The Unmade City: Subjectivity, Buffalo and the Sad Fate of Studio Arena Theatre

Abstract

:- Yet once more I dream. Once more a voice says:

- Build a house for the sun, with a winding stair

- for the wandering light to go up and rest

- before labour.

- Cold, cold are the winds from the unmade world.

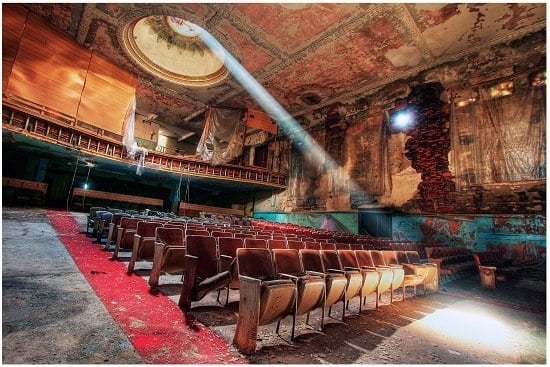

Theatre spaces are unique because they are intended for unique forms of human interaction. When they are abandoned, they are stripped in a way that factories and offices are not. Theatrical performances are ephemeral. But theatre spaces are built with permanence in mind. They wear their past on their sleeve. What was is almost more apparent than what is.Timothy Neesam, photographer [2].

1. Introduction

Truth is…a matter of conviction first and foremost, and every subject demonstrates “what a conviction is capable of, here, now, and forever”. The word truth (vérité), as Badiou uses it, connotes something close to the English expressions “to be true to something” or “to be faithful to something”. What Badiou calls subjectivization essentially describes the experience of identification with a cause, or better, the active experience of conversion or commitment to a cause—a cause with which one can identify oneself without reserve. “Either you participate, declare the founding event, and draw the consequences, or you remain outside it,” he writes. “This distinction without intermediary or mediation is entirely subjective”. The identity of the subject rests entirely, unconditionally, on this commitment…It is only in such rare moments of pure engagement, Badiou suggests, that we become all that we can be, that is, that we are carried beyond our normal limits, beyond the range of predictable response…Truth, subject, and event are all aspects of a single process: a truth comes into being through the subjects who proclaim it and, in doing so, constitute themselves as subjects in their fidelity to the event.([5], p. xxvi)

To participate in the affirmation of a truth involves, in any given world, active incorporation into the subject body or corps of that affirmation. Such incorporation provides Badiou with his definitions of a true worldly life…”To live is to participate, point by point, in the organisation of a new body in line with what is required by a faithful subjective formalism”.([10], p. 108)

2. Buffalo and Studio Arena Theatre Narrative

3. Regional Theatre

The moment a group organized to promote the Little Theatre ideal…permits its judgement in the matter of plays to be swayed by popularity or box office receipts, as contrasted with significance in play, it not only ceases to be identifiable as [part of] the Little Theatre movement, but also loses its avowed reason for existence. Paradoxical though it may sound the Little Theatre group does not have to be small and it is often true that the plays become popular. The point is that the plays must be significant whether they are popular or not…The distinguishing mark of Little Theatre enterprises is the complete elimination of box office influence, the insistence upon plays of a character to stimulate knowledge of and love for the drama as an art rather than as casual entertainment…Community Theatre, on the other hand, emphasizes the popularity of the plays selected as evidenced by box office receipts [and] accepts no responsibility for the plays as educators in the art…The Buffalo Players have tried to be both [kinds of company] and the result has been by no means unqualifiedly happy, either for the members or for the development of the drama in Buffalo.[26]

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Brief Chronology of Studio Arena Theatre and the City of Buffalo

- 1900

- Studio Club formed. Buffalo’s population 352,387, making it 8th largest city in the USA.

- 1901

- Pan-American Exhibition held.

- 1910

- Buffalo greatest grain port in the world. Economy diverse and flourishing: iron, steel, auto, chemicals, manufactures, agriculture. Population ethnically divided and localised: a WASP elite and Jewish, Irish, Polish, German and Italian neighbourhoods.

