Silk Road Influences on the Art of Seals: A Study of the Song Yuan Huaya

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Study of Song Yuan Huaya

2.1. Definition: Xiaoxingyin, Huaya, and Yuanya—Song Yuan Huaya

2.2. Literature Review

3. Case Studies: The Characteristics of Song Yuan Huaya and the Silk Road Influences

The Silk Road was not a network of trade routes, or even a system of cultural exchange. It was the entire local political-economic-cultural system of Central Eurasia, in which commerce, whether internal or external, was very highly valued and energetically pursued—in that sense, the ‘Silk Road’ and ‘Central Eurasia’ are essentially two terms for the same thing.22

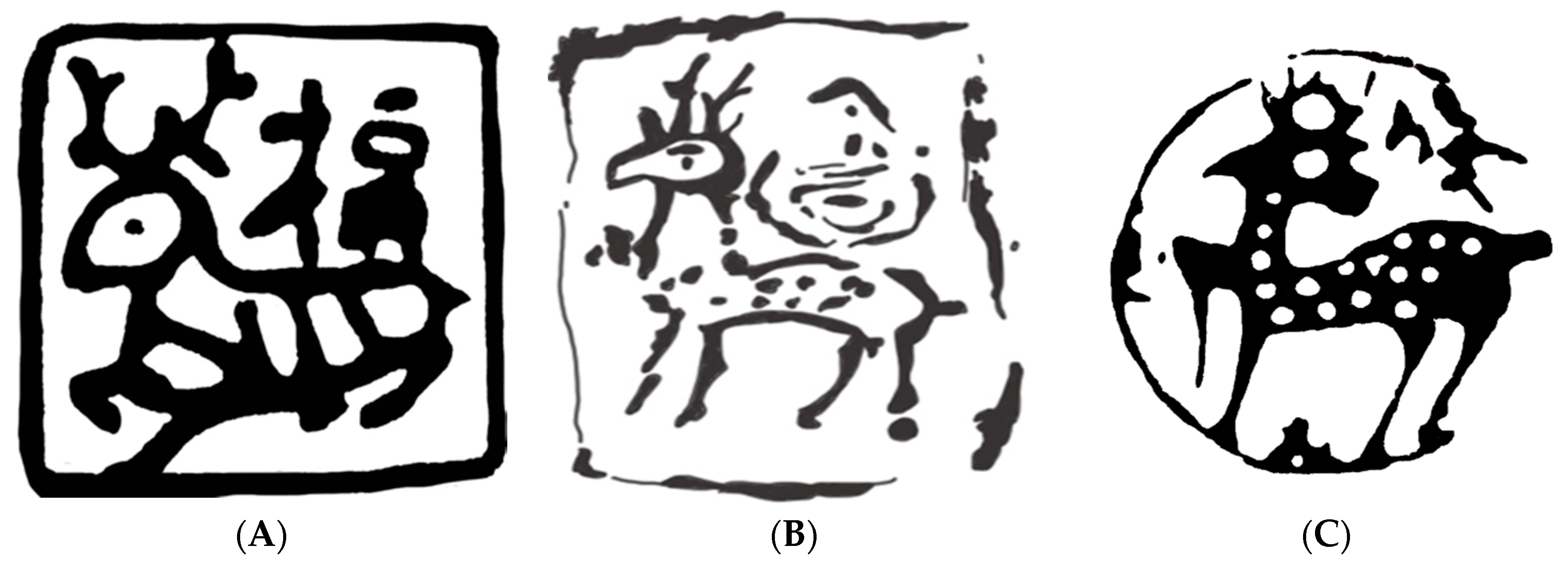

3.1. The Deer

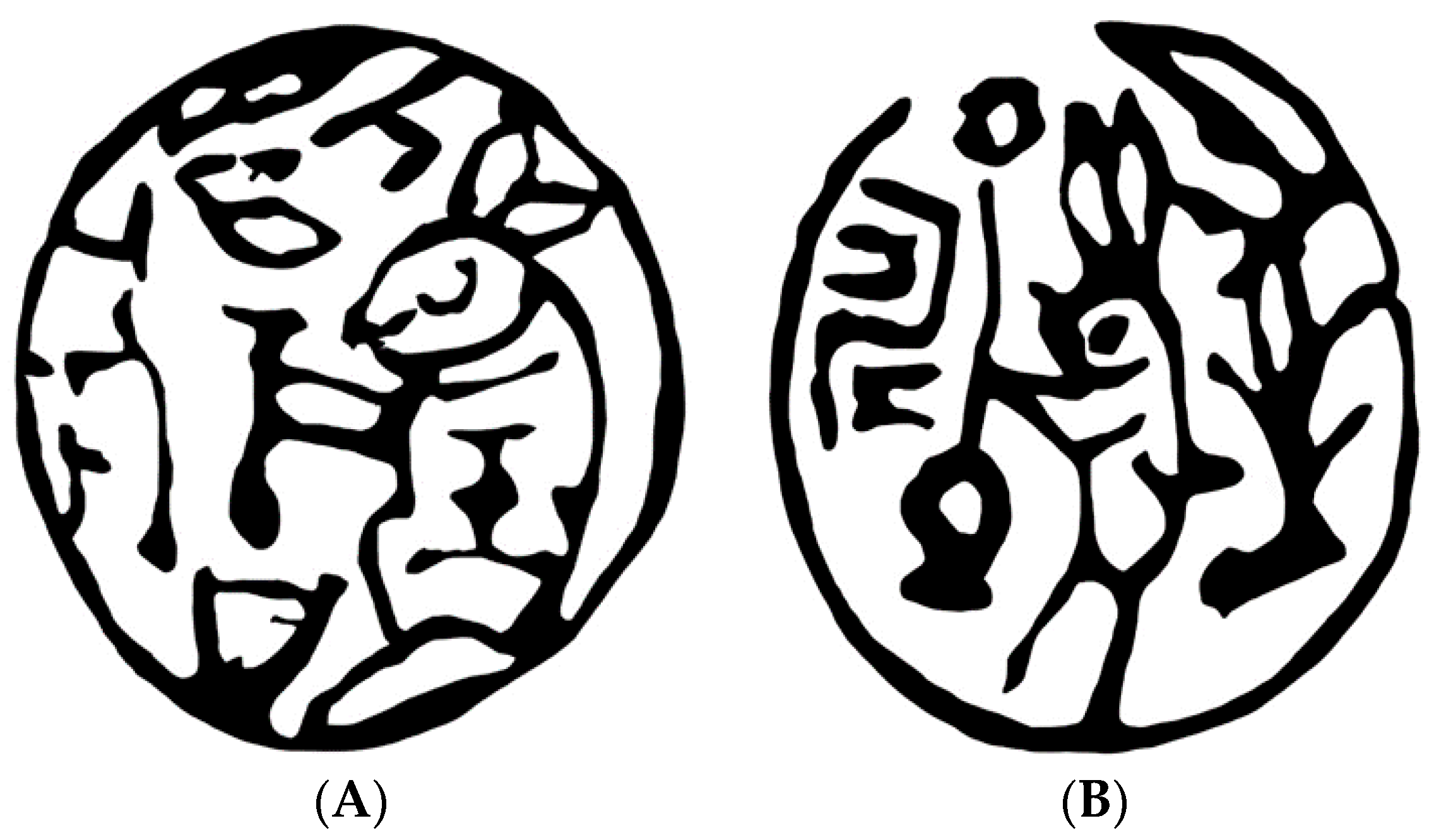

3.2. The Hare/Rabbit

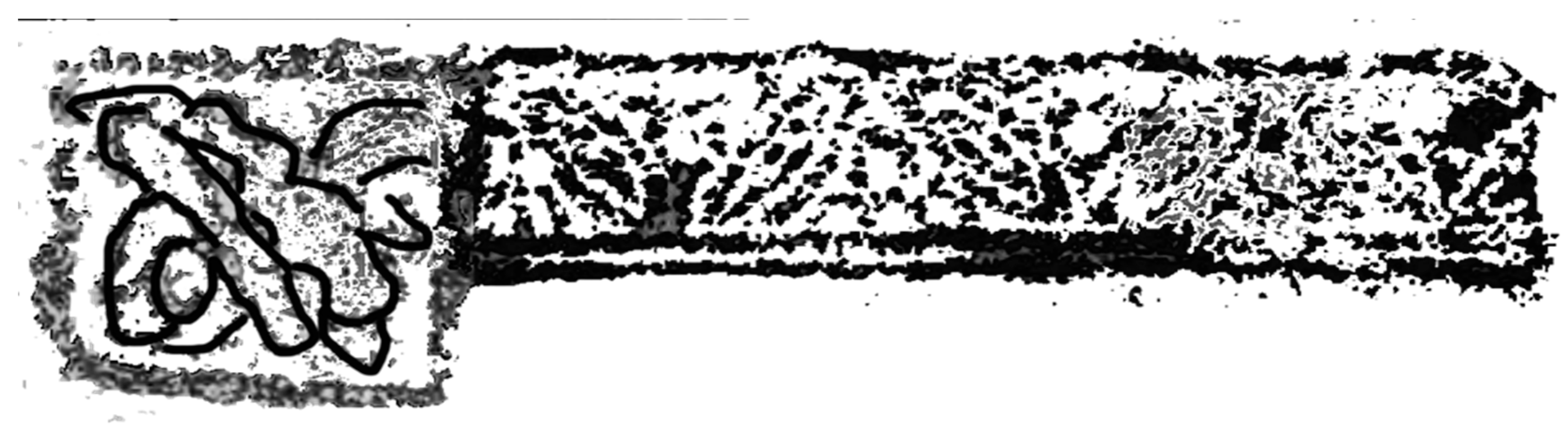

3.3. The Hu Pipa 胡琵琶

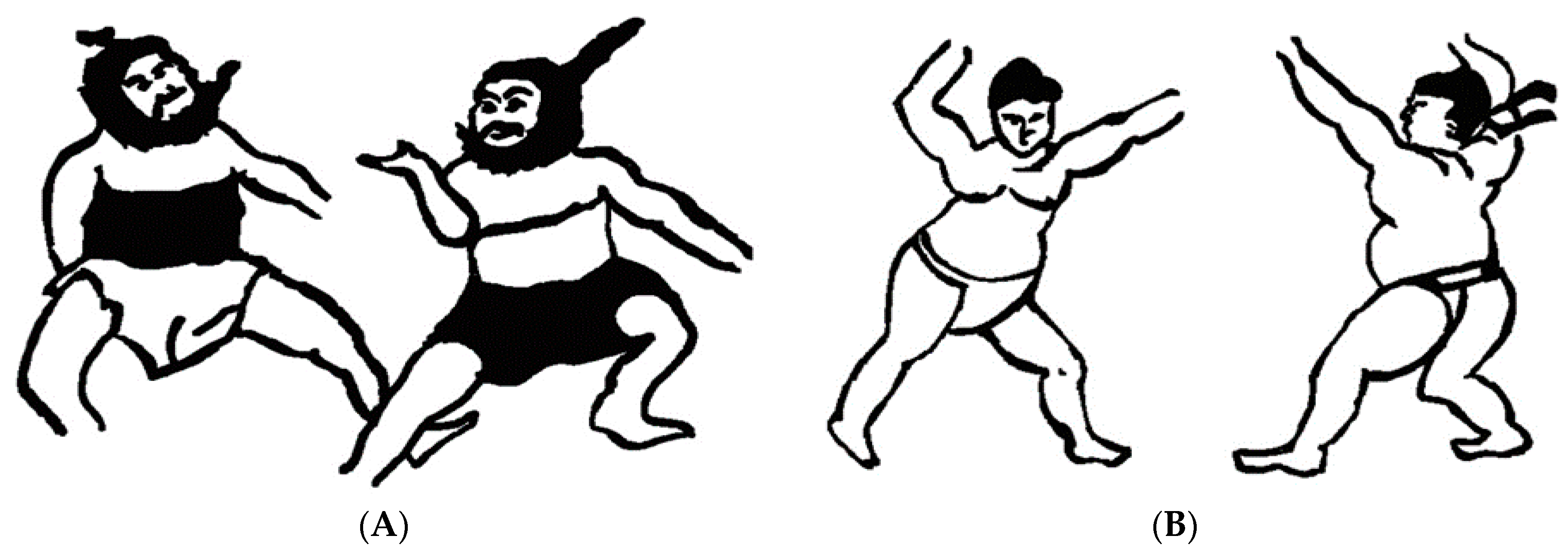

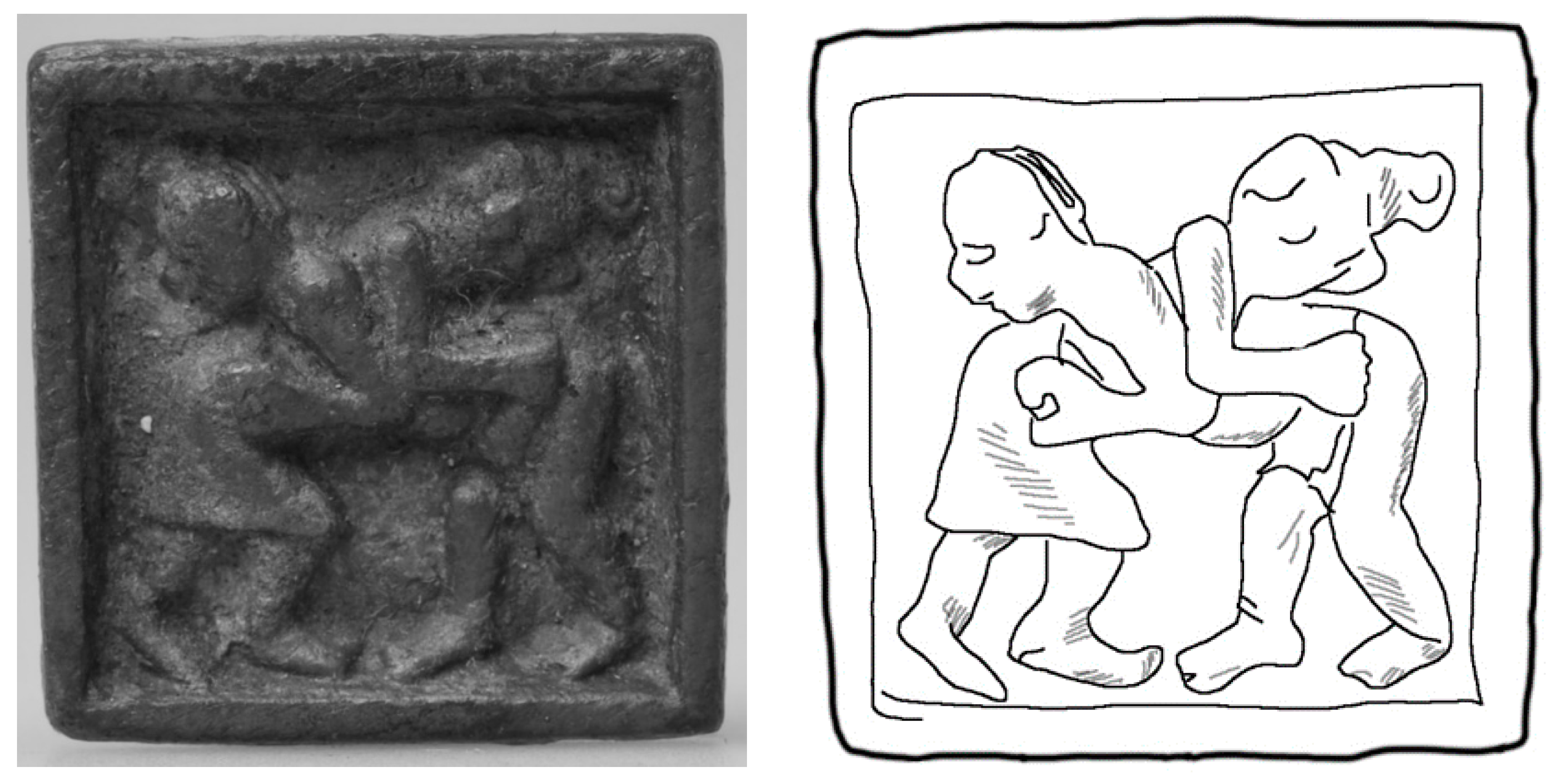

3.4. The Wrestling Scene

3.5. Some Ethnic Characters

,

,  , and

, and  refer to the same Jurchen character. Jin states:

refer to the same Jurchen character. Jin states:

In the third volume of Manzhou Jinshi Zhi 滿洲金石志, Luo, Fuyi 羅福頤 writes: “there is inscription carved on the edge of the Maoke mirror 毛克鏡 of Xianping Fu 咸平府 that: ‘This is officialof Xianping Fu.’” Besides, there is a round bronze seal excavated from the Zhongxing 中興 ancient city of Suibin 綏濱, near to Heilong Jiang river 黑龍江 (Figure 37, added by author), with the character

carved on the position traditionally interpreted to be the Chinese character Yin 印 (seals or stamps). Also, this

is seen on other edges of the mirrors, thus, it should be functionally similarly to the Chinese character “Feng 封”, “Ji”, etc., which are the common characters on seals. As for the accurate pronunciation and meaning of this character, more studies should be conducted on that.

