränzen.

Was Hir wir sind kan dort ein Gott ergänzen

Mit Harmonien und ewigem Lohn und Frieden.27

His poetic spirit is still active. Once he saw a drawing of a temple in my house. He told me I should make one out of wood like that, I told him I had to work for my bread, I was not as lucky to live in philosophical peace as he was; he immediately replied, oh, but I am a poor man, and at that same moment he wrote the following verse in pencil on a board for me:

The lines of life are various; they diverge and cease

Like footpaths and the mountains‘ utmost ends.

What here we are, elsewhere a God amends

With harmonies, eternal recompense and peace.(Hölderlin 2004, p. 745)

In a letter (to an unknown person dated December 22 1835) Zimmer presented an overview of Hölderlin’s life, emphasizing his relationship to nature:

Hölderlin war und ist noch ein großer Natur Freund und kan in seinem Zimmer daß ganze Näkerthal samt dem Steinlacher Thal übersehen. […] jezt ist es 30 Jahr daß er bei mir ist. Ich habe keine Beschwerlichkeiten mehr von ihm, aber früher war er oft Rasend, daß Blut stieg ihm so in Kopf daß er oft ziegelroth aussah und dan alles Beleidigte was ihm ingegen kam. War aber der Paroxismus vorbei, so war er auch immer der erste welcher die Hand zur versühnung Bot. Hölderlin ist Edelherzig hat ein tiefes Gemüth, und einen ganz gesunden Körper, ist so lang er bei mir ist, nie krank geweßen. Seine Gestalt ist schön u. wohlgebaut, ich hatte noch kein schöneres Auge bei einem sterblichen gesehen als Hölderlin hatte; Er ist jezt 65 Jahre alt ist aber noch so munter und lebhaft als wenn er erst 30 wäre Daß Gedicht daß beifolgt hat er in 12 Minuten niedergeschriben, ich foderde ihn dazu auf mir auch wieder etwas zu schreiben, er machte nur daß Fenster auf, that einen Blick ins Freue, und in 12 Minuten war es fertig. Hölderlin hat keine Fixe Idee, er mag seine Fantasie auf Kosten des Verstandts bereichert haben.28

Hölderlin was and still is a great friend of nature and can look out over the entire Neckar valley, including the Steinlach valley, from his room. […] It is now 30 years since he has been with me. I have no more problems with him, but in the past he often raged, the blood rushed so much to his head that he often turned brick red and then everything that came his way he insulted. But when the paroxysm had passed, he was always the first to offer a hand of reconciliation. Hölderlin is noble-hearted, has deep soul and a completely healthy body, and has never been ill as long as he has been with me. His form is beautiful and well-built; I have never seen more beautiful eyes in a mortal than Hölderlin’s. He is now 65 years old but is still as sprightly and lively as if he were only 30. He wrote the poem that follows in 12 minutes, I requested him to write something again for me, he just opened the window, looked out into the free air, and in 12 minutes it was finished. Hölderlin has no idée fixe, he might have enriched his imagination at the expense of his reason.

Hölderlin’s epistolary novel Hyperion oder der Eremit in Griechenland (Hyperion or the Hermit in Greece) (1797/1799) was republished by Cotta in 1822 with great success. We know that, beginning in May 1822, Wilhelm Waiblinger (1804–1830) was working on his novel Phaëton (finished in a few weeks, published in 1823), in which he discussed Hölderlin’s fate. Nothing was more important to him, he said, than to portray a poet, a “Hölderlin, der da wahnsinnig wird aus Gottestrunkenheit, aus Liebe und aus Streben nach dem Göttlichen.”29 (a Hölderlin, who goes mad from being intoxicated with God, from love, and from striving after the divine.) He included a “Bogen” (sheet) from Hölderlin‘s papers in his Phaëton: the three text segments “In lieblicher Bläue blühet …” (StA 2.1, pp. 372–74; Blooming in lovely blueness …).

Waiblinger’s assessment of Hyperion and its author is as follows:

Der Hyperion verdient die Unsterblichkeit so gut als Werther, und besser als die Messiade. […] Hölderlin ist einer der trunkenen, gottbeseelten Menschen, wie wenig die Erde hervorbringt, der geweihte heilige Priester der heiligen Natur!30

Hyperion deserves immortality as much as [Goethe’s] Werther, and more so than [Klopstock’s] Messiah. […] Hölderlin is one of the inebriated, god-inspired people that the earth so rarely produces, the consecrated holy priest of holy nature!

He reports from his visits that Hölderlin reads “viel in seinem Hyperion”31: “Hyperion liegt beynahe immer aufgeschlagen da. Er las mir oft daraus vor”32 (a great deal in his Hyperion; Hyperion is almost always lying open. He often reads from it to me).

Waiblinger may be the first of Hölderlin’s biographers to visit him during his own time as a student at the Stift (Seminary; 1822–1826). His portrayal of him in his biography (written retrospectively in Rome in 1827 and published posthumously in 1831) was certainly exaggerated. He often took him for walks to his garden house in Tübingen, the so-called Presselsche Gartenhaus (Pressel’s garden house), later retraced by Hermann Hesse in his story by the same name. Waiblinger reports:

Die Natur, ein hübscher Spaziergang, der freye Himmel that ihm immer gut. Ein Glück für ihn ist es, daß er von seinem Zimmerchen aus eine wirklich recht lachende Aussicht auf den Neckar, der sein Haus bespült, und auf ein liebliches Stück Wiesen- und Berglandschaft genießt. Davon gehen noch eine Menge klarer und wahrer Bilder in die Gedichte über, die er schreibt, wenn ihm der Tischler Papier gibt.33

Nature, a pleasant walk, the open sky always did him good. It is fortunate for him that from his little room he enjoys a really lovely view of the Neckar, which washes up against his house, and of a lovely slice of meadow and mountain landscape. Many clear and true images of all this pass over into the poems that he writes when the carpenter gives him paper.

This “when” is not entirely insignificant, because deprivation of paper and the reading of Bible verses were part of his prescribed therapy. He seems to have dashed off the verses with ease, tapping out the meter beforehand with his hand on the desk. He willingly obliged the requests of visitors, even letting them choose from among the topics he suggested—and then gave the paper away.

Difficulties appeared to have ensued with his signature. Schwab noted in a diary entry that Hölderlin became “ganz rasend” (utterly enraged) when he asked him to sign his name under the poems Höheres Leben (Higher Life) and Höhere Menschheit (Higher Humanity), and that finally he “schrieb in seiner Wuth den Namen Skardanelli darunter”34 (in his fury wrote the name Skardanelli beneath [them]). Hölderlin also called himself “Killalusimeno” or “Buonarotti.” But he consistently signed with “Scardanelli” and fictitious dates in the last years of his life. This suggestive name has elicited a wealth of hypotheses right up to the present: one hears in it the Romansh place name Scardanal, derived from a verb meaning “to clear” or “to renew”, or one looks for evidence in semantically evocative verbs such as the Italian scardassare (to comb wool), an activity often carried out by the mentally ill, or scardinare (to unhinge, to go out of joint), or the French sortir de ses gonds, which means “to go crazy”. And the list goes on.

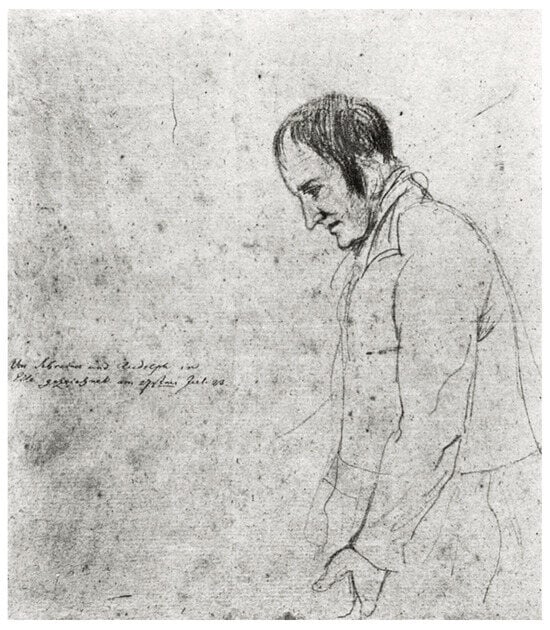

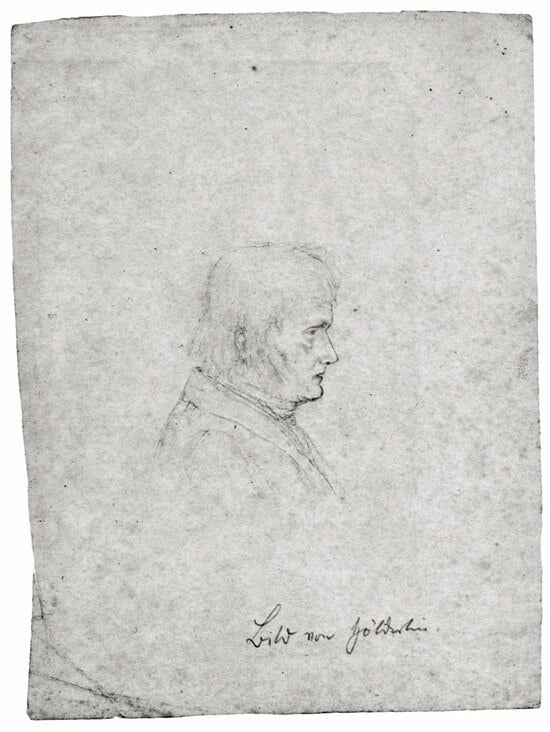

Johann Georg Schreiner (1801–1863) and Rudolf Lohbauer (1802–1873), friends of Eduard Mörike (1804–1875)—Lohbauer painted the watercolor Hyperion auf der Überfahrt nach Kalaurea (Hyperion on the Crossing to Kalaurea) (1824)—made a pencil drawing of Hölderlin on July 27, 1823 (Figure 1). Mörike himself reported (April 7 1832):

Rudolf Lohbauer und G. Schreiner (Lithograph) besuchten mich in Tübingen; ich führte sie auch zu Hölderlin; nachher zeichneten sie, gleichsam wehmütig spielend, das Profil des armen Mannes miteinander auf einen Wisch Papier.35

Rudolf Lohbauer and G. Schreiner (lithographer) visited me in Tübingen; I also took them to Hölderlin; afterwards, playing around wistfully, they drew the poor man’s profile together on a piece of paper.

Figure 1.

Hölderlin. Pencil drawing, Schreiner and Lohbauer, 1823.

It is the first surviving portrait from the tower period, and shows the fifty-three-year-old in a slightly forward-leaning position with his head bowed, a high forehead, a clear profile and an inward-looking gaze that speaks of “Schwermut und Schmerz, erschütternde Hilflosigkeit und Ergebenheit”36 (melancholy and pain, heartrending helplessness and resignation), comments Adolf Beck. He goes on to say that the “Zeichnung ist nach Mörikes Beischrift ‘in Eile‘ gemacht und vorwiegend auf Umrisse beschränkt” (according to Mörike’s caption, the drawing was made “in a hurry” and is mainly limited to outlines). For this reason—thus he interprets the drawing and contrasts it with the following one, made by Schreiner two years later—Hölderlin’s “Zerrüttung [ist] kaum sichtbar”37 (deterioration is scarcely visible).

The position of the hand has led to a variety of interpretations: a gesture of giving could be meant, but it could also be interpreted as the supporting hand on the back of a chair.

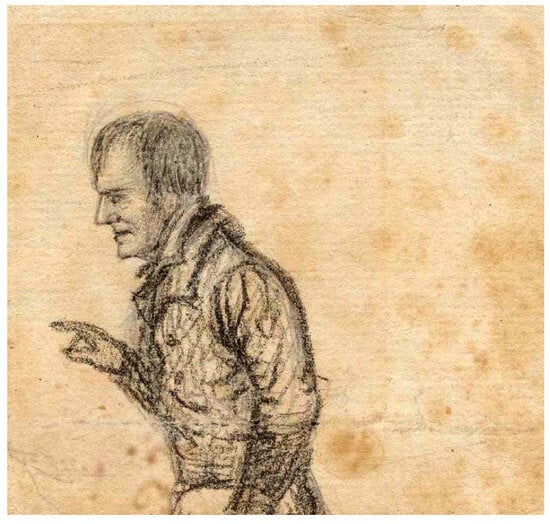

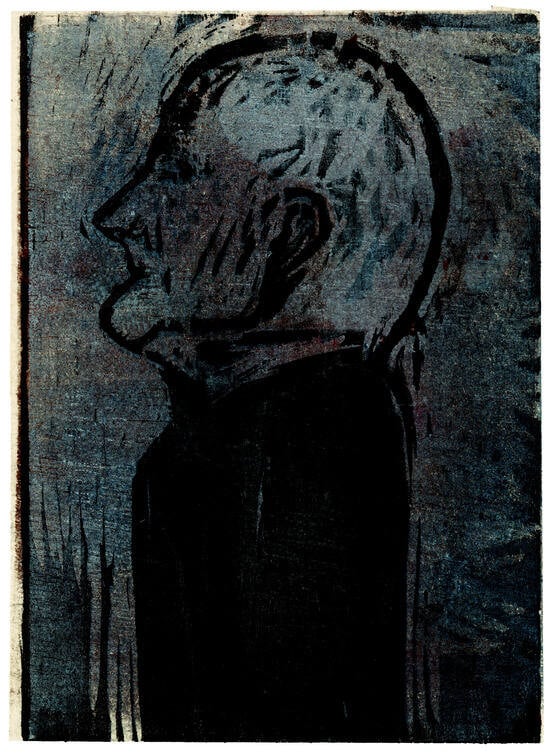

Hölderlin’s striking a pose of declamation is documented several times: “Hölderlin unterhält sich mit Fortepiano Spiel und zuweilen auch mit Deklamiren oft auch mit Zeichnen”38 (Hölderlin entertains himself by playing the piano and sometimes by declaiming, often by drawing). This passage from a letter is reminiscent of the charcoal drawing from 1825/1826 by the painter, draftsman and lithographer Johann Georg Schreiner, an “alte[r] Freund” (old friend) of Mörike‘s from Ludwigsburg, who made a drawing of Mörike in 1824. As in 1823, Mörike also introduced Schreiner to Hölderlin. He reported that Schreiner made the sketch at his (Mörike’s) desk “gleich nachher aus frischester Erinnerung” (immediately afterwards, from freshest memory; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Hölderlin. Black chalk over pencil by Schreiner, 1825/1826.