- 1920–1922

- Buffalo Players formed. Allendale Theatre rented. Buffalo’s population 506,775, making it 11th largest city in the USA. Buffalo banking and utilities start investing in other cities. Wealth and influence exits to New York City, Cleveland and Minneapolis.

- 1927

- Buffalo Players dissolves. Remainder regroup as Studio Theatre under Jane Keeler. Move to Lodge, at corner of Elmwood and Anderson Place. Buffalo makes record profits but population growth slows from 19% to 13%.

- 1930

- Studio Theatre wins Belasco Cup with Frederick Molnar’s The Man who Married a Dumb Wife.

- 1932

- Lodge closed due to fire regulations. Gaiety Theatre offered rent-free by Mike Shea.

- 1935

- Mike Shea dies. Studio Theatre moves to Teck Theatre. Summer seasons at Orchard Park.

- 1936

- Studio Theatre incorporates as an educational institution under the New York State Board of Regents.

- 1937

- Studio Theatre purchases Universalist Church, at corner of Lafayette and Hoyts. Rockefeller grant of $25,000 to refurbish. Depression hits Buffalo. Rationalisation and concentration of capital and factory ownership. The city still economically strong, with 13 trunk line railroads and an active port. Companies in the area include Westinghouse, Remington, Bethlehem Steel, Dupont, Union Carbide, Bell Aircraft and Hooker Chemical.

- 1940–1949

- Buffalo experiences successive war booms.

- 1950

- Buffalo’s population 580,132, making it 15th largest city in the USA.

- 1951

- Greater Buffalo Development Foundation founded.

- 1958

- Jane Keeler retires. Michael Sinclaire appointed Director of Studio Theatre, then Kay Kingdon.

- 1959

- Opening of St Lawrence Seaway and loss of wheat trade. Political power concentrated in the Democratic Party machine, largely Catholic; economic power in the WASP elite, largely bankers and lawyers.

- 1962

- Neal Du Brock takes over the company as Artistic Director. Comes via Los Angeles and New York, where he was involved in Circle in the Square. Has directed a number of successful, non-professional productions in Buffalo. A Republican mayor, Chester Kowal, elected to office, but the party splits over personality issues. Governor Rockefeller announces plans for a new State University of New York (SUNY) campus at Buffalo.

- 1964

- East Side Community Organisation (later BUILD) founded—an African American association. Decision made to locate new University campus in suburban Amherst. Debate about location of a new football stadium splits media and elite opinion. It is eventually located in Orchard Park. Buffalo chosen for the Model City Program. Attempt at regional consolidation of local police forces defeated at referendum by a handful of county villages.

- 1965

- Company becomes Studio Arena Theatre, a professional, not-for-profit Equity Theatre. Opens a new theatre in the former Town Casino, at 681 Main Street. Is key player in the regional theatre movement.

- 1966

- Plans to develop Main Street put forward. Chester Kowal replaced as mayor by Democrat Frank Sedita.

- 1968

- Company stages premiere of Edward Albee’s Box Mao Box. Buffalo’s population 532,759, making it 20th largest city in the USA. African American population increases from 6% to 10% over the next 20 years.

- 1969

- Niagara Frontier Transit Authority takes first steps to implement a rapid transit system. Retirement of ‘old guard’ of Buffalo’s civic leaders. White, inner-city residents relocate to the suburbs.

- 1970

- Buffalo population 462,768, 28th largest city in the USA. Regional steel, auto and chemical companies start to withdraw. Over the decade, General Motors, Ford, Bethlehem and Republic Steel shed 50% of their jobs. OPEC oil crisis of 1973 accelerates de-industrialisation. Union–management relations adversarial. Wages for blue-collar workers increase beyond the national average. Six railroads close. Hopes for an economic focus in light-, medium- and high-technology sectors.

- 1975

- Work on an underground rapid transit system linking downtown with the University begins. Immediately revised to be partially above ground.

- 1976

- Buffalo accedes to court orders to integrate its public schools.

- 1977

- James Griffin, an Independent candidate, becomes mayor and remains in office for 16 years.

- 1978

- Studio Arena receives Federal Economic Development Administration grant and renovates the Palace Burlesque Theatre, a former nightclub, at 710 Main Street, with 637 seats in a thrust stage configuration.

