Re-Framing Hottentot: Liberating Black Female Sexuality from the Mammy/Hottentot Bind

Abstract

:1. Introduction

“There were so many jokes about the Black body; so many stereotypes that were whispered, passed around and perpetuated …. The Black body had its own mythology; it had its own language”

2. Denial of Black Female Sexuality

3. The Mammification of Black Women

4. The Deviant and Hypersexual Other: The Venus Hottentot

5. Long Dark Shadow of the Venus Hottentot

6. Re-Viewing Venus Hottentot

7. Re-Envisioning Hottentot in Black Photography

8. Black Sexuality Studies

9. Female Desire, Pleasure, and Alternate Radical Traditions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alexander, Elizabeth. 1990. The Venus Hottentot (1825). In The Venus Hottentot Poems. Minnesota: Graywolf Press, pp. 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, Elizabeth. 2009. "Reading" the Black Body: Or, Considering My Grandmother’s Hair. In The Black Body. Edited by Meri Nana-Ama Danquah. New York: Seven Stories Press, pp. 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bernier, Celeste-Marie. 2008. African American Visual Arts. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bobel, Chris. 2007. Women’s Sexuality: Discovering the Clitoris. In Gendered Bodies: Feminist Perspectives. Edited by Judith Lorber. Los Angeles: Roxbury. [Google Scholar]

- Carby, Hazel V. 1999. The Sexual Politics of Black Women’s Blues. In Cultures in Babylon: Black Britain and African America. New York: Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, Stokely, and Charles V. Hamilton. 1967. Black Power: The Politics of Liberation in America. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Chicago, Judy. 1974–1979. The Dinner Party. Ceramic, Porcelain, Textile. New York: Brooklyn Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 2000. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Lisa Gail. 2002. The Art of History: African American Women Artists Engage the Past. London: Rutgers. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, Renee. 1990. A Gynecentric Aesthetic. Hypatia, Feminism and Aesthetics 5: 43–62. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3810155 (accessed on 7 June 2019). [CrossRef]

