3. Metonymy, Contingency, and Representation

In his philosophy, Aristotle points at two different strategies to overcome what he considers to be the inherent contingency of the world that surrounds us: In his

Poetics, one is the fabula or

muthos that he considers poetry to provide us with, in order to impose order upon the sheer contingency of history; the latter of which he delegates to the historiographers to represent (

Aristotle 1995, para. 23.1459a16–24). Myth, as we all know, is a narrative; its job is thus to impose a narrative order—through selection, omission and compression; a process which necessarily means to distance oneself from the pure contingency of reality. Or, to make the point even stronger: The more we try to create order out of the contingency of historical reality, the more we by default distance ourselves from this very reality. Narrative is, however, a process that takes place on what structuralists would call the syntagmatic axis; and I will come back to this soon. The other strategy to impose order is conceptual thinking, the early form of which Aristotle inherits from Plato: that of dialectics.

As far as the

Poetics are concerned, Aristotle clearly favors metaphor over metonymy—an attitude that he shares with about 95% of his colleagues to come, including Jakobson. Still, in

De Memoria, he reminds us of the fact that one is reminded of a thing by something “either similar, or contrary, to what we seek, or else from that which is contiguous with it” (

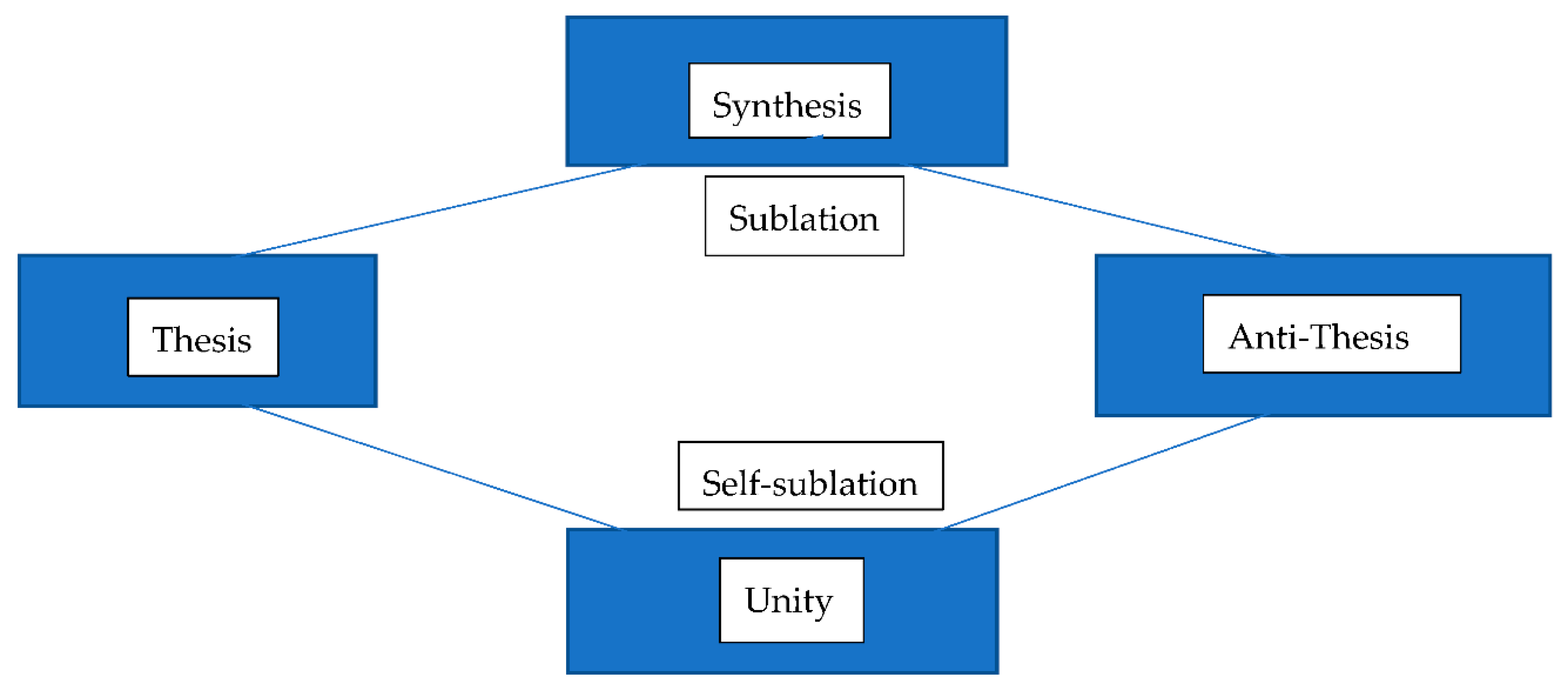

Aristotle 1906, para. 451b 24–25). While similarity clearly belongs to metaphor, and contiguity belongs to metonymy (with certain reservations as regards Aristotle’s definition of contiguity), opposition occupies a very strange position in this triangle; it will be, however, a central part of Hegel’s later dialectics. There, the third that relates tenor and vehicle in metaphor finds its analogy in the prior unity of thesis and anti-thesis. Interestingly enough, any abstraction, be it philosophical or poetic is (indeed, can only be) based upon the assumption of—a third! A third that, in both instances, takes us away from the true contingency of history, in order to establish—order. Thus it might not come as a surprise that a structural similarity can be discerned: that between philosophical dialectics (

Figure 1) and poetic metaphor (

Figure 2):

Interestingly, contingency is what is categorially excluded by, through being juxtaposed to, both dialectics and metaphor (and the dialectics

of metaphor). Moreover, it also forms a highly problematic sting in Hegel’s dialectical philosophy.

