Abstract

Working between the Amos Gitai film One Day You’ll Understand (2008) and the 1987 Klaus Barbie trial against which it is set, the article explores how the trial marked a decisive turning point in France’s relationship to its wartime past. Of Barbie’s hundreds of crimes, including murder, torture, rape, and deportation, only those of the gravest nature, 41 separate counts of crimes against humanity, were pursued in the French court in Lyon. Not only did the trial raise crucial juridical questions involving the status of victims and the definition of crimes against humanity but, extending into the private sphere, it became the occasion for citizens to address heretofore silenced aspects of their own family histories and conduct trials of a more personal nature. Whereas the law in general seeks to contain historical trauma and to translate it into legal-conscious terminology, it is often the trauma that takes over, transforming the trial into “another scene” (Freud) in which an unmastered past is unwittingly repeated and unconsciously acted out. Such failures of translation, far from being simply legal shortcomings, open a space between grief and grievance, one through which it is possible to explore both how family secrets are disowned from one generation to the next, and how deeply flawed legal proceedings such as the Barbie trial may “release accumulated social toxins” (Kaplan) and thereby expose unaddressed dimensions of French postwar (and -colonial) history.

“It was not a story to pass on”Toni Morrison, Beloved

Much work has been done in recent years—primarily by legal scholars—on the vexed relationship between atrocity crimes and legal response. While deeply indebted to this work, I take as my own point of departure Shoshana Felman’s path-breaking book The Juridical Unconscious: Trials and Traumas of the Twentieth Century, published in 2002, which stresses not only questions of jurisprudence but the unwitting repetition of historical trauma and the surprisingly unconscious dimension of the legal proceedings themselves. In the opening pages of her study, Felman describes this dynamic between trials and trauma in the following terms:

The law tries to contain the trauma and to translate it into legal-conscious terminology, thus reducing its strange interruption. Uncannily, however, while the law strives to contain the trauma, it often is in fact the trauma that takes over and whose surreptitious logic in the end reclaims the trial…A pattern emerges in which the trial, while it tries to put an end to trauma, inadvertently performs an acting out of it. Unknowingly, the trial thus repeats the trauma, reenacts its structures…[L]ike society itself and despite its conscious frames and rational foundations, the law has quite conspicuously and remarkably its own structural (professional) unconscious.()

For Felman, it is often the moments of collapse in juridical proceedings that are the most telling; for they give us surprising and otherwise unavailable access to the unconscious dimension of those trials. A case in point is her reading of the prosecution of Adolf Eichmann in which she focuses on a moment subsequently screened over and over on Israeli television like a traumatic flashback when the witness Yehiel Dinur—also known by his pen name, Ka-Tzetnik—suddenly falls silent and lapses into a coma on the witness stand. It is a moment when the witness feels himself torn between his two names and identities, between his place among the living and his vision of himself still among the dead and dying.

Elizabeth Rottenberg elaborates on the significance of such moments of collapse and failure, noting that what they “point to—insofar as they prove to be moments of legal and conceptual breakthrough—is a radical form of human grief”. Although the Eichmann and Simpson trials examined by Felman are, in Rottenberg’s words, both “concerned with the translation of grief into grievance, the jurisprudential drama of these cases is what finally succeeds in testifying to an abyss of mourning—an abyss to which a literary justice can, in the end, bear witness” ().

In what follows, I explore this relationship between grief and grievance and above all a certain failure of translation by which the two may be linked. I do so through an examination of Amos () film One Day You’ll Understand [Plus tard, tu comprendras], the 2005 memoir by Jérôme Clément on which it was based, and the 1987 Klaus Barbie trial against which it is set. While the complex relationship between the film and the memoir—not to mention the screenplay co-written by Clément and the book, Maintenant je sais, he would later write about the making of the film—deserve consideration in their own right, I wish to note at this point the surprising absence of any mention of the Barbie trial or even of Marcel Orphuls’ documentary Hotel Teminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie in Clément’s original memoir. The absence is surprising given the works Clément, former director of the Centre national de cinématographie and founder of the influential television network ARTE, does discuss; these include Renais’ Night and Fog, the Eichmann trial, Lanzmann’s Shoah, Paxton’s book on Vichy, Ophuls’ The Sorrow and the Pity, Chirac’s landmark 1995 address delivered on the anniversary of the Vel’ d’Hiv’ round up, the establishment in 1999 of a French Reparations Commission,1 and the inauguration in 2005 of the Wall of Names at the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris.