In the magazine Freya from 1873, Mörike wrote that Hölderlin was “sehr gut getroffen” (very well captured), emphasizing that “besonders die Haltung” (particularly his posture) with its demonstrative hand gesture was very characteristic, “worin sich das Bemühen zeigt, einem subtilen Gedanken den gehörigen Ausdruck zu geben”39 (which shows the effort to give a subtle thought appropriate expression). Beck observes that “[i]n der Zerfurchung des Antlitzes ist die innere Zerrüttung diesmal ergreifend getroffen. Ungemein beredt die deutende rechte Hand”40 (Here, the furrowed face captures the inner deterioration movingly. The pointing right hand is extremely eloquent).

We also hear repeatedly from Zimmer about Hölderlin’s appearance:

Seine körperliche Kräften sind noch immer gut auch hat er noch imer einen starken Apedit, in seinem Gesicht Ältert Er etwas, weil Er die vodere Zähne verlohren hat, stehen die Lippen einwärz und daß Kenn hervor.41

His physical strength is still good and he still has a good appetite. He is aging a little in his face because he has lost his front teeth, his lips are sunken and his chin is prominent.

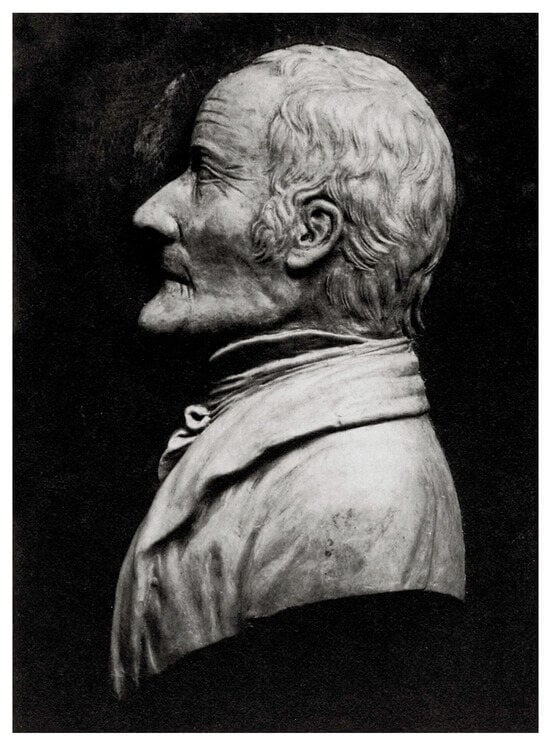

This provides the context for viewing the wax relief (Figure 3) of the aged Hölderlin, created by Wilhelm Paul Neubert (1808–1895) around 1840, in any case after 1838. On the back of the glazed, black-lacquered frame in which the relief (H. 12 × W. 6.5 cm) has been preserved, is inscribed: “Nach dem Leben modelliert” (Modeled from life). Neubert was a zoologist and botanist who also practiced the old craft of embossing, the art of wax modeling. He lived in Tübingen from 1832 and became well known through his Deutsches Magazin für Garten- und Blumenkunde (1850; German Magazine for Gardening and Floriculture), published by Cotta, which continues to be published to this day. He also made a bronze medallion of Hölderlin (H. 16.2 × W. 13.2 × D. 2.8 cm), based on the wax relief.

Figure 3.

Hölderlin. Wax relief by Neubert, around 1840.

The description by the young Schwab in his diary from January 14 1841 parallels what we see in Neubert’s relief:

Ich faßte seine Physiognomie recht scharf in’s Auge, es war mir anfangs schwer, mich darein zu finden, weil ich mir das jugendlich schöne Bild nicht gleich verscheuchen konnte, doch überwand ich mich und beachtete die tiefen Runzeln seines Gesichtes nicht mehr. Die Stirn ist hoch und ganz senkrecht, die Nase sehr regelmäßig, ziemlich stark, aber in ganz gerader Linie vorgehend, der Mund klein und fein und wie das Kinn und die untern Theile des Gesichts überhaupt sehr zart. Einigemal, besonders, wenn er einen recht melodischen Passus ausgeführt hatte, sah er mich an; seine Augen, die von grauer Farbe sind, haben einen matten Glanz, aber ohne Energie, und das Weiße daran sieht so wächsern aus, daß mich schauerte.42

I took a very close look at his physiognomy, it was difficult at first to get used to it because I couldn’t immediately banish the youthful, beautiful image, but I overcame myself and no longer noticed the deep wrinkles in his face. The forehead is high and completely vertical, the nose very regular, quite strong, but completely straight, the mouth small and fine and, like the chin and the lower parts of the face, very delicate. A few times, especially after he had performed a very melodic passage, he looked at me; his eyes, which are grey in color, have a dull shine but without energy, and the whites of them look so waxy that I shuddered.

A week later, on January 21, impressed by Hölderlin’s eyes and his evasive, wandering gaze, he wrote:

Was mir hauptsächlich auffiel, war, daß man ihn mit Blicken gar nicht recht fassen konnte, weil sein Auge gar keinen fixen Stern hat, wie es auch seiner Seele ganz an Sammlung und Concentration fehlt.43

What particularly struck me was that one could not really apprehend him with one’s gaze, because his eye has no fixed stare at all, just as his soul completely lacks concentration and focus.

The fourth portrait of Hölderlin during his time in the tower was made by the artist Louise Keller. It is a pencil drawing (Figure 4), made in 1842, the only one intended for publication.

Figure 4.

Hölderlin. Pencil drawing by Louise Keller, 1842.

Although Schwab could not have seen Keller’s pencil drawing at the time he wrote in his diary, it confirms his precise observation of Hölderlin’s physiognomy, including his “Runzeln” (wrinkles). Keller shows the figure bent slightly forward, the gaze absent, perhaps with a wandering expression, sparse hair, the small, perhaps twitching mouth. Waiblinger’s description confirms what we see here:

Man bewundert das Profil, die hohe gedankenschwere Stirne, das freundliche freylich erloschene, aber noch nicht seelenlose liebe Auge; man sieht die verwüstenden Spuren der geistigen Krankheit in den Wangen, am Mund, an der Nase, über dem Auge, wo ein drückender schmerzlicher Zug liegt, und gewahrt mit Bedauren und Trauer die convulsivische Bewegung.44

One admires the profile, the high, deeply thoughtful forehead, the friendly, admittedly extinguished, but not yet soulless, kind eye; one sees the ravaging traces of mental illness in the cheeks, on the mouth, on the nose, above the eye, where there is an oppressing, painful expression, and one notices the convulsive movement with regret and sadness.

Based on Keller’s pencil drawing, Karl Mayer (1798–1868) made a steel engraving showing Hölderlin in an upright posture, with neat hair and a watchful eye, which was used on the cover of Hölderlin’s second edition of poems in 1843. Mayer also made a steel engraving based on a drawing after Hiemer’s pastel picture from 1792, which Louise Keller had been commissioned to make shortly after Hölderlin’s death.

Hölderlin’s latest poems from the period between 1806 and 1843 were long regarded by researchers as documents of illness—and Mörike was not the only one who contributed to this view with his verdict of “äußerst mattes Zeug”45 (extremely dull stuff). Gustav Schwab, on the other hand, “war einer der ganz wenigen, die sich ohne Einschränkung lobend über die Spätestgedichte äußerten.”46 (was one of the very few who spoke with unreserved praise for the very latest poems). While they have long aroused keen interest in the arts, it was only in the 1970s that they were sporadically subjected to literary–historical analysis and interpretation as Turmgedichte (tower poems), and recently their “Kunstcharakter” (Oelmann 1996, pp. 203, 212); artistic character) has been highlighted. The first monograph on the tower poems, published in 2006, interprets these latest poems in the context of “dietetics” (Oestersandfort 2006): as part of the ailing poet’s self-therapy.

The origin of the texts suggests that they are occasional poems, arising from the contemplation of “manche[n] schöne[n] Bilder[n]”47 (various beautiful images) of nature. Contemporaries repeatedly emphasize the “beautiful view”48 Hölderlin enjoyed from his tower windows. While the pictorial character of the poems is recognized, it is reduced to mere mimesis. The poems’ dates and captions, perhaps interpreted as detached from space, time, and person, could be investigated further. They are often dated to the period around 1750. One poem, for example, bears the date “November 15 1759”—Friedrich Schiller was born on November 10 of that year. In all, five poems are dated 1758; the historical context of that year would be worth investigating. Not least, it should be noted that the poems Aussicht and Die Aussicht are dated 1671 and 1748. It might prove worthwhile to take a look at the records from the 18th and 19th centuries, too, as the “6” could easily be read as the usual horizontal “8.” Furthermore, in the year “1671”, the “7” is not clearly identifiable and could be read as a “4.” This would make the reading “1841” possible. But enough speculation.

The nearly 60 surviving texts from the period between 1806 and 1843 must be viewed as a fraction of a much larger corpus. Despite gaps—laundry baskets of papers were thrown out after Hölderlin’s death—what has survived can be divided into two widely separated work phases: twenty texts fall into the years up to 1812, 28 into the years after 1841, and seven into the period in between. Whether this interim period can be interpreted as a period of silence remains an open question due to the small textual basis.

The 27 “Scardanelli” poems, two thirds of which are dedicated to the seasons, belong to the second phase of work. The signatures look like inscriptions on the base of a monument: dated monuments with an emblematic function? They share a cyclical structure; each individual poem treats the season named in the title, but also anticipates the following one. How do they present nature and man?

Man remains distinct and separate from nature, but he should “sich […] zu diesem Sinn [finden]” (StA 2.1, p. 301; find the way to this meaning)—so we read in these latest tower poems, which deal with the coexistence of man with nature. These are not nature poems that describe a landscape or convey an experience of nature. Their subject is the passage of time itself, which is outfitted with the apparent: adornment, ornamentation, splendor, brilliance. But they do not depict the perception, contemplation, or view of a landscape. The concrete sight—the study of nature—and the idea of a “höheres Erscheinen” (“higher appearance”) penetrate each other progressively over the course of the seasons and their cyclical return, approaching the image of the image. Man and nature are signs of one spirit. Man should find the way to the meaning of himself and of nature (Lawitschka 2009, p. 63). Hölderlin ends one of his latest poems, Der Herbst (Autumn) with the line: “Und die Vollkommenheit ist ohne Klage” (StA 2.1, p. 284; And perfection is without complaint.)

3. Brandes’ Bildgespräche (Picture Conversations) with Hölderlin and His Woodcuts

Brandes’ Bildgespräche (picture conversations) with Hölderlin began in October 2007 in the Hölderlin Tower in Tübingen. A concert is given: musical settings of Hölderlin by Hanns Eisler. Brandes sits in the room that documents Hölderlin’s time in the tower, directly in front of the case in which the pencil drawing by Schreiner and Lohbauer from 1823 (see Figure 1) is displayed. He pulls out his notepad and starts sketching.

In the space of two years he created over 100 works that have their starting point and source of inspiration in the four portraits of Hölderlin from the tower period, focusing also on the poems that were created there. The four portraits of Hölderlin are not only the starting point, but also the subject of the Bildgespräche that Peter Brandes conducted with the poet and his texts.49

We have spoken of the master carpenter Zimmer, who worked with wood, and the wooden board on which Hölderlin wrote verses. Is it not a happy coincidence that Hölderlin, during his student days (1788–1793) at the Evangelisches Seminar (Protestant Seminary) in Tübingen, belonged to a poets’ association—modeled on Klopstock’s Republic of Scholars—with his friends Rudolf Friedrich Heinrich Magenau (1767–1846) and Christian Ludwig Neuffer (1769–1839), where he was known by the nickname “Holz” (wood)? And in very fact there is a drawing by Magenau appended to his letter to Neuffer from November 15, 1790, which shows a seminarian attired in an academic gown at a desk in front of a wall of books. On one of the spines in the top row we read “Holz” (Beck and Raabe 1970, p. 158, Figure 55; wood).

Sufficient allusions to justify Brandes’ choice of the woodcut. But the artist chose this medium for entirely different reasons. As he explained:

Zahlreiche romanische Granitskulpturen—in Dänemark vor allem mit christlicher Kunst motivisch verbunden—bilden ein künstlerisches Testament besonderer Stärke. Als dänischer Künstler muss man sich stets an diesen Werken, als wären sie Wegmarken, orientieren.

Eine Sandsteinskulptur, die im Freien steht, kann das dänische Klima nicht überstehen. Der Granit hingegen, der mit den Gletschern der Eiszeit aus Norwegen und Schweden bis in unser Land gebracht wurde und verstreut in der Landschaft zurückblieb, trotzt dem Frost, dem Wind und dem Salz des Meeres.

Die ’aufrecht stehenden‘ lakonischen Aussagen und Gedichte unserer Runeninschriften, die bis heute der Landschaft eingeschrieben sind, nutzen ebenfalls den Granit. Es versteht sich von selbst, dass ein so widerständiges Material wie der Granit, eine kraftvolle Einfachheit ausstrahlt, wenn er gekonnt verarbeitet ist. Hier gibt es keine überflüssigen Details.

