1. Introduction

The completion of the reconstruction of the Cheonggyecheon stream and park in Seoul, South Korea in 2005 was hailed by Lee Myung-bak, who was then mayor of Seoul, as the city’s return to what “Mother Nature intended it to be” (

Kirk 2003). The project began with the demolition of an aging piece of infrastructure, a 5.8 km elevated highway, and replaced the site with a green space with a reconstruction of a historic stream at its center. The implication of Lee’s statement highlights two major assertions for the project in transforming the project site from a road with an aging overpass into a sunken pedestrian channel with a reconstructed stream. The first is that the project allowed a return of the site to its original, natural condition. The second is the suggestion that the intervening years of the site serving as a road and highway overpass were either contradictory to nature or were misguided interventions of city officials in building a road and highway and burying the stream during the country’s rapid modernization period (

Lee 2011). These assertions illustrate the promotion of the reconstruction project as a symbol of the post-modern identity of Seoul as a city that blends the urban landscape with natural forms and forces. The project has helped promote and reinforce the image of the city as having an origin in the surrounding natural forms of mountains and streams, as well as a modern city that provides plentiful access for its people to engage with and enjoy the natural landscape that is intertwined with the urban landscape (

Seoul Metropolitan Government 2006,

2009). With the transformation of an area that had been dominated by vehicular traffic into one with a dedicated pedestrian space that offers respite from the city and serves as a popular public open space, the Cheonggyecheon illustrates the efforts of Seoul’s leaders to build a different kind of city than what it had been through much of its modern history.

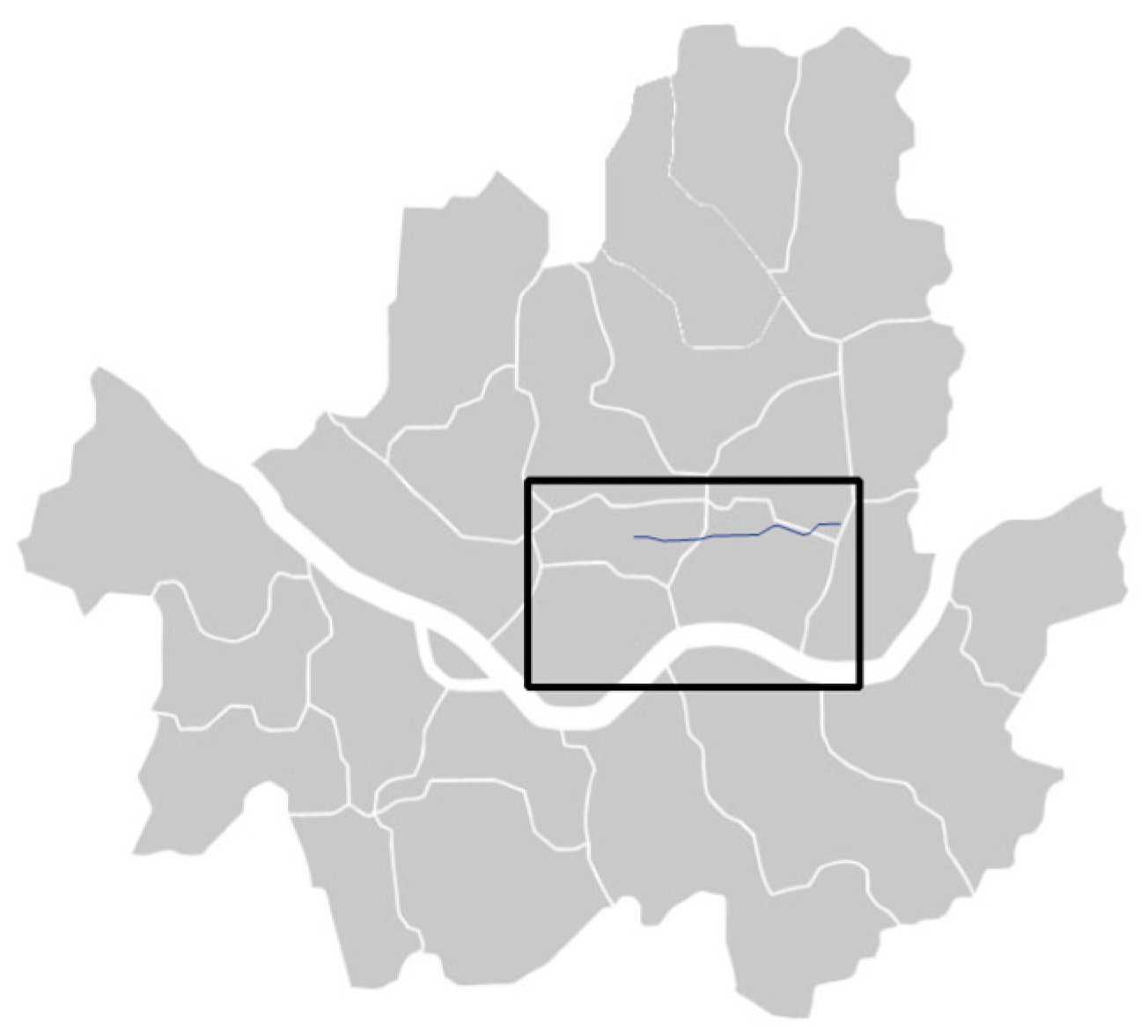

The Cheonggyecheon is an example of a landscape urban renewal project that elicits broad questions about nature, history, and the changing contemporary city. The reconstructed stream and park begins in the central business district of Seoul, north of the Han River, which splits the city into north and south parts, and flows east to meet another stream, then converges into the Han River, totaling approximately 11 km in length (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The completed project cost

$386 million USD, and was completed in 27 months of demolition and construction (

Lee 2008, Interview 15;

Seoul Metropolitan Government 2006). The name Cheonggyecheon, which means “clear stream,” has endured through various transformations of the site. It was originally applied to a historic stream that dates back to the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910), then passed onto the road that was built when the stream was covered beginning in the 1940s, followed by the highway overpass built over the road in the 1970s, and finally to the park completed in 2005 (

Rowe et al. 2010;

Marshall 2016). Each successive space has held the same name, demonstrating both endurance and transformation of the site. The reconstruction project presents both an erasure and layering of the history of the site from its time as a stream to an infrastructural site and then to an urban landscape.