Only when writing the screenplay does Clément think to include the trial. As he recalls in his book about the making of the film, it was a visit in 2005 to the children’s home in Izieu, the orphanage which Barbie had raided in 1944, rounding up the Jewish children he found there and sending them all to their death in Auschwitz, that first prompted Clément to reflect on the turning point in French postwar memory represented by the Barbie trial. As the trial judge, Pierre Truche, himself explained to Clément during his visit to Lyon:

You have to understand what a decisive year 1987 was in terms of France’s relation to its wartime past. For it was in that year that we first realized that Klaus Barbie was responsible not only for the assassination of Jean Moulin, hero of the Resistance, but also for the murder of Jewish children. What the Barbie trial brought to light was just how central the extermination of the Jews was to the Nazi regime. [Trans. mine].()

It was this new understanding of French history that prompted Clément to alter his memoir when adapting it for the screen. Whereas the memoir begins with the death of his mother in June 1996 and is conceived very much as a work of mourning, the film opens in May 1987 with the mother still very much alive and the Barbie trial in its eighth day. In the first scene in which the mother appears, the last part of which is carefully constructed as one long take, we see her become increasingly engrossed, almost against her will, in the Barbie trial being broadcast live on French television.

Recentering the original story in this way, the film draws attention to the act of witnessing—both the testimony given in the course of the trial and the witnessing of the trial by the French public. To make these two related forms of witnessing line up, the film takes certain liberties with the historical record, going so far as to incorporate archival footage of the trial first made available to the public only in 2007 into its narrative. Thus, unless one knows better, one has the impression in watching the film that contemporary audiences—including, of course, the protagonist’s mother—had in fact been able to watch the trial proceedings live on French television in 1987.

Why would Gitai have resorted to this cinematic sleight of hand? Was it perhaps in order to draw attention to the broadcast politics of the times, a matter to which we will turn in a moment? Or was it simply a way of drawing attention to the central narrative conceit of the film? That conceit has to do with the interaction of private and public tribunals, with the implicit connection drawn in the film between trials conducted behind closed doors in many French homes at the time and the highly publicized, highly politicized trial of the notorious “Butcher of Lyon”.

With regard to the broadcast politics of the Barbie trial, it should be noted that, as with Nuremberg and Eichmann, the proceedings were staged to serve the ends of both justice and didactic legality. Explaining this twofold agenda, the legal scholar, Lawrence Douglas, recalls how the French government described the Barbie prosecution as “a pedagogical trial,” which in the words of Prime Minister Pierre Mauroy, would first “enable French justice to do its work, and second, ... honor the memory of that time of grieving and struggle by which France preserved her honor” (). Douglas further notes that Minister of Communications Georges Filoud proposed broadcasting the trial live on French television, something without precedent in the annals of French broadcasting. Although Filoud’s proposal was ultimately rejected, cameras were present in the Lyon courtroom—not to show the trial live on television but to record it for posterity, as the Parliament passed a law permitting the filming of important trials for historical purposes.2

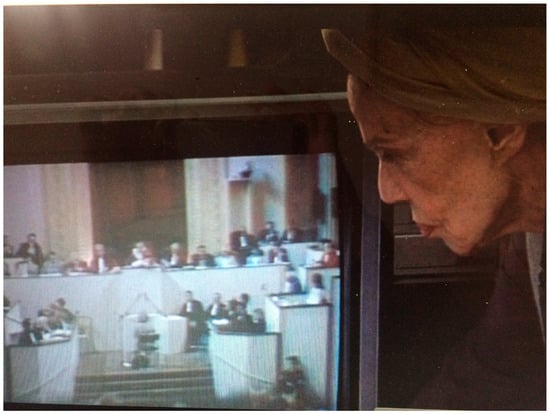

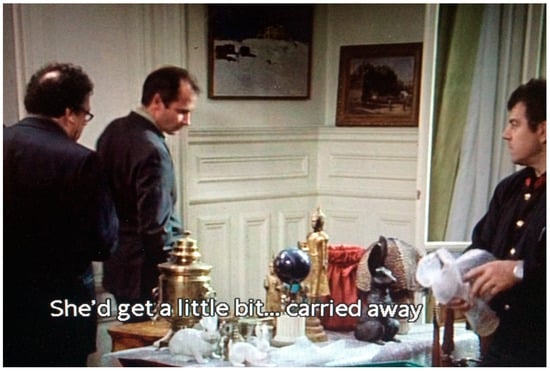

As noted earlier, this archival footage was first made available in 2007, twenty years after the fact, and was used by Gitai in the scene in which the audience is first introduced to the protagonist’s mother, played by the incomparable Jeanne Moreau (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Testimony of Lea Katz.