Wenn ich für meine Bildgespräche mit Hölderlins letzten Gedichten, seinen sogenannten Turmgedichten, die Holzschnitttechnik gewählt habe, geschah es aus der Überzeugung, dass man im Charakter des Holzschnitts dieselbe einfache Kraft findet, die den Granit und die Turmgedichte kennzeichnet. Die gleiche Einfachheit und Stärke findet man in den Aussagen der Runen wieder. Als bilde das Ganze einen Kreis. Anfang und Ende, Leben und Tod sind durch ausgemeißelte ’Wegmarken‘ der Erinnerung miteinander verbunden. Gezeiten.

Die letzten Gedichte Hölderlins können, denke ich, nicht in gleicher Weise interpretiert werden, wie die Werke des bis 1806 noch bewusst gewesenen Dichters. Für einen bildenden Künstler bedeutet dies ein Ausschließen des Anekdotischen oder des Illustrativen als Methode. Eine illustrative Übereinstimmung mit einem Text interessiert mich nicht.

Als Bezeichnung meiner die späten Gedichte Hölderlins begleitenden Holzschnitte verwende ich deswegen den Ausdruck Bildgespräche.(Brandes 2009, p. 70)

Numerous Romanesque granite sculptures—in Denmark, the motifs of which are largely tied to Christian art—constitute an artistic testament of particular strength. As a Danish artist, one must always orient oneself to these works as if they were milestones.

A sandstone sculpture that stands outdoors cannot survive the Danish climate. Granite, on the other hand, which was brought to our country from Norway and Sweden with the glaciers of the Ice Age and remained scattered throughout the landscape, defies the frost, the wind and the salt of the sea.

The ‘upright’ laconic statements and poems of our runic inscriptions, which are still inscribed in the landscape today, also use granite. It goes without saying that a material as resilient as granite radiates a powerful simplicity when it is skillfully crafted. There are no superfluous details here.

When I chose the woodcut technique for my Bildgespräche with Hölderlin’s last poems, his so-called tower poems, it was out of the conviction that one can find the same simple power in the character of the woodcut that characterizes both the granite and the tower poems. This same simplicity and strength can be found in the runic texts. As if the whole formed a circle. Beginning and end, life and death are connected by chiseled ’milestones’ of memory. Ebb and flow.

Hölderlin’s last poems cannot, I believe, be interpreted in the same way as the works of the still cognizant poet up to 1806. For a visual artist, this means excluding anecdote or illustration as a method. I am not interested in an illustrative congruence to a text.

For this reason, I use the term Bildgespräche to describe my woodcuts accompanying Hölderlin’s late poems.

In the catalogue (Brandes 2009) produced for the exhibition (2009) of Brandes‘ picture conversations, Hölderlin’s entire late work is printed in accordance with the Frankfurter Hölderlin-Ausgabe (Frankfurt Hölderlin edition, FHA).

Characteristic of Brandes’ work are sketches and preliminary work and a “lange Reihe von Versuchen mit mehreren Holzstöcken und unterschiedlichen Farbkombinationen” (Brandes 2009, p. 71; long series of experiments with several woodblocks and different color combinations). Often he began with a drawing (as we find with Edvard Munch, for example) or a watercolor. Brandes considered such experiments, although preliminary stages, to be “finished” results. Of this he stated:

Solche Ergebnisse sind aber relativ, ebenso wie die Deutungen von Hölderlins Turmgedichten es immer sein müssen. Die Art dieses Entstehungsprozesses verrät etwas über meine Einstellung zur Illustration von Texten.(Brandes 2009, p. 71)

Such results are relative, just as the interpretations of Hölderlin’s tower poems always must be. The nature of this creative process reveals something about my attitude toward illustrating texts.

Let us take a brief detour here to consider other important woodcutters who worked on Hölderlin. One example is HAP Grieshaber (1909–1981), who revolutionized woodcuts in the 20th century. He realized his distinctive visual language in life-size abstract woodcuts depicting man, tormented and abused, in flaming red. Among his various works on Hölderlin is the black-and-white woodcut Blumen für Hölderlin (Flowers for Hölderlin), which bears this title inscription in the lower left margin. Grieshaber created, among other works, the palm tree, a symbol of the University of Tübingen since the 15th century—and his student Manfred Degenhardt used the woodcut medium almost exclusively for his work.

A far lesser-known woodcutter is Erich Walz (1927–2011), who created several cycles on Hölderlin: a woodcut series I[m] N[amen] H[Hölderlins] (1983) (In the Name of Hölderlin) and, among others, one on the poem Colomb (1985).50 He drew inspiration from such lines as “Gefäße machet ein Künstler”51 (Vessels are made by an artist) or we are “Gestalten”, “Gefäße […], voll von Bildern” (1983) (Figures, vessels […] full of images). The pithoi he had seen in Crete served as his model: ancient storage vessels for wine, oil, and grain, regionally also used as burial vessels. He sought to transform Hölderlin’s linguistic image into a kind of archetype through extreme reduction, going beyond the word. Color—pastel tones or earth tones—maintains a cautious tension with the white, unprinted paper. On individual sheets, the artist also addressed the relationship between Diotima and Hölderlin and Hölderlin’s enthusiasm for the Greeks. Walz’s woodcut Hälfte des Lebens (Half of Life) depicts the two halves of Hölderlin’s life, as in the poem: two evenly divided imagistic spaces, summer (7 verses) and the question posed to winter (7 verses), ending with the Adonic cry of lament (StA 2.1, p. 117).

Let us return—after this brief excursion—to Brandes’ method in creating his woodcuts. He was attempting an “Annäherung an eine Bildsynthese” (approach to an image synthesis), a “Neu-Interpretationen eines Gesichts, dessen Züge [er] nie gekannt habe” (new interpretations of a face whose features [he] had never known). It is self-evident, and Brandes states it consciously and explicitly: “Die Arbeiten können nie eine Endgültigkeit erreichen” (Brandes 2009, p. 71; The works can never attain finality).

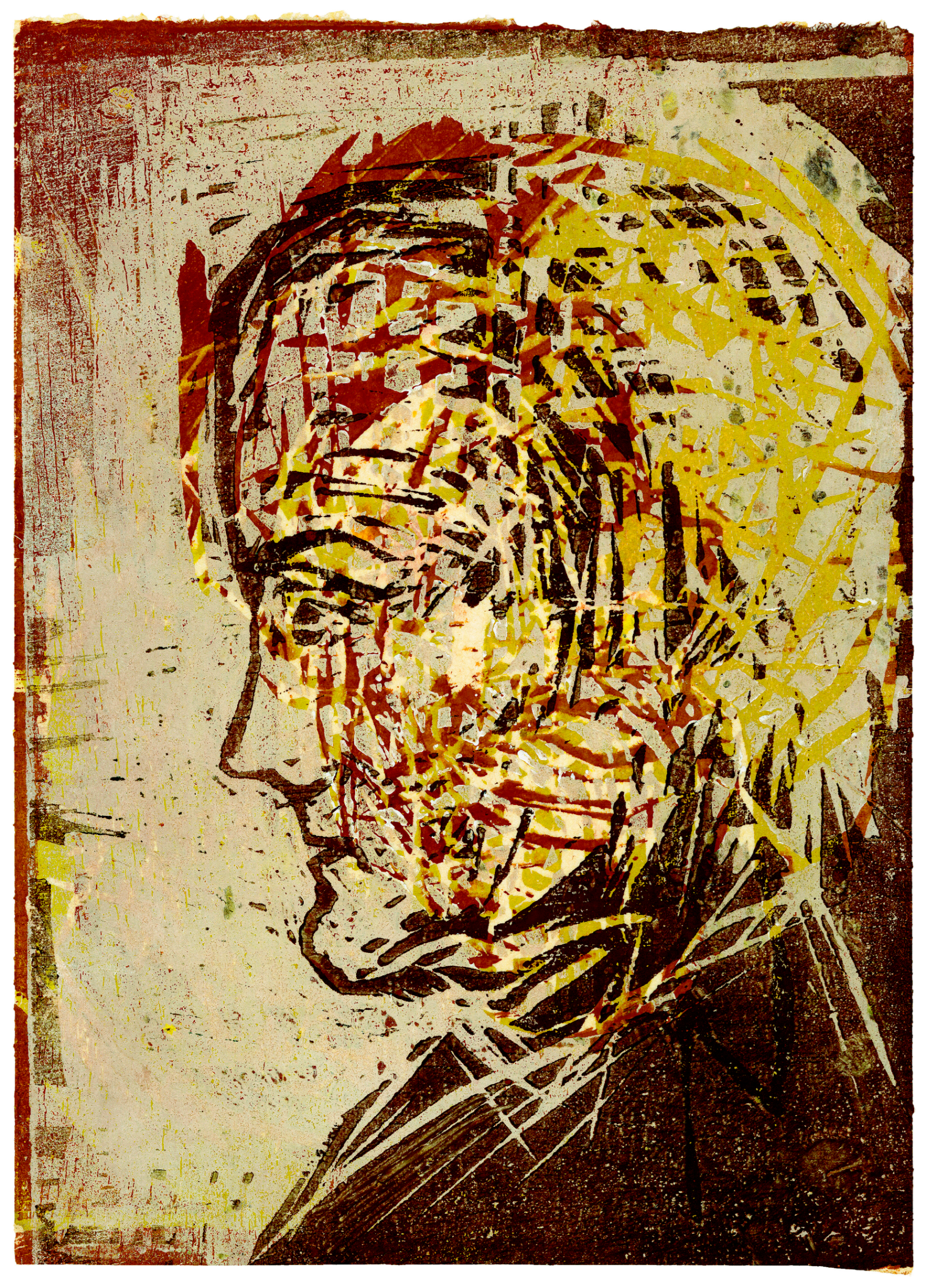

For each of the four portraits of Hölderlin in his old age, Brandes created runs of woodcuts—a thoroughly serial process—in the same format (H. 27.2 × W. 20.0 cm), up to twenty cuts for each portrait, with the color scheme varying greatly. The arrangement of poems and images was given careful consideration, both for the exhibit and the catalogue: a conversation can begin.