Cheonggyecheon has resulted in quantitative improvements, such as economically revitalizing the city center, increasing public transportation options which also led to increased ridership, attracting flora and fauna to the project site, and increasing international attention to Seoul’s built environment design efforts (

Rowe et al. 2010;

Seoul Metropolitan Government 2006). As a project that is fifteen years old, studies of the Cheonggyecheon have included its financial and cost-benefit analysis (

Bae 2011;

Lee and Jung 2015); the political implications of the project (

Cho 2010); and the project’s overall social, environmental, and political impact (

Lee and Anderson 2013). Changes to the city’s infrastructure, activities, culture, and form that were either direct or indirect impacts of the Cheonggyecheon project are reflective of the broad range of the Seoul Metropolitan Government’s efforts to bring about a transformation of the city through the implementation of the project. My research aimed to compare the project’s design goals and intentions with the project results and impacts on the city of Seoul and its people by using a combination of direct observations of the site and its activation by civic events with interviews with its visitors, designers, and city officials who worked on the planning and design of the project. Interviews with park visitors, workers, designers, and former city staff who worked on the project illuminated the history of the project and site, and the significance of the thematic concept of history that acts as a touchstone of the project’s genesis, planning, and design. This paper is adapted from my dissertation and focuses on the visual narratives of the design of the Cheonggyecheon as expressions of the project’s emphasis on specific elements of the historical theme, and examines how the historical narrative functions as a means of creating a new identity for the city and the reconstructed stream (

Kim 2018). It also reads the project as a work of landscape urbanism and focuses on the significance of the imagination as expressions of its historical narrative. Although the Cheonggyecheon is not often associated with landscape urbanism and has instead been called an urban design project, a linear park, a daylighting project, a reclaimed river, and a restored stream (

Busquets 2011;

Rowe et al. 2010;

Youngerman 2017;

Marshall 2016), the project manifests key elements of landscape urbanism.

In his 2006 essay “Terra Fluxus,” landscape architect James Corner traces the historical divide between landscape and urbanism as both disciplinary and perhaps even competitive professions and as distinct spaces that oppose each other in form, character, and activity. He writes that “the more traditional ways in which we speak about landscape and cities have been conditioned through the nineteenth-century lens of difference and opposition” (

Corner 2006). The separation between landscape and urbanism is illustrated in his discussion of the modern city and its progressive built forms of infrastructure and buildings, whereas landscape, such as in the form of parks, offer respite from the city. The end of the twentieth century presented a heightened awareness of global environmental problems and a desire for sustainable and green building solutions. In response, city leaders and the public approved and celebrated the construction of large-scale landscape projects such as New York City’s Highline Park and Seattle’s Olympic Sculpture Park, both projects that turned post-industrial spaces into public green spaces (

Waldheim 2006). These projects illustrate the processes of change in the built environment, the significance of history and memory, and combining landscape and urbanism for a new kind of urban public space. Instead of separate, opposed entities, these transformed urban green spaces reflect the integration of landscape and urbanism. Corner writes, “Public spaces are firstly the containers of collective memory and desire, and secondly they are the places for geographic and social imagination to extend new relationships and sets of possibility,” (

Corner 2006). Corner’s essay argues for ways in which the combination of landscape and urbanism should both be addressed for better design in the built environment.

The combination of history and visible forms of nature in landscape urbanism projects reflects a stark contrast to the tabula rasa impression of the Modernist concept of urban renewal through the building of new architecture. Whereas urban renewal projects resulted in the erasure of history and memory to accentuate the sense of newness and break from the past through the destruction of older buildings in order to construct the new, landscape urbanism projects acknowledge the historical foundations of the site and retain elements or traces of the past with the new design (

Waldheim 2006). The differences between urban renewal and landscape urbanism present several questions of their respective consequences when constructed for the purposes of urban revitalization. In a landscape design that exhibits traces of the past, does the project evoke history and memory, or by the transformation of use, function, and typology, does the project become intrinsically a new space, and another urban renewal project in a different form? Broader implications address the challenges and possible problems of building a landscape in a space that had been long bereft of elements of visible nature, such as, how can a natural form such as a stream be constructed in the post-industrial city, and what can be construed as nature? These questions help frame the Cheonggyecheon project as a singular and representative case study for an examination of the project as a historical landscape.

As a historical landscape, the Cheonggyecheon illustrates the four themes of landscape urbanism from James Corner’s essay “Terra Fluxus”: “Processes over time, the staging of surfaces, the operational or working method, and the imaginary” (

Corner 2006). Of these topics, the imaginary carries the most significance to the main topics of this paper, and it is expressed together through the design, history, and activation of the site. As a landscape and urban design project, the Cheonggyecheon illustrates time through both actual images, in photographic and other art installations, and through a green space design that serves as a counterpoint to the urban condition surrounding the space. Collectively, it is through an act of the imagination that together the sunken pedestrian channel of the park and the stream accomplish a transformative leap of form and time by breaking up the contemporary urban landscape, and its evocation of the new stream is at once a reflection of a time and place before the modernization of Seoul.

Although the reconstructed Cheonggyecheon may flow at the site of an ancient stream, thereby symbolizing the endurance of its name and geomantic significance, it also emphasizes the technological advancement and application of human ingenuity and industrial processes that the project required for its realization and simultaneously claimed to have erased. As Paul Connerton writes in

How Modernity Forgets, “the repeated intentional destruction of the built environment” is one of the major attributes of modernity. The demolition of the highway overpass and construction of the new stream and park took 27 months to complete, an accelerated demolition and construction schedule that has been one of the reasons for the project’s controversial history, as well as part of its acclaim. Whereas Connerton applies the cycle of destruction and rebuilding to works of infrastructure and architecture, the Cheonggyecheon illustrates the destruction of infrastructure and the transformation of the site into a public space, park, and reconstructed stream. The project’s genesis arose from the growing problem of the aging condition of the highway overpass, and rather than repeating the cycle of destruction and rebuilding infrastructure, and thus maintaining the site’s modern identity, Seoul’s leaders chose to completely reimagine the site. Its transformation into an urban landscape, a reconstructed stream, and public space simultaneously contradicts and exemplifies Connerton’s observation of modernity’s destruction of the built environment. However, instead of evoking only newness and an improvement to the site, the transformation from an infrastructural space to a green space with a reconstructed stream imbues the Cheonggyecheon with visual cues of the city’s ancient and modern past. Through intermingling of the new with representations of the past, the project acknowledges the layers of the site’s histories, but never lets the past diminish the project’s sense of the present and future. In

The Condition of Postmodernity, David Harvey wrote that “modernization entails… the perpetual disruption of temporal and spatial rhythms, and modernism takes as one of its missions the production of new meanings for space and time in a world of ephemerality and fragmentation” (

Harvey 1990, p. 216). The Cheonggyecheon illustrates how the production of meaning and identity for a space can be constructed by forging a connection with the site’s origins and through the destruction of its previous built form.