There is much to be said about this scene—about the way it gradually shifts from listening to viewing; about the point of the SS dagger and its strategic placement on the mantelpiece; about the relationship between the woman testifying in the trial and the one witnessing it from home; about the painful connection between words and wounds; and, of course, about the content of this particular testimonial excerpt. But because it is possible in the context of this article to focus only on static images rather than on entire cinematic scenes, I pass over these particular issues and consider instead the more general narrative and structural significance of the scene.

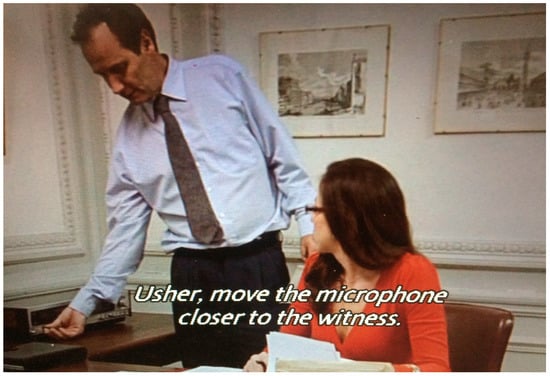

It is no exaggeration to say that the film remains stuck on this moment in the Barbie trial; for in the next scene, no longer set in the mother’s home but instead in her son’s office, the same testimony, that of Lea Katz, an eyewitness to the notorious roundup of Jews at the UGIF on 9 February 1943, is broadcast once again. This time, however, her testimony is heard on the radio instead of being seen on television (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Radio Broadcast of Katz Testimony.

If the film moves in place at this particular instant, it does so for two related reasons: first, in order to underscore the significance of a certain moment in the trial and the apparent difficulty of getting beyond it; second, in order to stress the simultaneity of the two scenes of witnessing of the trial. Taking place at the same time, these scenes are effectively set in dialogue with each other. So not only do we see the mother and son, each following the trial in her or his own way, become increasingly implicated in it, but we also see the national wounds laid bare by the proceedings opening at the heart of the Bastien family, the father’s side of which was Catholic, the mother’s Jewish. As these wounds open, the scene of the trial itself shifts to the private sphere with the son now cast in the role of examining magistrate and the mother in the role of witness. Only now does the son seek to break the silence his mother had scrupulously maintained since the war about the deportation of her parents, the fate of their possessions, and her own relation to things Jewish.

As one might imagine, the trial conducted within the family has a very different tone from that of the official proceedings. Whereas in the latter, witnesses were subjected to intense questioning and often hostile cross-examination; judges were judged and the French legal system itself was put on trial by the radical defense attorney Jacques Vergès; and the very definition of crimes against humanity was altered for questionable political reasons having to do with the statute of limitations on war crimes, the claims of French Resistance groups, and the need of the government to shield itself from prosecution for crimes committed during the Algerian war; in the Bastien family, everything proceeds with utmost civility. Here, examiner and witness dance gently around each other. The son asks, the mother deflects, never exactly refusing to answer, just not now, plus tard.

As the title suggests, this is a film about time and understanding, about the ways in which the two never quite coincide. While comprehension seems to be what is promised, that promise is never exactly kept nor, for that matter, ever simply broken. Instead, it is kept only to the extent that it is kept open, kept in a state of abeyance. This is the side-stepping dance of deferral that mother and son, locked in an adversarial embrace, perform.

As the two turn around each other, asking and evading, the film itself turns in circles. For a long time, it doesn’t seem to go anywhere and yet one feels the son’s mounting frustration, his desire to probe held in check not just by his mother’s resistance but by his own intuitive sense of just how far he can go. Needless to say, the more he restrains himself, the more intense his desire to know becomes. Indeed, the film slowly fills with this mounting tension. The air in the closed rooms of the family’s Parisian apartments in fact becomes so thick, so saturated with lingering questions and evasive responses, that the characters are seen repeatedly opening windows and gasping for air.