was presented in a form

was presented in a form  , Jin explains that “it is the transformation form of

, Jin explains that “it is the transformation form of  ……in many bronze mirrors of the Jin dynasty, this character was commonly carved on the edge of the mirrors, yet in a very rudimentary way, and sometimes in the form of

……in many bronze mirrors of the Jin dynasty, this character was commonly carved on the edge of the mirrors, yet in a very rudimentary way, and sometimes in the form of  , or

, or  . They are actually the same character.”83

. They are actually the same character.”83 on it in the Shoujin 瘦金 script, could be among the earliest cases of that character (Figure 38). There is another character found on a stone seal there in the same tomb. It is a stone seal carved with a Chinese character “Lang 郎 (in this case a family name)”85 and a character

on it in the Shoujin 瘦金 script, could be among the earliest cases of that character (Figure 38). There is another character found on a stone seal there in the same tomb. It is a stone seal carved with a Chinese character “Lang 郎 (in this case a family name)”85 and a character  (Figure 39). One thing for sure that this is not the earliest case of

(Figure 39). One thing for sure that this is not the earliest case of  . There are some coins inscribed with four characters including

. There are some coins inscribed with four characters including  (Figure 40), mentioned by different scholars and dealers, which are dated to the Liao dynasty. Although the interpretation of the relevant characters is controversial, one thing is certain and that is that four of the characters are Khitan not Jurchen.

(Figure 40), mentioned by different scholars and dealers, which are dated to the Liao dynasty. Although the interpretation of the relevant characters is controversial, one thing is certain and that is that four of the characters are Khitan not Jurchen. resembles the Jurchen character

resembles the Jurchen character  , which is pronounced “Bai”, and hence sounds similarly to “Bao”.86 Fengzhu Liu provides another idea, that they should be read as “Tian Chao Wan Shun 天朝萬順”.87 Based on Liu’s account, Yuewang Wei suggests that the character concerned should be read as “Sui 歲”.88 Naixiong Chen questions all the above interpretations with good reason, and that leaves the meaning and pronunciation of the character undecided. I suggest that there is another clue which should be considered.

, which is pronounced “Bai”, and hence sounds similarly to “Bao”.86 Fengzhu Liu provides another idea, that they should be read as “Tian Chao Wan Shun 天朝萬順”.87 Based on Liu’s account, Yuewang Wei suggests that the character concerned should be read as “Sui 歲”.88 Naixiong Chen questions all the above interpretations with good reason, and that leaves the meaning and pronunciation of the character undecided. I suggest that there is another clue which should be considered. (Zheng) are located in the same spots where the Tian and

(Zheng) are located in the same spots where the Tian and  are on the abovementioned coins of four Khitan characters, and the shape of

are on the abovementioned coins of four Khitan characters, and the shape of  (Zheng) is very close to that of

(Zheng) is very close to that of  (Bao), only it seems to be written in abstract and cursive script rather than Shoujin style. If that is the case, then at least we can reach an inference that the tradition of using

(Bao), only it seems to be written in abstract and cursive script rather than Shoujin style. If that is the case, then at least we can reach an inference that the tradition of using  and

and  on seals started around 1161, and was retained among the nobles thereafter, finally making its way to the mainstream tradition of Song Yuan Huaya during the Yuan Dynasty. Since the meaning of

on seals started around 1161, and was retained among the nobles thereafter, finally making its way to the mainstream tradition of Song Yuan Huaya during the Yuan Dynasty. Since the meaning of  , although lacking accurate interpretation, is closely related to auspicious connotations (Fu, Bao, Bai, or Zheng), it is not surprising to see them thriving in Song Yuan Huaya, since with private seals, the appeal to auspicious significance is the most important.

, although lacking accurate interpretation, is closely related to auspicious connotations (Fu, Bao, Bai, or Zheng), it is not surprising to see them thriving in Song Yuan Huaya, since with private seals, the appeal to auspicious significance is the most important. , seen abundantly in Song Yuan Huaya, it is too early to decide on its meaning. However, according to its shape, it may have some relation to the character

, seen abundantly in Song Yuan Huaya, it is too early to decide on its meaning. However, according to its shape, it may have some relation to the character  . This character is pronounced “ta”, but its meaning remains unknown.90

. This character is pronounced “ta”, but its meaning remains unknown.90 , the other two characters in question seem possibly parallel with traditional Chinese seal signs “Ji” and “Ya” as mentioned above. Can we hypothesize that when the peoples in the later Song and the Yuan Dynasties developed the various Song Yuan Huaya trends, they borrowed ethnic elements in their simplest and hence most popular forms, making the borrowing of the elements more akin to a fashion than to a demand for strong and clear sematic expression, such as an identity declaration or differentiation?