2. Research Methods:

2.1. Concept: History as a Work of the Imaginary

The ephemeral and unattainable characteristic of time and the past makes the concept of history as a design theme an act of imagination. Historian John Lewis Gaddis writes that “We know the future only by the past we project into it. History, in this sense, is all we have. But, the past, in another sense, is something we can never have. For by the time we’ve become aware of what has happened it’s already inaccessible to us: we cannot relive, retrieve, or rerun it… We can only represent it” (

Gaddis 2002, p. 130). The significance of history and cultural memory serves as a thematic and at times performative device in the design of the Cheonggyecheon. The imaginary representation of the cultural memory and history of the Cheonggyecheon is illustrated by the organization of the park design into three roughly chronological sections. The park is divided into three periods of major historical phases of Seoul’s modern era. The three-part division served a logistical and pragmatic function for accelerating the design and construction of the project by dividing the work into three separate teams connected by a masterplan (Interview 15;

Lee 2008). Additionally, the three-part design represents a truncated and selective chronology of modern Korean history.

The three sections are from west to east: History, or the past; culture, or the modern era; and nature, or what is posited as the city’s future (

Figure 3). The visual narrative of the Cheonggyecheon park is most expressive of the concept of history that frames the concept of the first section and accents areas throughout the rest of the park. The visual historical representations installed in the park reflect the project’s reflection of modern Seoul’s desire for historical roots, what David Harvey describes as “a search for more secure moorings and longer-lasting values in a shifting world” (

Harvey 1990, p. 292). The reconstruction of the stream and landscape also evokes temporality, but the differences in their design through the park evoke both modernity and history, an illustration of Seoul’s progressive advances and an assertion of a scripted historical narrative through the project’s design.

During the planning and construction phases of the reconstruction of the Cheonggyecheon, and after its completion and unveiling, the project was hailed as a return to the origins of the city’s geography that had been buried and hidden by the processes of modernization (

Busquets 2011;

Kal 2011;

Lee 2003,

2006,

2011;

Rowe 2011). The narrative of the reconstructed Cheonggyecheon stream intertwines history with nature as intrinsic elements that define the identity of the space as a means of connecting the past with the present and future of Seoul (

Kal 2011). The narratives of the historic stream as a significant geographic marker of the capital city of the Joseon dynasty, Korea’s last dynasty, and as a polluted wastewater channel that was buried during the modernization period, are illustrated in the design of the Cheonggyecheon through art, historic replicas, and restorations of artifacts unearthed at the site during construction. Yet, the design highlights the former while diminishing the latter history with the division of the park into three sections. The first section highlights images of the Joseon Dynasty, evoking a unified cultural history that predates South Korea as a nation, but translates into nationalism by conveying a sense of unified origins and tradition (

Kal 2011). The second and third sections have a shorter temporal and smaller geographic focus, and represent the site’s modern history, limited to Seoul and the surrounding neighborhood. The prominence of the first section conveys the desirability for the revival and endurance of Korea’s dynastic history over South Korea’s modern history. The first section also serves as a backdrop or stage, the space in which the historical narrative of the city is retold and presented in different forms. The layering of historical imagery suggests that the reconstruction project serves as a constructed palimpsest, illustrating David Harvey’s critique of postmodernism for its fragmentation of the urban fabric (

Harvey 1990). Fragmentation serves as a central characteristic of the Cheonggyecheon’s representation of temporality and in the construction of its historical narrative.

Despite this sense of fragmentation, or perhaps because of it, the division of the park into historic and chronological sections emphasizes the importance of the project’s representation of the landscape urbanism theme of the “processes over time” though this theme is another act of the imaginary. The design of the Cheonggyecheon’s depiction of processes over time evokes the site’s permutations over its history. The project’s design and construction process emphasized time in order to accelerate the project timeline, illustrating two of philosopher Paul Connerton’s critique of modernity: Its “production of speed” and “the repeated intentional destruction of the built environment” (

Connerton 2009, p. 99). For the city of Seoul, the rapid transformation of the Cheonggyecheon was the goal of the project. The project’s demonstration of the speed of the process of change in the city’s built environment suggests a continuation of the rapid growth processes of the modernization period that started under former president Park Chung-hee. However, the city has embraced the production and process of speed as marks of its advancement and transition to a global city. The production of speed may seem the antithesis of the design theme of history. However, for this project, the outcome of the design emphasizes the distant dynastic past, while simultaneously illustrating the erasure of the overpass and road within 27 months and the rebirth of the site as a stream and park.

2.2. Methods of Reseach

The aspiration of this research project was to unveil the narratives designed and embedded into the design of the landscape of the Cheonggyecheon, and also what significance the park visitors have imbued onto the landscape through their actions and responses to the space. The goal of this research was to gain an understanding of the multiple narratives and views of the past, present, and future of Seoul, South Korea as reflected in its built environment, and the implications of constructing urban landscapes in the contemporary 21st century city.

To align my research with the Cheonggyecheon project’s conceptual framework of narrative and history, my research methods explored ways in which the narrative of the Cheonggyecheon’s history was manifested in the project’s design and creative process by combining direct observations of the site, and recording them with still and video photography, and with interviews with park visitors, designers, and former city staff who worked on the project. The significance of narrative, in the visual design of the park and in the narratives voiced by interview subjects, grounds the topic of this research and the methods used in doing the fieldwork research in South Korea. The use of different methods, and interviews with different groups of subjects, allowed for triangulation of research findings. The interview narratives were compared with the visual and historical documentation of the Cheonggyecheon project following the publicity for the project as presented by the city and in international media, presentation material from the city and designers, and historical and artistic narratives of the project site.