As the tension both within and between these characters builds, the pace of the film increases, turning in ever tightening circles towards its center. That center is marked, not surprisingly, by another dance. Yet, before coming to it, Jérôme—or Victor as he is now called in Gitai’s film—must himself perform a number of carefully choreographed preparatory steps involving a progression from writing to speaking to physical movement—as though the questions accumulating within him had the effect of mobilizing his energies and setting him literally in motion. Thus, in the first half of the film, we see him move successively from the papers scattered across his desk like the disordered family history he is trying desperately to sort out, to a series of verbal exchanges with his mother that go nowhere, to a car trip he takes with his wife and children to Salviac where he has arranged to meet with the mayor of the small southwestern French town in which his Jewish grandparents had been hidden.

The exchange between the two men starts slowly as the mayor, a five-year-old boy at the time he knew Victor’s grandparents, begins to tell their story. The account commences in the past tense and yet as the memories recounted start to overtake the speaker he switches into the present. The presence of the past is at its most intense when the two men reach the room in which the grandparents had been hidden. Here, the narration comes to an end as Victor abruptly dismisses the mayor, asking to be left alone for a moment in the room.

Nowhere in the film is the question of witnessing posed in a more highly charged or unsettling way. For at the very moment Victor touches a piece of peeling wallpaper, it in turn touches off a kind of explosion in him (see Figure 3). Or to be more precise, what explodes are disembodied memories, memories belonging to no one, memories no one person seems able to grasp. They are memories, the visual language of the film suggests, that have been walled up and papered over—not only in the room itself but in the Bastien–Gornick family and in French society in general. These memories now explode onto the scene like a traumatic flashback. Suddenly, we are transported back into the past in which another dance is being performed.

Figure 3.

Peeling Wallpaper.

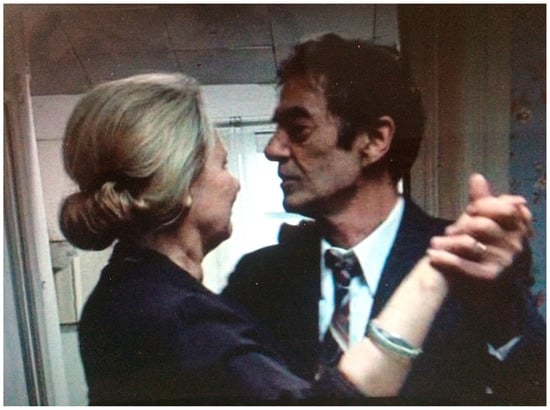

Like the dance of the mother and son at the beginning of the film, this one involving Victor’s grandmother and grandfather begins slowly, gently, and lovingly (see Figure 4). The two look deeply into each other’s eyes as though for the last time while familiar music plays quietly in the background. Yet, as the music speeds up, the dance partners turn ever more rapidly around each other and the action itself becomes harder and harder for the audience to follow. The film cuts with increasing rapidity between inside and out, between hidden Jews, caged animals, and those who have come to hunt them down. As chaos, terror, and panic spread, a sense of visual disorientation is compounded by ever-increasing levels of acoustic interference. The familiarity of the French language quickly gives way to a confusion of tongues, to linguistic babble that in its turn disintegrates into pure, almost deafening noise. At the center of this wrenchingly violent scene and at the height of its overwhelming chaos, all the audience sees is gravel crushed under foot. All it hears is the grinding of stones, the firing of guns, the growling of dogs, and the incoherent barking of commands (see Figure 5). What began slowly as a couple’s turning embrace quickly accelerates into a vertiginous dance of death.

Figure 4.

Dance.

Figure 5.

Roundup in Salviac.

This is the dead center of the film, the vortex into which its various perspectives collapse. While the scene eventually shifts away from the stones being crushed underfoot, the sound of their clattering remains in the audience’s ears, becoming particularly resonant in a later scene in which memorial stones are the subject of a conversation between Victor’s sister and his wife. Christians put flowers on graves, one tells the other, while Jews place stones in memory of their years of wandering in the desert. In the desert, it is said, stones served as path markers, as touchstones, as points de repère; they were a way to get one’s bearings.