, the other two characters in question seem possibly parallel with traditional Chinese seal signs “Ji” and “Ya” as mentioned above. Can we hypothesize that when the peoples in the later Song and the Yuan Dynasties developed the various Song Yuan Huaya trends, they borrowed ethnic elements in their simplest and hence most popular forms, making the borrowing of the elements more akin to a fashion than to a demand for strong and clear sematic expression, such as an identity declaration or differentiation?4. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ba, Gela. 2009. Shilun Xibei Youmu Wenhua De “Lushi” Xianxiang [試論西北遊牧文化的“鹿石”現象]. Journal of Educational Institute of Jilin Province 10: 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Xi Ling Yin She. 2003. Bainian Mingshe, Qianqiu Yinxue: Guoji Yinxue Yantaohui Lunwen Ji 《”百年名社・千秋印學”:國際印學研討會論文集》. Editorial Commitee Bainian Mingshe. Hangzhou: Xi Ling Yin She. [Google Scholar]

- Beckwith, Christopher I. 2009. Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bu, Jian. 2007. From Jiaodi to Baixi—On the Artistic Trend of Chinese Drama in the Period of Qin and Han Dynasties [從角抵到百戲—秦漢時期中國戲劇的藝術走向]. Xuzhou Institute of Technology 22: 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, Ketu. 2008. Bukh Yanjiu [搏克研究]. Sports Culture Guide 5: 81–83. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Naixiong. 1985. Guanyu Liaodai Qianbi Qidan Zi De Shidu Qingkuang [關於遼代錢幣契丹字的釋讀情況]. China Numismatics 4: 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Genyuan. 2013. Chen Genyuan Shuo Guyin (16) [陳根遠說古印 (十六)]. Arts in China 8: 78–79. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Jian Andrea. 2016. Investigation of the Idea of Nestorian Crosses—Based on F. A. Nixon’s Collection. Quest: Studies on Religion & Culture in Asia 2: 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Zhaohui, and Jie Pan. 2013. Heishuicheng Chutu Yuandai Wenshu Yayin Zhidu Chutan [《黑水城出土元代文书押印制度初探》]. Tangus Research 4: 84–87. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Lequan. 2003. History of Chinese Wrestling. China Sports 4: 118–19. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Yingxin. 1981. Tongwancheng Chengzhi Kance Ji [統萬城城址勘測記]. Archaeology 3: 225–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Shanqing. 1996. Yuanya Yinzhang De Jiancang Yu Fenlei [《元押印章的鑑藏與分類》]. Collectors 1: 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Tingliang. 1985. Hanyin Zhong Suojian De Tiyu Huodong [漢印中所見的體育活動]. Journal of Chengdu Sport University 1: 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Hui. 2004. Tongwan City—The Monument of National Cultural Exchange and the Testimony of Environmental Changes. In Tongwan City: Yizhi Zonghe Yanjiu [《統万城:遗址综合研究》]. Edited by the Northwest Institute of Historical Enviornment and Social-Economic Development of the Shanxi Normal University. Xi’an: Sanqin Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Jianzhong. 2009. Yongzheng Huangdi De Huaya [雍正皇帝的花押]. Beijing Archives 5: 49–51. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Zhanhong. 2006. Qianlun Handai Jiyu Yinzhang Daliang Liuxing De Gaikuang Ji Yuanyin [浅论汉代吉语印章大量流行的概况及原因]. Journal of Liaoning Institute of Technology (Social Science Edition) 8: 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Jiqin. 1992. Jinyuan Shiqi Qidan Ren Xingming Ynajiu [金元時期契丹人姓名研究]. Heilongjiang National Series 4: 106–10. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzhugh, William. 2017. Mongolian Deer Stones, European Menhirs, and Canadian Arctic Inuksuit: Collective Memory and the Function of Northern Monument Traditions. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 24: 149–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Yansheng. 2014. Mengguzu Bukh Yundong Shikao [蒙古族搏克運動史考]. Lantai World 3: 81–82. [Google Scholar]

- He, Tianming. 1991. Shitan Yuandai Nvzhen Yu Menggu De Guanxi [試探元代女真與蒙古的關系]. Heihe Journal 4: 104–8. [Google Scholar]

- Heilongjiang Provincial Archaeological Research Team. 1977. Heilongjiang Pan Suibin Zhongxing Gucheng He Jindai Muqun [黑龍江畔綏濱中興古城和金代墓群]. Cultural Relics 4: 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Chunyan. 2008. Menggu Zu Shuaijiao Fu [蒙古族摔跤服]. Journal of Inner Mongolia Normal University (Philosophy and Social Science) S3: 89–90. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Jingyan. 1985. Qidan Zi Qianbi Kao [契丹字錢幣考]. China Numismatics 4: 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Wenjing. 2010. Yuandai Wenren Yinzhang De Xingshi Fenxi (1)—Yuandai Zhuanke Fazhan De Sange Jieduan [元代文人印章的形式分析(上)—元代篆刻發展的三個階段]. An Analysis on Seal Form by Intellectual in the Yuan Dynasty: Three Step Development of Seal Carving in the Yuan Dynasty 9: 371–422. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Qizong. 1984. Nvzhenwen Cidian [《女真文辭典》]. Beijing: Cultural Relics Press. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jifang. 1983. Liao Jin Yuan Yi Jiaodi Wei Junshi Jishu Xianzhi Minjian Lianxi—Zhongguo Gudai Shuaijiao Shilue (2) [遼金元以角抵為軍事技術限制民間習練—中國古代摔跤史略(下二)]. Journal of Chengdu Physical Education Institute 4: 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jinhua. 1994. “Qin Pipa” and “Hu Pipa”—Zhongguo Gudai Pipa Kaobian [“秦琵琶”與“胡琵琶”—中國古代琵琶考辨]. Jiaoxiang-Journal of Xi’an Conservatory of Music 2: 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Zixuan. 2012. Hanyin Yishu (Second) [漢印藝術 (二)]. Calligraphy Magazine 10: 72–73. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Binguo. 1985. Cong Tiyu Wenwu Zhong Kan Woguo Gudai Shuaijiao De Fazhan [從體育文物中看我國古代摔跤的發展]. The Journal of Sport History and Culture 5: 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Wei. 2014. Yuandai Wushu Jinzhi De Yuanyin He Fenxi [元代武術禁止的原因和影響分析]. Lantai World 3: 93–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Zhijun, and You Zhang. 2008. Zhongguo Jiaodi Xi De Benti Fazhan Yu Lishi Yanjin [中國角抵戲的本體發展與歷史演進]. Dunhuang Research 4: 112–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, Hongli. 2005. Jinyuan Nvzhen Xingshi Pu Ji Gai Hanxing Zhi Fenlei Yu Tedian [金源女真姓氏譜及改漢姓之分類與特點]. Manchu Minority Research 4: 36–47. [Google Scholar]