I had the opportunity to do preliminary fieldwork observations during a weeklong visit in July 2015, while the bulk of my fieldwork research to observe the site and interview its visitors, designers, and planners was done from late August 2015 to early February 2016. For the oral narratives, I conducted semi-structured interviews with three groups of people: Visitors to the Cheonggyecheon, whether they were visitors or workers at the site; project designers; and Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG) Cheonggyecheon project team members during the planning and construction of the project. The narratives distilled from all the interviews were screened to maintain the subject’s anonymity to protect their identities.

The interview subjects were a combination of random and referral sampling. The visitor interviews were randomly sampled from groups of visitors that I encountered sitting at different locations of the park. Focusing on groups of people that were stationary, rather than walking or running through the park, allowed me to approach the subjects and request asking a few questions about their opinions and knowledge of the Cheonggyecheon. I interviewed 15 people at the Cheonggyecheon between September and October 2015. I approached many more people, more than double the number who agreed to be interviewed, but the majority of the people I asked either refused to speak at all or refused to be recorded. The interviews with the designers and former city workers were conducted in October and December 2015, and January 2016.

The shorter interviews with park visitors focused on the following four questions:

Could they describe the site before the reconstruction?

Was their answer to the first question their actual memory of the site before it was turned into a park, or knowledge that they had learned from elsewhere?

What was their opinion or impression of the Cheonggyecheon in the current state?

Did they have any other comments to add regarding the Cheonggyecheon project?

The intention of the questions was to be open-ended enough to allow the respondents to tell their narrative of their memory of the site in whatever way they chose. Interviews with the project designers and SMG project team members also began with the same questions, but these longer interviews evolved into more of a dialogue, as they wanted to know more about my research project goals for holding the interview. The average length of this group of interviews was an hour. As a result, these interviews provide richer discussions than the short visitor interviews, but they may include elements of co-construction of narratives as part of the dialogic format (

Esin et al. 2013), with some discussions being framed by my research concerns. The discussions were focused on the process and intentions of the work involved in planning and designing the Cheonggyecheon and revealed the challenges and highlights of their experiences in having been part of the project. The topics of memory and nature were discussed in greater detail than with the park visitors. The memory and history topic touched on both the designers and SMG team’s recollections of working on the project, as well as the significance of history as a design concept for the project.

3. Results

3.1. History and Seoul’s Past in a Modern Light

The start of the Cheonggyecheon begins with Cheonggye Plaza at the street level, and the entirety of the first section resides in Seoul’s central business district (

Figure 4). The plaza was designed by the Korean-American landscape architect Mikyoung Kim, while the first section of the park was designed by South Korean landscape architecture firm SeoAhn Total Landscape. The entrance is dominated by the water that begins at the plaza and continues as the constructed headwaters of the stream. The water serves as a visual and aural counterpoint to the surrounding cacophony of the urban setting, but the design of the stream in this section emphasizes its modernist artifice. Through its highly stylized, urban form, the design presents the stream as a highly controlled and technologically advanced production, filled with highly treated water that is regularly tested by park workers. The design suggests a modern illustration of historian Peter Perdue’s reading of water conservancy in ancient China: “The proper control of water and land use, in the Chinese official view, meant directing nature toward the satisfaction of human needs” (

Perdue 2010). The Cheonggyecheon extends human needs to the urban landscape and expands on the idea of these needs to include environmental amelioration, urban respite, and urban aesthetics. For visitors who enter the park through the sloped ramps, the section blends the urban fabric with the submerged park and continues the hard edges of the plaza design, emphasizing the newness, cleanliness, and modernity of the project (

Figure 5).

The concept of the section is history and culture, and in certain design elements and in the spectacles staged in the space, the first section illustrates selective highlights of Korean history, emphasizing the Joseon dynasty (1392–1910), which was the last Korean dynasty before Korea’s annexation by Japan. The most prominent example is the replicated image of the map of ancient Hanyang, (the ancient name of the capital city) called “Doseongdo,” (

Figure 6) during the Joseon Dynasty, and the prominence of the Cheonggyecheon and its tributaries at its center, like a connective central core and its branches across the city, illustrating the natural foundations of the capital city’s geography and topography.

The Doseongdo connects the history of the Joseon with the reconstruction of the Cheonggyecheon project and reinforces the idea of the site as one of Seoul’s “lieux de mémoire.” The design of the section, however, offers a sharp contrast to the historical and cultural elements that are represented. Although other parts of the Cheonggyecheon may also have a hard edge next to the promenade, the start of the Cheonggyecheon’s pristine stylized headwaters accentuates a vision of newness, modernity, and cleanliness. The space welcomes visitors with a coin toss area to commence their promenade, much as they would at a fountain, such as those found inside shopping malls or outside on civic plazas. In fact, much of this fountain area has the stark, abstract quality of the post-modern city that Rem Koolhaas describes in “Generic Cities”: “Is the contemporary city like the contemporary airport—‘all the same’?… What if this seemingly accidental—and usually regretted—homogenization was an intentional process, a conscious movement away from difference toward similarity?” (

Koolhaas 1995). Despite the abstract quality of the design, the designer Mikyoung Kim’s concept for the design of the plaza carries a subtle undercurrent of political meaning and cites “a symbolic representation of the imagined future reunification of North and South Korea” (

Zamora Mola 2012) by incorporating stones from provinces in both North and South Korea.

As visitors pass beneath another historic motif and artifact, the restored Gwangtonggyo Bridge (

Figure 7), and emerge on the other side, the water edge takes on a softer edge and a naturalistic appearance through the addition of naturalistic stones and small touches of vegetation. The discovery of the buried Gwangtonggyo during project planning in 2003 provided popular support for the stream restoration and as Hong Kal described, its “discovery gave life to the stream and brought back the past needed for the national imagination” (

Kal 2011). Kal’s description of the effect that the discovery of the Gwangtonggyo had on the public imagination suggests that the public had a desire for the revitalization of history and the formation of a new national identity. In the Cheonggyecheon’s design, the bridge serves as a temporal portal between modernity and the beginnings of a riparian landscape.