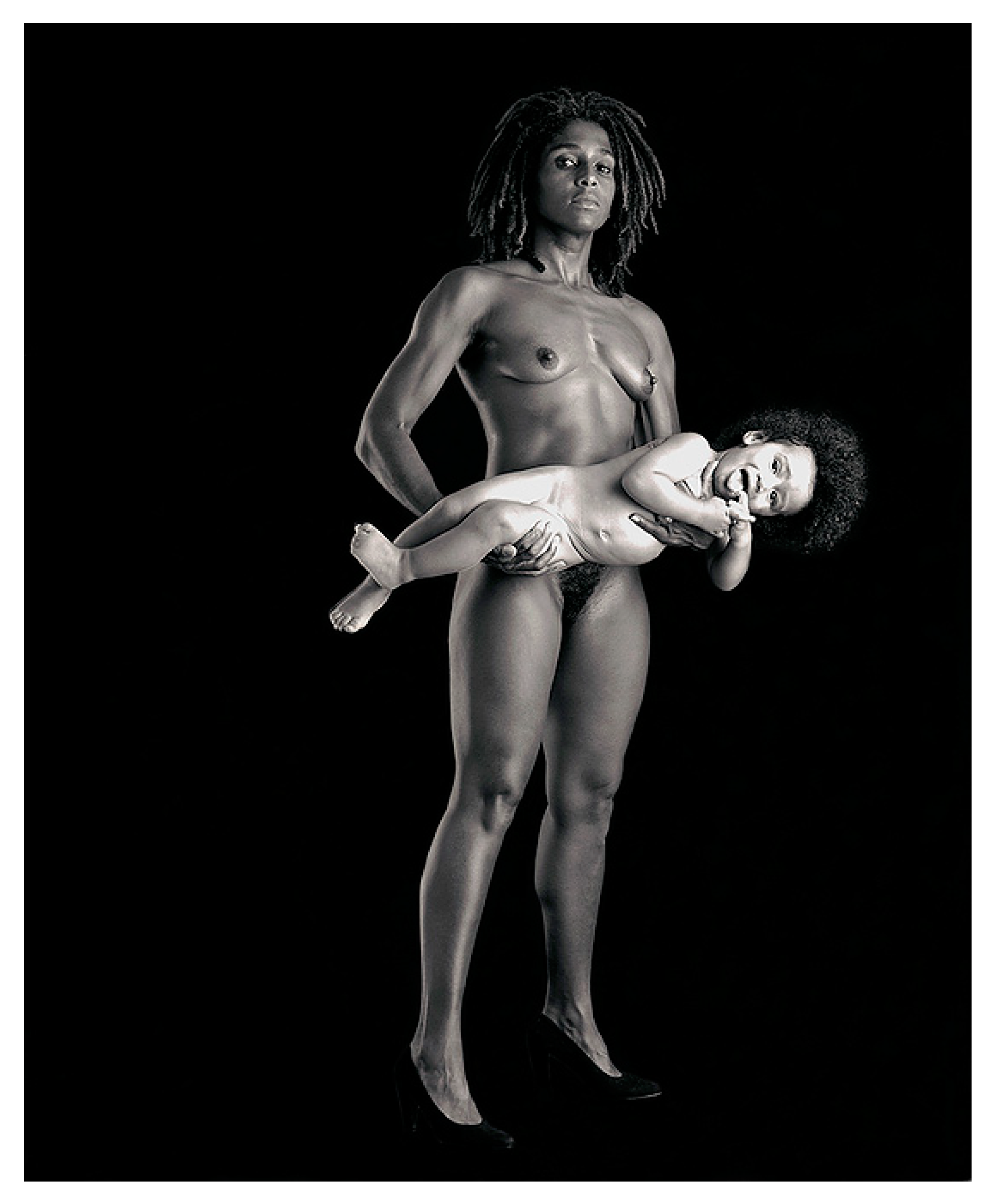

- Cox, Renee. 1992. Yo Mama at Home. Digital Ink Jet Print on Cotton Rag. Available online: https://www.reneecox.org/yo-mama?lightbox=i11c4n (accessed on 17 July 2019).

- Cox, Renee. 1993. Yo Mama. Digital Ink Jet Print on Cotton Rag. Available online: https://www.reneecox.org/yo-mama?lightbox=i21sj9 (accessed on 17 July 2019).

- Cox, Renee. 1994. Hot-En-Tott. Photograph. Available online: https://www.reneecox.org/hottentot-venus (accessed on 17 July 2019).

- Cox, Renee. 1996. Yo Mama The Sequel. Digital Ink Jet Print on Cotton Rag. Available online: https://www.reneecox.org/yo-mama?lightbox=i31hmp (accessed on 17 July 2019).

- Cox, Renee, and Lyle Ashton Harris. 1994. Venus Hottentot 2000. Available online: https://www.lyleashtonharris.com/series/the-good-life-2/ (accessed on 17 July 2019).

- Danquah, Meri Nana-Ama. 2009. Introduction: Body Language. In The Black Body. New York: Seven Stories Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Maria del Guadalupe. 2017. Black Women, Agency, and the New Black Feminism. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dent, Gina. 1992. Black Pleasure, Black Joy: An Introduction. In Black Popular Culture: A Project by Michele Wallace. Edited by Gina Dent. Seattle: Bay Press, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Diawara, Manthia. 1988. Black Spectatorship: Problems of Identification and Resistance. Screen 29: 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diawara, Manthia. 1990. Black British Cinema: Spectatorship and Identity Formation in Territories. Public Culture 3: 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, Lisa E. 2003. Reinventing Herself: The Black Female Nude. Woman’s Art Journal 24: 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, Lisa E. 2005. Creating Their Own Image: The History of African American Women Artists. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington, Lisa E. 2017. African American Art: A Visual and Cultural History. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. 2010. Elizabeth Alexander. In Faces of America: How 12 Extraordinary People Discovered Their Pasts. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilman, Sander L. 2003. Black Bodies, White Bodies: Toward an Iconography of Female Sexuality in Late Nineteenth-Century Art, Medicine, and Literature. In The Feminism and Visual Culture Reader. Edited by Amelia Jones. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Chipembere, Natasha. 2011. Introduction: Claiming Sarah Baartman, a Legacy to Grasp 2011. In Representation and Black Womanhood: The Legacy of Sarah Baartman. Edited by Natasha Gordon-Chipembere. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Hammonds, Evelynn. 1994. Black (W)Holes and the Geometry of Black Female Sexuality. Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 6: 126–45. [Google Scholar]

- Hammonds, Evelynn. 1997. Toward a Genealogy of Black Female Sexuality: The Problematic of Silence. In Feminist Genealogies, Colonial Legacies, Democratic Futures. Edited by Jacqui Alexander and Chandra Talpade Mohanty. New York: Routledge, pp. 170–82. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Lyle Ashton. 1995. Mirage: Enigmas of Race, Difference and Desire. London: ICA. [Google Scholar]

- Hobson, Janell. 2005. Venus in the Dark: Blackness and Beauty in Popular Culture. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- hooks, bell. 1981. Continued Devaluation of Black Womanhood. In Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism. Boston: South End Press, pp. 51–86. [Google Scholar]

- hooks, bell. 1989. Talking back. In Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black. Boston: South End Press, pp. 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- hooks, bell. 1990. Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness. In Yearnings: Race, Gender and Cultural Politics. Boston: South End Press, pp. 145–53. [Google Scholar]

- hooks, bell. 1992. The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators. In Black Looks: Race and Representation. Boston: South End Press, pp. 115–31. [Google Scholar]

- hooks, bell. 2017. Tough Love with bell hooks Interview by Abigail Bereola. Available online: https://www.shondaland.com/inspire/books/a14418770/tough-love-with-bell-hooks/ (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- King, Deborah K. 1988. Multiple Jeopardy, Multiple Consciousness: The Context of a Black Feminist Ideology. Signs 14: 42–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Shayne. 2010. Erotic Revolutionaries: Black Women, Sexuality, and Popular Culture. Lanham: Hamilton Books. [Google Scholar]

- Les Curieux en extase ou les cordons de souliers. 1814. French Print: Available online: https://whgbetc.com/mind/hot-venus.jpg (accessed on 8 April 2019).