1In fact, dialectics can only work if it assumes a prior unity—and thus a basis for comparison or a ‘third’—that self-sublates itself into thesis and anti-thesis, in order to then be, in a second step, sublated into a synthesis. That is, dialectics is in fact a process that implies not a triangle, but a quadrangle; a unity that is being undone by what Hegel calls the self-sublation of the previous unity into thesis and anti-thesis, which is in turn sublated again by the dialectical process into the synthesis. The same, interestingly, holds true for a metaphor: Only on the basis of a presumed third, which guarantees the similarity and comparability of tenor and vehicle, can a metaphor be successful. As in dialectics, a presumed unity (1) is split up into tenor; (2) and vehicle; (3) to be reunited by the reader; (4) on the basis of the presumed former similarity (cf.

Hegel 1991, pp. 79—81).

Fast forward to Roman Jakobson’s famous essay “Two Aspects of Language and Two Types of Aphasic Disturbances”; a text that has massively influenced structuralist and post-structuralist thinking. While evoking the distinction between metaphor and metonymy—the former of which Jakobson connects with the paradigmatic axis of selection, substitution and similarity, while the latter he relates to the aspect of contiguity and syntagmatic combination—he defines the two tropes as follows: While metaphor relies on an abstract ‘third’ (similarity is just that, since otherwise metaphor would not work) to establish the conjunction of tenor (that which should be expressed) with vehicle (that with which it is actually and figuratively expressed), metonymy relies on the concept of ‘contiguity in space’.

Furthermore, he attributes metaphor to romanticism and modernist surrealism, and metonymy to the more prosaic forms of realism. And although he identifies metaphor—very much in the tradition of Aristotle—as a sort of ‘queen of tropes’, he surprisingly adds:

[…] when constructing a metalanguage to interpret tropes the researcher possesses more homogeneous means to handle metaphor, whereas metonymy, based on a different principle, easily defies interpretation. Therefore nothing comparable to the rich literature on metaphor […] can be cited for the theory of metonymy.

Now, what is so strange about this quote is that, on the one hand, he connects metonymy with the prose of realism—which, in order to achieve its closeness to reality, tends to avoid figurative language and is thus less focused on metaphor; however, on the other hand, he tells us that metonymy “easily defies interpretation”, which is what one would certainly not usually accuse realism of. So what is it that makes prosaic metonymy the ‘ugly duck’ of tropology—one, at least that, as Jakobson notes, has by far not attracted attention comparable to that given metaphor—and such a difficult one at that? And does the fact that it is hard to decipher have any repercussions on the role it could possibly play to think of realism in a new way? In what way might realism’s and neorealism’s metonymic quality “easily defy interpretation”?

Moreover, another problem arises, as Jakobson, in another essay, establishes the following—and in the meantime almost classical—distinction between metaphor and metonymy:

The selection is produced on the base of equivalence, similarity and dissimilarity, synonymity and antonymity, while the combination, the build-up of sequence, is based upon contiguity. The poetic function projects the principle of equivalence from the axis of selection into the axis of combination.

And he adds a little later: “Poetry and metalanguage, however, are in diametrical opposition to each other: in metalanguage the sequence is used to build an equation, whereas in poetry the equation is used to build a sequence (ibid)”.

Now, the problem that arises is as follows: Metonymy occupies a very strange position in this “equation”: Qua trope it belongs to the paradigmatic axes, which is the axis of selection; and I select a metonymic expression to express something it is not. This becomes even clearer when we take into account that metonymy originally means ‘misnomer’.

3 On the other hand, it ‘embodies’ the syntagmatic principle of contiguity—that which emphatically belongs to combination, and not selection. This would suggest the following conclusion: If the poetic—which would be the metaphoric—function “projects the principle of equivalence from the axis of selection into the axis of combination”, does then not metonymy do the exact opposite, namely “project the principle of contiguity from the axis of combination into the axis of selection”? This would be a feasible—and, indeed, the only logical—conclusion to draw. However, there arises another, huge problem: Because that option is already taken, in Jakobson’s scheme, by the

metalinguistic function, the most important aspect of which is to “interpret” the poetic one. If, however, the poetic function of language seems to be reserved to metaphor—which embodies the paradigmatic in a much more straightforward way than metonymy, since the latter dances on both weddings, and thus undercuts any clear dialectical opposition—this would imply that we interpret metaphor by means of a metonymic operation, which could then explain the difficulties as regards interpretation that Jakobson mentions. That, however, does not really help because he explicitly singles out metonymy as the trope ‘easily defying interpretation’. Moreover, this would go straight against the assumption of David Lodge, who, in his