The modernity and austerity of the plaza gives way to a green space once visitors cross the threshold into the more naturalistic space, and they are greeted with the continually looping audio reenactment of the sounds of King Jeongjo’s procession to visit his father’s grave, as depicted in the long tile painting that anchors the next part of the first section (

Figure 8). Thus, the hyper modern space gives way to an aural and visual space of history and culture. The tile painting depicts a popular historical image which gives this section of the park the atmospheric quality of an outdoor museum exhibit and connects it to other cultural spaces such as museums, palaces, and other heritage sites that display historical representations. The otherness of the space through the media presentation accentuates the heterotopic dimensions of the park (

Foucault and Miskowiec 1986). In this sense, certain parts of the Cheonggyecheon are a part of the larger South Korean project of displaying its history in different media and venues or spaces, and the open, centralized space of the Cheonggyecheon serves as a popular event space.

The multimedia presentation of a historical narrative is most prevalent during certain special events at the site, and highlights the city’s efforts to provide spectacles and activities to the park, reinforcing the space as a heterotopia. During festivals and performances, much of the first section acts as a stage, not just the street level plaza. One of these is the annual the Seoul Lantern Festival, when visitors can enter the space to view the lantern installations filling the waterway. The festival acts as a civic and community event and a promotional opportunity for South Korean commercial brands, tourism, history, and a vision of its place in a globalized world. Although it is called a lantern festival, with the name recalling the idea of small, hand-made objects to display light, the actual lanterns are large installations made of LED lights with corporate, civic, and global sponsorship. Like the Cheonggyecheon itself, the festival illustrates the modern and new interpretation of the old and traditional.

The lantern installations were grouped into four themes: Classical images of the historical narrative of the Joseon Dynasty, folkloric scenes of Korean everyday traditions, international lanterns from neighboring countries and cities, and modern images of South Korean commercial brands. The combination of the historical narrative of South Korea and its contemporary focus on global and commercial pursuits reinforces the identity of the city and country as places of modernity and historical roots. The festival, like the park, provides a journey in time and space. The first lantern was a LED replica of an Ilwol-o-akdo painting (

Figure 9), which depicts the sun, moon, five mountains, and water, all the elements meant to protect the dynasty, and providing an introduction to the festival as a modernized interpretation of the past as mythology. This classical image illustrates the geomantic natural elements for which the specific location of the ancient capital of Joseon was chosen, and it was used as the backdrop for the Joseon royal throne (

Yu and Kwŏn 2005). The major displays in the first section of installations, replicas of palace and shrine architecture (

Figure 10), had signs in Korean and English explaining their historical significance, making them also much like museum displays and asserting Seoul’s image as a global city.

The lantern festival not only provides a seasonal festive event and spectacle for Seoulites and its visitors, it also combines a celebration of the nation’s history while seamlessly acting as a promotional vehicle for its global brands and positions the city, and by extension, the country, as part of a larger cosmopolitan community. Much like the narrative of the Cheonggyecheon itself, the lantern festival reiterates the narrative of the historical journey of South Korea from the founding of the Joseon dynasty to the globalized world, with South Korea asserting its global economic growth and strength.

3.2. Modernization and Its Fissures in the Urban Landscape

While the first section of the Cheonggyecheon is located in the central business district and has become one of the central features of the area, the middle section of the park is surrounded by a bustling commercial area dominated by the Dongdaemun and Pyeongwha markets. In contrast to the market and traffic activity on the street level, the second section of the Cheonggyecheon offers a respite from the urban landscape, while the park’s visitors can gaze up towards the market buildings surrounding the stream. Designed by South Korean landscape architecture firm SYNWHA, the second section’s concept was the modern era and Seoul’s present. The historical markers displayed on the walls of this section include black and white photographs of the site that begins with the beginning of the 20th century, as in the photograph of women washing clothes in the original stream, to the end of the 20th century, when the Cheonggyecheon site was dominated by the rushing cars on the highway ramp over the site (

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15).

These images of the highway ramp are comparatively recent history, but the collective imagery of the installation harkens to a bygone era by their presentation in black and white on small tiles that are built into the walls. The muted quality of the images, the small size of the displays recessed into the walls, and the brief, small captions in lieu of explanatory information displays give the section a more utilitarian and less formal quality than the first section. The historical markers seem less about recalling history and more about subtly and quietly evoking memory, but they are done in ways that do not distract from the main channel of the promenade, making the entirety of the space the main focal point, rather than any one particular display or installation. The subtleness and small scale of the displays make these historic images less noticeable than the art installations in the first section.

One area of the second section reinterprets one of the photographic images of the women doing laundry in the original Cheonggyecheon. The area is called the laundry area, and features stylized concrete slabs, built to look like laundry washboards that lay on the water’s edge (

Figure 16). The proximity of the water here allows small children to dip their hands into the water, making it one of the areas that is popular for families to stop and play. The abstract design of the concrete laundry slabs gives the area a distinctive appearance from the rest of the water edge of the park, and more than evoking images of a laundry space, they give the space a playful edge that allows the water to merge and intersect more with the promenade. Apart from these few discreet displays, the majority of the spaces in the second section is full of lush vegetation, and there are certain areas where the walking path is only on one side of the stream, allowing for the greenery to dominate one half of the space. Thus, whereas the first section of the Cheonggyecheon varies the attention and focus between the art and displays with the flora, the second section puts more emphasis on the riparian landscape and stream for the most part, and the displays alluding to the past are either not noticeable, or made to not take attention away from the natural elements.

This section offers a strong contrast to the urbanism found on the street level, and at times, it seems to offer the most removed space from the surrounding urban fabric, both in the contrast with the upper street level and because the Cheonggyecheon’s grade difference with the street level increases as it moves further east. One significant historical feature of this section is the statue of textile worker and labor activist Chun Tae-il, who died of self-immolation in 1970 during textile workers labor protests (

Cho 2003), which stands at the street level on the Beodeuldari Bridge, also called Chun Tae-il Bridge (

Figure 17).

The statue is a reminder of the turbulent history of the markets and their workers (

Kal 2011;

Cho 2003). Visitors who are unfamiliar with this history might not venture onto the street level to look at the statue since it is located outside the Cheonggyecheon, which suggests that this painful chapter of the modernization period may still be a source of trauma. The statue’s installation outside the park suggests that the city found that this reminder of the site’s past was undesirable as a focus of attention and better left to be eventually forgotten, demonstrating Connerton’s notion of competing histories and that in the process of forgetting, “the first thing to be forgotten is the labour process” (

Connerton 2009, p. 40).