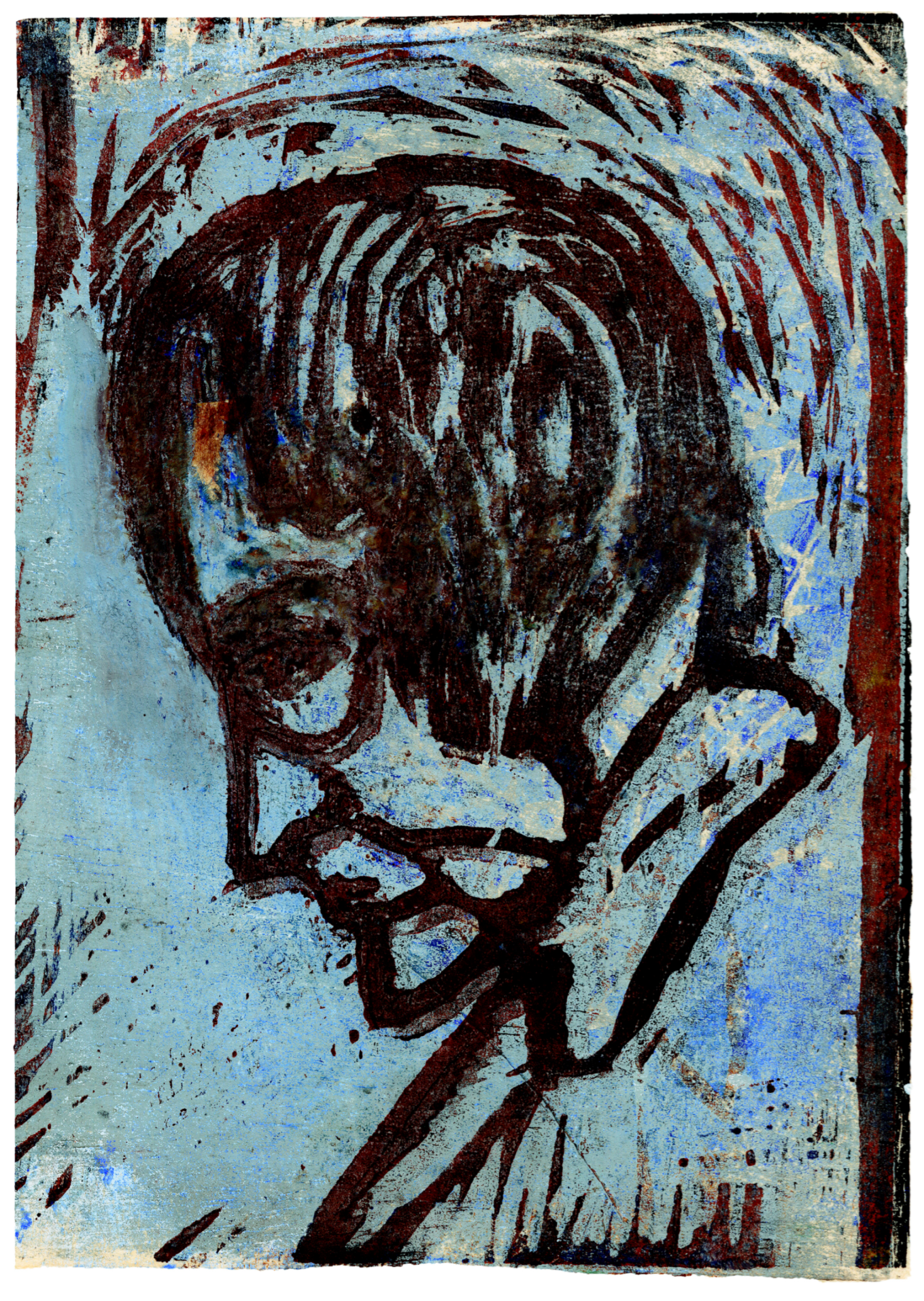

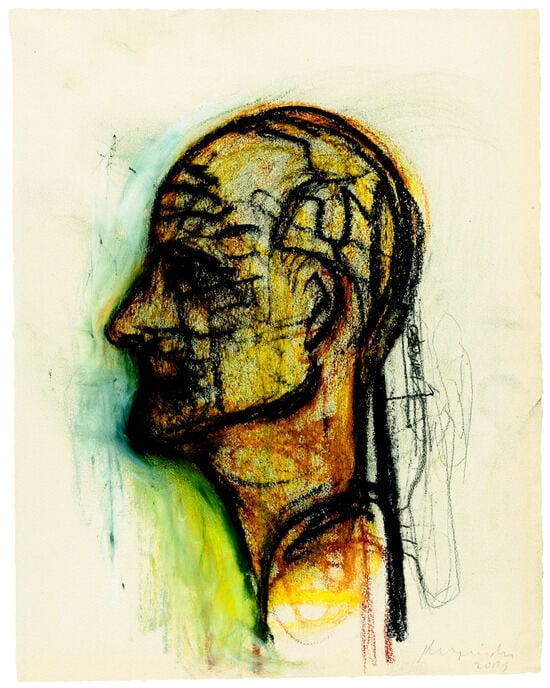

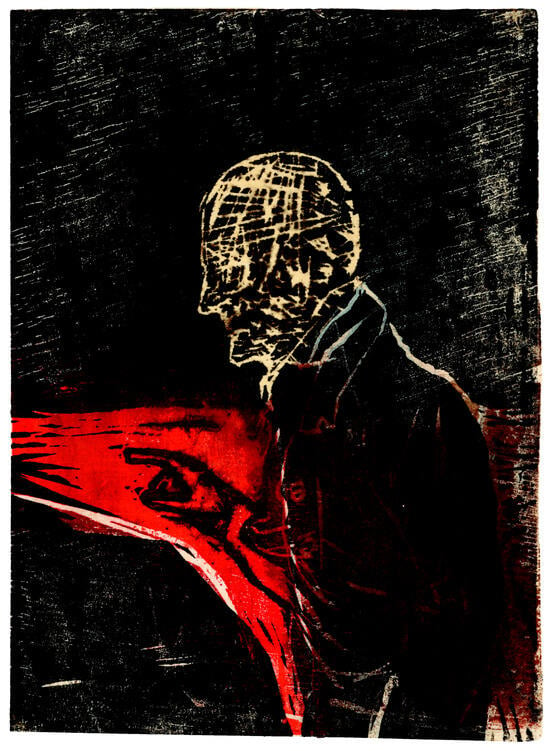

In his various interpretations of the four portraits of Hölderlin, the head and face naturally play the central role. Covered as if with netting, or even barred, they are divided into individual fields, the brain zones into segments and chambers, thought chambers. These depictions—veritable dissections—are reminiscent of the anatomist and writer Georg Büchner, whose Danton, pointing to Juliet’s “Stirn und Augen” (forehead and eyes), says: “da, was liegt hinter dem? […] Wir müßten uns die Schädeldecken aufbrechen und die Gedanken einander aus den Hirnfasern zerren” (Büchner [1965] 1969, p. 6); there, what lies behind that? […] We would have to pry open our skulls and tear out each other’s thoughts from our brain fibers). The eye, as if framed by the leaden cames of stained-glass windows, intensifies its gaze. (Figure 5, cf. Figure 1).

Figure 5.

Brandes: FH. Woodcut, 2009. (To Figure 1).

The series begins with a strong contouring of the face, which is gradually reduced in the subsequent depictions, until the visage is covered only by the sheerest, most delicate veil; the color gradation moves from strong to fading light blue. Brandes experiments and plays.

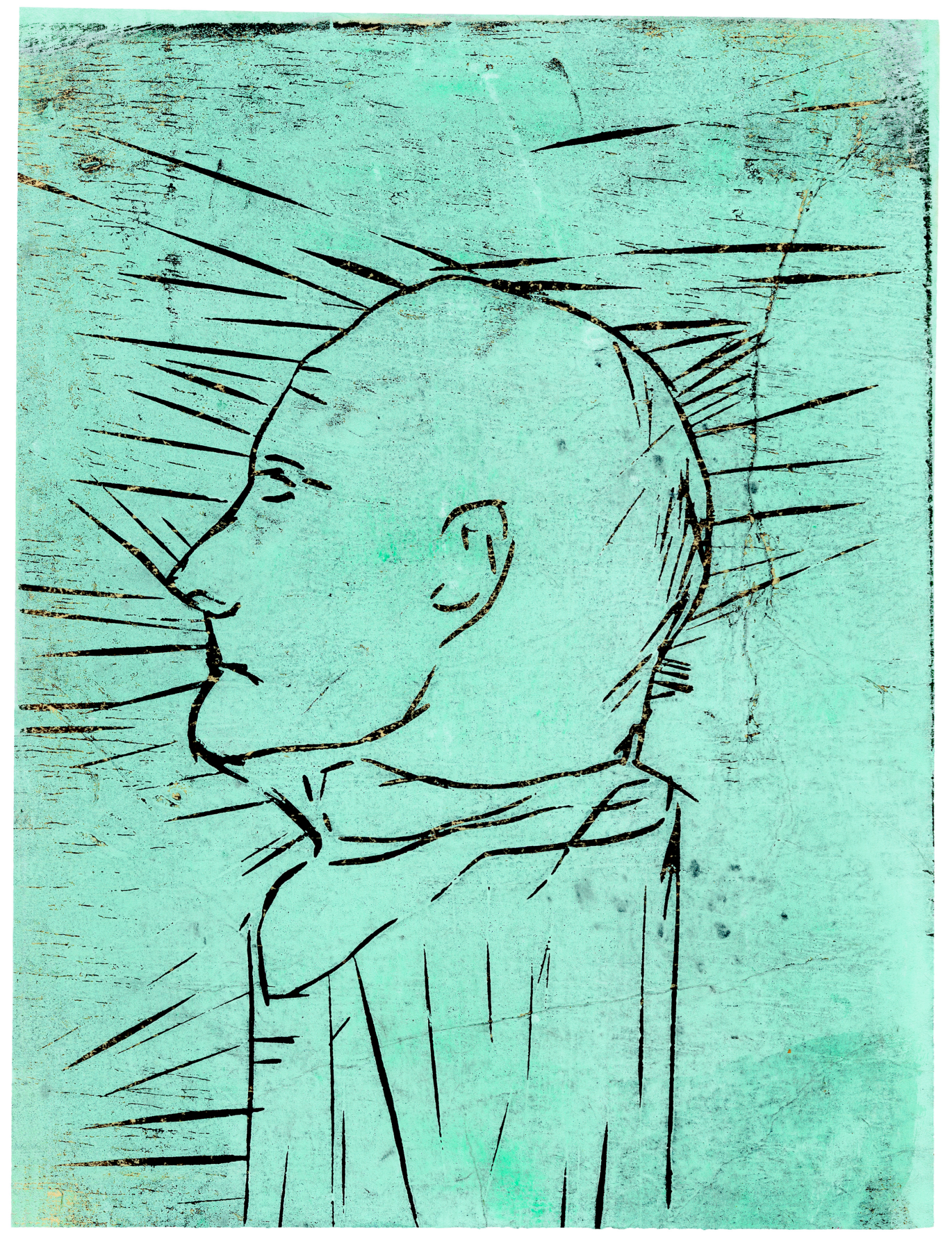

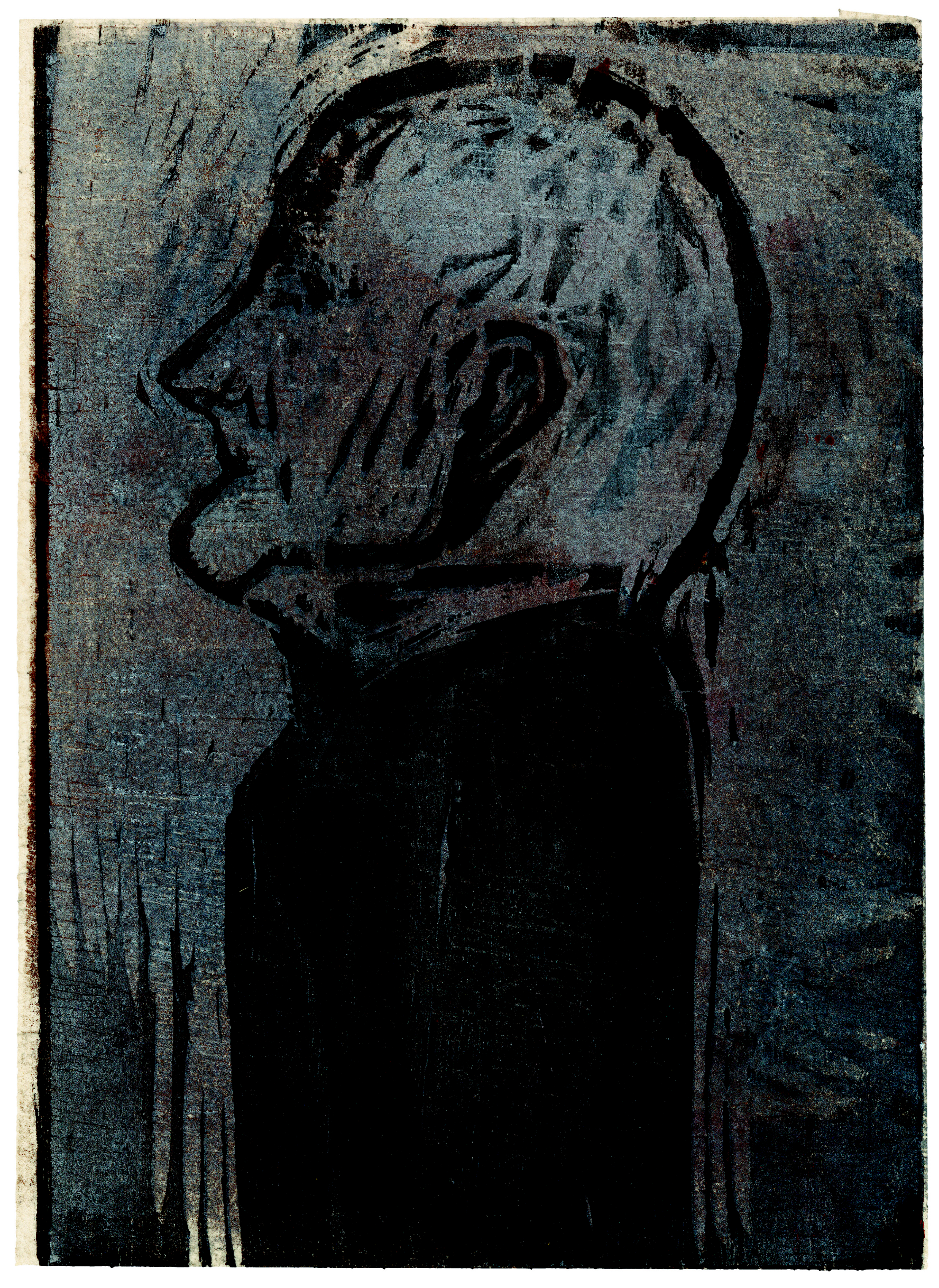

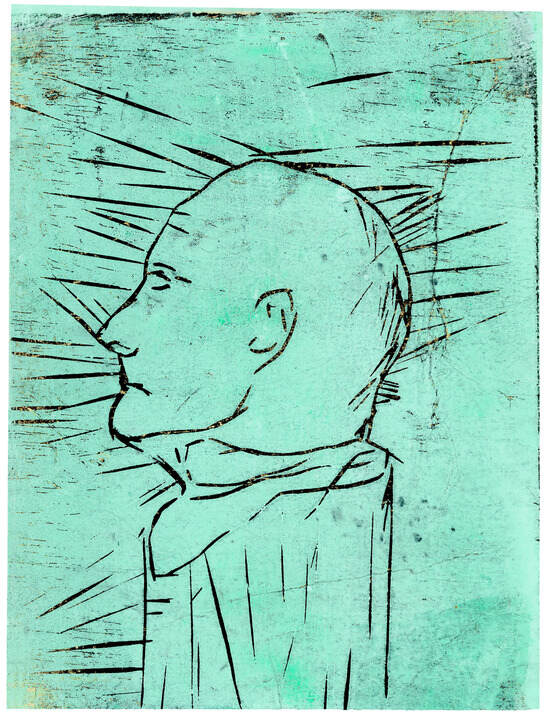

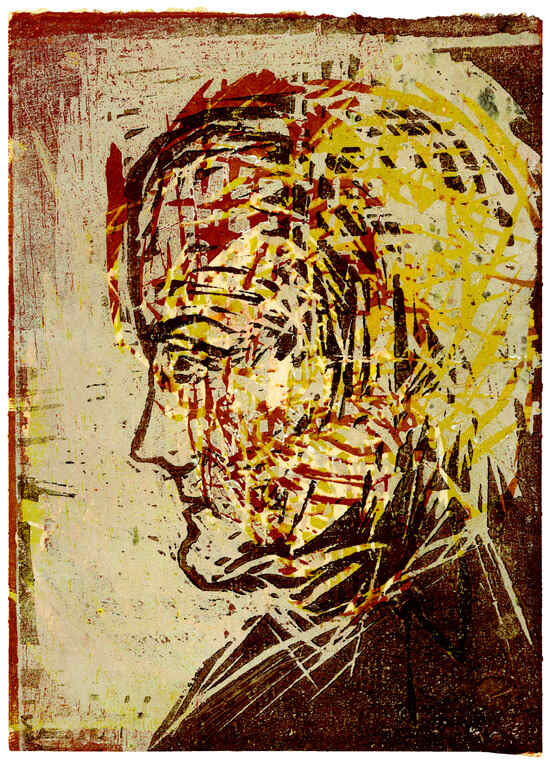

As if erected on a stele, upright, in an extremely stiff posture, Neubert’s wax relief appears in a wide variety of color variations, including a head surrounded by blue rays (Figure 6, see Figure 3), which increasingly disappears into deep black, until nearly unrecognizable (Figure 7, see Figure 3). Initially, Brandes thought it was Hölderlin’s death mask. Although Neubert clearly models the coat collar and neckerchief in his bust, Brandes places the head on a grave pedestal.