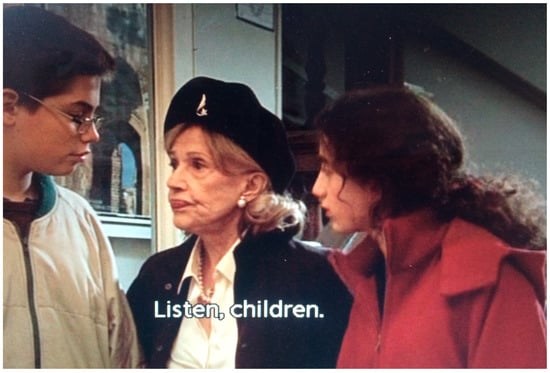

Bearing this scene in mind, let us return to an earlier, closely related one in which the question of Jewish mourning is already posed. In it, Raymonde—or Rivka as she is now called—takes her own grandchildren to a synagogue on Yom Kippur, the day on which, she tells them, Jews remember their dead (see Figure 6). The scene is particularly poignant since we have just learned that Rivka is herself fatally ill. Indeed, at the point she takes her grandchildren to the synagogue for the first and last time, she is positioned at once as one of the mourners and as someone who is herself about to be mourned. Standing in a sense between the living and the dead, Rivka performs a strikingly equivocal act. For at this moment, what she passes on to her grandchildren, or rather to her grandson, is the yellow star marked juif which the Jews of occupied France had been made to wear.

Figure 6.

Entrance to Synagogue.

How are we to understand this scene of transmission? What is being passed on? It is the first time Rivka acknowledges to her grandchildren that she is Jewish, doing so in a place symbolizing the survival of Jewish life in France and in view of an Israeli tourist poster hanging conspicuously in the background. Yet, this locus of Jewish survival is a place that seems to have no other place in her life—which is perhaps why she only first enters it with the children at a time when she herself is no longer fully among the living, nor quite yet among the dead.

Survival here no longer means simply outliving or living beyond but is associated instead with the liminal space and disjointed time of that which exceeds the very opposition of life and death. It is this threshold of survival on which Rivka will have verged not just at the end but over the last forty years. It is a place unlike any other, a “no place” she will have kept secret not only from others but herself, a place through which family secrets will have secretly been passed. When in the end Rivka gives her grandchildren the Jewish star she had been made to wear, a sign for her of belonging to and with the excluded of French history, she also passes on her own secret, unacknowledged grief.3

Elsewhere in her life, this grief seems to be stored in evocative objects that fill her apartment (see Figure 7). Yet, strangely enough, no one of them ever appears to stay in her possession for very long, as though the purpose of their incessant exchange were to express the passing of those she could not hold on to, to grieve with each exchange their ceaseless passing, to prolong with each new deal her endless grieving.4 Commenting on his mother’s behavior, Clément observes in his memoir, “Toujours acheter, vendre, marchander. Plus pour le geste que le résultat” [‘To always be buying, selling, bargaining. More for the gesture than the result’] ().

Figure 7.

Preparation for Auction.

In the end, we come to see that it is not so much Rivka’s secret grief as her secret way of grieving that passes in compulsively repeated gestures between generations. Thus, upon her demise, Jean, like his mother, prepares for another auction. Or as Clément reflects in his memoir, “Finalement, en remettant ces objets en vente, je les rends à leurs destination initiale. Ils passent de main en main. C’est bien ainsi, je n’en ai été que le proprietaire momentané” [‘Finally in putting these objects up for sale I am returning them to their original destination. They pass from hand to hand. It’s good this way. I was never more than the temporary owner’] ().

Gitai takes this movement of circulation and exchange one step further. Moving beyond the auctions in which mother and son each in turn take part, he adds a final scene set at the CIVS established in 1999 by the French government in recognition of its responsibility in the deportation and murder of French Jews. During his appointment at the commission, Victor sees a price being placed on everything his maternal grandparents had once owned. Yet, rather than feeling that justice is now finally being served, that the story of his mother’s side of the family, kept secret for close to sixty years, is now being publicly aired and officially addressed, Victor seems only to feel increasingly uncomfortable, anxious and overwhelmed (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

CIVS.