In contrast to the central business district, which is predominantly surrounded by office towers and retail spaces like cafes, restaurants, and clothing and cosmetic shops, the second section has a mixture of businesses ranging from wholesale vendors and light industrial manufacturing, many with their inventory and discarded packaging filling the sidewalks and even onto the street. They reflect the limited space for these businesses and are suggestive of the congested atmosphere of the urban conditions when the Cheonggyecheon was a highway ramp. Both the design of the space and the busy commercial activity above the space illustrate the ongoing disconnect between the Cheonggyecheon of the modern period and the reconstructed version that has been built in its place.

3.3. Urban Ecology and Seoul’s Future

The final section is towards the eastern part of Seoul, which includes the part of the Cheonggyecheon where it converges with the Jungnangcheon stream and then eventually flows into the Han River. The design concept of the section integrates the concept of natural ecology with the future of Seoul. The third section, designed by South Korean landscape architecture firm CA Landscape Design, incorporates the surrounding area to form a series of outdoor activity spaces adjacent to the Cheonggyecheon. The stream becomes much wider in this section, and the surrounding vegetation also covers a larger expanse than in the first and section parts.

The design of the section contrasts the pristine and stylized design of the first section, evoking a natural setting, especially in the section where the Cheonggyecheon merges with the Jungnangcheon. Viewed from this section of the park, visitors might be led to believe that the park, in particular its stream, was not the product of a scripted design and stream engineering. There is more fauna activity in this section, not only the migratory birds, but also more fish that have migrated to the Cheonggyecheon from the connecting bodies of water. As for the flora, they are more in abundance in this section, and have a more “wild” and, in some places, unruly presence, which gives the plantings the feeling of actual wilderness. However, some park visitors expressed dismay at the naturalness and expressed a preference for a more manicured landscape.

The idea that the future of Seoul being illustrated by a natural ecological landscape might seem unrealistic, yet it is more indicative of the grand vision for the project, the stark contrast between the modernity that had been accomplished and the envisioned natural landscape of the city’s long-term ambitions. The landscape design of the third section could arguably represent the most fantastical level of a scripted space, harkening to a past that could not have existed in Seoul before the 21st century. The reconstruction completely contrasts and erases the memory of the reality of the site’s shanty house-filled 20th century past. Instead, it presents a diverse ecological space intertwined with areas for sports and recreation, evoking the image of Seoul as having preserved large areas for a green space and dedicated to leisure activity.

Despite the emphasis on a natural stream and landscape in this section, there is still a strong urban presence, with the looming Naebu expressway which passes over the site, as well as the modern Cheonggyecheon Museum, which stands across the street at the beginning of the section. Additionally, as reminders of the Cheonggye highway ramp that was demolished to create the new project, three partial columns from the old highway stand in the middle of the water, serving as ruins to keep the memory of the former infrastructure of the highway ramp partially preserved in the new space (

Figure 18). The remaining columns give an indication of the large scale of the demolished highway ramp and how it may have once dominated the space. Its authenticity as a marker of modern memory and history stands in contrast to most of the other historical and memorial displays at the site, which are mostly replicas or excavations of ancient remains that have been reconstructed or restored. Yet, as ruins, they represent the erasure of the past and the creation of a new identity for the site. As memories of the highway overpass increasingly recede, one might wonder what meaning the columns might carry in the future.

One final marker of history is the replica of a shanty house (

Figure 19) that is built over the Cheonggyecheon, directly across from the gleaming glass structure of the Cheonggyecheon Museum. The replica is depicted as a store, complete with posters and signs, and functions as a life-size museum display, which visitors can enter, walk under, and see from both the street level and below in the park. Like the remains of the highway ramp, they serve as reminders of the site and the stark contrast with its current incarnation, but unlike the remaining columns, the replica is a simulacrum: Clean, albeit with grime and age as part of its design, and sturdily built, unlike the actual shanties that filled the space. They represent a part of the history of the site in an overtly simulated form, which might harken back to the past, but with a sense of distance and removal from the actual hardship and unsightliness of the past. The simulacrum of the recreated shanty house juxtaposed with the modern museum reflects Andreas Huyssen’s assertion that “an urban imaginary in its temporal reach may well put different things in one place: memories of what there was before, imagined alternatives to what there is” (

Huyssen 2003, p. 7). The Cheonggyecheon reinforces the layering of multiple histories to diminish the reality of what has been overcome and to magnify the achievements of the present.

The reconstruction of the Cheonggyecheon as whole could be characterized in this way, in that it was built on the site of an ancient stream, which in the modern period had become ruined by pollution and then covered over by a road and turned into an infrastructural space. In its rebuilt form, it serves as a public amenity for recreation and leisure, and not as a space to wash clothes or throw away waste. Although the central focus of the linear park is a water channel like the original stream, it reflects the advances in technology and wealth of South Korea, and the social and environmental concerns of the 21st century urban landscape that the city of Seoul aimed to ameliorate. Through its goal of environmental, social, and urban improvement, the city produced an image of an improved past to represent its renewal and to redefine its identity. The narrative of Seoul’s history as depicted in the Cheonggyecheon reflects a continuation of South Korea’s spirit of development and progress. But in our contemporary age, when the processes of industrialization and modernization have proved unsustainable and cities and individuals must work to mitigate and undo their damaging effects, the progressive efforts of a project like the Cheonggyecheon present both an amelioration of the urban condition as well as a continuation of its challenges and complexities.

4. Discussion: The Cheonggyecheon’s History and Memory

“All time, all time is history—not just Joseon, from the Joseon to the modernization period—is the history of Seoul, of the Cheonggyecheon.”

—Cheonggyecheon design team member (Interview 15)

“The Cheonggyecheon had shacks. The stream water was very dirty and there’s no way to describe how bad it was. It was dirty and smelled bad. That’s my memory.”