Figure 6.

Brandes: FH. Woodcut, 2009. (To Figure 3).

Figure 7.

Brandes: FH. Woodcut, 2009. (To Figure 3).

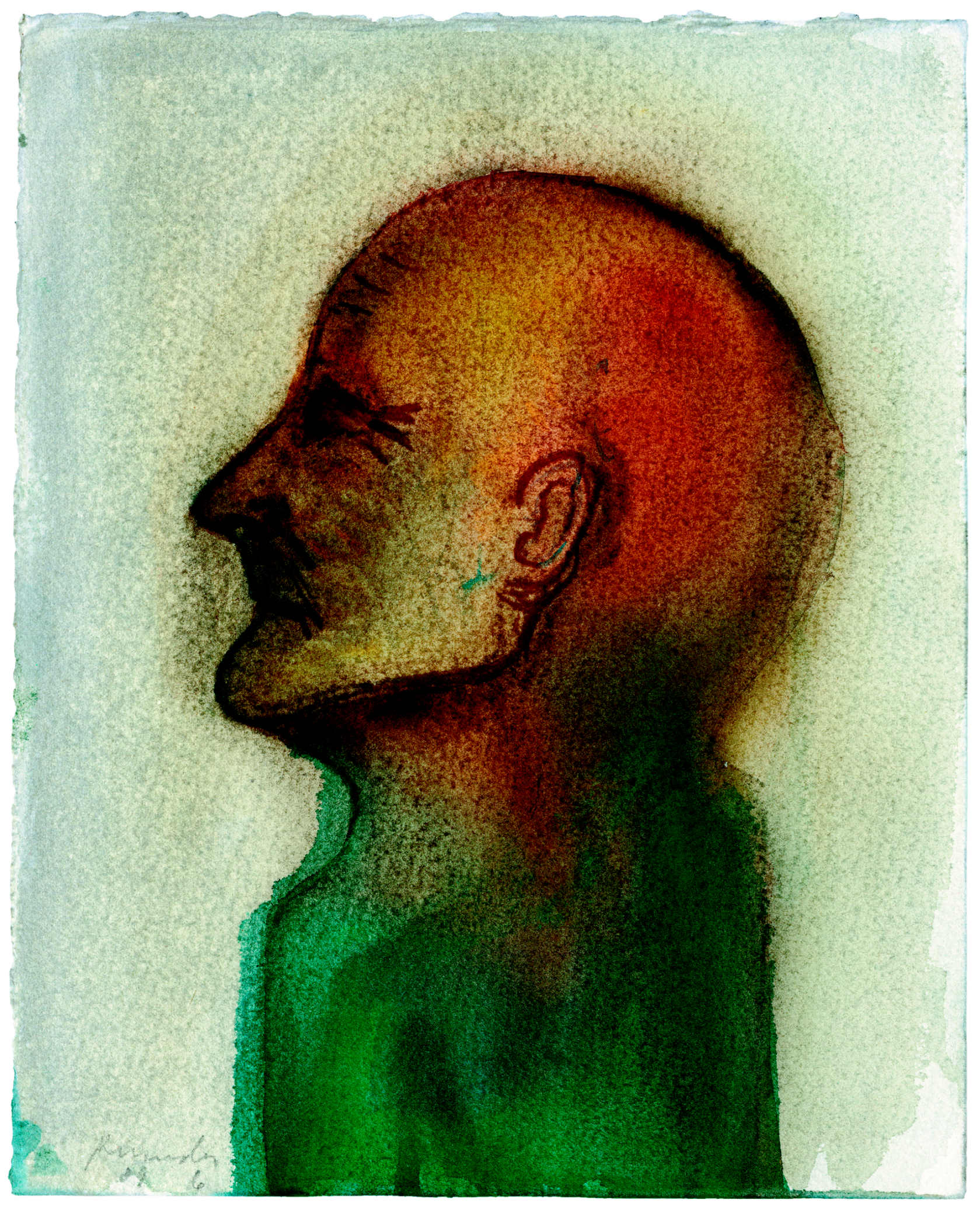

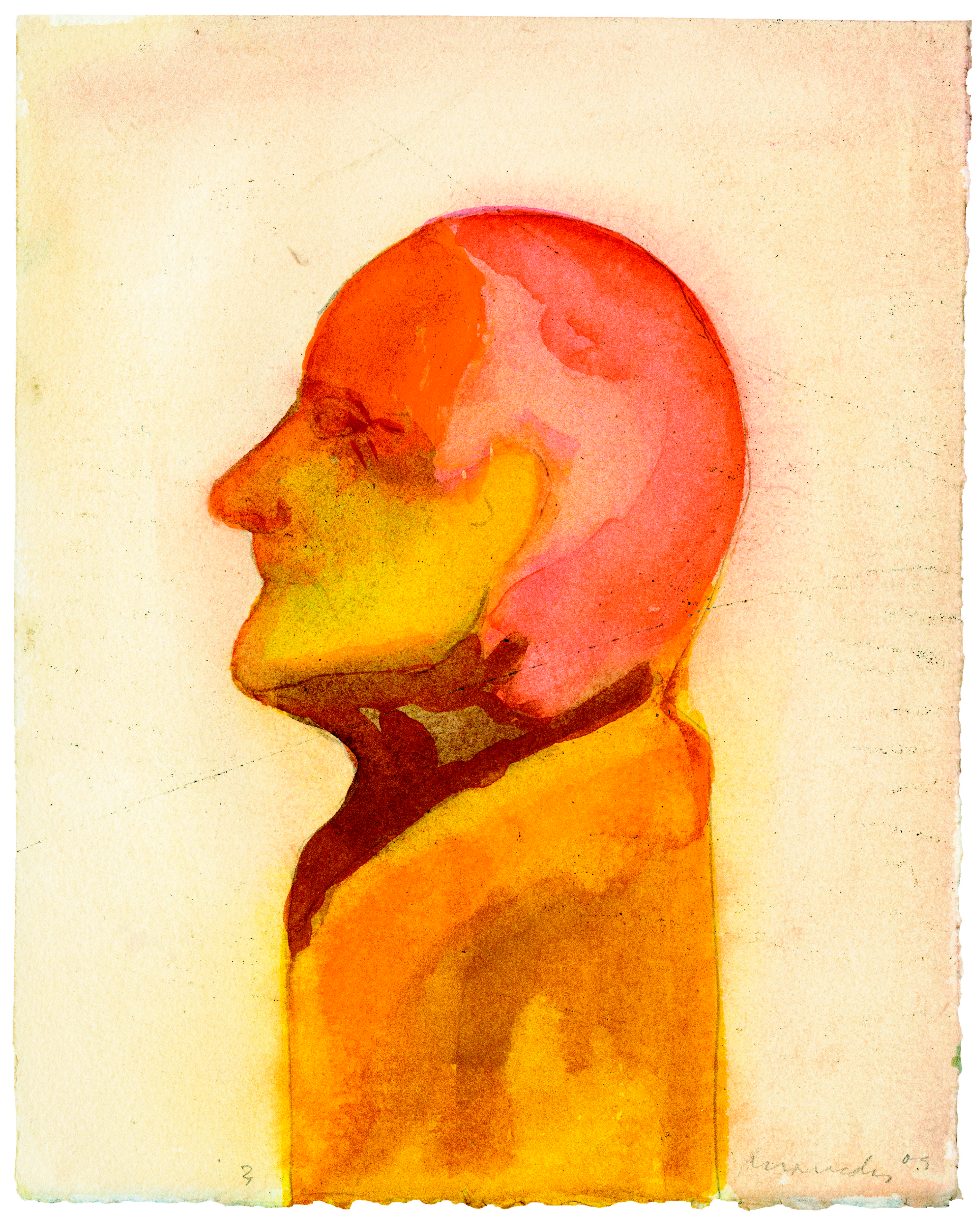

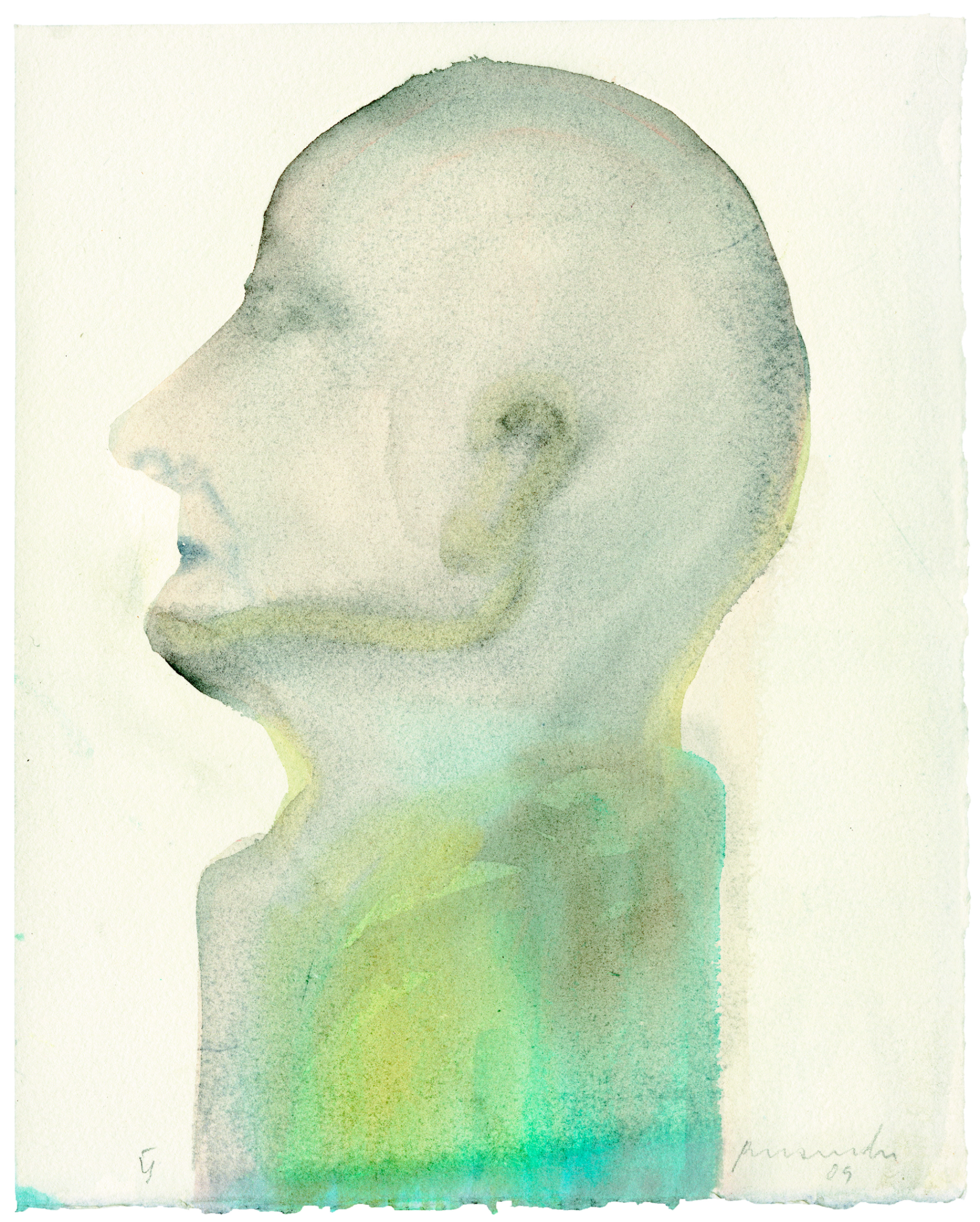

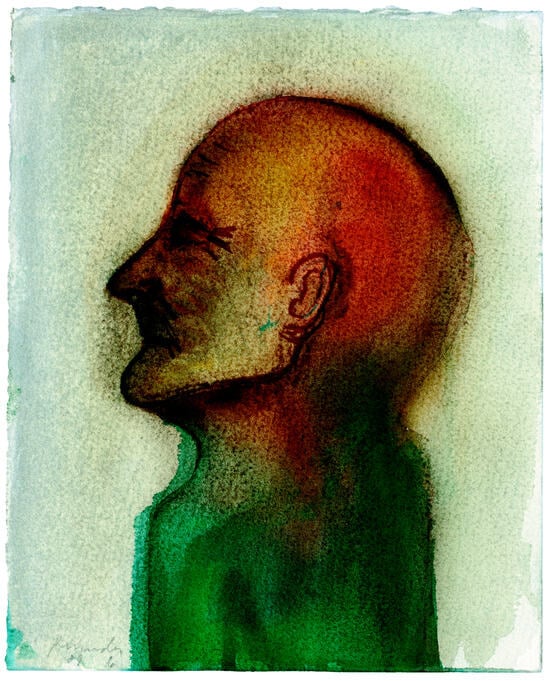

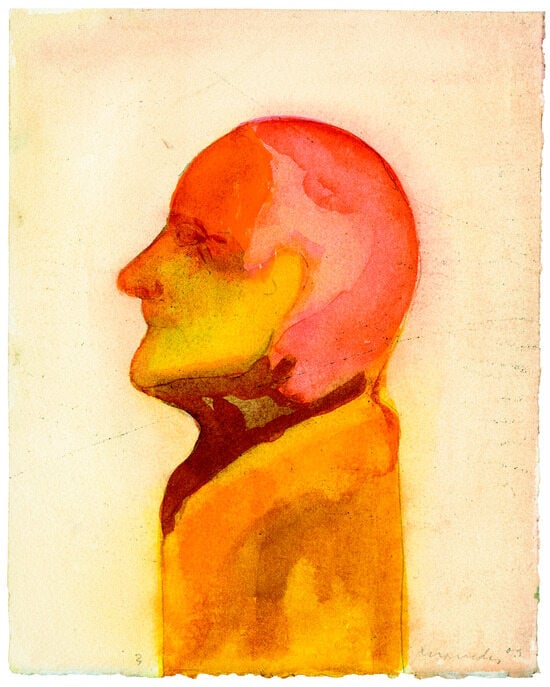

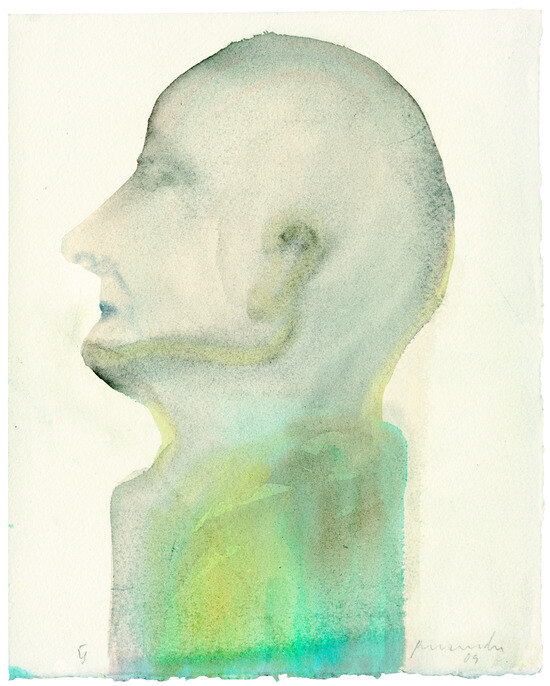

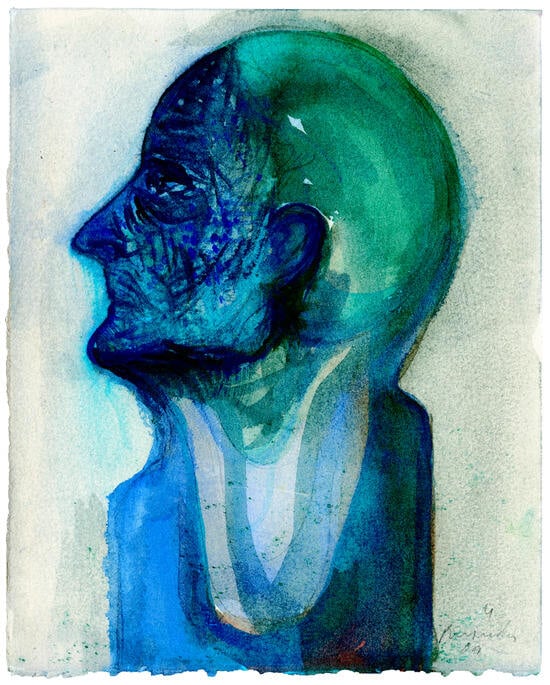

The series of watercolors for this portrait, however, is quite different. They shine across the entire color spectrum: from darker tones to bright, vibrant reds and yellows, to one in the finest shades of light gray and light blue, as if seen with blurred vision. Then we find a blue and gray palette, the face furrowed by nerves and veins, the prominent chin and lips sharply defined, the eye clear. In his watercolors, Brandes uses washes, in which color gradients, blending effects, and color transitions are created in the wet colors, and then overlays them with a wet-on-dry technique. This explains the subtle transparency, the translucence of each applied layer of color. (Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11, see Figure 3).