Modes of Modern Writing, concludes that the metalinguistic operation would have to be by default metaphoric, as we can interpret any text only by establishing a third that would allow us to make sense of it:

The solution would seem to lie in a recognition that, at the highest level of generality at which we can apply the metaphor/metonymy distinction, literature itself is metaphoric and nonliterature is metonymic. The literary text is always metaphoric in the sense that when we interpret it, when we uncover its ‘unity’ […], we make it into a total metaphor: the text is the vehicle, the world is the tenor. Jakobson himself […] observed that metalanguage (which is what criticism is, language applied to an object language) is comparable to metaphor, and uses this fact to explain why criticism has given more attention to metaphorical than to metonymic tropes.

This would prove the close relatedness of metaphor and dialectics that I have suggested above: The reader has to ‘retranslate’ the metaphoric operation of the author on the assumption of an existing third, on the basis of which this retranslation can be more or less successful. Fact is, however, that if the linguistic turn itself has shown us anything, it is that language does emphatically

not work ‘metaphorically’, in that it is exactly that ‘third’ that language, according to Saussure, actually lacks: What characterizes the arbitrary nature of the sign is that no third that would ensure a logical connection between the signifier and the signified can be located; language’s negatively-differential character on the level of both signifier and signified

precludes any third between the signifiers and the signifieds, respectively. Saussure’s assumption that the signifiers attain their value only through “opposition” through others is a lame—and failed—attempt to retain some form of dialectics:

The moment we compare one sign with another as positive combinations, the term difference should be dropped. It is no longer appropriate. […] Two signs, each comprising a signification and a signal, are not different from each other, but only distinct. They are simply in opposition to each other. The entire mechanism of language […] is based upon oppositions of this kind and upon the phonetic and conceptual differences they involve.

While it is rather strange that the quote ends on “differences”—the very ones he urges us to dispel—there is no reason why the value of a sign, achieved through being different from others, should be conceived as “opposition”: ‘cat’ is by no reasonable means the opposite of either ‘hat’ or ‘cut’. Thus, the negative-differential relationship is one of pure contingency, also known as—metonymy. Enter: Paul de Man.

In “Semiology and Rhetorics” (

de Man 1979), de Man takes up Jakobson’s rather uneven and uneasy opposition between metaphor and metonymy, in order to give metonymy the due that Jakobson claims it has not been given. De Man’s main objective in the essay is, in good old poststructuralist fashion, to show that metonymy plays an even more important role than Jakobson is willing to concede it, and to put into question the ‘tendentious’ opposition it is based upon. All this in order to show—another well-known deconstructive move—that a clear-cut distinction cannot be drawn, and that Proust’s

Swann’s Way, which de Man analyzes, deconstructs itself. To make this move possible, de Man basically erases reference:

By an awareness of the arbitrariness of the sign (Saussure) and of literature as an autotelic statement ‘focused on the way it is expressed’ (Jakobson) the entire question of meaning can be bracketed, thus freeing the critical discourse from the debilitating burden of paraphrase. […] It (semiology) demonstrated that the perception of the literary dimensions of language is largely obscured if one uncritically submits to the authority of reference.

Reference—that is, the metalinguistic aspect—is thus reduced to reflect upon the inner closedness of the literary text; an assumption that Proust’s text underscores through its own self-reflectiveness. The text, with its references to reading and other structures of mise en abyme, provides its own metalinguistic interpretation.

Without going into further details, what I am interested in are de Man’s conclusions:

A rhetorical reading of the passage reveals that the figural praxis and the metafigural theory do not converge and that the assertion of the mastery of metaphor over metonymy owes its persuasive power to the use of metonymic structures. […] For the metaphysical categories of presence, essence, action, truth, and beauty do not remain unaffected by such a reading.

(ibid, p. 15; my emphasis)

And he describes the difference between the two as follows:

[…] the difference between metaphor and metonymy, necessity and chance [is] a legitimate way to distinguish between analogy and contiguity. The inference of identity and totality that is constitutive of metaphor is lacking in the purely relational metonymic contact: an element of truth is involved in taking Achilles for a lion but none in taking Mr. Ford for a motor car. The passage is about the aesthetic superiority of metaphor over metonymy, but this aesthetic claim is made by means of categories that are the ontological ground of the metaphysical system that allows for the aesthetic to come into being as a category. The metaphor for summer […], guarantees a presence which, far from being contingent, is said to be essential, permanently recurrent and unmediated by linguistic representations or figurations.