—Seoul resident describing the Cheonggyecheon fifty years ago (Interview 6)

From interviews with its visitors, the Cheoggyecheon has resulted in a mixed, but mostly successful introduction of landscape in the city of Seoul. It achieved the transformation of a work of aging infrastructure, a highway overpass that was in disrepair, into a green pedestrian space in the city center. Despite voicing some criticism for the project, most of those interviewed expressed appreciation for the resultant public space amenity. As a greenway free of the vehicular congestion that once dominated the space, the Cheonggyecheon now illustrates the integration of landscape and urbanism promoted by James Corner’s “Terra Fluxus” essay. The Cheonggyecheon has used elements of its past as a touchstone for it reconstructed stream, anchored by historical images, replicas, and restored artifacts. Yet, the narrative of the park’s design and its representations of history emphasizes the Imaginary as the overriding design concept.

The narrative of the Cheongyecheon’s and Seoul’s history is presented in different ways through the design of the park. Through a combination of media, community and municipal events, and specific conceptual timeframes for the design of the park, the Cheonggyecheon exhibits a variety of functions, atmospheres, and visual and experiential conditions, depending on the time of day, season, or location within the park. The activation of the park illustrates the project’s adherence to the theme of the imaginary and imbues its evocation of history with creativity and beauty for the purpose of entertainment and celebration. The park’s spectacle of historical representations in abstracted and layered forms gives dynamic expression to Halbwachs’ assertion that “there is a living history that perpetuates and renews itself through time” (

Halbwachs 1980, p. 64). The historical narrative of the design of the park presents a complex blend of chronological order and reordering that is made more intermingled with the addition of installations and other media. The park’s designers describe the three sections of the park as history, or the past; culture, or modern period; and nature, or the future (Interview 15). However, within these conceptual sections, the past, contemporary culture, and the future are intertwined and constructed and activated in layers, suggesting that temporality, or the processes of time, extends the entire length of the park and serves as one of the major narrative devices of the project.

The space for special events is usually limited to the first section of the park, with its concept of history. However, the design of the section is modern and partially clear of the riparian landscape that extends the majority of the park. With the addition of artistic and folkloric representations of history, the historical narratives of the ancient Joseon Dynasty evoke a sense of newness and abstraction. This quality to historical representation aligns with the designers’ assertion that the project was not meant to be a historic restoration (Interview 15, 16). Instead, the project’s presentation of history is most often aesthetic, with artistic representations that beautify the park, or provide visual and auditory interest. Through the aesthetic representations of historic motifs, such as the replicas of the mural depicting King Jeongjo’s procession and the Doseongdo map of ancient Hanyang, the Cheonggyecheon presents the city’s redefined identity “through the revitalization of its own history” (

Nora 1989). In this way, the project asserts the ancient history of the Joseon Dynasty as a key narrative of the Korean identity, but as presented in the modern surroundings of the park’s first section, it suggests a new and revitalized history and the assertion of a modernized national identity built on a selective idealization of the past. The lantern festival installations of ancient architecture and paintings from the Joseon period likewise evoke a sense of newness to the representations of the past.

The opposing perspective of this reading of the park as a representation of history, underscoring the fictional element of the Imaginary, is the lack of historical continuity, and in its place a fictional construction, of which David Harvey laments, “the search for roots ends up at worst being produced and marketed as an image, as a simulacrum or pastiche” (

Harvey 1990). The combined effect of the historical traces in the park’s design serve as unrelated heterotopias of time and place, suggestive of Korean-ness, instead of Korean history. However, the designers and SMG project team interviews state that despite the original intention of recovering its 600-year old history (

Park 2006), historical restoration was not the goal of the project, because it was both not possible nor desirable (Interview 15, 16). This assertion was in response to questions of the project’s authenticity in not reaching a natural restoration of the stream and the decision to incorporate replicas of certain archaeological landmarks from the original stream, particularly the Supyogyo bridge. These decisions were made in response to the infeasibility of full restoration due to the urban condition of Seoul, space limitations, and degradation of some of the artifacts (Interview 18). Adding to the infeasibility of the past as a design precedent was the reality of the history of the stream and Seoul.

In contrast to the stylized representation of dynastic history displayed in the first section, interviews with park visitors described the modern past of the Cheonggyecheon site. Respondents described the desperate and harsh conditions of the area surrounding the stream, which one of the designers interviewed summed up as “a very poor period… it wasn’t like we could reminisce and make it into a landscape” (Interview 16). The designer also described the concept of incorporating historical traces as a work of the imagination. The imaginary functions as both interpreter and editor of the project’s representation of history. In this way, the Cheonggyecheon’s representation of history illustrates Connerton’s assertion that collective forgetting is a condition of modernity. He references 19th century French theorist Ernst Renan’s assertion that “forgetting… is a crucial factor in the creation of a nation” (

Connerton 2009). The Cheonggyecheon operationalizes this idea in a series of erasures and reconstructions of the past that either diminishes or acknowledges the site’s modern past in discrete, almost unobtrusive ways. Despite having a theme of history in the first part of the park, the narrative of the modern history of the site is not exactly eliminated, but it is not made the focus of any part of the park.

The design of the second and third sections of the park illustrate how memorial elements of the site are represented as abstractions, as in the laundry site, the remaining columns of the highway ramp that stand as partial ruins, and the replica of a shanty house. They stand apart, removed from the context of their actual history, and as time passes, they become more distanced from the temporality of the project’s design scheme, becoming a distortion and “necessarily fragmented” (

Harvey 1990). Nora distinguishes “memory… [as] a perpetually actual phenomenon, a bond tying us to the eternal present; history is a representation of the past” (

Nora 1989). Instead of signifying the memory of the site, Nora would argue that all historic markers evoke the frozen representational element of history. Other memorial devices installed on the project are either removed from the park space and placed on the street level, or framed as small, almost unnoticeable, photographs inserted into the wall of the promenade. In addition to the replica of the shanty structure, the statue of Peace Market labor activist Chun Tae-il sits on one of the vehicular bridges that cross the Cheonggyecheon. The inclusion of Chun at the site reflects its painful history, but, like the shanty house, they represent the parts of the past that the Cheonggyecheon project does not want to revitalize and highlight. Lynch asserts the necessity for the selective representation of history, as “escapes from the servitude of the past” (

Lynch 1972, p. 36). By arguing that “we prefer to select and create our past and to make it part of the living present” (