Figure 8.

Brandes: FH. Watercolor, 2009. (To Figure 3).

Figure 9.

Brandes: FH. Watercolor, 2009. (To Figure 3).

Figure 10.

Brandes: FH. Watercolor, 2009. (To Figure 3).

Figure 11.

Brandes: FH. Watercolor, 2009. (To Figure 3).

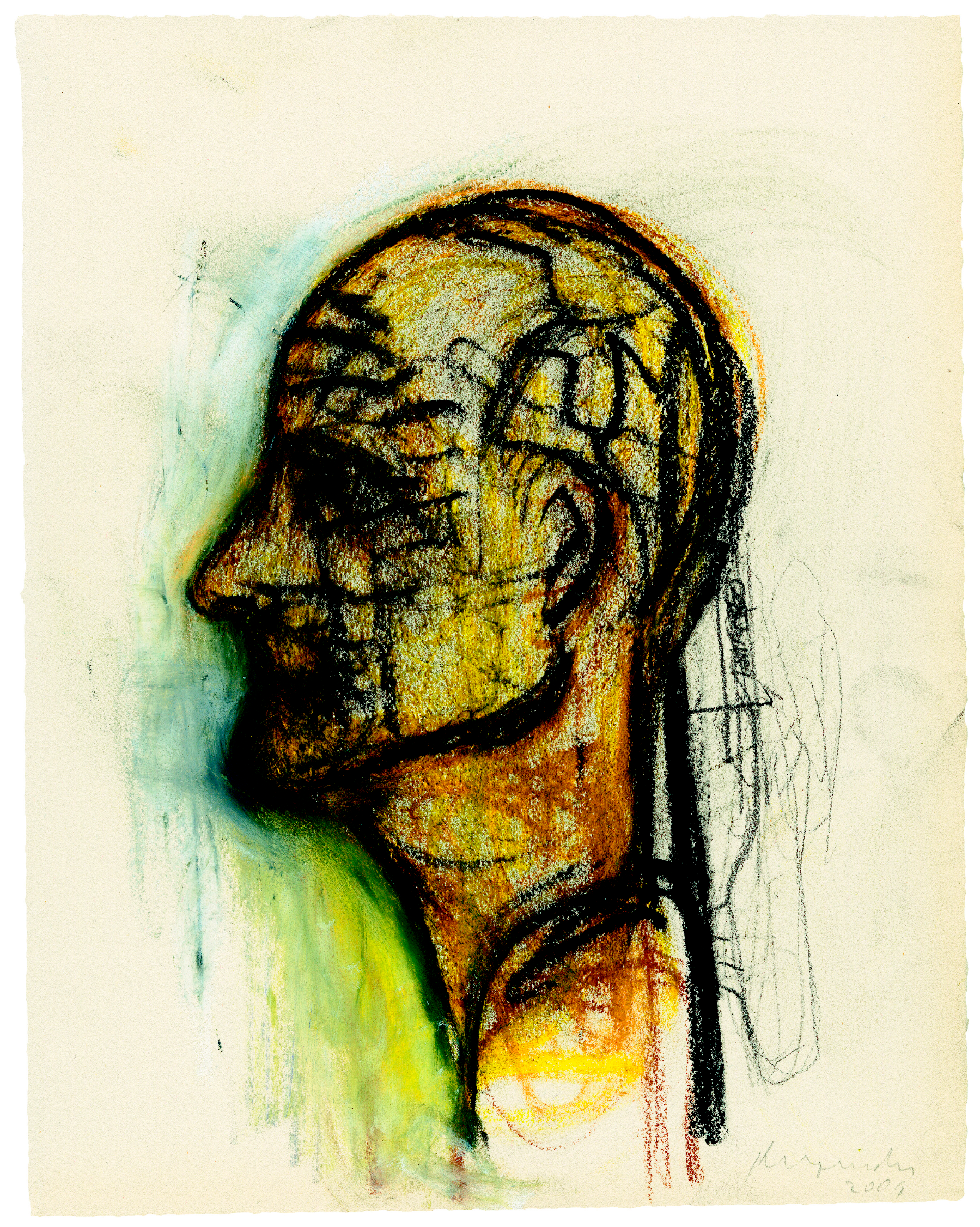

But other materials, such as charcoal, pencil, and colored crayon, also come into play. (Figure 12, see Figure 3).

Figure 12.

Brandes: FH. Watercolor, 2009. (To Figure 3).

Brandes follows the four portraits, all shown in profile; only the fourth, by Louise Keller, is laterally inverted (Figure 13, see Figure 4) All are carried by an inward gaze, and are characterized by sharply contoured outlines.

Figure 13.

Brandes: FH. Woodcut, 2009. (To Figure 4).

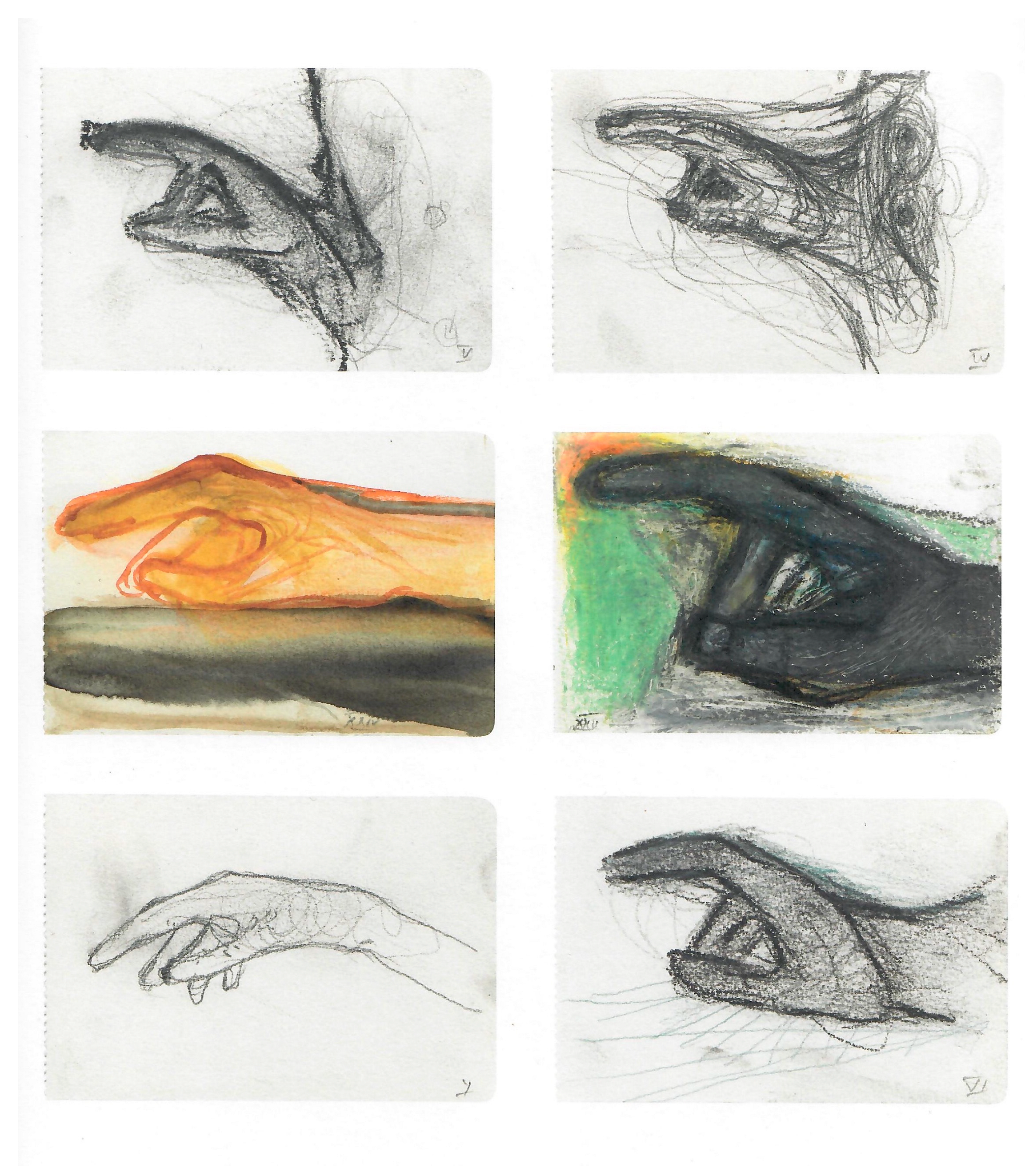

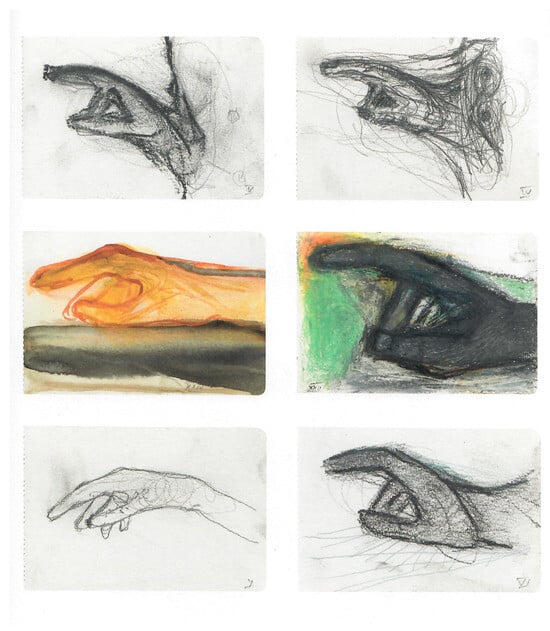

The charcoal drawing by Johann Georg Schreiner from 1825/1826 (see Figure 2) gave rise to the longest series of experiments. (The perforations from the sketchbook can be seen on the many sheets: Figure 14, 6 Studies).

Figure 14.

Brandes: FH. Hand (6 Studies). Pencil, charcoal, colored chalk, ink and watercolor. (To Figure 2).