(ibid, p. 14; my emphases)

What is so strange about this distinction is that, on the one hand, metonymy as part of the syntagmatic axes is relegated to ‘chance and contiguity’; on the other hand, the ‘programmed patterns’ and the ‘impersonal precision’ (p. 16) of grammar exert their force to ensure that chance and contiguity are being held in check. But then, the syntagmatic axis cannot stand for contiguity and chance any more! Metonymy’s own contingency either evaporates when being projected upon the paradigmatic axis, or it is reined in by the rules of grammar. What is it that seems to conspire against metonymy to such a degree that it is repeatedly being invoked, just to be ground to naught between the prominence of metaphor and the logic of grammar? Somehow, dialectics does not seem to work in this case; metonymy seems to be based on a mythic both/and logic, but is being crushed at the same time. On the other hand, there is metaphor which, rather surprisingly, de Man characterizes as evoking a presence that is ‘essential, permanently recurrent and unmediated by linguistic representations or figurations’! Proximity—a.k.a. contingency—as de Man rightly observes, can only “pass the test of truth” if it acquires “the complementary and totalizing power of metaphor” and is thus “not reduced to the ‘chance of a mere association of ideas’. […] The relationship between the literal and the figural senses of a metaphor is always, in this sense, metonymic, though motivated by a constitutive tendency to pretend the opposite” (p. 71). The challenge then would be to see through such pretentiousness, and not read literature as metaphoric, but to acknowledge that it might actually just offer the “chance of a mere association of ideas” that defy metaphorico-dialectical totalization.

4 4. Narrative and the Problem of Contingency

In order to illustrate this further, let us take the example of a

muthos; to be more precise, a Native American origin myth. In “The Iroquois Depict the World on the Turtle’s Back” (

Hurtado and Iverson 1994), we learn the story about twins who mutually vie for predominance; a fight that actually already starts in the mother’s womb. The right-handed one is born in the normal way, the left-handed through the mother’s armpit. The right-handed one tries to do everything the normal way; the left-handed does everything in a ‘crooked’ manner. A chart of the respective characteristics of the two twins would look something like this (

Figure 3):

While thus, as the myth tells us, trying to create ‘a balanced and orderly world’, the twins still keep on fighting, but neither one can decisively beat the other. In order to solve the conundrum, the story then offers a rather surprising turn: Just once, the right-handed twin lies to the left-handed twin, while the left-handed twin decides to tell the truth. In the final duel, the right-handed twin kills the left-handed one, and throws him “off the edge of the world”, but “some place below the world, the left-handed twin still lives and reigns” (p. 22).

Both the oppositional structure, as well as the chiasmic turn that the story takes, lend themselves perfectly to a structuralist, as well as a poststructuralist reading, as the story does not only create oppositional pairs, but also lets them switch places and thus insinuates that none of the binary oppositions is as ‘pure’ as one might think. However, and this is my main point, narratively speaking all of this hinges on a moment in the story—both twins simultaneously, but unbeknownst to each other, deciding to suddenly change their roles: a highly improbable scenario. But what then is the

muthos or the fable in this Iroquois myth? Is it the oppositional structure that, in a Lévi-Straussian reading, looks like an early form of dialectics, or is it a totally contingent turn in a strange story? Well, it was exactly this ‘narrative’ strangeness or eventfulness that Lévi-Strauss wanted to overcome with his structuralist analyses, in trying to carve out, in a kind of vertical reading, the columns that he so famously introduced in his seminal essay “The Structural Analysis of Myth” (

Lévi-Strauss 1955). However, what is getting lost in this procedure is exactly that narratively highly contingent and utterly improbable moment that leads to the chiasm, that in turn deconstructs the purity of the binary pairs, but that in itself cannot be dialectically accounted for.

5If that holds true, however, what does the difference between mythical and syllogistic reason that he so emphatically insists on really consist of? As I have argued elsewhere, it consists of a logic that is not syllogistic (a logic, that is, that follows an either/or structure), but cosmo-logic (based upon a both/and structure).

6 In Lévi-Strauss dialectic-structuralist reading, an important part of this difference gets blurred, in that the narrative moment of contingency that makes the chiasm both possible, but at the same time questionable and ‘impure’, simply disappears. Only then is the

muthos able to introduce the very order that Aristotle ascribes to it.

However, the both/and cosmo-logic itself creates a problem, in that it defies syllogistic reasoning so dear to dialectics from Plato and Aristotle to Hegel and beyond. In fact, we can define a syllogistic contradiction as a special form of contingency: The coexistence in space and time of A = B and A ≠ B. Or rather, instances where A and B simply are not oppositions, but differences.