Lynch 1972, pp. 36–37), Lynch argues that having editorial control over the past allows for moving forward, especially in response to a history that is marked by strife and struggle. A major example of this selective editing of history in the Cheonggyecheon’s historical narrative is the glaring omission of the Japanese colonial period. The deliberate erasure of this significant timeframe from the design illustrates the project’s nationalist assertion by removing the period from the broad timeline of historic markers. Yet, the prominent inclusion of the Japanese lantern installation during the Lantern Festival is indicative of the city’s focus on promoting globalization and cultivating a cosmopolitan image and outlook. The Cheonggyecheon reflects divergent and imaginative representations of history and memory. The chosen representations ultimately give the project a sense of history from which the city has moved past the memories of hardships and struggle. In this sense, the project reflects Halbwachs’ assertion of the incompleteness of a historical project when he writes that “history is neither the whole nor even all that remains of the past” (

Halbwachs 1980, p. 64). For the Cheonggyecheon’s representations of history, its incompleteness strengthens the positive outlook of the historical narrative by the exclusion of difficult chapters of South Korea’s past.

Despite this truncated and selective chronological presentation of the historical concept, park visitors praised the progress and development of the park. For those respondents who could remember the highway ramp and the polluted stream, the transformation into a park and new stream represented an overall advancement for the city. By comparing the old Cheonggyecheon with the new, they read the project as part of a larger chronology of Seoul, alluding to a perception of the whole city and its built environment as pieces of that chronicle. In this regard, the older Seoul residents who witnessed and described the site’s past demonstrate the “permanent evolution” (

Nora 1989) of memory. Their contrasting memories of the site from the memories and knowledge of the site recounted by younger respondents highlight the different ways in which respondents wanted to discuss the park. One younger respondent focused only on the future potential of the park as an exhibition space: “I think the Cheonggyecheon can become [or change into] a place to display art and have people experience it firsthand” (Interview 14). The respondent’s hope of using the park as an exhibition space suggests that for her, the historic art and artifacts that are part of the park’s design serve as background to the physical form of the stream and park, allowing the timelessness of the space to express other narratives. The perception of the park as a setting for artistic, civic events, bringing visual arts into a larger, more open forum than in a gallery or even a museum, illustrates another heterotopic dimension of the Cheonggyecheon as a public space. More significantly, the respondent’s remark expresses the city’s desired goals of the project: to reflect the evolution of the future-oriented vision of the city.

5. Conclusions

The major questions posed by this research began by asking whether a landscape design that exhibits traces of the past evokes history and memory. Or, through the transformation of use, function, and typology, does the project become intrinsically a new space, and another urban renewal project in a different form? The design of the Cheonggyecheon landscape was a reconstruction of a stream that deliberately did not evoke history and memory due to the negativity and difficulty of Seoul’s and South Korea’s past (Interview 16), so the representation of history is notable for its celebration of cultural heritage. Despite the challenges posed by depicting images of the past, the design constructs a refined and pointed historical narrative. The modern aesthetic of the new space, especially its clean water, imbued a new meaning and identity to the park, thereby illustrating the process and goals of modernity (

Harvey 1990;

Connerton 2009;

Lynch 1972). However, this transformation was the goal of the city as it planned the project and after completion, appreciated by park visitors as an improvement to the city’s built environment.

In the thematic History section, with its replicas of historic imagery and iconographic representations of ancient Seoul, the project displays visual and spatial cues to the city’s and the dynastic past. Through the modern and sanitized reconstruction of a historic stream, the project achieved cultural, though not full, restoration of the site, emphasizing the narrative of Seoul’s ancient history as a revival of the city’s cultural heritage. Restoration of historic artifacts from the site, what the designers have called the historical traces that laid buried with the original stream, serve as the project’s tangible connections to the city’s heritage. The representation of history reveals a narrative of Seoul that celebrates modernized fragments of the past and the passage of time that has brought about the reconstruction project. Through the fragmented representation, the project erases the difficult and challenging parts of South Korea’s more recent history. The selectivity of historical representations highlights the parts of history that the city chooses to celebrate and retells for its endurance, a process that Kevin Lynch argues is a necessary part of the process of building the present as distinct from the past (

Lynch 1972). Instead, the project emphasizes positive reinterpretations of historic imagery, partial restorations, and reconstructions of the past. As for the evocation of memory, interviews with park visitors elicited some knowledge of the site’s past, but most regarded the park as a completely new place, an opinion echoed by the project designers and members of the Seoul Metropolitan Government (SMG) team. Those who reflected on the site’s past could only remark on the negative aspects, reinforcing the design decision not to evoke the site’s past, and expressing appreciation for the present condition of the park as a sign of progress. It represents the ongoing goal of the city’s continuous improvement and development of a 21st century identity as a global city, yet it continues to reconnect and revitalize its history. The project shows that in the city’s efforts to construct dramatic changes to its built environment, the overall project of the city’s improvement, as well as the formation of a new identity, is still a work in progress.

Much of the negative history of Seoul that the Cheonggyecheon markedly did not include in its design were contentious and struggling periods in South Korea’s past. Its project to reconstruct and rewrite the city’s image and identity for a globalized world has culled the desirable elements of its history and memory and represented them as celebrations. In order to make the city’s public spaces truly celebratory for its people, the city needs to find ways to expand on the ideas of rebuilding its past for the advancement for its whole society, and not risk undermining the progressive campaign of improving the city’s built environment by repeating the marginalization of affected populations.

The main lesson that has emerged through this research project is that the process of constructing the built environment is an ever-evolving process that includes not just the actual planning, design, and construction. The evolution of the Cheonggyecheon through its use, maintenance, especially its hoped-for eventual resolution of devising a more sustainable water supply, and the construction of its narrative, reflects the city’s efforts to keep its built environment a vital and relevant component of its past, present, and future. Conversely, the project reflects the city’s efforts to strengthen aspects of its historical narrative to rebuild and reify its image while simultaneously diminishing negative memories and history that it wishes to overcome and move past. The gradual erasure of the undesirable past reinforces the city’s project to demonstrate its ongoing progressiveness and underscores its ability to reinvent itself. The Cheonggyecheon may again change in the future and redefine its history and identity, and through this process continue to illustrate the dynamic qualities of the city and its built environment.