- Lorde, Audre. 1984. Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power. In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. New York: The Crossing Press. [Google Scholar]

- Magubane, Zine. 2001. Which Bodies Matter?: Feminism, Post Structuralism, Race, and the Curious Theoretical Odyssey of the “Hottentot Venus”. Gender and Society 15: 816–34. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3081904 (accessed on 12 August 2019). [CrossRef]

- Mookerjee, Rita. 2019. Sex. In The Bloomsbury Handbook of 21st-Century Feminist Theory. Edited by Robin Truth Goodman. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 109–20. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, Thylias. 1998. Tale of a Sky Blue Dress. New York: Avon. [Google Scholar]

- Nanda, Shaweta. 2014. Re-Claiming the Mammy: Racial, Sexual and Class Politics Behind ‘Mammification’ of Black Women. In Discoursing Minority: In-Text and Co-Text. Edited by Anisur Rahman, Supriya Agarwal and Bhumika Sharma. New Delhi: Rawat Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Nochlin, Linda. 1971. Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? In Women, Art, and Power and Other Essays, 1st ed. London: Routledge, pp. 145–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Grady, Lorraine. 1994. Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity. Available online: http://lorraineogrady.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Lorraine-OGrady_Olympias-Maid-Reclaiming-Black-Female-Subjectivity1.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2019).

- Okediji, Moyo. 2006. Colored Pictures: Race & Visual Representation. Edited by Michael D. Harris. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, Joel. 2004. The Abolition of White Democracy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Parks, Suzan-Lori. 1996. The Rear End Exists. Grand Street 55: 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, Stacey. 2012. Who’s Afraid of Black Sexuality? The Chronicle of Higher Education. December 3. Available online: https://www.chronicle.com/article/Whos-Afraid-of-Black/135960 (accessed on 7 May 2019).

- Pereira, Malin. 2007. The Poet in the World, the World in the Poet: Cyrus Cassells’s and Elizabeth Alexander’s Versions of Post-Soul Cosmopolitanism. African American Review 41: 709–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, Malin. 2010. Into a Light Both Brilliant and Unseen: Conversations with Contemporary Black Poets. London: University of Georgia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phillip, Christine, and Elizabeth Alexander. 1996. An Interview with Elizabeth Alexander. Callaloo 19: 493–507. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3299216 (accessed on 26 May 2019).

- Pilgrim, David. 2012. The Jezebel Stereotype. Available online: https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/jezebel/index.htm (accessed on 17 July 2019).

- Qureshi, Sadiah. 2004. Displaying Sara Baartman, the ‘Hottentot Venus. History of Science 42: 233–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scully, Pamela, and Clifton Crais. 2008. Race and Erasure: Sara Baartman and Hendrik Cesars in Cape Town and London. Journal of British Studies 47: 301–23. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25482758 (accessed on 10 August 2019). [CrossRef]

- Sharpley-Whiting, T. Denean. 1990. Black Venus: Sexualized Savages, Primal Fears, and Primitive Narratives in French. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, Debra S. 2010. Reclaiming Venus: The Presence of Sarah Bartmann in Contemporary Art. In Black Venus 2010: They Called Her “Hottentot”. Edited by Deborah Willis. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, Carol. 1980. Reading the Language of ‘The Dinner Party. Woman’s Art Journal 1: 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillers, Hortense. 1984. Interstices: A Small Drama of Words. In Pleasure and Danger. Edited by Carol S. Vance. Boston: Routledge & K. Paul, pp. 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- Spiller, Hortense. 2003. Introduction: Eating Peter’s Pan: Eating in Diaspora. In Black, White and in Colour: Essays on American Literature and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tesfagiorgis, Freida High W. 1993. In Search of a Discourse and Critiques That Centre the Art of Black Women Artists. In Theorizing Black Feminisms: The Visionary Pragmatism of Black Women. Edited by Abena P. A. Busia and Stanlie M. James. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Lisa B. 2012. Beyond the Black Lady: Sexuality and New African American Middle Class. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Alice. 1982. The Color Purple. London: Phoenix. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Alice. 1983. One Child of One’s Own: A Meaningful Digression within the Work(s). In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose. New York: Hardcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, Alice. 1992. Possessing the Secret of Joy. New York: Pocket Books. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, Michele. 1992. Afterword: Why Are There No Great Black Artists? The Problem of Visual in African American Culture. In Black Popular Culture: A Project by Michele Wallace. Edited by Gina Dent. Seattle: Bay Press, pp. 333–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, Michele. 2004. Black Women in Popular Culture: From Stereotype to Heroine. In Dark Designs & Visual Culture. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walters, Wendy W. 2010. Elizabeth Alexander’s Amistad: Reading the Black History Poem through the Archive. Callaloo 33: 1041–58. [Google Scholar]

- Weems, Carrie Mae. 1987–1988. Mirror Mirror. Ain’tJokin. Photographic Series. Available online: http://carriemaeweems.net/galleries/aint-jokin.html (accessed on 16 August 2019).

- White, Artress Bethany. 1998. Fragmented Souls: Call and Response with Renee Cox. In Soul: Black Power Politics and Pleasure. Edited by Monique Guillory and Richard C. Green. New York: New York University Press, Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qfg2m (accessed on 1 June 2019).