- 1980

- Buffalo’s population 350,000, making it 37th largest city in the USA. Manufacturing sector continues to decline. Loss of all but two auto companies. Lower-paid service sector swells. Public funding for the ‘sick’ city balloons by 110%, constituting nearly 50% of its annual revenue. A ‘Group of Eighteen’ leaders put forward a corporate renewal strategy. Downtown development plans accumulate. Horizons Waterfront Commission fiasco. Du Brock fired by Studio Arena Board. David Frank takes over as Artistic Director. Managing directors Brian Wyatt and later Raymond Bonnard appointed. Both leave under a cloud. National Endowment for the Arts funding winds down.

- 1986

- The rapid transit system opens, only half complete. Relations between mayor and city council reach an impasse. Warren Buffett buys Buffalo News and its editorials become less conservative.

- 1991

- Greater Buffalo Development Foundation and Chamber of Commerce merge. Frank resigns at Studio Arena and Gavin Cameron-Webb takes over as Artistic Director.

- 1992

- Studio Two opens as an adjunct experimental space, offering Angels in America and How I Learnt to Drive. Closes almost immediately.

- 1993

- Buffalo Niagara Partnership founded.

- 1994

- Studio Arena stages first of its ‘Buffalo Plays’: Tom Dudzick’s Over the Tavern and A. R. Gurney’s The Snow Ball. Buffalo’s population 328,648, making it 50th largest city in the USA.

- 1997

- Failure of South Buffalo Redevelopment Plan.

- 1999

- Erie–Niagara Regional Partnership founded. Study finds that over 50% of membership of local boards are bankers or lawyers.

- 2003

- State Comptroller establishes the Buffalo Fiscal Stability Authority board.

- 2005

- Cultural Resources Advisory Board threatens Studio Arena’s funding of $200,000 annually. Company takes its Johnny Cash musical Ring of Fire to Broadway. It fails. Annual deficit of $314,473. Accumulated deficit of $1.4 million (approx.)

- 2006

- Cameron-Webb resigns. Kathleen Gaffney takes over as Artistic Director. In November, Ken Neufeld is fired as Managing Director and Gaffney must do both jobs.

- 2007

- In January, Gaffney lays off 14 Studio Arena staff and scales back seasons to six productions. Moves to include shows by Road Less Travelled and MusicalFare bring out Actors Equity Union against her. In September, merger explored with Artpark but this is rejected at the city level. In December, emergency fundraising nets $225,000 and heads off closure. Company downgraded from a LORT ‘B’ theatre to a LORT ‘D’. GFC hits the US economy.

- 2008

- In February, Studio Arena ceases selling tickets and cancels the remainder of its season. In June, files for ‘Chapter 11 bankruptcy’. In September, Gaffney is fired.

- 2009

- Studio Arena files for ‘Chapter 7 bankruptcy’, with debts of $3 million (approx.), the majority owed to its own endowment. Buffalo’s population 292,648, making it 57th largest city in the USA. City tax revenue falls by $19 million. Executive Director of Buffalo’s Arts Council, Celeste Lawson, accused of mismanagement, loses re-granting money from New York’s State Council on the Arts.

- 2011

- Buffalo’s population 261,310, making it 70th largest city in the USA.

References and Notes

- Allen Grossman. “Port Sunlight.” Boston Review. 2004. Available online: http://bostonreview.net/grossman-port-sunlight (accessed on 27 August 2016).

- Timothy Neeson (freelance photographer), in communication with the author, September 2012.

- Marvin Carlson. Places of Performance: The Semiotics of Theatre Architecture. New York: Cornell University Press, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Howard Saul Becker. Art Worlds, rev. ed. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Peter Hallward. Badiou: A Subject to Truth. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Alain Badiou. Infinite Thought: Truth and the Return to Philosophy. Justin Clemens, and Oliver Feltham, trans. and ed. London and New York: Continuum, 1999, pp. 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Alain Badiou. Being and Event. Translated by Oliver Feltham. London and New York: Continuum, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Alain Badiou. The Logics of Worlds: Being and Event. Translated by Alberto Toscano. London and New York: Continuum, 2009, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Justin Clemens. “Doubles of Nothing: The Problem of Binding Truth to Being in the Work of Alain Badiou.” Filozofski verstnik 2 (2005): 97–111. [Google Scholar]

- Peter Hallward. “Order and Event: On Badiou’s Logics of Worlds.” New Left Review 35 (2008): 97–122. [Google Scholar]

- Alain Badiou. St Paul: The Foundation of Universalism. Translated by Ray Brassier. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Note on Studio Club, Undated, Studio Arena Theatre History, Box 073, Studio Arena Archives, Buffalo State University Library.