Whereas in the auctions, memory-filled objects were placed in circulation, here it is memories preserved in official documents that are lost almost as quickly and suddenly as they are evoked. Indeed, Victor seems overwhelmed not so much by these fleeting memories themselves as by their flight in rapid succession, their abrupt passage conjuring the passing of those he never knew except as the ghosts of his mother’s apartment. The disorienting speed at which these memories pass is itself evocative of the earlier scene of the grandparents’ arrest. As noted above, this is less a discrete scene than a vertiginously fast-paced, quickly cut montage, less a memory any character in the film is able to access than a sudden explosion of memory fragments. It is this traumatically shattered—and still shattering—scene of her parents’ abrupt passing that the mother never witnesses as such but that seems to return in various guises throughout the film and to be rehearsed in the incessant exchange of objects associated with her clandestine way of grieving.

Fleeing from this final encounter with the reparations people and all that it seems inadvertently to touch on, Victor walks down a long hallway, the film’s last spoken word traces no doubt lingering in his ear. He comes to a halt finally before another open window, where he is left once again to catch his breath, his gaze seemingly fixed on the base of the Eiffel Tower (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

View of Eiffel Tower from CIVS.

Why do his eyes not follow the ascent of the tower’s famously tapering lines? Why does the filmmaker, a trained architect, prevent him as well as the viewer from looking upward, from experiencing the expansive sense of relief associated with such a skyward gaze? Particularly in view of the television and radio transmissions of the Barbie trial which play such a central role in the opening moments of the film, it is important to recall how the initial lines of the tower were extended and further elongated by the addition of a broadcast antenna in 1957. Not only is this antenna pointedly kept out of view in the shot in question but as the eye is made to dwell exclusively on the tower’s base, the viewer is reminded of the pent-up energies accumulating below. Such energies, it is suggested, are denied more traditional modes of transmission, modes associated with the radio and television signals broadcast over public airwaves from the antenna above. Yet, what remains below, remaining like grief denied successful translation into juridical grievance or financial compensation, is not simply lost in transmission. Remaining unconsciously insistent, it passes instead via other, more subliminal channels.

After a long pause, the camera eventually turns from this view. Yet, as though to suggest that something grievous will have happened in the meantime, it is no longer the protagonist’s perspective the audience shares. Victor has himself somehow vanished from the scene and it is now the withdrawing camera that returns alone, moving visibly backwards down a long corridor (see Figure 10).

Figure 10.

CIVS Corridor.

Retreating from the daylight that had entered through the open window where Victor is last seen, and withdrawing from all the other sources of inner illumination, the camera’s eye closes in the end, fading like the scene itself into total darkness. The ending seems to equate these last glimmers of light with the invisible yet hauntingly palpable traces of another family legacy, a secret grief secretly passed from mother to son and beyond.

This grieving, unwittingly disowned from generation to generation, is comparable to the objects Jean puts back in circulation, returning them, as Clément says, to their destination initiale. This grief, without object and without end, is in dialogue with the Barbie trial against which the film is set and with which it begins. The “abyss of mourning”, still open within the family, bears witness to the failure of the trial itself to translate grief into grievance.

Reading the family story back onto the trial, we come to see the endless grieving it performs as an unaddressed grievance, as a symptom of the many failures of the trial: among them, its confusion of the Resistance and the Jewish victims; its dilution of the category of crimes against humanity;5 and its rather outrageous implication that a democratic state cannot commit such crimes6. The “no place” of Rivka’s grief may thus be said to bear witness to a certain non-lieu of the trial—the term non-lieu referring in this case less to a dismissal of charges than to the confusing way in which they were brought. This confusion ended up pitting the various plaintiffs against each other and gave the defense attorney Jacques Vergès the opportunity to present what Alice Kaplan has aptly referred to as a Pandora’s box version of crimes against humanity, a version where one crime would effectively call up all the others, making them equally intolerable and putting them into competition with each other so that justice always seems hypocritical7.