- Willis, Deborah. 2010. Introduction. In Black Venus 2010: They Called Her “Hottentot”. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Judith. 1992. Getting Down to Get Over: Romare Bearden’s Use of Pornography and the Problem of the Black Female Body in Afro-U.S. Art. In Black Popular Culture: A Project by Michele Wallace. Edited by Gina Dent. Seattle: Bay Press, pp. 112–22. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The given quotation has been taken from “Body Language” in The Black Body (14). |

| 2 | Following Joel Olson’s lead I have capitalized ‘B’ while writing Black but refrained from capitalizing ‘w’ while writing white. Olson explains the choice by stressing, “…the two terms are not symmetrical. Black is a cultural identity as well as a political category, and as such merits capitalization like American Indian, Chicana, or Irish American. White, however, … is strictly a political category and thus, like “proletarian,” “citizen,” or feminist, requires no capitalization” (Olson 2004, p. xix). |

| 3 | Lisa B. Thompson cites Michele Wallace in the epilogue of her book, Beyond the Black Lady: Sexuality and the New African American Middle Class (Thompson 2012, p. 139) while discussing the relevance of unearthing Black women’s sexual histories and desires. |

| 4 | Steatopygia is a medical term for protruding posterior which is termed disabling and aberrant in the white medical discourse. |

| 5 | The work was created with the intention of retrieving, celebrating and commemorating the history and achievements of women that have been obliterated by the dominant hetero-patriarchal culture. Chicago challenged the hegemony of the patriarchal world of art by according primacy to art forms like ceramics and needlework which were not considered works of ‘high art’ and are usually associated with women. |

| 6 | Alice Walker is deeply critical of the fact that Patricia Meyer Spacks in her book, The Female Imagination (1975) deals only with women in “the Anglo-American tradition” that is white middle-class women and makes no reference to the literary tradition and works of Black women. |

| 7 | For the visual, see https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/dinner_party/place_settings/sojourner_truth. |

| 8 | Alice Walker critiques Sojourner Truth’s representation by Judy Chicago. She describes the three faces in detail: “One, weeping (a truly cliché tear), which “personifies” the Black woman’s “oppression,” and another, screaming (a no less cliché scream), with little ugly pointed teeth “her heroism,” and a third, in gim-cracky “African” design, smiling; as if the African woman, pre-American slavery, or even today, had no woes” (Walker 1983, p. 233). |

| 9 | Walker reasons that it is the Black woman’s children that white woman “resents” for they make her feel “guilty” (Walker 1983, p. 233). Instead of addressing issues such as poverty, racism, segregation and exploitation that plagues the lives of these Black children, white women choose to “deny that the Black woman has a vagina. Is capable of motherhood. Is a woman” (Walker 1983, p. 233). |

| 10 | These concerns are reflected succinctly in the title of a book, All the Women Are White, All the Blacks are Men, But Some of Us Are Brave (1982) that was co-edited by Gloria T. Hull, Patricia Bell Scott, and Barbara Smith. Also, for a detailed discussion of the history of Black women’s sexualities and their representation, see Evelynn Hammonds’s “Black (W)holes and the Geometry of Black female sexuality” (Hammonds 1994). |

| 11 | For visuals of salt shakers, notepads, advertisements and films that deploy the Mammy stereotype, see https://www.historyonthenet.com/authentichistory/diversity/african/1-mammy/. |

| 12 | For details see Shaweta Nanda’s article, Re-Claiming the Mammy: “Racial, Sexual and Class Politics Behind ‘Mammification’ of Black Women” (Nanda 2014). |

| 13 | I am following Natasha Gordon-Chipembere who in turn follows Pumla Dineo Gqola’s arguments about positioning Sara Baartman as a slave instead of an indentured worker despite the fact that legally or technically she is often considered to be free (Gordon-Chipembere 2011, p. 3). Rachel Holmes in African Queen: The Real Life of the Hottentot Venus also stresses that Sara Baartman was unfree in sexual, racial and economic terms. |

| 14 | Pamela Scully and Clifton Crais recount that Baartman was made to sing, walk and turn around on stage (freak show) in London where the spectators were free to poke her with their walking sticks (Scully and Crais 2008). As per the account of South African History Online’s article on Sara Baartman, she was displayed in a cage in London. For details see https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/sara-Saartjee-baartman. Later in 1814, when she was transported to France and sold to an animal trainer named S. Réaux, Baartman was again caged and displayed next to a baby rhinoceros. Thus, one could safely conclude that there were times when Baartman was made to perform on stage while at other times she was simply caged and put up on spectacle. Zine Magubane observes the difference between the manner in which Baartman was racialized in Britain and France. Regarding the display of Baartman’s almost naked body, Sadiah Qureshi contends that later in 1815 Baartman was made to pose nude for the first volume of Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire’s and Frédéric ’s Histoire naturelle des mammifères wherein she was the only human who featured next to the animals such as apes and monkeys (Qureshi 2004, p. 241). |

| 15 | Sara Baartman was exhibited for the first time at a show in Piccadilly in London in 1810. |

| 16 | I am indebted to T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting’s article, “Writing Sex, Writing Difference: Creating a Master Text on the Hottentot Venus” (Sharpley-Whiting 1990, pp. 17, 23) for this information. |