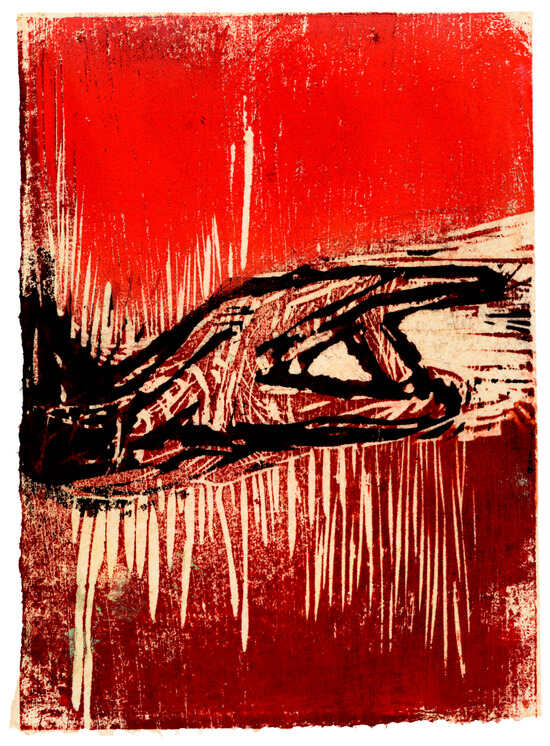

Brandes isolates one element: the hand, with tense fingers pointing at something we cannot see. With this gesture, a space is opened up (Figure 15, see Figure 2).

Figure 15.

Brandes: FH. Hand. Woodcut, 2009. (To Figure 2).

The color scheme of this black-outlined hand, whose background forms a large triangle that, like a flame, continues the pointing function, is a burning fiery red. This is reminiscent of Zimmer’s description of Hölderlin turning “ziegelroth” (StA 7.3, p. 134; brick red). The burning red is also significant in Munch’s works. But, in Munch’s case, it is an expression of his own state of mind. Brandes, on the other hand, seeks to fathom the expression of the other.

Brandes cut six variants, let us call them “Annäherungen” (approaches), with very subtle, barely noticeable differences. Here, he also includes the poet’s jacket, which reaches down to the hips, including the folds—as drawn in the original Hölderlin portrait.

Brandes comments:

Charakteristisch ist die Haltung des Körpers, die energische Kraft des Kopfes und nicht zuletzt das “Hineingreifen” der rätselhaften Hand in den Raum. Dieser zeigende Finger hat mich fasziniert. Eine Waffe, ein Degen, ein Taktstock, ein Schlüssel, ein Ruf, ein Ausrufezeichen, eine Aussage, ein Versuch, ein Nagel, die Form eines Schattenrisses, eine Alternative zu nichts, eine Frage.—Der Finger, der nie einen Ehering trug, der Finger, der am Schreiben von Gedichten beteiligt war, der Finger, der das Fenster im Turmzimmer berührte, dort wo eine klare Fensterscheibe—als wäre der Augapfel Hölderlins von einer dünnen Haut überzogen—eine “Wand” zwischen der (Innen-)Welt und der Außenwelt des Dichters bildete.

In meinem vorläufig letzten Holzschnittentwurf taucht Hölderlin seine Hand in einen mohnfarbenen Fluss. “Gedächtnis und Mohn”52. Die Farbe des Blutes ist zugleich die Farbe des Lebens—sie glüht wie das Feuer. Wenn draußen vor dem Fenster der Tag beginnt, ist der Himmel rot. Und wenn draußen die Nacht vor das Fenster kommt, ist der Himmel rot. Die Gedichte sind zwischen die äußersten Punkte gespannt, und in ihrem zyklischen Verlauf wird der Dichter—einsam—mit sich selbst vereint. Figure 16. Brandes: FH. Memory and poppies. Woodcut, 2009. (To Figure 2).

Figure 16. Brandes: FH. Memory and poppies. Woodcut, 2009. (To Figure 2).

The posture of the body, the energetic strength of the head and, last but not least, the “grasping” into space of the enigmatic hand are characteristic. The pointing finger fascinated me. A weapon, a sword, a baton, a key, a call, an exclamation mark, a statement, an attempt, a nail, the shape of a silhouette, an alternative to nothing, a question.—The finger that never wore a wedding ring, the finger that was involved in writing poems, the finger that touched the window in the tower room, where a clear window pane—as if Hölderlin’s eyeball were covered by a thin skin—formed a “wall” between the (inner) world and the outside world of the poet.

In my last woodcut design for the time being, Hölderlin dips his hand into a poppy-colored river. “Gedächtnis und Mohn” (Memory and Poppy). The color of blood is also the color of life—it glows like fire. When day begins outside the window, the sky is red. And when night comes outside the window, the sky is red. The poems are stretched between the outermost points, and in their cyclical course the poet—alone—is united with himself.

Hölderlin’s latest verses read:

Nun versteh’ ich den Menschen erst, da ich fern von ihm und in der Einsamkeit lebe.(StA 2.1, p. 340)

Now I understand man for the first time, since I live far from him and in solitude.

Fascinated by the four portraits of Friedrich Hölderlin in his later years, which have survived from his time in the tower, the artist Peter Brandes created a remarkable body of work, expressed primarily in woodcuts. In his “approaches,” he did not seek to symbolize his own state of mind, but rather engaged with the mind of the other, the one he had yet to discover.

A development can be seen in these works: while the depictions, starting with the portraits of Schreiner and Lohbauer from 1823 and Louise Keller from 1842, remain close to the model, the artist abstracts from the details of facial features in the portrait by Schreiner and Lohbauer, created two years later, which was so important to him. The energetic figure, shown faceless, is rendered merely in its outlines, occasionally traversed by the folds of the jacket. The contoured hand with the pointing finger in translucent red becomes a sign gesturing outward.

The latest tower poems have been called “Fenstergedichte” (window poems). Brandes imagined the poet standing at the window in his tower room. The window forms the boundary, separating the outside from the inside. It affords the view and the perspective but, at the same time, it is a connection between the two spaces, and ultimately, it is also a mirror for the inner view: separation—connection—reflection. Brandes’ works approach the poet’s inner view. But he has become lost to the world, is “ferne, nicht mehr dabei”53 (distant, no longer present).

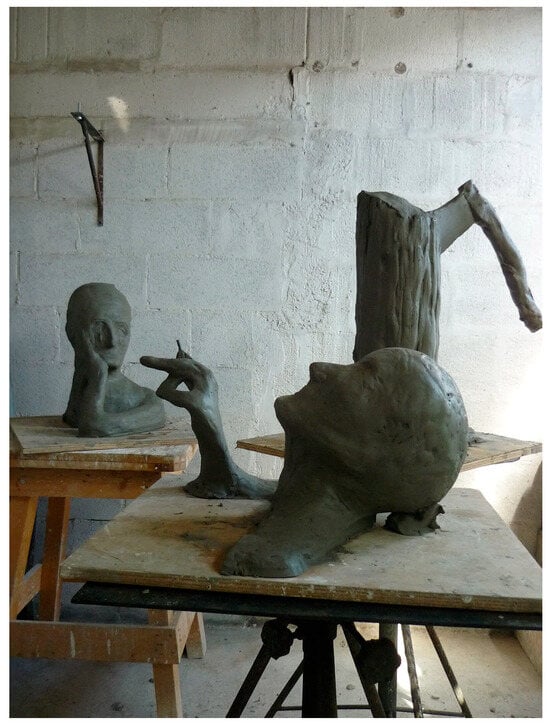

Brandes’ bronze sculpture (2013), the aforementioned trilogy, is his most recent exploration of Hölderlin. From the portraits described above, he selected two elements: the hand with the outstretched index finger from the drawing by Schreiner (from 1825/26) and the head from Neubert’s wax relief (from 1840), which he now places concretely on a pedestal. Leaning sharply backward, his sculpture, says Brandes, stares “in den Himmel—ein für uns nicht fassbares Universum, wohin er mit seinem Finger auf die Rätsel weist, die in ihm verborgen sind. Hölderlin liegt ausgestreckt und scheint mit dem Neckar zu fließen”54 (into the sky—a universe incomprehensible to us, where he points with his finger to the riddles hidden within it. Hölderlin lies stretched out and seems to flow with the Neckar River; Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Brandes: The Sculpture Hölderlin—Celan—Heidegger. Clay, 2013.

Where in Tübingen should this sculpture be located? We know that the Hölderlin Tower is a special place: It forms a triangular relationship within a very small space: Stift—Burse—Turm (seminary—bursa—tower). Studies in the Stift, treatment in the Burse at the Autenrieth University Clinic, half of the poet’s life in the tower.55 Peter Härtling identified another such a magical triangle, as he called it, in Nürtingen: Latin school—town church—residence. And it is always the place by the water: a small stronghold on the river:

Will einer wohnen,So sei es an Treppen,Und wo ein Häuslein hinabhängtAm Wasser halte dich auf.Und was du hast, istAthem zu hohlen.56

If someone wishes to dwell,Let it be on stepsAnd where a small house hangs downNear water, there spend your days.And what is yours

Is to draw breath.(Hölderlin 2004, p. 653)

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Image Credits

- 1 Friedrich Hölderlin. Pencil drawing by Johann Georg Schreiner and Rudolf Lohbauer, July 27, 1823. Written in Mörike’s hand on the drawing is the following: “Von Schreiner und Rudolph in Eile gezeichnet den 27sten Juli 23.” (Drawn in haste by Schreiner and Rudolph on July 27, 1823.) H. 22.4 × W. 21.0 cm. Original: Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach a.N., Inv.Nr. B 53.79.

- 2 Friedrich Hölderlin. Black chalk over pencil on vergé paper by Johann Georg Schreiner 1825/1826. H. 8.2 × W. 8.6 cm. Original: Freies Deutsches Hochstift/Frankfurter Goethe-Museum, Inv.Nr. III-03630.

- 3 Friedrich Hölderlin. Wax relief by W. Neubert, around 1840. H. 12 × W. 6.5 cm. Original: Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach a.N., Inv.Nr. 1299.

- 4 Friedrich Hölderlin. Pencil drawing by Louise Keller, 1842. H. 22.1 × W. 15.8 cm. Original: Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach a.N., Inv.Nr. B 54.10.

- 5 Peter Brandes: FH (Friedrich Hölderlin). Woodcut, 2009. (To Figure 1) H. 27.7 × W. 20 cm. Original: Courtesy Galerie Moderne, Silkeborg.

- 6 Peter Brandes: FH. Woodcut, 2009. (To Figure 3) H. 27.7 × W. 20 cm. Original: Courtesy Galerie Moderne, Silkeborg.

- 7 Peter Brandes: FH. Woodcut, 2009. (To Figure 3) H. 27.7 × W. 20 cm. Original: Courtesy Galerie Moderne, Silkeborg.

- 8 Peter Brandes: FH. Watercolor, 2009. (To Figure 3) H. 25.5 × W. 20 cm. Original: Courtesy Galerie Moderne, Silkeborg.

- 9 Peter Brandes: FH. Watercolor, 2009. (To Figure 3) H. 25.5 × W. 20 cm. Original: Courtesy Galerie Moderne, Silkeborg.

- 10 Peter Brandes: FH. Watercolor, 2009. (To Figure 3) H. 25.5 × W. 20 cm. Original: Courtesy Galerie Moderne, Silkeborg.

- 11 Peter Brandes: FH. Watercolor, 2009. (To Figure 3) H. 25.5 × W. 20 cm. Original: Courtesy Galerie Moderne, Silkeborg.

- 12 Peter Brandes: FH. Charcoal, pencil and colored chalk, 2009. (To Figure 3) H. 28 × W. 23 cm. Original: Courtesy Galerie Moderne, Silkeborg.

- 13 Peter Brandes: FH. Woodcut, 2009. (To Figure 4) H. 27.7 × W. 20 cm. Original: Courtesy Galerie Moderne, Silkeborg.

- 14 Peter Brandes: FH. Hand (6 Studies). Pencil, charcoal, colored chalk, ink and watercolor. (To Figure 2) H. 8.3 × W. 13.3 cm, 2009. Original: Peter Brandes’ Notizbuch (Peter Brandes’ notebook).

- 15 Peter Brandes: FH. Hand. Woodcut, 2009. (To Figure 2) H. 27.7 × W. 20 cm. Original: Courtesy Galerie Moderne, Silkeborg.

- 16 Peter Brandes: FH. Gedächtnis und Mohn (Memory and poppies). Woodcut, 2009. (To Figure 2) H. 27.7 × W. 20 cm. Original: Courtesy Galerie Moderne, Silkeborg.

- 17 Peter Brandes: The Sculpture Hölderlin—Celan—Heidegger. Clay, 2013. In Brandes’ studio, the sculpture was made in clay, after which he cast it in bronze. In front: Hölderlin and the hand; on the left: Celan; on the right: Heidegger (as a symbol: tree stump and hewn axe). Original: Hölderlinturm Tübingen. Inauguration, 4 May 2025. The Trilogy will be permanently installed in the cloister of the Evangelisches Stift in Tübingen.

- For their permission to reproduce their images we thank the Deutsches Literaturarchiv, Marbach a.N. (Figure 1 and Figure 4), the Freies Deutsches Hochstift/Frankfurter Goethemuseum (Figure 3), the Deutsches Literaturarchiv, Cotta-Archiv, Marbach a.N. (Figure 4) and Maja Lisa Engelhardt for permission to print the artistic works by Peter Brandes (Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17).