Having looked at contingency from both the Aristotelian and the structuralist side, we are now in the position to distinguish two levels of contingency: An epistemological contingency that characterizes reality proper, upon which either a narrative muthos or a dialectical/metaphorical order can be imposed, and a representational contingency that affects the means by which this order is being imposed. One could argue that, talking about the axes of combination and selection, or metaphor and metonymy, we are in the face of an ‘impure’ dialectics, as the combinatory character of metonymic narrative and the conceptual/dialectical character of metaphor are by no means equivalent: Narrative and metonymy constitute something like a ‘first line of defense’ against contingency, while the conceptual/dialectical character of metaphor is clearly given pride of place. Myth, then, is emphatically not a compressed or ‘mini’-metaphor (or is so only when one chooses to read it dialectically): If anything, myth works metonymically. Rather ironically, Lévi-Strauss, through his dialectical-metaphoric reading of myth, thus purges it of that which is actually its most marked difference to syllogistic thinking: its acknowledgment of a remainder of narrative contingency. Thus, in trying to establish it as an ‘other’ form of logic (an ‘analogic’, as he calls it), he deprives myth of what might be most important about it; and, maybe, of that which still makes it such a virulent genre.

5. Neorealism, Mimesis and Contingency

The insights gathered through our excursus thus allow us to draw some conclusions that apply to contemporary literature, too. Thus, neorealism—and in our case, Franzen’s

Freedom—has to address two challenges: On the one hand, it has to face the representational challenges imposed by the linguistic turn; on the other hand, it still tries to represent the contingency of real facts—without, however, giving in to the didactic agenda of classical realism that tries to achieve a consensus by means of a violence-free dialogical deliberation, since—at least on the side of the reality depicted—such an attempt seems doomed to fail: Both alienation and self-alienation are part and parcel of this reality. Moreover, one of the earliest instances of American realism—Henry James’ short story “Daisy Miller”—already shows, that even if there exists the wish to make both two persons (who are moreover attracted to each other) mutually decipherable to each other, and to decipher the cultural environment they operate in, success is by no means guaranteed: The tragic end of the protagonist Daisy Miller is caused, in the final instance, through her inability to read her suitor, Winterbourne, and to read the writings on the wall as regards the danger of catching Roman Fever.

7 That is, even if neorealism were simply to ‘go back’ behind the agendas of modernism or postmodernism, it would most likely reach the spot again that James reached at the end of his literary career, when all hopes and pretensions to reach ‘consensus by dialogical deliberation’ are given up in the hermetic short story “The Turn of the Screw” (

James 1967).

However, as my new take on structuralism’s attitude to metonymy was supposed to show, this latter contingency does not necessarily entail a complete ‘blockage’ from reality through language. One could define neorealism as an inherently ironic as-if attempt: How can we possibly address reality’s contingency if language always poses an obstacle that makes it impossible to get there? That is, what if language

were able to represent reality? What if this new realism were to ‘mime’—even if only metaphorically, as we now know—a reality ripe with contingencies that cannot be sorted out, as the early James hoped, through a form of ‘communicative reason’? And I am using the concept of Aristotelian mimesis here in the sense that Jacques Rancière has given it in

The Politics of Aesthetics: Not as “resemblance, as some appear to believe, but the existence of necessary connections between a type of subject matter and a form of expression” (

Rancière 2004, p. 53). Now, what ‘forms of expression’ can a neorealism take whose subject matter is not, as in classic realism, the dialogic creation of a consensus designed to overcome the contingency of the ‘real’ world, but the sobered realization that this does not work, as well as the realization that the ‘forms of expression’ themselves are ‘infected’ or ‘poisoned’ by the contagious contingencies of language proper?

That is, both layers of contingency are reconnected again in neorealism: an epistemological one and a representational one. The epistemological one is narrative, or the muthos, that forms a first front line to capture metonymically (even if the syntagmatic axis is subjected to the ‘laws’ of grammar, as we have seen) the contingency of reality. The second one, the representational one, language itself, which is exposed to the same contingencies as is reality, as Saussure has shown. The problem with metonymy, which Jakobson defines as being “more difficult to decipher”, could thus be explained by the fact that, qua trope, it belongs to both the syntagmatic and the paradigmatic axis. But if it forms one of the main characteristics of realism, then one could argue that it is so difficult because it contains remnants of this very contingency that dialectics or metaphor try to overcome. Through such remnants, it contaminates—as contingency is prone to do—the metaphorical attempts to overcome it. Or, as de Man puts it: “it fails to acquire the complementary and totalizing power of metaphor and remains reduced to ‘the chance of a mere association of ideas’”; or a metonymy “motivated by a constitutive tendency to pretend the opposite” (p. 71). Since de Man is talking about a modernist text by Proust, we might then simply add that what distinguishes neorealism from both modernism and classic realism is that it has given up on just such pretense.