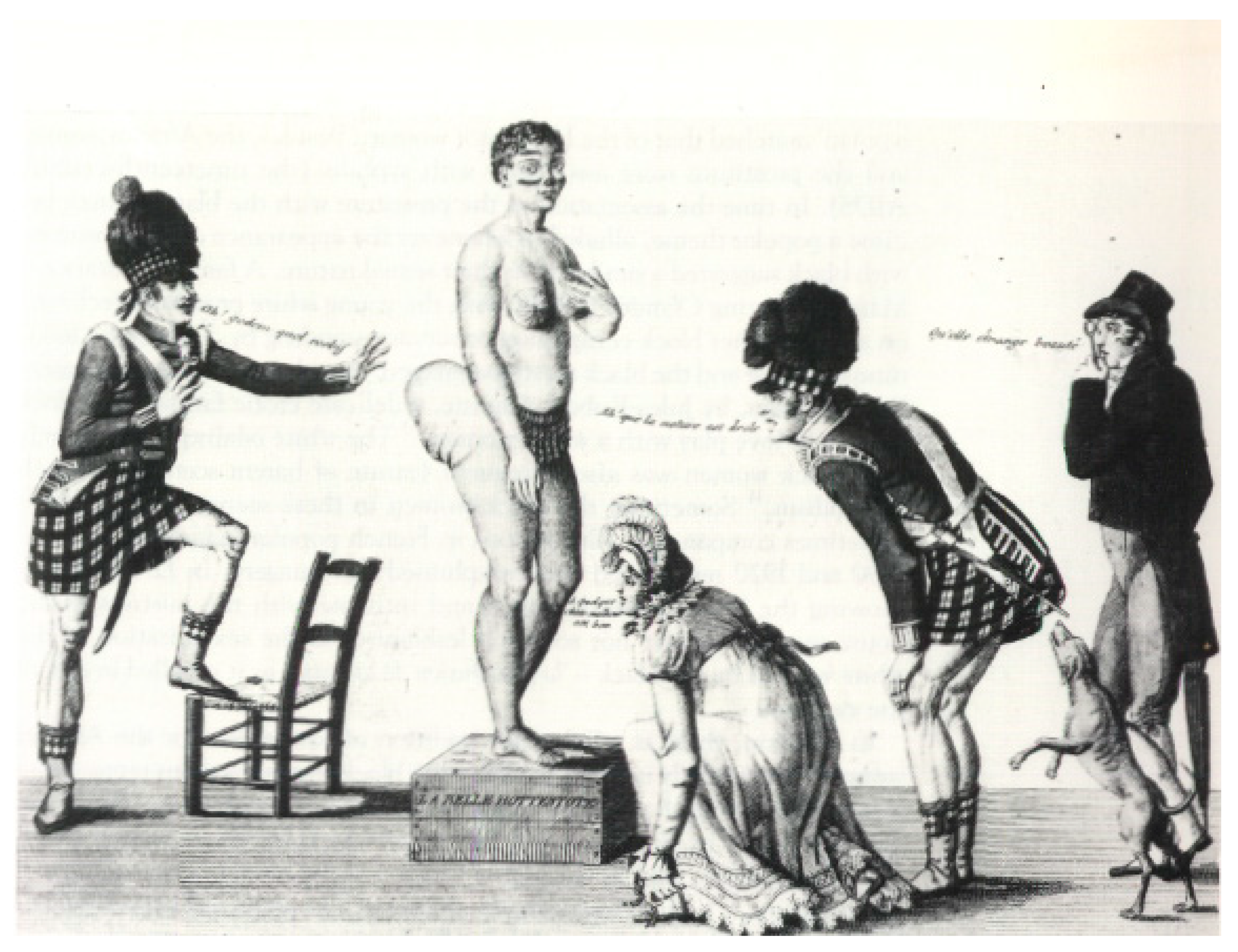

| 17 | I have gathered all the information concerning the title and the translations of French words written in the cartoon from Sharpley-Whiting’s article, “Writing Sex, Writing Difference: Creating a Master Text on the Hottentot Venus.” She writes that the French title could be translated as “The curious in ecstasy or shoelaces.” |

| 18 | Sharpley-Whiting writes that one soldier who is standing behind Baartman and extends her hand to touch her buttocks exclaims, “Oh, goddamn, what a roast beaf!” Another soldier who is gazing at Baartman’s genitals directly observes, “Ah, how amusing nature is!” A third man, who appears to be a civilian, is looking at Baartman through lorgnettes from a distance. He admires Baartman’s beauty by stating, “What a strange beauty!” Sharpley-Whiting further observes that the cartoon derives its subtitle from the pose of the female spectator who is bending down, ostensibly to tie her shoelace. She looks through Baartman’s legs and says: “From some point of view misfortune can be good” (Sharpley-Whiting 1990, p. 21). |