- Anthony Chase. “Blossom Cohan.” Artvoice. 30 March 2006. Available online: http://artvoice.com/issues/v5n13/blossom_cohan.html (accessed on 16 August 2016).

- Diana Dillaway. Power Failure: Politics, Patronage, and the Economic Future of Buffalo, New York. Amherst: Prometheus Books, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Goldman. City on the Edge: Buffalo, New York 1900 to Present. Amherst: Prometheus Books, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mark Goldman. High Hopes: The Rise and Decline of Buffalo, New York. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Lillian Serece Williams. Strangers in the Land of Paradise: The Creation of an African American Community, Buffalo New York, 1900–1940. Bloomington and Indianapolis: University of Indiana Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- View of Studio Theatre, Roger Gratwick, 1962, Studio Arena Theatre History, Box 073, Studio Arena Archives, Buffalo State University Library.

- Anthony Chase. “Saving Studio Arena.” Artvoice. 26 December 2007. Available online: http://artvoice.com/issues/v6n52/saving_studio_arena.html (accessed on 27 August 2016).

- Studio Arena Theatre History, Box 073, Studio Arena Archives, Buffalo State University Library.

- Quoted in Richard Huntington. “Singled Out: Arts Community Cries Foul.” Buffalo News, 6 November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjit Sandhu. Buffalo Theatres Prior to 1930: An Ever-growing Index of References Compiled from Scrapbooks and Card Catalogues at the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library and the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society, From Previous Researchers and From Original Research, Privately printed. 2002.

- Ranjit Sandu. “Buffalo’s Forgotten Theatres.” 2002. Available online: http://www.buffaloah.com/h/movie/sandhu/index.html (accessed on 21 June 2012).

- George Kunz. Buffalo Memories: Gone but Not Forgotten. Buffalo: Canisius College Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph Wesley Zeigler. Regional Theatre: The Revolutionary Stage. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Buffalo Artists Register, Lee Heacock, 1927, Studio Arena Theatre History, Box 073, Studio Arena Archives, Buffalo State University Library.

- Note on transition from Buffalo Players to Studio Theatre, Studio Arena Theatre History, Box 073, Studio Arena Archives, Buffalo State University Library.

- “Buffalo Comprehensive Plan.” 2011. Available online: http://www.ci.buffalo.ny.us/files/1_2_1/Mayor/COB_Comprehensive_Plan/index.html (accessed on 12 May 2011).

- 1See especially ([10], Chapter 9, “Lightning Strikes: Art and Life during the 1960s”, pp. 221–54).

- 2Dillaway has been criticised for not naming the sources of her information about the behind-the-scenes manoeuvring in Buffalo during this period. Despite this, and a compressed and acronym-thick narrative, her study lays out the saga of the city’s post-war decline with accessibility and force.

- 3For biographies of these and other key company personalities, see [20].

- 4I am grateful to Anthony Chase for providing me with a complete list of Studio Arena Theatre’s productions. For a list of productions by the Buffalo Players and Studio Theatre, see [20].

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meyrick, J. The Unmade City: Subjectivity, Buffalo and the Sad Fate of Studio Arena Theatre. Humanities 2016, 5, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/h5030074

Meyrick J. The Unmade City: Subjectivity, Buffalo and the Sad Fate of Studio Arena Theatre. Humanities. 2016; 5(3):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/h5030074

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeyrick, Julian. 2016. "The Unmade City: Subjectivity, Buffalo and the Sad Fate of Studio Arena Theatre" Humanities 5, no. 3: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/h5030074

APA StyleMeyrick, J. (2016). The Unmade City: Subjectivity, Buffalo and the Sad Fate of Studio Arena Theatre. Humanities, 5(3), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/h5030074