What Susanne Rohr has claimed in connection with Franzen’s novel

The Corrections—that the novel develops “a fictional reality of disorientation, insecurity and imbalance within the bounds of the seemingly known and familiar” (

Rohr 2004, p. 93); a claim strongly reminiscent of Freud’s ‘uncanny’, which is also echoed by Shklovsky’s modernist definition, in “Art as Technique”, as the defamiliarizing aspect of art—holds even truer for

Freedom: No dialogical/dialectical deliberation is able to overcome the almost total collapse of ‘recognition’ (and we can ‘

re-cognize’ only what is familiar, a.k.a. the metaphorical ‘third’) that the novel traces. Moreover, giving the reader more insights into the Berglund family than they have of themselves, he can witness the total failure of communication, even in everyday language. That is, we as readers have to be able (more or less successfully) to read the protagonists in order to read their communicative failure; another instance of an ‘allegory of misreading’. Alienation and self-alienation, that is, affect not only language after the linguistic turn, but are still—or maybe even more—part and parcel of our contemporary, and highly contingent, times. That is why neorealism (or, for that matter, any other genre) cannot possibly serve any other purpose—at least for philosophers of recognition such as the Hegelian Honneth—than as a pathology-diagnostic one. However, I would argue that, if anything, neorealism constitutes a rather ‘difficult’ negotiation of the basic tenets of any theories of recognition—be they epistemological or representational ones. It is characterized, in a manner similar to late romanticism, by an ironic ‘as-if’ quality: If late romanticism’s irony is inspired by the matured insight that early romanticism’s attempt to consciously reach an unconscious state is doomed to fail, neorealism might be defined by the similarly ironic quality to show that, even if one were to achieve referentiality by means to resorting to a metonymic quality in language (representative contingency), a second layer of contingency opens up (epistemological contingency). It thus stands in a matured-ironic relationship to early realism’s optimistic assessment that consensus can be reached dialogically: Even if the linguistic means to establish a consensus

were available, the transcendental homelessness—to which early realism offered a first reaction, and to which we are still exposed—effectively prevents to reach a consensus in a world characterized by utter contingency. The

Freedom that Franzen’s novel alludes to is thus mainly the freedom to misread and misrecognize the other and the world around us; this, however, is something that already Hegel was aware of: That freedom depends upon contingency to exist in the first place; otherwise we would simply be the pawns in a dialectical game that might as well go on without us.

What

Freedom also shows us is that one of the central assumptions of theories of intersubjectivity—the fact that we, as Fluck puts it with reference to George Herbert Mead, to whose theories Honneth resorts in

The Struggle for Recognition, “cannot possibly not know each other because we only learn who we are in interactions with others” (

Honneth 1995, p. 75)—is just half of the truth: The claim ‘we cannot possibly know ourselves because we only learn who we are in interactions with others’ could claim equal validity; as would, for that matter, the statement ‘We cannot know ourselves because we cannot know the others through which we allegedly come to learn ourselves’. This hints at the conceptual impasse at the heart of recognition: I need the recognition of others who, qua others, are not qualified to recognize me, and thus prone to misread me, and especially my particularity, which is what distinguishes me from then.

8I am thus afraid that simply to Houdini-like make the implications of self-alienation go away, as theories of recognition try to do, works neither on a conceptual nor on a historical level. Moreover, if we indeed are who we are only through the input and recognition of others, what does that do to the assumption that we all have a particular potential which we (and others) are ethically urged to help develop? Nor—and again, Freedom (and countless other novels) can serve as examples—does the emotional attachment of a parent guarantee that recognition succeeds, as Honneth seems to presuppose; an emotional attachment that not only precedes recognition for Honneth, but that actually constitutes a precondition of the latter—even if, as I argued, a questionable one.

In the view of Franzen’s novel, the one thing we are free to be is to be free to self-alienate, and to mis-recognize others. In fact, freedom might manifest itself exclusively in these categories. The dream to return to a state of referential stability in order to get back to an Adamic, unspoiled state of linguistic transparency, individual authenticity and a disambiguated reality miserably fails, and thus will not do the trick to reconnect us with a world—realistic or romantic—long gone, but that might as well have never existed.

In light of these considerations: What then

is the factual status of literature in recognition theory? One recent instance where literature is referred to is Axel Honneth’s

The Right to Freedom, which Fluck also invokes:

In his more recent study Das Recht der Freiheit, which aims at a comprehensive social theory, references have become more frequent, and include a number of well-known authors, ranging from Henry James, Jane Austen, George Eliot, Charles Dickens, Émile Zola, and Victor Hugo to contemporary writers like Philip Roth and Jonathan Franzen. However, these references are scattered in unsystematic fashion over the 600-page volume and obviously have the function to provide additional anecdotal evidence for particular points of social analysis.

(p. 30/1)

This, in turn, is an assessment I absolutely share. This “anecdotal” function is what literature has been reduced to in recent philosophies of recognition; and, as already mentioned, Franzen is an unlikely candidate for key witness to prove their point. While all literature, as Fluck indicates, might be (one way or another) ‘about recognition’, a short glance into literary history confirms that, if anything, the ‘dramas of recognition’ that literature has historically staged (and still stages) have become more and more that: tragedies, which not even the playfulness of postmodernism has managed to offer relief from. Dramas usually evolve out of what are either incompatible claims or unfulfillable desires, both of which are at the heart of the problems of recognition: I wish to be recognized by others—who, by being others, read me differently from how I read myself; or I wish to be recognized according to certain qualities that are not deemed worth recognition by society or significant others. And, I assume, not even comedies of recognition would serve effectively as a backdrop for a philosophy of recognition that seems bent on ignoring the insights that literary history might have to offer. However, one might, keeping literary history in mind, re-conceptualize the transition between modernism and postmodernism as just such a transition: from tragedies to comedies of mis-recognition.