Notes

| 1 | See the bibliographie in Rocca (2019, pp. 261–69). |

| 2 | (Rocca 2019, p. 10), note 1: “I used the concept of Kulturwanderung in connection with Peter Brandes’ oeuvre for the first time in the laudatio I delivered at the presentation to Peter Brandes of the Friedrich Hölderlin Preis in Tübingen on November 6, 2013. Later, Kulturwanderer was used in the title of Brandes’ Festschrift (Kulturvandrer: Festskrift til Peter Brandes i anledning af halvfjerdsårsdagen [Kulturwanderer: A Festschrift for Peter Brandes on the Occasion of His Seventieth Birthday], ed. Niels Jørgen Cappelørn, Johannes Riis, and Ettore Rocca (Cappelørn et al. 2014)). Most recently, the concept has been used as the subtitle of the 2019 exhibition at Johannes Larsen Museum.” |

| 3 | Baltzer (2008), title page with nine woodcuts by Peter Brandes. |

| 4 | He displayed the wooden sticks he worked with in a display case and explained how he selects his materials at the opening of his exhibition in the Hölderlin Tower in Tübingen/Germany in 2009. |

| 5 | Letter from Peter Brandes, September 9, 2015. In private ownership. |

| 6 | See also Rocca (2019, pp. 240–42). |

| 7 | See also Rocca (2019, pp. 240–42). |

| 8 | There is no family relationship between the Copenhagen Brandes family: Georg (1842–1927) and Edvard (1847–1931). |

| 9 | Rocca (2019, p. 16). |

| 10 | Rocca (2019, p. 16). |

| 11 | Brandes quoted in Baltzer (2008, p. 8). |

| 12 | Rocca has chosen the bronze sculpture, created according to etchings in 2018–2019 as the title image of his book. |

| 13 | From conversations with Peter Brandes; he loved this story and retold it many times. |

| 14 | Brandes quoted in Baltzer (2008, p. 9). |

| 15 | Peter Brandes thought that his grandfather was murdered in Auschwitz; he first learned in 2019, as confirmed and documented by Serge Klarsfeld (Rocca 2019, p. 21, note 27), that it happened in the camp of Sobibór. 250,000 Jews were murdered there. |

| 16 | Brandes quoted in Baltzer (2008, p. 9). |

| 17 | Brandes quoted in Baltzer (2008, p. 8). |

| 18 | Peter Brandes’ wife, Maja Lisa Engelhardt, provided me with names and dates; mail from August 31, 2025. |

| 19 | Baltzer gave the spelling of her name as “Höfer” (Baltzer 2008, p. 9), but Peter Brandes spelled it as “Hoffer” (Rocca 2019, p. 33). |

| 20 | Baltzer (2008, p. 8). See also Rocca (2019, p. 33). |

| 21 | Report from Johann Georg Fischer in MA 3, p. 672. This was the miniature edition of Hölderlin’s poems, published by Cotta in November 1842. |

| 22 | C. T. Schwabs Tagebuch, February 25, 1841 (MA 3, p. 670): “Ich war am 12. Febr. Nachmittags einige Minuten bei Hölderlin, um ihm ein Exemplar seiner Gedichte, da ihm das seinige, in welchem einige angebundene Blätter mit neueren Gedichten beschrieben waren, gestohlen worden ist, zum Geschenk zu bringen.” (On the afternoon of February 12, I visited Hölderlin for a few minutes to give him a copy of his poems as a gift, since his own copy, which contained several attached sheets with newer poems, had been stolen). |

| 23 | Reproductions of the five early portraits are found in (Beck and Raabe 1970): 1786, p. 130 (Figure 20); 1788, p. 141 (Figure 34); 1790, p. 163 (Figure 61), 1792, frontispiece; 1797, p. 235 (Figure 146). |

| 24 | Letter from Gustav Schoder to Immanuel Hoch, October 3, 1806 (StA 8, p. 17 [no. 355a]). The letter was discovered by Uwe Jens Wandel (Wandel 1977). |

| 25 | Schwab (1846, p. 314; FHA 9, p. 460). |

| 26 | Zimmer to Oberamtspfleger Burk in Nürtingen, 16 April 1828 (StA 7.3, p. 103 [no. 507]). |

| 27 | Zimmer to Hölderlin’s mother, 19 April 1812 (MA 3, p. 649). |

| 28 | Zimmer to an unknown person, December 22, 1835 (StA 7.3, p. 134 [no. 528]. |

| 29 | Wilhelm Waiblinger, Aus den Tagebüchern, August 10, 1822 (StA 7.3, p. 7). |

| 30 | Wilhelm Waiblinger, Aus den Tagebüchern, August 9, 1822 (StA 7.3, p. 7). |

| 31 | Wilhelm Waiblinger, Aus den Tagebüchern, June 8, 1823 (StA 7.3, p. 10). |

| 32 | Wilhelm Waiblinger, Friedrich Hölderlins Leben, Dichtung und Wahnsinn (StA 7.3, p. 66). |

| 33 | Wilhelm Waiblinger, Friedrich Hölderlins Leben, Dichtung und Wahnsinn (StA 7.3, p. 66). |

| 34 | C. T. Schwabs Tagebuch, January 21, 1841 (MA 3, p. 669). |

| 35 | Mörike quoted in Beck and Raabe (1970, p. 415, on Figure 248 (p. 319)). |

| 36 | Mörike quoted in Beck and Raabe (1970, p. 415, on Figure 248 (p. 319)). |

| 37 | Mörike quoted in Beck and Raabe (1970, p. 415, on Figure 248 (p. 319)). |

| 38 | Zimmer to an unknown person, December 22, 1835 (StA 7.3, p. 134 [no. 528]). See also letter from Zimmer to Burk, January 21, 1832 (StA 7.3, p. 124 [no. 522]). The first edition of the letters from Zimmer to Burk appeared in (Wittkop 1993): November 6, 1833, p. 185 (no. 237), and July 18, 1834, p. 189 (no. 250). |

| 39 | Mörike quoted in (Beck and Raabe 1970), p. 417. |

| 40 | Mörike quoted in (Beck and Raabe 1970), p. 417. |

| 41 | Zimmer to Hölderlin’s sister, July 19, 1828 (StA 7.3, p. 105 [no. 508]). |

| 42 | C. T. Schwabs Tagebuch, January 14, 1841 (MA 3, p. 666). |

| 43 | C. T. Schwabs Tagebuch, January 21, 1841 (MA 3, p. 669). |

| 44 | Waiblinger, Friedrich Hölderlins Leben (StA 7.3, pp. 61–62). |

| 45 | Mörike to Kurz, June 26, 1838 (StA 7.3, p. 170 [no. 536e]). |

| 46 | Sophie Schwab to Kerner (StA 7.3, p. 211). See Oelmann (1996, p. 209); Oelmann (2020, pp. 409–15). |

| 47 | Waiblinger, Friedrich Hölderlins Leben (StA 7.3, p. 73). |

| 48 | Philipp und Marie Nathusius bei Hölderlin (StA 7.3, p. 253), p. 253. |

| 49 | The term “Bildgespräch” (in the singular) is used by the American poet of German origin Margot Scharpenberg (1924–2020). In her poems, published in German, she responds to works of visual art. Her creations are the poems. Brandes’ starting point, on the other hand, is image and text, to which he responds with his works of art. He himself gives a definition of his work which could “be understood through plastic presentations, and not by words.” (Brandes quoted in Rocca 2019, p. 16 and note 19). |

| 50 | Walz (1985); see Lawitschka (2020, p. 540). |

| 51 | (StA 2.1, p. 221), see also Homburger Folioheft, p. 46. |

| 52 | The allusion to Celan’s collection of poems, Mohn und Gedächtnis is obvious. In the poem Corona we read: “wir lieben einander wie Mohn und Gedächtnis” (Celan [1952] 2000, p. 33; we love each other like poppy and memory). The poppy is considered to be a symbolic remembrance and commemoration of the victims of the Holocaust. Brandes’ essay in (Brandes 2009, pp. 70–71) is entitled “Gedächtnis und Mohn”. |

| 53 | From Hölderlin’s poem Ganymed (StA 2.1, p. 68). |

| 54 | Letter from Peter Brandes, September 9, 2015. In private ownership. |

| 55 | Brandes’ “Trilogie” was on display in the Hölderlin Tower from May 4–July 6, 2025. See the article “Heidegger als Stumpf mit Axt”, discussion of the work and the lecture I held at the opening of the exhibit on 4 May 2025, in the Schwäbisches Tagblatt (Siebert 2025, p. 21). Since I wrote this article, it has been decided that the Trilogy will be permanently installed in the cloister of the Evangelisches Stift in Tübingen. |

| 56 | From Hölderlin’s poem Der Adler (StA 2.1, p. 230, vv. 27–32). |

References

Primary Source

FHA: Hölderlin, Friedrich. 1975–2008. Sämtliche Werke. Frankfurter Ausgabe. Edited by D. E. Sattler. 20 volumes. Frankfurt a.M./Basel: Stroemfeld, Roter Stern.Hölderlin, Friedrich. 1826. Edited by Ludwig Uhland and Gustav Schwab. Stuttgart/Tübingen: Cotta.Hölderlin, Friedrich. 2004. Poems and Fragments. Translated by Michael Hamburger. London: Anvil House Poetry.Homburger Folioheft: Hölderlin, Friedrich. 1986. Homburger Folioheft. Faksimile-Edition, Supplement III. Edited by D. E. Sattler and Emery George, Frankfurt a.M./Basel: Stroemfeld. Roter Stern.MA: Hölderlin, Friedrich. 1992–1993. Sämtliche Werke und Briefe. Edited by Michael Knaupp. 3 volumes. München/Wien: Hanser.Schwab, Christoph Theodor (Ed.). 1846. Hölderlin’s Leben. In Friedrich Hölderlin’s sämmtliche Werke. 2 volumes, Stuttgart/Tübingen: Cotta.StA: Hölderlin, Friedrich. 1943–1985. Sämtliche Werke. Große Stuttgarter Ausgabe. Edited by Friedrich Beißner, Adolf Beck and Ute Oelmann. 8 in 15 volumes. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.Secondary Source

- Baltzer, Burkhard. 2008. Der Fuß über dem Wasser. Die Geschichte eines Künstlers, der die Geschichte des Jahrhunderts mit sich trägt. Kunst + Kultur. Kulturpolitische Zeitschrift 15: 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, Adolf, and Paul Raabe, eds. 1970. Hölderlin. Eine Chronik in Text und Bild. Frankfurt am Main: Insel. [Google Scholar]

- Brandes, Peter. 2009. Hölderlins Turmgedichte. Bildgespräche, Arbeiten und Skizzen. Katalog zur Ausstellung im Museum Hölderlinturm vom 19. Juli 2009 bis 31. Mai 2010. Tübingen and Berlin: Ernst Wasmuth. [Google Scholar]

- Büchner, Georg. 1969. Dantons Tod. In Werke und Briefe. Dramen, Prosa, Briefe, Dokumente. Gesamtausgabe, 4th ed. München: dtv. First published 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Cappelørn, Niels Jørgen, Johannes Riis, and Ettore Rocca, eds. 2014. Kulturwanderer: A Festschrift for Peter Brandes on the Occasion of His Seventieth Birthday. Copenhagen: Gyldendal. [Google Scholar]

- Celan, Paul. 2000. Mohn und Gedächtnis. Stuttgart and München: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt. First published 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Fichtner, Gerhard. 1980. Psychiatrie zur Zeit Hölderlins. Ausstellungskatalog der Universität Tübingen. Tübingen: Universitätsbibliothek. [Google Scholar]

- Franz, Michael. 2024. Verbringung Hölderlins ins Universitätsklinikum Tübingen. In Hölderlin Texturen: “offen die Fenster des Himmels”—Nürtingen, Homburg 1802–1806. Lebensstationen und Werke. Edited by Michael Franz, Priscilla Hayden-Roy and Valérie Lawitschka. Tübingen: Hölderlin-Gesellschaft, vol. 6/1, pp. 270–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lawitschka, Valérie. 2009. Hölderlin—Holz—Schnitt. In Hölderlins Turmgedichte: Bildgespräche, Arbeiten und Skizzen. Edited by Peter Brandes. Tübingen/Berlin: Wasmuth, pp. 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lawitschka, Valérie. 2020. Nachwirkungen in der bildenden Kunst. In Hölderlin-Handbuch. Leben—Werk—Wirkung. Edited by Johann Kreuzer. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, pp. 535–47. [Google Scholar]

- Oelmann, Ute. 1996. Fenstergedichte (“Der Frühling” und “Der Herbst”). In Interpretationen. Gedichte von Friedrich Hölderlin. Edited by Gerhard Kurz. Stuttgart: Reclam, pp. 200–12. [Google Scholar]

- Oelmann, Ute. 2020. Späteste Gedichte. In Hölderlin-Handbuch. Leben—Werk—Wirkung. Edited by Johann Kreuzer. Berlin: J. B. Metzler, pp. 409–15. [Google Scholar]

- Oestersandfort, Christian. 2006. Immanente Poetik und poetische Diätetik in Hölderlins Turmdichtung. Tübingen: Niemeyer. [Google Scholar]

- Ring, Max. 1859. Hölderlin. In Die Gartenlaube: Illustrirtes Familienblatt. Berlin: Scherl, pp. 164–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rocca, Ettore. 2019. Peter Brandes. Meridian of Art. Aarhus: Univeristy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, Christoph Theodor, ed. 1846. Hölderlin’s Leben. In Friedrich Hölderlin’s sämmtliche Werke. 2 vols. Stuttgart/Tübingen: Cotta, pp. 459–72. [Google Scholar]

- Siebert, Moritz. 2025. Heidegger als Stumpf mit Axt. Schwäbisches Tagblatt, May 6, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Walz, Erich. 1985. Kolomb (nach Hölderlin). Holzschnitt-Folge und Textbeilage. Hausen am Tann: self-published. [Google Scholar]

- Wandel, Uwe Jens. 1977. Der geheime Otaheiti-Bund. Schwäbisches Tagblatt, October 22. [Google Scholar]

- Wittkop, Gregor, ed. 1993. Hölderlin. In Der Pflegsohn. Texte und Dokumente 1806–1843 mit den neu entdeckten Nürtinger Pflegschaftsakten. Stuttgart and Weimar: J. B. Metzler. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).