- National Palace Museum. 1984. Gugongbowuyuan Cang Xiaoxingyin Xuan [《故宮博物院藏肖形印選》]. Edited by Qi-Feng Ye and The Editorial Office of Xiao-Xing-Yin of the National Palace Museum. Beijing: People’s Fine Arts Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, Shusen. 2003. Yuandai De Nvzhenren [元代的女真人]. Social Science Front Bimonthly 4: 161–64. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, Tamara Talbot. 1965. Ancient Arts of Central Asia. London: Thames and Hudson. [Google Scholar]

- Sha, Menghai. 1987. Yinxue Shi [《印学史》]. Hangzhou: Xiling Yinshe. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Yuanliang. 1995. Huaya Yinhui [《花押印匯》]. Shanghai: Shanghai Paintings and Calligraphy Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Weizu. 2004. Chinese Seals: Carving Authority and Creating History, 1st ed. San Francisco: Long River Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Weizu, Hao Li, and Zheng Luo. 2001. Tang Song Yuan Siyin Yaji Jicun [《唐宋元私印押記集存》]. Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Zongyi. 1997. Nancun Chuogeng Lu [《南村輟耕錄》]. Beijing: Chung Hwa Book Co., vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Jianping. 2003. Yuandai Chuban Shi [《元代出版史》]. Shijiazhuang: Hebei People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Tjalling, Halbertsma, and Jian Wei. 2005. Some Field Notes and Images of Stone Material from Graves of the Church of the East in Inner Mongolia, China. Monumenta Serica 53: 113–244. [Google Scholar]

- Tomikawa, Rikido. 2006. Mongolian Wrestling (Bukh) and Ethnicity. International Journal of Sport and Health Science 4: 103–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Fangyu. 1981. Bada Shanren De Huaya [八大山人的畫押]. Cultural Relics 6: 78–81. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Bomin. 1983. Gu Xiaoxingyin Yishi [《古肖形印臆釋》]. Shanghai: Shanghai Paintings and Calligraphy Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Hanzhang, ed. 1990. Shaan Xi Chu Tu Li Dai Xi Yin Xuan Bian [《陝西出土歷代璽印選編》]. Xi’an: Sanqin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Min. 2013. Lianzhuwen Yuanliu Jiqi Zai Xinjiang Shaoshu Minzu Zhuangshi Zhong De Yunyong [連珠紋源流及其在新疆少數民族裝飾中的運用]. Creation and Design 5: 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Youji, and Lianzhen Ma. 2009. A Brief Discussion on “Jiaodi” and “Shoubo” [“角抵”與“手搏”略論]. Wushu Science 11: 25–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Yuewang. 1984. Liaoqian Tu Lu [遼錢圖錄]. China Numismatics 1: 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Jinlong. 2004. Zhongguo Gudai Shuaijiao Yundong Fazhan Shulue [中國古代摔跤運動發展述略]. Journal of Yanan University (Social Science Edition) 26: 93–94. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Tingkuan. 1995. Zhongguo Xiaoxingyin Daquan [《中國肖形印大全》]. Taiyuan: Shanxi Classic Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Luan. 1991. Liao “Tianzheng” Qian Buzheng [遼“天正”錢補證]. Inner Mongolia Social Sciences 4: 73–75. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Rui, and Run-Hu Wang. 2008. Luelun Wudai Yilai Lushang Sichou Zhilu De Jidian Bianhua [略論五代以來陸上絲綢之路上的幾點變化]. Social Sciences in Ningxia 6: 148–51. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Mengde, and Shaoyi Yuwen. 1983. Shilin Yan Yu [《石林燕語》]. Taibei: The Commercial Press, vol. 863. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiyoki, Funada. 2003. Semuren Yu Yuandai Zhidu, Shehui—Chongxin Tantao Menggu, Semu, Hanren, Nanren Huafen De Weizhi [色目人與元代制度、社會—重新探討蒙古、色目、漢人、南人劃分的位置]. Mongolian Studies Information 2: 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Tianshu. 1992. Zhejiang Ruian Chutu Qingci Baixi Duisu Ping [浙江瑞安出土青瓷百戲堆塑罐]. Southeast Culture 2: 48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Yuming. 2003. Xiaoxingyin [《肖形印》], 1st ed. Shanghai: Shanghai Paintings and Calligraphy Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Jinlong. 2016. Suidai Yuhong Zushu Ji Qi Xianjiao Xinyang Guankui [隋代虞弘族屬及其祆教信仰管窺]. Journal of Literature, History and Philosophy 2: 91–113. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Huanbin, and Zhongguo Yinyue Wenwu Dxi Editorial Committee. 1996a. Zhongguo Yinyue Wenwu Dxi—Shanghai Jiangsu Volume [《中國音樂文物大系—上海江蘇卷》]. Zhengzhou: Daxiang Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Huanbin, and Zhongguo Yinyue Wenwu Dxi Editorial Committee. 1996b. Zhongguo Yinyue Wenwu Dxi—Fujian Volume [《中國音樂文物大系—福建卷》]. Zhengzhou: Daxiang Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Weiping. 2003. Sichou Zhilu Shang De Pipa Yueqi Shi [絲綢之路上的琵琶樂器史]. Musicology in China 4: 34–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Changzhi. 2006. Zhongguo Zhuanke Shi [《中國篆刻史》], 1st ed. Edited by Zhu Zhu. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Jianxin, and Ben Liao. 2016. Shandong Linyi Jinque Shan 9 Hao Xihan Mu Bohua Jiaodi Changmian [山東臨沂金雀山9號西漢墓帛畫角抵場面]. Journal of College of Chinese Traditional Opera 3: 27. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Cong. 2006. Zhongguo Gudai Pipa De Xingzhi Kaobian [中國古代琵琶的形制考辨]. Music Life 8: 64–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Zuxiang. 2008. Song, Yuan, Ming Pipa Tuxiang Kao—Pipa Yueqi Hanhua Guocheng De Tuxiang Fenxi [宋、元、明琵琶圖像考—琶樂器漢化過程的圖像分析]. Musicology in Chia 4: 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Xiaolu. 2001. Yuan Ya: Zhongguo Gu Dai Zhuan Ke Yi Shu Qi Pa [《元押:中國古代篆刻藝術奇葩》]. Nanjing: Jiangsu Fine Arts Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Shuqin. 2017. Tangshi Zhong De Huji Yuewu Yu Tangdai Xiyu Yueqi [唐詩中的胡姬樂舞與唐代西域樂器]. Xinjiang Art 6: 122–33. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | |

| 2 | Ibid., p. 21. |

| 3 | Ibid. |

| 4 | Some scholars argue that the names “Ya” “Yin” and “Xi” refer to different seals/stamps used by different social classes. See (Sun 2004, p. 11). This clear-cut definition is also questioned by many in the field. For the sake of relevancy, this paper will focus on the common meaning shared by all three terms, that is, referring to the seals and their imprints/signatures, instead of their controversial differences. |

| 5 | Xiaoxingyin, as a term in this discussion, is a relatively modern adoption. Some scholars categorize all the seals with dominant pictorial and figurative designs as belonging to the group of Xiaoxingyin. For the definition of Xiaoxingyin of this kind, see (Wen 1995, p. 1; Wang 1983, p. 1; Zhang 2003, pp. 1–2; National Palace Museum 1984, preface). |

| 6 | Some would argue that the tradition of Song Yuan Huaya starts in the Tang Dynasty (618–970 CE) instead of the Song dynasty. However, this categorization usually does not separate seals from their imprints. Moreover, the unique style of Song Yuan Huaya was not seen among the Tang imprints. In order to address Song Yuan Huaya as a seal genre with unique characteristic and social context, this paper will follow the mainstream view on this issue. |

| 7 | |

| 8 | Some scholars argue that the literati seal genre starts with the famous calligrapher’s home-made seals. Mifu 米芾, who was active during the North Song Dynasty, is thus considered as the predecessor of that genre. See (Jiang 2010, p. 383). |

| 9 | Tingkuan Wen mentions that “in the existing works about the ancient imprint books and the Chinese seals, Xiaoxingyin usually was excluded from the works and attributed to the category of ‘others’ (Za Yin 雜印), or even denied as proper seals because of its lack of Chinese characters”. In another word, there is a criterion in the existing studies set up to distinguish the “proper seals” from the rest, to build up a so-called canon of Chinese seals. See (Wen 1995, p. 1). |

| 10 | For examples, see (ibid.; Shi 1995; National Palace Museum 1984). |

| 11 | For example, the earliest record of non-calligraphic seals is in a Yinpu of the Ming Dynasty: Fanshi Jigu Yinpu (範氏集古印譜) under the description of “depiction of bird and insects, unidentifiable as the family name signature”. Gugongbowuyuan Cang Xiaoxingyin Xuan [《故宮博物院藏肖形印選》], Conclusion. |

| 12 | Although the book takes the name “Yuanya”, it states clearly that Yuanya is a genre of seals with distinctive artistic traits, but not restricted to the Yuan dynasty (Zhou 2001, p. 2). |

| 13 | Ibid. |

| 14 | Ibid. |

| 15 | |

| 16 | |

| 17 | Shi, Huaya Yinhui [《花押印匯》]. |

| 18 | |

| 19 | |

| 20 | (Tian 2003). |

| 21 | |

| 22 | Ibid. |

| 23 | There is more than one route that are considered to be attributed to the Silk Road cultural complex in the eastern Asia area. The expanding of the Mongolian political power, as mentioned in this paper earlier, has connected the routes of the Central Asia to the far east of China via the Steppe routes. Yet this paper does not intend to discuss the routes and their inter-relationship, instead, this paper is focusing on presenting the different cultural elements found on the Song Yuan Huaya to, hopefully, represent the material culture under cross-cultural influences in the concerned periods, and hence to form a new horizon for further studies. |

| 24 | Ibid. |

| 25 | |

| 26 | “唐人初未有押字,但草書其名,以為私記,故號花書.” (Ye and Yuwen 1983, p. 109). |

| 27 | Even emperor Yongzheng 雍正皇帝 has his own personal Ya, see (Dong 2009, p. 49). Bada Shanren 八大山人, who are the representatives of literati artists in the Qing dynasty, have their own Huaya as well. See (Wang 1981). |

| 28 | It is commonly assumed that the Yuan government divides the people into four ethnic groups: the Mongols, Semuren, Hanren 漢人 and Nanren 南人. Yet, simple definition of each terms is not appropriate. For example, the term “Hanren” also includes people of non-Han origin, and “Semuren” does not literally mean “people with colored eyes”. In that sense, Yoshiyoki gives a defition of Semuren that it refers to “the people except Mongols, Hanren and Nanren,” and its epytology is from the phrase:”Ge Se Mu Ren 各色目人 (all categories of people)”. See (Yoshiyoki 2003, p. 7). Since the discussion of the detailed defintion of Semuren falls out of the focus of this paper, we only need to know that, at the current stage, Ming schoalrs as mentioned here attribut the origin of Huaya to a postulated situation of the people of non-Han ethnicity. |

| 29 | |

| 30 | |

| 31 | The tradition of Jiyuyin starts earlier during the Pre-Qin period (before 221 BC), and reaches its zenith during the Han dynasty (202 BC–220 CE). See (Fang 2006). |