This brings me to the following quotation from Fluck, which is taken from the conclusive chapter of his essay:

Still, we should add that this literary call for recognition has a particular status. This qualification can draw our attention to a special role literature plays in the ethical world. I think its special contribution does not lie so much in the formulation or legitimation of ethical principles—in that sense, literature is rarely a philosophical genre—but in the articulation of individual claims for recognition. Its starting point are often experiences of misrecognition, of inferiority, weakness, injustice; and its plots consist in the struggle against these experiences, a struggle that can be either successful—often, in fact, triumphantly successful—or end in defeat, which, in a paradox typical of aesthetic experience, can nevertheless provide strong experiences of recognition. But the key point here is that these claims for recognition can be—some would even say should be—radically subjective, self-centered, and partisan.

(p. 40)

This is a definition of literature that, in my view, with its emphasis on radical subjectivity, self-centeredness and partisanship, clearly rests upon a modernist paradigm. As such, it certainly is not applicable to all kinds and eras of literature, and it in fact points at the contribution that modernism and postmodernism have made; contributions all but neglected by theories of recognition for which neither radical subjectivity nor its other—radical self-alienation—can serve as a suitable example. If, as such, literature offers a challenge to the latter—but if, as such, it also represents certain moments in literary history—then the question as to why literature plays such a minor role in contemporary critical theory might be answered. If its claims to recognition are indeed ‘radically subjective, self-centered and partisan’, (and emphatically not intersubjective, not even in its neo-realist varieties), then this tells us a lot about the potential failure or success of recognition.

If we are to recognize another human being, we have to ‘read’ him or her, as we do an object—with the exception that we might admittedly be able to empathize more with the former than the latter. Empathy, however, becomes a highly problematic process once we turn to Iser’s theory of the gaps that constitute and activate the act of reading: If we, as Iser claims, fill the gaps that the text offers,

9 and that instigate communication as such, with our own background of cultural and personal knowledge, and we presume this also to happen when we ‘read’ another person, then what happens is that we project our own experiences upon the person in question. If, however, we assume that recognition is geared toward recognizing what is unique and specific about me or others—that is, what emphatically

distinguishes me from them and them from me—then filing the gaps with the experiences of those who are designed to do the recognizing means that the gaps will be framed by the contingencies of the horizon of experiences and knowledge of the person who is doing the recognizing. That is, what happens in such a moment of recognition is not that I am putting myself in someone else’s shoes, as a colloquialism has it, but that I am putting that someone

in my shoes. The other’s desire to be recognized clashes with my desire to make him or her ‘recognizable’ to me, and thus to erase or ignore the very contingency that his/her alterity creates for me. And, if anything, this is what Franzen’s

Freedom beautifully illustrates. Moreover, if the experiences needed and used to fill the gaps are affected by self-alienation, the entire modern problem reappears with a vengeance.

6. Towards an Ethics of Literature

Recognition, that is, might be a ‘desire’ articulated, in various forms, in all literature. As such, however, it has to reckon—as do all other desires—with counter-desires, obstacles, failures, both social, linguistic, conceptual, as modernism and postmodernism have not tired to inform us, as well as the desire of others. Intersubjectivity, in such a scenario, constitutes as much—if not more—of an obstacle than a solution.

To simply presuppose a desire as a foundational paradigm, as theories of recognition do, is questionable, to put it mildly. And the answer to the question as to what it is that literature can contribute to a theory of recognition is problematic, because (a) the question is, in my view, wrongly put; which is why (b) one answer might lead to the conclusion that theories of recognition would have to reduce literature to “childish” uses, as (

Fluck 2015, p. 25) rightly indicates. What literature

can do is to expose the basic assumptions of theories of recognition—those about an ethics of paternal care, and those posing a desire as a starting point that all earlier literary theories have shown to be unfulfillable—as immature, indeed ‘childish’ themselves.

10 That is, the self-assertive task of literature (and its theory) is to unveil the hopeless naiveté upon which theories of recognition are based, while literary history might serve to indicate why this is the case. This is so because the answer to the second question raised at the beginning—what literary paradigm the philosophy of recognition might eventually rest upon—is, I dare say, a rather disillusioning one. From the perspective of literary history, it simply implies an anachronism, a step back. Modernism’s self-alienation and postmodernism’s linguistic alienation-cum-

jouissance might certainly be incompatible with the tenets of recognition; however, and because of this, they hold a high critical relevance for it that we would be well-advised not to ignore chasing the slightly outmoded, if not immature, specters of recognition.