| 19 | Though Sharpley-Whiting argues that the white woman is not looking at Baartman but at the soldier behind her, close analysis of the print also enables this alternate reading of white woman’s gaze. |

| 20 | After Baartman’s death, her brain, hips and other organs were preserved in formaldehyde. Baartman’s body continued to be displayed for the next hundred years in Paris’s Musee de l’Homme. In 1994 Nelson Mandela requested France to return her remains to her native country, South Africa. |

| 21 | Sharpley-Whiting views the moment when naturalist Cuvier dissected the body of Baartman as the seminal moment in the history of “sexual science as it intersects with race.” She contends that this was a moment when “science and ideology merged and a black woman’s body mediated the tenuous relationship between the two “(Sharpley-Whiting 1990, p. 17). |

| 22 | For a detailed discussion of the various conceptions of race, see Zine Magubane’s Which Bodies Matter?: Feminism, Post Structuralism, Race, and the Curious Theoretical Odyssey of the “Hottentot Venus” (Magubane 2001). |

| 23 | For images and examples, see https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/jezebel/index.htm. |

| 24 | Patricia Hill Collins denounces a hip-hop group called The 2 Live Crew for negatively portraying Black women as sexually deviant, hoochie mamas. Their lyrics are vulgar and insulting towards Black women as they sing that they require Black women only for sex: “Sex is what I need you for” (Collins 2000, p. 82). |

| 25 | Patricia Hill Collins deployed the term “controlling images” to speak of the demeaning stereotypes about black women (Collins 2000, p. 5). |

| 26 | Moss observes, “my gifted male peers don’t ask me out because I look cheap and easy […] I am the only girl among them who is the gifted with this look: Lytta’s mark, ladybug marks, and bargain basement price tags. I am cloistered in these marks” (Moss 1998, p. 191). |

| 27 | Peter Abelard explains: “…the skin of black women, less agreeable to the gaze, is softer to touch and the pleasures one derives from their love are more delightful” (cited in Sharpley-Whiting 1990, p. 1). Sharpley-Whiting further mentions how the discourse continued from Peter Abelard’s Letters“ into the Classical period with Paul Scarron’s Epistre chagrin and La Fontaine’s black-white woman Psiche” and developed later in the Age of Enlightenment via “scores of asides, footnotes references, and quasi-scientific studies on black women…by the likes of Denis Diderot, Buffon and others” (Sharpley-Whiting 1990, p. 11). |

| 28 | Underscoring the popularity of the figure of the sexualized Black woman, Sharpley-Whiting notes that “the nineteenth century is the only century in which at least six writers- Balzac, de Pons, Baudelaire, Zola, Maupassant, and Loti- rhapsodized and obsessed over racialized heroines” (Sharpley-Whiting 1990, p. 12). |

| 29 | Sharpley-Whiting theorizes the “Black Venus narrative” as one where “black women, embodying the dynamics of racial/sexual alterity, historically invoking primal fears and desire in European (French) men, represent ultimate difference (the sexualized savage) and inspire repulsion, attraction, and anxiety, which gave rise to the nineteenth-century collective French male imaginations of Black Venus (primitive narratives)” (Sharpley-Whiting 1990, p. 6). |

| 30 | Gilman argues that the “perception of the prostitute in the late nineteenth century merged with the perceptions of the Black.” For instance, the presence of Black servants in William Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress (1733–1734) and A Harlot’s Progress (1731) marks the presence of “illicit sexual activity” (Gilman 2003, p. 175). |

| 31 | Like Sander Gilman, Sharpley-Whiting also traces the coupling of the images of prostitution with Black female sexuality in the nineteenth century. Projection of the notion of “prostitute proclivities, on to the black female bodies,” Sharpley-Whiting argues, enabled the French writers to project a position of “moral, sexual, and racial superiority” (Gilman 2003, p. 7). |

| 32 | Playwright Susan Lori Parks makes the link between Baartman’s posterior and America’s present explicit: “America is past free […] And a protruding posterior is a backward glance, a look which, in this country, draws no eyes. Has […] no rest […] What do we make with the belief that the rear end exists?” (Parks 1996, p. 12) |

| 33 | Elizabeth Alexander is lauded for having recited an original poem, “Praise Song for the Day” at Barack Obama’s Presidential Inauguration in January 2009. |

| 34 | I have drawn the phrase, “Black interiority” from Alexander’s book of essays named The Black Interior. |

| 35 | Alexander discovered facts about her family’s history while working on her family tree with Henry Louis Gates Jr. (Gates 2010). |

| 36 | Maureen McLane argues that “Alexander writes poetry that posits race and racial identity as lived—although not static or reductive—realities…” (cited in Pereira 2010, p. 217). |

| 37 | This view about Sara Baartman being representative of the people of the entire African continent is challenged by scholars such as Zine Magubane. Magubane also raises concerns about Baartman’s identity as ‘Black.’ Magubane argues that Baartman belonged to a tribe that were technically not Black but had yellow skin tone. |

| 38 | T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting cites Georges Cuvier’s Discours sur les revolutions du globe where he observes that Baartman’s “personality was happy, her memory good […] she spoke tolerably good Dutch, which she learned at the Cape […] also knew a little English […] was beginning to say a few words in English […]” (Sharpley-Whiting 1990, p. 24). |

| 39 | Alexander finishes the poem with the following lines:

(Alexander 1990, lines 114–22 emphasis added). |

| 40 | Debra Singer argues that there are visual artists like Carrie Mae Weems, Lorna Simpson and Renee Green “who have produced works that refuse to re-present Baartman’s body visually. Rather, they invoke the body primarily through verbal means in order to focus on how structures of voyeurism and the spectacle affect the construction of desire and sexuality and how these relationships consequently influence formations of black female subjectivity” (Singer 2010, p. 91). For a detailed discussion of the artists and this line of argument, read Debra Singer’s article, “Reclaiming Venus: The Presence of Sara Baartman in Contemporary Art” (Singer 2010). |

| 41 | Judith Wilson deployed this term in relation to the nudes of Black artist Romare Bearden: “By undoing the erasure, marginalization, and fetishistic exoticizing of the Black female nude, he participated in an important recuperative project twentieth century African American art” (Wilson 1992, p. 118). |

| 42 | AdriennePiper has been cited by Frieda High W. Tesfagiorgis (Tesfagiorgis 1993, p. 229). |

| 43 | Black artist Howardena Pindell contends that the “mainstream art world” in America operates like a “close circuit” excluding the activities and achievements of artists’ of color. She stresses that “they do not state it, they practice it. The public sector is even craftier and will state they do not discriminate and roll out the word “quality” (Pindell cited in Bernier 2008, p. 7). |

| 44 | Frieda High W. Tesfagiorgis observes that “the art history and criticism of African Americans prioritize the lives and works of African American men while inscribing women as complements, those of Euro-American feminists center the work and issues of Euro- American women while marginalizing American women of color. Black women artist, in the last decade of the twentieth century, remain semi-muffled, semi-invisible and relatively obscure” (Tesfagiorgis 1993, p. 228). |

| 45 | For details read Linda Nochlin’s groundbreaking article, “Why There Have Been No Great Women Artists” (Nochlin 1971). Nochlin examines how women (at least until the late nineteenth century) were debarred from studying and drawing nudes as nude models (both male and female) were made available only to male artists and students. |

| 46 | This observation by Judith Wilson has been cited by Lorraine O’Grady in her article, “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity” (Wilson 1992). |

| 47 | Elizabeth Alexander makes this observation in an article named, “Reading” the Black Body: or, Considering My Grandmother’s Hair (Alexander 2009). |

| 48 | For a copy of the artwork see https://www.lyleashtonharris.com/series/the-good-life-2/. |

| 49 | I am indebted to Judith Wilson and Lisa Farrington for information about conventions of the nude. |

| 50 | Historian Marilyn Jimenez explains: “for buttocks to gain significance- racial and sexual- they must be revealed; it is all about performance” (cited in Farrington 2005, p. 223). |

| 51 | Lisa Farrington also speaks of this shift in her article on the nude (Farrington 2003). |

| 52 | Cox made this observation about her work in an interview with Artress White (White 1998, p. 45). |

| 53 | For a copy of the art work see https://www.reneecox.org/yo-mama?lightbox=i11c4n. |

| 54 | As cited earlier, Alice Walker critiqued Chicago’s work stating that white women deny Black women vagina and by extension motherhood. |

| 55 | Hortense Spillers observed that “the excision of the genitalia” in The Dinner Party “is a symbolic castration. By effacing the genitals, Chicago not only abrogates the disturbing sexuality of her subject but also hopes to suggest that her sexual being did not exist to be denied in the first place” (Spillers cited in O’Grady 1994, p. 4). |

| 56 | Hugh Honor has been quoted at the length by Lisa Farrington in her article, Reinventing Herself: The Black Female Nude (Farrington 2003, p. 20). |

| 57 | The welfare queen is a stereotype that pokes fun at the unbridled sexuality of unmarried/single Black women with multiple kids and derides them for depending on the welfare state and affirmative action for their upkeep. |

| 58 | This negation of Black female sexuality is evident not only in the USA but is visible in the French academic world as well. Sharpley-Whiting situates her work on Sara Baartman, Black Venus: Sexualized Savages, Primal Fears and Primitive Narratives in French, as a Black feminist intervention on Black female sexuality. Sharpley-Whiting notes that the French literary landscape is replete with the representations of sexualized Black women. She observes that plethora of historical and literary texts that engage with the meaning of Blackness in the French context. Despite the large number of works that engage with Blackness, Black female sexuality and the “French obsession with blacks and blackness” none of them, writes Sharpley-Whiting, is “feminist” (Sharpley-Whiting 1990, p. 2). She further argues that not only are the theoretical studies on the subject of Black femininity and sexuality in France conspicuous by their absence, the ones that exist often function like “colonizing narratives.” They have a tendency to deploy the Black female body to advance discussions of white female and/or Black male sexuality. She also critiques Sander Gilman’s seminal work on the Venus Hottentot and Black female sexuality in France on this count. She points out Gilman’s work offers no details about the central Black female figure that is Sara Baartman herself and the visual representations of Black female body are meant to further discussions about patriarchy’s fear of the (white) female sexuality. Although she does so in the context of representations of Black femininity and sexuality in France primarily, her critique and concerns are relevant for the American context too. |