| 32 | |

| 33 | |

| 34 | |

| 35 | In Chinese art history, the art of the Qin 秦Dynasty (221–206 BC) and the art of the Han Dynasty are seen as belonging to the same tradition because of their consistency. It is especially so in Chinese Seal history. Out of the same reason, the seals from the above mentioned periods, even including the earlier periods such as the Warrior State period, usually bear the name: Qinhan Yinzhang 秦漢印章 (Qin-Han seals). |

| 36 | Although there are cases among Ming Qing Huaya adopting Phagspa characters to try to model after the Yuan antique, the overall artistic style of the Ming Qing Huaya is very different from those of the Yuan Dynasty. Thus, taking Phagspa character as the diagnostic feature for identification must integrate with other identification methods, such as the examination of the artistic style. |

| 37 | |

| 38 | |

| 39 | |

| 40 | This piece is from the book (Wen 1995, p. 150). |

| 41 | Ibid., p. 23. |

| 42 | |

| 43 | |

| 44 | Ibid. |

| 45 | |

| 46 | |

| 47 | (Rice 1965, p. 167), and also: (Wang 2013, p. 67). |

| 48 | |

| 49 | Ibid. |

| 50 | (Li 1994, p. 9). It is noteworthy that some scholars would go further to differentiate two forms of Hu Pipa, by calling the Pipa with the straight neck and five strings Hu Pipa, and the other form the “Pipa of crooked neck and four strings”, as can be seen in (Zhao 2003, pp. 34–35). However, since both were introduced to China via the Silk Road, one from Persia and the other from India, for the sake of succinctness, I will use the name “Hu Pipa” for both, unless there is need for a specific description, for example, in the analysis of their shapes. |

| 51 | |

| 52 | |

| 53 | |

| 54 | |

| 55 | Ibid., p. 37. |

| 56 | |

| 57 | It should be mentioned here that only one piece of straight-necked Pipa has a vertical line on its neck, which, according to the principle of the highly decorative style of Song Yuan Huaya, could have represented the frets. Yet, due to the uncertainty, this piece will not be formally included here. The lower part of this particular piece is inscribed with a Chinese character in a refined calligraphic style (perhaps Xingshu 行書), although not the Kaishu 楷書 style. Kaishu is the most popular calligraphic style that Song Yuan Huaya employs besides the Phagspa. Picture of this piece see: (Wen 1995, p. 437), number of 1877. |

| 58 | Although there is one questionable case found in the book, Xiaoxingyin Daquan 肖形印大全, I would not consider that case correlated because the most featured elements, such as the pegboard, peg, trident-shaped head, which are shared by all the other Pipa pieces, are missing in this case. In that sense, it should be legitimate to conjecture that this case may refer to something else, for example, a vase or a leather bag, since those also are popular themes among Song Yuan Huaya. |

| 59 | |

| 60 | Ibid. |

| 61 | |

| 62 | |

| 63 | |

| 64 | |

| 65 | |

| 66 | “引壯士裸袒相搏較力, 以分勝負.” (Wei 2004, p. 94). |

| 67 | There is one possible depiction of Jiaodi showing three figures wearing long-sleeved gowns and hats of the most typical style of the Han Dynasty, yet the identification of that piece as a depiction of Jiaodi seems inadequate for now. On the other hand, even there is Jiaodi costume with hat and gown during the Han Dynasty, the style of which is overtly different from the costumes of Bukh activity, and hence the piece mentioned does not sabotage the current argumentation. For the abovementioned depiction, see (Zhao and Liao 2016). |

| 68 | |

| 69 | |

| 70 | |

| 71 | |

| 72 | |

| 73 | Ibid. |

| 74 | Ibid. |

| 75 | |

| 76 | |

| 77 | Ibid. |

| 78 | |

| 79 | This naming is adopted by mainstream study of the so-called Yuanya, see (Xi Ling Yin She 2003, p. 114). |

| 80 | |

| 81 | |

| 82 | |

| 83 | Ibid., p. 60. |

| 84 | |

| 85 | In the Jin Dynasty, some Jurchen families would take up a Han character as the transcript of their family name. Lang is the transcript for the Jurchen Nvxilie女奚烈family. Similarly, the most famous family name in Jurchen is Wanyan 完顏, and the transcript of Wanyan in Chinese is Wang (the King) 王. See (Mu 2005, p. 41). It is noteworthy that during the Jin and Yuan dynasties, there were many Khitan families taking up the Chinese character Wang as their family name also. See (Feng 1992, p. 109). |

| 86 | |

| 87 | |

| 88 | (Chen 1985 ) |

| 89 | |

| 90 | |

| 91 | According to some research, although there was an anti-Sinicization policy executed during the Jin dynasty, the Sinicization inclination among peoples during that time never really ceased. Many Jurchen and Khitan people, including the nobles, have their Chinese names for various reason. See (Feng 1992, pp. 108–9; Mu 2005, p. 41). |

| 92 | |

| 93 | |

| 94 | |

| 95 | Chen, “Investigation of the Idea of Nestorian Crosses—Based on F. A. Nixon’s Collection.” |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, A.J. Silk Road Influences on the Art of Seals: A Study of the Song Yuan Huaya. Humanities 2018, 7, 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7030083

Chen AJ. Silk Road Influences on the Art of Seals: A Study of the Song Yuan Huaya. Humanities. 2018; 7(3):83. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7030083

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Andrea Jian. 2018. "Silk Road Influences on the Art of Seals: A Study of the Song Yuan Huaya" Humanities 7, no. 3: 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7030083

APA StyleChen, A. J. (2018). Silk Road Influences on the Art of Seals: A Study of the Song Yuan Huaya. Humanities, 7(3), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7030083