Finally, if we do want to take intersubjectivity seriously—and in a way that not only does away with self-alienation, but that acknowledges the latter’s continuing existence and relevance, and maybe merges the two options—then we have to negotiate whether our ethical concerns should indeed take as their starting point the assumption of a unique, but enclosed, subject with a potential that it is expected to achieve, and others that are morally required to help do so. If we indeed are always already exposed to others before we mature into alleged unique subjects—subjects, moreover, as Honneth puts it, ‘only realized in relationship to others’—then this requires us to not only see others as potential obstacles (which, in the last instance, any theory that combines concepts of authenticity with moral agency necessarily does), but also as contributors to this very subject; a subject, however, that can then not serve as the exclusive starting point of any ethical consideration. A subject, moreover that, conceived as processual due to the ongoing exposure to the contingency of others, cannot possibly be measured applying the yardsticks of either authenticity or recognition (cf.

Claviez 2019).

What would be the role for literature in such a scenario? It could certainly do more than to ‘register the failure of fully achieved recognition’—in pointing out recognition’s precarious presumptions, and the pitfalls these imply: The most important one being that, if recognition is being withheld—due to whatever reason, even simple linguistic ones—we will always search for a scapegoat that we can blame for this failure: others, society, my incapability to make myself readable. A scapegoat for a process, moreover, the contingent character of which can only appear inherently flawed if presumed to be teleological, no matter how strong the alleged desire for it might be. As to my own life-story, so to any book a wide variety of characters, views and claims contribute—sometimes positively, sometimes in a detrimental manner (which later, however, might turn out to cause some good). Interestingly enough, any CV constitutes but a chain of contingencies. Literature’s ethical contribution, consequently, might be to point out the fact that this is the case, and that philosophy’s assumptions of the status of the subject—be they based on self-alienation or intersubjectivity—might stand in need of revision. Ironically, literature might indeed be the more ‘intersubjective’ discourse, in that it helps to show us that any claim to recognition—as ‘radically subjective, self-centered, and partisan’ it may be—is confronted with others as radically subjective, self-centered, and partisan. But even more: it might show us that this is in fact more of an asset than an obstacle to a subject that is always in the process of becoming, and thus defies any assumption about an ‘authentic’ subject in need of recognition; a recognition that, consequently, does not only prove to be unachievable—but actually, dangerous, as I have tried to show elsewhere. Dangerous, in that it—as authenticity—defies history (both of single subjects, and as writ large) and its contingent character.

This distinction between the presumptions of a theory of recognition and that of literature can probably best be illustrated with another recourse to Shklovsky’s “Art as Technique” (

Shklovsky 1988). The conception of recognition that its proponents uphold is designed to familiarize us with (that is, re-cognize) the unfamiliar, and thus to shear others (or the Other) of their/its otherness. The liberal technique of reducing any singularity of individual to the abstract number 1 is probably amongst the best-known of such strategies. While we thus recognize what cannot be ‘cognized’ in the first place, Shklovsky insists that it is art’s task to ‘un-’ or ‘defamiliarize’ us with the familiar; that is, to urge us to rediscover the very alterity that recognition (and its pre-modern, aesthetic strategies) have to suppress at all cost to ensure its success. Literature, I am afraid—or proud—to say, is far ahead of philosophy in this regard. And if we presume that the problem of ethics only arises once there is otherness—and that we should not recognize it out of existence—then this is where an ‘ethics of literature’ can come in.

By way of an ending let me address another facet of contingency that manifests itself in other neo-realist novels, such as Dave Eggers Circles, for example. In the case of this novel, it seems that not so much the question of contingency, but rather the sometimes questionable attempts and techniques to overcome said contingency play an important role. I would argue that this does not devaluate my argument. Not only would the ‘neorealistic’ strategies to address the contingency of the world by default also have to reflect upon strategies to rein in contingency; they thus address also an aspect of contingency that feeds into a way larger picture: For centuries—that is, at least since the Enlightenment—we have been telling ourselves the story of human development as a story of the succession of allegedly ever more successful strategies to overcome contingency; usually along the lines of myth, monotheism, and syllogistic reason. On the other hand, if anything characterizes not only our literary, but also our philosophical and political landscapes, it is an ever increasing feeling of contingency, precariousness, and exposure toward forces beyond our control—which might want to induce us to rewrite that questionable success story. All our attempts to minimize contingency have obviously lead to creating even more contingencies, rather than less. To maybe induce us to take a different stance towards contingency might be part and parcel of the project of neorealism.

And, as a last point, let me remind us that the problem of contingency has been with us for quite some time—actually, since modern times generously defined. However, in a trajectory that seems to be far removed from our petty debates about truth or untruth, contingency has been tackled in a manner that might prove much more relevant for ethical and political debates. I am talking about mathematical and statistical attempts devoted to

The Taming of Chance, as the title of one of Ian Hacking’s books has it.

11 That is, banks, insurances and other economic and political stakeholders and power brokers have devised stratagems not simply to deny contingency, to define it out of existence, or to overcome it at the costs of creating even more contingencies, but to

acknowledge it in order to deal with it. Considering this, some of our philosophies seem to be barking up the wrong tree. Some of our literature, however, does not.