| 59 | For a detailed discussion of the subject and politics of respectability, refer to Lisa B Thomson’s Beyond the Black Lady: Sexuality and the New African American Middle Class (Thompson 2012). |

| 60 | Lisa B. Thompson explains that the term “Black lady” has been developed from Wahneema Lubiano’s analysis of Clarence Thomas Senate Judiciary Hearings of the 1991. Traditionally lady has both racial and class connotations and the concept of the lady is usually not associated with Black women. Black lady is usually connotes a highly educated, professional Black woman located in an urban set up. Symbolizing the ideology of Black bourgeoisie respectability and racial uplift, there is hardly any reference to Black woman’s sexuality. Despite the fact that she downplays her sexuality, newer racial stereotypes are created where she is targeted as being an overachiever who is sexually frustrated and/or is a single Black woman. For a detailed discussion, read Lisa B. Thompson’s introduction to Beyond Black Lady (Thompson 2012). |

| 61 | Patricia Hill Collins in her insightful work, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment, has also drawn a parallel between the two seemingly disparate “controlling images” about Black women namely, the Black lady and the Mammy. Tracing the history of these images, Collins explains that in the 1980s with the Reagan administration the stereotype of the welfare mother “evolved into a more pernicious image of the welfare queen” and around this time “the welfare queen was joined by another similar yet class-specific image, that of the “Black lady” (Lubiano 1992 cited in Collins 2000, p. 80). Black lady, explains Collins, “refers to middle-class professional Black women who represent a modern version of the politics of respectability advanced by the club women” (Shaw 1996 cited in Collins 2000, p. 80). Despite the fact that the Black lady and the Mammy appear to be polar opposites as they fall on the opposite ends of the class ladder owing to a differences in educational and family backgrounds, Collins contends that “the image of the Black lady builds upon prior images of Black womanhood in many ways.” The Black lady image is predicated on hard work and achievement of these women as Collins explains “these are the women who stayed in school, worked hard, and have achieved much.” This industriousness coupled with working status are the two aspects that enable Collins to draw a parallel between the Black lady and the Mammy figure: “This image (Black lady) seems to be yet another version of the modern mammy, namely, the hardworking Black woman professional who works twice as hard as everyone else” (Collins 2000, p. 81). Collins also argues that the two images appear similar as both give the impression of being the matriarch: “The image of the Black lady also resembles aspects of the matriarchy thesis—Black ladies have jobs that are so all consuming that they have no time for men or have forgotten how to treat them. Because they so routinely compete with men and are successful at it, they become less feminine. Highly educated Black ladies are deemed to be too assertive—that’s why they cannot get men to marry them” (Collins 2000, p. 81). While not negating Collins’s arguments, I, however, wish to stress that Black lady model and the Mammy stereotype are actually predicated on the denial and suppression of Black women’s identity as sexual subjects. If there are to survive and succeed in this racialized, sexualized ecosystem that is also riddled with class politics, there are forced to downplay their sexualities. |

| 62 | I am indebted to Lisa B Thompson (Thompson 2012, p. 5) for these ideas. |

| 63 | Celie realizes that her vagina, which looks “like a wet rose” is way prettier than she thought (Walker 1982, p. 75). |

| 64 | For the artwork see http://carriemaeweems.net/galleries/aint-jokin.html. |

| 65 | Shug tells Celie to explore her Vagina. She explains, “right down in your pussy is a little button that gits real hot when you do you know what with somebody. It git hotter and hotter and then it melt. That the good part. But other parts good too, she say. Lots of sucking go on, here and there, she say. Lot of finger and tongue work” (Walker 1982, p. 75). |

| 66 | When Tashi is admitted to the hospital in order to give birth to her son, a “crowd of nurses, curious hospital staff and medical students” gathered around her bed in order to “peer over” or to see “that creature.” Her body became a “side show” in the hospital (Walker 1992, p. 58). |

| 67 | Shug asserts that “God is inside you and inside everybody else. You come into the world with God […] God ain’t a he or a she but a it […]” (Walker 1982, p. 196). |

| 68 | “God love them all feelings. That’s some of the best stuff God did. And when you know God loves ‘em, you enjoy ‘em a lot more (Walker 1982, p. 196). |

| 69 | Walker only mentions that Queen Anne studied at Berkeley and was raised at a little island in Hawaii by parents who were pagan and worshipped earth. They taught her that it was not mandatory for her to get into a relationship with a man, unless she wants kids (Walker 1992, p. 169). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nanda, S. Re-Framing Hottentot: Liberating Black Female Sexuality from the Mammy/Hottentot Bind. Humanities 2019, 8, 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8040161

Nanda S. Re-Framing Hottentot: Liberating Black Female Sexuality from the Mammy/Hottentot Bind. Humanities. 2019; 8(4):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8040161

Chicago/Turabian StyleNanda, Shaweta. 2019. "Re-Framing Hottentot: Liberating Black Female Sexuality from the Mammy/Hottentot Bind" Humanities 8, no. 4: 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/h8040161