Kaplan summarizes this state of confusion in her excellent introduction to the English translation of Alain Finkielkraut’s Remembering in Vain: The Klaus Barbie Trial and Crimes Against Humanity published in 1992:

The Barbie trial was, for France, like an abreaction in psychoanalysis, a single relived piece of trauma that brings the other buried pieces back to life. When abreaction works, it produces a catharsis and cure. Finkielkraut would contend that the Barbie trial was the very opposite: that lots of time and work went into avoiding what should have been central; that with avoidance and denial came the release of accumulated social toxins.()

Kaplan’s potent metaphor returns us in the end to Felman’s description of the law as a necessarily flawed containment strategy. “The law,” she says, “tries to contain the trauma and to translate it into legal-conscious terminology, thus reducing its strange interruption. Uncannily, however, while the law strives to contain the trauma, it often is in fact the trauma that takes over and whose surreptitious logic in the end reclaims the trial” (). If there is a difference between Kaplan’s and Felman’s perspectives, it perhaps lies in the latter’s sense that failure is not incidental to the law, is not avoidable in its engagement with historical trauma. Such failures for Felman instead mark its very fault lines, its constitutive openness to the supplement of what she calls literary justice. One of the most provocative questions she asks in The Juridical Unconscious is whether literature (and film) in their supplementary relationship to the law might do justice to the trauma in a way the law does not, or cannot.

In her most sweeping response to this question, Felman writes: “Literature is a dimension of concrete embodiment and a language of infinitude that, in contrast to the language of the law, encapsulates not closure but precisely what in a given legal case refuses to be closed and cannot be closed. It is to this refusal of the trauma to be closed that literature does justice” ().

Where does this leave us then with regard to One Day You’ll Understand? I would argue that Clément, in re-opening the crypt of his initial memoir, transforms the work of mourning he had sought to accomplish there into something much larger. Turning it, with his writing partner, Serge Moati, into a screenplay and then with Amos Gitai into a film, Clément repositions it in the very margin of legal closure, on the brink of the abyss that underlies the law. Such repositioning turns the memoir itself into an interminable work of mourning, a work that in many essential respects escapes him and in the most concrete ways no longer belongs to him. It is no doubt for this reason that he opens the sequel to the memoir with the words of another. His sister, the philosopher Catherine Clément, tells him, “Tu crois en avoir fini…tu te trompes, on n’en a jamais fini” [‘You think you’re finished with it. You’re wrong. One is never finished with it’] ().

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Clément, Jerôme. 2008. Plus Tard, tu Comprendras Suivi de Maintenant, Je Sais. Paris: Editions Grasset & Fasquelle. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, Lawrence. 2001. The Memory of Judgment: Making Law and History in the Trials of the Holocaust. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Felman, Shoshana. 2002. The Juridical Unconscious: Trials and Traumas in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Finkielkraut, Alain. 1992. Remembering in Vain: The Klaus Barbie Trial and Crimes against Humanity. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gitai, Amos. 2008. One Day You’ll Understand [Plus Tard, tu Comprendras]. Paris: Agav Films. [Google Scholar]

- Proust, Marcel. 2003. In Search of Lost Time, Volume 1: Swann’s Way. New York: Modern Library. [Google Scholar]

- Rottenberg, Elizabeth. 2004. The Juridical Unconscious: Trials and Traumas in the Twentieth Century (review). MLN 119: 1098–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousso, Henry. 1991. The Vichy Syndrome: History and Memory in France since 1944. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | La Commission pour l’indemnisation des victimes de spoliations intervenues du fait des législations antisémites en vigueur pendant l′Occupation (CIVS). |

| 2 | See (); see also (). |

| 3 | Positioned among the mourners and herself about to be mourned, she is neither simply the subject nor object of grief but more liminally and ambiguously its carrier. |

| 4 | This is in contrast to the Proustian view of memory articulated in the following famous passage from Swan’s Way: “The past is hidden somewhere outside the realm [of voluntary memory], beyond the reach, of intellect, in some material object … which we do not suspect. And as for that object, it depends on chance whether we come upon it or not before we ourselves must die” (). |

| 5 | The court’s decision meant that deportations of the Jews and of the members of the Resistance were legally equivalent acts (). |

| 6 | Whereas at Nuremberg crimes against humanity were essentially enfolded into war crimes, the Barbie trial, “in a stunning inversion, did just the opposite: war crimes were enfolded into crimes against humanity, which now, in the interpretation of French courts, became a master category embracing a wide variety of wartime transgressions”. (). |

| 7 | The endless grieving enacted in the film would thus have as its juridical equivalent the re-opening of one wound through another, the simultaneous “calling up,” as Kaplan puts it, of all the others through the one crime (). |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).